1. Introduction

Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn., usually called java ginseng in southeast Asia, is one of plant varieties native to tropical and subtropical America. Today, it grows widely in the warm regions of the southern and northern hemispheres. The leaves of java ginseng contain high levels of ascorbic acid, protein, insoluble dietary fiber, magnesium, potassium, iron, and calcium, which can serve as an alternative nutritional source to diversify food [

1,

2]. Due to its extended flowering period and appealing, vibrant, and exquisite flowers, java ginseng also utilized as an ornamental plant. Furthermore, java ginseng extracts contain saponins, flavonoids, tannins, triterpenes, sterols, and polyphenols endowed with antioxidative, antibacterial, and antifungal properties, makes it a widely used plant in the treatment of numerous infirmities such as cancer, diabetes, hepatic ailments, leishmaniasis, and reproductive disorders [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Latest studies suggests that ethanolic extracts of java ginseng may reduce cardiac structural damage [

8,

9]. So far, the utilization of java ginseng is still at the stage of direct utilization of wild resources. Therefore, conducting targeted breeding to create new planting materials with higher biomass and medicinal components is of great significance for the utilization of java ginseng.

Polyploidization usually produce more massive cells that result in increased structural size and ascended levels of essential secondary metabolites, and became an effective approach in increasing biomass and secondary metabolites in plants [

10,

11]. For instance, tetraploidization increased leaf size, trichome density, and cannabidiol in

Cannabis sativa [

12] and improved the agronomic characteristics and medicinal elements in

Anoectochilus formosanus [

13]. In Eucalyptus, tetraploids induced from zygotic and somatic chromosome doubling augmented the oil gland‘s size in leaves [

14,

15]. Based on the same considerations, we assume that auto-tetraploidization may also alter the agronomic traits of java ginseng, including aboveground biomass and secondary metabolite content, thereby enhancing its economic value.

Due to the lack of reports on the induction of tetraploid java ginseng, this study developed a rapid induction system for polyploid java ginseng using colchicine as a chromosomal doubling mutagen and determined the optimal induction treatment conditions. The phenotypic and agronomic traits of tetraploids and diploids of java ginseng were compared, and the metabolites content were analyzed through metabolomics analysis. The tetraploids acquired in this study have the potential to increase the utility value of java ginseng and establish a foundation for triploid breeding in the next stage.

2. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

2.1. Germination of Axillary Buds from Single Node Segments

In the selection experiment of axillary bud germination induction medium, all treatments were able to achieve 100% germination of axillary buds, but the growth vigor of regenerated plants varies greatly (

Figure 1,

Table 1). All mediums got weak regenerated plantlets except medium number four and nine. Specifically, medium number one, three, five, six, seven, and eight which without 6-BA produced callus at the lower end of the stem segment, resulting in rootless regenerated plants. Among the remaining three mediums, medium number nine which containing no hormones resulting in the most vigorously buds and roots, makes it the optimal medium to induce polyploid.

3.2. Tetraploid Induction and Ploidy Identification

To induce polyploid, a total of 658 single node segments were treated with different colchicine concentrations and immersion times. A total of 398 plantlets were obtained, of which 61 are tetraploids and 73 are chimeras (

Figure 2,

Table 2). The optimum concentration of colchicine is 1-3 mg/ml, and the optimum immersion time is 48 h. the highest induction rate is 18.03% with 1mg/ml colchicine for 24 h.

3.3. Phenotypical Changes in Tetraploids

The influence of tetraploidization on phenotypical characteristics was investigated. Compared with diploids, tetraploids had more leaves at the seedling stage (Fig. 2a, b), darker green and oval-shaped leaves (Fig. 2c), bigger fruits (diameter of fruit: about 4mm of tetraploid vs. about 3mm of diploid) (Fig. 2d), and slightly darker flowers. Besides, a few of three and four petal flowers were observed alongside with the original five petal flowers during the first time of bloom, and not observed thereafter, while no abnormal flowers observed in diploid plants, showing the significant impact of tetraploidization on the flower morphology of java ginseng at the early stage (Fig. 2e, f).

The differences in stomatal, leaf anatomical, and pollen characters between diploids and tetraploids were analyzed (

Figure 3), and the changes related to ploidy level were investigated. ANOVA analysis showed that the stomatal length, stomatal width, stomatal density, leaf thickness, and pollen diameter are significantly different in diploid and tetraploid plantlets (

Table 3). With tetraploidization, stomatal length and width increased by 35.88% and 22.75% (

Figure 3a, b), while stomatal density decreased by 64.20% (

Figure 3c, d). The average thickness of leaves increased by 87.88%, with larger leaf cells and looser tissues (

Figure 3e, f), and the diameter of pollen grains increased by 29.97% (

Figure 3g, h) with tetraploidization.

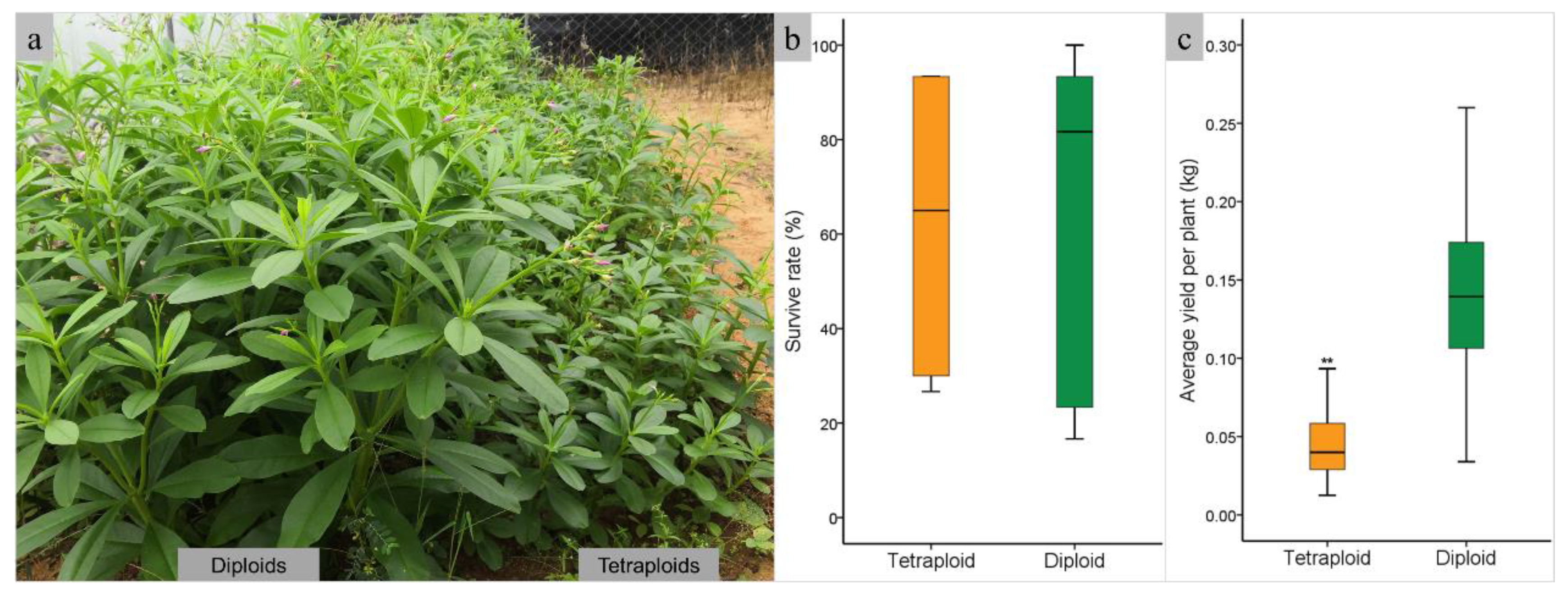

3.4. Comparison of Aboveground Biomass Between Diploid and Tetraploid

Diploids and tetraploids were planted in the field to evaluate the fresh weight yield of tetraploid plants. Plant growth performance showed that the height of tetraploids is much lower than diploids, exhibiting dwarfism. (

Figure 4a). The survive rate of diploids and tetraploids were 62.22% and 61.11%, separately, with no significant difference (

Figure 4b). The fresh weight of tetraploid plants was 0.04 kg per plant, significant lower than diploids (P<0.01), which had a fresh weight of 0.14 kg per plant (

Figure 4c). the highest yield of diploid and tetraploid achieved at 0.25kg and 0.09kg per plant, respectively. The total fresh weight of harvested aboveground biomass of diploids and tetraploids were 16.18 kg and 4.97 kg, separately, with same field area.

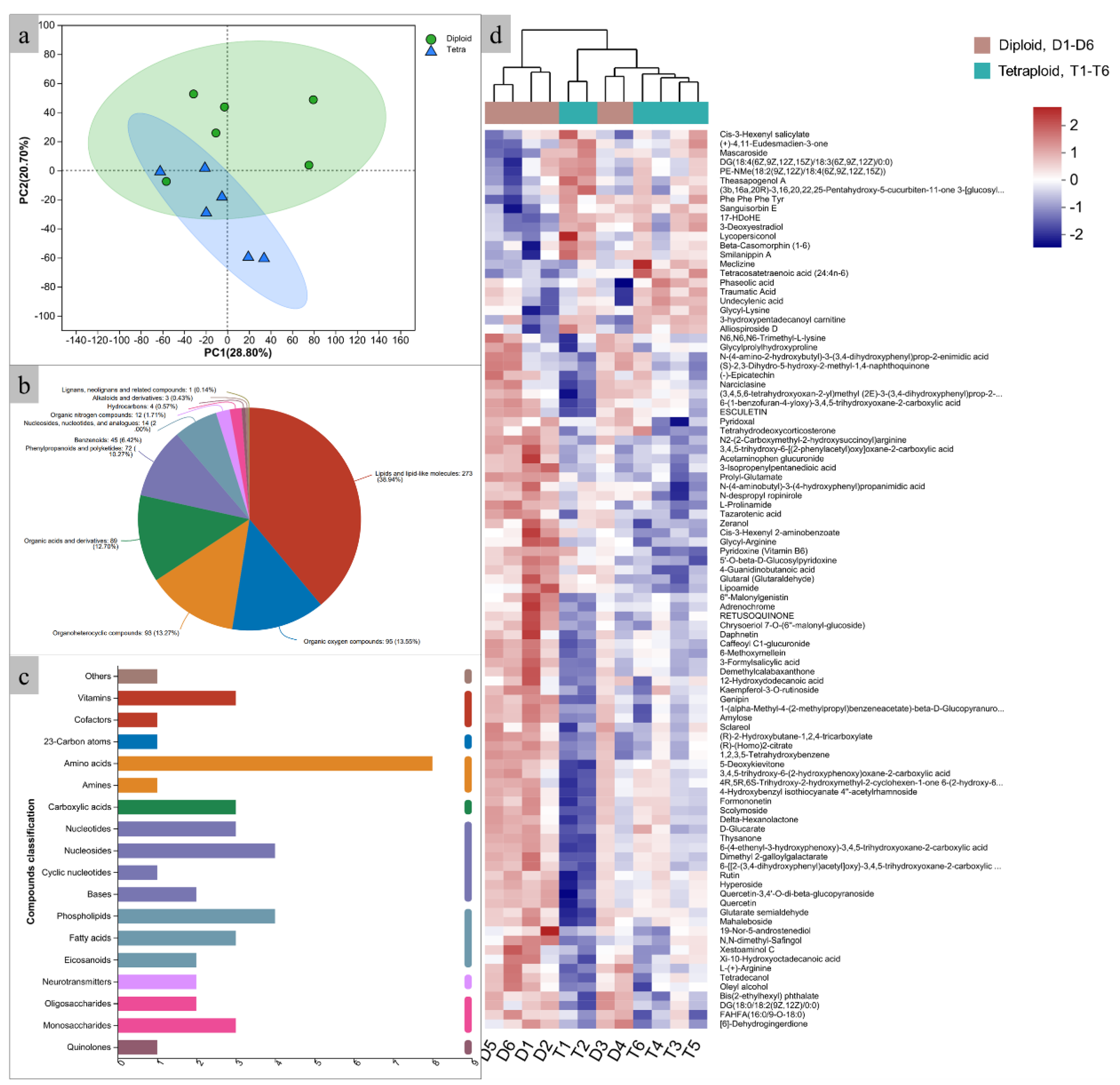

3.5. Metabolite Profile Changes in Tetraploids

To explore the metabolic profile extensively, LC-MS was employed to identify the metabolites in java ginseng leaves. The PCA analysis showed that diploids and induced tetraploids were clearly separated, indicating substantial differences in their metabolite content (

Figure 5a). After database searches, a total of 892 metabolites were identified, of which 701 identified by HMDB database and classified into eleven categories, including lipids and lipid-like molecules (38.94%), organic oxygen compounds (13.55%), organoheterocyclic compounds (13.27%), organic acids and derivatives (12.70%), phenylpropanoids and polyketides (10.27%), benzenoids (6.42%), nucleosides, nucleotides and analogs (2.00%), organic nitrogen compounds (1.74%), hydrocarbons (0.57%), alkaloids and derivatives (0.43%), lignans, neolignans and related compounds (0.14%) (

Figure 5b,

Table S1). Of the 294 metabolites identified by the KEGG database, only 43 could be classified into seven categories, which included nucleic acids (23.26%), lipids (20.93%), peptides (16.28%), carbohydrates (11.63%), vitamins and cofactors (9.30%), organic acids (6.98%), hormones and transmitters (4.65%), antibiotics (4.65%), steroids (2.33%), antibiotics (2.33%) (

Figure 5c). Compared with diploids, the content of 22 metabolites, such as mascaroside (27.99% increasing), undecylenic acid (15.19% increasing), and tetracosatetraenoic acid (11.51% increasing) are significantly increased (P<0.05) in tetraploids. While the content of 75 metabolites, such as formononetin (25.80% decreasing), epicatechin (22.49% decreasing), and 6-methoxymellein (18.84% decreasing) are significantly decreased (P<0.05) (

Figure 5d,

Table S2).

3. Discussion

Chemical reagents, particularly colchicine, are commonly used in plant polyploid breeding to double chromosome [

16,

17,

18]. In this study, induced tetraploids from axillary buds treated with colchicine were obtained, and the effects of the concentrations and exposure times were investigated for the first time. Eng and Ho [

19] suggested that the concentration of colchicine used for tetraploid induction ranges from 0.05% to 1.0%, and the treatment time varies from hours to weeks in different methods in different horticultural plants. In this study, the optimum concentration of colchicine is 1-3 mg/ml, and the optimum immersion time is 48 h, revealed that immersion time is more important than the concentration of colchicine, which inconsistent with other polyploid induction studies [

20,

21].

Polyploidization usually results in significant phenotypic changes in plants, such as cell enlargement, leaf thickening, changes in plant size and flower morphology, and alterations in fruit size [

22]. Consequently, obtaining desirable traits through polyploidy is a popular method in plant breeding. Tetraploidization of java ginseng brought about significant changes in plant structure, including leaf color, leaf shape, leaf thickness, size of flowers and fruits, and number of petals. All these changes are similar to the results of other polyploid induction studies, such as

Populus [

23,

24],

Callisia fragrans [

25], highbush blueberry [

26], wallflower [

27], and Manihot esculenta [

21].

Previous studies have proved that cell size increasing not always translate to the whole plant size increasing, for the amount of cell division in polyploids can be reduced, resulting in dwarfism in some species, including garlic [

28] and

Populus [

24]. Currently, it is believed that plant hormones play an important role in the causes of dwarfism caused by tetraploidization. In poplar [

24], the content of IAA and GA3 decreases and content of JA and ABA increases resulting in the dwarfing of tetraploids. In apple [

29], besides IAA, the decrease in the content of brassinosteroid (BR) is also one of the reasons. Dwarfism was also reported in this study, where the aboveground biomass of tetraploid of java ginseng was significantly lower than that of diploids, implying that increasing yield of java ginseng through chromosome doubling may need more tetraploidization testing. However, we did not find any differences in the content of the above-mentioned plant hormones between tetraploid and diploid plants. We speculated that the reason is that the collected leaves are mature and robust, have stopped growing and have not yet aged. At this point, the content of growth hormones has decreased, while the content of aging hormones has not yet increased, makes no difference in the content of plant hormones between diploids and tetraploids. This study is the first attempt to increase biomass by inducing tetraploid in java ginseng, although the expected results were not obtained, which has reference significance for future java ginseng breeding.

Increasing the content of functional metabolites is crucial for breeding medicinal plants. Chromosome doubling has been successfully carried out in various plants to enhance their metabolite content. In

Thymus persicus [

20], tetraploids obtained through exposure of shoot tip segments to colchicine showed an increase of 69.73%, 42.76%, and 140.67% in the content of betulinic acid, oleanolic acid, and ursolic acid, respectively, compared with diploids. In

Anoectochilus formosanus [

13], the leaf, stem, and whole plant of induced tetraploids produced more gastrodin and total flavonoid than the diploids. Artificial tetraploids of

Cannabis sativa [

12] were obtained by exposing axillary bud explants to oryzalin resulting in an increase of 9% in the content of cannabidol in buds. In the induced tetraploids of

Digitalis lanata [

30], the content of digitoxin and digoxin increased by 1.73-fold and 1.61-fold over the diploids respectively. In this study, we observed similar results in the content of 22 metabolites in tetraploid leaves that were significantly increased compared with diploids, such as naphthofurans, fatty acyls, steroids and derivatives, prenol lipids and so on. At present, the specific medicinal ingredients in java ginseng have not yet been identified, we cannot confirm whether these metabolites with increased content have significant value. However, the metabolomics study of its leaves and the impact of polyploidization on metabolite content are of great significance for its potential development and utilization.

Autotetraploid can be used as a parent for triploid breeding. As shown in other plants such as poplar [

31], rubber [

32,

33], and willow [

34], triploids exhibit better vitality and stress resistance than diploids, and we anticipate that triploid java ginseng may also have similar advantages. Hybridization between tetraploids and diploids is the direct pathway for producing triploids, and the tetraploids obtained in our study will contribute to the next stage of java ginseng polyploid breeding.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

Healthy and strong stems of wild java ginseng from same plant during its flowing time were sampled as explants in Danzhou, Hainan, China. Explants soaked in 75% ethanol for 30 seconds, then immersed in a 0.1% HgCl2 solution for ten minutes with continuous shaking to sterilize and washed with aseptic water 4-5 times. Sterilized stems divided into single node segments at 3-5cm length and half inserted in solid MS medium [

35]. Culture medium containing different concentrations of hormones for the induction of axillary bud germination. Before the medium autoclaving, the pH was adjusted to the range of 5.8-6.2. The entire cultivation process was carried out under 26°C, 2000 lx light, and a 14/10-hour light/dark cycle.

4.2. Culture Medium Selection and Polyploid Induction

To select the optimum culture medium for the induction of axillary bud germination, nine MS medium containing different concentrations of 6-Benzylamino Purine (6-BA, 0 ppm, 1.5 ppm, and 3 ppm), 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA, 0 ppm, 0.5 ppm, and 1 ppm), and Kinetin (KT, 0 ppm, 0.25 ppm, and 0.5 ppm), were used (

Table 1). After 20 days of incubation, the axillary bud germination rate was calculated, and the growth status of buds and roots were observed to evaluate the applicability of different culture medium for polyploid induction.

Single node segments at 2-3cm length from the medium selection stage were then immersed in liquid axillary bud germination induction medium for varying lengths of time (24 h, 48 h, and 72 h). The liquid medium was dissolved with colchicine at different concentrations (1 mg/ml, 2 mg/ml, and 3 mg/ml) to induce chromosome doubling. After rinsing with water, induced segments were transferred to the solid axillary bud germination induction medium to regenerate plantlets. Each treatment used 30 segments, and each treatment was repeated twice.

4.3. Flow Cytometry for Ploidy Identification

Flow cytometry was employed to analyze the ploidy of the induced plants. Fresh leaves of each induced plantlets in the tube were sampled and placed in plastic petri dish, added 500 µL of extraction buffer (Kobe, Hyōgo, Japan), then sectioned into splinter with a razor blade. Extracted nuclei were filtered through a filter with a pore size of 30 µm, and then mixed with 1.6 mL staining buffer containing 10 ppm of 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and 50 µg/mL RNase (Kobe, Hyōgo, Japan) was added to suspension to prevent staining of double-stranded RNA. After 30 seconds of incubation at room temperature, the samples were analyzed using CyFlow®Cube8 flow cytometry. The data obtained from flow cytometry was visualized using ModFit LT 3.1 (Inc, Verity Software House). Wild type of java ginseng was used as an internal standard.

4.4. Leaf Stomatal Analysis

The stomatal characters, as length, width, and density of mature leaves of tetraploid and diploid of java ginseng were measured using the finger-nail polish method [

36]. Clear finger-nail polish was painted on the back of the leaves. After drying, the polish was peeled off together with the epidermis and flattened on glass slides. Three photos of stomata were captured under an Olympus CX43 microscope with 40x objective for each leaf for stomatal length and width measurement, while photos for stomatal density measurement were taken under a 20x microscope objective. Three stomata were randomly selected in each photo to measure length and width in ImageJ (

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Stomatal density was count and calculated in the same software. Overall, 27 data of stomata’s length and width, and nine data of stomata’s density were obtained for each tetraploid and diploid, respectively. Three plants for each ploidy were random selected for leaf stomatal analysis.

4.5. Leaf Thickness Measurement

The thickness of the leaflets of tetraploids and diploids were measured using the paraffin section method. Mature leaves collected and soaked in FAA fixing solution at least 24 hours at 4℃ for fixation. After dehydration, vitrification and embedded in paraffin, the leaves were sectioned into 10–12µm and surveyed under an Olympus CX43 microscope, photographs were captured with an LV2000 digital camera. Thickness measurements were taken using ImageJ software.

4.6. Pollen Size Measurement

Anthers from bloomed male flowers were picked out and crushed with tweezers on a slide and stained by acetic acid magenta staining solution. Slides containing pollens were observed and photographed using the same microscope and photography system as leaf thickness measurement. Pollen diameters were measured using ImageJ software. At least 50 pollen grains were measured for both diploids and tetraploids.

4.7. Aboveground Biomass of Plantings

To compare the yield of aboveground biomass of diploid and tetraploid, four artificially induced tetraploid and four parental diploid plants were randomly selected as clones and planted in brick red soil by stem cutting. Each clone was planted with 30 plants in the form of 6 rows multiplied by 5 plants, with a plant spacing and row spacing of 5cm and 10cm, respectively. After 60 days of planting, the survival rate was counted, and the aboveground biomass was harvested. The fresh weight per row was weighed, and the average yield per plant was calculated by dividing the fresh weight per row by the number of plants per row.

4.8. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis was used to compare the metabolites content of mature leaves of six diploid plants (D1-D6) and six tetraploid plants (T1-T6). Fresh leaves with the same position and growth state on the stems of diploids and tetraploids were sampled. After washed with water, clean leaves were weighted and frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored in a -80°C refrigerator. Sampled leaves were then sent to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd for metabolite extraction and LC-MS analysis. The process of extracting metabolites is carried out in accordance with the company's internal technical standards. Briefly, 50 mg solid sample were accurately weighed, and the metabolites were extracted using a 400 µL methanol: water (4:1, v/v) solution with 0.02 mg/mL L-2-chlorophenylalanin as internal standard. The mixture was allowed to settle at -10 ℃ and treated by High throughput tissue crusher Wonbio-96c (Shanghai wanbo biotechnology co., LTD) at 50 Hz for 6 min, then followed by ultrasound at 40 kHz for 30 min at 5 ℃. The samples were placed at -20 ℃ for 30 min to precipitate proteins. After centrifugation at 13000 g at 4 ℃ for 15 min, the supernatant was carefully transferred to sample vials for LC-MS/MS analysis. As a part of the system conditioning and quality control process, a pooled quality control sample (QC) was prepared by mixing equal volumes of all samples. The QC samples were disposed and tested in the same manner as the analytic samples. During instrument analysis, insert a QC sample every 8 analytical samples to assess the repeatability of the entire analysis process.

The instrument platform for LC-MS analysis is UHPLC-Q Exactive system of Thermo Fisher Scientific. Chromatographic conditions: 2μL of sample was separated by BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 μm; Waters, Milford, USA) and then entered into mass spectrometry detection. The mobile phases consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile: isopropanol (1: 1, v/v) (solvent B). The solvent gradient changed according to the following conditions: from 0 to 3 min, 0% B to 20% B; from 3 to 9 min, 20% B to 60% B; from 9 to 11 min, 60% B to 100% B; from 11 to 13.5 min, 100% B to 100% B; from 13.5 to 13.6 min, 100% B to 0% B; from 13.6 to 16 min, 0% B to 0% B for equilibrating the systems. The sample injection volume was 20 µL and the flow rate was set to 0.4 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 ℃. During the period of analysis, all these samples were stored at 4 ℃. MS conditions: The mass spectrometric data was collected using a Thermo UHPLC-Q Exactive Mass Spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in either positive or negative ion mode. The electrospray capillary voltage, injection voltage and collision voltage were 1.0kV, 40V and 6eV, respectively. Ion source temperature and solvent removal temperature are 120℃ and 500℃ respectively, carrier gas flow rate was 900 L/h, mass spectrum scanning range was 50-1000m/z, and resolution was 30000. After the mass spectrometry detection is completed, the raw data of LC/MS is preprocessed by Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation,Milford, USA) software, and a three-dimensional data matrix in CSV format is exported. The information in this three-dimensional matrix includes: sample information, metabolite name and mass spectral response intensity. Internal standard peaks, as well as any known false positive peaks (including noise, column bleed, and derivatized reagent peaks), were removed from the data matrix, deredundant and peak pooled. At the same time, the metabolites were searched and identified, and the main database was the HMDB (

http://www.hmdb.ca/), Metlin (

https://metlin.scripps.edu/) and Majorbio Database.

The data after the database search is uploaded to the Majorbio cloud platform (

https://cloud.majorbio.com) for data analysis. Metabolic features detected at least 80 % in any set of samples were retained. After filtering, minimum metabolite values were imputed for specific samples in which the metabolite levels fell below the lower limit of quantitation and each metabolic feature was normalized by sum. To reduce the errors caused by sample preparation and instrument instability, the response intensity of the sample mass spectrum peaks was normalized by the sum normalization method, and the normalized data matrix was obtained. At the same time, variables with relative standard deviation (RSD) > 30% of QC samples were removed, and log10 logarithmization was performed to obtain the final data matrix for subsequent analysis.

Perform variance analysis on the matrix file after data preprocessing. The R package ropls (Version 1.6.2) performed principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal least partial squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and used 7-cycle interactive validation to evaluate the stability of the model. In addition, student's t-test and fold difference analysis were performed. The selection of significantly different metabolites was determined based on the Variable importance in the projeciton (VIP) obtained by the OPLS-DA model and the p-value of student’s t test, and the metabolites with VIP>1, p<0.05 were significantly different metabolites.

4.9. Data and Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA analysis was performed for length, width, and density of stomata, as well as leaf thickness, pollen size and aboveground biomass, using SPSS Statistics 22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that java ginseng segments as explants grown without hormones resulted in more vigorous buds and roots. The optimal conditions for tetraploid induction were segments immersed in a liquid medium containing 1-2 mg/ml colchicine for 48 h. Compared with diploids, tetraploids of java ginseng exhibited larger flowers, fruits, and pollens, as well as larger but fewer stomata. The aboveground biomass of tetraploids was significantly decreased compared with diploids. In the leaves of tetraploids, the content of 22 metabolites increased significantly (P<0.05), while that of 74 metabolites decreased significantly (P<0.05). This study investigated polyploid induction on java ginseng for the first time and compared differences in artificially induced tetraploid and diploid in multiple aspects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-Y.L. and Y.-Y.Z.; methodology, Y.-Y.L.; software, X.-S.G.; validation, Y.-Y.L., X.H. and Y.-Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.-Y.L.; investigation, Y.-Y.L.; resources, X.-S.G. and W.-G.L.; data curation, Y.-Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-Y.L. and Y.-Y.Z.; visualization, X.-F.Z.; supervision, Y.-Y.Z.; project administration, Y.-Y.Z.; funding acquisition, H.-S. H. and Y.-Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by China Agriculture Research System, grant number CARS-33-YZ2” and “Special Fund for Hainan Excellent Team 'Rubber Genetics and Breeding' , grant number 20210203”.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Menezes, F. D. A. B., Ishizawa, T. A., Souto, L. R. F., & Oliveira, T. F. Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn. leaves - source of nutrients, antioxidant and antibacterial potentials. Acta scientiarum polonorum. Technologia alimentaria 2021, 20(3), 253–263. [CrossRef]

- Moura, I.O., Santana, C.C., Lourenço, Y.R.F. et al. Chemical characterization, antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of the unconventional food plants: Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) leaf, major gomes (Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn.) and caruru (Amaranthus deflexus L.). Waste Biomass Valor 2021, 12, 2407–2431. [CrossRef]

- Sukwan, C., Wray, S., & Kupittayanant, S. The effects of Ginseng Java root extract on uterine contractility in nonpregnant rats. Physiological reports 2014, 2(12), e12230. [CrossRef]

- Manuhara, Y.W, Kristanti. A. N., Utami, E. S. W., Yachya, A. (2015). Effect of sucrose and potassium nitrate on biomass and saponin content of Talinum paniculatum Gaertn. hairy root in balloon-type bubble bioreactor. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 2015, 5(12), 1027-1032. [CrossRef]

- Valdés-González, J. A., Sánchez, M., Moratilla-Rivera, I., Iglesias, I., & Gómez-Serranillos, M. P. Immunomodulatory, anti-Inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties of ginseng: A pharmacological update. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 2023, 28(9), 3863. [CrossRef]

- Arman, A. Immunomodulator activity and anthirheumatoid arthritis extract of ethyl acetae ginseng bugis Talinum paniculatum (jactq.Gaertn). Journal of Global Pharma Tecnology 2020, 12, 246–251.

- Cerdeira, C.D., Da Silva, J.J., R. Netto, M.F., G. Boriollo, M.F., I. Moraes, G.O., Santos, G.B., C. Dos Reis, L.F., P. L. Brigagão, M.R., Talinum paniculatum: A plant with antifungal potential mitigates fluconazole-induced oxidative damage-mediated growth inhibition of Candida albicans. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm. 2020, 49. [CrossRef]

- Tolouei, S.E.L., Palozi, R.A.C., Tirloni, C.A.S., Marques, A.A.M., Schaedler, M.I., Guarnier, L.P., Silva, A.O., de Almeida, V.P., Manfron Budel, J., Souza, R.I.C., dos Santos, A.C., Silva, D.B., Lourenço, E.L.B., Dalsenter, P.R., Gasparotto Junior, A. Ethnopharmacological approaches to Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn. - Exploring cardiorenal effects from the Brazilian Cerrado. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2019, 238, 111873. [CrossRef]

- Souto, C.G.R.G., Lorençone, B.R., Marques, A.A.M., Palozi, R.A.C., Romão, P.V.M., Guarnier, L.P., Tirloni, C.A.S., dos Santos, A.C., Souza, R.I.C., Zago, P.M.J.J., Lívero, F.A. dos R., Lourenço, E.L.B., Silva, D.B., Gasparotto Junior, A. Cardioprotective effects of Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn. in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in hypertensive rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 281, 114568. [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, O.P., Lavania, U.C. Enhancing the productivity of secondary metabolites via induced polyploidy: A review. Euphytica 1996, 87, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Van de Peer, Y., Ashman, T.-L., Soltis, P.S., Soltis, D.E. Polyploidy: An evolutionary and ecological force in stressful times. The Plant Cell 2021, 33, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J.L., Martin, S.L., James, T., Golenia, G., Boudko, E.A., Hepworth, S.R., 2019a. Polyploidization for the genetic improvement of Cannabis sativa. Front. Front. Plant Sci. 10:476. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00476.

- Chung, H.-H., Shi, S.-K., Huang, B., Chen, J.-T. Enhanced agronomic traits and medicinal constituents of autotetraploids in Anoectochilus formosanus Hayata, a top-grade medicinal orchid. Molecules 2017, 22, 1907. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S.C., Goodger, J.Q.D., Chew, B.L., Cohen, T.J., Woodrow, I.E. Induction and characterisation of tetraploidy in Eucalyptus polybractea R.T. Baker. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 140, 111633. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Wang, J., Qiu, B., Ma, Z., Lu, T., Kang, X., Yang, J., 2022. Induction and Characterization of Tetraploid Through Zygotic Chromosome Doubling in Eucalyptus urophylla. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 870698. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.870698.

- Blakeslee, A.F., Avery, A.G., Methods of inducing doubling of chromosome in plants: by treatment with colchicine. Journal of Heredity 1937, 28, 393–411. [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A., Ahmad, T., Bashir, M.A., Hafiz, I.A., Silvestri, C. Studies on colchicine induced chromosome doubling for enhancement of quality traits in ornamental plants. Plants 2019, 8, 194. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, X., Huang, X., Li, W. Induction of tetraploid via somatic embryos treated with colchicine in Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.Juss.) Müll. Arg. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2022, 150, 487–491. [CrossRef]

- 19. Wee-Hiang Eng, Wei-Seng Ho. Polyploidization using colchicine in horticultural plants: A review. Scientia Horticulturae, 2019, 246, 604-617. [CrossRef]

- Tavan, M., Mirjalili, M.H., Karimzadeh, G. In vitro polyploidy induction: Changes in morphological, anatomical and phytochemical characteristics of Thymus persicus (Lamiaceae). Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2015, 122, 573–583. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Zeng, W., Yan, H. In vitro induction of tetraploids in cassava variety ‘Xinxuan 048’ using colchicine. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2017, 128, 723–729. [CrossRef]

- Sattler, M.C., Carvalho, C.R., Clarindo, W.R. The polyploidy and its key role in plant breeding. Planta 2016, 243, 281–296. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Sang, Y., Zhou, Q., Zhang, P. Colchicine in vitro tetraploid induction of Populus hopeiensis from leaf blades. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2020, 141, 339–349. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y., Zhang, S., Xu, T., Kang, X. Morphological, transcriptome, and hormone analysis of dwarfism in tetraploids of Populus alba × P. glandulosa. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9762. [CrossRef]

- Beranová, K., Bharati, R., Žiarovská, J., Bilčíková, J., Hamouzová, K., Klíma, M., Fernández-Cusimamani, E. Morphological, Cytological, and molecular comparison between diploid and induced autotetraploids of Callisia fragrans (Lindl.) Woodson. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2520. [CrossRef]

- Marangelli, F., Pavese, V., Vaia, G., Lupo, M., Bashir, M.A., Cristofori, V., Silvestri, C. In vitro polyploid induction of highbush blueberry through De Novo shoot organogenesis. Plants 2022, 11, 2349. [CrossRef]

- Fakhrzad, F., Jowkar, A., Shekafandeh, A., Kermani, M.J., moghadam, A. Tetraploidy induction enhances morphological, physiological and biochemical characteristics of wallflower (Erysimum cheiri (L.) Crantz). Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 308, 111596. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y., Liu, H., Meng, H., Qiao, L., Zhang, G., Cheng, Z. In vitro induction and phenotypic variations of autotetraploid garlic (Allium sativum L.) with dwarfism. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 917910. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Xue, H., Zhang, L., Zhang, F., Ou, C., Wang, F., Zhang, Z. Involvement of auxin and brassinosteroid in dwarfism of autotetraploid apple (Malus × domestica). Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26719. [CrossRef]

- Bhusare, B.P., John, C.K., Bhatt, V.P., Nikam, T.D. Induction of somatic embryogenesis in leaf and root explants of Digitalis lanata Ehrh.: Direct and indirect method. South African Journal of Botany 2020, 130, 356-365. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Qi, L., Chen, C., Li, X., Song, W., Chen, R., Han, S. A report of triploid Populus of the section Aigeiros. Silvae Genetica 2004, 53, 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Ao, S., He. L., Xiao. G., Chen. J., He. C. Selection of rubber cold fast and high-yield strains, Yunyan77–2 and Yunyan77–4. Journal of Yunnan Tropical Crops Science & Technology 1998, 21(2), 3–8. (In Chinese with English abstract).

- Li HB, Zhou TY, Ning LY, Li GH (2009) Cytological identification and breeding course of Hevea Yunyan77-2 and Yunyan77-4. J Trop Subtrop Bot 2009, 17(6), 602–605 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Serapiglia, M.J., Gouker, F.E., Smart, L.B., 2014. Early selection of novel triploid hybrids of shrub willow with improved biomass yield relative to diploids. BMC Plant Biology 14, 74. [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T., Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 1962, 15, 473–497. [CrossRef]

- Hamill, S.D., Smith, M.K., Dodd, W.A. In vitro induction of banana autotetraploids by colchicine treatment of micropropagated diploids. Aust. J. Bot. 1992, 40, 887–896. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).