1. Introduction

The goldspotted oak borer (hereafter GSOB),

Agrilus auroguttatus Schäffer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), is a wood borer that infests and kills several species of oak [

Quercus Linnaeus (Fagaceae)] in California and Arizona [

1,

2,

3].

In the past,

Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse was thought to consist of two subspecies:

Agrilus coxalis coxalis Waterhouse, found in southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, and

Agrilus coxalis auroguttatus Schäffer, restricted to Arizona and California in the USA. A subsequent morphological re-examination of the species complex based on male genitalia, allowed the splitting in two distinct species,

Agrilus auroguttatus and

Agrilus coxalis, found in Arizona and California, and Mexico and Guatemala respectively [

4]. Subsequently, Hespenheide et al. [

5] re-examined the species complex and, based on morphological characters (male genitalia), concluded that the American populations found in Arizona and California [

6] and the Mexican/Guatemalan forms actually constitute separate species with a distinct and original nomenclature. Specifically,

A. coxalis auroguttatus has been designated as

A. auroguttatus, whereas

A. coxalis coxalis has been renamed

A. coxalis. Thus, at present there are two closely related species [

3] with similar ecological behaviour but differing in distribution and ecological niches. It should be noted that

A. auroguttatus has also been found in Mexico as far as Guatemala [

6], which proves a greater distribution range than

A. coxalis.

Based on observations in Southern California, the majority of

A. auroguttatus populations complete one generation per year [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, it is likely that some individuals may exhibit longer or shorter generation times [

8], which could also depend on the vigor and health of host plants [

8,

11,

12]. The activity of adults is mainly recorded between May and September, with a significant increase and the peaks reached from late June to early July [

7,

10].

Agrilus auroguttatus is generally a pest of oaks, with a marked preference for species in the red oak group, such as

Quercus agrifolia and

Quercus kelloggii [

3,

13]. While other oak species are listed as major, minor, or laboratory hosts [

11,

13], it cannot be excluded that

A. auroguttatus might infest other plants belonging to the same botanical family (Fagaceae) or closely related families [

13]. Laboratory experiments have also demonstrated the insect’s ability to feed on

Quercus suber, although results regarding its capacity to complete its biological cycle on this species remain inconsistent [

11,

14]. In California, the presence of

A. auroguttatus has been linked to the decline of oak populations, where it co-occurs with other pathogens and pests, such as the fungus

Diplodia corticola [

14,

15]. This simultaneous presence exacerbates tree stress and mortality, highlighting the importance of integrated pest management strategies to mitigate the impacts of this invasive species on oak ecosystems. Uncertainties remain, however, for all red oak species of American origin planted in Europe as well as for new endemic European species in a scenario of a new introduction of this buprestid from its current range [

13].

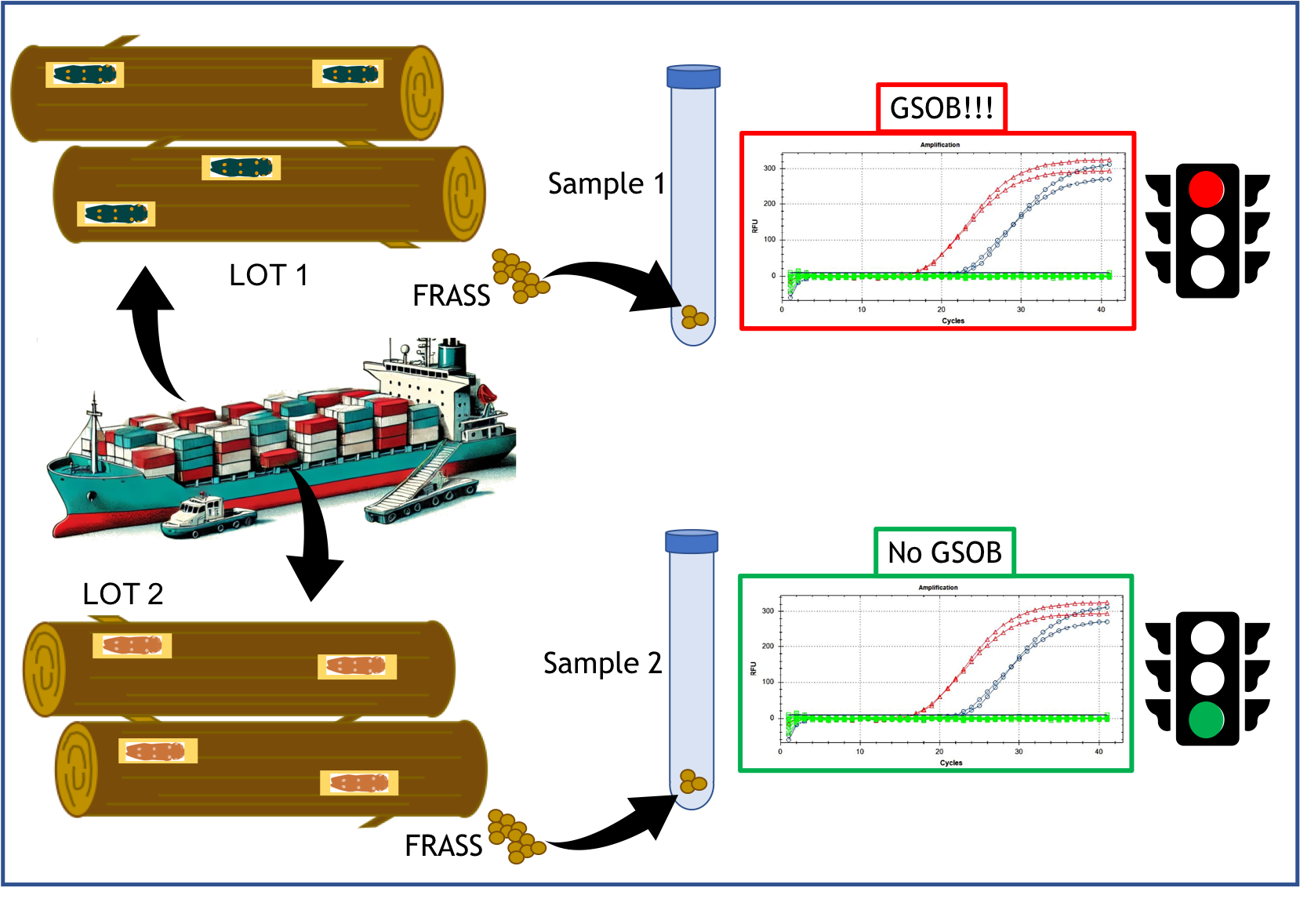

Due to the potential phytosanitary risk of handling A. auroguttatus, a molecular test capable of quickly and with certainty discriminating the species from other Agrilus or similar insects could be very useful where inspections are required on trees and/or timber in import/export or on symptoms in territorial surveys. Visual verification or morphological identification by inspection staff (e.g. phytosanitary agents) is often challenging due to the required entomological expertise and the invasive nature of the techniques needed to locate specimens within woody tissues. Frequently, it becomes necessary to damage the woody tissues of a plant to uncover larvae or pupae. This invasive approach not only devalues the product—particularly in the case of ornamental plants and bonsai—but may also have significant indirect consequences. Sampling points in the wood can serve as entry sites for other pathogens, and in smaller or younger plants, the resulting damage may compromise structural stability. In contrast, indirect diagnostic methods based on alternative residues could accelerate inspections and controls at both regional and cross-border levels.

Among these methods, the use of frass in diagnostics is gaining traction in the field of plant health due to its practicality and low (sometimes zero) invasiveness [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Building on these observations, this study proposes a diagnostic protocol for the specific identification of A. auroguttatus from various matrices (adults and frass) using a TaqMan qPCR assay.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

Specimens of

A. auroguttatus were obtained from the University of California, Riverside, Department of Entomology. The specimens consisted of morphologically identified adults and larvae, and frass and fecal residues collected from infested trees. In addition, non-target specimens, were included in the performed analysis (

Table S1) and consist both of genetically related species affecting or not affecting the same host plants (

Agrilus spp.) and other species of xylophagous pests.

Each insect specimen was stored in 70% ethanol. When necessary, the specimens used in the test were morphologically identified through entomological identification keys [

4,

21].

2.2. DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from all target and non-target insects listed in

Table S1. Each specimen was used as a template for two DNA extractions (in duplicate).

Genomic DNAs relating to individual specimens (adults and larvae) were extracted using an extraction method based on 2% CTAB buffer with preliminary digestion with Proteinase K and RNaseA [

16]. In detail, each insect stage was individually ground and homogenized with 3 mm diameter tungsten beads for 10 seconds at a low speed (20 oscillations/s). 500 µL of 2% CTAB was added to the obtained lysate with the supplement of 40 µL of Proteinase K (Qiagen, Hilden, DE) and 8 µL of RNase A (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and then incubate 30 minutes at 60°C. After the incubation, 1 volume of chloroform was added and centrifuged at 20,000 g at 4°C for 10 min. Next, 500 µL of the top phase was extracted and mixed with an equal amount of isopropanol. After centrifuging at 20,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, 500 µL of 70% ethanol was added to the pellet obtained. Then the pellet was resuspended in 100 µL of nuclease-free sterile water. As regards the frass and fecal residues (from an initial amount of about 20 mg), the methods of extraction of the nucleic acids were different and took place according to what was reported by [

19].

To enable precise quantification of DNA and determine the limit of detection (LoD) for

A. auroguttatus in frass, an approach that is not feasible with natural frass due to the minimal proportion of GSOB DNA in the total DNA [

20], further artificial frass was produced. This was created by using frass from

Aromia bungii (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and adding a known amount of DNA from GSOB adults. Specifically, the artificial frass was composed of DNA extracted from

A. auroguttatus adults mixed into 20 mg of frass produced by

A. bungii feeding on

Prunus armeniaca, resulting in a final DNA concentration of 0.1 ng/µL. This concentration was chosen to match the volumes required for subsequent nucleic acid extraction steps. The QiaExpert instrument (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used both to quantify both to evaluate the degree of contamination of the extracted DNAs. The DNA obtained was normalized to 10 ng/µL and used for qPCR reactions immediately or stored at -20°C until use.

To assess the quality of the DNA extracted from insects, the DNA was subjected to a real-time PCR reaction using a dual-labelled probe designed to target a highly conserved region of the 18S rDNA [

22]. This amplifiability test acts as both a control for the extractions and a check for inhibitors through the analysis of Cq values and slopes of amplification curves.

2.3. Design of the Primers and Probe for qPCR Assay

The software OligoArchitectTM Primers and Probe Design On Line (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) were used to design the primers and probe required in the qPCR. The mitochondrial conserved region of GSOB were used as a basis, and the parameters were setting as follow: product size 80 to 160 bp, Tm (melting temperature) 50 to 65°C, primer length of 16 to 28 bp, and absence of secondary structures whenever possible. The primers and probe (

Table 2) were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany).

BLAST software (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool;

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST; accessed on 21 December 2024) was employed to perform an in-silico test to assess the specificity of the primer pairs and probe (

Table 2). Using the expected amplicons of the qPCR Probe protocol as queries, the most related nucleotide sequences available in the database were aligned using the MAFFT program [

23] implemented within Geneious® 10.2.6 (Biomatters,

http://www.geneious.com). The final alignments (SM 1 and SM 2) compared in total 38 different

Agrilus species including

A. coxalis, the genetically very close species.

The optimal primers and probe concentrations and annealing temperatures for the qPCR amplification were determined following the evaluation conducted in Rizzo et al. [

24] (temperature gradient: 55 to 62°C – concentrations: 0.2 to 0.5 µM).

2.4. qPCR Probe: Validation Method

The performance criteria such as analytical sensitivity, analytical specificity, repeatability, and reproducibility were determined to assess the usability of the tests for routine diagnostics and validate the method according to standard criteria ISO 16140: 2003 and the PM7/98-5 [

25].

The determination of the limit of detection (LoD) was assessed through the analytical sensitivity of the qPCR probe test using DNA from a single sample (adult, frass, artificial frass, fecal residues) at a starting concentration of 5 ng/µL serially diluted in triplicate (10-fold 1:5). The analytical sensitivity assessment included dilutions between 2 ng/µL and 25.6 fg/µL. The methodology described in Rizzo et al., 2021 was implemented to assess the intra-run variation (repeatability) and inter-run variation (reproducibility). For both repeatability and reproducibility, as a statistical data, only the percentage variation coefficient was taken into consideration, referring to two series of samples (8 DNA extracts from adult specimen and 8 DNA extracts from “artificial frass” of

A. auroguttatus). The repeatability referred both to the DNA extracted from adult

A. auroguttatus and from "artificial frass" occurred at a low concentration (as required by PM7/98-5 [

25]), close to the limit of detection. In this case the DNA extracts were normalized to the concentration of 0.04 ng/µL. Reproducibility was performed exactly (each series was processed in triplicate) as for repeatability except at different times and with different operators.

3. Results

3.1. DNA Extraction

The results of DNA extraction performed on different samples of

A. auroguttatus are reported in

Table 3 with average concentrations (ng/µL) and the corresponding standard deviations (SD), along with the absorbance ratios (A260/280) and Cq values in real-time PCRs targeting the 18S gene. The Cq values of

A. auroguttatus samples with the primers and probe here designed ranged from 27.9 to 32.6 (

Table 3).

3.2. Assay Conditions of the TaqMan Probe Protocol

The optimal reaction mix for the TaqMan Probe qPCR includes 10 µL of 2x QuantiNova PCR Master Mix Probe (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with the primer concentrations set at 0.4 µM, and the probe concentration at 0.2 µM.

The optimal annealing temperature for the real-time PCR assay was determined to be 58°C. For the probe assay, samples were considered positive if the resulting real-time PCR amplification curves displayed a clear inflection point, accompanied by increasing kinetics, and if the Cq values were <37.

3.3. Methods Validation

The here developed test demonstrated inclusivity for A. auroguttatus, effectively detecting and identifying this species. Furthermore, the test exhibited exclusivity by accurately distinguishing it from all the evaluated non-target organisms (Tab. S1). The limit of detection was outlined to be 8 pg/µL for DNA from GSOB adults with corresponding mean Cq value equal to 35.14 ± 0.71.

The LoD of "artificial frass" was equal to the fourth dilution 1:5 at a concentration of 0.08 ng/µL of total DNA, with a relative average Cq of 37.07 ± 0.59.

The test showed to have linearity (R2) of 0.998, demonstrating that the Cq values are strongly dependent on the DNA concentration of the sample.

The qPCR probe protocol demonstrated 100% repeatability and reproducibility, with standard deviations never exceeding 0.5, indicating low intra- and inter-specific variability. For repeatability, the mean Cq value was 30.26 ± 0.33, while for reproducibility, the mean Cq value was also 30.26 ± 0.33.

4. Discussion

For decades, the globalization of international trade has facilitated the spread of alien organisms harmful to plants and their products, leading to the introduction of invasive insect species in new regions, often with disastrous consequences [

26,

27]. As a result, xylophagous insects that pose low or negligible phytosanitary risks in their native regions can cause significant economic and phytosanitary impacts when introduced elsewhere. Risk assessments are often uncertain regarding diffusion capacity and speed, handling, and host plant range. These uncertainties highlight the need for prompt detection and swift management of new outbreaks [

28,

29].

Rapid diagnosis of alien insects after accidental introduction is essential for effective management. Indirect diagnostic methods, such as detecting genetic traces in frass, fecal residues, and exuviae, can accelerate detection and delimitation of newly introduced insects in uncharted areas. This approach reduces phytosanitary risks and limits the spread of invasive species.

Morphological recognition, by contrast, often requires specialized entomological skills that may not be immediately available, as well as lengthy and complex sample preparation for microscopic examination. This process is particularly challenging across developmental stages or when identifying insects within woody tissues and can be time-consuming and destructive to infested or suspect plants.

The European Community has identified

Agrilus auroguttatus as a high-risk species for introduction [

14]. The biomolecular tool developed in this study is crucial for managing potential outbreaks or interceptions at entry points. This tool enables rapid diagnosis through indirect detection of genetic traces, such as frass or fecal residues, from insects at different life-cycle stages. Recent advancements in biomolecular diagnostic tools have significantly enhanced the direct [

30] and indirect identification of harmful organisms through biological traces like frass [

16,

17,

19,

31].

The success of diagnostic investigations depends heavily on the type and performance of nucleic acid extraction protocols. Effective protocols must yield highly purified DNA and be both fast and reproducible. The extraction methods used in this study (one for adult insects and another for frass and fecal residues) demonstrated their effective-ness, as shown previously for other harmful insects using diverse starting materials [

16,

17]. The DNA yields and purity (A260/280 ratios) were satisfactory and aligned with the requirements of the assay.

The qPCR assay developed in this study employs dual-labeled probe technology. While this technique involves complex design and higher costs (albeit declining in recent years, [

32], it remains widely used due to its high specificity at the target sequence level.

The molecular assay developed for GSOB has proven effective in terms of analytical specificity, sensitivity, reliability, and reproducibility. In-silico verification of the amplicon showed excellent specificity, and comparisons of COI sequences with the closely related species A. coxalis revealed sufficient variability to ensure accurate discrimination. In vivo tests with reference materials from non-target Agrilus species validated the in-silico findings.

The LoD assay for adult insects (8 pg/µL) was lower than expected, probably due to PCR inhibitors such as hemolymph in the sample matrix. This issue was not observed in "artificial frass" or leg samples, which showed better qualitative and quantitative results, reflected in more efficient Cq values. Based on the LoD normalized to a starting DNA concentration of 5 ng/µL in "artificial frass" (woody fraction + insect frass), the detection limit for insect DNA in natural samples may be higher due to inhibitors in the starting matrix.

The proposed method complements morphological identification and is particularly valuable for territorial surveys and delimiting new outbreaks. It provides a rapid, efficient screening tool for xylophagous insects at entry points, high-risk sites, or directly in the field during infestations. The here developed protocol represents a significant advancement in the management of A. auroguttatus, particularly in regions like Europe, where the risk of introduction or spread of this quarantine organism is high. By detecting faint environmental traces akin to “fingerprints” of the organism, this method enhances early detection and intervention efforts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on:

Preprints.org,

Table S1: Samples (target and non-target specimens) used in this study (UoF = University of Florence, Italy; IIB = Istituto Iulius Brema, Germany; UoP = University of Pisa, Italy; UCR = University of California, Riverside, USA; UoN = University of Naples, Italy; PPS-T= Plant Protection Service_Tuscany, Italy; PPS-T-PLI= Plant Protection Service_Tuscany, Interception at Port of Leghorn, Tuscany, Italy. CREA_DC = Consiglio per la Ricerca in Agricoltura e la analisi dell’Economica Agraria, Italy; PPS-C = Plant Protection Service_Campania, Italy; PPS-L= Plant Protection Service_Lumbardy, Italy). A: Adult; L: Larva; F: Frass; FR: Fecal residues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and M.M.; methodology, D.R. and F.N.; software, D.R. and M.C.; validation, M.M., L.B., B.P., C.G.Z., A.M., C.R. and M.C.; formal analysis, M.M. and D.R.; investigation, D.R., M.M. and F.N. ; data curation, D.R., M.M. and F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R. L.B., B.P., C.G.Z., A.M., C.R. and F.N.; writing—review and editing, D.R., M.M., L.B., B.P., C.G.Z., A.M., C.R., M.C. and F.N.; visualization, F.N.; resources, D.R. and F.N.; supervision, D.R.; project administration, F.N. and D.R.; funding acquisition, F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

this research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

the raw data presented in this study are available at Laboratory of Phytopathological Diagnostics and Molecular Biology, Plant Protection Service of Tuscany, Via Ciliegiole 99, 51100 Pistoia, Italy and are available on request to Domenico Rizzo, domenico.rizzo@regione.toscana.it.

Acknowledgments

special thanks go to Mark Hoddle and Joelena Tamm, University of California, Riverside (USA) for providing the specimens of A. auroguttatus from California.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coleman, T.W.; Seybold, S.J. New pest in California: the goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse. Pest Alert R5-RP-022. 2008, Available online: ucanr.edu/sites/gsobinfo/files/106965.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Coleman, T.W.; Seybold, S.J. Previously unrecorded damage to oak, Quercus spp., in southern California by the goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). Pan-Pac. Entomol 2008, 84, 288-300. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, T.; Seybold, S. Insects and Diseases of Mediterranean Forest Systems. In Insects and Diseases of Mediterranean Forest Systems; Springer: Cham, 2016; pp. 663–697. [CrossRef]

- Hespenheide, H.A.; Bellamy, C.L. New Species, Taxonomic Notes, and Records for Agrilus Curtis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) of Mexico and the United States. Zootaxa 2009, 2084, 50-68. [CrossRef]

- Hespenheide, H.A.; Westcott, R.L.; Bellamy, C.L. Agrilus Curtis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) of the Baja California Peninsula, México. Zootaxa 2011, 36–56. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, T.W.; Seybold, S.J. Collection History and Comparison of the Interactions of the Goldspotted Oak Borer, Agrilus auroguttatus Schaeffer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), with Host Oaks in Southern California and Southeastern Arizona, U.S.A. Coleopt. Bull. 2011, 65, 93–108. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, V.; McClanahan, M.; Graham, L.; Hoddle, M. Assessing the flight capabilities of the goldspotted oak borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) with computerized flight mills. J. Econ. Entomol 2014, 107, 1127-1135. [CrossRef]

- Haavik, L.J.; Coleman, T.W.; Flint, M.L.; Venette, R.C.; Seybold S.J. 2013. Agrilus auroguttatus (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) seasonal development within Quercus agrifolia (Fagales: Fagaceae) in southern California. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2013, 106, 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Seybold, S.J.; Coleman, T.W.; Service, U.F.; Protection, F.H.; Bernardino, S. The Goldspotted Oak Borer: An Overview of a Research Program for “California’s Emerald Ash Borer”. USDA Res. Forum Invasive Species GTR 2010, 2010.

- Seybold, S.J.; Coleman, T.W. The Goldspotted Oak Borer: Revisiting the Status of an Invasive Pest Six Years After Its Discovery. In Proceedings of the 7th California Oak Symposium: Managing Oak Woodlands in a Dynamic World stage; 2014; pp. 285–305.3–6 Nov 2014. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report, PSW-GTR-251, Visalia, pp 285‒305, 579 pp.

- Haavik, L.J.; Graves, A.D.; Coleman, T.W.; Flint, M.L.; Venette, R.C.; Seybold, S.J. Suitability of native and ornamental oak species in California for Agrilus auroguttatus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2014, 150, 86–97. [CrossRef]

- Flint, M.L., Jones, M.I., Coleman, T.W., Seybold, S.J. Goldspotted oak borer. University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program, Davis, California, Agriculture and Natural Resources, Pest Notes, Publication 74163, Oakland, California, 2013, Available online: www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn74163.html (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- EPPO. EPPO Global Database. Mini data sheet on Agrilus auroguttatus. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/download/doc/987_minids_AGRLGT.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- EFSA; Schrader, G.; Kinkar, M.; Vos, S. Pest Survey Card on Agrilus Auroguttatus. EFSA Support. Publ. 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Pinna, C.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Deiana, V.; Maddau, L.; Montecchio, L.; Lentini, A. Plant pathogenic fungi associated with Coraebus florentinus (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) attacks in declining oak forests. Forests 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Taddei, A.; Da Lio, D.; Nugnes, F.; Barra, E.; Stefani, L.; Bartolini, L.; Griffo, R.V.; Spigno, P.; Cozzolino, L.; et al. Identification of the Red-Necked Longhorn Beetle Aromia bungii (Faldermann, 1835) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) with real-Time PCR on frass. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6041. [CrossRef]

- Taddei, A.; Becker, M.; Berger, B.; Da Lio, D.; Feltgen, S.; König, S.; Hoppe, B.; Rizzo, D. Molecular Identification of Anoplophora Glabripennis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and Detection from Frass Samples Based on Real-Time Quantitative PCR. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 1587–1601. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Moricca, S.; Bracalini, M.; Benigno, A.; Bernardo, U.; Luchi, N.; Da Lio, D.; Nugnes, F.; Cappellini, G.; Salemi, C.; et al. Rapid Detection of Pityophthorus Juglandis (Blackman) (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) with the Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (Lamp) Method. Plants 2021, 10, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Da Lio, D.; Bartolini, L.; Salemi, C.; Pennacchio, F.; Rapisarda, C.; Rossi, E The Rapid Identification of Anoplophora chinensis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) from adult, larval, and frass samples using TaqMan probe assay. J. Econ. Entomol 2021, 114, 2229-2235. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Da Lio, D, Zubieta, C.G.; Ranaldi, C.; Marrucci, A.; Stabile, I.; d'Agostino, A.; Bartolini, L.; Rapisarda, C.; Pennacchio, F.; Rossi, E. A duplex real-time PCR with TaqMan probes for the distinction of Anoplophora chinensis (Forster) and Anoplophora glabripennis (Motschulsky) on different biological matrices. EPPO Bull. 2023, 53, 652-662. [CrossRef]

- Švácha, P.; Danilevsky, M.L. Cerambycoid larvae of Europe and Soviet Union (Coleoptera, Cerambycoidea). Part II. Acta Univ. Carolinae Biol. 1988, 31, 121–284.

- Ioos, R.; Fourrier, C.; Iancu, G.; Gordon, T.R. Sensitive detection of Fusarium circinatum in pine seeds by combining an enrichment procedure with a Real-Time PCR using dual-labeled probe chemistry. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 582–590. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Zubieta, C.G.; Sacchetti, P.; Marrucci, A.; Miele, F.; Ascolese, R.; Nugnes, F.; Bernardo, U. Diagnostic tool for the identification of Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) (Diptera: Tephritidae) using Real-Time PCR. Insects 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- EPPO. PM 7/98 (5) Specific requirements for laboratories preparing accreditation for a plant pest diagnostic activity. EPPO Bull. 2021, 49. [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Invasive Alien Species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1511–1534. [CrossRef]

- Seebens, H.; Blackburn, T.M.; Dyer, E.E.; Genovesi, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Jeschke, J.M.; Pagad, S.; Pyšek, P.; Winter, M.; Arianoutsou, M.; et al. No Saturation in the Accumulation of Alien Species Worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Poland, T.M.; Rassati, D. Improved Biosecurity Surveillance of Non-Native Forest Insects: A Review of Current Methods. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 37–49. [CrossRef]

- Rassati, D.; Faccoli, M.; Marini, L.; Haack, R.A.; Battisti, A.; Petrucco Toffolo, E. Exploring the Role of Wood Waste Landfills in Early Detection of Non-Native Wood-Boring Beetles. J. Pest Sci. 2015, 88, 563–572. [CrossRef]

- Augustin, S.; Boonham, N.; De Kogel, W.J.; Donner, P.; Faccoli, M.; Lees, D.C.; Marini, L.; Mori, N.; Petrucco Toffolo, E.; Quilici, S.; et al. A Review of Pest Surveillance Techniques for Detecting Quarantine Pests in Europe. EPPO Bull. 2012, 42, 515–551. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Zubieta, C.G.; Carli, M.; Marrucci, A.; Ranaldi, C.; Palmigiano, B.; Bartolini, L.; Pennacchio, F.; Bracalini, M.; Garonna, A.P.; Panzavolta, T.; Moriconi, M. Rapid identification of Ips sexdentatus (Boerner, 1766) (Curculionidae) from adults and frass with real-time PCR based on probe technology. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2024, 131, 1473–1481. [CrossRef]

- Tajadini, M.; Panjehpour, M.; Javanmard, S.H. Comparison of SYBR Green and TaqMan methods in quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction analysis of four adenosine receptor subtypes. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2014, 3, 85. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

List of the primers and probe used in the study on A. auroguttatus.

Table 2.

List of the primers and probe used in the study on A. auroguttatus.

| Primer/Probe Name |

Sequence 5’-3’ |

Product size (bp) |

Reference Sequence |

| Aaur_411F |

CTGGAATTTCTTCAATTTTGG |

134 |

JF719868.1 |

| Aaur_589R |

GTCAGTTAGTAGCATAGTAATAG |

| Aaur_449P |

FAM_ACTACCGTAATTAACATGCGAGCC_BHQ1 |

Table 3.

Average concentrations of the extracted DNA (± SD) and range of values, absorbance ratio (A260/280), Cq values of 18S gene and Aaur_449P probe for A. auroguttatus assayed samples. n.a.: not available value.

Table 3.

Average concentrations of the extracted DNA (± SD) and range of values, absorbance ratio (A260/280), Cq values of 18S gene and Aaur_449P probe for A. auroguttatus assayed samples. n.a.: not available value.

| Sample |

DNA Concentration (ng/µL) ± SD

[Min-Max values] |

A260/280 ratio |

Cq (18S) |

Cq qPCR Probe |

| Adult |

103.1 ± 70.96

[35.0 – 171] |

1.7 ± 0.11 |

28.4 ± 0.64 |

27.9 ± 0.11 |

| Frass |

34.6

[n.a.] |

1.9 |

21.6 ± 0.51 |

31.6 ± 0.24 |

| Fecal residue |

86.5

[n.a.] |

1.8 |

24.8 ± 0.84 |

29.5 ± 0.14 |

| Artificial frass (n=8) |

27.2 ± 1.0

[26.2 – 28.2] |

1.9 ± 0.06 |

19.5 ± 0.25 |

32.6 ± 0.06 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).