Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Sequence Analysis of the P5CS Gene Family in Cotton

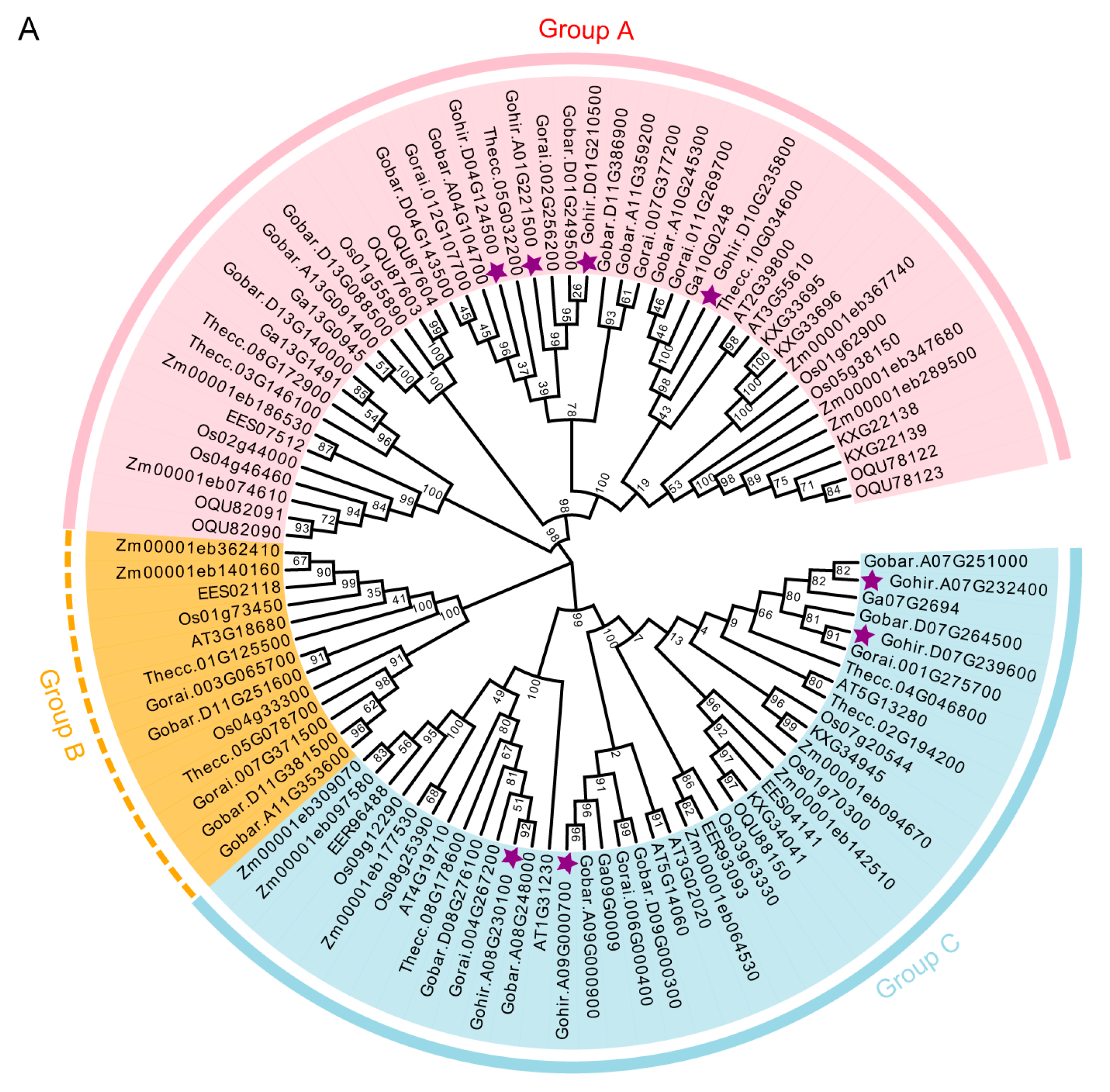

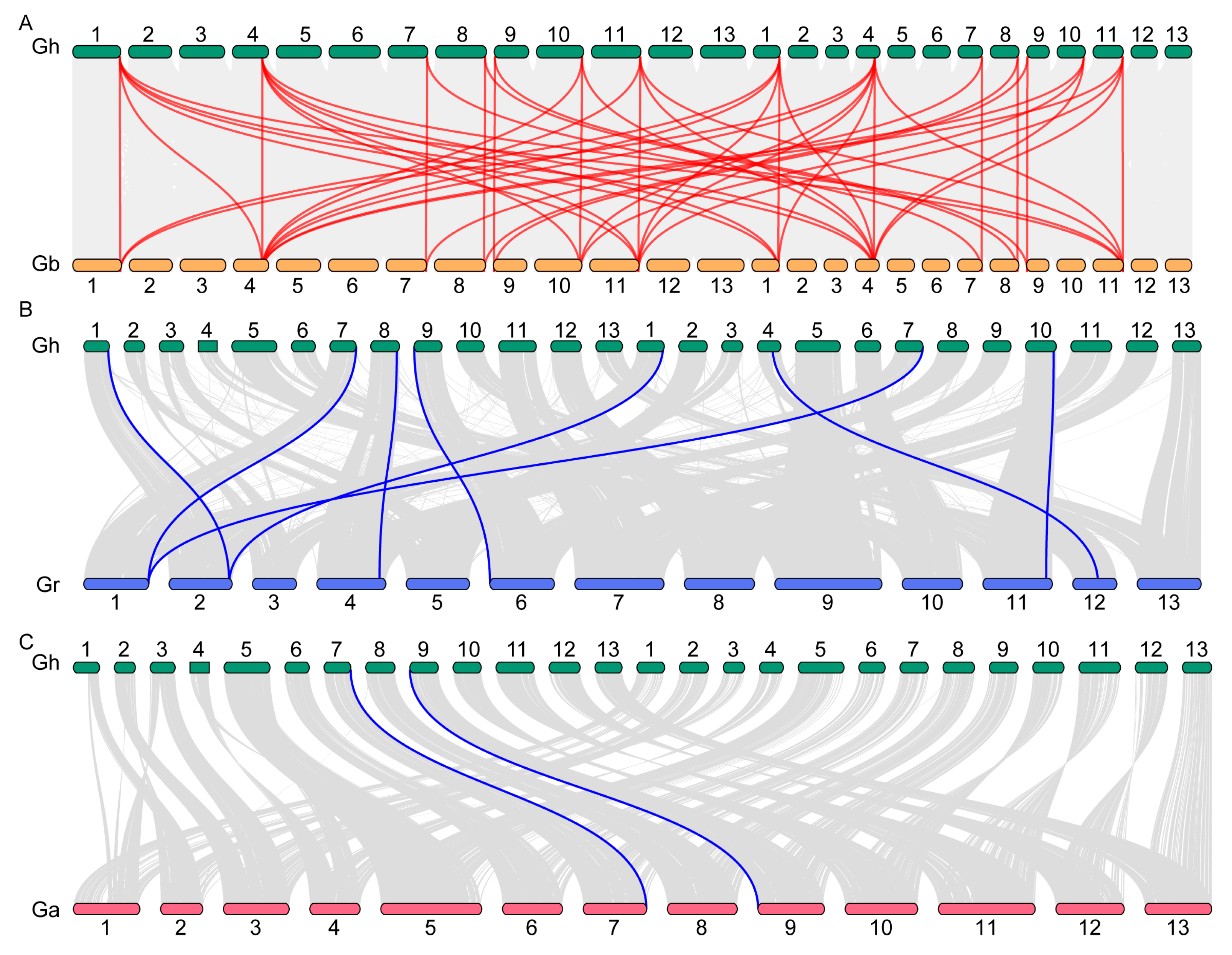

2.2. Evolutionary and Selection Analysis of P5CS Genes in Cotton

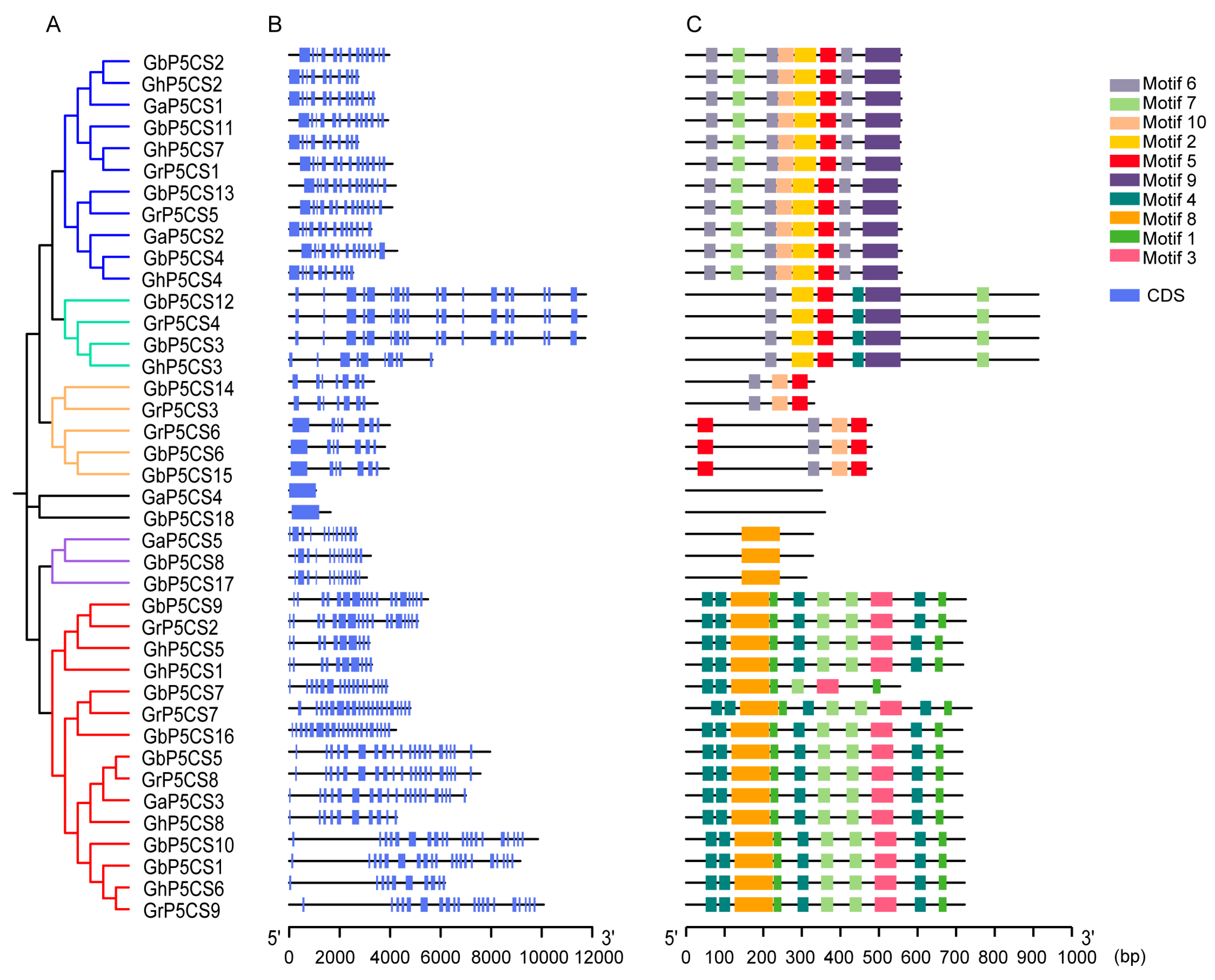

2.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of P5CS Genes in Cotton

2.4. Analysis of the Subcellular Localization of the P5CS Proteins in Cotton

2.5. Cis-Acting Element Analysis of the P5CS Gene Promoters in Cotton

2.6. Secondary Structure Prediction and Three-Dimensional Modeling of the GhP5CS Proteins

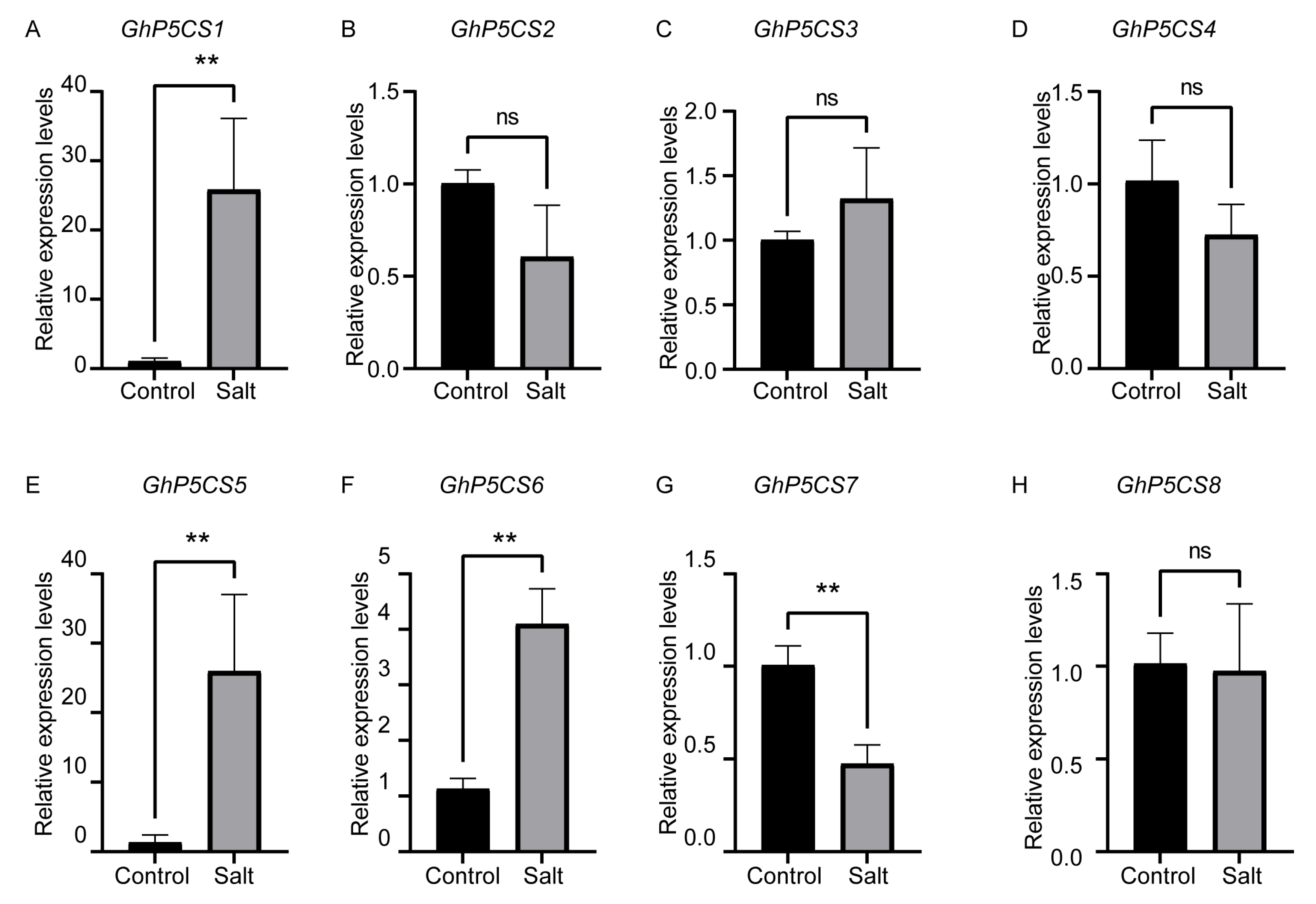

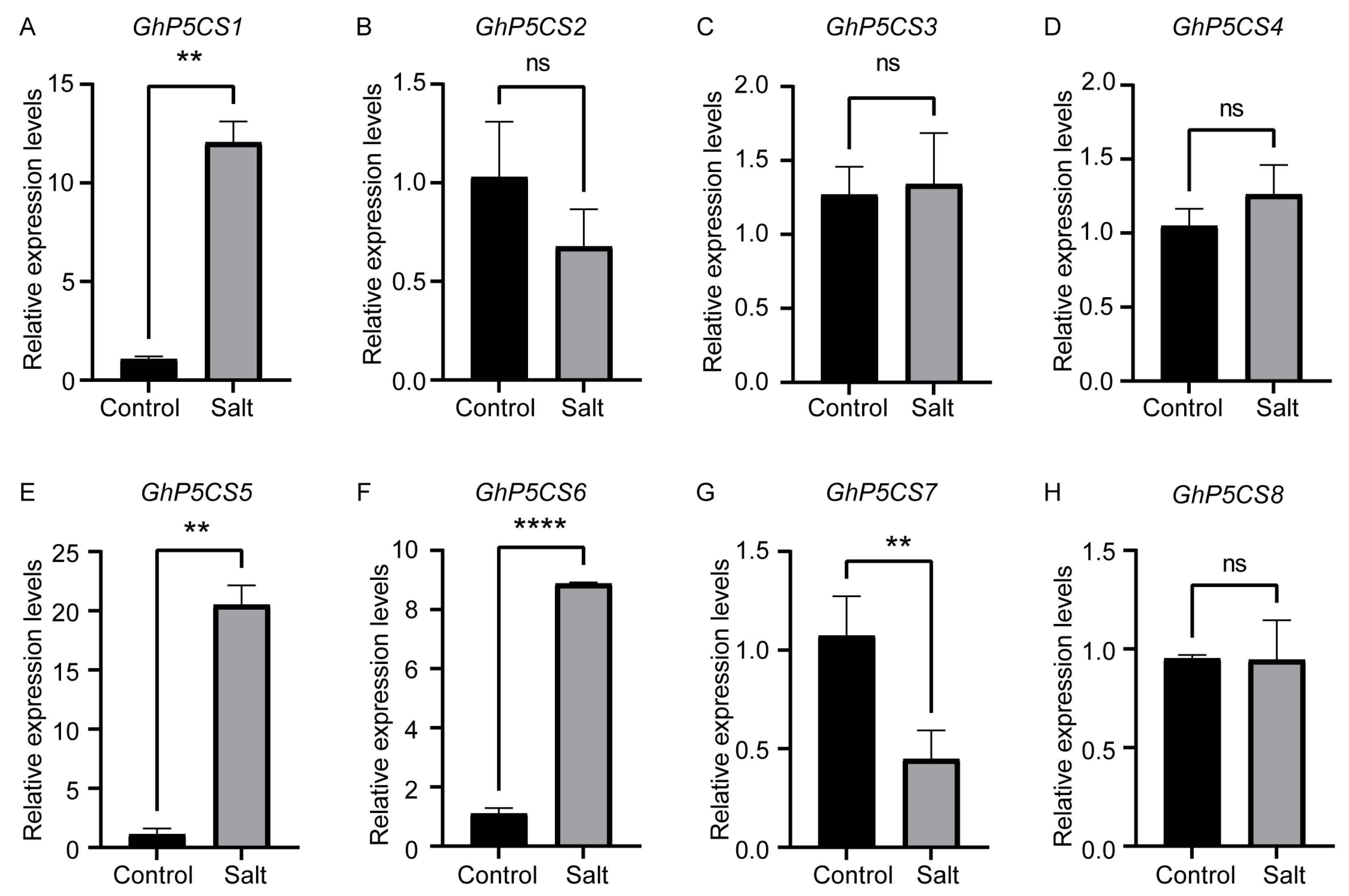

2.7. Expression Patterns of GhP5CS Genes Under Salt Stress

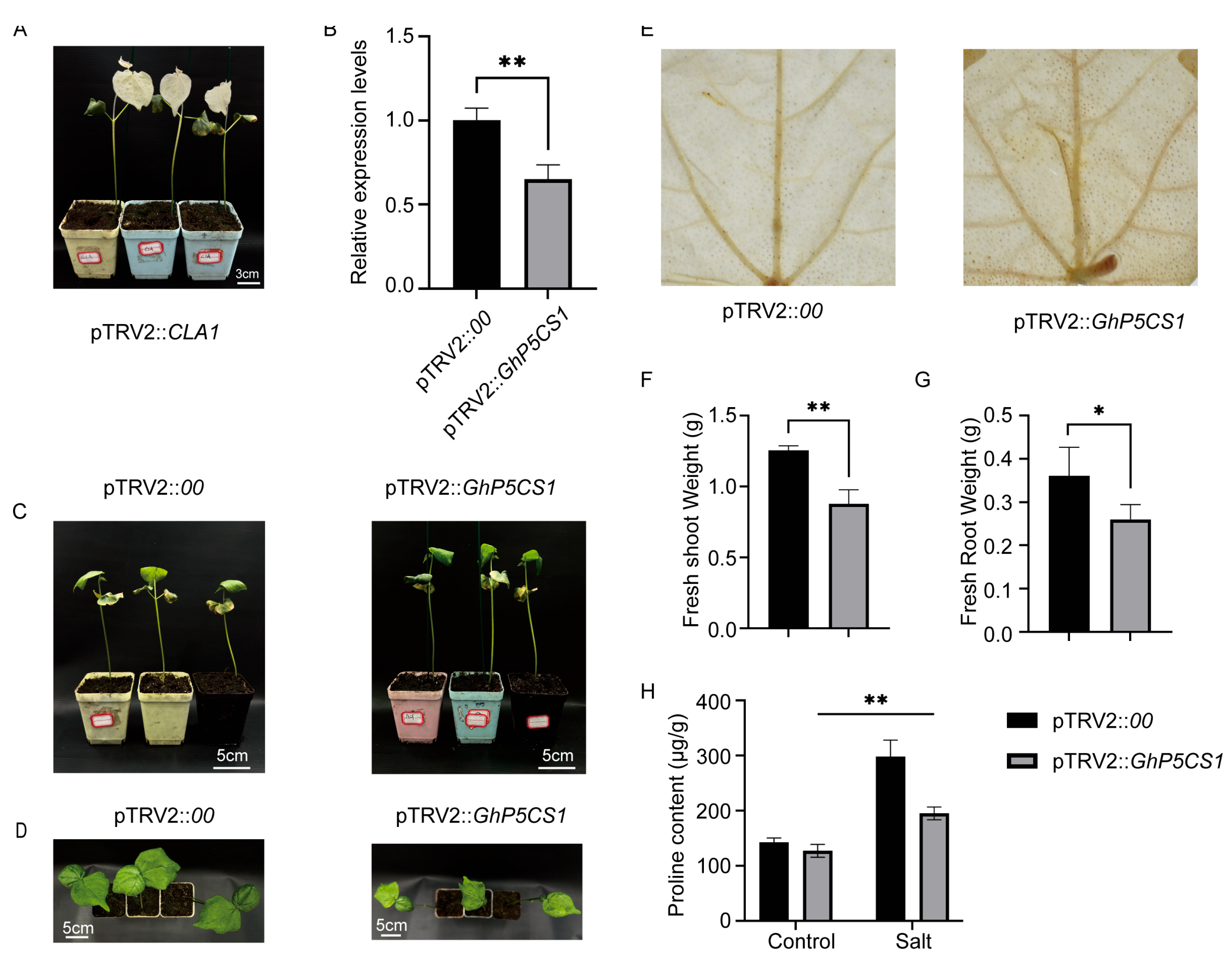

2.8. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing of GhP5CS1 Leads to Salt Sensitivity in Cotton

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of P5CS Gene Members in Different Species

4.2. Chromosome Localization Analysis of P5CS Genes in Cotton Species

4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis, Collinearity and Ka/Ks Ratios of P5CS Genes

4.4. Gene Structure and Protein Conserved Motif Analysis of P5CS Genes in Four Cotton Species

4.5. Subcellular Localization Prediction of P5CS Proteins

4.6. Cis-Acting Element Analysis of P5CS Gene Promoter Regions

4.7. Secondary Structure Prediction and Three-Dimensional Model Construction of GhP5CS Proteins

4.8. Plant Materials, Salt Treatment, RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

4.9. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

4.10. DAB Staining and Proline Content Determination

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levitt, M. Effect of proline residues on protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 1981, 145, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran Kumar Ghanti, S.; Sujata, K.G.; Vijay Kumar, B.M.; Nataraja Karba, N.; janardhan Reddy, K.; Srinath Rao, M.; Kavi Kishor, P.B. Heterologous expression of P5CS gene in chickpea enhances salt tolerance without affecting yield. Biol. Plantarum 2011, 55, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Ortega, C.O.; Ochoa-Alfaro, A.E.; Reyes-Agüero, J.A.; Aguado-Santacruz, G.A.; Jiménez-Bremont, J.F. Salt stress increases the expression of p5cs gene and induces proline accumulation in cactus pear. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2008, 46, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Su, J.; Chang, M.; Verma, D.P.S.; Fan, Y.-L.; Wu, R. Overexpression of a Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase gene and analysis of tolerance to water- and salt-stress in transgenic rice. Plant Sci. 1998, 139, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; An, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, D.; Tao, J. Functional Characterization of the Paeonia ostii P5CS Gene under Drought Stress. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urmi, T.A.; Islam, M.M.; Zumur, K.N.; Abedin, M.A.; Haque, M.M.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Murata, Y.; Hoque, M.A. Combined Effect of Salicylic Acid and Proline Mitigates Drought Stress in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) through the Modulation of Physiological Attributes and Antioxidant Enzymes. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksakal, O.; Tabay, D.; Esringu, A.; Icoglu Aksakal, F.; Esim, N. Effect of proline on biochemical and molecular mechanisms in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) exposed to UV-B radiation. Photochem Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.M.H.; Al Watban, A.A.; Al-Fughom, A.T. Effect of ultraviolet radiation on chlorophyll, carotenoid, protein and proline contents of some annual desert plants. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 18, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemadri Reddy, S.; Al-kalbani, H.; Al-Qalhati, S.; Al-Kahtani, A.A.; Al Hoqani, U.; Najmul Hejaz Azmi, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Saradhi Settaluri, V. Proline and other physiological changes as an indicator of abiotic stress caused by heavy metal contamination. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Patil, M.; Qamar, A.; Senthil-Kumar, M. ath-miR164c influences plant responses to the combined stress of drought and bacterial infection by regulating proline metabolism. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 172, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, C.J.; Pang, Y.-Y.; Mathews, S.D.; Turner, S.E.; Weisberg, A.J.; Lehmann, S.; Rentsch, D.; Anderson, J.C. Transporter-mediated depletion of extracellular proline directly contributes to plant pattern-triggered immunity against a bacterial pathogen. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchetto-Zolet, A.C.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Margis, R. The evolution of pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase in plants: a key enzyme in proline synthesis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2009, 281, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, N.; Hermans, C. Proline accumulation in plants: a review. Amino Acids 2008, 35, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, D.B.; Guzman, F.L.; Vetö, N.M.; Krause, F.A.; Kulcheski, F.R.; Coelho, A.P.D.; Duarte, G.L.; Margis, R.; Dillenburg, L.R.; Turchetto-Zolet, A.C. Characterization and expression analysis of P5CS (Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase) gene in two distinct populations of the Atlantic Forest native species Eugenia uniflora L. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, Y.; Yoshiba*, Y.; Sanada, Y.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Wada, K.; Shinozaki, K. Characterization of the gene for Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase and correlation between the expression of the gene and salt tolerance in Oryza sativa L. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 33, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Shriram, V.; Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Jawali, N.; Shitole, M.G. Enhanced proline accumulation and salt stress tolerance of transgenic indica rice by over-expressing P5CSF129A gene. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2010, 4, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Dang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. Isolation and characterization of a Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (NtP5CS) from Nitraria tangutorum Bobr. and functional comparison with its Arabidopsis homologue. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Huang, X.; Ding, L.; Wang, Z.; Tang, D.; Chen, B.; Ao, L.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z.; Mao, H. TaERF87 and TaAKS1 synergistically regulate TaP5CS1/TaP5CR1-mediated proline biosynthesis to enhance drought tolerance in wheat. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-B.; Nam, Y.-W. A novel Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase gene of Medicago truncatula plays a predominant role in stress-induced proline accumulation during symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Cen, H.-F.; Cui, X.; Tian, D.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-W. Overexpression of the Lolium perenne L. delta1-pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthase (LpP5CS) gene results in morphological alterations and salinity tolerance in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.). PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Ni, R.; Yang, S.; Pu, Y.; Qian, M.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y. Functional Characterization of the Stipa purpurea P5CS Gene under Drought Stress Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellamuthu, G.; Tarafdar, A.; Jasrotia, R.S.; Chaudhary, M.; Vishwakarma, H.; Padaria, J.C. Introgression of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (PgP5CS) confers enhanced resistance to abiotic stresses in transgenic tobacco. Transgenic Res. 2024, 33, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, S.; Monza, J. Identification of Δ1-pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS) genes involved in the synthesis of proline in Lotus japonicus. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017, 12, e1367464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strizhov, N.; Ábrahám, E.; Ökrész, L.; Blickling, S.; Zilberstein, A.; Schell, J.; Koncz, C.; Szabados, L. Differential expression of two P5CS genes controlling proline accumulation during salt-stress requires ABA and is regulated by ABA1, ABI1 and AXR2 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1997, 12, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Jia, G.-X. Three P5CS genes including a novel one from Lilium regale play distinct roles in osmotic, drought and salt stress tolerance. J. Plant Biol. 2016, 59, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem, A.; Esmaeili, N.; O’Connell, M.; Zhang, J. Progress and perspective on drought and salt stress tolerance in cotton. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 130, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Guo, L.; Fang, H.; Mehari, T.G.; Gu, H.; Wu, Y.; Jia, M.; Han, J.; Guo, Q.; Xu, Z.; et al. Transcriptomic profiling reveals salt-responsive long non-coding RNAs and their putative target genes for improving salt tolerance in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Ind. Crop. and Prod. 2024, 216, 118744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.R.; Lee, J.A. The role of proline accumulation in halophytes. Planta 1974, 120, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck, D.; Baumgarten, L.; Stift, M.; von Wirén, N.; Schönemann, L. Differential Contribution of P5CS Isoforms to Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arentson, B.W.; Sanyal, N.; Becker, D.F. Substrate channeling in proline metabolism. Front. biosci. 2012, 17, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, R.; Falasca, G.; Sabatini, S.; Altamura, M.M.; Costantino, P.; Trovato, M. The proline biosynthetic genes P5CS1 and P5CS2 play overlapping roles in Arabidopsis flower transition but not in embryo development. Physiol. Plantarum 2009, 137, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Székely, G.; Ábrahám, E.; Cséplő, Á.; Rigó, G.; Zsigmond, L.; Csiszár, J.; Ayaydin, F.; Strizhov, N.; Jásik, J.; Schmelzer, E.; et al. Duplicated P5CS genes of Arabidopsis play distinct roles in stress regulation and developmental control of proline biosynthesis. Plant J. 2008, 53, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comai, L. The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Sreedasyam, A.; Ando, A.; Song, Q.; De Santiago, L.M.; Hulse-Kemp, A.M.; Ding, M.; Ye, W.; Kirkbride, R.C.; Jenkins, J.; et al. Genomic diversifications of five Gossypium allopolyploid species and their impact on cotton improvement. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Fan, G.; Lu, C.; Xiao, G.; Zou, C.; Kohel, R.J.; Ma, Z.; Shang, H.; Ma, X.; Wu, J.; et al. Genome sequence of cultivated Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, B.; Zheng, H.-J.; Hu, Y.; Lu, G.; Yang, C.-Q.; Chen, J.-D.; Chen, J.-J.; Chen, D.-Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Gossypium barbadense genome sequence provides insight into the evolution of extra-long staple fiber and specialized metabolites. Sci. Rep-UK. 2015, 5, 14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Tang, Z.; Wang, M.; Gao, W.; Tu, L.; Jin, X.; Chen, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; et al. The genome sequence of Sea-Island cotton (Gossypium barbadense) provides insights into the allopolyploidization and development of superior spinnable fibres. Sci. Rep-UK. 2015, 5, 17662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Fang, L.; Guan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Saski, C.A.; Scheffler, B.E.; Stelly, D.M.; et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, J.P.C.; Zámocký, M.; Turchetto-Zolet, A.C. Unraveling the evolutionary origin of the P5CS gene: a story of gene fusion and horizontal transfer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Fan, G.; Wang, K.; Sun, F.; Yuan, Y.; Song, G.; Li, Q.; Ma, Z.; Lu, C.; Zou, C.; et al. Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Dong, Q.; Shao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, S.; Cheng, B.; Xiang, Y. Genome-wide survey and characterization of the WRKY gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holub, E.B. The arms race is ancient history in Arabidopsis, the wildflower. Nat. Rev. Gene. 2001, 2, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, N.; Song, W.; Yin, G.; Qin, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hu, Y. Soybean (Glycine max) expansin gene superfamily origins: segmental and tandem duplication events followed by divergent selection among subfamilies. Bmc Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.M.; Rehman, A.; Razzaq, A.; Parvaiz, A.; Mustafa, G.; Sharif, F.; Mo, H.; Youlu, Y.; Shakeel, A.; Ren, M. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of Erf gene family in cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Feng, X.; Huang, H.; Ni, K.; Han, M.; Lu, X.; et al. GhNFYA16 was functionally observed positively responding to salt stress by genome-wide identification of NFYA gene family in cotton. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Rui, C.; Han, M.; Malik, W.A.; Wang, Q.; Sun, L.; et al. Genome-wide identification of CK gene family suggests functional expression pattern against Cd2+ stress in Gossypium hirsutum L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A.; Clements, J.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Heger, A.; Hetherington, K.; Holm, L.; Mistry, J.; et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Copley, R.R.; Pils, B.; Pinkert, S.; Schultz, J.; Bork, P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D257–D260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; He, J.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; et al. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D222–D226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artimo, P.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Arnold, K.; Baratin, D.; Csardi, G.; de Castro, E.; Duvaud, S.; Flegel, V.; Fortier, A.; Gasteiger, E.; et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W597–W603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorrips, R.E. MapChart: Software for the Graphical Presentation of Linkage Maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Lercher, M.J.; Chen, W.; Hu, S. Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W236–W241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME Suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).