1. Introduction

Arterial reconfiguration denotes the structural and functional modification in the vessel wall in response to pathological conditions, injury, or aging process [

1,

2]. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), a major cell type in the middle layer of arterial vessel wall that alternate with rings of elastic lamellae, play a pivotal role in maintaining vascular stability and regulating vascular tone [

3,

4,

5]. VSMCs show significant plasticity, enabling the phenotypes to dynamically transition between highly proliferative synthetic and fully differentiated contractile phenotypes, predominantly preserved in mature cardiomyocytes [

6]. Thus, phenotypic switching is crucial for sustaining vascular homeostasis and the poor synthesis ability exhibited in VSMCs [

7]. However, in response to pathogenesis of various human cardiovascular diseases, the contractile phenotype is induced to transform into the dedifferentiated synthetic state [

8]. For example, in pathological condition of atherosclerosis, the alteration of contractile phenotype in VSMCs leads to narrow vessel diameter and vascular stiffness [

5,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Canonical subfamily members of transient receptor potential (TRPC) proteins are phospholipase C–linked receptor-operated non-specific Ca

2+-permeable non-selective cation in vertebrates [

15]. In cultured pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), TRPC6 expression is up-regulated after treatment with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) through the increase of store-operated Ca

2+ entry, involved in cell proliferation, resulting in phenotype switching from contractile to synthetic phenotype [

16,

17]. Activation of TRPC6 negatively regulates the promotion of vessel maturation after hindlimb ischemia, potentially contributing peripheral arterial disease [

18]. Thus, VSMCs remodeling is likely inferred by the expression pattern of TRPC6 and can alter their associated functions. As our group previously reported, reduced Ca

2+ entry by TRPC6 activation in ischemia stress-induced VSMCs could make it more switchable to contractile phenotype and maintain the interaction between TRPC6 and phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) [

19]. However, TRPC6 is a non-specific cation channel not only for Ca

2+, Na

+ and K

+, but also is a specific characteristic in Zn

2+ permeability channel, compared with TRPC3 and TRPC7 channels [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Zn²⁺ permeates from extracellular (approximately 19 nM) into the cells through transport and ion channels, most Zn²⁺ is believed to be tightly bound to intracellular molecules. While Zn

2+ binds with protein in a labile form, it remains about 0.2 mM mobile intracellular Zn²⁺ to play the second intracellular message function [

25,

26,

27]. Now, the pooled Zn²⁺ and mobile Zn²⁺ provide a different view of the physiological significance of Zn

2+ binding protein interactions. The critical functions of cellular zinc signaling and underscores potential molecular pathways linking zinc metabolism to disease progression [

28]. The importance of Zn

2+-permeable ion channels, especially in intracellular Zn

2+ dynamics and Zn

2+ mediated in physiological and pathophysiological processes, is now more widely appreciated [

29]. Treatment with 2,2ʹ-dithiodipyridine (DTDP) oxidizes Zn

2+-binding proteins and induces Zn

2+ release from the intracellular Zn

2+ pool [

30], utilized to evaluate Zn

2+ capability. Zn

2+ regulates the growth factor control of cell division, especially in cells regulated by insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) [

31] or nerve growth factor (NGF) [

32], which plays a positive function role in Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells proliferation and neuronal differentiation [

33]. Thus, in the mechanism investigation of the TRPC6 negatively mediated the differentiation of VSMCs, the specific Zn

2+ influx through TRPC6 channel could be a potential target in TRPC6-mediated phenotype regulation in pathologic VSMCs.

In this study, we use TRPC6 (WT) and TRPC6 zinc pore dead mutant (KYD)-expressing rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RAoSMCs) [

23] to investigate the role of TRPC6-mediated Zn

2+ influx in VSMC phenotypic switching and whether it has a beneficial effect on vascular remodeling. We evaluated that pharmacological activation of TRPC6-mediated Zn

2+ influx negatively regulates differentiation in TGFβ-stimulated TRPC6 (WT) or (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All protocols using mice were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Kyushu University and performed according to Institutional Guidelines Concerning the Care and Handling of Experimental Animals (approval no. A24-167-1, A24-252-1).

We obtained 129/Sv mice from the Comparative Medicine Branch, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). All mice were group-housed in individually ventilated cages (three or four animals per cage), with aspen wood chip bedding and kept under controlled environmental conditions (specific-pathogen-free area, 12 h light/dark cycle, room temperature 21–23 °C, and humidity 50–60%) with free access to standard laboratory food pellets (CLEA Rodent Diet CE-2, CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and water.

2.2. Vascular Injury Mice Model

Vascular injury model mice were induced with continuous administration of Angiotensin (Ang) II (PEPTIDE, Cat# 4001, Japan). A micro-osmotic pump (Alzet, Cat# 1002) filled with Ang II (2 mg/kg/day) with or without 2-[4-(2,3-dimethylphenyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-N- (2-ethoxyphenyl) acetamide (PPZ2, 2.5 mg/kg/day) [

34], a TRPC3/6/7 channel activator, was embedded intraperitoneally into 129/Sv mice (8-9 weeks old) for 14 consecutive days. Control mice were administered with the normal saline (NS).

2.3. Immunocytochemistry

TRPC6 (WT) and TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs were made by using retrovirus, and positive cells were selected with puromycin [

23]. RAoSMCs were cultured in culture medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, low glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 2 μg/ml Puromycin) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO

2, 95% air) [

23]. TRPC6 (WT) and TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs were seeded at 3 × 10

3 cells/200 μL on 4-well glass-bottom dishes. The cells were treated with 1‰ DMSO, 3 μM PPZ2, 10 ng/mL TGFβ and PPZ2 pretreated with TGFβ in culture medium adding 10 μM ZnCl

2 culture medium for 24 h, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (Fujifilm Wako, Cat# 045-29795, Japan) for 15 min. After washing with PBS for 10 min three times, cells were blocked with blocking-permeabilization solution containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 10% FBS in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were overnight incubated with the primary antibodies at 4 ℃: anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)(1:500 dilution; eBioscience, Cat# 14-9760-82, US), anti-smooth muscle 22 α (SM22α)(1:500 dilution; Abcam, Cat# 14106, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and anti-TRPC6 (extracellular) (1:300 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# ACC-120, US). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A11029 or Cat# A11034, US) secondary antibodies were applied for 2 h at room temperature in blocking-permeabilization solution. The nuclei were stained with 4’-6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:10000 dilution; DOJINDO, Cat# 340-7971, Japan). The fluorescence images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800; Keyence, Japan) or a confocal microscope (LSM 900; ZEISS, Germany) and the mean fluorescence intensity/pixel of each cell was analyzed with ImageJ2 (Version: 2.14.0/1.54f) software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was assessed by Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 (DOJINDO, Cat# 347-07621, Kumamoto, Japan). TRPC6 (WT) and TRPC6 (KYD-expressing RAoSMCs were seeded at 5 × 103 cells in 100 μL each well on 96-well-plate. One day after plating, cells were treated with 1‰ DMSO, 3 μM PPZ2, 10 ng/mL TGFβ and PPZ2 pretreated with TGFβ in culture medium adding 10 μM ZnCl2 for 24 h to determine cell proliferation. The value of wells with 1‰ DMSO was normalized as a control.

2.5. RAoSMCs Transfection

RAoSMCs were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, low glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO

2, 95% air). A fraction of RAoSMCs were plated in 35-mm culture dishes and transfected with plasmid DNAs (TRPC6 (WT) and TRPC6 (KYD) mutant) [

35] using X-tremeGENE9 (Roche). The cells were treated with 1‰ DMSO, 3 μM PPZ2, 10 ng/mL TGFβ and PPZ2 pretreated with TGFβ in culture medium adding 10 μM ZnCl

2 for 24 h, then reseeded cells onto glass coverslips (3 × 5 mm

2) in 35-mm culture dishes for patch-clamp.

2.6. Zn2+ Imaging

For measurement of Zn

2+ influx, TRPC6 (WT) and TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs were reseeded onto coverslips (3 × 5 mm

2) in 6-well-plate with 2 mL culture medium. The cells were treated with 1‰ DMSO, 3 μM PPZ2, 10 ng/mL TGFβ and PPZ2 pretreated with TGFβ in medium adding 10 μM ZnCl

2 for 24 h, then washed with 1× HBSS (10× HBSS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 14065-056) and loaded with FluoZin-3 (2 μM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# F24195) for 30 min at 37℃ [

23]. After loading, the dye solution was replaced with 1× HBSS. 50 μM DTDP (Sigma, Cat# 2127-03-9, Germany) was applied 2 min after starting measurement, then N,N,Nʹ,Nʹ-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN, 50 μM; Zn

2+ chelator)(DOJINDO, Cat# 340-05411, Japan) was applied 5 min after adding DTDP. Fluorescence images were recorded every 10 seconds and analyzed using a video image analysis system (Aquacosmos 2.6, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan).

2.7. Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Techniques

The conventional whole-cell patch-clamp technique was used to record resting membrane potential and ion currents in the voltage-clamp models at room temperature with an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Patch electrodes with a resistance of 3–4 MΩ were made from G-1.5-mm borosilicate glass capillaries (Sutter Instrument). In this study, TRPC6 current [

36] was measured by the whole-cell patch-clamp technique on TRPC6 WT and KYD mutant overexpressing RAoSMCs which were treated with 1 μM DMSO, 10 ng/mL TGFβ with or without 3 μM PPZ2 for 24 h in 10 μM ZnCl

2 supplied culture medium and pre-reseeded on glass coverslips. Cells were allowed to settle in the perfusion chamber in the external solution. TRPC6 was recorded in K

+-free bathing solution including (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5.4 CsCl, 1 CaCl

2, 1 MgCl

2, 0.33 NaH

2PO

4, 5 HEPES and 5.5 glucose (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 120 CsOH, 120 aspartate, 20 CsCl, 2 MgCl

2, 5 EGTA, 1.5 CaCl

2, 10 HEPES and 10 glucose (pH 7.2, adjusted with CsOH). Voltage ramps (−100 to +100 mV) of 250 ms were recorded every 2 s from a holding potential of −60 mV.

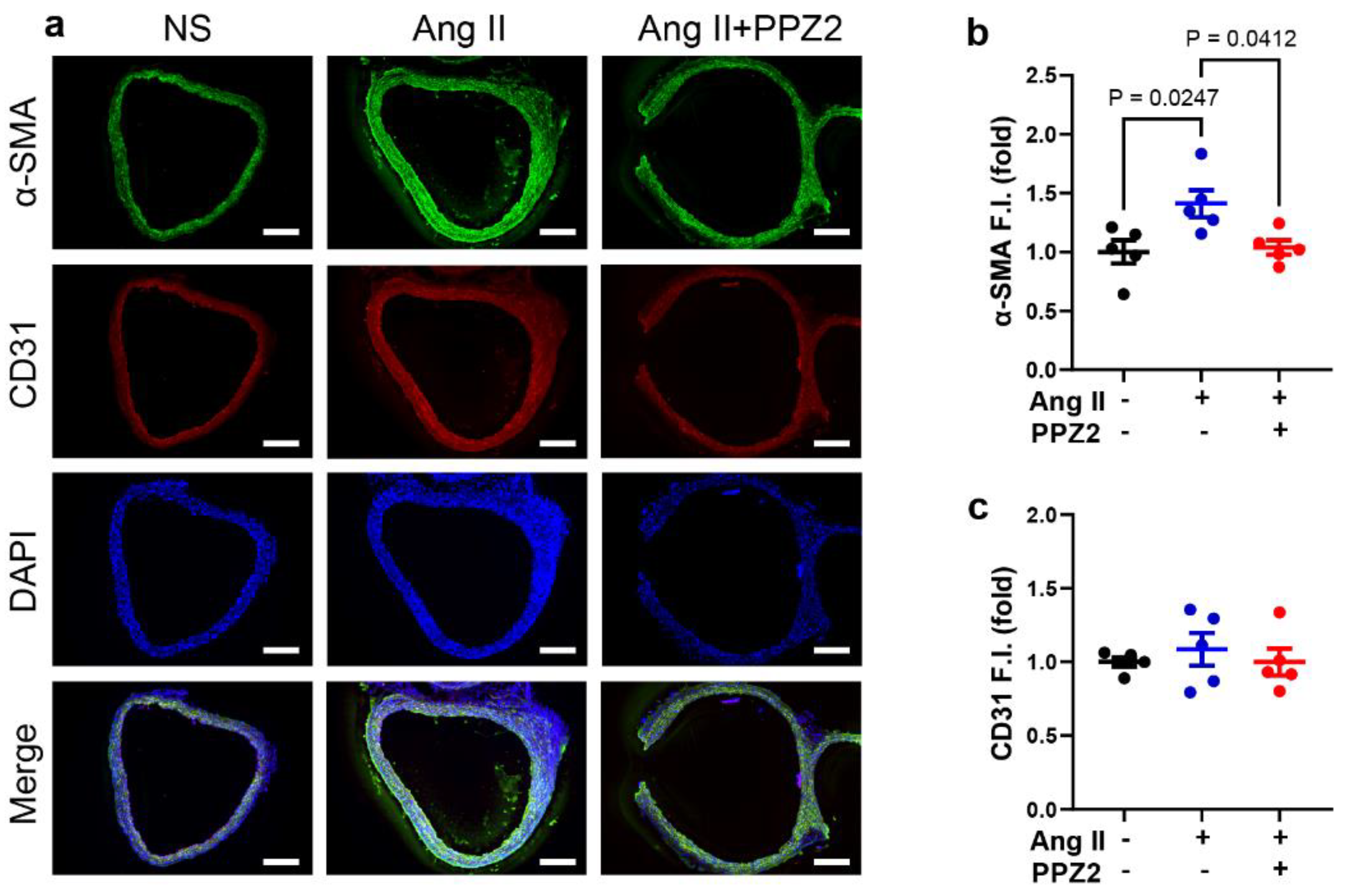

2.8. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Mouse Aortas

The aortas removed from mice were embedded in an optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura finetech) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were sliced at 10 μm slices by Leica CM1100 (Leica Biosystems). Sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, then washed with PBS for three times. Blocking of the sections was performed with blocking-permeabilization solution containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 10% FBS in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were stained overnight at 4℃ with primary anti-mouse α-SMA (1:500 dilution, eBioscience, Cat# 14-9760-82, CA, US) and anti-mouse CD31 (1:200 dilution, BioLegend, Cat# 102401) antibodies, incubated 2 h with secondary Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rat IgG (1:500 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A11077) at room temperature in blocking-permeabilization solution. The specimens were observed with a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800; Keyence, Osaka, Japan). For the analysis of α-SMA and CD31 expression in aortas, fluorescence signal intensity within the region of interest (ROI) being made based on α-SMA fluorescence images was quantified, which was further normalized and represented as a fold increase from before chronic Ang Ⅱ administration. ImageJ2 (Version: 2.14.0/1.54f) software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for all the image analysis.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were carried out by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, LaJolla, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Activated TRPC6 Channel Prevents TGFβ-Induced Differentiation on TRPC6 (WT)-Expressing RAoSMCs

TGFβ is a key cytokine implicated in vascular remodeling, has been shown to drive VSMCs toward differentiation state [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Ca

2+ entry through up-regulated TRPC6 expression also affects VSMC phenotypic switching in pathological conditions [

18,

19]. To determine if pharmacological activation of TRPC6 is involved in the maintenance of contractile phenotype. Firstly, we found that activation of TRPC6 by PPZ2 markedly decreased TGFβ-induced contractile phenotype intensity fluorescence and quantification level of VSMCs early marker, including α-SMA (

Figure 1a,b) and SM22α (

Figure 1c,d). Moreover, we confirmed that TRPC6 (WT)-expressing level was not affected by pharmacological treatment with PPZ2 with or without TGFβ in RAoSMCs (

Figure 1e,f). These results demonstrate that activated TRPC6 regulates phenotypic switching in TRPC6 (WT)-expressing RAoSMCs.

3.2. Involvement of Depriving of Zn2+ Influx by TRPC6 in Phenotypic Switching of TRPC6 (KYD)-Expressing RAoSMCs

To investigate whether Zn

2+ influx through activated-TRPC6 prevents VSMCs differentiation, we utilized zinc-pore deficiency mutant plasmid constructed TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs, as previously reported [

23]. The contractile markers of α-SMA (

Figure 2a,b) and SM22α (

Figure 2c,d) intensity fluorescence and quantification level were analyzed in TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs. However, the contractile marker intensity level under treatment of PPZ2 was consistent with the TGFβ-induced contractile state. We found that TRPC6 (WT)-expressing intensity level was also not affected by pharmacological treatment with PPZ2 with or without TGFβ in TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs, either (

Figure 2e,f). Simultaneously, CCK-8 assay results emphasized that all pharmacological treatment did not impact cell viability in TRPC6 (WT)- and TRPC6-(KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs (

Figure 2g,h). These data indicate that suppressing Zn

2+ influx elicited by TRPC6 maintained the contractile states of TRPC6 (WT)-expressing RAoSMCs.

3.3. Pharmacological Activated TRPC6 Reverse Intracellular Pooled Zn2+ Amount in TGFβ-Induced Contractile State

Next, we investigated the relationship between Zn

2+ pool capability and phenotypic switching in VSMCs. Our results showed the release of the pooled Zn

2+ amount by DTDP was reduced in TGFβ-induced contractile states TRPC6 (WT)-expressing RAoSMCs, whereas this reduction was reversed by pretreatment with PPZ2 group (

Figure 3a,b). Interestingly, even though under pharmacologically activated TRPC6 in TRPC6 (KYD)-expressing RAoSMCs, Zn

2+ deficiency maintains TGFβ-induced differentiation (

Figure 3c,d). These data suggest that the pooled Zn

2+ amount, stored by Zn

2+ influx from extracellular, plays a crucial role in regulating VSMCs phenotype switching.

3.4. Effect of Electrophysiological Property Changes of TRPC6 in RAoSMCs Differentiation

Our data showed that the property of TRPC6 for Na

+ and Ca

2+ permeability was not changed under PPZ2 activated TRPC6 in 10 μM ZnCl

2 culture medium after 24 h treatment in TRPC6 (WT)-expression RAoSMCs (

Figure 4a,b). Otherwise, unchanged electrophysiological property was evaluated in Zn

2+ pore deficiency TRPC6 (KYD) RAoSSMCs during 24 h with pharmacological treatment in 10 μM ZnCl

2 culture medium (

Figure 4c,d). It demonstrated that the character change of Zn

2+ pore deficiency TRPC6 affects the VSMCs differentiation through the pooled Zn

2+ amount.

3.5. PPZ2 Attenuates Ang II-Induced VSMCs Switching to a Contractile Phenotype in Mice Aortas

Ang II regulates the expression or function of TGFβ receptors on VSMCs to modulate cell growth [

42]. We finally examined whether PPZ2-activated TRPC6 regulates phenotypic switching of VSMCs in chronic Ang II treated mice aorta. We performed double immunofluorescence staining with antibodies to α-SMA and CD31 and found that α-SMA fluorescence was upregulated in aortas in the chronic Ang II treated group, while this upregulation was reversed upon PPZ2 treatment (

Figure 5). Therefore, TRPC6 channel activity makes VSMCs more switchable back to the synthetic phenotype.

4. Discussion

Our study uncovers the pivotal role of TRPC6-mediated Zn²⁺ influx in regulating VSMCs phenotypic switching and its broader implications in vascular remodeling. We observed Zn²⁺ influx through the activated-TRPC6 channel by PPZ2, which negatively regulated TGFβ-induced differentiation, transforming VSMCs into the synthetic phenotype and accelerating VSMCs to process in pathological conditions (such as hypertension or arteriosclerosis). These findings provide new insights into vascular plasticity and remodeling mechanisms, with significant implications for cardiovascular disease management.

The specific Zn²⁺ permeability of TRPC6, as compared to other TRPC channels, adds a new dimension to its regulatory role in cellular homeostasis. Previous studies primarily focused on TRPC6-mediated Ca²⁺ influx in vascular pathological conditions. TRPC6 deficiency impairs the maintenance of the contractile phenotype in atrial VSMCs, as evidenced by reduced expression of contractile biomarkers and enhanced VSMCs proliferation and migration, as well as exacerbated neointimal hyperplasia and luminal stenosis in the common carotid arteries (CCA) of TRPC6

(-/-) mice [

32]. In addition, our previous research, TRPC6 channels mediate Ca²⁺ influx, playing a pivotal role in VSMCs. PTEN, a lipid phosphatase, plays a role in repressing downstream PI3K/Akt pathways activated by interaction with phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-trisphosphate (PIP3) phosphatase. Our group’s previous research showed that activation of TRPC6 channels by diacylglycerol (DAG) induces Ca²⁺ entry, promoting phenotypic modulation in the synthetic states of VSMCs, which is associated with membrane depolarization coupling the interaction with PTEN [

19]. However, mobile Zn

2+ inhibited the negative regulator PTEN to stimulate the PI3K/Akt pathway of interleukin (IL)-2 signaling in T-cells, human airway epithelium and neurodegeneration. Additionally, Zn²⁺ deficiency reduces the proliferation of transplanted tumors in host animals [

43] and decreases proliferation in rat aorta-origin VSMCs (A7r5 VSMCs) and aorta VSMCs under non-calcifying and calcifying condition [

44]. It is the primary contributor to the forming smooth muscle cell hyperplasia of atherosclerotic plaques.

Our findings highlight Zn²⁺ as a critical second messenger in TRPC6-mediated regulation of VSMCs. However, the causal relationship between Zn2+ dynamics and vascular plasticity has been obscure. Therefore, beyond Ca2+ signaling, we utilized DPDT to release the intracellular zinc pool to evaluate the interaction of Zn2+ and phenotype regulation in VSMCs and patch clamp to investigate the characters of TRPC6 changes after phenotypic plasticity. Our data suggested that pharmacologic activity of TRPC6 with PPZ2 alleviated TGFβ-induced differentiation and increased intracellular Zn2+ amount in TRPC6 (WT) stable RAoSMCs but not in TRPC6 (KYD) Stable RAoSMCs. These differences indicated that TRPC6-mediated Zn2+ influx maintained the synthetic phenotype of VSMCs.

Vascular injury, characterized by endothelial dysfunction, structural remodeling, inflammation and fibrosis, significantly contributes to the progression of cardiovascular diseases. Cellular processes underlying vascular injury include imbalanced VSMC plasticity, which results in maladaptive phenotypic switching [

6]. Ang II signaling pathways become activated with age and contribute to developing arteriosclerosis and vascular senescence. Ang II is one of the numerous factors implicated in vascular injury, it can be converted into smaller, functionally active peptides and play a role in regulating vascular tone and structure [

45]. To analyze the possibility that Zn

2+ influx by TRPC6-mediated VSMCs phenotype regulation plays a role in pathologic VSMCs, we utilized Ang II treatment as an in vivo disease model, pump embedded with or without PPZ2. We showed that activation of TRPC6 channel by PPZ2 attenuates Ang II-induced aortic fibrosis in mice. Further analyses of TRPC6 protein function are required to determine the pathological significance of TRPC6 in VSMC plasticity.

5. Conclusions

Our findings highlight the pivotal role of TRPC6-mediated Zn²⁺ influx in modulating VSMC phenotypic plasticity and vascular remodeling, providing novel insights into its potential as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. These results not only expand the understanding of Zn²⁺ signaling in vascular biology but also underscore the clinical significance of TRPC6 in regulating vascular function. Future investigations should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying TRPC6-mediated Zn²⁺ signaling, exploring its role across various vascular cell types to fully realize its therapeutic potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.; Methodology, C.S., X.M. and T.I.; Validation, M.N.; Formal Analysis, C.S., X.M.; Investigation, C.S., X.M., T.I., A.N., and Y.K.; Resources, R.N. and Y.M.; Data Curation, C.S., X.M., T.I., A.N., and Y.K; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, C.S. and X.M.; Writing-Review & Editing, M.N., X.M., T.I. and C.S.; Visualization, T.I.; Supervision, M.N.; Project Administration, M.N.; Funding Acquisition, T.I. and M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JST CREST Grant Number JPMJCR2024 (20348438 to M.N. and A.N.), JSPS KAKENHI (24K23268 to T.I. and 22H02772 to M.N.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas(A) “Sulfur biology” (21H05269 and 21H05258 to M.N.) and International Leading Research (23K20040 to M.N.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, the Naito Foundation (to M.N.) and Smoking Research Foundation (to M.N.).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brown, I.A.M.; Diederich, L.; Good, M.E.; DeLalio, L.J.; Murphy, S.A.; Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Hall, J.L.; Le, T.H.; Isakson, B.E. Vascular Smooth Muscle Remodeling in Conductive and Resistance Arteries in Hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018, 38, 1969–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roldán-Montero, R.; Pérez-Sáez, J.M.; Cerro-Pardo, I.; Oller, J.; Martinez-Lopez, D.; Nuñez, E.; Maller, S.M.; Gutierrez-Muñoz, C.; Mendez-Barbero, N.; Escola-Gil, J.C.; et al. Galectin-1 prevents pathological vascular remodeling in atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabm7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, W.E.; Miletich, D.J.; Albrecht, R.F.; Anderson, S. Regional cerebral blood flow measurement in rats with radioactive microspheres. Life Sci 1983, 33, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, R.; Dave, J.M.; Chandran, R.R.; Misra, A.; Sheikh, A.Q.; Greif, D.M. Vascular Cells in Blood Vessel Wall Development and Disease. Adv Pharmacol 2017, 78, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, G.K.; Kumar, M.S.; Wamhoff, B.R. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev 2004, 84, 767–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frismantiene, A.; Philippova, M.; Erne, P.; Resink, T.J. Smooth muscle cell-driven vascular diseases and molecular mechanisms of VSMC plasticity. Cell Signal 2018, 52, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Hu, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, W.D.; Song, Y.F.; Quan, X.H.; Guo, X.; Wang, C.X. Glutamine switches vascular smooth muscle cells to synthetic phenotype through inhibiting miR-143 expression and upregulating THY1 expression. Life Sci 2021, 277, 119365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Y.; Chen, A.Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.F.; Kong, X.Q.; Zhang, J.J. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Phenotypic Switching in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.R.; Sinha, S.; Owens, G.K. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2016, 118, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Dusenbery, B.N.; Wu, C.; Hata, A. Micromanaging vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic modulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011, 31, 2370–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, J.H.; Fuster, V.; Badimon, L.; Badimon, J.; Taubman, M.B.; Chesebro, J.H. Syndromes of accelerated atherosclerosis: role of vascular injury and smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990, 15, 1667–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocher, O.; Gabbiani, G. Cytoskeletal features of normal and atheromatous human arterial smooth muscle cells. Hum Pathol 1986, 17, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of the acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2001, 104, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, J.M.; Cserjesi, P.; Ligon, K.L.; Periasamy, M.; Olson, E.N. Smooth muscle myosin heavy chain exclusively marks the smooth muscle lineage during mouse embryogenesis. Circ Res 1994, 75, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, T.; Obukhov, A.G.; Schaefer, M.; Harteneck, C.; Gudermann, T.; Schultz, G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 1999, 397, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.A.; Wan, J.; Song, S.; Smith, K.A.; Gu, Y.; Tauseef, M.; Tang, H.; Makino, A.; Mehta, D.; Yuan, J.X. Upregulated expression of STIM2, TRPC6, and Orai2 contributes to the transition of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells from a contractile to proliferative phenotype. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2015, 308, C581–C593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golovina, V.A.; Platoshyn, O.; Bailey, C.L.; Wang, J.; Limsuwan, A.; Sweeney, M.; Rubin, L.J.; Yuan, J.X. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca(2+) entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001, 280, H746–H755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numaga-Tomita, T.; Shimauchi, T.; Kato, Y.; Nishiyama, K.; Nishimura, A.; Sakata, K.; Inada, H.; Kita, S.; Iwamoto, T.; Nabekura, J.; et al. Inhibition of transient receptor potential cation channel 6 promotes capillary arterialization during post-ischaemic blood flow recovery. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numaga-Tomita, T.; Shimauchi, T.; Oda, S.; Tanaka, T.; Nishiyama, K.; Nishimura, A.; Birnbaumer, L.; Mori, Y.; Nishida, M. TRPC6 regulates phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells through plasma membrane potential-dependent coupling with PTEN. Faseb j 2019, 33, 9785–9796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallet, M.; Jarvis, L.; Harel, A.; Luche, S.; Degot, S.; Chapuis, V.; Boulay, G.; Rabilloud, T.; Bouron, A. Functional consequences of the over-expression of TRPC6 channels in HEK cells: impact on the homeostasis of zinc. Metallomics 2014, 6, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibon, J.; Tu, P.; Bohic, S.; Richaud, P.; Arnaud, J.; Zhu, M.; Boulay, G.; Bouron, A. The over-expression of TRPC6 channels in HEK-293 cells favours the intracellular accumulation of zinc. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1808, 2807–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasna, J.; Abi Nahed, R.; Sergent, F.; Alfaidy, N.; Bouron, A. The Deletion of TRPC6 Channels Perturbs Iron and Zinc Homeostasis and Pregnancy Outcome in Mice. Cell Physiol Biochem 2019, 52, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, S.; Nishiyama, K.; Furumoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Tang, X.; Kato, Y.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Kaneko, T.; Mangmool, S.; et al. Myocardial TRPC6-mediated Zn(2+) influx induces beneficial positive inotropy through β-adrenoceptors. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trebak, M.; Vazquez, G.; Bird, G.S.; Putney, J.W., Jr. The TRPC3/6/7 subfamily of cation channels. Cell Calcium 2003, 33, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreini, C.; Banci, L.; Bertini, I.; Rosato, A. Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome. J Proteome Res 2006, 5, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W. Zinc in Cellular Regulation: The Nature and Significance of "Zinc Signals". Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, S.; Sakata-Sogawa, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Suzuki, T.; Kabu, K.; Sato, E.; Kurosaki, T.; Yamashita, S.; Tokunaga, M.; Nishida, K.; et al. Zinc is a novel intracellular second messenger. J Cell Biol 2007, 177, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, Y.; Ye, X.; Zhang, N.; Pan, L.; Wang, B. TRP (transient receptor potential) ion channel family: structures, biological functions and therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; O'Bryant, Z.; Xiong, Z.G. Zinc-permeable ion channels: effects on intracellular zinc dynamics and potential physiological/pathophysiological significance. Curr Med Chem 2015, 22, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizenman, E.; Stout, A.K.; Hartnett, K.A.; Dineley, K.E.; McLaughlin, B.; Reynolds, I.J. Induction of neuronal apoptosis by thiol oxidation: putative role of intracellular zinc release. J Neurochem 2000, 75, 1878–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstead, H.H.; Frederickson, C.J.; Penland, J.G. History of zinc as related to brain function. J Nutr 2000, 130, 496s–502s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.H.; Putta, P.; Driscoll, E.C.; Chaudhuri, P.; Birnbaumer, L.; Rosenbaum, M.A.; Graham, L.M. Canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel deficiency promotes smooth muscle cells dedifferentiation and increased proliferation after arterial injury. JVS Vasc Sci 2020, 1, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.O.; Banerjee, A.; Clarke, S.; de Belder, M.; Patwala, A.; Goodwin, A.T.; Kwok, C.S.; Rashid, M.; Gale, C.P.; Curzen, N.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cardiac procedure activity in England and associated 30-day mortality. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2021, 7, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawamura, S.; Hatano, M.; Takada, Y.; Hino, K.; Kawamura, T.; Tanikawa, J.; Nakagawa, H.; Hase, H.; Nakao, A.; Hirano, M.; et al. Screening of Transient Receptor Potential Canonical Channel Activators Identifies Novel Neurotrophic Piperazine Compounds. Mol Pharmacol 2016, 89, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimauchi, T.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Kato, Y.; Morimoto, H.; Sakata, K.; Matsukane, R.; Nishimura, A.; Nishiyama, K.; Shibuta, A.; Horiuchi, Y.; et al. A TRPC3/6 Channel Inhibitor Promotes Arteriogenesis after Hind-Limb Ischemia. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, A.; Kitagawa, H.; Omatsu-Kanbe, M.; Matsuura, H.; Nosaka, S. Ca2+ paradox injury mediated through TRPC channels in mouse ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol 2010, 161, 1734–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, K.K.; Rohovsky, S.A.; D'Amore, P.A. PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol 1998, 141, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson-Percival, A.; Li, Z.J.; Lakhiani, D.D.; He, B.; Wang, X.; Hamzah, J.; Ganss, R. Intratumoral LIGHT Restores Pericyte Contractile Properties and Vessel Integrity. Cell Rep 2015, 13, 2687–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Luo, Z.; Huang, W.; Lu, Q.; Wilcox, C.S.; Jose, P.A.; Chen, S. Response gene to complement 32, a novel regulator for transforming growth factor-beta-induced smooth muscle differentiation of neural crest cells. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 10133–10137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainland, D. Statistical ward round. 16. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1969, 10, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Xie, W.B.; Chen, S.Y. Cell division cycle 7 is a novel regulator of transforming growth factor-β-induced smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 6860–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, N.; Hu, W.Y.; Kubo, A.; Kishioka, H.; Satoh, C.; Soma, M.; Izumi, Y.; Kanmatsuse, K. Angiotensin II upregulates transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor on rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Hypertens 2000, 13, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWys, W.; Pories, W. Inhibition of a spectrum of animal tumors by dietary zinc deficiency. J Natl Cancer Inst 1972, 48, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alcantara, E.H.; Shin, M.Y.; Feldmann, J.; Nixon, G.F.; Beattie, J.H.; Kwun, I.S. Long-term zinc deprivation accelerates rat vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation involving the down-regulation of JNK1/2 expression in MAPK signaling. Atherosclerosis 2013, 228, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montezano, A.C.; Nguyen Dinh Cat, A.; Rios, F.J.; Touyz, R.M. Angiotensin II and vascular injury. Curr Hypertens Rep 2014, 16, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).