Introduction

Mixtures of nano-hydroxyapatite with collagen fibers are used to design materials for bone regeneration procedures [

1]. The biocompatibilities of collagen fiber and nano-hydroxyapatite promote ideal conditions to create an efficient biomaterial for bone formation process [

2].

The physicochemical characteristics of nano-hydroxyapatite (n-HA) prove to be extremely efficient in the bone remodeling process. When compared to micro-hydroxyapatite, the percentage of newly formed matrix and blood vessel proliferation are statistically higher for the n-HA groups, [

3].

Type 1 collagen from bovine or other sources, such as porcine pericardium, is widely used as a hemostatic barrier or protective barrier in cases of guided bone regeneration. However, its association with materials that serve as pillar for bone remodeling surgery, such as hydroxyapatite and nano-hydroxyapatite, is being widely developed because the combination of both promotes material stability at the time of surgery and post-surgery [

4].

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is an excellent tool for determining the collagen bundles present in materials used in guided bone regeneration. Collagen fibrils are very characteristic and the more organized they are, the more organic the sample will be and the better its biocompatibility [

5].

Characterization methods, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), are necessary to develop new biomaterials. These methods provide high-resolution images to identify the biomaterials in the samples [

6].

Semiquantitative chemical analysis using a microprobe coupled to the SEM helps determine the semiquantitative percentages of the chemical elements present in the sample analysis. This technique is suited to identify the possible contaminants from manufacturing procedures that potentially can spoil the material's performance [

7].

X-ray diffraction can identify the crystalline phases and chemical elements present in the material. The Rietveld technique quantifies each phase and calculates the chemical percentages of the material [

8].

Currently, in the science of biomaterials, the diversity of technical analyses to make it easier and improve the development of biomaterials accelerates the emergence of new potential products. Combining several materials to form a single product becomes a very interesting strategy to improve the final product in several areas, including bone formation [

9].

The objective of the present work was to characterize the morphology, identify the crystalline phases, and determine the chemical composition of a composite obtained by combining of nano-hydroxyapatite/β-Tricalcium phosphate and type 1 collagen for use as a biomaterial.

Materials and Methods

The analyzed material, named Blue Bone Block®, was synthetized by an inorganic reaction of two different salts, calcium nitrate and dibasic ammonium phosphate in a very controlled condition keeping the perfect mass balance and the necessary stoichiometry of the reaction, 10:6 Calcium/Phosphorus. The alloplastic biomaterial mixture was synthesized and named Blue Bone® at the facilities of Regener Biomaterials Co (Curitiba, Brazil). The biomaterial had nanometric particles of hydroxyapatite and ß-TCP morphologies.

The collagen type 1 were prepared at Regener® Biomaterials facilities by performing 3 simple steps: cleaning the raw material using two chemical baths, sodium hydroxide and acetone for fat removal; extracting the type 1 collagen using acetic acid from the cleaned bovine tendons; and purifying the extracted material by lyophilization process. The collagen type 1 had an expected reabsorption time of up to 30 days.

The chemical composition of the composite was determined using semi-quantitative chemical analysis with a microprobe coupled to the SEM and TEM.

Scanning Electron Microscopy and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Gold-coated collagen type 1 surfaces were analyzed using a Field Emission GUN Quanta 250 FEG (FEI Company, Oregon, USA). A 5000 magnification was used to investigate the homogeneity, a 15,000 magnification to observe cell clusters, and a 20,000 magnification to identify specific cell types. For the SEM analysis, the fixation procedure started with osmium tetroxide and potassium ferrocyanide (1.0 wt%, 0.8 wt%, respectively) with a cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) incubation for 1 h in the dark, followed by three sodium cacodylate buffer rinses in distilled water (0.2 M, pH 7.4) for 1 h. This was followed by sequential ethanol grades (25–100 vol%) rinse for specimen dehydration. The slices were immersed in hexamethyl disilazane for 10 min before placing in an evaporation chamber for drying. Specimen mount on aluminum stubs was achieved using colloidal silver adhesive (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Peabody, MA, USA). The specimens were coated with gold film by sputtering (Cool Sputter Coater—SCD 005, Bal-Tec, Berlin, Germany).

The results of SEM analysis were complemented with roughness measurements using a Zygo NewView 7100 optical roughness meter (Zygo Corporation, Connecticut, United States). The implants' roughness parameters Ra, Rsk, Rms, Rku, PV, Rpk, Rk, and R3z were obtained. The analyzed regions presented homogeneous roughness with similar values for all regions.

Thin collagenous type 1 sections were analyzed using a JEOL JEM-1011 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), operatin at 60 kV. Digital micrographs were captured using an ORIUS CCD digital camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) at 8000×, 10,000× and 25,000× magnification.

The preparation of the samples for TEM analysis was the following: fixation in 2.5 wt% glutaraldehyde diluted in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer solution (overnight). Washing in 3 baths in cacodylate buffer solution (0.1 M), for 15 min each bath. Dehydration in 30 vol% acetone bath (15 min), 50 vol% acetone, 70 vol% acetone (15 min), 90 vol% acetone (15 min), 100 vol% acetone (15 min), and 100 vol% acetone (15 min) Infiltration in acetone + epon mixture (2:1) for 2 h; acetone + epon (1:1) for 2 h; acetone + epon mixture (1:2) for 2 h, infiltration in pure Epon (overnight) Inclusion in Epon and polymerization between 48 and 72 h at 60 °C. Plate cuts with a thickness of 1 micrometer and staining with toluidine blue. Cutting with ultramicrotome to obtain 70 nm slides, which were collected on 300 mesh copper grids. Contrasting of the slides with uranyl acetate (for 20–30 min); and TEM observation.

The X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

The biomaterial was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), porosimetry, and pycnometer tests. The morphology of the samples was characterized using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) Field Emission Gun (Quanta FEG 250; Hillsboro, Oregon 97124 - USA).

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed using a Panalytical (Almelo, Netherlands) Empyrean diffractometer, with Cu-Kα radiation, 2θ range of 20–80°, a step width of 0.02°, and an exposure time of 5 s.

The diffraction peaks were identified by comparing them with standard ICDD (International Centre for Diffraction Data) diffraction files and COD-Jan2012 (Crystallography Open Database) PDF2-2004 databases. The Rietveld method was employed to quantify the phases and analyze the crystal structures.

Rietveld analysis of XRD data was used to identify and quantify the percentages of the phases. The X-ray diffractograms were recorded on a Siemens diffractor (Bruker AXS; Durham—UK), model D-5000 (θ-θ), equipped with a graphite curved monochromator, secondary beam and Cu tube. The quantitative analysis of the phases was determined by the mathematical refinement method proposed by Rietveld.

The Rietveld Method involves adjusting the theoretical diffraction peaks calculated from crystallographic information to the experimentally measured diffraction pattern. The criterion for this adjustment is to minimize the sum of the squares of the differences.

Results

The SEM photomicrographs showed different gray shades material bordered by a light clear region. Different regions were aleatory selected for higher magnification and semiquantitative chemical analysis. (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3)

The collagen fibrils can be identified as bundles of different thickness and diverse directions (

Figure 2a–f)

The SEM analyzed images showed sheets and plates of collagen in diverse plans of orientations and a highly angulous and porous surfaces of the calcium phosphate granules (

Figure 3a,b)

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy showed the type 1 collagen fibers, which are organically arranged in straight bundles. It was also possible to see that there was no external agent in the type 1 collagen, indicating the purity of the sample. (

Figure 4A,B)

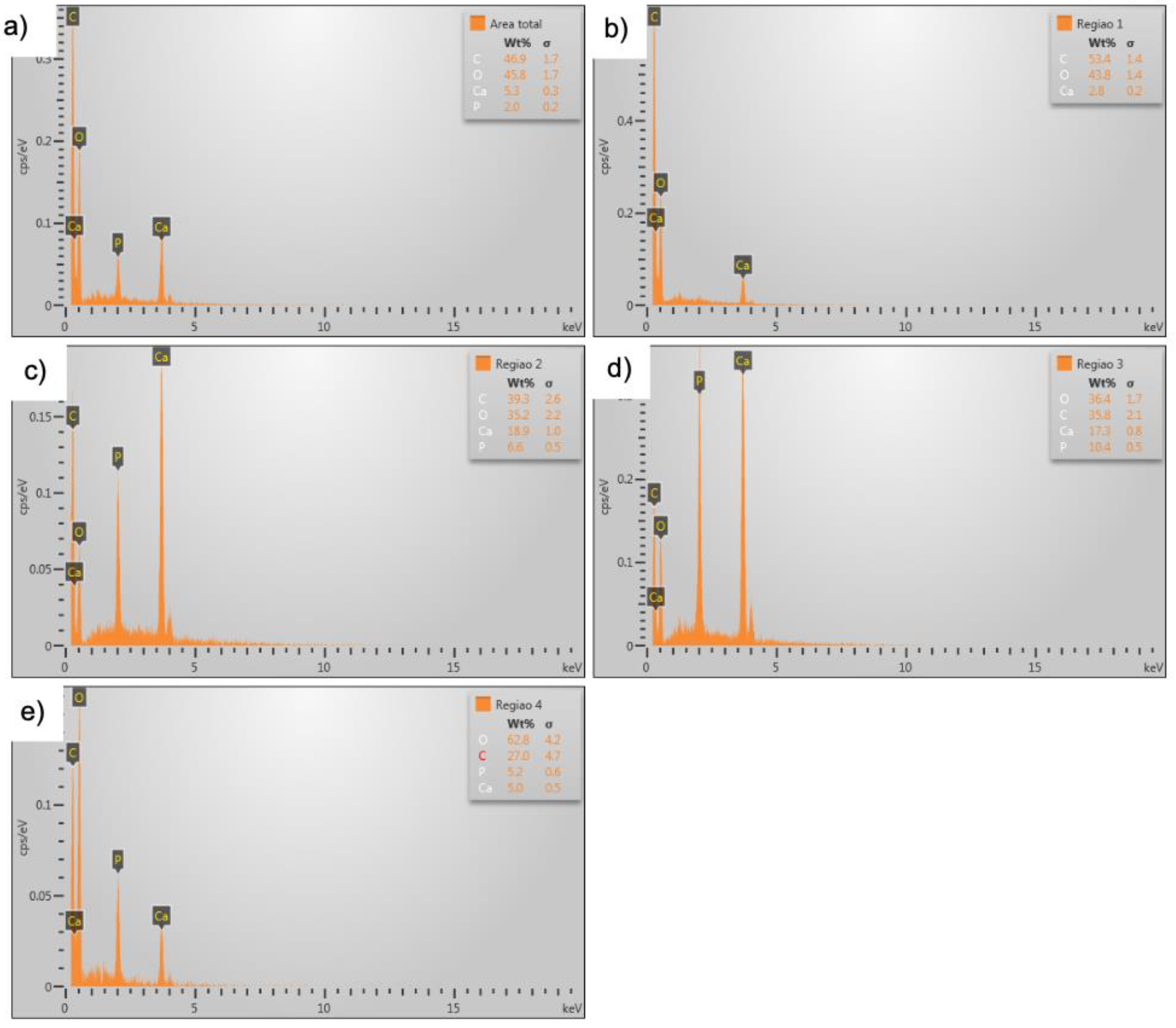

Microanalysis of Calcium Phosphate

In the microanalysis of the sample containing calcium phosphate, it was possible to identify the chemical elements forming the n-HA/β-TCP and type 1 collagen composite. (

Figure 5a–e)

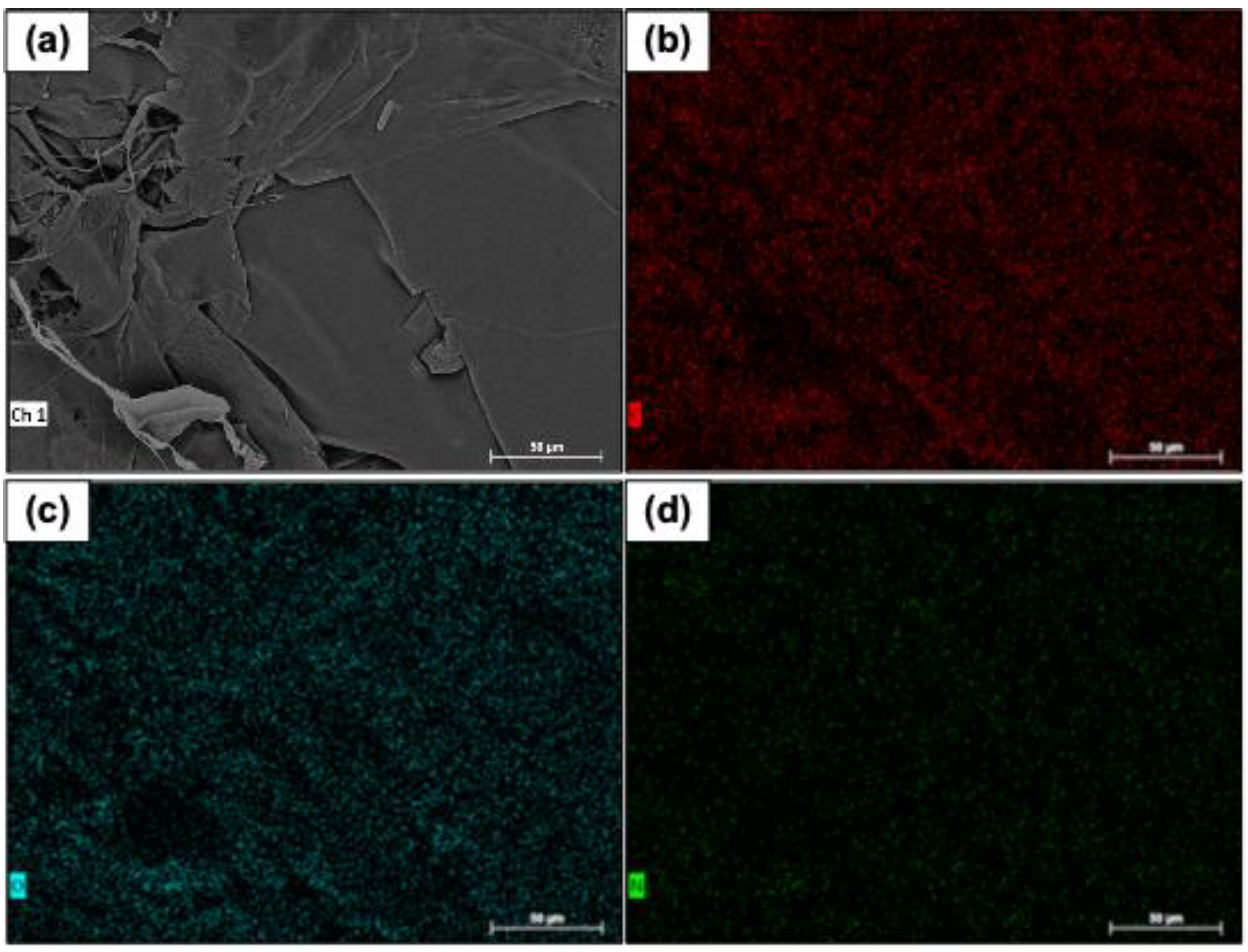

The chemical percentages of type 1 collagen fibers were recorded, and no impurities were identified. The

Figure 6 shows images of the mapping of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen distribution on the samples' surfaces.

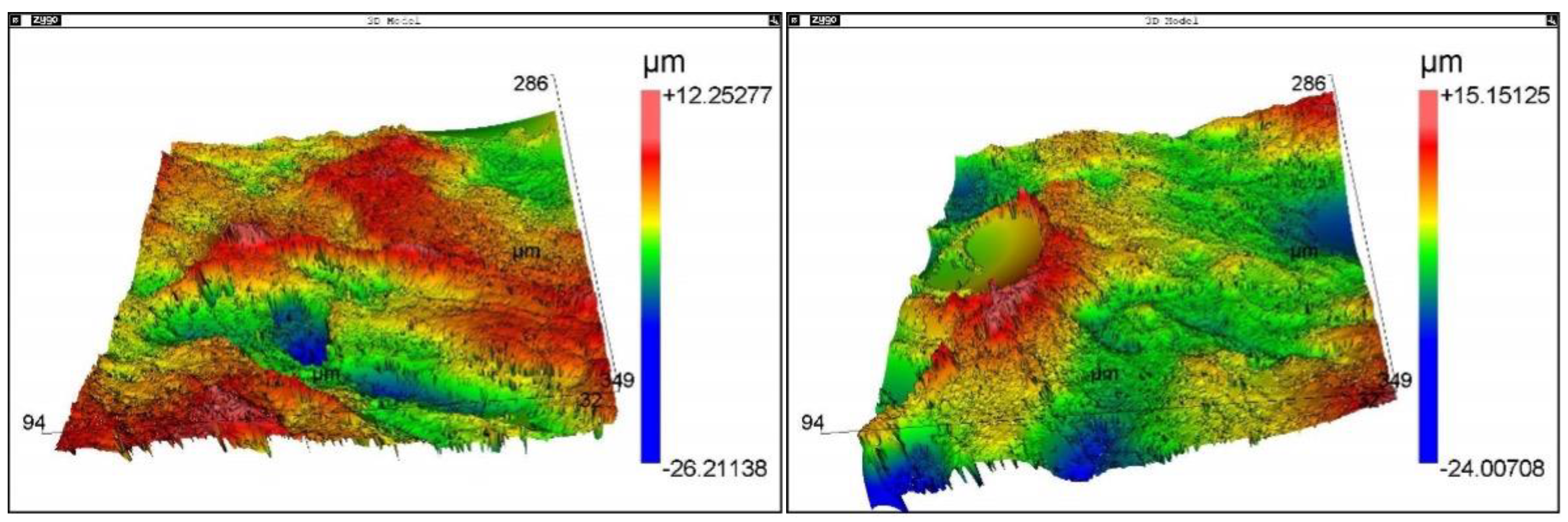

Roughness

Figure 7 shows the image

collagenous type 1 surface morphology obtained by interferometry during roughness measurements. The surface was homogeneous. The roughness surface Ra 12.9 µm, Rms 13.1 µm, and Rku 1.1 µm.

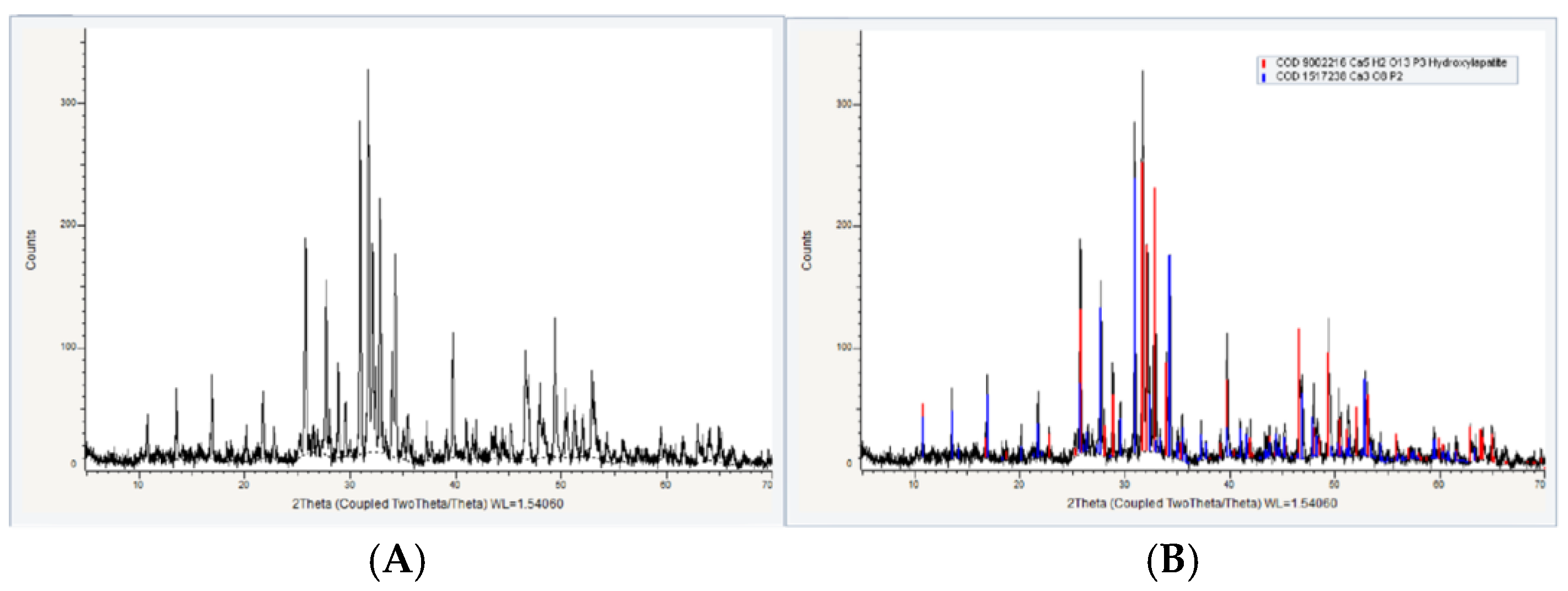

The X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Figure 8 shows the diffraction spectra and peaks of the crystalline phases. The peaks of the diffractograms were identified based on information from the database using the Diffrac software. EVE. V4.22.

Discussion

The herein morphological and chemical biomaterial analysis indicates that nano-hydroxyapatite/β-Tricalcium phosphate (n-HA/β-TCP) and type 1 collagen composite is perfectly suitable for further in vivo testing.

The development of new graft biomaterials is an excellent alternative to improve the performance of the regenerative properties for patient treatments and adding other types of components to hydroxyapatite has been proven to do so.

Literature data showed that adding chitosan to nano-hydroxyapatite improved osteogenesis and reduced bacterial adhesion [

10].

The collagen molecule contributes to key aspects of bone regeneration, such as: cell migration, attachment, migration, cell division and differentiation. Therefore, collagen participates in osteinduction and osteoconduction in bone healing. In addition, collagen is the main scaffold that sustain mineralization in human body, notably in intrafibrillar mineralization pattern [

11,

12].

Previous work showed that the mixture of hydroxyapatite with collagen had characteristics such as microstructure, absorption kinetics, and mechanical properties suitable as bone substitutes [

11]. The results of the present work corroborate those cited in the literature [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Figure 3 shows the interaction between calcium phosphate and collagen.

A study using rabbits confirmed through several tests, including microanalysis, that the calcium concentration in the material can form different types of hydroxyapatites [

19]. In the tests carried out in the present work, it was possible to verify that the percentages of calcium and other chemical elements were similar to those of hydroxyapatite.

Figure 3b shows n-HA granules.

The identification of material phases is mainly determined by XRD testing [

20,

21,

22]. Data from the literature showed that the percentage of nano-hydroxyapatite was similar to that of dentin. The nano-hydroxyapatite induced more collagen cross-links, increased the rate of organic matrix, and promoted better mineralization [

23].

The association of nano-hydroxyapatite with collagen was analyzed in tests, and the results were compared with materials containing only hydroxyapatite. The results showed that the structure and performance can be improved by mixing appropriate percentages of collagen and hydroxyapatite [

24].

In fact, when nano-hydroxiapatite is mixed with n-HA, the cell viability, cell integration and differentiation processes were improved [

25].

Moreover, it was demonstrated that n-HA and collagen scaffolds acted synergistically in osteoconduction process and that bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP7) and (BMP2) participated in the process [

26].

The results obtained in the present work extended the previous works. It should be noted that the percentages of nano-hydroxyapatite and collagen influence the biomaterial's performance in bone repair.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained in the present work, it can be concluded that the analyzed nano-biomaterial composed of nano-hydroxyapatite/β-Tricalcium phosphate (n-HA/β-TCP) and type 1 collagen composite does not contain manufacturing processing impurities and is suitable for in vivo assays.

Author Contributions

Igor da Silva Brum: Conceptualization and co-wrote the manuscript. Carlos Nelson Elias: analysis of results, writing review, Marco Antonio Alencar de Carvalho, Guilherme Aparecido Monteiro Duque da Fonseca, Bianca Torres Ciambarella and editing, Lucio Frigo co-wrote the manuscript. Jorge José de Carvalho: Analyze the experimental results of the materials. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

The author’s informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Brazilian Agencies CAPES, CNPq, FAPERJ, and FINEP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, L.; Wei, M. Biomineralization of Collagen-Based Materials for Hard Tissue Repair. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lazarevic, M.; Petrovic, S.; Pierfelice, T.V.; Ignjatovic, N.; Piattelli, A.; Vlajic Tovilovic, T.; Radunovic, M. Antimicrobial and Osteogenic Effects of Collagen Membrane Decorated with Chitosan-Nano-Hydroxyapatite. Biomolecules. 2023, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, K.H.; Seo, J.H.; Pack, S.P. Biomimetic Scaffolds of Calcium-Based Materials for Bone Regeneration. Biomimetics (Basel). 2024, 9, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carolina, D.N.; Satari, M.H.; Priosoeryanto, B.P.; Susanto, A.; Sukotjo, C.; Kartasasmita, R.E. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Four Different Concentrations of Ant Nest (Myrmecodia pendens) Collagen Membranes with Potential for Medical Applications. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2024, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tay, F.R.; Carvalho, R.M.; Yiu, C.K.; King, N.M.; Zhang, Y.; Agee, K.; Bouillaguet, S.; Pashley, D.H. Mechanical disruption of dentin collagen fibrils during resin-dentin bond testing. J Adhes Dent. 2000, 2, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zilm, M.; Wei, M. Fabrication of intrafibrillar and extrafibrillar mineralized collagen/apatite scaffolds with a hierarchical structure. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2016, 104, 1153–1161. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2016, 104, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Brum I, de Carvalho JJ, da Silva Pires JL, de Carvalho MAA, Dos Santos LBF, Elias CN. Nanosized hydroxyapatite and β-tricalcium phosphate composite: Physico-chemical, cytotoxicity, morphological properties and in vivo trial. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 19602. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Truite, C.V.R.; Noronha, J.N.G.; Prado, G.C.; Santos, L.N.; Palácios, R.S.; do Nascimento, A.; Volnistem, E.A.; da Silva Crozatti, T.T.; Francisco, C.P.; Sato, F.; Weinand, W.R.; Hernandes, L.; Matioli, G. Bioperformance Studies of Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Scaffolds Extracted from Fish Bones Impregnated with Free Curcumin and Complexed with β-Cyclodextrin in Bone Regeneration. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, X.; Bai, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. A variable mineralization time and solution concentration intervene in the microstructure of biomimetic mineralized collagen and potential osteogenic microenvironment. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1267912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lazarevic, M.; Petrovic, S.; Pierfelice, T.V.; Ignjatovic, N.; Piattelli, A.; Vlajic Tovilovic, T.; Radunovic, M. Antimicrobial and Osteogenic Effects of Collagen Membrane Decorated with Chitosan-Nano-Hydroxyapatite. Biomolecules. 2023, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kavitha Sri, A.; Arthi, C.; Neya, N.R.; Hikku, G.S. Nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen composite as scaffold material for bone regeneration. Biomed Mater. 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, V.; Sekaran, S.; Dhanasekaran, A.; Warrier, S. Type 1 collagen: Synthesis, structure and key functions in bone mineralization. Differentiation. 2024, 136, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Brum I, Elias CN, Nascimento ALR, de Andrade CBV, de Biasi RS, de Carvalho JJ. Ultrastructural and Physicochemical Characterization of a Non-Crosslinked Type 1 Bovine Derived Collagen Membrane. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 4135. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Silva Brum I, Frigo L, Goncalo Pinto Dos Santos P, Nelson Elias C, da Fonseca GAMD, Jose de Carvalho J. Performance of Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate and Xenogenic Hydroxyapatite on Bone Regeneration in Rat Calvarial Defects: Histomorphometric, Immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural Analysis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021, 16, 3473–3485. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Silva Brum I, Frigo L, Lana Devita R, da Silva Pires JL, Hugo Vieira de Oliveira V, Rosa Nascimento AL, de Carvalho JJ. Histomorphometric, Immunohistochemical, Ultrastructural Characterization of a Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate Composite and a Bone Xenograft in Sub-Critical Size Bone Defect in Rat Calvaria. Materials (Basel). 2020, 13, 4598. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ten Huisen, K.S.; Martin, R.I.; Klimkiewicz, M.; Brown, P.W. Formation and properties of a synthetic bone composite: Hydroxyapatite-collagen. J Biomed Mater Res. 1995, 29, 803–810. J Biomed Mater Res. 1995, 29, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.R.; Rodriguez, D.E.; Gower, L.B.; Monga, M. Association of Randall plaque with collagen fibers and membrane vesicles. J Urol. 2012, 187, 1094–1100. J Urol. 2012, 187, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruano, R.; Jaeger, R.G.; Jaeger, M.M. Effect of a ceramic and a non-ceramic hydroxyapatite on cell growth and procollagen synthesis of cultured human gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontol. 2000, 71, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serre, C.M.; Papillard, M.; Chavassieux, P.; Boivin, G. In vitro induction of a calcifying matrix by biomaterials constituted of collagen and/or hydroxyapatite: An ultrastructural comparison of three types of biomaterials. Biomaterials. 1993, 14, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohira, T.; Ishikawa, K. Hydroxyapatite deposition in articular cartilage by intra-articular injections of methylprednisolone. A histological, ultrastructural, and x-ray-microprobe analysis in rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986, 68, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Gao, J.; Xing, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, G. Comparative evaluation of the physicochemical properties of nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen and natural bone ceramic/collagen scaffolds and their osteogenesis-promoting effect on MC3T3-E1 cells. Regen Biomater. 2019, 6, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- El-Fiqi, A.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.W. Novel bone-mimetic nanohydroxyapatite/collagen porous scaffolds biomimetically mineralized from surface silanized mesoporous nanobioglass/collagen hybrid scaffold: Physicochemical, mechanical and in vivo evaluations. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020, 110, 110660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Heo, S.Y.; Oh, G.W.; Yi, M.; Jung, W.K. A 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone/Marine Collagen Scaffold Reinforced with Carbonated Hydroxyapatite from Fish Bones for Bone Regeneration. Mar Drugs. 2022, 20, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Epasinghe, D.J.; Kwan, S.; Chu, D.; Lei, M.M.; Burrow, M.F.; Yiu, C.K.Y. Synergistic effects of proanthocyanidin, tri-calcium phosphate and fluoride on artificial root caries and dentine collagen. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017, 73, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enrich-Essvein, T.; Rodríguez-Navarro, A.B.; Álvarez-Lloret, P.; Cifuentes-Jiménez, C.; Bolaños-Carmona, M.V.; González-López, S. Proanthocyanidin-functionalized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as dentin biomodifier. Dent Mater. 2021, 37, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.F.; Wang, C.Y.; Wan, P.; Wang, S.G.; Wang, X.M. Comparison of bone regeneration in alveolar bone of dogs on mineralized collagen grafts with two composition ratios of nano-hydroxyapatite and collagen. Regen Biomater. 2016, 3, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).