1. Introduction

Non-governmental organizations (hereinafter: NGOs) are essential for advancing social ideals, sustainability, and moral responsibility in the fast-paced commercial world of today. Good corporate governance (hereinafter: GCG) (Iskander and Chamlou 2000; Young and Thyil 2008) and corporate social responsibility (hereinafter: CSR) (Riyanto and Toolsema 2007; Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon, and Siegel 2009; Ntim and Soobaroyen 2013; Shahab and Ye 2018) are two topics that are becoming more and more important, particularly for non-for-profit organizations (Gill 2008; Jamali, Safieddine, and Rabbath 2008; Kluge and Schömann 2008; Levy 2010; Bobby Banerjee 2014; Rahim and Alam 2014; Waters and Ott 2014; Crifo and Rebérioux 2016; Aras and Crowther 2016; Popescu, Hitaj, and Benetto 2021; Valentinov 2021). This article explores the evolution of GCG practices and the challenges faced by NGOs in Slovenia, one of the EU relatively new member states from year 2004, but as a country with a rich cultural heritage and an engaged civil society, represents a challenging area for the implementation of GCG in the NGO sector. Understanding the non-Western context and specificities of Slovenian non-for-profit organizations is crucial for identifying essential elements shaping the approach to GCG with CSR & business morality framework. The impact of CSR in the context of Slovenian small and medium enterprises has been discussed in the recent past in another place (Author 2012).

The main aim of current study is a deeper understanding of the development of GCG practices within Slovenian NGOs and the identification of challenges arising from their implementation in a specific cultural, legislative, and economic environment. We will attempt to answer research question RQ1 regarding how the implementation of GCG in Slovenian NGOs will contribute to strengthening their legitimacy, stakeholder trust, reputation, and effectiveness in achieving social goals. In addressing this question, the article will use a theoretical framework that encompasses classical GCG concepts. Furthermore, it will integrate stakeholder theory with the “triple bottom line” approach (Elkington and Rowlands 1999) to better understand the connections between GCG and the framework of CSR (and business ethics in general) in the context of NGOs. The research is conducted based on the phenomenological reduction method of key phenomena in the governance bodies of public institutes, as discussed further in section 3. This methodology provides us with an integrative, holistic and multidimensional insight into current GCG practices and the creation of relevant recommendations for their improvement in the near future (see section 5 below). Therefore, we aim to find an answer to our fundamental research question (RQ1) through a critical reflection on key aspects of GCG to achieve the proper type of management & leadership by governance bodies in the context of non-governmental and / or non-profit organizations. The article provides insight into our conducted theoretical-conceptual investigation and how these elements contribute to increasing the trust, reputation, efficiency and long-term sustainability of NGOs.

We will also be interested in the phenomenon of the correlation between managements bodies of NGOs, trust vs. reputation as indicators of commitment to CSR agenda and GCG to identify key points of interaction between them and socially responsible practices in the context of specific goals and values of external & internal environment in which actually operate Slovenian NGOs. The research will focus on determining how the implementation of GCG supports the achievement of socio-economic, cultural-historical, and, above all, mission of a non-for-profit organization. Concrete examples of adaptations in the governance structure, decision-making, and internal processes in Slovenian NGOs will be taken into account to enhance GCG procedures. The examination of challenges arising from the specific nature of the non-for-profit sector, including issues related to controlling, reward systems, and the accountability of members of governing bodies and employees, represents one of the key objectives of this article.

The analysis will focus on how GCG facilitates and practices building the trust and collaboration with their main stakeholders. In this context, it is particularly important to explore how business ethics (Crane and Matten 2007; De George 2006; Ferrell, Fraedrich, and Ferrell 2008; Fisher and Lovell 2006; Author 2000) – meaning its key concepts such as conscience, duty, responsibility, virtues, integrity, norms, and codes of conduct in business, along with regular, fair, and comprehensive reporting – support harmonious, trustworthy, and sustainable relationships with stakeholders. The identification of specific challenges related to cultural, legislative, and economic conditions in Slovenia that influence compliance with GCG standards in developed Western societies is also one of the objectives of this article. In traying to reach it, we will rely on the warning found in the recently published paper, which based on “reviews a family of multilevel models that can be used to build general theories of the nonprofit sector that are still sensitive to variations in context” (Zhao, Galaskiewicz, and Yoon, 2022, 5). Finally, the article will address proposals for concrete measures that Slovenian NGOs can take to improve their GCG practices. This includes changes to CG structures, training for governing bodies, the establishment of ethical guidelines, strengthening stakeholder relationships, and considering how the future development of GCG norms may impact adjustments and innovations in Slovenian NGOs.

2. Theoretical Background

An insight into relevant literature shows that CSR is a key element that assists non-for-profit organizations in achieving their goals by providing a framework for managing organizations in an ethical, transparent, and responsible manner towards all stakeholders (Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon, and Siegel 2009; Hatcher 2002). It emphasizes the importance of both moral CG and “key stakeholders’ influence on the enterprise’s core values, culture, the ethical climate, and informal and formal measures of business ethics implementation as the constitutional elements of enterprise ethical behavior” (Belak 2013, 527). Additionally, research has explored the impact of corporate digital responsibility on building digital trust, determining Responsible Corporate Digital Governance in the global economy undergoing the process of digital transformation (Authors. 2022). Existing literature investigating the role of the board of directors as a core element of GCG in CSR performance has been synthesized and critically evaluated by some researchers (Bolourian and Alinaghian 2021). Therefore, it is not surprising that GCG is on the rise even in the non-for-profit sector. The following are key authors and topics relevant to the study of GCG in the perspective of CSR, whose theoretical considerations will undoubtedly be incorporated into our present work:

- (i)

Concept of Shared Values which explores how corporations can create social value through their business operations (Porter and Kramer 2011);

- (ii)

Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Concept, encompasses economic, social, and environmental dimensions of business (Elkington and Rowlands 1999), including critical analysis of TBL (Norman and MacDonald 2004) and a systematic review of literature on the topic (Loviscek 2020);

- (iii)

OECD Guidelines and Norms which provide a framework for GCG & CSR, covering five basic subjects: 1) protection of shareholders rights; 2) equitable treatment of shareholders, including full disclosure of material information and the prohibition of abusive self-dealing and insider trading; 3) recognition and protection of the exercise, of the rights of stakeholders as established by law and encouragement of co-operation between corporations and stakeholders in creating wealth and jobs in enterprise; 4) timely and accurate disclosure and transparency with respect to matters material to company performance, ownership and governance, which should include an annual audit conducted by an independent auditor; and 5) a framework of CG ensuring strategic guidance of the company and effective monitoring of its management by the board of directors as well as the board‟s accountability to the company and its shareholders (OECD 2010). How their implementation looks like, for example, in green banking whose development on the basis of the principles of sustainable development should have a balance on three viewpoints (Triple Bottom Line), they are Profit (Economy), People (Social) and Planet (Safe Environment) (Dialysa 2015);

- (iv)

Stakeholder Theory that emphasizes the importance of collaboration with various stakeholders in business with divergent interests and needs that corporate governance must balance to ensure each stakeholder receives their share of the value added by the company (Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, and Colle 2010; Freeman, Harrison, and Zyglidopoulos 2018; Freeman, Phillips, and Sisodia 2020; Freeman 2023);

- (v)

European Commission Guidelines and Initiatives related to CSR and GCG (European Commission 2011);

- (vi)

Comprehensive Understanding of the Relationship between Management and Corporate Responsibility that is particularly important in non-business organizations (such as NGOs or government agencies) where this relationship is more crucial due to the absence of market discipline imposed on business organizations (Drucker, 1954).

The importance of GCG for its efficiency and success is increasingly recognized by public institutes, societies, public interest societies, institutions, and foundations in Slovenia (Golob and Bartlett 2007). The evolution of GCG practices in the non-for-profit sector in Slovenia shows that, for some authors, there haven’t been positive shifts and changes in GCG practices in the non-for-profit sector in Slovenia in recent years, as they are illustrative of “the failed transformation of Slovenia’s corporate governance process and its consequences” (Lahovnik 2019, 613). For some authors, moreover, the entire non-for-profit sector has remained marginalized on the fringes of social events (Kovač 1999, 3). Perhaps nowhere more than in Slovenia is “the discrepancy between managerial theory and practice so wide and the schism so deep as in the field of non-for-profit organization management” (Author 2002a, 19). Therefore, it is not surprising that a comprehensive treatment of this issue at the beginning of the transition in the 1990s was scant in the literature, as it can be found in only a few places (Author 2002; Kranjc-Žnidaršič 1996; Rus 1994; Trunk Širca and Tavčar, 1998;). Treatment of individual aspects or dimensions of NGOs management can be found in works by distinguished Slovenian academics, researchers, and activists in the field of civil society published in a book titled Navigating through Turbulent Waters of NGO Management edited by Author (2002) which includes: a) various scientific-theoretical approaches to the study of NGOs (Kolarič 2002, 29-44), b) economic aspects of NGO management (Hrovatin 2002, 71-92), c) characteristics of Human Resource Management (HRM) in the non-for-profit sector (Svetlik 2002, 93-104), d) analysis of policies, actors, models, and community policy planning (Fink Hafner 2002, 105-124), e) the relationship between NGOs and Slovenian civil society, public services, the state, church, political parties, and profit organizations (Hren 2002, 125-134), f) the challenge that NGO management faces the influence of the relationship between civil society and the political subsystem on the social regulation of the socio-system in transition (Author 2002b, 135-152), g) NGOs, management, and the process of change (Lewis 2002, 153-160), h) NGOs as learning organizations (Raos,2002, 161-182), i) NGO leadership using the example of management in higher education in Slovenia (Trunk Širca 2002, 183-198) and at the University of Bristol in England (Stevenson 2002, 277-294), j) public relations (Verčič 2002, 199-212), k) lobbying (Kovač 2002, 213-230), l) negotiations (Svetličič 2002, 231-248), m) fundraising techniques (Čandek 2002, 249-264), n) operative solutions and measures related to grant applications in the non-profit sector – case study EU (Cochard 2002, 265-276), o) current events in the field of NGOs in Slovenia and trends for the future (Šporar 2002, 313-338), p) some possibilities for the development of the non-for-profit and NGO sector using the example of the introduction of European regional structural policy in Slovenia (Horvat 2002, 339-351) and, finally r) a typical obstacles, challenges and pitfalls of managers of the third sector (Author 2002a, 11-28).

Since it has become clearer “that effective corporate governance is essential to a firm’s performance” (Lahovnik 2019, 613), literature has reflected an increased understanding of the role of the Third sector in the welfare society. In this context, some authors attempt to comprehend the position of the Third sector within the Slovenian welfare system through a comparative analysis of its characteristics and its role in other post-socialist and European countries (Črnač-Meglič and Rakar 2009). Both individuals and NGOs are dedicating more resources and willingness to address the most pressing social and environmental challenges, operating in a GCG responsible and sustainable CSR manner, driven by the spirit of the times. As many as 35% of Slovenians (source: Philanthropy in Central & Eastern Europe 2022) are already willing to pay more for products and services offered by socially responsible brands, understanding that greater social engagement is in the best interest of all. We have already contributed to the ongoing discussion about the prevailing model of ethical consumerism in Slovenia in two other works (Authors 2013; 2014).

3. Materials and Methods

In one recently published review of the literature that appeared in non-profit journals over the last four decades, the authors found a frightening finding that only 4% of articles published “adopt critical approaches, with great variability in the ways articles exemplify core tenets of critical scholarship, and a general dampening of critical work over time”. All others are written in the conservative spirit of “more mainstream (positivistic) models of social science” (Coule, Dodge, and Eikenberry, 2022, 478). Regarding this study, we aim to become part of the first marginalised group of authors who use a critical methodological approach. A method we employed in this conceptual article is rooted in a philosophical worldview constructed through a coherent synthesis of several divergent and eo ipso incompatible directions but only on first sight. We decided to combine the intellectual strength of Aristotle’s classical practical philosophy, especially its ethical dimensions developed in the works Nicomachean Ethics (Aristotle 1953) and Politics (Aristotle 2000) with: 1) contemporary philosophy of politics, history, and law, as well as scientific organizational theory; 2) phenomenology, that is, its method of reducing everything ephemeral in experience to break through to the eidetic essence of things themselves (Husserl 1905/1975) ; 3) the analytical philosophical method of meticulous analysis of the research subject together with the precision of its expression in language (Ayer, 1971); and finally, 4) the ’critical theory of society’ inspired by a young Marx, further developed by representatives of the so-called Frankfurt Marxism (Marcuse 1972; 1992; Horkheimer 1974; Horkheimer and Adorno 1974; Adorno, 1979) and Yugoslav praxis-Marxism (Marković, Petrović, Kangrga, Supek, Tadić, Golubović, and many others) in an effort to make the World of Human Affairs a better place for human life. Although we already hear loud dissent coming from the mouths of orthodox defenders of each of these circles or schools individually, this will not discourage us, much less waver us, from studying the mentioned phenomena using Slovenia as an example. We will test the strength of such a new alliance of essential thinking that does not allow itself to fall into eclecticism for a moment, that is, into that mixture of incompatible elements that those who consider themselves their guardians/gatekeepers jealously try to preserve.

We also relied on a critical reflection of relevant literature, analysis of the content of key documents and legal acts in the subject area, as well as on secondary data, anecdotal evidence, controlled observation of phenomena relevant to understanding the relationship between GCG and CSR in NGOs, and finally, on our own multi-year practical managerial experience as directors & deans (of three institutions: radio, scientific institute, and faculty) and as the president of the Broadcasting Council of the Republic of Slovenia (2006-2017), a regulatory body in the field of electronic media. In short, data will be collected through the descriptive analysis method, literature study, and theoretical analysis. Based on the results obtained in this structured case study, we have proposed necessary changes of GCG procedures to achieve the modernization of the Third sector, enabling it to finally ’breathe freely’ after three decades of wandering in the post-socialist transition period, as is the case with its counterpart in developed Western societies.

3.1. Current State of the Affaires at the Subject-Matter of Our Study

Despite the fact that Slovenia has been in the process of post-socialist transition for more than three decades, there is considerable confusion in the field of CG, which is partly inherited from the past, and partly an inevitable companion of the Zeitgeist of the new era of transition from a socialist mind-set of Actors to a capitalist one. In their minds, the myth of amoral business (De George 2006, 5-8) still resonates, which, due to the introduction of the perspective of CSR and business ethics in general, has lost its former persuasiveness even in the area that is considered its birthplace - the economy. Therefore, the real dilemma is no longer which management method is more suitable for profit-making and which for non-profit organizations, but which management and leadership philosophy and business culture are useful for successful and effective GCG in NGOs. It does not matter whether it is an industrial company or a public institute, both must be managed according to such principles and models of GCG that can lead to the organizations realizing the goals and purposes for which they were founded. It is no longer essential whether the emphasis is on material profit that is the owner’s private interest or the founder’s mission, public interest, common good. It is important to get the organization out of the survival zone, that is business at the so-called “positive zero” in which it was during the half-century period of so called “real-socialism” (1945-1991) and shifted to the zone of prosperity. Unfortunately, one of our findings indicates that the vast majority of NGOs in Slovenia are still in the first mentioned zone, which, in our opinion, represents, among other things, a serious GCG fiasco.

In Slovenia, there are currently several types of NGOs operating based on their legal-organizational status. These include societies, associations of societies, societies of public interest, institutions, foundations, public institutes, and more recently, social enterprises. As of December 4, 2023, there were 27,399 registered non-governmental organizations in Slovenia, including 23,237 societies, 3,902 (private) public institutes, and 260 institutions. This is 8 fewer than on November 17, 2023, when there were 27,407 NGOs, including 23,236 societies, 3,907 (private) public institutes, and 264 institutions. After years of expansion, the number of NGOs has been gradually declining in recent years. As of September 17, 2012, for instance, there were 2,324 institutes, 251 institutions, and 22,490 registered societies. There were 27,550 NGOs as of November 4, 2022, comprising 260 institutions, 3,831 (private) public institutes, 23,459 societies, and other organizations. It’s crucial to remember that not all NGOs with registration are always in operation. As per customary procedures, NGOs in active status are those that file their annual reports with the Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Public Legal Records and Related Services (AJPES). This group of NGOs is roughly 3% smaller than that of registered NGOs. As a result, according to CNVOS (2023), there were marginally over 27,500 active societies, public institutes, and institutions in 2022.

In the non-governmental sector, we employ slightly more than 12,000 people (for example, in 2021, the total number of employees was 12,561). More than half of all workers are employed in public institutes, although they represent only 13.00% of all non-governmental organizations. The vast majority of NGOs (92.17%) do not have a single employee, with the highest percentage being societies (95.48% of all societies) and the lowest being public institutes (70.11% of all institutes). In terms of the number of employees in an organization, public institutes take the lead, employing more than half of all workers in the sector. At least one employee is found in 4.52% of societies, 29.89% of public institutes, and 6.33% of institutions. On average, each Slovenian NGO has 0.48 employees. The average varies considerably when looking at different legal-organizational forms: each public institute has an average of 2.13 employees, while institutions and societies have an average of 0.23 employees (source: CNVOS 2023).

In the year 2021, non-governmental organizations generated just over a billion euros in revenue, with societies contributing 60.41% to this total. 89.38% of NGOs had less than €50,000 in revenue, and 19.25% operated without any income. Despite the economic and financial crisis, NGO revenues had been growing until 2020 when they were lower than the previous year for the first time. Society revenues decreased in 2011 and 2013 compared to the previous year but have been steadily increasing since then, surpassing pre-reduction levels by 2016. In 2018, society revenues increased by 3.04%, followed by a 6.63% increase in 2019. However, they experienced a 15.56% decline in 2020. In 2021, society revenues rebounded, increasing by 18.89% and surpassing the 2019 levels. Public institutes only had a decrease in revenue in 2012, but by 2013, they had higher revenues than before the crisis. Institutional revenues decreased in 2011 and 2014 compared to the previous year, only surpassing pre-crisis levels in 2015. In 2016 and 2017, there was again a decline in institutional revenues, dropping below the 2009 levels. It was only in 2018 and 2019 that they rose again above the crisis levels. In 2020, institutions experienced a revenue decline of just over 28%. In 2021, institutional revenues increased by 14.39%, but they did not reach the levels from 2019 (source: CNVOS 2023).

In 2021, the total revenues of NGOs represented 2.10% of Slovenia’s GDP (SURS, 2023). Such a modest share of NGO revenues relative to the gross domestic product is one of the indicators of the development or, more precisely, the marginalization of the non-governmental sector in Slovenia. This share is considerably lower than in other countries. The last major international comparative study by Johns Hopkins University in 2013 calculated a global average of 4.13% and 3.8% in EU countries (CNVOS, 2023). The share of public revenues relative to all NGO revenues and the share of GDP that the state allocates to NGOs are two indicators of the development of the non-governmental sector in a particular country, indicating how much the state integrates NGOs into services provided to its citizens.

The share of public funds relative to all NGO revenues had been decreasing until 2017, when it became higher than the previous year after five years, reaching 35.57%. The growth continued, and in 2021, the share reached 46.35%. This growth surpassed the share from 2010, which was 40.01%. The increase in the share in 2021 was primarily contributed to by an increase in funds from the Ministry of Labor, Family, Social Affairs, and Equal Opportunities, specifically related to payments to personal assistance service providers. Another indicator of the share of GDP allocated by the state to NGOs is not encouraging either. In 2021, Slovenia allocated only 0.97% of its GDP to non-governmental organizations, while the global average was 1.38%, and in EU countries, it was as high as 2.20% of GDP (SURS 2023).

In the year 2003, NGOs received €166.76 million in public funds, while in 2021, they received €507.87 million. Out of this, €482.54 million came from direct and indirect budget users (ministries, municipalities, FURS, public agencies, and institutes), and €25.33 million came from the Foundation for the Financing of Humanitarian and Disability Organizations (FIHO) and the Foundation for the Financing of Sports Organizations in the Republic of Slovenia (FŠO). Of all transfers from budget users, 57.73% of the funds (€278.58 million) were received by non-governmental organizations recognized by the state as operating in the public interest. In 2021, public budget funds were successfully obtained by 15,037 non-governmental organizations, representing 52.80% of all active non-governmental organizations. In 2021, non-governmental organizations received a total of €245.49 million from ministries. Compared to 2003, this is an increase of 522.02%, or €206.02 million more, and compared to 2009, it is an increase of 213.25%, or approximately €167.12 million more. In 2021, the Ministry of Labor, Family, Social Affairs, and Equal Opportunities allocated the most funds to non-governmental organizations, accounting for 60.86% of all funds obtained by NGOs from ministries. Specifically, it allocated €107.99 million to non-governmental organizations for the provision of personal assistance (72.29% of all funds allocated by the ministry to NGOs), representing 43.99% of all public funds that ministries transferred to non-governmental organizations. Following this, the Ministry of Education, Science, and Sport contributed 19.96%, and the Ministry of Defence contributed 6.08% of all funds. Non-governmental organizations received €123.73 million from municipalities in 2021, which is an increase of 7.79% or €8.94 million compared to 2020. This is also 97.68% or approximately €61.14 million more than in 2003 and 34.93% or approximately €32.03 million more than in 2009 (source: CNVOS 2023).

3.2. Gaining Insight into the Essence of the Current State of Affairs and Conditions in the Non-for-Profit Sector

The phenomenological insight into the essence of the current state of affairs and conditions in the non-for-profit sector, which is the focus of our study, can be best achieved by formulating the following set of propositions (referred to as P1-Px):

P1: This sector continues to grapple with significant challenges primarily stemming from the unresolved issues of the post-socialist transition.

P2: Lack of self-awareness among owners: Ambivalence regarding ownership remains prevalent within the Third Sector, manifested in the fact that the founders of NGOs are both considered and not considered their actual owners.

P3: The enduring belief that civil society, non-for-profit organisations, or the public sector in its entirety are subsystems of the economy persists, with the latter being viewed as an autonomous, self-sufficient subsystem of modern, developed society that only actively generates new added value. The primary distinction is that the former is regarded as “non-economic activity,” which is viewed as harmful to the economy and symbolizes public spending and expenses that are essentially believed to impede economic growth.

P4: A chronic disparity exists between the lofty programmatic goals, mission, and values of NGOs on one side and the actual results achieved in practice on the other. Consequently, this mismatch leads to a state of dysfunctional governance and/or complete managerial incongruence. As noted by Author (2002a, 6), “one of the primary reasons for this divergency is the evident deficiency in the leadership and management of non-for-profit organizations”.

P5: In the context of the Third Sector in Slovenia, there still prevails a prejudice that “professional management will displace the significance of NGOs and transform them into capitalist enterprises” (Author 2002a, 6).

P6: Discrepancy between legal status regulation of non-profit organizations and concrete conditions of their functioning in practice: they are obliged to operate in a market environment with non-professional staff, volunteers, enthusiasts, amateurs, and so on, who are also underpaid for their work and often dissatisfied because of it.

P7: Chronic resource deficiency: The absence of comprehensive and stable financing for NGOs based on their mission and programs, as opposed to the prevailing practice of financing individual projects, has resulted in a situation where an increasing number of NGOs competing for financial support are confronted with increasingly limited sources. Moreover, more and more funders refuse to cover the entire project costs, instead requiring NGOs to secure co-financiers as a precondition for partial financial support for a project. Consequently, non-for-profit organizations in Slovenia often have very limited resources, undoubtedly complicating the implementation of GCG. The lack of systematic funding, a consequence of exclusively funding individual projects that are appealing to sponsors or the government, rather than supporting the overall functioning of the entire NGO, opens a persistent gap in their budgets. This creates stress, trauma, and frustration for their management, as they grapple with how to ensure their survival in a market-driven economic environment. This situation bears a striking resemblance to the conditions that prevailed at the onset of the development of liberal capitalism in the 19th century: ruthless competition, selfishness, self-sufficiency, and animosity among NGOs, which, in principle and in their declared mission, should collaborate, complement each other, connect, and create social networks within the World of Life, as opposed to the World of the System.

P8: Lack of expertise. Non-for-profit organizations in Slovenia exhibit a serious deficit of expertise in the field of GCG and management at all hierarchical levels. This is primarily due to their often-limited financial capabilities, preventing them from engaging and compensating educated personnel for undertaking such complex activities as GCG and their core operations. In the Third Sector, as of August of year 2023, according to data from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, there were approximately 12,000 employees compared to a total of over 931,200 active workers in the country (SURS 2023), representing a mere 0.0128%. As a result, NGOs are typically forced to: (i) employ sub-educated personnel merely to fill sensitive positions, and (ii) consolidate multiple different functions or departments into a single individual, creating “generals without an army”. In this way, middle managers become the sole workforce in their organizational units, while institute directors or society presidents become “know-it-all” as they must act as lawyers, economists, psychologists, HR professionals, educators, marketers, lobbyists, advisors, fundraisers, public relations specialists, influencers, and more if necessary.

P9:Lack of personnel in governing bodies and management: The dominant feature on the stage of the Third Sector is the personnel understaffing and managerial illiteracy, coupled with the simultaneous belittling of the role and significance of GCG & management for the successful realization of an NGO’s mission in practice. Prejudices inherited from the past, when the communist party pejorative labels as “techno-management” i.e., “ a deviation from the Party Line,” still persist. This deepens mistrust and aversion towards management as some kind of “foreign entity” in the realms of culture, healthcare, education, public services, and civil society. It was perceived as a spirit of capitalism and commercialization, finding its rightful place in the world of business and finance.

P10:Lack of an appropriate GCG culture. In the non-for-profit sector in Slovenia, there is still some resistance to the concept of GCG, perceiving it as a capitalist and bourgeois creation. This is compounded by a widespread misunderstanding of the essential need for: (i) Fundamental changes in the culture of non-for-profit organizations, including educating their leaders in managerial skills and acquiring necessary competencies and expertise in this field. (ii) A deeper understanding of the origins of the most significant current issues in this sector. (iii) Reflection on potentially meaningful paths to address post-socialist transitional challenges within it.

P11:Lack of autonomy. As seen above, since the majority of civil society organizations are funded from the state budget, they become dependent on the sole source of income. Consequently, they lose autonomy from the current political option in power in Slovenia when determining their mission, setting the agenda for their projects, and behaving in practice. The glaring paradox is that non-governmental organizations in Slovenia are primarily financed by the Slovenian government, turning them into “governmental non-governmental organizations,” which is a contradictio in adiecto. Instead of establishing and maintaining a constant and critical distance from the political subsystem, civil society organizations in Slovenia have recently merged with it. As a result of such developments, the term “NGO” increasingly becomes something of an oxymoron.

P12:Lack of ideological-political balance. The vast majority of non-governmental organizations not only espouse a leftist-anarchist worldview and engage in ideologies and practices reminiscent of regressive post-socialist doctrines but are also highly intolerant towards anything perceived as “right-wing,” “fascism,” “Janšism,” and similar labels.

P13:The lack of resistance against cliques as a paradigm of corporate culture in the non-profit sector. Due to the prevalence of this phenomenon and insufficient attention to it in domestic academic circles, with one of the rare exceptions being our empirical study on cliques within a broader research on organizational culture, using the example of Pošta Slovenije d.d. (Authors 2016), we had to rely on relevant global literature dealing with the phenomenon of corporate culture in general (Deal and Kennedy 1992; Hofstede 1994; Schein 1995; Brown 1998; Cameron and Quinn 2011), as well as specifically on the phenomenon of cliques[i]. For example, we find that Ashforth and Mael’s seminal work on social identity theory provides a framework for understanding the formation and impact of cliques in organizations. They argue that individuals are motivated to join groups that provide them with a sense of identity and belonging. Cliques can fulfil such needs by creating a sense of shared purpose and values among their members (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Cialdini and Trost’s work on social influence highlights the role of conformity in group formation and behaviour. They argue that individuals are more likely to conform to the norms of the groups they identify with. This can lead to the development of cliques with strong norms and a tendency to exclude outsiders (Cialdini and Trost 1998). Dill’s work on clique culture provides a detailed analysis of the characteristics and dynamics of cliques. He argues that cliques are often characterized by shared interests, strong bonds between members, and a sense of exclusivity. These factors can contribute to a clique’s power and influence within an organization (Dill 2005). Riordan and Shore’s research on organizational culture highlights the importance of a strong and positive corporate culture for organizational success. They argue that a culture that promotes open communication, collaboration, and respect can lead to increased employee engagement, productivity, and innovation. Cliques that foster negative or exclusionary behaviour can undermine a company’s overall culture and hinder its progress (Riordan and Shore 1997). ’Shared values and goals, cohesion, participance, individuality, and the sense of “we-ness” permeated clan-type firms. They seemed more like extended families than economic entities… typical characteristics of clan-type firms were teamwork, employee involvement programs, and corporate commitment to employees’ (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 46).

P14:Lack of adequate focus. In the non-profit sector, there is a complete preoccupation of employees, volunteers, and incompetent leadership with the organization’s mission, while simultaneously ignoring the importance of GCG, which is, so to speak, in the “blind spot” of key stakeholders. The consequences of such an attitude have not been absent, as they have plunged the entire sector into a serious endemic crisis with no apparent way out. There prevails a mindset that views the non-profit nature of the organization as automatically relieving its leadership and staff from any obligations to create added value. Productivity is consistently devalued to push forward organizational climate phenomena such as job satisfaction, feel-good, socializing, partying, in a word, enjoyment. For complete happiness, all they need is to find an altruistic donor who would generously finance such a circus.

We hold that the aforementioned set of propositions, which range from P1 to P14, most accurately captures the state of affairs in non-Western context and essence of the Zeitgeist that exists today in Slovenia with regard to the administration of NGOs, especially public institutes.

3.3. Legal-Organizational Framework of Corporate Governance in Public Institutes

From the above presented secondary data (see 3.1 above) and the postulated set of propositions (see 3.2 above), it is evident that

public institutes, although not dominant in terms of numbers, are actually the ones

with the highest number of employees and thus the highest human potential in business. In addition, they are the only ones with a legally regulated structure that allows them

to conduct economic as well as non-economic activities. Other forms of NGOs are not intended for such activities but only for carrying out their non-profit mission. Therefore, it will be interesting for us to examine the current structure and dynamics of CG in public institutes, considering the frameworks predetermined by the overarching Act on Public Institutes are such type of organizations,

whose goal is not to make a profit (see

Figure 1 below). It is indicative that the Act on Public Institutes was adopted in April 1991, which actually means at the time when Slovenia was one of the six administrative units of the former socialist federative Yugoslavia, and with minor cosmetic corrections it is still valid today. The CG regulation, which bears a clear stamp of “self-governing socialism” of the former regime, is shown in modern conditions to be outdated, inadequate and harmful. All attempts to change such kind of regulation in the last 30 years in the sense that it properly supports the models of best practices in the GCG have fallen into the water because the old ones still correspond to the interests of the left-wing governments that have been in power since independence for 4/5 of the time.

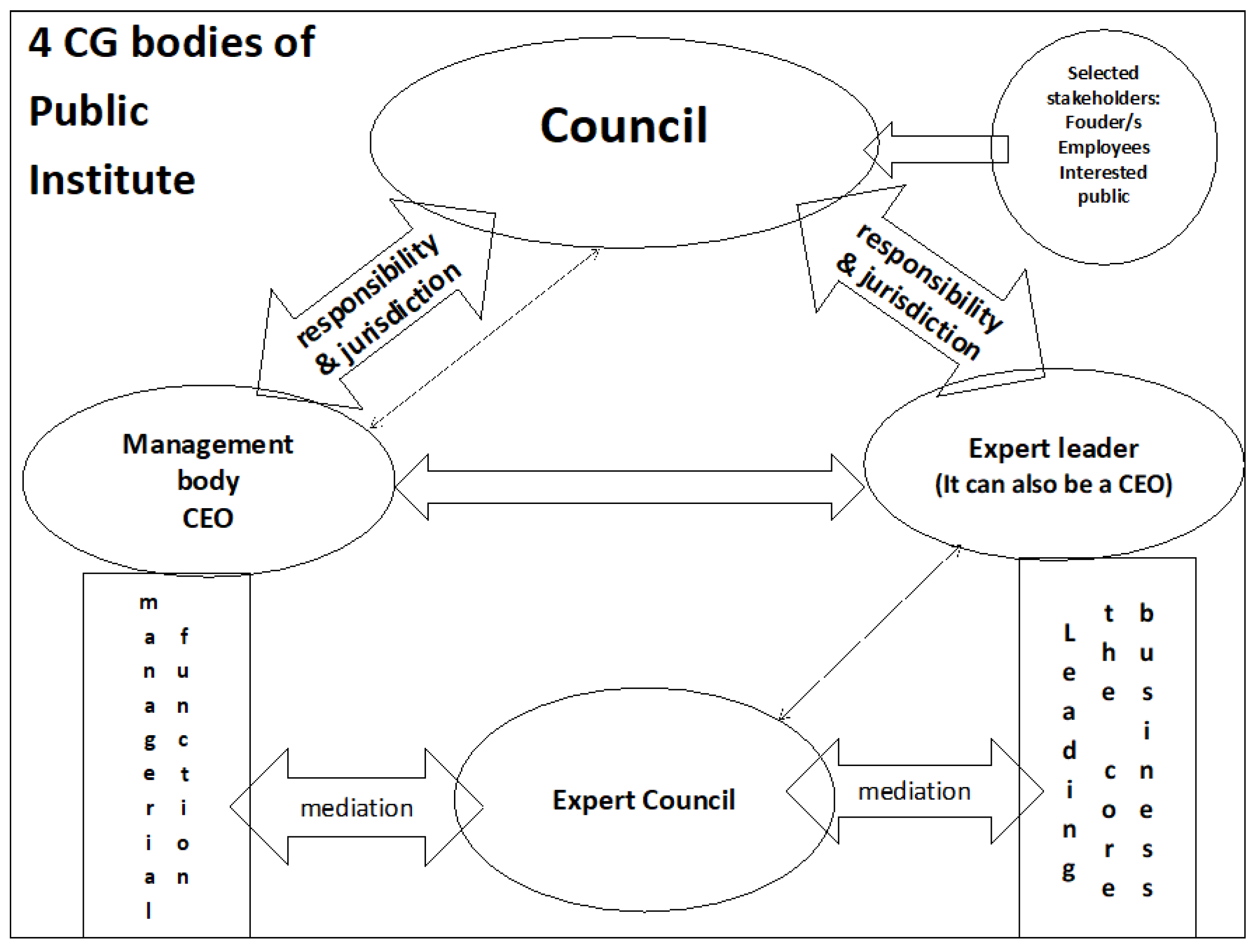

The public institute is governed by four bodies of CG as mandated by the law, which are as follows:

1) The Council as a collegiate governing body that consists of representatives of the strictly selected stakeholders such as founder/s, representatives of the public institute’s employees, and representatives of users and / or the interested public. The composition, method of appointment or election of members, term of office and powers of the council are determined by the law or act of establishment or by the statute or rules of the public institute (Article 29 of the Act on Public Institutes). Powers, jurisdiction and responsibilities of the Council are to adopts the statute or rules and other general / internal acts of the public institute, accepts the institute’s work and development programs and monitors their implementation, determines the financial plan and accepts the institution’s final account, proposes to the founder a change or expansion of the activity, gives proposals and opinions to the founder and director of the public institute on individual issues, and performs other matters determined by law or the act of establishment or by the statute or rules of the public institute (Article 30 of the Act on Public Institutes).

2) The CEO (Slovenian: direktor) as an individual management body who organizes and manages the work and operations of the institution, represents the public institute in external environment, is responsible for the legality of the institution’s work, manages the professional work of the public institute and is responsible for the professionalism of the institute’s work (unless the law or act of establishment, depending on the nature of the activity and the scope of work of the management function, stipulates that the management function and the function of managing the professional work of the public institute are separate) (Article 31 of the Act on Public Institutes). The CEO is appointed and dismissed by the founder, if the public institute’s Council is not authorized to do so by law or the founding act. When the Council of the public institute is authorized to appoint and dismiss the CEO of a public institution, the founder gives his consent to the appointment and dismissal, unless otherwise provided by law. If the management function and the function of leading the professional work of core business are not separated, the CEO is appointed and dismissed by the Council of the public institute with the consent of the founder (Article 32 of the Act on Public Institutes).

3) The Expert council as a collegiate professional body that deals with issues in the field of professional work of the public institute, decides on professional issues within the framework of the jurisdiction specified in the statute or rules of the public institute, determines the professional basis for the institute’s work and development programs, gives opinions and proposals to the Council, the CEO and the expert leader regarding the organization of work and conditions for the development of activities and performs other tasks specified by law or the act of establishment or by the public institute’s statute or rules. Its composition, method of formation and tasks are determined by the public institute’s statute or rules in accordance with the law and act of establishment (Articles 43-44 of the Act on Public Institutes).

4) The Expert leader: (i) manages the institute’s professional work, if it is so determined by law or act of establishment, and (ii) his or her rights, duties and responsibilities are determined by the statute or rules of the public institute in accordance with the law or act of establishment. He or she is appointed and dismissed by the Council of the public institute based on the prior opinion of the Expert council of the public institute, unless otherwise stipulated by law or the founding act (Articles 40-42 of the Act on Public Institutes).

We believe that the above explanations provide enough information to form a clear picture of the state of affairs in the area of our study.

4. Results

Let’s start present section by asking ourselves, first and foremost, what needs to be clarified in terms of analysis, interpretation of results, and/or critical commentary on the practical consequences of such legally defined model of governance in the non-profit sector, according to which, there are four independent governance bodies in public institutes participating in its administration, each in its own way.

What needs to be emphasized first is the conceptual confusion in the relationship between the founder and owner. An indicative fact is that the Act on Public Institutes was adopted in April 1991, a time when the Socialist Republic of Slovenia was part of the former Yugoslavia. This explains why it is nowhere explicitly stated that the founder is also the owner of the public institute and has all the rights that belong to an owner. Instead, the operation relies on a vague ideological formulation that the founder has “founding rights”, which is, incidentally, logically circular and thus ideal ground for manipulation in practice. For example, the founder created the institute as its subsidiary “child,” but is not responsible for its operations since they are not the owner of the public institute, but only its founder. However, if and when needed, they can transform into an owner without explicitly stating it. We must not forget that Bolshevism, as the ideological basis of self-management system, only recognized so-called societal ownership, prohibiting and persecuting all other forms, such as private, state, cooperative, and so on. Since dialectics, in the sense of the unification of opposites, is on the rise, anyone can act in any way that makes sense to them.

The next phenomenon that should be highlighted is the real possibility that the founder of the public institute may lose control over “their” institute. If we accept the previously mentioned scenario, then consequently, the founder as a somewhat “castrated” owner faces a very real danger of an informal group of stakeholders taking over the public institute. This is because, due to the lack of self-awareness as an owner and the absence of an appropriate corporate governance culture, they do not have the necessary mechanisms to prevent it. This is a common occurrence that, unfortunately, is only evidenced by anecdotal evidence because it doesn’t happen in the open but rather “under the radar,” in the deep shadow of captured public institutes, very similar to the phenomenon of a deep or captured state. This is why it has also remained below the radar of academic empirical research and the interest of the broader public, which could conclusively determine the actual state in this area.

In the described constellation, meaningful, efficient, and timely interaction between governance bodies is significantly hindered. This is due to their excessive number, composition and method of selecting members, decision-making structures and dynamics, complicated lines of subordination and superordination, loosely defined competencies and responsibilities. The fact that, apart from the CEO who is in regular employment, members of other bodies are generally ambitious, egocentric, power-seeking enthusiasts and/or volunteers without remuneration for their functions adds to the complexity. Furthermore, in the Third sector, members of governing bodies are often undereducated and insufficiently experienced for such managerial roles, potentially causing significant harm. Lastly, they often find themselves in conflicts of roles and interests.

Many individuals in the Third sector are involved in the activities of various institutions, state organs, media, etc. They operate in a “bumblebee-like flight” fashion: a little here, a little there, a bit everywhere. For example, one might start as an intern at a student NGO radio, then progress to becoming a journalist or presenter at a state or private radio station, all while being politically active. This political involvement can lead to public recognition and influence, eventually reaching the position of a parliamentary representative. After the term in office, they may secure a well-paid job as a PR manager in the Government Information Office or as a correspondent for the public broadcaster in foreign countries or in the Brussels administration, and the cycle continues. In their “bumblebee-like flight,” it is never clear what these individuals truly are – activists, media creators, politicians, PR professionals, influencers, or a blend of all, creating an incredibly eclectic mishmash.

In Slovenia, it has long been a widespread practice to appoint a CEO (=director) of a public institute in primary and / or secondary education from among the teachers in the collective. Similarly, in universities or faculties, a full professor is typically selected for the position of rector, prorector, dean, or vice dean. In hospitals, a doctor is chosen, and in cultural institutions such as theatre or museums, an artist may be selected, and so on. In the media, a journalist is chosen, but almost never a professional manager. The consequences of this paradigm have not been absent: the sector, unlike the economy, is managed in an extremely amateurish and unskilled manner. It is well-known that in this field, the rule is: when the organization fails, improvisation begins. The best evidence for this claim is that, from the liberation in 1991 until today, not a single manager from the Third sector has received the “Manager of the Year” award given by the professional association of managers in Slovenia. This award has always been won by managers from the business or public administration sectors.

It seems evident that there is a clear imbalance between the rights and responsibilities of the members of the governing bodies of public institutes because no one is held accountable for anything, except the CEO, who is the sole responsible person but only for the legality of operations, not for its success. Everyone has certain rights, but not obligations. Such a situation is highly risky due to the potential for misuse. Namely, people who haven’t invested a single cent of capital in the public institute are deciding its fate, and, above all, they do not personally financially bear the consequences for any potential harm caused to the institute by their amateurish or deliberate wrong decisions. Moreover, it is widespread for members of the Public Institute Council to prioritize their selfish personal interests or the partial interests of their ideological-political options above the overall public interest of the institute as a whole.

It is indicative that in the current state, none of the governing bodies in institutes is responsible for addressing CSR and business ethics issues. Members and presidents of the Councils are primarily concerned with satisfying their political patrons and/or powerful figures from the deep state, rather than genuinely caring (not just declaratively) about the CSR agenda, business ethics in general, and environmental, civil society, and green innovation issues. The role of an Ethical Officer, who would systematically address such issues, is not legally mandated and does not appear in the everyday life of public institutes. This has the immediate consequence of a weak practice, where NGOs are not at the necessary distance from the government, making them unable to be a critical self-awareness of a post-modern democratic society. Instead, they become either a mere transmission of the political subsystem (as was the case in the past[ii]) or an illegitimate participant in a radically left-oriented government, lacking legitimacy as it was not elected in free elections (as has been the case recently).

Now we have come to a phenomenon that requires further explanation. We are talking about cliques as a specific paradigm of corporate culture that denotes the creation of closed groups within a non-profit organization. These groups have their specific interests, values, or goals, and often develop internal hierarchies, rules, and norms that may be separate from the formal rules and procedures set by the NGO itself. Such dynamics can have various implications, both positive and negative, on corporate culture and the overall functioning of the organization. In Slovenia, it is a common practice for a prominent intellectual or influencer, together with their clique, to establish the public institute (requiring no founding capital) with the aim of obtaining funds from the state budget, sponsors/donors, and various EU funds. These funds might be inaccessible to them as individuals, that is, natural persons, but not as a legal entity. One of the negative consequences of this approach is the phenomenon of substituting institutional relationships with intersubjective relationships within the horizon of the non-profit sector in Slovenia. This substitution is directly responsible for distorting the patterns and rules of CGC in NGOs, where the mindset often becomes “we” (=our clique) is here to enjoy and benefit, rather than to fulfil what the mission and business policy of the institution require from us, as we are just one part of it and nothing more.

In practice, the seductive taxonomy becomes apparent, especially if one holds the commonplace belief that “Nomen est omen” (The name is a sign). The terminology in the Act on Public Institutes related to governing bodies is quite seductive. It implies that the Council of the public institute, as the highest governing body, has the right to confirm and/or advise other bodies, “gives opinions and proposals,” rather than govern the public institute directly. In practice, this can take the form of either repressive tolerance or complete impotence or a combination of both, which is often the case.

It is useful to note in this discourse the composition of the Institute Council as a tripartite body. As established earlier, the Council’s mandatory composition consists of three delegations: 1) representatives of the founder, 2) representatives of the public institute’s employees, and 3) representatives of users or the interested public. Consequently, practical problems typical of any triumvirate since Roman times will always arise. One option is to regulate it by the public institute’s Statute in such a way that the founder/s have an absolute majority, in which case the very essence of the tripartite nature of that body is nullified, as the other two stakeholders (employees and the interested public) become mere decorations, having no real decision-making power. Another option is to structure the Council’s composition in the spirit of democracy so that all three delegations have an equal number of members from their ranks. This leads to an open battle for the creation of majority in Council which will reach the power. Another option is to create an unprincipled coalition of two delegations against the third, as two are always stronger than one: “Two bad, Miloš dead”, asserts one of well-known commonplace on this issue. In this case, if a coalition is formed between employees and the interested public, there is a real risk of them taking over the public institute from the founder and de facto made it private. Except for dissolving the public institute or withdrawing from it, the founder has no other solution, which is weak because it may affect the decline of their reputation and good standing in the public eye. In summary, the legal solution is weak as it leaves behind only negative consequences in the practice of corporate governance in the non-profit sector. Therefore, it is necessary to replace it with contemporary solutions, for which, currently, there seems to be no political will.

The so-called “self-management” control is another phenomenon that we must not overlook in our findings. The presence of employees in the highest governing body of the public institute means that they have the opportunity to control themselves. This not only exemplifies weak self-management practices from the former system, which failed precisely because of this, but also represents an obvious conflict of roles and interests. If a GCG system is established in the public institute, the same person should not serve as both the controller and the controlled. These are two distinct roles with divergent interests, and their syncretism creates various “monsters”.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. Suppose the head of marketing, head of finance, or head of accounting becomes a member of the Public Institute Council from the ranks of employees, automatically becoming the supervisor of the CEO, instead of the other way around, where the CEO directs and controls their operations. In the extreme case, they may desire and have the ability to remove the director who scrutinizes them too closely, just as the director may wish to dismiss them from their positions, thereby terminating their mandate as Council members and marking the end of their power over him.

However, such state of affairs creates a schizophrenic situation, an unbearable tension that usually leads to an irresolvable conflict resulting in weak corporate governance practices. Additionally, the CEO needs to have a “friendly” Public Institute Council, as any other scenario creates an impossible situation where someone has to leave – there is a higher probability that it will be the CEO rather than the entire Council. Therefore, all institute directors in Slovenia strive to have their friends, ideological-political like-minded individuals, schoolmates, godparents, acquaintances, or friends of friends elected to the Council. These could be individuals who owe them something or even intimate partners (with different last names to avoid obviousness at first glance). By doing so, they secure a governing body that won’t hinder them from doing what they want, rendering the so-called two-tier administration virtually meaningless.

The management of NGOs in Slovenija is still not sufficiently committed to establishing and measuring received financial resources based on their non-financial performance. However, it should be at the forefront in the fight to transition to a low-carbon and more inclusive economy. In doing so, they should express less concern about ’greenwashing’ and more about the fact that it is not only the task of environmental NGOs to be involved in preserving the human environment, but actually all of them without exception. Therefore, the main concern of the Boards of Directors of NGOs should be to conduct a critical review of the situation in this regard by adopting the classification, analysis, and assessment of current sustainability measurement methods already used by investment funds from the industry and academic community. Such evaluation is based on a matrix of seven criteria developed based on gaps identified in academic papers and reports of international organizations. After careful evaluation, Popescu and colleagues (2021) discovered “that carbon footprints and exposure metrics and environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings, while widely used, have several shortcomings, failing to capture the real-world sustainability impact of investments” (Popescu, Hitaj, and Benetto 2021, 1). Based on this insight, they proposed that in the future, “open-source, science-based and sustainability-driven assessment methods’ become priority assessment methods, which can be upgraded ’by incorporating measurement of positive impact creation and by adopting a life cycle perspective” (Popescu, Hitaj, and Benetto 2021, 1). Considering the need for sustainability assessments by NGO leadership to be directed towards reality, the compatibility of their outputs (products or services) with scientifically based sustainable development goals should become a central element both in their daily practice and reporting, which is currently not the case.

The legal (dis)culture best exemplified by the slogan - “We have the right to enemies because we will agree among ourselves” (regardless of applicable legal norms) - is a predominant paradigm inherited from the period of self-management socialism in the Third sector and still prevails today. Here, perhaps, it can be seen most clearly that every form of self-regulation is contextually conditioned, depending above all on the level of culture achieved by the population. Thus, for example, the non-profit sector in Europe has gone through a long evolution (Bies, 2010), which today allows actors on the civil-society scene, according to our opinion, a much higher degree of self-regulation than those who lived in authoritarian-totalitarian regimes. Although Slovenia was part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy for several centuries, which was, at least in the last period of its existence, a “rule of law,” and spent only 46 years in the communism of the former Yugoslavia, the influence on shaping corporate culture has proven to be more powerful, although not completely dominant. Slovenia has become a kind of bridge halfway between Central Europe and the Balkans, so it does not fit purely into the “Catholic zone” as a newcomer from the former “communist zone” according to Inglehart (Inglehart and Welzel 2005, 2023), but is a cultural “cocktail” mixed from elements of communist collectivism, Protestant work ethic, Catholic sense of community solidarity, communist atheism, and hedonism. This blend seriously complicates the moral and professional functioning of members of governing bodies, not only in the Third sector but also in the first and second sectors. In this context, Slovenia is still waiting for the real onset of the post-socialist transition process. At this moment, there is nothing to suggest that this will happen anytime soon.

5. Discussion

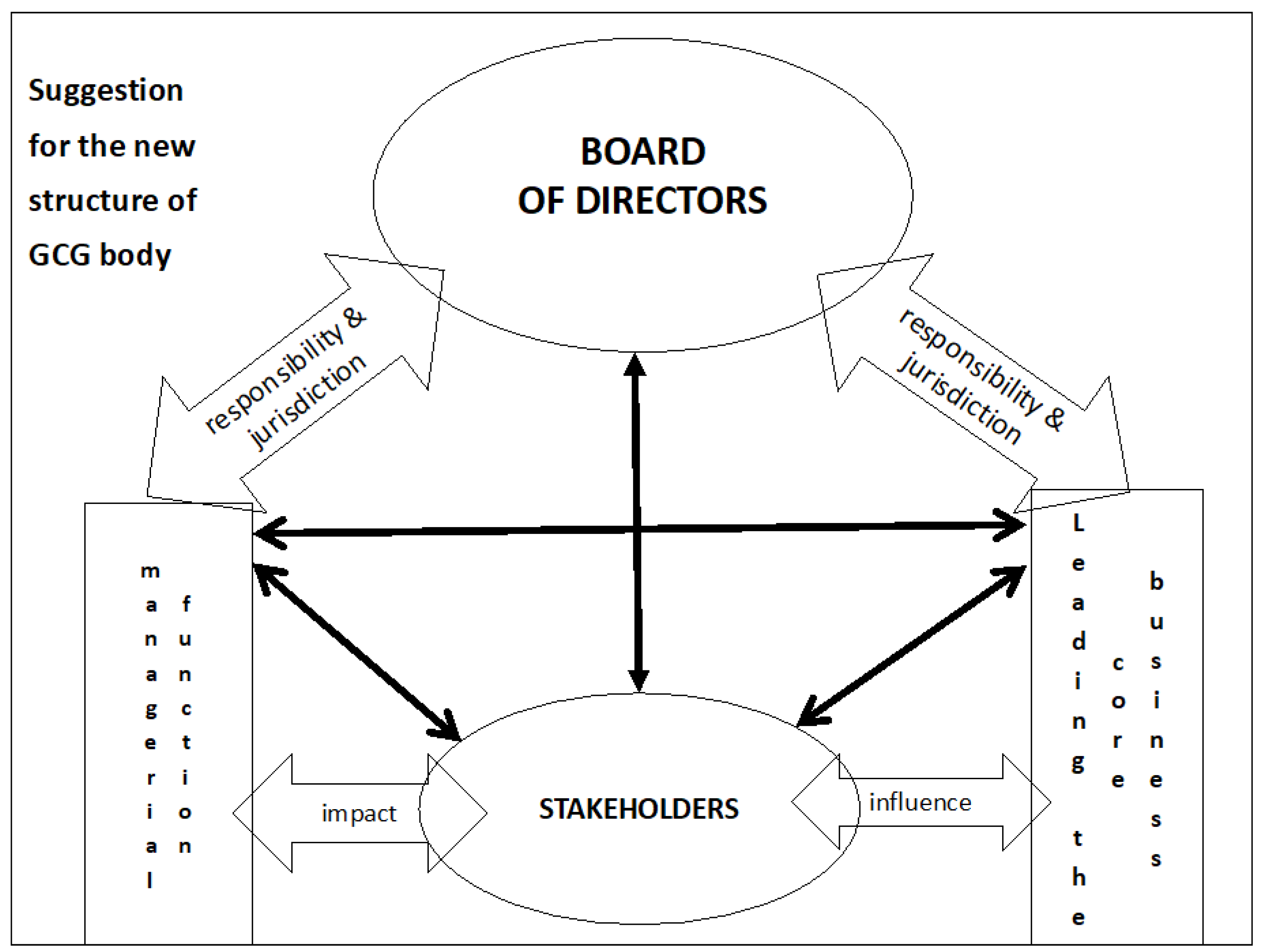

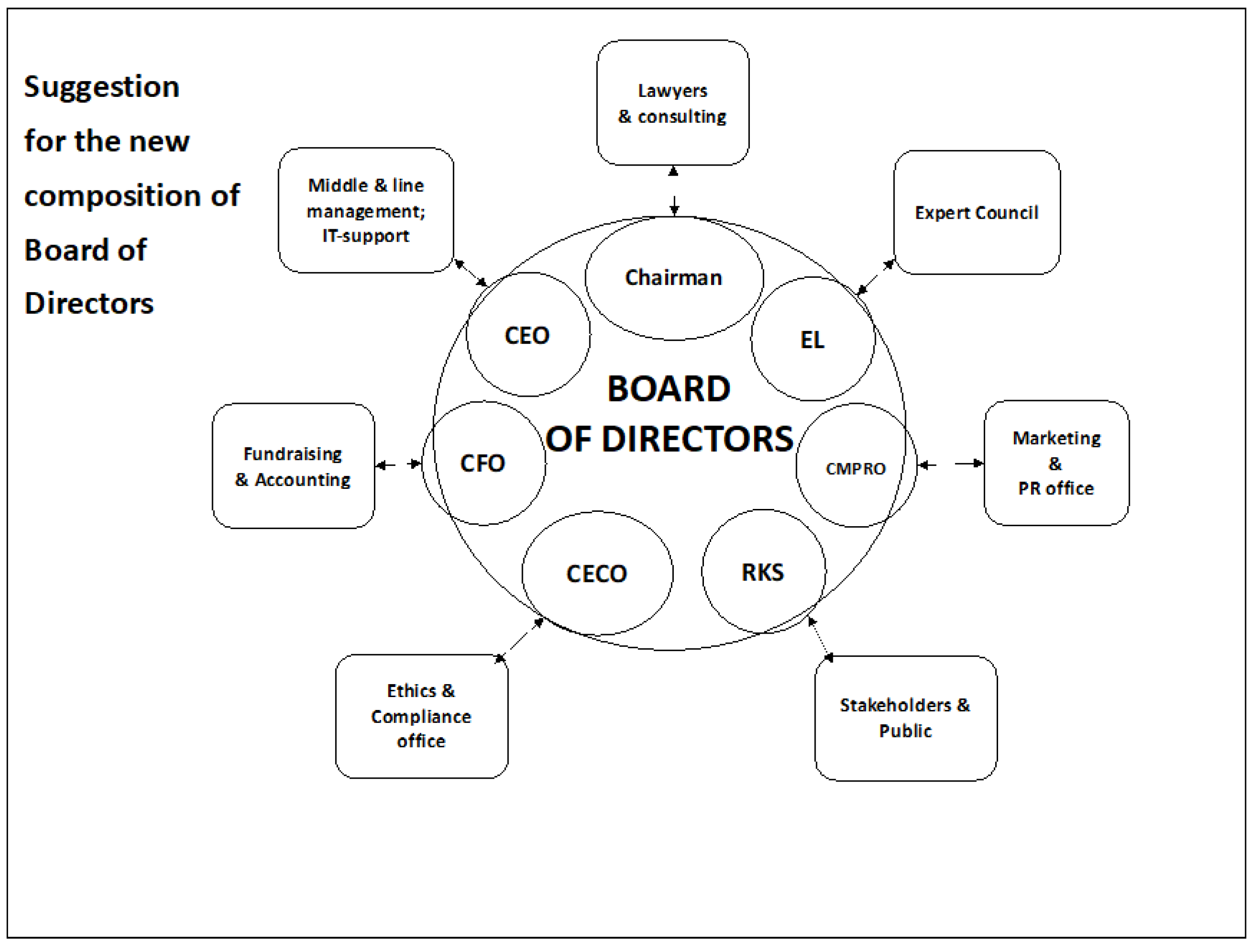

If the decision-making factors within the political subsystem and stakeholders of civil society were to gain the political will in the future to incorporate corporate governance with the intention of adapting to the spirit of the times and providing a more adequate response to its challenges and pitfalls, they will need to contemplate primarily the business-moral, responsible-sustainable, and green agenda. For such an opportunity, it might be welcome to consider the content of our undertaking in this article. In our opinion, the sequence of events will then be very simple: ’first the small stable, then the little cow,’ which essentially means that one should start primarily with changing the current legal framework to achieve a new legal-organizational arrangement of corporate governance, stemming from an attempt to eliminate all the aforementioned shortcomings of the controversial state of affairs in this area, before moving on to the more challenging task – gradually and painstakingly changing outdated and entrenched patterns of corporate governance and management culture. In our assessment, establishing effective single-track administration instead of the current dual-track represents a necessary precondition for any meaningful change. In that case, the public institute would have only one centralized GCG body, which instead of a Council would be called by its proper name - the Board of Directors, composed of: 1. The Chairman of Board, 2. CEO, 3. Professional Leader, 4. CFO (Chief Financial Officer), 5. CMPRO (Chief Marketing and PR Officer), 6. CECO (Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer), and 7. RKS (Representative of key stakeholders).

According to our proposal for changes to CG of NGOs in Slovenia, the most crucial aspect is related to the current Council as the main governing body in the Public Institute. In the future, GCG in the public institute would be executed through a

single-track process with the assistance of a unified collegial administration, management and leadership body consisting of seven members responsible for overseeing various processes in the non-for-profit core activities of the institute and potential supplementary for-profit activities aimed at generating funds for the realization of their mission. Each of them would be associated with an advisory body and/or organizational unit, department, or function, which, with its competencies, would assist them in fulfilling their role in the successful GCG of the public institute (see

Figure 2 below). In doing so, we agree with the arguments of those authors who “reveals that tenure, ideology and educational level (gender and nationality) predominantly appear to drive a firm’s CSR within one (two)-tier boards settings” with the difference that we give priority to the first (Jouber 2021).

According to the new paradigm in non-Western context, the key responsibilities and authorities of the members of the Board of Directors should be:

Ad 1) Chairman of the Board: The Chairman should act as primus inter pares; he/she is the President of the public institute and simultaneously the responsible person representing the institute in legal transactions.

Ad 2) CEO: Among other responsibilities, the Chief Executive Officer ensures harmonious collaboration and communication among all internal organizational units, departments, functions, and individuals in achieving the purpose for which the public institute was founded, both internally and with external stakeholders. This especially relates to the business ethical agenda and the management of active corporate citizenship and sustainability, as well as environmental, civil society, and green innovation issues.

Ad 3) Professional Leader: This individual is an expert manager in the field of the public institute’s basic activities. Their primary function is to lead the professional work in the institute and represent the interests and needs of employees in the core activities of the institute on the Board.

Ad 4) CFO: Among other responsibilities, the Chief Financial Officer is in charge of diversifying funding sources, fundraising for the institute, ensuring a systematic and regular flow of sufficient financial resources needed for its normal operations.

Ad 5) Chief Marketing and PR Officer: Responsible for maintaining the institute’s reputation, successful communication with the public, and efficient sales of its products or services in the market.

Ad 6) Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer: Serves as the organization’s internal control point for ethics and improprieties, handling allegations, complaints, and conflicts of interest. Provides corporate leadership and advice on GCG issues within the framework of CSR, business morality, environmental, civil society, and green innovation. Manages corporate citizenship and sustainability in the Age of Trans-Modern-Transition[iii]. With compliance, the boundary is defined by law, rules, regulations, or policies, and adherence is mandatory. Ethics involves judgment and making choices about conduct that reflects values, aiming to achieve best practices of honourable behaviour that builds trust among stakeholders and the public, including integrity, impartiality, transparency, honesty, reliability, loyalty, and credibility.

Similarly, since cliques (as we already seen above) are a common occurrence in corporate culture in Slovenia, as well as in other countries of the former communist bloc, non-profit or non-governmental organizations aiming to create a positive and inclusive work environment should be aware of the potential negative impacts of cliques and take steps to prevent them. Actively preventing the organization from splitting into formal and informal subsystems inevitably establishes a clique-driven corporate culture where cliques compete for dominance. In this context, it is undoubtedly a continuous task for all members of the Board of the public institute to actively prevent “cliquish” behaviour, as they should be the first to be aware of its potential risks and the necessity to consistently and permanently take steps to reduce them an acceptable level and, in the last consequence, prevent the detrimental influence of cliques on corporate culture. Some of the steps they could take include: (i) promoting diversity and inclusion: this reduces the likelihood of cliques based on personal characteristics or position in the organization; (ii) promoting transparency, open communication, and collaboration among all employees and other key stakeholders of the public institute: this reduces the likelihood of conflict and discrimination between different cliques; (iii) setting clear expectations: this prevents or at least reduces the likelihood of corruption and other negative behaviors that may occur within cliques; (iv) emphasizing the importance of moral values and norms such as honesty, integrity, impartiality, credibility, loyalty, reliability, transparency, and dignity: this reduces the influence of cliques on the institute’s corporate culture; (v) appointing responsible individuals: designate the CEO and CECO as individuals primarily responsible for resolving conflicts arising from cliques; (vi) training employees on the impact of cliques on corporate culture: NGOs should educate and train employees & volunteers on the dangers and negative aspects of cliques, how to recognize them, and how to reduce them to a manageable level.

Ad 7) Representative of key stakeholders: This role plays a special part in registering and understanding conflicting interests, desires, and intentions of different stakeholders of the public institute in order to effectively balance them.

The enduring responsibility of the Board of Directors as a whole should be to:

1) Establish and foster an entrepreneurial spirit and transformational leadership (Bass and Riggio 2006): this involves promoting a culture that encourages innovation and dynamic leadership in response to urgent problems, as well as planning for the future (Authors 2012).

2) Transform the prevailing clan-type organizational culture in the corporate culture of the Adhocracy which includes: (i) management that “responds to urgent problems rather than planning to avoid them” (Dictionary.com); (ii) dealing with what is always ad hoc, „implying something temporary, specialized, and dynamic.“ (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 49); (iii) recognizing that GCG in a hyper-turbulent world must resort to innovative and pioneering initiatives, developing new products and services to meet the future with an entrepreneurial spirit, creativity, and activity on the cutting edge (Cameron and Quinn 2011); (iv) this new cultural paradigm is characterized by orienting the organization towards creativity, demanding that its leaders be innovators, entrepreneurs, and visionaries. The theory of efficiency, relying on innovation, vision, and new resources that bring transformation, innovative outputs and agility, guides them in practice (Cameron and Quinn 2011). This is particularly challenging given that metamorphosis of deeply rooted patterns of retrograde behavior in individuals and groups in the Third Sector to overcome the past and achieve current exemplary Western models of successful business will be a tough nut to crack for the Boards[iv].

3)

Influence the reduction of established governance incongruence: The Board of Directors, through its activities, impacts the reduction of

governance incongruence as it creates dissonance, which poses a serious hazard to successful corporate governance. To avoid dissonance between words and actions, decisions and outcomes, a relationship of

highly correlated consistency must be established and maintained (see

Figure 3).

4) To incorporate social entrepreneurship into the public institute’s operations to the greatest extent possible because the principles of social economy align best with the non-for-profit nature of NGOs. The primary goal of the entrepreneurial spirit is to enable the advancement of societal well-being by offering a market response to problems pertaining to social, environmental, local, and other issues. It becomes commonplace that social entrepreneurship is a kind of business in which achieving social goals and giving back to the community come first. Its priority are social goals, values, and mission over financial advantages, in contrast to traditional entrepreneurship. This is in line with the main objective of all NGOs, which is to refocus attention away from profit and towards: (i) addressing social issues and challenges (such as unemployment, poverty, social exclusion, environmental issues, health disparities, and others); (ii) improving the quality of life (especially for vulnerable communities and individuals, ensuring access to basic goods, services, and opportunities for all); (iii) Creating social value through the improvement of social capital, reinvestment of profits into the community, funding of social program, and enhancement of people’s quality of life; (iv) Social inclusion, especially for marginalized and vulnerable groups such as the homeless, immigrants, people with disabilities, and long-term unemployed; (v) Sustainable development, encompassing social justice, environmental sustainability, long-term economic stability, corporate social responsibility, morality, and green initiative issues, among other things.

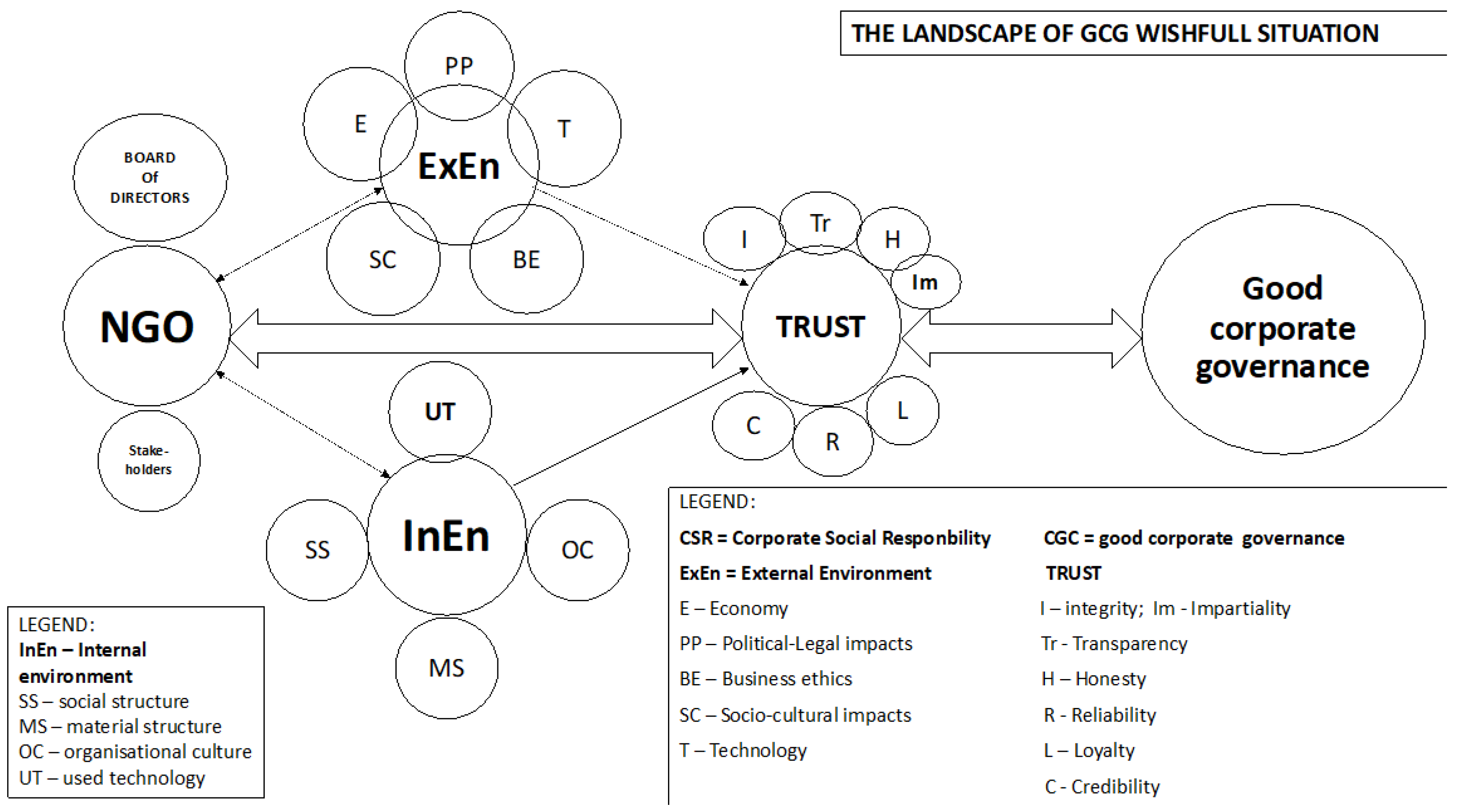

In

Figure 4, we presented the conceptual model of the new western oriented paradigm of GCG in non-western context, synthesizing all key latent constructs from this perspective of GCG in framework of NGOs. In such model, the main dependent (outcome) variable is GCG, while the independent variable is the NGO’s Board of Directors with their specific demographic characteristics. As a

moderator influencing the basic correlations between variables, the external and internal environment (ExEn & InEn) come into play, while

trust acts as a

mediator with its CSR agenda. We hold that by doing this, we have adequately addressed our cardinal research question (RQ

1). Hence nothing prevents us from spending further time working on this article’s

theoretical and practical implications.

It is a right place to summarize the answer to RQ1 in the form of synthetic propositions based on all those partial answers that have already been given in sections 4, 5 and 6 of present article. By this means, we have reached the position where we can, for the last time in this article, reflect on our fundamental research question RQ1 on key aspects of GCG to achieve the proper type of leadership by governance bodies in the context of non-Western non-profit organizations. Although we believe that we have satisfactorily answered it till now, it won’t hurt to approach it in the form of synthetic concluding propositions, namely, theorems (hereinafter: T) and their corollaries (hereinafter: C). So, let’s proceed in order.

T1: GCG of Third Sector in the non-Western context is still insufficiently developed in relation to comparable Western countries in the EU.

C1: The causes of the above-established state of affairs and spirit of mind should primarily be sought in the fact that the sector itself is a neglected and overlooked field.

Proof of T1: Let’s mention at least key indicators that clearly demonstrate the marginalization of the Third Sector in Slovenia: (i) 92.17% of NGOs have no regularly employed staff, so the entire sector employs an average of 0.48% of the employed in NGOs; out of approximately 900,000 employed in Slovenia, only 12,500 have found employment in NGOs, representing a mere 0.14%; (ii) Regarding the annual income of NGOs, 89.38% generate less than €50,000, while 1/5 (=19.25%) have no income at all. The total revenue of NGOs accounts for a modest 2.10% of the Slovenian GDP, while the EU average is twice as high. In such circumstances, the intention of professionals in the field of management and leadership to seek employment in NGOs cannot be expected, resulting in the sector being mainly managed by volunteers who are amateurs and enthusiasts; (iii) Most NGOs rely on state budgets and donations/sponsorships instead of independently earning financial resources for their existence and development, for example, in the form of social entrepreneurship, the green economy, circular economy, and so on; (iv) The Slovenian state allocates less than 1% of its budget to support the activities of NGOs (=0,97%), while the EU average is twice as high (=2.20%).

T2: The marginalization and/or self-marginalization of the Third Sector in the Age of post-socialist transition has a strong positive correlation with deficient management and corporate governance in NGOs.

C2: Consequently, such a state of affairs and spirit of mind particularly relates to managerial inconsistency when not considering the perspective of CSR, business ethics and the green economy agenda.

Proof of T2: No NGO has an “ethical office” and/or a “chief ethical officer,” only a few have business ethics codes, and everything else we have proposed that must be changed if there is political will and the will of actors in the civil society to lift the Third Sector out of the lethargy it is currently in. In the process of demarginalization, a mere change in the outdated legal framework will not be sufficient; a radical metamorphosis of inadequate patterns of the currently dominant corporate culture that hinders the transition to postmodern GCG is needed.

T3: Smart, timely and responsible GCG, if it relays on the CSR, business ethics, and green innovation agenda within their frames, implementation of the proposed conceptual model could be useful in building highly professional and sustainable corporate culture.

C3: The above concept of GCG implemented in this way ought to lead to the building and maintaining of NGOs excellence trough trust and reputation.

C3.1: The prerequisite for something like this will be the previous elimination of the deficiencies that we defined using propositions P1-P14 (see subsection 3.2 above) while simultaneously implementing the necessary changes in the legal status of NGOs as well as their corporate culture that we proposed in sections 5 & 6.

C3.1.1: NGOs should be at the forefront in the fight to transition to a low-carbon and more inclusive economy; in doing so, they should express less concern about ’greenwashing’ and more about the fact that it is not only the task of environmental NGOs to be involved in preserving the human environment, green innovations and societies without the use of fossil fuels but actually all of them without exception.

C3.1.1.1: Only if it goes in the direction described above, then GCG in the non-profit sector opens up a great potential of real opportunities for rapid development in the future, despite the current situation, which we cannot assess as satisfactory.

Proof of T3: The above proposed conceptual model (see

Figure 4), as a result of analysis and critical reflection on previous research, can be the basis for further research in the domain of building GCG culture of NGOs as a mechanism for professionally and ethically accountable behaviour of Actors which building of