1. Introduction

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC), the most common histological type of epithelial ovarian cancer, is often diagnosed at an advanced stage and is associated with a high risk of recurrence and a poor prognosis. In cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant treatment for advanced cancer, R0 (complete resection) or optimal surgery (residual tumor less than 1 cm gross) may improve prognosis, whereas suboptimal surgery (residual tumor above 1 cm gross) is associated with poor prognosis [

1]. HGSOC can be classified into 4 molecular subtypes, immunoreactive (IR), differentiated, proliferative, and mesenchymal, identified by transcriptomic profiling [

2]. The IR subtype of HGSOC is characterized by abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the tumor microenvironment and high expression of immune-related genes, and tends to have a better prognosis compared to other subtypes [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The improved prognosis of the IR subtype may be due to higher intratumor immune activity, which helps to eliminate cancer cells more effectively; studies have shown that the IR subtype is associated with longer overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The combination of high TILs presence with R0 or optimal surgery is a favorable prognostic indicator. However, for patients who have undergone suboptimal surgery, the utility of TILs in predicting outcomes is still unclear. This study investigated the prognostic significance of intra-tumoral lymphocytes in patients treated with R0+optimal and suboptimal surgery for HGSOC.

2. Materials and Methods

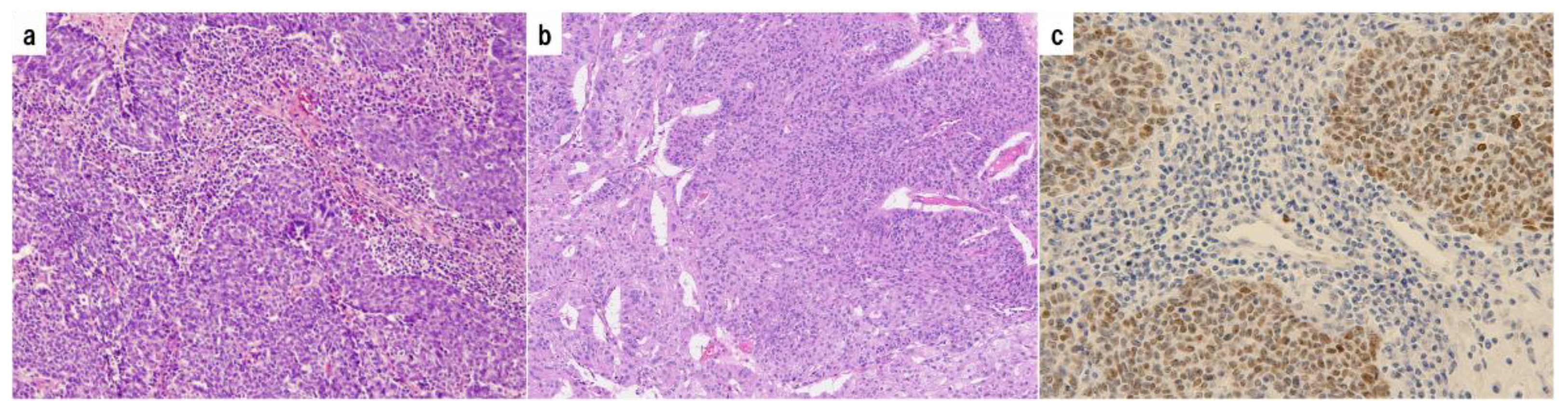

We reviewed 318 malignant ovarian tumors detected in our database between 2000 and 2017. 74 HGSOCs were selected with supplemental p53 immunostaining. Histopathological images are shown in

Figure 1. Paraffin-embedded specimens were obtained from the archives of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, and relevant clinical data were also collected for analysis. The selection of diagnostic criteria and stratification factors for HGSOC was based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) cancer report and the consensus conference recommendations of the European Society of Gynecological Oncology (ESGO), the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society of Pathology (ESP) or the GCIG (Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup) [

1,

7,

8]. The following factors were extracted from 74 cases: age at diagnosis, FIGO 2014 stage, initial surgical treatment (primary debulking surgery or interval debulking surgery), retroperitoneal lymph node sampling, initial platinum-based chemotherapy (neoadjuvant or adjuvant), CA125 level before initial treatment, residual disease after surgery (R0, optimal surgery, suboptimal surgery), recurrent treatment, architectural grade, nuclear grade, Lymphovascular space invasion, Intra-tumoral budding, p53 expression status, HGSOC histological subtypes (Immunoreactive, Differentiated, Proliferative, and Mesenchymal), Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Response to chemotherapy was defined according to RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) [

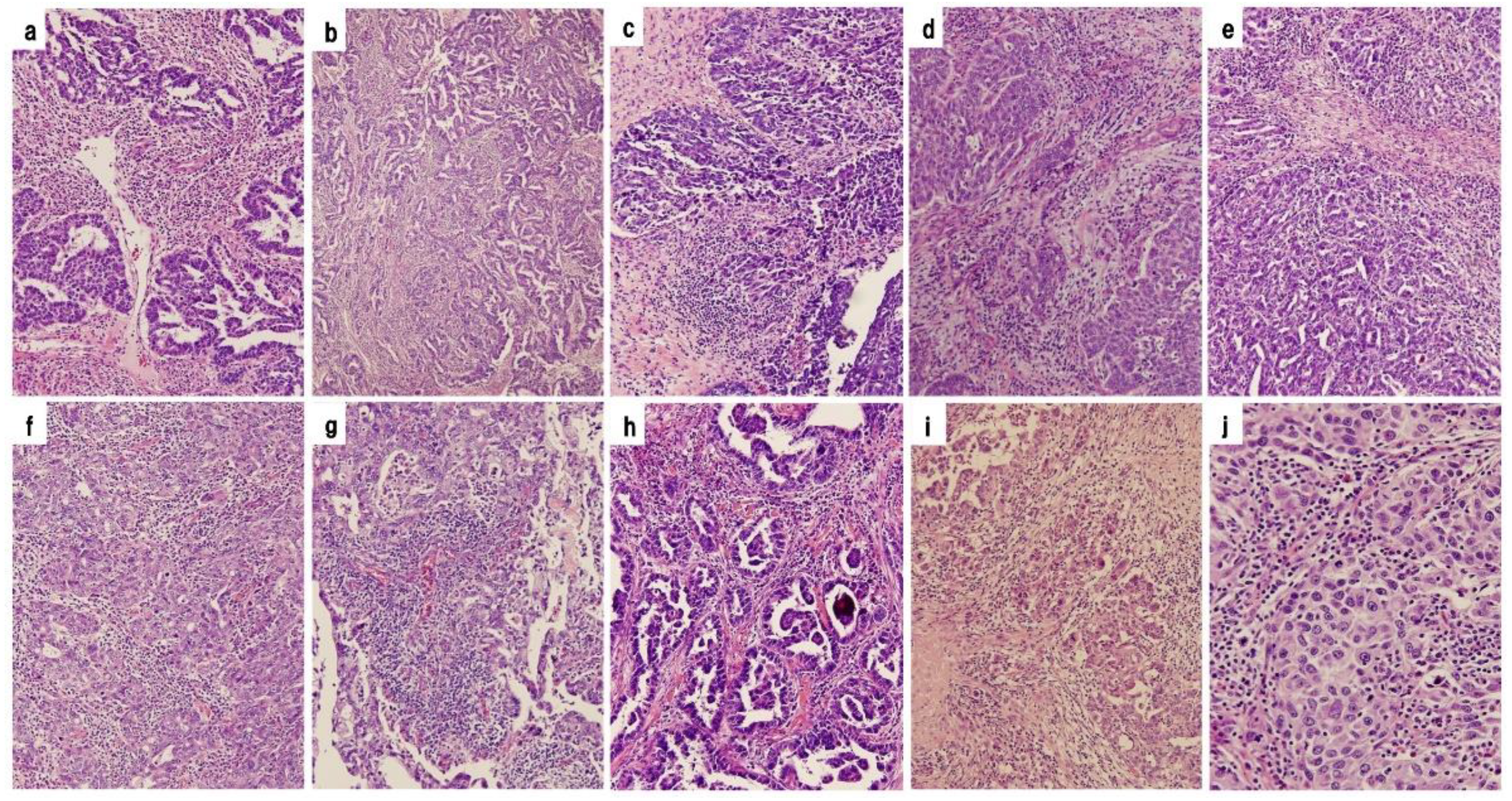

9]. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were counted for localization inside or outside cancer nests using a representative slide from each case. Based on pathological findings, HGSOCs were divided into 2 groups: those with or without abundant intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration. Differences in PFS and OS between the 2 groups of IR subtype and the other subtypes of HGSOC were investigated. Histopathological images of 10 cases diagnosed as IR subtypes are shown in

Figure 2. The group with histopathological evidence of abundant intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration was defined as High TILs (IR subtype) and the group without abundant intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration as Low TILs (the other subtypes).

74 representative formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks were selected for immunohistochemical analysis. p53 immunohistochemistry was performed using a commercially available mouse monoclonal anti-human antibody (protein clone DO-7, Dako, CA, USA) at a 1:50 dilution on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Sections were stained using the universal immunoperoxidase polymer method (Envision kit; Dako) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Antigen retrieval was then performed by microwave heating and pressure cooking. Positive and negative controls were also performed. According to the proposed immunohistochemical scoring, p53 expression was scored as overexpression or complete absence.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data on clinicopathological factors were evaluated using the chi-squared test or the Mann-Whitney U test. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of initial treatment to the date of objective disease progression or last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of initial treatment to the date of death or last follow-up. PFS and OS curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the association of potential risk factors with disease progression and death. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value of <0.05.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of the University Hospital for Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (UOEHCRB21-155). All procedures were carried out according to relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of HGSOC in 74 Cases

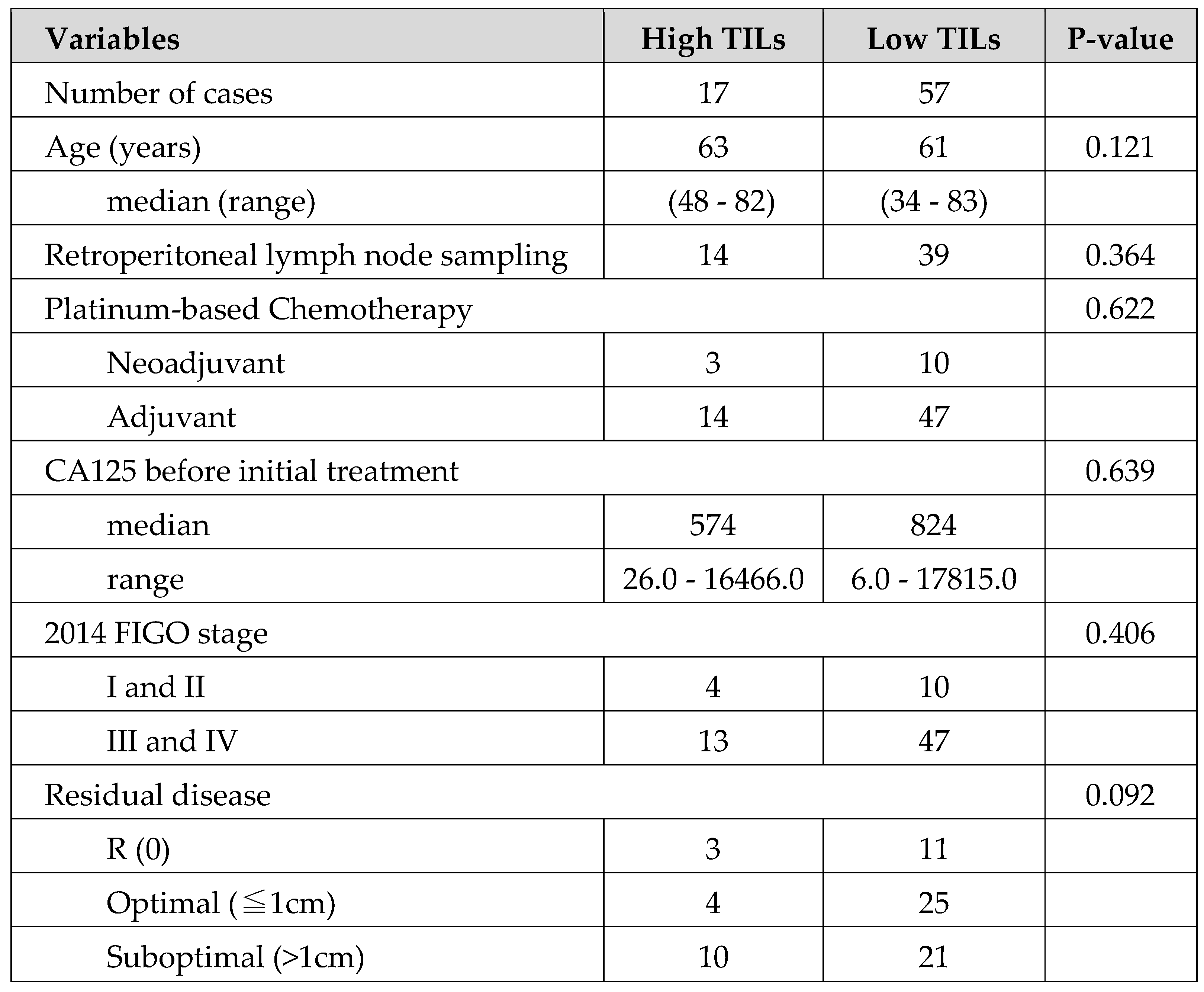

In terms of clinical background, a comparison between the 2 groups in the High or Low TILs showed no obvious significant differences, except for a significant trend in the residual tumor category in

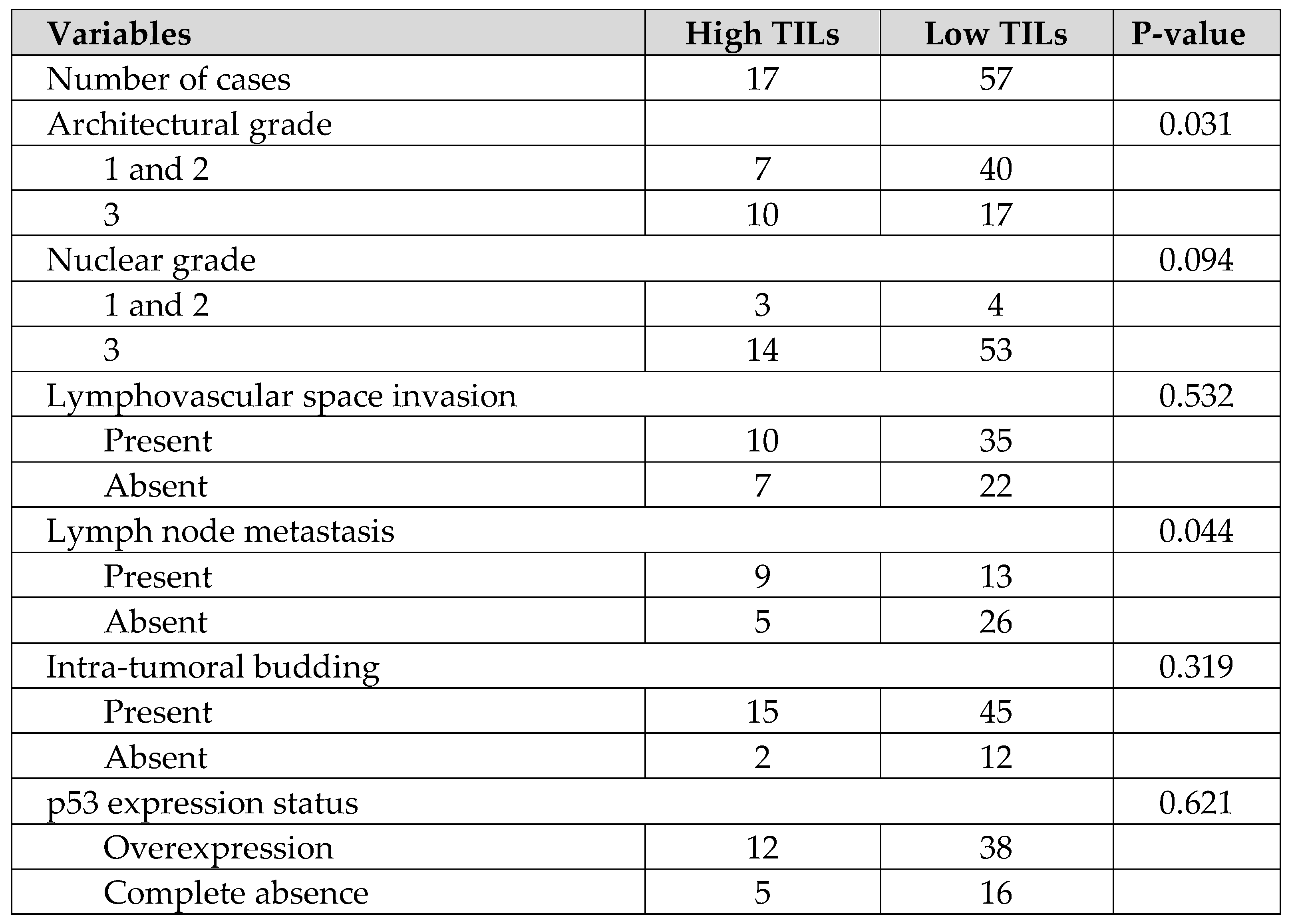

Table 1. Similar comparisons of histopathological background between the 2 groups showed that more cases with Low TILs had low-grade structural atypia and more cases with negative lymph node metastasis, and there were no obvious significant differences in the other parameters in

Table 2. Although the authors have previously reported on intra-tumoral budding and prognosis in HGSOC, no correlation between intra-tumoral budding and TILs was found in the current study [

10].

3.2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve and Analysis(High TILs Versus Low TILs)

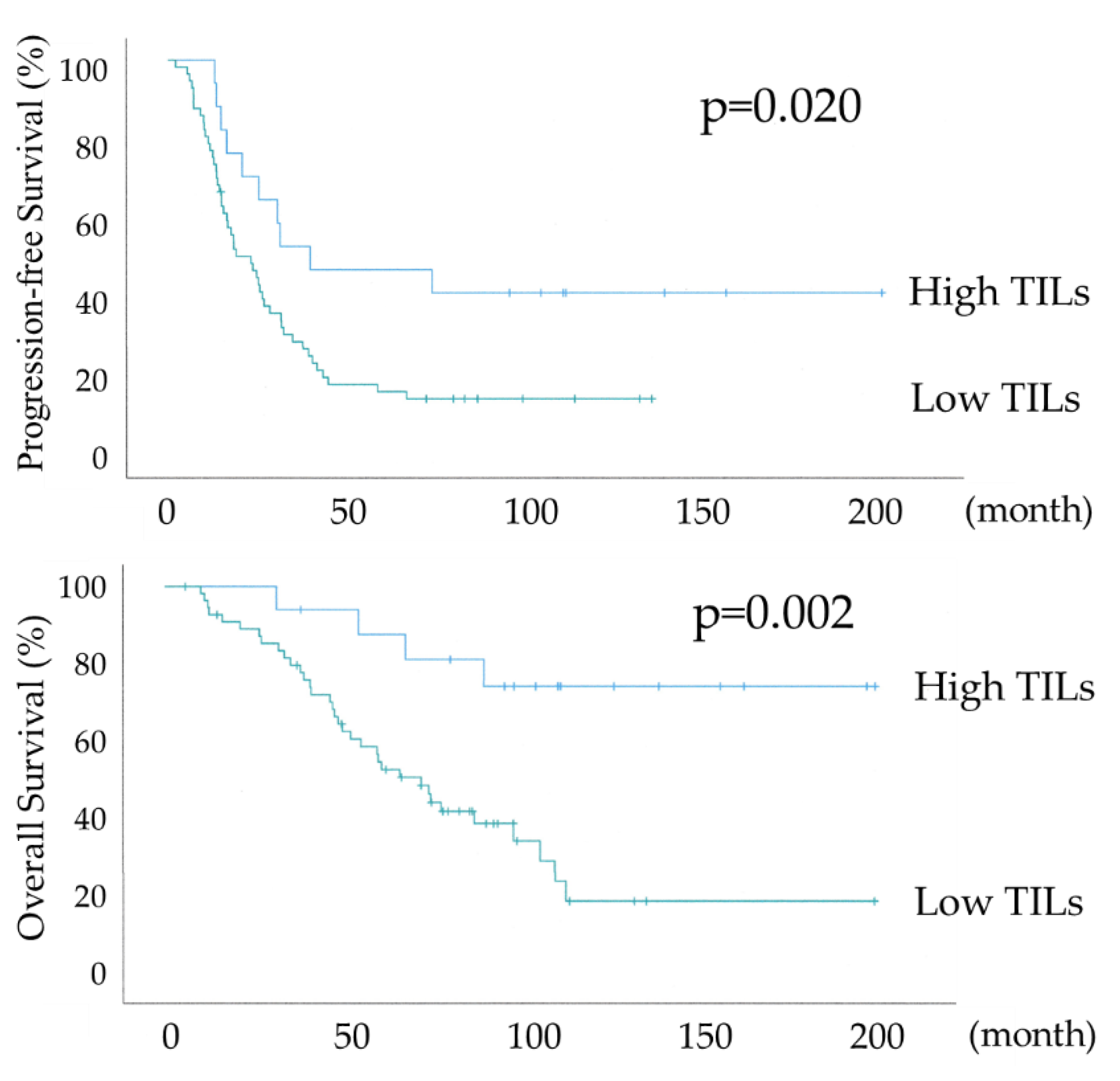

Figure 3 shows the differential Kaplan-Meier PFS and OS curves in all 74 HGSOC cases for the High or Low TILs. The median PFS was 38 months (range 28-93) in 17 patients with HGSOC with High TILs and 22 months (range 15-28) in 57 women with HGSOC with Low TILs, and their median OS was not available and 68 months (range 49-86). Both PFS and OS were significantly prolonged in the High TILs group (P-values =0.020 and =0.002, respectively), with an overall survival of >70% at 120 months in the High TILs group.

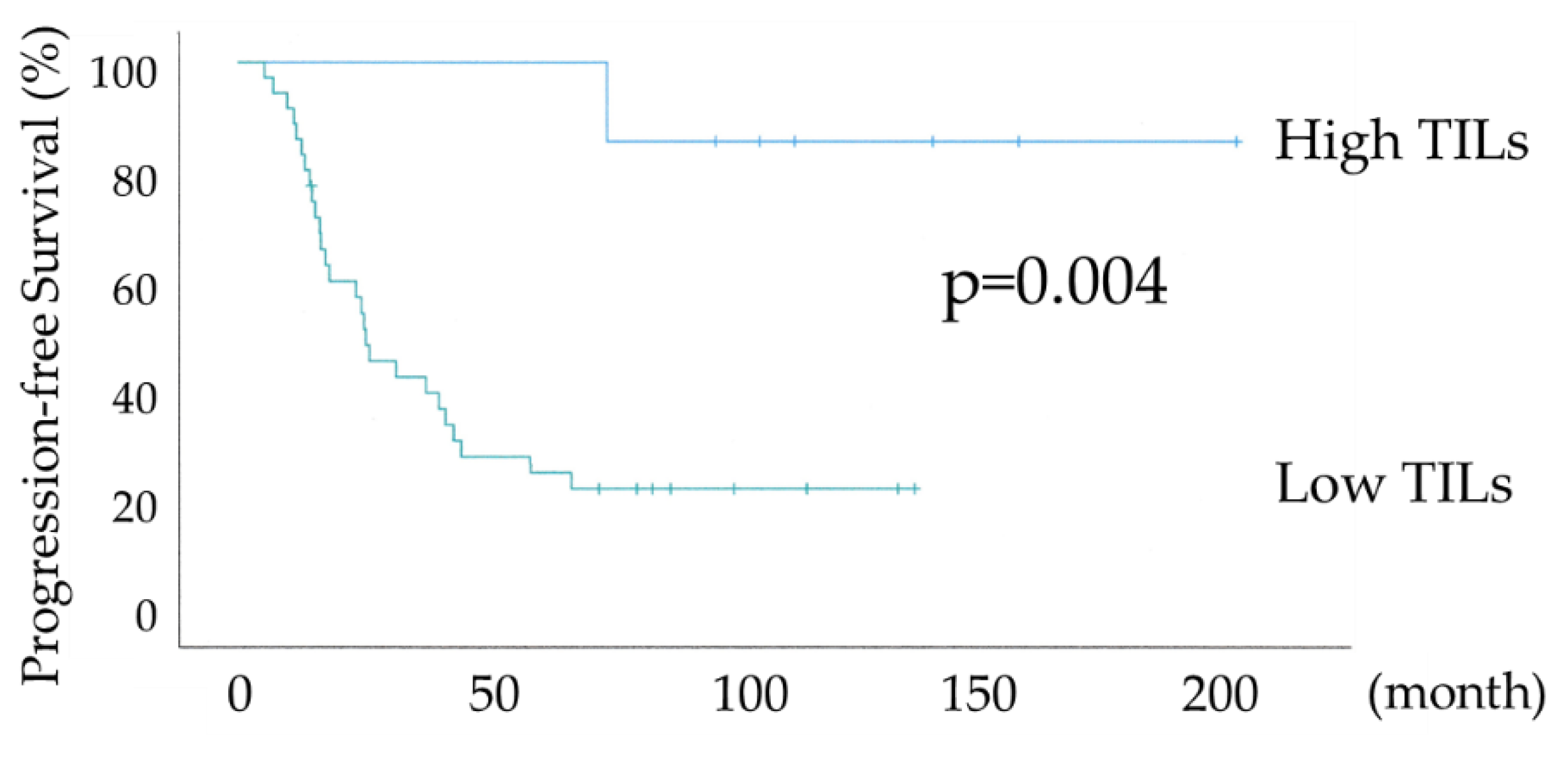

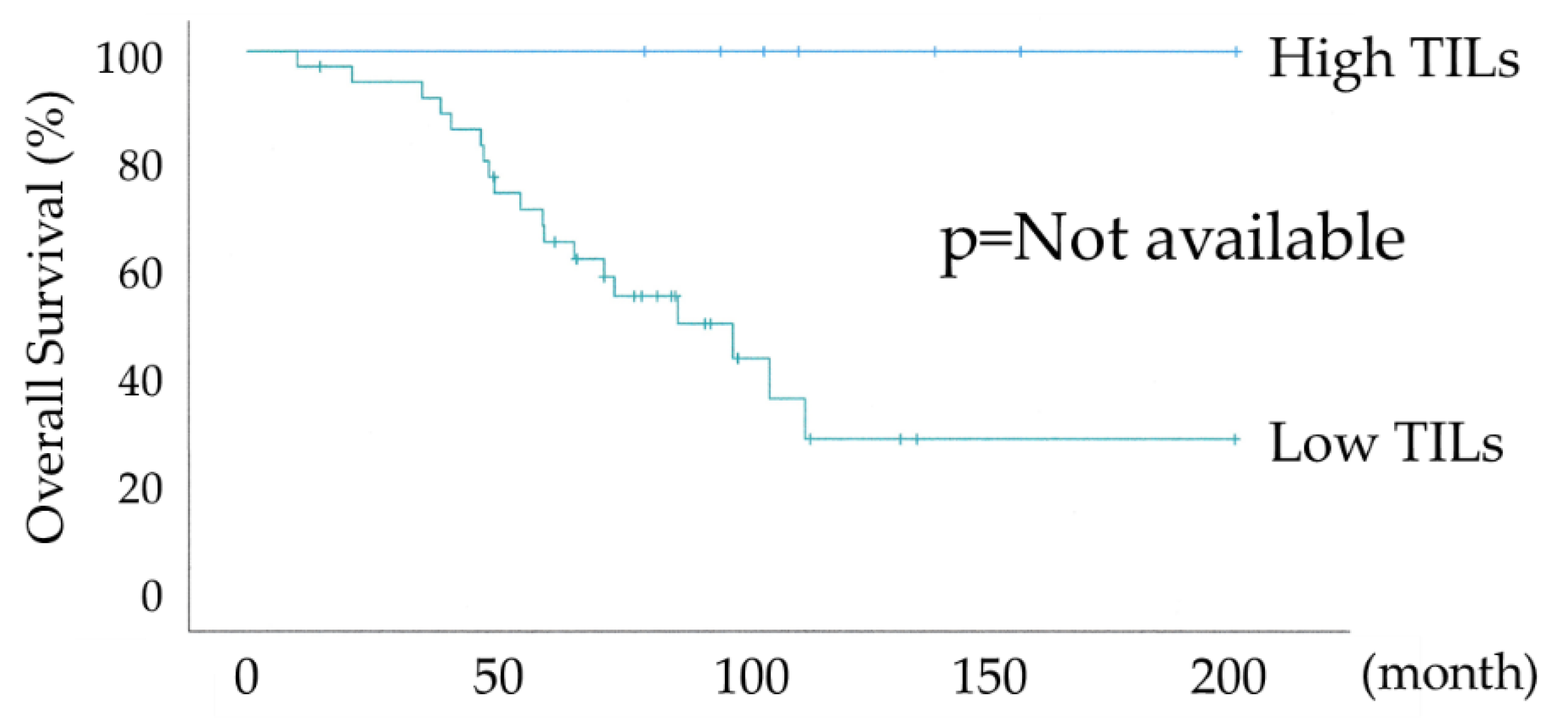

Figure 4 shows the differential Kaplan–Meier PFS and OS curves in c for the High or Low TILs. The median PFS was not available in 7 patients with HGSOC with High TILs and 24 months (range 15-32) in 36 women with HGSOC with Low TILs. Both PFS and OS were significantly prolonged in the High TILs group (P-values =0.004 and not available, respectively). The High TILs group had >80% PFS and 100% OS at 120 months.

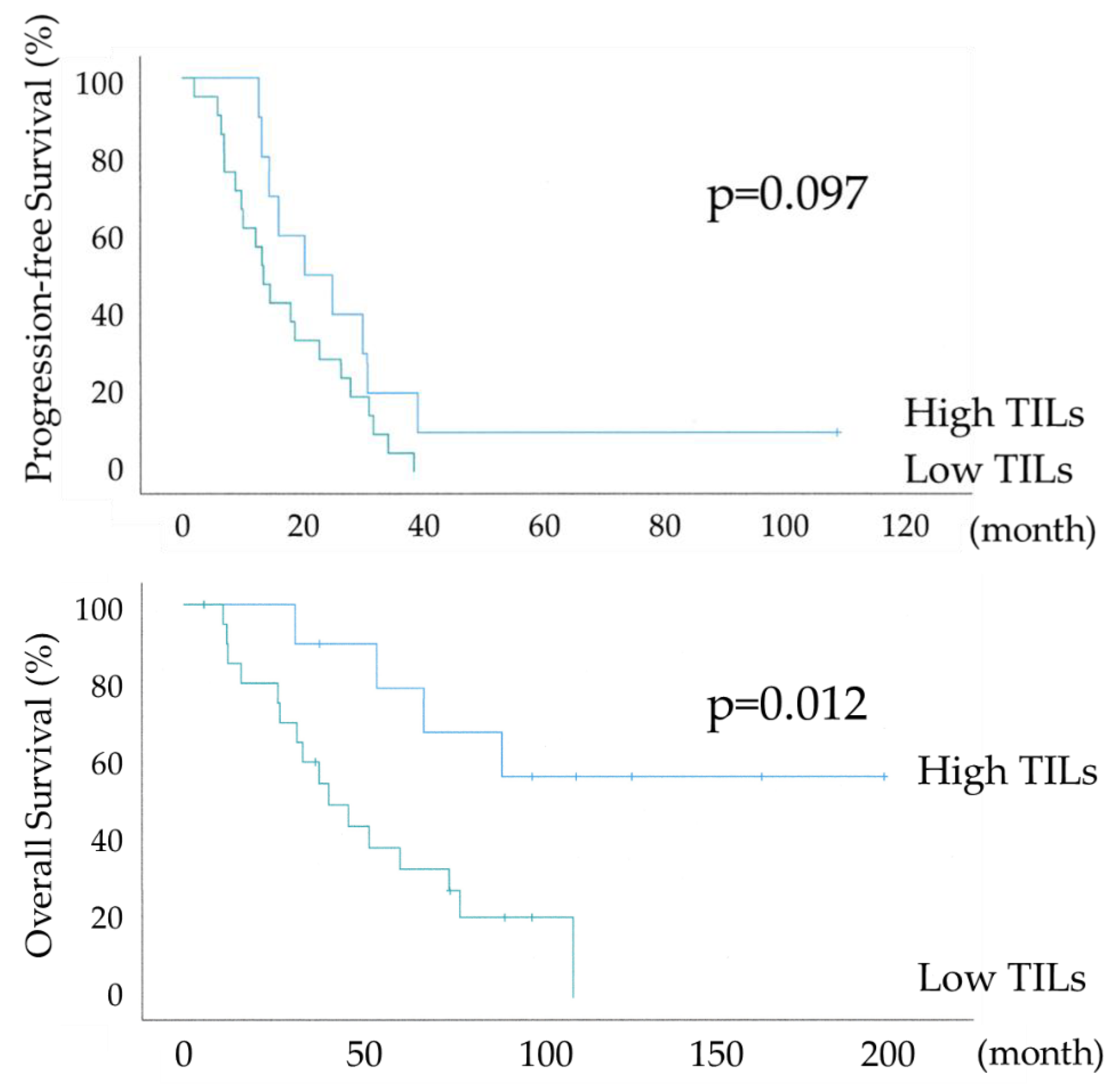

Figure 5 shows the differential Kaplan–Meier PFS and OS curves in the suboptimal surgery group for the High or Low TILs. The median PFS was 20 months (range 7-32) in 10 patients with HGSOC with High TILs and 13 months (range 10-15) in 21 women with HGSOC with Low TILs, and their median OS was 58 months (range 34-81) and 39 months (range 22-55). PFS showed a significant trend, whereas OS was significantly prolonged in the High TILs group (P-values =0.097 and =0.012, respectively). In the High TILs group, >50% OS was observed at 120 months. The lack of a significant difference in PFS is because the suboptimal surgery group has a higher risk of recurrence, as the gross residual tumor size at surgery was >1 cm.

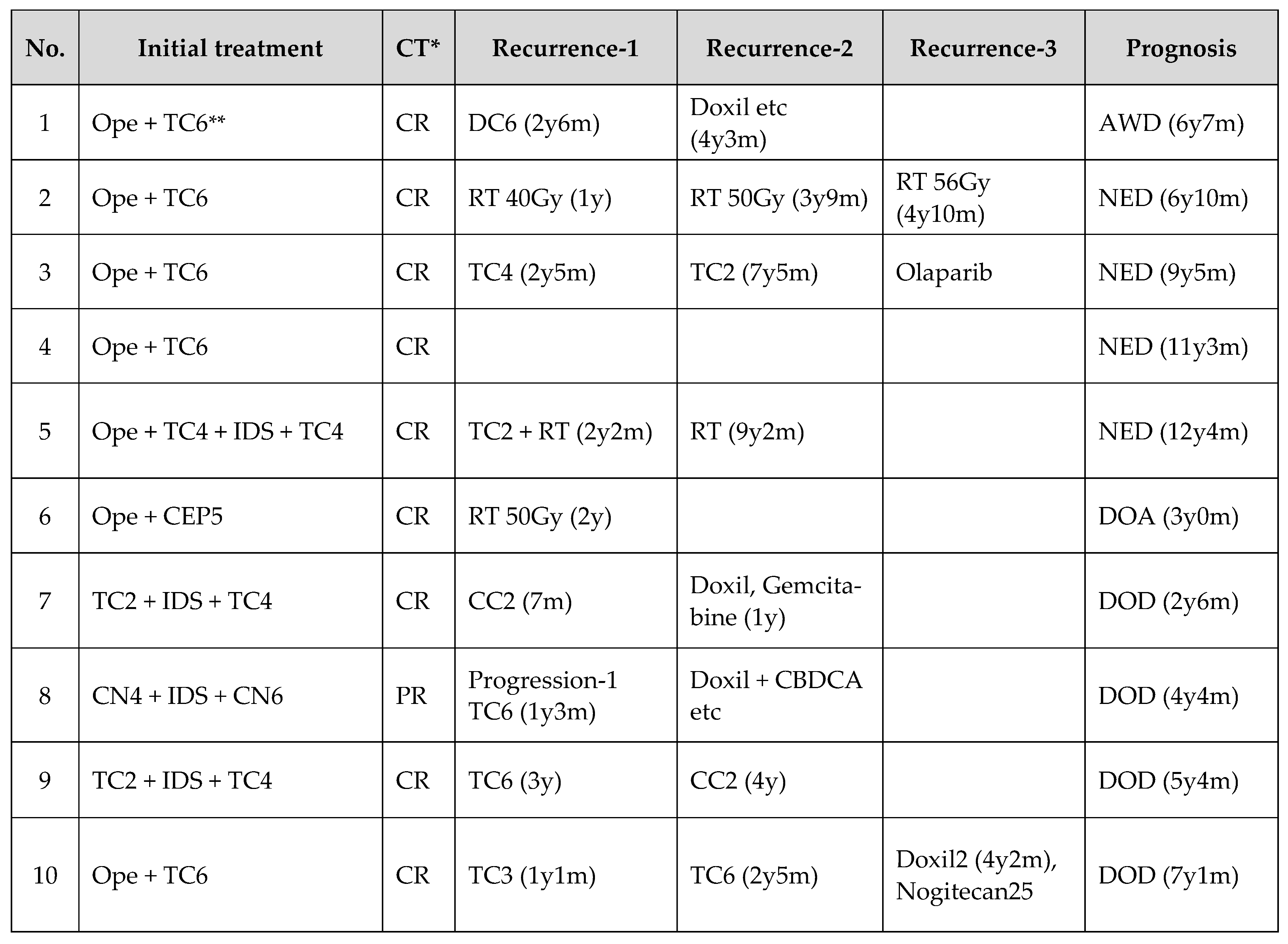

3.3. Clinical Data of 10 HGSOCs with High TILs in the Suboptimal Surgery Group

Regarding initial treatment, 6 patients received primary debulking surgery (PDS) and 4 patients received Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) + Interval debulking surgery (IDS). RECIST evaluation after initial treatment showed an overall response rate of 100%, with 9 cases as CR and one case remaining relapse-free. Platinum-based chemotherapy was used to treat recurrence in 7 cases and radiotherapy to control local recurrence in 3 cases. In only one case was a poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor used to treat recurrence, as the patient was diagnosed with HGSOC before 2017. In terms of prognosis, 7 cases had a post-treatment survival of more than 5 years.

3.4. Univariate and Multivariate Survival Time Analyses for PFS and OS

In the univariate analysis of PFS, significant differences were found in 7 categories, as shown in

Table 3. Multivariate analysis showed no significant differences except for the category of residual tumor at surgery (R0 + optimal vs suboptimal), with a significant trend towards the TILs category. In the univariate analysis of OS, significant differences were found in 5 categories, as shown in

Table 4. Multivariate analysis showed significant differences in the categories of CA125 levels before initial treatment, TILs, and residual tumor at surgery. Regarding the content of the analysis, it is well-known that residual tumor at surgery has an impact on prognosis, and TILs functioned as an independent prognostic indicator in OS.

4. Discussion

The initial treatment for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is primary debulking surgery (PDS) to remove as much tumor as possible to eliminate residual disease, followed by chemotherapy and maintenance therapy to prevent recurrence [

1]. However, patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer often have unresectable disease or medical complications that preclude primary debulking surgery. If the tumor cannot be removed with initial surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is administered to reduce the tumor size, followed by interval debulking surgery (IDS) to remove the tumor, and thereafter chemotherapy and maintenance therapy are continued. While suboptimal surgery (residual tumor≥1 cm) has a high risk of recurrence and a poor prognosis, complete resection (R0) or optimal surgery (residual tumor < 1cm*) is recommended [

1]. PDS and NACT+IDS have been compared in several clinical trials, with 3 trials showing non-inferiority of NACT+IDS, although NACT+IDS has a poor prognosis when complete resection cannot be achieved [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Achieving R0 or optimal surgery in PDS and R0 in NAC+IDS is associated with a longer prognosis. Meanwhile, based on genomic analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and histopathological findings, several reports have identified IR subtypes of HGSOCs and examined their prognostic value. [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The IR subtype is considered to have a better prognosis than the other subtypes; furthermore, the IR subtype tends to achieve R0 or optimal surgery more frequently and is reported to have a better prognosis than the other subtypes. However, in HGSOCs undergoing suboptimal surgery, the prognostic relevance of IR or the other subtypes has not been clarified.

As shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the IR subtype group tended to have more structural atypia and more cases of lymph node metastasis, with a bias towards oncological poor prognostic factors. Nevertheless, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, PFS and OS were significantly prolonged in the IR subtype group in all 74 cases and R0 + optimal surgery, and in

Figure 5, significant prolongation in OS was observed in the IR subtype even in suboptimal surgery.

Table 3 shows 100% overall response (OR) rates after initial treatment in the IR subtype group with suboptimal surgery. The majority of cases were CR. Although the suboptimal surgery group has a poor prognosis due to high tumor residuals, 7 out of 10 patients in the IR subtype had a survival of more than 5 years. Despite multiple recurrences due to residual tumors at surgery in many cases, the prognosis for the IR subtype was maintained due to the high treatment response to recurrence. In univariate and multivariate analyses of all 74 cases shown in

Table 4 and Table 5, residual tumor after surgery was an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS. There was a significant trend towards TILs in the multivariate analysis for PFS and a statistically significant difference in the multivariate analysis for OS, with TILs being the prognostic indicator.

TILs have been studied for decades and high levels of intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration have been reported as a good prognostic biomarker [

6,

16]. Recent findings on the existence of immune surveillance mechanisms against cancer, cancer cell proliferation through cancer immune escape, and cancer immune subcycle in the tumor microenvironment have led to reports that TILs are involved in maintaining effector phase function[

17,

18,

19,

20]. In particular, CD8-positive T cells correlate with prolonged survival [

16,

21,

22]. Elimination of cancer cells requires activation or de-repression of T-cell function, and a state of impaired immune function known as immune dessert has been reported to reduce the efficacy of anticancer drug treatment [

20]. TILs have been reported to be associated with the immunotherapeutic response, including primary and secondary immunotherapy, in other cancers, suggesting a link with cancer immunity [

23,

24,

25]. There are also reports that low lymphocyte counts due to cachexia tendency and poor nutritional status suppress cancer immunity [

26]. Cancer immune responses are also involved in immunogenic tumor cell death after radiotherapy, including the abscopal effects [

27,

28,

29]. Thus, the importance of the cancer immunity cycle in treatment has been widely recognized since the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) [

19,

21]. The presence of intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration increases the response to treatment with anticancer agents or radiotherapy, leading to a favorable prognosis. In HGSOC, intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration was an independent prognostic indicator not only in the R0+optimal surgery group but also in the suboptimal surgery group. These results and previous findings indicate that TILs may be involved in the response to anticancer drug treatment and radiotherapy via cancer immunity in the initial and recurrent treatment.

The present study extracts the histological features and prognosis of HGSOC. One limitation is that the pathogenesis of HGSOC was assessed using surgical specimens at the time of initial treatment. Even in cases assessed as having low lymphocytic infiltration, inflammatory and immune responses might be strongly induced after the administration of anticancer agents. Alternatively, some cases may have a reduced immune response if bone marrow function is impaired due to the side effects of anticancer agents. It is uncertain whether a similar immune response occurs in cases with a pre-cachexia tendency. It is important to understand that immune responses can be both activated or suppressed depending on the influencing factors and therefore may not be the same as the immune response at surgical removal. A second limitation was the limited number of cases, as comparative studies of lymphocyte types and intraepithelial or stromal lymphocytes could not be performed, so further case accumulation is needed [

30,

31]. A third limitation is that almost no cases were treated with molecularly targeted drugs such as PARP inhibitors or bevacizumab, and BRCA status is unknown. Data from 2018 onwards will require more detailed analysis and case accumulation, due to the greater prognostic impact of BRCA status and the addition of maintenance therapy [

32]. This is both a limitation and an interesting aspect of this study: before the advent of PARP inhibitor or ICI, when chemotherapy and radiotherapy were the predominant treatment modalities, including for other cancers, the focus of myelosuppression was on neutropenia. However, it is now clear that cancer immunocompetence is maintained by the lymphocyte-based immune cycle. Although the efficacy of ICI in the field of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer is still unclear, the need for immune maintenance therapy to support lymphocyte-based immunity during chemotherapy, PARP inhibitor, molecular-targeted anticancer agents, or radiotherapy will be discussed in the future.

5. Conclusions

Intra-tumoral lymphocytic infiltration of the IR subtype is an independent and favorable prognostic indicator in HGSOC and is associated with sensitivity to anticancer agents and radiotherapy via cancer immunocompetence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Toru Hachisuga, and Hiroshi Harada; methodology, Hiroshi Harada, Toru Hachisuga, Yoshikazu Harada and Fariza nuratdinova; software, Hiroshi Harada and Yoshikazu Harada; validation, Hiroshi Harada; formal analysis, Hiroshi Harada, Yoshikazu Harada and Toru Hachisuga; investigation Toru Hachisuga and Hiroshi Harada; resources, Midori Murakami, Shota Higami, Atsushi Tohyama, Yasuyuki Kinjo, Taeko Ueda, Tomoko Kurita and Yusuke Matsuura; data curation, Toru Hachisuga; writing—original draft preparation, Hiroshi Harada; writing—review and editing, Toru Hachisuga, Mami Shibahara and Hiroshi Harada; visualization, Hiroshi Harada and Mami Shibahara; supervision, Hiroshi Harada; project administration, Hiroshi Harada; funding acquisition, Kiyoshi Yoshino and Toshiyuki Nakayama. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital for Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (protocol code UOEHCRB21-155).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berek, J.S.; Renz, M.; Kehoe, S.; Kumar, L.; Friedlander, M. Cancer of the Ovary, Fallopian Tube, and Peritoneum: 2021 Update. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.; Berchuck, A.; Birrer, M.; Chien, J.; Cramer, D.W.; Dao, F.; Dhir, R.; Disaia, P.; Gabra, H.; Glenn, P.; et al. Integrated Genomic Analyses of Ovarian Carcinoma. Nature 2011, 474, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tothill, R.W.; Tinker, A. V.; George, J.; Brown, R.; Fox, S.B.; Lade, S.; Johnson, D.S.; Trivett, M.K.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Locandro, B.; et al. Novel Molecular Subtypes of Serous and Endometrioid Ovarian Cancer Linked to Clinical Outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 5198–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, R.; Matsumura, N.; Mandai, M.; Yoshihara, K.; Tanabe, H.; Nakai, H.; Yamanoi, K.; Abiko, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Hamanishi, J.; et al. Establishment of a Novel Histopathological Classification of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma Correlated with Prognostically Distinct Gene Expression Subtypes. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Katsaros, D.; Gimotty, P.A.; Massobrio, M.; Regnani, G.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Gray, H.; Schlienger, K.; Liebman, M.N.; et al. Intratumoral T Cells, Recurrence, and Survival in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K.; Murakami, R.; Ueda, A.; Kashima, Y.; Miyagawa, C.; Taki, M.; Yamanoi, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hamanishi, J.; Minamiguchi, S.; et al. A Deep Learning–Based Assessment Pipeline for Intraepithelial and Stromal Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2024, 194, 1272–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, J.A.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Amant, F.; Concin, N.; Davidson, B.; Fotopoulou, C.; González-Martin, A.; Gourley, C.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; et al. ESGO–ESMO–ESP Consensus Conference Recommendations on Ovarian Cancer: Pathology and Molecular Biology and Early, Advanced and Recurrent Disease. In Proceedings of the Annals of Oncology; Ann Oncol, March 1 2024; Vol. 35; pp. 248–266. [Google Scholar]

- Vergote, I.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Lorusso, D.; Gourley, C.; Mirza, M.R.; Kurtz, J.E.; Okamoto, A.; Moore, K.; Kridelka, F.; McNeish, I.; et al. Clinical Research in Ovarian Cancer: Consensus Recommendations from the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e374–e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours: Revised RECIST Guideline (Version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachisuga, T.; Murakami, M.; Harada, H.; Ueda, T.; Kurita, T.; Kagami, S.; Yoshino, K.; Tajiri, R.; Hisaoka, M. Prognostic Significance of Intra-Tumoral Budding in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinomas. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergote, I.; Tropé, C.G.; Amant, F.; Kristensen, G.B.; Ehlen, T.; Johnson, N.; Verheijen, R.H.M.; van der Burg, M.E.L.; Lacave, A.J.; Panici, P.B.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy or Primary Surgery in Stage IIIC or IV Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, S.; Hook, J.; Nankivell, M.; Jayson, G.C.; Kitchener, H.; Lopes, T.; Luesley, D.; Perren, T.; Bannoo, S.; Mascarenhas, M.; et al. Primary Chemotherapy versus Primary Surgery for Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer (CHORUS): An Open-Label, Randomised, Controlled, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onda, T.; Satoh, T.; Ogawa, G.; Saito, T. Comparison of Survival between Primary Debulking Surgery and Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III / IV Ovarian, Tubal and Peritoneal Cancers in Phase III Randomised Trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 130, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotti, A.; Ferrandina, G.; Vizzielli, G.; Fanfani, F.; Gallotta, V.; Chiantera, V.; Costantini, B.; Margariti, P.A.; Gueli Alletti, S.; Cosentino, F.; et al. Phase III Randomised Clinical Trial Comparing Primary Surgery versus Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer with High Tumour Load (SCORPION Trial): Final Analysis of Peri-Operative Outcome. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 59, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, H.; Tokunaga, H.; Matsuo, K.; Matsumura, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tabata, T.; Kaneuchi, M.; Nagase, S.; Mikami, M. Survival Outcome and Perioperative Complication Related to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Advanced Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restifo, N.P.; Dudley, M.E.; Rosenberg, S.A. Adoptive Immunotherapy for Cancer: Harnessing the T Cell Response. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 12, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, R.D.; Old, L.J.; Smyth, M.J. Cancer Immunoediting: Integrating Immunity’s Roles in Cancer Suppression and Promotion. Science (80-. ). 2011, 331, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horinaka, A.; Sakurai, D.; Ihara, F.; Makita, Y.; Kunii, N.; Motohashi, S.; Nakayama, T.; Okamoto, Y. Invariant NKT Cells Are Resistant to Circulating CD15+ Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The Blockade of Immune Checkpoints in Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellman, I.; Chen, D.S.; Powles, T.; Turley, S.J. The Cancer-Immunity Cycle: Indication, Genotype, and Immunotype. Immunity 2023, 56, 2188–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanishi, J.; Mandai, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Okazaki, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Yagi, H.; Takakura, K.; Minato, N.; et al. Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1 and Tumor-Infiltrating CD8+ T Lymphocytes Are Prognostic Factors of Human Ovarian Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 3360–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, H.; Christe, L.; Eichmann, M.; Reinhard, S.; Zlobec, I.; Blank, A.; Lugli, A. Tumour Budding/T Cell Infiltrates in Colorectal Cancer: Proposal of a Novel Combined Score. Histopathology 2020, 76, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, J.M.; Panda, A.; Zhong, H.; Hirshfield, K.; Damare, S.; Lane, K.; Sokol, L.; Stein, M.N.; Rodriguez-Rodriquez, L.; Kaufman, H.L.; et al. Immune Activation and Response to Pembrolizumab in POLE-Mutant Endometrial Cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 2334–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, H.; Nakayama, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Nakamura, K.; Ishibashi, T.; Sanuki, K.; Ono, R.; Sasamori, H.; Minamoto, T.; Iida, K.; et al. Microsatellite Instability Is a Biomarker for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Endometrial Cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 5652–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakaee, M.; Adib, E.; Ricciuti, B.; Sholl, L.M.; Shi, W.; Alessi, J. V.; Cortellini, A.; Fulgenzi, C.A.M.; Viola, P.; Pinato, D.J.; et al. Association of Machine Learning-Based Assessment of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes on Standard Histologic Images with Outcomes of Immunotherapy in Patients with NSCLC. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Saldajeno, D. Pietro; Kawaguchi, K.; Kawaoka, S. Progressive, Multi-Organ, and Multi-Layered Nature of Cancer Cachexia. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Mimura, K.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Ohkubo, Y.; Izawa, S.; Murata, K.; Fujii, H.; Nakano, T.; Kono, K. Immunogenic Tumor Cell Death Induced by Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3967–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohba, K.; Omagari, K.; Nakamura, T.; Ikuno, N.; Saeki, S.; Matsuo, I.; Kinoshita, H.; Masuda, J.; Hazama, H.; Sakamoto, I.; et al. Abscopal Regression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Radiotherapy for Bone Metastasis. Gut 1998, 43, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Demaria, S.; Formenti, S. Current Clinical Trials Testing the Combination of Immunotherapy with Radiotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Benito, D.; Vercher, E.; Conde, E.; Glez-Vaz, J.; Tamayo, I.; Hervas-Stubbs, S. Inflammation and Immunity in Ovarian Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer, Suppl. 2020, 15, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, E.; Olson, S.H.; Ahn, J.; Bundy, B.; Nishikawa, H.; Qian, F.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Frosina, D.; Gnjatic, S.; Ambrosone, C.; et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and a High CD8+/Regulatory T Cell Ratio Are Associated with Favorable Prognosis in Ovarian Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 18538–18543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsed, D.W.; Pandey, A.; Fereday, S.; Kennedy, C.J.; Takahashi, K.; Alsop, K.; Hamilton, P.T.; Hendley, J.; Chiew, Y.E.; Traficante, N.; et al. The Genomic and Immune Landscape of Long-Term Survivors of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).