Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

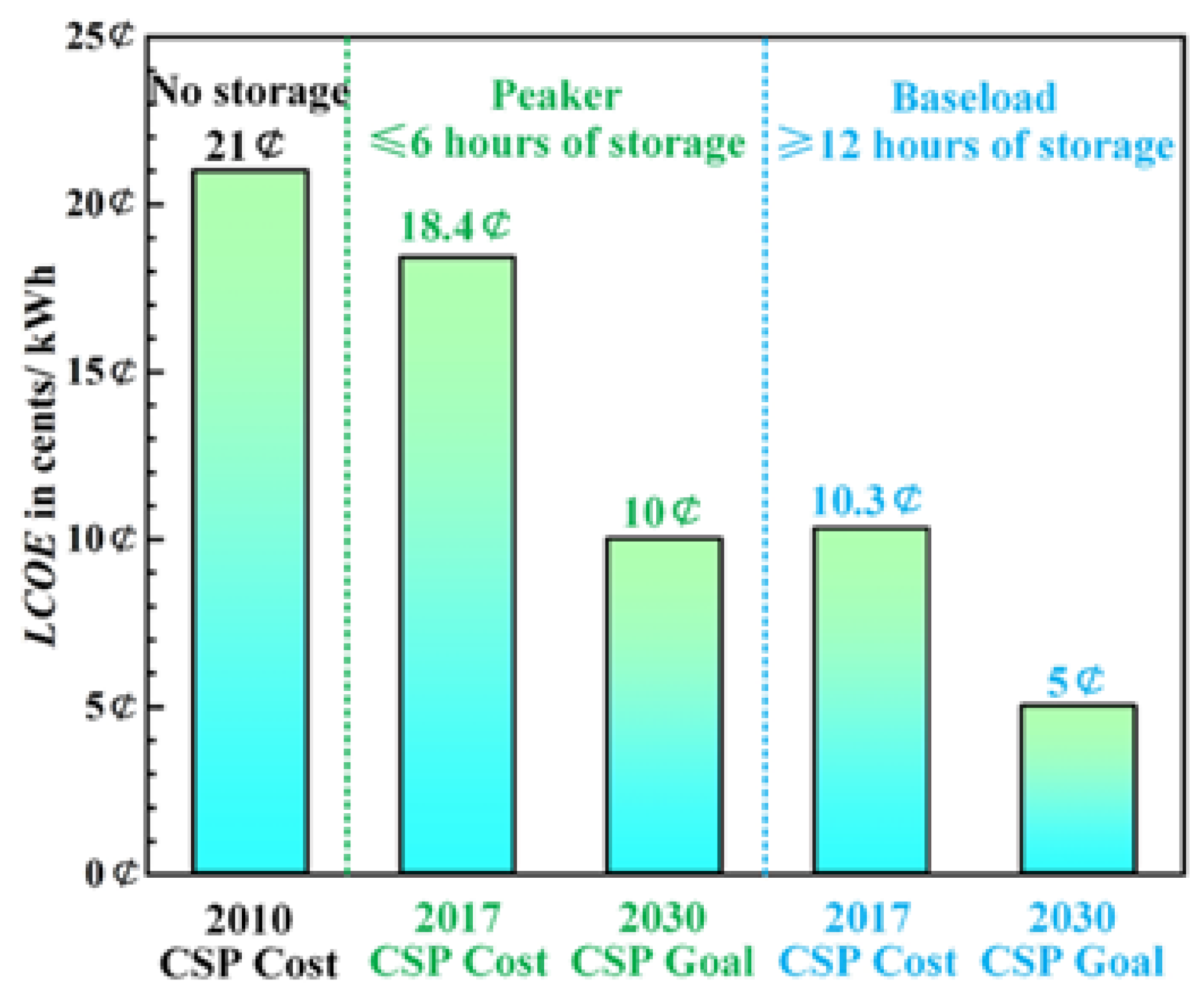

- There is no review that is specific to solar RCBC various configurations in the renewable energy heat sources. This niche needs deep analysis because it is environmentally sustainable and has high and promising thermal efficiencies [12] with concerted research efforts to lower the concentrated solar power (CSP) side LCOE.

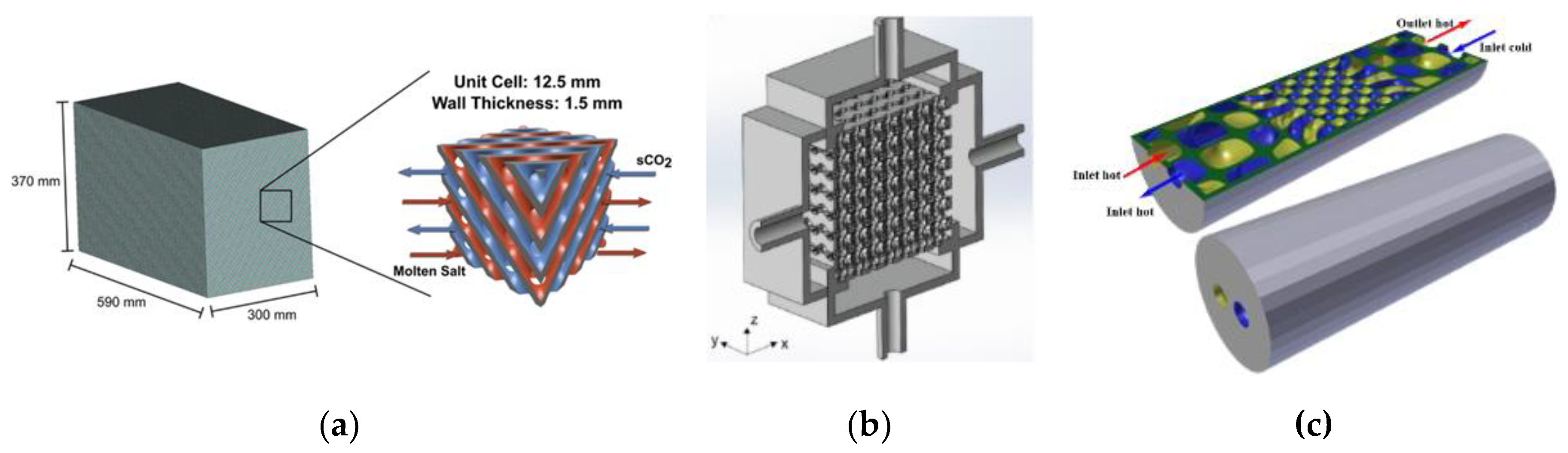

- There is no survey that covers hybrid TPMS HXs within the context of their application to RCBC recuperators.

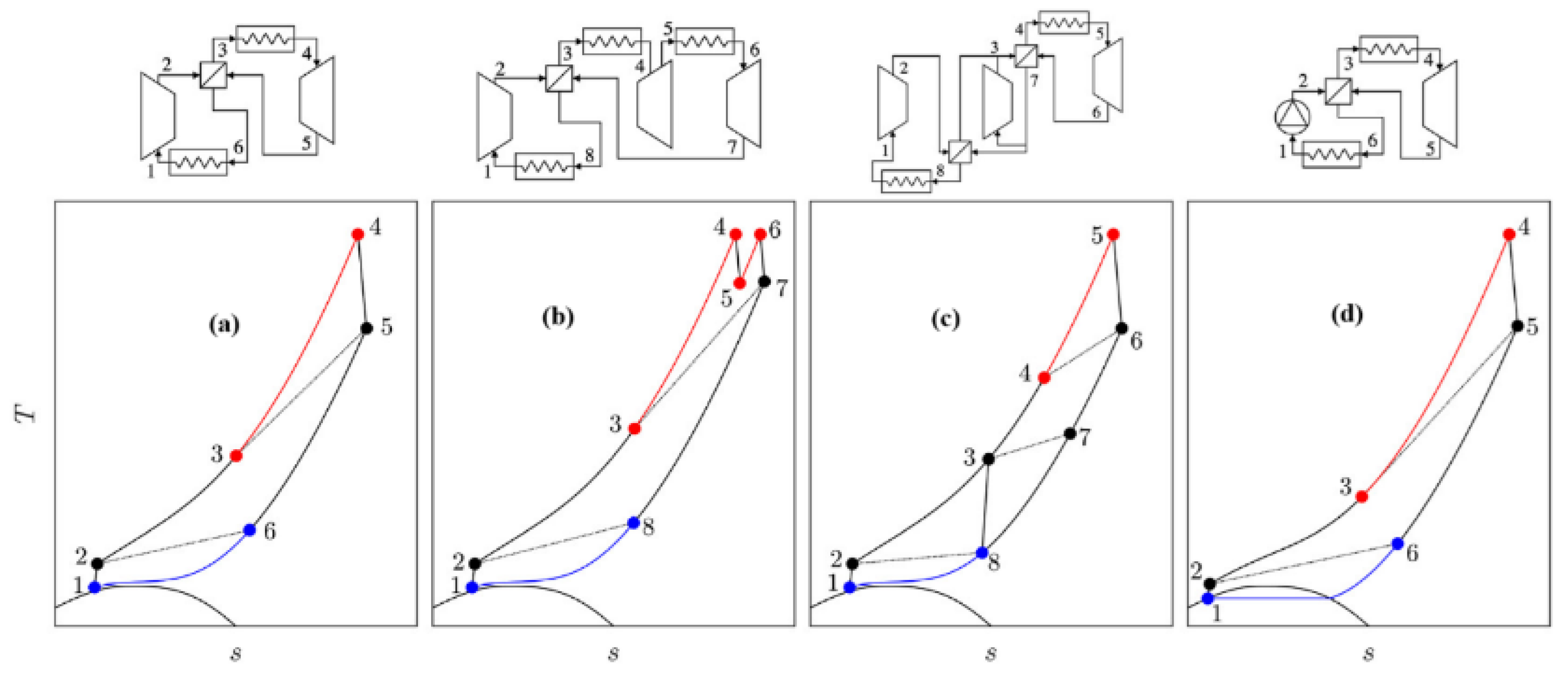

2. The Physics of the RCBC

3. Brief History of RCBC

Experimental Facilities of RCBC

4. RCBC State of the Art Studies

Modeling of Solar RCBCs

5. Key Components

Heat Exchangers (Primary Heaters, Recuperators and Coolers)

6. Materials, Cost and Manufacturability of TPMS HXs

6.1. Materials

6.2. Manufacturability

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Jiang, P. Thermodynamic optimization of heat transfer process in thermal systems using CO₂ as the working fluid based on temperature glide matching. Energy 2018, 151, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilarasan, S. K.; et al. Recent Developments in Supercritical CO₂-Based Sustainable Power Generation Technologies. Energy 2024, 17, 64019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D. Supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycle: A state-of-the-art review. Energy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostal, V.; Driscoll, M. J.; Hejzlar, P. Advanced Nuclear Power Technology Program. 2004. Available online: http://web.mit.edu/canes/.

- The Energy Institute. In partnership with Statistical Review of World Energy 2023 | 72nd edition, 2023.

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, E.; Li, M. Economic comparison between sCO₂ power cycle and water-steam Rankine cycle for coal-fired power generation system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 238, 114150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M. S.; Santana, D. Thermodynamic and exergoeconomic optimization of a new combined cooling and power system based on supercritical CO₂ recompression Brayton cycle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 295, 117592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M. L.; Lemmon, E. W.; Bell, I. H.; McLinden, M. O. The NIST REFPROP Database for Highly Accurate Properties of Industrially Important Fluids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 15449–15472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelino, G.; Invernizzi, C. Real gas Brayton cycles for organic working fluids. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A: J. Power Energy 2001, 215, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira, A.; Muñoz-Antón, J.; Montes, M. J.; Martínez-Val, J. Optimization of Brayton cycles for low-to-moderate grade thermal energy sources. Energy 2013, 55, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, R. E.; Rashdan, A. Supercritical CO₂ Direct Cycle Gas Fast Reactor (SC-GFR) Concept.

- Guo, J. Q.; et al. A systematic review of supercritical carbon dioxide (S-CO₂) power cycle for energy industries: Technologies, key issues, and potential prospects. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T. G.; Parma, E. J.; Wright, S. A.; Vernon, M. E.; Fleming, D. D.; Rochau, G. E. Sandia’s Supercritical CO₂ Direct Cycle Gas Fast Reactor (SC-GFR) Concept. In ASME 2011 Small Modular Reactors Symposium; ASME, 2011; pp. 91–94. [CrossRef]

- Maskery, I.; et al. Insights into the mechanical properties of several triply periodic minimal surface lattice structures made by polymer additive manufacturing. Polymer (Guildf.) 2018, 152, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Abu Al-Rub, R. K. Multifunctional Mechanical Metamaterials Based on Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Lattices. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, G.; Yu, Z. Bioinspired heat exchangers based on triply periodic minimal surfaces for supercritical CO₂ cycles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 179, 115686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, S.; Donev, A. Minimal surfaces and multifunctionality. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 2004, 460, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmalingam, L. K.; Aute, V.; Ling, J. Review of Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) Based Heat Exchanger Designs. Int. Refrig. Air Cond. Conf. Purdue 2022. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc.

- Çulfaz, P. Z.; et al. Fouling Behavior of Microstructured Hollow Fiber Membranes in Dead-End Filtrations: Critical Flux Determination and NMR Imaging of Particle Deposition. Langmuir 2011, 27, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çulfaz, P. Z.; Wessling, M.; Lammertink, R. G. H. Fouling behavior of microstructured hollow fiber membranes in submerged and aerated filtrations. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çulfaz, P. Z.; Haddad, M.; Wessling, M.; Lammertink, R. G. H. Fouling behavior of microstructured hollow fibers in cross-flow filtrations: Critical flux determination and direct visual observation of particle deposition. J. Memb. Sci. 2011, 372, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, E. Periodic Minimal Surfaces of Cubic Symmetry. Curr. Sci. 2003, 85, 346–362, Available online: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/policies.html. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, D.; Pasch, J.; Conboy, T.; Carlson, M. Testing Platform and Commercialization Plan for Heat Exchanging Systems for SCO₂ Power Cycles. In Volume 8: Supercritical CO₂ Power Cycles; Wind Energy; Honors and Awards; ASME, 2013. [CrossRef]

- White, M. T.; Bianchi, G.; Chai, L.; Tassou, S. A.; Sayma, A. I. Review of supercritical CO₂ technologies and systems for power generation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molière, M.; Privat, R.; Jaubert, J. N.; Geiger, F. Supercritical CO₂ Power Technology: Strengths but Challenges. Energies 2024, 17, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, R. V.; Soo Too, Y. C.; Benito, R.; Stein, W. Exergetic analysis of supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycles integrated with solar central receivers. Appl. Energy 2015, 148, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.-J.; Guo, J.-Q.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.-B. A systematic comparison of different S-CO₂ Brayton cycle layouts based on multi-objective optimization for applications in solar power tower plants. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, J. S. The work of Thomas Andrews and James Thomson on the liquefaction of gases. Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 2003, 57, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzer, G. Verfahren zur erzeugung von arbeit aus warme. Swiss Patent 269599 1950.

- Angelino, G. Real Gas Effects in Carbon Dioxide Cycles. In ASME 1969 Gas Turbine Conference and Products Show; ASME, 1969. [CrossRef]

- Angelino, G. Carbon Dioxide Condensation Cycles For Power Production. J. Eng. Power 1968, 90, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelino, G. Perspectives for the Liquid Phase Compression Gas Turbine. J. Eng. Power 1967, 89, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Su, W.; Lin, X.; Zhou, N. Recent trends of supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycle: Bibliometric analysis and research review. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

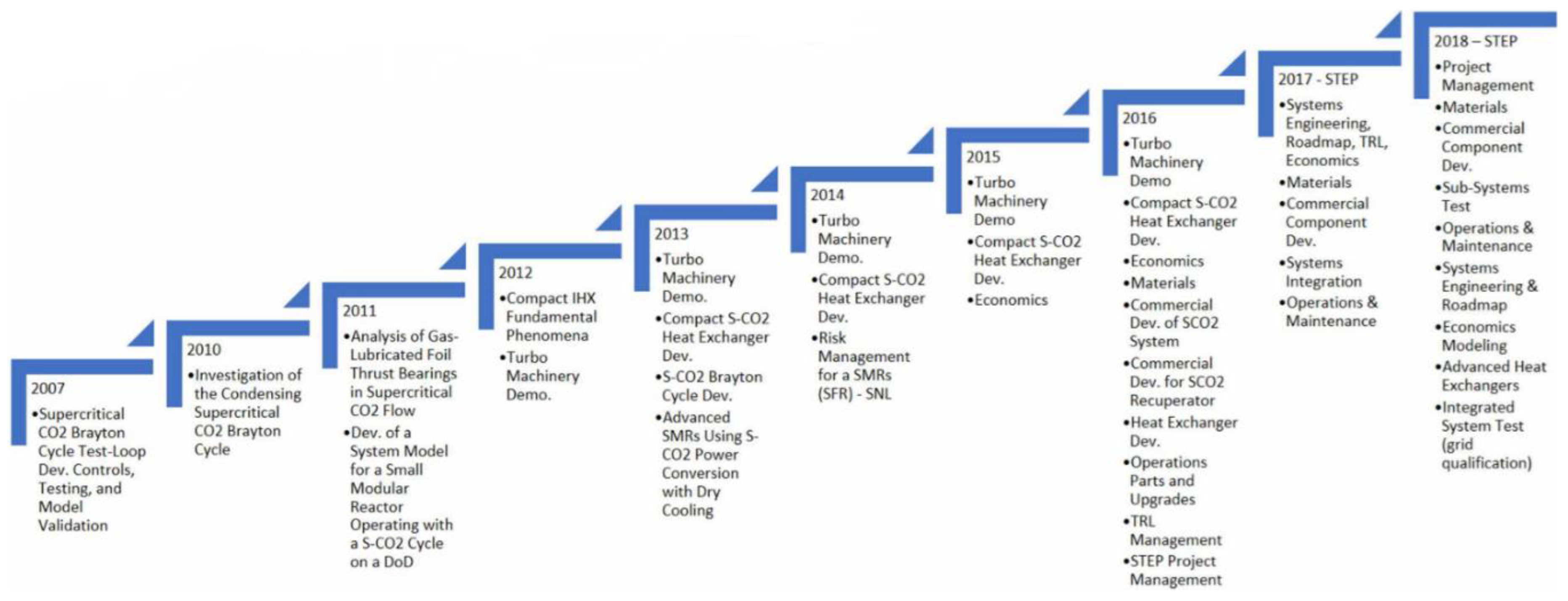

- Mendez, C. M.; Rochau, G. sCO₂ Brayton Cycle: Roadmap to sCO₂ Power Cycles NE Commercial Applications. 2018. Available online: https://classic.ntis.gov/help/order-methods/.

- Marchionni, M.; Bianchi, G.; Tassou, S. A. Review of supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO₂) technologies for high-grade waste heat to power conversion. Springer Nature 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. G.; et al. A concept design of supercritical CO₂ cooled SMR operating at isolated microgrid region. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-Y.; Lee, J. I.; Wi, M.-H.; Ahn, H. J. An investigation of sodium–CO₂ interaction byproduct cleaning agent for SFR coupled with S-CO₂ Brayton cycle. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2016, 297, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eoh, J.-H.; No, H. C.; Lee, Y.-B.; Kim, S.-O. Potential sodium–CO₂ interaction of a supercritical CO₂ power conversion option coupled with an SFR: Basic nature and design issues. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2013, 259, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-J.; Xu, J.-L.; Cao, F.; Guo, J.-Q.; Tong, Z.-X.; Zhu, H.-H. The investigation of thermo-economic performance and conceptual design for the miniaturized lead-cooled fast reactor composing supercritical CO₂ power cycle. Energy 2019, 173, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-J.; Jie, Y.-J.; Zhu, H.-H.; Qi, G.-J.; Li, M.-J. The thermodynamic and cost-benefit-analysis of miniaturized lead-cooled fast reactor with supercritical CO₂ power cycle in the commercial market. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2018, 103, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. G.; Cho, S.; Yu, H.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, Y. H.; Lee, J. I. System Design of a Supercritical CO₂ cooled Micro Modular Reactor. 2014.

- Yu, H.; Hartanto, D.; Oh, B. S.; Lee, J. I.; Kim, Y. Neutronics and Transient Analyses of a Supercritical CO₂-cooled Micro Modular Reactor (MMR). Energy Procedia 2017, 131, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; et al. The 5th International Symposium-Supercritical CO₂ Power Cycles RESEARCH ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF A SMALL-SCALE SUPERCRITICAL CARBON DIOXIDE POWER CYCLE EXPERIMENTAL TEST LOOP.

- Ahn, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. G.; Lee, J. I.; Cha, J. E. The Design Study of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Integral Experiment Loop. In Volume 8: Supercritical CO₂ Power Cycles; Wind Energy; Honors and Awards; ASME, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Conboy, T.; Radel, R.; Rochau, G. Modeling and experimental results for condensing supercritical CO₂ power cycles. Albuquerque, NM, and Livermore, CA (United States), 2011. [CrossRef]

- Clementoni, E. M.; Cox, T. L.; Sprague, C. P. Startup and Operation of a Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Brayton Cycle. In Volume 8: Supercritical CO₂ Power Cycles; Wind Energy; Honors and Awards; ASME, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Utamura, M.; et al. Demonstration of Supercritical CO₂ Closed Regenerative Brayton Cycle in a Bench Scale Experiment. In Volume 3: Cycle Innovations; Education; Electric Power; Fans and Blowers; Industrial and Cogeneration; ASME, 2012; pp. 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Guccione, S. Candidate; Guedez, R. Senior Researcher; Sánchez, Á. R.; Aranda, J. L.; Ruiz, A. Preliminary Results of the EU SolarSCO₂OL Demonstration Project: Enabling the Integration of Supercritical CO₂ Power Blocks into Hybrid CSP-PV Plants. Available online: http://www.emsp.uevora.pt/.

- Breakthrough for sCO₂ Power Cycle as STEP Demo Completes Phase 1 of 10 MW Project. Available online: https://www.powermag.com/breakthrough-for-sco2-power-cycle-as-step-demo-completes-phase-1-of-10-mw-project/.

- Sandia National Laboratories. Supercritical Transformational Electric Power (STEP) Nuclear Energy. Available online: https://energy.sandia.gov/programs/nuclear-energy/advanced-energy-conversion/supercritical-transformational-electric-power-step-nuclear-energy/.

- A Step Forward for sCO₂ Power Cycles; Modern Power Systems. Available online: https://www.modernpowersystems.com/analysis/a-step-forward-for-sco2-power-cycles-11423286/?cf-view&cf (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Murphy, C.; Sun, Y.; Cole, W.; Maclaurin, G.; Turchi, C.; Mehos, M. The Potential Role of Concentrating Solar Power within the Context of DOE’s 2030 Solar Cost Targets. 2030. Available online: www.nrel.gov/publications (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Abdelghafar, M. M.; Hassan, M. A.; Kayed, H. Comprehensive analysis of combined power cycles driven by sCO2-based concentrated solar power: Energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic perspectives. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 118046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznicek, E. P.; Neises, T.; Braun, R. J. Optimization and techno-economic comparison of regenerators and recuperators in sCO2 recompression Brayton cycles for concentrating solar power applications. Solar Energy 2022, 238, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Deng, Q.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Z. Numerical Investigation on the Flow Characteristics of a Supercritical CO2 Centrifugal Compressor. In Volume 3B: Oil and Gas Applications; Organic Rankine Cycle Power Systems; Supercritical CO2 Power Cycles; Wind Energy; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chacartegui, R.; Muñoz de Escalona, J. M.; Sánchez, D.; Monje, B.; Sánchez, T. Alternative cycles based on carbon dioxide for central receiver solar power plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.; Xu, J.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Xie, J. Synergetics: The cooperative phenomenon in multi-compressions S-CO2 power cycles. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2020, 7, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, M. M.; Duniam, S.; Guan, Z.; Gurgenci, H.; Klimenko, A. Seasonal variation on the performance of the dry cooled supercritical CO2 recompression cycle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 197, 111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binotti, M.; Astolfi, M.; Campanari, S.; Manzolini, G.; Silva, P. Preliminary assessment of sCO2 cycles for power generation in CSP solar tower plants. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Mishra, R. S. Energy- and exergy-based performance evaluation of solar powered combined cycle (recompression supercritical carbon dioxide cycle/organic Rankine cycle). Clean Energy 2018, 2, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, C. S.; Ma, Z.; Neises, T. W.; Wagner, M. J. Thermodynamic Study of Advanced Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Power Cycles for Concentrating Solar Power Systems. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2013, 135, 4024030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouta, A.; Al-Sulaiman, F.; Atif, M.; Bin Marshad, S. Entropy, exergy, and cost analyses of solar driven cogeneration systems using supercritical CO2 Brayton cycles and MEE-TVC desalination system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 115, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moullec, Y.; et al. SHOUHANG-EDF 10MWE SUPERCRITICAL CO2 CYCLE + CSP DEMONSTRATION PROJECT. In Conference Proceedings of the European sCO2 Conference; DuEPublico - Duisburg-Essen Publications Online, 2019; pp. 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Alsagri, A. S.; Chiasson, A.; Gadalla, M. Viability Assessment of a Concentrated Solar Power Tower with a Supercritical CO2 Brayton Cycle Power Plant. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2019, 141, 4043515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Wilkes, J.; Allison, T.; Bennett, J.; Wygant, K.; Pelton, R. Lowering the Levelized Cost of Electricity of a Concentrating Solar Power Tower with a Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Power Cycle. In Volume 9: Oil and Gas Applications; Supercritical CO2 Power Cycles; Wind Energy; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Crespi, F.; Sánchez, D.; Rodríguez, J. M.; Gavagnin, G. A thermo-economic methodology to select sCO2 power cycles for CSP applications. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 2905–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dong, B.; Chen, Z. Design and behaviour estimate of a novel concentrated solar-driven power and desalination system using S–CO2 Brayton cycle and MSF technology. Renew. Energy 2021, 176, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.-J.; Guo, J.-Q.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.-B. A systematic comparison of different S-CO2 Brayton cycle layouts based on multi-objective optimization for applications in solar power tower plants. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.-H.; Wang, K.; He, Y.-L. Thermodynamic analysis and comparison for different direct-heated supercritical CO2 Brayton cycles integrated into a solar thermal power tower system. Energy 2017, 140, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neises, T.; Turchi, C. Supercritical carbon dioxide power cycle design and configuration optimization to minimize levelized cost of energy of molten salt power towers operating at 650 °C. Solar Energy 2019, 181, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionni, M.; Bianchi, G.; Karvountzis-Kontakiotis, A.; Pesyridis, A.; Tassou, S. A. An appraisal of proportional integral control strategies for small scale waste heat to power conversion units based on Organic Rankine Cycles. Energy 2018, 163, 1062–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G.; et al. Design of a high-temperature heat to power conversion facility for testing supercritical CO2 equipment and packaged power units. Energy Procedia 2019, 161, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionni, M.; Bianchi, G.; Karvountzis-Kontakiotis, A.; Pesyridis, A.; Tassou, S. A. An appraisal of proportional integral control strategies for small scale waste heat to power conversion units based on Organic Rankine Cycles. Energy 2018, 163, 1062–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tano, I. N.; et al. A Scalable Compact Additively Manufactured Molten Salt to Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Heat Exchanger for Solar Thermal Application. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2024, 146, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chordia, L.; Portnoff, M. A.; Green, E. High Temperature Heat Exchanger Design and Fabrication for Systems with Large Pressure Differentials. Pittsburgh, PA, and Morgantown, WV, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Abu Al-Rub, R. K. MSLattice: A free software for generating two-dimensional and three-dimensional lattice structures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2020, 254, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. P.; et al. Binder jet additive manufacturing of ceramic heat exchangers for concentrating solar power applications with thermal energy storage in molten chlorides. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 56, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termpiyakul, P.; Jiraratananon, R.; Srisurichan, S. Heat and mass transfer characteristics of a direct contact membrane distillation process for desalination. Desalination 2005, 177, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Ma, R.; Zhang, W.; Fane, A. G.; Li, J. Direct contact membrane distillation mechanism for high concentration NaCl solutions. Desalination 2006, 188, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K. W.; Lloyd, D. R. Membrane distillation. J. Memb. Sci. 1997, 124, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane distillation: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Mavukkandy, M. O.; Loutatidou, S.; Arafat, H. A. Membrane distillation research & implementation: Lessons from the past five decades. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 189, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, Z. A.; Al-Omari, S. A. B.; Elnajjar, E.; Al-Ketan, O.; Al-Rub, R. A. On the effect of porosity and functional grading of 3D printable triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) based architected lattices embedded with a phase change material. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 183, 122111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan, V.; Chandrasekaran, P.; Nanda, M.; Maini, A. K.; Velraj, R. Role of PCM based nanofluids for energy efficient cool thermal storage system. Int. J. Refrigeration 2013, 36, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gado, M. G.; Hassan, H. Energy-saving potential of compression heat pump using thermal energy storage of phase change materials for cooling and heating applications. Energy 2023, 263, 126046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gado, M. G.; Ookawara, S.; Nada, S.; Hassan, H. Performance investigation of hybrid adsorption-compression refrigeration system accompanied with phase change materials − Intermittent characteristics. Int. J. Refrigeration 2022, 142, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; et al. Multiscale construction of bifunctional electrocatalysts for long-lifespan rechargeable zinc–air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2003619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; et al. Multiscale construction of bifunctional electrocatalysts for long-lifespan rechargeable zinc–air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2003619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, T.; Al-Hajri, E.; Paul, M. C.; Nithiarasu, P.; Kumar, S. High performance, microarchitected, compact heat exchanger enabled by 3D printing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 210, 118339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yoo, D.-J. 3D printed compact heat exchangers with mathematically defined core structures. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2020, 7, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

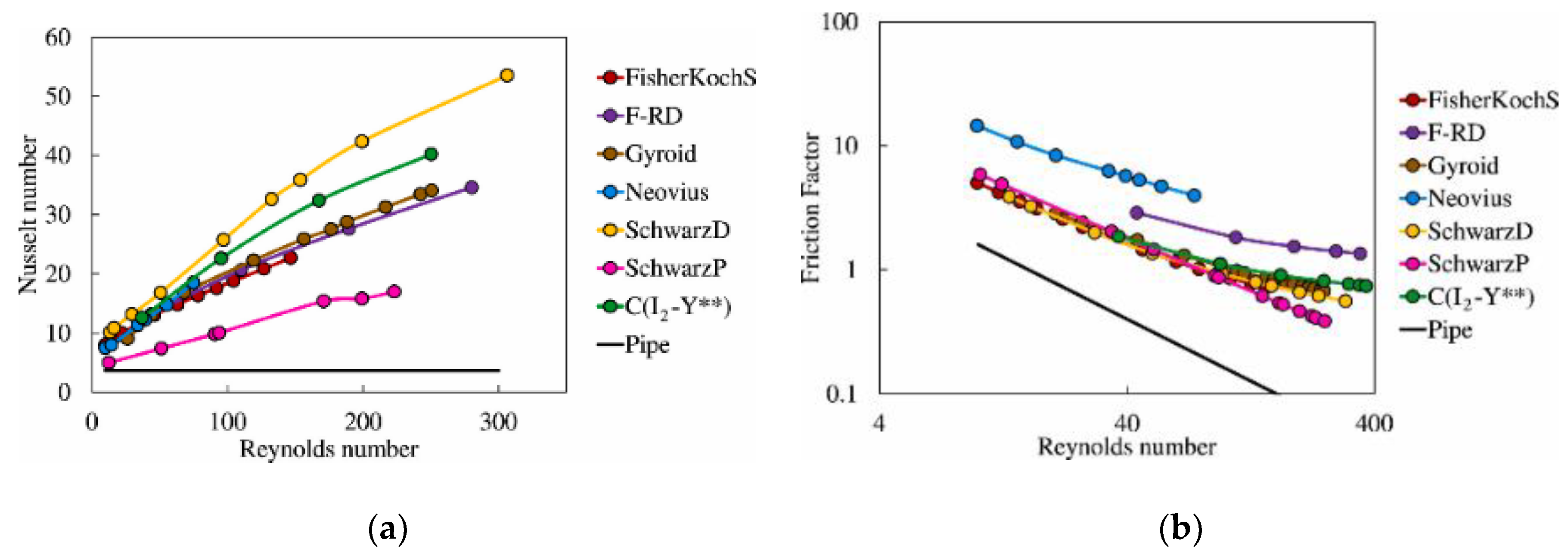

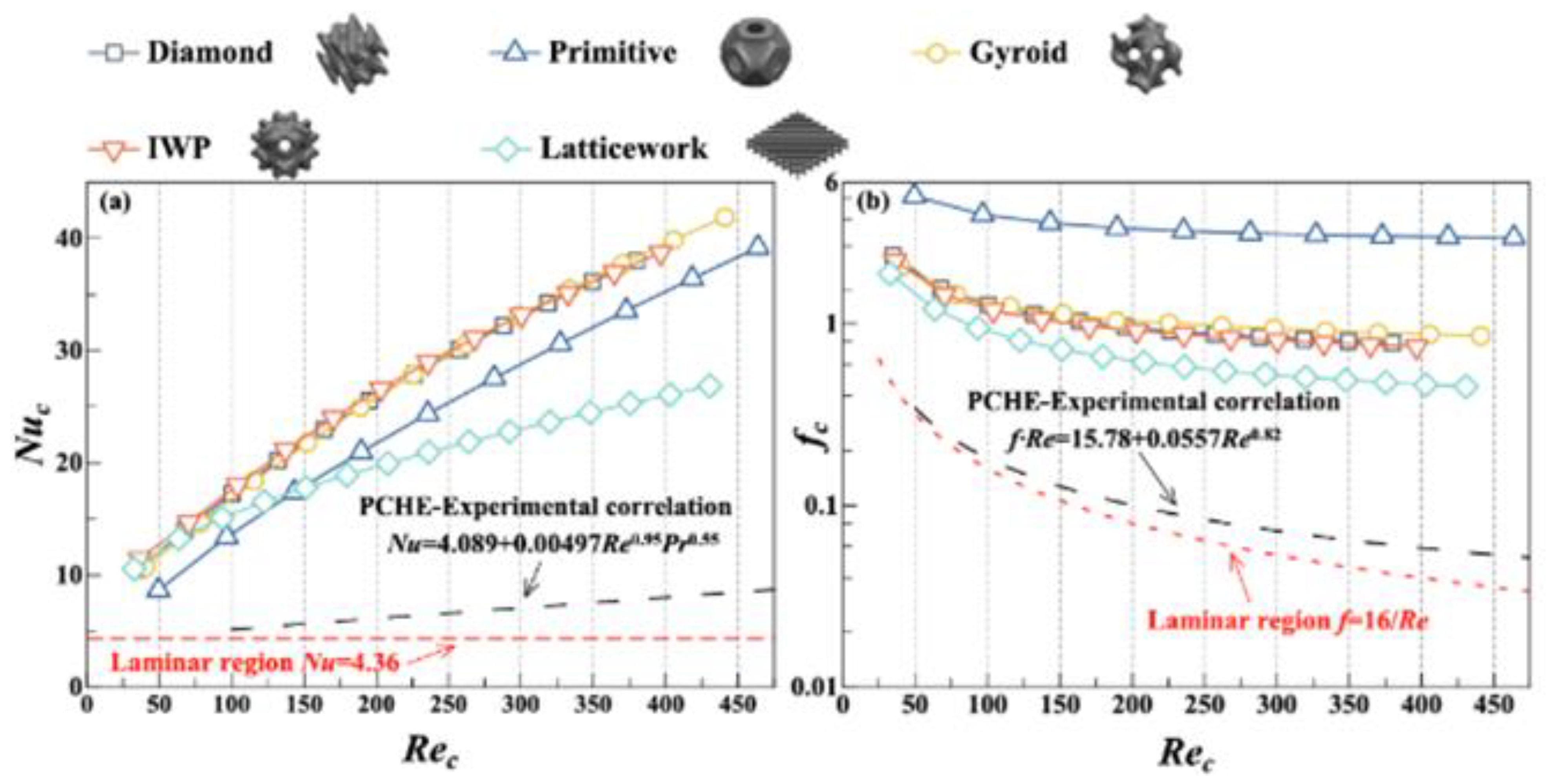

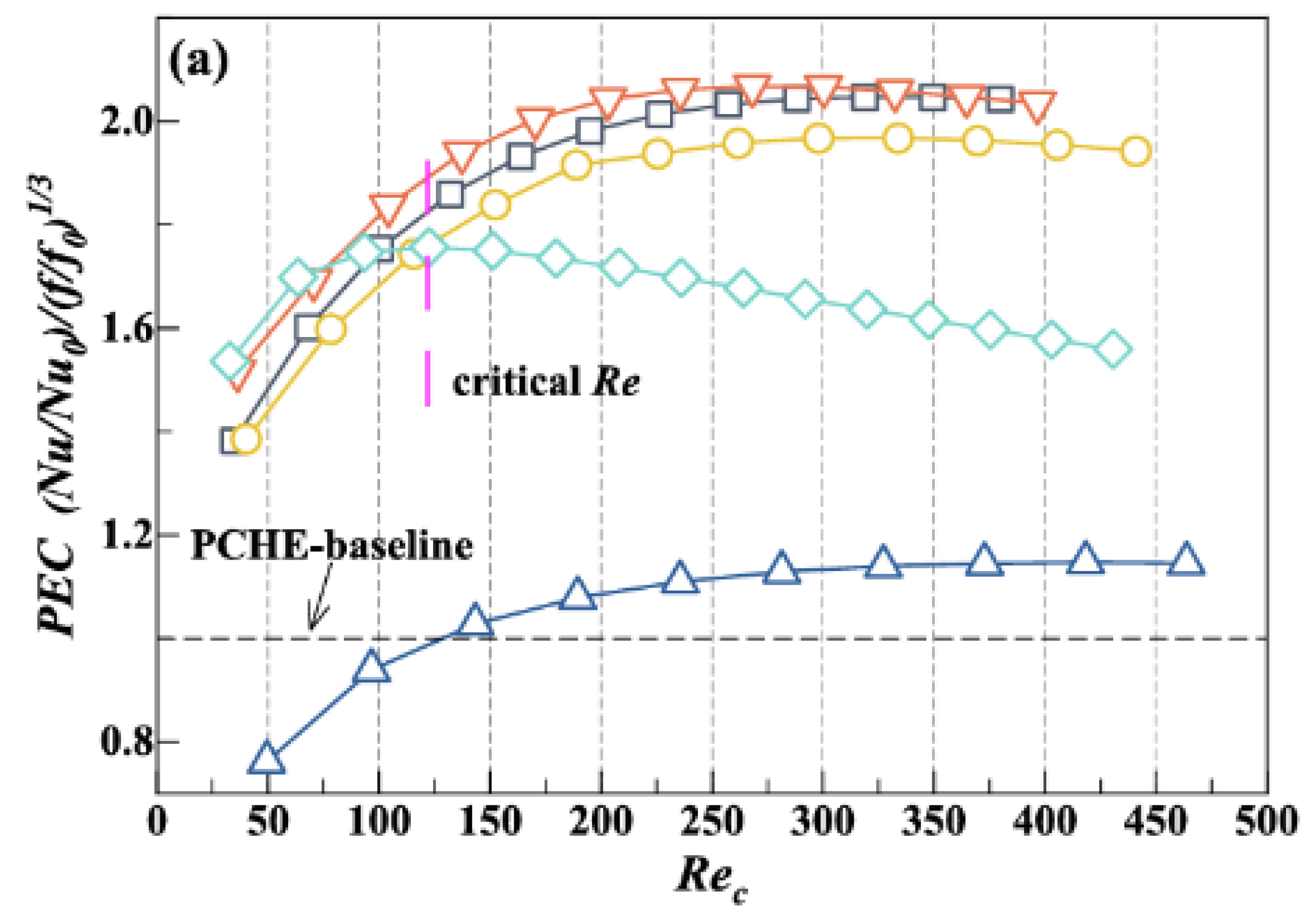

- Iyer, J.; Moore, T.; Nguyen, D.; Roy, P.; Stolaroff, J. Heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics of heat exchangers based on triply periodic minimal and periodic nodal surfaces. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 209, 118192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Deng, H. Numerical investigation into thermo-hydraulic characteristics and mixing performance of triply periodic minimal surface-structured heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230, 120748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Yu, Z. Heat transfer enhancement of water-cooled triply periodic minimal surface heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Yang, K.; Gu, H.; Chen, W.; Chyu, M. K. The effect of unit size on the flow and heat transfer performance of the ‘Schwartz-D’ heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 214, 124367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; et al. Experimental study on flow and heat transfer performance of triply periodic minimal surface structures and their hybrid form as disturbance structure. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 2023, 147, 106942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S. J.; Kwon, J.; Kim, S. G.; Son, I. W.; Lee, J. I. Condensation heat transfer and multi-phase pressure drop of CO2 near the critical point in a printed circuit heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 129, 1206–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I. H.; No, H. C. Thermal hydraulic performance analysis of a printed circuit heat exchanger using a helium-water test loop and numerical simulations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 4064–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.; Kim, S. G.; Lee, J.; Lee, J. I. Study on CO2–water printed circuit heat exchanger performance operating under various CO₂ phases for S-CO₂ power cycle application. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 113, 1536–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T. L.; Kato, Y.; Nikitin, K.; Ishizuka, T. Heat transfer and pressure drop correlations of microchannel heat exchangers with S-shaped and zigzag fins for carbon dioxide cycles. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2007, 32, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, K.; Kato, Y.; Ngo, L. Printed circuit heat exchanger thermal-hydraulic performance in supercritical CO2 experimental loop. Int. J. Refrigeration 2006, 29, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, N.; Kato, Y.; Ishiduka, T. High performance printed circuit heat exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2007, 27, 1702–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidaparti, S. R.; Anderson, M. H.; Ranjan, D. Experimental investigation of thermal-hydraulic performance of discontinuous fin printed circuit heat exchangers for supercritical CO2 power cycles. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2019, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, D. An Adaptive Flow Path Regenerator Used in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Brayton Cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 138, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.W.; Zhao, R.; Le Nian, Y.; Cheng, W.L. Experimental Study of Supercritical CO₂ in a Vertical Adaptive Flow Path Heat Exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 188, 116597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Huang, Y.P.; Wang, J.F.; Liu, R.L. Experimental Study on Transitional Flow in Straight Channels of Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 181, 115950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Huang, Y.P.; Wang, J.F.; Liu, R.L.; Zang, J.G. Experimental Study of Thermal-Hydraulic Performance of a Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger with Straight Channels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2020, 160, 120109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhou, J.; Huai, X.; Guo, J. Experimental Exergy Analysis of a Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger for Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Brayton Cycles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 192, 116882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cheng, K.; Huai, X.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z. Test Platform and Experimental Test on 100 kW Class Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger for Supercritical CO₂ Brayton Cycle. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2020, 148, 118540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Huai, X.; Guo, J. Experimental Investigation of Thermal-Hydraulic Characteristics of a Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger Used as a Pre-Cooler for the Supercritical CO₂ Brayton Cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 171, 115116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Cheng, S.; Wang, J. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Thermal-Hydraulic Characteristics in a Novel Airfoil Fin Heat Exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2021, 175, 121333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.X.; Li, X.H.; Ma, T.; Chen, Y.T.; Wang, Q. Experimental Investigation on SCO₂-Water Heat Transfer Characteristics in a Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger with Straight Channels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2017, 113, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Deng, T.R.; Ma, T.; Ke, H.B.; Wang, Q.W. A New Evaluation Method for Overall Heat Transfer Performance of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide in a Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 193, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.; Aakre, S.R.; Anderson, M.H.; Ranjan, D. Experimental Investigation of Pressure Drop and Heat Transfer in High Temperature Supercritical CO₂ and Helium in a Printed-Circuit Heat Exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2021, 171, 121089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theologou, K.; Hofer, M.; Mertz, R.; Buck, M.; Laurien, E.; Starflinger, J. Experimental Investigation and Modelling of Steam-Heated Supercritical CO₂ Compact Cross-Flow Heat Exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 190, 116352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Quan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Tian, Y. Multi-Morphology Transition Hybridization CAD Design of Minimal Surface Porous Structures for Use in Tissue Engineering. CAD Comput. Aided Design 2014, 56, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letlhare-Wastikc, K.; Yang, X. Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Hybridization and Novel Thin Walled AlSi10Mg Heat Exchanger Modeling for Sustainable Energy Applications. TechRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badescu, V.; Lazaroiu, G.C.; Barelli, L., Eds. POWER ENGINEERING: Advances and Challenges; CRC Press, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Nellis, G.; Corradini, M. Materials, Turbomachinery and Heat Exchangers for Supercritical CO₂ Systems. Idaho Falls, ID (United States), October 2012. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C.L.; et al. Material Selection and Manufacturing for High-Temperature Heat Exchangers: Review of State-of-the-Art Development, Opportunities, and Challenges. John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gerstler, W.D.; Erno, D. Introduction of an Additively Manufactured Multi-Furcating Heat Exchanger. In 2017 16th IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm); IEEE, May 2017; pp. 624–633. [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Huang, G.; Parbat, S.N.; Yang, L.; Chyu, M.K. Experimental Investigation on Additively Manufactured Transpiration and Film Cooling Structures. J. Turbomach. 2019, 141, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Gao, F.; Hu, W. Design, Modeling and Characterization on Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Heat Exchangers with Additive Manufacturing. In International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, Texas, 2019.

- Teneiji, A.I.M. Heat Transfer Effectiveness Characteristics Maps for Additively Manufactured Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces Compact Heat Exchanger. Master’s Thesis, Khalifa University, 2021.

- Gado, M.G.; Al-Ketan, O.; Aziz, M.; Al-Rub, R.A.; Ookawara, S. Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Structures: Design, Fabrication, 3D Printing Techniques, State-of-the-Art Studies, and Prospective Thermal Applications for Efficient Energy Utilization. John Wiley and Sons Inc., May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yoo, D.-J. 3D Printed Compact Heat Exchangers with Mathematically Defined Core Structures. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2020, 7, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fluid | CO2 | H2O | He | Air |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 44.01 | 18.015 | 4.0026 | 28.965 |

| Critical density/kg.m3 | 467.6 | 322 | 72.567 | 342.68 |

| Critical temperature/K | 304.13 | 647.1 | 5.1953 | 132.53 |

| Critical pressure/MPa | 7.3773 | 22.064 | 0.2276 | 3.786 |

| Project | Features |

|---|---|

| EPS100 (USA) | 8 MW, 532 oC, 24 % efficiency |

| NET Power, 8 Rivers Capital (USA) | Combustion gas, zero emission, 100% CO2 capture, high efficiency, low cost |

| STEP (USA) | 10 MW, 169 mil. US$ cost |

| SOLARSCO20L (EU) | 2 MW, Based on CSP, molten salt |

| Xi’an Thermal Power Co. Ltd., Harbin Boiler Co. Ltd. (China) | 5 MW, 33 MPa |

| Dunhuang, Shouhang IHW (China) | Solar thermal power plant, 10 MWe |

| Hengshui Zhongke HENGFA power Equipment Co. Ltd. (China) | 40 MPa PCHE pressure |

| Power plant | Energy eff. (%) | Exergy eff. (%) | Author/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCBC, TCC | 46.43 | 80.59 | [55] |

| RCBC | 43.22 | 75.01 | [55] |

| RCBC with MC intercooling & reheating | 42.7 - 52.2 | 22.3 – 22.9 | [26] |

| RCBC with MC intercooling | 41.3 – 53.8 | 21.6 – 22.4 | |

| RCBC with partial cooling & reheating | 41.1 - 54 | 21.5 – 22.4 | |

| RCBC with partial cooling | 39.2 – 52.3 | 20.5 – 21.7 | |

| RCBC | 40.1 – 51.8 | 20.5 – 21.5 | |

| RCBC with reheating | 41.1 – 52.8 | 20.9 - 22 | |

| RCBC | 33.8 | - | [56] |

| RCBC | 47.43 | - | [57] |

| RCBC tri-compression | 49.47 | - | [57] |

| RCBC dry cooled | 50.9 | - | [58] |

| RCBC | 23.6 | - | [59] |

| RCBC with partial cooling | 24.4 | - | |

| RCBC with intercooling | 24.5 | - | |

| RCBC with ORC bottoming | 63.86 – 85.83 | 35.57 – 47.82 | [60] |

| > 50 | - | [61] |

| Power plant | Optimization scheme | Energy eff. Function (%) | Electricity cost function | Author/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCBC | - | - | 0.0826 $/kWh | [62] |

| RCBC, intercooling & preheating | - | 35.6 | [63] | |

| RCBC | - | 46 | 0.11 $/kWh | [64] |

| RCBC | - | 48.8 | 0.0598 $/kw | [65] |

| RCBC partially cooled | - | 55 | (5015)a | [66] |

| RCBC | - | 36.6 | 0.059 $/kWh | [67] |

| RCBC | GA, NSGA-II | 26.3 – 29.8 | ||

| RCBC with partial cooling | 27.2 – 29.6 | [68] | ||

| RCBC with intercooling | 28.3 – 31.2 | |||

| RCBC | 29.4 – 31.3 | [69] | ||

| RCBC with partial cooling | GA | 28.3 – 30 | ||

| RCBC with intercooling | 29.6 – 31.5 | |||

| RCBC | 15.30 c/kWh | [70] | ||

| RCBC | 3930 $/kW | [154] |

| Equipment | Energy | Exergy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCBC | Turbine 1 | ||

| HTR | |||

| LTR | |||

| MC | |||

| Precooler-2 | |||

| RC | |||

| Heater | |||

| Efficiency | |||

| Power | |||

| TCC | Turbine 2 | ||

| Precooler-1 | |||

| Power | |||

| Optimization | …(1) where …(2), …(3), …(4), …(5)…(6) | ||

| …(7) …(8) …(9) …(10) | |||

| …(11) …(12)…(13) | |||

| Institution | Fluids | Channel | Material |

iDh /mm |

HTAj /m2 |

Refs. | Parameters Temp./oC, Pressure/MPa, **m/kgh-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAIST | CO2 | Z | SS316L | 1.8 | [96] |

S channel; Tcold: 23.1-108, Thot:25.4-300, Phot: 2.2-11.97, Pcold: 0.14-18, m: 20-650 Z channel; Tcold: 8-580, Thot:8-580, Phot: 1.0-9.5, Pcold: 0.1-22.5, m: 10-3636 Teardrop fin; Thot: 70–110, Phot: 7.6–9.0, mhot: 500–1800, Tcold: 16–25, Pcold: 0.1, mcold: 3m3h1 |

|

| He/CO2 | Z | Alloy 800HT | 0.922/0922 | 3.8/3.8 | [90,97] | ||

| CO2/H2O | Z | SS316L | 1.167 | 0.8 | [98] | ||

| TIT | CO2 | Z/SS | kSS316L | 1.09/1.09 | S:0.5099/0.2559 Z: 0.4653/0.2353 |

[99] | |

| CO2 | Z | 1.9/1.8 | 0.697/0.356 | [100] | |||

| CO2 | Z/SS | 1.88 | [101] | ||||

| GITa | CO2 | Rectangular NACA 0020 Airfoil |

SS316L | 0.9973 1.112 |

91.133* 24.94* |

[102] | |

| USTCb | CO2 | SS | mole steel M280 | [103] | |||

| CO2 | SS | steel M280 | 1.12/0.95 | 0.095821/0.101306 | [104] | ||

| SUc | CO2/H2O | S | SS316L | 1.14 | [105,106] | ||

| CASd | CO2 | Z | SS316L | [107] | |||

| CO2 | Z | SS316L | 1.83 | 2.291 | [108] | ||

| CO2/H2O | Z | SS316L | 1.5/1.6 | [109] | |||

| CO2/H2O | Teardrop fin | [110] | |||||

| XJUe | CO2/H2O | S | SUS304 | [111] | |||

| CO2/H2O | Z | SUS304 | 2.0 | [112] | |||

| WSMEf | He/CO2 | Z | SS316L | 1.0 | 0.14 | [113] | |

| ZUg | CO2 | - | 193 | ||||

| USh | CO2/H2O | Z | X5CrNi18-10 | 1.33 | [114] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).