1. Introduction

Al-Zn-Mg-Cu series alloy are widely used in military and aviation fields due to their low density and excellent mechanical properties[

1,

2,

3]. With the rapid development of these fields, the demand for the mechanical properties of alloys has higher standards. On the one hand, researchers began to focus on high-composition and rare earth added Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys that can provide higher strength[

4,

5,

6] and better formability[

7]. On the other hand, researchers focused on improving the overall performance of alloys through grain refinement[

8,

9,

10]. The methods of grain refinement are equal channel angular pressing (ECAP)[

10,

11,

12], severe plastic deformation (SPD)[

13,

14,

15], cryorolling[

16,

17] and especially thermo-mechanical treatment (TMT)[

18,

19,

20]. Among them, TMT is an effective way for large-scale production.

It has been found that TMT has the effect of affecting the particle size and distribution and thus the recrystallization mechanism during deformation, thereby achieving the effect of refining the grains to improve the ductility of the 7xxx series commercial aluminum alloys[

18,

19]. The application of ITMT(Intermediate TMT) in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys can be traced back to the ISML-ITMT(ITMT designed by Istituto Sperimentale dei Metalli Leggeri of Italy) process developed by Ri-Russo et al.[

21] in 1974. The main idea of the process is to obtain coarse MgZn

2 particles through low-temperature homogenization, then accumulate alloy energy storage through warm deformation, and finally static recrystallization occurs during the solid solution process. The advantage of this process is that the Cr-dispersoids precipitated during the recrystallization process hinder the continued growth of recrystallized grains. However, the difficulty in obtaining initial sheets of dissolved Cr and the drawbacks of deformation have hindered the widespread application of this process. Afterwards, Waldman et al.[

22] replaced low-temperature homogenization with multi-stage homogenization to form FA-ITMT(ITMT designed by Frankford Arsenal). Under such process conditions, the dissolution/precipitation of Cr element no longer has a significant impact on the recrystallization of the alloy, but it has resulted in a new problem of excessively long homogenization time. Based on previous research, Wert et al.[

23] developed RI-ITMT widely used in 7xxx commercial aluminum alloys by introducing coarse MgZn

2 particles through solid solution and over aging. Paton et al. successfully applied the RI-ITMT(ITMT designed by Rockwell International Science Center) process to 7075 aluminum alloy and improved its ductility while increasing its corrosion resistance. Malek et al.[

24] obtained fine grains with a size below 13 μm through the RI-ITMT process. Kumar et al.[

25] applied RI-ITMT technology in 7010 alloy and obtained fine recrystallized grains with a size of about 10 μm. At the same time, the alloy exhibits superplasticity at high temperatures. In recent years, with a deeper understanding, TMT processes have been developed with shorter processes, less time consumption, and lower energy consumption. For example, Huo et al.[

19] used warm rolling and continuous rolling instead of the over aging and warm rolling in RI-ITMT to reduce the average grain size of 7075 aluminum alloy sheet from 25 μm to 10 μm, which significantly improved the plasticity of the alloy.

The TMT process has been widely used in 7xxx series commercial aluminum alloys, but there are few reports on high-composition or ultra-high-strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. Therefore, this article proposes a short-flow TMT process (L-ITMT, ITMT designed by Li) suitable for high component aluminum alloys (including three processes: solid solution, warm deformation, and solid solution), and focuses on the evolution of recrystallization mechanism during the process of increasing deformation and its influence on the mechanical properties of the alloy.

2. Experimental Details

The materials used in this study are homogenized at 420°C for 10h and 470°C for 24h immediately after semi-continuous casting, and their chemical composition is shown in

Table 1. The plates used in the test were taken from the middle of the homogenized bar and had dimensions of 10 mm×50 mm×70 mm.

Figure 1b shows the schematic diagram of short-flow TMT process. All plates were quenched immediately after solutionizing at 475°C for 2 h. Afterwards, the plates were rolled with a deformation degree of up to 80% at 300°C (as shown in

Figure 1a). The specific process of rolling is to first keep the sample in a furnace at 300 ℃ for 30 minutes, and then carry out segmented rolling with deformation amounts of 10%, 10%, 20%, 20%, and 20%. The sample is returned to the furnace for insulation for 5 minutes between each rolling pass. All plates were solutionized (475℃/2h) and peak aged (T6:120℃/24h) after the final rolling process. The insulation during the rolling process and solid solution are carried out using aluminum alloy heat treatment furnace (RX-650-25). Its rated power, maximum heating temperature, and effective heating chamber size are 25KW, 650℃, and 400mm * 300mm * 300mm, respectively. The diameter of the upper and lower rollers of the rolling mill is the same, both of which are Φ100mm. The maximum rolling pressure is 200kN, and the roll speed is constant at 20r/min. The applicable temperature range for the aging furnace (WGL-65D) is 10℃ to 300℃, with a rated power of 1.6 kW and a temperature fluctuation of ± 1℃.

The microstructure of the material was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the proportion of related second phases is analyzed by Image Pro Plus software. The samples for SEM observation were polished step by step with water sandpaper, metallographic sandpaper, and diamond with a particle size of 1.0 μm until the surface of the sample is shiny and scratch free. And then the samples were observed on a TESCAN MIRA3 equipped with energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). The size distribution and characteristics of grains and subgrains were analyzed by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), step sizes of 0.2-4 μm. EBSD samples were prepared by electropolishing with a solution of 10% C2H5OH+90% HClO4 at -20 °C for 20-30 s at 20 V after mechanical polishing. The EBSD results were analyzed using channel 5 software. The testing of mechanical properties was carried out on a CMT5105 test machine at room temperature at a speed of 2 mm/min. Tensile specimens (40 mm × 6 mm) were cut along the RD direction from the sheet in the T6 state. Each sample must undergo at least three tensile tests to ensure reproducibility. The relevant data was plotted using Origin 2022 software.

3. Results

3.1. Second Phase Distribution After Rolling

Figure 2 is the SEM images of the second phase distribution of the rolled sheets. The results of EDS showed that the main second phase was mainly T phase and very few Al

7Cu

2Fe (as shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 2). From a statistical perspective, the content of Al

7Cu

2Fe relative to the content of T phase can be neglected. When the deformation of the plate is less than 20%, the second phase is distributed in a network structure (

Figure 2a,b,d,e), and the second phase between the grains begins to break gradually(

Figure 2c,f). When the reduction amount continued to increase to 60%, the reticular second phase gradually transformed into a fishbone distribution (

Figure 2g,h,j,k), and the degree of fragmentation of the second phase between grains intensified, and it tended to gradually separate into single second phase particles (

Figure 2i,l). When the reduction increases to 80%, the second phase of fishbone distribution disappears, replaced by meteor distribution along the RD direction (

Figure 2m,n), and the second phase particles are diffusely distributed(

Figure 2o).

3.2. Second Phase Distribution After Solution

After solution treatment at 475 °C/2 h for plates with different reduction, their overall distribution are similar to those after rolling but the volume fraction is greatly reduced (

Figure 1). As the amount of reduction increases, the remaining second phase increased slightly (from 1.09% to 1.40%), and the degree of overburning decreased significantly (from 1.20% to 0.07%,

Figure 4a,d,g,j,m and

Table 3). The above results lead to a general decreasing trend of the non-dissolved second phase with the increase of the reduction amount. As the rolling reduction increases, the second phase is broken into more dispersed and finer particles. Scholars[

19,

26] have explained the phenomenon that the finer phase has a higher degree of resolubility under the same solid solution conditions from the perspective of solute atom diffusion.

3.3. Recrystallization Differences After Solution

The recrystallization state of plates with different reductions after solid solution can be preliminarily analyzed from

Figure 5. With the intensification of deformation, the morphology of the grains changed obviously. Under the rolling force, the grains were gradually flattened and elongated, forming a fibrous structure distributed along the rolling direction. In the process of increasing the reduction from 10% to 80%, the aspect ratio of the overall grain increases from 1.85 to 4.49 (

Figure 5f and

Table 4). The degree of recrystallization of the alloy has been significantly improved (from 1.55% to 13.90%), which is mainly due to the continuous increase of the alloy’s storage energy during deformation, making it easier to recrystallize and promote the formation of fine grains during the solid solution process. The average grain size of the alloy also becomes smaller (from 38.27 μm to 9.04 μm). At the same time, many researchers[

27,

28,

29] have conducted detailed studies on Al-Zn-Mg Cu alloys containing Zr and Sc, and the results show that the formed Al

3 (Zr, Sc) precipitates can not only improve the strength of the alloy, but also hinder the further growth of fine grains.

Through the statistics of the fraction of low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs,

Figure 6), it can be found that with the increase of deformation, it first increases and then decreases(

Figure 6f). This is mainly attributable to the fact that the internal residual dislocations of the grains are retained more with the increase of strain, which leads to the continuous increase of the total amount of LAGBs. However, when the degree of deformation reaches 40%, the LAGBs have almost covered all the grains(

Figure 5c), and the total amount increases slightly in the subsequent deformation process from a statistical point of view, while the high-angle grain boundary (HAGBs) of the fine grains by recrystallization is increasing. As a result, the proportion of LAGBs evolves as described above.

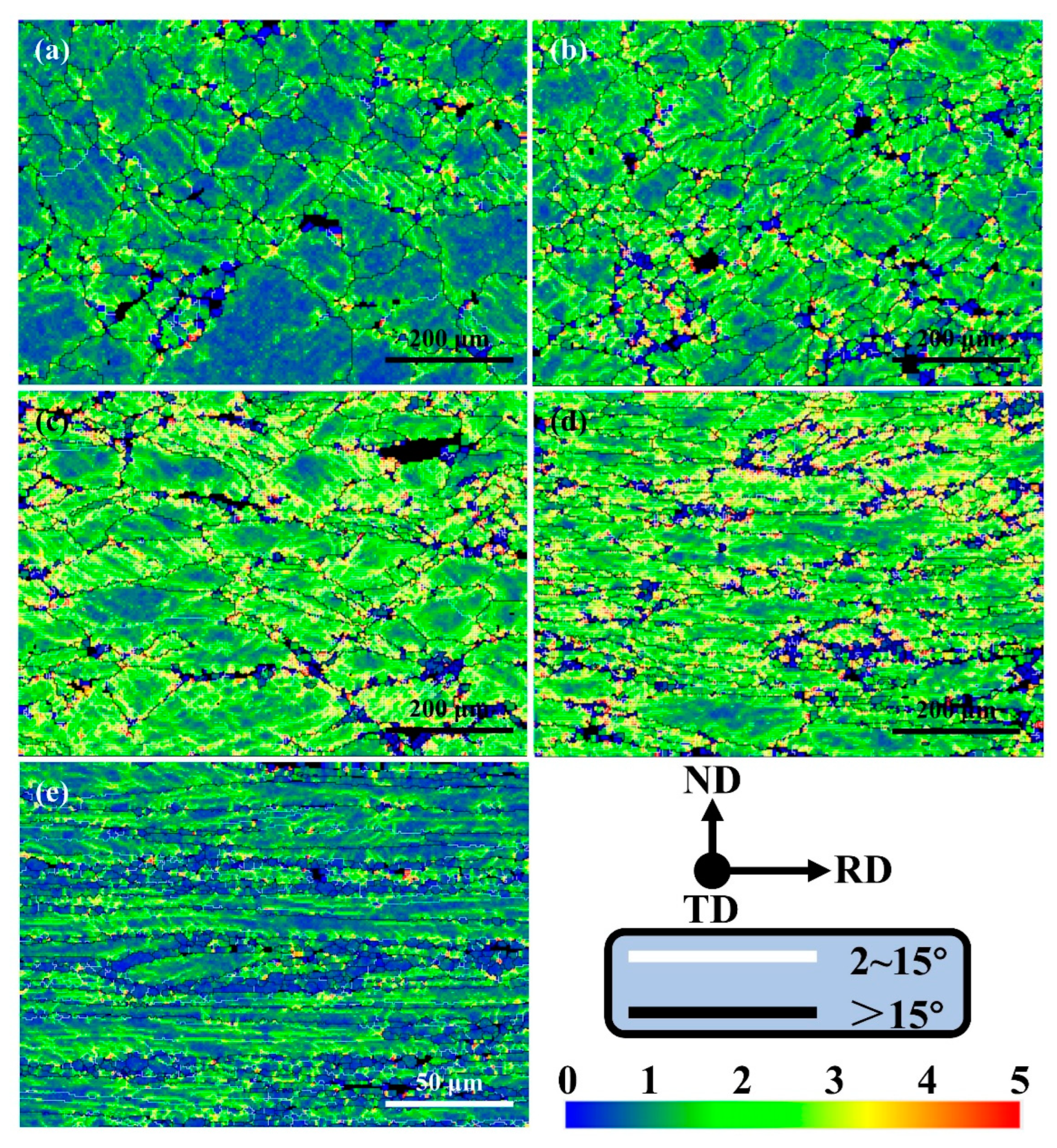

The Kernel average misorientation (KAM) diagram after solid solution with different rolling reductions can intuitively reflect the distribution of residual stress and stored energy, as shown in

Figure 7. The color bar in the KAM diagram changes from blue to green and then to red, indicating that the local misorientation increases from 0° to 5°. In order to observe the state of local misorientation near HAGBs and LAGBs more conveniently, they are marked with black and white lines in the KAM maps, respectively. It can be seen from

Figure 7 that, regardless of the degree of deformation, the interior of the fine recrystallized grains is dark blue, indicating that the internal energy storage of the small grains is close to zero. The recrystallization process in the solid solution process consumes the dislocations around it, which will reduce the local misorientation. With the increase of the degree of deformation, the number of dark blue fine grains increases, which also indicates the increase of the degree of recrystallization.

Generally, the interior of the large grains is light blue, while the grain boundaries appear green, yellow or even red, which indicates that dislocations are more likely to accumulate near the HAGBs during the previous rolling process. In addition, the colors near the deformation zone inside the grains are mainly yellow and green, and gradually transition from green to yellow and red with the increase of rolling reduction, which indicates that a higher degree of deformation is more conducive to the accumulation of dislocations near the deformation zone.

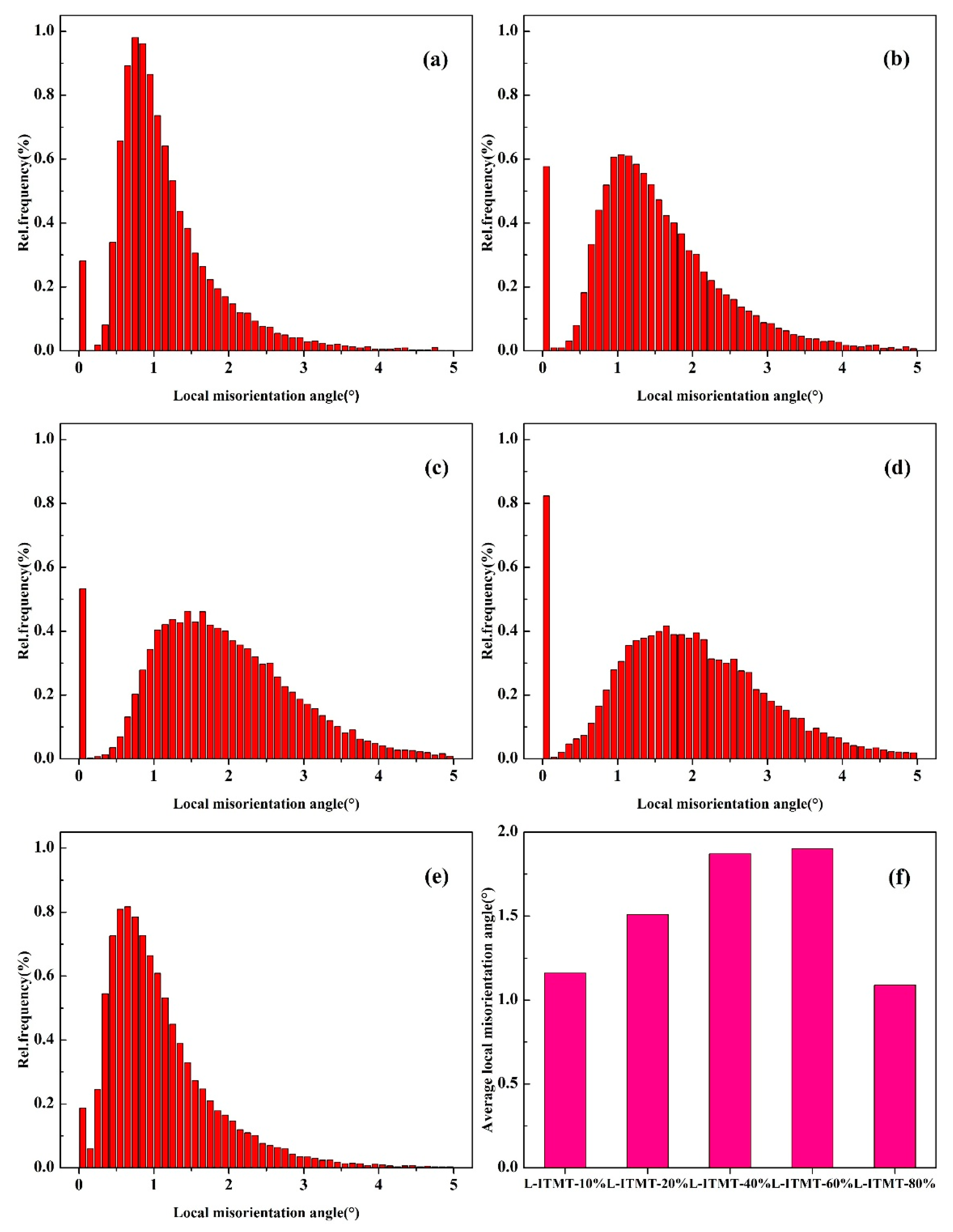

As the rolling reduction increases from 10% to 60%, the proportions of green, yellow, and red increase (

Figure 7a–d). It can be observed that the peaks in the local misorientation diagram are gradually shifting to higher angles (

Figure 8a–d), and the statistical results show that the average value increases from 1.16 to 1.90 (

Figure 8f). When the reduction continues to increase to 80%, the KAM map generally returns to the blue-green distribution (

Figure 7e), and the statistical results also show that the average local misorientation decreases to 1.09 (

Figure 8e,f). This indicates that the dislocations accumulated in the rolling process undergo a more complete recrystallization during the solid solution process, and transform into more fine recrystallized grains with low dislocation density. Therefore, it can be considered that when the deformation reduction is less than 60%, the alloy is mainly based on the recovery mechanism. And when the deformation reduction exceeds 80%, the recrystallization is the main mechanism.

3.4. Mechanical Properties After Thermo-Mechanical Treatment

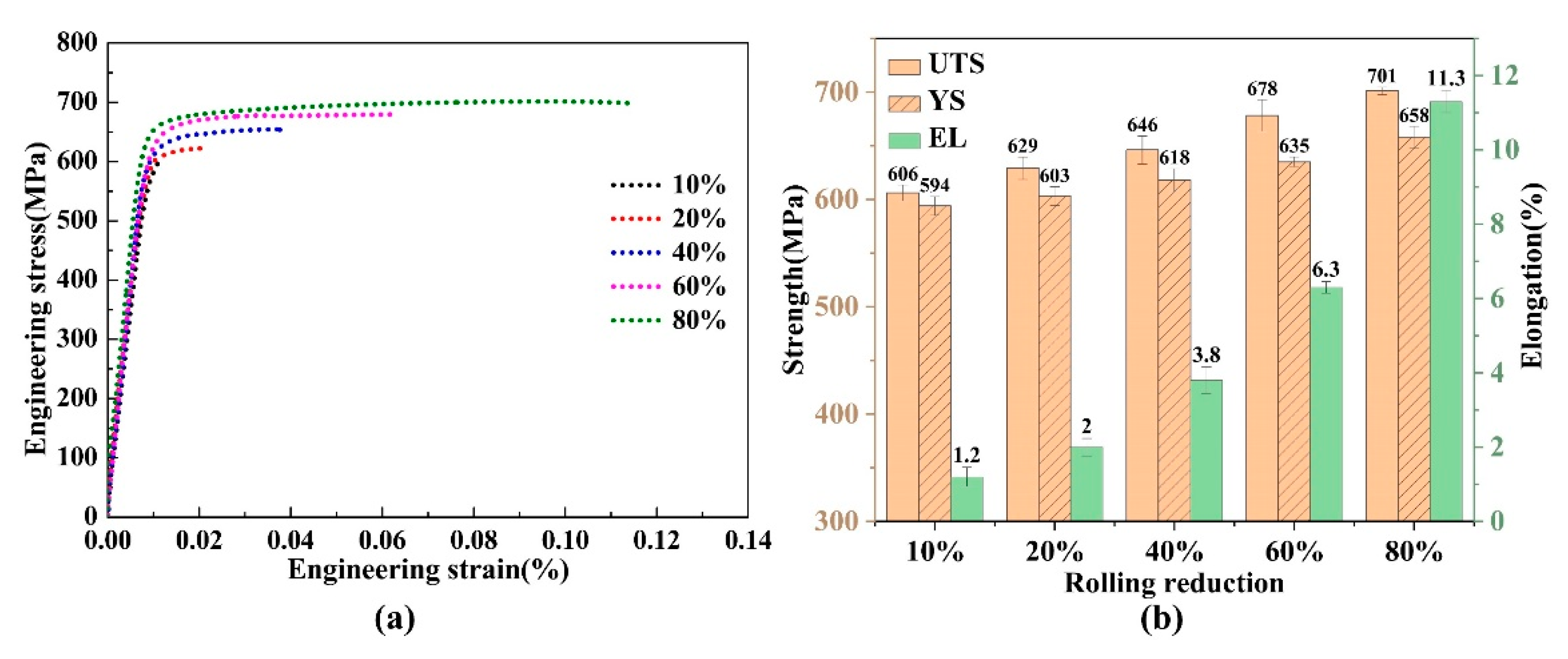

Figure 9a,b shows the strain-stress curves and corresponding mechanical properties of the final state under different degrees of deformation in the L-ITMT process. During the process of increasing the deformation degree from 10% to 20%, the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of the board increased from 606 MPa to 629 MPa, the yield strength (YS) increased from 594 MPa to 603 MPa, and the elongation (EL) increased significantly from 1.2% to 2.0%. Under moderate deformation conditions of 40% and 60%, the comprehensive mechanical properties of the board have been further improved. Their UTS are 646MPa and 678MPa, YS are 618MPa and 635MPa, and EL are 3.8% and 6.3%, respectively. When the recrystallization mechanism undergoes a transformation (as described in

Section 3.3), that is, when the degree of deformation reaches 80%, the UTS and YS of the alloy increase to 701 MPa and 658 MPa, respectively, while the EL increases significantly to 11.3%.

In a word, as the deformation degree increased from 10% to 80%, the short-flow TMT process increased the UTS, YS, and EL of the alloy by 15.7%, 10.8%, and 842%, respectively.

4. Discussion

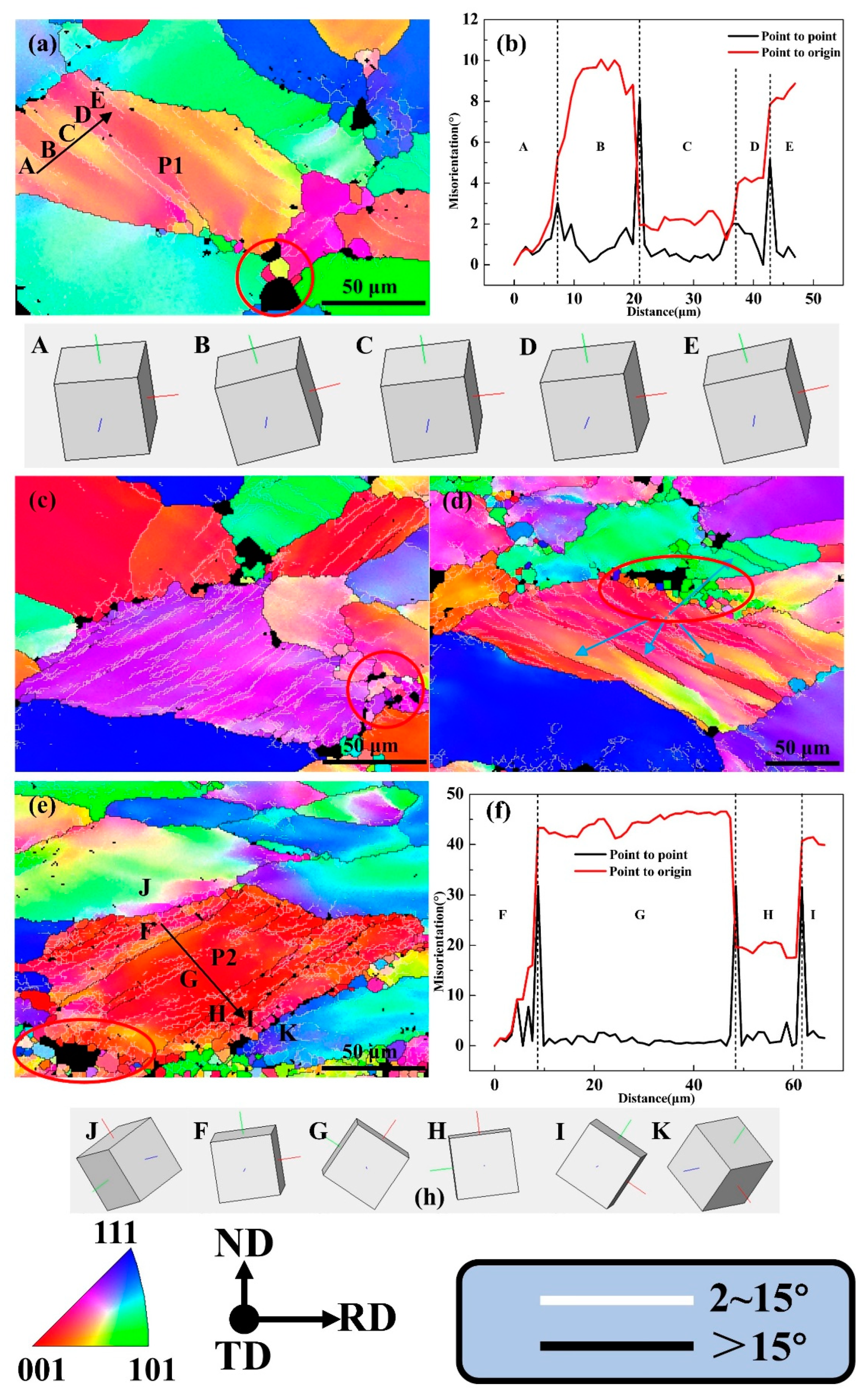

4.1. The Formation and Development of the Deformation Bonds

Due to the inhomogeneous stress transmitted by adjacent grains or the inherent instability of grains during plastic deformation, individual grains in the alloy are massively subdivided into domains with different orientations during deformation. The deformed bands are partially retained during the solid solution process. As shown in

Figure 5a, When the deformation is only 10%, obvious deformation bands composed of parallel LAGBs have been formed inside a few grains. An enlarged view of one of the grains G1 containing deformation bands is shown in

Figure 10a. By analyzing the misorientation of point to point and point to origin from region A to region E, it can be concluded that the misorientation of different deformation zone regions is less than 10° (

Figure 10b). In addition, the orientation of each region can be intuitively observed through the Euler angles of regions A-E. The orientations of regions A and C, B and E are very close, which indicates that the applied strain is accommodated by a set of slip systems, and each region rotates at a small angle.

When the degree of deformation increases to 20%, deformation bands composed of LAGBs can be observed in about half of the grains (

Figure 5b). And when the degree of deformation increases to more than 40%, the deformation band covers almost all the grains (

Figure 5c–e), which shows that the increase of strain is very conducive to the formation of deformation band. When the degree of deformation reaches 40%, some deformation bands composed of HAGBs can be clearly observed inside the grains, as shown in the position marked by the blue arrow in

Figure 10d. When the rolling reduction continues to increase to 60%, a HAGB deformation zone running through the grains can be observed, and the original grain P2 is divided into several new grains with higher aspect ratios (

Figure 10e). This is also one of the important reasons for the decrease of the average grain size and the increase of grain aspect ratio with the increase of strain.

The following two points can prove that the F-I regions are new grains formed by shearing and originally belonged to the grain P2. First, the analysis of the adjacent misorientation and cumulative misorientation of the region F to region I (

Figure 10f) shows that the misorientation of the two adjacent regions is higher than 20°, and the misorientation of the F and G regions even reaches 50°. They all belong to HAGBs, which can be considered as the formation of new grains. Second, although the F, G, H, and I regions inside P2 have large orientation differences, their orientation is <111>//TD. It can be considered that the internal deformation bands of P2 grain are torsion to a large extent under the action of shearing. At the same time, the orientations of the J region adjacent to the F region and the K region adjacent to the I are <123>//TD and <112>//TD, which are completely different from the orientations of the F~I regions. Therefore, it is concluded that the new grains F~I belong to the original grain P2.

When the degree of deformation continues to increase to 80%, the deformation band also continues to elongate along with the grain, and the direction is almost parallel to the RD direction (

Figure 5e). We will discuss how the elongated deformation bands affect the recrystallization to form fine grains in the subsequent subsections.

4.2. Geometric Recrystallization

When the degree of deformation gradually increases, the width of the deformed grains or bands in the ND direction gradually decreases to the size close to that of a single subgrain after rolling. Subsequent small grain boundary movements can result in fine grains surrounded by HAGBs. Such fine grains have no clearly identifiable “nucleation” and “growth” stages, and uniform evolution in the local structure of the material, which can be classified as continuous recrystallization(CRX) or geometric recrystallization (GRX).

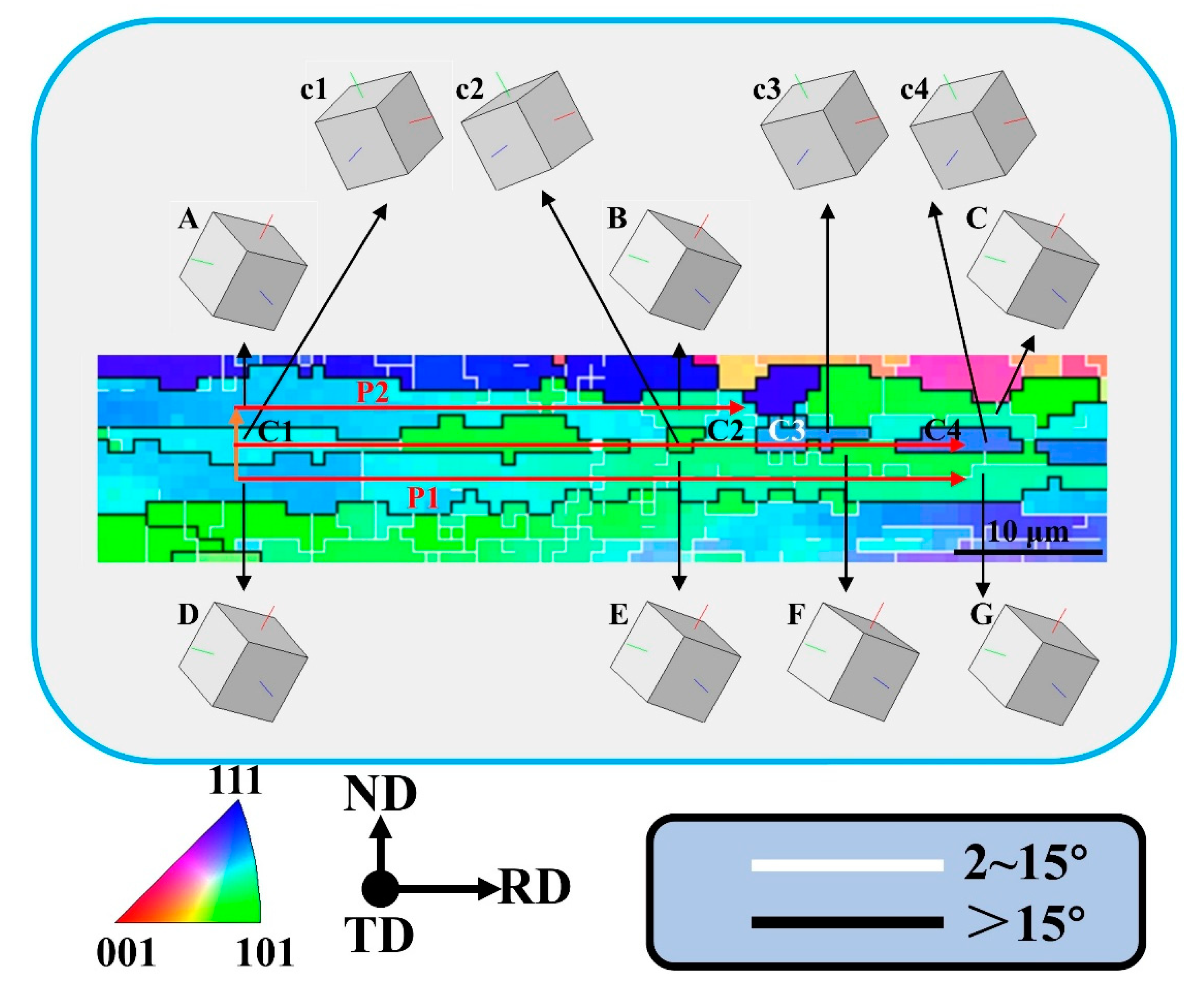

As shown in

Figure 5e, f and

Table 4, when the rolling reduction reaches 80%, the average aspect ratio of grains reaches 4.49, which meets the conditions (aspect ratio greater than 4) for GRX[

30]. And this phenomenon was observed in many areas of its microstructure, as shown in the A1~A3 area in

Figure 5e. As mentioned in

Section 3.1, the deformed bands with HAGBs formed by shearing are almost distributed along the RD direction at a rolling reduction of 80%. And the width along the ND direction is about 2 μm (

Figure 2), which is very close to the grain size of a single subgrain. The orientations of the P2 region (position A~C) and the P1 region (position D~G) are very close in terms of cubic lattice (

Figure 2), and the point-to-point difference and point to origin difference do not exceed 9°(

Figure 12a,b), which indicates that both P1 and P2 regions belong to an original grain (named grain P). The point-to-point misorientation and point-to-origin misorientation from the D area to the A area indicate that the misorientation of C1, P1 and P2 is 60°(

Figure 12c), but the orientations of all three are <123>//TD. Therefore C1 was originally part of the deformation band formed inside the grain P.

Figure 12d shows that the misorientation between C1~C4 grains is less than 10°, and it can be more clearly observed that their orientations are very close from the orientations c1~c4 represented by their cubic lattice. They originally belonged to the same deformation band during the deformation process, and the grain boundaries were twisted at a small angle during the solid solution process to form new grains with close orientations. Therefore, the fine C2~C4 grains distributed along the RD direction can be considered as the final result of the development of the original elongated deformation band through GRX.

4.3. Discontinuous Recrystallization

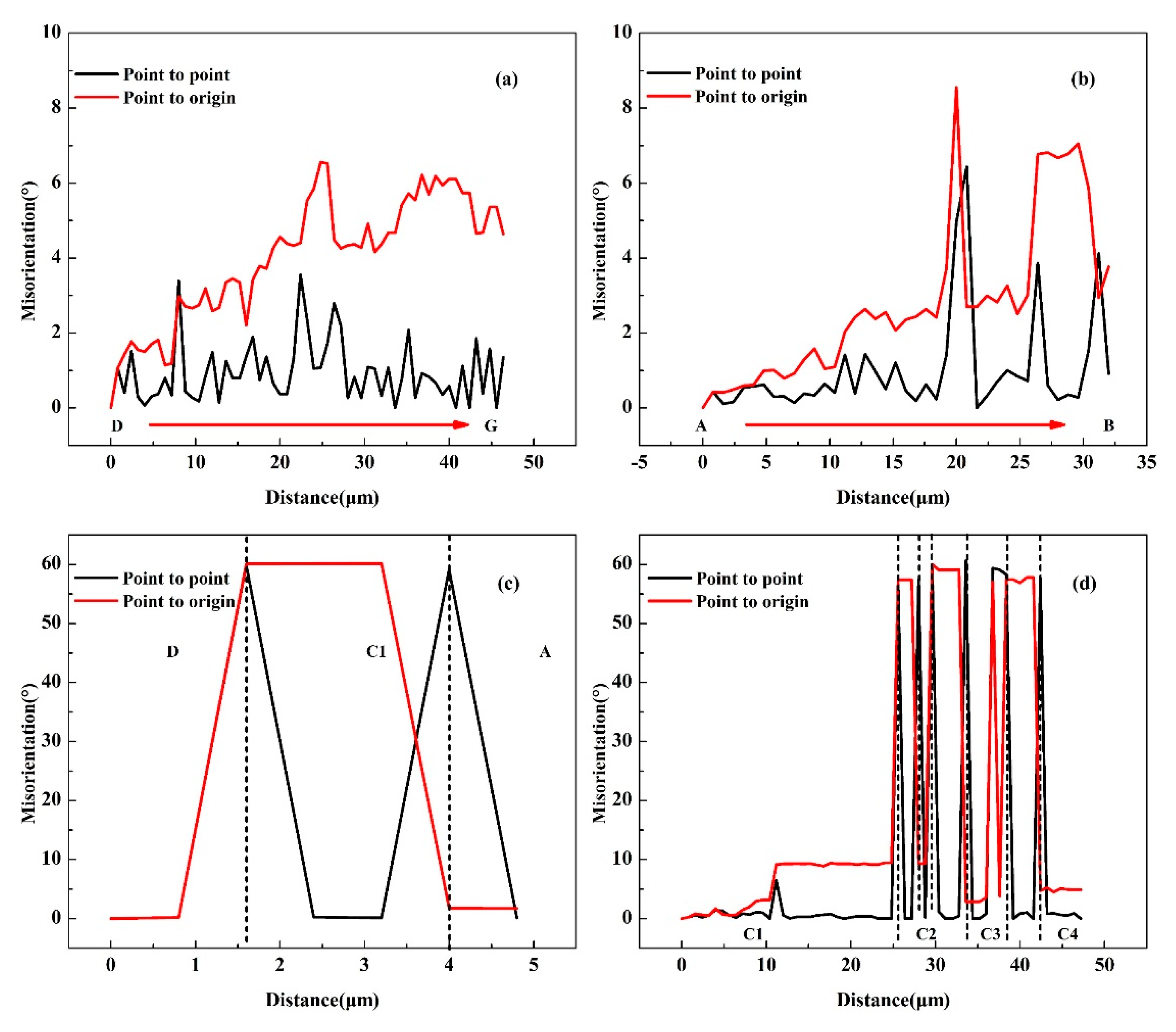

The variation of orientation misorientation along the RD direction of P1 grains is shown in the

Figure 13a,b. The point-to-point misorientation is less than 3°, and the point-to-point initial misorientation does not exceed 4°, which indicates that the residual dislocation energy storage of P1 grains after solid solution is very low . The orientations of the D1, D2, and D3 grains at the grain boundary represented by the cubic lattice are very close, and a large-angle rotation occurs compared with the P1 grain below. Due to their symmetry, the orientations of recrystallized grains D1~D3 and P1 grains are all similar to <123>//TD directions. This indicates the presence of another recrystallization mechanism, discontinuous recrystallization (DRX), during the solution process after 80% rolling reduction. This mechanism is different from the randomly oriented recrystallized grains induced by CRX, DRX usually occurs near HAGBs, and its typical feature is induced by irregular zigzag grain boundary migration. With the further development of the migration, the grain boundary bows out, and finally the DRX fine grains with no internal dislocation energy storage are formed. The point-to-origin misorientation changes along the ND direction passing through the D1 grains are shown in

Figure 13c. The misorientations between P2 and D1, D1 and P1, and P2 and P1 grains are about 20°, 25°, 45°. This shows that the misorientation is gradient along P1 to P2, which is the key to cause D1 grains to bows and nucleate from P1 to P2.

4.4. Particles Stimulate Nucleation

Several studies[

19,

23] have shown that large particles can act as preferential nucleation sites, which are well known as particle stimulated nucleation (PSN). In this study, it can be observed that the gradual increase in deformation has an impact on the PSN, as shown in

Figure 10. When the deformation degree is only 10%, a small number of recrystallized grains can be observed around large particles after solid solution, as shown in the position marked with a red circle in

Figure 10a. This shows that even under low strain, dislocations can be effectively pinned around the particles and PSN occurs during the subsequent solid solution process, resulting in a small amount of recrystallized grains. As the degree of deformation increases, the accumulated dislocation energy storage around the second phase increases, which increases the number of sites where PSN occurs (as shown in

Figure 5a–e) and the number of recrystallized grains around coarse particles increases significantly, as shown in

Figure 9a,c,d,e. This indicates that increased strain or increased energy storage can promote the generation of PSN.

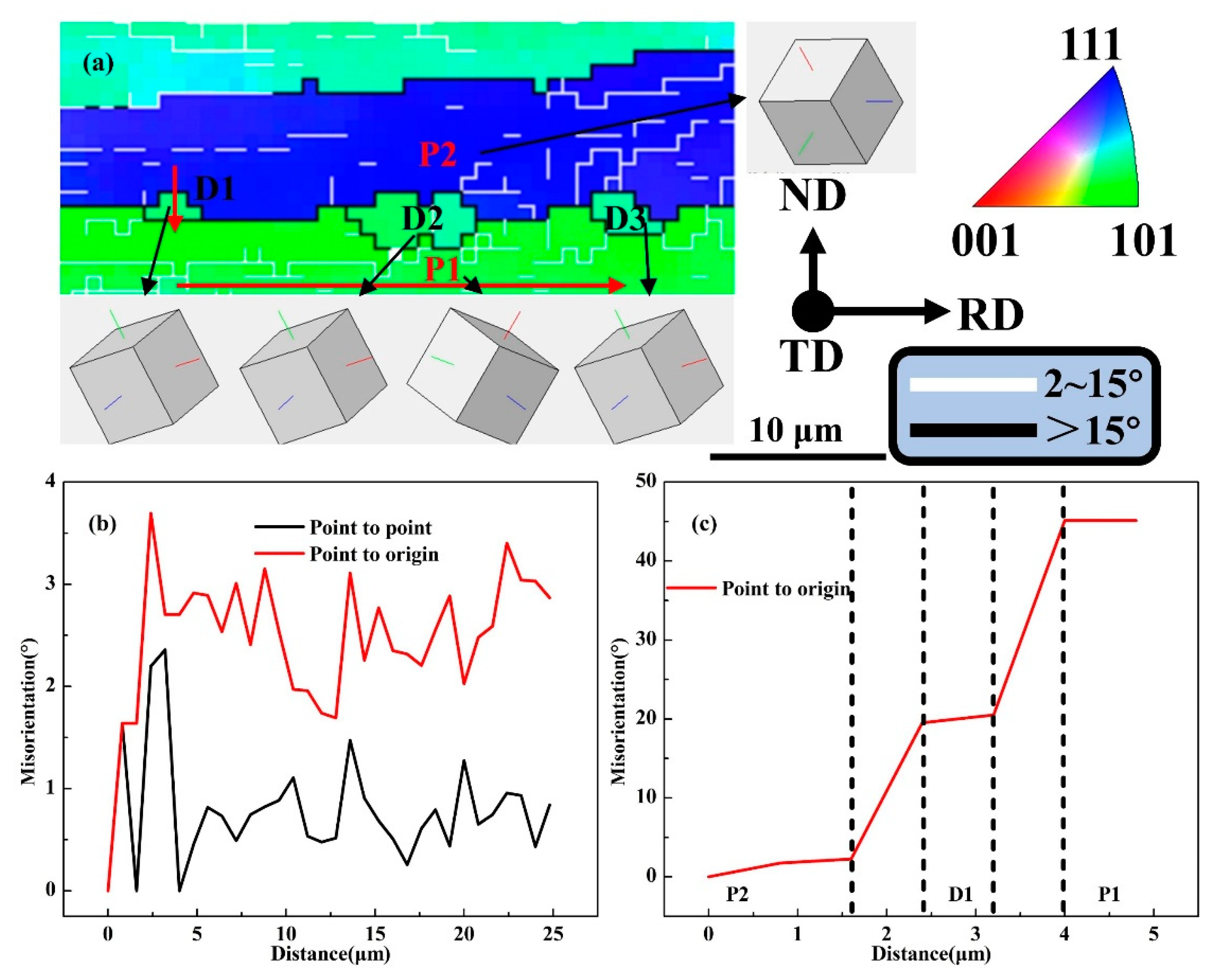

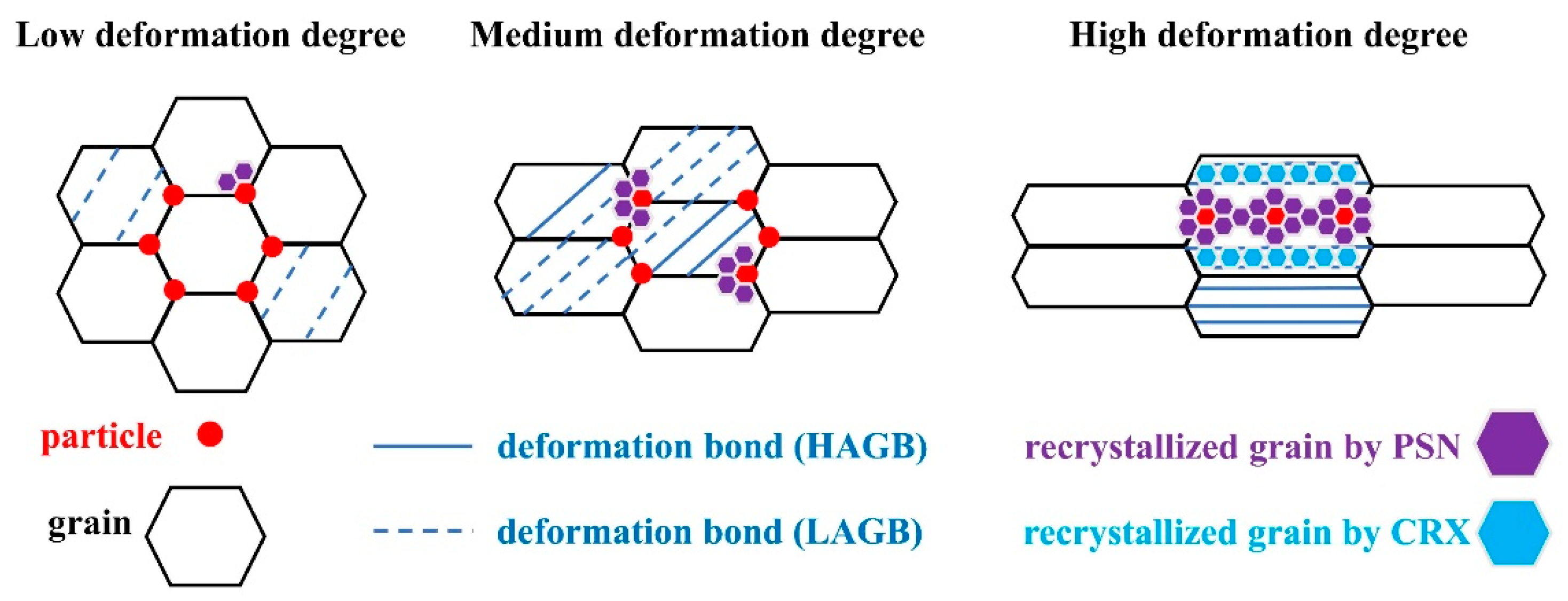

4.5. Formation of Fine-Grained Bands

Under the condition of rolling reduction of 80%, obvious fine-grained bands were formed in the middle area of

Figure 5e, while no obvious fine-grained bands were observed within 60% reduction. This indicates that the primary need for producing fine-grained bands is under high strain or high energy storage.

Figure 14 shows a local enlargement of the fine-grained region in

Figure 5e, where multiple coarse particles are found around the fine grain band. The cubic lattice orientation of the fine grains P1~P7 around the coarse particle S1 is quite different, which is due to the fact that the coarse particle S1 produces randomly oriented fine grains through the PSN effect during the solution process. This is one of the characteristics of formation of the fine-grained bands. On the other hand, the orientations of the C1~C4 grains distributed along the RD direction around particle S1 are not completely consistent, but their orientations are approximately <001>//TD direction. This indicates that they are formed through the twisting of deformation bands and belong to the continuous recrystallization mechanism. Coarse particles can also increase the formation rate of high angle grain boundaries by disrupting the flatness of grain boundaries, and establish new high angle grain boundaries by rotating the lattice around the coarse particles. This will reduce the width of the surrounding large grains or deformation bands extending in the ND direction, making narrow grains or deformation bands near the particles more prone to continuous recrystallization during the solid solution process.

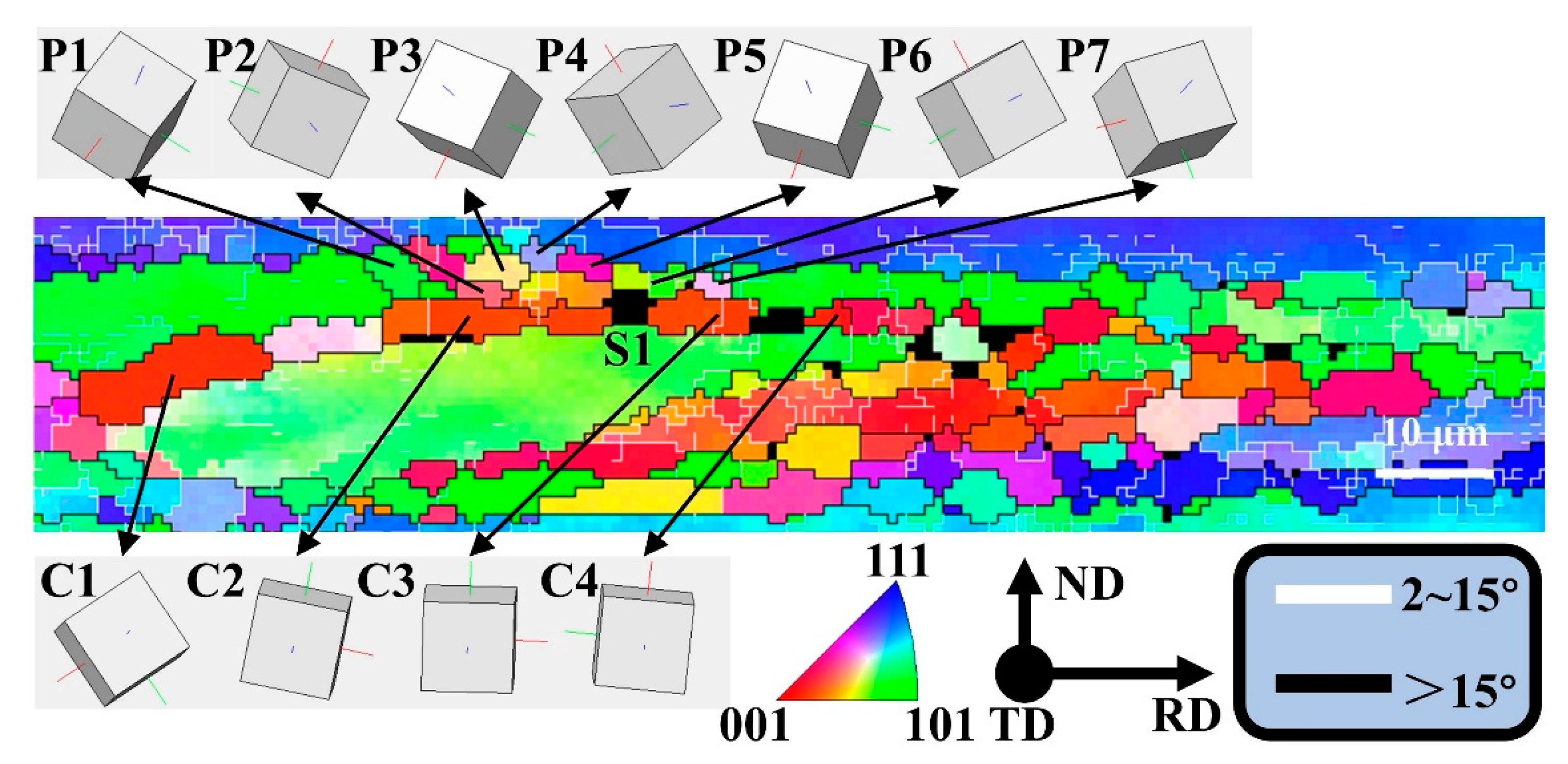

In summary, fine grain bands can be considered to be caused by the PSN effect of multiple adjacent coarse particles and the fine grains distributed in the RD direction generated by the continuous recrystallization mechanism (as shown in

Figure 15).

4.6. Effect of Microstructure on Mechanical Properties

As the deformation degree increases, the overburned second phase decreases and the dissolved second phase increases under the same solid solution conditions (as shown in

Figure 4). Therefore, the matrix solid solubility is higher, which is beneficial to the subsequent aging precipitation strengthening.

In addition, as the deformation of the plate increases, the PSN effect becomes more significant. At the same time, the continuous recrystallized grains produced in the process of narrowing of the deformation bands increase. The combination of the two mechanism eventually forms a large-area fine-grained zone (as shown in

Figure 15), resulting in a significant reduction in the average grain size (from 38.27 μm to 9.04 μm, statistics of

Table 4). Many researchers[

31,

32,

33] have demonstrated the benefits of grain refinement in improving ductility, as more uniform slip can occur and more dislocations can be stored in the fine grain structure, thereby promoting higher strain hardening ability to delay fracture and increase elongation.

5. Conclusions

(1) Increasing the rolling deformation from 10% to 80% during the short-flow thermo-mechanical treatment(TMT) process can effectively break up the second phase at the grain boundary, which effectively reduces the overburned second phase from 1.20% to 0.07% during the solid solution process. At the same time, the amount of dissolved second phase increases by 0.82%, which is very beneficial to the subsequent aging precipitation strengthening and improves the strength of the alloy.

(2) Based on the comprehensive analysis of grain size, kernel average misorientation (KAM) diagram, and recrystallization volume fraction, it is concluded that when the deformation amount of L-ITMT process reaches 60%, the dominant mechanism changes from recovery to recrystallization.

(3) During the process of increasing the deformation degree from 10% to 80%, the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of the board increased from 606 MPa to 701 MPa, the yield strength (YS) increased from 594 MPa to 658 MPa, and the elongation (EL) increased significantly from 1.2% to 11.3%.

(4) As the deformation increases, the deformation bands gradually transform from LAGBs to HAGBs and becomes flat. when the rolling reduction reaches 80%, the average aspect ratio of grains reaches 4.49 (the deformation band is nearly parallel to the RD direction and have a higher aspect ratio), which promotes the conditions for geometric recrystallization (GRX) or continuous recrystallization (CRX).

(5) The particle stimulated nucleation(PSN) effect can be observed at a deformation degree of 10% and becomes more significant with increasing strain. When the degree of deformation reaches 80%, PSN effect is the main contributor to fine grains.

(6) Under high strain conditions, the formation of recrystallized grains includes three mechanisms: discontinuous recrystallization(DRX), CRX and PSN, but the main contribution to the formation of large-area fine-grained bands is CRX and PSN. This effectively reduces the average grain size (from 38.27 μm to 9.04 μm) of the alloy, slightly increases the strength of the alloy, and greatly improves the plasticity of the alloy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hao Li; Data curation, Junhua Cheng; Formal analysis, Hao Li; Funding acquisition, Yu Liu; Investigation, Hao Li and Junhua Cheng; Methodology, Hao Li and Yongxing Zhao; Project administration, Hao Li and Yuanchun Huang; Software, Hao Li and Yongxing Zhao; Supervision, Yu Liu; Visualization, Yuanchun Huang and Yu Liu; Writing – original draft, Hao Li; Writing – review & editing, Hao Li.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52205433), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2022JJ40608).

References

- Wang, J.; Li, F.G. Research Status and Prospective Properties of the Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Series Aluminum Alloys. Metals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, T.; Soutis, C. Recent developments in advanced aircraft aluminium alloys. Materials & Design (1980-2015) 2014, 56, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.C.; Starke, E.A. Progress in structural materials for aerospace systems11The Golden Jubilee Issue—Selected topics in Materials Science and Engineering: Past, Present and Future, edited by S. Suresh. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 5775–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Zhao, Z.H.; Wang, G.S.; Qin, G.W. Effect of the over-aging degree on high cycle fatigue properties of an ultra-high strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2024, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.N.; Zhu, S.Z.; Wang, D.; Xue, P.; Xiao, B.L.; Ma, Z.Y. Effect of heat treatment on the microstructure, mechanical properties and fracture behaviors of ultra-high-strength SiC/Al-Zn-Mg-Cu composites. International Journal of Minerals Metallurgy and Materials 2024, 31, 2233–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Pan, Q.L.; Wang, X.D.; Han, M.X.; Liu, B.; Sun, Y.W.; Liu, X.F. Achieving high strength and ductility of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys via laser shock peening and spray forming. Materials Characterization 2024, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavatskikh, M.V.; Gorlov, L.E.; Loginova, I.S.; Barkov, R.Y.; Khomutov, M.G.; Churyumov, A.Y.; Pozdniakov, A.V. Effect of Er on the Hot Deformation Behavior of the Crossover Al3Zn3Mg3Cu0. 2Zr Alloy. 2024, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Liu, Y.Z.; Zhou, Z.G.; Zhan, Q.K. Enhanced strength and ductility in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys fabricated by laser powder b e d fusion using a synergistic grain-refining strategy. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2022, 124, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Ren, X.L.; Chen, S.J.; Jiang, X.Q. Grain refinement and property improvements of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy by heterogeneous particle addition during wire and arc additive manufacturing. Journal of Materials Research and Technology-Jmr&T 2022, 16, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.S.; Xu, S.K.; Wan, T.J.; Liu, H.T.; Xie, L.L.; Zhang, M.Y.; Li, J.H. Effect of intermediate-temperature severe plastic deformation on microstructure evolution, mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Materials Characterization 2023, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, G.; Wang, Y.B.; Liao, X.Z.; Duan, Z.C.; Ringer, S.P.; Langdon, T.G. Influence of equal-channel angular pressing on precipitation in an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 3123–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; García-Infanta, J.M.; Rauch, E.F.; Blandin, J.J.; Ruano, O.A.; Carreño, F. Influence of Processing Severity During Equal-Channel Angular Pressing on the Microstructure of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A-Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2012, 43A, 4224–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tang, J.; Mo, X.D.; Chen, W.T.; Fu, D.F.; Zhang, H.; Teng, J.; Jiang, F.L. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and strengthening mechanisms of ultra-high strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy prepared by continuous extrusion forming process. Mater. Des. 2024, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, W.T.; Jiang, F.L.; Chen, Y.G.; Zhang, H.; Teng, J. Deformation mechanisms and mechanical properties of the high-strength and ductile Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys processed by repetitive continuous extrusion forming process with different heat treatments. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markushev, M.V.; Avtokratova, E.V.; Krymskiy, S.V.; Sitdikov, O.S. Effect of precipitates on nanostructuring and strengthening of high-strength aluminum alloys under high pressure torsion. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 743, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Chen, X.P.; Ren, P.; Nie, Y.Y.; Huang, G.J.; Liu, Q. Effect of warm deformation on precipitation and mechanical properties of a cryorolled Al-Zn-Mg-Cu sheet. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2020, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Yang, M.J.; Chen, X.P.; Jin, Q.Q.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, Y.M. Precipitate evolution and properties of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy processed by thermomechanical treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2023, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Prasad, K.S. Superplastic behaviour of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr alloy AA7010 containing Sc. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2010, 527, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.T.; Shi, J.T.; Hou, L.G.; Zhang, J.S. An improved thermo-mechanical treatment of high-strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy for effective grain refinement and ductility modification. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2017, 239, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, X.Q.; He, J.Y.; Huang, D.N.; Rahimov, R.V.; Mansurov, Y.N.; Wang, Z.W.; Song, M. Superb mechanical properties of a novel high-Zn Al alloy processed via two-step thermomechanical treatments. Materials Letters 2024, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Russo, E.; Conserva, M.; Buratti, M.; Gatto, F. A new thermo-mechanical procedure for improving the ductility and toughness of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys in the transverse directions. Materials Science and Engineering 1974, 14, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, J.; Sulinski, H.; Markus, H. EFFECT OF INGOT PROCESSING TREATMENTS ON THE GRAIN SIZE AND PROPERTIES OF Al ALLOY 7075. Metall Trans 1974, 5, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wert, J.A.; Paton, N.E.; Hamilton, C.H.; Mahoney, M.W. GRAIN REFINEMENT IN 7075 ALUMINUM BY THERMOMECHANICAL PROCESSING. Metallurgical transactions. A, Physical metallurgy and materials science 1981, 12 A, 1267-1276. [CrossRef]

- Málek, P.; Cieslar, M. The influence of processing route on the plastic deformation of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2002, 324, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Prasad, K.S. Superplastic Behavior of a High-Strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr Alloy. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2009, 40, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, A.; Fribourg, G.; Bréchet, Y.; Chemin, J.L.; Hutchinson, C.R. In situ evaluation of dynamic precipitation during plastic straining of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Pan, Q.L.; He, Y.B.; Wang, C.Z.; Liang, W.J. Effect of minor Sc and Zr addition on microstructures and mechanical properties of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2007, 17, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.B.; Pan, Q.L.; Zou, L.; Liang, W.J.; He, Y.B.; Liu, J.S. Effects of minor Sc on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Zr based alloys. Rare Metals 2009, 28, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Pan, Q.L.; Liu, B.; Hu, Q.; Qu, L.F.; Wang, W.Y.; Wang, X.D. Effects of co-addition of minor Sc and Zr on aging precipitates and mechanical properties of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloys. Journal of Materials Research and Technology-Jmr&T 2023, 22, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, M.R.; Humphreys, F.J.J.A.M. The development of microstructure in Al-5% Mg during high temperature deformation. 1986, 34, 2259–2271. [CrossRef]

- Alauddin, M.; El Baradie, M.A.; Hashmi, M.S.J. Optimization of surface finish in end milling Inconel 718. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 1996, 56, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlinde, G.; Luetjering, G. Influence of Grain Size and Age-Hardening on Dislocation Pile-Ups and Tensile Fracture for a Ti-AI Alloy. Metallurgical Transactions A 1982, 13, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloborodko, A.; Ito, T.; Yun, X.; Motohashi, Y.; Itoh, G. Friction Stir Welding of a Commercial 7075-T6 Aluminum Alloy: Grain Refinement, Thermal Stability and Tensile Properties. MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS 2004, 45, 2503–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

a) The state of the plates after rolling and (b) schematic diagram of short-flow TMT process.

Figure 1.

a) The state of the plates after rolling and (b) schematic diagram of short-flow TMT process.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the second phase of plates with different reduction after rolling: (a,b,c) 10%; (d,e,f) 20%; (g,h,i) 40%; (j,k,l) 60%; (m,n,o) 80%.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the second phase of plates with different reduction after rolling: (a,b,c) 10%; (d,e,f) 20%; (g,h,i) 40%; (j,k,l) 60%; (m,n,o) 80%.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the second phase of plates with different reduction after solution: (a,b,c) 10%; (d,e,f) 20%; (g,h,i) 40%; (j,k,l) 60%; (m,n,o) 80%.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the second phase of plates with different reduction after solution: (a,b,c) 10%; (d,e,f) 20%; (g,h,i) 40%; (j,k,l) 60%; (m,n,o) 80%.

Figure 5.

EBSD-IPF maps after solid solution with different rolling reduction: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%; (f) Statistics of recrystallized volume fraction, average grain size and aspect ratio.

Figure 5.

EBSD-IPF maps after solid solution with different rolling reduction: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%; (f) Statistics of recrystallized volume fraction, average grain size and aspect ratio.

Figure 6.

Misorientation distribution of different rolling reductions after solid solution: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%; (f) Statistics of fraction of low(high)-angle grain boundaries.

Figure 6.

Misorientation distribution of different rolling reductions after solid solution: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%; (f) Statistics of fraction of low(high)-angle grain boundaries.

Figure 7.

KAM maps after solid solution with different rolling reduction: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%.

Figure 7.

KAM maps after solid solution with different rolling reduction: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%.

Figure 8.

Local misorientation distribution after solid solution with different rolling reduction: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%; (f) Average Local misorientation.

Figure 8.

Local misorientation distribution after solid solution with different rolling reduction: (a) 10%; (b) 20%; (c) 40%; (d) 60%; (e) 80%; (f) Average Local misorientation.

Figure 9.

a) Stress-strain curve and (b) mechanical property after L-ITMT.

Figure 9.

a) Stress-strain curve and (b) mechanical property after L-ITMT.

Figure 10.

Enlarged view of local area in

Figure 5 and misorientation variation along the direction of the arrow:(a) local area in

Figure 5a; (b) misorientation variation of (a); (c) local area in

Figure 5b; (d) local area in

Figure 5c; (e) local area in

Figure 5d; (f) misorientation variation of (e).

Figure 10.

Enlarged view of local area in

Figure 5 and misorientation variation along the direction of the arrow:(a) local area in

Figure 5a; (b) misorientation variation of (a); (c) local area in

Figure 5b; (d) local area in

Figure 5c; (e) local area in

Figure 5d; (f) misorientation variation of (e).

Figure 12.

Misorientation along the arrow direction in

Figure 2: (a) Area D to Area G; (b) Area A to Area B; (c) Area D to Area A; (d) Area C1 to Area C4.

Figure 12.

Misorientation along the arrow direction in

Figure 2: (a) Area D to Area G; (b) Area A to Area B; (c) Area D to Area A; (d) Area C1 to Area C4.

Figure 13.

a)Local area in

Figure 5e, (b) misorientation in the direction of the red arrow inside the P1 grain and (c)misorientation through D1 in the direction of the red arrow.

Figure 13.

a)Local area in

Figure 5e, (b) misorientation in the direction of the red arrow inside the P1 grain and (c)misorientation through D1 in the direction of the red arrow.

Figure 14.

Enlarged view of the fine-grained band area in

Figure 5e.

Figure 14.

Enlarged view of the fine-grained band area in

Figure 5e.

Figure 15.

Formation mechanism of fine-grained bands.

Figure 15.

Formation mechanism of fine-grained bands.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of Al-10.0Zn-2.7Mg-2.3Cu-0.11Zr-0.12Sc (wt%).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of Al-10.0Zn-2.7Mg-2.3Cu-0.11Zr-0.12Sc (wt%).

| Element |

Zn |

Mg |

Cu |

Zr |

Sc |

Al |

| wt% |

10.09 |

2.73 |

2.28 |

0.11 |

0.12 |

Bal |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the phases in

Figure 2(at%).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the phases in

Figure 2(at%).

| Point |

Al |

Cu |

Zn |

Mg |

Fe |

Identified phase |

| 1 |

39.19 |

13.35 |

21.07 |

26.39 |

0.00 |

T |

| 2 |

39.72 |

12.78 |

24.63 |

22.87 |

0.00 |

T |

| 3 |

35.66 |

14.09 |

22.71 |

27.54 |

0.00 |

T |

| 4 |

31.35 |

7.24 |

28.96 |

32.45 |

0.00 |

T |

| 5 |

36.45 |

9.81 |

28.39 |

25.35 |

0.00 |

T |

| 6 |

72.51 |

13.41 |

4.96 |

3.78 |

5.34 |

Al7Cu2Fe |

Table 3.

Statistics of the second phase volume fraction after solid solution of plates with different reductions (%).

Table 3.

Statistics of the second phase volume fraction after solid solution of plates with different reductions (%).

| Reduction |

Remaining second phase |

Burnt second phase |

Undissolved second phase |

| 10% |

1.09 |

1.20 |

2.29 |

| 20% |

1.23 |

0.75 |

1.98 |

| 40% |

1.34 |

0.49 |

1.83 |

| 60% |

1.39 |

0.27 |

1.68 |

| 80% |

1.40 |

0.07 |

1.47 |

Table 4.

Statistics of recrystallization volume fraction (VFRx), aspect ratio, fraction of low-angle grain boundaries (FLAGBs), fraction of high-angle grain boundaries (FHAGBs), and average grain size under different rolling reductions after solid solution.

Table 4.

Statistics of recrystallization volume fraction (VFRx), aspect ratio, fraction of low-angle grain boundaries (FLAGBs), fraction of high-angle grain boundaries (FHAGBs), and average grain size under different rolling reductions after solid solution.

| Rolling reduction |

VFRx(%) |

Aspect ratio |

FLAGBs(%) |

FHAGBs(%) |

Average grain size(μm) |

| 10% |

1.55 |

1.85 |

0.57 |

0.43 |

38.27 |

| 20% |

3.53 |

1.96 |

0.62 |

0.38 |

28.38 |

| 40% |

7.30 |

2.30 |

0.75 |

0.25 |

23.40 |

| 60% |

9.25 |

2.41 |

0.67 |

0.33 |

17.37 |

| 80% |

13.90 |

4.49 |

0.55 |

0.45 |

9.04 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).