1. Introduction

Mycotoxins, secondary metabolites produced by filamentous fungi like

Aspergillus, Fusarium,

Penicillium, and

Alternaria, can contaminate food and pose significant health risks to humans and animals [

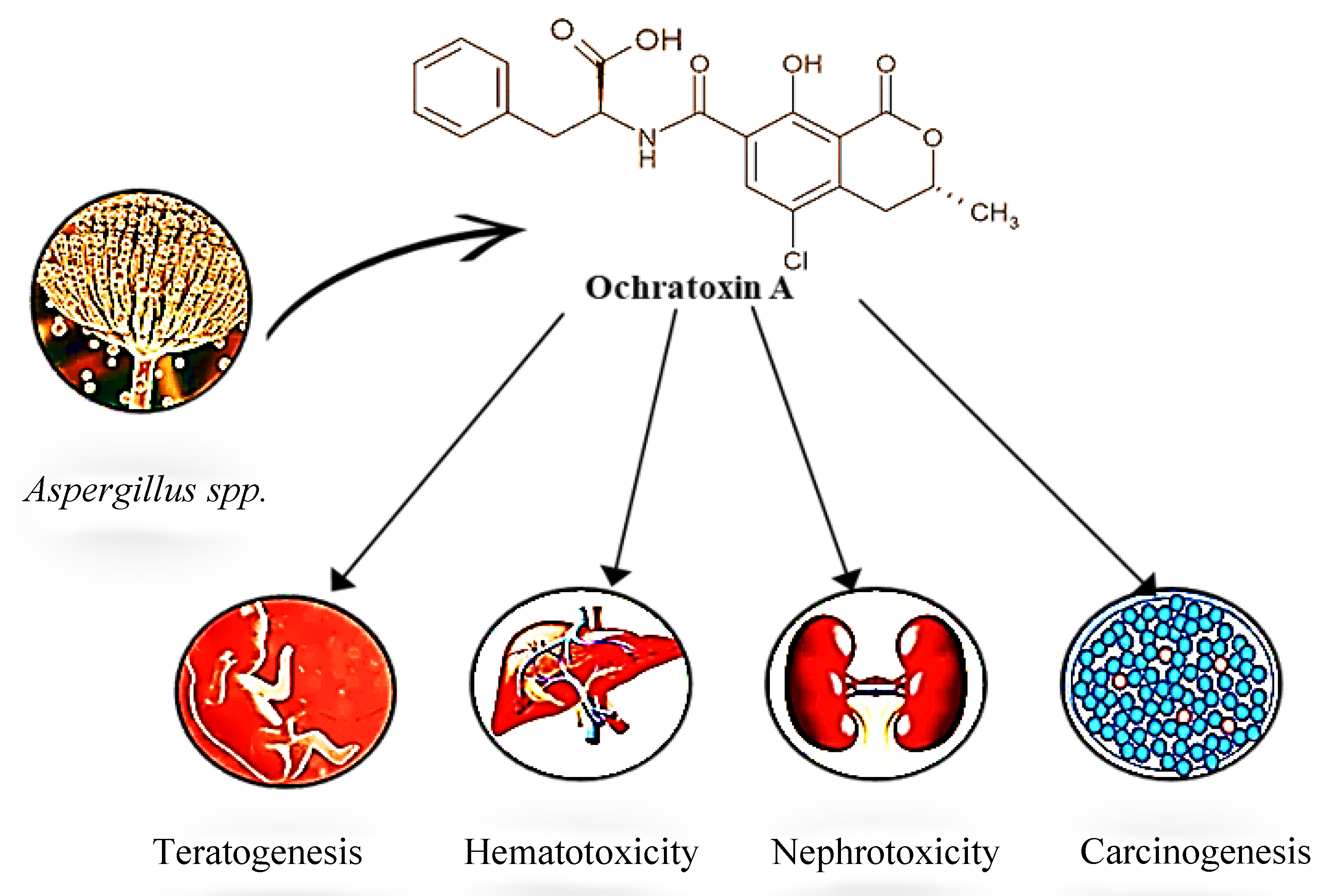

1]. Some of the mycotoxins frequently found in food systems include aflatoxins (AFs), ochratoxin A (OTA), fumonisins (FUM), deoxynivalenol (DON), and zearalenone (ZEN). Among these, OTA is a widely distributed mycotoxin known for its nephrotoxic, hepatotoxic, teratogenic, mutagenic, and immunosuppressive effects [

2,

3]. OTA has been classified as a Group 2B human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), indicating its potential to cause cancer in humans.

It is primarily produced by

Aspergillus and

Penicillium fungi [

4], which thrive in various environmental conditions, including temperatures between 0 to 37 °C [

5]. These fungi can contaminate various food products, such as cereals, coffee, dried fruits, nuts, cocoa, and processed foods [6-9]. Cereals, including corn, wheat, oats, and rice, are among the most affected crops, resulting in significant economic losses [10-12]. OTA’s exceptional thermal stability complicates its removal during food processing, and its extended half-life in the human body exacerbates health risks by allowing accumulation in organs, blood, and even milk [13, 14]. The contamination of food by OTA is influenced by different factors such as temperature, humidity, water activity (Aw), food matrix composition, physical damage, and fungal growth conditions. While the occurrence of fungal infection does not always guarantee mycotoxin production, specific environmental and chemical conditions can promote OTA synthesis or preserve its presence even after fungal inactivation [15, 16]. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that approximately 25% of global grain production is contaminated by mycotoxins, highlighting the urgency of addressing this issue [

17].

Mitigating OTA contamination requires effective strategies that include preventive measures during cultivation and storage, as well as interventions during food processing. Physical methods like gamma ray or electron beam irradiation [18-20] non-thermal approaches like cold plasma (CP) [

21] and chemical approaches like adsorbents and ozone (O

3) have been explored for their potential to reduce OTA levels [

22]. Similarly, biological methods using enzymes, bacteria, and yeasts show promise for their specificity, efficiency, and minimal impact on food quality [

23].

To ensure food safety and minimize consumer exposure to OTA, it is imperative to implement technically feasible, scalable, and cost-effective mitigation strategies that preserve the sensory and nutritional quality of food products. This review explores the toxicity of OTA in food and agricultural products, highlighting its widespread occurrence and challenges. Moreover, it critically examines conventional physical, chemical, and biological methods. It explores innovative techniques like gamma irradiation, cold plasma (CP), adsorbents, ozone (O3) treatment, and biological interventions for reducing OTA levels in the food industry. This review aims to contribute to a safer and higher-quality global food supply by focusing on methods that minimize health risks and economic losses.

2. Chemistry and Properties of OTA

Ochratoxins (OT) are a group of mycotoxins comprising ochratoxin A (OTA), B (OTB), and C (OTC), as well as their methyl and ethyl ester forms [

24,

25]. OTA is the most researched due to its prevalence in food products and higher toxicity. Its structural composition consists of a dihydroisocoumarin ring linked to phenylalanine via an amide bond. OTA, also known as N-(3R)-5-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-oxo-3,4-dihydro-1H-2-benzopyran-7-carboxylic acid, has a molecular formula of C

20H

18ClNO

6 and has a molecular weight of 403.8 [

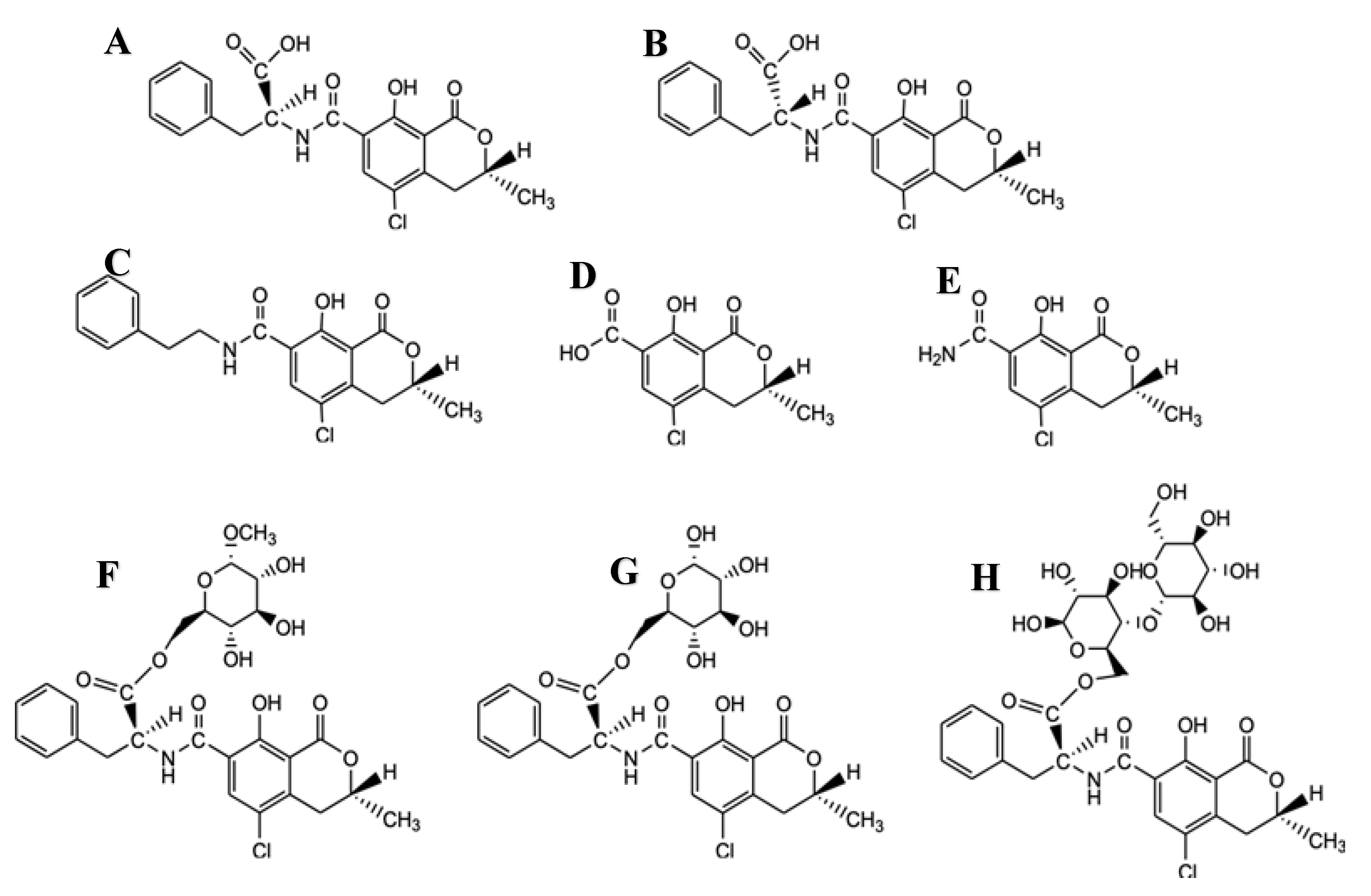

26]. OTA belongs to the class of chlorinated isocoumarins with a pentaketide skeleton (

Figure 1). It is a white, crystalline substance with a high melting point of 169 ℃, indicating significant thermal stability [

27,

28].

This thermal stability poses challenges for food safety, as OTA can persist in processed foods like cereals, coffee, and roasted products even after exposure to typical cooking processes [

29]. For instance, cereal products autoclaved for 3 hours may retain up to 35% of OTA [

30]. Destruction of OTA requires temperatures above 250 °C sustained for several minutes, which is not always feasible in food processing [31, 32]. OTA exhibits sensitivity to light, particularly under high humidity, but its stability can be preserved in ethanol solutions stored in the dark. When exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, it fluoresces green in acidic conditions and blue in alkaline environments [

16]. During coffee roasting at 240 °C for 9 minutes, OTA transforms into various degradation products, including OTα and OTα amide. These compounds have been detected in roasted coffee beans and the bloodstream of consumers, highlighting OTA's stability and transformation during food processing.

Research has identified several OTA analogs and degradation products, including 14-(R)-OTA, 14-decarboxylate OTA, and esters such as OTA-methyl-α-D glucopyranoside and OTA-glucose esters (

Figure 1). These compounds are present in trace amounts in food products like coffee and demonstrate OTA's ability to form stable by-products during thermal processing. However, the kinetics and mechanisms underlying these transformations remain underexplored in other food matrices, indicating a need for further research. In short, OTA is a complex mycotoxin with thermal resistance to conventional cooking processes and the potential for transformation into analogs. Understanding its chemical properties and degradation mechanisms is crucial for developing effective strategies to manage and mitigate OTA risks in high-risk products like coffee and cereals.

3. Sources of Exposure

OTA, a natural contaminant from

Aspergillus ochraceus and other

Aspergillus and

Penicillium species, is primarily a post-harvest issue in food products [

33,

34].

Penicillium species produce OTA in temperate and cold climates, while

Aspergillus species are endemic to tropical and subtropical regions. These fungi are not typically present in crop fields before harvesting due to their lack of a symbiotic relationship with plants. Hence, good harvesting practices, rapid drying of harvested products, and maintaining a dry environment during storage, transport, and processing are essential to minimize OTA contamination in food products [35, 36].

OTA can be found in various foods and beverages, including cereals, bread, flour, cocoa, coffee, spices, soybeans, legumes, nuts, dried fruits, beer, wine, grape/grapefruit juice, and licorice [

37]. Similarly, some species of

Aspergillus produce OTA in grapes, raisins, sultanas, soft fruits, passion fruits, and kiwi [

38]. The average occurrence of OTA in cereals and their derivatives is 0.12 μg/kg of OTA, with values ranging between 0.03 and 27.5 ppm [

39]. Moreover, cocoa can contain OTA at all stages of production, with higher concentrations found in degraded grain [

40]. In Brazil, an OTA concentration of up to 3.3 μg/kg was found in grain coffee, while instant coffee had a concentration of 6.29 μg/kg [41, 42]. In Switzerland, coffee-based drinks had the highest OTA concentration (4.2 μg/L), while coffee sourced from the Ivory Coast had an optimal concentration of 56 μg/kg [

43]. Similarly, Ethiopia-roasted coffee contains a high concentration of OTA (2.0 μg/kg) in its juice [

44], while in Portugal, it is found in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes (115.6 μg/kg) [

45]. Furthermore, OTA contamination in wines ranges from 0.2 to 0.4 μg/L, with red wine having the highest concentrations (1-1.23 μg/L) [

46].

OTA contamination in cereals can lead to ochratoxicosis outbreaks in animals [

53] and can be present in contaminated offal, kidneys, liver, blood, meat products, sausages, ham, and bacon. Its concentrations are negligible in milk, eggs, and other meat products. OTA components can persist for extended periods in the environment of the food industry that handles, stores, or processes contaminated food, including black pepper, cocoa, coffee, and nutmeg [

54]. OTA has been detected in blood, urine, and breast milk, an important indicator of human exposure. Over the years, there has been a trend towards a decrease in serum OTA levels in the human population [

50]. Urine is the preferred method as it provides the most accurate correlation between OTA exposure and its concentrations in urine [

35]. Blood analyses of 3717 healthy humans for OTA research revealed concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 10 ng/mL (with an exceptional case of 160 ng/mL) [

11]. A study examining OTA exposure in adults’ diets in three European countries found that weekly consumers are exposed to 15 - 60 ng of OTA per kg, with the most significant consumers being exposed between 40 to 60 ng/kg. In Portugal, exposure to OTA was assessed using the serum of 104 healthy inhabitants, obtaining 100% positive results [

49]. In Switzerland, children ingested 3.6 ng/kg bw daily due to grape juice consumption [

33]. Exposure of newborns to OTA-contaminated breast milk could be one of the initial sources of dietary exposure [

55]. There is a close relationship between OTA intake and its amount in breast milk, with higher levels detected in the initial days after childbirth. The highest concentration of OTA (1.89 ng/L) was detected in breast milk in a study of the Egyptian population [

51]. In Italy, nine out of fifty breast milk samples showed concentrations of OTA ranging between 1.2 and 6.6 ng/L [

3]. A recent study found OTA in 85.7% of samples, with an average value of 6.01 ng/L [

52].

4. Toxicokinetics and Toxicity of OTA

OTA is a highly toxic mycotoxin that primarily impacts kidney function and is classified as a Group 2B potential human carcinogen. Its toxicity extends to teratogenic, mutagenic, hepatotoxic, and immune suppression effects [

7]. OTA exhibits low water solubility and high protein-binding affinity, with approximately 99.98% binding to plasma proteins, mainly albumin, contributing to its extended half-life of 35 days. This binding allows OTA to circulate in the bloodstream, accumulate in organs like the kidneys, and undergo enterohepatic recirculation, prolonging its toxic effects [

41].

4.1. Mechanisms of Toxicity

The exact mechanism of OTA's toxicity remains under investigation, but several pathways have been identified, including mitochondrial respiration disruption, protein synthesis inhibition, DNA damage, and oxidative stress. Oxidative stress, primarily caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), significantly contributes to OTA's toxicity [

56]. OTA-induced ROS generation damages cells, particularly proximal tubule cells in the kidney. This oxidative stress activates detoxification enzymes through the pregnane X receptor (PXR) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathways [

57,

58]. OTA’s impact on antioxidant defense mechanisms is mediated by nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which regulates genes associated with detoxification and antioxidant enzyme production [59-62]. Reduced Nrf2 activity lowers antioxidant defenses, increasing oxidative stress and cellular damage. A decrease in the activity of these genes could lower the levels of antioxidant defenses, thus increasing oxidative stress and damaging macromolecules.

Paradoxically, enhanced Nrf2 expression under certain conditions stimulates antioxidant enzymes such as heme oxygenase 1 (HO1), superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), and glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) [

63,

64]. OTA triggers oxidative stress directly through redox cycling, and indirectly by impairing antioxidant-dependent cellular defenses, with the kidney being particularly vulnerable [65-67].

4.2. Toxicokinetics

OTA is rapidly absorbed in the intestine and distributed to various organs, including kidneys, liver, adipose tissue, brain, and skeletal muscle. It forms a mobile reservoir in the bloodstream by binding to plasma proteins, making it available to tissues for extended periods [

41]. While OTA-albumin complexes dominate, other low molecular weight proteins (20 kDa) with higher binding affinities contribute to its renal pathogenesis. Renal elimination is the primary excretion pathway for OTA, with about 50% detected in urine. The remainder includes α-ochratoxin and OTA-glucuronide conjugates, with smaller amounts excreted in feces via biliary pathways. Active transport and passive diffusion reabsorb OTA in the nephron, contributing to its kidney accumulation and toxicity. OTA can cross the placenta and accumulate in fetal blood at levels twice as high as maternal blood, raising concerns about parental exposure. Additionally, OTA is excreted in breast milk through Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP), posing risks to infants [

68,

69].

4.3. Organ-Specific Toxicity

OTA’s primary target organ is the kidney, which can induce necrosis, proteinuria, enzymuria, and glycosuria, leading to reduced renal function [

70]. It has been linked to Balkan endemic nephropathy and porcine nephropathy in animals, fetal resorption, prenatal mortality, cerebral necrosis, and malformations in animal models [

71,

72]. Offspring exposed to OTA in utero have been found to have developmental delays, learning deficits, and structural brain abnormalities [

73,

74].

4.4. Carcinogenicity and Genotoxicity

OTA has been linked to kidney and intestinal tumors in rodents and urinary tract tumors in humans. It induces DNA damage, chromosome aberrations, and weak DNA-OTA adduct formation. While some studies report genotoxic effects, others show conflicting results, highlighting the need for further research [

73].

4.5. Immunotoxicity

OTA also inhibits T-cell activation, lymphocyte proliferation, and IL-2 production, impairing immune responses. It also induces T-cell apoptosis by disrupting mitochondrial function (

Figure 2).

Overall, OTA's toxicological profile, including its low water solubility, high protein-binding affinity, and extended half-life, makes it a significant health risk. Understanding its toxicokinetics and mechanisms, including oxidative stress and organ-specific impacts, is crucial for developing effective strategies to mitigate its risks in food safety and public health.

5. Risk Assessment and Regulatory Standards

The increasing concern over the negative effects of OTA, particularly among infants, has led to implementing measures to monitor and control its levels in food products (

Table 2). Countries like the EU, Brazil, China, and the US have established specific thresholds for OTA in various foods, including cereals, coffee, grape juice, beer, wine, grapefruit, and foods for infants and young children. Likewise, Health Canada set standards for OTA in various Canadian food products. The stability of OTAs in everyday foods, including cereals, grapes, raisins, wine, and spices, exacerbates this concern. Although cereals are identified as the primary source of OTA in the diet, frequent consumption of wine also contributes to OTA exposure. Regulatory bodies are establishing guidelines to mitigate the public's chronic exposure to OTA, considering its extended half-life in human serum [

75]. Recent risk assessments have highlighted oat-based cereals as having the highest OTA exposure risk for the pediatric population in the US [

9].

The maximum allowed daily intake of OTA is set at a significantly low level, typically ranging from 5.0 to 14.8 ng/kg bw/day, reflecting the serious health concerns associated with this toxin [

76]. However, standards for acceptable intake levels vary between international bodies and regulatory agencies. For example, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) sets a relaxed 100 ng/kg bw/day threshold, while the European Commission and Canada have established more stringent thresholds at 5 ng/kg and 1.5-5.7 ng/kg bw per day [

77]. On the other hand, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has introduced a provisional tolerable weekly intake (PTWI) of 120 ng/kg bw per day to mitigate the risks linked to OTA exposure [

78]. Furthermore, the EFSA [

79] found that chronic dietary exposure to OTA varies from 0.6 to 17.8 ng/kg bw/day for the general population and from 2.4 to 51.7 ng/kg bw/day for 95% of consumers. The results indicated that stored meats, cheeses, grains, and their derivatives are the primary sources of OTA exposure. Fresh and dried fruits can also contribute to OTA exposure in young children and infants. Thus, risk management strategies have been implemented for each commodity, setting specific maximum OTA contamination levels for several countries.

In short, OTA contamination is a global concern, with countries like the EU, Brazil, China, and the US establishing regulatory thresholds for OTA in food products. These regulations are crucial due to the stability of OTA in food and its extended half-life in human serum, posing significant health risks to infants and young children. Strict monitoring and adoption of risk management strategies and innovative decontamination techniques are necessary to mitigate chronic dietary exposure to OTA.

6. Decontamination Strategies for OTA in Foods

The decontamination of OTA in food is a significant challenge due to its toxic metabolites and thermal stability [

80]. There is no perfect decontamination technique; however, a cost-effective and practical choice must be chosen to maintain the desired sensory and safety properties of the foods. Decontamination strategies for OTA are classified into physical, chemical, and biological methods, which are discussed in the following section.

6.1. Physical Methods

Physical methods can be divided into two groups: those focused on degrading the toxin and those aimed at eliminating the toxin or contaminated parts. Pre-processing procedures, such as washing or polishing the grain, can help reduce mycotoxins in cereals [

81]. High temperatures can also be used to decontaminate OTA, but the thermal stability of the toxin often makes heat treatment ineffective. Factors influencing degradation include temperature, exposure time, and moisture content of food. Temperatures above 150 °C are required for efficient decontamination of OTA, which can negatively affect food quality and make it unsuitable for consumption.

Table 3 provides an overview of the research using physical methods for OTA decontamination in foods.

6.1.1. Gamma Radiation

Gamma radiation travels through space as electromagnetic waves and has been used in food decontamination for over three decades [

83]. It operates by exciting electrons in a food molecule, producing charged particles known as ions. However, gamma rays do not induce radioactivity in food because their energy levels are insufficient to affect neutrons. The effectiveness of this technology is determined by the reduction in the concentration of mycotoxin present [

88]. Khalil

et al. [

18] have recently shown that different radiations up to 20 kGy can effectively inhibit microorganism proliferation in corn contaminated by

A. flavus and

A. ochraceus. However, samples treated with OTA decontamination showed a decrease in growth when exposed to radiation levels above 4.5 kGy.

Maatouk

et al. [

82] applied varying radiation of 2 kGy and 4 kGy to corn flour, resulting in a 48% and 62% reduction, respectively. Khalil

et al. [

18] and Pereira

et al. [

89] achieved a reduction of 4.8% of OTA in corn grain and 5.3% in tea at 5 kGy, respectively. On the contrary, Kumar

et al. [

90] achieved OTA degradation of around 93% in aqueous coffee beans with radiation of 5 kGy. Similarly, Khalil

et al. [

18] recorded a significant increase in OTA degradation (40.3%) in corn with radiation of 10 kGy. Refai

et al. [

91] found that irradiation between 15 and 30.5 kGy led to the complete degradation of OTA in corn. However, Khalil

et al. [

18] achieved a degradation of 61.1% with 20 kGy. Likewise, Calado

et al. [

83] tested higher radiation of 30.5 kGy in wheat flour, grape juice, and wine, obtaining a reduction of 24%, 12%, and 23%, respectively. Calado

et al. [

83] and Khalil

et al. [

18] discovered that OTA decontamination from food matrices is challenging, with corn not effective even at 20 kGy, and grape juice, wine, and wheat flour requiring higher radiation at 30.5 kGy. On the other hand, increasing radiation intensity may lead to deterioration in food quality, as free radicals are generated, oxidizing lipids and vitamins, causing sensory fluctuations and nutritional losses.

Currently, ionizing radiation is restricted due to its higher financial investment and inherent limitations [

92]. Water radiolysis can promote and eliminate OTA and reduce its toxic effects when sufficient moisture is present in food matrices [

83]. Calado

et al. [

83] conducted tests on wheat flour contaminated with different moisture levels (11%, 13%, 18%, and 32%) to evaluate the effect of radiolysis on OTA reduction. Results showed that increasing moisture content significantly improved irradiation productivity, resulting in a 24% decrease in radiation at a 30.5 kGy dose. Moreover, Mehrez et al. [

93] found a 35.5% and 47.2% reduction in whole wheat grains with a water content of 14% to 16% with 8 kGy gamma rays. The study suggests that the inconsistent dispersion of OTA in wheat grains may cause the variation in results.

In short, research on the effects of gamma radiation on OTA is inconclusive, with some studies showing a reduction in OTA at low doses and others suggesting higher doses. Furthermore, irradiation can influence the organoleptic and nutritional properties of foods, and when radiation exceeds 10 kGy, some nutrients are degraded, similar to thermal processing methods like pasteurization. The loss of vitamins, particularly B and C, is the most serious issue associated with irradiation due to their soluble nature and easy oxidation.

6.1.2. Electron Beam Radiation

Electron beam radiation, a type of electromagnetic wave, is known for its high productivity, minimal heat requirement, and short processing time [

94]. Studies have shown that it can reduce OTA in red pepper powder using radiation ranging from 2 to 30 kGy, with a maximum reduction of 25% [

19]. However, electron beam radiation is less effective than gamma radiation due to its low penetration capacity [

95]. For example, Luo

et al. [

96] reported a 65.6% reduction in OTA in corn with 10 kGy radiation. High radiation can also modify the physical and chemical features of food. For instance, 50 kGy radiation reduced amylose content, starch crystallinity, and amino acid numbers in contaminated corn. However, researchers are increasingly interested in using electron beam radiation as a potential technique for degrading complex molecules and decontaminating toxins. Linear accelerator-generated electron beams have the advantage of not using chemical additives or producing waste [

97]. Decontamination in radiation-based technologies can be attributed to direct degradation due to the energy received, but radiolysis is an important factor in this process.

6.1.3. Ultraviolet Radiation

Ultraviolet radiation (UV) is a nonionizing energy produced from light with wavelengths ranging between 10 and 400 nm. It can be classified into three categories: UV-A (315-400 nm), UV-B (280-315 nm), and UV-C (100-280 nm) [

98]. Mercury lamps are commonly used for mycotoxin decontamination, with the 254 nm wavelength being most effective in eliminating microorganisms and reducing toxins [

99]. The FDA has approved the application of UV radiation in food and beverages involving a specific wavelength of 253.7 nm [

100]. UV radiation is widely recognized as a highly effective physical technique for decreasing OTA levels in foods. The performance of a system can be affected by various factors, such as the wavelength of the radiation, time of exposure, mycotoxin structure, and product properties. Exposure to food directly affects its decontamination process; however, increased exposure can lead to significant sensory changes in food [92, 98].

Several studies have discussed the application of UV radiation as an OTA decontaminant using different exposure times with similar wavelengths. Ferreira

et al. [

20] examined the impact of UV rays for 1 to 3 hours on different types of rice (brown, black, and red) that had been naturally contaminated, recently harvested, and preserved for 180 days. The researcher concluded that UV treatment is viable, as it decontaminated twice compared to the untreated group. Similarly, Popović

et al. [

85] used 253.7 nm sources at 16.5 cm to decontaminate corn and wheat grains. OTA exhibited the lowest sensitivity to UV radiation on the grain surface, possibly due to the inconsistent distribution of mycotoxins on the grain surface, particularly within the germ. Likewise, Shanakhat

et al. [

86] assessed the effects of UV radiation with a wavelength of 254 nm at 15 cm on wheat semolina with a sample thickness of 1 cm for different periods (15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes). Upon initiating the treatment, it was found that 15 minutes of UV ray exposure was sufficient to degrade the OTA fully. Meanwhile, Garg

et al. [

101] analyzed the optimization of UV radiation in reducing AF by varying the distance between the lamp and the contaminated peanut samples (15 or 30 cm). The maximum reduction in AF concentration was reported at 15 cm compared to 30 cm, indicating the importance of the distance between the lamp and the food surface in achieving effective decontamination.

Overall, UV radiation is a cost-effective technology used for decontaminating fungal toxins, including OTA, but it has limitations [

102]. Its limited penetration makes it only practical for decontaminating mycotoxins on food surfaces, causing long treatment times and potential product quality deterioration [

103]. Despite these limitations, UV radiation remains a promising solution for OTA decontamination.

6.2. Non-Thermal and Bioprocessing Methods

6.2.1. Separation and Cleaning

The post-harvest process of separating and cleaning agricultural commodities is crucial to removing undesirable substances such as dust, chaff, and fragments, improving crop quality. Studies have shown that reducing OTA levels in cocoa, particularly in nibs (7.5%), can significantly decrease OTA levels, ranging from 49% to 100%. Similarly, Amezqueta

et al. [

104] observed a significant reduction of over 95% of OTA in 14 of 22 cocoa bean samples (64%) during the shelling process. Moreover, Scudamore

et al. [

105] found that cleaning methods significantly decrease OTA concentrations in wheat infected with OTA, with a 2-3% decrease after cleaning. Alternatively, Park

et al. [

106] evaluated the reduction in OTA levels in polished rice by washing, demonstrating that increasing the volume of water could decrease OTA levels by approximately 11.0%. Mansouri-Nasrabadi

et al. [

107] confirmed similar findings, with a single wash that resulted in a 26% reduction in OTA in rice, the second wash leading to a 39% reduction, and the third wash achieved a 43% reduction.

On the other hand, Blanc

et al. [

108] examined the coffee bean cleaning process's impact on removing impurities like stones and silver skin using density segregation and air suction, which slightly decreased OTA levels from 7.3 to 6.8 ng/g. These studies highlight the efficacy of various cleaning and processing methods in mitigating OTA levels in various agricultural commodities. Jalili

et al. [

109] investigated the effectiveness of 18 different chemical therapies on the black and white pepper washing process, focusing on their potential to reduce OTA levels. They found that washing with water alone decreased OTA levels by approximately 20.2% in black pepper and 16.3% in white pepper.

A substantial reduction in OTA content was achieved when peppers were washed with acetic acid (25.8%), citric acid (26.2%), and baking soda (34.5%) [

109]. Moreover, Iha

et al. [

110] found that a 2-minute wash of whole beans and bean flour reduced around 7% and 39% in OTA levels. Furthermore, Amézqueta

et al. [

111] explored the removal of OTA from cocoa bean shells using the solvent extraction device ASE 200, which demonstrated the effectiveness of potassium carbonate (83%) compared to sodium bicarbonate (27%) in reducing the OTA content. By proficiently regulating the operating parameters of ASE 200, the researchers successfully reduced around 95% of the inherent OTA content of cocoa shells [

111].

In short, post-harvest separation and cleaning processes can significantly reduce OTA levels in food products, enhancing safety and quality. Physical methods like shelling cocoa beans and washing rice can decrease OTA concentrations by up to 42.7%. Advanced techniques like the ASE 200 solvent extractor can achieve a 95% reduction in OTA content in cocoa shells.

6.2.2. Milling

Scudamore

et al. [

105] found that milling processes can significantly reduce OTA levels in wheat flour, ranging from 25% to 33%. Similarly, Osborne

et al. [

112] observed that milling can significantly reduce OTA levels in wheat, with hard wheat showing a two-thirds reduction and soft wheat showing a one-third reduction. Moreover, Peng

et al. [

113] discovered that milling can degrade OTA levels in wheat grains contaminated with

A.

ochraceus, with initial levels of OTA at 93.2 ng/g and 248.3 ng/g. After milling, OTA concentrations decreased significantly by 43.3% to 55.2%. These studies highlight the effectiveness of milling and grinding processes in reducing OTA levels in wheat, transforming it into flour, and enhancing food safety by lowering mycotoxin content. They emphasize the need for optimal grain processing strategies across the production chain.

6.2.3. Brewing/Fermentation

During brewing, OTA can transfer from potentially contaminated grains like malted barley into beer [

114]. Barley is susceptible to OTA contamination during storage or malting, where OTA-producing fungi grow optimally [

115]. Unlike other mycotoxins, OTA is resistant to alcoholic and malolactic fermentation or brewing. However, its presence decreases to different degrees during the cooking, fermentation, boiling, and final fermentation stages [

116]. A study by Chu

et al. [

117] has shown that OTA levels can be reduced (approximately 72% to 86%) in the traditional micro-brewing process when added to raw materials at 1 to 10 µg/g concentrations. However, beer produced from highly contaminated barley contains a small fraction of the original OTA despite relying on bacterial enzymes due to low germination rates.

Nip

et al. [

118] discovered that beer brewing decreased by 14% to 19% in OTA contamination levels. Besides, Scott

et al. [

114] noted a 13% decrease in OTA levels during fermentation with three different

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains over eight days. Inoue

et al. [

119] observed a considerable decrease in OTA concentrations of 85% while brewing beer with yeast crops containing 16% OTA. Fermentation prevents OTA production due to alcohol inhibition [

120], but the toxin may remain in the grapes during fermentation [

121]. Freire

et al. [

122] observed considerable reductions in OTA contents in wines, with white, rose, and red wines showing 90.72%, 92.44%, and 88.15%, respectively. Similarly, Csutorás

et al. [

123] observed reductions in OTA levels ranging from 73% to 90% in various wine varieties for 90 days.

Alternatively, Cecchini

et al. [

124] reported a significant decrease in OTA concentrations in white and red wines that decreased 47%-52% and 53%–70% after fermentation with different yeast strains. Moreover, Yu

et al. [

125] explored the effects of lipase and carboxypeptidase A on OTA reduction (10.2% and 18.3%) in grape residue along with buffer solutions. Studies also show decreased OTA levels in fermented dough (5.5%-12.0%) compared to wheat flour [

113]. Valle-Algarra

et al. [

126] found a significant reduction of 29.8%–33.5% in OTA concentrations during dough fermentation. Likewise, Milani and Heidari [

127] found that compressed yeast showed the most significant reduction (12.9% - 27.8%) in OTA levels. These findings suggest that fermentation and brewing processes in fermented foods can reduce OTA levels, improving product safety. Despite OTA resistance, efficient use of specific yeast strains and enzymatic treatments can significantly decrease OTA levels. Further optimization of fermentation and enzymatic processes is needed to mitigate OTA risks in the food supply.

6.2.4. Cold Plasma

Atmospheric pressure cold plasma (CP) is a non-thermal, economical, and environmentally friendly technology that has replaced traditional physical decontamination methods in food [

128]. Plasma, a neutral ionized gas consisting of photons, ions, and free electrons, is generated at a temperature close to room temperature, ensuring it does not induce thermal injury [

129]. Control over the pulse shape, frequency, voltage variation, gas type, and pressure allow precise plasma manipulation. However, the agents responsible for decontamination are free radicals and UV photons resulting from plasma production [

21]. The reduction of OTA through cold plasma is influenced by the specific gas used, exposure time, and the properties of the food. The feed gas has a significant effect on the reduction. However, when CP reaches thin surface layers in solid materials, the initial rate of mycotoxin existing on the exterior of the food can prevent plasma access, reducing its effectiveness [

130].

Casas-Junco

et al. [

87] subjected roasted coffee samples to CP with a power of 30 W and an output voltage of 850 V with helium at a flow rate of 1.5 L/min to assess the reduction in OTA. CP reduced the OTA content in roasted coffee by 50% within 30 minutes of exposure, highlighting its potential for degrading OTA and controlling fungal growth. Similarly, Ouf

et al. [

131] and Devi

et al. [

132] found that using a plasma jet with argon gas can inhibit the synthesis of OTA and AFs by

A. niger. They achieved a 90% reduction in AFs in peanut samples treated with air plasma at 60 W for 15 minutes and a 70% reduction when treated for 12 minutes [131, 132]. This highlights the importance of non-thermal methods for decontaminating OTA in food, with radiation being the most widely used technique.

6.3. Thermal Methods

Mycotoxins, including OTA, are resistant to traditional thermal processing methods like roasting, boiling, and cooking and maintain their stability even at high temperatures. However, specific procedures like extrusion can reduce mycotoxin concentrations and mitigate their harmful impacts. The efficacy of mycotoxin reduction during food processing depends on factors such as food characteristics, initial mycotoxin concentration, heating temperature, duration, heat transfer method, heat penetration depth, pH level, water content, nutritional profile, and effective use of additives [

133]. A study by Boudra

et al. [

134] found that the degradation rate of OTA was affected by variations in temperature and moisture levels. The findings revealed that dry wheat had half-lives of 707, 201, 12, and 6 minutes, while wet wheat had half-lives of 145, 60, and 19 minutes.

Moisture accelerates OTA degradation, but complete eradication of OTA was not achieved [

134]. Furthermore, Dahal

et al. [

28] confirmed OTA's heat stability, with rapid degradation at a pH of 10 and slowest at a pH of 4. These findings suggest that pH levels influence the stability of OTA during heating. Thermal food processing methods have received less attention for reducing OTA and other mycotoxins, including AFs and fumonisins (FMNs), despite their crucial role in food safety [

135]. In short, mycotoxins like OTA in food are challenging to reduce due to their stability under high temperatures. While traditional methods like boiling, frying, and baking have limited effectiveness, extrusion and controlled heating in moisture have shown promise in reducing OTA levels.

6.3.1. Roasting

Roasting coffee beans at high temperatures above 160 °C has been found to reduce OTA levels significantly. The coffee industry is investigating how OTA can withstand heat during roasting due to its potential infiltration. A study found that roasting coffee beans at 150 °C for 3 minutes did not significantly decrease OTA levels. However, increasing the temperature to 250 °C for 5 minutes during industrial roasting can decrease OTA by up to 90%. Nehad

et al. [

136] found that conventional roasting of coffee beans contaminated with OTA led to a 31% decrease in OTA levels. Another study reported reductions in OTA levels by 7.4%-77.6% in low-contamination beans (5.3 µg/kg) and up to 15.1% in high-contaminated beans (57.2 µg/kg) [

137]. Research suggests that roasting coffee at extreme temperatures (220-260 °C) can achieve an 80% decrease in OTA levels [

108]. However, roasting at temperatures above 400 °C can lead to reductions in OTA ranging from 0 and 97% [

138]. These results indicate that the roasting process significantly reduces OTA levels in food, but the reduction depends on the processing parameters and the presence of impurities.

Additionally, roasting can be used in other food products, including cocoa and cereal grains. Manda

et al. [

145] demonstrated that roasting cocoa at 200 °C for 30 minutes can reduce OTA concentrations by 41% while improving cereal grains' texture, crispiness, and volume. Roasting improves digestibility and reduces antinutrient factors through starch gelatinization and protein denaturation. Moreover, roasting improves sensory characteristics, resulting in a longer shelf life [

153]. A study by Lee [

143] revealed that oat grains contaminated with OTA (100 ng/g) decreased from 1.9% to 17.7% when roasted at 120-180 ℃ for 1 hour. On the other hand, brown rice showed a smaller decrease in OTA levels (37%), suggesting that bran fibers act as insulation. While roasting reduces OTA in food products, concerns about potential by-product production can degrade the quality. At 250 °C, OTA can partially isomerize at the C3 site, forming diastereomers with reduced toxicity [

154]. However, the presence or reduction of OTA does not necessarily mean eradicating toxicity, as degradation by-products can still pose health risks [

155].

In conclusion, roasting coffee, cocoa, and cereal grains significantly reduces OTA levels, with higher temperatures offering more significant reductions. However, roasting can also form by-products, potentially reducing OTA levels but not eliminating them. Therefore, continuous research and careful roasting conditions are crucial for optimizing food safety outcomes.

6.3.2. Coffee Brewing

Coffee brewing methods can help mitigate the risk of OTA contamination, but their effectiveness varies. Instant coffee brewing can reduce OTA levels by 3%, while Turkish coffee making (infusion for 10 minutes), drip brewing, and modified Italian moka pot methods show significant reductions. The Turkish coffee-making method decreases OTA levels from 51% to 75%, while the drip brew reduces by 54% - 73%. The 10-minute infusion method shows a reduction of 17% - 25%. The reduction of OTA in coffee can be attributed to the limited contact between hot water and the coffee. Moreover, espresso coffee makers can reduce OTA by around 50%, while Moka pot brewing methods can reduce it by 32%. The auto-drip method can reduce OTA by 15% [

141]. Malir

et al. [

156] found significant reductions in OTA levels across different brewing methods, not due to brewing process reduction but rather the transfer of contents from roasted coffee beans to the drink. Factors like the quantity of water, coffee beans, and brewing time contribute to the coffee's quality and the effectiveness of the OTA reduction.

In short, Turkish coffee-making and drip-brewing methods significantly reduce OTA levels, emphasizing the importance of method selection in controlling contamination risks. Factors like water temperature, brewing duration, and coffee-to-water ratio influence OTA reduction effectiveness, enhancing it and contributing to safer coffee consumption.

6.3.3. Extrusion

Extrusion is a widely used method in the food industry, utilized to manufacture various food products, including cereals for breakfast and infants [

157]. Extrusion has been found to effectively reduce mycotoxins, particularly OTA, by minimizing their harmful effects (

Table 4). However, the exact impact of extrusion on mycotoxin reduction is not yet fully understood. Scudamore

et al. [

158] demonstrated that the extrusion process effectively reduces OTA levels in wheat flour, with key factors being moisture content, temperature, and reaction time. A moisture content of 30% led to OTA reductions of 12% and 24% at temperatures of 116–120 °C and 133–136 °C, respectively [

158]. The reduction of OTA in barley meal varies significantly, ranging from 17% and 86%, depending on the processing conditions. The reduction rate is correlated with the initial amount of OTA, with the most significant reduction occurring at 140 °C with 24% moisture content [

159].

Moreover, under specific conditions, twin-screw extrusion significantly reduces OTA levels in oat flakes by 28% [

160]. This method has also been found to lower OTA levels in rice (83%) and oat flakes (43%), demonstrating its effectiveness in OTA control [

161]. In short, the food industry’s extrusion technology has shown potential in reducing OTA levels in cereals, with factors like moisture content, temperature, and extrusion parameters influencing its efficacy. Higher temperatures and specific moisture settings can effectively mitigate OTA and other mycotoxins in food products, enhancing food safety and lowering potential health risks linked to mycotoxin contamination.

6.4. Chemical Methods

Chemical methods are used to decontaminate OTA by modifying the toxin’s structure using oxidizing agents, hydrolytic agents, antioxidant agents, and some gases [

162]. These irreversible chemical modifications create non-toxic substances for humans. However, some methods can reduce food's nutritional content and palatability [

163]. Standard decontamination technologies include ammonization, ozonation, and acidification. Novel studies are exploring the use of natural substances and adsorbents for food intended for human consumption [

164].

Table 5 summarizes data from various scientific studies revealing the effectiveness of chemical techniques in eliminating OTA contamination in selected foods.

6.4.1. Ozone Treatment

Ozone (O

3), a potent oxidizing agent with three oxygen atoms, is a disinfectant used in the food industry to ensure cleanliness and safety in food production, sanitation of equipment, water management, and disinfection of packaging materials [

167]. It can be produced from dry oxygen using machinery, electric corona discharge, or UV radiation, with the former being more practical and cost-effective for achieving high ozone levels. Ozonation is a highly effective scientific method used in food and feed processing to eliminate microbes, targeting essential components of harmful organisms through oxidation, resulting in microbial inactivation. The key advantage of ozonation is its ability to produce oxygen and leave no residue in food or feed, leaving treated products safe for consumption and extending their microbiological shelf life [

168]. Studies have shown that gaseous O

3 effectively degrades AFs and other mycotoxins under various operational conditions. This significantly reduced wheat, corn, and bran contamination, with percentages of 75%, 71%, and 76%, respectively [

169]. Additionally, the application of O

3 in food has been shown to significantly reduce moisture content in various products, including wheat flour.

In 2018, a gaseous O

3 concentration of 62 g/m3 was used to reduce deoxynivalenol (DON) and zearalenone (ZEA) levels in wheat bran. Exposure times ranging from 15 to 240 minutes led to significant decreases in DON (57%) and ZEA (61%) levels [

170]. In corn flour, gaseous O

3 exhibited significant reductions in ZEA content (38%, 56%, and 62%) after exposure durations of 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes. Corn grits exposed to gaseous O

3 ranging from 20 to 60 g m3 for 120 to 480 minutes exhibited reductions in AFB

1, AFB

2, AFG

1, and AFG

2, with AFG

2 experiencing the highest improvement of 30% after 480 minutes at a concentration of 60 grams per cubic meter [

171]. Furthermore, scabbed wheat experienced a 94% reduction in DON levels in 30 seconds with a concentration of 10 g/m

3 of gaseous O

3 [

172]. Similarly, a concentration of 50 g/m

3 of aqueous O3 applied for 90 minutes resulted in a 95% reduction in ZEA levels in corn flour [

173].

Iacumin

et al. [

174] reported that gaseous O

3 treatment effectively inhibited the growth of

A. ochraceus and the production of OTA in sausages without affecting the ripening process, physicochemical parameters, peroxide value, and sensory attributes of the sausages. Likewise, ozone can eliminate OTA contamination in food. Furthermore, Qi

et al. [

175] found that O

3 treatment can reduce OTA contamination levels and improve the quality of ozonized corn. Likewise, Torlak [

176] reported a 60.2% decrease in OTA and over 2.2 logs of inhibition of fungal growth in sultanas when exposed to 12.8 mg/L gaseous O

3 for 120 minutes.

In summary, O3 is a promising method for combating mycotoxin and pesticide residues in food due to its safety, cost-effectiveness, environmental friendliness, and ease of use. However, it has strong oxidizing properties and potential adverse impacts on phenolic compounds, organic acids, and ascorbic acid in food. Thus, effective implementation of O3 requires interdisciplinary collaboration to maximize its potential in food safety and quality assurance.

6.4.2. Plant Extracts

Plant substances possess antioxidant properties that can reduce mycotoxin production in food [

177]. Using aqueous plant extracts and essential oils in foods can inhibit fungal proliferation and toxin production, making them biodegradable, renewable, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective [

178]. Some natural compounds can also improve food's nutritional properties [179, 180]. The mechanism of modification of OTA by plant extracts is unknown, but alkaloid substances are believed to be involved [

181]. Kalagatur

et al. [

84] assessed the activity of essential oils in the development of

A. ochraceus and

P. verrucosum and the OTA content in corn kernels. Essential oils were derived from various plants, and

P. verrucosum exhibited higher antifungal and inhibitory activity on OTA production. Essential oils of

C. Zeylanicum and

C. martini eliminated fungal contamination and OTA production at 1500 and 2500 μg/g concentrations, respectively. However,

O. basilicum,

Z. officinale, and

C. longa showed complete inhibition only at concentrations of 3500 μg/g [

84]. Ponzilacqua

et al. [

166] studied the antifungal properties of four plant extracts (

Passiflora alata,

Psidium cattleianum,

Origanum vulgare, and

Rosmarinus officinalis) in degrading OTA

in vitro. After incubating OTA-containing solutions with extracts, all showed no significant reduction in OTA. However, adding rosemary extract to an AF solution led to a 60% reduction in its concentration after 48 hours.

6.4.3. Adsorbents

Adsorbents or binders are known for their ability to bind mycotoxins and prevent their absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. However, their applications in food processing are limited. A study by Kurtbay

et al. [

182] evaluated the effectiveness of various adsorbents in lowering OTA concentrations in red wines. The optimum conditions for adsorption were identified as a pH of 3.5 at room temperature [

182]. KSF-montmorillonite and chitosan beads demonstrated the highest OTA adsorption at a 2.5 ng/mL concentration. However, dodecylammonium bentonite and KSF-montmorillonite showed considerable adsorption in a synthetic OTA solution at 250 mg/mL. KSF-montmorillonite was highly efficient in lowering OTA concentrations in red wines while preserving total polyphenols and anthocyanoses [

182]. The study suggests that adsorbents can be effectively integrated into food processing to prevent OTA contamination while maintaining key nutritional and sensory components.

Additionally, Gonzalez

et al. [

22] studied the extraction of OTA from beverages using biocompatible magnetic nanostructures with high binding affinity. They found that alginate with activated carbon or pectin spheres showed a higher reduction efficiency in reducing the OTA concentration in beer, with approximately 90% efficiency [183, 184]. This technique can be applied during beverage manufacturing, but it is important to observe potential changes in palatability and nutrition. Adsorbents can be recovered by washing or filtration and should be used when alternative food decontamination methods are unavailable [

184]. Mohos

et al. [

165] analyzed the extraction power of insoluble beta-cyclodextrin polymers in various buffers with diverse pH levels. They found that the polymer was most effective at pH 3.0, removing approximately 80% of OTA in aqueous solution. This suggests that beta-cyclodextrin could be a mycotoxin binder, which forms a guest-host complex with the toxin and is suitable for extracting other types of mycotoxins, including ZEA, from aqueous solutions. However, further research on optimal adsorption conditions and varying adsorbent effectiveness could broaden applications in food safety and quality assurance.

6.4.4. Additives

Despite current research and technological advancements, eliminating OTA remains a significant challenge. However, improving food processing settings, increasing temperatures and pressures, and implementing effective strategies can significantly decrease OTA levels, thus exploring methods to minimize human exposure.

Baking Soda

Baking soda (NaHCO

3), an alkaline food additive, has been found to significantly reduce OTA levels in various food processing methods, particularly in alkaline conditions. It is the only alkaline substance approved for food preparation and has been classified as GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) by the FDA. Howard

et al. [

185] have shown consistent OTA reductions between 2.8% and 24.0% when baking soda is added to wheat flour for noodles. Recently, Lee

et al. [

151] revealed that the amount of extra baking soda used significantly affects the reduction of OTA during indirect steaming. Adding a small amount of baking soda (1%) to rice-based porridge increased the degradation rate of OTA from 59.4% (without any additives) to 68.7%. However, the effect was more pronounced in oat-based porridge, where the degradation of OTA increased significantly by 57.7% and 72.6% with the addition of 0.5% and 1% baking soda [

151]. At 85 ℃, adding baking soda led to a 36.1% decrease in OTA levels, compared to a 19.8% reduction in control samples. Furthermore, at 121 °C, OTA levels decreased by 44.3%, compared to 27.9% in samples without baking soda [

146]. Further study has shown that baking soda significantly enhances OTA degradation in oat-based porridge more than rice-based porridge. The study found that oat-based porridge decreased OTA concentrations without additives by 17.1%, increasing to 30.3% with 0.5% baking soda and 47.9% with 1% baking soda. On the other hand, rice porridge showed an increase in OTA degradation from 53.8% to 66.4% with 1% baking soda [

150]. In the extrusion process, adding baking soda led to a higher rate of OTA degradation in oat-based snacks [

161]. However, this decrease was not reproduced within rice-based snacks. HPLC-FLD analysis revealed that levels of OTA isomer significantly amplified in rice-based cereal when combined with baking soda.

Sugars

Research indicates that sugars can significantly reduce the levels of OTA during thermal food processing. Interactions between fumonisin B

1 (FB

1) and sugars have been extensively studied, showing that sugars can decrease FB

1 toxicity through Millard reaction complexes [186, 187]. An experiment heating a 6.93 µM FB

1 solution with 100 mM glucose and 50 mM potassium phosphate at 80 °C for two days showed decreased FB

1 levels [

188]. Understanding such reaction mechanisms is essential for creating regulatory guidelines to reduce mycotoxin effects on food. While the Maillard reaction does not involve OTA due to lacking an amine group, investigating other sugar reactions is vital. Gu

et al. [

189] studied OTA’s heat resistance with glucose, fructose, or sucrose, finding significant OTA losses, especially with fructose (1 mg/mL) at 150 °C for 50 to 60 minutes [

182]. Additionally, heating with sugars led to a notable decrease in OTA levels, unlike without sugar.

Thermal treatment with fructose significantly reduced OTA levels, as shown by the half-lives of the sugars and first-order reaction constants. The inclusion of fructose food processing has been shown to increase levels of non-toxic OTα-amide while decreasing toxic 14-(R)-OTA levels. Studies indicate that reducing sugars like glucose and fructose in roasted samples enhances OTA degradation. For instance, oat grains heated at 180 °C for 30 minutes significantly reduced OTA content [

143]. Rice and oat-based porridges with 20 ng of OTA showed notable reductions (59.4%), with retorted rice and oat porridge achieving 54% and 17% reductions, respectively. Adding 1% fructose further increased OTA reduction in oat porridge by 41% and 36%, while rice porridge saw reductions of 39% and 18% [

151]. Variations in OTA reduction across different sugars and temperatures suggest that certain sugars react more effectively with OTA under specific thermal conditions. However, the differences in chemical or physical characteristics of these sugars may not explain these results. Further investigation is needed to understand the mechanisms and potential adverse effects of degrading products.

In short, sugars can significantly decrease OTA levels during thermal food processing, providing a promising solution for reducing OTA toxicity in food products. However, understanding sugars’ effectiveness and interactions with OTA is crucial for developing effective regulatory strategies and processing techniques.

Organic Acids

Yu

et al. [

125] studied the impact of organic acids on reducing OTA levels in grape pomaces from cabernet franc, cabernet sauvignon, and chardonnay varieties. They found that different levels of OTA reduction were based on the type of acid used. Acids like acetic, citric, lactic, and hydrochloric acid led to a significant reduction of 59.8% in cabernet franc, 14.7% in cabernet sauvignon, and 56.8% and 46.4% in two chardonnay samples [

125]. The acidity level was comparable to that of lemon juice, beer, and vinegar. Further research is needed to understand the exact reaction mechanisms causing the reduction of OTA by these acids and assess any potentially harmful by-products of degradation.

Overall, organic acids are essential in the food industry as flavor enhancers and stabilizers and as agents to mitigate OTA contamination. However, their interactions with OTA vary, necessitating further research. Assessing the safety of degradation products is crucial to prevent new risks and develop more effective strategies for minimizing OTA in food products, enhancing food safety, and protecting public health.

Combined Additives

Manda

et al. [

145] studied the impacts of food additives on reducing OTA levels in cocoa-finished products. They used a process of roasting and crushing cocoa nibs, mixing them with equal sugar, and then adding a mixture of cocoa butter (13.3%) and milk (10.6%) [

145]. This resulted in a 51% reduction in OTA in the end product. Lee

et al. [

150] investigated the effectiveness of fructose and baking soda in reducing OTA levels during thermal food processing (

Table 6). They found that adding 0.5% fructose and baking soda to rice porridge during the retorting process did not improve OTA reduction compared to the individual effects of each additive. Similarly, adding 0.5% baking soda to oat porridge led to a 30% decrease, while adding 0.5% fructose led to a 41% decrease in OTA concentrations.

Furthermore, Lee

et al. [

151] discovered different outcomes when combined additives were introduced during indirect steaming. In rice porridge, a mixture of fructose (0.5%) and baking soda (0.5%) reduced OTA by 79%, while certain additives in oat porridge significantly reduced OTA levels by 67% [

151]. These findings highlight the variable impact of combined additives across different cooking methods, such as indirect steaming versus retorting, which differ in treatment pressure and duration.

These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing additive combinations and processing conditions to reduce OTA in food products.

6.5. Biological Methods

Biological methods for decontaminating OTA involving microorganisms like yeast, non-toxic fungi, or enzymes offer potential for the food industry. These methods promote the degradation of toxins and reduce their concentration with high efficiency and specificity [

190,

191]. These methods can be applied pre- or post-harvest to reduce grain contamination in crops or to degrade existing toxins [

192]. Most biological methods for controlling OTA involve bacteria (50%). Toxins bind strongly to microorganisms’ cell walls, making biocontrol agents useful for adsorption. Microbial lipases also show promise for enzymatically degrading OTA [

193].

Table 7 provides data on the techniques, conditions, and percentage reduction in toxin concentration.

6.5.1. Decontamination by Bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria are a promising alternative to chemical preservatives in OTA decontamination due to their nature, safety, biodegradability, and effectiveness in producing antimicrobial compounds [

201]. Studies have shown that Tibetan kefir grains, containing 99.2%

L. kefiranofaciens strains, can detoxify milk contaminated with 1 μg/mL of OTA, resulting in significant reductions in OTA concentrations (90.94% and 94%) [

202]. Moreover, Touranlou

et al. [

197] evaluated the efficacy of four lactic acid bacteria in preventing fungal growth and OTA production in artificially contaminated peanut samples, with

L. Kefiri strain FR7 showing a 75.26% reduction in final OTA levels. Additionally,

in vitro studies by Domínguez-Gutiérrez

et al. [

203] found complete inhibition of OTA production with 15 mg/mL of the supernatant from

L. sp. (RM1) cultivation, suggesting the strain affects mycotoxin production and can extend the shelf life of wheat grains as a model food.

Immobilization offers a solution to improve the stability of bacteria and enzymes, optimizing the removal of bacteria from the resulting mixture and improving the toxin retention capacity of selected strains [

204]. Several matrices have been employed for immobilization, such as encapsulation using palatable substances like alginate beads. Alginate, a natural polysaccharide derived from brown algae, is known for its permeability to small molecules, making it suitable for the food industry [

205]. Shukla

et al. [

23] immobilized

B. subtilis in sodium alginate granules and used them in wine samples fortified with a 20 μg/L OTA solution. After 2 hours, the samples showed an 82.33% reduction in OTA. The granules could be reused multiple times, reducing mycotoxin contamination, and suggesting its potential for reducing OTA in red wine and other liquid foods. Shukla

et al. [

23] also found that sodium alginate beads immobilized with

B. subtilis did not alter the levels of phenolic and organic acids in red wine, even after achieving 80% of the OTA decontamination.

6.5.2. Decontamination by Yeast

Yeasts are effective microorganisms for reducing OTA due to the adsorption mechanisms present in their cell walls [

206]. Kapetanakou

et al. [

207] used 16 yeast strains from various batches of wine and 29 bacterial strains from fermented flour, basil, sourdough, and sausage to reduce OTA in grape juice, beer, and red wine. The decrease in OTA was 12%, 32%, and 22%, respectively.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a valuable microorganism, has been used to decontaminate OTA in grape juice, beer, and red wine. Cecchini

et al. [

199] found a 51% reduction in OTA in red and white grape musts after fermentation with pure yeast cultures of

S. cerevisiae. However, the mechanism behind this reduction remains unclear. In another study, Hassan et al. [

198] investigated the effectiveness of six yeast strains (

S. cerevisiae Sc1 and Sc2,

Candida friedrichii,

C. intermedia,

Cyberlindnera jadinii, and

Lachancea thermotolerans) in removing OTA from contaminated buffers using different pH levels and periods. They found that

S. cerevisiae Sc1 yeast achieved the highest amount of OTA adsorption (92%) at pH 7 with incubation for 15 minutes.

Moreover,

C. intermedia cells in calcium alginate granules effectively eliminated (100%) OTA content in grape juice fortified with 20 μg kg

-1 of OTA after 48 hours of incubation. However, slow release of OTA was reported due to saturation of the binding site. Yeast and lactic acid bacteria as starters during food processing have proven highly effective, particularly in manufacturing fermented drinks and dairy products [

207]. Various yeast and lactic acid bacteria strains can decontaminate products with OTA, as they do not rely on food for their growth and do not produce unnecessary composites into the matrix. Factors such as temperature, pH, contact time, and environment influence the ability to eliminate the toxin from the food matrix [

198].

6.5.3. Decontamination by Enzymes

Enzymes such as carboxypeptidase A (CPA), lipase, and protease have efficiently reduced toxin levels and their toxicological effects, making them useful in various industries [

208]. CPA, a key enzyme in decontaminating OTA, can break down the amide bond of OTA and form non-toxic by-products like ochratoxin A [

209]. Kupski

et al. [

194] studied the use of CPA enzymes from various sources, including

Rhizopus oryzae and

Trichoderma reesei cultures, soybean meal, and commercially prepared pancreatin. The tested samples consisted of wheat flour infected with 20 μg.kg

–1 and 200 μg.kg

–1 of OTA, subjected to enzymatic treatment for 30 to 60 minutes. The soy meal enzyme exhibited the lowest reduction in OTA (20 μg.kg

–1 and 200 μg.kg

–1), while the reduction ranged between 30% and 71% for

R. oryzae, 38.5% - 61% for

T. reesei, and 36.4% - 78.5% for pancreatin. The highest degradation time of OTA was 60 minutes. Another enzyme, peroxidase (PO), can reduce the toxicity of mycotoxins and oxidize organic and inorganic substances with the help of hydrogen peroxides [

210]. Nora

et al. [

190] examined the potential of using the PO enzyme from rice bran to degrade OTA in red and white grape juices. After 24 hours, a 17% decrease in OTA levels was observed in white grape juice, but no reduction was observed in red grape juice, possibly due to the juices’ pH level. CPA and PO can yield satisfactory results, but further research is needed to enhance the use conditions [

190,

194].

6.5.4. Decontamination by Macrofungi

Söylemez and Yamaç [

200] conducted an

in vitro study on the effectiveness of 94 macrofungi isolates from Turkey in decontaminating OTA. The most promising strain was

Agaricus amperes OBCC 5048, which showed a 56% degradation rate [

200]. They found a close relationship between ligninolytic activity and OTA degradation using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). In short, this study suggests that biological methods, mainly lactic acid bacteria, yeasts, and enzymes, have shown significant promise in decontaminating OTA in food.

7. Consideration of Decontamination Methods

Decontamination methods are essential for ensuring food safety and improving food quality by degrading mycotoxins. The effectiveness of these methods is influenced by the specific conditions used, food properties, and the agent responsible for detoxification [

92]. Various methods have been proposed for OTA reduction, with each method having its drawbacks and limitations [

179].

Physical methods, such as gamma and UV radiation, are effective in degrading OTA from liquid food matrices, but their effectiveness is limited by various factors like moisture content, penetration depth, and extended treatment duration [20, 85, 92, 103]. Moreover, Gamma radiation requires substantial financial investment and can affect sensory and nutritional quality. UV radiation is limited to surface decontamination with low penetration efficiency. On the other hand, thermal methods such as roasting, extrusion, and brewing are effective for OTA reduction, within dry foods like coffee beans and cereals. However, high temperatures can lead to toxic by-products or degrade essential nutrients, impacting food quality. Precision control of processing parameters is necessary to balance OTA reduction and product quality. Similarly, the CP application needs to be thoroughly investigated to improve its potential performance [

87,

92]. Alternatively, chemical methods such as adsorbents, plant extracts, and O3 have shown potential in reducing OTA by modifying the toxin's structure or binding it to adsorbent materials; however, they are facing safety concerns due to potential toxic by-products and sensory changes in treated foods [

211]. Certain chemicals may not be suitable for large-scale use in liquid foods and beverages, but their application requires careful monitoring of chemical residues and sensory changes [

211].

Moreover, biological methods involving yeasts, bacteria, and enzymes are highly specific and efficient, often resulting in significant OTA degradation while preserving food quality [

196]. However, their scalability can be limited by controlled conditions and potential variability in performance across food matrices. They are particularly suitable for liquid and fermented food products, providing a sustainable and eco-friendly approach with minimal sensory or nutritional impact. Finally, integrated approaches, combining physical, chemical, and biological techniques, can enhance decontamination efficiency. However, these strategies require careful optimization to avoid undesirable effects on food quality, safety, and cost-effectiveness.

In conclusion, while each method has its merits, biological methods stand out as the most promising due to their specificity, safety, and minimal impact on food quality. However, further research is needed to optimize their scalability and integrate them effectively into existing food processing systems.

8. Future Prospects

The food processing industry is making significant strides in reducing OTA using thermal processing techniques like roasting and extrusion. These techniques effectively decrease OTA levels and enhance the nutritional value of food products. To advance these technologies, the industry should optimize parameters like temperature, time, and moisture level, investigate interactions between food matrices and processing conditions, and develop customized solutions for various products. Mass spectrometry (MS) can help understand the chemical processes in reducing OTA and detecting known and unknown degradation by-products. Moreover, it explores the synergistic effects of thermal processing with other strategies, such as food additives like ascorbic acid, organic acids, and baking soda. These additives can enhance thermal treatments, reducing OTA contamination in food. However, implementing novel processing technologies and additives requires extensive testing and regulatory assessments to remove harmful by-products. This includes toxicological analysis and risk assessments. Educating consumers and food producers about OTA risks and the benefits of these technologies can promote their widespread implementation and safety regulations. Moreover, sustainable processing technologies are essential for reducing OTA levels, lowering energy consumption and waste production, and promoting environmentally friendly manufacturing processes. Prioritizing these areas can improve food production’s ability to regulate OTA contamination and enhance food safety, quality, and sustainability.

10. Conclusions

The decontamination of OTA in food requires innovative strategies to maintain quality and safety. Thermal processing methods like roasting can reduce OTA levels and improve product quality. Novel approaches like extrusion offer practical solutions by allowing precise adjustments to processing parameters. Using specific food additives during thermal processing is also safe and effective. The efficacy of OTA decontamination depends on factors like contamination levels, moisture content, pH conditions, food composition, technology, and processing parameters. Physical and chemical methods have shown potential for OTA degradation, but their efficiency varies with treatment conditions and matrix properties. Biological methods involving yeasts and bacteria offer a promising perspective but require further research to understand decontamination mechanisms, assess by-product toxicology, and evaluate food characteristics during large-scale implementation. Thorough evaluation of known and unknown by-products is crucial to ensure food safety and nutritional integrity.

Author Contributions

R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, visualization, validation, resources, conceptualization, proofreading, F.A.; writing—review and editing, F.M.G.; supervision, N.A.M.; supervision, M.S.P.D.; review, A.I.; review, R.Q.; review.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges that the manuscript has undergone a thorough review before submission to the Journal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pallarés, N.; Berrada, H.; Tolosa, J.; Ferrer, E. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure (HPP) and pulsed electric field (PEF) technologies on reduction of aflatoxins in fruit juices. LWT 2021, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A. Ochratoxin A: General Overview and Actual Molecular Status. Toxins 2010, 2, 461–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malir, F.; Ostry, V.; Novotna, E. Toxicity of the mycotoxin ochratoxin A in the light of recent data. Toxin Rev. 2013, 32, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A.; Samsudin, N.I.P. Aflatoxin Biosynthesis, Genetic Regulation, Toxicity, and Control Strategies: A Review. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneghah, A.M.; Moosavi, M.H.; Oliveira, C.A.F.; Vanin, F.; Sant'Ana, A.S. Electron beam irradiation to reduce the mycotoxin and microbial contaminations of cereal-based products: An overview. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 143, 111557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappozzo, J.; Jackson, L.; Lee, H.J.; Zhou, W.; Al-Taher, F.; Zweigenbaum, J.; Ryu, D. Occurrence of Ochratoxin A in Infant Foods in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Anwar, F.; Ghazali, F.M. A comprehensive review of mycotoxins: Toxicology, detection, and effective mitigation approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A.; Samsudin, N.I.P. Chromatographic Analysis of Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus Isolated from Malaysian Sweet Corn. Separations 2021, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, N.J.; Chen, C.; Palumbo, J.D.; Bianchini, A.; Cappozzo, J.; Stratton, J.; Ryu, D.; Wu, F. A risk assessment of dietary Ochratoxin a in the United States. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 100, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu W.C, Pushparaj K, Meyyazhagan A, Arumugam V.A, Pappuswamy M, Bhotla H.K. Ochratoxin-A as an alarming health threat for livestock and human: A review on molecular interactions, mechanism of toxicity, detection, detoxification, and dietary prophylaxis. Toxicon, 2022, 213, 59-75.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM), Schrenk D, Bodin L, Chipman J.K, del Mazo J, Grasl-Kraupp B, Hogstrand, C., Hoogenboom, L., Leblanc, J C., Nebbia, C.S. Risk assessment of ochratoxin A in food. EFSA Journal. 2020, 18(5), e06113.

- Eskola, M.; Kos, G.; Elliott, C.T.; Hajšlová, J.; Mayar, S.; Krska, R. Worldwide contamination of food-crops with mycotoxins: Validity of the widely cited ‘FAO estimate’ of 25%. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2773–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scottt, P.M.; Kanhere, S.R.; Lau, B.P.; Levvis, D.A.; Hayward, S.; Ryan, J.J.; Kuiper-Goodman, T. Survey of Canadian human blood plasma for ochratoxin A. Food Addit. Contam. 1998, 15, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studer-Rohr, I.; Schlatter, J.; Dietrich, D.R. Kinetic parameters and intraindividual fluctuations of ochratoxin A plasma levels in humans. Arch. Toxicol. 2000, 74, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tola, M.; Kebede, B. Occurrence, importance and control of mycotoxins: A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hua, X.; Shi, J.; Jing, N.; Ji, T.; Lv, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Ochratoxin A: Occurrence and recent advances in detoxification. 2022, 210, 11–18,. [CrossRef]

- Campi, M.; Dueñas, M.; Fagiolo, G. Specialization in food production affects global food security and food systems sustainability. World Dev. 2021, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, O.A.; Hammad, A.A.; Sebaei, A.S. Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus ochraceus inhibition and reduction of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in maize by irradiation. Toxicon 2021, 198, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemariam, H.W.; Kießling, M.; Emire, S.A.; Teshome, P.G.; Töpfl, S.; Aganovic, K. Influence of electron beam treatment on naturally contaminated red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) powder: Kinetics of microbial inactivation and physicochemical quality changes. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 67, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.D.; Lang, G.H.; Lindemann, I.d.S.; Timm, N.d.S.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Ziegler, V.; de Oliveira, M. Postharvest UV-C irradiation for fungal control and reduction of mycotoxins in brown, black, and red rice during long-term storage. Food Chem. 2020, 339, 127810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, R.; Tarafdar, A.; Gaur, V.K.; Singh, S.; Sindhu, R.; Rajasekharan, R.; Madhavan, A.; Binod, P.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, A. Technologies for disinfection of food grains: Advances and way forward. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.L.; Lozano, V.A.; Escandar, G.M.; Bravo, M.A. Determination of ochratoxin A in coffee and tea samples by coupling second-order multivariate calibration and fluorescence spectroscopy. Talanta 2020, 219, 121288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, M. Efficient, safe, renewable, and industrially feasible strategy employing Bacillus subtilis with alginate bead composite for the reduction of ochratoxin A from wine. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 242, 118344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Cunha, S.C.; Fernandes, J.O. Mycotoxins of Concern in Children and Infant Cereal Food at European Level: Incidence and Bioaccessibility. Toxins 2022, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ma, W.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H. The Occurrence and Contamination Level of Ochratoxin A in Plant and Animal-Derived Food Commodities. Molecules 2021, 26, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kőszegi, T.; Poór, M. Ochratoxin A: Molecular Interactions, Mechanisms of Toxicity and Prevention at the Molecular Level. Toxins 2016, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrunhosa, L.; Paterson, R.R.; Venâncio, A. Biodegradation of Ochratoxin A for Food and Feed Decontamination. Toxins 2010, 2, 1078–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, S.; Lee, H.J.; Gu, K.; Ryu, D. Heat Stability of Ochratoxin A in an Aqueous Buffered Model System. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 1748–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, B.; Osteresch, B.; Muñoz, K.A.; Hillmann, H.; Sibrowski, W.; Humpf, H. Biomonitoring using dried blood spots: Detection of ochratoxin A and its degradation product 2’R-ochratoxin A in blood from coffee drinkers*. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]