Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Macromarketing

1.2. Strategic Marketing

1.3. Operational Marketing

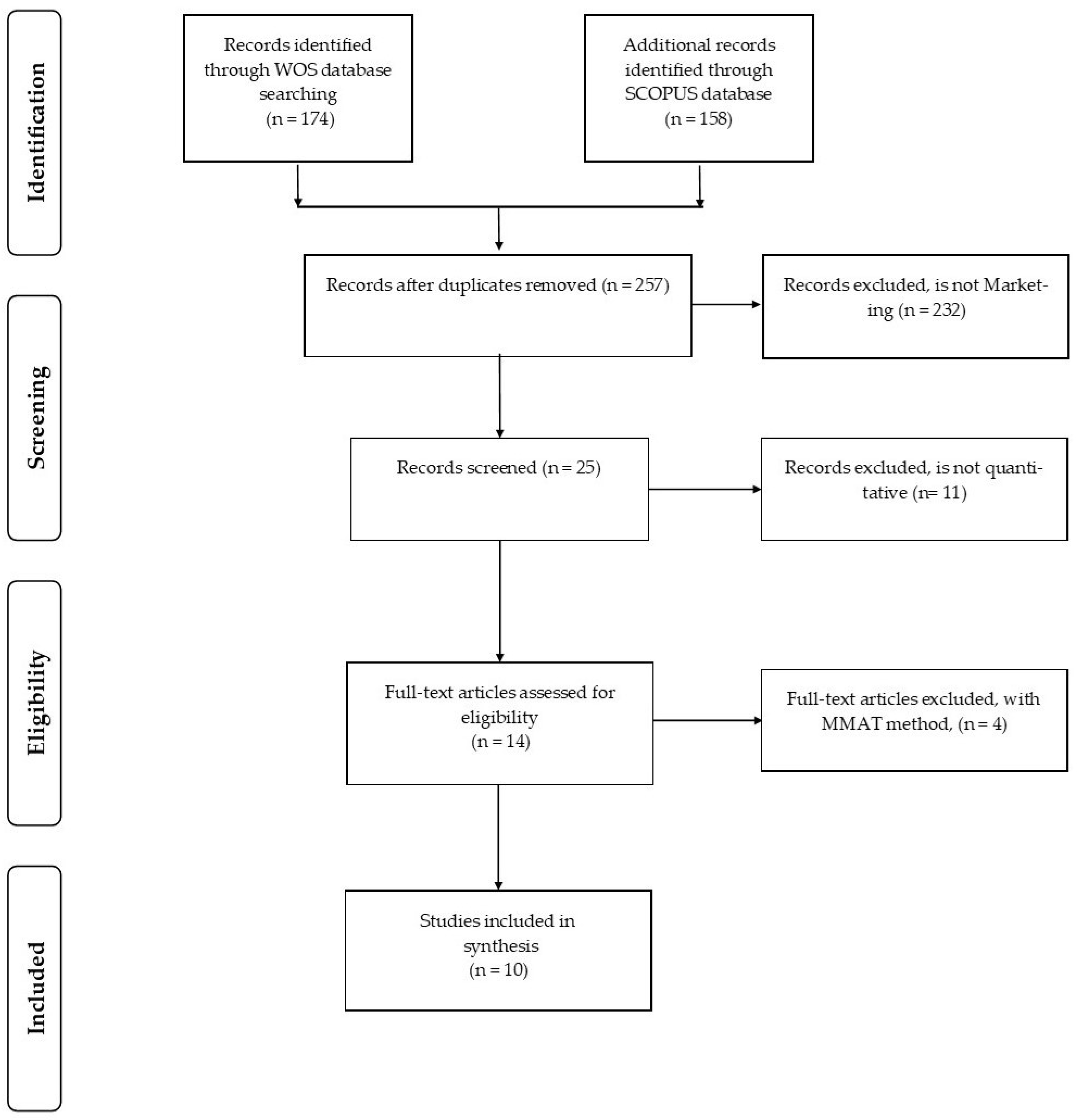

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment, Risk of Bias, and Results Synthesis

3. Results

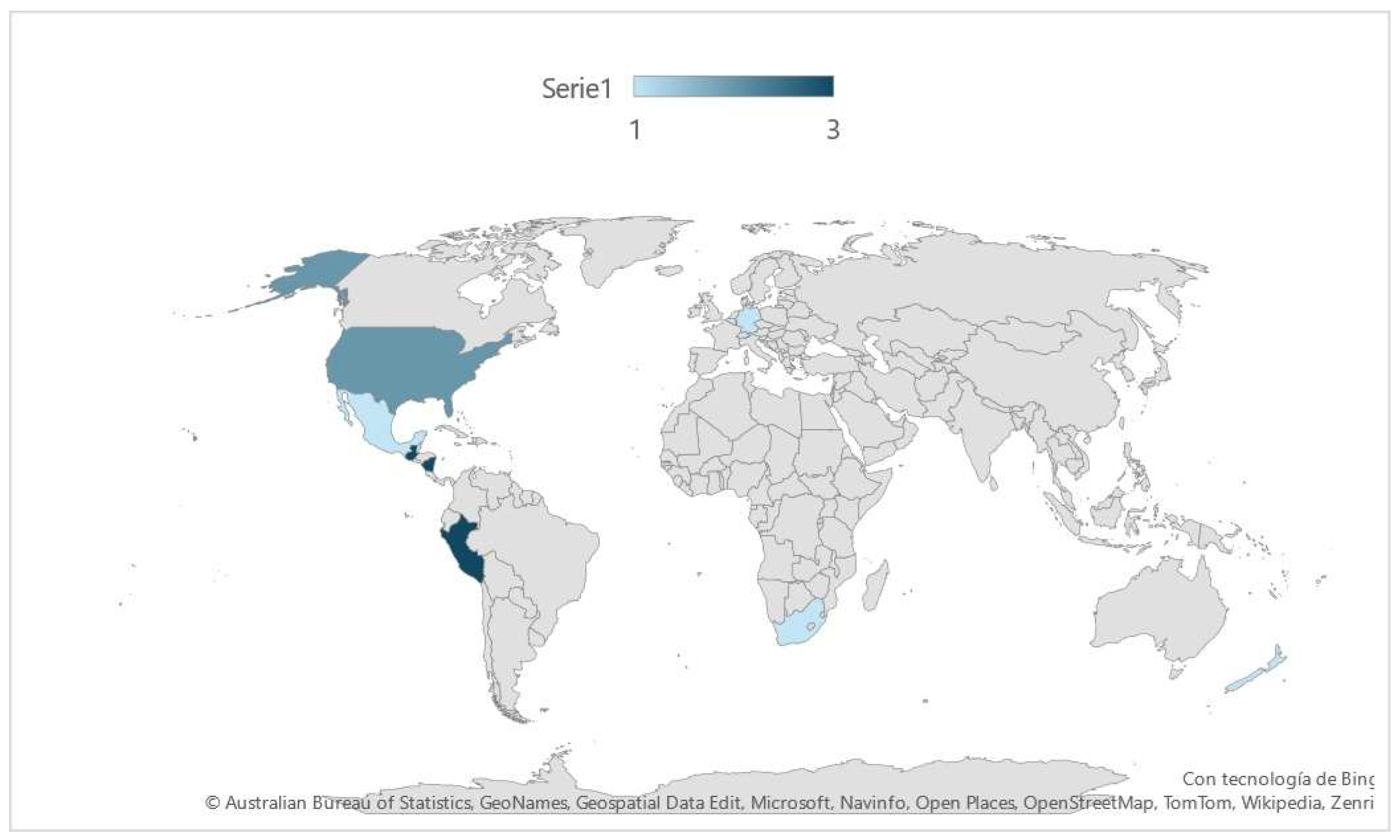

3.1. Results from the Description of the Selected Articles

3.2. Results Studies Macromarketing

3.3. Results Studies Stategic Marketing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Articles | Journal | Pub. Year |

Category of Study Design | S1 | S2 | 3,1 | 3,2 | 3,3 | 3,4 | 3,5 | 4,1 | 4,2 | 4,3 | 4,4 | 4,5 | Quality | Studies Selects >75% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ufer, D; Lin, W; Ortega, DL. [47] | Food Res. Int. | 2019 | Quantitative non-randomized | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 96% | Yes | |||||||

| Paetz, F. [48] | Sustainability | 2021 | Quantitative non-randomized | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 96% | Yes | |||||||

| Lappeman, J; Orpwood, T; Russell, M; Zeller, T; Jansson, J. [49] | J. Clean Prod. | 2019 | Quantitative non-randomized | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 79% | Yes | |||||||

| Linton A.; Liou C.C.; Shaw K.A. [59] | Globalizations | 2004 | Quantitative descriptive | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 64% | No | |||||||

| Geiger-Oneto, S; Arnould, EJ. [50] | J. Macromark. | 2011 | Quantitative descriptive | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 93% | Yes | |||||||

| Darian J.C.; Tucci L.; Newman C.M.; Naylor L. [51] | J. Int. Consum. Mark. | 2015 | Quantitative descriptive | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 93% | Yes | |||||||

| Winchester M.; Arding R.; Nenycz-Thiel M. [60] | J. Food Prod. Mark. | 2015 | Quantitative descriptive | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 71% | No | |||||||

| Hwang, K; Kim, H. [52] | J. Bus. Ethics | 2018 | Quantitative descriptive | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 96% | Yes | |||||||

| Arnould, EJ; Plastina, A; Ball, D. [53] | J. Public Policy Mark. | 2009 | Quantitative descriptive | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | Yes | |||||||

| Arana-Coronado J.J.; Trejo-Pech C.O.; Velandia M.; Peralta-Jimenez J. [54] | J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. | 2019 | Quantitative descriptive | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 96% | Yes | |||||||

| Murphy A.; Jenner-Leuthart B. [55] | J. Consum. Mark. | 2011 | Quantitative descriptive | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 82% | Yes | |||||||

| Arnould E.J.; Plastina A.; Ball D. [56] | Adv. Int. Manage. | 2007 | Quantitative descriptive | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100% | Yes | |||||||

| Webb, J [57] | Sociol. Res. Online | 2007 | Quantitative descriptive | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 57% | No | |||||||

| Howard, PH; Jaffee, D [58] | Sustainability | 2013 | Quantitative descriptive | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 64% | No |

References

- Nicholls, A.; Huybrechts, B. Sustaining inter-organizational relationships across institutional logics and power asymmetries: the case of fair trade. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade International. Fairtrade and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Review of the Impact of Fairtrade. Sustainability 2020, 12, 240–253. [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade USA. Consumer Report: Conscious Consumerism Goes Mainstream, 2022. Available online: https://www.fairtradecertified.org.

- Raynolds, L.T. Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets. Journal of Rural Studies, 2012, 28, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.M.; Sellare, J.; Kouame, C.N.; Qaim, M. Effects of Fairtrade on the livelihoods of poor rural workers. Nature Sustainability 2019, 2, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade International. Annual Report: Driving Progress through Fairtrade, 2023. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net.

- Bezençon, V.; Blili, S. Ethical products and consumer involvement: what’s new? Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewska, M. A typology of Polish consumers and their behaviours in the market for sustainable textiles and clothing. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2013, 37, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-De los Salmones, M.; Pérez, A. The role of brand utilities: application to buying intention of fair trade products. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2019, 27, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why Ethical Consumers Don’t Walk Their Talk: Towards a Framework for Understanding the Gap Between the Ethical Purchase Intentions and Actual Buying Behaviour of Ethically Minded Consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarova, M.; Dyer, C.; Falta, M. Perceptions of blockchain readiness for fairtrade programmes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 185, 122086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, R.A. Marketing systems—a core macromarketing concept. J. Macromark 2007, 27, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooliscroft, B. Macromarketing and the Systems Imperative. J. Macromark 2020, 41, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.E.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainable Consumption and the Quality of Life: A Macromarketing Challenge to the Dominant Social Paradigm. Journal of Macromarketing 1997, 17, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstaedt, J.D.; Shultz, C.J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Peterson, M. Sustainability as Megatrend: Two Schools of Macromarketing Thought. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Macromarketing Metrics of Consumer Well-Being: An Update. J. Macromark 2020, 41, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.J. Assessing distributive justice in marketing: A benefit-cost approach. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 28, 33-43, 1098-1118. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, K.; Peattie, K. Grounded Theory as a Macromarketing Methodology: Critical Insights from Researching the Marketing Dynamics of Fairtrade Towns. Journal of Macromarketing 2015, 36, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, M. Fair Trade and the international moral economy. Crit. Sociol. 2007, 33, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries. J. Public Policy Mark. 2009, 28, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, S.; Wilhite, H. Who Really Benefits from Fairtrade? An Analysis of Value Distribution in Fairtrade Coffee. Globalizations 2010, 7, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Customer information resources advantage, marketing strategy and business performance: A market resources based view. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintani, L.; Ridwan, R.; Kadeni, K.; Savitri, S.; Ahsan, M. Understanding marketing strategy and value creation in the era of business competition. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 6, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.-F.; Wang, R.-Y.; Yang, H.-T. How consumer mindsets in ethnic Chinese societies affect the intention to buy Fair Trade products: The mediating and moderating roles of moral identity. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, R.; Wright, M.J.; Avis, M.; Feetham, P.M. If you think about it more, do you want it more? The case of fairtrade. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2556–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Chou, C.-F. Norms, consumer social responsibility and fair trade product purchase intention. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 49, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Gutsche, S. Consumer motivations for Fair Trade: Why are consumers buying Fairtrade products? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, D. Fair trade standards, corporate participation, and social movement responses in the global economy. Sociol. Perspect. 2014, 57, 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koos, S. Moralising markets, marketizing morality. The fair trade movement, product labeling and the emergence of ethical consumerism in Europe. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2021, 33, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukotjo, C. Marketing mix for service businesses: The 7Ps. Bus. Rev. 2010, 54, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X. Green marketing and sustainability in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarova, M.A.; Castka, P.; Boughen, N. Sustainability and the fair trade premium: A stakeholder approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorata, L. Retailers’ commitment to sustainable development: A strategy to gain consumer loyalty? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littrell, M.A.; Dickson, M.A.; Vieira, E.A. Fair Trade apparel: consumer perceptions of social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.; Evans, A. Ethical food labeling and consumer trust. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E.A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M.G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; Godfrey, C.M.; Macdonald, M.T.; Langlois, E.V.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Moriarty, J.; Clifford, T.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Straus, S.E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Maradiaga-López, J.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Contreras-Barraza, N. Study protocol for a scoping review about Marketing components in fair trade coffee studies. [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.L.; Kongthon, A.; Lu, J.C. Research profiling: Improving the literature review. Scientometrics 2002, 53, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. Advanced Search Query Builder, Web of Science. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/advanced-search (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Scopus. Advanced search. Available online: https://www-scopus-com.unap.idm.oclc.org/search/form.uri?display=advanced (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clinic. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Monreal, L., Galván-Estrada, I.G., Dorantes-Pacheco, L., Márquez-Serrano, M., Medrano-Vázquez, M., Valdez-Santiago, R., & Piña-Pozas, M. Alfabetización sanitaria y COVID-19 en países de ingreso bajo, medio y medio alto: Revisión sistemática. Global. Health Promot. 2023, 17579759221150207. [CrossRef]

- Ufer, D.; Lin, W.; Ortega, D.L. Personality traits and preferences for specialty coffee: Results from a coffee shop field experiment. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paetz, F. Recommendations for sustainable brand personalities: An empirical study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappeman, J.; Orpwood, T.; Russell, M.; Zeller, T.; Jansson, J. Personal values and willingness to pay for fair trade coffee in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 239, 118012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger-Oneto, S.; Arnould, E.J. Alternative trade organization and subjective quality of life: The case of Latin American coffee producers. J. Macromark 2011, 31, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darian, J.C.; Tucci, L.; Newman, C.M.; Naylor, L. An analysis of consumer motivations for purchasing fair trade coffee. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2015, 27, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H. Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries. J. Public Policy Mark. 2009, 28, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Coronado, J.J.; Trejo-Pech, C.O.; Velandia, M.; Peralta-Jimenez, J. Factors Influencing Organic and FairTrade Coffee Growers Level of Engagement with Cooperatives: The Case of Coffee Farmers in Mexico. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark.Marketing 2018, 31, 22–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Jenner-Leuthart, B. Fairly sold? Adding value with fair trade coffee in cafes. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 287, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. “Market Disintermediation and Producer Value Capture: The Case of Fair Trade Coffee in Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala. Product and Market Development for Subsistence Marketplaces. Adv. Int. Manage. 2007, 20, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J. Seduced or Sceptical Consumers? Organised Action and the Case of Fair Trade Coffee. Sociol. Res. Online 2007, 12, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.; Jaffee, D. Tensions between firm size and sustainability goals: Fair trade coffee in the United States. Sustainability 2013, 5, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, A.; Liou, C.C.; Shaw, K.A. A taste of trade justice: marketing global social responsibility via Fair Trade coffee. Globalizations 2004, 1, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, M.; Arding, R.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. An Exploration of Consumer Attitudes and Purchasing Patterns in Fair Trade Coffee and Tea. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2015, 21, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS | Description | Inclusion reason |

| Population | Coffee consumers, Coffee farmers, Coffee traders, Communities near coffee plantations. | Theoretical beneficiaries of Fair Trade coffee. |

| Interventions | Application of questionnaires and quantitative methods under standard The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. | Open to formal and empirical sciences. |

| Comparator | 1) Focus on Macromarketing (MM), Strategic Marketing (SM), and Operational Marketing (OM) 2) Research method. | Focus on the topic under study. |

| Outcomes | 1) Classifications of SM (consumer behavior, segmentation and targeting strategies, branding strategy decisions, analysis of the business environment and competition) 2) Classifications of OM (price, promotion, product place, people, processes and physical evidence) 3) Macromarketing Categories 4) SDG Classifications OM MM and SM. | Focus on the topic under study. |

| Study designs | Quantitative studies, under standard The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. | Empirical sciences. |

| Authors | Articles | Journal |

Pub. Year |

Category of Study Design MMAT |

Country | Source Data Base | DOI | ||||||||

| Ufer, D; Lin, W; Ortega, DL [47] | Personality traits and preferences for specialty coffee: Results from a coffee shop field experiment | Food Res. Int. | 2019 | Quantitative non-randomized | United States | WoS | 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108504 | ||||||||

| Paetz, F [48] | Recommendations for Sustainable Brand Personalities: An Empirical Study | Sustainability | 2021 | Quantitative non-randomized | Germany | WoS | 10.3390/su13094747 | ||||||||

| Lappeman, J; Orpwood, T; Russell, M; Zeller, T; Jansson, J [49] | Personal values and willingness to pay for fair trade coffee in Cape Town, South Africa | J. Clean Prod. | 2019 | Quantitative non-randomized | South Africa | WoS; Scopus |

10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118012 | ||||||||

| Geiger-Oneto, S; Arnould, EJ [50] | Alternative Trade Organization and Subjective Quality of Life: The Case of Latin American Coffee Producers | J. Macromark. | 2011 | Quantitative descriptive | Nicaragua, Peru and Guatemala | WoS; Scopus |

10.1177/0276146711405668 | ||||||||

| Darian J.C.; Tucci L.; Newman C.M.; Naylor L. [51] | An Analysis of Consumer Motivations for Purchasing Fair Trade Coffee | J. Int. Consum. Mark. | 2015 | Quantitative descriptive | United States | Scopus | 10.1080/08961530.2015.1022920 | ||||||||

| Hwang, K; Kim, H [52] | Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness | J. Bus. Ethics | 2018 | Quantitative descriptive | South Korean | WoS; Scopus |

10.1007/s10551-016-3236-1 | ||||||||

| Arnould, EJ; Plastina, A; Ball, D [53] | Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries | J. Public Policy Mark. | 2009 | Quantitative descriptive | Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala. | WoS; Scopus |

10.1509/jppm.28.2.186 | ||||||||

| Arana-Coronado J.J.; Trejo-Pech C.O.; Velandia M.; Peralta-Jimenez J. [54] | Factors Influencing Organic and Fair Trade Coffee Growers Level of Engagement with Cooperatives: The Case of Coffee Farmers in Mexico | J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. | 2019 | Quantitative descriptive | Mexico | Scopus | 10.1080/08974438.2018.1471637 | ||||||||

| Murphy A.; Jenner-Leuthart B. [55] | Fairly sold? Adding value with fair trade coffee in cafes | J. Consum. Mark. | 2011 | Quantitative descriptive | New Zealand | Scopus | 10.1108/07363761111181491 | ||||||||

| Arnould E.J.; Plastina A.; Ball D. [56] | Market Disintermediation and Producer Value Capture: The Case of Fair Trade Coffee in Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala | Adv. Int. Manage. | 2007 | Quantitative descriptive | Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala | Scopus | 10.1016/S1571-5027(07)20014-2 |

| Authors | Journals | Focus publications marketing and Fair Trade | Outcomes marketing categories | Outcomes marketing subcategories | Outcomes Main SDG identified* |

Brief conclusions studies |

||||||

| Ufer, et al. [47] | Food Res. Int. | This article explores how personality characteristics, such as extraversion and conscientiousness, influence consumers’ willingness to pay for specialty coffee from cooperatives, highlighting the importance of segmenting them not only by demographic factors, but also by psychological ones. | Strategic Marketing | Consumer Behavior | 12 | Personality traits, such as extraversion and responsibility, increase the willingness to pay a premium price for products that promote fairer and more sustainable trade | ||||||

| Paetz, et al. [48] | Sustainability | How sustainable consumer personalities can be aligned with brand personalities to achieve greater success in marketing sustainable products. The research analyzes sustainable consumer personalities and proposes brand personality dimensions, such as competence, emotion and sincerity, to create a harmonious and effective brand strategy. | Strategic Marketing | Consumer Behavior | 12 | The consumer’s personality, specifically those who are more open and friendly, positively influences their willingness to pay more for sustainable products, such as those with Fair Trade certification. | ||||||

| Lappeman et al. [49] | J. Clean Prod. | Relationship between personal values and willingness to pay for Fair Trade coffee in Cape Town. The study segments consumers according to their willingness to pay and how their personal values, such as humanitarianism, influence their purchasing decision. | Strategic Marketing | Consumer Behavior, Segmentation |

9 | Findings indicate that consumers with humanitarian values and knowledge of Fair Trade are willing to pay a premium price for these products. | ||||||

| Geiger-Oneto, et al. [50] | J. Macromark. | The effects of Fair Trade on the quality of life of coffee producers in Latin America, evaluating how cooperatives impact their subjective and economic well-being. that examines the impact of the Fair Trade system on the relationships between producers, consumers and the global market, considering large-scale social and economic aspects. | Macromarkeitng | Quality Life, coperativism | 1 | The findings highlight that farmers participating in Fair Trade cooperatives report a higher quality of life, better income and a more positive outlook on the future for their families. | ||||||

| Darian et al. [51] |

J. Int. Consum. Mark. | The focus of the article is to investigate consumers’ motivations for purchasing Fair Trade coffee, focusing on the perceived benefits to workers and farmers, examining the reasons behind purchasing decisions and how consumers value the ethical aspects of Fair Trade. | Strategic Marketing | Consumer Behavior | 9 | Consumers mainly buy Fair Trade coffee to improve wages and working conditions for farmers and workers. Frequent buyers and those with greater knowledge of Fair Trade prioritize long-term benefits such as community development and producer empowerment more than occasional buyers. | ||||||

| Hwang, et al. [52] |

J. Bus. Ethics | What ethical consumers’ motivations, based on empathy or self-orientation, affect their happiness when they consume Fair Trade coffee. It explores how emotional and psychological factors influence consumer satisfaction and repurchase intention. | Strategic Marketing | Consumer Behavior | 9 | The study shows that ethical consumers’ happiness is primarily driven by self-oriented motivations such as self-actualization and narcissism, rather than moral emotions like empathy and guilt. Narcissism fosters self-actualization, which then boosts happiness and encourages repurchasing Fair Trade coffee | ||||||

| Arnould, et al. [53] |

J. Public Policy Mark. | Assessing whether Fair Trade meets its core value proposition by improving the income, education and health of small coffee producers in Latin America. examines the social and economic impact of Fair Trade on the lives of producers, connecting consumers and producers within a global system of ethical trade. | Macromarkeitng | Quality Life, cooperativism | 3 | Fair Trade coffee participation boosts farmers’ income and offers some educational and health benefits, though inconsistently. Cooperative membership increases the chances of children attending school and improves access to medical care, particularly for long-term participants. | ||||||

| Arana-Coronado et al. [54] |

J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. | Factors that influence the level of engagement of organic and Fair Trade coffee producers with cooperatives in Mexico. It studies how the economic and social relationships between producers and cooperatives affect farmers’ participation in the global market, focusing on the large-scale implications of Fair Trade and organic coffee. | Macromarkeitng | Quality life, Cooperativism | 9 | Farmers in Fair Trade cooperatives in Mexico report better income and quality of life. Payment delays and uncertainty reduce their engagement, leading some to sell outside the cooperative. Strengthening commitment and improving payment processes increase cooperative participation. | ||||||

| Murphy et al. [55] |

J. Consum. Mark. | Explores how Fair Trade coffee can help differentiate and strategically position coffee shops by analyzing how the use of Fair Trade coffee and its promotion can influence customer perceptions and help coffee shops stand out from the competition. | Strategic Marketing | Positioning | 9 | The study found that many customers overestimated their Fair Trade knowledge. More informed customers valued fair trade and the cafe atmosphere but expected lower price premiums. After learning more, they supported higher prices, though their expectations for coffee taste worsened. | ||||||

| Arnould et al. [56] |

Adv. Int. Manage. | How participation in Fair Trade enables small coffee producers to capture more economic value through disintermediation. Studies the large-scale social and economic impact of Fair Trade in rural communities, improving the quality of life, education, and access to health services for producers. | Macromarkeitng | Quality Life, cooperativism | 4 | Producers in TransFair USA-supported Fair Trade cooperatives capture more value than nonparticipants, leading to modest but measurable improvements in quality of life, health, education, and sustainable agricultural practices. |

| Macromarketing | Strategic Marketing | Operational Marketing | |

| Central Countries | No cases found | Germany, United State, South Korea, New Zealand issues related to Consumer Behavior, Segmentation, Positioning and Sustainability Branding | No case found |

| Peripheral countries | Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala, Mexico. Main topics related to cooperativism, quality of life and impacts on health and education | South Africa, Main issues related to Humanitarian Values, Fair Trade Knowledge, Willingness to Pay Premium Price | No case found |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).