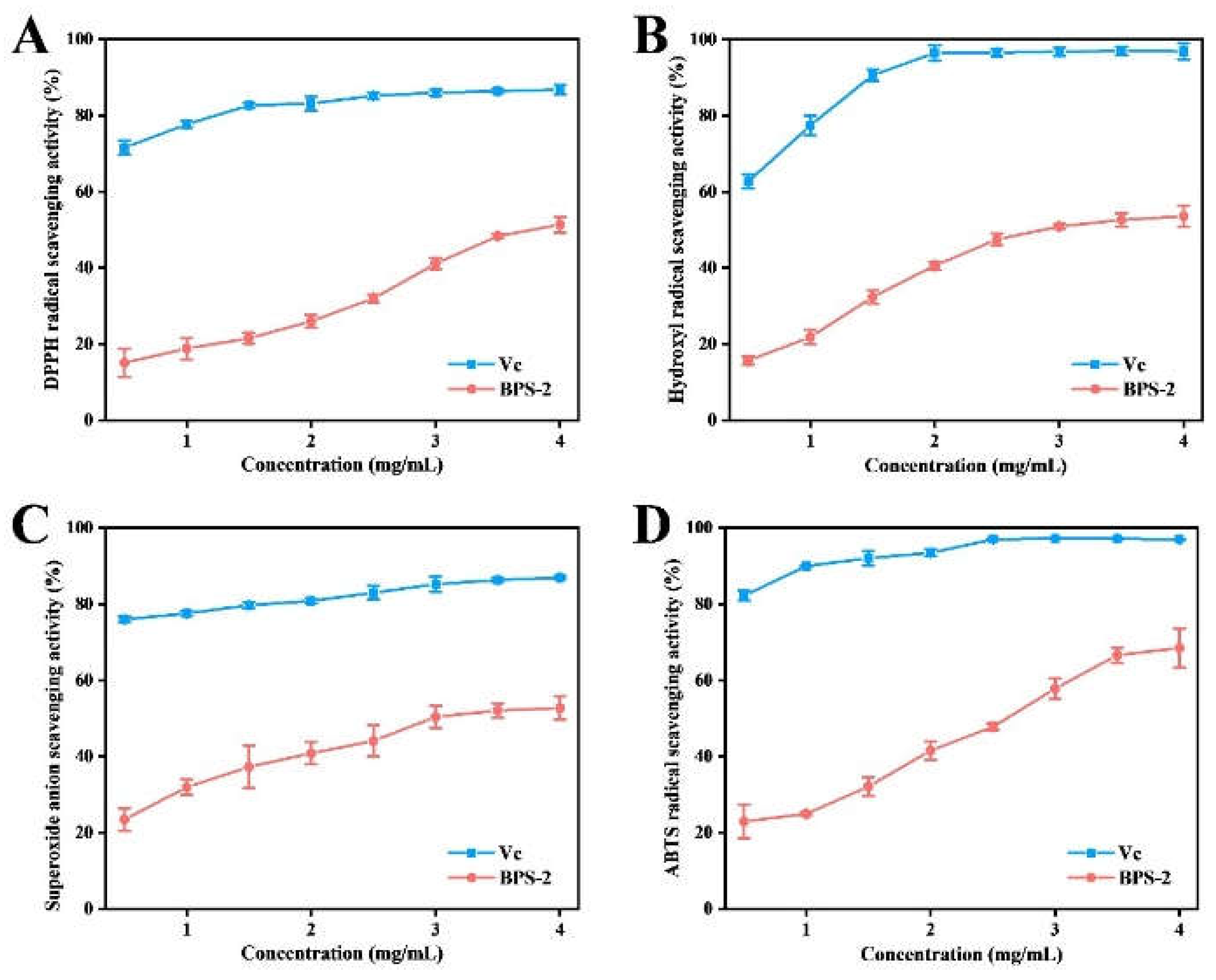

1. Introduction

Bacterial exopolysaccharides (EPS) are macromolecules synthesized by bacteria and are of interest due to their diverse functional properties [

1]. EPS are important for supporting the survival of microbial cells, including protection, aggregation, and interactions [

2]. Currently, commercialized bacterial EPS include xanthan, thermogel, curdlan, and pullulan. They have the advantages of high adsorption, high biodegradability, and high biocompatibility, making them ideal for industrial applications [3-5]. Importantly, the composition of bacterial EPS is strictly dependent on their genes and cultural environment.

Bacillus is an important genus of bacteria, characterized by tolerance to extreme environments and genetic stability for long-term preservation [

6]. There are numerous reports of

B. thuringiensis being used as a biopesticide [7-9]. By contrast, in the field of probiotics

B. thuringiensis has not yet been recognized as probiotics such as

B. subtilis, although they are genetically very similar. To date, only one report other than ours has been published on the application of

B. thuringiensis EPS outside the biopesticide area [

10].

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, nonspecific inflammatory disease. Lesions occur primarily in the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum and may spread further throughout the colon, with recurrence in severe cases [

11]. To date, the etiology and pathogenesis of UC remain unclear because it is the result of a combination of factors, including oxidative damage, immune disorders, intestinal flora, and genetics [

12]. The most frequently used drugs to treat UC disease are mesalazine, immunomodulators, and glucocorticoids. Because these drugs are relatively expensive, and UC is characterized by constant recurrence, the financial and psychological stress on patients is exacerbated [

13]. Therefore, alternative substances with an acceptable safety profile need to be found for long-term suppression of UC [

14]. It has been shown that supplementation with glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) can repair the intestinal epithelial barrier and serve as an effective treatment for UC [15-17]. Common GAGs include hyaluronic acid, heparin, and chondroitin sulfate, which are mainly found in mammalian connective tissues. The absence of the defense barrier of GAGs in the host is one of the main causes of UC.

Studies have shown that regulation of the intestinal flora has an essential role in alleviating UC, including maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier, enhancing immunity, and suppressing intestinal pathogens [

18]. However, the effects of GAGs on intestinal microorganisms have been reported rarely. In addition, EPS has specific reactive groups, such as benzyl, acetyl, and phosphate groups, which can also significantly enhance antioxidant and anticancer activities [

19]. In our previous study, we evaluated the immune-anti-inflammatory effect of BPS-2, a key EPS component of

B. thuringiensis IX-01, on the stimulation of RAW 264.7 cells [

20]. The isolated BPS-2 was a heteropolysaccharide with a molecular weight of 29.36 kDa. The backbone of its basic unit was composed of four 1,4-β-GaINAc, four 1,4-β-GlcNAc, and two 1,4-α-Glc

p, and the branched chain was composed of one 1,4-β-Man

p, one T-β-Glc

p, one 1,6-α-GaINAc, and two 1,5-α-Ara

f, with 10 to 11 such basic units constituting BPS-2.

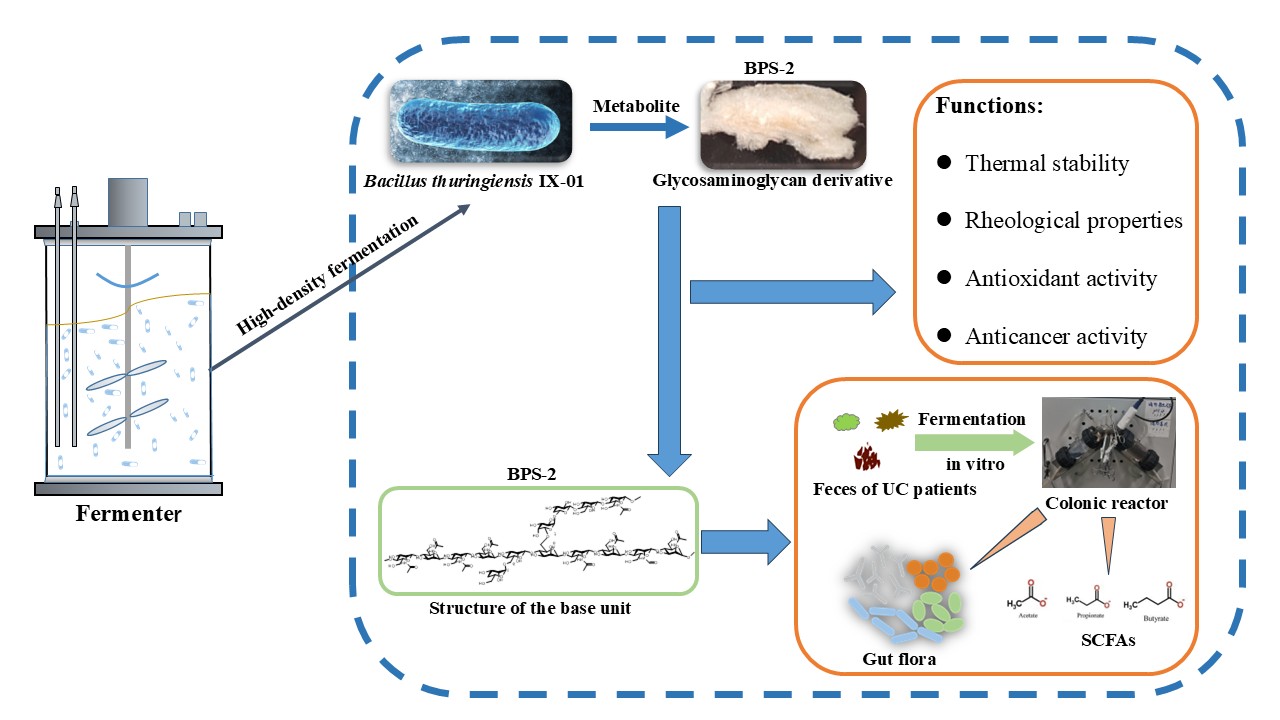

The basis of the BPS-2 activity, as a derivative of GAGs, combined with the literature reports that GAGs have a repair function regarding the colonic barrier, we hypothesized that BPS-2 also has a role in regulating the UC intestinal flora. Therefore, we collected fecal flora from UC volunteers to simulate fermentation in an in vitro colonic model, thus exploring the effect of BPS-2 on human UC intestinal flora. In addition, the apparent morphology, thermal stability, rheological properties, and antioxidant and anticancer activity of BPS-2 were evaluated.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Surface Morphology Analysis of BPS-2

Congo red is an acid dye that forms complexes with polysaccharides in a three-strand helical conformation. As shown by the Congo red test (

Figure 1A), both the EPS part of

B. thuringiensis BPS-2 and the blank control decreased to the same extent with an increase of NaOH concentration in the range 0-0.5 mol/L, thus indicating that BPS-2 does not have a three-strand helical structure.

SEM is used widely to observe the composition and morphology of the surface of ultra-structures. As shown in the SEM images (

Figure 1B), the surface morphology of BPS-2 is composed of many sheets of varying morphology, stacked together tightly and irregularly, but the sheets still have three-dimensional pores of varying sizes between them, which can provide the material with the capacity to swell and retain water [

21].

In recent years, AFM microscopy has been used widely to observe the physical morphology and macromolecular chain size of polysaccharides. In the AFM plain image (

Figure 1C), different degrees of aggregation (0-15.91 nm in diameter) were observed between the BPS-2 molecules. Given that the BPS-2 polysaccharide was originally known to have a structure with two branched chains, a variable degree of aggregation likely resulted from the combined action of the branched and straight chains. As shown in the AFM stereogram (

Figure 1D), the molecule of BPS-2 shows a punctate or peak-like structure with a height ranging from 0.92 to 39.46 nm; by contrast, other studies have shown that the usual single chain height of polysaccharide molecules is around 0.1~1.0 nm [

22], which indicates that the polysaccharide mono-chain of BPS-2, as a base unit, is able to cross-link with multiple mono-chains. The reason for this intermolecular cross-linking of polysaccharide is due to the interaction of the branched chains with the non-carbon substituents on the polysaccharide through the negative and positive charges on the sugar chain [

23].

Combining the known chemical structure of BPS-2 base unit (

Figure 1E) and the lack of three-strand helix structure, it could be surmised that the spatial conformation of BPS-2 was mainly tandem with straight chains; however, when the polysaccharide concentration was high, its branched chains would join the long chains formed by their respective tandem to form a lamellar macromolecular substance, and this phenomenon was consistent with

Figure 1B.

2.2. Functional Features of BPS-2

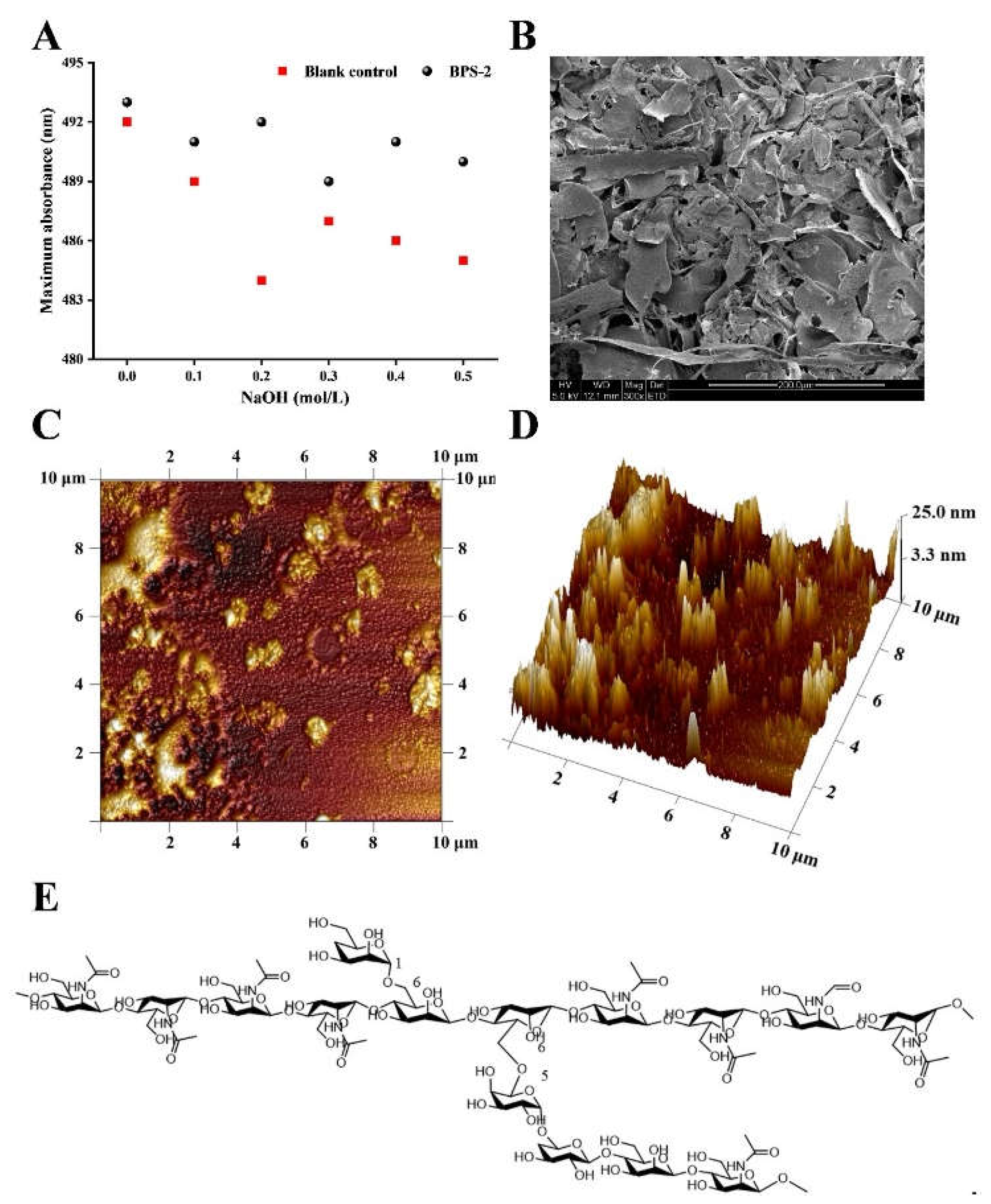

The understanding of the thermal properties of polysaccharides is important in industry. As shown in

Figure 2A, the TG and DSC curves of BPS-2 solid powder varied with increasing temperature. In the DSC curve, BPS-2 showed a strong endothermic transition peak at 126 °C, which represents the loss of water from the polysaccharide [

24]. Two small endothermic peaks were exhibited at 239 and 328 °C, representing the thermal depolymerization of polysaccharides and the breakage of polysaccharide glycosidic bond linkages, respectively [

25]. Interestingly, only two stages of mass loss were observed in the TG curves, describing a mass loss of BPS-2 from dehydration between 70 and 150 °C (6%) and a mass loss of up to 46% due to the decomposition of functional groups between 240 and 350 °C. Below 250 °C, the mass loss of BPS-2 was minimal (13%), but the total mass loss after thermal degradation at 400°C was about 64%. The reason for the massive degradation of BPS-2 above 250 °C is presumed to be due to its mostly straight-chain polysaccharide structure. Some reports suggest that a highly branched polysaccharide structure can effectively increase thermal stability [

26]. In summary, BPS-2 exhibits good thermal properties below 250 °C and can be processed at high temperatures to improve the material thermal stability.

To clarify further the crystal structure of BPS-2, its XRD spectrum was analyzed. The results showed that BPS-2 has two clear diffraction peaks, indicating the presence of two crystal structures (

Figure 2B). The diffraction peak of BPS-2 at around 2θ=10° indicated a type I hydrated crystal structure, and the strongest diffraction peak at around 2θ=20° corresponded to the type II crystal structure [

27]. The type II crystal structure in the BPS-2 molecule is probably due to the monosaccharides with acetyl groups on their side chains, whereas the corresponding type I hydrated crystal structure originates from the monosaccharides with acetyl groups on the main chain [

28].

The rheological analysis was performed to investigate whether BPS-2 was viscous, with the viscosity of the polysaccharides positively correlated with the concentration [

29]. As shown in

Figure 2C, the apparent viscosity of the BPS-2 solution increased with increasing concentration (1-5% w/v) and decreased with increasing shear rate, exhibiting a non-Newtonian behavior. In the food industry, it is important to ensure the stability of polysaccharides under different pH conditions that exist in the stomach and small intestine. The apparent viscosity of BPS-2 solution gradually increased with decreasing pH and decreased with increasing shear rate (

Figure 2D). However, the apparent viscosity of the BPS-2 solution at pH 3 was much higher than that of the other solutions, presumably because the acidic pH caused the acetyl groups on the straight chains of BPS-2 to be shed, resulting in the exposure of the polysaccharide hydrogen bonds to the coagulation effect, thus greatly increasing the apparent viscosity.

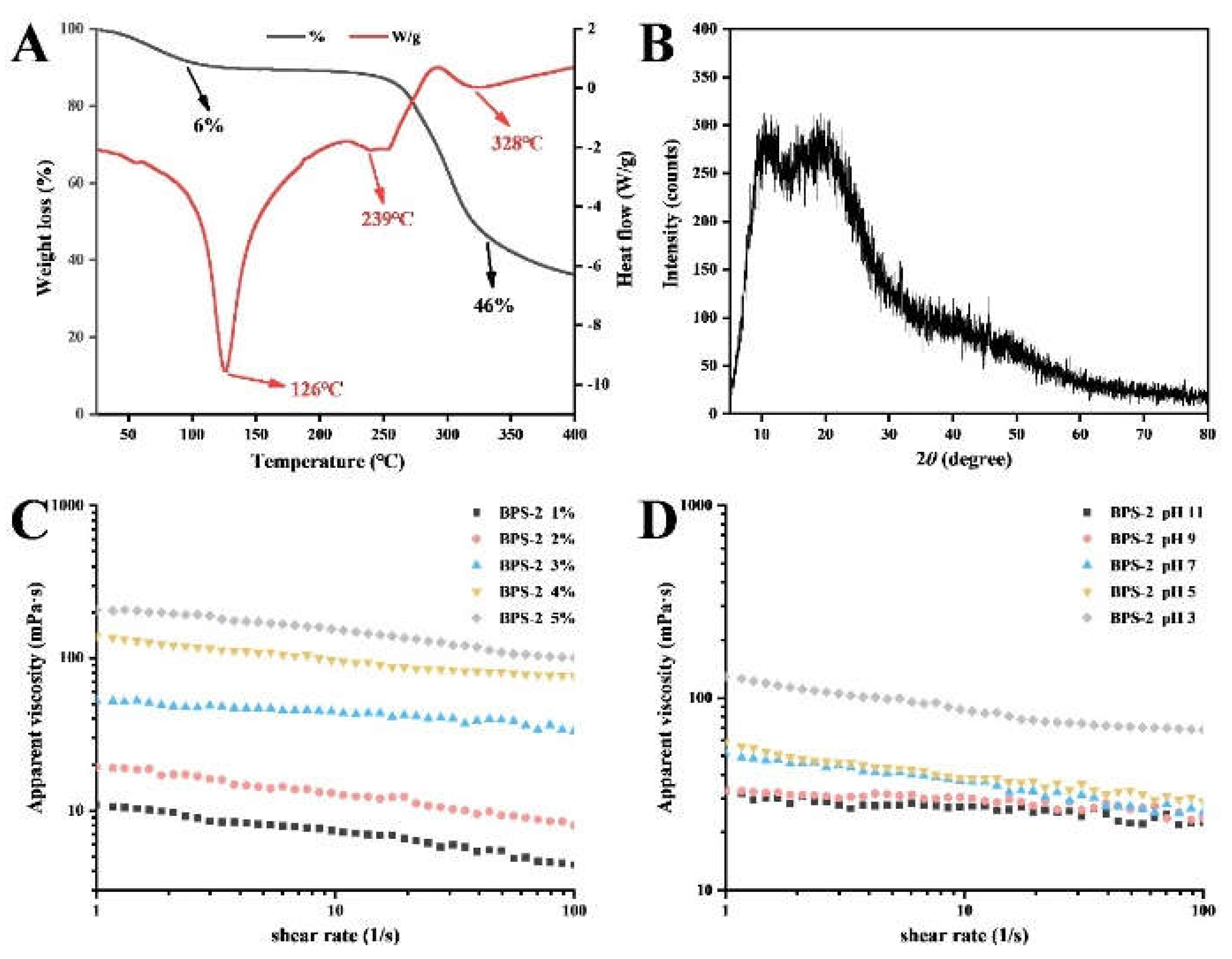

2.3. Antioxidant Capacity of BPS-2

Figure 3 shows sequentially the antioxidant capacity of BPS-2 estimated by the DPPH, hydroxyl, superoxide anion, and ABTS radical scavenging assays. The BPS-2 showed a dose-dependent trend (0.5-4.0 mg/mL) for each free radical scavenging capacity. Among them, the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC

50) of DPPH, hydroxyl, superoxide anion, and ABTS radical scavenging of BPS-2 were 3.81, 2.89, 2.98, and 2.62 mg/mL, respectively. The antioxidant capacity (IC

50) of BPS-2 reported in the present study was similar to the extracellular chitinous polysaccharide isolated by Mamani et al from

Mortierella alpina [

30]. In addition, BPS-2 contains 63% of aminosaccharides (D-GalN and GlcN) similar to chitin-like extracellular polysaccharide components, and the reason for the antioxidant capacity of such components is that free radicals interact readily with the hydroxyl or amine groups of chitin to form stable macromolecular ligands [

31].

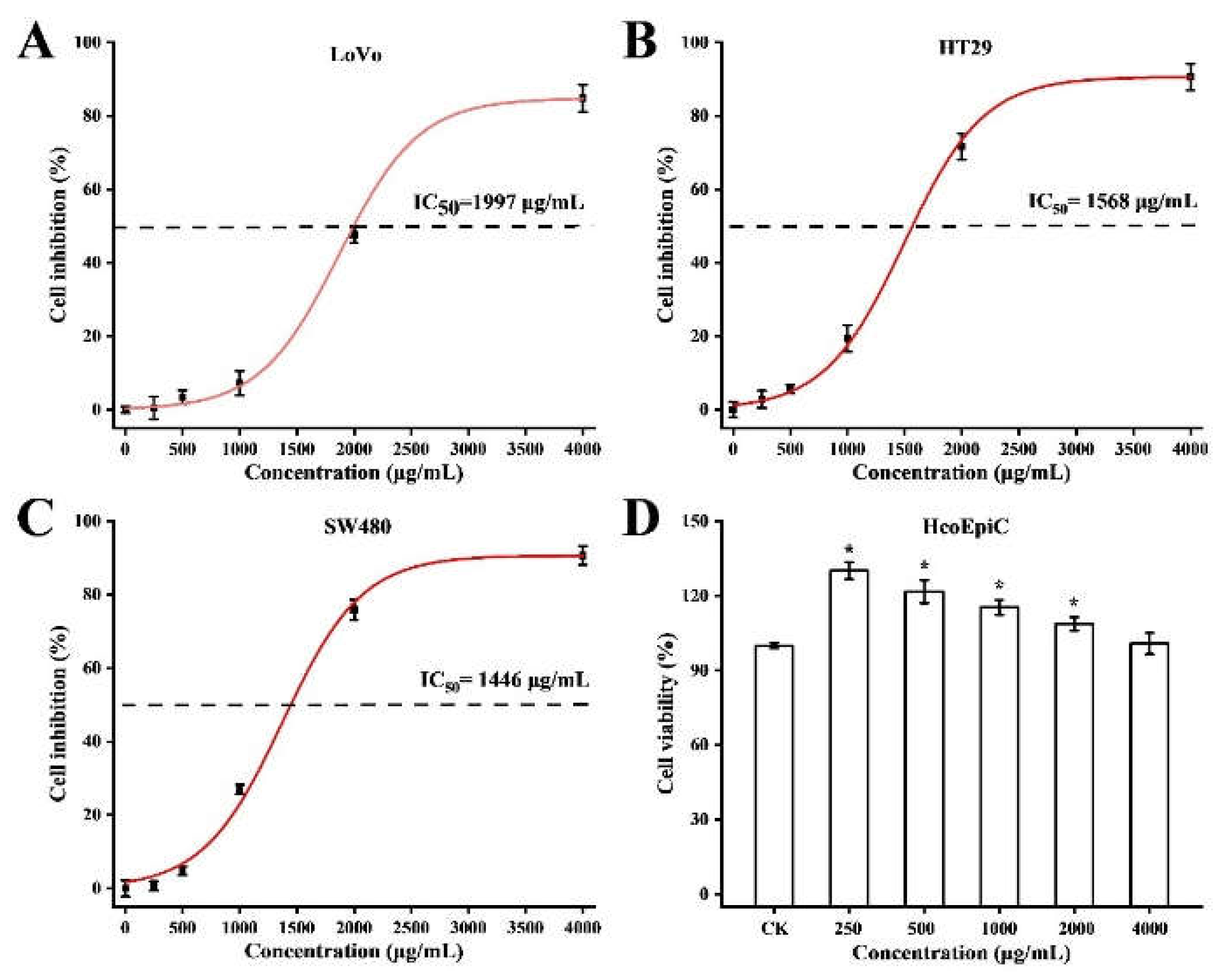

2.4. Anticancer Activity of BPS-2

Cancer is a serious health problem worldwide, with more than one million new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) being diagnosed each year [

32]. Despite some scientific advances in recent years, the prognosis for CRC patients remains unsatisfactory, with an overall survival rate of about 50% over 5 years [

33]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for effective CRC therapeutics, and the wide variety of microbial natural polysaccharides were tested as part of the screening for drugs targeting many types of cancer cells.

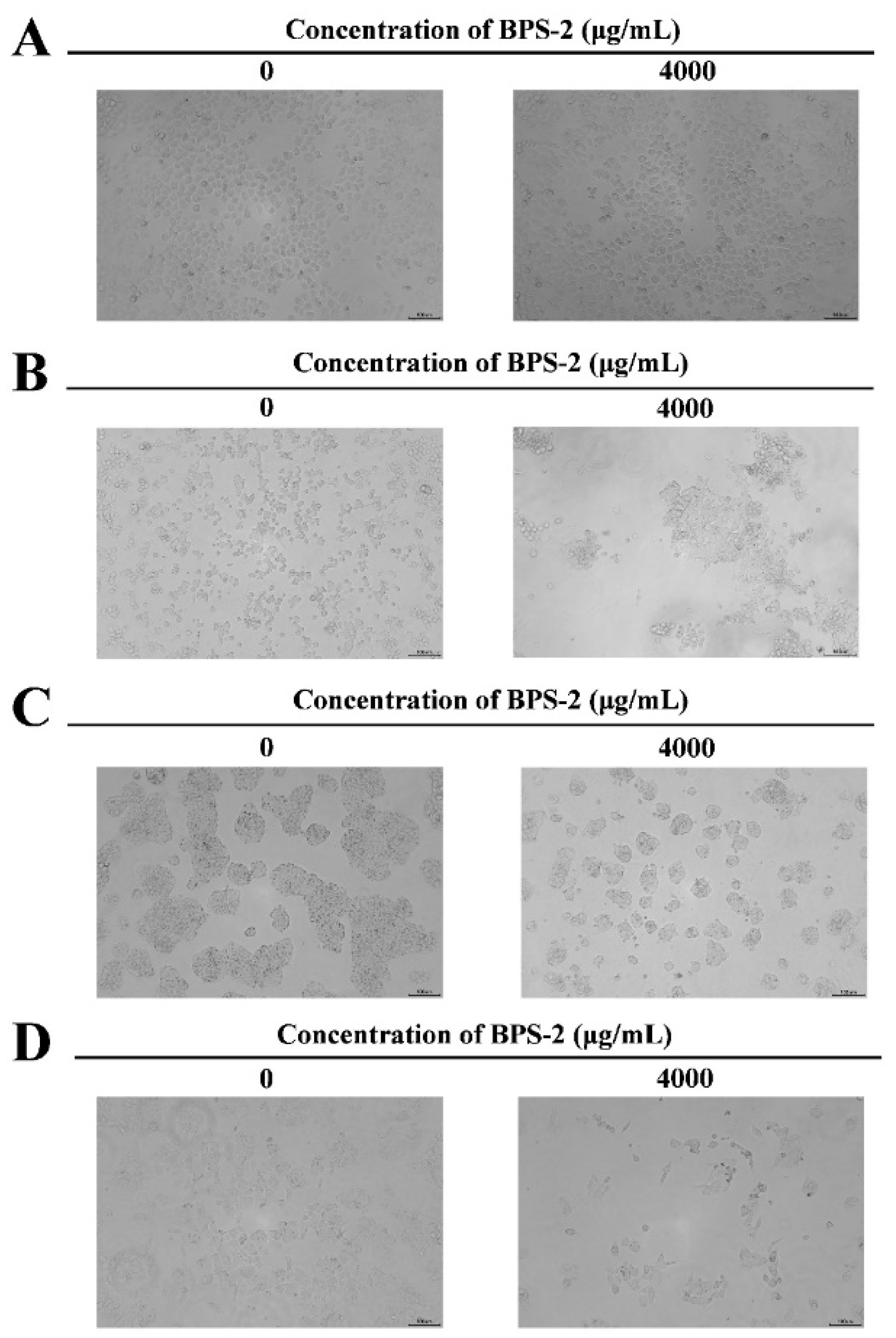

Considering that BPS-2 was a potential natural dietary supplement that could be applied as an anti-cancer compound, we selected HcoEpiC, LoVo, HT29, and SW480 cell lines for testing the cytotoxic potential of BPS-2 by

in vitro MTT assay (

Figure 4). As shown in

Figure 5, at the BPS-2 concentration of 4000 μg/mL, it exhibited significant cytotoxicity against human colorectal cancer cell lines LoVo, HT29, and SW480, and the morphology of the three cell lines was significantly altered on microscopic examination, whereas BPS-2 did not significantly change the morphology of cultured human normal colonic epithelial cells HcoEpiC. The cytotoxicity of BPS-2 on LoVo, HT29, and SW480 cell lines is shown in

Figure 4A-C. The IC

50 values for LoVo, HT29, and SW480 cell lines were 1997, 1568, and 1446 μg/mL, respectively. The percentage of growth inhibition by BPS-2 increased in a dose-dependent manner for all three cancer cell lines. It was shown

in vitro that electrical charge is essential for antitumor activity, and that highly charged chitin derivatives trigger the apoptotic pathway in cancer cells. BPS-2 may be highly charged due to its high aminosaccharide content, and the results of the

in vitro anticancer activity tests showed significantly higher anticancer properties compared with the chitin derivatives reported by Mamani et al [

30], which may be attributed to the specific sugar molecular unit on the BPS-2 branched chain.

BPS-2 of B. thuringiensis IX-01 has showed high anticancer activity and could be a candidate for further studies, but in vivo animal tests and human clinical trials are still needed to evaluate its precise effect on tumor cells.

2.5. Effect of BPS-2 on SCFAs

SCFAs, particularly acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are important metabolites of the intestinal microflora and play a key role in maintaining several physiological functions of the host [

34]. It has been demonstrated previously that BPS-2 is highly resistant to artificial saliva, gastric juice, and small intestinal fluid, with no significant changes in polysaccharide molecules; hence, BPS-2 reaches the colon without difficulty [

20]. In this study, fecal bacteria from two healthy individuals and four UC patients were used for

in vitro fermentation in BGR using the BPS-2 treatment and the control (starch), and the concentration of SCFAs was measured after 48 h (

Figure 6).

After 48 h, the concentrations of total SCFAs produced by fermentation of BPS-2 by intestinal bacteria in different volunteers (NO. 1-6) were 60.29 ± 2.68, 54.25 ± 3.91, 42.31 ± 3.62, 49.06 ± 4.73, 64.15 ± 3.01, and 49.84 ± 1.83 mM (

Figure 6D); these values were significantly higher than the blank and the control group. The reason for the lower concentration of SCFAs in the blank group was that the intestinal barrier absorbs SCFAs. The fermentation of BPS-2 and the control group (starch) in vitro by BGR, which reflected the difference in the capacity of intestinal bacteria to convert different polysaccharide substances into SCFAs.

Rice is one of the staple foods of East and Southeast Asians, and starch is the main component of rice grain. In the control group, starch was selected as the reference compound. After 48 h of fermentation, two healthy individuals produced significantly (P < 0.05) higher levels of propionic acid, butyric acid, and total SCFAs than the four UC patients (

Figure 6B-D). It indicated that intestinal bacteria were less capable of using starch to produce SCFAs in UC patients than healthy individuals.

Propionic acid reduces obesity by modulating immune cells in the host to achieve lower levels of fatty acids in the liver and plasma [

34]. Butyric acid is an important energy supplier for colon cells and plays a key role in regulating the proliferation and differentiation of the colon epithelial cells, and it induces apoptosis in the colon cancer cells [

35]. Interestingly, after 48 h of fermentation, UC patients in the BPS-2 group (NO. 3-6) showed a significant increase in total SCFAs, with patient (NO. 5) having a significantly (P < 0.05) higher level of total SCFAs relative to the others (

Figure 6D).

In summary, BPS-2 promotes the production of SCFAs, especially propionic acid and butyric acid, by intestinal bacteria in the healthy subjects and the ulcerative colon patients.

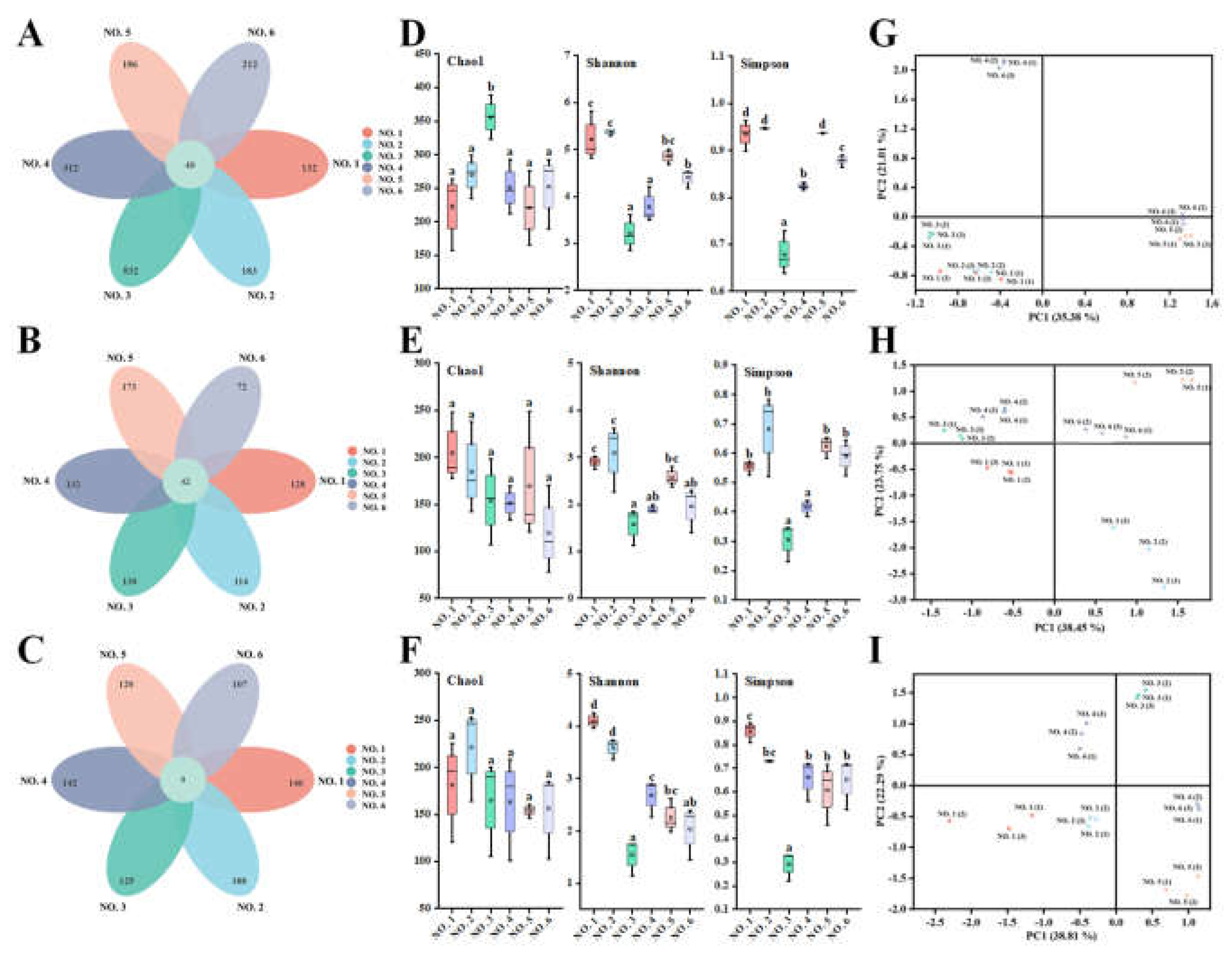

2.6. Intestinal Bacterial Diversity Analysis

As shown in

Figure 7A-C, 40 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were shared among the initial gut bacteria of different volunteers, whereas 42 and 9 OTUs were shared when starch and BPS-2 were the main sources of ingested carbon, respectively. It indicated that when BPS-2 was used as the main carbon source, the abundance of the same species of gut bacteria significantly decreased in different volunteers, and the change in the species of gut bacteria was significantly (

P < 0.05) higher than in the initial and starch groups. It is worth mentioning that the OTUs of the four UC patients in the initial group were significantly (

P < 0.05) higher than the OTUs of the two healthy individuals, but the OTUs converged to the same level after

in vitro fermentation was performed separately. It is possible that this phenomenon was caused by the higher abundance of harmful bacteria in the intestinal bacteria of UC patients compared with that of healthy individuals, and that

in vitro fermentation was transferring harmful bacteria from an otherwise suitable environment for growth to an unfavorable environment, resulting in a significant death of harmful bacteria.

The initial, fermented starch and BPS-2 gut bacterial α-diversity values of different volunteers are shown in

Figure 7D-F. No significant differences were found in the intestinal bacteria Chao1 index of volunteers in different environments, except for the volunteer NO. 3 who had a more significant (

P < 0.05) Chao1 index at the beginning, indicating that individual differences among people still exist. In addition, the Simpson and Shannon indices of initial gut bacteria and after fermented starch and BPS-2 treatments showed almost identical trends across the volunteers, with the two healthy ones being more significant on both indices than the four ulcerative colon patients, suggesting that the diversity of human gut bacteria is better in healthy individuals than in ulcerative colon patients. The flora composition (assessed by PcoA analysis) was similar in the two healthy individuals (

Figure 7G-I), whereas the four UC patients had significantly different flora. Overall, the use of BPS-2 as the primary carbon source did not result in a reduction in the diversity of gut microbiota relative to starch as the control, which is normal for

in vitro fermentation of the intestinal flora relative to the initial reduction.

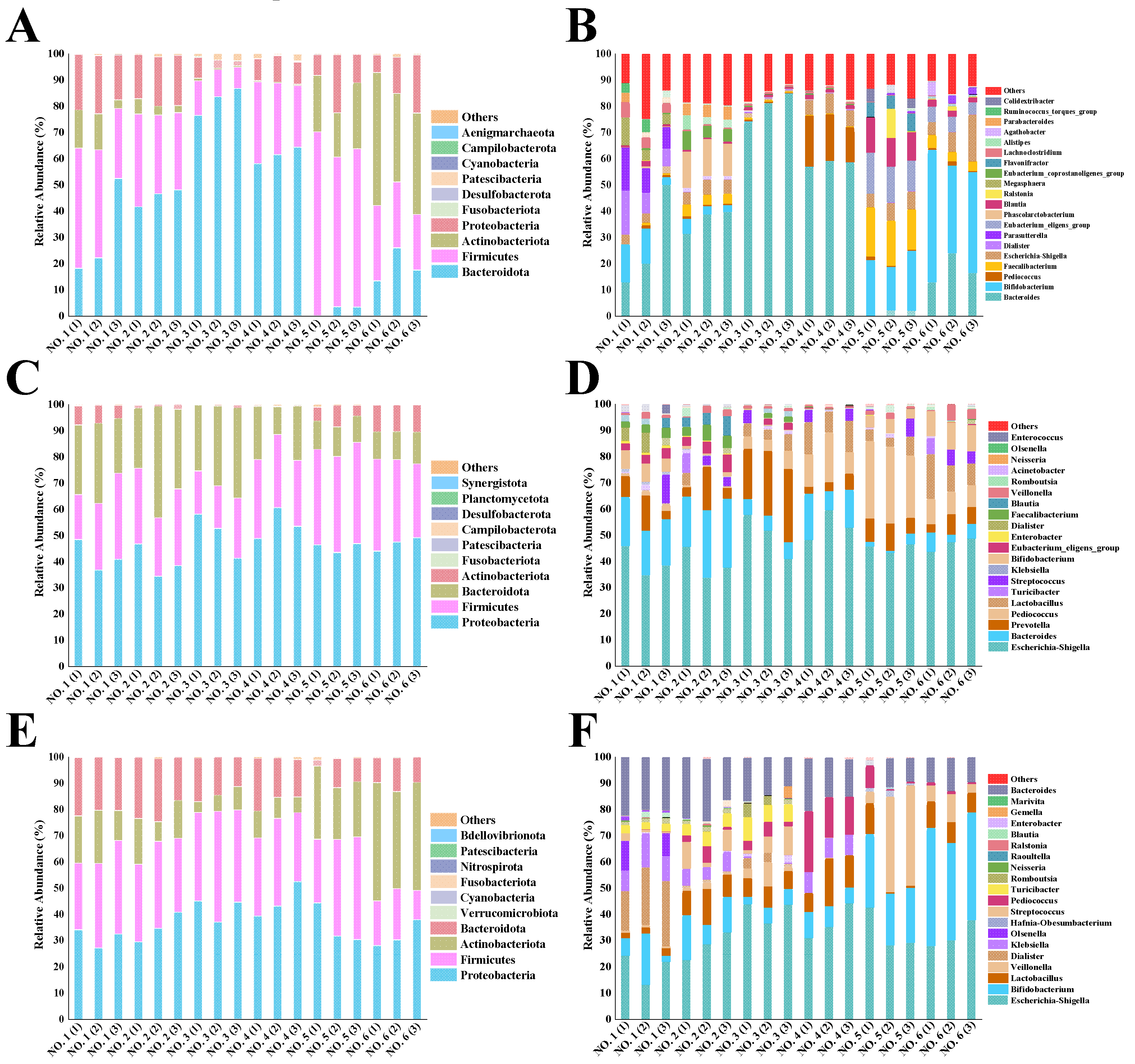

2.7. Composition of the Intestinal Community

In the natural world 52 bacterial phyla are known to exist, but only 5-7 bacterial phyla are detectable in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract. The huge microbial community provides a mutually beneficial and functional treasure trove for the host, contributing to energy harvesting channels, and maintaining the normal functioning of the immune system and the production of essential vitamins; however, the flora can also have a detrimental effect in case of disease [

36]. To reveal the specific composition of the initial gut microbial community in different volunteers, we assessed microbial differences at varus taxonomic levels. At the phylum level (

Figure 8A), four dominant bacterial phyla were identified in the six volunteers. Among them, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria had the combined relative abundance of more than 90%. Usually, the percentage of Firmicutes in the intestinal flora shows a negative relationship with gastrointestinal inflammation, whereas a significant increase in Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes and a significant decrease in Firmicutes is found in UC patients [

37].

Figure 8B shows the genera of the initial gut flora of the six volunteers. Volunteers NO. 1 and NO. 2, as healthy individuals, had more balanced intestinal flora. The initial flora of ulcerative colon patients was particularly strange compared to the intestinal flora of the two healthy individuals. The relative abundance of

Bacteroides in ulcerative colon patients NO. 3 and NO. 4 was as high as 80% and 58%, respectively, while the relative abundance of Firmicutes was only 10% and 26%. This phenomenon was detrimental, as the disruption of intestinal flora of UC patients was accompanied by a decrease in the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes [

38]. Interestingly,

Bifidobacterium was detected in two UC patients (NO. 3 and NO. 4) at 20% and 40%, respectively, which are not low percentages of the overall flora, and both patients indicated they had not ingested probiotics within a month (

Table 1); thus,

Bifidobacterium in these two individuals might have been ingested and got established in their gut flora since more than one month ago. However, the UC patients NO. 3 and NO. 4 showed the relatively low abundance of Bacteroidetes at 2% and 20%, respectively; it should be kept in mind that an imbalance in the relative abundance of either Bacteroidetes or Firmicutes in the intestinal flora is an important indication of adverse health effects.

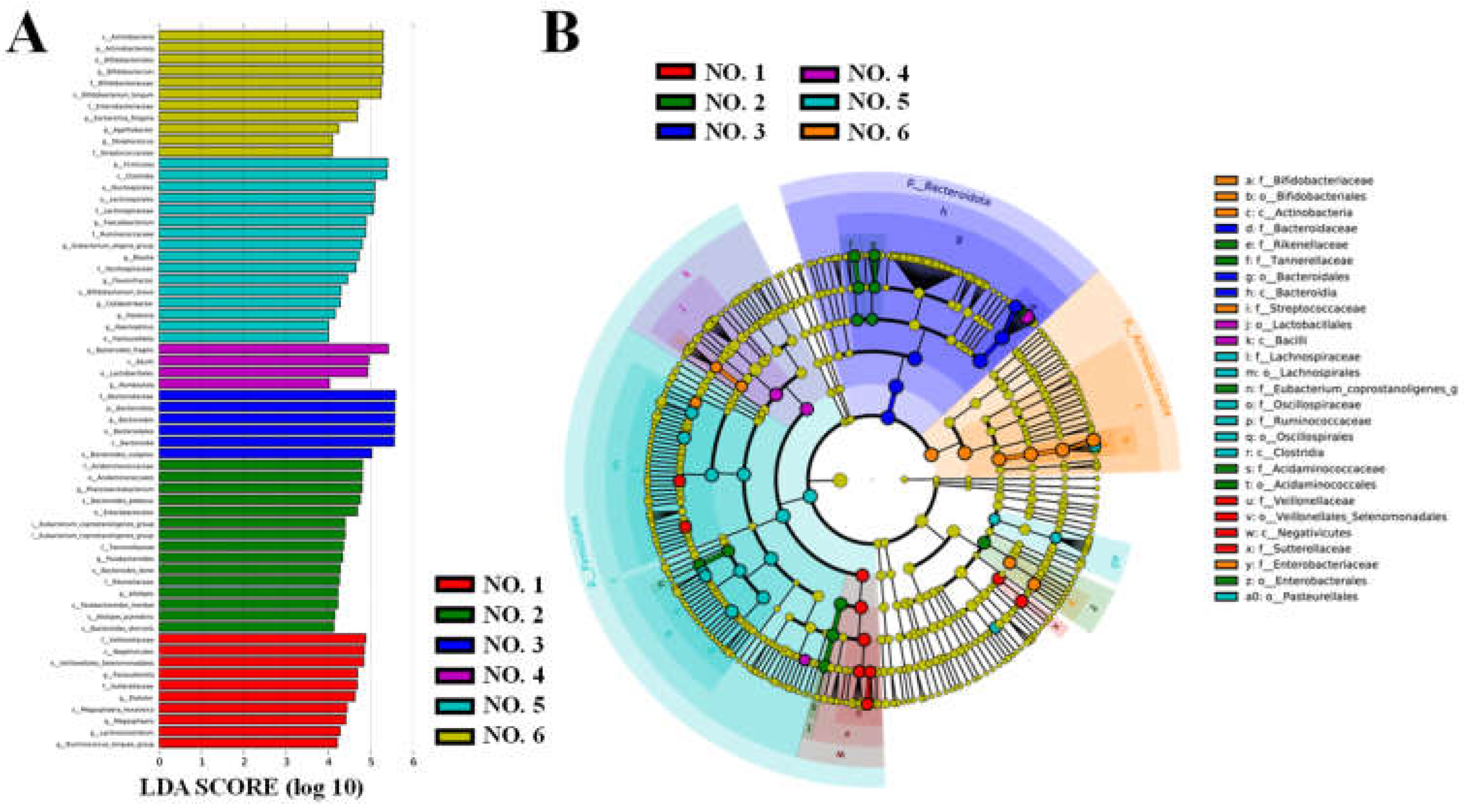

LefSe analysis was performed to identify statistically significant biomarkers of gut microbiota in the initial gut flora of the volunteers (

Figure 9). As shown in

Figure 9A, 62 taxa were found to differ significantly (

P < 0.05) between groups at the phylum, order, family, genus, and species levels in the initial gut flora of different volunteers. Significantly enriched intestinal flora are indicated by the corresponding nodes, and their taxonomic levels are shown by line discriminant analysis (LDA) score distribution cladogram in

Figure 9B. In the healthy volunteer NO. 1,

Parasutterella was enriched significantly; it has a role in maintaining bile acid stability and coordinating cholesterol metabolism in the host [

18]. By contrast, significant enrichment of

Bacteroides fragilis and

Escherichia-Shigella was identified in the UC patients NO. 4 and NO. 6, respectively, as the hallmark flora that may cause inflammation [

39].

As shown in

Figure 8C, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria increased in different volunteers after 48 h of fermentation in BGR. The reason for the increased abundance of Proteobacteria could be attributed to their likely reliance on polysaccharides with high glucose content for reproduction; straight-chain starch is one such polysaccharide. Among human intestinal microorganisms, Proteobacteria include mainly

Shigella,

Salmonella, and

Escherichia, and these genera may be associated with intestinal inflammatory diseases. Therefore, reducing the abundance of the above-mentioned genera is beneficial to the health of the host [

40]. In comparison, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria increased less with the intake of BPS-2 than starch (

Figure 8E).

The relative abundance of Actinobacteria in the intestinal flora of each volunteer increased relative to the other groups after BPS-2 intake. It might be that 1,4-β-GaINAc and 1,4-β-GlcNAc as the main components of BPS-2 can promote the increase of relative abundance of Actinobacteria.

Considering the genera shown in

Figure 8F, the main increase in the relative abundance of Actinobacteria was due to the contribution of

Bifidobacterium.

Bifidobacterium, a probiotic associated with human health, is closely related to the production of butyric acid as well as having the function of enhancing the intestinal mucosal barrier and reducing the level of inflammation [

12]. Notably, the intake of BPS-2 resulted in a more balanced relative abundance of intestinal flora in the six volunteers relative to the intake of starch (

Figure 8D, F). Among the UC patients, the microbial community composition of the UC patient NO. 3 was already similar to the two healthy individuals (NO. 1 and NO. 2), suggesting BPS-2 improved the colonic flora of the UC patient NO. 3. In addition, macromolecular polysaccharides could potentially have a higher safety profile, lower toxicity, more pronounced prebiotic activity (especially for UC disease), as well as undergo continuous degradation during fermentation in the gut, leading to a more balanced production of SCFAs due to a mild fermentative effect produced by the complex structure [

41]. Thus, a BPS-2 capacity to promote the production of SCFAs by the UC gut flora suggests that BPS-2 has the potential to improve UC gut health.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Reagents

EPS-rich

B. thuringiensis IX-01 was isolated from Pixian pea sauce from Sichuan, China. The strain has been conserved in China Centre for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC M 2020486), and the 16S rRNA sequence was deposited in NCBI with the registration number OL687443. The detailed method for the preparation of BPS-2 from IX-01 was described in the previous report [

20]. Congo red reagent, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) standards, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemical reagents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

3.2. Congo Red Test

The three-helical structure of BPS-2 was probed by the Congo red test according to Xu et al [

42]. A BPS-2 sample (5 mg) was supplemented with 2.0 mL of distilled water and 2.0 mL of 0.08 mol/L Congo red reagent, and then different volumes of 1.0 mol/L NaOH solution were added to bring the NaOH solutions to concentrations 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 mol/L. After thorough mixing, the spectra were scanned in the range of 400-600 nm by a U-3900 spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The maximum absorption wavelengths at different NaOH concentrations were recorded. For blank control, distilled water was used to replace the BPS-2 samples, and the other steps specified above were repeated.

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) Analyses

The surface morphology of the polysaccharides was studied by a Quanta 200 FEG SEM (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands). BPS-2 powder (3.0 mg) was fixed with double-sided adhesive carbon tape and then sprayed with gold under low vacuum conditions to make it conductive. SEM photographs were then obtained. Afterwards, the BPS-2 solution was heated to 85 °C for 10 min and filtered through a 0.22 μm aqueous phase filter membrane to obtain the solution for the assay. A 2.0 μL aliquot of BPS-2 (0.01 μg/mL) solution was added dropwise on the surface of mica flakes and was then air-dried for Multimode 8-HR AFM (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) measurements.

3.4. Thermogravimetric (TG) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analyses

The TG performance of BPS-2 was tested by a Q500 TG analyzer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). A 2.0 mg sample was placed in a ceramic crucible for TG analysis. The test conditions were temperature 25 °C-400 °C and the heating rate 20 °C/min. The thermal properties of BPS-2 were tested by a Q200 DSC (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). A 2.0 mg sample was placed in a metal crucible for DSC analysis. The test conditions were temperature 25 °C-400 °C and heating rate 20 °C/min.

3.5. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

The crystal structure of BPS-2 was assessed with a D2 PHASER XRD (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). The detection conditions were scanning angle range of 5°-80° (2θ), scanning rate of 2θ=0.1 °/s, and data acquisition by continuous scanning.

3.6. Rheological Measurements

The apparent viscosity was measured by an MCR302 interfacial rheometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria). Different solutions containing 1%-5% w/v BPS-2 (pH 7.0) and different pH solutions containing 3% w/v BPS-2 (pH 3-11) were used to measure the steady-state rheological properties of EPS. Using 0.6 mL of different assay solutions, the detection was carried out at 25 ℃ using a 25 mm parallel splint, with the clamping distance set to 1.0 mm and the shear rate of 1-100 s-1.

3.7. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity was evaluated for DPPH, superoxide anion, hydroxyl, and ABTS radical scavenging activities as reported previously [

43].

3.8. Anticancer Activity

Human colorectal cancer cell lines (SW480, HT29, and LoVo) and human normal colonic epithelial cell line (HcoEpiC) were provided by the Shanghai Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The four cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, HyClone; Logan, Utah, USA) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum with the addition of penicillin (100 μg/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). The cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The effect of BPS-2 on the growth of four cell lines was assessed in vitro by a MTT assay.

The cells were dispersed with 0.25% trypsin and adjusted to approximately 3×104 cells/well in culture plates containing 100 μL of medium, and the cells were cultured for 24 h for apposition and were then supplied with 100 μL of fresh medium. Different concentrations (0-4000 μg/mL) of BPS-2 (100 μL) were added to the medium in each well. The cells were incubated for 24 h and microphotographs were taken. The medium containing BPS-2 was removed, and the attached cells were incubated in the medium containing 10 μL MTT solution for 3 h. After the change of solution, 200 μL DMSO was added, and the cells were shaken for 10 min at 25 °C. The absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

3.9. Fermentation of EPS by Fecal Flora of Volunteers

The fresh stool samples were collected from two healthy volunteers and four UC volunteers. These donors all followed a normal Chinese Jiangsu diet, as detailed in

Table 1. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Wuxi Second People’s Hospital, Wuxi, China (ethics number 2020002). All volunteers provided written informed consent agreeing to participate in the study. Feces were collected in sterile sealed containers and transported at low temperatures for use on the same day. The feces of each volunteer was diluted with sterile 0.1 M PBS at a ratio of 1:10 (w/v). The fecal homogenate was filtered through six layers of sterile gauze, and the filtrate was collected for inoculation. Basal fermentation medium (pH 5.8) contained (g/L): yeast extract 3.0, casein 2.0, tryptone 1.0, Tween 80 1.0, KCl 1.0, L-cysteine 0.5, NaCl 0.5, K

2HPO

4 0.5, KH

2PO

4 0.5, bile salt 0.4, CaCl

2·6H

2O 0.15, hemin 0.025, FeSO

4·7H

2O 0.005, and MgSO

4·7H

2O 0.01. We also added 1 mL of vitamin mixture (g/L): pantothenic acid 10.0, nicotinamide 5.0, para-aminobenzoic acid 5.0, thiamine 4.0, D-biotin 2.0, menadione 1.0, and vitamin B12 0.5. According to the study objectives, we added 5 g/L BPS-2 and 5 g/L starch for the treatment and the control, respectively, to the basal fermentation medium.

The bionic gastrointestinal reactor (BGR) was developed by our laboratory as an

in vitro digestion model [

44]. In this study, a colonic reactor of BGR was used (

Figure S1). To the reactor, 180 mL of fermentation basal medium was added, heat-sterilized and cooled, and 20 mL of treated fecal homogenate was inoculated at a ratio of 1:10 (v/v). After inoculation, a temperature-controlled circulation pump was connected to maintain the internal temperature at 37°C. The N

2 was passed for 5 min to simulate an anaerobic environment in the intestine, maintaining the pH at 5.8-6.0. The fermentation medium was replenished with 30 mL of fresh medium every 8 h. The intestinal community was incubated for 24 h to reach a stable stage. This stage was set as the initial fermentation time, followed by feeding 30 mL of fermentation medium every 8 h. The experiment was terminated after 48 h of fermentation. Samples were collected and stored at -80 °C for testing.

3.10. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

The bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using universal primers 341F (5’-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3’) / 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). After sequencing, the 16S rRNA sequence data were bioinformatically analyzed according to the published methods [

45].

3.11. Determination of SCFAs

The SCFAs were determined on a 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). To 1 mL of fermentation supernatant, we added 10 μL of internal standard of 2-methylbutyric acid (1 mM), 250 μL of hydrochloric acid, and 1 mL of anhydrous ethyl ether followed by vortexing for 5 min. Organic phase was collected, dehydrated with anhydrous sodium sulfate, and filtered through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane. The chromatographic column was an HP-INNOWax column (Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The detector temperature was 250 ºC, and the injector temperature was 220 ºC. The oven temperature was started at 60 ºC and increased to 190 ºC after 4 min. Samples (5 μL) were injected with N2 carrier gas at a split ratio of 1:20. The concentration of SCFAs was calculated using an external standard method.

3.12. Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Statistically significant values were compared by ANOVA, and Dunnett’s test was used for multiple comparisons.

4. Conclusions

The study was based on the exploration of the multifunctional activity of BPS-2 (a derivative of GAGs synthesized by B. thuringiensis IX-01 through high-cell-density fermentation) and its potential applications. BPS-2 is a high-molecular-weight straight-chain polysaccharide with glucosamine and galactosamine as the backbone. Compared to other EPS reported in the literature, BPS-2 exhibited good functional properties in terms of thermal stability and rheological properties, and antioxidant and anticancer activity. In addition, it was confirmed that BPS-2 has a promising effect on the composition of the intestinal flora of UC patients while promoting the production of SCFAs. Thus, BPS-2 has a potential as a functional food to improve UC, but further in vivo experiments are needed to explore its mechanism of action in detail and to assess its safety as a food additive.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, and Writing-Original draft preparation, Z.G.; Investigation, Formal analysis, and Software, J.T., C.W., and W.D.; Writing-review, Supervision, and Investigation, X.W., Y.L., and Y.W.; Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, and Project administration, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160668), Engineering Research Center of Health Medicine biotechnology of Guizhou Province (Qian Jiao Ji No [2023]036), Rapid Breeding and Efficient Cultivation and Developing Applications of High Quality Grass Seedlings (Qian ke he KY [2018] 088), Isolation of active substance of Rhzopcnis vagum AS-6 strain, an endophytic fungus from Paris polyphylla and the mechanism of inhibitory effects on colorectal cancer (Qian ke he ZK [2022] 364), the High-Level Talent Initiation Project of Guizhou Medical University (J[2023] 072).

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciated Dr. Zichao Wang for valuable suggestions in preparing manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zhang, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, H. Identification of an endophytic fungus pilidiella guizhouensis isolated from Eupatorium chinense L. and its extracellular polysaccharide. Biologia. 2020, 75, 1707–1715. [CrossRef]

- Nicolaus, B.; Kambourova, M.; Toksoy Oner, E. Exopolysaccharides from extremophiles: From fundamentals to biotechnology. Environmental technology. 2010, 31, 10, 1145–1158. [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Feng, J.; Sun, P.; Xiang, N.; Lu, B.; Qiu, D. Recent advances in improving stability of food emulsion by plant polysaccharides. Food Research International. 2020, 137, 109376. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lai, Z.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, N. Effect of monosaccharide composition and proportion on the bioactivity of polysaccharides: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127955. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, R.; Chen, M.; Huang, A.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammation effects of dietary phytochemicals: The Nrf2/NF-κB signalling pathway and upstream factors of Nrf2. Phytochemistry. 2022, 204, 113429. [CrossRef]

- Cutting, S.M. Bacillus probiotics. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 2, 214–220. [CrossRef]

- Crickmore, N.; Zeigler, D.R.; Feitelson, J.; Schnepf, E.; Van, R.J.; Lereclus, D.; Dean, D.H. Revision of the nomenclature for the Bacillus thuringiensis pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Blol. R. 1998, 62, 3, 807–813. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Geng, L.; Xue, B.; Wang, Z.; Xu, W.; Shu, C.; Zhang, J. Structure characteristics and function of a novel extracellular polysaccharide from Bacillus thuringiensis strain 4D19. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 956–964. [CrossRef]

- Jallouli, W.; Driss, F.; Fillaudeau L.; Rouis, S. Review on biopesticide production by Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Kurstaki since 1990: Focus on bioprocess parameters. Process Biochem. 2020, 98, 224–232. [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, S.; Gnanakan, A.; Lakshmana, S.S.; Meivelu, M.; Jeganathan, A. Structural characterization and anticancer activity of extracellular polysaccharides from ascidian symbiotic bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis. Carbohyd. Polym. 2018, 190, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.S.; Shin, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.E.; Han, H.S.; Rhee, Y.K.; Cho, C.W.; Hong, H.D.; Lee, K.T. Protective effect of exopolysaccharide fraction from Bacillus subtilis against dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis through maintenance of intestinal barrier and suppression of inflammatory responses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 178, 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jin, Y.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.; Chen, W. Alleviation effects of Bifidobacterium breve on DSS-induced colitis depends on intestinal tract barrier maintenance and gut microbiota modulation. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1, 369–387. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Shen, M.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Chen, T.; Xie, J. Alleviative effects of natural plant polysaccharides against DSS-induced ulcerative colitis via inhibiting inflammation and modulating gut microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2023, 167, 112630. [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Ji, X. An insight into anti-inflammatory effects of natural polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 248–255. [CrossRef]

- Murch, S.H.; MacDonald, T.T.; Walker-Smith, J.A.; Levin, M.; Lionetti, P.; Klein, N.J. Disruption of sulphated glycosaminoglycans in intestinal inflammation. Lancet. 1993, 341, 8847, 711–714. [CrossRef]

- Mneimneh, A.T.; Mehanna, M.M. Chondroitin Sulphate: An emerging therapeutic multidimensional proteoglycan in colon cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127672. [CrossRef]

- Waseem, T.; Ahmed, M.; Rajput, T.A.; Babar, M.M. Molecular implications of glycosaminoglycans in diabetes pharmacotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 247, 125821. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, W.; Qi, S.; Xue, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, L. Effects of dietary phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin on DSS-induced colitis by regulating metabolism and gut microbiota in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 105, 109004. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Hong, Y.; Zeng, X. Preparation, antioxidant and antitumor activities in vitro of different derivatives of levan from endophytic bacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa EJS-3. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3–4, 767–772. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wu, C.; Wu, J.; Zhu, L.; Gao, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhan, X. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of an aminoglycan-rich exopolysaccharide from the submerged fermentation of Bacillus thuringiensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 1010–1020. [CrossRef]

- Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Rodríguez-González, V.M.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Eim, V.; González-Centeno, M.R.; Femenia, A. Effect of different drying procedures on the bioactive polysaccharide acemannan from Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller). Carbohyd. Polym. 2017, 168, 327–336. [CrossRef]

- Balnois, E.; Stoll, S.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Buffle, J.; Rinaudo, M.; Milas, M. Conformations of succinoglycan as observed by atomic force microscopy. Macromolecules. 2000, 33, 20, 7440–7447. [CrossRef]

- Lambo-Fodje, A.M.; Leeman, M.; Wahlund, K.G.; Nyman, M.; Larsson, H. Withdrawn: molar mass and rheological characterisation of an exopolysaccharide from pediococcus damnosus 2.6. Carbohyd. Polym. 2006, 68, 3, 577–586. [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Adhikari, R.; Kasapis, S.; Adhikari, B. Molecular and functional characteristics of purified gum from Australian chia seeds. Carbohyd. Polym. 2016, 136, 128–136. [CrossRef]

- Archana, G.; Sabina, K.; Babuskin, S.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Sukumar, M. Preparation and characterization of mucilage polysaccharide for biomedical applications. Carbohyd. Polym. 2013, 98, 1, 89–94. [CrossRef]

- Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Structural characterization, functional properties and antioxidant activities of polysaccharide extract obtained from okra leaves (Abelmoschus esculentus). Food Chem. 2021, 354, 30, 129437. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, Y.L.; Yang, W.L.; Wang, C.C.; Hu, J.H.; Fu, S.K. Synthesis and characterization of a novel amphiphilic chitosan-polylactide graft copolymer. Carbohyd. Polym. 2004, 59, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, W.; Liang, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y. Effects of ultrasonic treatment on the molecular weight and anti-inflammatory activity of oxidized konjac glucomannan. CyTA-J. Food. 2019, 17, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, P.P.; Huang, Q.; You, L.; Liu, R.; Zhao, M.; Fu, X.; Luo, Z. A comparison study on polysaccharides extracted from Fructus Mori using different methods: structural characterization and glucose entrapment. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3684–3695. [CrossRef]

- Goyzueta M, L.D.; Noseda, M.D.; Bonatto, S.; Freitas, R.A, Carvalho, J.C.; Soccol, C.R. Production, characterization, and biological activity of a chitin-like EPS produced by Mortierella alpina under submerged fermentation. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020, 247, 116716. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Xu, P.; Liu, Q. Antioxidant activity of water-soluble chitosan derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 13, 1699–1701. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tian, H.; Wang, L. Effects of PTEN on the proliferation and apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells via the phosphoinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 4, 1828–1836. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Song, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, K.; Han, B.; Bai, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L. MicroRNA-21 (Mir-21) promotes cell growth and invasion by repressing tumor suppressor PTEN in colorectal cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 3, 945–958. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Shen, M.; Guo, X.; Huang, L.; Yang, J.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Cyclocarya paliurus polysaccharide alleviates liver inflammation in mice via beneficial regulation of gut microbiota and tlr4/mapk signaling pathways. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 164–174. [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; Vadder, F.D.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016, 165, 6, 1332–1345. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.X.; Lee, J.S.; Campbell, E.L.; Colgan, S.P. Microbiota-derived butyrate dynamically regulates intestinal homeostasis through regulation of actin-associated protein synaptopodin. PNAS. 2020, 117, 21, 11648–11657. [CrossRef]

- Faith, J.J.; Guruge, J.L.; Charbonneau, M.; Subramanian, S.; Seedorf, H.; Goodman, A.L.; Clemente, J.C.; Knight, R.; Heath, A.C.; Leibel, R.L.; Rosenbaum, M.; Gordon, J.I. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science. 2013, 341, 6141, 1237439. [CrossRef]

- Fábrega, M.J.; Rodríguez-Nogales, A.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Algieri, F.; Badía, J.; Giménez, R.; Gálvez, J.; Baldomà, L. Intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of outer membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in DSS-experimental colitis in mice. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1274. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, W.; Wu, J.; Zhu, L.; Gao, M.; Zhan, X. Encapsulation of polyphenols in pH-responsive micelles self-assembled from octenyl-succinylated curdlan oligosaccharide and its effect on the gut microbiota. Colloid. Surface. B. 2022, 219, 112857. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Aweya, J.J.; Huang, Z.; Kang, Z.Y.; Bai, Z.H.; Li, K.H.; He, X.T.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Cheong, K.L. In vitro fermentation of Gracilaria lemaneiformis sulfated polysaccharides and its agaro-oligosaccharides by human fecal inocula and its impact on microbiota. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020, 234, 115894. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Qiu, Z.; Gu, D.; Wang, F.; Zhang, R. A novel anti-inflammatory polysaccharide from blackened jujube: Structural features and protective effect on dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitic mice. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 30, 134869. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Xue, S.; Pan, Y.; Chen, S. Effect of alkali-neutralization treatment on triple-helical aggregates and independent triple helices of curdlan. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 259, 117775. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Bao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhai, J.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, H. Characterization and anti-inflammation of a polysaccharide produced by Chaetomium globosum CGMCC 6882 on LPS-induced raw 264.7 cells. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 251, 117129. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, G.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhan, X. In vitro digestion and fecal fermentation of highly resistant starch rice and its effect on the gut microbiota. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 11, 130095. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Wu, C.; Yin, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Li.; Gao, M.; Zhan, X. Structural characterization and in vitro evaluation of the prebiotic potential of an exopolysaccharide produced by Bacillus thuringiensis during fermentation. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 163, 113532. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).