1. Introduction

Electronic and digital applications and systems are increasingly used in medical and healthcare fields. A thorough and comparative review can provide a useful perspective, benefiting researchers in this area. While some reviews cover aspects of digital healthcare and medical electronics, there is a lack of in-depth comparison of different applications. For example, in [

1], medical devices from the last 100 years have been reviewed, discussing medical imaging, nuclear medicine imaging, modern surgical techniques, and biomedical sensors. The implantable medical electronics have been discussed in 23 chapters in [

2]. Some other recent works show a review on the recent digital healthcare systems, such as references [

3,

4,

5].

This paper reviews the most recent electronic and digital applications and systems in medical and healthcare fields. It covers key topics such as wearable electronic applications, the Medical Internet of Things (M-IoT), electronic healthcare record systems, smartphone applications, Virtual Reality (VR) systems, Artificial Intelligence (AI), flexible hybrid electronics, electronic and digital healthcare during COVID-19, medical sensors, social media and websites, Blockchain technologies, electronic drug delivery systems, Nano-BioElectronics, and robotic surgery systems.

The paper compares the advantages and disadvantages of various aspects, including social media and websites in medicine, robotic surgery systems, VR systems in medicine, and medical data management systems using blockchain technology. Additionally, it includes other comparisons that provide a useful perspective in the field.

2. Wearable Electronic Applications

The evolution of technologies like flexible hybrid electronics has been the driving force for constructing miniaturized vital sensors, helping people maintain their physiological well-being and monitor their diseases. One of the branches that grew out of the idea of applying biomedical devices in wearable objects (especially textiles) is Textronics. Textronics (or "Smart textiles") is an umbrella term for a diverse range of textile-based devices serving different functionalities, e.g., sensing, communication, energy storage and harvesting, heating, etc [

6]. Disregarding the purpose of textile-based devices, they are manufactured similarly and use similar resources to incorporate individual components into a system, e.g., conductive yarns [

7], functional fabrics [

8], or inkjet printing of conductive onto a piece of cloth [

9]. This group of devices can be divided into two groups: passive and active. Passive smart textiles can sense the environment but not actively react to external stimuli. Typically, they don't require an external power supply. Active groups are appliances integrating actuators or some implemented logic to perform reactive sensing and interact with the outer world. This category generally uses an external power delivery system or contains an energy storage/harvesting mechanism [

10].

2.1. Internal Structure of a Devices

Textronics, as opposed to classical electronic devices, are characterized by technologies that perform certain circuit features like interconnections, antennas, and sensing functionality.

Previously, conductive fibers were used in many different areas, such as part of antistatic applications [

11], electromagnetic interference shielding [

9], infrared absorption [

12], or protective clothing in explosive areas [

9]. In this particular field, they found usage as an interconnection medium. A further step in developing technology for conductive yarns was incorporating them into larger, more complex fabric structures. The simplest structure of incorporating conductivity with a fabric is, e.g., weaving the material out of yarn wires described in the previous chapter [

13]. The next generation of conductive fabric was born in the Electronics Department and the Wearable Computing Laboratory at the ETH in Zürich. The new material (PETEX) consists of a grid of copper alloy wire (with a diameter of 50±8 um) separated by fibers of woven polyester monofilament polyester thread (PET) [

13].

2.2. Vital-Signs Data Processing - Data Mining Methods for Wearable Devices

One of the most significant impacts on the wearable electronic area was the growing computational possibilities of miniature System on Chip (SoC) solutions. Researchers have recently moved from simple data collecting towards more complex processing systems like those based on neuronal networks, classifiers, and mathematical signal processing methods. Predominantly processing systems implemented in wearable electronic devices can be categorized into three groups based on their targeted operation [

14]:

Estimation of future patients' physiological well-being based on measurements.

Abnormality detection of bio-indicators collected by sensors.

Diagnosis based on the characteristics of individual diseases and the best fit for the collected data.

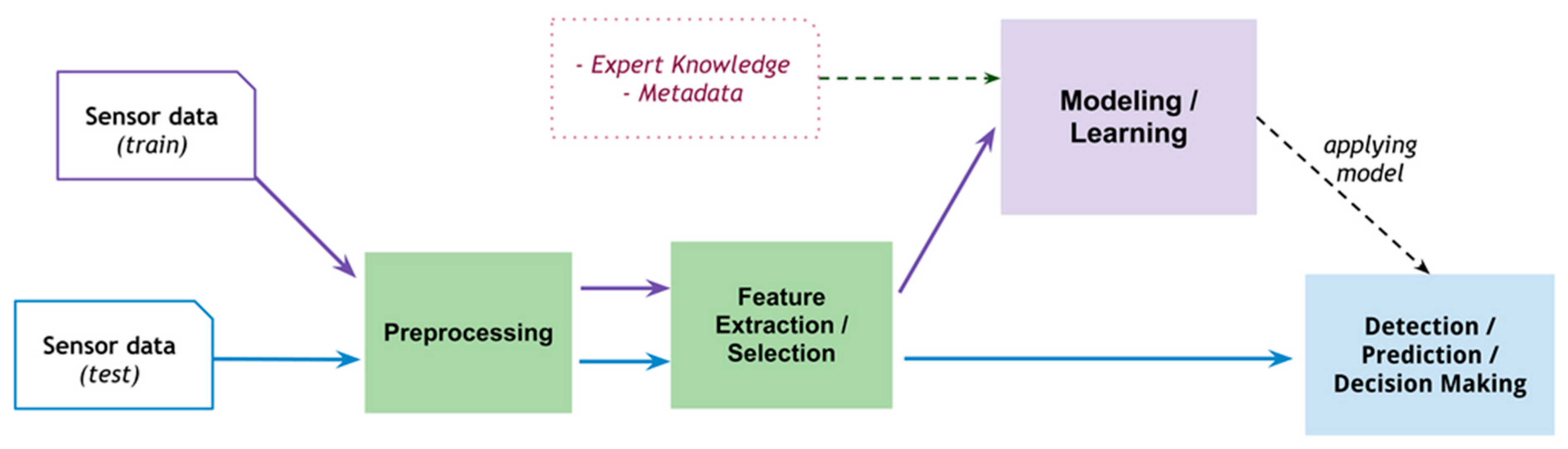

In the context of prediction, diagnosis, and decision-making solutions, such systems are designed as a bigger or smaller variation of what is given in

Figure 1. Shown architecture is a basic example of machine-learning algorithm implementation in wearable devices. The whole chain consists of various stages, including preprocessing, feature extraction or selection, and application of a machine-learning model.

2.3. Prediction of Patient's State

Estimating future events influencing the general health state is a primary task of preventing diseases, allowing detection of early symptoms of worsening well-being, and giving a chance to perform actions before developing severe health conditions. The most common realization of this approach is that learning models (like the temporal abstraction model used in the mentioned studies) are trained on large sets of sampled data, such as heart rate during various situations, blood oxygenation, etc. [

15]. Examples of such implementations of predictive algorithms can be brought:

- -

Body area network (BAN) consisting of various types of sensors implementing a prediction model of someone's future stress level [

16].

- -

A complex glucose level/physical activity monitoring system utilizing data from ambient sensors across the house, wearable sensors, and data collected from blood glucose monitor devices [

17].

- -

Model of predicting hemodialysis patients' general well-being and estimation of hospitalization risk of individual [

18].

2.4. Diagnosis Methods and Abnormality Detections

Wearable hardware utilizing data mining shows the supremacy of its construction as a diagnostic tool with constant monitoring functionality. The task, in contrast to the previously mentioned one, is more sophisticated due to the complexity of the whole system based on more complex data, including detected patterns of abnormalities from bio-sensors or patients' medical reports [

19]. However, one of the most frequent solutions for implementing such a decision-making model in the diagnostic process is implementing some classification method like a Neuronal network [

20] or decision tree [

21]. Examples of wearable systems fulfilling diagnostic needs can be an automatic diagnostic system for:

- -

Coronary artery disease, by deducing further health information from heart rate patterns [

19]

- -

Apnea based on ECG and blood saturation patterns [

20]

- -

Insomnia, sleep fragmentation, and disorders in the sleep macrostructure by performing polysomnography [

22]

An essential part of the diagnostic approach is high-quality data with the least amount of artifacts in sensor signals. Among the available methods for the preprocessing stage are:

- -

Threshold-based methods.

- -

Statistical tools allow the interpolation of lacking data points.

- -

Classical signal processing approaches include Fourier analysis and low-pass/high-pass filtering of incoming sensor signals.

Final data after preprocessing are necessary for the last part of the mentioned data mining functionalities, abnormality detection. Depending on the implementation, the algorithm searches for irregularities in an incoming signal or compares it with the predefined dataset, and, based on this information, it judges a patient's health state in real time.

2.5. Wearable Sensors

A crucial element of any health-related wearable system is its ability to measure biomarkers and bio-indicators, providing reliable information about the patient. Also, recent years have brought us new designs and constructions, allowing us to extend available measurement principles of biosensors.

2.6. Optical Sensors

One of the major categories of detectors measuring biochemical response is based on the optical properties of a tissue or bodily fluid, like Raman scattering, fluorescence, or colorimetric.

2.7. Colorimetric Sensors

Colorimetric sensors work on the principle of the light's wavelength shift of the material's absorption spectrum in response to chemical compounds in the environment. A typical application of this method is an absorbent epidermal hydrogel-based patch infused with active substances like tannic acid or polyacrylic acid [

23].

Typical applications of this technology are ions and biomarkers detection in bodily fluids (e.g., sweat), like in a proposed system where the proposed solution was directed onto the detection of glucose and enzymatic oxidation by sampling patients' saliva [

24].

2.8. Fluorescence Sensors

Fluorescence sensors are detectors relying on a fluorometric agent encapsulated with a sample. The presence of target analytes like glucose, chloride ions, sodium ions, or zinc ions influences the light intensity of sensors. [

23]. One example of Fluorescence-based measurements in health monitoring is a Smartphone-coupled dermal sensor analyzing sweat concerning glucose, lactate, chloride, pH, and volume [

25].

2.9. Photoplethysmography (PPG)

Photoplethysmography is a method of measurement based on light passing through a tissue or internal organs like veins or arteries and an approximation of their properties considering their absorption. By utilizing PPG, it is possible to detect the oxygenation level of veinous blood and pulse rate classically, like pulse rate monitors, a common measuring technique [

26].

2.10. Interferometry

Interferometric sensors detect changes in optical length path, phase shift, or polarisation of light in contact with analyzed tissue. A common way to implement such a method is by incorporating in the structure different types of micro-interferometers like Fabry–Perot [

27] and Mach–Zehnder [

22] or by using another technique of measuring optical length paths like Bragg grating [

28]. This broader type of optical sensor also finds its place in a wide spectrum of bio-measurements like blood pressure monitoring [

27], cardiovascular complex diagnosis systems [

28] or respiratory monitoring [

29].

2.11. Pressure Sensors

The clinical approach of utilizing various sensors was initially focused on performing investigations like ECG, EMG, and EEG. In the case of pressure sensors, their major application was a part of blood pressure measurement equipment. In recent years, the arsenal of available applications was widened by further research, and pressure sensors found use also in early-stage Parkinson’s disease detection [

30], intracranial pressure measurements [

31] or arterial stiffness diagnosis [

32].

Table 1 summarizes research conducted in terms of optical and mechanical sensors and their area of usage.

3. Medical Internet of Things (M-IoT)

The Internet of Things, also known as IoT, is the next step towards the evolution of the Internet. The fundamental concept of this network is to collect, share, and process data without human supervision. Although the World Wide Web was invented by Tim Bernes-Lee in 1989, some people believe that the first example of an IoT application was created in 1982 at Carnegie Mellon University. After several improvements had been made, a local Coke machine was ready to report the amount and temperature of the beverage inside [

42].

Such an opportunity to create a system that could extend diagnostic – this time with full-time tracking of patients’ life parameters - led to the introduction of IoT to healthcare. That brought numerous benefits, including remote monitoring, lowering medical personnel expenses, more personalized care, and even supporting surgeries [

43].

Long-term tracking systems allow for data collection and finding unobvious physiological reactions that may be an early sign of a developing disease. The following sections illustrate some recently created IoT solutions that answer current medical challenges.

3.1. EOG Glasses

Scientists emphasize the importance of monitoring Eye Blinking (EB) in people at risk of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [

44]. EBs can be counted by measuring potential between two sides of the human eye (the front and the back). To achieve that, the Italian-German scientists created a prototype of glasses equipped with electrodes that form a simple ElectroOculoGram (EOG) [

45]. The noticeable drawback compared to traditional EOG systems is the placement of electrodes: usually, they are supposed to be in specific areas of a face. However, it is compensated by comfortable placement for long-time data gathering. The position is a natural consequence of contact points between the glasses and the patient’s head. The comparison between these two approaches reveals that satisfying results of Eye Blinking tracking can be obtained by both optimal configuration and glasses configuration with adapted filtering.

3.2. Wireless EEG

ElectroEncephaloGraphy is a non-invasive method of monitoring brain activity. Conventional EEG devices consist of many electrodes attached to the scalp during the examination. Scientists developed an ear-EEG technique to overcome the inconvenience of extensive equipment preventing long-time data acquisition. It involves placing electrodes in the area in or around an ear, which provides skin-to-electrode contact (without excessive hair), the comfort of use and enables sleep monitoring and emotion recognition. The main challenge of this solution is its size, which imposes restrictions [

46].

3.3. Pandemic Monitoring

The development of IoT systems is also connected with the COVID-19 pandemic. It affected several areas of applications, including:

- -

Detection of diseases at an early stage

- -

Full-time monitoring of infected people

- -

IoT-based neural network systems that predict the pandemic development [

47].

3.4. Fog Computing

The development in the M-IoT field is more than just a growing number of applications. This is only possible with the growth in recent technologies, such as fog computing.

Fog computing, also known as edge computing, is a service created to improve the efficiency of a network while processing an exponentially growing number of data coming from sensors. Instead of conducting all the operations in a cloud, several computations are moved to the edge of an infrastructure - close to the data source [

48]. An application can be divided into three layers: the thing, the fog, and the cloud. Although the cloud layer would be responsible for providing the data for both deep automated and human-performed analysis, the fog layer would give the service response time needed in emergencies [

49]. This is why this technology became an answer to challenges in healthcare, in which time is a crucial factor in saving human life.

Let us consider an example of a framework designed to predict diabetes [

50]. It performs calculations on both mentioned levels. The cloud is responsible for making predictions in association with machine learning. According to [

50], it reaches an accuracy of almost 90%. However, this procedure takes time. To improve the level of analysis, the implementation was equipped with the fog component that provides real-time verification using fuzzy logic. Although it reached an accuracy of only 64%, it significantly developed tool capabilities.

Moreover, energy consumption is a crucial issue that needs to be considered by an engineer during the design process. One of the solutions for IoT devices is to reduce data transfer, which requires postprocessing to reconstruct the original information [

51]. Fog computing can be an answer to the problem of compression and filtering of medical images. Files obtained from ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography, usually containing 3D pictures, are extensive. A high compression ratio, a crucial factor in lowering network traffic, can be reached shorter if more techniques are added to the fog layer rather than other components [

52].

Considering all the examples, several crucial improvements brought by M-IoT can be named:

- -

Real-time analysis

- -

Comfort of use in long-time data acquisition

- -

Remote monitoring.

On the other hand, the challenges for further development are:

- -

Low energy consumption

- -

Improving the analysis’ effectiveness indicators.

3.5. Other M-IoT Applications in Healthcare:

- -

Monitoring and alarming systems for cancer care [

53,

54],

- -

Smart monitoring for heart failure patients [

55],

- -

Orthopaedics applications: collecting data about fractured bones and other deformations, post-surgical recovery [

56],

- -

Colonoscopy diagnosis [

57],

- -

Anaesthetic depth control [

58],

- -

Smart orthodontic brackets [

59],

- -

Pregnancy monitoring systems [

60].

4. Electronic Healthcare Record System

Medical records were introduced in 1907 at the Mayo Clinic as a patient-centred system of storing and sharing medical data [

61]. Since then, the system has developed and changed its structure and content, but the central concept of its operation has stayed the same for almost a century [

61]. Today's medical records play an important role in everyday life. They are not only used as records of the care given to patients anymore but also as means of communication between healthcare teams, as sources of information for research or support for administrative, financial and epidemiological purposes. To provide efficient health care, they must be distributed between many care providers, often in real-time. This need creates many problems that can even have deadly consequences. Approximately every year, more Americans die from preventable errors in hospitals than from breast cancer, AIDS or motor accidents [

62,

63]. To reduce medical errors, improve patient safety and care quality, increase healthcare service delivery efficiency and decrease healthcare costs, scientists and researchers began to work on a new system of electronically distributing data [

64,

65,

66]. The effect of their work, called electronic healthcare record system (ECHR), is officially referred to as a "repository of patient data in digital form, stored and exchanged securely, and accessible by multiple authorised users" [

61].

Although works on it have been ongoing for years, the system remains incomplete. One reason for this is that ECHR must combine various applications with different formats and standards, such as data, graphics, sound or video [

61]. In principle, ECHR should enable patients to manage their healthcare system with the help of evidence-based clinical protocols and guidelines [

61]. Moreover, care should be integrated or shared so that an individual's healthcare is the responsibility of a team of professionals across all healthcare sectors, not just one doctor [

61]. In a perfect world, it would be a system that prioritizes promoting wellness over treating diseases by automatically monitoring patients' medical data on an ongoing basis and proposing actions to prevent diseases.

However, these requirements remain beyond the reach of modern ECHR. There are many reasons why ECHR is not working as it is wished and cannot be introduced at a larger scale. One of the most significant issues is under-investment in Information and Communication Technology (ICT), especially in clinical computing. With a lack of political will and government support for development, it is nearly impossible to create a working system for creating and adopting new standards. It is also problematic that many countries still do not have a national master index and, therefore, do not have any consensus on the unique identification of patients [

67]. However, the key challenge remains the need for more human resources [

67]. Many healthcare workers, especially in South Africa, have not received computer training. This general lack of awareness of the risks and benefits of going with ECHR among healthcare workers and patients creates wariness and reluctance toward the system, making it impossible to introduce beneficial changes [

68]. These are only a few challenges researchers must face to make the Electronic Healthcare System fully functional and working. More of them are shown in

Table 2.

It is unknown how long it would take to change the medical record system to a system that allows multidisciplinary teams of doctors to coordinate treatment interventions and share data, enabling patients to manage their medical care fully and aware [

69]. For now, the impact of most eHealth technologies is either negligible or, at best, modest [

70]. One can only hope that in the coming years, ECHR will be developed enough to be introduced into general use, thus changing health care as we know it.

5. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The terms Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are used interchangeably sometimes as a name for technology created to make decisions that were only the domain of humans in the past. We can define AI in many ways: machines’ ability to communicate with people via ‘chat’ while not being recognized (the Turing Test), fulfilling the tasks that require human intelligence, systems, and algorithms for classification, decision-making, and research [

71]. It comprises several subfields, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP), Deep Learning (DL), and (already mentioned) machine learning (ML) [

72]. The statistical nature of medical issues with incomplete data, personal differences between patients, noisy signals from overlapping diseases, different courses of diseases, etc., is why medicine is one of the main targets for AI tools [

73].

5.1. Machine Learning

Machine learning is a technology based on learning from a set of training data to make further predictions about other examples by a machine. ML is a competition for humans for pattern recognition, as it may identify symptoms and diseases that are difficult to grasp [

74]. It is applied in fields in which classical computations would be challenging to perform due to the complexity of an issue. However, a large set of input examples is required to teach the algorithms the desired behavior.

ML can be used in image processing for feature extraction [

75]. For example, it enables early bone cancer detection from Computed Tomography pictures in DICOM format with an F1 score of 92.68% [

76]. It provides segmentation of mammography images for the detection of breast cancer – the most lethal cancer for women [

77].

ML is a tool for working with massive data sets. Thus, it is applicable in data mining of DNA [

78]. Numerous efficient ML tools analyze heart parameters for successful disease classification [

79]. Data mining with ML algorithms was also developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand the problem better [

80].

Although the future of ML remains unknown, the development of other technologies significantly impacts it. This is why Quantum Machine Learning (QML) was introduced. It is still at an early research stage, but has already been proven to reduce the algorithm's complexity and accelerate the tasks exponentially [

81].

5.2. Deep Learning

DL is a subcategory of ML. Its architecture is mainly based on Neural Networks (NN) with multiple layers of nonlinear processing entities – neurons [

82]. Such representation allows for more complexity in data processing than conventional methods, which is highly recommended for unstructured, heterogeneous data collected in medical cases [

83].

The area of applications of DL is similar to that of ML. It can be used to classify clinical images in search of pathologies [

84], extend diagnostic [

85], or enhance the value of conventional clinical procedures, such as DL-supported PET imaging [

86].

Multi-task Deep Learning (MTDL) is an extension of DL's functionality. This technology aims to perform several operations simultaneously while optimizing loss functions [

87]. Most MTDL networks operate on images, and many support examining areas such as the brain, chest, cardiac system, or musculoskeletal [

87].

5.3. Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is also area of AI. It is a field in which Artificial Intelligence meets linguistics as it is a technology processing text – it explores relationships between parts of language and tries to gain the meaning of phrases [

88]. As a significant part of healthcare data is stored in a written form, several applications of NLP emerged: analyzing records for drug discovery, classifying radiology reports without human input, and specialized chatbots for patients [

89].

NLP not only covers the need to process existing texts but also can have a generative form. An example of such a Large Language Model (LLM) is GatorTronGPT. It uses ChatGPT-3 architecture combined with training with 82 billion words of clinician texts and 195 billion words from other writing. After six days of training the model, it became a tool for synthetic clinical text generation [

90].

Artificial Intelligence is a technology widely used in healthcare. The summary of applications of ML, DL, and NLP according to previous paragraphs is shown in

Table 3.

6. Flexible Hybrid Electronics

In the last century, medicine has undergone tremendous progress, and new approaches to diagnostics and treatment have been developed thanks to the harmonic development of medicine within the technical environment. The invention of the first technological aids like the stethoscope in 1816 or the discovery that freshly invented X-rays could be used to image the inside of the human body (the first X-ray photograph of a hand was created by Röntgen in 1895) were breakthrough events in the history of medicine [

91,

92]. Nowadays, people are used to the existence of new technological achievements that are related to medicine. One of the novel promising technologies for medical-related usage is devices manufactured using flexible hybrid electronics technology (or FHE for short).

New Technologies of high-density electronic systems accelerate the development of design techniques for devices in various sectors. One of the novel methods is Flexible Hybrid Electronics (FHE). FHE is a new design concept based on a flexible substrate. The critical difference that makes this technology distinguishable from flexible PCBs is the way of treating components of a circuit and methods of integration in a system as a whole. Generally, FHE is based on a flexible interconnecting substrate with printed conducting traces and external elements (like resistors, capacitors, inductors and transistors). This fully additive process opposes conventional manufacturing processes based on subtractive/additive steps like etching or lift-off [

93]. The most significant innovation in the new process is the treatment of used ICs in the circuit. Instead of packaged integrated circuits, bare chip dies are thinned (most often using saw dicing and laser ablation until they achieve final thickness of a few micrometers. Finally, in the thinned version, they are placed on a substrate that interconnects them with the outside world and other components on the board [

94].

6.1. Comparison of Variations in Fully Additive and Conventional Subtractive Processes

At the early stages of FHE development, fully additive processes were characterized by high parameter deviations of printed components. This issue was influential, especially for transistors. The most critically affected properties were the mobility of charge and the threshold voltage of OTFT (organic thin filn transistor), leading to variations of up to ±30% μ [

95,

96,

97,

98]. The growth of available processes delivered us new manufacturing methods with low variations, which were the first candidates to compete with traditional subtractive techniques. The lowest reported fully additive-process variations were ±9.5% μ [

98]. Unfortunately, due to the high cost of using a silicon wafer as a stencil (which limits its size to 300mm), issues with applying the process on a large scale and high temperatures during the process, those methods were unsuitable for operating with PET as a substrate. A substantial milestone in this field was acquiring variations comparable to conventional processes involving photolithography (±4.7% μ) It was feasible to revise the organic semiconductor material. One of the best promising OTFT materials was a blend of TIPS-pentacene with polymer, e.g. polystyrene dissolved in a solvent complex consisting of toluene and anisole. New material allows for lower variations, increased charge mobility, and better management of the uniformity of semiconductor film [

99].

6.2. Challenges to Defeat in the Future

Studies in the domain of Flexible Hybrid Electronics have identified challenges in constructing electrical circuits on flexible substrates. One of the uneasiness in new technology is the influence of convex and concave bending. The main consequence of the actions mentioned above is a variation of the elements' electrical characteristics in the bending radius function [

100]. This phenomenon impacts nearly all printed components (resistors, capacitors, and OTFTs). In the context of OTFTs affected, the most crucial transistor parameter is the drain current under specific polarisation conditions. Research reported diverse deviations (from 5% to 118%) depending on the manufacturing process of the device and the Gate-Source voltage applied to the device under test [

100]. Those drawbacks can be neglected by developing circuits focusing on self-compensating means, e.g. relying on pairs of transistors rather than single elements [

100].

6.3. Medical Related Applications

FHE-based devices are the groundbreaking next step in developing a new class of medical instruments that are smaller, more compact, and more accessible in everyday life. Researchers have already found niches where introducing new flexible and packed construction could show its benefits over bulky and heavy construction.

6.4. Performing Electrode-Based Medical Investigation

One of the development fields where flexible devices have found their place is health monitoring in real-time. Depending on the disease diagnosis, the equipment could consist of additional elements like electrodes (for methods like ECG or EMG) or physicochemical sensors (analyzing bodily fluids and the physical environment of a patient). Solutions take various forms, most often attached to the examined body parts. An example of such an appliance could be dysphagia monitoring system [

101].

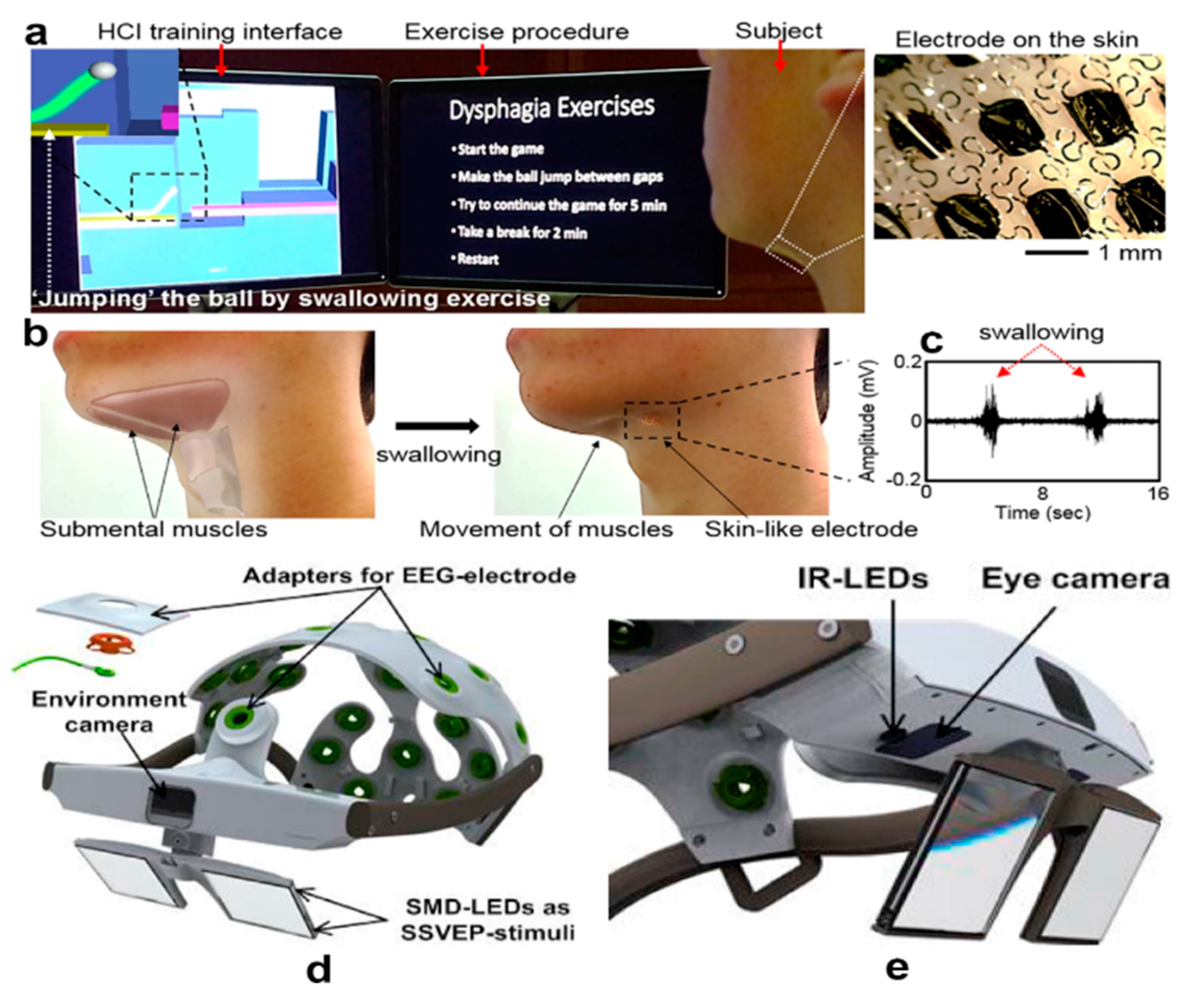

Dysphagia is a medical term describing difficulties in swallowing caused by a broad spectrum of diseases. Nevertheless, the proposed method is shown in

Figure 2b. The system took the form of a patch attached to the bottom side of a jaw and monitored muscle activity in the region by utilizing EMG electrodes to collect signals captured in

Figure 2c. The solution communicates with a computer that performs measurements and processes incoming signals, creating a usable rehabilitation platform shown in

Figure 2a.

Another illustration of fresh air brought by FHE technology is a body-attachable ECG module utilizing soft and hard electronics (including unflexible elements) and integrating electrodes with the necessary equipment (like an analog front-end, Bluetooth SoC for data acquisition, and a small coin cell battery holder) on one Kapton substrate. Besides ECG possibilities, the device beholds a skin temperature monitoring system. One of the usages foreseen by research was monitoring of physiological response (focusing on cardiac reaction) during physical activity [

103].

6.5. Analysis of Bodily Fluids and Patient's Environment

The presence of new space-saving devices attached to a body gives medicine a new opportunity to expand its area of health investigation. One of the noted fields is bodily fluid analysis, especially sweat. The proposed solution comprises a network of various electrochemical sensors connected with a flexible data processing module. The analysis covers quantities like skin, temperature, electrolyte content, and the presence of substances like glucose or lactic acid [

104].

6.6. Measurements of the Surrounding Environment and Estimating Its Health Impact

Another usage of novelty was found in the prevention of damage caused by pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers are created under certain conditions of long-term cut-off of blood flow in specific parts of the skin. Before, medicine did not develop an efficient solution for risk estimation and early detection of them. The presented appliance relies on the principal method of impedance spectroscopy, which utilizes a network of sensors attached to the skin. The network is connected to an external circuit, performing impedance measurements and presenting a result as heatmap presenting the damaged area for analysis by a

physician [

105].

6.7. New Human-Machine Interfaces

Recent years have shown us new possibilities for interacting with machines, including methods relying on bio-indicators like ECG, EMG, or brain activity. One example of such a system is a sensor system emerging electromyography electrode controlling physiological muscle response, creating an HMI interface with a sensorimotor prosthetic. The suggested solution was presented in the form of a multilayer skin patch serving as a sensor frontend for the machinery providing prosthetics control. Patch as such, provided strain sensor, EMG electrodes, and temperature sensor functionality, which together can be translated into sensorimotor commands for prosthetics [

102].

It is worth mentioning the subcategory of HMIs called Brain Computer Interfaces (BCI). The implementation shown in

Figure 2e. contains 22 EEG electrodes connected with two eye-tracking cameras.

Figure 2e. shows a little bit more information about the implemented eye-tracking system, highlighting the position of crucial components. Complex information collected from different brain regions combined with eye movement data can be processed by adaptive signal processing algorithms fitted to a mental state and image recognition algorithms [

102]. The solution is a great example device utilizing flexible FHE with potential usage by disability affected people with no capabilities to manipulate external objects or with limited communicational abilities due to, e.g., paralysis.

7. Social Media and Websites

As a rapidly growing technology, the Internet has answered numerous issues, including those connected to healthcare. According to research carried out in 2014 among Americans, 72% of adult Internet users had searched online for information about different health conditions [

106]. Nowadays, in the era of social media, access to medicine-related content is even easier. We are provided with real-time, free-of-charge data, with the possibility of personal communication and exchanging experiences [

107]. However, the quality of information may differ significantly from various levels of impact to different quality and reliability [

108].

7.1. Raising Awareness

We can observe a strong impact of the Internet on people’s knowledge of healthcare. Most first-time pregnant women use online websites and dedicated apps, and most consider these information sources about pregnancy reliable [

109]. A relationship has been observed between social media campaigns and positive change in behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic [

110]. It was also used to share personal stories of healthcare workers fighting the coronavirus, who helped spread the knowledge in that difficult time [

111]. Internet campaigns on mental health seem to educate and reduce stigma successfully [

112].

7.2. Providing Accessibility

Social media make the world more accessible. For example, it helps people with disabilities to be active by giving them access to information, including education, and enabling online interactions [

113]. As patients share real-life experiences on social media platforms, their accounts provide valuable information for a deeper understanding of their conditions [

114]. It is also a helpful tool in marketing healthcare services: it includes information about medical facilities and feedback from their clients [

115]. To ensure that the information flow is consistent, hospitals have websites designed for patients and workers [

116]. The Internet has become another workplace for doctors –it allows for online consultation– a time and money-saving alternative for conventional appointments [

117].

7.3. Healthcare on Popular Platforms

Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok are among the most popular social media platforms.

Table 4 shows examples of activities in the area of healthcare.

7.4. Benefits and Potential Risks

Besides many benefits, using social media and websites in healthcare is connected to several risks. They are listed in

Table 5, which shows the advantages and disadvantages of the discussed solutions.

Current AI models do not always interpret the data correctly, so medical chatbots are unreliable and need additional training to provide correct advice (although they can have accuracy above 50%) [

126]. Moreover, due to the lack of standardization and general indicators prepared to compare chatbots, the development of this technology may be slower than needed [

129].

Despite raising awareness, social media can harm mental health, especially among young users, who are considered an active group [

127]. Unfortunately, research in this field faces difficulties, such as missing data, because the platforms are not eager to share information with scientists [

130].

Another problem is misinformation, which primarily affects people with limited access to valuable medical information [

128]. It has become a priority in online healthcare information to detect and fight unreliable data, so there is a growing interest in creating applications to deal with this issue [

131].

8. Electronic Drug Delivery Systems

The usage of electronics in medical applications has significantly increased in the past decade. Electronic drug delivery (E-DD) is, without a doubt, a perfect example of it. It is widely used to monitor and track various therapies, from managing diabetes to treating epilepsy [

132]. It might sound like a new concept, but E-DD's first applications and importance were noticed around 40 years ago [

133]. The reason behind the ongoing development of those systems is a patient's appetite for greater functionality and the simplicity of daily drug dosage. During studies in the early 2000s on compliance with prescriptions and doctor's recommendations, a significant correlation was shown between conscientious adherence to therapy and improved health among patients on long-term therapies [

134].

8.1. Forms of Electronic Drug Delivery Systems

There are several ways of delivering drugs to the human body. All of them are equally important due to their use in different cases, depending on the patient's requirements. Electronic transdermal patches deliver medication through the skin, ensuring controlled and continuous drug administration for conditions like motion sickness, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, and smoking cessation. This method maintains steady drug levels and eliminates pulsatile entry into the systemic circulation [

135]. Recently, electronic ion pumps that deliver ions and charge drugs from the source electrolyte have developed a lot. They are electrophoretic delivery devices transporting charged species through ion exchange membranes, offering high resolution and dosage precision without liquid flow. This technology shows promise in addressing therapeutic challenges, demonstrating efficacy in triggering cell signaling, halting epileptiform activity, influencing sensory function, managing pain, and even affecting plant growth through phytohormone delivery [

136]. Another critical topic is the delivery of drugs by microchip devices.Microelectromechanical system-based devices can store drugs in their most stable form and release multiple medications at precise times by selectively opening various reservoirs as needed for each drug dosage [

137]. Worth mentioning are also auto-injectors commonly mistaken for “pens” used for diabetes treatment. They automatically insert prefilled syringes, which is incredibly convenient for patients with the daily requirements for drug delivery [

138]. Electronic capsules with pH and temperature sensors are the last form of delivering drugs to the organism.

8.2. EDD Application in Diabetes and Epilepsy Treatment

It is safe to assume that progress in electronic drug delivery systems, which led to better adherence to therapies, was inevitable, and these days, it is noticeable. For example, futuristic insulin pens for the level of glucose in blood measurements that could transfer data via Bluetooth, like Contour Next One or OneTouch Veiro Flex, are already being replaced by noninvasive Dexcom systems with real-time glucose readings [

139]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (USA FDA) approved the Dexcom G6 system in March 2018 due to its precise measurements. It worked so well that in February 2023, the company released a new G7 generation with even more ease of use and exceptional accuracy. EDD development in past years has also affected the treatment of epilepsy by reducing the use of main therapeutic approaches to this disease, which had low efficacy and potential side effects. Instead, research was started by the Key Laboratory of Neuropharmacology and Translational Medicine of Zhejiang Province on the delivery of antiepileptic drugs (AED) with nanoengineered drug delivery systems using hybrid nanoparticles [

140]. Its main goal is to release drugs on demand to suppress epileptic discharges and properly penetrate the blood-brain barrier, which would prevent side effects of treatment. It is a massive breakthrough for patients during status epilepticus treatment, which requires regular administration of medications to control their repetitive seizures. For them, the inability to control status epilepticus may be associated with severe neurological sequelae and a short-term mortality of 15 to 20% [

140].

8.3. Digitalized Health with Personalized Drug Delivery Systems

With various apps, smartwatches, or other healthcare Internet of Things devices, delivering proper doses of drugs at appropriate times of the day is becoming as efficient as possible. Some private clinics have already launched their apps to make appointments, chat with doctors, store medical referrals for examinations, and, most notably for us in this article, they store drug prescriptions with their exact instructions. An example might be Polish LUX Med, the leader in private healthcare, which has more than 1 million downloads of its app in the Google Play Store. Managing chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and brain disorders presents challenges. Treatment often involves multiple doses based on severity, lifestyle, other medications, and age-specific needs for children and the elderly [

141]. Due to flexible on-demand doses, personalized and digitalized drug delivery systems allow for optimal health outcomes. Even if most medical professionals would never recommend “googling” symptoms and instead visit a clinic, most people have easier access to the internet than medical healthcare, and some people even have no access to medical healthcare. According to a 2019 report, there are over 1 billion health-related searches every day [

142]. Of course, people need to filter information to avoid misinformation, but overall, people are more informed than ever thanks to digitalization.

8.4. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) Algorithms in Electronic Drug Delivery:

In recent years, integrating AI and ML technologies with electronic drug delivery systems has reshaped personalized medicine. The terms mentioned above were extensively detailed in the "Artificial Intelligence (AI)" section of this revision paper. In this paragraph, I would like to highlight their specific applications in electronic drug delivery systems. By drawing from extensive patient data, including physiological parameters, medical histories, and real-time feedback from wearable devices, AI algorithms are now proficient at tailoring drug dosages and schedules to meet each individual's needs. These advanced systems ensure precise medication delivery and adapt treatment plans in real-time based on patient health changes or medication effectiveness. Additionally, AI-driven EDD platforms offer valuable insights into patient adherence and treatment outcomes, empowering healthcare providers to optimize care strategies and improve patient well-being.

9. Nano-BioElectronics

In the electronic drug delivery systems section, nano-bioelectronics was already mentioned as a futuristic way of treating epilepsy. This is only one of the various applications of this quickly expanding and developing field. For clarity and simplicity of the topic, we can define bioelectronics as a combination of biological system signals converted into electronic impulses, which a program can interpret. Those signals are sent, for example, by neurons and cardiomyocytes as ionic currents. The “nano” prefix refers to the microscopic scale of materials used during measurements (and plenty of other operations), such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, nanowires, and nanosheets. Structures described in this article are characterized by various dimensions. Zero-dimensional structures have no dimensions, resembling points without width, length, or height. One-dimensional structures primarily extend along a single dimension, appearing as lines or wires. Two-dimensional structures, on the other hand, primarily expand across two dimensions.

9.1. Nanowires and Nanoparticles – Description and Application

Nanowires are one-dimensional structures with diameters from 3 to 500nm, and they are particularly interesting as electronics based on them allow cell electrophysiology to be monitored [

143]. It is crucial in understanding neurons and cardiomyocyte activity. Generally, nanowires can be created using various techniques and divided into bottom-up and top-down. The top-down approach focuses on the accurate control of nanowires through a series of fabrication processes developed in the semiconductor industry, including lithographic patterning, reactive ion etching, and ion implantation. The bottom-up approach to nanowires is not as limited as the top-down approach. Thanks to its simultaneous control of geometric shapes and atomic composition, it can lead to new device ideas [

144]. On the other hand, nanoparticles are zero-dimensional spherical polymeric particles composed of natural or artificial polymers with a similar size to nanowires [

145]. They were previously mentioned as the “material” used in epilepsy treatment. In this case, their application has been reduced to acting as a very delicate sensor. Phenytoin drug molecules were loaded into polymer nanoparticles during polymerization through noncovalent interactions with polypyrrole and polydopamine. After linking those two polymers, hybrid nanoparticles have become very sensitive to electrical impulses, rapidly releasing antiepileptic drugs in response to epileptic discharges [

140].

9.2. Silicon Nanowire Field Effect Transistors in Biotechnology

Semiconductors are, so far, one of the most essential products in electronics. One of the most commonly known ways of controlling the current flow in semiconductors is using a field effect transistor (FET). The reason behind this is that with a tiny size, it can control the current flow by applying voltage on the gate, which alters the conductivity between the drain and the source. For years, 16 nm and 10nm fin field effect transistors (FinFETs) were mass-produced and used in everyday electronics. However, FinFETs struggled to control complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology due to compatibility with the design principles of CMOS circuits. That was one of the reasons why, in some cases, there was a requirement to exchange them for silicon nanowire field effect transistors (SiNWFETs) [

146]. The gate-all-around (GAA) NW FET design aims for meticulous regulation of electron flow within its silicon core, mitigating leakage current at remarkably brief gate lengths yet ensuring ample drive current via stacked NWs. SiNWs have been commonly used as ion transducers in biosensors for medical applications since 2001, when they were reported by Lieber’s group [

147]. Their massive use in nucleic acid and protein detection could also be noticed, which is essential for diagnosing diseases, screening drugs, and studying proteomics. As research advances, SiNW-based biosensors have the potential to transform medical diagnostics and personalized healthcare, catalyzing additional innovation within the field.

9.3. Nanocarbon as a Futuristic Approach to Bioelectronics

Nanocarbon is a term used to refer to the connection between carbon and nanotubes. It has been a fascinating material for many scientists due to its superior mechanical, electrical, chemical, and thermal properties [

148]. Carbon nanotubes, with impressive properties like high thermal conductivity and surface area, find applications in electronics, electrodes, and drug delivery. However, to maintain their unique qualities at scale, it's crucial to organize Nanocarbon structures effectively, which could be achieved through aligned films, yarn, fibers, and three-dimensional microarchitectures [

149]. They find various applications in bioelectronics, such as recording and stimulating neuronal activity. These materials encourage the growth of neurons, conduct electricity, and shape into capacitive electrochemical electrodes with exceptionally high specific surface areas [

150]. With all the properties mentioned above, they are ideally suited for neuronal interfacing. This is possible due to the concept of multi-electrode arrays, a significant development in carbon nanotube technology. Devices based on them consist of an array of electrically conducting microelectrodes (typically 20–200 μm in diameter [

150]) connected to an external circuitry to allow recording or stimulation of neural electrical activity. The most crucial disadvantage of carbon nanotubes and the reason for their relatively slow development are nanotoxicity mechanisms, which could lead to serious health issues. There have been plenty of in vivo and in vitro studies of carbon nanotubes [

151], which are still discovering the potential dangers of this technology.

9.4. Comparison Between Different Nano-Biotechnologies

Every approach to bioengineering uses nanotechnology differently. Some are often used together in more significant projects to archive everything each technology offers. The comparison of their most significant differences is shown in

Table 6.

10. Robotic Surgery Systems

Robotic surgery is among the most advanced forms of Minimally Invasive Surgery. The integration of robotic technology into surgical practices began almost 40 years ago. In the late 1980s [

152], Imperial College in London developed a robotic system called PROBOT to assist with transurethral prostatectomies. This system employs a computer-generated 3D model of the prostate, enabling the surgeon to specify the areas for resection. PROBOT then calculates the excision paths and autonomously executes the procedure. Its key benefits include a compact design, high cutting precision, and the reduction of surgeon fatigue during operations. Various robotic surgery systems are available, such as the da Vinci Surgical System, which is used for prostatectomies and is increasingly employed for cardiac valve repairs as well as renal and gynecologic procedures. Robotic surgeries are not only on those parts of the human body, they can also be used for eye surgeries. Robotic eye surgery, especially for delicate procedures involving the anterior segment and vitreoretinal areas, uses advanced systems to boost precision, minimize tremors, and automate tasks [

153,

154]. This technology not only improves surgical outcomes but also makes remote operations possible.

The Da Vinci Surgical System and other surgical robots will be discussed in greater detail, highlighting their different applications. A standard robotic surgery system includes three main parts: the surgical cart, the vision cart, and the surgeon's console [

155]. Surgical manipulators are divided into master manipulators (located on the surgeon’s side) and slave manipulators (located on the patient’s side). At the control console, the surgeon views images from an endoscopic camera and uses master manipulators to guide surgical instruments and the endoscopic manipulator inside the patient's body, with the patient-side manipulators mirroring the surgeon's movements. In each case, the surgical cart and robotic arms are positioned on the same side of the surgical site. The operator, assistants, and nurses are also on this side, while the surgical cart and vision cart are on the opposite side, allowing the operator to see the same 2-dimensional monitor as the other staff members to enhance teamwork [

155]. A suitable, robust, and fast control algorithm is very important in the surgical systems [

156,

157].

10.1. Da Vinci Surgical System

With more than 10,000 [

158] peer-reviewed publications in several surgical specialties, the safety and association of Da Vinci Surgical Systems with favorable patient outcomes have been proven repeatedly. It is, without a doubt, the leader in the robotic surgical field. The remarkable success of this robotic platform can be attributed to its three-dimensional (3D) visualization, seven degrees of motion, motion scaling, and tremor filtration. These advanced features collectively enable highly precise performance of increasingly complex surgeries. However, the platform does have some drawbacks, including the absence of haptic feedback, a limited variety of instruments, and, most notably, its high cost. Those costs are the biggest downside of robotic surgeries. Studies show that considering maintenance, disposable instruments, the initial investment in a robotic system, and the length of stay in the hospital, robotic surgery systems are more expensive than standard surgeries, up to 1600

$ per procedure [

159]. In this article, those costs relate to the Da Vinci Surgical System and every other robotic surgery system. Despite the high initial costs, robotic surgery should not be viewed negatively. Costs are decreasing yearly while the precision and effectiveness of operations are continually improving. This is particularly visible in recent Da Vinci Single-Port Robotic Surgery advancements for gynecologic tumors. Single-port surgery, a minimally invasive technique using a single entry point, typically provides better cosmetic outcomes and improved patient satisfaction. Although it presents technical challenges such as limited instrument movement, collisions, and poor visualization, it has significantly reduced the time of various gynecological surgeries and minimized average blood loss and changes in hemoglobin levels [

160]. Da Vinci Surgical System has also proven to be very useful and an excellent improvement for hospitals in fields other than gynecology, like urology or cardiology.

10.2. Versius:

This robotic surgery system is a new futuristic approach with a modular design and dual-console capability, allowing two surgeons to operate in different anatomical fields simultaneously and independently [

158]. The Versius system's modular design allows for various port placements, providing adequate surgical access and reach and enhancing its usability in a range of minimally invasive surgeries [

161]. It is proven very effective in procedures like cholecystectomies, radical nephrectomies, and trans-anal total mesorectal excision. The system's flexibility and portability allow adequate surgical access to critical areas within the retroperitoneum and pelvis [

162]. Unlike the Da Vinci system, which has limitations such as the need for redocking and the inability to complete specific procedures synchronously, the Versius system allows for fully synchronous dual-field robotic surgeries.

10.3. Senhance:

Senhance is a relatively new robotic surgery system with outstanding results in gynecological and abdominal surgery with 3 mm instruments [

163]. Its independent arms, which can reposition and install instruments easily sterilized again, set it apart from other robotic surgery systems. Examining 223 patients undergoing colectomy and proctectomy with the Senhance robot [

164], the study assessed primary outcomes such as intraoperative efficacy, conversion rates, and estimated blood loss. Secondary outcomes were centered on postoperative morbidity and length of hospital stay. The research revealed a decline in operative times with increasing experience, suggesting a learning curve for the surgical team. These instruments work with 5-mm trocars and can be set up like in traditional laparoscopy, making the transition smooth and familiar for surgical teams. Despite its advantages, the Senhance system requires an initial learning curve and presents challenges such as limited space for the assistant surgeon and high costs [

165].

10.4. Comparison Between Various Robotic Surgery Systems:

As shown above, Da Vinci is undoubtedly the leader in robotic surgical systems, with plenty of benefits and few disadvantages. Versius and Senhence surgical systems have a promising future according to how new those systems are and how promising their current results are. A comparison between all of the discussed surgical systems is shown in

Table 7.

11. Smartphones Applications

Smartphones are the most commonly used mobile computers in our current civilization. Such an environment encourages the usage of smartphones in every aspect of today's world. With such a mobile device, access to the internet also allows one to improve knowledge, stay updated with news, and keep in touch with other people. The medical field benefits from this technology thanks to the internet and many mobile applications that help doctors, technicians, patients, nurses, and even everyday people. The usage of smartphone applications in medicine can be divided into three groups according to their purpose: education, diagnosis, and assistance. Each group can be divided further into the receiving group, which consists of lay users and professionals.

11.1. Smartphone Applications in Education

The first group is applications that help students and trainees learn. For example, many quiz apps that check knowledge in anatomy, pharmacology, etc. Another is “Medical Encyclopedia,” a comprehensive medical reference from the University of Maryland Medical Center. Apps such as “Pubmed” contain thousands of articles with citations and abstracts that keep up with the growing number of scientific publications [

166]. Despite their popularity, there is no unambiguous evidence of their effectiveness in improving student academic performance [

167]. The studies showed that the group accessing smartphone applications had increased scores, but the statistical significance was not reached [

167]. It shows that even though smartphone applications are popular, their usage might improve the overall knowledge of lay users and not necessarily professionals.

11.2. Smartphone Applications in Diagnosis

The second group of smartphone applications aids in diagnosing and treating diseases. “Medscape” is one such application that describes symptoms, their cause, and suggested treatment. Most of the applications from this category are directed to lay users. Their goal is to save people time and money, soothe anxiety, educate, and make people aware of what is happening to them and what they should do [

168]. It is important to seek that information from trusted sources and not to search your symptoms online and base your diagnosis solely on the information found there. The studies show that roughly 42% of Google symptoms give an incorrect diagnosis [

169].

11.3. Smartphone Applications in Assistance

The last group can be further divided into two categories: lay users and professionals. Assistance applications for lay users help in daily life. “Samsung Health,” for example, helps keep track of your sleeping schedule, number of steps taken that day, calories eaten, and water drunk. All this can help maintain a healthy lifestyle and be taken even further by connecting the app with a smartwatch that can track many more things like heartbeat, blood pressure, or stress levels. Wearable devices are a massive step towards digitalizing your physical health. On the other hand, many applications are meant to assist with your mental health. Unfortunately, this field is far more complex. Many mental disorders and traumas are very individual, and it is quite a challenge to create a universal application that would suit a large number of people. A few applications try to improve users' mental self-care, though their ratings are often very extreme [

170]. The field of mobile mental health still has a long way to go, but shortly, we might see more of them on the market [

170].

On the professional side, there is a concern about the common usage of smartphone applications [

171]. There is a discussion about ethics. Awareness about the risks should be widely spread as unsafe usage of those applications can lead to infractions of the code of health professional ethics. Studies conducted in Saudi Arabia published in [

172] show that only 42.3% of healthcare workers utilize smartphones in healthcare practice. Only 6.1% of all healthcare providers use mobile applications frequently, and 26.2% use them sometimes. These studies show that the most common reason for professionals to use these apps is to check drug information (69.8%), diagnose (56.4%), and access medical websites (42.5%).

11.4. Deep Learning

Some applications use Deep Learning for more complex problems. Thanks to its learning ability, it can be used to interpret photos. One of the possibilities is plant recognition. There are thousands of plants; some have medical properties, and some are poisonous. That’s why it is essential to know which is which. An application called “MedicPlant” uses deep learning to recognize seventy medicinal plants [

173]. It has an educational value and can also help people who hike and need help recognizing plants they discover. Professionals commonly use Deep learning structures to interpret and detect malaria parasites [

174] or skin cancer [

175] based on pictures alone. However, it is mainly used on a more complex computer than a smartphone and can achieve a 94.74% accuracy [

175].

11.5. A Review of Medical Smartphone Applications

As stated in previous paragraphs, many applications are meant strictly for professionals and medical personnel. That is why only some of the applications discussed earlier are available to everyone.

Table 8 provides a summary and short description of applications available to every user.

12. Virtual Reality (VR)

Researchers in the field of medicine have been using simulations for years. For decades, those simulations were nothing more than an experienced surgeon performing and explaining the procedure. It massively limited the number of viewers and depended on the older doctors' presence and skill [

176]. Furthermore, as the technical side of the surgeries developed, simulations became even more exclusive due to the higher costs, ethical concerns, and decreasing resident work hours [

176]. It has become a real problem as simulations were commonly used to teach students and prepare doctors before complicated procedures. Virtual reality is one step towards more realistic simulation, leading to better performance. Head Mounted Display (HMD) allows a multisensory environment where the user can fully immerse and interact with everything around him. It provides a unique opportunity to [

177] perceive 3D stereoscopic images. It connects the advantages of a digital photo and a 3D model. The first one allows us to magnify the picture and take a very close look at the image. The second one will familiarize you with the shape of a tissue and allow you to “feel” it. Various input devices such as joysticks, wands, and gloves allow one to interact with such images and freely move and look around the Virtual environment. Such training does not require supervision as the simulation can verify the procedure. Attendance of a patient is also unnecessary because of an entirely virtual environment. That allows the training of many doctors simultaneously without resetting the procedure after every attempt and for every trainee.

12.1. VR in Surgery Training

Different sets of devices are used depending on the purpose of using virtual reality systems. For example, in surgery training, the main focus is for the trainees to get familiar with the structures of different tissues [

177]. Many high-resolution images of skin, bones, muscles, veins, etc., are used for that [

178]. Furthermore, such training is aided by entire robotic systems that help simulate the instruments with which the surgeon will operate in the future. The trainee uses the same robotic tools during the actual procedures, but everything the trainee sees is simulated. Those simulations can also help explain the procedure and the risks involved to the patient. The doctor can easily show a recording of a procedure simulation so that patients know what to expect.

12.2. VR in Robotic-Assisted Surgeries

Another common usage of VR in medicine is joining it with robotic systems in Robotic-Assisted Surgery (RAS) [

179]. For years, operating those robots was done by watching through stereoscopic visualization. It is a system with two cameras and two lenses that allow it to be perceived multi-dimensionally. Researchers wanted to test whether the HMD would better visualize 3D structures with which robotic arms interact. The tests proved that using VR as a visualization tool is more ergonomic for doctors. The testers gave a 3.9 satisfaction rating on a 5-point scale. Considering that there was no noticeable difference in the performance, VR systems will likely be a common addition to robotic-assisted surgeries. The most used robot in operation rooms is a DaVinci robot. It is a system of arms with different instruments and cameras which allow us to conduct various operations in many medical fields such as: urology, gynecology, colorectal surgery, laryngology, cardiac surgery. While it uses cameras and screens rather than a VR system there are studies that show that VR training can improve performance on DaVinci robot. It can also result in an early plateau in the learning curve for robotic practice [

180].

12.3. Remote Surgeries

Time is one of the most critical factors for successful surgeries. Because of that, it is sometimes impossible for the surgeon to arrive at a hospital that can be thousands of miles away. Thanks to the current state of VR [

181], it is no longer necessary. In 2001, there was a successful cholecystectomy (surgical removal of the gallbladder) that was performed over a distance of 6230 km [

181,

182]. Despite being a huge success in remote surgeries, it is worth noting that the connection was explicitly set for this operation. The secure communication is a key challenge in remote surgery [

183].

Another use of remote surgeries is more common but less spectacular. Thanks to robotic-assisted surgeries, it is possible to perform an operation with minimal interference to the human body. The surgeons can insert tools and cameras through a tiny cut. The whole operation is done inside the body of a patient, and later, there are no visible scars.

One more obstacle must be overcome for remote surgeries to be more common. During operation, precision is crucial. That is why the feedback of the VR must be as accurate as possible so that the surgeon can operate at his full potential. Surgeons must have full control over the strength of the robot’s grip and clearly understand the boundaries of its working space.

12.4. Advantages and Disadvantages of VR in Medicine

Studies show that VR can improve doctors’ accuracy and learning [

184]. The list of advantages mainly contains a psychological aspect of learning. Trainees say that VR training has a positive mental effect, improves self-confidence, and allows for more frequent and accurate training. The disadvantages, on the other hand, are mostly connected with VR being an expensive solution. From a technological point of view, there are a lot of different aspects, such as suitable hardware, well-written software, and stable and fast internet connection, that need to work for VR to be efficient [

185].

Table 9 compares and lists the most important advantages and disadvantages.

13. Medical Sensors

Medical sensors are one of the fundamental elements of modern medical devices. They provide data that can be interpreted by the device and given to the doctor so they can diagnose a patient. They became popular in the mid-seventies and constantly evolved into what we use today [

186]. The first procedure that used sensors was plethysmography (a procedure that measures changes in volume in different parts of the human body [

186]). This procedure is still one of the most frequently used methods to measure peripheral blood flow. Medical sensors can be divided into two main groups: professional equipment and wearable devices.

13.1. Wearable Devices

When considered in the context of the sensors, wearable devices are not the most reliable sources of information about our bodies. A smartwatch –the most common wearable device with sensors [

187]- is often used to track pulse, blood pressure, or stress levels. But because of its focus on wearing comfort and convenience, they are limited to a measurement in one place, usually a wrist, and they are not correctly adjacent to the body (again, because of the wearer's comfort). That is why making medical decisions based on measurements from wearable devices is unreliable. That being said, wearable devices are a great way to warn about some abnormalities in measured data. This could be a sign to get checked by a professional. Studies show that wearable devices and their ability to measure bio-signals are straightforward to understand for most users, and their implementation is very beneficial [

188].

13.2. Professional Equipment

Professional equipment is devices used in a controlled environment such as hospitals. The most common sensor procedures are electrocardiography (ECG), ultrasonography (USG), electroencephalography (EEG), blood pressure, and pulse oximetry. On top of that, sensors are commonly used in imaging procedures such as RTG or MRI.

ECG uses electrodes attached to the human body and interprets electrical currents detected by the electrodes [

189]. There are three different types of ECG measurement: 3-lead, 5-lead, and 12-lead. The larger the number of leads, the more detailed the measurement. The downside of using the 12-lead method is the time needed to place all the electrodes. 3-lead measurement is more efficient and can be used to find some pathologies in cardiac work. If the pathologies are detected, the patient can be directed to further imaging using a 12-lead method.

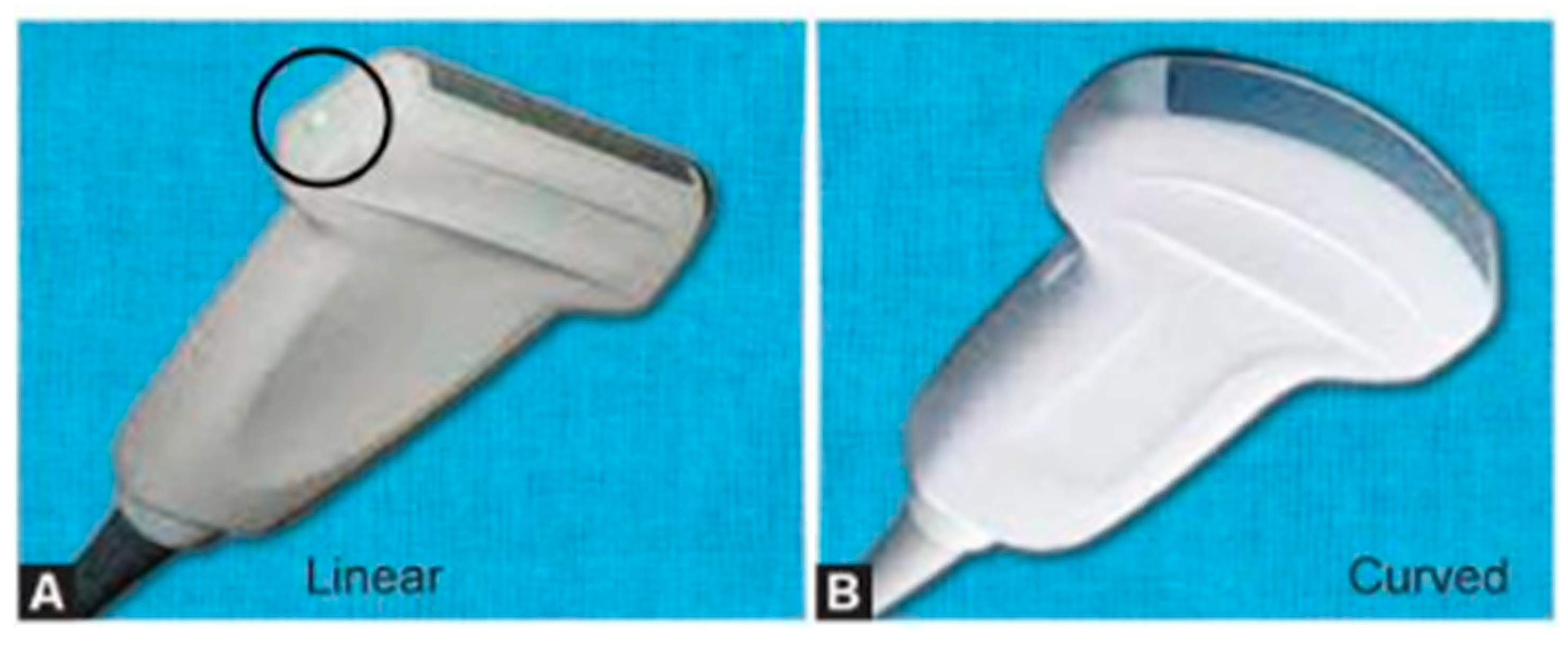

USG is a procedure that uses the fact that the speed of sound depends on the material's acoustical impedance. Different tissues have different acoustical impedances. Thanks to that, it is possible to differentiate between different tissues during the procedure. A large emitting head (

Figure 3) is used to acquire the image. Most often in medical usage, the head also acts as a receiving sensor, which obtains an echo of sent ultrasounds. The sensor is an ultrasonic transducer that converts the electric signal to ultrasonic waves and vice-versa [

190].

EEG, similar to ECG, measures electrical currents detected by electrodes. EEG, however, is used to detect the work of a human brain. Because of that, signal quality requirements for EEG are much higher than ECG and, for many years, were limited by noise and usability usage. Standard measurements of EEG are done on the scalp using a conductive gel to ensure a good electrical connection. However, modern technology allows EEG to be more patient-friendly. There was research on building dry, through-hair, non-contact sensors [

192]. The test showed that these devices are as reliable as the previous ones.

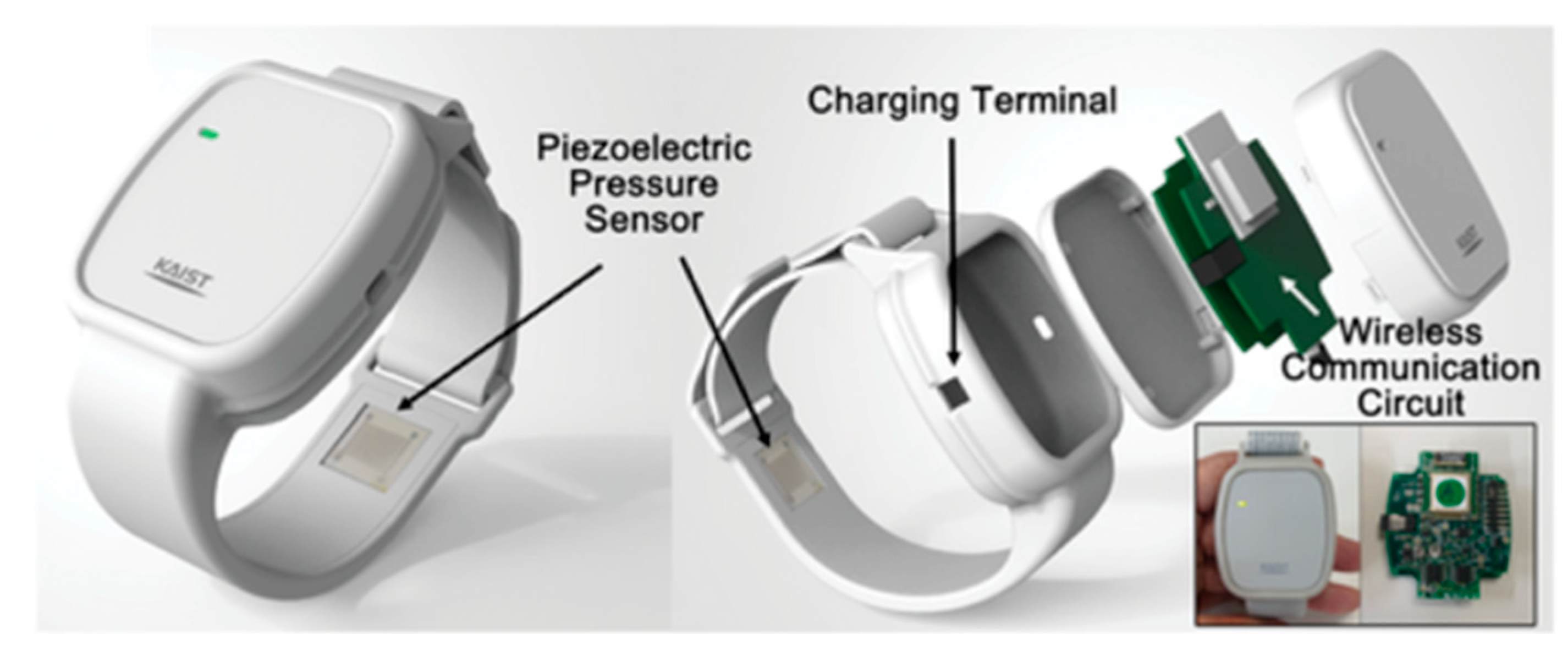

Blood pressure measurement can be performed using an invasive or non-invasive method. The invasive procedure uses a catheter tip in a transducer as a pressure sensor. The transducer uses a microelectromechanical system to convert pressure waves to electrical signals. Other invasive methods are based on nonvascular implantable miniaturized sensors compatible with body tissues. Most widely used non-invasive methods use sensors based on stroke volume methods [

193] (

Figure 4). The performance of this method is highly dependent on the design and fabrication of electrodes and the continuous contact with the skin.

Pulse oximetry is a simple procedure measuring hemoglobin saturation in blood. A light sensor is used to measure that. At given wavelengths, the molecular absorption of light is constant. We can calculate the hemoglobin saturation by measuring light absorption [

195]. Conventional pulse oximetry uses optoelectronic devices as sensors, but modern researchers test using organic materials to measure hemoglobin saturation in blood [

196]. Those tests use organic light-emitting diodes (OLED) and organic photodiodes (OPD). This organic sensor measures blood's pulse rate and oxidation with 1% and 2% errors, respectively [

196].

RTG uses X-ray radiation to make non-invasive images of tissues inside the human body. Different tissues absorb different amounts of X-ray radiation. That is why a set of sensors behind a patient can detect the quantity left of radiation and make an X-ray image. New research in the context of RTG is an amorphous Silicon (a-Si) x-ray imaging detector designed for medical imaging applications [

197].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive procedure that maps the internal structure of human tissues. It uses nonionizing electromagnetic radiation. The patient is put inside a giant magnet, which induces a strong magnetic field. This field causes the nuclei of atoms in the body (mostly Hydrogen) to align with the magnetic field. Then, thanks to built-in coils (

Figure 5) the computer detects and uses the energy released from the body to construct the MR image [

198]. Current research is focused on testing single-sided, handheld MRI sensors [

199]. The biggest challenge to overcome in those devices is the low signal-to-noise ratio.

13.3. Review of Different Procedures and Signals Detected

Table 10 shows a review of different procedures and lists the sensors used.

14. Blockchain Technologies

Blockchain technology is a technology of distributed ledgers of digital transactions [

201]. Thanks to the fact that it is decentralised, it allows for a thrustless exchange of data. It means that no authority manages the transaction. All exchange participants create a network where every party holds and maintains data. Every block in the blockchain includes a cryptographic signature about other records in the chain, along with the exact information about when the block was created. New records can only be added with the consent of other network maintainers. Adding it will automatically change its signature, so there is no chance that any undetectable break will be created in the chain. Because of this technology’s immutability and transparent nature, each blockchain stakeholder can be sure that the data that they possess is an unmodified copy of the blockchain’s data stream [

202].

This technology was created as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. An anonymous author, Satoshi Nakamoto, described it for the first time in 2008. In their article, they acknowledge the great need to adopt an electronic payment system so it would be cheaper, more trustworthy and resistant to fraud. They present blockchain technology as an answer to all these needs, describing it as “an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party” [

203].

14.1. Blockchain Technology in the Healthcare System