1. Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer therapy by harnessing the body’s own immune system to combat malignant cells. These agents, targeting key immune checkpoints such as programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), have demonstrated significant clinical efficacy across various malignancies. However, their therapeutic potential is tempered by a spectrum of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including endocrinological disorders[

1,

2,

3].

Endocrine dysfunction, a less recognized but increasingly prevalent irAE, can manifest as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypophysitis, adrenal insufficiency (AI), and diabetes mellitus (DM). These conditions, often presenting with subtle and nonspecific symptoms, can significantly impact patients’ quality of life and overall prognosis. Prompt recognition and appropriate management are crucial to mitigate their adverse consequences[

3,

4,

5].

To address this emerging clinical challenge, our study retrospectively analysed a cohort of 516 solid organ cancer patients treated with ICIs between 2016 and 2022. We aimed to investigate the incidence, timing, treatment modalities, and impact of ICI-related endocrinological side effects on cancer therapy and patient survival. By elucidating the clinical characteristics and management strategies for these disorders, we hope to improve patient outcomes and optimize the therapeutic potential of ICIs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This multicentre retrospective study analysed 139 patients with solid organ cancers who developed immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-related endocrinological side effects between 2016 and 2022. Patient data including demographics, cancer characteristics, ICI treatment details, and endocrine side effect profiles were collected. The study defined and characterized ICI-associated hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypophysitis, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Diagnostic criteria, treatment strategies, and response assessments for these conditions were outlined. The impact of these endocrine side effects on overall survival was also evaluated.

Before the research, approval was received from the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University Faculty of Medicine (Document number: E-10840098-772.02-6952).

2.2. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

This study analyzed 139 patients with various solid organ cancers who received ICI therapy. The majority of patients were male (68.3%) with a median age of 62 years. Approximately 42.4% of patients were under 60 years old, and a significant portion (59%) had no comorbidities. Common comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Regarding cancer types, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was the most prevalent (47.5%), followed by renal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, and small cell lung cancer. A significant number of patients (80.6%) were diagnosed at stage 4, indicating advanced disease.

In terms of treatment lines, 24.5% of patients received ICI as a first-line therapy, while the majority received it as second-line or later-line treatment. Pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab were the most commonly used ICI agents (

Table 1).

2.3. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24.0. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were employed to assess the relationship between ICI treatment response and clinicopathological factors, as well as treatment preferences. Kaplan-Meier analysis with the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves and analyse overall survival, defined as the time from diagnosis to death or loss to follow-up. Univariate analysis was initially performed to identify potential prognostic factors, followed by multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis to determine independent variables affecting survival. Logistic regression analysis was utilized to identify independent predictors of response to ICI treatment. The 95% confidence interval was used to quantify the relationship between survival time and independent factors. All p-values were two-sided, with statistical significance set at p<0,05.

3. Results

3.1. Incidence and Spectrum of Endocrine irAEs

This study analysed 139 patients with solid organ cancer who received ICI therapy (alone or in combination). The most common endocrine adverse event was hypothyroidism (65,5%), while the least common was diabetes mellitus (0,7%). No patient developed hypoparathyroidism. Other adverse events included hyperthyroidism in 2,3%, autoimmune disease in 13.7%, and pituitaryitis in 8,6% of patients. Most adverse events were mild (grade 1 or 2) according to the ASCO grading system. Of the patients who developed hypothyroidism, 35,2% experienced grade 1, 61,5% grade 2, 2,2% grade 3, and 1,1% grade 4 adverse events. Among patients who developed hyperthyroidism, 51.6% experienced grade 1, and 48,6% grade 2 adverse events, with no grade 3 or 4 events reported. For patients with pituitaryitis, 25% experienced grade 1, 58,3% grade 2, and 16,7% grade 3 adverse events, with no grade 4 events. Of patients who developed autoimmune disease, 31,5% experienced grade 1, 42,1% grade 2, 15,7% grade 3, and 10,7% grade 4 adverse events. A single patient developed grade 4 diabetes mellitus (

Table 2).

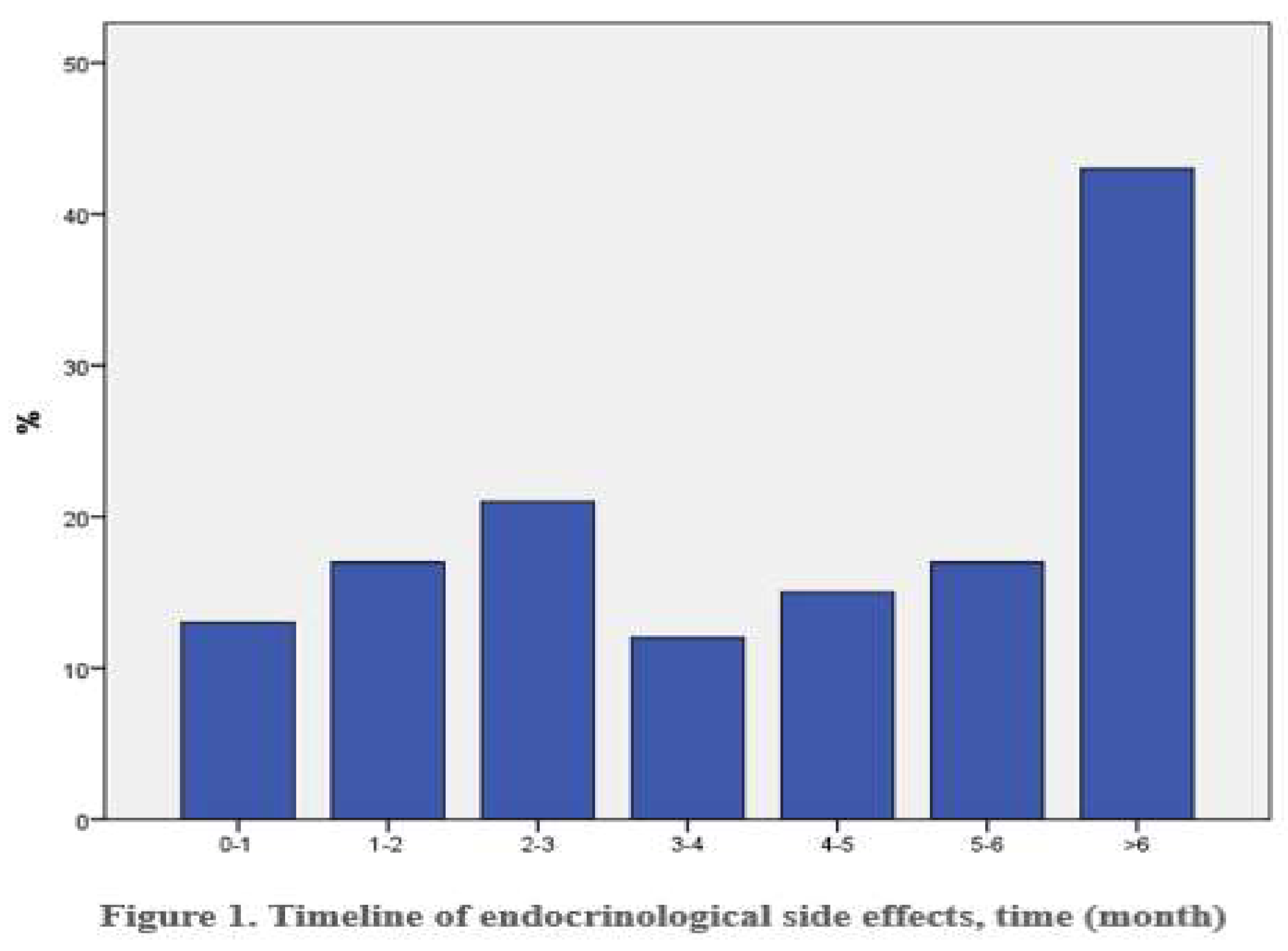

3.2. Timing of irAE Onset

Immunotherapy induced side effects emerged with a median latency of 4,5 months (range: 0,4-20,5 months). Notably, 29,5% of patients developed adverse events after six months of treatment (

Figure 1).

3.3. Management of Endocrine irAEs

Among the 91 patients who developed hypothyroidism, 65,5% were managed conservatively, while 39,1% required hormone replacement therapy. In two cases, immunotherapy was temporarily paused, and in another two, it was discontinued. A severe case of myxoedema coma occurred in a 69-year-old patient, necessitating intensive treatment. One patient with pre-existing hypothyroidism experienced worsening symptoms, and two patients with subclinical hypothyroidism progressed to overt disease. Of the 31 patients with hyperthyroidism, 4,3% received antithyroid medication, while the majority were monitored. Most subsequently developed hypothyroidism. Immunotherapy was temporarily paused in 5 cases, but no treatment discontinuation was required.

A total of 91 patients developed hypothyroidism, with thyroid autoantibodies detected in 31,9%. Among these, 34,4% were anti-TPO positive, 13,7% were anti-Tg positive, 17,2% were positive for both, and 27,5% were negative for both. Thyroiditis was observed in 86,2% of patients with available thyroid ultrasound data. Thirty-one patients developed hyperthyroidism. Thyroid autoantibodies were detected in 58% of these patients, primarily anti-TPO. Thyroiditis was present in 75% of patients with available ultrasound data.

Hypophysitis occurred in 12 patients, all of whom required hormone replacement therapy. One patient received high-dose steroids. Immunotherapy was temporarily paused in seven patients. Diabetes mellitus developed in one patient, who was treated with insulin therapy and had a temporary pause in immunotherapy. Adrenal insufficiency occurred in 19 patients, all of whom received hormone replacement therapy. Nine patients received high-dose corticosteroids. Immunotherapy was paused in two patients and discontinued in three.

3.4. Impact of Endocrine irAEs on Clinical Outcomes

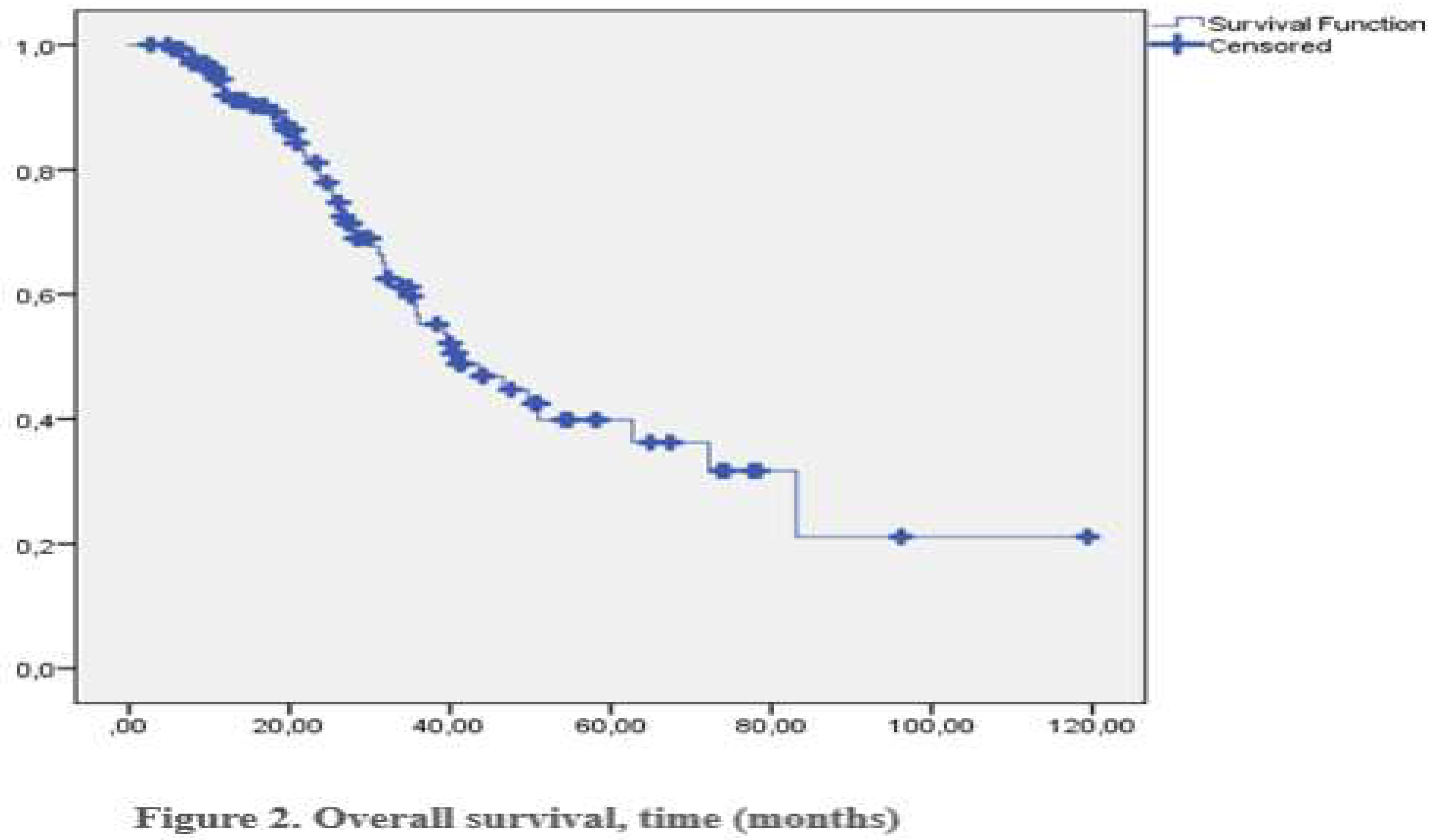

Of the 122 patients, 25 achieved a complete response (CR), 49 a partial response (PR), 29 stable disease (SD), and 28 progressive diseases (PD). The objective response rate (ORR) was 53,3%, and the clinical benefit rate (CBR) was 74,2%. Male gender and treatment with pembrolizumab were independent predictors of response to immunotherapy. Endocrine side effects did not significantly impact response rates. The median overall survival was 40,9 months (

Figure 2). No deaths were attributed to endocrine side effects.

4. Discussion

Endocrine dysfunction is a significant toxicity associated with ICI therapy, impacting up to 40% of treated patients. The most affected organs are the thyroid gland, pituitary gland, adrenal glands, and pancreas. Thyroid dysfunction, often manifesting as hypothyroidism preceded by transient hyperthyroidism, is the most prevalent endocrine side effect. Other potential complications include panhypopituitarism, primary adrenal insufficiency, and insulin-deficient diabetes. These endocrine disorders are distinct from those caused by conventional chemotherapy or newer targeted therapies[

6].

ICI-induced endocrinopathies are a significant side effect of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. These endocrine disorders, such as hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus, can vary widely in severity and timing of onset. While mild cases of hypothyroidism are common, severe cases of diabetes mellitus can be life-threatening. Early detection and timely intervention with hormone replacement therapy are crucial for managing these conditions and improving patients’ quality of life. Given the subtle and non-specific nature of symptoms, oncologists must maintain a high index of suspicion and implement regular screening protocols to identify and address these endocrine disorders promptly[

7].

Thyroid dysfunction is a common side effect of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, affecting approximately 10% of patients on anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy and up to 20% of those on combination therapy with CTLA-4 inhibitors. Many cases manifest as hypothyroidism, often preceded by a destructive thyroiditis. While pre-existing anti-thyroid antibodies increase the risk, the exact mechanisms underlying ICI-induced thyroid dysfunction are not fully understood. Hypothyroidism typically presents with subtle symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, and cognitive changes. Thyroiditis can lead to transient hyperthyroidism, but severe cases are rare. Diagnosis relies on laboratory tests, primarily TSH and FT4 levels. In cases of secondary hypothyroidism, further evaluation of pituitary function is necessary. Regular monitoring of thyroid function is crucial. Hypothyroidism is treated with levothyroxine replacement therapy. For thyrotoxicosis, supportive care and beta-blockers may be sufficient. In rare cases of severe thyrotoxicosis, additional treatments like anti-thyroid medications or radioactive iodine may be considered [7-14].

Hypophysitis, an inflammation of the pituitary gland, is a rare complication of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, primarily associated with anti-CTLA-4 based treatments. This condition can lead to hypopituitarism, a deficiency in one or more pituitary hormones. The exact mechanism is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve a type II hypersensitivity reaction. Autoantibodies targeting specific pituitary cells may play a role in this process. Patients often present with non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, and headaches. More severe symptoms may include visual disturbances, hypotension, and adrenal crisis. Laboratory findings may reveal low levels of cortisol, thyroid hormone, and sex hormones. Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. Brain MRI can reveal pituitary enlargement or an empty sella. Treatment focuses on hormone replacement therapy to address deficiencies. Glucocorticoid replacement is essential for adrenal insufficiency, while thyroid hormone and sex hormone replacement may also be required. In severe cases, high-dose corticosteroids may be used to reduce inflammation. It’s important to note that while ICI therapy can be continued in many cases, careful monitoring and dose adjustments may be necessary[15-17].

Primary adrenal insufficiency is a relatively uncommon but potentially life-threatening complication associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy. This condition arises when the adrenal glands, responsible for producing crucial hormones like cortisol and aldosterone, are compromised. Patients with primary adrenal insufficiency may experience symptoms such as fatigue, malaise, nausea, hypotension, and in severe cases, adrenal crisis. These symptoms stem from the combined deficiency of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. Laboratory tests typically reveal low morning cortisol levels and elevated ACTH levels. Additionally, metabolic acidosis and hyperkalaemia may be present if mineralocorticoid-producing cells are affected. Given the serious nature of primary adrenal insufficiency, immediate treatment is essential. This involves initiating glucocorticoid replacement therapy, like the approach for secondary adrenal insufficiency. In some cases, mineralocorticoid supplementation may also be required. While ICI therapy may be continued following acute stabilization, close monitoring and appropriate management of adrenal insufficiency are crucial[

18].

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-associated diabetes mellitus (ICI-DM) is a serious side effect affecting approximately 1% of patients treated with ICIs. It is characterized by severe and persistent insulin deficiency, often leading to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). The underlying mechanism involves immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic beta cells, likely triggered by increased PD-L1 expression on these cells. While sharing similarities with type 1 diabetes, ICI-DM exhibits distinct features, including a more rapid onset and a lower prevalence of islet autoantibodies. Genetic factors, particularly HLA haplotypes associated with type 1 diabetes, also play a role in susceptibility to ICI-DM. ICI-DM can develop at any time during or after ICI therapy, with a median onset of 7-17 weeks. Symptoms include polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, and abdominal pain. Diagnosis often relies on random blood glucose measurements and basic metabolic panels, as A1C levels may not be significantly elevated in acute cases. Regular glucose monitoring is essential for early detection of ICI-DM. Treatment primarily involves insulin therapy to manage blood glucose levels. Unlike other ICI-related endocrinopathies, high-dose steroids are not indicated for ICI-DM. While some cases of remission have been reported, most patients require lifelong insulin therapy[19-26].

While less common, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy has also been associated with the development of more rare endocrine disorders. These include primary hypoparathyroidism, diabetes insipidus, syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and Cushing’s disease. Due to the extremely low incidence of these conditions, detailed information is limited. Diagnosis and management of these rare endocrine complications should rely on clinical presentation and established treatment guidelines.

Our study further highlights the association between irAEs and improved clinical outcomes. Patients who developed endocrine irAEs had a higher objective response rate and clinical benefit rate compared to those without irAEs. This suggests that irAEs may serve as a biomarker for effective immunotherapy response.

However, it is important to note that the development of irAEs can lead to significant morbidity and may require dose reduction or treatment interruption. Therefore, a careful balance must be struck between maximizing therapeutic benefit and minimizing adverse effects.

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and relatively small sample size. Further prospective studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate our findings and to investigate the underlying mechanisms of ICI-induced endocrine disorders. Endocrine irAEs are common complications of ICI therapy. Early recognition, prompt diagnosis, and appropriate management are essential to minimize their impact on patient health and quality of life. Future research should focus on identifying predictive biomarkers for irAE development and developing strategies to mitigate their severity.

5. Conclusions

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer therapy, but their use is accompanied by a range of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including endocrine disorders. Our retrospective study highlights the significant prevalence of ICI-associated endocrine dysfunction, particularly hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypophysitis, and diabetes mellitus. We found that early detection and timely management of these endocrine disorders are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. Hormone replacement therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment, while in some cases, temporary or permanent discontinuation of ICI therapy may be necessary.

Furthermore, our study suggests a potential association between the development of irAEs and improved clinical outcomes. This intriguing finding warrants further investigation to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and to determine whether irAEs can serve as biomarkers for effective immunotherapy response. While ICI therapy has significantly advanced cancer treatment, it is imperative to carefully monitor patients for the development of endocrine irAEs. A multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, endocrinologists, and other specialists is essential to ensure optimal management of these complications. Future research should focus on identifying predictive biomarkers for irAE development, developing strategies to mitigate their severity, and improving our understanding of the underlying immunological mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and H.M.; methodology, M.D,H.M.; software, M.D, HM.; validation, H.M.,A.B. and O.F.O.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, M.D, H.M.; resources, M.D, H.M.; data curation, M.D, H.M, E.O, B.B.K, K.H, E.K, S.K, M.B.A, I.C and F.S, .; writing—original draft preparation, M.D, H.M.; writing—review and editing, M.D, H.M.; visualization, M.D, H.M.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B, H.M.; funding acquisition:no funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Istanbul Medipol University Faculty of Medicine (Document number: E-10840098-772.02-6952).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Finn, O.J. , Human tumor antigens, immunosurveillance, and cancer vaccines. Immunologic research, 2006. 36: p. 73-82.

- Weintraub, K. , Drug development: Releasing the brakes. Nature, 2013. 504(7480): p. S6-S8.

- Champiat, S.; Lambotte, O.; Barreau, E.; Belkhir, R.; Berdelou, A.; Carbonnel, F.; Cauquil, C.; Chanson, P.; Collins, M.; Durrbach, A. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, F.; Sofiya, L.; Sykiotis, G.P.; Lamine, F.; Maillard, M.; Fraga, M.; Shabafrouz, K.; Ribi, C.; Cairoli, A.; Guex-Crosier, Y. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filette, J.; Andreescu, C.E.; Cools, F.; Bravenboer, B.; Velkeniers, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endocrine-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Horm. Metab. Res. 2019, 51, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, P.C.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Waguespack, S.G.; Hu, M.I.; Thosani, S.; Lavis, V.R.; Busaidy, N.L.; Subudhi, S.K.; Diab, A.; Dadu, R. Immune-related thyroiditis with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thyroid 2018, 28, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, E.A.; van der Meer, J.W.; Hurkmans, D.P.; Schreurs, M.W.; Oomen-de Hoop, E.; van der Veldt, A.A.; Bins, S.; Joosse, A.; Koolen, S.L.; Debets, R. Overt thyroid dysfunction and anti-thyroid antibodies predict response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in cancer patients. Thyroid 2020, 30, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.S.; Long, G.V.; Guminski, A.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Menzies, A.M.; Tsang, V.H. The spectrum, incidence, kinetics and management of endocrinopathies with immune checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic melanoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 178, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, C.A.; Menzies, A.M.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Tsang, V.H. Thyroid toxicity following immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in advanced cancer. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1458–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso-Sousa, R.; Barry, W.T.; Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Hodi, F.S.; Min, L.; Krop, I.E.; Tolaney, S.M. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakakida, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Uchino, J.; Chihara, Y.; Komori, S.; Asai, J.; Narukawa, T.; Arai, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Tsunezuka, H. Clinical features of immune-related thyroid dysfunction and its association with outcomes in patients with advanced malignancies treated by PD-1 blockade. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 2140–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwal, A.; Kottschade, L.; Ryder, M. PD-L1 inhibitor-induced thyroiditis is associated with better overall survival in cancer patients. Thyroid 2020, 30, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Lacchetti, C.; Schneider, B.J.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Gardner, J.M.; Ginex, P. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1714–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzanov, I.; Diab, A.; Abdallah, K.; Bingham, C.r.; Brogdon, C.; Dadu, R.; Hamad, L.; Kim, S.; Lacouture, M.; LeBoeuf, N. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faje, A.T.; Lawrence, D.; Flaherty, K.; Freedman, C.; Fadden, R.; Rubin, K.; Cohen, J.; Sullivan, R.J. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with melanoma. Cancer 2018, 124, 3706–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grouthier, V.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Moey, M.; Johnson, D.B.; Moslehi, J.J.; Salem, J.E.; Bachelot, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated primary adrenal insufficiency: WHO VigiBase report analysis. Oncol. 2020, 25, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quandt, Z.; Young, A.; Anderson, M. Immune checkpoint inhibitor diabetes mellitus: a novel form of autoimmune diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 200, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.J.; Salem, J.-E.; Johnson, D.B.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Stamatouli, A.; Thomas, J.W.; Herold, K.C.; Moslehi, J.; Powers, A.C. Increased reporting of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, e150–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osum, K.C.; Burrack, A.L.; Martinov, T.; Sahli, N.L.; Mitchell, J.S.; Tucker, C.G.; Pauken, K.E.; Papas, K.; Appakalai, B.; Spanier, J.A. Interferon-gamma drives programmed death-ligand 1 expression on islet β cells to limit T cell function during autoimmune diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, V.H.; McGrath, R.T.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Scolyer, R.A.; Jakrot, V.; Guminski, A.D.; Long, G.V.; Menzies, A.M. Checkpoint inhibitor–associated autoimmune diabetes is distinct from type 1 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 5499–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatouli, A.M.; Quandt, Z.; Perdigoto, A.L.; Clark, P.L.; Kluger, H.; Weiss, S.A.; Gettinger, S.; Sznol, M.; Young, A.; Rushakoff, R. Collateral damage: insulin-dependent diabetes induced with checkpoint inhibitors. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, J.R.; Perry, D.J.; Salama, A.K.; Mathews, C.E.; Moss, L.G.; Hanks, B.A. Genetic risk analysis of a patient with fulminant autoimmune type 1 diabetes mellitus secondary to combination ipilimumab and nivolumab immunotherapy. J. ImmunoTherapy Cancer 2016, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, E.; Sahasrabudhe, D.; Sievert, L. A case report of insulin-dependent diabetes as immune-related toxicity of pembrolizumab: presentation, management and outcome. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, B.; Donath, M.Y.; Läubli, H. Successful treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced diabetes with infliximab. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, e153–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).