Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

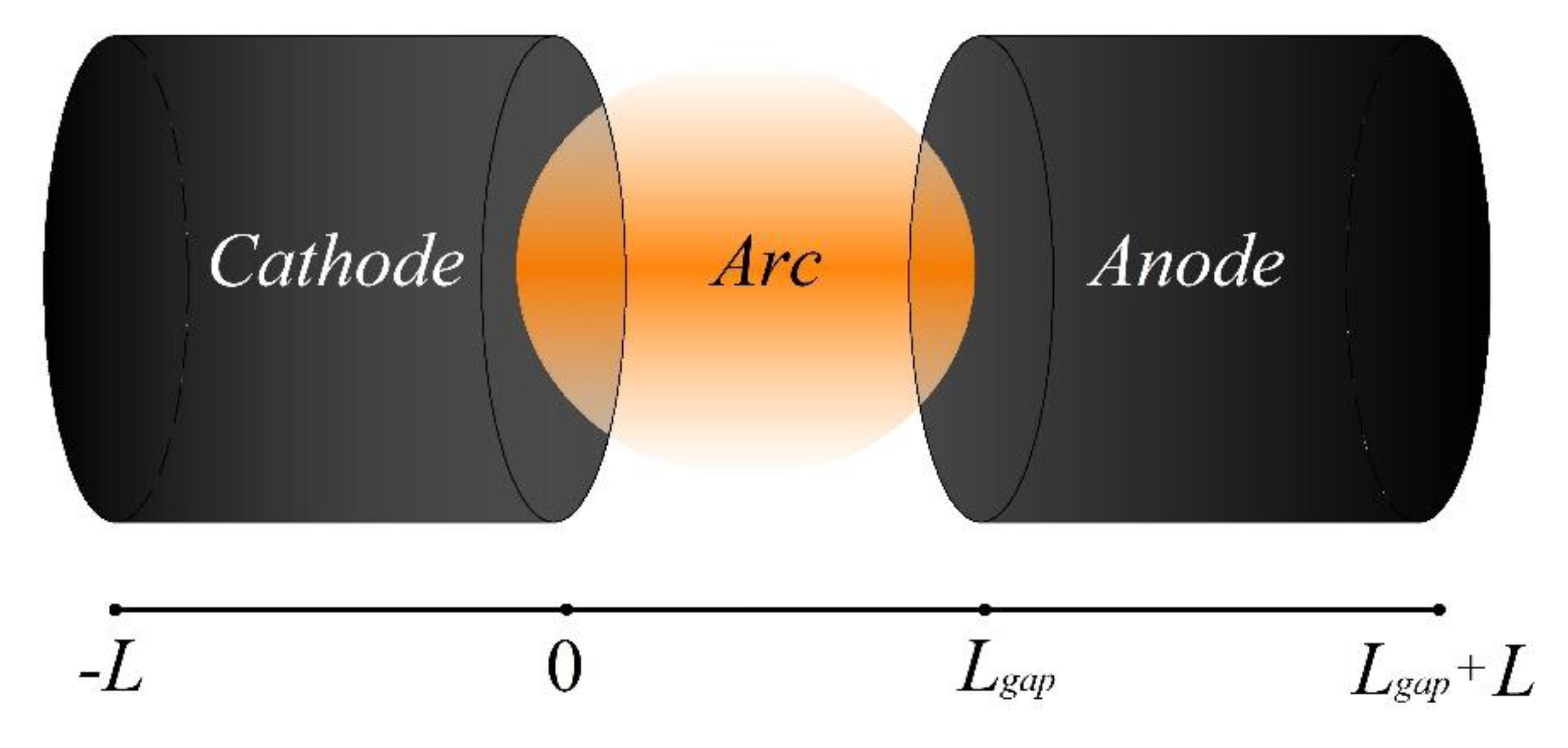

2. Model Description

2.1. Model Equations and Boundary Conditions

2.2. Elementary Processes in Argon Plasma

2.3. Kinetics of Elementary Processes Involving Methane CH4

2.3. Kinetics of Elementary Processes Involving Copper Cu

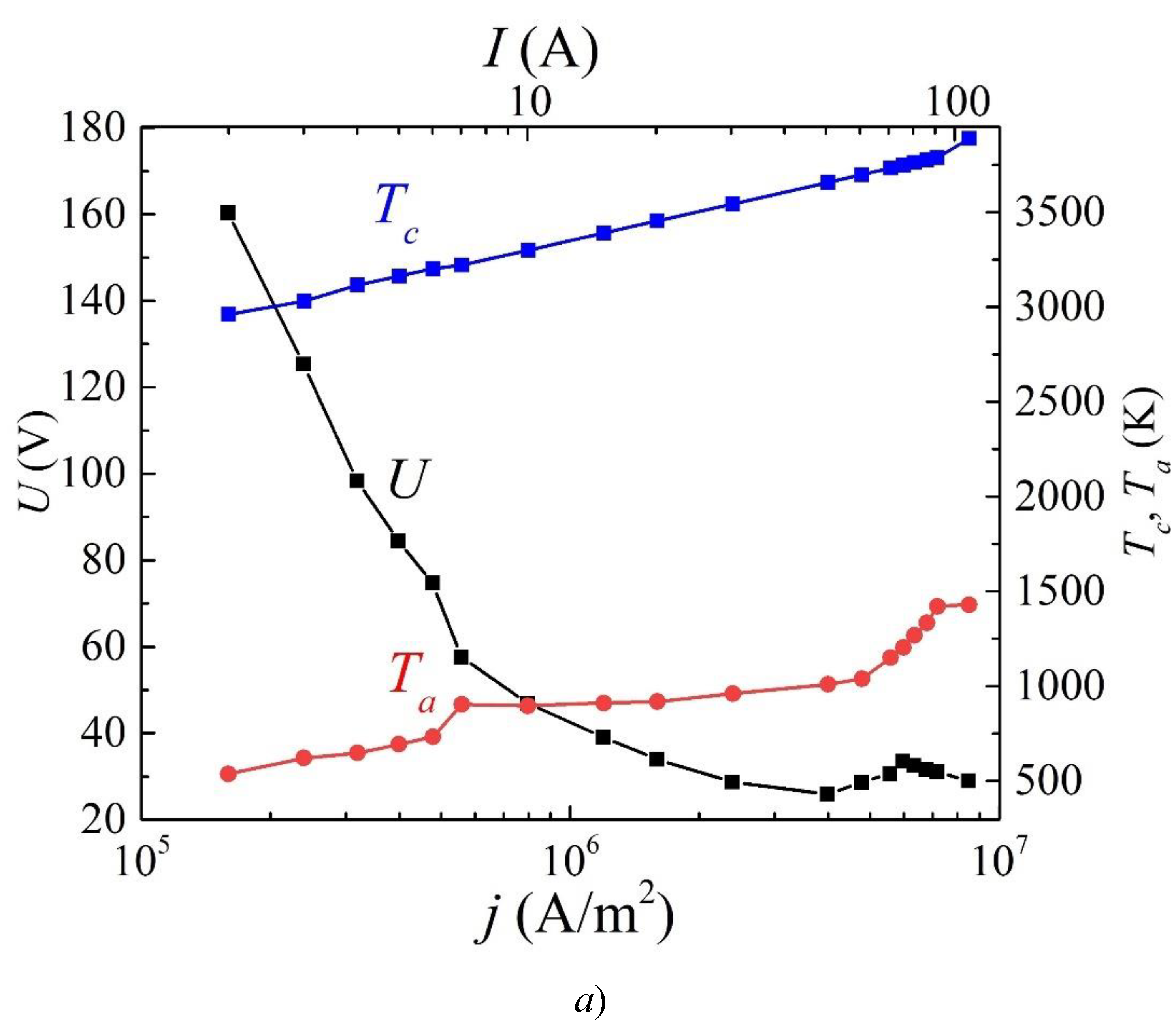

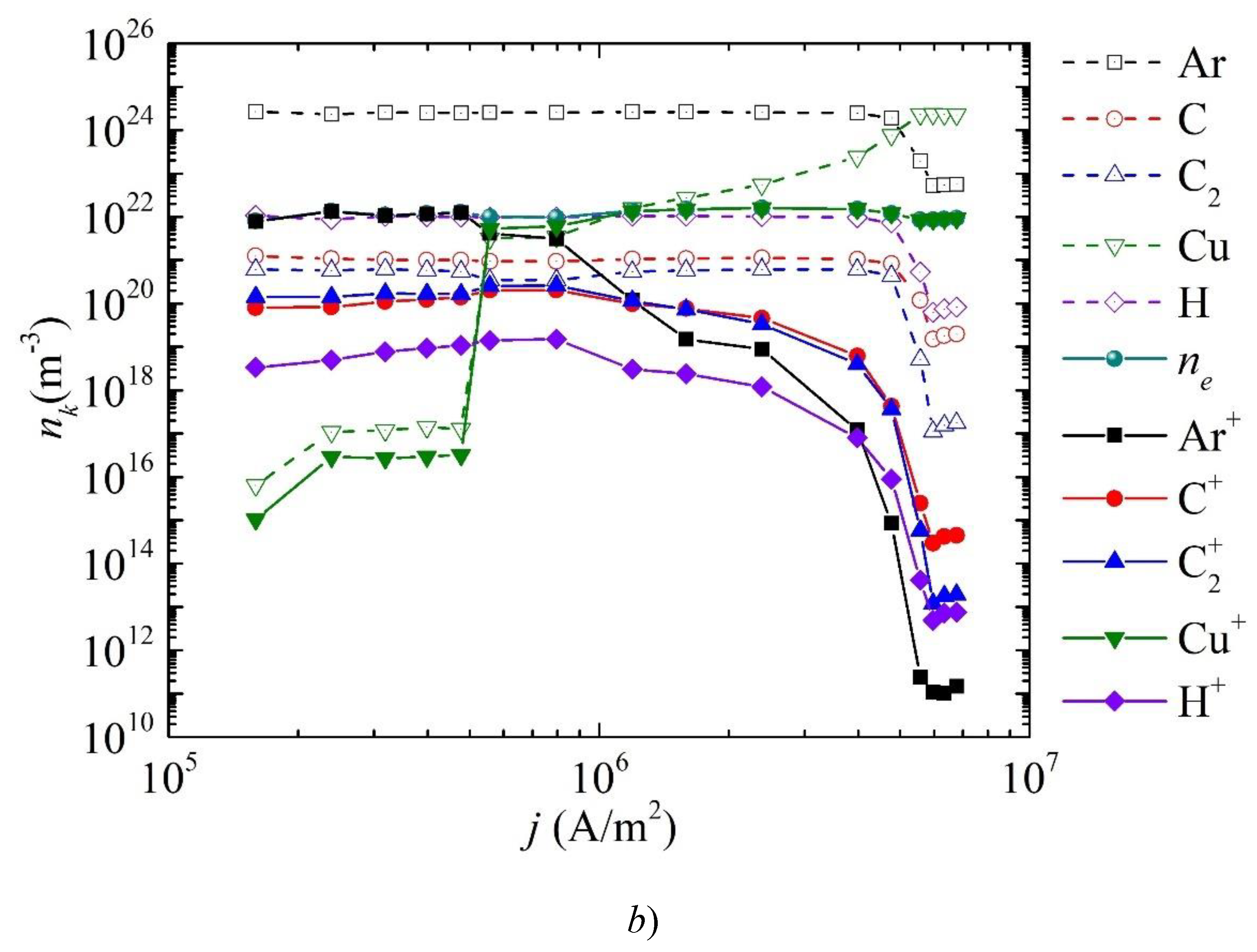

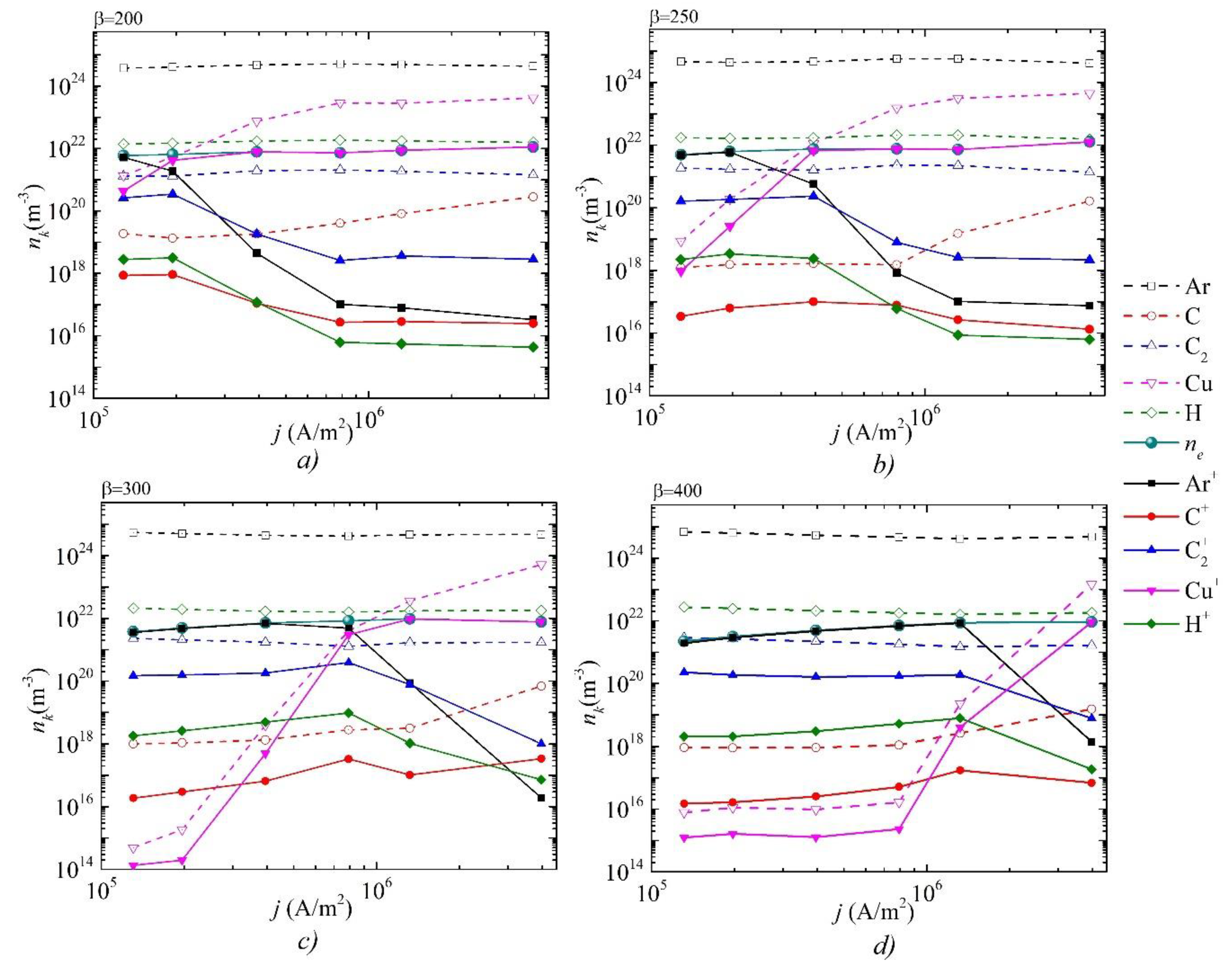

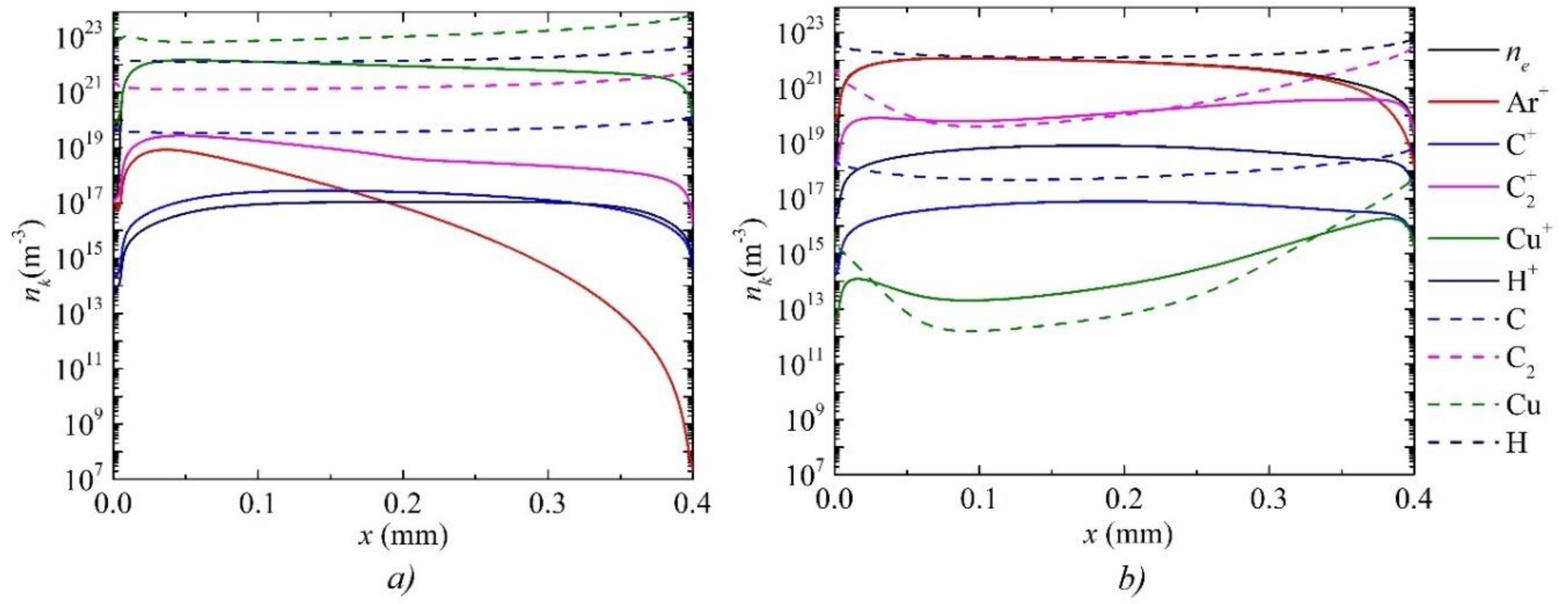

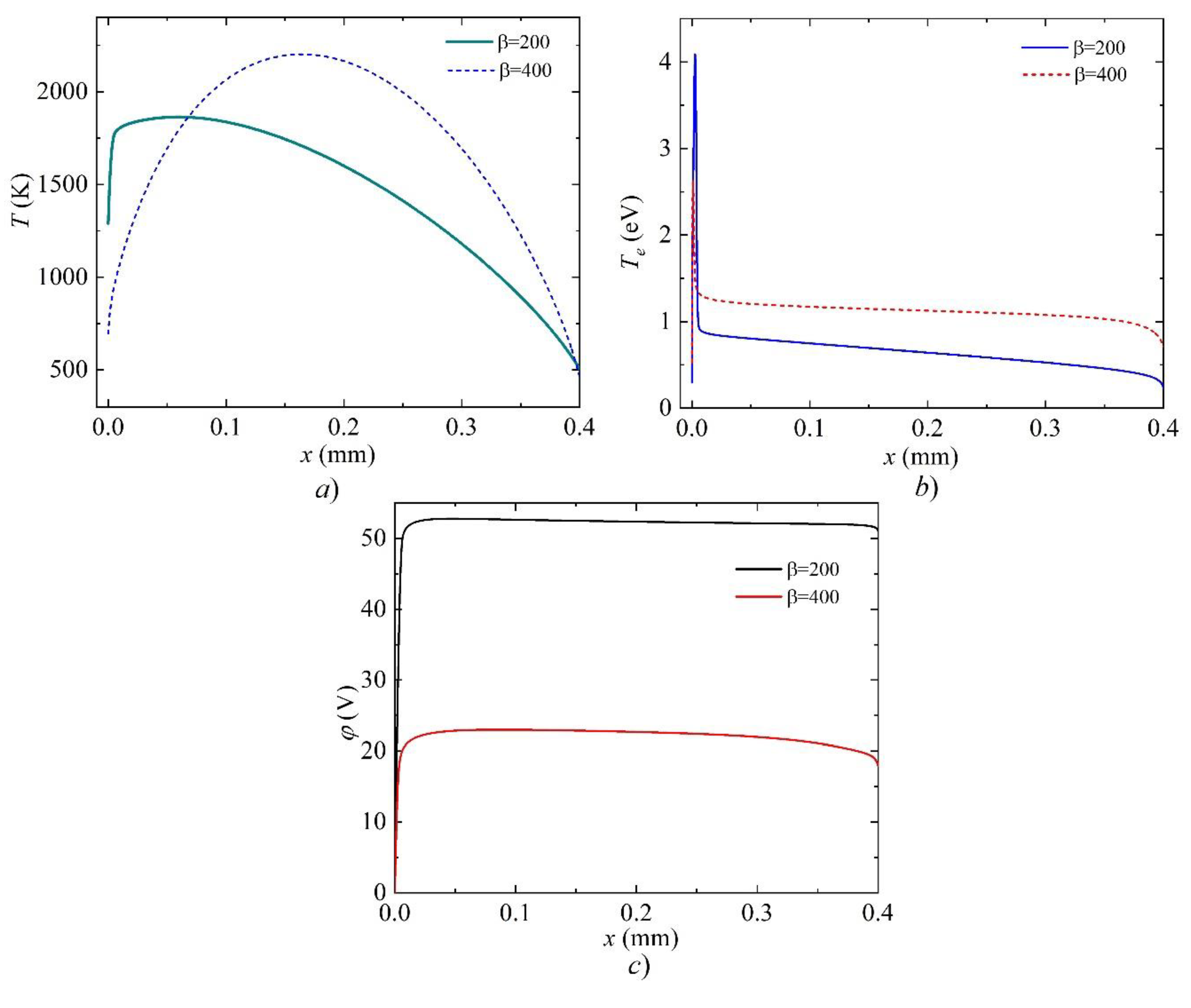

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| R | Reaction | Reaction constant kj *, m3/s, m6/s, or 1/s | Reference |

| 1 | [58] | ||

| 2 | [58] | ||

| 3 | [58] | ||

| 4 | [58] | ||

| 5 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 6 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 7 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 8 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 9 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 10 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 11 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 12 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 13 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 14 | [62,63,64] | ||

| 15 | [62,63,64] |

| R | Reaction | Reaction constant kj * | Energy (eV) | Reference |

| 1 | - | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 2 | 12.9 | [86] | ||

| 3 | 14.3 | [86] | ||

| 4 | 7.5 | [86] | ||

| 5 | 16.2 | [86] | ||

| 6 | 9.1 | [86] | ||

| 7 | 22.2 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 8 | 15.5 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 9 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 10 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 11 | 11 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 12 | 11 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 13 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 14 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 15 | 11 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 16 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 17 | 0.11, 0.36 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 18 | - | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 19 | 11 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 20 | 13 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 21 | 12 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 22 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 23 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 24 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 25 | 11 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 26 | 13 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 27 | 12 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 28 | - | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 29 | 12 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 30 | 10.5 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 31 | 12 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 32 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 33 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 34 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 35 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 36 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 37 | 12 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 38 | 8.1 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 39 | - | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 40 | 11.43 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 41 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 42 | 8.7 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 43 | 10 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 44 | 8.8 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 45 | 12 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 46 | 11.8 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 47 | - | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 48 | - | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 49 | 15.4 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 50 | 13.6 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 51 | 14.68 | [86,90,91,92] | ||

| 52 | - | [70,71] | ||

| 53 | - | [70,71] | ||

| 54 | 11.26 | [70,71] | ||

| 55 | 8.864 | [70,71] | ||

| 56 | -8.864 | [70,71] | ||

| 57 | 2.414 | [70,71] | ||

| 58 | 11.79 | [70,71] | ||

| 59 | 2.394 | [70,71] | ||

| 60 | -2.394 | [70,71] | ||

| 61 | 9.396 | [70,71] | ||

| 62 | 6.1 | [70,71] | ||

| 63 | - | [70,71] | ||

| 64 | - | [70,71] | ||

| 65 | - | [70,71] | ||

| 66 | 7.14×106 | - | [70,71] |

| R | Reaction | Reaction constant kj , m3/s, m6/s, or 1/s | Reference |

| Reactions involving neutral particles | |||

| 1 | [87] | ||

| 2 | [87] | ||

| 3 | [87] | ||

| 4 | [87] | ||

| 5 | [87] | ||

| 6 | [87] | ||

| 7 | [87] | ||

| 8 | [87] | ||

| 9 | [87] | ||

| 10 | [87] | ||

| 11 | [87] | ||

| 12 | [87] | ||

| 13 | [87] | ||

| 14 | [87] | ||

| 15 | [87] | ||

| 16 | [87] | ||

| 17 | [87] | ||

| 18 | [87] | ||

| 19 | [87] | ||

| 20 | * | [70,71] | |

| 21 | * | [70,71] | |

| 22 | * | [70,71] | |

| 23 | [70,71] | ||

| 24 | [70,71] | ||

| 25 | [70,71] | ||

| 26 | [87] | ||

| 27 | [87] | ||

| 28 | [87] | ||

| 29 | [87] | ||

| 30 | [87] | ||

| 31 | [87] | ||

| Reactions involving ions | |||

| 32 | [88] | ||

| 33 | [88] | ||

| 34 | [88] | ||

| 35 | [88] | ||

| 36 | [88] | ||

| 37 | [88] | ||

| 38 | [88] | ||

| 39 | [88] | ||

| 40 | [88] | ||

| 41 | [88] | ||

| 42 | [88] | ||

| 43 | [88] | ||

| 44 | [88] | ||

| 45 | [88] | ||

| 46 | [88] | ||

| 47 | [88] | ||

| 48 | [88] | ||

| 49 | [88] | ||

| 50 | [88] | ||

| 51 | [88] | ||

| 52 | [88] | ||

| 53 | [88] | ||

| 54 | [88] | ||

| 55 | [88] | ||

| 56 | [70,71] | ||

| 57 | [70,71] | ||

| 58 | [70,71] | ||

| 59 | * | [70,71] | |

| 60 | * | [70,71] | |

| 61 | * | [70,71] | |

| 62 | [14] | ||

| 63 | [14] | ||

| 64 | [14] | ||

| 65 | [14] | ||

| 66 | [14] | ||

| R | symbol | energy (eV) | stat weight | Effective Level Components |

| 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 2 | Cu(D1) | 1.39 | 6 | |

| 3 | Cu(D2) | 1.64 | 4 | |

| 4 | Cu(P1) | 3.79 | 2 | |

| 5 | Cu(P2) | 3.82 | 4 | |

| 6 | Cu* | 5.20 | 60 | |

| 7 | Cu** | 6.17 | 16 | |

| 8 | Cu+ | 7.72 | 1 | Cu+ |

| R | Reaction | Reaction constant kj , m3/s, m6/s, | Reference |

| 1 | [93,94,95] | ||

| 2 | [93,94,95] | ||

| 3 | [93,94,95]* | ||

| 4 | [93,94,95]* | ||

| 5 | [93,94,95] | ||

| 6 | [93,94,95] | ||

| 7 | [93,94,95] | ||

| 8 | [93,94,95]** |

References

- Journet, C.; Picher, M.; Jourdain, V. Carbon nanotube synthesis: from large-scale production to atom-by-atom growth. Nanotechnology. 2012, 23, 142001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeta, M.; Murphy, A.B. Thermal plasmas for nanofabrication. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 174025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyyappan, M. Plasma nanotechnology: past, present and future. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 174002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrikov, K. Plasma Nanoscience: Basic Concepts and Applications of Deterministic Nanofabrication, Wiley-VCH Verlag, 2008; pp.1-563.

- Jiang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Dai, L.; He, Z. High-activity and stability graphite felt supported by Fe, N, S co-doped carbon nanofibers derived from bimetal-organic framework for vanadium redox flow battery. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2023, 460, 141751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journet, C.; Maser, W.K.; Bernier, P.; Loiseau, A.; Lamy, M. de la Chapelle; Lefrant, S.; Deniard, P.; Lee, R.; Fischer, J.E. Largescale production of single-walled carbon nanotubes by the electric-arc technique. Nature. 1997, 388, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovich, I.; Baalrud, S. D.; Bogaerts, A.; et al. The 2017 Plasma Roadmap: Low temperature plasma science and technology. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2017, 50, 323001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovich, I.; Agarwal, S.; Ahedo, E.; et al. The 2022 Plasma Roadmap: low temperature plasma science and technology. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2022, 55, 373001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappim, W; Neto, B. B.; Shiotaniet, M.; et al. Plasma-Assisted Nanofabrication: The Potential and Challenges in Atomic Layer Deposition and Etching. Nanomaterials. 2022, 12, 19–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miakonkikh, A.; Kuzmenko, V. Formation of Black Silicon in a Process of Plasma Etching with Passivation in a SF6/O2 Gas Mixture. Nanomaterials. 2024, 14, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrikov, K. ; Cvelbar, U; and Murphy, A. B. Plasma nanoscience: setting directions, tackling grand challenges // Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2011, 44, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.H.; Koga, K.; Hao, Y.; Attri, P.; Okumura, T.; Kamataki, K.; Itagaki, N.; Shiratani, M.; Oh, J.-S.; Takabayashi, S.; et al. Time of Flight Size Control of Carbon Nanoparticles Using Ar+CH4 Multi-Hollow Discharge Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition Method. Processes. 2021, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganov, D.; Bundaleska, N.; Tatarova, E. On the plasma-based growth of ‘flowing’graphene sheets at atmospheric pressure conditions. Plasma Sources Science and Technology. 2015, 25, 015013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denysenko, I. B.; Xu, S.; Long, J. D. Inductively coupled Ar/CH4/H2 plasmas for low-temperature deposition of ordered carbon nanostructures. Journal of applied physics. 2004, 95, 2713–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim H., J.; Lee, K.; Park, H. Effect of dilution gas on the distribution characteristics of capacitively coupled plasma by comparing SiH4/He and SiH4/Ar. Plasma Sources Science and Technology. 2023, 32, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundrapu, M; Keidar, M. Numerical simulation of carbon arc discharge for nanoparticle synthesis. Phys. Plasmas. 2012, 19, 073510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keidar, M.; Beilis, I. I. Modeling of atmospheric-pressure anodic carbon arc producing carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhang, T.; Chen, H.; Ma, Y. The growth mechanism of few-layer graphene in the arc discharge process. Carbon. 2016, 102, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. S.; Kodama, S.; Sekiguchi, H. Preparation of Metal Nitride Particles Using Arc Discharge in Liquid Nitrogen. Nanomaterials, 2021, 11, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekselman, V.; Raitses, Y.; Shneider, M. N. Growth of nanoparticles in dynamic plasma. Physical Review E. 2019, 99, 6–063205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timerkaev, B. A.; et al. Germanium catalyst for plasma-chemical synthesis of diamonds. High Energy Chemistry. 2019, 53, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musielok, J. Non-Equilibrium Effects in He-Ar-H Arc Plasma. Contributions to Plasma Physics. 1977. 17.

- Cram, L. E.; Poladian, L.; Roumeliotis, G. Departures from equilibrium in a free burning argon arc. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 1988, 21, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, A. J. D.; Haddad, G. N. Rayleigh scattering measurements in a free-burning argon arc. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 1988, 21, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benilov, M. S. Understanding and modelling plasma–electrode interaction in high-pressure arc discharges: a review. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2008, 41, 144001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenbach, S. Recent progress in magnetic fluid research J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2004, 16, R1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. ; Zhai, P; Zhang, Z; Zhou, Y; Ju, J; Shi, Z; Ma, D; Han, R. P. S.; Huang, F. Synthesis of highly stable graphene-encapsulated iron nanoparticles for catalytic syngas conversion Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, S.; Lu, J.; Yu, G.; Yin, S.; Luo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, W.; Shen, P. K. Carbon-encapsulated WOx hybrids as efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsu, M.; Yoshida, T.; Mesko, M.; Ogino, A.; Matsuda, T.; Tanaka, T.; Tatsuoka, H.; Murakami, K. Narrow multi-walled carbon nanotubes produced by chemical vapor deposition using graphene layer encapsulated catalytic metal particles. Carbon. 2006, 44, 3336–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Shen, Y.; Cong, H. Multifunctional Fe3O4@C-based nanoparticles coupling optical/MRI imaging and pH/photothermal controllable drug release as efficient anti-cancer drug delivery platforms. Nanotechnology. 2019, 30, 425102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K. L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L. L.; Schatz, G. C. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Corma, A. Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: from single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4981–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenya, B. R. Synthesis and catalytic properties of metal nanoparticles: size, shape, support, composition, and oxidation state effects. Thin Solid Films. 2010, 518, 3127–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, S.; He, D.; Haghi-Ashtiani, P.; Dichiara, A.; Zimmer, L.; Bai, J. Evolution of nanoparticles in the gas phase during the floating chemical vapor deposition synthesis of carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. 2018, 122, 6437–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, C.; Schäffel, F.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Queitsch, U.; Sparing, M.; Rellinghaus, B.; Lafdi, K.; Schultz, L. , Büchner, B. and Rümmeli, M. H. Catalyst poisoning by amorphous carbon during carbon nanotube growth: fact or fiction? ACS Nano. 2011, 5, 8928–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Lian, Y.; Liao, F. H.; Zhou, X.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Iijima, S.; Li, H.; Yue, K. T.; Zhang, S.-L. Large scale synthesis of single-wall carbon nanotubes by arc-discharge method. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2000, 61, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journet, C.; Maser, W.K.; Bernier, P.; Loiseau, A.; De La Chapelle, M. L.; Lefrant, S.; Deniard, P.; Lee, R.; Fischer, J. E. Large-scale production of single-walled carbon nanotubes by the electric-arc technique Nature. 388.

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature, 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatom, S.; Selinsky, R. S.; Koel, B. E.; and Raitses, Y. Synthesis-on” and “synthesis-off” modes of carbon arc operation during synthesis of carbon nanotubes. Carbon. 2017, 125, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keidar, M.; Waas, A. M. On the conditions of carbon nanotube growth in the arc discharge. Nanotechnology 2004, 15, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journet, C.; Picher, M.; Jourdain, V. Carbon nanotube synthesis: from large-scale production to atom-by-atom growth. Nanotechnology. 2012, 23, 142001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C. L.; Kurtz, A.; Park, H.; Lieber, C. M. Diameter-controlled synthesis of carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. 2002, 106, 2429–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasibulin, A. G.; Pikhitsa, P. V.; Jiang, H.; Kauppinen, E. I. Correlation between catalyst particle and single-walled carbon nanotube diameters. Carbon. 2005, 43, 2251–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Graves, B.; De Volder, M.; Yang, W.; Johnson, T.; Wen, B.; Su, W.; Nishida, R.; Xie, S.; Boies, A. High-precision solid catalysts for investigation of carbon nanotube synthesis and structure. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagatsu, M.; Yoshida, T.; Mesko, M.; Ogino, A.; Matsuda, T.; Tanaka, T.; Tatsuoka, H.; Murakami, K. Narrow multi-walled carbon nanotubes produced by chemical vapor deposition using graphene layer encapsulated catalytic metal particles. Carbon. 2006, 44, 3336–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. L.; Zhang, Z. D.; Xiao, Q. F.; Zhao, X. G.; Chuang, Y. C.; Jin, S. R.; Sun, W. M.; Li, Z. J. Zheng, Z. X. and Dong, X. L. Characterization of ultrafine -Fe(C), -Fe(C) and Fe3C particles synthesized by arc-discharge in methane. J. Mater. Sci. 1998, 33, 1915–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Xiao, F.; Cui, Z. Preparation and structure of carbon encapsulated copper nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2008, 10, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Rao, Y.; Guo, J.; Qin, G. Multiple-phase carbon-coated FeSn2/Sn nanocomposites for high-frequency microwave absorption. Carbon 2016, 96, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, V.; Sakthi Kumar, D.; Yoshida, Y.; Makarewicz, M.; Tabi´s, W.; Anantharaman, M. R. Synthesis and properties of highly stable nickel/carbon core/shell nanostructures. Carbon 2010, 48, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N. C.; Talukder, M. R. Effect of pressure on the properties and species production in gliding arc Ar, O2, and air discharge plasmas Phys. Plasmas 2018, 25, 093502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, B.; et al. Effect of varying N2 pressure on DC arc plasma properties and microstructure of TiAlN coatings Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 095015. [Google Scholar]

- Gutsch, A.; Mühlenweg, H.; Krämer, M. Tailor-made nanoparticles via gas-phase synthesis. Small 2004, 1, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Tashiro, S.; Satoh, T.; Murphy, A. B.; a Lowke, J. J. Influence of shielding gas composition on arc properties in TIG welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2008, 13, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musikhin, S.; Nemchinsky; V. A., Raitses, Y. Growth of metal nanoparticles in hydrocarbon atmosphere of arc discharge. Nanotechnology. 2024, 35, 385601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P. L.; Hanson, R. J.; Carlos, S.; Taylor, R. W. 2017 Plasma reactor. US Patent 9,574, 086 B.

- Predtechenskiy 2020 Method and apparatus for producing carbon nanostructures US Patent 2020/0239316 A1.

- Saifutdinov, A. I. Numerical study of various scenarios for the formation of atmospheric pressure DC discharge characteristics in argon: from glow to arc discharge. Plasma Sources Science and Technology. 2022, 31, 094008–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A.I. Unified simulation of different modes in atmospheric pressure DC discharges in nitrogen. Journal of Applied Physics, 2021, 129, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A.I.; Timerkaev, B.A.; Saifutdinova, A.A. Features of Transient Processes in DC Microdischarges in Molecular Gases: From a Glow Discharge to an Arc Discharge with an Unfree or Free Cathode Regime. JETP Letters, 2020, 112, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A. I.; Fairushin I., I.; Kashapov N., F. Analysis of various scenarios of the behavior of voltage-current characteristics of direct-current microdischarges at atmospheric pressure. JETP Letters, 2016, 104, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeva, M.; Loffhagen, D.; Uhrlandt, D. Unified non-equilibrium modelling of tungsten-inert gas microarcs in atmospheric pressure argon. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing, 2019, 39, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeva, M.; et al. Fluid modelling of DC argon microplasmas: effects of the electron transport description. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing, 2019, 39, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeva, M.; Loffhagen, D.; Uhrlandt, D. Unified non-equilibrium modelling of tungsten-inert gas microarcs in atmospheric pressure argon. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing, 2019, 39, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benilov M., S. Modeling the physics of interaction of high-pressure arcs with their electrodes: advances and challenges. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 2020, 53, 013002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrabry, A.; Kaganovich, I. D.; Nemchinsky, V.; Khodak, A. Investigation of the short argon arc with hot anode. II. Analytical model. Physics of Plasmas. 2018, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Khrabry, A.; Kaganovich, I. D.; Khodak, A.; Vekselman, V.; Li, H. P. Validated two-dimensional modeling of short carbon arcs: Anode and cathode spots. Physics of Plasmas. 2020, 27, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrabry, A.; Kaganovich, I. D.; Nemchinsky, V.; Khodak, A. Investigation of the short argon arc with hot anode. I. Numerical simulations of non-equilibrium effects in the near-electrode regions. Physics of Plasmas. 2018, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A. I.; Sorokina A., R.; Boldysheva V., K.; Latypov E., R.; Saifutdinova A., A. Evaporation of Carbon Atoms and Molecules in Helium by Low-Current Arc Discharge with Graphite Electrodes. High Energy Chemistry, 2022, 56, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour A., R.; Hara, K. Multispecies plasma fluid simulation for carbon arc discharge. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2019, 52, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A.; Timerkaev, B. Modeling and Comparative Analysis of Atmospheric Pressure Anodic Carbon Arc Discharge in Argon and Helium–Producing Carbon Nanostructures. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeva, M.; et al. Unified modelling of low-current short-length arcs between copper electrodes. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 2020, 54, 2025203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benilov, M. S.; et al. Vaporization of a solid surface in an ambient gas. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 1993; 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A. I.; Germanov, N. P.; Sorokina, A. R.; Saifutdinova, A. A. Numerical Analysis of the Influence of Evaporation of the High-and Low-Melting-Point Anode Materials on Parameters of a Microarc Discharge. Plasma Physics Reports, 2023, 49, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiser, Yu.P. Physics of gas discharge, Moscow: Intellect, 2009. [In Russian].

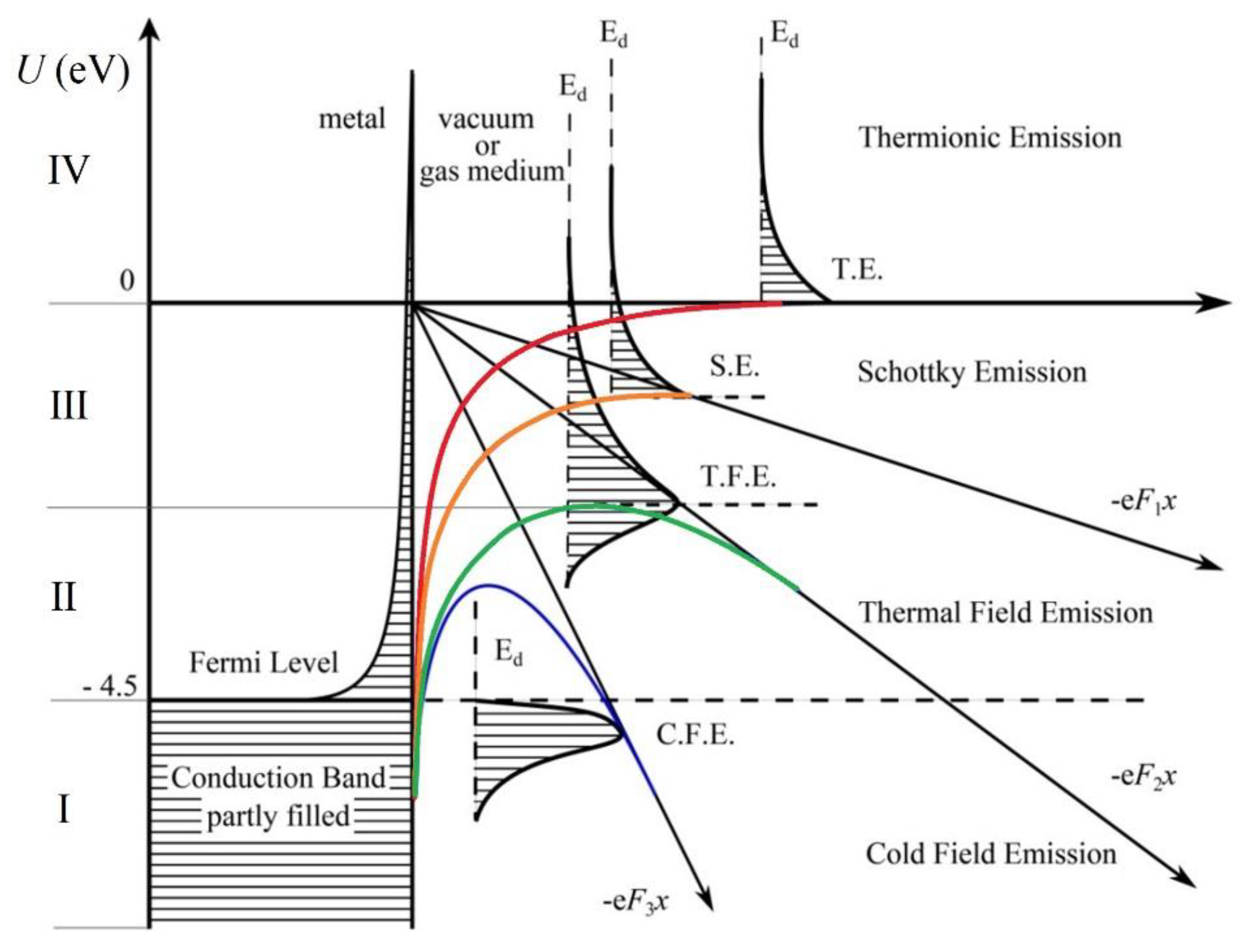

- Murphy, E. L.; Good Jr., R. H. Thermionic emission, field emission, and the transition region. Physical review. 1464. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker, G.; Müller, K. G. Electron emission from the arc cathode under the influence of the individual field component. Journal of Applied Physics. 1959, 30, 1466–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulombe, S. , Meunier, J. L. A comparison of electron-emission equations used in arc-cathode interaction calculations. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 1997, 30, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemchinsky, V. Simple algorithm to calculate TF electron emission current density. IEEE transactions on dielectrics and electrical insulation. 2004, 11, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benilov, M. S.; Benilova, L. G. Field to thermo-field to thermionic electron emission: A practical guide to evaluation and electron emission from arc cathodes. Journal of Applied Physics. 2013, 114, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantzsche, E. The thermo-field emission of electrons in arc discharges. Beiträge aus der Plasmaphysik. 1982, 22, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. , Chen, J., Wang, H., Fu, Y. Unification of the breakdown criterion for thermal field emission-driven microdischarges. Applied Physics Letters, 2024, 125, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Knacke, O.; Stranski, I. N. The mechanism of evaporation. Progress in Metal Physics, 1956, 6, 181–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifutdinov, A. I.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Different Sets of Elementary Processes in Modeling DC Discharge in Argon at Atmospheric Pressure //High Energy Chemistry. 2023, 57, S178–S181. 57.

- Janev, R. K.; Reiter, D. Collision processes of C2, 3Hy and C2, 3Hy+ hydrocarbons with electrons and protons. Physics of Plasmas. 2004, 11, 780–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alman, D. A.; Ruzic, D. N.; Brooks J., N. A hydrocarbon reaction model for low temperature hydrogen plasmas and an application to the Joint European Torus. Physics of plasmas. 2000, 7, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintze, M.; Magureanu, M.; Kettlitz, M. Mechanism of C 2 hydrocarbon formation from methane in a pulsed microwave plasma. Journal of applied physics. 2002, 92, 7022–7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, K.; Nishida, M.; Harima, H.; Urano, Y. Diagnostics and modelling of a methane plasma used in the chemical vapour deposition of amorphous carbon films. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 1984, 17, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bie, C.; Verheyde, B.; Martens, T.; van Dijk, J.; Paulussen, S.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma Processes and Polymers. 2011, 8, 1033–1058. 8.

- Wang, Y.; Zatsarinny, O.; Bartschat, K. Physical Review A. 2013, 87, 012704.

- https://www.lxcat.net/IST-Lisbon.

- https://www.lxcat.net/Hayashi .

- Bogaerts, A.; Gijbels, R.; Carman, R. Collisional–radiative model for the sputtered copper atoms and ions in a direct current argon glow discharge. Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy, 1679; 53. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts, A.; Gijbels, R. Hybrid modeling network for a helium–argon–copper hollow cathode discharge used for laser applications. Journal of applied physics. 2002, 92, 6408–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeva, M.; et al. Unified modelling of low-current short-length arcs between copper electrodes. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2020, 54, 025203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).