Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock-Dairy Manure and Activated Carbon

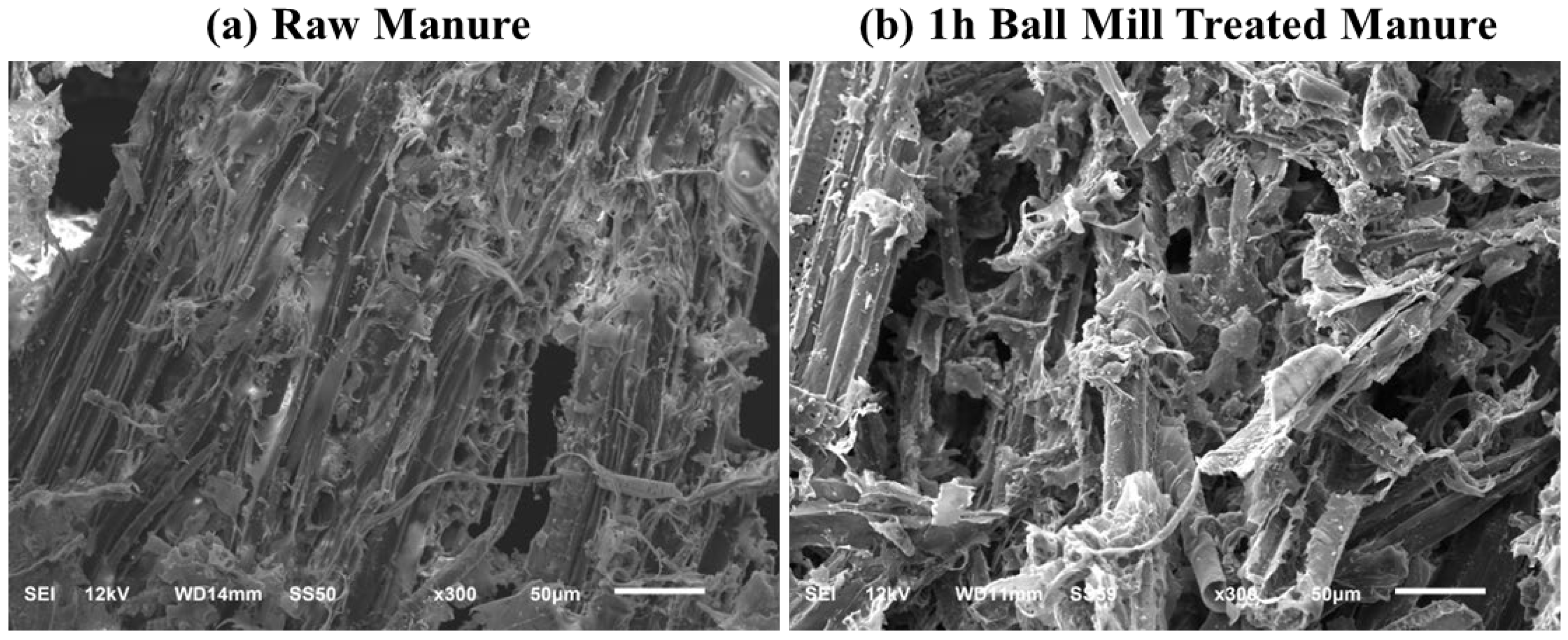

2.2. One-Pot Ball Mill Pretreatment

2.3. Semi-Continuous Anaerobic Digestion of Dairy Manure

2.4. Physical and Chemical Analysis

2.5. Microbial Community Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Performance of Semi-Continuous AD of Dairy Manure

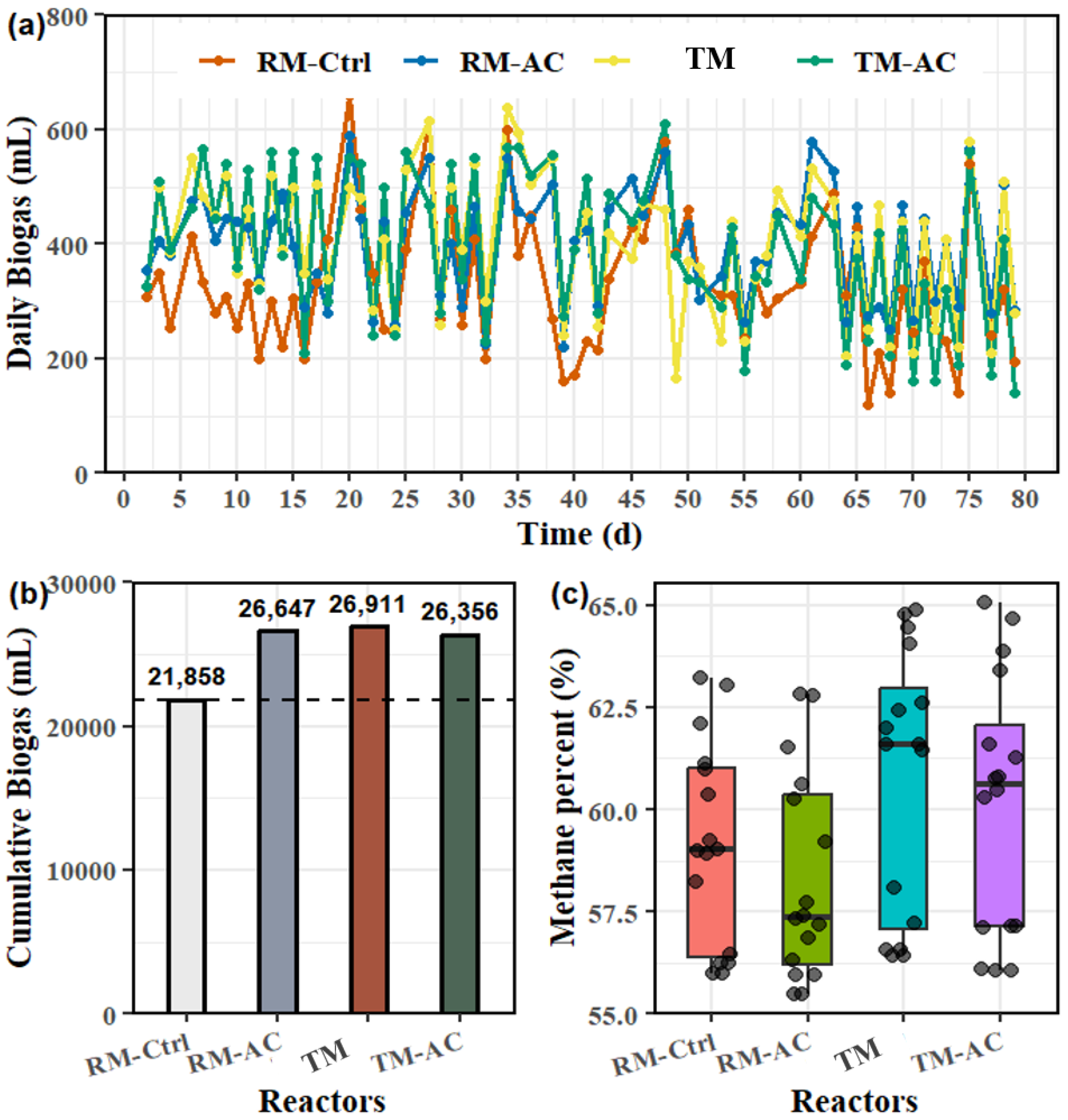

3.1.1. Biogas Production and Methane Percentages

3.1.2. Biochemical Characteristics of Digestates

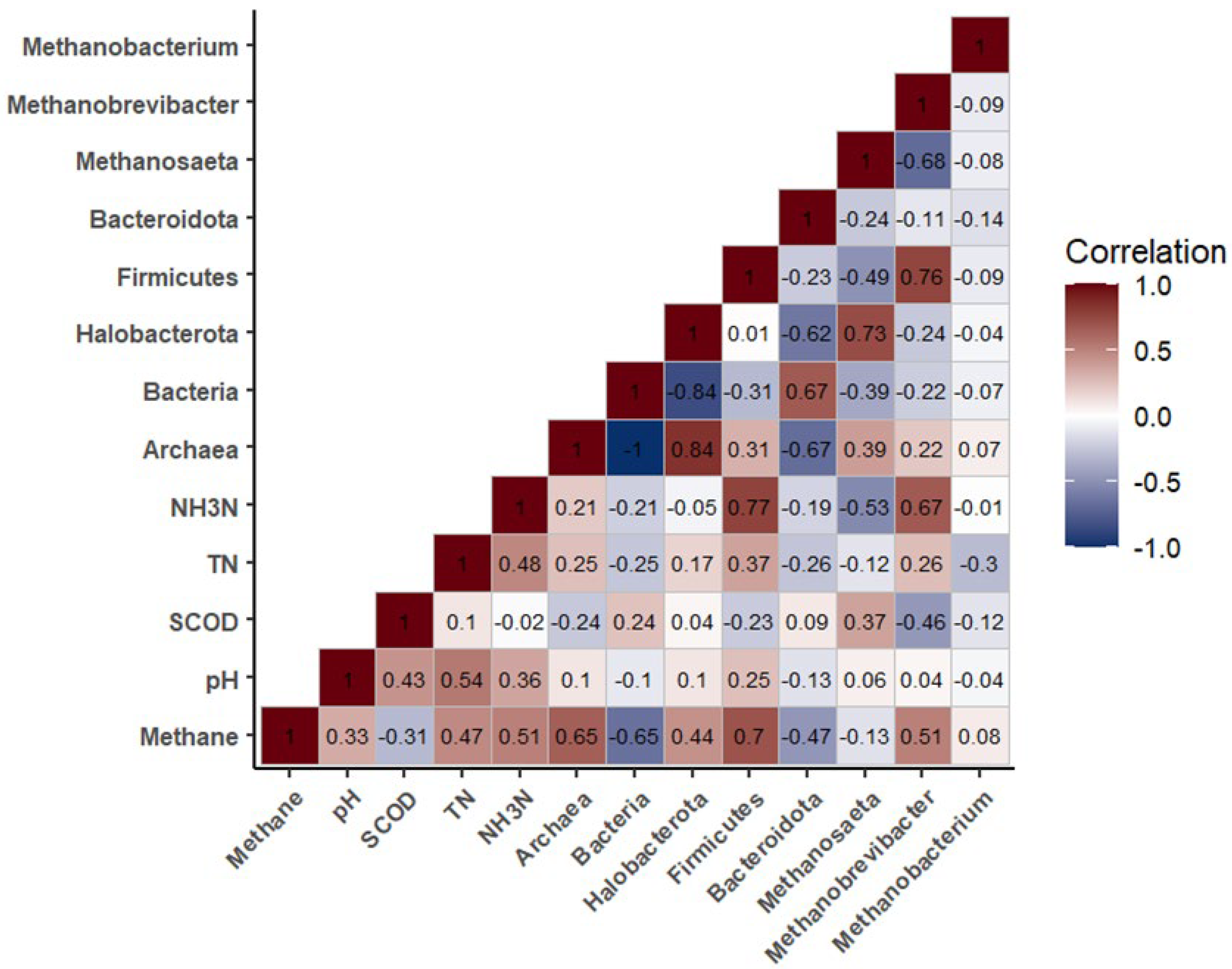

3.2. Microbial Communities Analysis

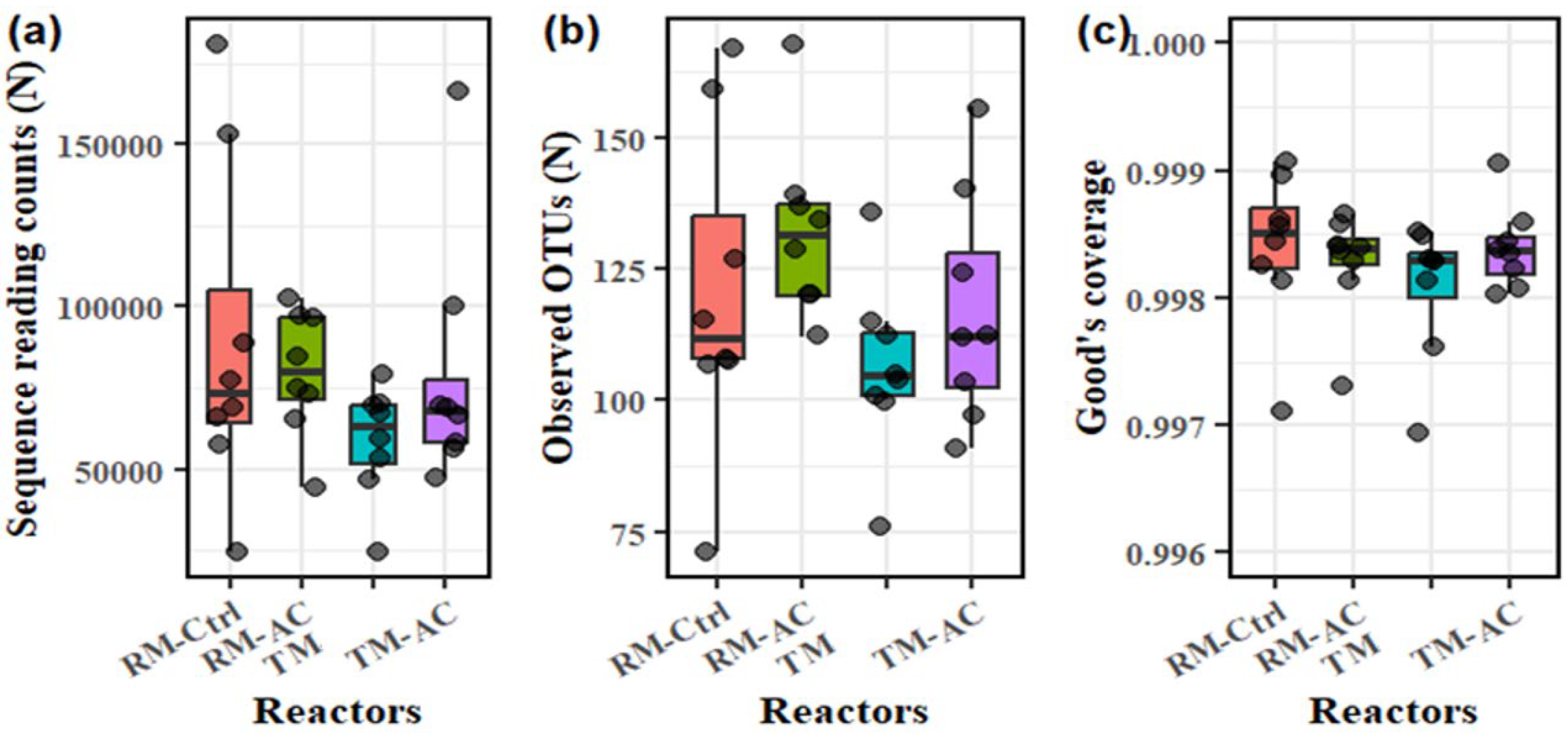

3.2.1. The Amplicon Sequencing Results

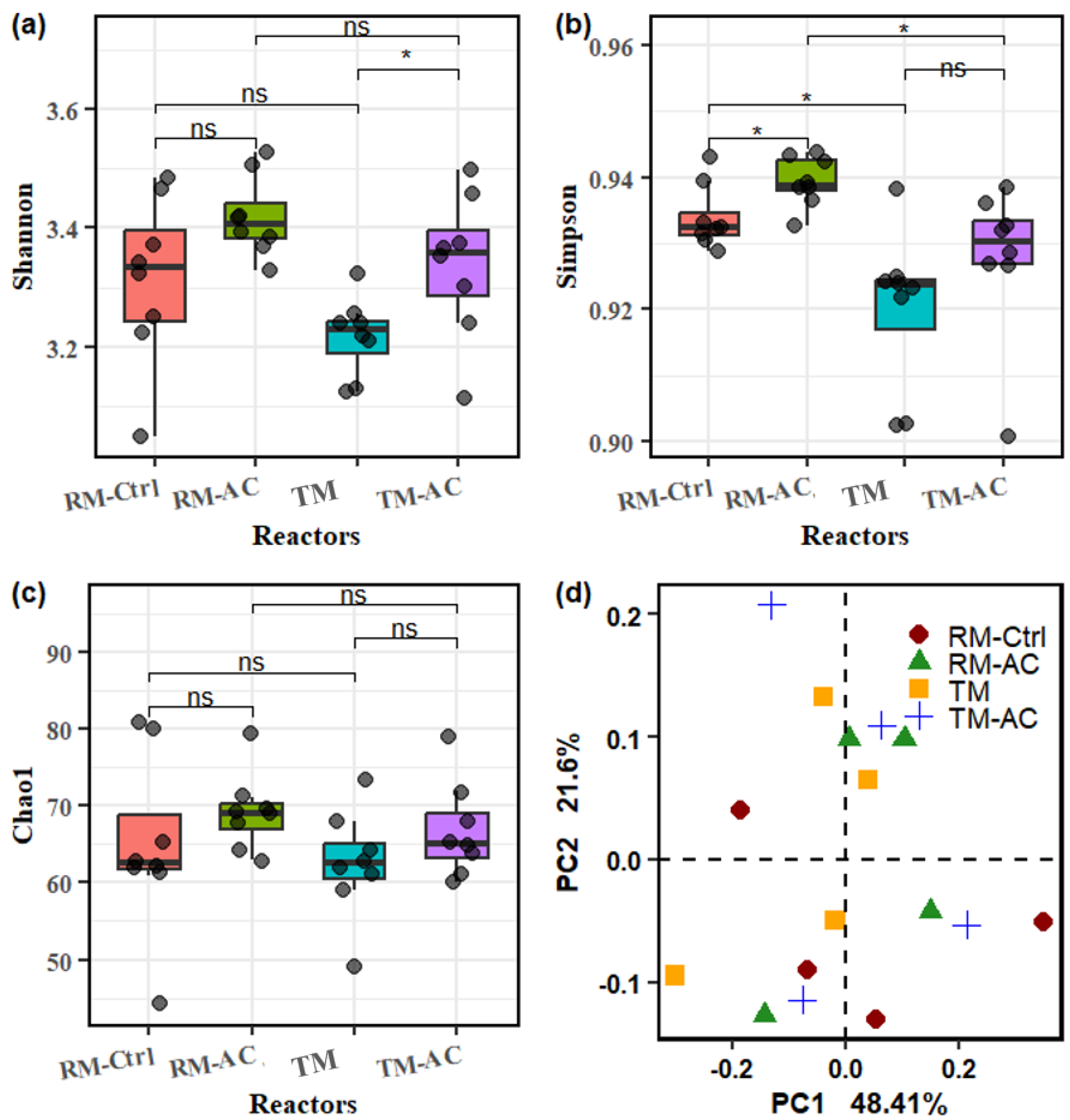

3.2.2. Microbial Diversity

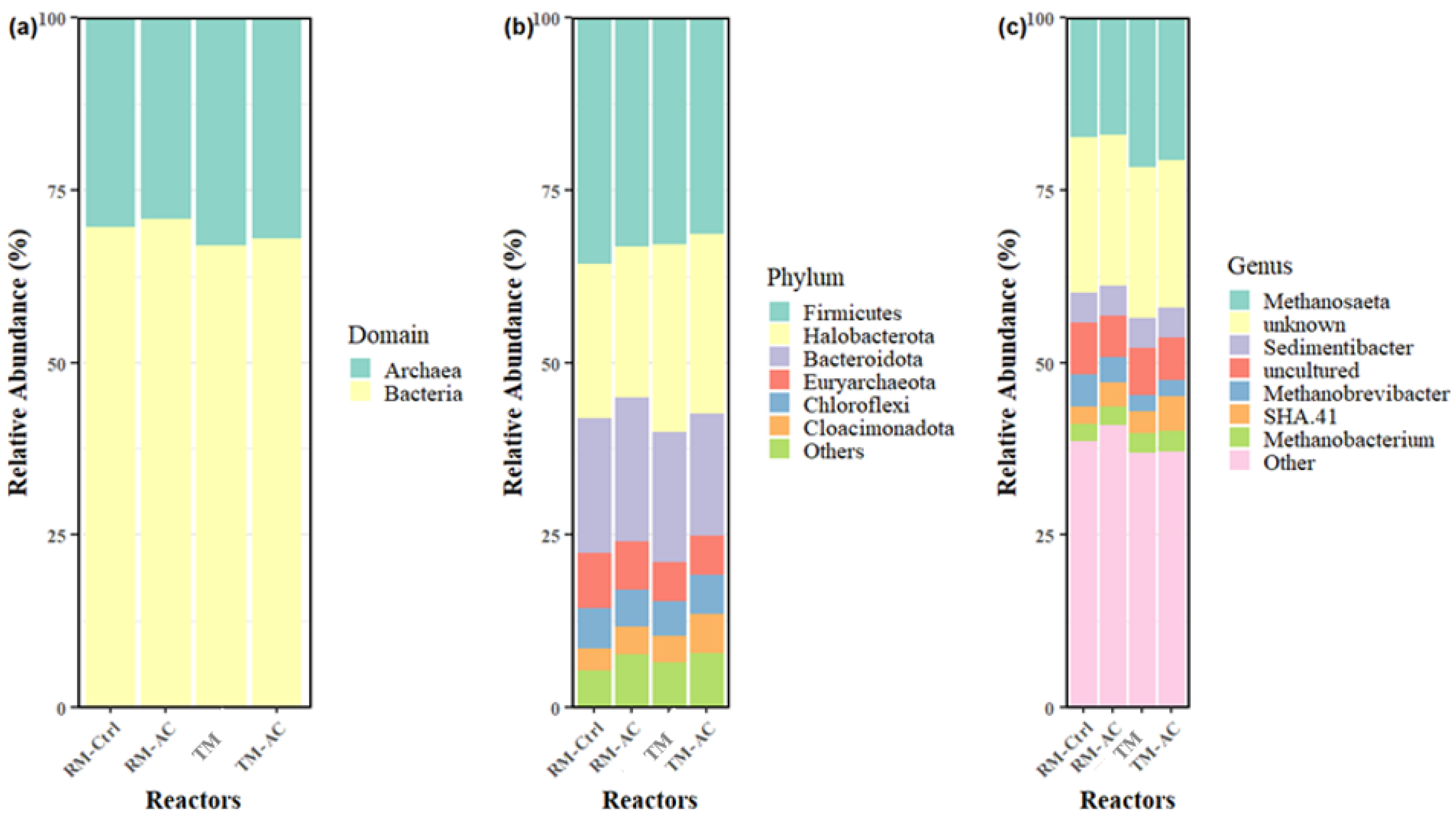

3.2.3. Microbial Abundance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| SCAD | South campus anaerobic digester |

| PCRs | Polymerase chain reactions |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- U.S. EPA. Inventory of U.S Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks. EPA 430-R-21-005. Environmental Protection Agency 2021.

- Njuki, E. Economic Research Service Economic Research Report Number 305 Sources, Trends, and Drivers of U. S. Dairy Productivity and Efficiency. 2022.

- Scarlat N, Dallemand JF, Fahl F. Biogas: Developments and perspectives in Europe. Renew Energy 2018;129. [CrossRef]

- Clemens J, Trimborn M, Weiland P, Amon B. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions by anaerobic digestion of cattle slurry. Agric Ecosyst Environ, vol. 112, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Glover CJ, McDonnell A, Rollins KS, Hiibel SR, Cornejo PK. Assessing the environmental impact of resource recovery from dairy manure. J Environ Manage 2023;330. [CrossRef]

- 2015-17 Biennium Technology Research and Extension Related to Anaerobic Digestion of Dairy Manure. n.d.

- Chen S, Liao W, C L, Wen Z, Kincaid RL, Harrison JH, et al. Value-Added Chemicals from Animal Manure. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory 2003;PNNL-14495.

- Isikgor FH, Becer CR. Lignocellulosic biomass: a sustainable platform for the production of bio-based chemicals and polymers. Polym Chem 2015;6. [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Chen L, Yuan K, Huang H, Yan Z. Ionic liquid pretreatment to enhance the anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol 2013;150. [CrossRef]

- Usman Khan M, Kiaer Ahring B. Improving the biogas yield of manure: Effect of pretreatment on anaerobic digestion of the recalcitrant fraction of manure. Bioresour Technol 2021;321. [CrossRef]

- Jurado E, Skiadas I V., Gavala HN. Enhanced methane productivity from manure fibers by aqueous ammonia soaking pretreatment. Appl Energy 2013;109. [CrossRef]

- Bruni E, Jensen AP, Angelidaki I. Steam treatment of digested biofibers for increasing biogas production. Bioresour Technol 2010;101. [CrossRef]

- Tsapekos P, Kougias PG, Frison A, Raga R, Angelidaki I. Improving methane production from digested manure biofibers by mechanical and thermal alkaline pretreatment. Bioresour Technol 2016;216. [CrossRef]

- Biswas R, Ahring BK, Uellendahl H. Improving biogas yields using an innovative concept for conversion of the fiber fraction of manure. Water Science and Technology 2012;66. [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki I, Ahring BK. Methods for increasing the biogas potential from the recalcitrant organic matter contained in manure. Water Science and Technology 2000;41. [CrossRef]

- Veluchamy C, Kalamdhad AS, Gilroyed BH. Advanced Pretreatment Strategies for Bioenergy Production from Biomass and Biowaste. Handbook of Environmental Materials Management, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mankar AR, Pandey A, Modak A, Pant KK. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: A review on recent advances. Bioresour Technol 2021;334. [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. Standard Methods 2005. ISBN 9780875532356.

- Takahashi S, Tomita J, Nishioka K, Hisada T, Nishijima M. Development of a prokaryotic universal primer for simultaneous analysis of Bacteria and Archaea using next-generation sequencing. PLoS One 2014;9. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Uludag-Demirer S, Fang D, Zhou L, Liu Y, Liao W, et al. Effects of pyrogenic carbonaceous materials on anaerobic digestion of a nitrogen rich organic waste-Swine manure. Energy & Fuels 2021;35.

- Chen R, Roos MM, Zhong Y, Marsh T, Roman MB, Hernandez Ascencio W, et al. Responses of anaerobic microorganisms to different culture conditions and corresponding effects on biogas production and solid digestate quality. Biomass Bioenergy 2016;85. [CrossRef]

- Tao N, Xu M, Wu X, Pi Z, Yu C, Fang D, et al. Supplementation of Schwertmannite improves methane production and heavy metal stabilization during anaerobic swine manure treatment. Fuel 2021;299. [CrossRef]

- Capson-Tojo G, Moscoviz R, Ruiz D, Santa-Catalina G, Trably E, Rouez M, et al. Addition of granular activated carbon and trace elements to favor volatile fatty acid consumption during anaerobic digestion of food waste. Bioresour Technol 2018;260. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhang J, Loh KC. Activated carbon enhanced anaerobic digestion of food waste – Laboratory-scale and Pilot-scale operation. Waste Management 2018;75. [CrossRef]

- Cuetos MJ, Martinez EJ, Moreno R, Gonzalez R, Otero M, Gomez X. Enhancing anaerobic digestion of poultry blood using activated carbon Enhancing anaerobic digestion of poultry blood. J Adv Res 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Smith KS, Ingram-Smith C. Methanosaeta, the forgotten methanogen? Trends Microbiol 2007;15. [CrossRef]

- Yue ZB, Ma D, Wang J, Tan J, Peng SC, Chen TH. Goethite promoted anaerobic digestion of algal biomass in continuous stirring-tank reactors. Fuel 2015;159. [CrossRef]

- Rotaru AE, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Shrestha M, Shrestha D, Embree M, et al. A new model for electron flow during anaerobic digestion: Direct interspecies electron transfer to Methanosaeta for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Energy Environ Sci 2014;7. [CrossRef]

- Lovley, DR. Syntrophy Goes Electric: Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer. Annu Rev Microbiol 2017;71. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Dairy manure | Activated carbon |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon (%TS) | 44.31 | 75.55±0.05 |

| Nitrogen (%TS) | 2.66 | 0.44±0.05 |

| Sulfur (%TS) | ND | 0.15±0.00 |

| Surface area (m2/g TS) | ND | 1,056±17.57 |

| C/N | 16.66 | ND |

| pH | 7.99±0.91 | ND |

| TS (%) | 13.45±0.22 | 97.52±0.55 |

| VS (% TS) | 11.92±0.19 | 92.9±0.06 |

| TN (mg/L) | 4,360±520 | ND |

| NH3-N (mg/L) | 732±23 | ND |

| COD (g/L) | 114.98±21.20 | ND |

| Reactors | RM-Ctrl | RM-AC | TM | TM-AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic inoculum (mL) | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Raw dairy manure (mL/every other day) |

50 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Ball mill-treated manure (mL/every other day) |

0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Activated carbon (g/every other day) |

0 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Groups | HRTs | pH | VS (%) | SCOD (mg/L) | TN (mg/L) | NH3-N (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM-Ctrl | HRT-1 | 7.49 | 1.98±0.04 | 5,750 | 2,690 | 1,120 |

| HRT-2 | 7.44 | 1.91±0.05 | 5,450 | 1,643 | 945 | |

| HRT-3 | 7.63 | 1.71±0.46 | 5,075 | 2,763 | 1,010 | |

| HRT-4 | 7.54 | 2.23±0.29 | 7,725 | 1,578 | 1,103 | |

| RM-AC | HRT-1 | 7.52 | 2.32±0.02 | 5,053 | 2,690 | 1,103 |

| HRT-2 | 7.47 | 2.31±0.19 | 4,455 | 1,705 | 900 | |

| HRT-3 | 7.69 | 2.29±0.03 | 3,755 | 2,653 | 928 | |

| HRT-4 | 7.49 | 2.39±0.26 | 6,425 | 1,890 | 978 | |

| TM | HRT-1 | 7.60 | 2.32±0.02 | 6,500 | 2,323 | 1,250 |

| HRT-2 | 7.55 | 2.40±0.06 | 6,275 | 1,930 | 755 | |

| HRT-3 | 7.60 | 2.14±0.18 | 4,755 | 1,823 | 753 | |

| HRT-4 | 7.33 | 2.37±0.04 | 6,400 | 1,638 | 585 | |

| TM-AC | HRT-1 | 7.61 | 2.53±0.08 | 5,750 | 2,185 | 1,198 |

| HRT-2 | 7.53 | 2.82±0.02 | 5,675 | 1,703 | 768 | |

| HRT-3 | 7.56 | 2.56±0.05 | 3,883 | 2,060 | 705 | |

| HRT-4 | 7.24 | 2.77±0.34 | 6,325 | 1,458 | 613 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).