1. Introduction

Selenium (Se) is an essential micronutrient for animals and humans and is involved in the function of the catalytic center of different selenoproteins [

1]. Several studies have reported that Se has antioxidant effects [

2,

3], which can be related to immune functions and anticancer properties [

4]. It is a natural element found worldwide in soils [

5]. However, Se deficiency in the population occurs when the concentration of this mineral in the soil is low, and consequently, the plants exhibit reduced accumulation. It is estimated that more than a billion people in the world suffer Se deficiency [

6]. Thus, vegetable crops enriched with Se from various species are receiving significant research interest [

5,

7,

8,

9]. In this situation, Se biofortification in brassica species such as kohlrabi (

Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes), white cabbage (

Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata), red cabbage (

Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. rubra), savoy cabbage (

Brassica oleracea L. var. sabauda), cauliflower (

Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) and broccoli (

Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) is an effective strategy for increasing the intake of Se by humans without exceeding the maximum tolerable intake (400 μg Se day

-1) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Therefore, some studies have reported the foliar application of Se in broccoli plants to achieve a commercial production of Se-enriched broccoli under field conditions [

13,

15,

16,

17]. In a previous study, it was demonstrated that foliar application of Se to broccoli plants is an effective and efficient strategy for obtaining plant products (broccoli heads) that could be good sources of Se and should not represent a risk of toxicity for human consumption. We also demonstrate that, the level of Se was greater in leaves than in the head after Se application, indicating the potential value of this agricultural biomass [

13].

Broccoli by-products, particularly leaves, represent an underutilized resource with significant potential for valorization in sustainable agricultural and industrial practices. Broccoli heads constitute less than 25% of the plant's total aboveground biomass, leaving substantial crop residues such as leaves and stems [

19,

20,

21]. These by-products pose significant challenges to global agricultural efficiency, as they represent considerable waste with potential negative environmental impacts [

19,

22]. However, reducing agricultural biomass waste is essential for fostering sustainability and supporting the transition to a circular economy. The recovery and valorization of these residues offer promising solutions to mitigate waste [

20], with recent advancements emphasizing their transformation into valuable products such as biofuels, bioplastics, and functional materials, thereby reducing dependence on finite resources and mitigating environmental pollution [

23]. Broccoli leaves, for instance, have been identified as rich sources of bioactive compounds, including glucosinolates, phenolics, and antioxidants, which can be utilized in functional food formulations [

19,

20,

24]. Additionally, these by-products have shown promise as plant growth promoters and raw materials for bio-based antimicrobials targeting plant pathogens [

21,

22,

23,

24]. The development of a biomass economy has further highlighted the potential to convert agricultural by-products into economically viable solutions, such as energy production, bioactive chemicals, and biodegradable materials, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and minimizing landfilling [

25,

26,

27]. Innovative approaches such as bioprocessing and biofortification further enhance the value of broccoli residues, contributing to more sustainable and circular agricultural systems while creating new economic opportunities [

28,

29,

30].

The present study aims to evaluate the impact of selenium biofortification, focusing on the application of two different Se forms (selenite and selenate) at concentrations of 1 mM and 2 mM, as a strategy to enhance both the nutritional value and functional properties of broccoli leaves. Selenium biofortification was investigated for its ability to increase Se content, improve antioxidant capacity, and elevate phenolic compounds and soluble protein levels, thereby enhancing the nutraceutical quality of these by-products. The study also explores the antifungal activity of Se-enriched broccoli leaf extracts against Fusarium solani, attributed to Se-induced modulation of phytohormones, including methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid. By addressing global Se deficiencies and promoting environmental sustainability through the valorization of agricultural residues, this work highlights the dual benefits of Se biofortification for improving human health and supporting sustainable agricultural practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Broccoli seeds [Brassica oleracea var. italica ´Belstar´ F1 (Bejo Zaden B.V.)] were sown in multicell trays and then grown in a greenhouse at the Experimental Field of Intensive and Forestry Crops of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences of the Universidad Nacional del Litoral (Esperanza, Santa Fe, Argentina). After four weeks of growth, seedlings of the same size were selected to improve plant uniformity. The seedlings were transplanted into 15 l pots with a substrate composed of GrowMix® Multipro (Terrafertil, Argentina) and were watered periodically with 50% Hoagland solution. Pots were placed 0.6 m from each other in rows spaced at 0.7 m, obtaining a plant density of 2.4 plants m-2. Plants were placed on three subplots (49 plants per subplot), where a completely randomized plot design was applied. In each subplot, edge effects were considered. Broccoli plants were grown for 90 days in a greenhouse under semi controlled conditions with 76% relative humidity, an average temperature of 27/16 °C (day/night) and a PAR solar radiation of 800 µmol m-2 s-1.

2.2. Foliar Application of Selenium

Foliar application of Se was carried out following the methods of Muñoz et al. [

13] and Trod et al. [

31]. Briefly, at the onset of head formation (main stage 41 of plant development of harvestable vegetative parts, according to the BBCH phenological scale, equivalent to 68 days after transplanting, DAT), each plant was sprayed with approximately 10 ml of solutions containing 0, 0.5, and 1 mM of selenate or selenite (Na

2SeO

4, Na

2SeO

3; Sigma-Aldrich). During spraying, 0.1% Rizospray Extremo

® (Rizobacter, Argentina) was used as an adjuvant to facilitate foliar penetration of Se. The application of Se was repeated after 10 days (main stage 43) to reach a final concentration applied of 0, 1, and 2 mM. Distilled water in the presence of the adjuvant was used for treatments without Se supply (control). Control plants were separated physically with plastic foil to avoid cross-contamination during spraying.

Plants were harvested 90 DAT at commercial maturity (when the heads reached their maximum size and presented green and compact flower buds) and were immediately transported to the laboratory in a cold storage cabinet on ice to preserve their freshness. The different analyses on the heads (fresh weight, firmness and diameter) were performed within 3 h postharvest.

2.3. Morphological and Physiological Parameters

Plant height (PH), plant leaf area (LA), and the plant chlorophyll index (CI) were measured at 78, 85, and 90 DAT. Three plants randomly selected per treatment were measured from the ground line to the apical meristem.

The PH values were measured with a ruler. After that, Plant Relatives Elongation Rate (PRER) were calculated. To estimate the PRER, height measurements were transformed into natural logarithms and plotted against the DAT. A linear regression fitting in the interval comprising the days of measurements was performed, and the slopes were considered to be PRER estimates [

32].

The estimation of LA per plant was performed following the allometric Equation (1) described by Céccoli et al. [

32]:

where L and W are the length and width of the central leaflet of each leaf (cm), respectively; F is the allometric factor (0.615) calculated from leaf samples (n = 100); and n is the number of leaves per plant.

The CI was measured with a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Minolta Camera Company).

At harvest, the main broccoli heads were cut off, leaving a 5 cm long stem. The heads, leaves, and stems were weighed, and fresh weights were recorded. Then, the broccoli tissues were dried at 65 °C until reaching constant weight to calculate the dry weight.

Surface firmness measurements on each head were conducted at three different positions using a digital Turoni durometer with a spherical tip (model 53215TT; T.R. Turoni®, Forli, Italy). The average values obtained are expressed in shore firmness units.

Head diameter measurements were taken with a digital caliper on two opposite sides in the equatorial zone on each head. The average values are reported in millimeters.

2.4. Biochemical Parameters

2.4.1. Soluble Protein Content

The extract was prepared by grinding 0.3 g of frozen broccoli leaves with liquid nitrogen in a chilled grinder, followed by the addition of 1 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7). The sample was recovered and centrifuged at 16,090 x g for 20 min at 4 °C (Thermo Scientific Sorvall ST16R, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The supernatant was placed in 2 ml Eppendorf tubes, and the precipitate was discarded. The soluble protein content in the supernatant was determined by the Bradford method [

33]. The results are expressed as mg of soluble protein g

-1 of tissue dry weight (DW). All the measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4.2. GSH-Px Activity

The antioxidant activity of the enzyme glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) was measured using extracts obtained from frozen leaf tissues through the technique described by Paglia and Valentine [

34]. The absorbance of the samples was determined at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer. The activity of the GSH-Px enzyme was expressed as U g

-1 of tissue DW and calculated using the following Equation (2):

where F is a constant used to convert the absorbance per minute (ΔA min

-1) to enzyme units (U). The F was calculated using the following Equation (3):

where RV is the reaction volume (in ml), SV is the volume of the sample (in ml), 5 is the volume (in ml) used to dilute 1 g of tissue during enzymatic extraction, and 6.22 is the NADPH molar extinction coefficient (in mM cm

-1). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4.3. Total Phenolic Compound

The total phenolic compound content was evaluated using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent by spectrophotometry at 760 nm, as described by Lemoine et al. [

35]. This value was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent g

-1 of tissue DW. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4.4. Evaluation of Total Antioxidant Capacity

To estimate the antioxidant properties of Se-treated broccoli leaves, the total antioxidant potential of the extracts was determined by a free radical scavenging technique using the ABTS reagent (2,2´-azino-bis-3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), as described by Kusznierewicz et al. [

36]. The antioxidant capacity was expressed as mg ascorbic acid equivalent g

-1 of tissue DW, and the total measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.4.5. Extraction, Purification, and Quantification of Endogenous Leaves Hormones

The endogenous plant hormones were extracted and purified following the method by Llugany et al. [

37] with some modifications. Briefly, 250 mg of fresh material was milled in an ice-cold mortar with 750 μl extraction solution constituted by MeOH: 2-Propanol: HOAc (20:79:1 by vol.). Then, the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 1000 x g for 5 min at 4 ℃. These steps were repeated two more times and pooled supernatants were lyophilized. Finally, samples were dissolved in 250 μl pure MeOH and filtered with a Spin-X centrifuge tube filter of 0.22 μm cellulose acetate (Costar, Corning Incorporated, New York, USA). Hormone quantification was done using a standard addition calibration curve spiking control plant samples with the standard solutions of Salicylic acid (SA), (±)-Jasmonic acid (JA), Methyl Jasmonate (MJA), (+)-cis,trans-Abscisic acid (ABA), 3-Indoleacetic Acid (IAA) and Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) ranging from 5 to 250 ppb and extracting as described above. Deuterated hormones Jasmonic-2,4,4-d3-(acetyl-2,2-d2) acid (JA-d3) and Salicylic acid-d6 (SA-d6) at 30 ppb and 300 ppb respectively, were used as internal standards in all the samples and standards measurements. All standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich

® (Spain). Plant hormones were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS system in multiple reaction monitoring mode (MRM) according to Segarra et al. [

38]. First hormones were separated using HPLC Acquity (Waters, USA) on a Luna Omega 1.6 µm C18 100ª 50 x 2.1 mm (Phenomenex

®) at 50 °C at a constant flow rate of 0.8 ml min

-1 and 10 µl injected volume. The elution gradient was carried out with a binary solvent system consisting of 0,1% of formic acid in methanol (solvent A) and 0,1% formic acid in milliQ H

2O (solvent B) with the following proportions (v/v) of solvent A [t (min), %A]: (0, 2), (0.2, 2), (1.6, 100), (2, 100), (2.1, 2) and (3, 2). MS/MS experiments were performed on an ABI 4000 Qtrap mass spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer Sciex, Concord). All the analyses were performed using the Turbo Ionspray source in negative ion mode except for MJA and ACC.

2.4.6. Total Se and Mineral Elements Determination

Total concentrations of Se, potassium (K), phosphorus (P), boron (B), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu) or nickel (Ni), Ca (calcium), Mg (magnesium), S (sulfur), Fe (iron), Mn (manganese) and Mo (molybdenum) were analysed by Inducted Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Prior to analysis, 300 mg of lyophilized tissue (leaves) were acid digested with 10 ml of a mixture of HNO3/H2O2 (7:3, v/v) in a closed vessel of HP500 PFA at 180 °C and 1.9 atm for 45 min using a microwave digestion system (Mars 5, CEM, USA). The digested samples were filtered using 0.22 μm syringe filters and diluted until 3% HNO3. The samples were analyzed using an Agilent 7900 ICP-MS system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). The element S was measured by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES, Agilent 5900, USA). The mineral concentration was calculated based on DW and then converted to values based on fresh weight to calculate the recommended daily allowance (RDA, %).

2.5. Preparation of Broccoli Leaf Aqueous Extracts

Nine grams of lyophilized broccoli leaf powder were homogenized in 60 ml of ice-cold distilled water using an immersion blender (SL-SM6038WPN 600W, Smartlife, Buenos Aires, Argentina) through six pulses of 30 sec each. The homogenate was filtered through a muslin cloth and subjected to centrifugation at 16,090 x g for 20 min at 4 °C (Thermo Scientific Sorvall ST16R, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove insoluble debris. This step was repeated to ensure complete clarification. The final volume of the extract was adjusted with distilled water to obtain a stock solution with a concentration of 30% (w/v). The prepared extracts were aliquoted and stored at -20 °C until further use.

2.6. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Aqueous Extracts on the Growth Inhibition of Fusarium solani

To assess the impact of broccoli leaf aqueous extracts on the growth of

Fusarium solani f. sp.

eumartii isolate 3122 (EEA-INTA, Balcarce, Argentina),

in vitro bioassays were performed following the protocol described by Guevara et al. [

39], with some modifications. Briefly, 10 μl of a spore suspension (3 × 10⁵ spores ml⁻¹ in distilled water) were mixed with 40 μl of each broccoli leaf extract or distilled water (control), supplemented with 30% sucrose (w/v). The mixtures were incubated in darkness at 18 °C for 20 h. Following incubation, samples were observed using bright-field microscopy at 40× magnification with a Nikon Eclipse E200 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Hyphal and spore lengths were measured using ImageJ software [

40]. Three independent experiments were conducted, and the hyphal growth index was calculated as the ratio between the average hyphal length and spore length.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were statistically analyzed using InfoStat statistical software version 2017 [

41]. The significance of the difference among the mean values was determined by one or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with subsequent multiple comparisons of means by the least significant difference (LSD) test. Two-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate the effects of foliar Se application and the growth time (Treatment x DAT) on the evolution of morphological parameters (PH and LA). Correct application of ANOVA was checked by residual normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilks Test, QQ plots) and homoscedasticity (Levene test, residual plots). Differences at

P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard error.

To obtain an appropriate interpretation of the variable correlation and its relative weight on the results, a multivariate analysis was performed. Thus, principal component analysis (PCA), biplot analysis and minimum spanning tree (MST) analysis were performed. The quality of the PCA was analyzed by considering the cophenetic correlation coefficient (CCC) value.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Changes in Morphological and Physiological Parameters During the Growth Stages of Broccoli Plants

In the present study, the effect of foliar Se application on various growth parameters of broccoli plants was evaluated. As shown in

Table 1, Se treatments did not affect plant height (PH) at 78, 85, or 90 days after transplanting (DAT). This suggests that plant height remains unchanged by Se application from 15 days post-treatment until harvest (90 DAT).

On the other hand, leaves represent one of the main plant organs, contributing significantly to green biomass and playing a central role in photosynthesis by converting solar radiation into chemical energy [

42]. The leaf area (LA) parameter showed no significant differences between treatments at 78 DAT. Similarly, at 85 DAT, no statistically significant variations were observed in LA among the different treatments (

Table 1).

At harvest time, LA maintained its growth trend without exhibiting significant differences among the treatments. The importance of LA in broccoli and other plant species lies in the fact that during the transition from the vegetative to the reproductive phase, the young leaves that sank for photoassimilates became fully developed organs. Photoassimilates are subsequently sent to reproductive organs during formation, where they become sources of photoassimilates for the accumulation of dry matter [

43,

44,

45].

Broccoli leaves are generally wider at the apex than at the base, a property that increases the interception of solar radiation because the leaves are more widely distributed around the stem. The maximum values of LA occurred at 90 DAT (end of the growth cycle analyzed), coinciding with what was reported by Lindemann-Zutz et al. [

45] and Francescangeli et al. [

43].

The plant relative elongation rate (PRER) is an easy parameter to measure and provides relevant information on changes in plant growth [

36]. The foliar application of Se did not modify PRER (

Table 2).

The chlorophyll index (CI) is a parameter that indirectly measure leaf chlorophyll content [

46]. It is a useful tool for detecting nutrient deficiencies or other stresses that can limit plant growth and productivity [

42]. In the present study, no significant differences in the CI were observed between the Se treatments across different growing days (data not shown). This finding aligns with the results reported by Muñoz et al. [

13], who analyzed two broccoli cultivars (‘Belstar’ and ‘Legend’) grown under field conditions, suggesting that Se-treated plants and those grown in pots were not subjected to stress. However, these results contrast with those of Palencia et al. [

47], who observed that Se application in strawberry plants resulted in older leaves remaining greener compared to control plants. The lack of significant changes in CI in our study may be attributed to the fact that the plants were harvested at commercial maturity of the heads, rather than at physiological maturity, which could explain the absence of noticeable effects from Se treatment on leaf greenness.

3.2. Effect of Foliar Selenium Application on Biomass Distribution, Fresh Weight, Firmness, and Diameter of Broccoli Heads

The foliar application of Se significantly influenced several morphological and physiological parameters in broccoli plants. Both selenate and selenite treatments increased the fresh weight (FW) of broccoli heads. Specifically, 1 mM selenate resulted in a 133% increase in FW, while 2 mM selenate and both 1 mM and 2 mM selenite treatments produced a 98% increase compared to the control (

Figure 1AS). These findings contrast with Sindelarova et al. [

17], who reported no significant changes in head FW across various broccoli cultivars ('Heraklion', 'Marathon', 'Parthenon', and 'Naxos') after Se application. However, in the 'Belstar' cultivar analyzed here, the Se treatments positively affected FW, likely by enhancing the water content of the heads, as previously suggested by Muñoz et al. [

13]. This indicates that the response to Se treatments is cultivar-dependent and highlights the potential of Se biofortification to improve consumable yield.

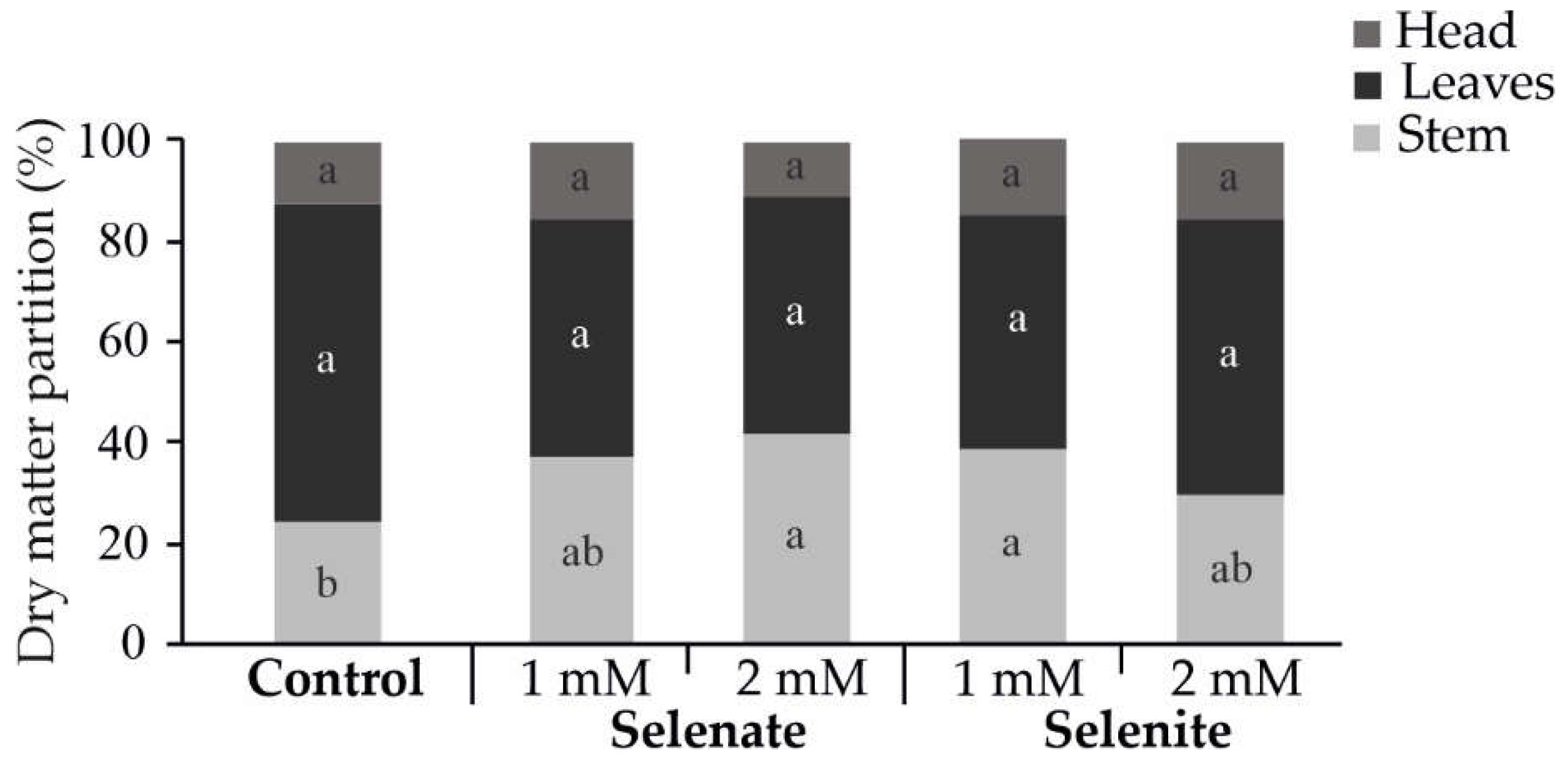

In terms of biomass partitioning, dry weight (DW) analysis revealed that Se treatments generally did not alter the dry matter content of leaves or heads, except for a significant increase in stem DW in plants treated with 2 mM selenate and 1 mM selenite (

Figure 1). This finding aligns with Muñoz et al. [

13], who observed no significant changes in the dry weight of broccoli heads following foliar Se application, despite notable increases in FW. Such effects have been attributed to enhanced water use efficiency (WUE), primarily due to reduced transpiration rates rather than increased photosynthetic activity, as suggested by Muñoz et al. [

13].

Head firmness (HF), a critical parameter for commercial quality, was unaffected by Se treatments regardless of dose or salt type (

Figure 1BS). Similarly, head diameter (HD) showed no significant variation across treatments, except for a slight increase under 1 mM selenite (

Figure 1CS). These results corroborate previous reports, which found minimal effects of Se application on head diameter in other broccoli cultivars ('Legend', 'Formoso' and 'Legacy') [

13,

18,

31]. Ghasemi et al. [

15] also reported negligible impacts of Se on this parameter, further supporting our findings.

Based on these results, foliar Se application significantly enhances broccoli head FW -primarily by increasing water content- without substantially affecting dry matter content, head firmness, or diameter under the tested conditions. This underscores the commercial advantage of Se biofortification, which improves yield without compromising marketable quality.

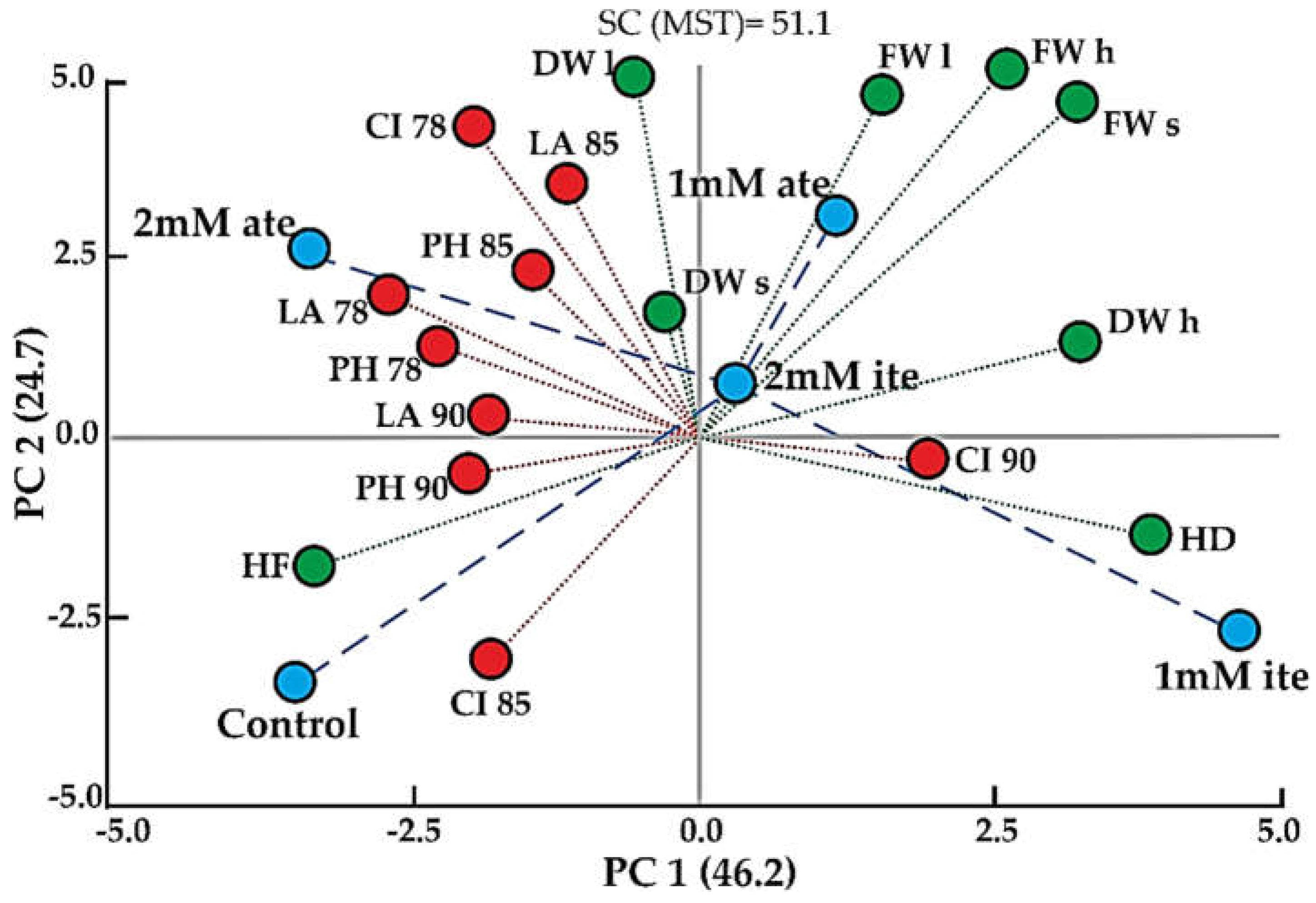

3.3. Principal Component Analysis of Selenium Treatments on Growth, Morphological, and Yield Parameters in 'Belstar' Broccoli

The PCA biplot for the broccoli 'Belstar' cultivar (

Figure 2) reveals the distribution of growth, morphological, and yield parameters in response to the various Se treatments. Principal components 1 (PC1) and 2 (PC2) together account for 70.9% of the total variation, with PC1 explaining 46.2% and PC2 accounting for 24.7%. The high sum of squares (SC) value of 51.1, a value of 0.986 for CCC, and the distinct separation of the treatments confirm the effectiveness of the multivariate analysis in discriminating between the different Se treatments.

A positive correlation was observed between yield-related parameters such as head fresh weight (FW h), stem fresh weight (FW s), leaf fresh weight (FW l), and head dry weight (DW h), which are located toward the right side along PC1. These parameters showed a strong relationship with higher yields. Additionally, HD is positively associated with these parameters, supporting its role as a marker of higher yield in 'Belstar'.

In contrast, early growth parameters, including LA at 78, 85, and 90 DAT, PH at 78, 85, and 90 DAT, and CI at 85 and 90 DAT, were negatively correlated with yield parameters. These early growth markers are located to the left of PC1 and partially along PC2. This suggests that larger leaf area and plant height, typically associated with early vegetative growth, are inversely related to yield parameters in this cultivar. Head firmness also aligns with these early growth parameters, indicating a negative relationship with the final yield.

The PCA results highlight that the most significant treatment for 'Belstar' was the application of 1 mM selenite, followed by 2 mM selenite, which led to increased head fresh weight and other yield-related parameters. Conversely, the control treatment and 2 mM selenate were the least effective, as they showed minimal impact on the evaluated parameters, especially head fresh weight. These results align with the treatment rankings derived from the PCA, where 1 mM selenite resulted in the highest head fresh weight, confirming the positive effect of this treatment on 'Belstar'.

In conclusion, the PCA clearly demonstrates that Se treatments, particularly 1 and 2 mM selenite, positively affect the yield of 'Belstar' by influencing parameters such as head fresh weight and head diameter. This suggests that the foliar application of Se can enhance broccoli yield, although the specific effects vary depending on the treatment.

Considering the previous report by Muñoz et al. [

13], which demonstrated that Se accumulation in broccoli heads is dose-dependent, and the significant positive influence of the 2 mM Se dose on the evaluated parameters, we decided to analyze the effect of this dose on the nutraceutical parameters and plant hormone content in the leaves, as detailed below.

3.4. Selenium Improves Nutraceutical Parameters in Broccoli by-Products

3.4.1. Biochemical Parameters

Broccoli by-products can be used as functional food ingredients in the food industry because of their nutritional qualities [

19,

20,

48,

49]. In the present study, the leaves that remained as remnants of plants after the harvest of heads were considered by-products.

Among the parameters of nutritional quality, the level of antioxidants is the most interesting since it plays a critical role in human health because it is able to prevent oxidative damage to molecules and different cellular components [

22]. The total antioxidant capacity significantly increased when the plants were treated with 2 mM selenate compared to that of the control. However, no significant changes were observed when the plants were treated with 2 mM selenite (

Table 3).

In this study, the antioxidant capacity of leaves was also assessed through both enzymatic systems, such as glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and non-enzymatic systems including phenolic compounds. Neither of the Se salt treatments resulted in significant changes in GSH-Px activity compared to the control (

Table 3). However, the concentration of phenolic compounds in Se-treated broccoli leaves was significantly higher than in control leaves, regardless of the Se salt applied (

Table 3). A strong positive correlation (r = 0.7899) was observed between total antioxidant activity and phenolic compound content, which is consistent with the findings of Hwang and Lim [

22], who reported a correlation coefficient of 0.880 for broccoli by-products. Likewise, Domínguez-Perles et al. [

19] demonstrated a strong relationship between total phenolic content in broccoli heads and DPPH radical scavenging activity.

The enhancement of the antioxidant status in broccoli leaves following Se treatment observed in this study aligns with the findings of Bouranis et al. [

48] and Martirosyan et al. [

49], further emphasizing the synergistic relationship between Se and other inherent antioxidants. Although Se is not considered essential for plants, low concentrations of Se are known to boost antioxidant defense mechanisms in crops [

46]. The increase in phenolic compound levels in the leaves resulting from Se application underscores the nutritional value of the by-products. Among natural antioxidants, phenolic compounds are particularly potent [

50], and agricultural products with high polyphenol content have the potential to reduce the risks associated with oxidative stress, such as cancer, inflammation, cardiovascular diseases, and premature aging [

50].

Furthermore, Se treatments significantly elevated the content of soluble proteins in the leaves (

Table 3). Foliar application of 2 mM selenate and 2 mM selenite increased soluble protein content by 186% and 60%, respectively, compared to the control. This increase in soluble protein content in broccoli leaves facilitated by Se, adds further nutritional value to the by-products, enhancing their potential as a source of high-quality functional ingredients.

3.4.2. Foliar Application of Selenium Increases the Mineral Content of Broccoli by-Products

The ash content in leaves is commonly higher than the ash content in other plant tissues of the same species, so broccoli leaves might be a better source of minerals than the head or the stem [

48]. In addition, understanding the relationships of Se with other elements in plants is important for producing functional foods with high Se contents through the use of by-products. The foliar application of Se did not significantly change the mineral concentrations of K, P, B, Zn, Cu or Ni in broccoli leaves (

Table 4), similar to the findings of Golubkina et al. [

14] for different Brassicaceae crops.

Nevertheless, the Se concentration in the leaves significantly increased after foliar application of both Se salts (100-fold higher for 2 mM selenate and 150-fold higher for 2 mM selenite) compared with the control. Similarly, Sindelarova et al. [

17] reported that foliar application of 50 g ha

-1 selenate (equal to 1 mM) significantly increased the total Se content in broccoli leaves by 32.5-fold. Additionally, Li et al. [

51] reported Se concentrations in leaves ranging between 1.4 and 3.9 μg g

-1 DW (without Se), values even higher than those found in the control leaves of the present study but lower than those obtained in plant leaves treated with 2 mM selenite and selenate.

Similarly, the foliar concentrations of Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Mn and Mo were significantly modified by Se treatment compared to those in the control leaves (

Table 4). Treatment with selenite significantly increased the contents of all these elements; however, treatment with selenate only induced increases in S and Fe. The concentration values obtained here are within the same order of magnitude as those previously reported for other broccoli cultivars [

20]. Considering these values, the recommended daily allowance (RDA, %) was calculated for selenite-treated leaves based on fresh tissue (100 g) according to Liu et al. [

20]. The RDA of Fe (4.9%), Zn (4.42%), Mn (44%), Ca (31.86%), S (11.8%), and Mg (14.7%) was significantly greater than that of the controls. In this way, it was shown that foliar application of Se not only increases the content of this essential element but also improves the nutritional quality of broccoli by-products through the accumulation of other beneficial mineral elements for human health.

3.5. Differential Effects of Selenate and Selenite on Phytohormone Regulation in Broccoli Leaves: Balancing Growth and Defense Responses

The application of Se treatments significantly affected the concentrations of phytohormones in broccoli leaves, as outlined in

Table 5. Specifically, MJA levels increased notably under both selenate and selenite treatments compared to the control. This elevation suggests that Se may enhance plant defense mechanisms, as MJA plays a critical role in stress and defense signaling pathways [

52]. In contrast, JA levels decreased under selenate treatment relative to the control, while selenite treatment resulted in intermediate levels. The reduction in JA may reflect the complex regulatory role of Se in modulating jasmonate pathways, potentially balancing plant growth and defense responses [

53].

Salicylic acid concentrations exhibited a significant increase under selenite treatment compared to both the control and selenate treatments. Elevated SA levels are often associated with enhanced systemic acquired resistance and improved pathogen defense [

52]. The substantial increase in SA under selenite suggests that this form of Se may be particularly effective in activating SA-mediated defense pathways.

Indole-3-acetic acid levels were significantly elevated under selenate treatment compared to both the control and selenite treatments. Indole-3-acetic acid, a critical hormone for cell elongation and division, indicates that selenate may promote vegetative growth and development under non-toxic Se concentrations [

53]. Abscisic acid concentrations also varied significantly, with a marked increase under selenate treatment compared to both the control and selenite treatments. Abscisic acid is a key hormone in abiotic stress responses, such as drought and salinity tolerance, and the elevated ABA levels under selenate suggest an enhanced capacity for stress mitigation [

52].

On the other hand, levels of ACC, a precursor of ethylene, a hormone involved in stress responses and senescence, were lower under selenite treatment compared to both the control and selenate treatments. This reduction suggests that selenite may suppress ethylene biosynthesis, potentially alleviating stress-induced growth inhibition [

53].

For instance, the increase in MJA and SA levels under selenite treatment could enhance the plant's defense systems, aligning with the findings of Cheng et al. [

52], who reported that Se can bolster plant defense mechanisms through hormonal regulation. Additionally, the rise in IAA and ABA under selenate treatment supports the notion that Se can promote growth and stress tolerance, as discussed by Maslennikov et al. [

53], who emphasized Se's role in regulating secondary metabolism and stress adaptation in plants. Moreover, the differential effects of selenate and selenite on hormone levels underscore the importance of Se speciation in determining its physiological impacts. While selenate appears to enhance growth-related hormones (IAA and ABA), selenite predominantly affects defense-related hormones (MJA and SA). This distinction is critical for optimizing Se supplementation strategies in agricultural practices to effectively balance growth and defense responses.

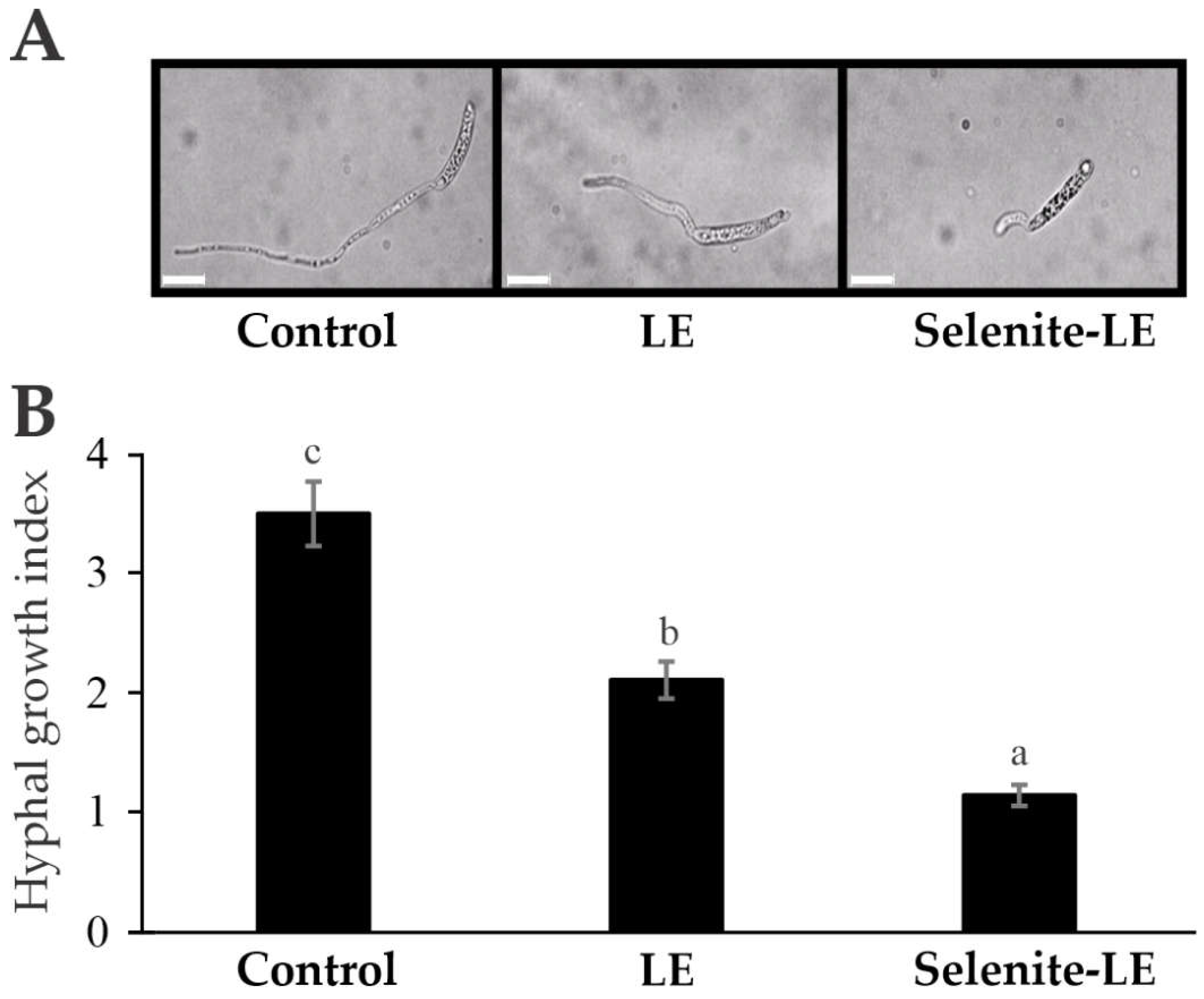

3.6. Antifungal Potential of Selenium-Biofortified Broccoli Leaf Extracts Against Fusarium solani

Building upon the previously obtained hormonal analysis of broccoli leaves (

Table 5), which is associated with plant defense mechanisms, the antifungal potential of aqueous extracts from untreated and 2 mM selenite-treated broccoli leaves was investigated (

Figure 3). The results obtained demonstrate that both treatments, leaf extract (LE) and selenite-treated leaf extract (Selenite-LE), significantly inhibited the hyphal growth of

Fusarium solani compared to the control. LE, which corresponds to an aqueous extract of untreated broccoli leaves, showed approximately 40% inhibition of fungal growth relative to the control. In contrast, Selenite-LE, derived from 2 mM selenite-treated broccoli leaves, exhibited a more pronounced inhibitory effect, with growth inhibition of around 67.5% compared to the control.

When comparing these results with those of Hanson et al. [

54], Se appears to play a protective role against

Fusarium infection. Their study found that

Brassica juncea seedlings treated with Se and infected with

Fusarium spore suspension showed less biomass loss than untreated seedlings, despite both groups exhibiting infection symptoms. Moreover,

Fusarium growth was inhibited at high Se concentrations, suggesting that Se might directly hinder fungal development. This observation aligns with the inhibition observed in our study, further supporting the hypothesis that Se enhances the antifungal properties of the extract.

These findings indicate that aqueous extracts from Se-treated broccoli leaves have a significantly stronger inhibitory effect on hyphal growth than extracts from untreated broccoli leaves. This enhanced antifungal activity is likely due to the role of Se in boosting the extract's antifungal properties.

4. Conclusions

The present study underscores the significant nutritional and antimicrobial potential of Se biofortification in broccoli, particularly through the application of 2 mM selenite. This strategy proves highly effective in enhancing both the nutritional value and functional properties of broccoli by-products. The results show that Se biofortification not only increases the Se content but also improves the antioxidant capacity, phenolic compound levels, and soluble protein content in broccoli leaves. Furthermore, Se treatments significantly enriched essential mineral elements such as calcium, magnesium, sulfur, and iron, thereby further elevating the nutraceutical quality of these by-products. The observed antifungal activity of Se-enriched broccoli leaf extracts against Fusarium solani highlights their promising application as natural biopesticides, facilitated by the modulation of key phytohormones such as methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid. This dual functionality of Se-biofortified broccoli emphasizes its potential in enhancing human health through improved nutritional profiles while simultaneously contributing to sustainable agricultural practices by valorizing crop residues. These findings reinforce the importance of Se biofortification as a dual-benefit strategy: addressing global Se deficiencies and promoting environmental sustainability. They support the adoption of Se biofortification as an innovative agronomic and industrial approach. Future research should focus on further integrating Se-enriched by-products into functional food formulations and agricultural applications to maximize their health-promoting and environmentally sustainable benefits.

Author Contributions

M.S.B., B.S.T and M.M.S. investigation and formal analysis. M.S. and V.T. investigation. C.A.B. investigation and supervision. A.A.P. writing - original draft. M.L. and M.J.S.M. investigation, supervision, writing - review & editing. M.G.G. supervision, writing - review & editing. L.D.D. conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing - original draft. G.C. conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing - original draft. F.F.M. conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, writing - original draft.

Funding

This research was funded by AGENCIA NACIONAL DE PROMOCIÓN DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN, EL DESARROLLO TECNOLÓGICO Y LA INNOVACIÓN, grant number PICT-2015-0142 and CONSEJO NACIONAL DE INVESTIGACIONES CIENTÍFICAS Y TÉCNICAS DE LA REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA, grant number PIP 2021-2023 11220200100488CO and UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL LITORAL, grant number CAI+D2020 50520190100151LI.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Se4All project funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101007630. The assistance of Carla Borghese, Gabriela Ochoa and Mauro Alisio is gratefully appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the present work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be considered a potential conflict of interest. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Hariharan, S.; Dharmaraj, S. Selenium and selenoproteins: it’s role in regulation of inflammation. Inflammo Pharmacol. 2020, 28, 667–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, J.C.; Hoffmann, P.R. Selenium, Selenoproteins, and Immunity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinggi, U. Selenium: its role as antioxidant in human health. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2008, 13, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Shanaida, M.; Lysiuk, R.; Antonyak, H.; Klishch, I.; Shanaida, V.; Peana, M. Selenium: An Antioxidant with a Critical Role in Anti-Aging. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galić, L.; Vinković, T.; Ravnjak, B.; Lončarić, Z. Agronomic Biofortification of Significant Cereal Crops with Selenium—A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R.; Waterland, N.; Moon, Y.; Tou, J.C. Selenium Biofortification of Agricultural Crops and Effects on Plant Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds Important for Human Health and Disease Prevention – a Review. Plant Foods for Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos, G.S.; Lin, Z.-Q.; Broadley, M. Selenium Biofortification. In Selenium in plants: Molecular, Physiological, Ecological and Evolutionary Aspects, Pilon-Smits, E.A.H., Winkel, L.H.E., Lin, Z.-Q., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Poblaciones, M.J.; Broadley, M.R. Foliar selenium biofortification of broccolini: effects on plant growth and mineral accumulation. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirana, M.A.; Boada, R.; Xiao, T.; Llugany, M.; Valiente, M. Direct and indirect selenium speciation in biofortified wheat: A tale of two techniques. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e13843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos, G.S.; Arroyo, I.; Pickering, I.J.; Yang, S.I.; Freeman, J.L. Selenium biofortification of broccoli and carrots grown in soil amended with Se-enriched hyperaccumulator Stanleya pinnata. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bañuelos, G.S.; Arroyo, I.S.; Dangi, S.R.; Zambrano, M.C. Continued Selenium Biofortification of Carrots and Broccoli Grown in Soils Once Amended with Se-enriched S. pinnata. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amato, R.; Regni, L.; Falcinelli, B.; Mattioli, S.; Benincasa, P.; Dal Bosco, A.; Pacheco, P.; Proietti, P.; Troni, E.; Santi, C.; et al. Current Knowledge on Selenium Biofortification to Improve the Nutraceutical Profile of Food: A Comprehensive Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 4075–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, F.F.; Stoffel, M.M.; Céccoli, G.; Trod, B.S.; Daurelio, L.D.; Bouzo, C.A.; Guevara, M.G. Improving the foliar biofortification of broccoli with selenium without commercial quality losses. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 4218–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.; Antoshkina, M.; Bondareva, L.; Sekara, A.; Campagna, E.; Caruso, G. Effect of Foliar Application of Sodium Selenate on Mineral Relationships in Brassicaceae Crops. Hortic. 2023, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, Y.; Ghasemi, K.; Pirdashti, H.; Asgharzadeh, R. Effect of selenium enrichment on the growth, photosynthesis and mineral nutrition of broccoli. Not. Sci. Biol. 2016, 8, 109–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.C.; Wirtz, M.; Heppel, S.C.; Bogs, J.; Krämer, U.; Khan, M.S.; Bub, A.; Hell, R.; Rausch, T. (2011). Generation of Se-fortified broccoli as functional food: Impact of Se fertilization on S metabolism. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindelarova, K.; Szakova, J.; Tremlova, J.; Mestek, O.; Praus, L.; Kana, A.; Najmanova, J.; Tlustos, P. The response of broccoli (Brassica oleracea convar. italica) varieties on foliar application of selenium: uptake, translocation, and speciation. Food Addit. Contam. Part A, Chemistry, analysis, control, exposure & risk assessment 2015, 32, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, L.; Tálamo, A.; Laura, A.; J, F.; C, A. Evaluación de dos híbridos de brócoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica). Horticultura 2017, 36, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Perles, R.; Martinez-Ballesta, M.C.; Carvajal, M.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A. Broccoli derived by-products a promising source of bioactive ingredients. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Ser, S.L.; Cumming, J.R.; Ku, K.M. Comparative Phytonutrient Analysis of Broccoli By-Products: The Potentials for Broccoli By-Product Utilization. Molecules 2018, 23, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artés-Hernández, F.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Hashemi, S.; Castillejo, N. Genus Brassica By-Products Revalorization with Green Technologies to Fortify Innovative Foods: A Scoping Review. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.H.; Lim, S.B. Antioxidant and anticancer activities of broccoli by-products from different cultivars and maturity stages at harvest. Preventive Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 20, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioso, O. Current and future perspectives for biomass waste management and utilization. Sci. Rep. 9635. [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño, I.; Martín, A.; Casquete, R.; Prieto, M.H.; Ayuso, M.C.; Córdoba, M.G. Evaluation of broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) crop by-products as sources of bioactive compounds. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Hills, C.D.; Singh, R.S.; Atkinson, C.J. Biomass waste utilisation in low-carbon products: harnessing a major potential resource. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1038; 35. [Google Scholar]

- Sadh, P.K.; Chawla, P.; Kumar, S.; Das, A.; Kumar, R.; Bains, A.; Sridhar, K.; Duhan, J.S.; Sharma, M. Recovery of agricultural waste biomass: A path for circular bioeconomy, Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161904, doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161904.

- Zhou, C.; Wang, Y. Recent progress in the conversion of biomass wastes into functional materials for value-added applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 1080. [Google Scholar]

- Shinali, T.S.; Zhang, Y.; Altaf, M.; Nsabiyeze, A.; Han, Z.; Shi, S.; Shang, N. The Valorization of Wastes and Byproducts from Cruciferous Vegetables: A Review on the Potential Utilization of Cabbage, Cauliflower, and Broccoli Byproducts. Foods 2024, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas-Job, M.C.; Soriano-Melgar, L.A.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Peralta-Rodríguez, R.D.; Rivera-Cabrera, F.; Martínez-Vazquez, D.G. Effect of broccoli fresh residues-based extracts on the postharvest quality of cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 317, 112076, doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112076.

- Eugui, D.; Velasco, P.; Abril-Urías, P.; Escobar, C.; Gómez-Torres, Ó.; Caballero, S.; Poveda, J. Glucosinolate-extracts from residues of conventional and organic cultivated broccoli leaves (Brassica oleracea var. italica) as potential industrially-scalable efficient biopesticides against fungi, oomycetes and plant parasitic nematodes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 200, Part A, 116841, doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116841.

- Trod, B.S.; Buttarelli, M.S.; Stoffel, M.M.; Céccoli, G.; Olivella, L.; Barengo, P.B.; Llugany, M.; Guevara, M.G.; Muñoz, F.F.; Daurelio, L.D. Postharvest commercial quality improvement of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L.) after foliar biofortification with selenium. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céccoli, G.; Seen, M.; Bustos, D.; Ortega, L.I.; Cordoba, A.; Vegetti, A.; Taleisnik, E. Genetic variability for responses to short- and long-term salt stress in vegetative sunflower plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, M.; Chaves, A.R.; Martínez, G. Influence of combined hot air and UV-C treatment on the antioxidant system of minimally processed broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica). LWT-Food Sci. Tech. 2010, 43, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusznierewicz, B.; Bartoszek, A.; Wolska, L.; Drzewiecki, J.; Gorinstein, S.; Namieśnik, J. Partial characterization of white cabbages (Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. alba) from different regions by glucosinolates, bioactive compounds, total antioxidant activities and proteins. LWT - Food Sci. Tech. 2008, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llugany, M.; Martin, S.R.; Barceló, J.; Poschenrieder, C. Endogenous jasmonic and salicylic acids levels in the Cd-hyperaccumulator Noccaea (Thlaspi) praecox exposed to fungal infection and/or mechanical stress. Plant Cell Rep. 1243. [Google Scholar]

- Segarra, G.; Jáuregui, O.; Casanova, E.; Trillas, I. Simultaneous quantitative LC–ESI-MS/MS analyses of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid in crude extracts of Cucumis sativus under biotic stress. Phytochem. 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara, M.G.; Oliva, C.R.; Huarte, M.; Daleo, G.R. An aspartic protease with antimicrobial activity is induced after infection and wounding in intercellular fluids of potato tubers. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1: 131-137, doi.org/10.1023/A, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods, 1038. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rienzo, J.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C. InfoStat. Statistical Software. Grupo Infostat FCA UNC, Córdoba, Argentina. 2017.

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Nie, J.; Yuan, X.; Chen, F. Use of a leaf chlorophyll content index to improve the prediction of above-ground biomass and productivity. PeerJ 2019, 2019, e6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francescangeli, N.; Sangiacomo, M.; Marti, H. Effects of plant density in broccoli on yield and radiation use efficiency. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 110, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sedano, F.; Huang, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, X.; Liang, S.; Tian, L.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.; Wu, W. Assimilating a synthetic Kalman filter leaf area index series into the WOFOST model to improve regional winter wheat yield estimation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 216, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Zutz, K.; Fricke, A.; Stützel, H. Prediction of time to harvest and its variability of broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) part II. Growth model description, parameterisation and field evaluation. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 200, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mogy, M.M.; Mahmoud, A.W.M.; El-Sawy, M.B.I.; Parmar, A. Pre-harvest foliar application of mineral nutrients to retard chlorophyll degradation and preserve bio-active compounds in broccoli. Agronomy, 3390. [Google Scholar]

- Palencia, P.; Martinez, F.; Burducea, M.; Oliveira, J.A.; Giralde, I. Efectos del enriquecimiento con Selenio en spad, calidad de la fruta y parámetros de crecimiento de plantas de fresa en un sistema de cultivo sin suelo. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2016, 38, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouranis, D.L.; Stylianidis, G.P.; Manta, V.; Karousis, E.N.; Tzanaki, A.; Dimitriadi, D.; Bouzas, E.A.; Siyiannis, V.F.; Constantinou-Kokotou, V.; Chorianopoulou, S.N.; et al. Floret Biofortification of Broccoli Using Amino Acids Coupled with Selenium under Different Surfactants: A Case Study of Cultivating Functional Foods. Plants 2023, 12, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martirosyan, V.V.; Kostyuchenko, M.N.; Kryachko, T.I.; Malkina, V.D.; Zhirkova, E.V.; Golubkina, N.A. The Beneficial Effect of Selenium-Enriched Broccoli on the Quality Characteristics of Bread. Processes 2023, 11, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, Y.; Liu, H.Y.; Guo, H.; He, X.Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, D.T.; Mai, Y.H.; Li, H.B.; Zou, L.; et al. Nutritional values, beneficial effects, and food applications of broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica Plenck). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.; Rao, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Y.; Ye, J.; Cheng, S.; Yang, X.; Xu, F. Advances in research on the involvement of selenium in regulating plant ecosystems. Plants 2022, 11, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrypnik, L.; Feduraev, P.; Golovin, A.; Maslennikov, P.; Styran, T.; Antipina, M.; Riabova, A.; Katserov, D. The integral boosting effect of selenium on the secondary metabolism of higher plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, B.; Garifullina, G.F.; Lindblom, S.D.; Wangeline, A.; Ackley, A.; Kramer, K.; Norton, A.P.; Lawrence, C.B; Pilon-Smits, E.A.H. Selenium accumulation protects Brassica juncea from invertebrate herbivory and fungal infection. New Phytol. 1046. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Effect of selenium treatments on the dry matter partitioning of different tissues at harvest. The results are expressed as the means (n = 3) ± standard errors. The means not sharing any letter are significantly different according to the LSD test at the P < 0.05 level of significance.

Figure 1.

Effect of selenium treatments on the dry matter partitioning of different tissues at harvest. The results are expressed as the means (n = 3) ± standard errors. The means not sharing any letter are significantly different according to the LSD test at the P < 0.05 level of significance.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis of broccoli plants grown with foliar application of selenium. Growth parameters measured (red circles): PH, plant height; LA, leaf area; CI, chlorophyll index. DAT: Days after transplant (78, 85, 90). Yield and morphological parameters measured at harvest time (green circles): FW h, head fresh weight; FW s, stem fresh weight; FW l, leaf fresh weight; DW h, head dry weight; DW s, stem dry weight; DW l, leaf dry weight; HF, head firmness; and HD, head diameter. Treatments (blue circles): Control, 0 mM selenium; 1 mM ite, 1 mM selenite; 2 mM ite, 2 mM selenite; 1 mM ate, 1 mM selenate; and 2 mM ate, 2 mM selenate. PC 1: principal component 1. PC 2: principal component 2. SC: sum of squares. MST: minimum spanning tree.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis of broccoli plants grown with foliar application of selenium. Growth parameters measured (red circles): PH, plant height; LA, leaf area; CI, chlorophyll index. DAT: Days after transplant (78, 85, 90). Yield and morphological parameters measured at harvest time (green circles): FW h, head fresh weight; FW s, stem fresh weight; FW l, leaf fresh weight; DW h, head dry weight; DW s, stem dry weight; DW l, leaf dry weight; HF, head firmness; and HD, head diameter. Treatments (blue circles): Control, 0 mM selenium; 1 mM ite, 1 mM selenite; 2 mM ite, 2 mM selenite; 1 mM ate, 1 mM selenate; and 2 mM ate, 2 mM selenate. PC 1: principal component 1. PC 2: principal component 2. SC: sum of squares. MST: minimum spanning tree.

Figure 3.

Effect of broccoli leaf aqueous extracts on F. solani hyphal growth. (A) Spores of F. solani were incubated in the presence of water (Control), aqueous extracts of untreated broccoli leaves (LE), or selenite-treated broccoli leaves (Selenite-LE). After incubation the morphological changes were analyzed by bright field microscopy (40X). White bars 20 μm. (B) The hyphal growth index was calculated as ratio between the average lengths of hyphal and spore. The results are expressed as the means (n = 25) ± standard errors. The means not sharing any letter are significantly different according to the LSD test at the P < 0.05 level of significance.

Figure 3.

Effect of broccoli leaf aqueous extracts on F. solani hyphal growth. (A) Spores of F. solani were incubated in the presence of water (Control), aqueous extracts of untreated broccoli leaves (LE), or selenite-treated broccoli leaves (Selenite-LE). After incubation the morphological changes were analyzed by bright field microscopy (40X). White bars 20 μm. (B) The hyphal growth index was calculated as ratio between the average lengths of hyphal and spore. The results are expressed as the means (n = 25) ± standard errors. The means not sharing any letter are significantly different according to the LSD test at the P < 0.05 level of significance.

Table 1.

Effect of foliar selenium application on the growth parameters (plant height, PH; plant leaf area, LA) of broccoli plants.

Table 1.

Effect of foliar selenium application on the growth parameters (plant height, PH; plant leaf area, LA) of broccoli plants.

| |

PH (cm) |

LA (cm2) |

| Treatment |

Days after transplanting (DAT) |

| 78 |

85 |

90 |

78 |

85 |

90 |

| Control |

15.0 ± 1.5 |

19.3 ± 2.8 |

24.2 ± 3.1 |

99.5 ± 3.9 |

103.0 ± 15.8 |

107.5 ± 11.7 |

| fg |

cdef |

a |

abcd |

abc |

abc |

| Selenate |

13.7 ± 0.9 |

19.5 ± 0.9 |

24.0 ± 1.2 |

95.9 ± 1.3 |

107.17 ± 5.6 |

107.0 ± 6.2 |

| 1 mM |

g |

bcdef |

ab |

bcd |

abc |

abcd |

| Selenate |

15.5 ± 0.3 |

18.5 ± 1.5 |

23.3 ± 2.5 |

102.2 ± 5.1 |

121.5 ± 16.8 |

110.6 ± 22.8 |

| 2 mM |

efg |

def |

abc |

abcd |

ab |

a |

| Selenite |

12.2 ± 0.2 |

16.7 ± 0.3 |

22.3 ± 0.3 |

76.9 ± 5.5 |

102.1 ± 10.7 |

124.6 ± 16.1 |

| 1 mM |

g |

efg |

abcd |

d |

abcd |

abc |

| Selenite |

15.3 ± 0.9 |

19.7 ± 1.5 |

22.2 ± 1.6 |

88.9 ± 7.2 |

103.2 ± 14.6 |

91.7 ± 11.8 |

| 2 mM |

efg |

abcde |

abcd |

cd |

abcd |

cd |

| Treatment x DAT |

|

0.9542 |

|

|

0.9093 |

|

| (P-value) |

Table 2.

Changes in the Plant Relative Elongation Rates (PRER, cm cm-1 d-1) under selenium foliar application treatments.

Table 2.

Changes in the Plant Relative Elongation Rates (PRER, cm cm-1 d-1) under selenium foliar application treatments.

| Treatment |

PRER

(cm cm-1 d-1) |

| Control |

0.91 ± 0.09 ab |

| Selenate 1 mM |

0.86 ± 0.04 ab |

| Selenate 2 mM |

0.79 ± 0.15 ab |

| Selenite 1 mM |

0.83 ± 0.01 ab |

| Selenite 2 mM |

0.76 ± 0.02 a |

Table 3.

Effect of foliar application of two selenium salts on nutritional quality parameters in broccoli leaves.

Table 3.

Effect of foliar application of two selenium salts on nutritional quality parameters in broccoli leaves.

| |

Control |

Selenate 2 mM |

Selenite 2 mM |

| Antioxidant capacity |

2.76 ± 0.11 a |

4.38 ± 0.37 b |

3.44 ± 0.14 a |

| (mg ascorbic acid equiv. g-1 DW) |

| GSH-Px activity |

0.70 ± 0.03 a |

1.05 ± 0.13 a |

1.20 ± 0.28 a |

| (U g-1 DW) |

| Phenolic compounds |

4.27 ± 0.34 a |

6.93 ± 0.84 b |

6.53 ± 0.54 b |

| (mg gallic acid equiv. g-1 DW) |

| Soluble proteins content |

0.15 ± 0.01 a |

0.43 ± 0.02 c |

0.24 ± 0.02 b |

| (mg g-1 DW) |

Table 4.

Mineral concentration (µg g-1 DW) in broccoli leaves treated with selenium.

Table 4.

Mineral concentration (µg g-1 DW) in broccoli leaves treated with selenium.

| µg g-1

|

Control |

Selenate 2 mM |

Selenite 2 mM. |

| Se |

0.27 ± 0.00 a |

27.22 ± 0.26 b |

40.44 ± 1.37 c |

| K |

17258 ± 1872.09 a |

14904 ± 393.08 a |

18808 ± 1932.60 a |

| P |

2910 ± 91.53 a |

2687 ± 146.30 a |

2917 ± 195.65 a |

| Mg |

2811 ± 83.89 ab |

2518 ± 60.11 a |

3200 ± 143.72 b |

| Ca |

12809 ± 789.73 a |

11987 ± 519.65 a |

19826 ± 1183.18 b |

| S |

8257 ± 63.98 a |

9871 ± 446.20 b |

12971 ± 43.52 c |

| Fe |

27.69 ± 2.27 a |

42.66 ± 3.14 b |

46.48 ± 2.35 b |

| Mn |

36.61 ± 2.67 a |

29.14 ± 3.20 a |

52.34 ± 1.62 b |

| B |

36.53 ± 1.79 a |

37.47 ± 1.88 a |

37.39 ± 3.05 a |

| Zn |

25.66 ± 0.13 a |

26.70 ± 0.95 a |

25.16 ± 1.87 a |

| Mo |

11.53 ± 0.01 a |

9.69 ± 0.69 a |

15.30 ± 0.22 b |

| Cu |

2.32 ± 0.36 a |

2.41 ± 0.25 a |

3.00 ± 0.16 a |

| Ni |

0.30 ± 0.05 a |

0.24 ± 0.01 a |

0.23 ± 0.01 a |

Table 5.

Phytohormone concentration (ng g-1 DW) in broccoli leaves treated with selenium for methyl jasmonate (MJA), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), 3-indoleacetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA) and aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC).

Table 5.

Phytohormone concentration (ng g-1 DW) in broccoli leaves treated with selenium for methyl jasmonate (MJA), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), 3-indoleacetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA) and aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC).

| ng g-1

|

Control |

Selenate 2 mM |

Selenite 2 mM |

| [MJA] |

15.05 ± 0.92 a |

19.86 ± 3.03 ab |

28.99 ± 2.43 b |

| [JA] |

61.52 ± 5.74 b |

40.54 ± 2.89 a |

54.04 ± 6.32 ab |

| [SA] |

3216.33 ± 204.84 a |

3306.33 ± 112.72 a |

9793.00 ± 633.33 b |

| [IAA] |

12.27 ± 2.54 a |

27.38 ± 3.47 b |

10.87 ± 0.91 a |

| [ABA] |

51.08 ± 3.54 b |

97.44 ± 6.38 c |

28.84 ± 6.51 a |

| [ACC] |

5.85 ± 0.29 b |

6.75 ± 0.68 b |

3.55 ± 0.60 a |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).