Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

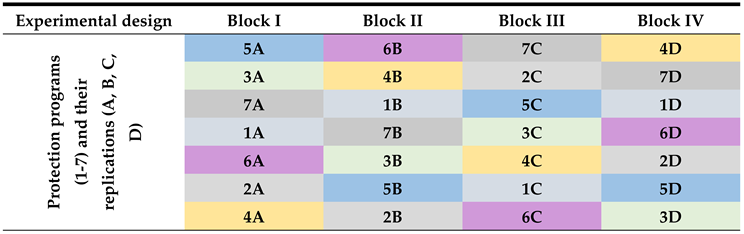

Field Trial

Control of the European Cherry Fruit Fly

Control of Cherry Leaf Spot Disease

Control of Brown Rot of the Cherry

Statistical Analysis

Pesticide Residues in Cherry Fruit

3. Results

| Treatment | Percentage of leaf infection by treatment replications | Average infection in treatment (%) (Ms)* | Sd* | Efficacy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| Dodine + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3a** | 0.12 | 96.03 |

| Dodine + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin + sucrose | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.2b | 0.19 | 98.01 |

| Untreated plot | 9.0 | 7.8 | 6 | 7.4 | 7.6c | 1.24 | - |

| LSD0.05 | 0.0193 | ||||||

| LSD0.01 | 0.0444 | ||||||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- González-Núñez, M.; Sandín-España, P.; Mateos-Miranda, M.; Cobos, G.; De Cal, A.; Sánchez-Ramos, I.; Alonso-Prados, J.L.; Larena, I. Development of a Disease and Pest Management Program to Reduce the Use of Pesticides in Sweet-Cherry Orchards. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakić, P., Matić, L., Božić, D., Vrbničanin, S., Jovanović-Radovanov, K., Elezović, I., Pavlović, D. Weed control in raspberry and blackberry plantings by herbicides. Acta Hortic. 2012, 946, 309–316. [CrossRef]

- Osipitan, O.A.; Yildiz-Kutman, B.; Watkins, S.; Brown, P.H.; Hanson, B.D. Impacts of repeated glyphosate use on growth of orchard crops. Weed Technol. 2020, 34, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holb, I.J. The brown rot fungi of fruit crops (Monilinia spp.). I. Important features of their biology. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2003, 9, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holb, I.J.; Szoke, S.; Abonyi, F. Temporal development and relationship amongst brown rot blossom blight, fruit blight and fruit rot in integrated and organic sour cherry orchards. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larena, I.; Villarino, M.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A. Epidemiological Studies of Brown Rot in Spanish Cherry Orchards in the Jerte Valley. J. Fungi 2021, 203, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Bertone, C.; Berrie, A. Effects of wounding, fruit age and wetness duration on the development of cherry brown rot in the UK. Plant Pathol. 2007, 56, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffer, T.J.; Lizotte, E.; Rothwell, N.L.; Sundin, G.W. Evaluation of dodine, fluopyram and penthiopyrad for the management of leaf spot and powdery mildew of tart cherry, and fungicide sensitivity screening of Michigan populations of Blumeriella jaapii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holb, I.J.; Lakatos, P.; Abonyi, F. Some aspects of disease management of cherry leaf spot (Blumeriella jaapii) with special reference to pesticide use. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 16, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszak, R.W.; Maciesiak, A. Problem of cherry fruit fly (Rhagoletis cerasi) in Poland – flight dynamics and control with some insecticides. Integrated plant protection in stone fruit IOBC/wprs Bull. 2004, 27, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Medic, A.; Hudina, M.; Veberic, R.; Solar, A. Walnut Husk Fly (Rhagoletis completa Cresson), the Main Burden in the Production of Common Walnut (Juglans regia L.). In Advances in Diptera - Insight, Challenges and Management Tools; Kumar, S., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2022; pp. 1–15.

- Daniel, C.; Grunder, J. Integrated Management of European Cherry Fruit Fly Rhagoletis cerasi (L.): Situation in Switzerland and Europe. Insects 2012, 3, 956–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaserhat, I. Investigation of Distribution, Population Development, Flight Period, Infestation and Damage Rate of Cherry Fruit Fly, Rhagoletis cerasi L. (Diptera: Tephritidae), Associated with Cherry and Sour Cherry Orchards. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2022, 64, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciesiak, A.; Olszak, R.W. Perspective of control of cherry fruit fly (Rhagoletis cerasi L.) with neonicotinoid pesticides. Prog. Plant Prot. 2005, 45, 877–880. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin, C.D.S. The e-Pesticide Manual, ver. 5.0; British Crop Protection Council: Farnham, Surrey, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Profaizer, D.; Angeli, G.; Sofia, M.; Zadra, E. Chemical control of Drosophila suzukii infesting cherries. Inf. Agrar. 2015, 71, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shawer, R.; Tonina, L.; Tirello, P.; Duso, C.; Mori, N. Laboratory and field trials to identify effective chemical control strategies for integrated management of Drosophila suzukii in European cherry orchards. Crop Prot. 2018, 103, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowles, R.C.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Holdcraft, R.; Loeb, G.M.; Elsensohn, J.E.; Hesler, S.P. Sucrose Improves Insecticide Activity Against Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-10/documents/alphacomplete.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- EU – EC 1. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/start/screen/active-substances/details/1206 (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- EU – EC 2. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/start/screen/mrls (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- EU – EC 3. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels_en (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Jacquet, F.; Jeuffroy, M.H.; Jouan, J.; Le Cadre, E.; Litrico, I.; Malausa, T.; Reboud, X.; Huyghe, C. Pesticide-free agriculture as a new paradigm for research. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous 1. Commission Regulation EC No 396/2005: Maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC. Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU) L 2005, 70/1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous 2. Design and analysis of efficacy evaluation trials PP 1/152 (4). Efficacy evaluation of plant protection products. EPPO Bull. 2012, 42, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous 3. Dose expression for plant protection products PP 1/239 (3). Efficacy evaluation of plant protection products. EPPO Bull. 2021, 51, 10–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous 4. Rhagoletis cerasi PP 1/35 (2). In EPPO standards, Guidelines for the efficacy evaluation of plant protection products: Insecticides and Acaricides, European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization, EU, 1997, Volume 3, pp. 52–54.

- Anonymous 5. Blumeriella jaapii PP 1/30 (2). In EPPO Standards, Guidelines for the Efficacy Evaluation of Plant Protection Products: Fungicides and Bactericides, European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization, EU, 2004, Volume 2, pp. 44–46.

- Schuster, M.; Tobutt, K.R. Screening of Cherries for Resistance to Leaf Spot, Blumeriella jaapii. Acta Hortic. 2004, 663, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, G.R.; Heuberger, J.W. Methods for estimating losses caused by diseases in fungicide experiments. Plant Dis. Rep. 1943, 27, 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, W.S. A Method of Computing the Effectiveness of an Insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous 6. Commission Directive 2002/63/EC: Methods of sampling for the official control of pesticide residues in and on products of plant and animal origin. Official Journal of the European Community (OJEC) L 2002, 187/30.

- Anastassiades, M.; Lehotay, S.J.; Stajnbaher, D.; Schenck, F.J. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and “dispersive solid-phase extraction” for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payá, P.; Anastassiades, M.; Mack, D.; Sigalova, I.; Tasdelen, B.; Oliva, J.; Barba, A. Analysis of pesticide residues using the quick easy cheap effective ruggedand safe (QuEChERS) pesticide multiresidue method in combination withgas and liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometric detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 389, 1697–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesueur, C.; Knittl, P.; Gartner, M.; Mentler, A.; Fuerhacker, M. Analysis of 140 pesticides from conventional farming foodstuff samples after extraction with the modified QuEChERS method. Food Control. 2008, 19, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehotay, S.J.; Son, K.A.; Kwon, H.; Koesukwiwat, U.; Fu, W.; Mastovska, K.; Hoh, E.; Leepipatpiboon, N. Comparison of QuEChERS sample preparation methods for the analysis of pesticide residues in fruit and vegetables. J. Chromatogr. A. 2010, 1217, 2548–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, P.; Grimalt, S.; Dabrio, M.; Cordeiro, F.; Fiamegos, Y.; Robouch, P.; Fernandez-Alba, A.R.; de la Calle, B. Proficiency test on the determination of pesticide residues in grapes with multi-residue methods. J. Chromatogr. A. 2015, 1395, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, S., Šunjka, D., Jovanov, P., Vuković, S., Guzsvány, V. LC-MS/MS determination of acetamiprid residues in sweet cherries. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 23, 13317–13326.

- Shawer, R.; Tonina, L.; Tirello, P.; Duso, C.; Mori, N. Laboratory and field trials to identify effective chemical control strategies for integrated management of Drosophila suzukii in European cherry orchards. Crop Prot. 2018, 103, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaskaveg, J.E.; Förster, H.; Gubler, W.D.; Teviotdale, B.L.; Thompson, D.F. Reduced-risk fungicides help manage brown rot and other fungal diseases of stone fruit. Calif. Agr. 2005, 59, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, V.; Vuković, S.; Grahovac, M.; Lazić, S.; Aleksić, G.; Šunjka, D. Fungicide application and residues in control of Blumeriella jaapii (Rehm) Arx in sweet cherry. Emir. J. Food Agr. 2021, 33, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.A.; Nabi, S.U.; Khan, N.A. Evaluation of different fungicides for effective management of Blumeriella leaf spot of cherry in Kashmir valley. Indian Phytopathol. 2016, 69, 314–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lazić, S.; Šunjka, D.; Panić, S.; Inđić, D.; Grahovac, N.; Guzsvány, V.; Jovanov, P. Dissipation rate of acetamiprid in sweet cherries. Pestic. Phytomed. (Belgrade). 2014, 29, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, D.R.; Beers, E.H. Chemical control programs for Drosophila suzukii that comply with international limitations on pesticide residues for exported sweet cherries. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2012, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanWoerkom, A.H.; Whalon, M.E.; Gut, L.J.; Kunkel, D.L.; Wise, J.C. Impact of Multiple Applications of Insecticides and Post-harvest Washing on Residues at Harvest and Associated Risk for Cherry Export. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2022, 22, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Protection program | Commercial products | Amount of a.i. per ha | Date of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acetamiprid + Dodine | Afinex 20 SP + Syllit 400 SC | 50 g + 600 g | June 2, 2023 |

| Acetamiprid + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin | Afinex 20 SP + Signum* | 50 g + 200.25 g + 50.25 g | June 9, 2023 | |

| 2. | Acetamiprid + Dodine + sucrose | Afinex 20 SP + Syllit 400 SC + sucrose | 50 g + 600 g + 1.2 kg | June 2, 2023 |

| Acetamiprid + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin + sucrose | Afinex 20 SP + Signum + sucrose | 50 g + 200.25 g + 50.25 g + 1.2 kg | June 9, 2023 | |

| 3. | Spinetoram + Dodine | Delegate 250 WG + Syllit 400 SC | 75 g + 600 g | June 2, 2023 |

| Spinetoram + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin | Delegate 250 WG + Signum | 75 g + 200.25 g + 50.25 g | June 9, 2023 | |

| 4. | Spinetoram + Dodine + sucrose | Delegate 250 WG + Syllit 400 SC + sucrose | 75 g + 600 g + 1.2 kg | June 2, 2023 |

| Spinetoram + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin + sucrose | Delegate 250 WG + Signum + sucrose | 75 g + 200.25 g + 50.25 g + 1.2 kg | June 9, 2023 | |

| 5. | Spinetoram + Dodine | Delegate 250 WG + Syllit 400 SC | 75 g + 600 g | June 2, 2023 |

| Spinetoram + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin | Delegate 250 WG + Signum | 75 g + 200.25 g + 50.25 g | June 9, 2023 | |

| Spinetoram | Delegate 250 WG | 75 g | June 16, 2023 | |

| 6. | Spinetoram + Dodine + sucrose | Delegate 250 WG + Syllit 400 SC + sucrose | 75 g + 600 g + 1,2 kg | June 2, 2023 |

| Spinetoram + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin + sucrose | Delegate 250 WG + Signum + sucrose | 75 g + 200.25 g + 50.25 g + 1.2 kg | June 9, 2023 | |

| Spinetoram + sucrose | Delegate 250 WG + sucrose | 75 g +1.2 kg | June 16, 2023 | |

| 7. | Untreated plot | - | - | - |

| Active substance | Precursor ion, m z-1 | Product ion, m z-1 | Retention time (min) | Fragmentation energy(V) | Collision energy (V) | Polarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acetamiprid | 223.1 | 126 | 9.17 | 80 | 27 | positive |

| 90 | 80 | 45 | ||||

| boscalid | 343 | 307.1 | 14.36 | 145 | 16 | positive |

| 272.1 | 145 | 32 | ||||

| 271.2 | 145 | 32 | ||||

| dodine | 228.2 | 60.5 | 12.69 | 130 | 23 | positive |

| 57.1 | 130 | 23 | ||||

| pyraclostrobin | 388.11 | 193.8 | 16.47 | 95 | 8 | positive |

| 163.1 | 95 | 20 | ||||

| spinetoram J | 748.4 | 203 | 13.59 | 170 | 40 | positive |

| 142 | 170 | 32 | ||||

| spinetoram D | 760.4 | 203.1 | 14.07 | 170 | 34 | positive |

| 142 | 170 | 34 | ||||

| Carbofurane d3 | 225.1 | 165 | 11.56 | 94 | 10 | positive |

| 123 | 94 | 22 |

| Active supstance | Correlation coeficient R^2 | Recovery (%) at level 0.01 mg kg-1 | Recovery (%) at level 0.1 mg kg-1 | LOD* (µg kg-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acetamipride | 0.994 | 81.2 | 73.6 | 0.34 |

| boscalid | 0.996 | 91.2 | 86.9 | 5.89 |

| dodine | 0.996 | 74.2 | 105.8 | 3.42 |

| pyraclostrobin | 0.995 | 111.4 | 81.5 | 0.18 |

| spinetoram J | 0.999 | 78.8 | 93.5 | 0.20 |

| spinetoram D | 0.999 | 90.1 | 74.9 | 0.31 |

| Insecticide | The percentage of fruit damage after treatment replication | Average infestation in treatment (%) (Ms)** | Sd* | Efficacy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| Acetamiprid (2x)* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0a*** | 0 | 100 |

| Acetamiprid + sucrose (2x) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0a | 0 | 100 |

| Spinetoram (2x) | 2.0 | 2.33 | 1.67 | 3.0 | 2.3b | 0.57 | 66.67 |

| Spinetoram + sucrose (2x) | 2.0 | 1.67 | 1.33 | 1.0 | 1.5c | 0.43 | 77.78 |

| Spinetoram (3x)* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0a | 0 | 100 |

| Spinetoram + sucrose (3x) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0a | 0 | 100 |

| Untreated plot | 8.33 | 5.33 | 6.0 | 7.33 | 6.8d | 1.34 | - |

| LSD0.05 | 0.0100 | ||||||

| LSD0.01 | 0.0152 | ||||||

| Treatment | Percentage of fruit infection by treatment replications | Average infection in treatment (%) (Ms)* | Sd | Efficacy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin | 1.0 | 1.67 | 1.33 | 1.0 | 1.3a** | 0.32 | 86.11 |

| Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin + sucrose | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.5b | 0.19 | 94.44 |

| Untreated plot | 10.33 | 7.33 | 8.33 | 10.0 | 9.0c | 1.41 | - |

| LSD0.05 | 0.0366 | ||||||

| LSD0.01 | 0.0844 | ||||||

| A sample (protection program) |

Sampling date: | acetamiprid (mg kg-1) | spinetoram (mg kg-1) |

dodine (mg kg-1) |

boscalid (mg kg-1) |

pyraclostrobin (mg kg-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHI (days) | ||||||

| 14 | 7 | 21 | 14 | 14 | ||

| MRL (mg kg-1) in EU | ||||||

| 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Acetamiprid 2x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x | June 23, 2023 | 0.167 | - | 0.45 | <0.01 | <0,01 |

| Acetamiprid 2x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x + sucrose 2x | June 23, 2023 | 0.197 | - | 0.585 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Spinetoram 2x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x | June 23, 2023 | - | <0.01 | 0.918 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Spinetoram 2x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x + sucrose 2x | June 23, 2023 | - | <0.01 | 1.39 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Spinetoram 2x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x | June 16, 2023 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.199 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Spinetoram 2x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x + sucrose 2x | June 16, 2023 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.593 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Spinetoram 3x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x | June 23, 2023 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.522 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Spinetoram 3x + Dodine 1x + Boscalid + Pyraclostrobin 1x + sucrose 2x | June 23, 2023 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.787 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Untreated plot | June 23, 2023 | - | - | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).