Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Historical Population and Food Production/Consumption Projections

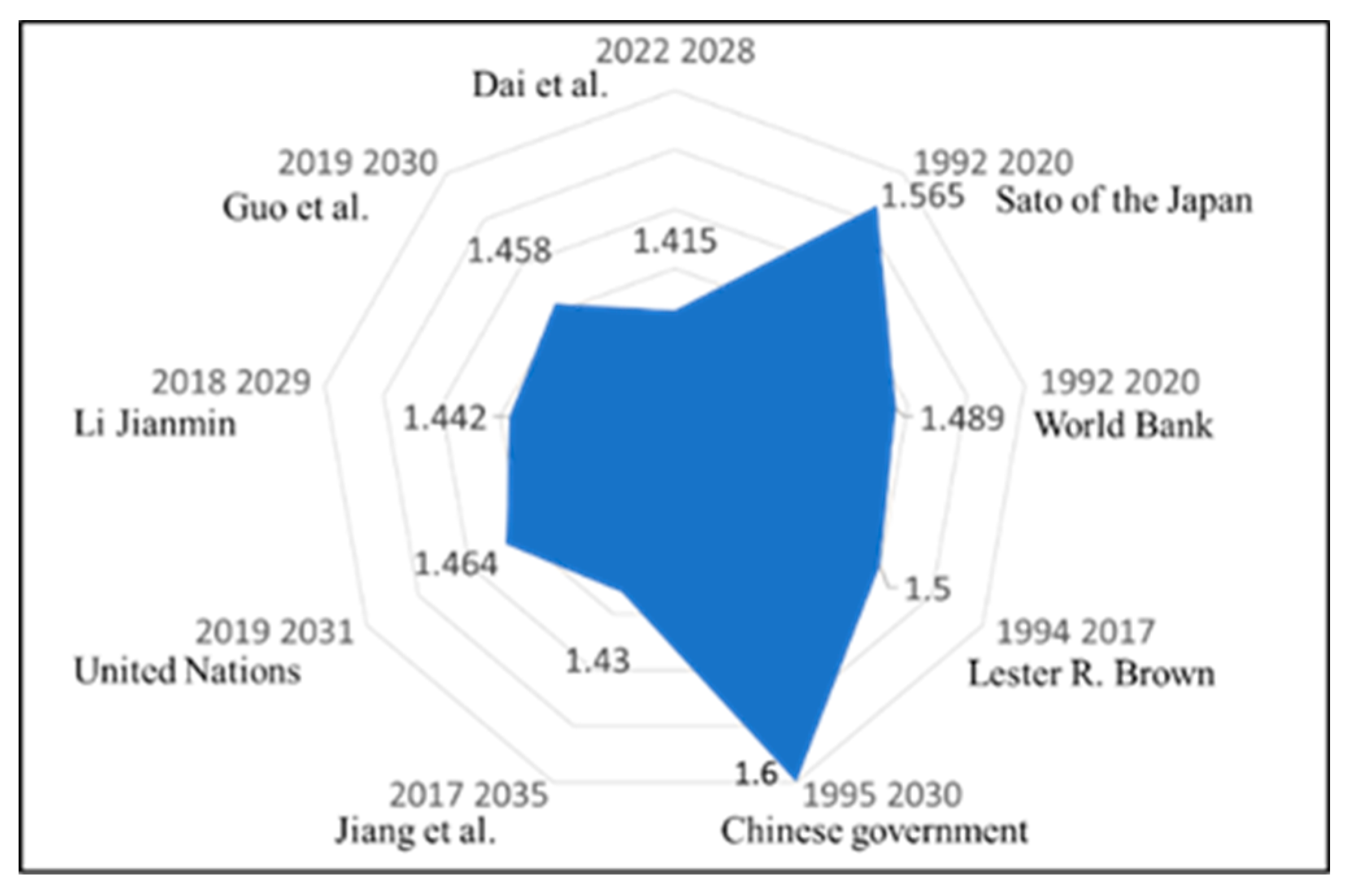

2.1. Past Predictions of Chinese Population

2.2. Past Predictions of Food Production/Consumption

3. Actual Population and Food Production/Consumption Trends Up to 2023

3.1. Changes in Population Growth

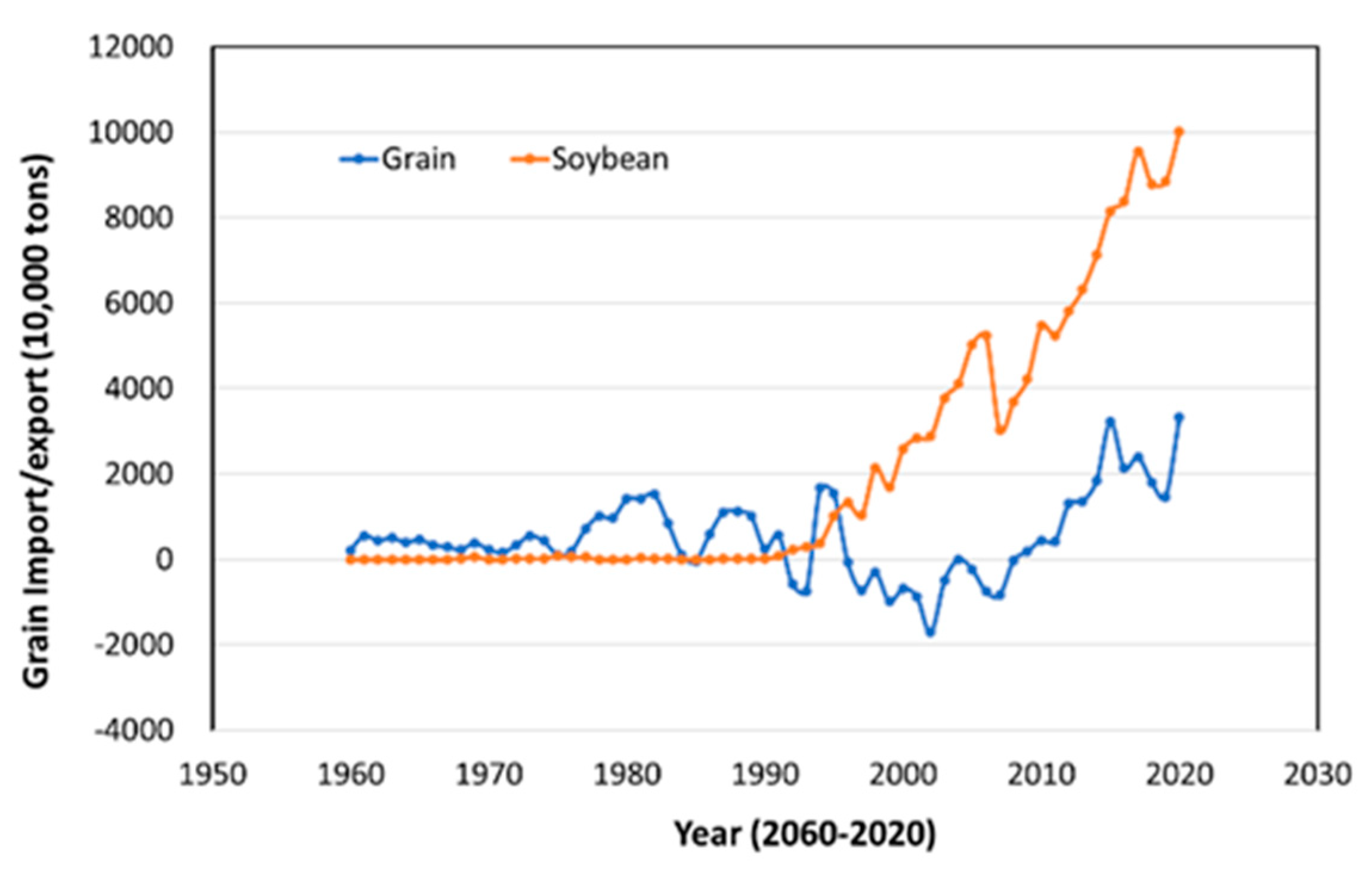

3.2. Changes in Grain Import/Export

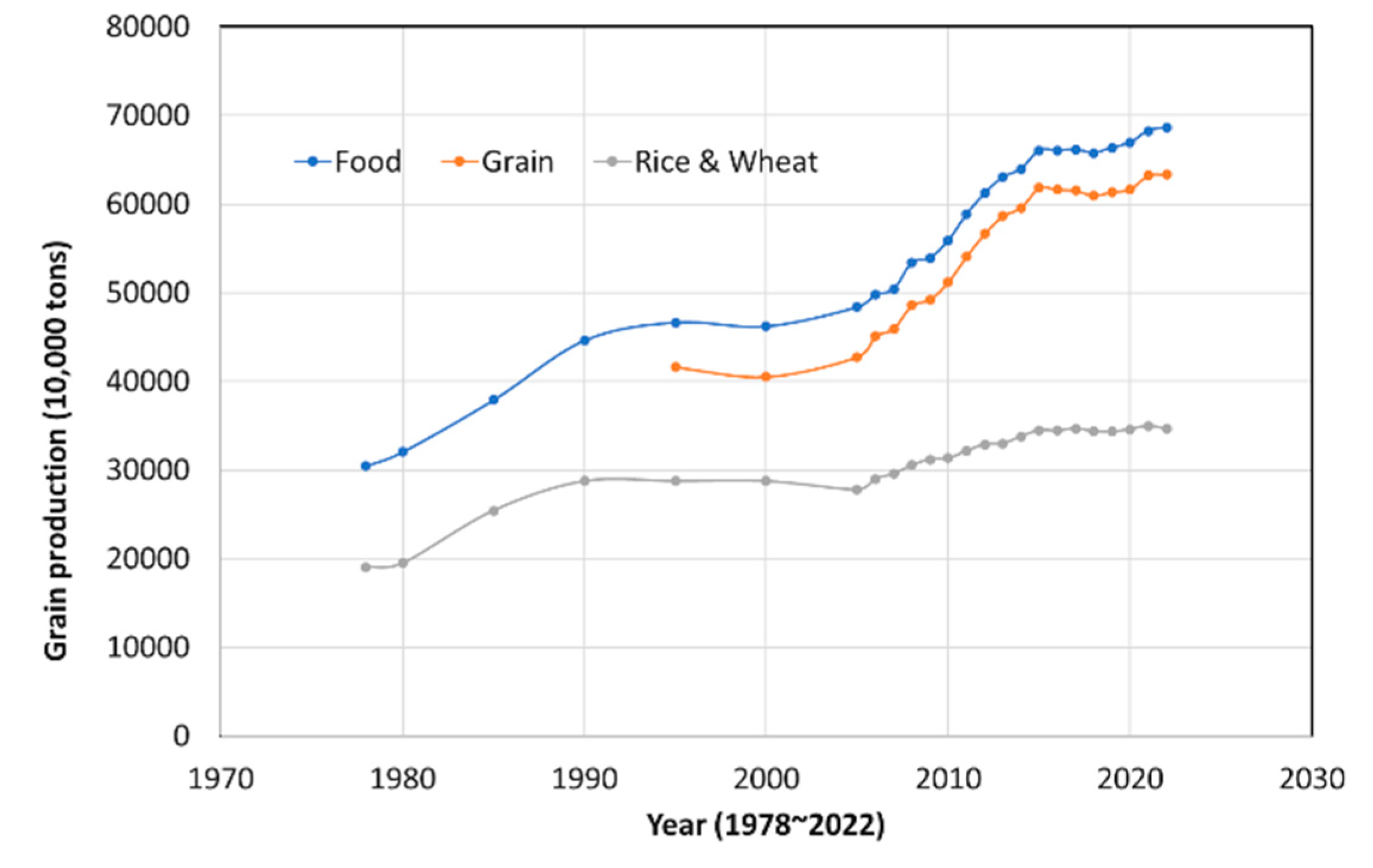

3.3. Changes in Food Production

4. Factors Contributing to the Increase in China's Food Production and Food Imports

4.1. Factors Contributing to the Increase in China's Food Production

4.1.1. Government Food Production Policies

4.1.2. Introduction of High-Yield Crops (Including Varietal Improvements) and Changes in Food Consumption Structure

4.1.3. Introduction of Chemical Fertilizers, Pesticides, and New Technologies

Chemical Fertilizers

Pesticides

Introduction of New Technologies

4.2. Factors Contributing to the Increase in Food Imports

4.2.1. International Grain Prices: Grain Prices Are Upside Down Domestically and Internationally

4.2.2. Domestic Supply Structure: The Structural Supply of Domestically Produced Grains is Insufficient

4.2.3. Demand for International Trade Diplomacy: Sometimes Necessitates Importing Food Sources

4.3. Reasons Why Soybean Production Cannot Achieve 100% Self-Sufficiency

4.3.1. Low Yield of Domestically Produced Soybeans

4.3.2. Relatively High Cost of Soybean Cultivation in China

4.3.3. Limited Per Capita Land, Unable to Meet the Demand for Soybean Cultivation

5. Future Issues and Countermeasures

5.1. Population Issue

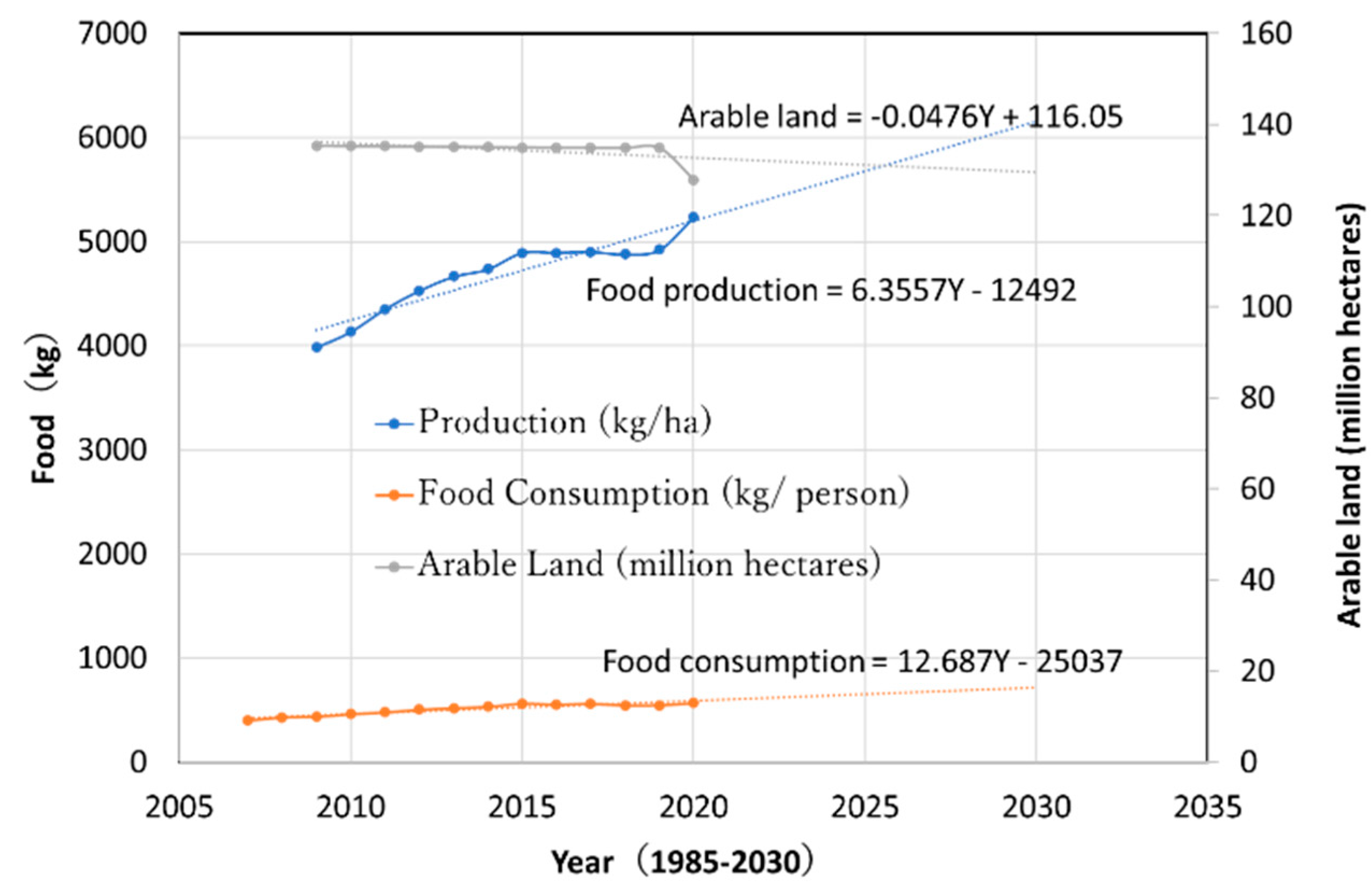

5.2. Food Issue

5.3. China's Countermeasures

5.4. Some Suggestions about Food Productions

5.4.1. Promote Sustainable Agricultural Practices:

5.4.2. Increase Investment in Agricultural Innovation:

5.4.3. Enhance Support for Smallholder Farmers:

5.4.4. Optimize Land Use and Protect Farmland:

5.4.5. Improve Food Supply Chain and Storage Infrastructure:

5.4.6. Encourage Water-Efficient Crop Choices:

5.4.7. Enhance Food Import Policies as a Supplementary Strategy:

5.4.8. Implement Population and Labour Policies to Support Agriculture:

5.4.9. Promote Awareness and Education on Food Conservation:

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Brown, L. R. Who Will Feed China? Wake-up Call for a Small Planet, W.W. Norton & Company, New York and London, 1995.

- Brown, L. R. Outgrowing the Earth: The Food Security Challenge in an Age of Falling Water Tables and Rising Temperatures, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2004.

- Brown, L. R. The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity, Norton & Company, New York and London, 2012.

- Fukase E. and Martin W. Who Will Feed China in the 21st Century? Income Growth and Food Demand and Supply in China. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2016, Vol. 67 No. 1, 3–23. [CrossRef]

- Huang J. and Yang G. Understanding Recent Challenges and New Food Policy in China, Global Food Security, 2017, Vol. 12, 119–126.

- Dong K., Prytherch M., McElwee M., Kim P., Jude Blanchette J. and Hass R. China’s food security: Key challenges and emerging policy responses, CSIS BRIEFS, Available online at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-food-security-key-challenges-and-emerging-policy-responses (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Zhang Y. and Lu X. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Food Security in China and Its Obstacle Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023, Vol. 20 No. 1, 451. [CrossRef]

- Cui K. and Shoemaker S. P. A look at food security in China. Science of Food, 2018, Vol. 2 No. 4, doi:10.1038/s41538-018-0012-x.

- Veeck, G. China’s food security: past success and future challenges, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 2013, Vol. 54 No. 1, 42–56. [CrossRef]

- Nie F., Bi J. and Zhang X. Study on China’s Food Security Status. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 2010, Vol. 1, 301–310.

- Wong J. and Huang J. China's Food Security and Its Global Implications, China. An International Journal, 2012. Vol. 10 No. 1, 113-124. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/472545.

- Ghose B. Food security and food self-sufficiency in China: from past to 2050. Food and Energy Security, 2014, Vol. 3 No. 2, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Huang J., Wei W. and Cui Q. The prospects for China’s food security and imports: Will China starve the world via imports? Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2017, Vol. 16 No.12, 2933–2944.

- He G., Zhao Y., Wang L., Jiang S. and Zhu Y. China's food security challenge: Effects of food habit changes on requirements for arable land and water, Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, Vol. 229, 739-750.

- Liu Y. and Zhou Y. Reflections on China's food security and land use policy under rapid urbanization, Land Use Policy, 2021, Vol. 109, 105699. [CrossRef]

- Niu Y., Xie G., Xiao Y., Liu J., Zou H., Qin K., Wang Y, Huang M. The story of grain self-sufficiency: China's food security and food for thought, Food Energy Security, 2022, Vol. 11, e344. [CrossRef]

- Liang X., Jin X., Dou Y., Meng F. and Zhou Y. Exploring China's food security evolution from a local perspective. Applied Geography, 2024, Vol. 172, 103427. [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I. The adaptation and mitigation potential of traditional agriculture in a changing climate, Climatic Change, 2017, Vol. 140, 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Yu T., Mahe L., Li Y., Wei X., Deng X. and Zhang D. Benefits of Crop Rotation on Climate Resilience and Its Prospects in China. Agronomy, 2022, Vol. 12 No. 2, 436; [CrossRef]

- Xu Y., Li J., and Wan J. Agriculture and crop science in China: Innovation and sustainability. The Crop Journal, 2017, Vol. 5, 95-99.

- Chen J., Zhong F. and Sun D. Lessons from farmers’ adaptive practices to climate change in China: a systematic literature review. Environment Science Pollution Research, 2022, Vol. 29, 81183–81197. [CrossRef]

- Nsabiyeze A., Ma R., Li J., Luo H., Zhao Q., Tomka J. Tackling climate change in agriculture: A global evaluation of the effectiveness of carbon emission reduction policies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024, Vol. 468, 142973. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Chu, B., Tang, R. et al. Air quality improvements can strengthen China’s food security, Nature Food, 2024, Vol. 5, pp.158–170. [CrossRef]

- Sato Ryuzaburo. China's Future Demographics. In Yasuko Hayase (Eds.), China's Population Changes, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), Chiba, Japan, 1992, pp.287-301.

- Chinese government (1996). White paper: China's Food Issues (in Chinese). https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2005-05/25/content_2615740.htm.

- United Nations. (2019). World Population Prospects, The 2019 Revision. (accessed 19 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, K. China’s long-term demographic trends and their impact on the economy and society (part 1). https://spc.jst.go.jp/experiences/special/economics/economics_2112.html, 2011. (accessed on 12 Dec 2024).

- Guo A., Ding X., Zhong F., Cheng Q., and Huang C. Predicting the Future Chinese Population using Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, the Sixth National Population Census, and a PDE Model. Sustainability, 2019, Vol. 11 No. 13, 3686; [CrossRef]

- Dai, K., Shen, S. & Cheng, C. Evaluation and analysis of the projected population of China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3644. [CrossRef]

- Jiang T., Zhao J., Jing C., Cao L., Wang Y., Sun H., Wang A., Huang J., Su B., Wang R. National and Provincial Population Projected to 2100 Under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways in China. Climate Change Research, 2017, Vol. 13 No. 2, 128-137.

- Rieffel L. and Wang X. China’s Population Could Shrink to Half by 2100 - Is China’s future population drop a crisis or an opportunity? Available online at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chinas-population-could-shrink-to-half-by-2100 (accessed 28 February 2024).

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024. https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/. (accessed 19 February 2024).

- Konishi. Global food supply and demand outlook (in Japanese). Available online at: https://www.maff.go.jp/primaff/kanko/review/attach/pdf/070629_pr24_02.pdf. (accessed 28 February 2024).

- Huang J., Rozelle S., and Rosegrant M. China's Food Economy to the Twenty-first Century: Supply, Demand, and Trade. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 1999, Vol. 47 No. 4, . [CrossRef]

- Sun X., Lin Z., Sun Y. Dynamic Prediction and Suggestion of Total Farmland in China. Journal of natural resources, 2005, Vol. 20 No. 2, 200-205. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X. Review of mid- and long-term predictions of China's grain security. China Agricultural Economic Review, 2013, Vol. 5 No. 4, 567-582. [CrossRef]

- Hamshere P., Sheng Y., Moir B., Syed F. and Caroline G. What China wants - Analysis of China's food demand to 2050. Paper presented at the 44th ABARES Outlook conference 4–5 March 2014, Canberra, ACT. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/sitecollectiondocuments/abares/publications/AnalysisChinaFoodDemandTo2050_v.1.0.0.pdf. (accessed 4 October 2024).

- Sheng Y. and Song L. Agricultural production and food consumption in China: A long-term projection. China Economic Review, 2019, Vol. 53, pp.15-29.

- Zhang X., Bao J., Xu S., Wang Y. and Wang S. Prediction of China’s Grain Consumption from the Perspective of Sustainable Development—Based on GM(1,1) Model. Sustainability, 2022, Vol. 14 No. 17, 10792. [CrossRef]

- Du Y., Xu Y., Zhang L., Song S. Can China’s food production capability meet her peak food demand in the future? Based on food demand and production capability prediction till the year 2050. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 2019, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp.1 – 17. [CrossRef]

- Master F. China's population drops for second year, with record low birth rate, Reuters news 2024/01/17. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-population-drops-2nd-year-raises-long-term-growth-concerns-2024-01-17/. (accessed 4 October 2024).

- Zhai F. Macroeconomic Implications of China's Population Aging: A Dynamic OLG General Equilibrium Analysis, AMRO Working Paper (WP/24-09). https://amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/AMRO-WP_Macroeconomic-Implications-of-Population-Aging-in-China_Sept-2024.pdf. (accessed 4 October 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics. Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census. Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817185.html. (accessed 28 February 2024).

- Kawahara Shoichiro. China's food supply and demand problem (in Japanese). Agriculture, forestry and Fisheries Policy Research of Japan. Available at https://www.maff.go.jp/primaff/koho/seminar/2014/attach/pdf/141216_01.pdf. (accessed 4 October 2024).

- Xiao P. and Wang Q. Changes in food production in China since 1949 and their contributing factors. Geographical Review Ser. A, 1999, Vol. 72, 589-599. [CrossRef]

- Li J., Luo X. and Zhou K. Research and development of hybrid rice in China. Plant Breeding, 2024, Vol. 143 No. 1, 96-104. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K., P.K. Bhati, A. Sharma and V. Sahu. Super hybrid rice in China and India: Current status and future prospects. International Journal of Agriculture & Biology, 2015, Vol. 17, 221‒232.

- Yu X., Li H.2 and Doluschitz R. Towards Sustainable Management of Mineral Fertilizers in China: An Integrative Analysis and Review. Sustainability, 2020, Vol. 12 No.17, 7028; [CrossRef]

- Nishio N. Effects of the Law Prohibiting the Increase in the Application of Chemical Fertilizers on Chinese Agriculture, Nishio Morality's Environmental Conservation Agriculture Report No. 370. Available online at: https://lib.ruralnet.or.jp/nisio/?p=4635. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-food-security-key-challenges-and-emerging-policy-responses. (accessed 4 October 2024).

- Nishio N. Environmental Performance of Chinese Agriculture: Current Status and Challenges, Nishio Morality's Environmental Conservation Agriculture Report No.350. Available online at: https://lib.ruralnet.or.jp/nisio/?p=4035. (accessed 28 February 2024).

- Wang X., Chi Y. and Li F. Exploring China stepping into the dawn of chemical pesticide-free agriculture in 2050’, Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022, Vol. 13, 942117. [CrossRef]

- Hollósy Z, Ma’ruf MI, Bacsi Z. Technological Advancements and the Changing Face of Crop Yield Stability in Asia. Economies, 2023, Vol. 1 No.12, 297. [CrossRef]

- Huang W. and Wang X. The Impact of Technological Innovations on Agricultural Productivity and Environmental Sustainability in China. Sustainability, 2024, Vol. 16 No.19, 8480. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Policy Interpretation: Chinese rice bowl, Available online at: http://www.nkj.moa.gov.cn/zcjd/201906/t20190625_6319195.htm (accessed 10 October 2023).

- Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Japan. Economic Cooperation Program for China, Available online at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/region/e_asia/china-2.html. (accessed 10 November 2024).

- Lin Y., Zhang B., Hu M., Yao Q., Jiang M. and Zhu C. The effect of gradually lifting the two-child policy on demographic changes in China. Health Policy and Planning, 2024, Vol. 39, No. 4, 363–371. [CrossRef]

- Takeshige N. China's Growing Demographic Problem-Total population decline will be significantly accelerated, Ricoh Economic and Social Research Institute report. Available at https://blogs.ricoh.co.jp/RISB/china_asia/post_704.html. (accessed 21 February 2024).

- Chinese government. White paper: China's Food Security (in Chinese). Available at https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-10/14/content_5439410.htm. (accessed 4 November 2024).

- Ma L., Bai Z., Ma W., Guo M., Jiang R., Liu J., Oenema O., Velthof G. L., Whitmore A. P., Crawford J., Dobermann A., Schwoob M. and Zhang F. Exploring Future Food Provision Scenarios for China. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, Vol. 53 No. 3, 1385–1393. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Chang, J., Havlík, P. et al. China’s future food demand and its implications for trade and environment. Nature Sustainability, 2021, Vol. 4, 1042–1051. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Su, M., Wang, Y. et al. Food production in China requires intensified measures to be consistent with national and provincial environmental boundaries. Nature Food, 2020, Vol. 1, 572–582. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).