Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

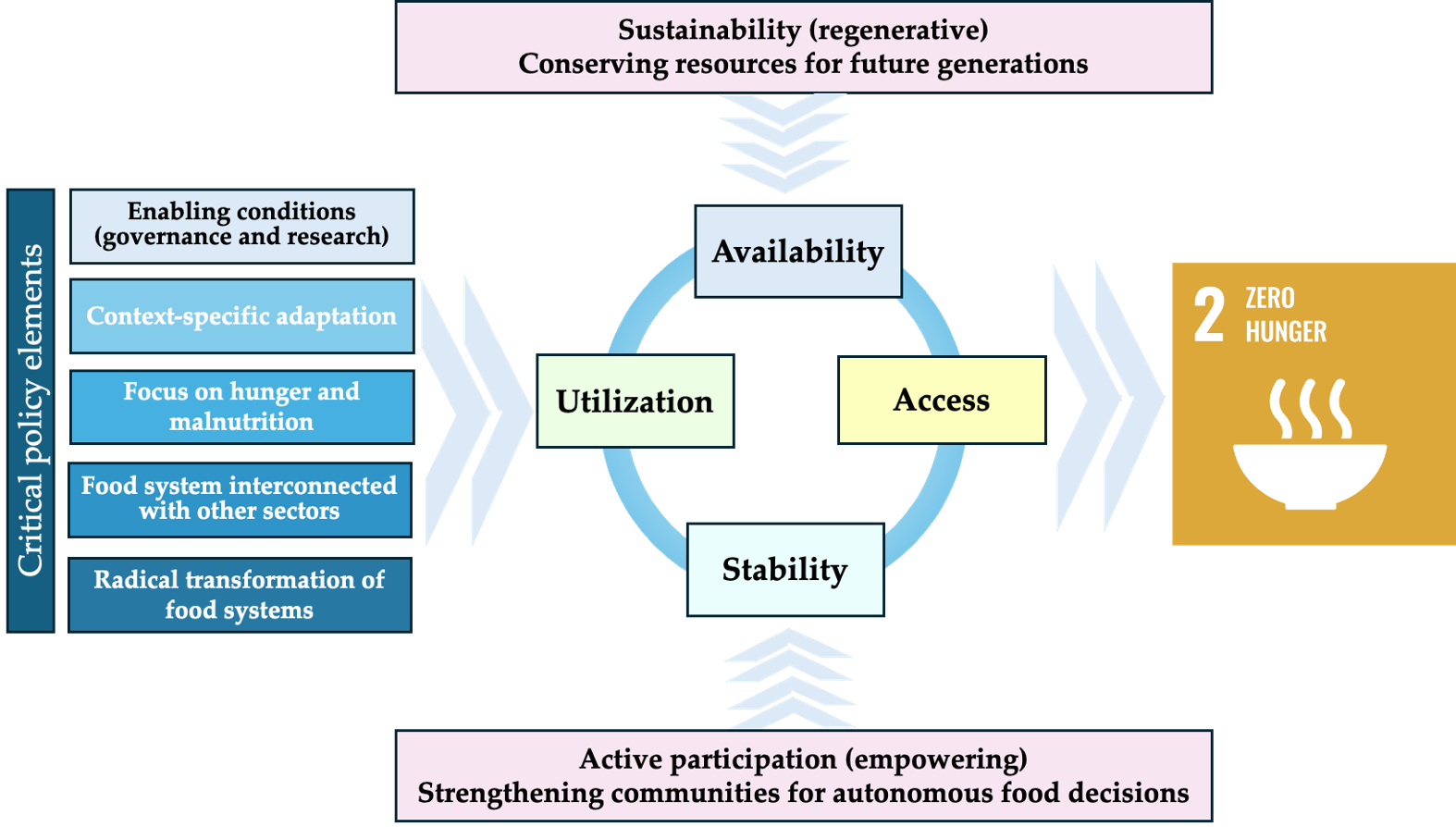

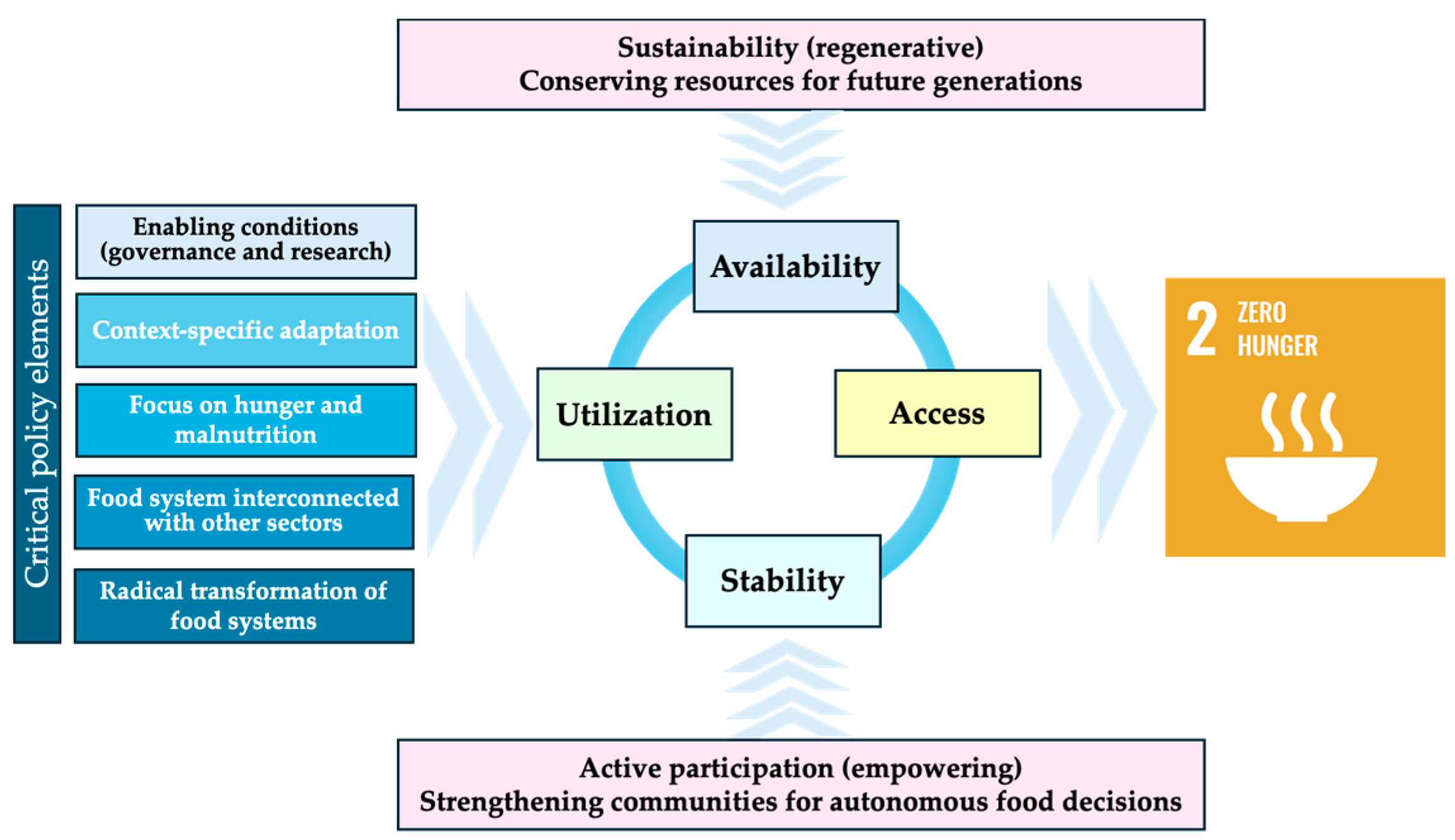

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Comparative Analysis

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis by Testing the Significance of Differences

3. Results

3.1. Results of Comparing the Value of the Pillars Indicators in Romania with the Average of Neighboring States

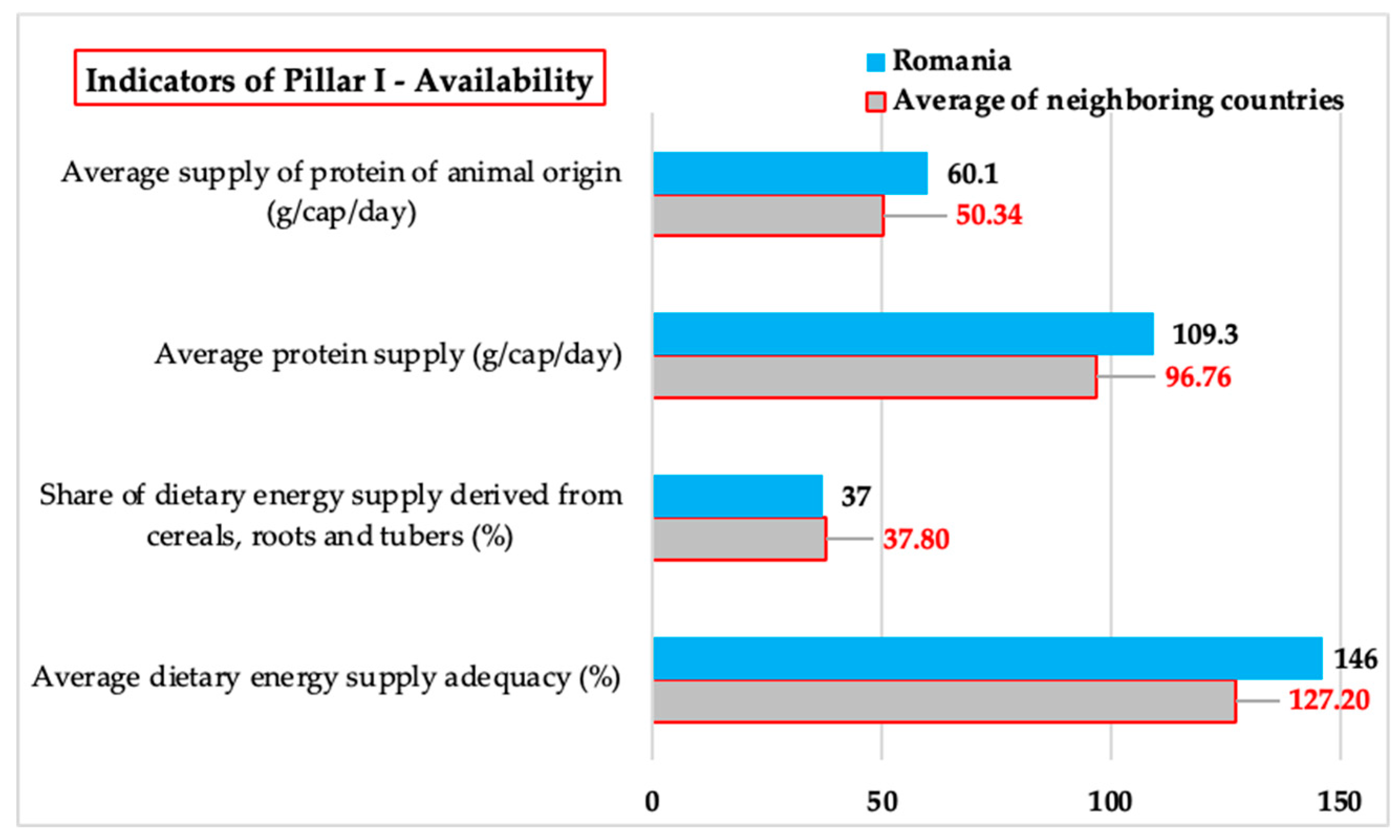

3.1.1. Availability – Comparative Analysis of the Values of Indicators Related to Food Availability

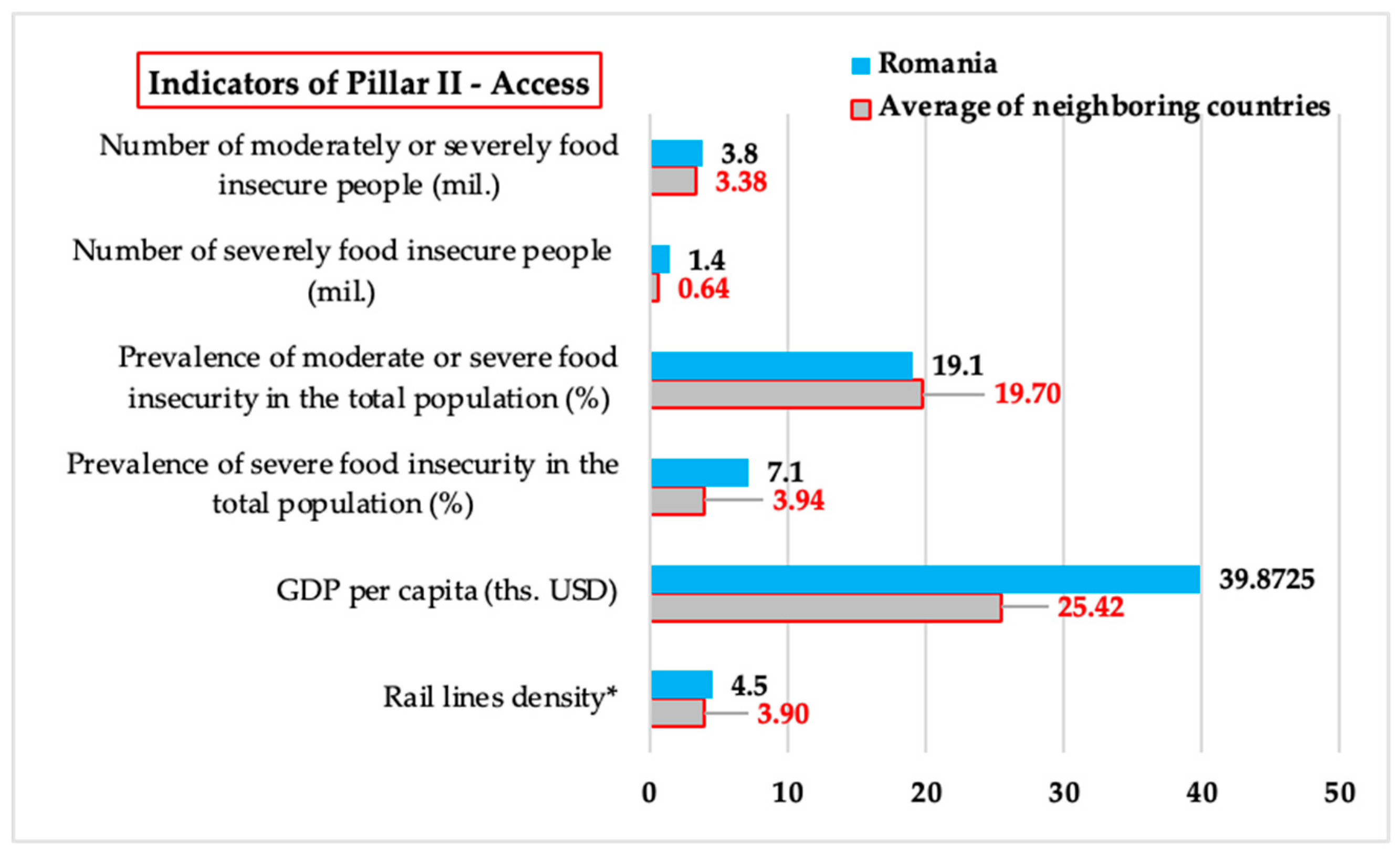

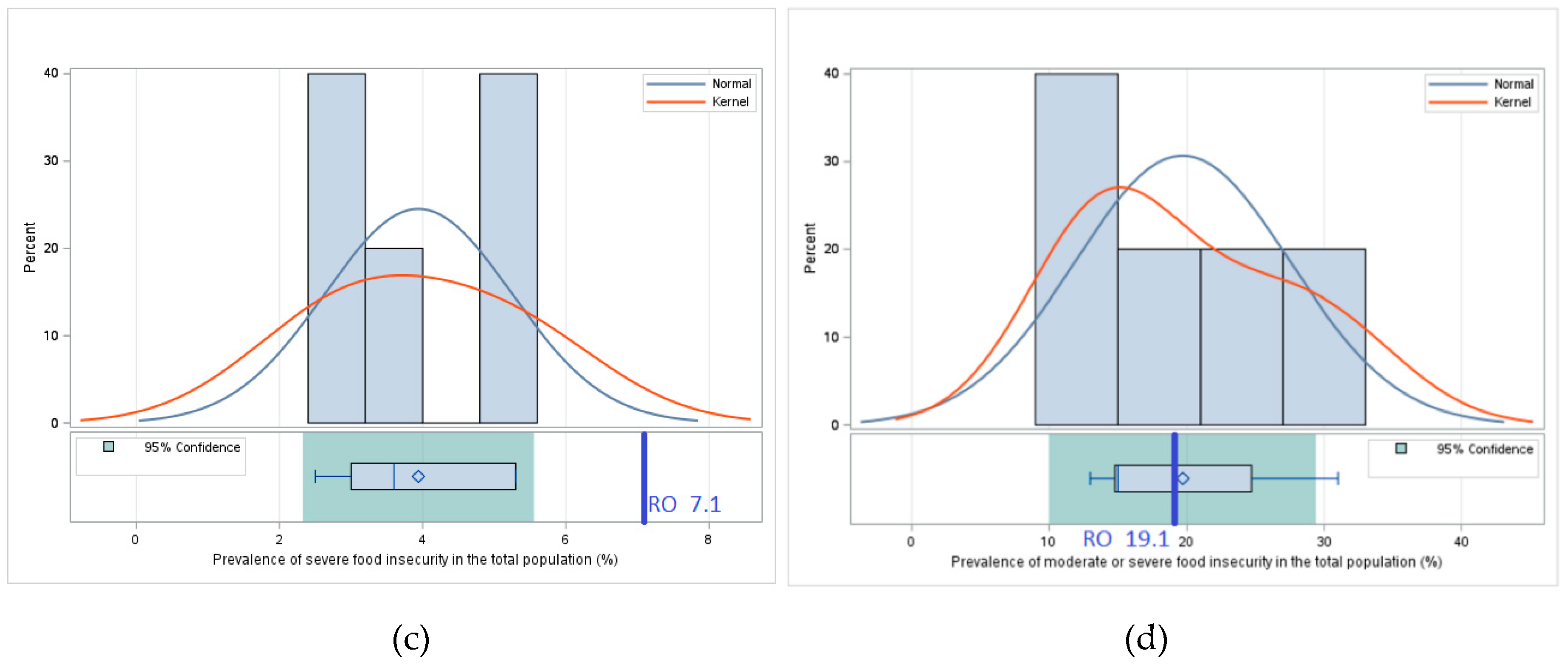

3.1.2. Access – Comparative Analysis of Values of Indicators Related to Food Accessibility

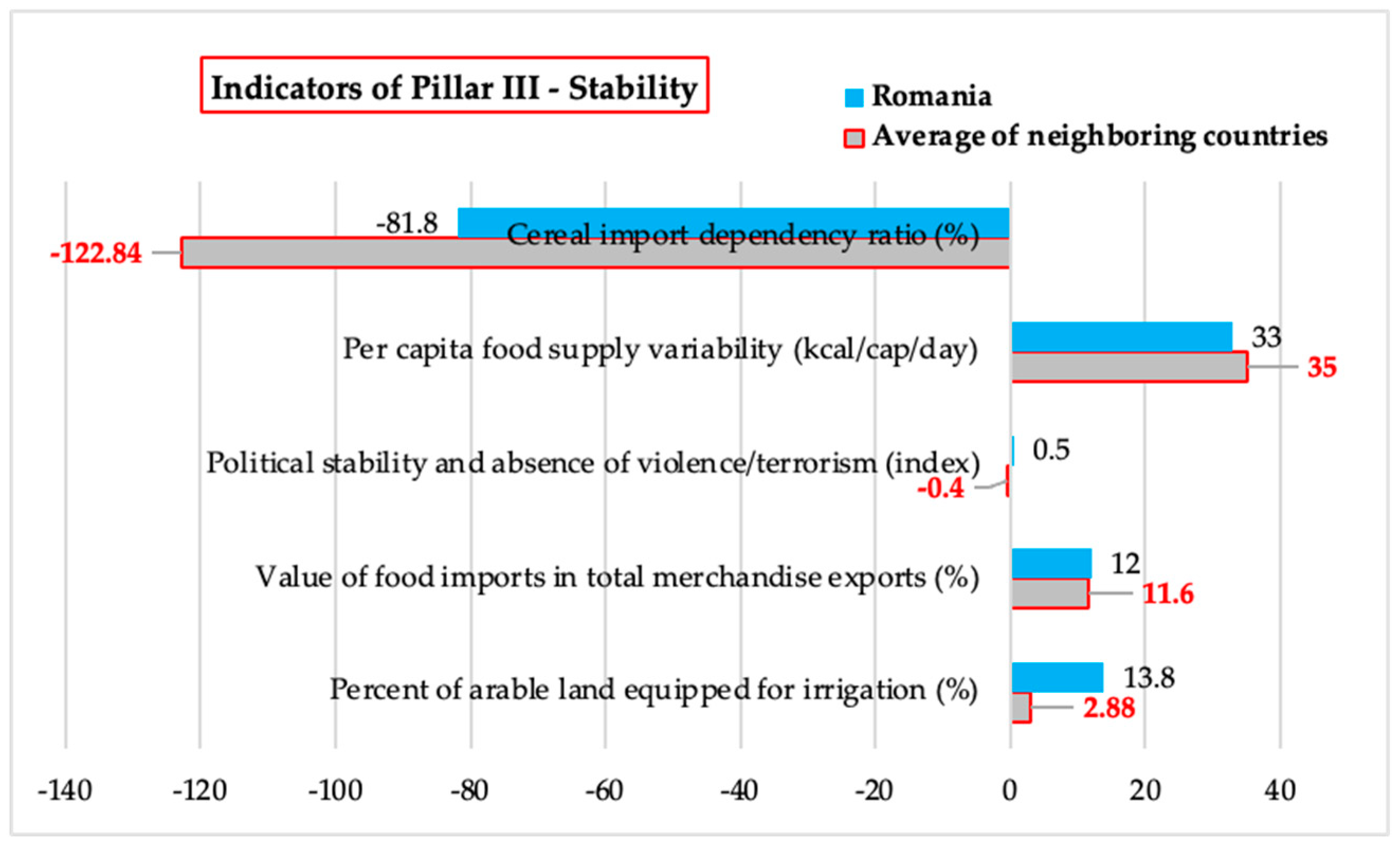

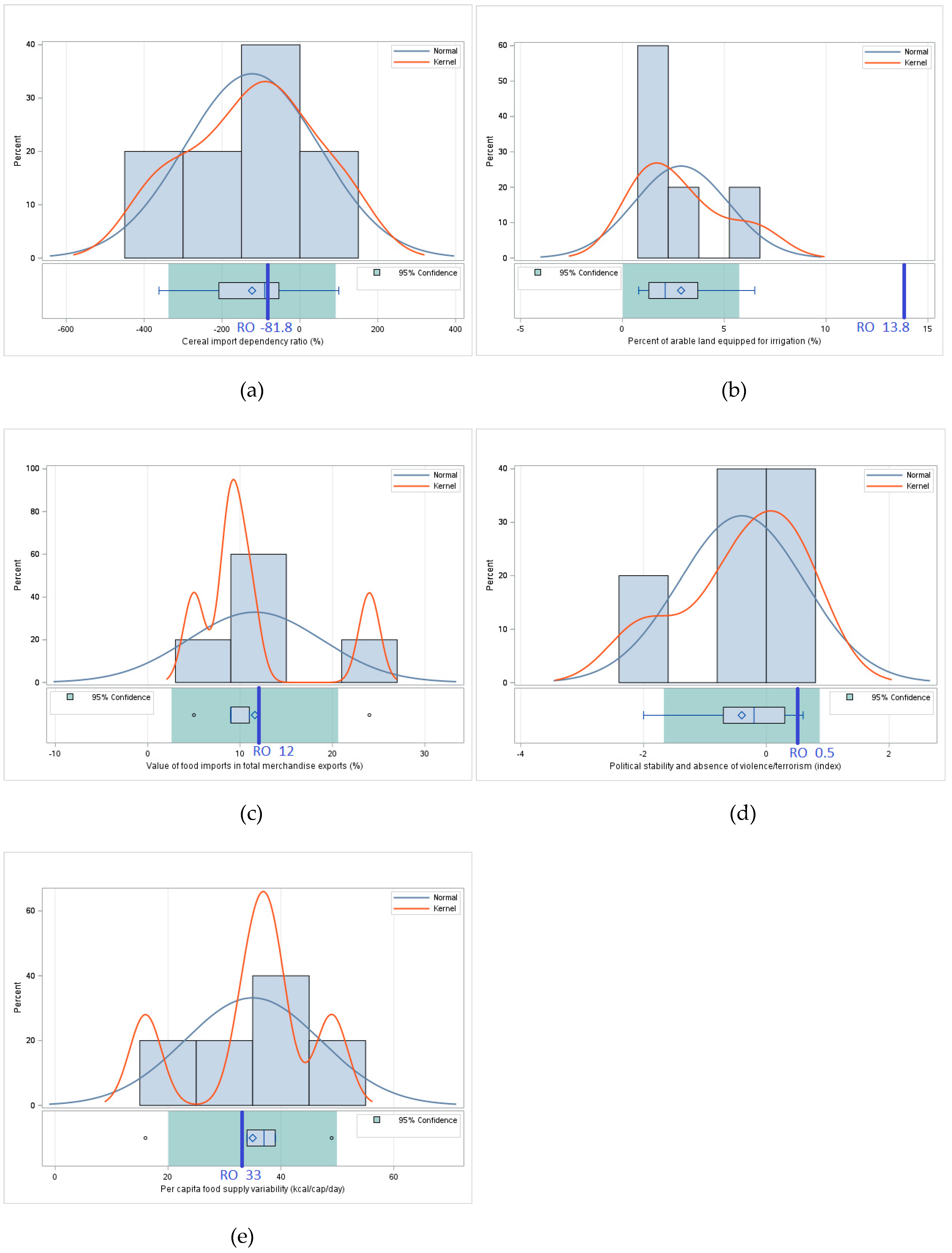

3.1.3. Stability – Comparative Analysis of the Values of Indicators Related to Stability of Food Security

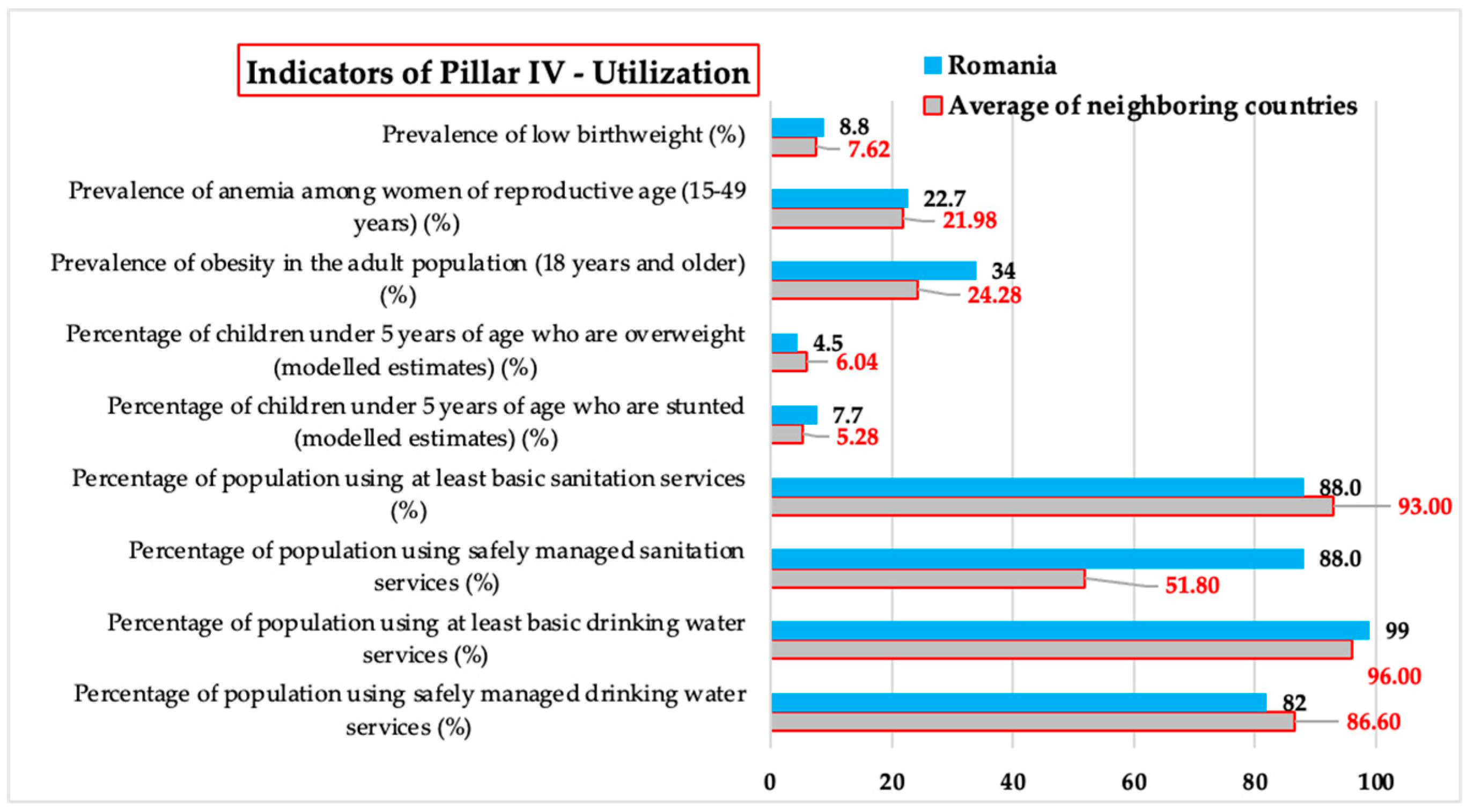

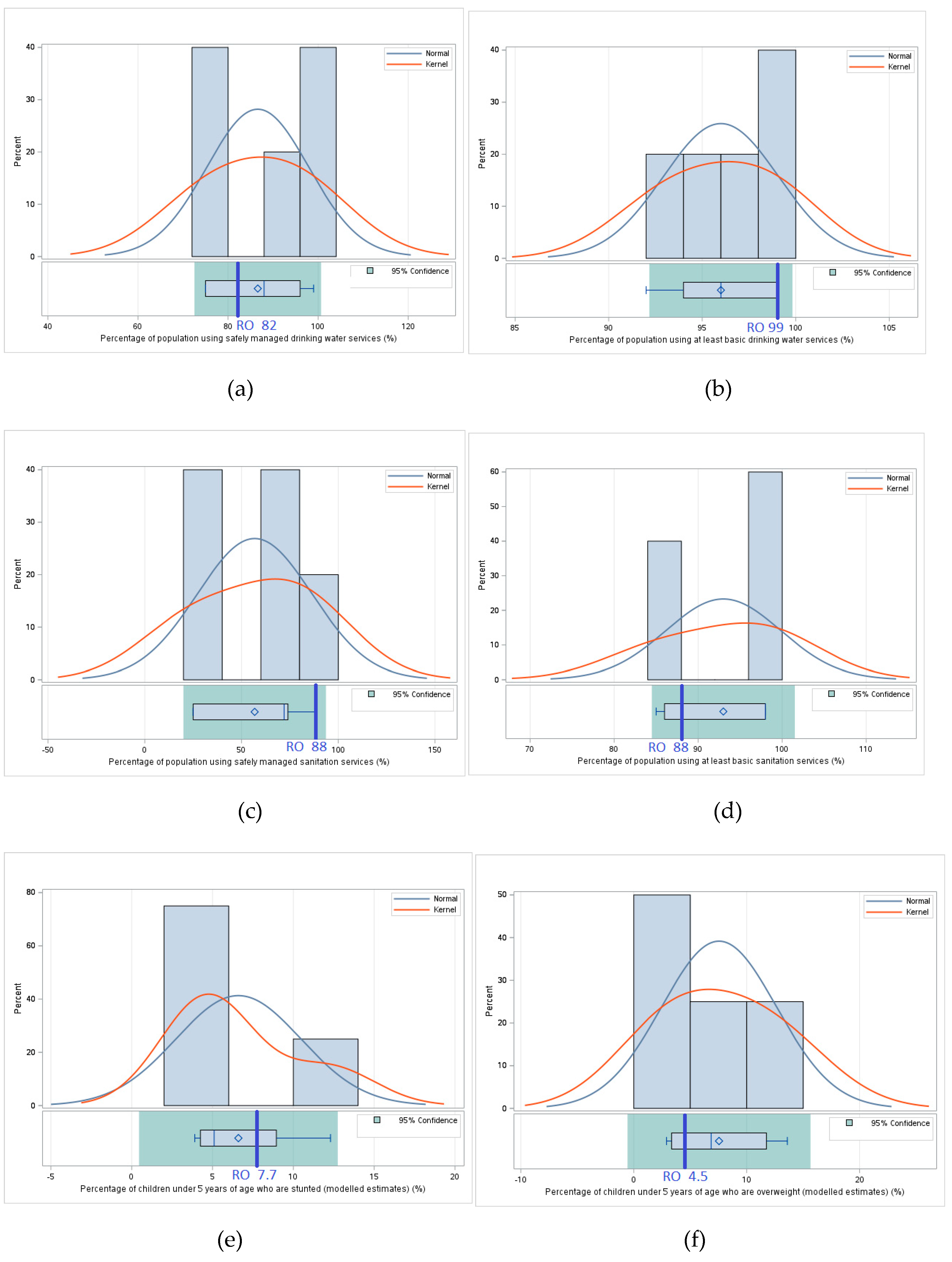

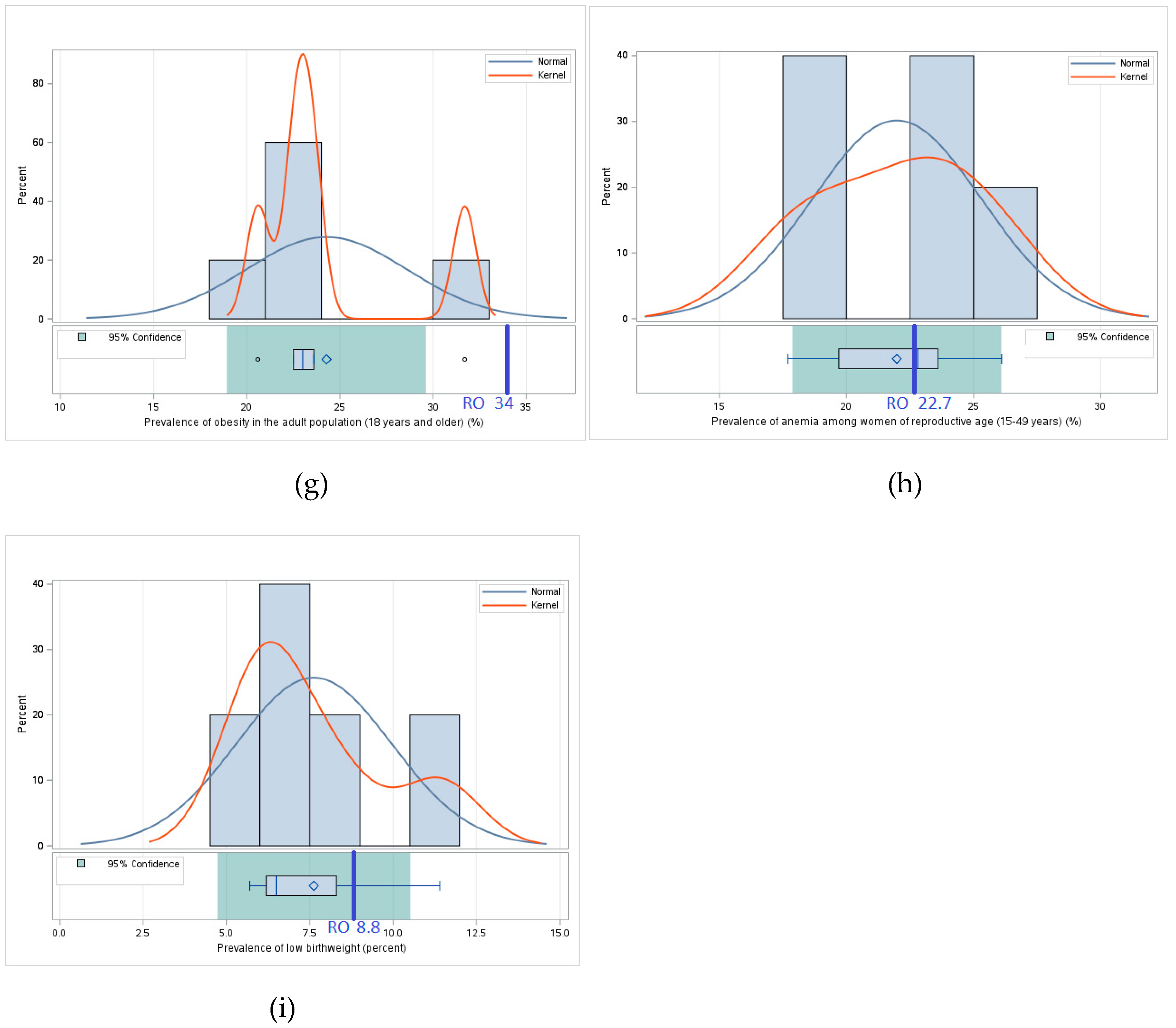

3.1.4. Utilization – Comparative Analysis of Values of Indicators Related to Food Utilization

| Indicators of Pillar IV - Utilization | Percentage of population using safely managed drinking water services (%) | Percentage of population using at least basic drinking water services (%) | Percentage of population using safely managed sanitation services (%) | Percentage of population using at least basic sanitation services (%) | Percentage of children under 5 years affected by wasting (%) | Percentage of children under 5 years of age who are stunted (modeled estimates) (%) | Percentage of children under 5 years of age who are overweight (modeled estimates) (%) | Prevalence of obesity in the adult population (18 years and older) (%) | Prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) (%) | Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among infants 0-5 months of age (%) | Prevalence of low birth weight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 96 | 99 | 74.0 | 86.0 | - | 5.6 | 3.8 | 20.6 | 23.6 | - | 11.4 |

| Hungary | 99 | 99 | 88.0 | 98.0 | - | 31.7 | 19.7 | - | 8.3 | ||

| Moldavia | 75 | 92 | - | 85.0 | - | 3.9 | 2.9 | 23 | 26.1 | - | 6.5 |

| Romania | 82 | 99 | 88.0 | 88.0 | - | 7.7 | 4.5 | 34 | 22.7 | - | 8.8 |

| Serbia | 75 | 96 | 25.0 | 98.0 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 9.9 | 22.5 | 22.8 | 23.6 | 6.2 |

| Ukraine | 88 | 94 | 72.0 | 98.0 | - | 12.3 | 13.6 | 23.6 | 17.7 | - | 5.7 |

3.2. Testing the Statistical Significance of the Differences Between Romania and The average of Neighboring Countries

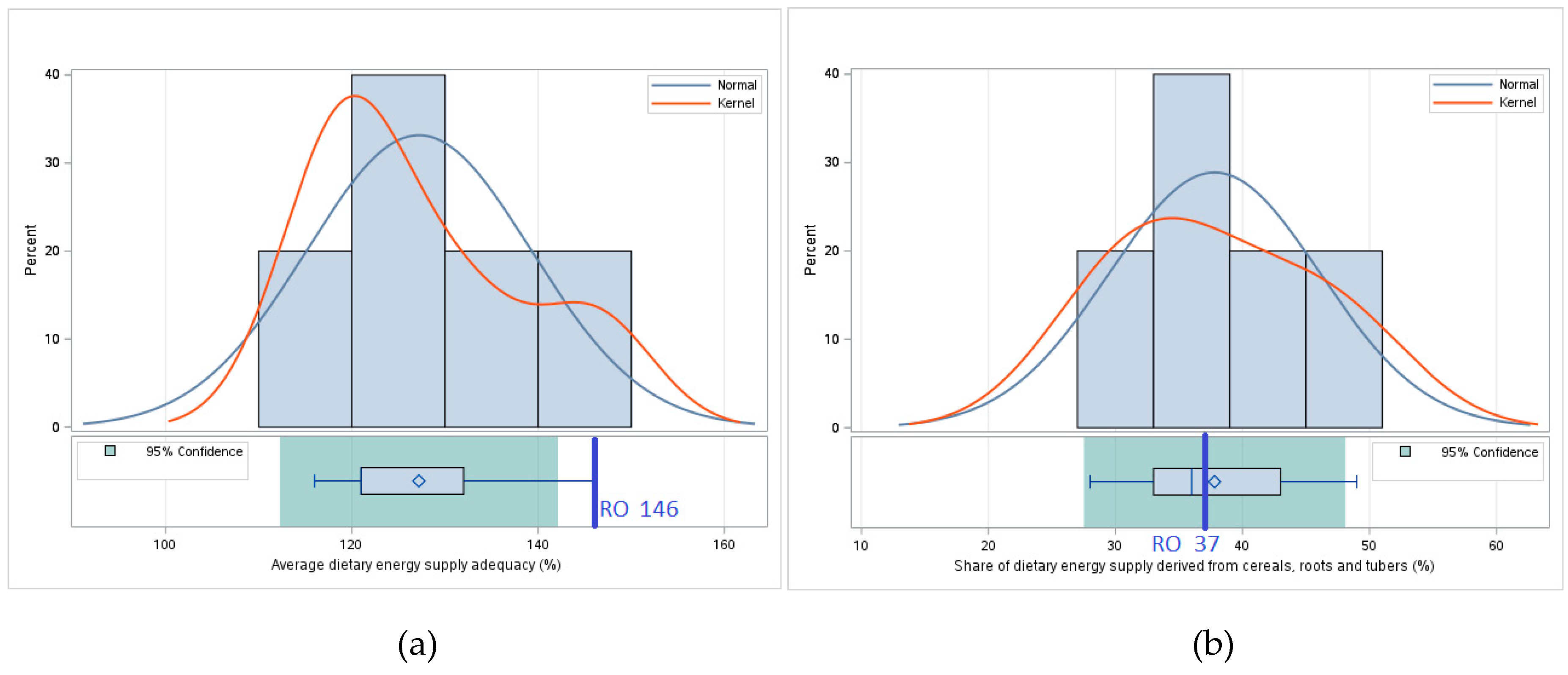

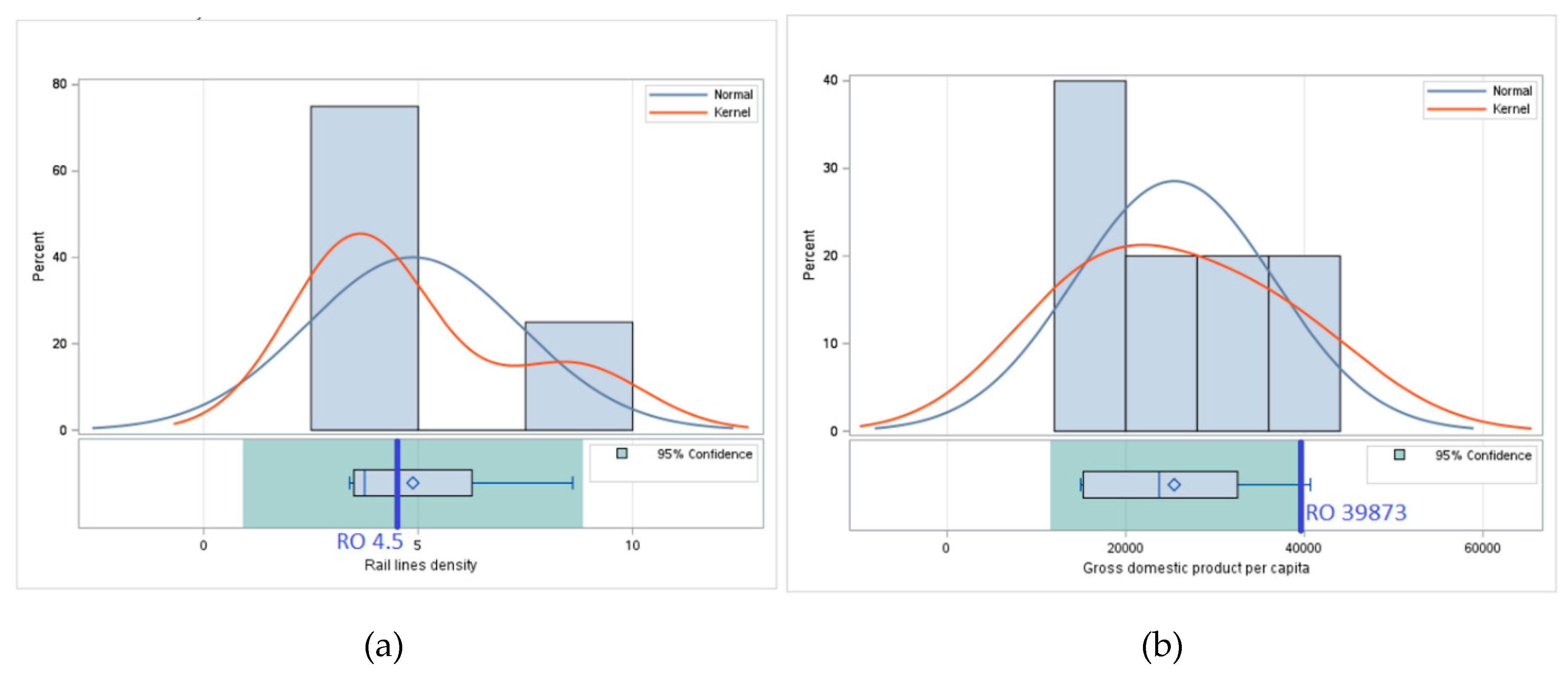

3.2.1. Availability – Statistical analysis – Determining the Significance of the Differences Observed in Food Availability Between Romania and the Average of Neighboring Countries

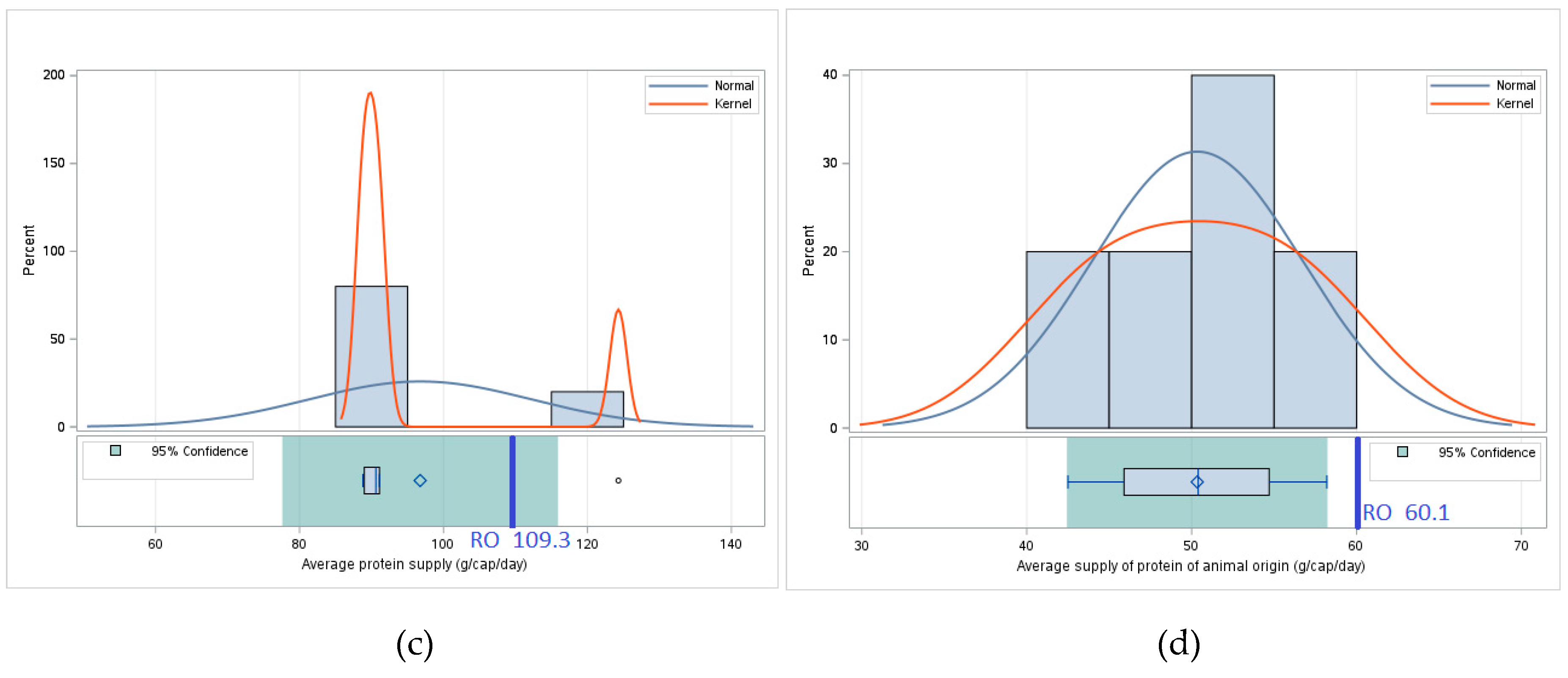

3.2.2. Access – Statistical Significance Testing – Applying Statistical Tests to Verify Whether Differences in Food Accessibility Are Statistically Relevant

3.2.3. Stability – Statistical Analysis – Assessing the Stability of Food Security Through Statistical Tests Applied to the Differences Between Romania and the Regional Average

3.2.4. Utilization – Statistical Analysis – Determining the Statistical Relevance of Differences Between Romania and the Regional Average

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis – Main Findings

4.2. Results of Statistical Significance Testing

4.3. Study Limitations and Shortcomings

4.5. Policy Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trasca, T.; Balan, I.; Mateoc-Sirb, N. Sustainable Food Security in Romania and Neighboring Countries: Trends, Challenges, and Solutions. In Proceedings of the 5th International Electronic Conference on Foods, 28–30 October 2024; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland https://sciforum.net/paper/view/19601. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024. Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms; FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO: Rome, Italy, 2024; https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd1254en. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The four pillars of food security. Food Security Cluster Handbook. 2023. Available online: https://handbook.fscluster.org/docs/231-the-four-pillars-of-food-security (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Trasca, T.I.; Ocnean, M.; Gherman, R.; Lile, R.A.; Balan, I.M.; Brad, I.; Tulcan, C.; Firu Negoescu, G.A. Synergy between the Waste of Natural Resources and Food Waste Related to Meat Consumption in Romania. Agriculture 2024, 14, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, I.M.; Gherman, E.D.; Gherman, R.; Brad, I.; Pascalau, R.; Popescu, G.; Trasca, T.I. Sustainable nutrition for increased food security related to Romanian consumers’ behavior. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Suite of Food Security Indicators. Available online: https://www.10.org/faostat/en/#data/FS (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Alexandri, C.; Luca, L.; Leonte, M.J. Providing Food Security in Romania. Challenges and Financing. Agricultural Economics and Rural Development 2023, 20, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, I.M.; Trasca, T.I. Reducing Agricultural Land Use Through Plant-Based Diets: A Case Study of Romania. Nutrients 2025, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babych, M.; Kovalenko, A. Food Security Indicators In Ukraine: Current State And Trends Of Development. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies 2018, 4, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, E.K.; Bachórz, A.; Bunzl, N.; Mincyte, D.; Parasecoli, F.; Piras, S.; Varga, M. The war in Ukraine and food security in Eastern Europe. Gastronomica 2022, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencia, A.D.; Balan, I.M. Reevaluating Economic Drivers of Household Food Waste: Insights, Tools, and Implications Based on European GDP Correlations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateoc Sirb, N.; Otiman, P.I.; Mateoc, T.; Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. Balance of Red Meat in Romania—Achievements and Perspectives. In From Management of Crisis to Management in a Time of Crisis. In Proceedings of the 5th Review of Management and Economic Engineering International Management Conference, Cluj Napoca, Romania, 2016; pp. 388–394, https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000385997200048. [Google Scholar]

- European Commsion. EU Actions to Enhance Global Food Security. N.d. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-actions-enhance-global-food-security_en (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- World Food Programme. Food Security Analysis. N.d. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/food-security-analysis (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Petroman, C.; Balan, I.M.; Petroman, I.; Orboi, M.D.; Banes, A.; Trifu, C.; Marin, D. National grading of quality of beef and veal carcasses in Romania according to “EUROP” system. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2009, 7, 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- Istudor, N.; Ion, R.A.; Sponte, M.; Petrescu, I.E. Food Security in Romania—A Modern Approach for Developing Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8796–8807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stef, D.S.; Rivis, A.; Trasca, T.I.; Pop, M.; Heghedus-Mindru, G.; Stef, L.; Marcu, A. The enrichment of bread with algae species. Sc. Papers-Series D-Animal Sc 2022, 65, 558–563. [Google Scholar]

- Stef, D.S.; Gergen, I.; Trasca, T.I.; Rivis, A.; Stef, L.; Cristina, R.T.; Druga, M.; Pet, I. Assessing the influence of various factors in antioxidant activity of medicinal herbs. Rom Biot Letters 2017, 22, 12842–12846. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, S. Food Security in Romania. SEA–Practical Application of Science 2015, 3, 83–92, https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=740609. [Google Scholar]

- Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. Suitability of a Quality Management Approach within the Public Agricultural Advisory Services. Qual.-Access Success 2014, 15, 81–84, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295468455_Suitability_of_a_quality_management_approach_within_the_public_agricultural_advisory_services. [Google Scholar]

- Petroman, I.; Caliopi Untaru, R.; Petroman, C.; Orboi, M.D.; Banes, A.; Marin, D.; Balan, I.; Negrut, V. The influence of differentiated feeding during the early gestation status on sows prolificacy and stillborns. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- Balan, I.M.; Gherman, E.D.; Brad, I.; Gherman, R.; Horablaga, A.; Trasca, T.I. Metabolic Food Waste as Food Insecurity Factor—Causes and Preventions. Foods 2022, 11, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasca, T.I.; Groza, I.; Rinovetz, A.; Rivis, A.; Radoi, B.P. The study of the behaviour of polyetetrafluorethylene dies for pasta extrusion comparative with bronze dies. Rev Mat Plast 2007, 44, 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chirescu, A.D.; Closca, A. Food security: past, present and future. The case of Romania. Rev Rom de Statistică 2023, Supl. 95. https://www.revistadestatistica.ro/supliment/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/5en_rrss_03_2023_ro.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, G. Sustainability of food safety and security in Romania. Challenges for the future national strategic plan. Competitiveness of Agro-Food and Environmental Economy 2019, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Food Security Update | World Bank Solutions to Food Insecurity. N.d. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-update?cid=ECR_GA_worldbank_EN_EXTP_search&s_kwcid=AL!18468!3!704632427690!b!!g!!food%20insecurity&gad_source=1 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. 2021; https://books.google.ro/books?hl=ro&lr=&id=CnE5EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR6&dq=food+security+indicators+Eastern+Europe&ots=cbyFg7JDDm&sig=XT2i5Dv0pEi_96eG7fcufO7R7dw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=food%20security%20indicators%20Eastern%20Europe&f=false. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing food and agricultural policies to make health diets more affordable. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. 2022; https://ngfrepository.org.ng:8443/bitstream/123456789/5358/1/cc0640en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Groza, I.; Trasca, T.I.; Rivis, A.; Radoi, B. Mathematical Model for Determining the Volume of Abrasive Susceptible of Levitation. Rev Chimie 2009, 60, 1347–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Santeramo, F.G. On the Composite Indicators for Food Security: Decisions Matter! Food Rev Internat 2014, 31, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.; Ecker, O. Rethinking the measurement of food security: from first principles to best practice. Food Sec 2013, 5, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, D.; Munisamy, G. Exploring the disparity in global food security indicators. Global Food Security 2021, 29, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLPE. Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8357b6eb-8010-4254-814a-1493faaf4a93/content (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Manikas, I.; Ali, B.M.; Sundarakani, B. A systematic literature review of indicators measuring food security. Agric & Food Secur 2023, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, C.F.; Stephens, E.C.; Kopainsky, B.; Jones, A.D.; Parsons, D.; Garrett, J. Food security outcomes in agricultural systems models: Current status and recommended improvements. Agricultural Systems 2021, 188, 103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostova, A.; Hutorov, A. Food security in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe: State and strategic directions of provision. Ekonomika APK 2023, 30, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, J.L.; Ruel, M.; Frongillo, E.A.; Harris, J.; Ballard, T.J. Measuring the food access dimension of food security: a critical review and mapping of indicators. Food and nutrition bulletin 2015, 36, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasca, T.I.; Groza, I.; Rinovetz, A.; Rivis, A.; Radoi, B.P. The study of the behaviour of polyetetrafluorethylene dies for pasta extrusion comparative with bronze dies. Rev. mat plast 2007, 44, 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rinovetz, A.; Rinovetz, Z.A.; Mateescu, C.; Trasca, T.I.; Jianu, C.; Jianu, I. Rheological characterisation of the fractions separated from pork lards through dry fractionation. Journ Food Agr Env 2011, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott, J.F.; Yohannes, Y. Dietary diversity as a food security indicator. FCND Discussion Paper 136, 2022; https://hdl.handle.net/10568/155730. [Google Scholar]

- Rumyk, I. Modeling the impact of economic indicators on food security. Ec Fin Manag Rev 2021, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubanych, O.; Vavřina, J.; Polák, J. Development of financial performance of food retailers as an attribute behind the increase of food insecurity in selected Central and Eastern European countries. Investm Manag Financ Innov 2023, 20, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allee, A.; Lynd, L.R.; Vaze, V. Cross-national analysis of food security drivers: comparing results based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale and Global Food Security Index. Food Sec. 2021, 13, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha-Khasnobis, B.; Acharya, S.S.; Davis, B. (Eds.) Food security: Indicators, measurement, and the impact of trade openness; OUP: Oxford, 2007; https://books.google.ro/books?hl=ro&lr=&id=2QxREAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=food+security+indicators&ots=7WAGV2u9dz&sig=SeA9T0dv78DewJ1xgffEohWg-kw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=food%20security%20indicators&f=false. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, I.; Redman, M.; Czekaj, M.; Tyran, E.; Grivins, M.; Sumane, S. Small-scale farming and food security–policy perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe. Global Food Security 2021, 29, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasevic, I.; Kovačević, D.B.; Jambrak, A.R.; Szendrő, K.; Dalle Zotte, A.; Prodanov, M.; Djekic, I. Validation of novel food safety climate components and assessment of their indicators in Central and Eastern European food industry. Food control 2020, 117, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, H.; Myszkowska-Ryciak, J. Food Insecurity in Central-Eastern Europe: Does Gender Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- United Nations. Final List of Proposed Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11803Official-List-of-Proposed-SDG-Indicators.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Kuiper, M.; Cui, H.D. Using food loss reduction to reach food security and environmental objectives–A search for promising leverage points. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campi, M.; Dueñas, M.; Fagiolo, G. Specialization in food production affects global food security and food systems sustainability. World Development 2021, 141, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PILLARS and suites of indicators |

Year/Annual average from the range |

|---|---|

| Pillar I - Availability | |

| Average dietary energy supply adequacy | 2021-2023 |

| Share of dietary energy supply derived from cereals, roots and tubers | 2020-2022 |

| Average protein supply | 2020-2022 |

| Average supply of protein of animal origin | 2020-2022 |

| Pillar II - Access | |

| Rail lines density (total route in km per 100 square km of land area) | 2021 |

| Gross domestic product per capita (in purchasing power equivalent) | 2022 |

| Prevalence of undernourishment, 3-year averages | 2021-2023 |

| Prevalence of undernourishment, yearly estimates | 2021-2023 |

| Prevalence of severe food insecurity in the total population, 3-year averages | 2021-2023 |

| Prevalence of severe food insecurity in the total population, yearly estimates | 2021-2023 |

| Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the total population, 3-year averages | 2021-2023 |

| Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the total population, yearly estimates | 2021-2023 |

| Pillar III - Stability | |

| Cereals imports dependency rate | 2020-2022 |

| Percent of arable land equipped for irrigation | 2020-2022 |

| Value of food imports over total merchandise exports | 2020-2022 |

| Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism | 2022 |

| Per capita food supply variability | 2023 |

| Pillar IV - Utilization | |

| People using at least basic drinking water services | 2022 |

| People using safely managed drinking water services | 2022 |

| People using at least basic sanitation services | 2022 |

| People using safely managed sanitation services | 2022 |

| Percentage of children under 5 years of age affected by wasting | 2019 |

| Percentage of children under 5 years of age who are stunted | 2022 |

| Percentage of children under 5 years of age who are overweight | 2022 |

| Prevalence of obesity in the adult population (18 years and over) | 2022 |

| Prevalence of anemia in women of reproductive age (15-49 years) | 2019 |

| Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among infants aged 0-5 months | 2019 |

| Prevalence of low birthweight | 2020 |

| Indicators of Pillar I - Availability |

Average dietary energy supply adequacy (%) | Share of dietary energy supply derived from cereals, roots and tubers (%) | Average protein supply (g/cap/day) | Average supply of protein of animal origin (g/cap/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 121 | 33 | 89.0 | 50.4 |

| Hungary | 132 | 28 | 90.6 | 54.7 |

| Moldavia | 121 | 36 | 88.8 | 42.5 |

| Romania | 146 | 37 | 109.3 | 60.1 |

| Serbia | 146 | 49 | 124.3 | 58.2 |

| Ukraine | 116 | 43 | 91.1 | 45.9 |

| Indicators of Pillar II - Access | Rail line density (total route in km per 100 square km of land area) | Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, PPP, (constant 2017 international $) | Prevalence of undernourishment (%) | Number of people undernourished (mil.) | Prevalence of severe food insecurity in the total population (%) | Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the total population (%) | Number of severely food insecure people (mil.) | Number of moderately or severely food insecure people (mil.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 3.6 | 32511.8 | <2.5 | - | 2.5 | 14.8 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Hungary | 8.6 | 40683.9 | <2.5 | - | 3.6 | 15.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Moldavia | 3.4 | 15229.5 | <2.5 | - | 5.3 | 24.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Romania | 4.5 | 39872.5 | <2.5 | - | 7.1 | 19.1 | 1.4 | 3.8 |

| Serbia | 3.9 | 23741.2 | <2.5 | - | 3.0 | 13.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| Ukraine | - | 14950.5 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 5.3 | 31.0 | 2.1 | 12.4 |

| Indicators of Pillar III - Stability |

Cereal import dependency ratio (%) | Percent of arable land equipped for irrigation (%) | Value of food imports in total merchandise exports (%) | Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism (index) | Per capita food supply variability (kcal/cap/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | -208.0 | 1.3 | 11 | 0.3 | 16 |

| Hungary | -90.4 | 2.1 | 5 | 0.6 | 49 |

| Moldavia | 100.0 | 6.5 | 24 | -0.7 | 37 |

| Romania | -81.8 | 13.8 | 12 | 0.5 | 33 |

| Serbia | -53.9 | 0.8 | 9 | -0.2 | 39 |

| Ukraine | -361.9 | 3.7 | 9 | -2 | 34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).