1. Introduction

Microencapsulation of bioactive compounds, such as antioxidants, vitamins, flavors, and essential oils, is a key strategy to improve their stability and effectiveness. It protects them from environmental factors such as heat, humidity, and light, as well as enhancing their bioavailability and controlled release. Such a technique finds applications in various industries, including food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals [

1,

2]. Complex coacervation, an efficient method of encapsulation, is based on the formation of a polyelectrolyte complex by electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged polymers. This process occurs under specific conditions of pH, ionic strength, and temperature [

3]. Complex coacervation using biopolymers is receiving more and more attention due to its ability to form microcapsules with desirable properties such as high loading efficiency and tailored release profiles. One of these compounds of interest is

-tocopherol, a lipophilic antioxidant essential for human health and for its preservative properties. However, this active molecule exhibits low solubility in aqueous solutions and is extremely prone to degradation when exposed to environmental factors like high temperatures, light, and oxygen, which limits its application. Consequently, innovative methods must be developed to stabilize this sensitive molecule [

4].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in using non-animal biopolymers, including plant-based proteins [

5,

6,

7]. Nevertheless, some of them may be susceptible to cause allergic reactions and may not be suitable for all applications.

Recently, fungal chitosan (FC) and gum Arabic (GA) were studied as encapsulating agents, owing to their biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and functional versatility [

8,

9,

10]. Chitosan is also recognized for its antimicrobial and antioxidant properties [

11,

12]. Thus, complex coacervation using these biopolymers offers a promising approach to encapsulate and protect

-tocopherol into multifunctional microcapsules. However, reaching high encapsulation efficiencies and enhancing the stability of the resulting coacervates remains a challenge, with the latter rarely being studied in the literature.

Reticulation, a process consisting in the formation of cross-links between polymer chains, can significantly improve the encapsulation efficiency and stability of microcapsules. Aldehydes and enzymes have been studied in various studies; however, the high toxicity of aldehydes and the high cost of enzymes require the research of safe, natural, and economic alternatives [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Tannic acid (TA), a natural polyphenol, has been recognized for its antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory qualities, making it an excellent choice for the development of multifunctional microcapsules [

17]. Although it has been explored as a cross-linking agent to enhance the structural integrity and functional properties of coacervates [

18,

19,

20], its effect on the stability of bioactive molecules remains understudied. Moreover, TA has never been used as a cross-linker for FCGA coacervates.

For the first time in the literature, we aimed to investigate the potential of TA as a cross-linking agent for FCGA coacervates in improving the stability of -tocopherol through complex coacervation. By evaluating the encapsulation efficiency, yield, morphological and rheological properties, and stability of encapsulation of the resulting microcapsules by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and storage stability, this research seeks to contribute to the development of robust and multifunctional delivery systems for sensitive bioactive compounds, with potential applications in functional foods, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Impact of the Cross-Linking Agent on the Properties of Coacervates

The impact of TA on FCGA coacervates on yield, encapsulation efficiency and active loading is displayed

Table 1.

The yield of complex coacervates was not significantly affected by the addition of TA (≥ 69%). Nevertheless, a decline was observed at a concentration of 2% TA, potentially attributable to the presence of unbound TA in the solution. The active loading, referring to the concentration of TOCO in the microcapsules, decreases as the concentration of TA increases, as expected. By increasing the concentration of TA in the formulations, the total quantity of TOCO was decreased as a result of a dilution effect.

The encapsulation efficiency (EE) ranged from 79.73 to 93.89%, and it is interesting to note that raising the concentration of TA initially led to a significant decrease in EE. However, the efficiency was further improved when 2% TA was used. Koupantsis et al. (2016), Zhang et al. (2011) and Alexandre et al. (2019) also observed a comparable pattern, slightly improving the EE with the use of TA as cross-linking agent in various complex coacervate systems: milk proteins-carboxymethylcellulose, gelatin-GA, and cashew gum-gelatin, respectively [

18,

21,

22].

The increase in encapsulation efficiency with the addition of TA can be attributed to the enhanced formation of the polyelectrolyte complex through hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions between TA and the FCGA matrix [

14,

18]. These interactions result in a more compact coacervate structure and greater entrapment of TOCO. If the encapsulation of TOCO by chitosan and GA coacervates has never been described elsewhere in the literature; these results can be compared to results obtained on other coacervates. As an illustration, the encapsulation of TOCO by complex coacervation has been studied a few times in the literature using chitosan (Ch) with sodium lauryl ether sulfate [

13] or with soy protein isolate [

23], achieving up to 73.2 and 64.8% of EE, respectively. The variations observed can be attributed to the molecular weight of the chitosan (between 50 and 190 kDa), the specific parameters selected for the complex coacervation process (including the total amount of biopolymers and the concentration of vitamin E), or the drying method. The current study involved the selection of a low molecular weight FC (39 kDa), which led to increased mobility of the biopolymer chain. Consequently, this could have promoted interactions with other compounds. The study conducted by [

24] achieved a higher encapsulation efficiency (ranging from 90.4% to 100%) for vanillin and limonene by using FCGA complex coacervates that were cross-linked with TA. Nevertheless, the coacervates were formulated using surfactants (Span 85 and polyglycerol polyricinoleate), and no investigation was conducted to compare them to coacervates without surfactant. The encapsulation of lavender oil using gelatin and GA was investigated by Xiao et al. (2014), which investigated the use of various cross-linking agents (TA, glutaraldehyde, and transglutaminase) [

14]. Although the EE remained constant regardless of the cross-linker used, there was a notable decrease compared to uncross-linked coacervates due to the oil’s volatility. Therefore, TA represents an effective and safe alternative for the cross-linking of complex coacervates.

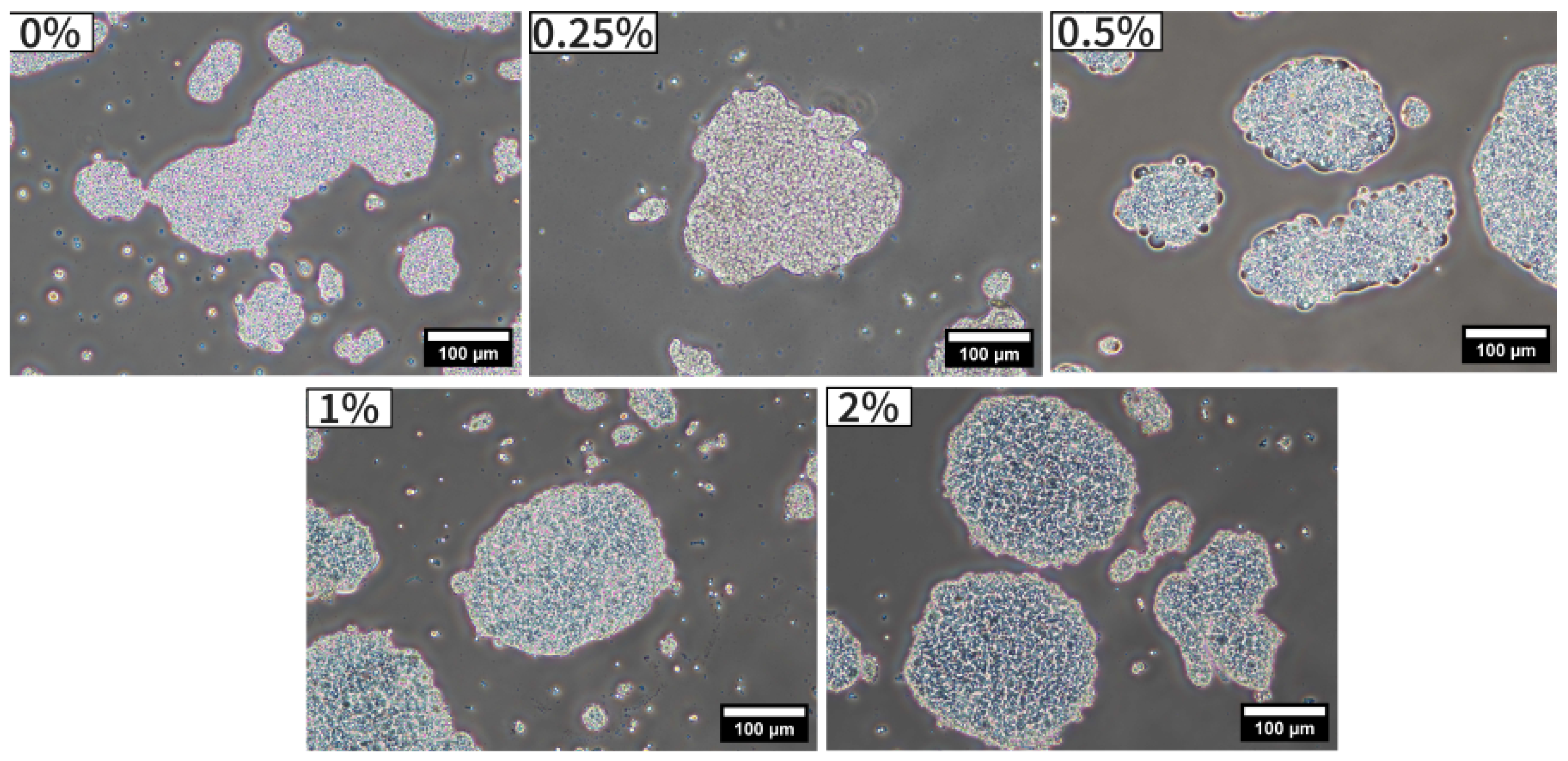

2.2. Morphology of Coacervates

Particle size analysis and phase-contrast microscopy were used to assess the morphological characteristics of FCGA coacervates. The particle size of complex coacervates was significantly influenced by the addition of TA, as shown in

Table 2. The size of the microcapsules increased as the concentration of TA increased from 0% to 0.5% due to interactions with the polysaccharides. Nevertheless, a subsequent increase in TA led to a reduction in the size of the particles. A similar behavior was reported by Zhang et al. (2011) and Guo et al. (2022) and was attributed to the saturation of the binding sites of the biopolymers [

21,

25]. Thus, the maximum of cross-linking is achieved when all binding sites of TA are involved. Increasing the concentration results in an excess of TA, causing an increase in electrostatic repulsions, and, consequently, leading to the size reduction of the resulting aggregates.

Observations of complex coacervates by phase-contrast microscopy are shown in

Figure 1. As clearly visible on all micrographs, complex coacervates consisted in the aggregation of oil droplets entrapped in microgels consisting of biopolymer matrix with irregular shapes. Although the overall microstructure of the complex coacervates appeared unaffected by the addition of TA, a slight increase in the contrast of the coacervate layer around the oil droplets was observed and could be attributed to their higher thickness, in agreement with the literature [

25].

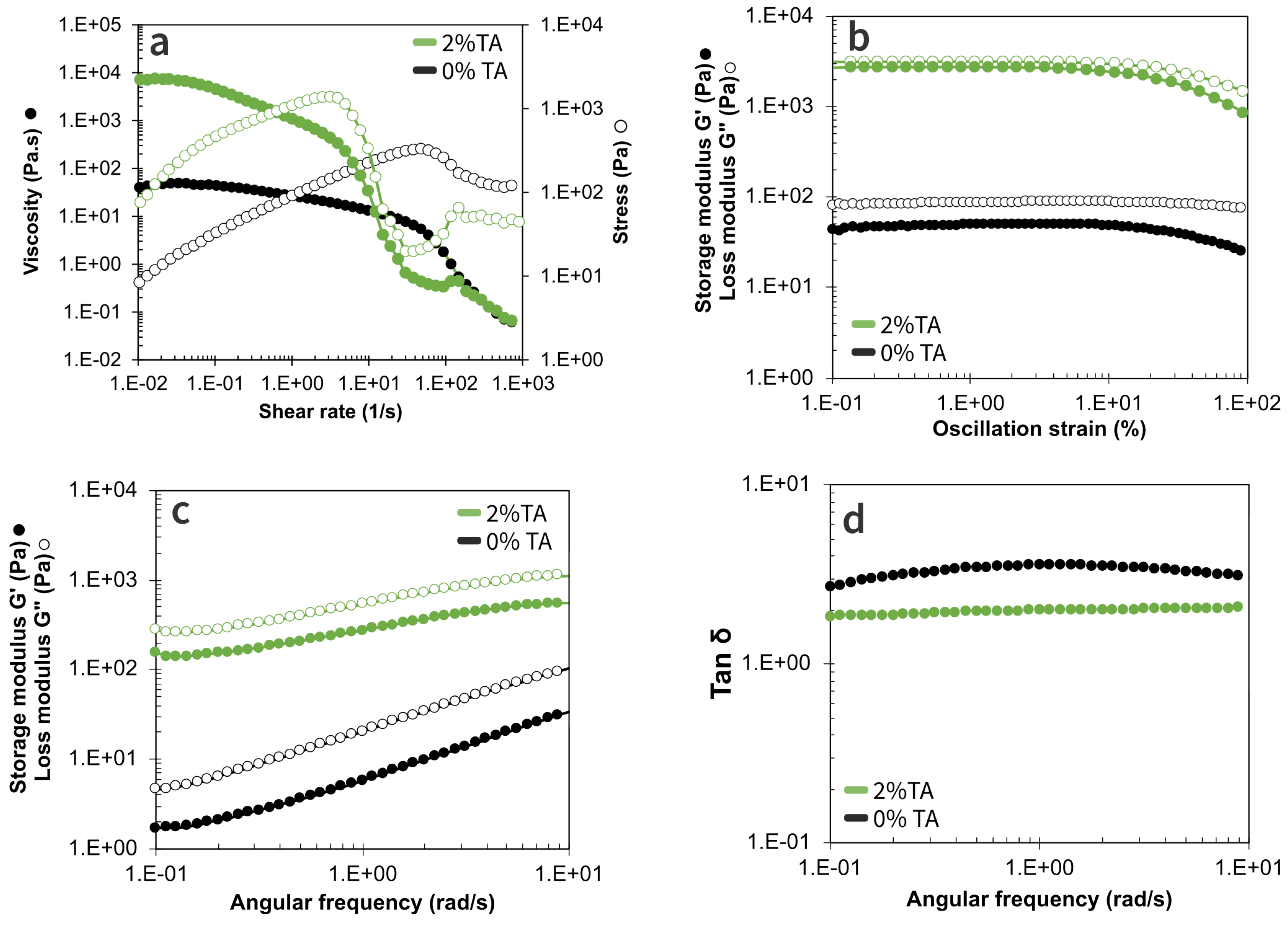

2.3. Rheological Properties of Complex Coacervates

In order to understand the structural differences between complex coacervates, whether cross-linked with TA, both flow and oscillation tests were conducted (

Figure 2). All samples displayed a shear thinning behavior, with an increase in the shear rate to approximately 10 s

−1 (

Figure 2a). Moreover, TA addition led to viscosity increasing that can be attributed to enhanced intermolecular bonding [

26]. In addition, both samples exhibited a sharp viscosity loss at high shear rate, as the latter causes structural breakdown of polyelectrolyte complexes, as reported in previous studies [

27,

28,

29]. To go further, it is striking that microgels disruption takes place at lower shear rates when the coacervates were cross-linked with TA if compared to non-cross-linked ones (5 s

−1 instead of 47 s

−1). This demonstrates that cross-linking tends to make microgels more fragile when submitted to strain. This is perfectly corroborated by results of LVER test performed by strain sweep measurements (

Figure 2b). This LVER domain is characterized by constant viscoelastic parameters in a given strain range; this can also be considered as the material’s sensitivity to deformation. As visible on the graphs, cross-linked coacervates had a smaller LVER, with an oscillation strain of up to 8.0%, compared to 25.3% for non-cross-linked ones. Furthermore, while both samples displayed a liquid-viscoelastic behavior, both modulus were significantly higher for reticulated coacervates. The findings suggest that the development of a cross-linked structure in coacervates decreases their deformability due to a stronger molecular network that limits molecular mobility; this outcome aligns with existing literature on different types of cross-linked coacervates such as gelatin-GA systems [

30].

Finally, frequency sweep tests were conducted using a constant strain (1%) chosen within the LVER. For every complex coacervate, both the storage modulus (G’) and the loss modulus (G") increased as the frequency increased from 0.1 to approximately 10 rad.s

−1, with G" > G’ for all frequencies (

Figure 2c). Coacervates that were reticulated with 2% TA exhibited a reduced sensitivity of tan

to frequency changes. This phenomenon was also reported by Anvari et al. (2016) in their study on the dynamic behavior of complex coacervates formed by fish gelatin and GA reticulated with TA [

30]. This behavior indicates the development of more robust intermolecular interactions and a more resilient molecular network.

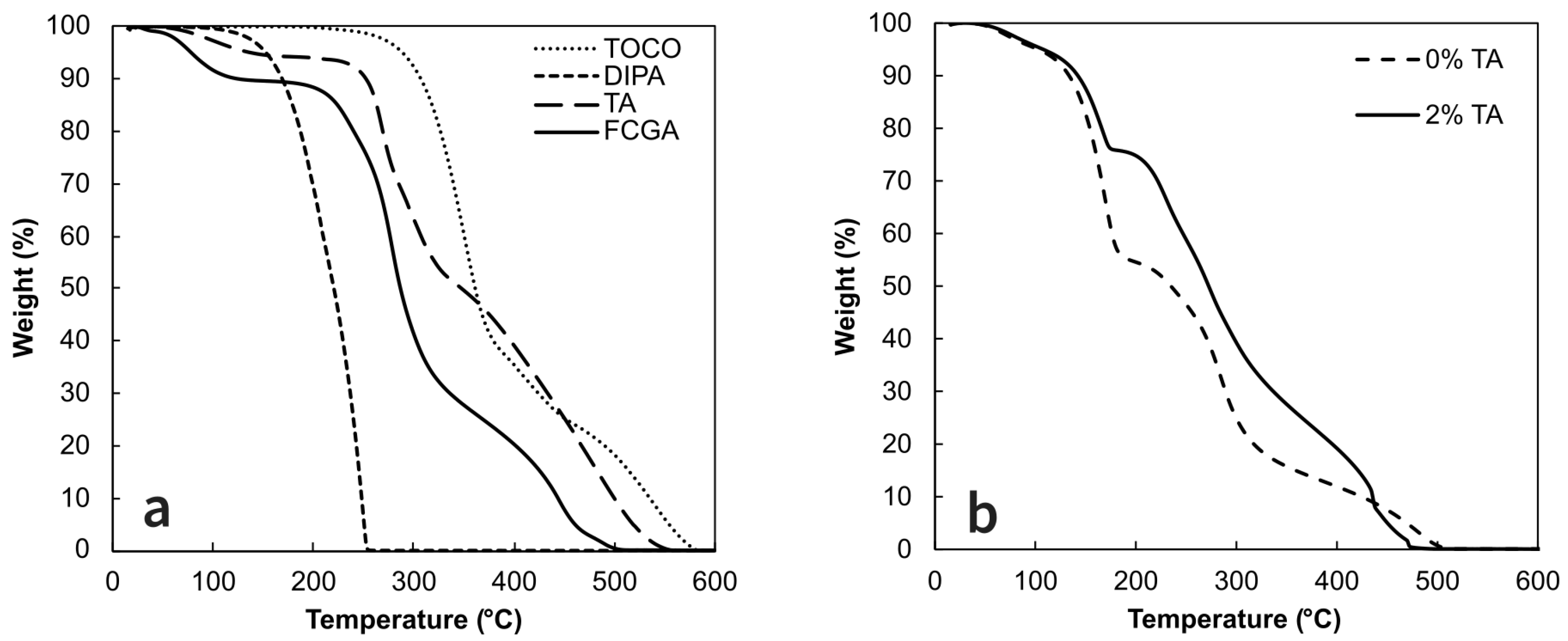

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA was performed on freeze-dried coacervates and starting materials to investigate their thermal stability (

Figure 3). Pure TOCO and TA presented high thermal decomposition temperatures of 350 °C and 268 °C, respectively. The carrier oil, DIPA, showed a one-step degradation process starting around 130 °C corresponding to its boiling point (110 °C). For empty coacervates FCGA, a 3-step degradation process was observed:

The first one, which occurs at temperatures below 125 °C, is related to water desorption and evaporation.

The second one, corresponds to polysaccharides decomposition between 250-400 °C.

Finally, above 400 °C, the decomposition of the residual carbonated group was observed.

These results are in agreement with those previously reported in the literature for pure TOCO [

31], and for individual polysaccharides Ch and GA and the resulting coacervates [

32,

33,

34].

At the same time, the TOCO microcapsules exhibit a degradation process consisting of four steps (

Figure 3b). The initial step, related to the loss of water below 125 °C, allows the determination of the moisture content without significant variations: the latter being 7.2% for coacervates without TA and 6.0% for the cross-linked ones. Then, the next weight loss occurs within the 130-200 °C range, mainly due to the degradation of the carrier oil. However, the reticulation of complex coacervates decreases the mass loss by 30% within this temperature range. In the third step (from 200 to 300 °C), the polysaccharides’ decomposition is observed, followed by the degradation of TOCO and the carbonated residues.

Figure 3b illustrates that the addition of 2% of TA significantly enhance the thermal stability of microparticles, thus efficiently preventing the degradation of DIPA and, consequently, of TOCO. Alexandre et al. (2019) also reported an increase in the thermal stability of the cross-linked cashew gum-gelatin coacervates with TA [

22]. Thus, based on the present results, it is obvious that cross-linking complex coacervates significantly improves their thermal stability, making them even more suitable for high-temperature processes.

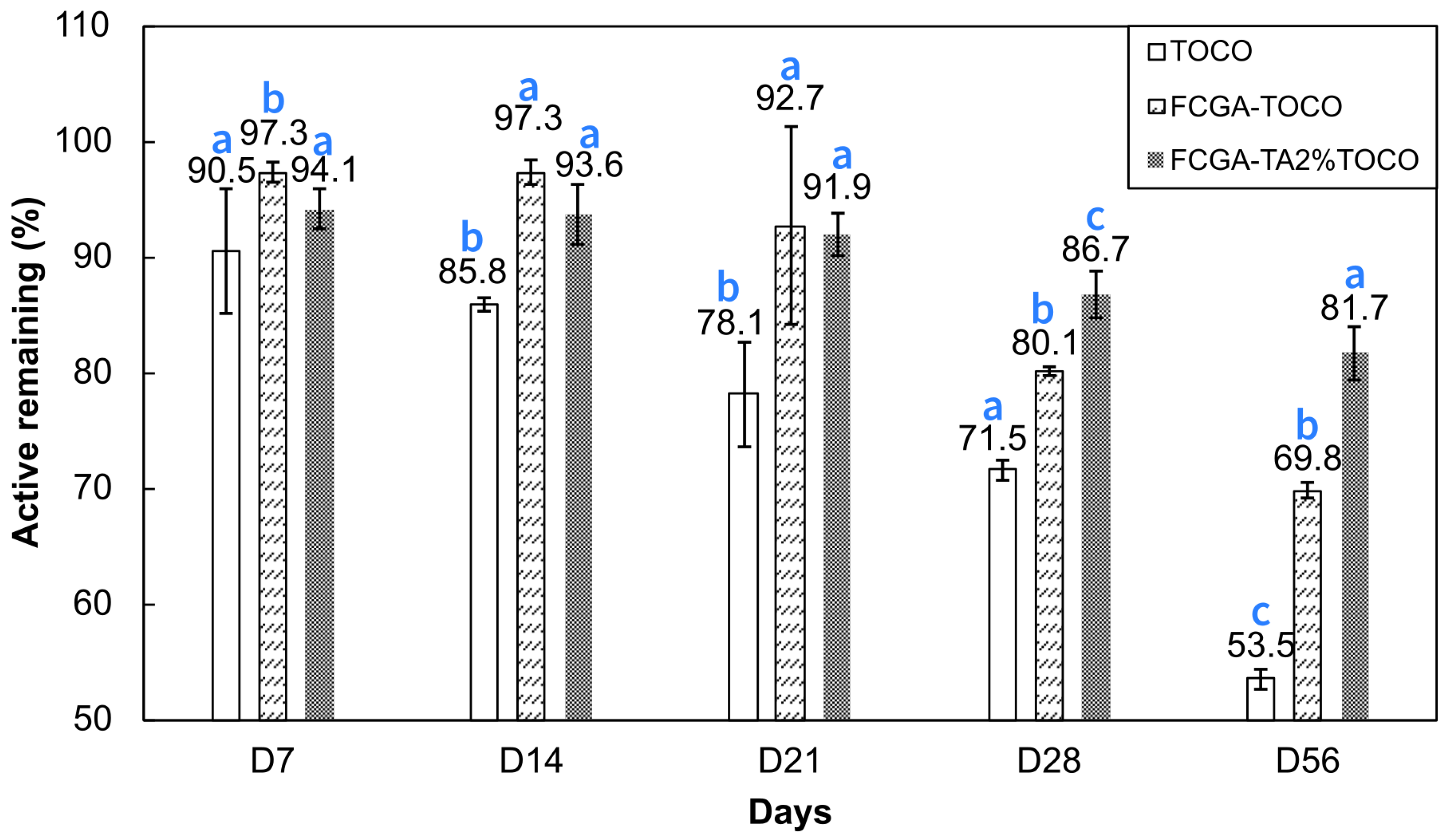

2.5. Storage Stability of Complex Coacervates

The storage stability of encapsulated TOCO was evaluated for two months in accelerated conditions at 40 °C in order to investigate microcapsules stability over time, under accelerated conditions; aging test was performed over 2 months with monitoring active loading (

Figure 4). Results clearly indicate that TOCO retention was significantly enhanced over time through the complex coacervation process. Despite the fast degradation of pure TOCO, with only 85.8% remaining after two weeks, its encapsulation resulted in 93.6-97.3% of retained TOCO. This phenomenon is even more marked as the test duration increases. After a period of two months, the cross-linked coacervates demonstrated significantly improved results, with 81.7% of TOCO retained. In comparison, only 53.5% of pure TOCO and 69.8% of encapsulated TOCO without reticulation were observed, respectively. Although some studies have suggested that reticulated coacervates own a higher retention rate [

19,

25,

35], the storage stability of encapsulated TOCO by complex coacervation was not examined in the literature, making this study the first of its kind.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Fungal chitosan (FC) of deacetylation degree: 80.9 ± 0.1% (determined by conductimetric dosing) and average viscosimetric molecular weight: 39 ± 1 kDa was purchased from Kraeber & Co GmbH (Ellerbek, Germany) and gum Arabic

Senegal (GA) (average viscosimetric molecular weight: 393 ± 23 kDa) was kindly gifted by Alland&Robert (France). The average molecular weight of both polymers was determined using intrinsic viscosity measurements using Mark-Houwink-Sakurada parameters reported in the literature by Kasaai et al. (2007) for chitosan [

36] and by Gomes-Diaz et al. (2008) and Idris et al. (1998) for gum Arabic [

37,

38].

-tocopherol (TOCO)

and tannic acid (TA) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Germany), and diisopropyl adipate (DUB DIPA) was kindly provided by Stéarinerie Dubois (France). Hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and glacial acetic acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (USA). Absolute ethanol (EtOH) was purchased from Brabant (France). All solutions and emulsions were prepared using demineralized water.

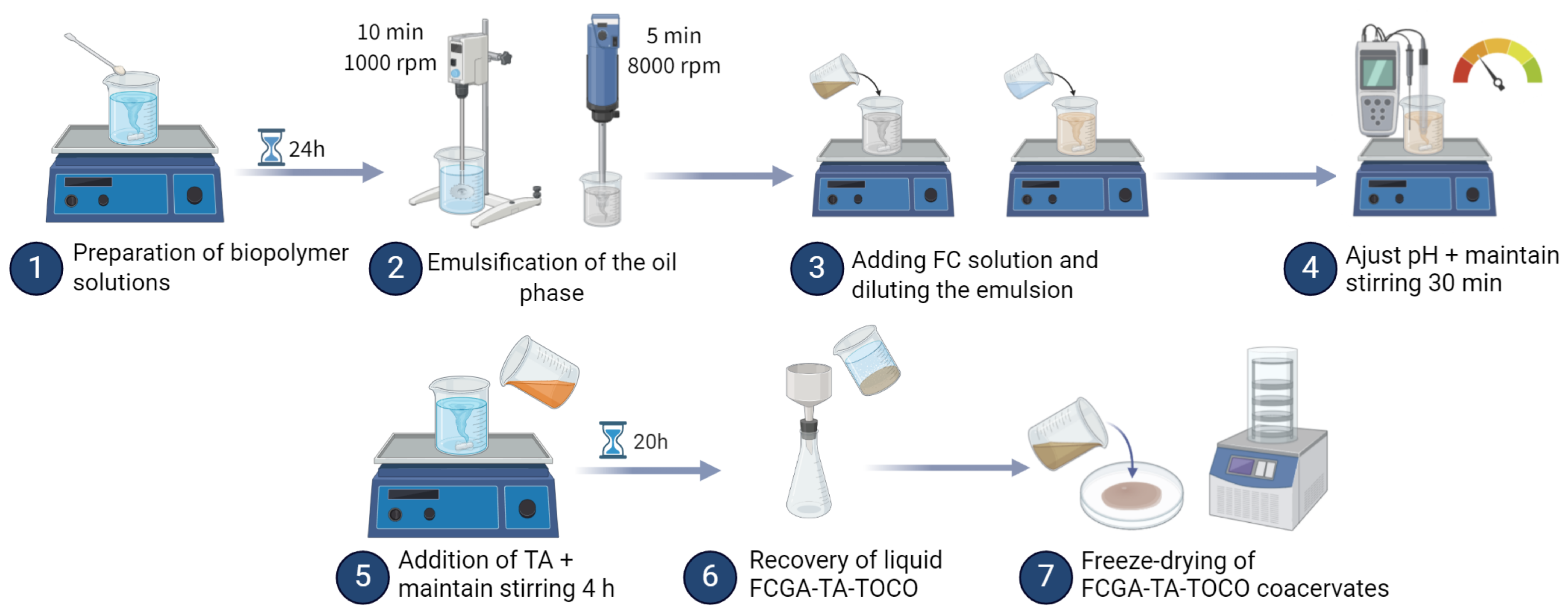

3.2. Preparation of Complex Coacervates

Biopolymer stock solutions were prepared by dissolving 5%wt of FC in acetic acid (1%v/v) and 10%wt of GA in deionized water under magnetic stirring for 4 and 2 hours, respectively. Resulting biopolymer solutions were kept overnight at 4 °C to ensure complete hydration of the polymers. A solution of 12%wt of TA was prepared at room temperature before running the experiment.

Complex coacervates were prepared in the FC:GA 1:4 w/w ratio with a biopolymer:oil ratio of 1:1, as follows. The concentration of biopolymers in the final mixture was maintained at 2.5% w/w. The oil phase, consisting in 10%wt of -tocopherol dissolved in diisopropyl adipate, was added to a GA 5 % w/w aqueous solution under stirring using a VMI Turbotest (Turbotest, VMI-mixing, La-Roche-sur-Yon, France) equipped with a defloculator turbine (diameter of 35 mm) operating at 1000 rpm for 10 min followed by an IKA Ultra-turrax rotor-stator device at 8000 rpm for 5 min to form an emulsion. The FC solution (5 % w/w) was gradually added to this latter emulsion under magnetic stirring. After 10 minutes, the entire FCGA-TOCO solution was diluted to achieve a total polymer solid content of 5%wt. Subsequently, magnetic stirring was conducted for an additional 10 minutes. After adjusting the pH to the optimum level (4.8) using a HCl solution (2 mol/L), magnetic stirring was maintained for another 30 minutes. An aqueous solution of TA (12%wt) was added to reach a total TA content of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2% (w/w), and the pH was then readjusted to 4.8. Magnetic stirring was maintained for 4 hours. The resulting mixture was then left at room temperature for 20 hours more. After 24 hours, the mixture was filtered through Whatman no. 42 filter paper using a Büchner funnel. Finally, the recovered coacervates were then placed into Petri dishes and freeze-dried for 4 hours at -96 °C to obtain a powder by grinding the frozen coacervates. The resulting coacervates were stored at 4 °C until further analyses.

3.3. Characterization of Complex Coacervates

3.3.1. Encapsulation Efficiency, Yield, and Loading Capacity

In order to assess the encapsulation efficiency (EE) and active loading (AL) of complex coacervates, 0.1 g of sample was weighed in a plastic tube with 10 mL of pure EtOH (in triplicate). The solution was placed in an ultrasonic bath (VWR Ultrasonicator) for 10 min at room temperature to extract the encapsulated -tocopherol. The solution was then filtered using a 0.45 µm pore-sized filter in cellulose acetate. A standard calibration curve (R² = 0.999) was used, with the -tocopherol concentration determined by calculating the area under the UV detection peak after separation by LC-MS.

The concentration of -tocopherol in coacervates was determined using an LC-MS Agilent 1200 (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with an C18 XDB 5 µm 6.6 × 150 mm column and a UV-vis detector Agilent Infinity 1260 VL+. The compound was eluted in a mobile phase milliQ water/MeOH at ratio 5/95 in isocratic mode at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C and the detection wavelength was 290 nm. The elution time of -tocopherol was 4.7 min.

The encapsulation efficiency (EE), yield and active loading (AL) were calculated as follows:

where

is the mass of the recovered product,

is the initial mass of the material used,

is the amount of TOCO successfully encapsulated and

is the theoretical amount of TOCO to be encapsulated.

3.3.2. Optical Microscopy Observations

The coacervates microstructure was assessed using an optical microscope (ECLIPSE Ni-U, Nikon) equipped with a camera in phase-contrast mode. The images were captured at a magnification of 200x and analyzed using Nikon software (NIS Element Viewer).

3.3.3. Particle Size Distribution

The particle size distribution of complex coacervates was analyzed using static light scattering with a SALD-7500 Nanoparticle size analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a violet semiconductor laser (405 nm) and a reverse Fourier optical system. Before measurement, samples were diluted in deionized water to achieve an absorption parameter of 0.2. During the measurements, the samples were stirred in the batch cell to ensure homogeneity. For each product, three samples were collected and analyzed, and the measurements were made in triplicate using the Fraunhofer diffraction theory for each sample. Data were analyzed using Wind SALD II software (Version 3.1.0) and the results were presented as average values of D10, D50 and D90 (µm).

For subsequent characterization methods, complex coacervates reticulated with 2% of TA were selected.

3.3.4. Rheological Measurements

The coacervate’s rheological properties were evaluated with a DHR-2 hybrid rheometer (TA Instrument, USA) equipped with a 40 mm aluminum parallel plate device. The temperature was controlled at 20 °C using a Peltier system.

Shear flow experiments were conducted using a continuous flow log ramp with shear rates from 10−3 to 1000 s−1 for five minutes. Results were displayed as shear viscosity and stress as a function of shear rate.

Amplitude strain sweeps from 0.1 to 100% were applied at a constant angular frequency of 1 Hz to determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVER). The oscillating sweep measurements were carried out from 0.1-100 rad.s−1 in the LVER.

3.3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The thermal characteristics of the microparticles were evaluated using a Setsys TGA 1200 device by SETARAM. Samples of 10 mg were placed in an alumina pan and heated from 25 °C to 600 °C at 10 °C/min under ambiant air atmosphere. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

3.3.6. Retention of Active During Storage

The stability of TOCO was evaluated by placing samples in a temperature controlled oven at 40 °C for two months. The concentration of the remaining TOCO was determined according to the procedure described in

Section 3.3.1. TOCO coacervates were compared with nonencapsulated TOCO to assess the retention capacity of the produced microparticles.

3.3.7. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted at least in duplicate. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Collected results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and compared with Tukey’s HSD test, a post-hoc method for determining significant differences between group averages, at a 95% confidence level employing the XLSTAT software (Version 2012.1.01, Addinsoft, Paris, France).

4. Conclusions

In this current study, the lipophilic antioxidant -tocopherol was successfully encapsulated by complex coacervation using diisopropyl adipate as carrier oil, and fungal chitosan and gum Arabic as biopolymers. For the first time in the literature, this work explored tannic acid, a natural polyphenol and antioxidant, as a cross-linking agent for FCGA-TOCO coacervates, examining its impact on morphology, rheological properties, and thermal and storage stability. Reticulated coacervates exhibited an improved encapsulation efficiency, characterized by the development of a denser layer of coacervates surrounding the oil droplets. In addition, the complex coacervates exhibited a liquid-viscoelastic property, which was enhanced by the introduction of tannic acid, resulting in stronger intermolecular interactions. As the molecular network was enhanced, it resulted in a significant improvement in both thermal and storage stability, making them appropriate for high-temperature processes. After two months at 40 °C, 30% more -tocopherol was preserved compared to the non-encapsulated one. Overall, the complex coacervates cross-linked with 2% of TA demonstrated exceptional storage stability at 40 °C. Tannic acid and chitosan, acknowledged for their biocompatibility, non-toxicity, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, make these newly developed coacervates multifunctional and highly promising for potential applications across various industries, including food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals, where multifunctional, durable and stable products are essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.; methodology, A.D.; validation, M.G. and E.G.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, A.D.; resources, A.D. and E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.D., M.G. and E.G.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, M.G. and E.G.; project administration, A.D. and E.G.; funding acquisition, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Graduate School of Research XL-Chem (ANR-18-EURE-0020 XL-Chem), Université Le Havre Normandie and the Région Normandie (RIN Label Caps4Skin).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Graduate School of Research XL-Chem, Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), Université Le Havre Normandie and the Région Normandie for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Casanova, F.; Santos, L. Encapsulation of cosmetic active ingredients for topical application – a review. Journal of Microencapsulation 2016, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, N.V.N.; Prasanna, P.M.; Sakarkar, S.N.; Prabha, K.S.; Ramaiah, P.S.; Srawan, G.Y. Microencapsulation techniques, factors influencing encapsulation efficiency. Journal of Microencapsulation 2010, 27, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Akanbi, T.O.; Khalid, N.; Adhikari, B.; Barrow, C.J. Complex coacervation: Principles, mechanisms and applications in microencapsulation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 121, 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. The progress and application of vitamin E encapsulation – A review. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 121, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Song, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Zheng, X.; Li, X. Microencapsulation of algae oil by complex coacervation of chitosan and modified starch: Characterization and oxidative stability. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 194, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plati, F.; Ritzoulis, C.; Pavlidou, E.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Complex coacervate formation between hemp protein isolate and gum Arabic: Formulation and characterization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 182, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, J.; Conforto, E.; Chaigneau, C.; Vendeville, J.E.; Maugard, T. Microencapsulation and controlled release of α-tocopherol by complex coacervation between pea protein and tragacanth gum: A comparative study with arabic and tara gums. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2022, 77, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, D.; Preece, J.A.; Zhibing, Z. Encapsulation of hexylsalicylate in an animal-free chitosan-gum arabic shell by complex coacervation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 625, 126861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, D.; Preece, J.A.; Zhibing, Z. Microcapsules with a fungal chitosan-gum Arabic-maltodextrin shell to encapsulate health-beneficial peppermint oil. Food Hydrocolloids for Health 2021, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, D.; Zhang, Z. Microplastic-Free Microcapsules to Encapsulate Health-Promoting Limonene Oil. Molecules 2022, 27, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulka, K.; Sionkowska, A. Chitosan Based Materials in Cosmetic Applications: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budinčić, J.M.; Petrović, L.; Dekić, L.; Fraj, J.; Bučko, S.; Katona, J.; Spasojević, L. Study of vitamin E microencapsulation and controlled release from chitosan/sodium lauryl ether sulfate microcapsules. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 251, 116988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, R.; Niu, Y. Production and characterization of multinuclear microcapsules encapsulating lavender oil by complex coacervation. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2014, 29, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, S.; Harlander, K.R.; Reineccius, G.A. Formation and characterization of microcapsules by complex coacervation with liquid or solid aroma cores. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2009, 24, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junyaprasert, V.B.; Mitrevej, A.; Sinchaipanid, N.; Boonme, P.; Wurster, D.E. Effect of process variables on the microencapsulation of vitamin A palmitate by gelatin-acacia coacervation. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2001, 27, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Roy, S.; Ezati, P.; Yang, D.P.; Rhim, J.W. Tannic acid: A green crosslinker for biopolymer-based food packaging films. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2023, 136, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupantsis, T.; Pavlidou, E.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Glycerol and tannic acid as applied in the preparation of milk proteins – CMC complex coavervates for flavour encapsulation. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 57, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Weng, J.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Gong, J. Preparation of pH-stabilized microcapsules for controlled release of DEET via novel CS deposition and complex coacervation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 658, 130651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, H.; Yang, X.; Ma, Q. Tannic acid: a crosslinker leading to versatile functional polymeric networks: a review. RSC Advances 2022, 12, 7689–7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Pan, C.H.; Chung, D. Tannic acid cross-linked gelatin–gum arabic coacervate microspheres for sustained release of allyl isothiocyanate: Characterization and in vitro release study. Food Research International 2011, 44, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, J.D.B.; Barroso, T.L.C.T.; Oliveira, M.D.A.; Mendes, F.R.D.S.; Costa, J.M.C.D.; Moreira, R.D.A.; Furtado, R.F. Cross-linked coacervates of cashew gum and gelatin in the encapsulation of pequi oil. Ciência Rural 2019, 49, e20190079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Q.; Wang, H.O.; Wang, F.W.; Du, Y.L.; Xiao, J.X. Maillard reaction in protein – polysaccharide coacervated microcapsules and its effects on microcapsule properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 155, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkawy, A.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Shoeib, T. Aroma-Loaded Microcapsules with Antibacterial Activity for Eco-Friendly Textile Application: Synthesis, Characterization, Release, and Green Grafting. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2017, 56, 5516–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, S.; Du, G.; Chen, H.; Yan, X.; Chang, S.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y. Formulation and characterization of microcapsules encapsulating carvacrol using complex coacervation crosslinked with tannic acid. LWT 2022, 165, 113683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhoza, B.; Xia, S.; Cai, J.; Zhang, X.; Duhoranimana, E.; Su, J. Gelatin and pectin complex coacervates as carriers for cinnamaldehyde: Effect of pectin esterification degree on coacervate formation, and enhanced thermal stability. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 87, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Kou, M.; Fan, J.; Pan, W.; Feng, Z.J.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, W. Structural characteristics and rheological properties of ovalbumin-gum arabic complex coacervates. Food Chemistry 2018, 260, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussi Hachfi, R.; Famelart, M.H.; Rousseau, F.; Hamon, P.; Bouhallab, S. Rheological characterization of β-lactoglobulin/lactoferrin complex coacervates. LWT 2022, 163, 113577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbreck, F.; Wientjes, R.H.W.; Nieuwenhuijse, H.; Robijn, G.W.; de Kruif, C.G. Rheological properties of whey protein/gum arabic coacervates. Journal of Rheology 2004, 48, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, M.; Chung, D. Dynamic rheological and structural characterization of fish gelatin – Gum arabic coacervate gels cross-linked by tannic acid. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 60, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, J.L.; Marcy, J.E.; O’Keefe, S.F.; Duncan, S.E. Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex Formation and Solid-State Characterization of the Natural Antioxidants α-Tocopherol and Quercetin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donchai, W.; Aldred, A.K.; Junkum, A.; Chansang, A. Controlled release of DEET and Picaridin mosquito repellents from microcapsules prepared by complex coacervation using gum Arabic and chitosan. Pharmaceutical Sciences Asia 2022, 2022, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P.Z.; Li, S.D.; Ou, C.Y.; Li, C.P.; Yang, L.; Zhang, C.H. Thermogravimetric analysis of chitosan. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2007, 105, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Encapsulation of Ginger Essential Oil Using Complex Coacervation Method: Coacervate Formation, Rheological Property, and Physicochemical Characterization. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2020, 13, 1405–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xia, S.; Xiao, C. Complex coacervation microcapsules by tannic acid crosslinking prolong the antifungal activity of cinnamaldehyde against Aspergillus brasiliensis. Food Bioscience 2022, 47, 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaai, M.R. Calculation of Mark–Houwink–Sakurada (MHS) equation viscometric constants for chitosan in any solvent–temperature system using experimental reported viscometric constants data. Carbohydrate Polymers 2007, 68, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Díaz, D.; Navaza, J.M.; Quintáns-Riveiro, L. Intrinsic Viscosity and Flow Behaviour of Arabic Gum Aqueous Solutions. International Journal of Food Properties 2008, 11, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, O.H.M.; Williams, P.A.; Phillips, G.O. Characterisation of gum from Acacia senegal trees of different age and location using multidetection gel permeation chromatography. Food Hydrocolloids 1998, 12, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).