Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Previous Research on Factors Affecting Pedestrian Behaviors at Signalized Intersections

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Study Framework

- pedestrian characteristics – age group and gender;

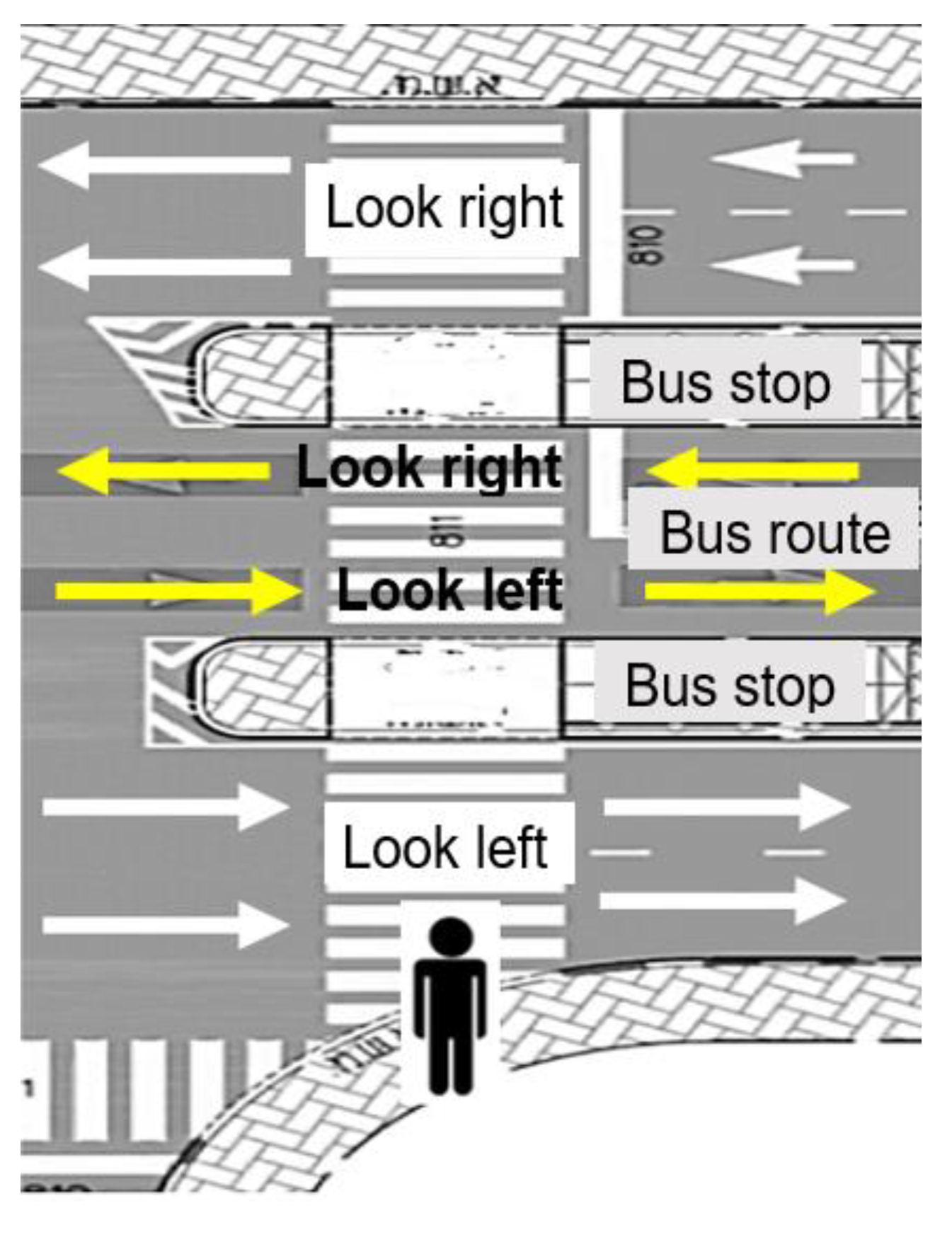

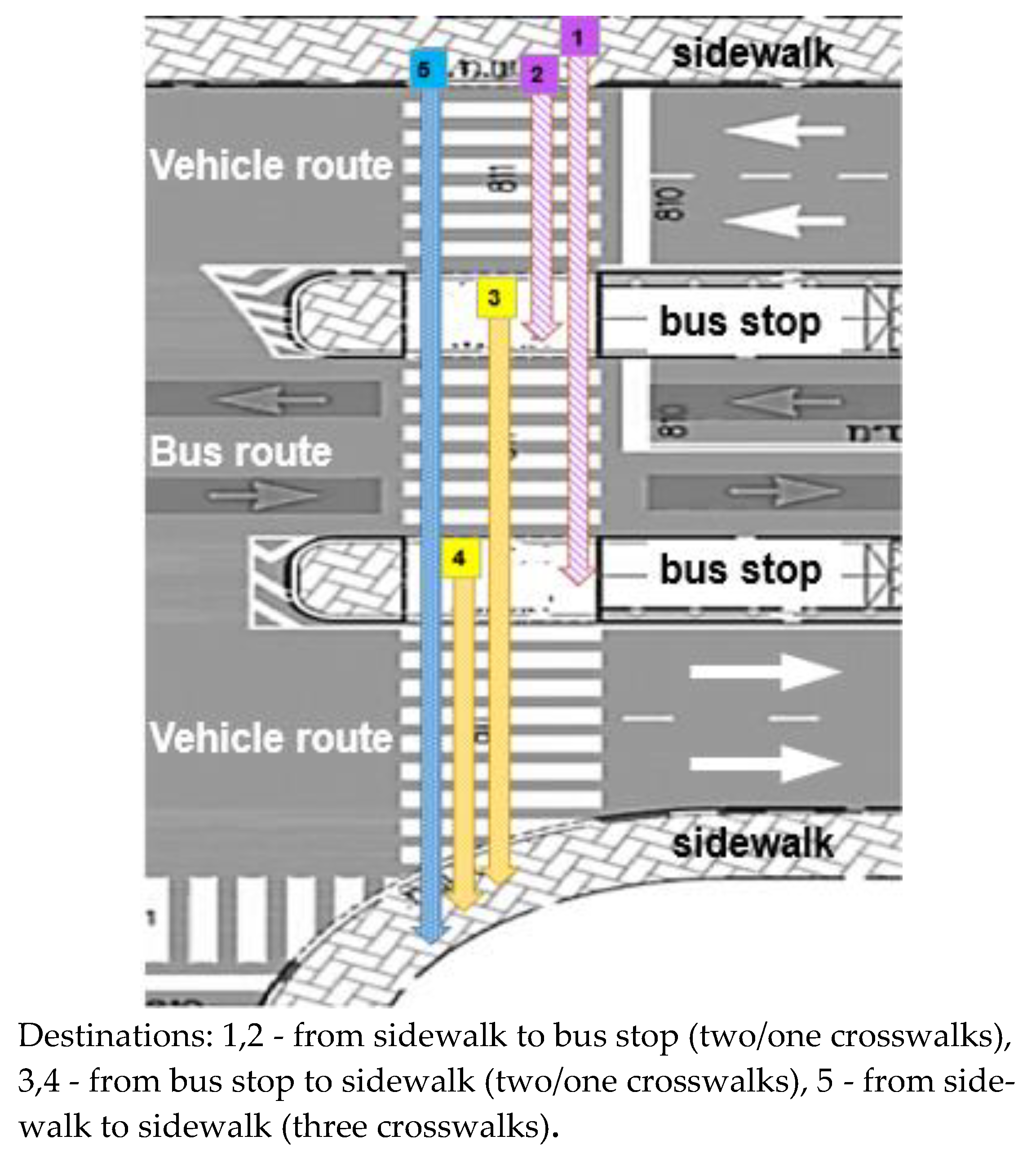

- crossing characteristics – direction of crossing, destination of crossing (to or from the bus stop, or from one side to another side of the intersection), time (hour);

- intersection characteristics – type of BPR (CL or CS), bus stops' location (on one side or both sides of the intersection), traffic levels (number of crossing pedestrians, number of buses in the BPR, per hour), duration of red light;

- situational variables - presence of other pedestrians (yes, no), presence of a bus at the bus stop (yes, no), use of distracting devices by pedestrian – a mobile-phone, earphones (yes, no).

3.2. Data Collection and Analyses

4. Results

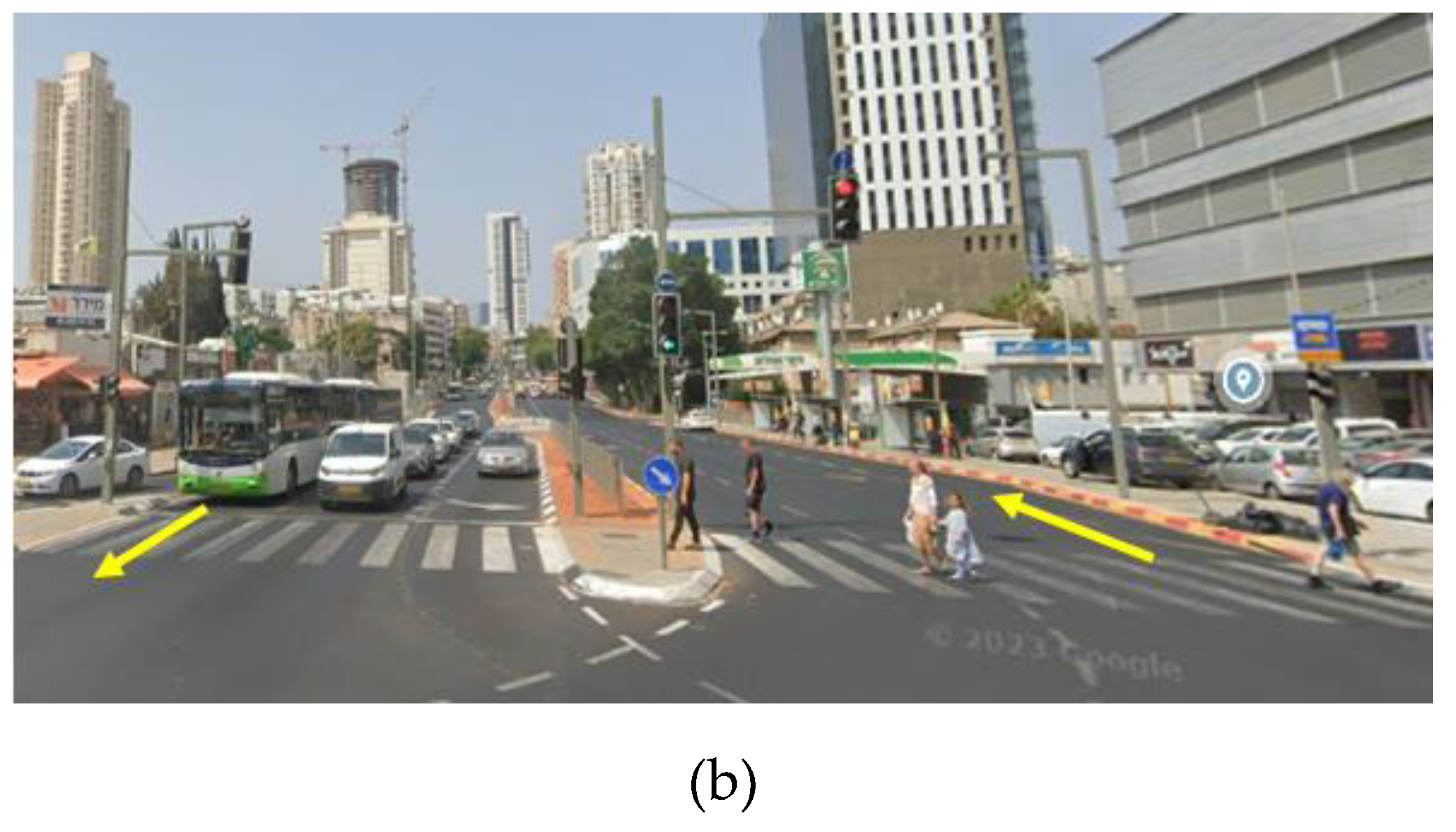

4.1. Pedestrian Behaviors at Intersections with Centre-Lane BPRs

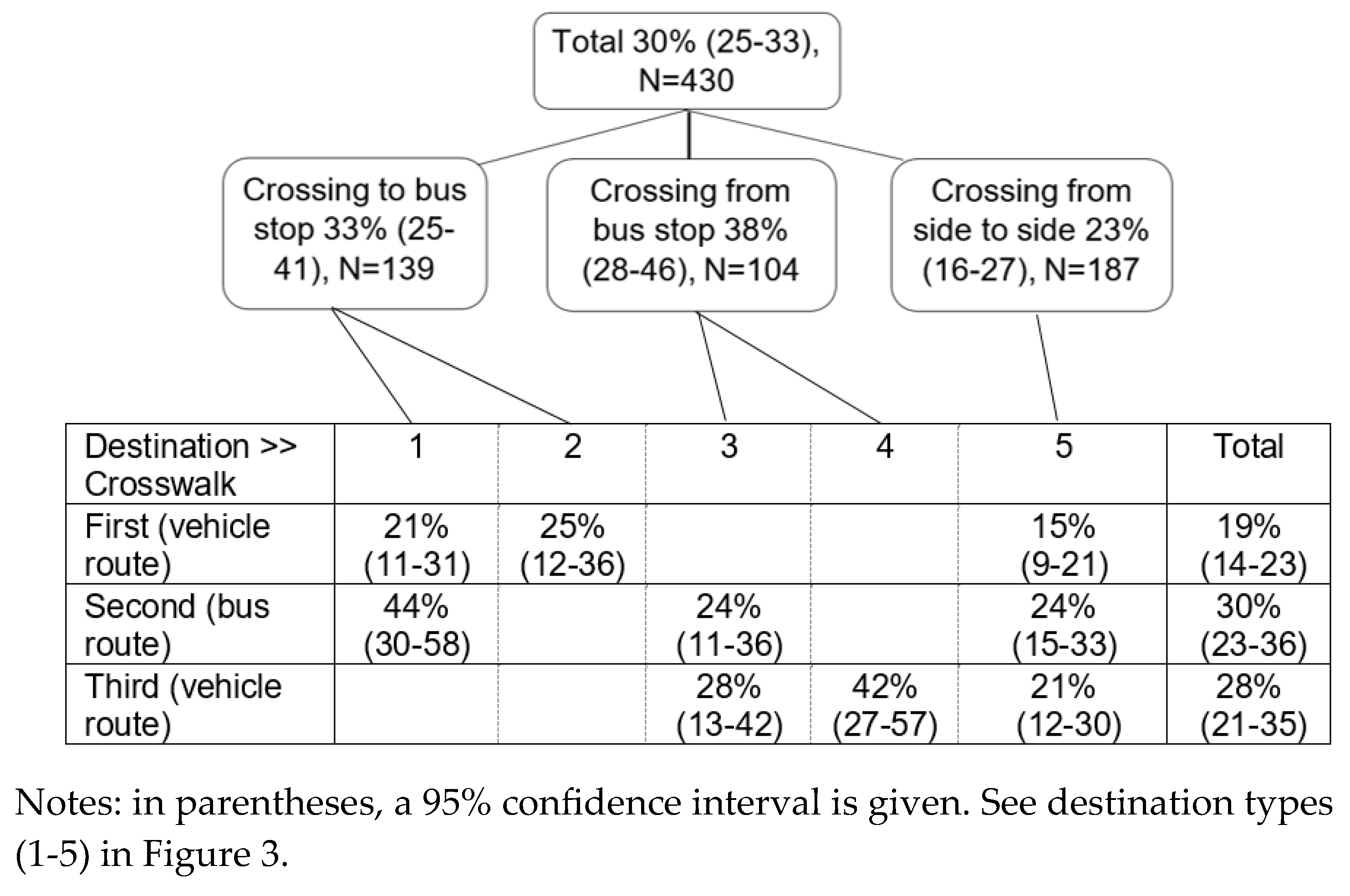

- Overall, 30% of the pedestrians observed crossed on red, at least in one crosswalk, with a higher rate among pedestrians crossing to or from a bus stop compared to those who crossed to another side of the intersection: 33% and 38% vs. 23% (χ2[2]=8.51, p<0.05).

- In the first crosswalk (a vehicle route), 19% of pedestrians crossed on red, and this rate was higher among those who crossed to a bus stop related to crossings to the other side of the intersection (difference not significant).

- In the middle crosswalk (a bus route), 30% of pedestrians crossed on red light, and this behavior was more common among pedestrians who went to the bus stop compared to other crossing situations: 44% vs. 24% (χ2[2]=7.17, p<0.05).

- In the third crosswalk (a vehicle route), 28% of pedestrians crossed on red, while this behavior was more frequent among pedestrians who crossed only one crosswalk on their way from the bus stop compared to those who crossed two crosswalks on their way from the bus stop or crossed to the other side of the intersection: 42%, 28% and 21%, respectively (χ2[2]=6.25, p<0.05).

- Overall, about 35% of pedestrians crossed at CL BPR intersections while distracted - using earphones and/or a mobile phone. As expected, the frequency of usage was very low among elderly pedestrians compared to other age groups: 3% vs. about a third (χ2[2]=31.90, p<0.001).

- This behavior was more common among pedestrians who crossed to the other side of the intersection compared to those crossing to or from a bus stop: 43% vs. 16% (χ2[1]=6.55, p<0.05).

4.2. Pedestrian Behaviors at Intersections with Curbside BPRs

- Overall, 11% of pedestrians crossed on red in at least one crosswalk of the intersection (95% confidence interval, CI: 3%-8%); on average, 6% crossed on red in the first crosswalk (CI: 8%-15%) and 12% on the second crosswalk (CI: 8%-13%).

- Similar to the behaviors observed at the CL BPR sites, the rate of crossing on red was higher when the pedestrian was alone related to the cases when other pedestrians were waiting on the sidewalk: 19% vs. 3% (χ2[1]=21.77, p<0.001). The rate of pedestrians crossing on red in the first crosswalk was not affected by the duration of the red light (t(352)=-0.85, not significant), bus presence at the bus stop or bus stop location.

- The rate of red-light crossings in at least one crosswalk of the intersection was higher in hours 8am and 10am related to other hours of observations (χ2[5]=11.22, p<0.05).

- Overall, about a quarter of pedestrians crossed the CS BPR sites while using distracting devices. Similar to findings at the CL sites, the frequency of using distracting devices was lower among elderly pedestrians compared to other age groups: 3% vs. 25% (χ2[2]=13.67, p<0.01).

4.3. A Combined Model for Both Types of Sites

4.4. Other Pedestrian Behaviors When Crossing on Red at Intersections with BPRs

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2007. Managing urban traffic congestion. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, European Conference of Ministers of Transport.

- UITP, 2017. Statistics brief, urban public transport in the 21st century. The International Association of Public Transport (UITP).

- Paganelli, F., 2020. Urban Mobility and Transportation. In: Filho, W.L., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L. et al., Sustainable cities and communities. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer International Publishing, 887-899.

- Rupprecht Consult, 2019. Guidelines for developing and implementing a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, 2nd ed.; Forschung, B.G., ed.; Cologne, Germany: Rupprecht Consult.

- Smart Growth America, 2023. Accessed on November 10, 2023. https://smartgrowthamerica.org/what-is-smart-growth/.

- Ministry of Transport (MOT), 2012. Strategic program for public transport development. Ministry of Transport, Israel.

- Planning Administration, 2020. Basic principles for public transportation' and sustainable traffic' biased planning - criteria for submitting plans to planning institutions. Planning Administration, Jerusalem, Israel. https://www.gov.il/he/departments/general/planning_public_transp_sustainable_mov.

- Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP), 2007. Bus rapid transit practitioner's guide. TCRP report 118, Transit Cooperative Research Program, Washington, D.C.

- Institute for Transportation & Development Policy (ITDP), 2007. Bus rapid transit planning guide. Institute for Transportation & Development Policy, New York, USA.

- Panera, M., Shin, H., Zerkin, A., Zimmerman, S., 2012. Peer-to-peer information exchange on bus rapid transit and bus priority practices. FTA report 009, Federal Transit Administration, US Department of Transportation.

- Levinson, H., Zimmerman, S., Clinger, J., Rutherford, S., Smith, R. L., Cracknell, J., Soberman, R., 2003. Bus Rapid Transit: case studies in Bus Rapid Transit. TCRP Report 90, Volume I. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, D.C.

- Duduta, N., Adriazola-Steli, K., Wass, C., Hidlago, D., Lindau L.-A., John, V.-S., 2014. Traffic safety on bus priority systems. Recommendations for integrating safety into the planning, design and operation of major bus routes. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), 2023. Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety in Bus Rapid Transit and High-Priority Bus Corridors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, V., Carmel, R., Korchatov, A., 2018. Assessing safety implications of bus priority systems: a case-study of a new BRT system in the Haifa metropolitan area. In: Advances in transport policy and planning. Preparing for the new era of transport policies: learning from experience, Vol. 1, 63-91.

- Duduta, N., Adriazola, C., Hidalgo, D., Lindau, L. A., Jaffe, R., 2015. Traffic safety in surface public transport systems: a synthesis of research. Public Transport 7(2), 121-137. [CrossRef]

- Ingvardson, J. B., & Nielsen, O. A., 2018. Effects of new bus and rail rapid transit systems – an international review. Transport Reviews 38(1), 96-116. [CrossRef]

- Litman, T., 2022. A new traffic safety paradigm. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. https://www.vtpi.org/ntsp.pdf.

- European Commission (EC), 2016. Traffic safety facts on heavy goods vehicles and buses. European Commission, Directorate General for Transport.

- Temurhan, M., Stipdonk, H., 2019. Coaches and road safety in Europe. An indication based on available data 2007-2016. Report R-2019-11. SWOV Institute of Road Safety Research, the Netherlands.

- National Road Safety Authority (NRSA), 2016. The relationship between public transport use and road safety: the situation in Israel and solutions for improving the safety of vulnerable road users. National Road Safety Authority, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Stimpson, J.P., Wilson, F.A., Araz, O.M. and Pagan J.A., 2014. Share of mass transit miles traveled and reduced motor vehicle fatalities in major cities of the United States. Journal of Urban Health 91(6), 1136-1143. [CrossRef]

- Duduta, N., Adrizola, C., Hidalgo, D., Lindau, L. A., Jaffe, R., 2012. Understanding road safety impact of high-performance Bus Rapid Transit and busway design features. Transportation Research Record 2317, 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, V., Carmel, R., Doveh, E., Hakkert, S., 2017. Exploring safety impacts of pedestrian crossing configurations at signalized junctions on urban roads with public transport routes. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion 25(1), 31-40. [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.C.K., Currie, G., Sarvi, M., Logan, D., 2013. Investigating the road safety impacts of bus rapid transit priority measures. Transportation Research Record 2352, 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.C.K., Currie, G., Sarvi, M., Logan, D., 2014. Bus accident analysis of routes with/without bus priority. Accident Analysis & Prevention 65, 18-27. [CrossRef]

- Elvik, R., Hoya, A., Vaa, T., Sorensen, M., 2009. The handbook of road safety measures, 2nd ed. Emerald.

- Bia, E. M., and Ferenchak, N. N., 2022. Impact of Bus Rapid Transit construction and infrastructure on traffic safety: a case study from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Transportation Research Record 2676 (9), 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, V., Korchatov, A., Elias, W., 2020. An examination of the safety impacts of bus priority routes in major Israeli cities. Sustainability 2020(12), 8617;. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Chen, C., Ewing, R., McKnight, C.E., Srinivasan, R., Roe, M., 2013. Safety countermeasures and crash reduction in New York City – Experience and lessons learned. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 50, 312-322. [CrossRef]

- Tse, L. Y, Hung, W. T., Sumalee, A., 2014. Bus lane safety implications: a case study in Hong Kong. Transportmetrica A: Transport Science, 10(2), 140–159. [CrossRef]

- Bocarejo, J. P., Velasquez, J. M., Diaz, C. A., Tafur, L. E., 2012. Impact of BRT systems on road safety: lessons from Bogota. Transportation Research Record 2317, 1-7.

- Ministry of Transport (MOT), 2013. Safety of bus routes. Recommendations of a commission assigned by the general manager of the Ministry of Transport, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Yefe Nof, 2013. Safety audits of bus priority routes in the BRT system of the Haifa metropolitan area: findings from field surveys, pre-opening stage. Summary report submitted to the Yefe Nof Co., Haifa, Israel.

- Martin, A., 2006. Factors influencing pedestrian safety: a literature review. TRL limited.

- Smiley, A., 2015. Human factors in traffic safety. Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company, Inc., Tucson, Arizona.

- Mead, J., Zegeer, C., and Bushell, M., 2014. Evaluation of pedestrian-related roadway measures: a summary of available research. Report DTFH61-11-H-00024. Federal Highway Administration, Washington, DC.

- Koh, P.P., Wong, Y.D., Chandrasekar, P., 2014. Safety evaluation of pedestrian behaviour and violations at signalized pedestrian crossings. Safety Science 70, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Dommes, A., Granié, M. A., Cloutier, M. S., Coquelet, C., & Huguenin-Richard, F., 2015. Red light violations by adult pedestrians and other safety-related behaviors at signalized crosswalks. Accident Analysis & Prevention 80, 67-75. . [CrossRef]

- Dewar R., & Olson P., 2007. Human Factors in Traffic Safety, second ed. Lawyers and Judges Publishing Co., Tucson, Arizona.

- Liu, Y. C., & Tung, Y. C., 2014. Risk analysis of pedestrians’ road-crossing decisions: Effects of age, time gap, time of day, and vehicle speed. Safety Science 63, 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Shinar, D., 2017. Traffic safety and human behavior. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Schwebel, D. C., Davis, A. L., and O’Neal, E. E., 2012. Child pedestrian injury: A review of behavioral risks and preventive strategies. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 6(4), 292-302. [CrossRef]

- Meir, A., Oron-Gilad, T., and Parmet, Y., 2015. Are child-pedestrians able to identify hazardous traffic situations? Measuring their abilities in a virtual reality environment. Safety Science 80, 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, V., Levi, S., Carmel, R., Korchatov, A., Hakkert, S., 2019. Exploring patterns of child pedestrian behaviors at urban intersections. Accident Analysis and Prevention 122, 36-47. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H., Gao, Z., Yang, X., & Jiang, X., 2011. Modeling pedestrian violation behavior at signalized crosswalks in China: A hazards-based duration approach. Traffic Injury Prevention, 12(1), 96-103. . [CrossRef]

- Ren, G., Zhou, Z., Wang, W., Zhang, Y., & Wang, W., 2011. Crossing behaviors of pedestrians at signalized intersections: observational study and survey in China. Transportation Research Record 2264, 65-73. . [CrossRef]

- Levi, S., Gitelman, V., Prihed, I., and Laor, Y., 2015. Study of travel patterns and safety of child pedestrians in municipalities. Beterem - Safe Kids Israel.

- Hamed, M. M., 2001. Analysis of pedestrians’ behavior at pedestrian crossings. Safety Science 38(1), 63-82. . [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, T., 2009. Crossing at a red light: Behaviour of individuals and groups. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 12, 389-394. . [CrossRef]

- Sharon, A., 2019. Pedestrian behaviors at crosswalks: national observational survey 2018. National Road Safety Authority, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Nasar, J., Hecht, P., & Wener, R., 2008. Mobile telephones, distracted attention, and pedestrian safety. Accident Analysis and Prevention 40, 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. I. B., & Huang, Y. P., 2017. The impact of walking while using a smartphone on pedestrians’ awareness of roadside events. Accident Analysis & Prevention 101, 87-96. . [CrossRef]

- Luukkanen, L., 2003. Safety management system and transport safety performance indicators in Finland. Liikenneturva - Central Organization for Traffic Safety in Finland.

- Liikenneturva, 2021. Liikennekäyttäytymisen seuranta.

- Van Houten, R., Ellis, R., & Kim, J. L., 2007. Effects of various minimum green times on percentage of pedestrians waiting for midblock “walk” signal. Transportation Research Record 2002, 78-83. . [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, M., Zangenehpour, S., Saunier, N., & Miranda-Moreno, L., 2013. The impact of waiting time and other factors on dangerous pedestrian crossings and violations at signalized intersections: A case study in Montreal. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 21, 159-172. . [CrossRef]

- De Lavalette, B. C., Tijus, C., Poitrenaud, S., Leproux, C., Bergeron, J., & Thouez, J. P., 2009. Pedestrian crossing decision-making: A situational and behavioral approach. Safety Science 47, 1248-1253. . [CrossRef]

- Kruszyna, M., & Rychlewski, J., 2013. Influence of approaching tram on behaviour of pedestrians in signalised crosswalks in Poland. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 55, 185-191.. [CrossRef]

- Pelé, M., Deneubourg, J. L., & Sueur, C., 2019. Decision-making processes underlying pedestrian behaviors at signalized crossing: Part 1. The first to step off the kerb. Safety 5(4), 79. . [CrossRef]

- Van Houten, R., Retting, R., Farmer, C., & Van Houten, J., 2000. Field evaluation of a leading pedestrian interval signal phase at three urban intersections. Transportation Research Record 1734 (1), 86-92.

- Gitelman V., Carmel R. and Pesahov F., 2020. Evaluating impacts of a leading pedestrian signal on pedestrian crossing conditions at signalized urban intersections: a field study. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2:45. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport (MOT), 1998. Guidelines for designing public transport lanes. Transport planning department, Ministry of Transport, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Ministry of Transport (MOT), 2018. Guidelines for designing Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) lanes. Transport planning department, Ministry of Transport, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Jekel, J. F., Katz, D. L., Elmore, J. G., and Wild, D., 2007. Epidemiology, biostatistics and preventive medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., & Paik, M. C., 2013. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, third ed. John Wiley & Sons.

- Smith, T. J., & McKenna, C. M., 2013. A comparison of logistic regression pseudo R2 indices. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints 39(2), 17-26..

| Characteristic | At sites with CL BPRs (N=592*) | At sites with CS BPRs (N=530*) |

| No of observations per site | 86-137 | 87-131 |

| Pedestrian age-groups | Below 18 (8%), 18-64 (86%), 65+ (6%) | Below 18 (6%), 18-64 (83%), 65+ (11%) |

| Pedestrian gender | Males (42%), females (58%) | Males (41%), females (59%) |

| Hourly number of crossing pedestrians: mean (s.d.) | 239 (106) | 179 (66) |

| Hourly bus volume in BPR: mean (s.d.) | 29 (17) | 50 (21) |

| Red light duration for pedestrians, sec: mean (s.d.) | In first crosswalk - 82.6 (20.1), in second crosswalk - 63.5 (27.1) | In first crosswalk - 42.3 (6.8), in second crosswalk -30.6 (10.7) |

| Pedestrian crossing destination | To bus stop (37%), from bus stop (28%), to another sidewalk (35%) | To another sidewalk (100%) |

| No of pedestrians approaching the crosswalk on red (% of crossings on red) | In first crosswalk - 353 (19%), in BPR crosswalk -188 (30%), in third crosswalk - 84 (28%) | In first crosswalk - 354 (6%), in second crosswalk - 290 (12%) |

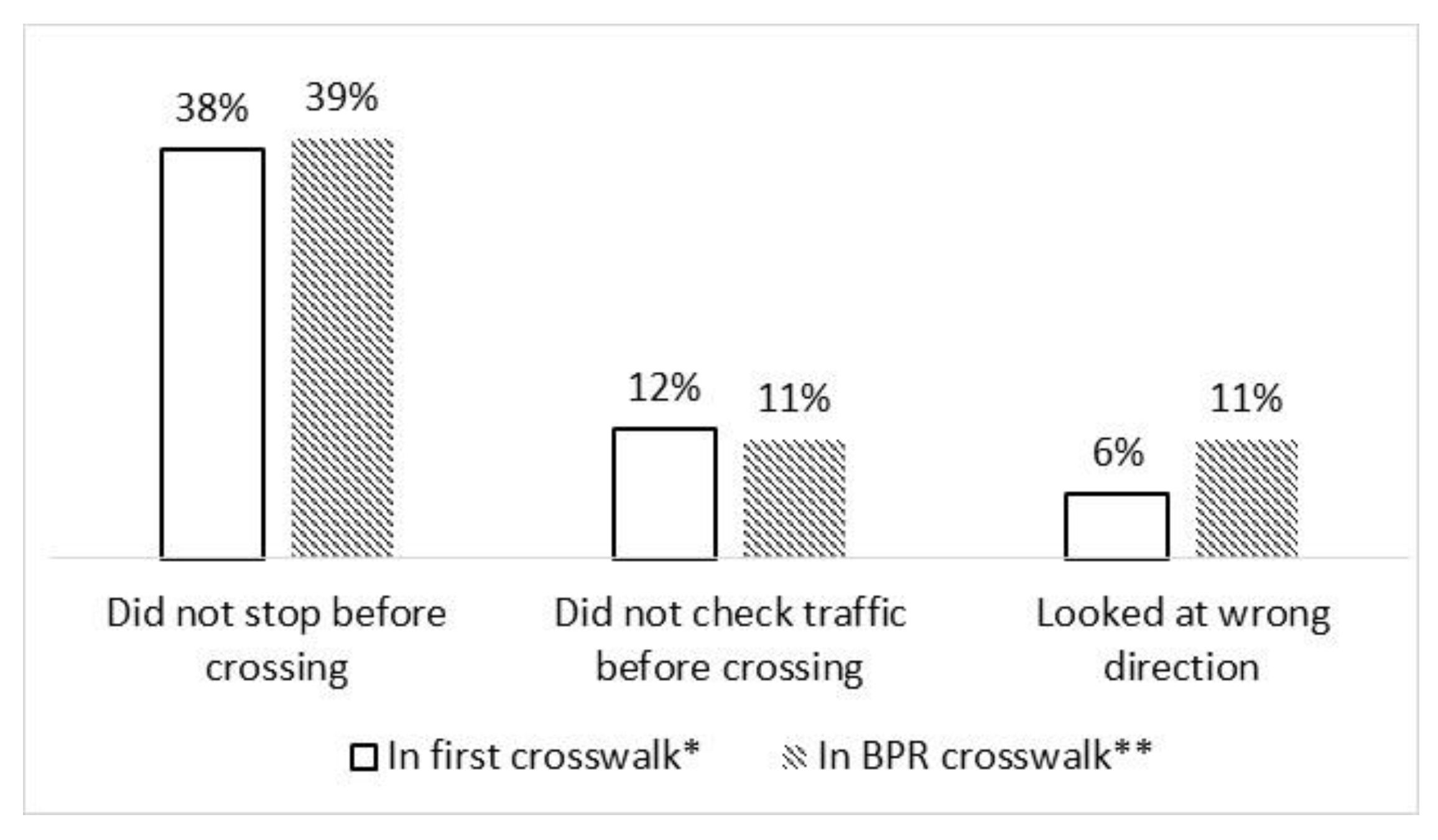

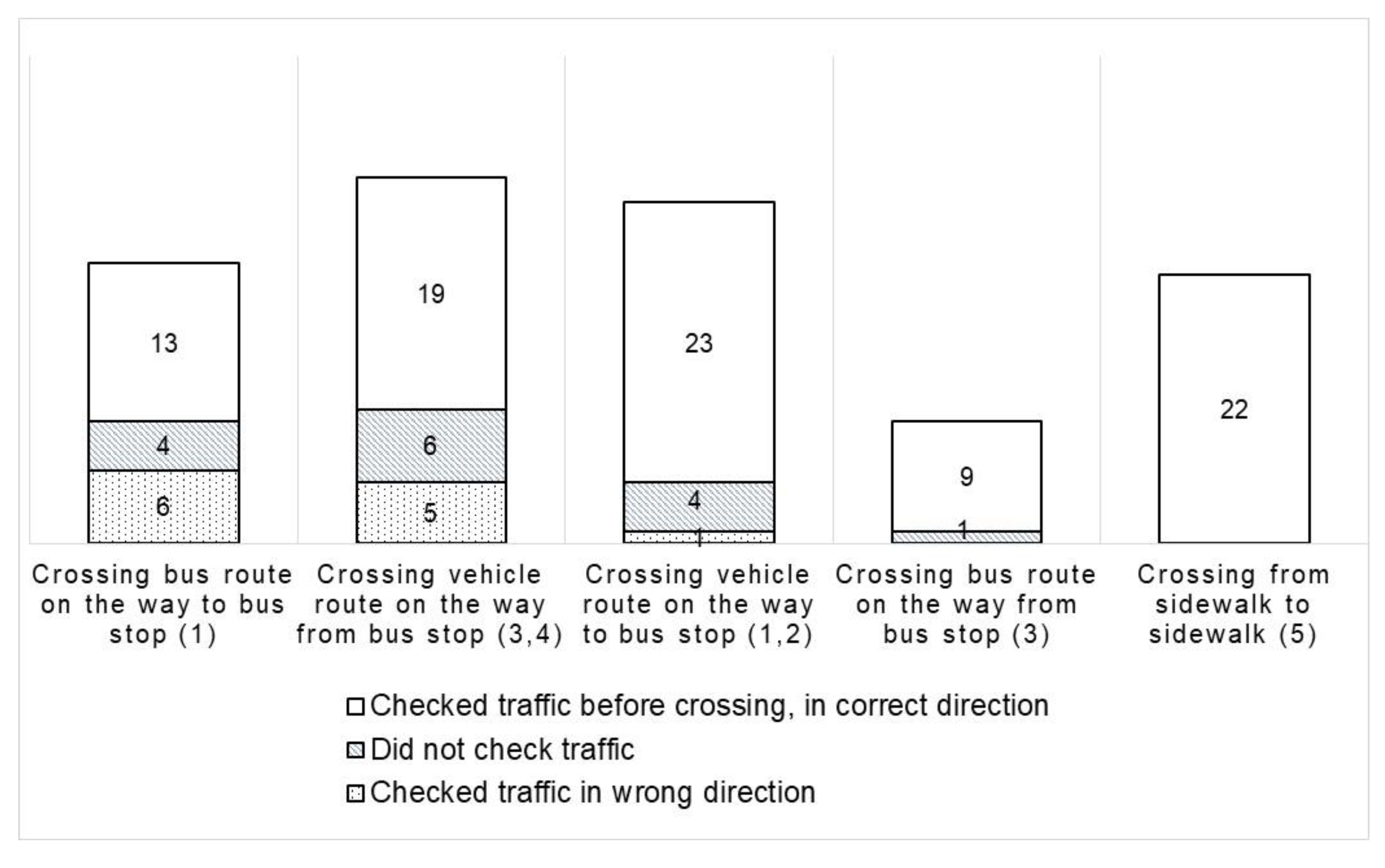

| Among pedestrians who crossed on red: % of not checking traffic, % of checking traffic in wrong direction | In first crosswalk: 12%, 6%; in BPR crosswalk: 11%, 11%; in third crosswalk: 6%, 0% | In first crosswalk: 30%, 5%; in second crosswalk: 26%, 6% |

| Use of distracting devices by crossing pedestrians | Wearing headphones (9%), talking on the phone (16%), looking at the phone (15%) | Wearing headphones (12%), talking on the phone (9%), looking at the phone (10%) |

| a - In the first crosswalk | ||||||||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Males vs. females | .272 | .272 | .997 | .318 | 1.313 | .770 | 2.238 | |

| Using distracting devices vs. not | -.244 | .316 | .594 | .441 | .784 | .422 | 1.457 | |

| Crossing to bus stop vs. from side to side | .381 | .348 | 1.202 | .273 | 1.464 | .741 | 2.894 | |

| Crossing from bus stop vs. from side to side | .915 | .359 | 6.502 | .011 | 2.497* | 1.236 | 5.047 | |

| Direction of crossing | -.236 | .280 | .710 | .400 | .790 | .456 | 1.368 | |

| Presence of other pedestrians vs. alone | -.733 | .293 | 6.272 | .012 | .480* | .271 | .853 | |

| Bus present at bus stop vs. not | -.268 | .274 | .959 | .327 | .765 | .447 | 1.308 | |

| Bus stops' location: on one side vs. both sides | .543 | .326 | 2.780 | .095 | 1.721# | .909 | 3.258 | |

| Hour of observation | .194 | .091 | 4.555 | .033 | 1.214* | 1.016 | 1.451 | |

| Constant | -3.292 | 1.033 | 10.151 | .001 | .037 | |||

| b - In the BPR crosswalk | ||||||||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Males vs. females | 1.059 | .347 | 9.304 | .002 | 2.883** | 1.460 | 5.693 | |

| Using distracting devices vs. not | -.750 | .397 | 3.560 | .059 | .472# | .217 | 1.029 | |

| Crossing to bus stop vs. from side to side | .957 | .411 | 5.429 | .020 | 2.603* | 1.164 | 5.819 | |

| Crossing from bus stop vs. from side to side | .096 | .462 | .043 | .836 | 1.100 | .445 | 2.723 | |

| Direction of crossing | .045 | .390 | .013 | .908 | 1.046 | .487 | 2.248 | |

| Presence of other pedestrians vs. alone | -.130 | .411 | .100 | .752 | .878 | .392 | 1.965 | |

| Bus present at bus stop vs. not | .333 | .374 | .791 | .374 | 1.395 | .670 | 2.903 | |

| Bus stops' location: on one side vs. both sides | .174 | .410 | .181 | .670 | 1.191 | .533 | 2.658 | |

| Hour of observation | .128 | .121 | 1.122 | .289 | 1.137 | .897 | 1.442 | |

| Constant | -3.019 | 1.398 | 4.663 | .031 | .049 | |||

| c - In at least one crosswalk | ||||||||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Males vs. females | .664 | .222 | 8.941 | .003 | 1.943** | 1.257 | 3.003 | |

| Using distracting devices vs. not | -.211 | .247 | .726 | .394 | .810 | .499 | 1.315 | |

| Crossing to bus stop vs. from side to side | .522 | .269 | 3.759 | .053 | 1.686# | .994 | 2.858 | |

| Crossing from bus stop vs. from side to side | .764 | .290 | 6.927 | .008 | 2.146** | 1.215 | 3.789 | |

| Direction of crossing | -.238 | .229 | 1.072 | .301 | .789 | .503 | 1.236 | |

| Presence of other pedestrians vs. alone | -.515 | .248 | 4.333 | .037 | .597* | .368 | .970 | |

| Bus present at bus stop vs. not | -.279 | .225 | 1.539 | .215 | .756 | .487 | 1.176 | |

| Bus stops' location: on one side vs. both sides | .213 | .254 | .701 | .402 | 1.237 | .752 | 2.034 | |

| Hour of observation | .080 | .073 | 1.199 | .273 | 1.083 | .939 | 1.249 | |

| Constant | -1.770 | .824 | 4.613 | .032 | .170 | |||

| a - In the first crosswalk | ||||||||||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Males vs. females | .617 | .500 | 1.523 | .217 | 1.853 | .696 | 4.936 | |||

| Young vs. elderly | -.135 | .968 | .019 | .889 | .874 | .131 | 5.824 | |||

| Adults vs. elderly | -.972 | .660 | 2.172 | .141 | .378 | .104 | 1.378 | |||

| Using distracting devices vs. not | .447 | .574 | .606 | .436 | 1.563 | .508 | 4.815 | |||

| Direction of crossing | -.088 | .530 | .028 | .868 | .916 | .324 | 2.589 | |||

| Presence of other pedestrians vs. alone | -1.820 | .501 | 13.196 | <.001 | .162** | .061 | .433 | |||

| Hour of observation | -.121 | .192 | .396 | .529 | .886 | .609 | 1.291 | |||

| Constant | .042 | 2.229 | .000 | .985 | 1.043 | |||||

| b - In at least one crosswalk | ||||||||||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Males vs. females | .677 | .303 | 4.979 | .026 | 1.968* | 1.086 | 3.568 | |||

| Young vs. elderly | .535 | .671 | .636 | .425 | 1.707 | .458 | 6.359 | |||

| Adults vs. elderly | .097 | .475 | .042 | .837 | 1.102 | .435 | 2.796 | |||

| Using distracting devices vs. not | -.668 | .411 | 2.635 | .105 | .513 | .229 | 1.148 | |||

| Direction of crossing | .212 | .353 | .361 | .548 | 1.236 | .619 | 2.470 | |||

| Presence of other pedestrians vs. alone | -.741 | .337 | 4.825 | .028 | .477* | .246 | .923 | |||

| Hour of observation | -.137 | .114 | 1.430 | .232 | .872 | .697 | 1.091 | |||

| Constant | -.626 | 1.346 | .216 | .642 | .535 | |||||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Males vs. females | 0.352 | 0.232 | 2.311 | 0.129 | 1.422 | 0.903 | 2.240 |

| Young vs. elderly | 1.317 | 0.639 | 4.242 | 0.039 | 3.732* | 1.066 | 13.070 |

| Adults vs. elderly | 0.831 | 0.500 | 2.761 | 0.097 | 2.295# | 0.862 | 6.115 |

| Using distracting devices vs. not | -0.186 | 0.274 | 0.462 | 0.496 | 0.830 | 0.486 | 1.419 |

| Direction of crossing | -0.095 | 0.232 | 0.169 | 0.681 | 0.909 | 0.577 | 1.432 |

| Presence of other pedestrians vs. alone | -0.940 | 0.246 | 14.603 | 0.000 | 0.391** | 0.241 | 0.633 |

| Hour of observation | 0.193 | 0.087 | 4.967 | 0.026 | 1.213* | 1.024 | 1.438 |

| Duration of red light | -0.009 | 0.007 | 1.517 | 0.218 | 0.991 | 0.978 | 1.005 |

| Type of BPR: CL vs. CS | 1.721 | 0.379 | 20.666 | 0.000 | 5.589** | 2.662 | 11.737 |

| Constant | -4.500 | 1.051 | 18.343 | 0.000 | 0.011 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).