1. Introduction

Because of their versatility and adaptability, goats play a key role in livestock production. They can survive in a wide range of climatic conditions, from hot deserts to cool mountainous areas, and are able to consume a wide range of plants [

1]. Their adaptability makes them a valuable source of income and food in regions where other livestock would struggle to survive. In addition, goats provide milk, meat and skin, which are important sources of food and income for many small-scale farmers, particularly in developing countries. Unfortunately, goats have been less studied than other livestock, and their nutritional and health needs remain relatively poorly understood [

2].

While goats have a lower environmental impact than cattle, due to their lower water and feed requirements, goat farming offers a more sustainable and environmentally-friendly alternative that is more attractive in the context of growing global environmental concerns. Despite these advantages, further research into goat nutrition is needed to optimize goat diets and ensure optimal rearing conditions, especially in the face of changing climatic conditions and production requirements [

3].

Nutrition plays an important role in ensuring the health and productivity of goats on the farm [

4]. Diet composition has a significant impact not only on animal health, but also on the quality of their products, such as milk and meat. An appropriate diet containing essential nutrients can significantly improve their growth, development and reproductive health, resulting in better breeding performance, fewer health problems and greater productivity [

5]. A key goal for ensuring goat health, productivity and sustainable agriculture, is devising effective forage enrichment. Such research not only responds to current agricultural challenges, but also contributes to the development of more sustainable farming practices worldwide. The drive to develop effective feed supplements, for example based on natural plant extracts, is critical to improving overall animal health and production efficiency. Despite advances in research into these extracts and their potential benefits for goats, further research is still needed to fully understand the mechanisms of action of the feed ingredients and their optimal doses to maximize their beneficial effects on animal health and productivity [

6].

One area of particular interest is the supplementation of goats with different blends of plant extracts, as this may strengthen the immune system, reduce inflammation and protect against oxidative stress; thus supplementation can result in better production performance, increased milk production and weight gain [

7]. In addition, natural supplements may help reduce the need for antibiotics, which is a key consideration in the face of increasing bacterial resistance. Furthermore, this research can contribute to the development of more sustainable and environmentally-friendly farming practices, benefiting farmers, consumers and the environment alike[

8].

When choosing a plant as a dietary supplement, the species of the

Lamiaceae family have aroused considerable interest due to the presence of rosmarinic acid [

9]. Rosmarinic acid has a wide range of beneficial properties, including anti-inflammatory [

10], antimutagenic[

11], and antitumour and antiproliferative activities[

12]. It has also demonstrated various anti-cyclooxygenase effects [

13], anti-allergic properties [

14] and antidepressant activity [

15]. Rosmarinic acid has also been found to have antiviral activity and act as a potent natural antioxidant [

16], potentially protecting against conditions induced by free radicals.

Both clinical studies and veterinary medicine have found turmeric (

Curcuma longa) to have various pro-health effects which have been attributed to its numerous constituents, particularly major curcuminoids [

17]. The health benefits of turmeric are believed to revolve around curcumin, a lipophilic polyphenolic compound with an orange-yellow hue that is derived from the rhizomes. Indeed, recent research have found curcumin to have various antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties [

18], which may support its role in the prevention and treatment of

inter alia cancer, autoimmune disorders, neurological conditions, and cardiovascular disease [

19].

Various studies indicate the supplementation with turmeric (

Curcuma longa) and rosemary (

Rosmarinus officinalis) extracts have multiple beneficial effects on the health, performance and quality of goat products, which may have important implications for breeding practices and food production [

20,

21]. Furthermore, curcumin and rosemary supplementation has been found to alter the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism, which may account for the observed phenotypic changes.

A study of the effect of curcumin and rosemary supplementation in young castrated bucks [

22] showed that supplementation may modulate the immune response by influencing the expression of the genes controlling certain cytokines, including

IL-1β,

IL-6 and

TNF-α, in the liver. Similarly, in another study of young castrated Polish White Improved (PWI) bucks, [

23] found the

Curcuma longa and

Rosmarinus officinalis extracts altered the genetic expression of acute phase proteins, cathelicidin, defensin and cytolytic proteins in the liver, particularly those related to the inflammatory response and defense mechanisms; this may suggest that adding turmeric and rosemary to animal diets offers potential health benefits. Previous studies on supplementation with different blends of plant extracts, such as turmeric and rosemary, had beneficial effects on weight gain and improved meat quality, especially in terms of fat content, in young castrated PWI bucks [

24].

As relatively few studies have examined the effect of supplementation on antioxidant balance in livestock, this has been chosen as the focus of our investigation. The findings should provide a clearer picture of how the use of the applied supplements affects the antioxidant status of goat blood. Not only will the results be valuable for scientific research, but they may have considerable practical applications in Medicine and Veterinary Science.

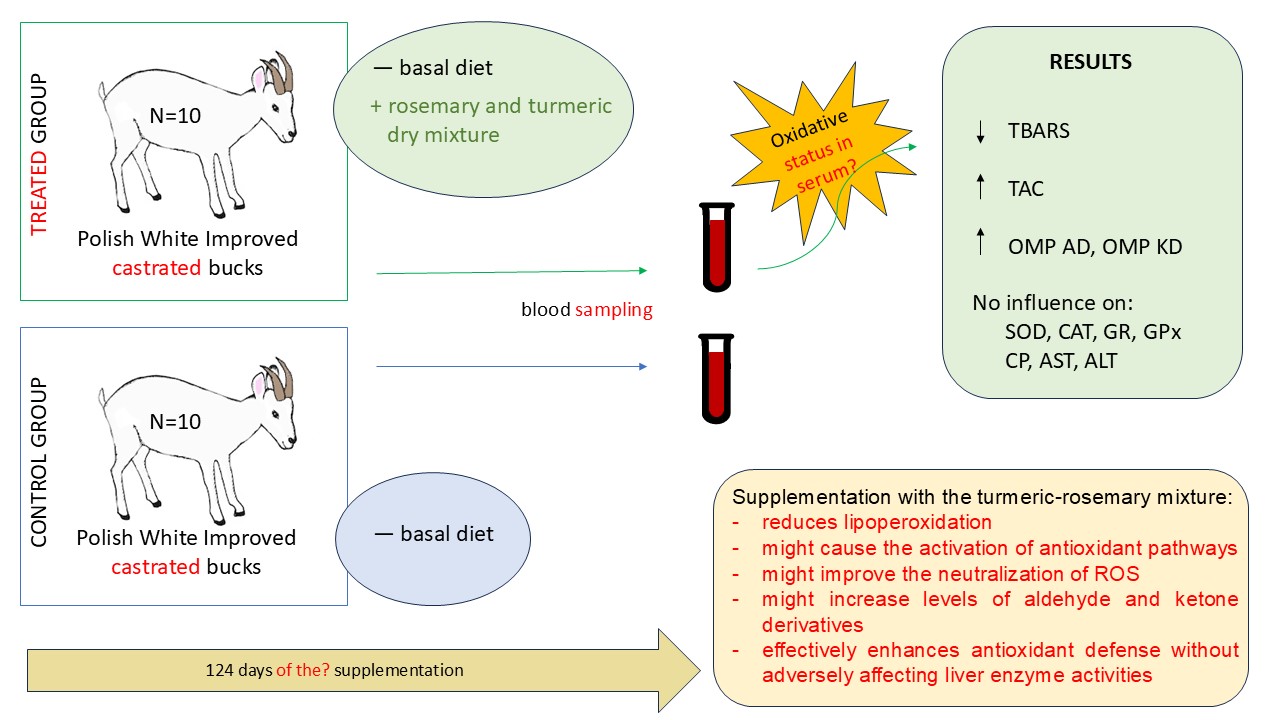

The aim of the study is the determine the effect of the turmeric-rosemary extract on various aspects of the antioxidant status of the blood of young PWI bucks: 1) the levels of lipid peroxidation and oxidative modification of proteins (OMPs) in the serum; 2) blood total antioxidant capacity (TAC); 3) antioxidant enzyme activity, viz. superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione reductase (GR); 4) measurement of selected biochemical parameters including alanine- (ALT) and aspartate (AST) aminotransferase activities and ceruloplasmin (CP) levels. These enzymes and parameters are essential for understanding the body’s defense mechanisms in response to oxidative stress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Groups

The experiments were carried out on 20 young PWI castrated bucks. The mean weight of the bucks was 28.80 kg (±4.93 kg) at the beginning of the experiment and were approximately eight months old. The bucks were castrated at three months of age. The animals were divided into two groups: control (N=10) and treated (N=10). All animals were kept under the same conditions and fed according to a system developed by the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) in France, adapted to the nutritional value of the feed used in Poland [

25]. The basal diet was the same for both groups. The detailed information on the diets was presented in paper [

24].

The bucks in the treated group were supplemented with 1.6 g/day of a dry extract mixture of turmeric and rosemary in a ratio of 896:19 (Selko® AOmix, Trouw Nutrition Polska sp. z o.o., Grodzisk Mazowiecki, Poland). The supplement was packaged in starch capsules and administered orally before the morning feed. Detailed information on dietary supplementation, growth performance, meat quality, lipid metabolism and immune system gene expression of the two groups of animals has been reported previously [

22,

23,

24].

2.2. Samples

At the end of the experiment (i.e. after 124 days),The blood samples were collected from the jugular vein immediately after sacrifice. The collection was performed into separate tubes containing coagulation activator for each animal (Sarstedt AG & Co., Nümbrecht, Germany). After two hours, the blood samples were centrifuged for serum collection. The blood serum was stored at -20°C for further analysis.

2.3. Biochemical Assays

TBARS assay for lipid peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation was determined using the malonic dialdehyde (MDA) method proposed by Buege and Aust [

26], based on measuring the concentration of 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). Results were expressed as nmol per mL.

The protein carbonyl derivative assay. OMPs level was determined by protein carbonyl derivative assay. The resulting carbonyl derivatives of amino acids were reacted with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNFH) according to Reznick and Packer [

27], as modified by [

28]. Carbonyl groups were quantified spectrophotometrically at 370 nm and 430 nm (for aldehyde derivatives, AD OMP and ketone derivatives, KD OMP, respectively) and results were expressed as nmol per mL.

Superoxide dismutase activity. SOD activity was determined according to [

29]. Briefly, the ability of SOD to dismutate superoxide generated during the auto-oxidation of quercetin was measured in an alkaline medium (pH 10.0). The resulting activity was expressed as units of SOD per mL.

Catalase activity. CAT activity was determined by measuring the reduction of H2O2 in the reaction mixture at a wavelength of 410 nm, as described by [

30]. One unit of CAT activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to reduce 1 μmol H

2O

2 per minute per mL.

Glutathione reductase activity. The activity of GR was measured according to [

31] with a few modifications. GR activity was expressed as nmol NADPH2 per minute per mL.

Glutathione peroxidase activity. GPx activity was determined by observing non-enzymatic consumption of the reacting substrate GSH at 412 nm absorbance after incubation with 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) according to [

32]. The resultant GPx activity was expressed as μmol GSH per minute per mL.

Total antioxidant capacity. TAC was assessed by quantification of TBARS after oxidation of Tween-80 [

33]. This level was determined spectrophotometrically at 532 nm. Inhibiting Fe2+/ascorbate-induced oxidation of Tween-80 resulted in decreased TBARS levels. The TAC content in the sample (%) was calculated relative to blank absorbance.

Ceruloplasmin (CP) assays. CP was determined using the Ravin method in 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) and 0.5% p-phenylenediamine at 540 nm according Kamyshnikov [

34]. The results were expressed as mg per %.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed with Statistica software 13.3 (TIBCO, USA). Data for both the control and supplementation groups were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). The mean values of the control and supplementation groups were compared using the independent samples t-test. The relationships between different biochemical parameters within each group, i.e. the strength and direction of the linear relationships between pairs of variables, were determined with Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r); these were calculated separately for pairs of parameters within each group. The significance of the correlations was assessed using the corresponding P-values, with P<0.05 indicating a significant correlation.

3. Results

3.1. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

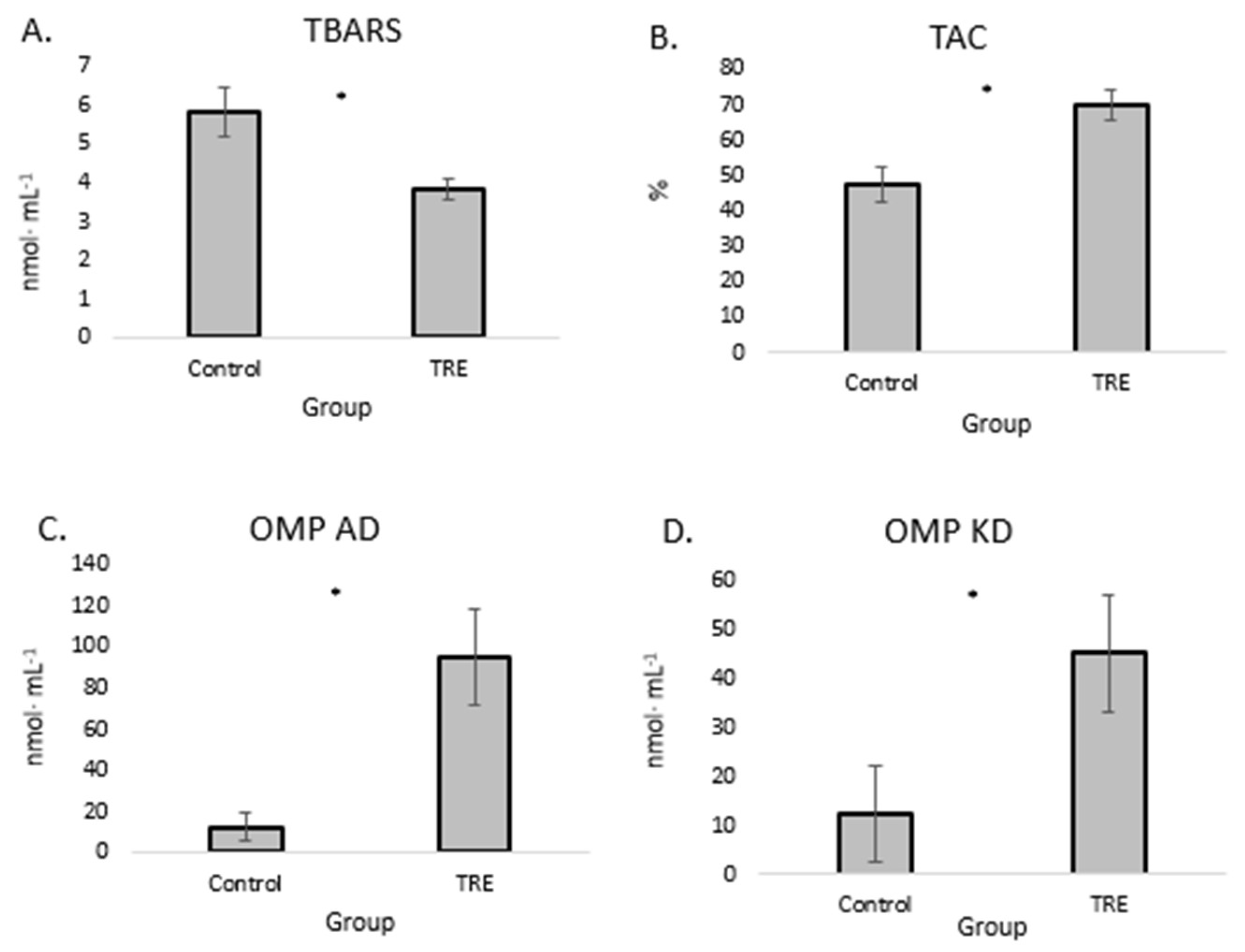

Our present findings indicate a significant decrease in TBARS level in young PWI castrated bucks after turmeric-rosemary extract supplementation (

Figure 1, A), accompanied by a significant increase in total antioxidant capacity (TAC) (

Figure 1, B). In addition, supplementation was associated with a significant increase in aldehydic derivatives of oxidatively modified proteins (OMP AD) (

Figure 1, C) and ketonic derivatives of oxidatively modified proteins (OMP KD) (

Figure 1, D) levels in the serum.

3.2. Antioxidant Enzymes

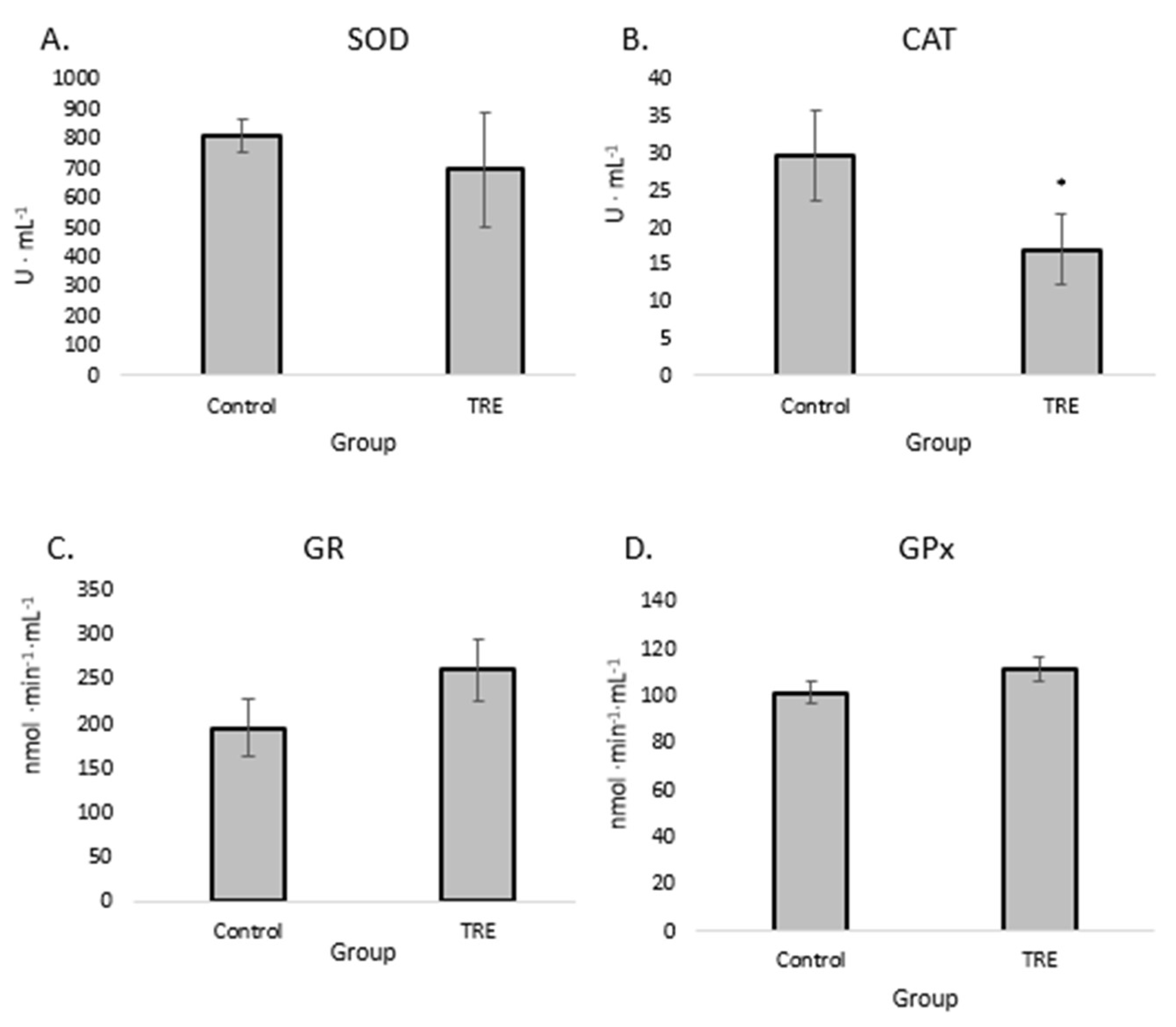

The effect of supplementation on the activity of the antioxidant enzymes SOD (

Figure 2 A), CAT (

Figure 2 B) and GPx (

Figure 2 C) is given; these are responsible for neutralizing ROS, which can cause lipid peroxidation, oxidative modification of proteins and DNA damage. Interestingly, while SOD, GPx and GR (

Figure 2, C) activity did not change after supplementation, CAT activity was significantly reduced.

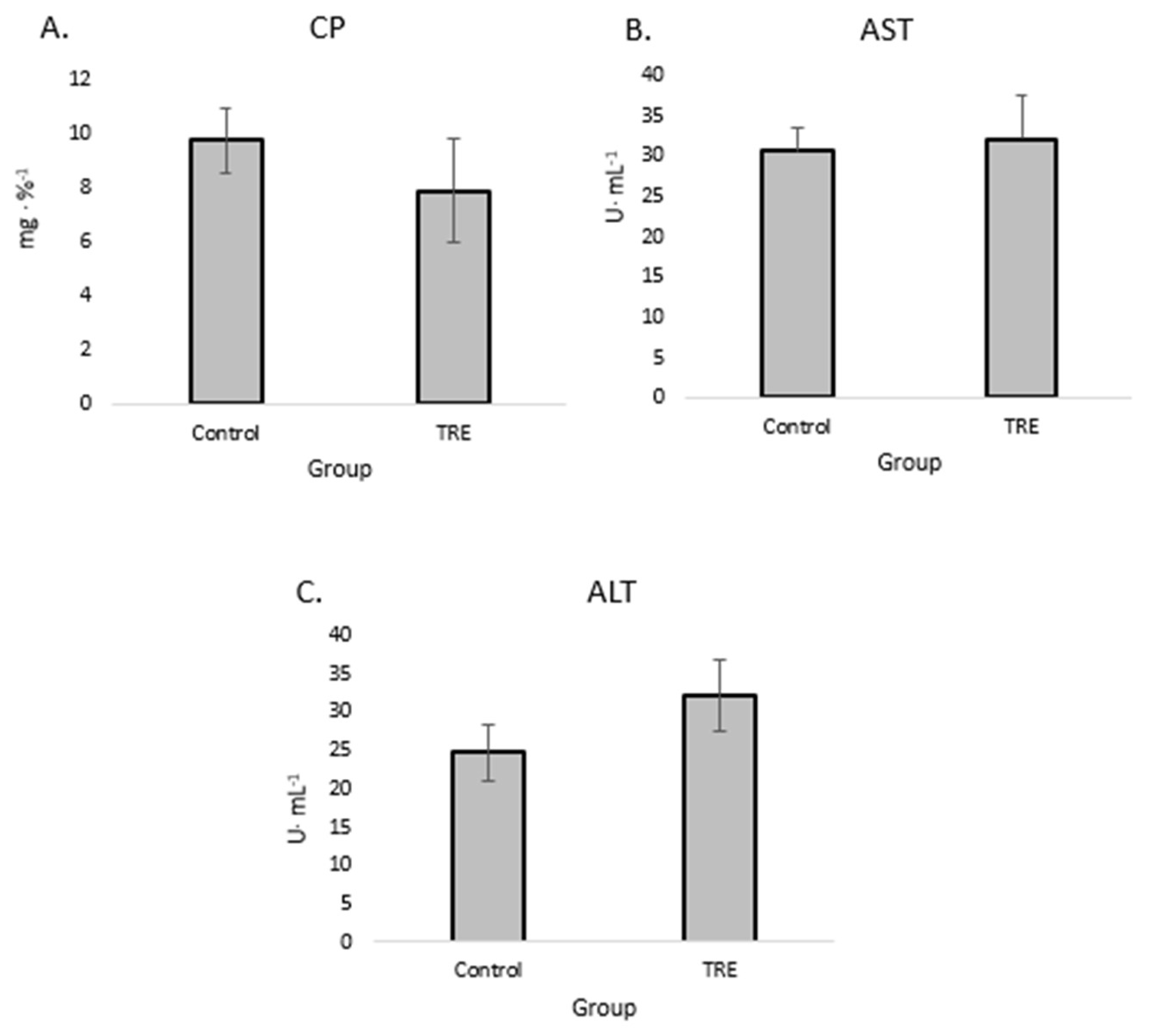

3.3. Biochemical Parameters

The results of our analyses of CP, ALT, and AST are shown in

Figure 3. No statistically significant changes in the levels of ALT and AST were observed in our study.

3.4. Correlations

The correlations (

Table 1) between OMP AD and AST (r=-0.652, p=0.030), GPx and AST (r=0.764, p=0.006), CP and GR (r=0.819, p=0.002) were noted in the control group. In the treated group we noted dependence between TBARS and ALT (r=0.614, p=0.004), TAC in two parameters between OMP AD (r=-0.788, p=0.004) and OMP KD (r=0.744, p=0.004) accordingly, OMP KD and GR ( r=0.626, p=0.040).

4. Discussion

Our analyses yielded valuable data regarding the effects of the tested turmeric and rosemary mixture on health and antioxidant status of blood. Not only is this important for future research but it also has practical implications in Veterinary Science. It is important to understand the effect of supplementation on the antioxidant status of animals[

35]. Lipid peroxidation and oxidative protein modifications are critical indicators of oxidative stress and its defenses. It is well known that lipid peroxidation can damage cell membranes, resulting in various diseases and inflammatory conditions; it can also be used to indicate the level of oxidative stress in blood serum by measuring the level of TBARS. Our findings indicate that supplementation with compounds known to have antioxidant properties resulted in a decrease in lipid peroxidation and an increase in TAC. This can be attributed to the activation of antioxidant pathways and improved neutralisation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Indeed, previous studies have noted that the antioxidants present in turmeric and rosemary extracts enhance natural defence mechanisms, leading to a reduction in oxidative damage to lipids [

20,

21]. This increase in the levels of OMP AD and OMP KD may result from complex molecular processes such as induction of protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, activation of oxidative stress-related signalling pathways and regulation of antioxidant pathways. The reduction in lipoperoxidation and increase in TAC observed after supplementation may be due to activation of antioxidant pathways and improved neutralization of ROS.

Turmeric is known to contain a range of carbohydrates, essential oils, fatty acids, curcuminoids (curcumin, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin), polypeptides such as turmeric, sugars, proteins and resins [

36]. The active ingredient is believed to be curcumin, which is extracted from the powder of the dried rhizomes of

Curcuma longa and has a variety of chemical, biological and pharmacological properties. In addition to its antioxidant potential, curcumin has been found to have various anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antifibrotic and immunomodulatory properties and appears to be effective against cancer and diabetes [

17,

37]. Similar properties have also been attributed to demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin [

18], and the turmerone and zingiberene in turmeric essential oils, have also demonstrated antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [

18,

19]. As such, turmeric appears to be valuable not only as a spice but also as a dietary supplement.

Rosemary is an evergreen perennial medicinal plant of the

Lamiaceae family. It is used in medicine, aromatherapy, perfumery and as a natural preservative in the food and cosmetics industries [

38]. The leaves, shoots and whole plant extract are valued as a functional food (antioxidant) and herbal nutraceutical. Rosemary has a range of medicinal properties, which have been attributed to its complement of bioactive compounds [

39]. In particular, it produces various phenolic acids, such as rosmarinic acid, with powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antibacterial properties. It is also a potent source of terpenoids such as carnosic acid, carnosol and urosole: carnosic acid is a potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compound, carnosol has antioxidant, anticancer and anti-inflammatory activity, and urosole has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. Its essential oils such as 1,8-cyneol (eucalyptol) and camphor also have antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory properties, making rosemary a popular ingredient in natural medicines and cosmetics [

9]. In addition, these compounds are all effective scavengers of ROS and RNS. Their presence, hence, increases antioxidant capacity and protects cellular components from oxidative stress [

36].

Our findings also indicate elevated oxidative modification of proteins after supplementation. This can be explained by the increased production of aldehyde and ketone derivatives as a result of lipid peroxidation. These reactive aldehyde and ketone products can interact with and modify protein structures, thus potentially altering their biological functions. Despite lowering lipid peroxidation, these products can increase protein oxidation. This suggests a complex interplay between lipid and protein oxidation, where increased lipid protection may simultaneously increase protein oxidative modifications due to the abundance of lipid peroxidation by-products.

TAC analysis is an effective measure of the ability of an organism to neutralise free radicals, such as ROS and RNS, and various other oxidative substances that can cause cell and tissue damage. TAC is used to estimate the complex sum of various components, including antioxidant enzymes (such as SOD, CAT, GPx and GR) and low molecular weight antioxidants (such as vitamins C and E, glutathione)[

40]. In addition, TAC is a crucial parameter in animal studies and in the evaluation of new feed additives, because it assesses the organism’s ability to defend itself against oxidative stress induced by various environmental factors, including diet and housing conditions [

41,

42]. Supplementation with new feed additives, such as plant extracts, containing high concentrations of antioxidants can influence the TAC of the livestock [

40]; this parameter can also be used to determine the effectiveness of supplementation and potential health benefits. Our present findings indicate a decrease in lipid peroxidation and an increase in TAC following administration of antioxidant compounds. This may be due to the activation of antioxidant pathways by the bioactive components present in turmeric and rosemary; these are thought to enhance the defense against oxidative stress by increasing antioxidant enzyme activity and boosting endogenous antioxidant levels. This reduction of oxidative lipid damage contributes to an overall improvement in oxidative balance.

Our findings also indicate significant changes in SOD CAT and GPx activity, as well as in important biochemical markers, i.e. ALT and AST activities and CP levels. These parameters provide insight into the mechanisms by which the body responds to oxidative stress. Antioxidant enzymes have key roles in maintaining oxidative homeostasis and protecting cells from damage caused by ROS, thus ensuring cellular health and preventing oxidative stress-related diseases. This reduction may be due to various mechanisms, one of which being ROS formation by the active compounds in turmeric and rosemary; these can modify proteins, including CAT. However, further studies are needed to better understand the specific interactions between these compounds and CAT and their effects on antioxidant function in PWI bucks. CP serves as the primary transporter of copper, which is essential for many vital enzymatic redox reactions, while alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) play key roles in amino acid metabolism. It was known that elevated serum levels of ALT and AST often indicate liver and myocardial cell damage, with ALT being more specific for liver damage and AST of myocardial damage. These results suggest the absence of tissue damage, indicating that supplementation had a positive result for health, with no adverse effects associated with liver function or oxidative stress, and high antioxidant potential. This suggests that the supplemented compounds effectively enhanced antioxidant defences without adversely affecting liver enzyme activities, reflecting a favorable biochemical response.

The correlation analysis confirmed that correlation dependencies were higher in the experimental group than the controls. There are no results presented in the available literature regarding the relationship between the levels of OMPs, TAC and antioxidant enzymes activity in goat organs or tissues. However, our findings suggest a complex interplay between lipid protection and protein oxidation processes.

As a whole, our findings demonstrate that while enhancing lipid defence mechanisms may reduce lipid peroxidation, it may also increase the level of oxidative modification in proteins, probably due to the accumulation of lipid peroxidation metabolites. This dual effect highlights the intricate balance and interactions within oxidative pathways in goats, which are affected by supplementation with Curcuma longa and Rosmarinus officinalis extract mixture. These observations are further supported by the correlation analysis between the control and experimental groups, which highlight more interdependencies in the experimental group. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how dietary interventions affect oxidative stress markers and biochemical pathways in PWI goats.

5. Conclusions

Supplementation with the turmeric-rosemary mixture reduced lipoperoxidation and increased TAC in the tested goat bucks. This may be attributed to the activation of antioxidant pathways and improved neutralization of ROS. However, the observed increase in OMPs may be due to increased levels of aldehyde and ketone derivatives, specifically OMP AD and OMP KD, produced by lipid peroxidation. These derivatives can alter protein structures and interfere with their biological functions.

The lack of changes in SOD, GPx, GR, CP, ALT or AST activity, and lower CAT activity, suggest that supplementation effectively enhanced antioxidant defenses without adversely affecting liver enzyme activities: a favorable biochemical response.

Future studies are needed to determine the effect of different doses of the turmeric-rosemary dry mixture. These studies should examine other biochemical parameters in blood serum. The findings would provide a clearer indication of the dose that would improve health and it not lead to the increased levels of aldehyde and ketone derivatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.U. and E.B.; Methodology, N.K. and H.T.; Software, N.K.; Validation, D.M.U and E.B.; Formal Analysis, D.M.U. and E.B.; Investigation, D.M.U.; Resources, K.R., E.K-G., P.B. and M.M.; Data Curation, D.M.U. and E.B.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.M.U. and N.K.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.C. and J.K.; Visualization, D.M.U., N.K. and H.T.; Supervision, E.B.; Project Administration, D.M.U. and E.B.; Funding Acquisition, D.M.U., J.K. and E.B.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Center, Poland, Grants Number: 2016/21/N/NZ9/01508 and 2013/09/B/NZ6/03514.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the he 3rd Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation in Warsaw; (permission No. 31/2013, 22 May 2013)

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Danuta Słoniewska, Grażyna Faliszewska and Maria Buza for their help with the laboratory work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ruvuga, P.R.; Maleko, D.D. Dairy goats’ management and performance under smallholder farming systems in Eastern Africa: The systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Anim Health Prod 2023, 55, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, P. Udder Health for Dairy Goats. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 2021, 37, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, E.; Goerlich, V.C.; van den Brom, R.; Giersberg, M.F.; Arndt, S.S.; Rodenburg, T.B. Perspectives for Buck Kids in Dairy Goat Farming. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 662102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnampalam, E.N.; Priyashantha, H.; Vidanarachchi, J.K.; Kiani, A.; Holman, B.W.B. Effects of Nutritional Factors on Fat Content, Fatty Acid Composition, and Sensorial Properties of Meat and Milk from Domesticated Ruminants: An Overview. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zi, X.J.; Lv, R.L.; Zhang, L.D.; Ou, W.J.; Chen, S.B.; Hou, G.Y.; Zhou, H.L. Cassava Foliage Effects on Antioxidant Capacity, Growth, Immunity, and Ruminal Microbial Metabolism in Hainan Black Goats. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Usman, S.; Li, Q.; Li, F.H.; Zhang, X.; Nussio, L.G.; Guo, X.S. Effects of antioxidant-rich inoculated alfalfa silage on rumen fermentation, antioxidant and immunity status, and mammary gland gene expression in dairy goats. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2024, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onjai-Uea, N.; Paengkoum, S.; Taethaisong, N.; Thongpea, S.; Paengkoum, P. Enhancing Milk Quality and Antioxidant Status in Lactating Dairy Goats through the Dietary Incorporation of Purple Napier Grass Silage. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarverdi Sarabi, S.; Fattah, A.; Papi, N.; Ebrahimi, M.S.R. Impact of corn silage substitution for dry alfalfa on milk fatty acid profile, nitrogen utilization, plasma biochemical markers, rumen fermentation, and antioxidant capacity in Mahabadi lactating goats. Vet Anim Sci 2023, 22, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Mohammad, T.; Rub, M.A.; Raza, A.; Azum, N.; Yadav, D.K.; Hassan, M.I.; Asiri, A.M. Biomedical features and therapeutic potential of rosmarinic acid. Arch Pharm Res 2022, 45, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zou, L.; Sun, H.; Peng, J.; Gao, C.; Bao, L.; Ji, R.; Jin, Y.; Sun, S. A Review of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Rosmarinic Acid on Inflammatory Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamponi, S.; Baratto, M.C.; Miraldi, E.; Baini, G.; Biagi, M. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant, Anti-Proliferative, Anticoagulant and Mutagenic Effects of a Hydroalcoholic Extract of Tuscan Rosmarinus officinalis. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquiza-Lopez, A.; Alvarez-Rivera, G.; Ballesteros-Vivas, D.; Cifuentes, A.; Del Villar-Martinez, A.A. Metabolite Profiling of Rosemary Cell Lines with Antiproliferative Potential against Human HT-29 Colon Cancer Cells. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2021, 76, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Jeong, Y.I.; Lee, T.H.; Jung, I.D.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, C.M.; Kim, J.I.; Joo, H.; Lee, J.D.; Park, Y.M. Rosmarinic acid inhibits indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in murine dendritic cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2007, 73, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaihre, Y.R.; Iwamoto, A.; Oogai, S.; Hamajima, H.; Tsuge, K.; Nagata, Y.; Yanagita, T. Perilla pomace obtained from four different varieties have different levels and types of polyphenols and anti-allergic activity. Cytotechnology 2022, 74, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lataliza, A.A.B.; de Assis, P.M.; da Rocha Laurindo, L.; Goncalves, E.C.D.; Raposo, N.R.B.; Dutra, R.C. Antidepressant-like effect of rosmarinic acid during LPS-induced neuroinflammatory model: The potential role of cannabinoid receptors/PPAR-gamma signaling pathway. Phytother Res 2021, 35, 6974–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Yousef, M.; Tsiani, E. Anticancer Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract and Rosemary Extract Polyphenols. Nutrients 2016, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Akter, J.; Hossain, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, P.; Goswami, C.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Miyamoto, A. Anti-Inflammatory, Wound Healing, and Anti-Diabetic Effects of Pure Active Compounds Present in the Ryudai Gold Variety of Curcuma longa. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W. The Golden Spice for Life: Turmeric with the Pharmacological Benefits of Curcuminoids Components, Including Curcumin, Bisdemethoxycurcumin, and Demethoxycurcumins. Curr Org Synth 2024, 21, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.Y.; Ho, C.T.; Pan, M.H. The therapeutic potential of curcumin and its related substances in turmeric: From raw material selection to application strategies. J Food Drug Anal 2023, 31, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, L.W.; de Oliveira, J.R.; Camargo, S.E.A.; de Oliveira, L.D. Curcuma longa L. (turmeric), Rosmarinus officinalis L. (rosemary), and Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme) extracts aid murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) to fight Streptococcus mutans during in vitro infection. Arch Microbiol 2020, 202, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, C.; Fernandes, D.; Silva, I.; Mateus, V. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Rosmarinus officinalis in Preclinical In Vivo Models of Inflammation. Molecules 2022, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbańska, D.M.; Pawlik, M.; Korwin-Kossakowska, A.; Czopowicz, M.; Rutkowska, K.; Kawecka-Grochocka, E.; Mickiewicz, M.; Kaba, J.; Bagnicka, E. Effect of Supplementation with and Extract Mixture on Acute Phase Protein, Cathelicidin, Defensin and Cytolytic Protein Gene Expression in the Livers of Young Castrated Polish White Improved Bucks. Genes 2023a, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbańska, D.M.; Pawlik, M.; Korwin-Kossakowska, A.; Rutkowska, K.; Kawecka-Grochocka, E.; Czopowicz, M.; Mickiewicz, M.; Kaba, J.; Bagnicka, E. The Expression of Selected Cytokine Genes in the Livers of Young Castrated Bucks after Supplementation with a Mixture of Dry and Extracts. Animals 2023b, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbańska, D.M.; Pawlik, M.; Korwin-Kossakowska, A.; Rutkowska, K.; Kawecka-Grochocka, E.; Czopowicz, M.; Mickiewicz, M.; Kaba, J.; Bagnicka, E. Effect of supplementation with a mixture of and extracts on growth performance, meat quality and lipid metabolism gene expressions in young castrated Polish White Improved bucks. Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences 2024, 33, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzóska, F.; Kowalski, Z.M.; Osięgłowski, S.; Strzetelski, J. IZ PIB-INRA Nutritional Recommendations for Ruminants and Tables of Nutritional Value of Feeds; [Zalecenia Żywieniowe dla Przeżuwaczy i Tabele Wartości Pokarmowej Pasz]; Strzetelski, J., Eds.; Foundation of the Institute of Animal Production of the National Research Institute Patronus Animalium: 2014, Warsaw, Poland, ISBN 978-83-938377-0-0.

- Buege, J.A.; Aust, S.D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation

. Methods Enzymol 1978, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Reznick, A.Z.; Packer, L. Oxidative damage to proteins: Spectrophotometric method for carbonyl assay. Methods in enzymology 1994, 233, 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva, O.V.; Shandrenko, S.H. Modification of spectrophotometric method for determination of protein carbonyl groups. Ukr Biokhim Zh 2012, 84, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kostiuk, V.A.; Potapovich, A.I.; Kovaleva, Z.V. A simple and sensitive method of determination of superoxide dismutase activity based on the reaction of quercetin oxidation. Vopr Med Khim 1990, 36, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Koroliuk, M.A.; Ivanova, L.I.; Maiorova, I.G.; Tokarev, V.E. A method of determining catalase activity. Lab Delo(1) 1988, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Glatzle, D.; Vuilleumier, J.P.; Weber, F.; Decker, K. Glutathione reductase test with whole blood, a convenient procedure for the assessment of the riboflavin status in humans. Experientia 1974, 30, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, V.M. A simple and specific method for determining glutathione peroxidase activity in erythrocytes. Lab Delo(12) 1986, 724-727.

- Galaktionova, L.P. , Molchanov, A.V., El’chaninova, S.A., Varshavskiĭ, B.I. Lipid peroxidation in patients with gastric and duodenal peptic ulcers. Klinicheskaia laboratornaia diagnostika 1998, 6, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kamyshnikov, V.S. Reference book on clinic and biochemical researches and laboratory diagnostics. MEDpress-inform 2004, Moscow.

- Aldian, D.; Harisa, L.D.; Mitsuishi, H.; Tian, K.; Iwasawa, A.; Yayota, M. Diverse forage improves lipid metabolism and antioxidant capacity in goats, as revealed by metabolomics. Animal 2023, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocaadam, B.; Sanlier, N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Swelum, A.A.; Arif, M.; Abo Ghanima, M.M.; Shukry, M.; Noreldin, A.; Taha, A.E.; El-Tarabily, K.A. Curcumin, the active substance of turmeric: Its effects on health and ways to improve its bioavailability. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 5747–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagawany, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Farag, M.R.; Gopi, M.; Karthik, K.; Malik, Y.S.; Dhama, K. Rosmarinic acid: Modes of action, medicinal values and health benefits. Anim Health Res Rev 2017, 18, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, K. Rosemary: An overview of potential health benefits. Nutrition Today 51.2 2016, 102-112.

- Silvestrini, A.; Meucci, E.; Ricerca, B.M.; Mancini, A. Total Antioxidant Capacity: Biochemical Aspects and Clinical Significance. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobiecka, M.; Krol, J.; Brodziak, A. Antioxidant Activity of Milk and Dairy Products. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosz, G. Total antioxidant capacity. Adv Clin Chem 2003, 37, 219–292. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).