1. Introduction

Shield machines, as a kind of tunnel driving equipment with fast speed, small impact on the surroundings, safety, and low cost, have been widely promoted in subways, highways, urban pipe galleries, and other fields in recent years. As the core component of the shield machine, disc cutters are installed on the surface of cutterhead, which use the tangential force brought about by the rotation of disc cutters to crush and cut hard rocks, so disc cutters will gradually wear out with the increase in the distance of advancement. Moreover, the frequency of wear of the cutters and other situations will significantly increase in the hard strata. However, since disc cutters are located in the front of the earth silo, it is difficult to directly observe the overall wear of disc cutters with the naked eye, and frequent opening of the silo to check the delay in the work schedule at the same time will produce a certain amount of safety hazards. There are two ways of judging the overall wear of disc cutters: the direct way and the indirect way. The direct way is through the experience of construction personnel, regular spot checks, or combined with sensors or special materials to assist detection. Although the auxiliary detection method is more accurate in recognizing wear, it has specific cost and equipment limitations [

1,

2]. The other is the indirect method, which detects blade wear indirectly through the primary propulsion data during shield propulsion.

Existing cutter wear detection methods are mainly categorized into three approaches: mechanism model, energy analysis, and data-driven methods.

The mechanistic approach models the rock fragmentation process through mechanical analysis and maps it to other digging parameters. Wang et al. [

3] used the displacement equation of the rock-breaking point on the cutter ring to construct a wear prediction model by combining the theoretical analysis of the cutter force and wear test. She et al. [

4] proposed a calibrated expression for the CSM model’s typical load, creating a theoretical model to predict cutter wear during rock breaking and identifying a quantitative link between the wear index and various factors. Yang et al. [

5] proposed a cutter wear coefficient and a calculation method based on track weight to accurately calculate the cutter wear under the non-homogeneous stratum based on the cutter wear model proposed by the Japanese Tunneling Association.

Many researchers started from the energy analysis point of view by monitoring the cutter’s temperature change or energy exchange on the disc cutter, which can effectively detect the wear of disc cutters. Wang et al. [

6] proposed and calculated the energy conversion coefficient and thrust distribution coefficient to predict disc cutter wear in shield tunneling. Yang et al. [

7] proposed a new method to predict the depth of disc cutter wear based on energy analysis according to the geometry of disc cutters and the relationship between the wear loss and the friction work. She et al. [

8] further estimated disc cutter wear by analyzing the conversion mechanism between disc cutter wear energy and wear capacity, establishing the relationship between the energy conversion relationship and rock properties.

Many data-driven methods have emerged with the wide application of machine learning and even deep learning methods in the field of machinery fault diagnosis, along with sensor technology innovation. These methods learn wear-related features of disc cutters by utilizing the data collected by the sensors at the shield site, combined with machine learning and deep learning models, and thus finally achieve the detection or prediction of wear. Kim, Y et al. [

9] used excavation data collected during shield tunneling to predict the wear of disc cutters using five different machine-learning techniques. Kilic K et al. [

10] employed a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) model to estimate the wear of each cutter in a real-time manner using data collected by soil pressure balance shield during tunneling in soft ground to perform cutter wear prediction. Kim. Y et al. [

11] classified the abnormal wear state of disc cutters during shield tunneling by comparing the machine learning classification methods such as KNN, SVM, and DT to assess the need for disc cutter replacement. Zhang N et al. [

1] developed a model that integrates a 1D-CNN, a Gated Recurrent Unit Network (GRU) and used a multi-step forward prediction approach to achieve the prediction of tool wear for soil pressure balance shields. Liu Y et al. [

2] used a kernel support vector machine (KSVM) to construct a mapping model between disc cutter replacement judgments and established features to determine whether disc cutter replacement is currently required.

However, although the mechanistic analysis method can more accurately predict the amount of disc cutter wear under normal digging conditions, it is often limited to the estimation before digging and the situation during regular digging. In contrast, the energy analysis method can detect abnormal wear. However, it is prone to be interfered with by other abnormal events, which reduces identification accuracy. The field data-driven method can overcome the above shortcomings simultaneously, so more and more scholars are gradually adopting the data-driven method to detect disc cutter wear. Most of the existing data-driven methods predict the wear of each cutter, rely on specific geological parameters, or can only realize the prediction of normal advancement wear of disc cutters. In the tunneling process, there is no need to monitor each tool’s status, and the cutter’s overall cutting performance is more important than the specific wear value of a single cutter. [

2] Therefore, detecting and determining whether the current cutter needs to be opened and replaced is more practical. In addition, composite strata are usually composed of many different soil and rock types, such as sand, clay, gravel, soft rock, and hard rock. These strata have pretty different physical and mechanical properties, and their distribution and thickness change more frequently, resulting in the continuous adjustment of the parameters to adapt to the shield machine’s different geologic conditions in tunneling, making disc cutters more prone to abnormal wear and tear of disc cutters. Therefore, detecting wear state of disc cutters in the composite strata is more complex than in single homogeneous strata. [

12]

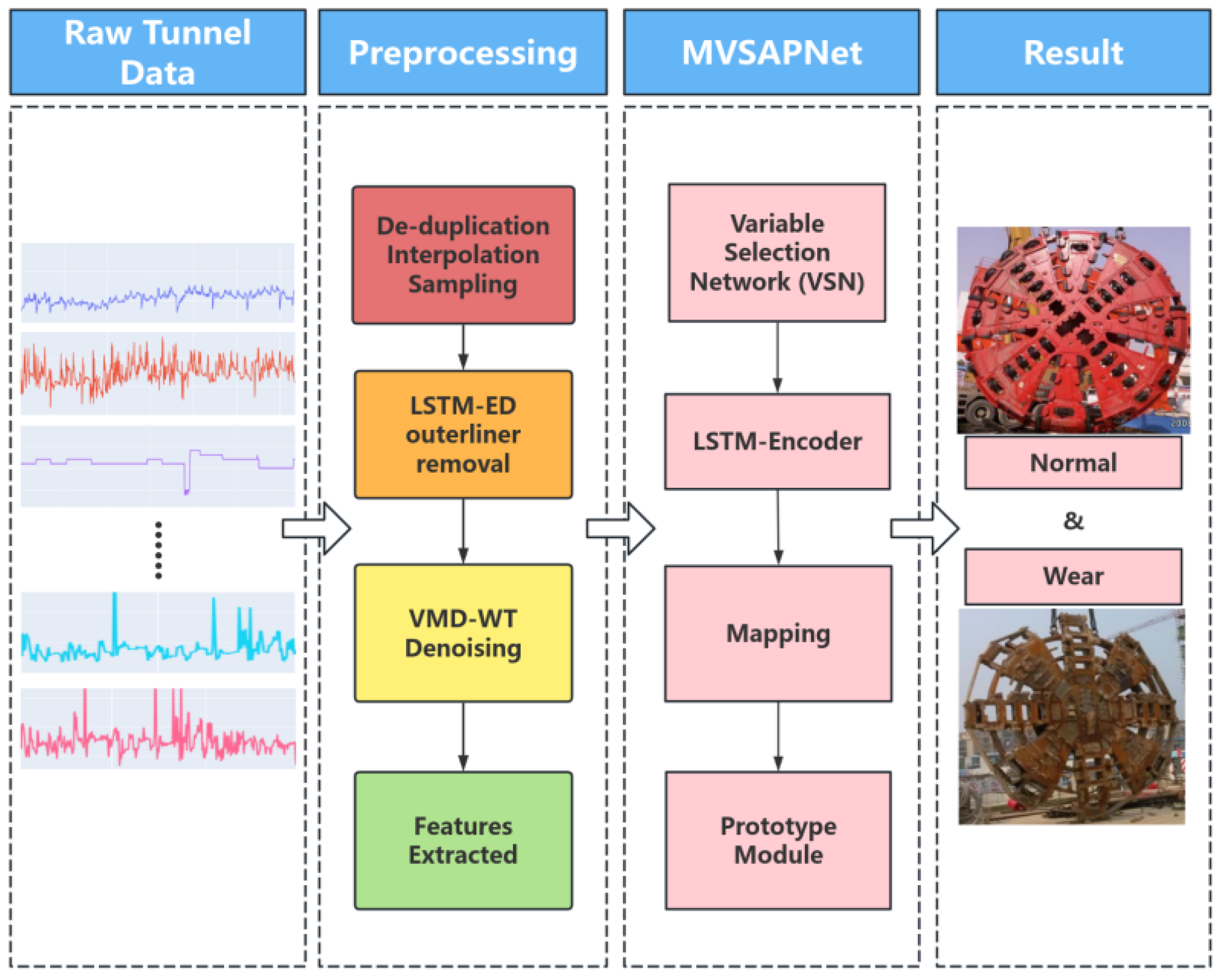

Based on the above-mentioned problems, this paper proposes a multivariate selection attention prototype network(MVSAPNet) driven by sensor data collected during the shield tunneling process, which detects cutter head wear state by comparing the distance of time-dependent features to the center of each class. The specific contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) A new prototype network for variable selection is proposed to classify unbalanced disc cutter wear data, and the proposed model is more effective than other classification models in detecting the data scenarios of the Ma Wan Cross-Sea Tunnel project. (2) Multiple preprocessing methods are used to extract the relevant features of the data to ensure that the model performs well on the disc cutter wear state detection task in composite strata. (3) By obtaining the intermediate parameters and interclass distance of the model, it was found that real-time parameters such as cutter speed, penetration, FPI, and TPI change significantly when the disc cutter wear occurs. This verifies the accuracy of the long-term experience accumulated by the actual constructors and provides a practical research idea for predicting disc cutter wear.

3. Results

3.1. Engineering Background

The raw data used in this paper are from the shield advancement data of the Ma Wan Cross-Sea Tunnel project in Shenzhen, China, during the period from 13:32 on August 9, 2022, to 0:48 on October 11, 2022, using the Herrenknecht large-diameter slurry pressure balance shield, and passing through the geological conditions of the upper-soft and lower-hard composite strata (upper fully-weathered mixed granite, middle earth/massive strongly weathered granite, lower slightly-weathered mixed granite) transitioning to hard-rock strata (slightly-weathered mixed granite). Since the shield propulsion is carried out in rings, there is a long stopping period between rings for assembling the pipe pieces and the digging process takes up only a tiny part of the time. The wear process occurs almost exclusively during the digging when the disc cutter is rotating. It is necessary to extract the data in the digging working condition during this period for analysis. After extraction, 393,887 working state data were collected from the database. Due to the performance and failure of the sensor itself, there are some duplicated and missing data for the acquirement. Hence, the data needs to be de-duplicated and interpolated. After that, the data are sampled with a sampling interval of 20s, and 55,932 sequence data are obtained after processing. Based on the previous work and the observation of the actual sensor data available in the tunnel, 15 parameters are selected for analysis, and the details are listed in

Table 2. Penetration indicates the distance advanced by rotation of the disc cutter and is used to reflect the overall cutting capacity of the disc, which is defined by

.

v is mean excavation speed and

f is cutterhead speed. FPI reflects the positive force required during cutter boring, which is defined by

.

F denotes total thrust. TPI reflects the tangential force required during cutter boring, which is defined by

.

T denotes cutterhead torque.

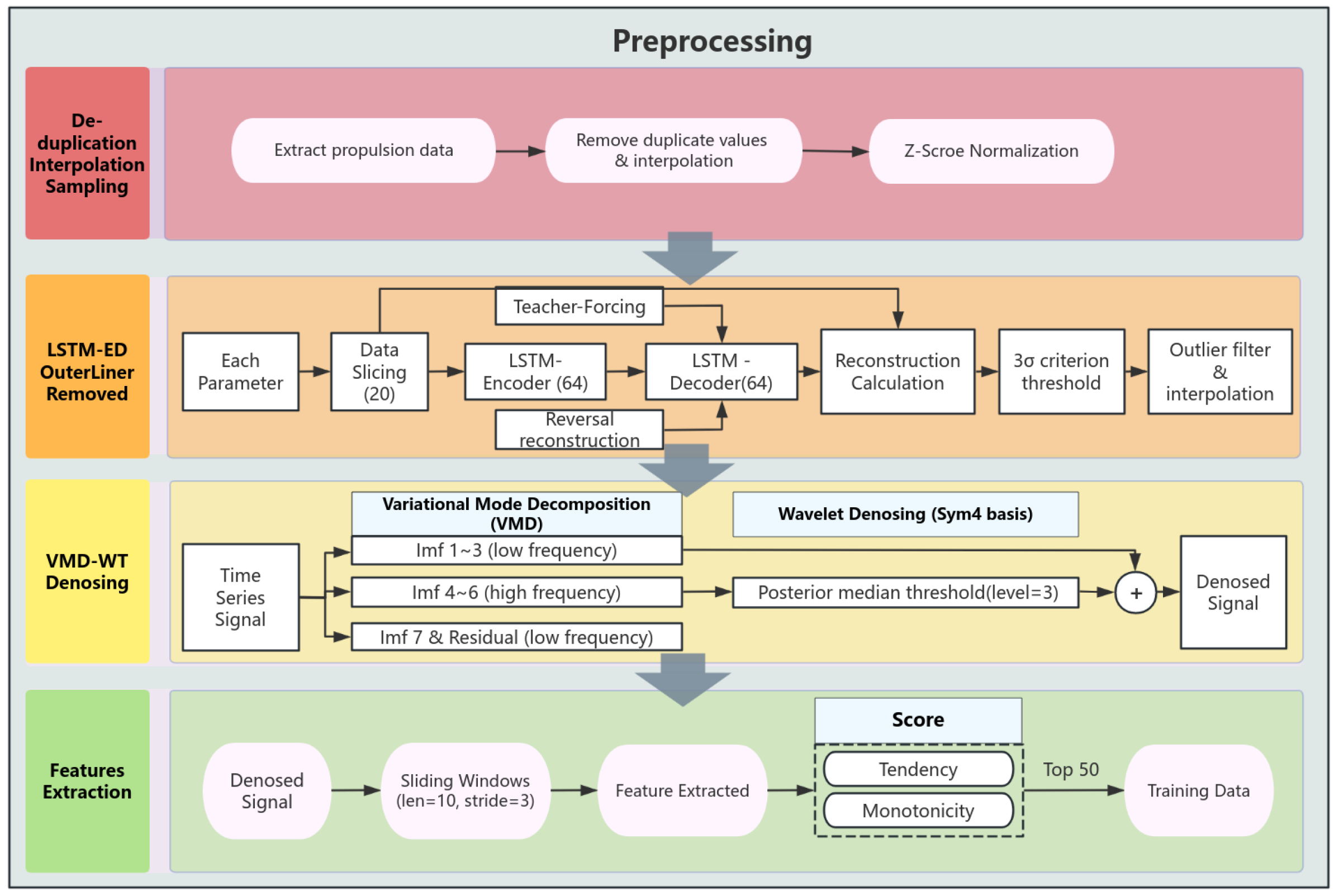

3.2. Data Preprocessing

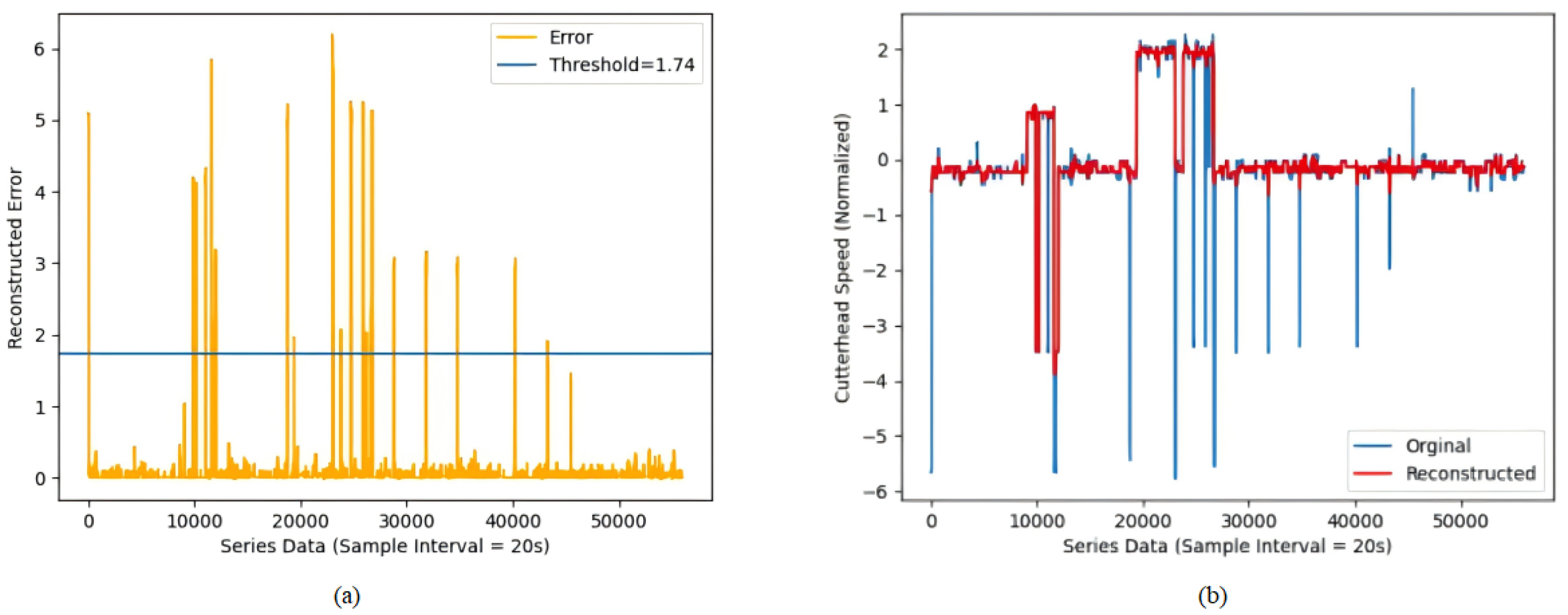

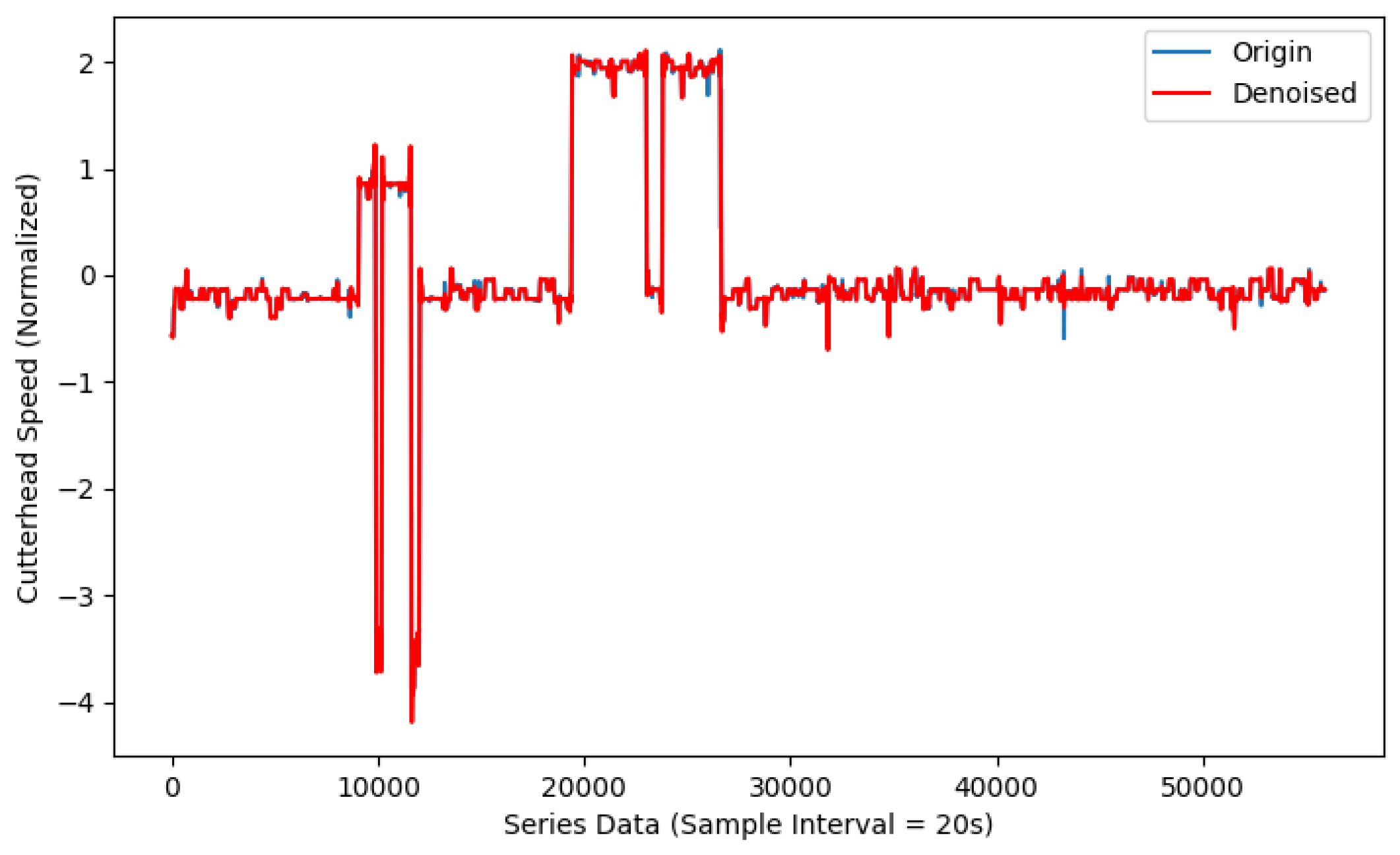

After that, the input data are normalized and divided into small sub-windows for reconstruction using a sliding window of length 15 and step size 1, resulting in a total of 55,917 windows. All the windows were input into the LSTM-ED model for training, where the LSTM hidden layer parameter was set to 64, and the number of layers was set to 1. The model was also optimized using the inverse-order reconstruction and teacher-forcing strategies. The cutterhead speed reconstruction results are shown in

Figure 4. using the Adam optimizer training and setting the learning rate to 0.001.

It can be seen that after filtering, the results appear significantly smoother, effectively addressing outliers and mitigating the impact of noise to a certain extent. Next step, the data are denoised by VMD-WT transform. This paper decomposes the shield parameters into 7 different IMFs, denoted as IMF1-IMF7, and setting the penalty term to 2000, where IMF7 has the highest center frequency. For IMF7 and the residuals of VMD decomposition can be eliminated due to the high-frequency noise and little contribution to the whole time series.

Figure 6 shows the comparison results with cutterhead speed.

Finally, time-domain features are extracted separately for each parameter through sliding windows which set window length as 10 and step size as 3. After feature extraction, 165 primary features were obtained.

Table 3 shows result of calculating trend and monotonicity scores for features. After that, the features with Top 50

th scores are selected as model inputs for training.

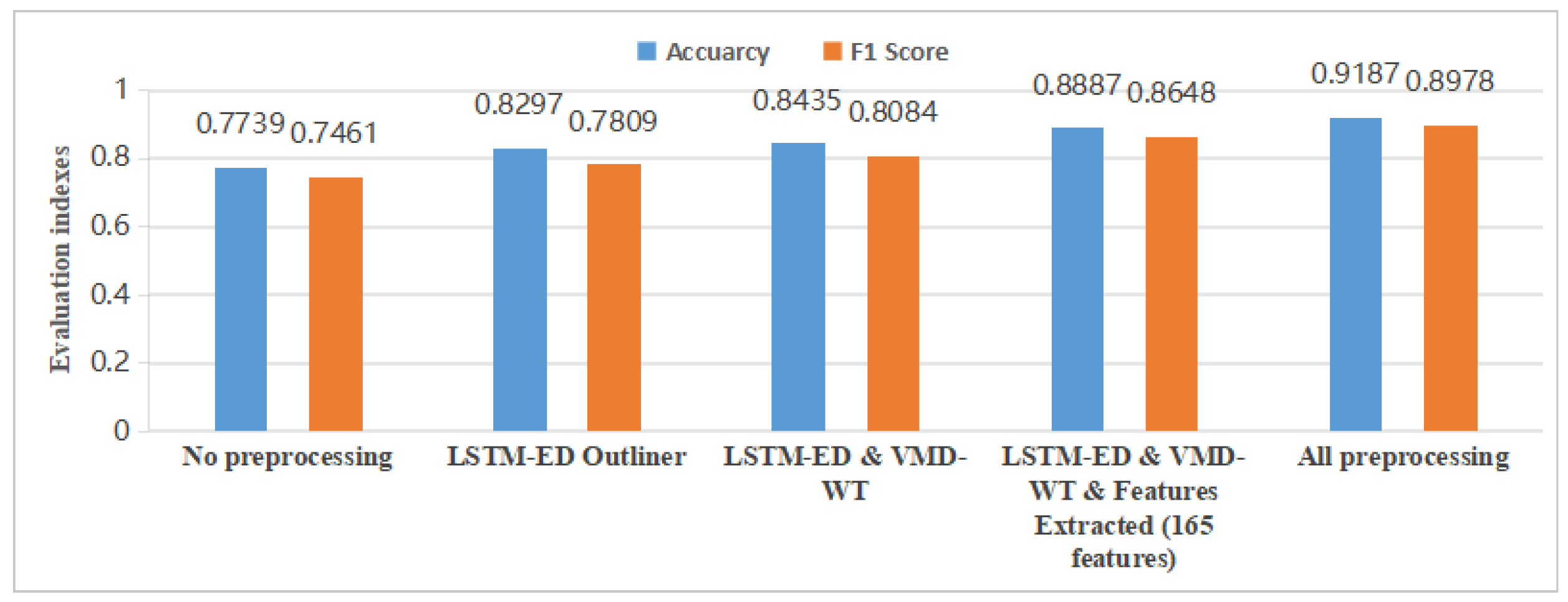

Since this paper adopts various methods to preprocess the shield acquisition data, to assess better the impact of each step in the preprocessing on the results, test the data obtained from each step in preprocessing is output separately with the model proposed by the paper.

Figure 6. shows the final experimental results, where the results of each step are obtained based on the previous step. It can be seen that compared to the initial feature selection achieved without preprocessing the data, the training effect of the data after preliminary processing is improved by about 14%, which may be due to the limited wear data samples that can be used for training, and it is challenging to train the data directly to obtain more generalized disc cutter wear features. In addition, it can be noted that compared with selecting all features, only using the top 50 features for training can still improve performance by about 2%. On the one hand, features other than the top 50 may impact the disc cutter wear detection effect less. On the other hand, too high dimensional data will reduce the computational efficiency while leading to dimensionality explosion, thus affecting the model’s overall performance.

3.3. Comparison Models

After preprocessing, 18668 trainable data were finally obtained. Considering the change in data distribution due to the gradual transition of the tunnel cut from the upper soft and lower hard strata to the hard rock strata during the acquisition of data for the segment, a total of 7348 pieces of data from one section of a complete upper soft and lower hard stratum and another section of a complete hard rock stratum were used as the training set, and the remaining 11320 pieces of data were used as the test set for inspection. Six disc cutter wear events occurred in the shield and two in the selected training data. For the classification detection model hyperparameters, the learning rate LR is set to 0.0001, the batch size is set to 64, the number of iterations is 200, the sliding window length is 20, the LSTM output layer size is 128, the dropout layer is 0.2, the attention dimension is set to 64, the gradient clipping is set to 0.2, the loss function adopts the cross-entropy loss function, and train with Adam optimizer.

The most commonly used metrics for the evaluation metrics of classification results are the accuracy and the f1-score. For shield data, since the disc cutter wear abnormality accounts for a small percentage of the overall dataset and the overall dataset is unbalanced, the f1-score is more reflective of the detection results, so we takes the f1-score as the main evaluation index of the model.

In order to show the advantages of the proposed model, we use important or newer deep learning models in the field of time series classification to compare, including (1) Recurrent-based networks: LSTM-FCN, ALSTM-FCN [

26] and BiLSTM. (2) Kernel-based networks: ResNet, InceptionTime [

27]. (3) Transformer-based networks: GTN [

28], TARNet. (4) Other types of networks: TapNet [

25].

Table 4 shows the experimental results.

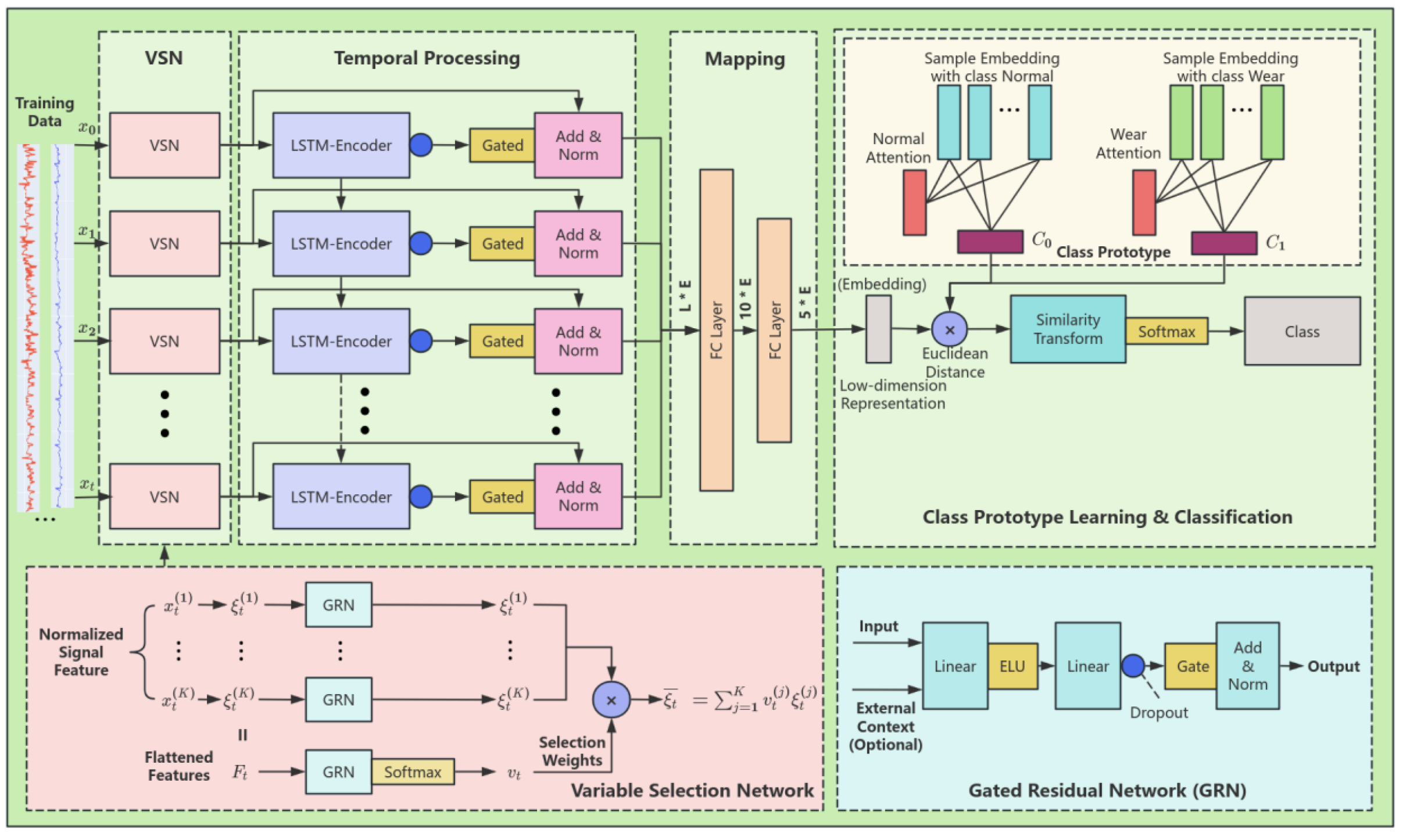

The results show that our proposed model performs better on the shield disc cutter wear dataset compared to several important baseline methods, with an accuracy of 0.9187 and an F1 score of 0.8978, higher than the experimental results of the other compared models. ALSTM-FCN works better compared to BiLSTM, probably because ALSTM-FCN employs an attentional approach to learn the importance of the input features of the shield data, which is more important than learning the bi-directional dependencies of the shield data. It is also found that the recurrent neural network is close to or even exceeds the relatively more complex kernel model on the shield disc cutter wear dataset. Maybe disc cutter wear data are more affected by time-dependent features in the long term, whereas kernel models are more concerned with numerical or shape-based features. Based on these points, it is expected that the transfomer-based network model outperforms the recurrent and kernel models, and the actual results align with this speculation. However, the transfomer-based model must be trained on a large amount of data to learn sufficient data features. Obtaining a large amount of wear data for the disc cutter wear is challenging. This data imbalance weakens the performance of transfomer-based model. Therefore, it can be seen that TapNet, which also employs a prototype-like network, is able to approach Transfomer’s model in terms of real-world detection results. The proposed model MVSAPNet, which introduces a variable selection network to strengthen the feature selection ability of the model, absorbs the ability of the recurrent neural network to learn the time-dependent characteristics and adopts the Prototype mechanism better to overcome the characteristics of the shield data imbalance, so it produces a better detection effect on the disc cutter wear dataset.

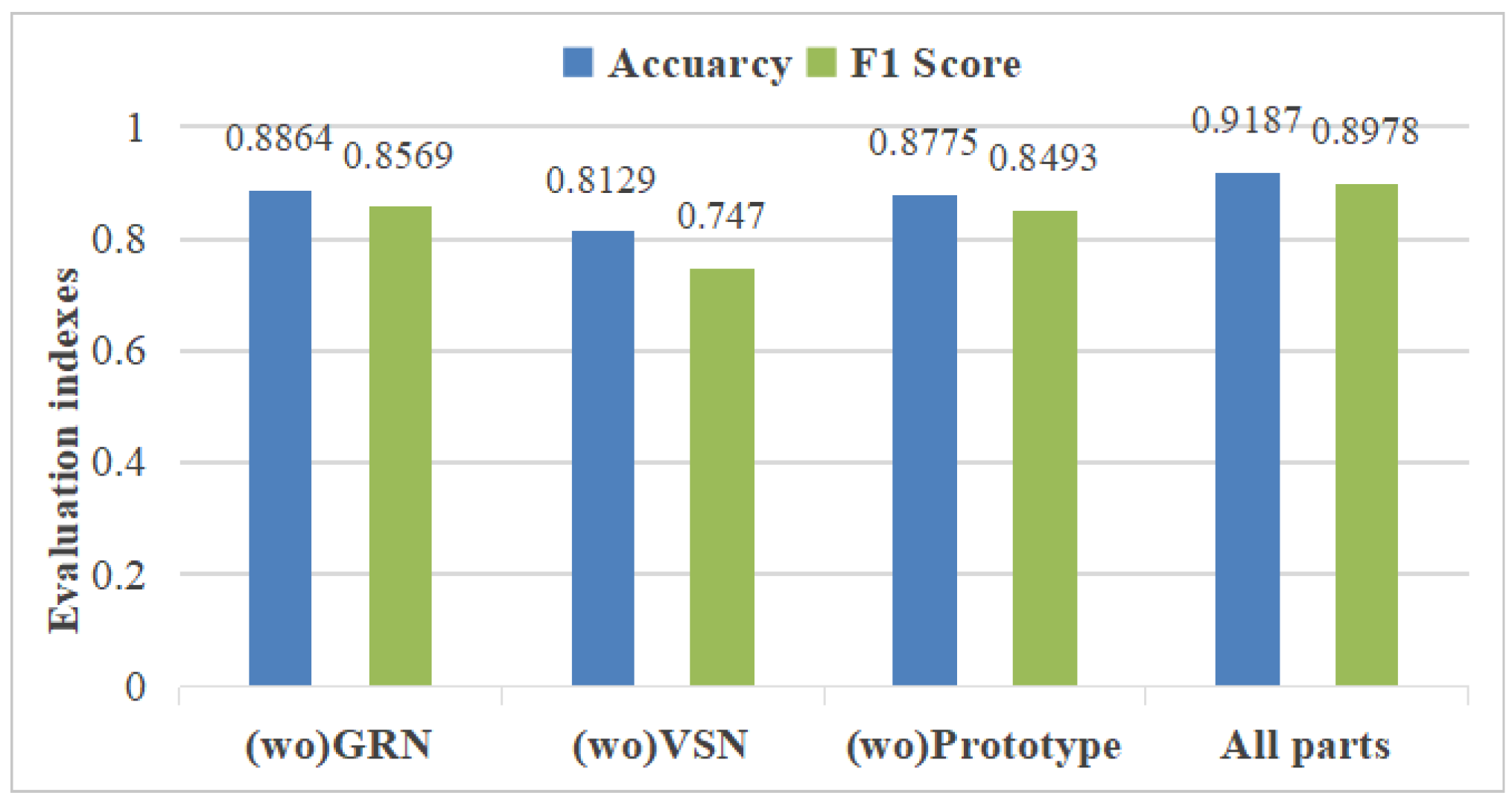

In order to prove the effectiveness of each part of the proposed model for the whole network, ablation experiments are required, the results of which are shown in

Figure 7. The GRN and VSN modules are directly removed, and the front and back inputs and outputs are directly connected. A fully connected layer replaces the Prototype module. The results show that GRN can better enhance the nonlinear ability of the model to learn the features of disc cutter wear better; VSN can very effectively improve the detection effect of the model while selecting the variables through different weights and improve the interpretability of the disc wear anomalies to a certain extent by obtaining the selected weights. The prototype network can improve the model’s ability to detect disc cutter wear to a certain extent by using the attention mechanism to extract key features and the normal state as class prototype vectors and calculating the distance between the current state and the prototype vectors of shield for detection.

4. Discussion

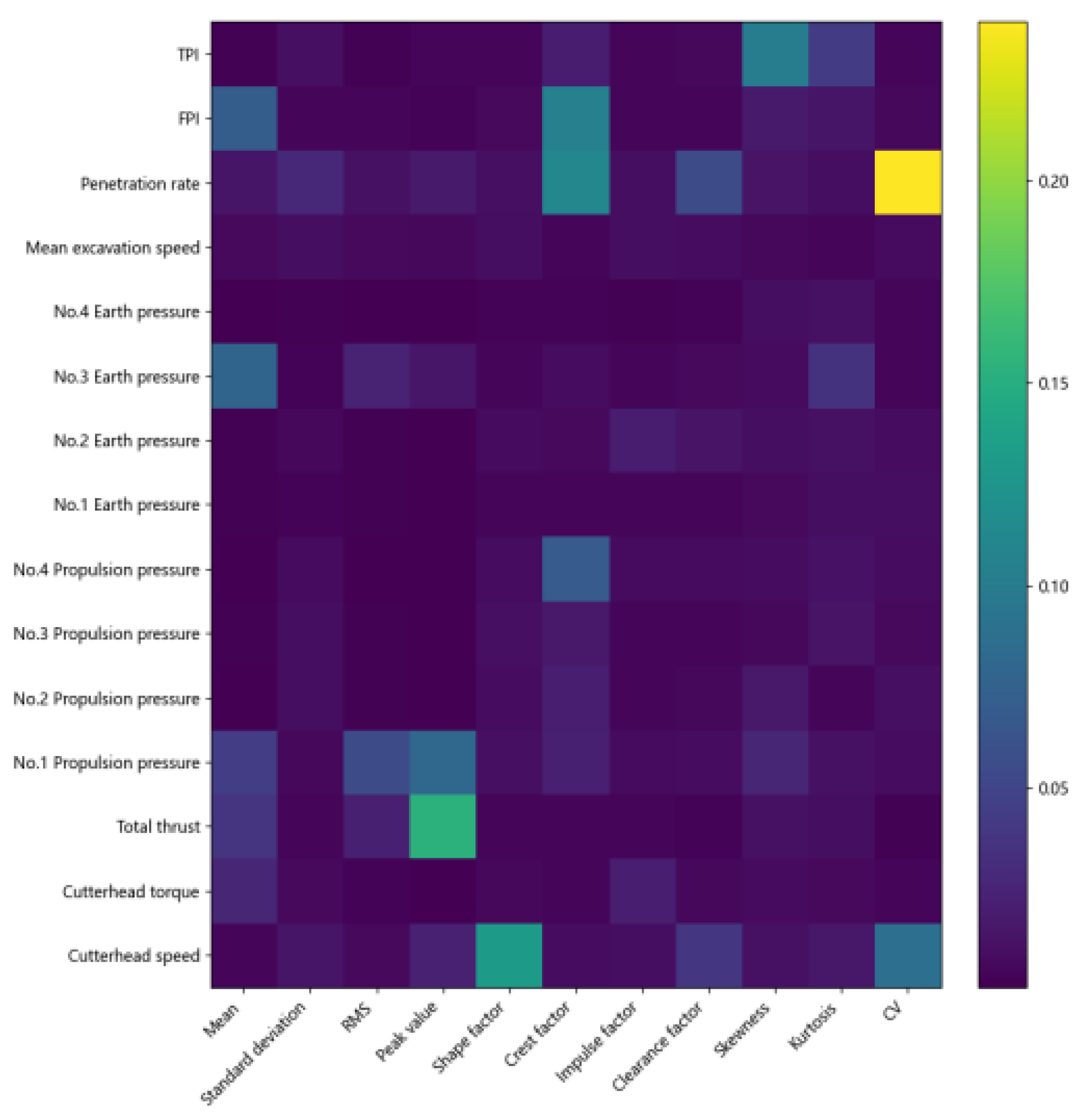

To more accurately assess which shield parameters are more correlated with the overall level of disc cutter wear, we trained all features and visualized the selection weights

in the variable selection module VSN, and the results are shown in

Figure 8. In this figure, the horizontal axis represents the selected features. In contrast, the vertical axis represents the different sensor data captured by the shield, and the shade of the color is used to indicate the magnitude of the weights. The weights show that the variable selection network gives relatively large weights to the four parameters of TPI, FPI, penetration, and disc cutter speed in composite strata. It indicates that when the overall disc cutter wear reaches a certain level that affects the cutting efficiency and the cutter needs to be replaced, four parameters of penetration, FPI, TPI, and cutterhead speed change significantly. The weights of the other parameters are relatively small, particularly the cutterhead torque, which means the composite indicator parameters are more suitable for describing the shield state characteristics under different digging conditions than the single sensor parameters, reflecting the fact that a comprehensive judgment of the parameters is needed to judge the disc cutter wear, which is also the reason why evaluation indicators such as TPI, FPI, penetration, are proposed to be used for detecting the disc cutter wear in other works. In addition, it was also found that the excavation speed in the Ma Wan Cross-sea Tunnel did not significantly impact the overall disc cutter wear. Actually, the data showed that the thrust in the sub-zones increased significantly when the disc cutter wear occurred. It is due to increasing the thrust on site to ensure excavation speed despite the disc cutter wear during construction. This finding is consistent with the summaries of experience and feedback reports from the engineers and technicians accumulated during the actual project.

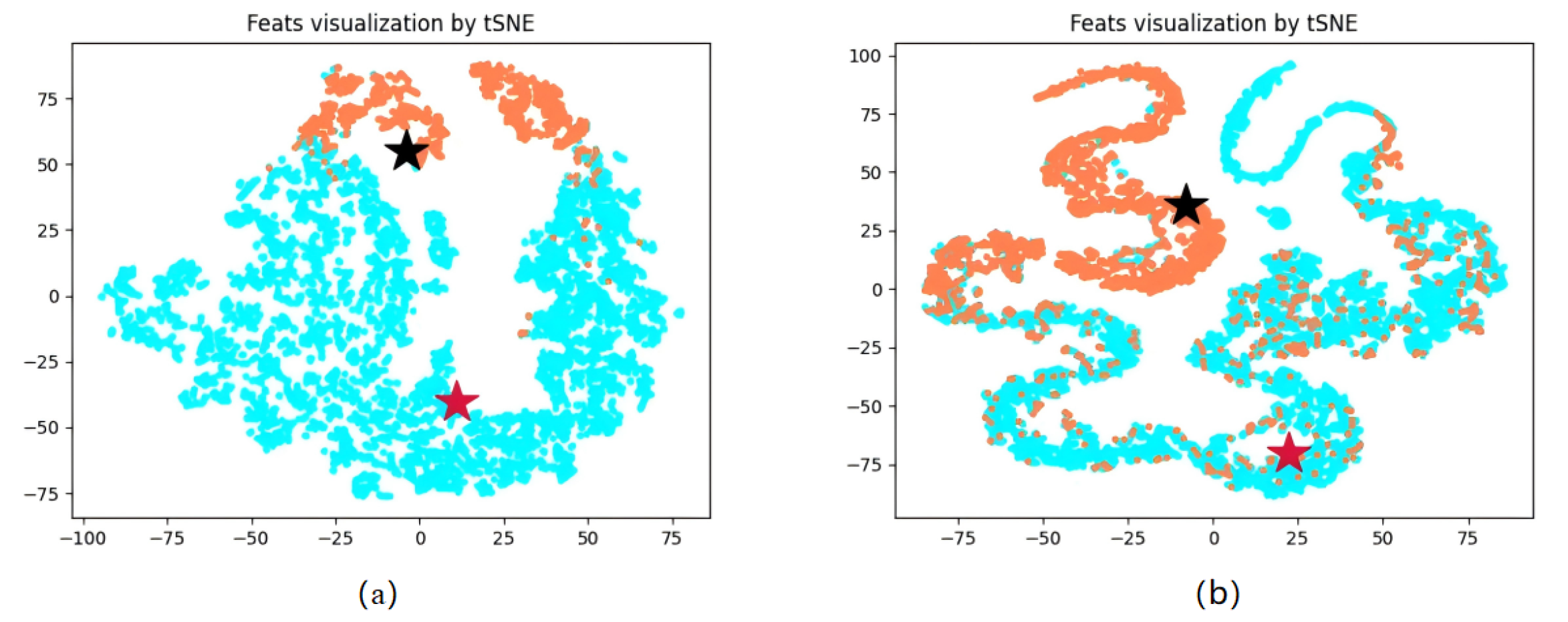

In order to better visualize the relationship between individual samples in the model and the class prototype matrix, t-SNE was employed to project the class prototypes and the samples from both the training and testing phases.

Figure 9. shows the results. In figure, the orange points indicate the data of the disc cutter wear state, the blue points indicate the data of the normal state, and the black and red stars represent the centers of the class prototypes of the disc cutter wear state and the normal state. It can be seen that the distribution of the data features of the disc cutter wear state and the normal state has apparent differentiation. However, due to the complexity of the shield tunneling process, human factors, mechanical factors, and stratigraphic factors in the shield tunneling process, the distribution of the data will be shifted with the tunneling process. A small amount of disc cutter wear data has features similar to those of the normal state, which makes some points hard to accurately categorize.

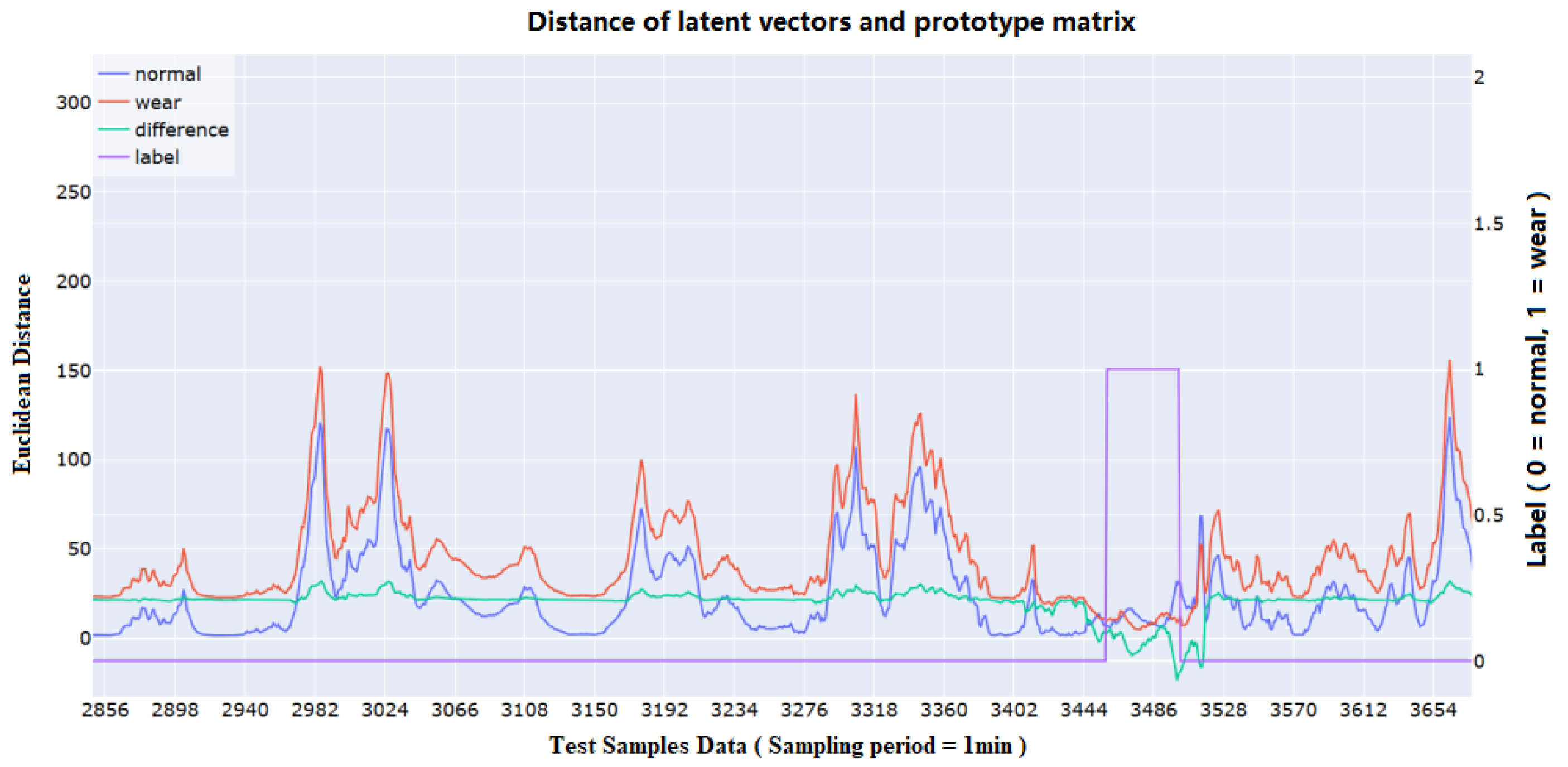

Calculated the difference between the latent vectors and the different classes of vectors in the prototype matrix by the L2-norm to assess the changes in distances between the data features and the vectors of different classes during the advancement.

Figure 10. shows the detection results of one of the cases in which disc cutter wear occurs. It can be found that when the shield’s working state is changed except for disc cutter wear, the distance between the shield and the different classes of prototypes will change simultaneously. In contrast, the distance relationship will change when the disc cutter wear occurs. By calculating the difference between the wear distance and normal distance, it can be more clearly seen that under normal propulsion, the difference is roughly stable even under different working conditions. However, when the cutting capacity of the disc cutter decreases, it means that the disc cutter needs to be changed. This difference will drop significantly and eventually reach a negative value, and eventually trigger an alarm. This can prove the model’s effectiveness in detecting disc cutter wear anomalies. At the same time, it provides a new idea for predicting disc cutter wear.

Figure 1.

The overall framework of the disc cutter wear detection.

Figure 1.

The overall framework of the disc cutter wear detection.

Figure 2.

The architecture of data preprocessing.

Figure 2.

The architecture of data preprocessing.

Figure 3.

The architecture of MVSAPNet.

Figure 3.

The architecture of MVSAPNet.

Figure 4.

Outlier removal results for shield disc cutter speed. (a) The blue curve represents the data before outlier removal, the red curve represents the data after outlier removal. (b) the yellow curve represents the reconstruction bias of the LSTM-ED model, and the blue curve represents the use of the selected threshold value.

Figure 4.

Outlier removal results for shield disc cutter speed. (a) The blue curve represents the data before outlier removal, the red curve represents the data after outlier removal. (b) the yellow curve represents the reconstruction bias of the LSTM-ED model, and the blue curve represents the use of the selected threshold value.

Figure 5.

Denoising results of cutterhead speed using VMD-WT.

Figure 5.

Denoising results of cutterhead speed using VMD-WT.

Figure 6.

Effect of different pre-processing steps results with proposed model.

Figure 6.

Effect of different pre-processing steps results with proposed model.

Figure 7.

Impact of removing part of the network structure alone on detection performance.

Figure 7.

Impact of removing part of the network structure alone on detection performance.

Figure 8.

Visualization of mean weights of in VSN networks.

Figure 8.

Visualization of mean weights of in VSN networks.

Figure 9.

Visualization results of model sample features and class prototype feature using the t-SNE method, red and black stars for normal and wear state class prototype features, blue dots and orange dots for normal and wear state sample features. (a) Training set. (b) Test set.

Figure 9.

Visualization results of model sample features and class prototype feature using the t-SNE method, red and black stars for normal and wear state class prototype features, blue dots and orange dots for normal and wear state sample features. (a) Training set. (b) Test set.

Figure 10.

Visualization results of the distances between the sample vectors and the class prototype matrix on the test set, with the blue line being the distance between the samples and the normal state, the red line being the distance between the samples and the worn state, the green line being the worn distance and the normal distance, and the purple color being the class labels, with 0 = normal state and 1 = worn state.

Figure 10.

Visualization results of the distances between the sample vectors and the class prototype matrix on the test set, with the blue line being the distance between the samples and the normal state, the red line being the distance between the samples and the worn state, the green line being the worn distance and the normal distance, and the purple color being the class labels, with 0 = normal state and 1 = worn state.

Table 1.

Features selected for feature engineering.

Table 1.

Features selected for feature engineering.

| Index |

Feature |

Equation |

Index |

Feature |

Equation |

| 1 |

Mean |

|

7 |

Impulse factor |

|

| 2 |

Standard

deviation |

|

8 |

Clearance factor |

|

| 3 |

Root

mean square |

|

9 |

Skewness |

|

| 4 |

Peak value |

|

10 |

Kurtosis |

|

| 5 |

Shape factor |

|

11 |

CV |

|

| 6 |

Crest factor |

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Details of 15 parameters selected.

Table 2.

Details of 15 parameters selected.

| Number |

Parameter |

| 1 |

Cutterhead speed (r/min) |

| 2 |

Cutterhead torque (kNm) |

| 3 |

Total thrust (kN) |

| 4-7 |

Propulsion pressure of cylinders groups No. 1-No. 4 (MPa) |

| 8-11 |

Earth pressure of excavation soil bin No. 1-No. 4 (bar) |

| 12 |

Mean excavation speed (mm/min) |

| 13 |

Penetration (mm/r) |

| 14 |

FPI |

| 15 |

TPI |

Table 3.

Partial results of trend and monotonicity scores for features.

Table 3.

Partial results of trend and monotonicity scores for features.

| Features |

Monotonicity |

Trend |

Score |

| Standard deviation of mean excavation speed |

0.08 |

1 |

1.08 |

| Kurtosis of cutterhead torque |

0.1962 |

1.49e-07 |

0.1962 |

| Skewness of cutterhead torque |

0.1962 |

0.0007 |

0.1781 |

| Standard deviation of Earth pressure No. 1. |

0.0171 |

0.1610 |

0.1781 |

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

| Mean of Penetration |

0.0952 |

0.0358 |

0.1310 |

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different classification networks on test set of disc cutter wear.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different classification networks on test set of disc cutter wear.

| Model |

Accuarcy |

F1-Score |

| LSTM-FCN |

0.8151 |

0.7917 |

| ALSTM-FCN |

0.8427 |

0.8230 |

| BiLSTM |

0.8422 |

0.8172 |

| ResNet |

0.8385 |

0.8104 |

| InceptionTime |

0.8642 |

0.8412 |

| TapNet |

0.8594 |

0.8350 |

| GTN |

0.8848 |

0.8556 |

| TARNet |

0.9023 |

0.8785 |

| MVSAPNet |

0.9187 |

0.8978 |