1. Introduction

Land use and land cover (LULC) maps are one of the most important topics in remote sensing. These maps provide an essential framework for understanding relationships between landscapes, ecosystems and human activities [

1,

2]. Thus, they offer crucial insights for the development of effective land planning strategies and policies. Modern mapping techniques and tools ensure an expanding range of applications, supporting decision-makers in addressing critical challenges in environmental and urban management [

2,

3,

4]. To date, exploiting LULC maps to characterize land structures represents the basis of most ecological analyses.

As the world faces growing environmental challenges, trees and forest ecosystems play a central role in environmental governance, and their mapping has become imperative to planning, managing, conserving and enhancing this resource. In this context, tree and forest cover maps serve as the operational basis for initiatives mainly aimed at assessing forest disturbances [

5,

6], understanding forest functioning [

7], and maximizing the ecosystem services (ES) provided by trees [

8]. For this purpose, cartographic representations of forested landscapes are designed to inventory and analyse several quantitative (e.g., structure and composition; [

9]) or qualitative (e.g., species, types and function; [

10,

11,

12]) information related to tree cover.

Tree and forest cover maps are developed from different interpretation systems of satellite, airplane or drone images [

2,

3,

10,

13,

14]. Advances in remote sensing technologies and analytical methods have enabled recent forest maps to achieve high levels of accuracy and detail [

15]. Depending on their target, forest mapping can be achieved on different scales [

6], from local stand-level maps to broad-scale regional or global assessments. Regularly collecting, processing and disseminating of remote sensing information, especially from satellites sources, ensure that the most current and accurate data are openly available and accessible for several purposes, above all environmental ones. This also provides the opportunity to compare time series’ information, allowing continuous monitoring of trees and forest resources in relation to their major threats [

5,

16,

17,

18]. These presssures typically stem from land use and land cover (LULC) change processes. Examples include forest expansion due to land abandonment [

19], the loss of trees and forest patches driven by intensive agricultural practices [

20], and forest landscape fragmentation caused by urban expansion and sprawl [

21].

So that trees continue to provide ES that are essential to human well-being, e.g., carbon sequestration, air pollution removal, hydrogeological risk mitigation and biodiversity conservation [

22], reliable monitoring tools are increasingly needed [

23]. Although present remote sensing sources and cartographic techniques are very powerful, there can be limitations of tree and forest cover maps considering trade-offs between their resolution and scales. Therefore, achieving high-resolution and up-to-date maps is not a straightforward task. Moreover, the complexity of forest systems requires a high amount of information, often hindering the development of comprehensive tools and limiting their support to specific targets of sustainable forest planning and management [

15]. All the above can be translated into the broad effort of producing cartographic tools that have maximum usability, accuracy and convenience in terms of time and costs [

6].

Present communication introduces a novel tree and forest cover mapping of the Latium region, central Italy. Mapping was accomplished adopting several cartographic techniques within a GIS environment, taking advantage of the integration of high-resolution and freely accessible land cover layers alongside existing outdated regional datasets, thus updating the relevant geometric and typological information. A final map with a 10-meters spatial resolution gathers spatially explicit data regarding coverage, function, spatial configuration and typological classification of trees and forests throughout the entire regional surface. Basing on open access and regularly updated satellite data, the Latium tree cover map should also represent an initial effort in order to develop a large-scale monitoring appliance for forest resources, which could have significant implications for both scientific research and policymaking. Map is indeed included among the preliminary tasks for the achievement of the regional forest program of Latium and the Metropolitan Forest Plan of Rome, which is currently underway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geometrical, Functional and Spatial Classification of Regional Forests

Tree and forest cover map regards the entire surface of the Latium region, Central Italy (41.5303500 N 12.2805800 E). Study area approximately covers 17,200 km

2 [

24]. The Latium region presents different climatic regimes in relation to a high geographical and morphological heterogeneity. Inner mountain areas are characterized by a temperate climate with large amounts of precipitation. While, a typically Mediterranean climate along the coasts is found. The geographical and geomorphological heterogeneity of the Latium Region results in an important diversification of habitats, biomes and species [

25]. Despite the presence of 110 protected areas and 200 Natura2000 network sites, Latium environment is constantly under pressure, mostly due to the presence of the Metropolitan City of Rome, which, with 5,350 km

2 in surface and 4,2 million inhabitants, covers one third of the region and represents the most populated metropolitan area in Italy [

24]. Although main anthropic pressures are concentrated in this province, secondary harmful effects are extended to the whole regional territory (e.g., the widespread road, railway, airport and naval infrastructure in support of the heavy commuting, tourism and industrial development; [

26]). Furthermore, the great built-up density closely connected to the employment potential of the metropolitan area causes a high and sprawl land consumption in urban and peri-urban areas concurrently with depopulation of inner mountain areas and abandonment of traditional land management practices [

26].

The regional tree and forest cover mask was created by integrating two datasets: the updated Corine Land Cover + Backbone (CLC+ BB; EEA, [

27]) from 2018 and the Latium Land Use (LU) Map from 2000 [

25]. CLC+ BB 2018 is a wall-to-wall raster product derived from multi-temporal Sentinel-2 time series data. It features a pixel-based approach with a spatial resolution of 10 meters and includes 11 land cover classes. This layer is part of the broader Copernicus Land Monitoring Service, providing detailed mapping of land cover types across Europe. The use of this dataset for defining the regional forest mask is linked to key attributes of the CLC+ BB 2018. Firstly, this layer is updated on a three-year cycle and is released within a very short timeframe. This characteristic makes it particularly suitable for the application in monitoring land cover dynamics. Furthermore, the CLC+ BB 2018 combines the qualitative accuracy of high resolution with high reliability of land cover information. Specifically, a post-processing verification, based on the interpretation of over 42,000 sample points, revealed an overall accuracy of 92.8% (±0.3%) for the EU27 region [

27].

In a first step, only woody cover classes of CLC+ BB 2018 (i.e.,: needle leaved trees, broadleaved deciduous trees and broadleaved evergreen trees, that are classes 2, 3 and 4 of the CLC+ BB 2018 layer, respectively) were considered as regional forest mask. In a second step, Latium LU Map 2000 was exploited in order to identified trees covering agricultural areas (i.e., class 2 of the LU map), then added to the overall forest mask and classified as “trees in agricultural areas”. In order to complete the regional tree cover mask, trees occurring within urban areas (i.e., class 1 of the Latium LU map) were added and classified as “trees in natural areas”. As for trees near wetlands and water bodies (i.e., classes 4 and 5 of the LU map, respectively), they were included as “trees in natural areas” (i.e., class 3 of the LU map). Overall forest mask was therefore classified distinguishing Forests and Trees Outside Forest (TOF) patches.

The concept of TOF was discussed for the first time in 1996 during the FAO Expert Consultation on Global Forest Resources Assessment [

28], recognizing their environmental and social values. As from FAO definition, they are trees or groups of trees even though they do not reach the minimum thresholds of “Forest” and “Other wooded lands” classes for extension, width, cover density and maturity height. In order to discriminate Forest and TOF of Latium region, we however adopted the TOF definition proposed by the Italian National Forest Inventory [

29], identifying in TOF class all tree formations of forest mask that concurrently not satisfied the three criteria of surface area (i.e., less than 2,000 square meters), cover density (i.e., less than 20%) and width (i.e., less than 20 meters wide) of forest definition. For this end, the Copernicus Tree Cover Density (TCD) High Resolution Layer 2018 [

27] was utilized as ancillary data. It was employed to assign cover density values to the surfaces of the forest mask.

2.2. Typological Classification and Accuracy Assessment

The typological classification scheme of forests proposed for the Latium Region follows, coherently with similar studies conducted on the national territory (e.g., [

30,

31]), hierarchical criteria. Accordingly, forest types represent the fundamental units. Forest categories and types are forest characterized by homogeneity from ecological and functional perspectives. Therefore, these forest units can be considered as key units of forest planning and management. For the classification of forest categories and types of the Latium region, the first step required the extraction by forest mask of the functional classes “trees in urban areas” and “trees in agricultural areas”. Although characterized by an artificial origin, tree formations of the Latium agricultural landscape are generally cultivated and/or managed with a reduced impact on the environment and are able to provide, together with urban forests, important ES. A typological label (here intended for both forest category and forest types) with the analogous functional label were allocated to these two classes. Within the “trees in agricultural areas” category, two distinct sub-categories were identified in a second stage, i.e., agricultural trees, classified as “trees in agricultural areas,” and olive orchards, classified as “olive groves.”. For the typological classification of Latium tree and forest cover, ancillary information about forest categories and types was obtained by the Latium Forest Types map at 2000 year and the resultant Natural and Semi-Natural Environments and Forest Types Map of the Latium region at 2010 year [

32]. This layer was derived from a detailed refinement of the pre-existing Latium Land Use Map 2000, incorporating levels IV and V of the Corine Land Cover classification. Specifically, Natural and Semi-natural Environments and Forest Types Map based on segmentation and classification techniques of high-resolution satellite imagery and ADS40 false-color infrared digital orthophotos. Final product related to two maps geometrically and thematically consistent with each other, with forest typological classification scheme organized in 17 categories and 36 forest types according to the national classification scheme (more information about the adopted classification scheme and its harmonization with the European nomenclature are reported

Table S1 in supplementary material; [

32,

33]). Within areas classified as tree-covered by both CLC+BB 2018 and Latium forest types map, the forest category and type classes at the highest detail level was assigned. The rest of tree pixels from the CLC+ BB dataset classified as “trees in natural areas” (corresponding to classes 3, 4, and 5 of the Latium Land Use Map) were assigned to a forest type using a proximity algorithm. This algorithm determined the forest type based on the nearest polygon from the Latium forest types map.

At the end of the processing phases for the three layers of the forest map, the accuracy of the resulting classification schemes was assessed. Initially, a sample of check points was verified through on-screen interpretation, using the dataset scheme from the Italian Land Use Inventory (IUTI 2016 - 10% sampling points; [

34]). In detail, tree cover, function, spatial configuration, and typological class of 2,371 IUTI sample points were verified in 2018 using high-resolution color orthophotos by a photo interpreter. Additionally, 200 more challenging sample points were selected and verified in the field during a subsequent step. The comparison between verified and classified points was achieved through the implementation of precision (or error) matrix method for each layer [

35]. In this way, both the producer’s accuracy and the user’s accuracy of the individual classes were evaluated for each considered classification scheme. As a final valuation, the Overall Accuracy (OA) and the Kappa coefficient (

kappa) were calculated by confusion matrices (see

Table S2, S3, S4 and S5 in supplementary material).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Trees and Forest Cover of Latium Region

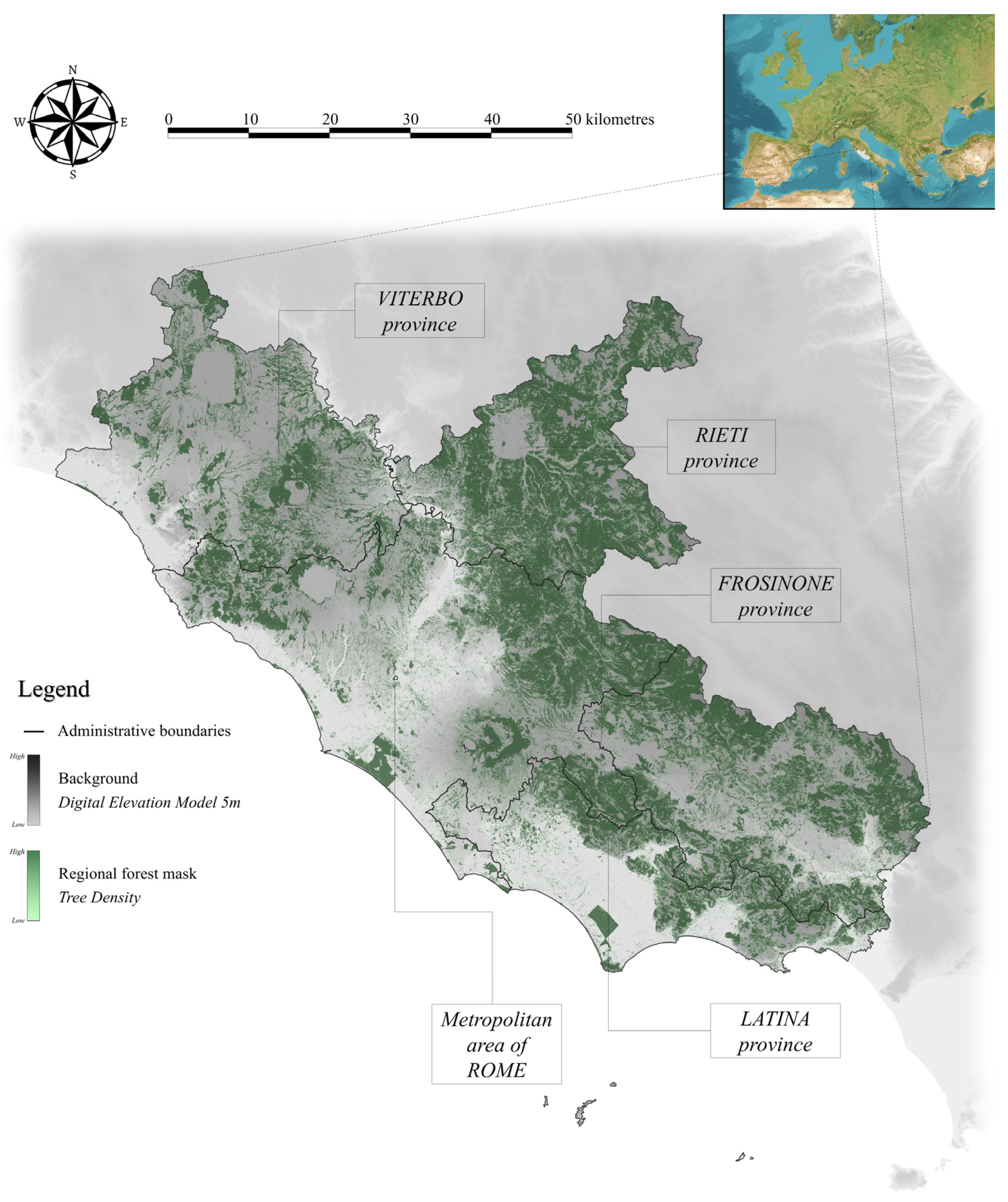

The tree and forest cover mapping of the Latium region displays a total coverage of 760,737 ha, corresponding to 44.2% of the total regional land area (

Figure 1). Excluding the area covered by agricultural trees, olive groves and TOF, forest and trees cover a total of 559,234 ha, equal to 32.6% of the regional land area (for more details and data, see

Tables S6 and S7 in Supplementary materials). This result is matched with the Italian National Forest Inventory [

29], which estimates for the Latium region a forest area and a forest cover index (i.e., forest area as a proportion of total land area) equal to 558,060 ha and 32.6%, respectively.

With respect to the regional topography [

24], 291,144 ha of regional mountain areas are covered by trees and forests (i.e., 38.3%). As for hilly and floodplain contexts, the tree and forest cover amounts for 211,623 ha and 257,970 ha, respectively. The Latium region does not have a large mountainous area, with 77.0% of its surface located below 600 m a. s. l. and more than half of the region (i.e., 53.6%) consisting of plains [

24]. In the latter domains, a strong anthropic pressure is concentrated, mainly connected to an intensive agriculture, a widespread road, railway and industrial infrastructure development and the never-ending urban sprawl of the Metropolitan City of Rome [

26]. Although trees and forests of the hilly and plain areas of Latium region represent only a quarter of the whole territory extension, they play a key role in preventing and restraining several environmental threats. Within the hill and plain areas, trees can represent the primary obstacle to land consumption, imperviousness and landscape homogenization [

36]. Moreover, in these areas, regulating ES are essential to mitigate the polluting effects of anthropic pressure on air, water and soil. In this regard, the forest map of the Latium region offers the great advantage of the spatial explicit tree density information. Canopy density is indeed the most adopted proxy for estimating several ecosystem services from forests [

21], being directly proportional to ES supply according to the assumption that the higher the canopy density, the higher the ecosystem functionality and services.

This is further confirmed by examining the distribution of regional tree and forest cover across the five provincial districts of Latium. Despite having 212,545 ha of tree and forest cover (39.7% of the whole metropolitan territory and 12,4% of the regional areas), the Metropolitan City of Rome is the largest province in terms of area but has one of the lowest forest and tree cover indices, which is notably lower than the regional average. However, the province with the lowest relative forest and tree cover in Latium region is Viterbo, with a relative index equal to 31.7%. With 12,934 ha of forest and tree coverage, the administrative district with the largest index is Rieti (65.5%), followed by the provinces of Frosinone, Rome and Latina (53.3%, 39.7% and 36.1%, respectively).

3.2. Trees and Forest Cover of Latium Region

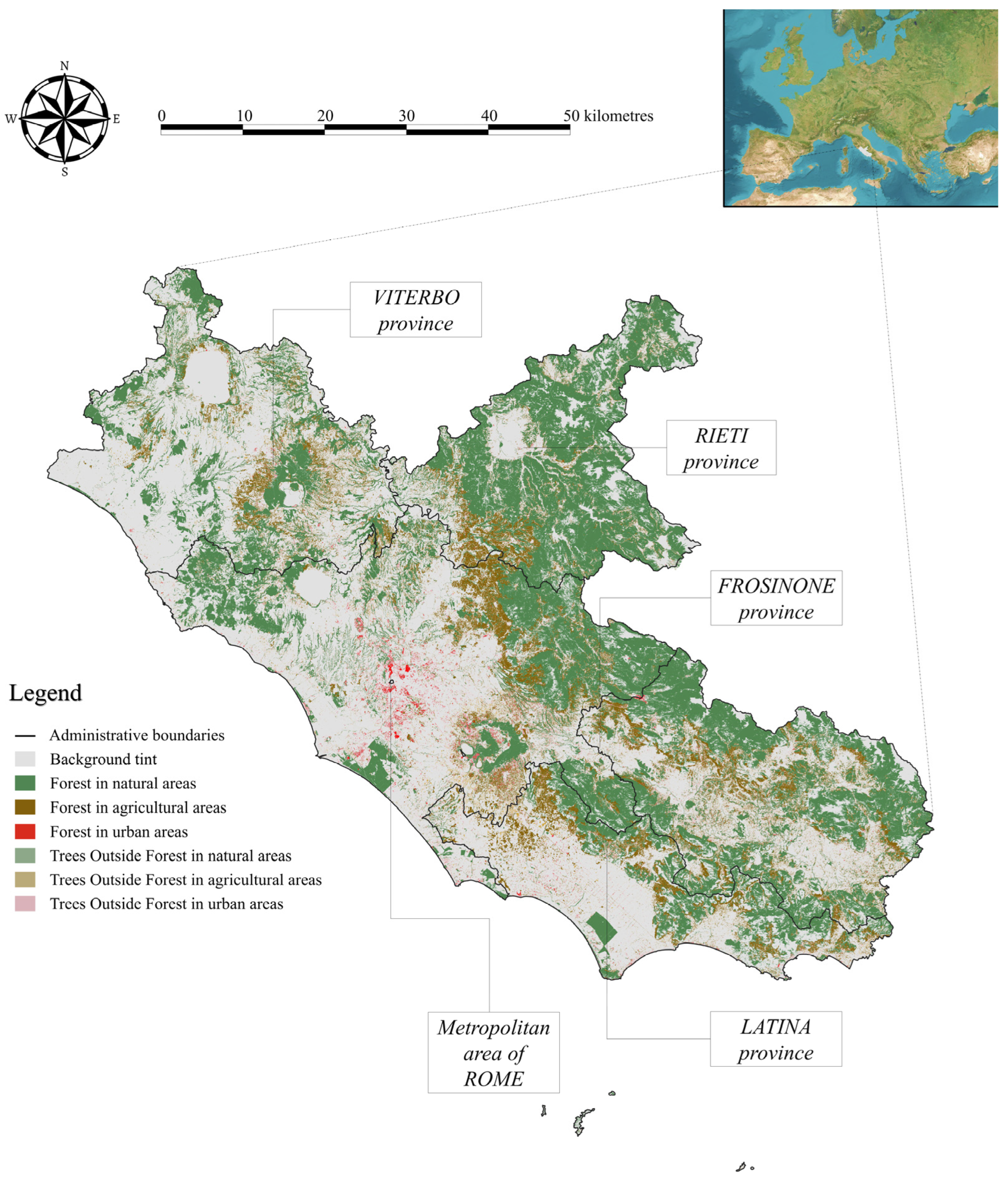

Tree and forest cover of Latium region is represented by 96.9% of forests and 3.1% of TOF (

Figure 2). Excluding agricultural and urban trees, olive groves and TOF patches, forests in natural areas represent 66.8% of all regional forest and tree cover, occupying a total surface of about 508,056 ha. They constitute the fundamental matrix of the Apennine mountain landscapes of Latium as well as of the pre-Apennine volcanic and carbonate reliefs. They have a high landscape and naturalistic value recognized by being the main constituent part of several regional protected areas and two national parks including the most important for Central Italy, that is the Abruzzo and Molise National Park [

37]. Besides the ecological role, these forests keep a central socio-economic interest linked to the regional beech, chestnut and oak wood supply chains, characterized by a long tradition of forest management for high quality timber, firewood and charcoal production [

38,

39,

40]. In these areas, where forest and tree cover maximize their benefits related to ecological and socio-economic functions, the availability of an updated and spatial explicit inventory is required to implement sustainable management of forest resources. Furthermore, regional forest and tree cover mapping provides for a strategic support to identify priority and/or vulnerable areas and define planning goals and actions at both stand and landscape scale.

Total forest and tree cover surface in agricultural areas corresponds to 173,647 ha (22.8% of the total) divided into 90.5% of forests and 9.5% of TOF patches. Trees and forests play a key role in Latium rural systems. While agricultural expansion and intensification can conflict with tree conservation due to competition for space, there is increasing recognition of the numerous benefits of incorporating trees and small patches of forest into farming landscapes [

41]. In face of current global changes, this integration is needed to more protecting (for instance, through the atmospheric carbon storage in tree biomass), resilient (e.g., by preventing erosion, runoff and hydrological risks linked to extreme events, which are expected to increase due to climate change) and sustainable (conserving biodiversity and habitats and improving landscape diversification and functions) agricultural systems. Tree cover mapping is therefore a key process for understanding interaction between forest ecosystems and human activities in landscape patterns dominated by agricultural matrix, where trees represent ecological corridors within very fragmented habitats for biodiversity conservation [

41]. Considering the high vulnerability of agricultural areas to hydrogeological risk following past deforestation activities and the adoption of mono-cropping systems that reduce the soil capacity to retain water, trees and forests in Latium agricultural backgrounds can also influence hydrogeological risk, positively contributing to soil protection and water cycle regulation [

42].

Covering approximately 15,206 ha, trees and forests in urban and peri-urban context (urban forest, UF) represent only 2.0% of the regional forest and tree cover. Only a quarter (i.e., 3,758 ha) of the Latium UF consists of TOF. Although small in size and overall extension, these tree patches often serve as the residual and precious natural components in areas with the highest levels of human activity. Understanding the distribution of trees and forests in urban and peri-urban areas of the Latium region is of great magnitude for developing nature-based solutions to tackle recent urban challenges, such as storm water management, heat island mitigation, and air quality improvement [

43]. Not surprisingly, here described forest and tree cover mapping is an integral part of the metropolitan master plan of Rome in progress. Strategies aim to new tree plantations in the Latium region are indeed based on the conservation of existing tree cover by the replacement of single diseased plants or the whole stand if necessary. Besides their mitigation role, UF face numerous diseases that threaten trees’ health, often exacerbated by human activities and specific stressors [

43]. A striking and current example is represented by the

Toumeyella parvicornis, which is causing a huge mortality of stone pine (

Pinus pinea L.) trees [

44]. Since the reporting of the first attacks of the parasite on pine trees in Latium region in 2020, infestations quickly spread, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas, where large historic gardens with high pine density are present. To date, there is no spatial explicit information about the regional parasite distribution yet. Thus, the spatial inventory of the present map can represent a priceless tool for monitoring the state and health of pine forests in these areas, where forest patches represent a key element for landscape, as well as the main constraint to urbanization and loss of permeable soil [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

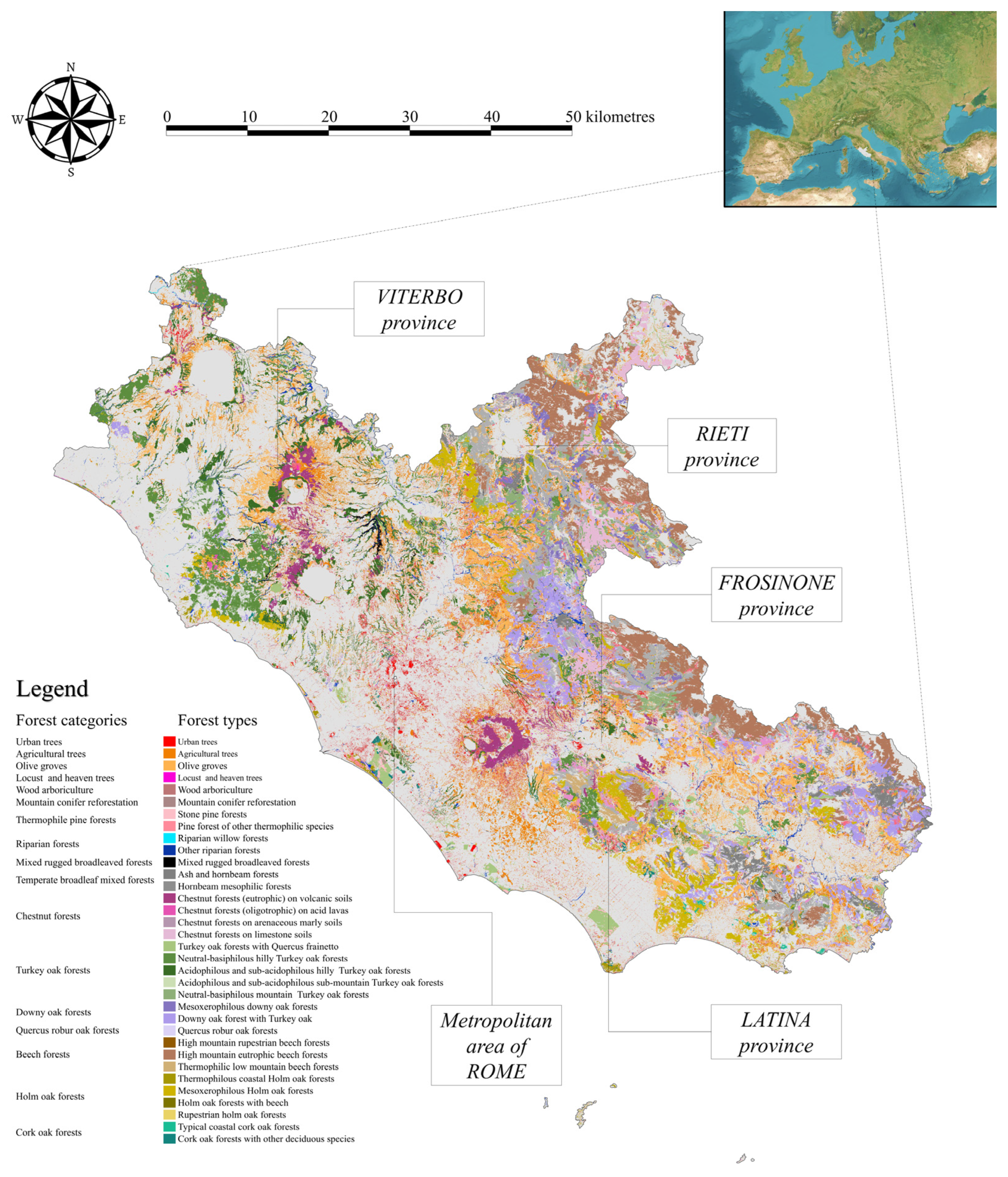

3.3. Forest Categories and Types

The distribution by forest categories, forest types and TOF in the Latium region is shown in

Table S7 in supplementary material. Most part (58.6%) of the Latium forest and tree cover concerns Turkey oak forests, Temperate broadleaf mixed forests, Beech forests, Downy oak forests and Holm oak forests. These categories represent the most widespread forest categories (

Figure 3), respectively covering 140,902 ha, 87,872 ha, 87,837 ha, 78,249 ha and 51,230 ha. Results are in line with estimates reported by the Italian National Forest Inventory [

29], which describes for these five forest categories an overall covered surface of 434,879 ha. In this comparison, the slightly higher estimate of Turkey oak, Beech and Holm oak forests’ coverage is chiefly due to the inclusion in the Latium tree cover map of forest formations that are not defined as forests by the national inventory. Findings thus provide strong validation of the accuracy of the tree cover map for the Latium region, establishing it as a reliable tool to support strategic forest management. Data availability may be a core part for the next Forest Regional Program, the instrument that will guide the forestry policy of Latium in the coming years, in implementation of the objectives of the European and National Forestry Strategy through the enhancement of multifunctional forest management.

The main findings also focus on the tree cover by the urban forest category, which makes up 4.4% of the total tree cover (equivalent to 33,790 ha of the regional area), as well as the agricultural categories. Agricultural trees cover 113,718.4 ha, and olive groves cover 77,835 ha. Their extension and spatial distribution are a very relevant subject considering their role in highly anthropized contexts in relation to biodiversity conservation of and ES provision, first of all the high value of biomass and carbon stock. Furthermore, 9.1% of the total area of these three categories consists of TOF, serving as the main element of ecological connectivity, diversification, and cultural value in both urban and rural landscapes [

45,

46].

4. Methodological Remarks and Accuracy

The main technique for representing the classification accuracy of remotely sensed data is through error matrix method [

35]. The mapping presented in this paper achieved overall accuracies of 91.6% for the tree canopy mask (tree versus non-tree land cover), 91.4% for spatial configuration (Forest or TOF), 88.8% for land use classification (trees in natural, agricultural, or urban areas), and 84.4% for forest type classes. As for the kappa coefficients of tree cover mask, configuration, use and types, they were 82.8%, 83.5%, 80.3% and 75.6%, respectively.

The confusion matrices for the estimation of the overall accuracy and kappa coefficients are reported in the supplementary materials’ section (for major details, see

Tables S2–S5 in Supplementary materials). The forest and tree cover map of the Latium region meets the accuracy requirements of major international standards, which set a minimum threshold for overall thematic accuracy at 85% to 90% [

28,

47,

48]. In this sense, the proposed methodology for forest and tree cover mapping at high spatial resolution and regional scale was found to be reliable for similar purposes. The reduced accuracy of the typological map is related to operational limits of the exploited ancillary data, deriving from obsolete segmentation software [

32]. Nevertheless, this study has successfully demonstrated the feasibility of producing reliable and cost-effective regional forest resource maps primarily using open-source data. Additionally, the regular release of such data enables rapid updates to these maps and supports their use for monitoring purposes.

5. Conclusions

The tree and forest cover of the Latium region is extensive, with 760,737 ha (44.2% of the regional total land area), 559,234 ha of which (32.6% of regional total land area) dedicated to forests, then excluding TOF, agricultural and urban trees and olive groves. The distribution of forests and tree cover varies by topography, with 38.3% of the mountain areas covered by forests and trees, and significant coverage in hilly and floodplain zones. This latter, despite comprising only a quarter of the total territory, play a critical role in mitigating anthropogenic pressures, particularly in the face of intense agriculture, urbanization, and infrastructure development. Forests, especially those in mountain areas, offer key ecological and socio-economic functions, and the availability of up-to-date forest mapping is vital for sustainable forest management and planning at a different scale. The study also distinguished between Forests and Trees Outside Forests (TOF), with Forest class accounting for 96.9% of the whole tree cover. Forests in natural areas make up most of the regional forest cover, while forests in agricultural landscapes contribute to landscape resilience and biodiversity conservation. Urban forests, though limited in size (2.0% of total tree cover), offer essential benefits such as heat island mitigation and air quality improvement. TOF in agricultural and urban areas also serve as vital elements for ecological connectivity and landscape diversification. Furthermore, the Latium region is home to a diverse range of forest categories, with Turkey oak, temperate broadleaf, beech, and downy oak forests being the most common. These forests support the local wood supply chains, one of the main driver of economy of inner areas. Findings underline the importance of regular forest mapping to monitor changes in forests and trees distribution, especially in urban-rural fringe of the Metropolitan area of Rome. The data generated from this study can provide the foundation for effective forest management strategies and sustainable development, enhancing the ecological, socio-economic, and environmental resilience of Latium landscapes. Basing on open access and regularly updated satellite data, our methodology has proven to be reliable for similar purposes, demonstrating cost, time and accuracy suitability for the implementation of forest resources’ monitoring tools at regional scale.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. All supplementary annexes are placed here as supplementary information to enhance the quality of our manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.d.C, F.V.M., M.M. and G.S.M.; methodology, M.d.C, F.V.M. and M.M.; software, M.d.C, F.V.M., M.M., D.T. and M.O.; validation, M.d.C.; formal analysis, M.d.C. and L.P.; investigation, M.d.C, F.V.M. and M.M.; data curation, M.d.C., M.M. and G.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.d.C.; writing—review and editing, M.d.C, F.V.M., M.M., L.P., M.M. and G.S.M.; visualization, M.d.C.; supervision, L.P., M.M. and G.S.M.; project administration, G.S.M.; funding acquisition, G.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to colleagues from the Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA) and University of Molise for their valuable feedback and assistance in the data process and the development of the mapping product.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nedd, R., Light, K., Owens, M., James, N., Johnson, E., Anandhi, A. A synthesis of land use/land cover studies: Definitions, classification systems, meta-studies, challenges and knowledge gaps on a global landscape. Land 2021, 10(9), 994. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Sun, Y., Cao, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, W., Cheng, X. A review of regional and Global Scale Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) mapping products generated from satellite remote sensing. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens 2023, 206, 311-334. [CrossRef]

- Hamud, A. M., Prince, H. M., Shafri, H. Z. Landuse/Landcover mapping and monitoring using Remote sensing and GIS with environmental integration. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 357. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S., Singh, R. A comprehensive review on land use/land cover (LULC) change modeling for urban development: current status and future prospects. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), 903. [CrossRef]

- Senf, C., Seidl, R. Mapping the forest disturbance regimes of Europe. Nat Sustain 2021, 4(1), 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F. E., White, J. C., Wulder, M. A., Næsset, E. Remote sensing in forestry: current challenges, considerations and directions. Forestry 2024, 97(1), 11-37. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F. D., Morsdorf, F., Schmid, B., Petchey, O. L., Hueni, A., Schimel, D. S., Schaepman, M. E. Mapping functional diversity from remotely sensed morphological and physiological forest traits. Nat commun 2017, 8(1), 1441. [CrossRef]

- Orsi, F., Ciolli, M., Primmer, E., Varumo, L., Geneletti, D. Mapping hotspots and bundles of forest ecosystem services across the European Union. Land use policy 2020, 99, 104840. [CrossRef]

- Ehbrecht, M., Seidel, D., Annighöfer, P., Kreft, H., Köhler, M., Zemp, D. C., Puettmann, K., Nilus, R., Babweteera, F., Willim, K., Stiers, M., Soto, D., Boehmer, H., J., Fisichelli, N., Burnett, N., Juday, G., Stephens, S., L., Ammer, C. Global patterns and climatic controls of forest structural complexity. Nat commun 2021, 12(1), 519. [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, V. J., Holden, C. E., Woodcock, C. E. Improved mapping of forest type using spectral-temporal Landsat features. Remote Sens Environ 2018, 210, 193-207. [CrossRef]

- Hościło, A., Lewandowska, A. Mapping forest type and tree species on a regional scale using multi-temporal Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens 2019, 11(8), 929. [CrossRef]

- Wieczynski, D. J., Boyle, B., Buzzard, V., Duran, S. M., Henderson, A. N., Hulshof, C. M., Kerkhoff, A., J., McCarthy, M., C., Michaletz, S., T., Swenson, N., G., Asner, G. P., Bentley, L., P., Enquist, B., J., Savage, V. M. Climate shapes and shifts functional biodiversity in forests worldwide. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116(2), 587-592. [CrossRef]

- Ganz, S., Adler, P., Kändler, G. Forest cover mapping based on a combination of aerial images and Sentinel-2 satellite data compared to National Forest Inventory data. Forests 2020, 11(12), 1322. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, N., Pádua, L., Marques, P., Silva, N., Peres, E., Sousa, J. J. Forestry remote sensing from unmanned aerial vehicles: A review focusing on the data, processing and potentialities. Remote Sens 2020, 12(6), 1046. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Zhang, X., Gao, Y., Chen, X., Shuai, X., Mi, J. Finer-resolution mapping of global land cover: Recent developments, consistency analysis, and prospects. Journal Remote Sens 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Xiang, J., Yan, E., Song, Y., Mo, D. Forest-CD: Forest change detection network based on VHR images. IEEE Geosci Remote Sens Lett 2022, 19, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Decuyper, M., Chávez, R. O., Lohbeck, M., Lastra, J. A., Tsendbazar, N., Hackländer, J., Herold., M. Continuous monitoring of forest change dynamics with satellite time series. Remote Sens Environ 2022, 269, 112829. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Li, J., Wu, W., & Liu, J. (2023). Global forest fragmentation change from 2000 to 2020. Nature commun 2023, 14(1), 3752. [CrossRef]

- Mantero, G., Morresi, D., Marzano, R., Motta, R., Mladenoff, D. J., Garbarino, M. The influence of land abandonment on forest disturbance regimes: a global review. Landsc Ecol 2020, 35(12), 2723-2744. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P. G., Slay, C. M., Harris, N. L., Tyukavina, A., Hansen, M. C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 2018, 361(6407), 1108-1111. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D. J., Greenfield, E. J. The increase of impervious cover and decrease of tree cover within urban areas globally (2012–2017). Urban For Urban Green 2020, 49, 126638. [CrossRef]

- Hua, F., Bruijnzeel, L. A., Meli, P., Martin, P. A., Zhang, J., Nakagawa, S., Miao, X., Wang, W., McEvoy, C., Luis, J., Arancibia, P., Brancalion, P., H., S., Smith, P., Edwards, D., P., Balmford, A. The biodiversity and ecosystem service contributions and trade-offs of forest restoration approaches. Science 2022, 376(6595), 839-844. [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G., Lovrić, M., Muys, B., Katila, P., Lundhede, T., Pecurul, M., Pettenella, D., Pipart, N., Plieninger, T., Prokofieva, I., Parra. C., Pülzl, H., Roitsch, D., Roux, J., L., Thorsen, B., J., Tyrväinen, L., Torralba, M., Vacik, H., Weiss, G., Wunder, S. Governing Europe’s forests for multiple ecosystem services: Opportunities, challenges, and policy options. ForPolicy Econ 2022, 145, 102849. [CrossRef]

- ISTAT - Italian National Institute of Statistics. Available online: https://www.istat.it/ (accessed on 10 Dec 2024).

- Regione Lazio – Geoportale. Available online: https://geoportale.regione.lazio.it/ (accessed on 17 Dec 2024).

- Sallustio, L., Quatrini, V., Geneletti, D., Corona, P., Marchetti, M. Assessing land take by urban development and its impact on carbon storage: Findings from two case studies in Italy. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2015, 54, 80-90. [CrossRef]

- EEA - European Environment Agency. Copernicus land monitoring service. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en (accessed on 11 Nov 2024).

- FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2000. Rome, Italy, 2001.

- INFC – Italia National Inventory of Forests and forest Carbon pools. Available online: https://www.inventarioforestale.org/en/ (accessed on 11 Nov 2024).

- Del Favero, R. I boschi delle regioni dell’Italia Centrale. Tipologia, Funzionamento, Selvicoltura. In CLEUP 2010, Padova, pp. 425.

- Barbati, A., Marchetti, M., Chirici, G., Corona, P. European Forest Types and Forest Europe SFM indicators: Tools for monitoring progress on forest biodiversity conservation. For Ecol Manage 2014, 321, 145-157. [CrossRef]

- Chirici, G., Fattori, C., Cutolo, N., Tufano, M., Corona, P., Barbati, A., Blasi, C., Copiz, R., Rossi, L., Biscontini, D., Ribera, A., Morgante, L., Marchetti, M. Map of the natural and semi-natural environments and forest types map for the Latium region (Italy). FOREST@ 2014, 11, 65-71.

- Chiavetta, U., Camarretta, N., Garfı, V., Ottaviano, M., Chirici, G., Vizzarri, M., Marchetti, M. Harmonized forest categories in central Italy. J Maps 2016, 12(sup1), 98-100. [CrossRef]

- Pagliarella, M. C., Sallustio, L., Capobianco, G., Conte, E., Corona, P., Fattorini, L., Marchetti, M. From one-to two-phase sampling to reduce costs of remote sensing-based estimation of land-cover and land-use proportions and their changes. Remote Sens Environ 2016, 184, 410-417. [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R. G. A review of assessing the accuracy of classifications of remotely sensed data. Remote Sens Environ 1991, 37(1), 35-46.

- di Cristofaro, M., Di Pirro, E., Ottaviano, M., Marchetti, M., Lasserre, B., Sallustio, L. Greener or Greyer? Exploring the Trends of Sealed and Permeable Spaces Availability in Italian Built-Up Areas during the Last Three Decades. Forests 2022, 13(12), 1983. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, W., Ferrara, C., Colonico, M., Gentile, C., Lombardo, E., Presutti Saba, E., Portoghesi, L. Assessing forest accessibility for the multifunctional management of protected areas in Central Italy. J Environ Plan Manag 2024, 67(1), 197-216. [CrossRef]

- Angelini A., Mattioli W., Merlini P., Corona P., Portoghesi L. Empirical modelling of chestnut coppice yield for Cimini e Vicani mountains (Central Italy). Ann. Silvic Res 2013, 37 (1), 7-12. [CrossRef]

- Marini, F., Portoghesi, L., Manetti, M. C., Salvati, L., Romagnoli, M. Gaps and perspectives for the improvement of the sweet chestnut forest-wood chain in Italy. Ann. Silvic Res 2021, 46, 112-127. [CrossRef]

- Scarascia Mugnozza, G., Romagnoli, M., Fragiacomo, M., Piazza, M., Lasserre, B., Brunetti, M., Zanuttini, R., Fioravanti, M., Marchetti, M., Todaro, L., Togni, M., Ferrante, T., Maesano, M., Nocetti, M., De Dato, G., B., Sciomenta, M., Villani, T. La filiera corta del legno: un’opportunità per la bio-economia forestale in Italia. FOREST@ 2021, 64-71. [CrossRef]

- Waldron, A., Garrity, D., Malhi, Y., Girardin, C., Miller, D. C., Seddon, N. Agroforestry can enhance food security while meeting other sustainable development goals. Trop Conserv Sci 2017, 10, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Biasi, R., Farina, R., Brunori, E. Family farming plays an essential role in preserving soil functionality: A study on active managed and abandoned traditional tree crop-based systems. Sustainability 2021, 13(7), 3967. [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, J. Direct and indirect loss of natural area from urban expansion. Nat Sustain 2019, 2(8), 755-763. [CrossRef]

- Somma, S., Notaro, L., Russo, E., Jesu, G., De Leva, G., Griffo, R., Garonna, A. P. Distribution of Toumeyella parvicornis (Cockerell) nine year after its introduction in Campania Region. In Proceedings of the XXVII Congresso Nazionale Italiano di Entomologia 2023, Palermo, Italy.

- di Cristofaro, M., Sallustio, L., Sitzia, T., Marchetti, M., Lasserre, B. Landscape preference for trees outside forests along an urban–rural–natural gradient. Forests 2020, 11(7), 728. [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, M., Marchetti, M. Census and Dynamics of Trees Outside Forests in Central Italy: Changes, Net Balance and Implications on the Landscape. Land 2023, 12(5), 1013. [CrossRef]

- ISO - International Organization for Standardization. ISO: 19157-1:2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/78900.html (accessed on 10 Dec 2024).

- IPCC - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Good Practice Guidance for Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (GPG-LULUCF) 2003. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/publication/good-practice-guidance-for-land-use-land-use-change-and-forestry/ (accessed on 17 Dec 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).