Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

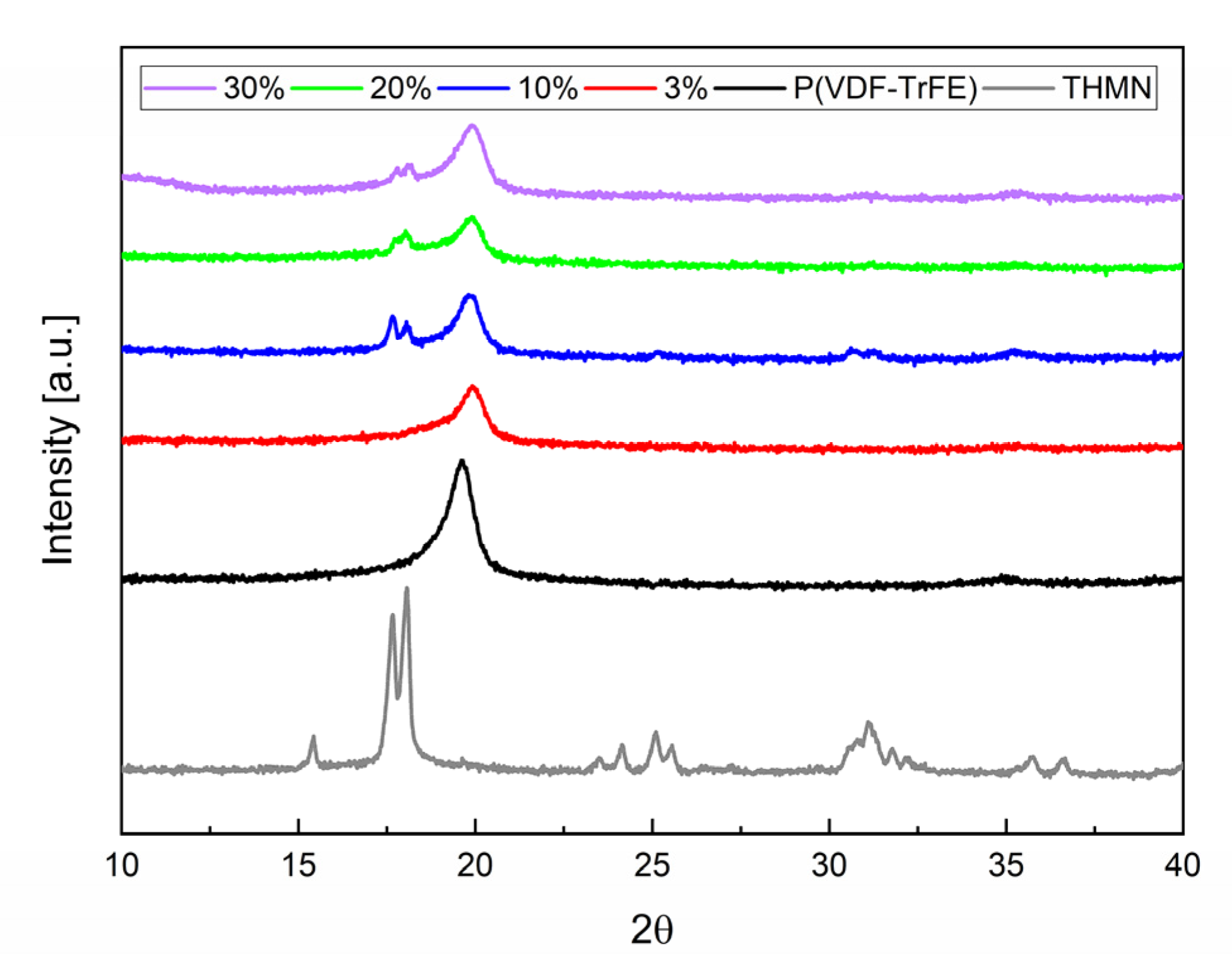

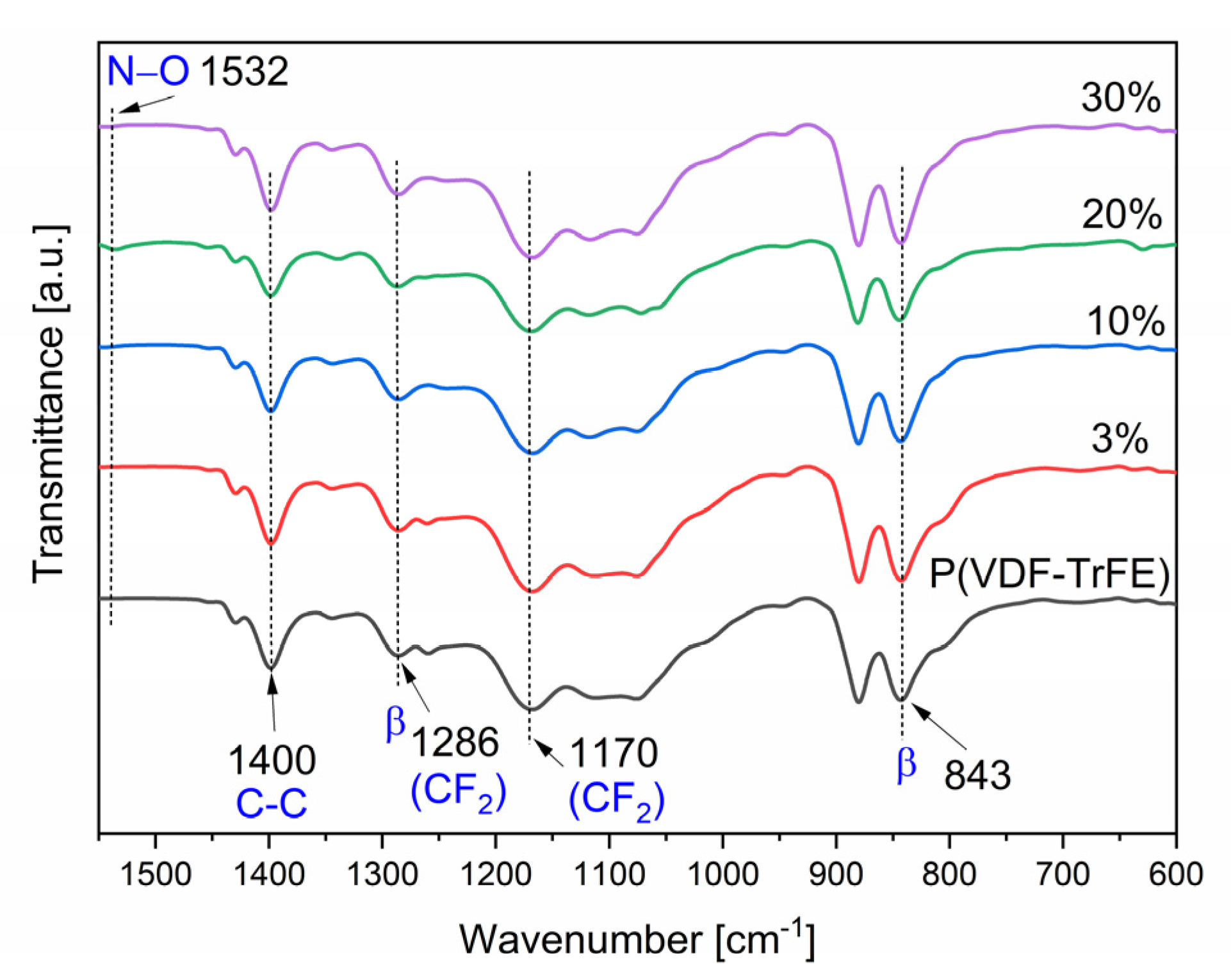

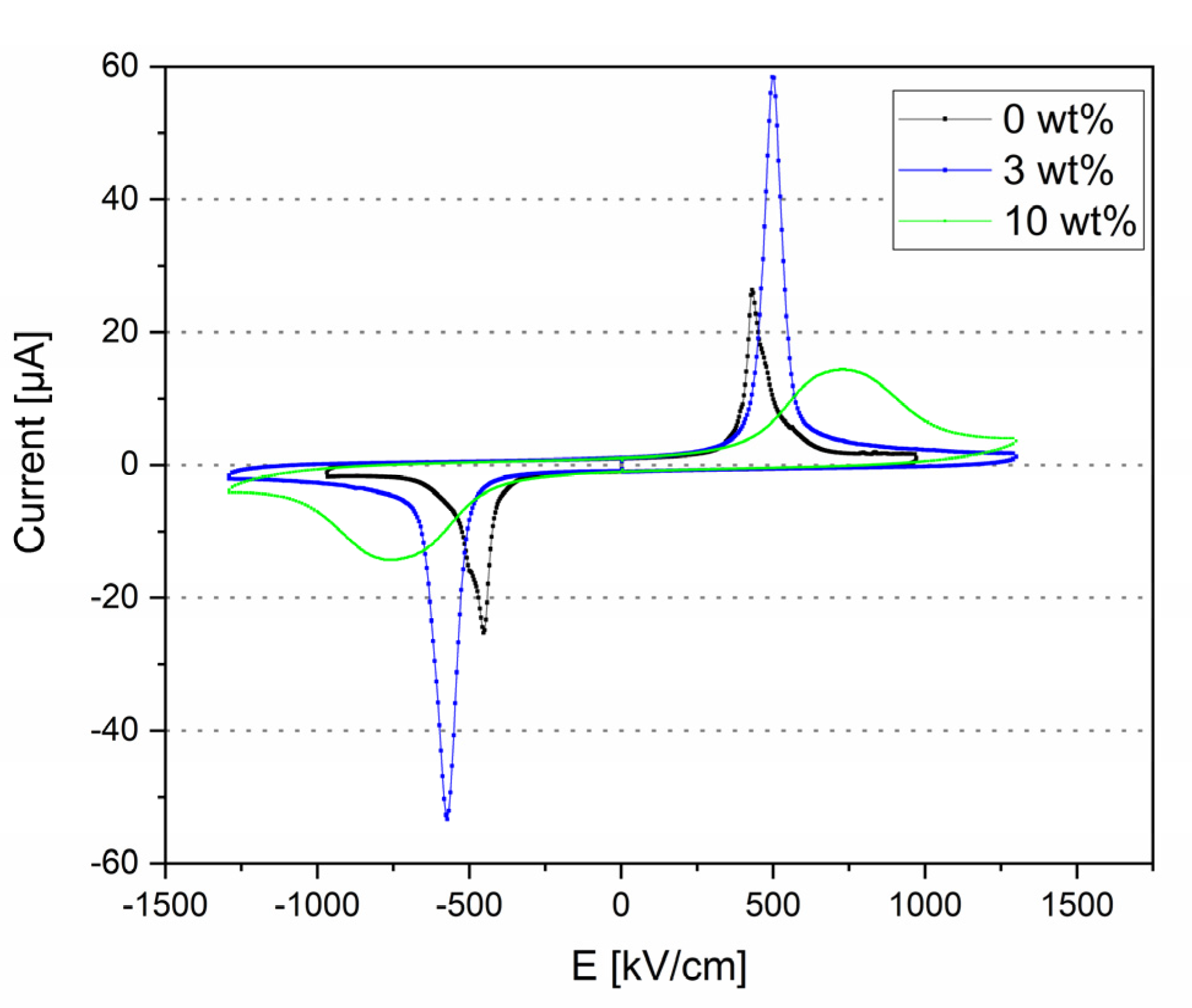

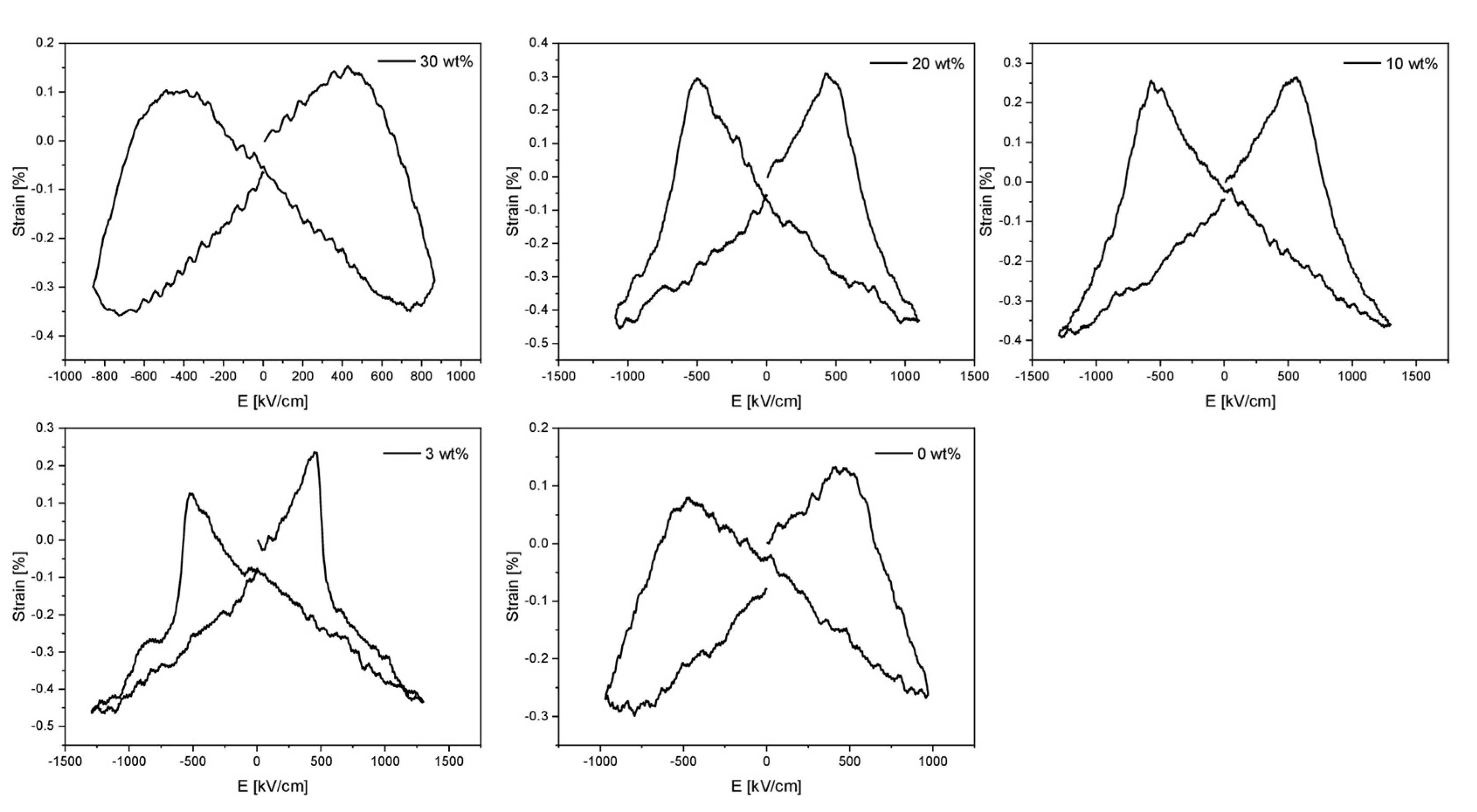

Polymer composites of P(VDF-TrFE) and Tri(hydroxymethyl) nitromethane as filler material with different concentrations have been prepared. Tri(hydroxymethyl) nitromethane is an organic ferroe-lectric material with low preparation cost, lightweight, and easy processing. Its properties enable it to be a potential candidate for use as filler material in polymers to improve their ferroelectric, dielec-tric, and piezoelectric properties. We investigated the effect of filler content on the ferroelectric and dielectric properties of the polymer. Our results show that Tri(hydroxymethyl) nitromethane retains its crystallinity after embedding it in the polymer matrix. It does not alter the crystalline ferroelectric β-phase of the polymer. All composites possess higher polarization compared to pure P(VDF-TrFE). Up to 11.4 µC/ cm2 remnant polarization and a dielectric constant of 14 at 1000 Hz have been ob-tained with the free-standing 10 wt% composite film.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

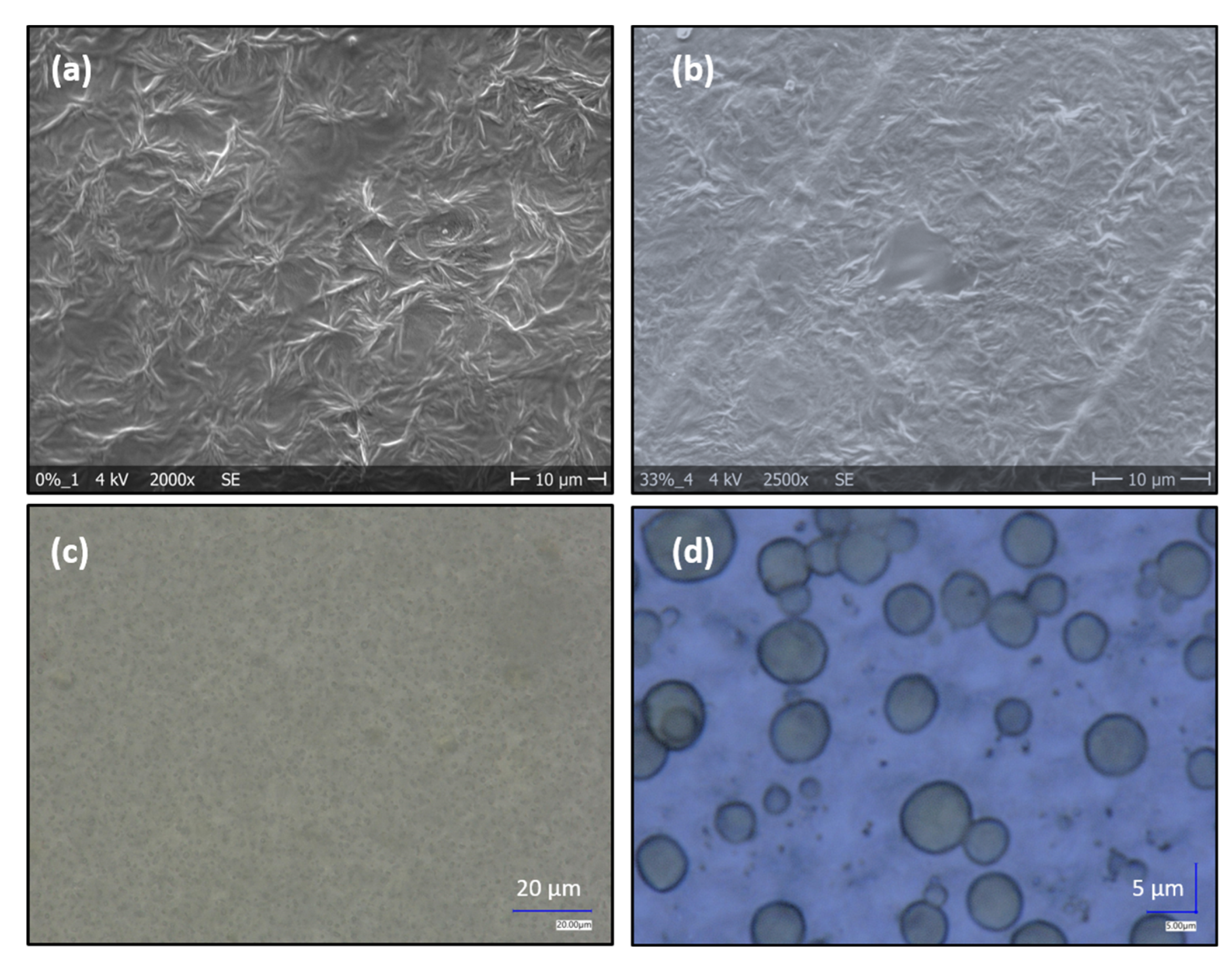

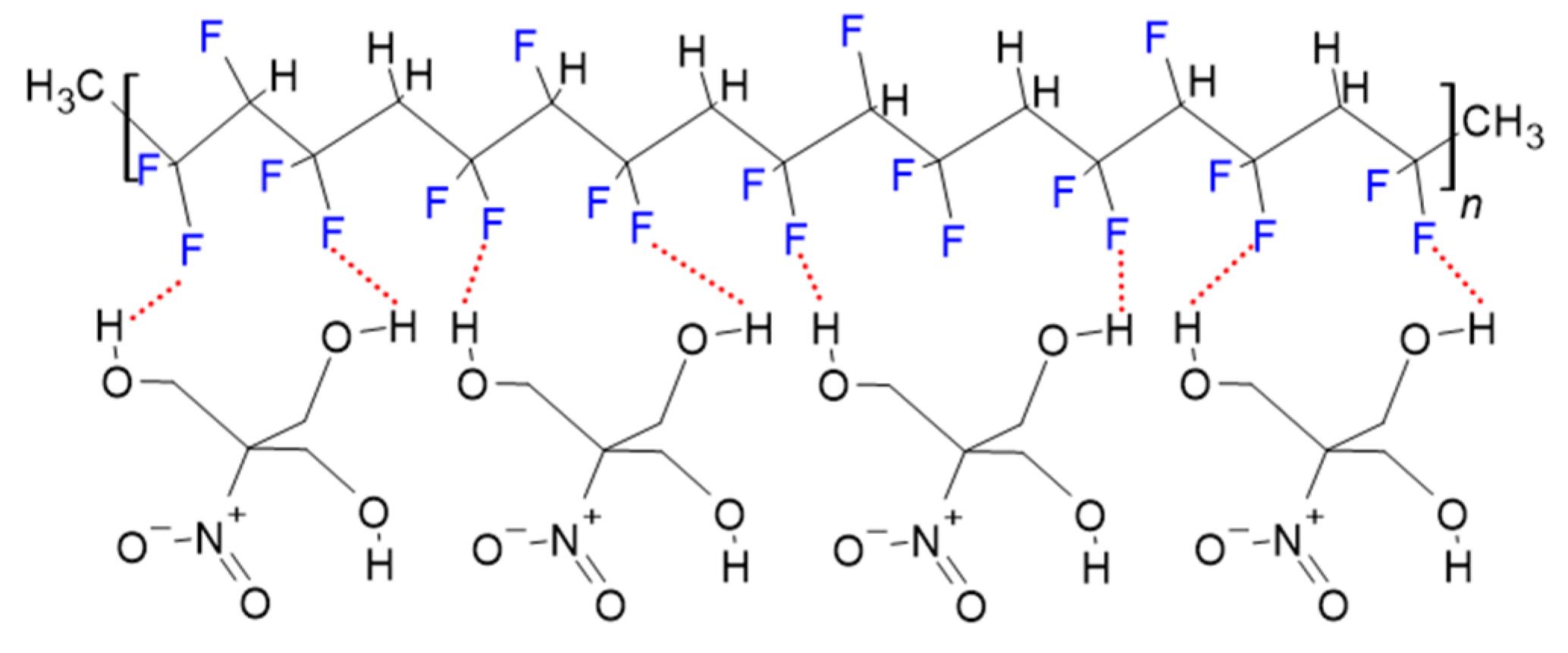

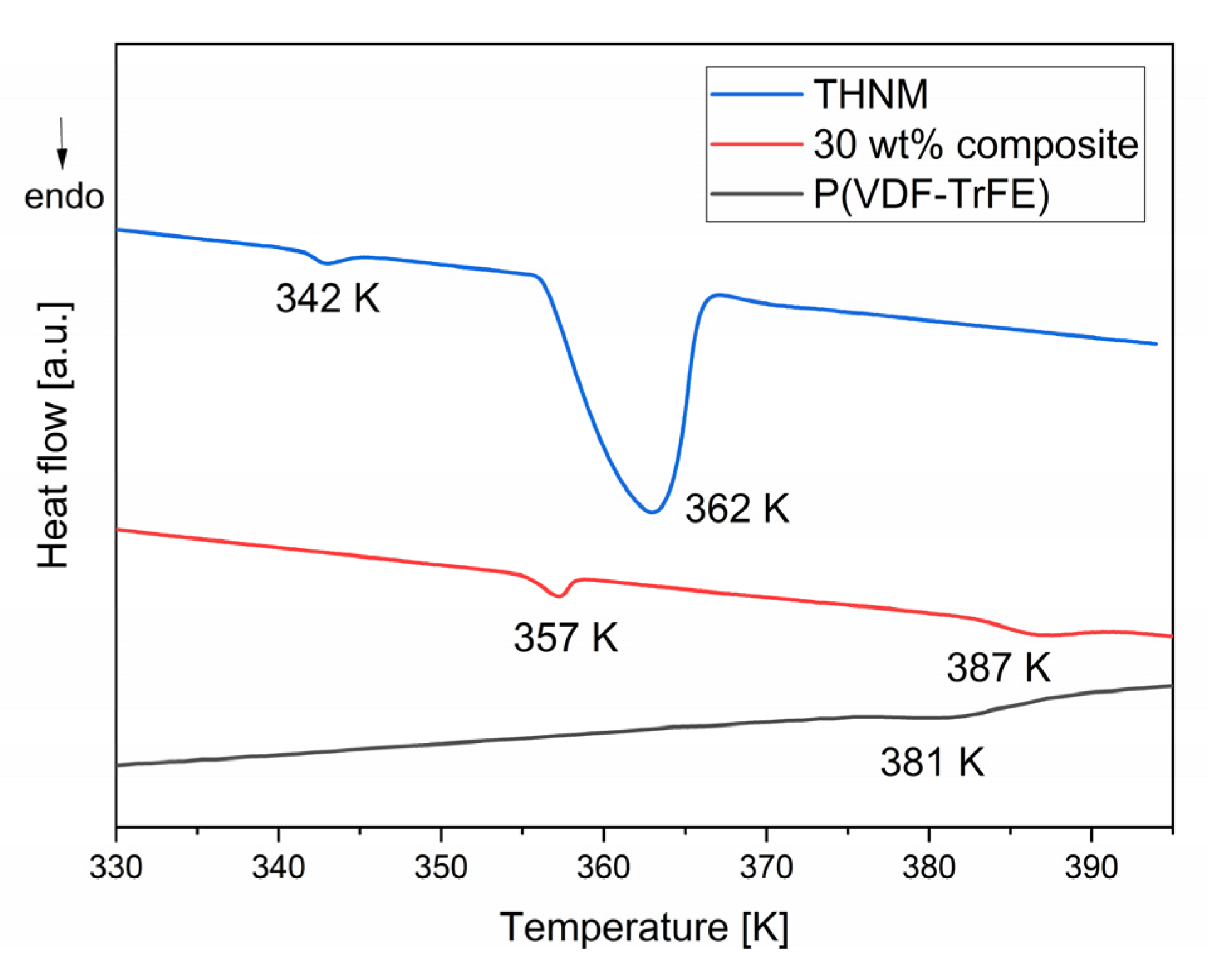

3.1. Analytical Characterization

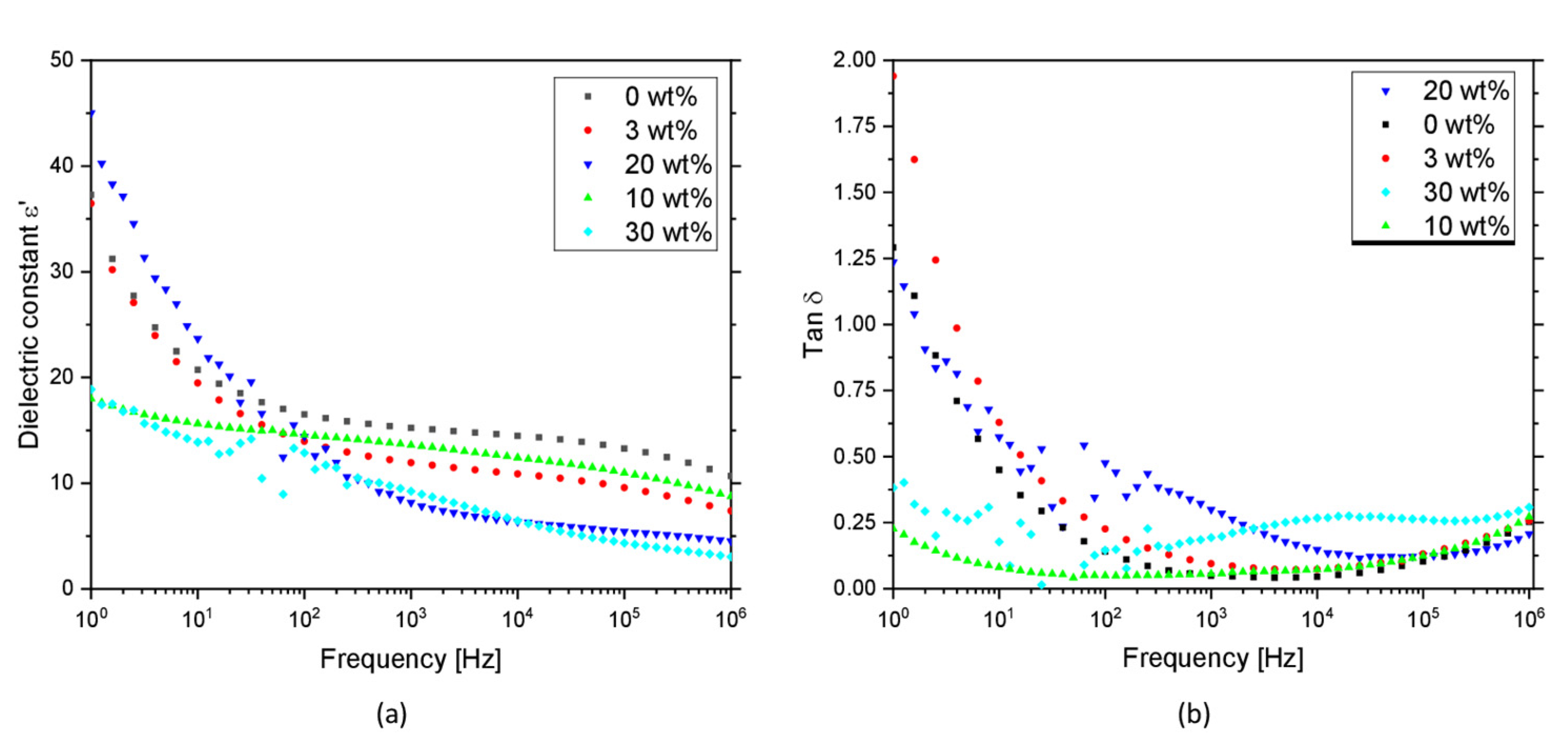

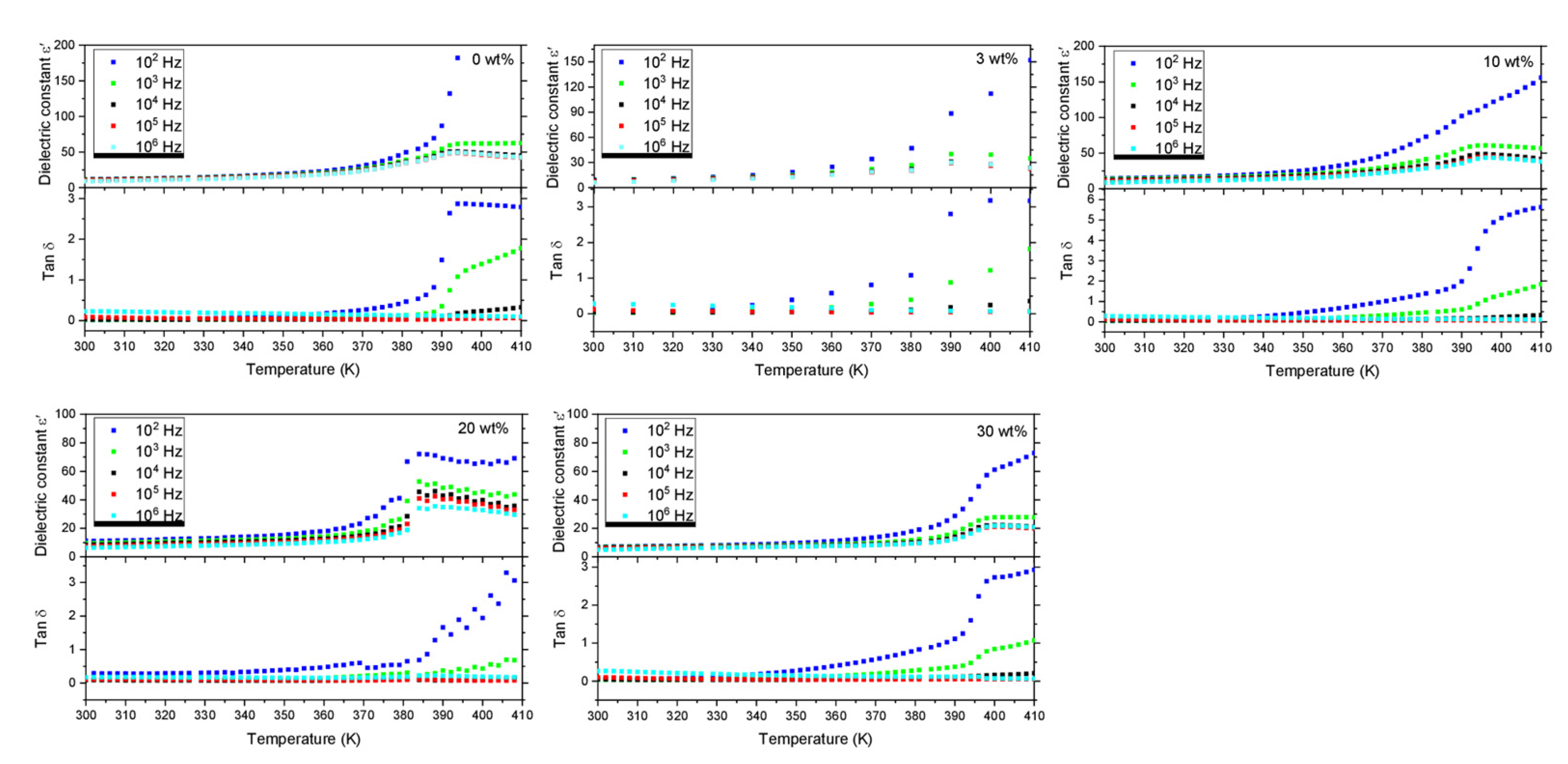

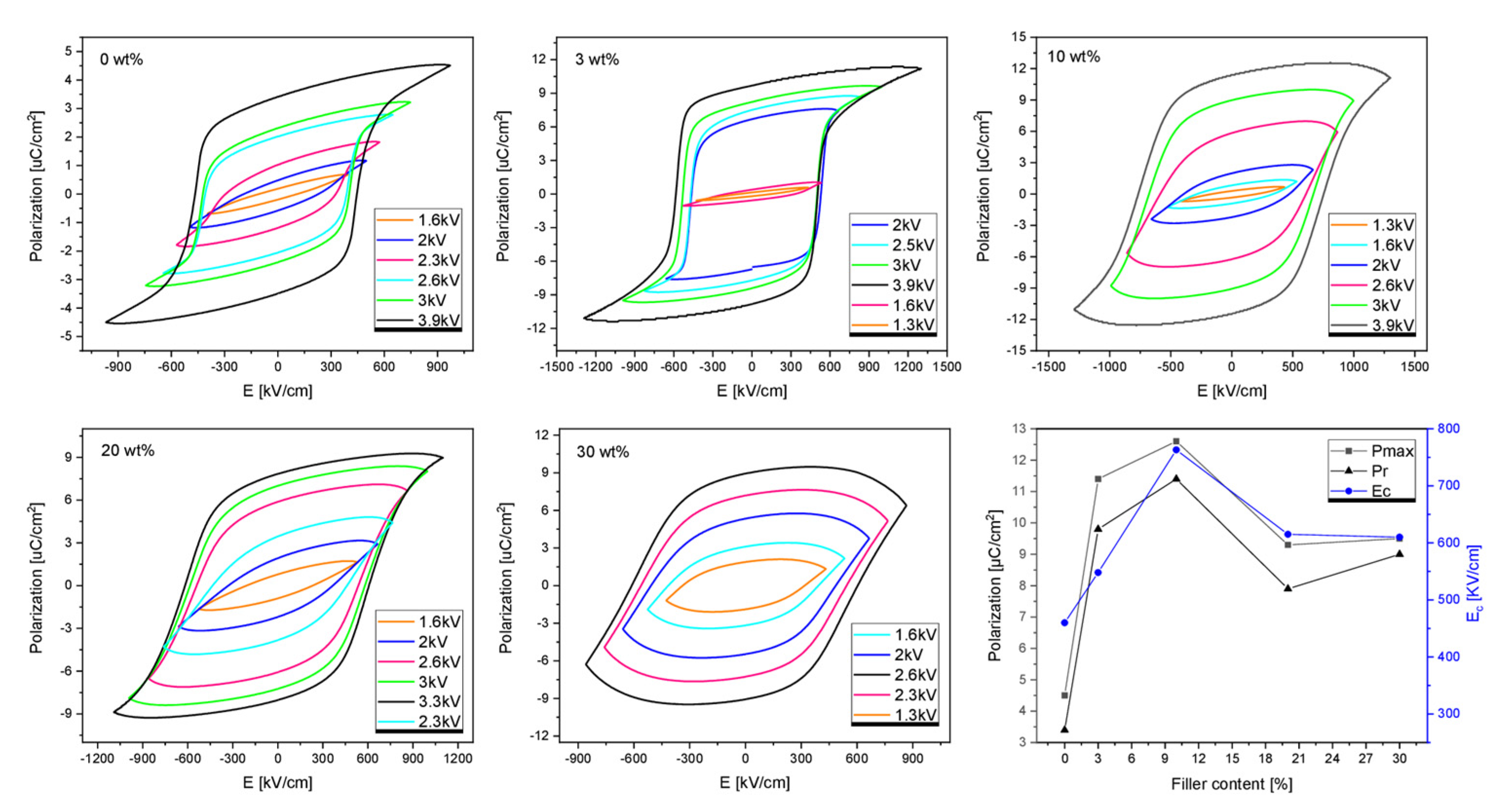

3.2. Electrical Properties and Polarization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P(VDF-TrFE) | Poli(vinylidene fluoride-co-trifluoroethylene) |

| THNM | Tri(hydroxymethyl) nitromethane |

References

- Qian, X. , Xin Chen, Lei Zhu, Q. M. Zhang. Fluoropolymer ferroelectrics: Multifunctional platform for polar-structured energy conversion. Science 2023, 380, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, L.P.S.; Swain, B.; Rajput, S.; Behera, S.; Parida, S. Advances in P(VDF-TrFE) Composites: A Methodical Review on Enhanced Properties and Emerging Electronics Applications. Condens. Matter 2023, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, H. , Astri Bjørnetun Haugen, Kristian Birk Buhl, Kim Daasbjerg, and Shweta Agarwala. Interfacial Engineering of PVDF-TrFE toward Higher Piezoelectric, Ferroelectric, and Dielectric Performance for Sensing and Energy Harvesting Applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanshan G., M. Escobar Castillo, V. V. Shvartsman, M. Karabasov and D.C. Lupascu. (2019). Electrocaloric effect in P(VDF-TrFE)/ barium zirconium titanate composites. In proceedings of ISAF, Lausanne, Switzerland, 14-19 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. , Ke Xu, Jie Li, Lei He, Da-Wei Fu, Qiong Ye, Ren-Gen Xiong. Ferroelectric hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites and their structural and functional diversity. National Science Review 2023, 10, nwac240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergentti, I. Recent advances in molecular ferroelectrics, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 033001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi-Xu Zhang, Hao-Fei Ni, Jing-Song Tang, Pei-Zhi Huang, Jia-Qi Luo, Feng-Wen Zhang, Jia-He Lin, Qiang-Qiang Jia, Gele Teri, Chang-Feng Wang, Da-Wei Fu, and Yi Zhang. Metal-Free Perovskite Ferroelectrics with the Most Equivalent Polarization Axes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 27443–27450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Y. , Han-Yue Zhang, Xiao-Gang Chen, and Ren-Gen Xiong. Molecular Design Principles for Ferroelectrics: Ferroelectrochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 15205–15218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaoyang Li, Yichen Cai, Yongfa Xie, Chenxu Sheng, Yajie Qin, Chunxiao Cong, Zhi-Jun Qiu, Ran Liu, and Laigui Hu. Enhanced dielectric/ferroelectric properties of P(VDF-TrFE) composite films with organic perovskite ferroelectrics. App. Phys. Express 2023, 16, 031008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, R.M.F.; Moreira, G.; Silva, B.; Oliveira, J.; Almeida, B.; Castro, C.; Rodrigues, P.V.; Machado, A.; Belsley, M.; de Matos Gomes, E. Lead-Free MDABCO-NH4I3 Perovskite Crystals Embedded in Electrospun Nanofibers. Materials 2022, 15, 8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Y. , Yu-Ling Zeng, Wen-Hui He, Xue-Qin Huang, and Yuan-Yuan Tang. Six-Fold Vertices in a Single-Component Organic Ferroelectric with most Equivalent Polarization Directions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13989–13995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Liangke, Jin, Zhaonan, Liu, Yaolu, Ning, Huiming, Liu, Xuyang, Alamusi, and Hu, Ning. Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials. Nanotechnology Reviews 2022, 11, 1386–1407. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J. , No, K., Kim, Y. et al. Synthesis and Application of Ferroelectric Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride-co-Trifluoroethylene) Films using Electrophoretic Deposition. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 36176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrigoni, Alessia, Brambilla, Luigi, Bertarelli, Chiara, Serra, Gianluca, Tommasini, Matteo, Castiglioni, Chiara. P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers: structure of the ferroelectric and paraelectric phases through IR and Raman spectroscopies. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 37779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, W. , Mirshekarloo, M. , Chen, S. et al. Nanoconfinement induced crystal orientation and large piezoelectric coefficient in vertically aligned P(VDF-TrFE) nanotube array. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 09790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Berger, W.; Domschke, G.; Fanghänel, E.; Faust, J.; Fischer, M.; Gentz, F.; Gewals, K.; Gluch, R.; Mayer, R.; Müller, K.; Pavel, D.; Schmidt, H.; Schollberg, K.; Schwetlick, K.; Seiler, E.; Zeppenfeld, G. Organikum, 15th ed.; Publisher: VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin, Germany, 1977; pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yang J, Cheng W, Zou J and Zhao D. Progress on Polymer Composites With Low Dielectric Constant and Low Dielectric Loss for High-Frequency Signal Transmission. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 774843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeen, Anshida, M. S., Kala, M. S., Jayalakshmy, Thomas, Sabu, Philip, Jacob, Rouxel, Didier, Bhowmik, R. N., Kalarikkal Nandakumar. Flexible and self-standing nickel ferrite–PVDF-TrFE cast films: promising candidates for high-end magnetoelectric applications. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 16961–16973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Xiofan. , Xia, W., Ping, Y. et al. Dielectric, ferroelectric, and energy conversion properties of a KNN/P(VDF-TrFE) composite film. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2022, 33, 12941–12952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, N. , Okumachi, K., Kinashi, K., Sakai, W. Re-evaluation of the origin of relaxor ferroelectricity in vinylidene fluoride terpolymers: An approach using switching current measurements. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 15871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).