Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

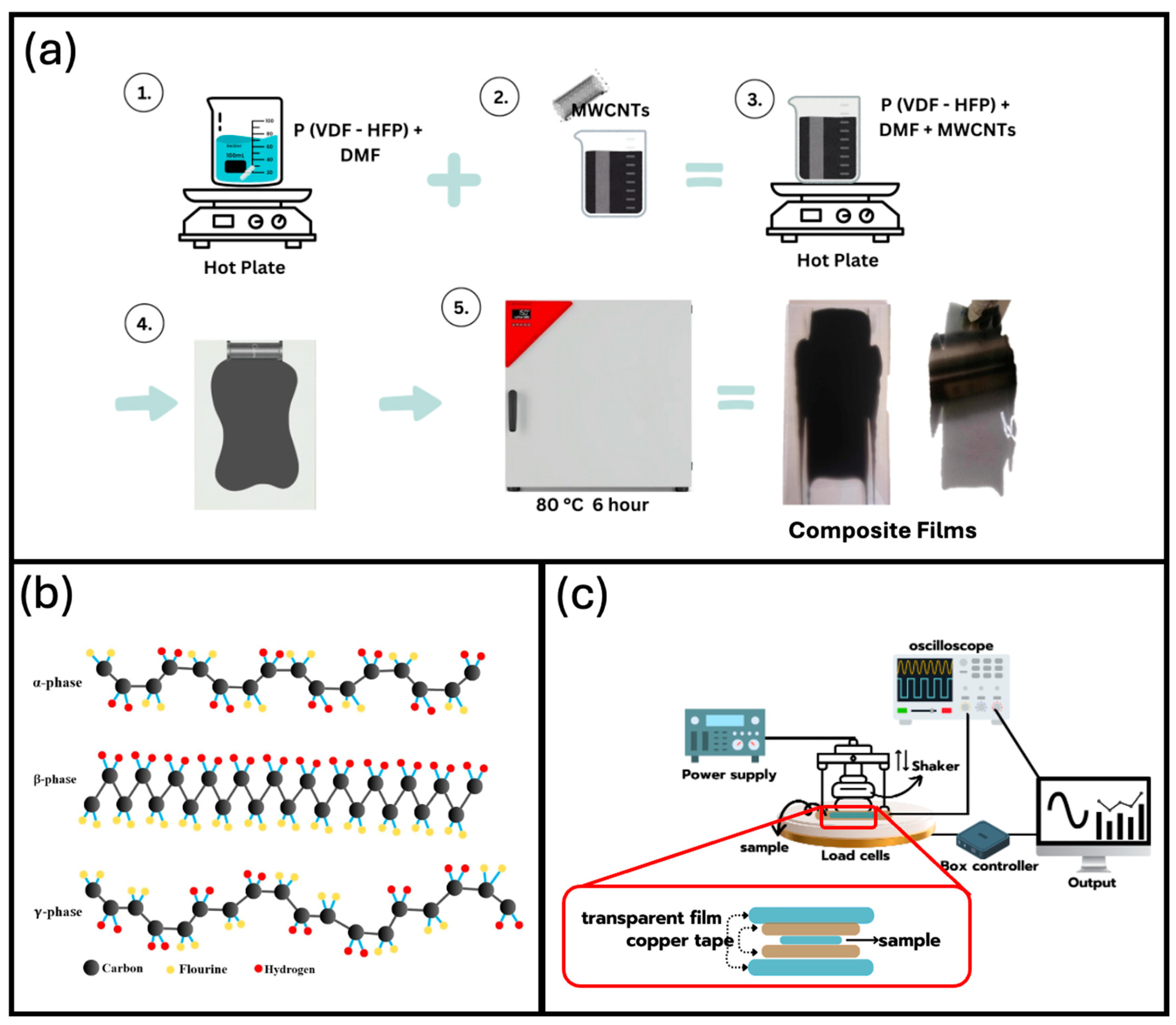

2. Method

2.1. Materials

2.2. Film Preparation

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

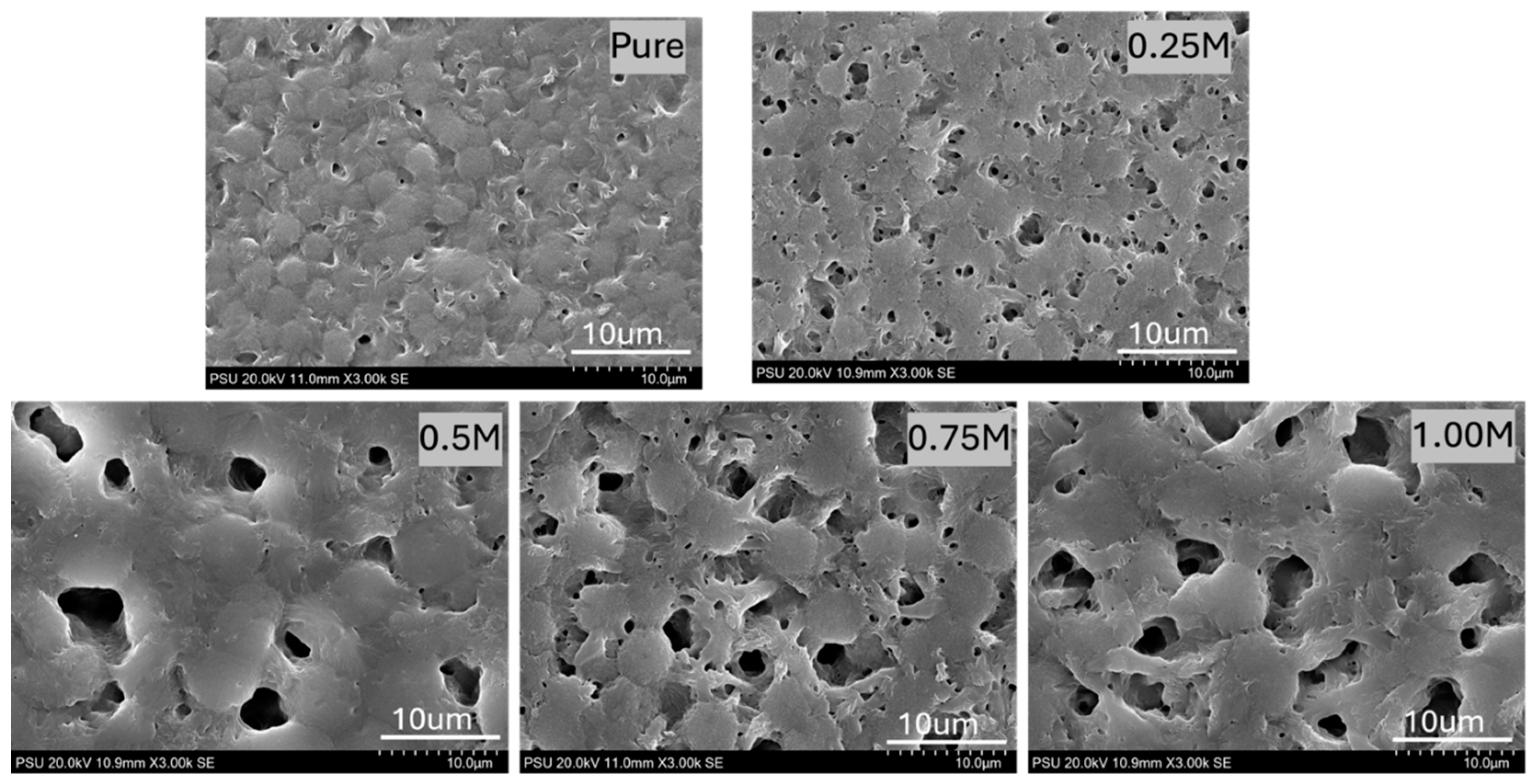

3.1. SEM Analysis

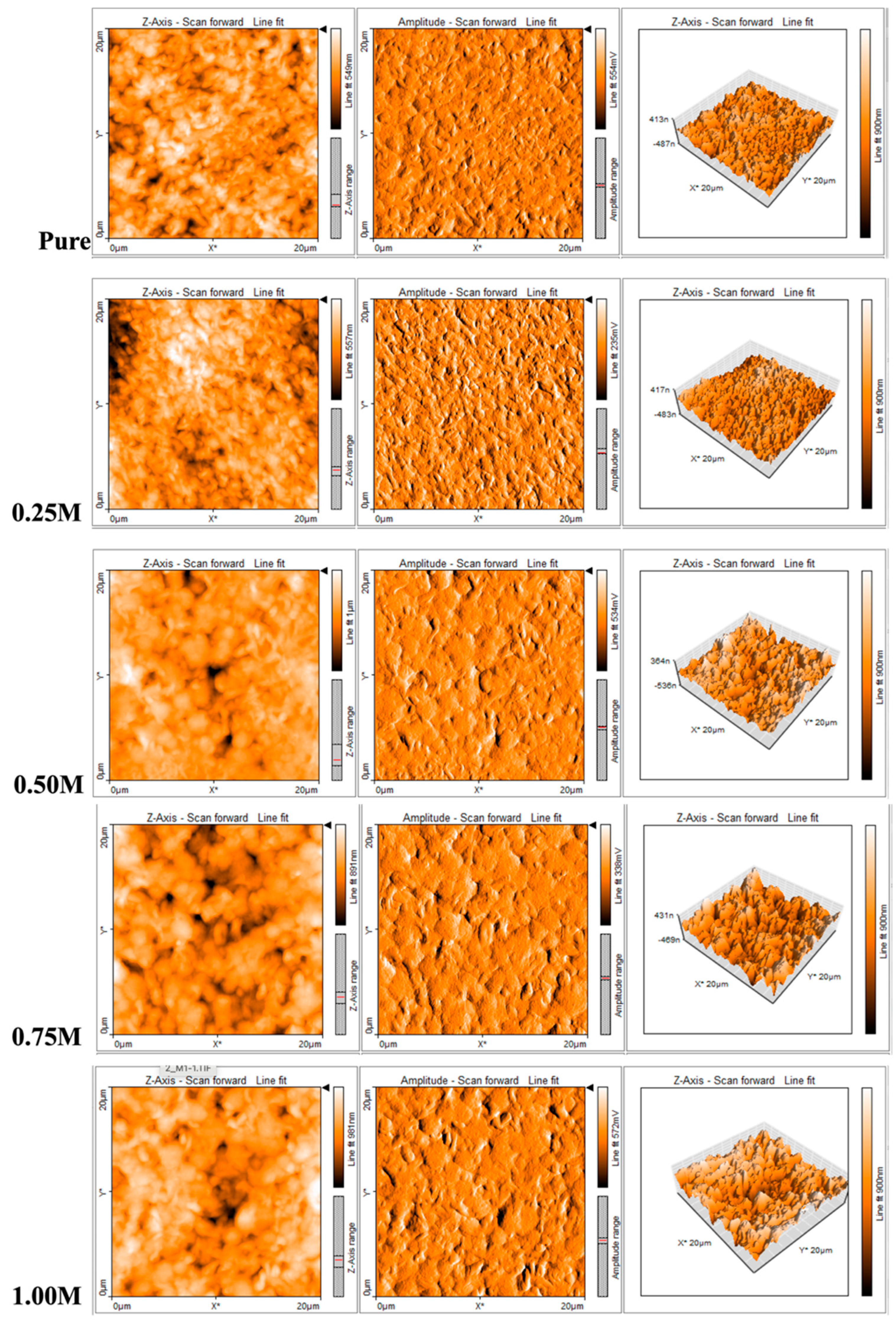

3.2. AFM Analysis

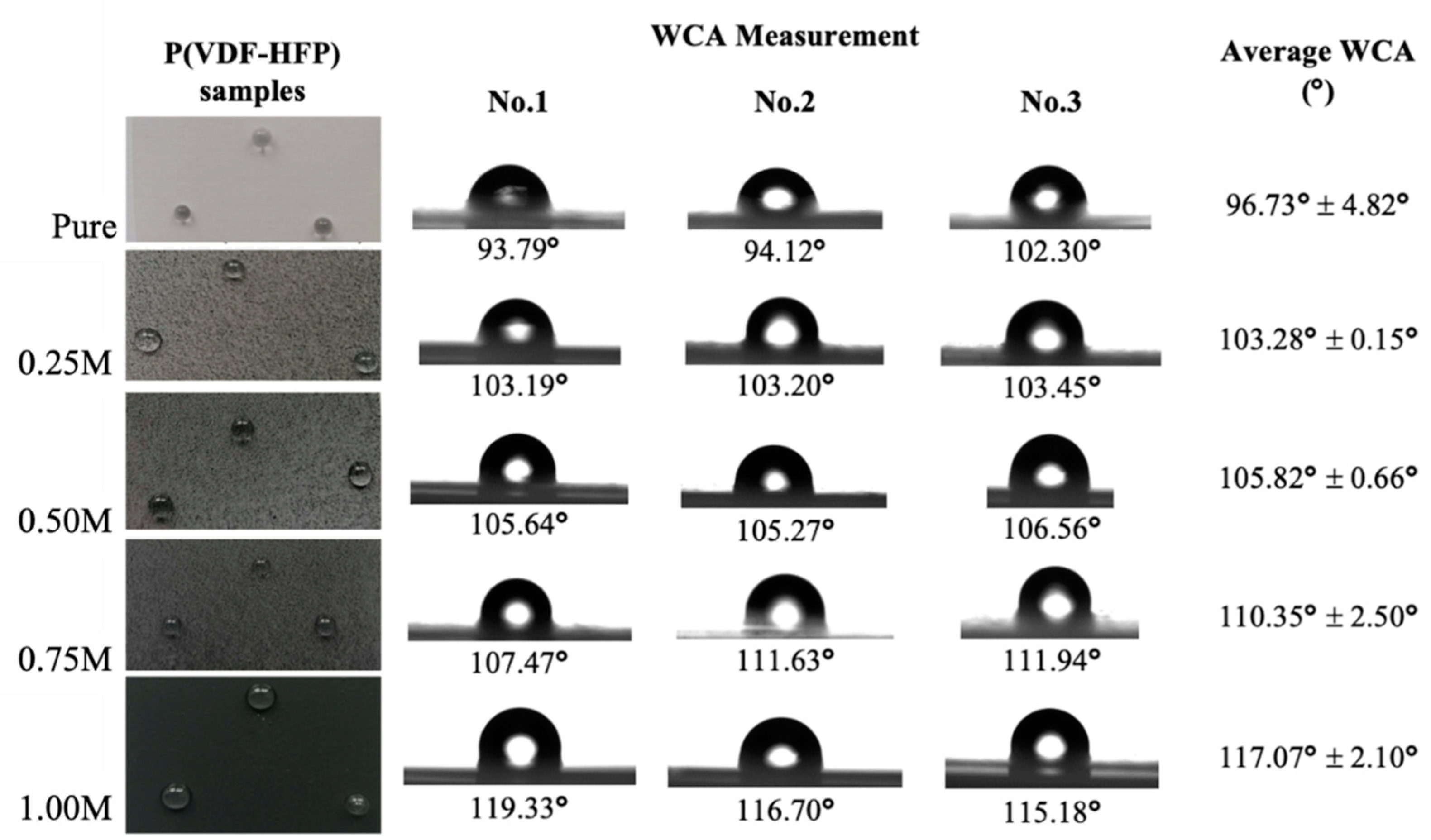

3.3. WCA Analysis

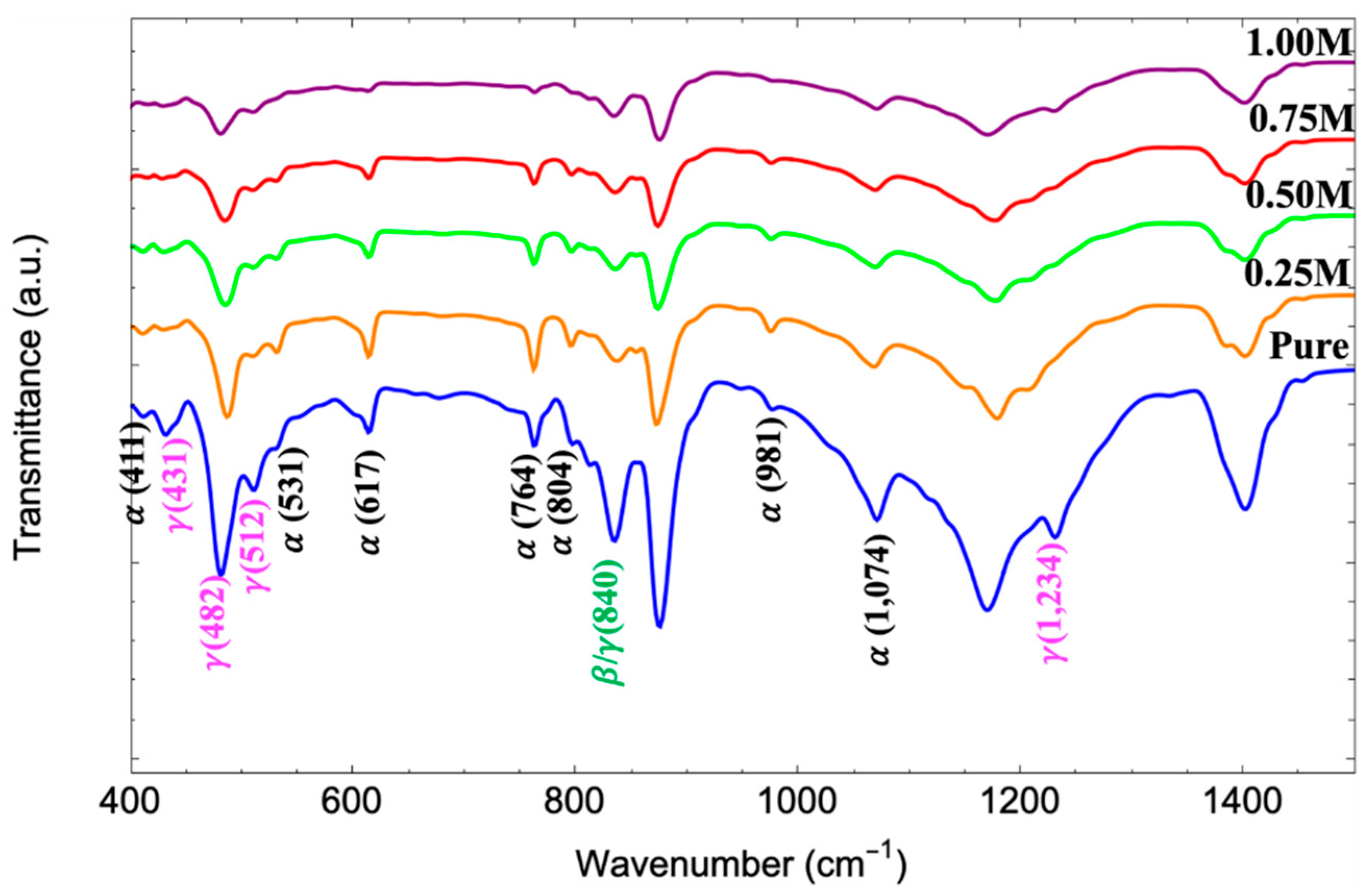

3.4. FTIR Analysis

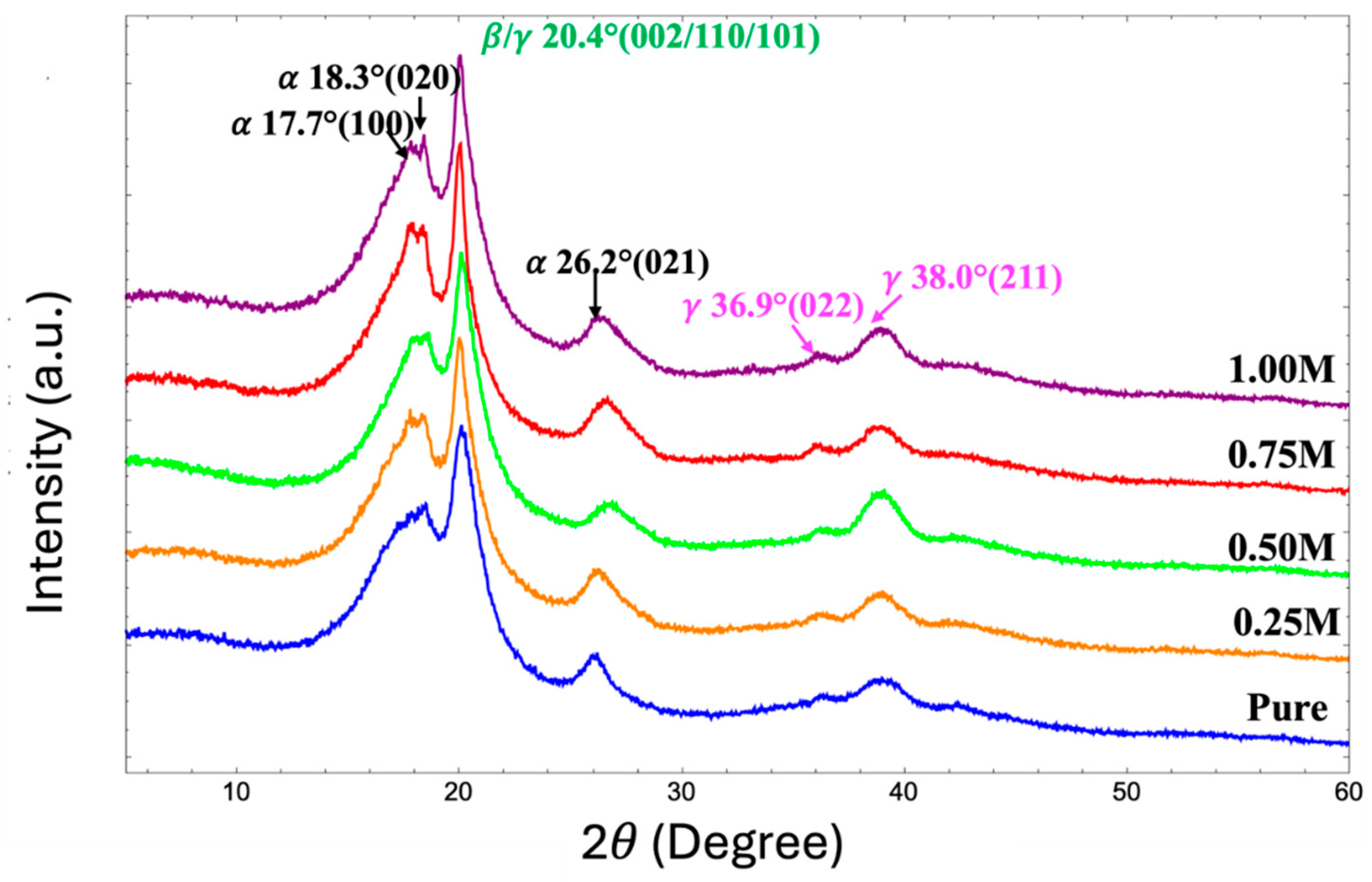

3.5. XRD Analysis

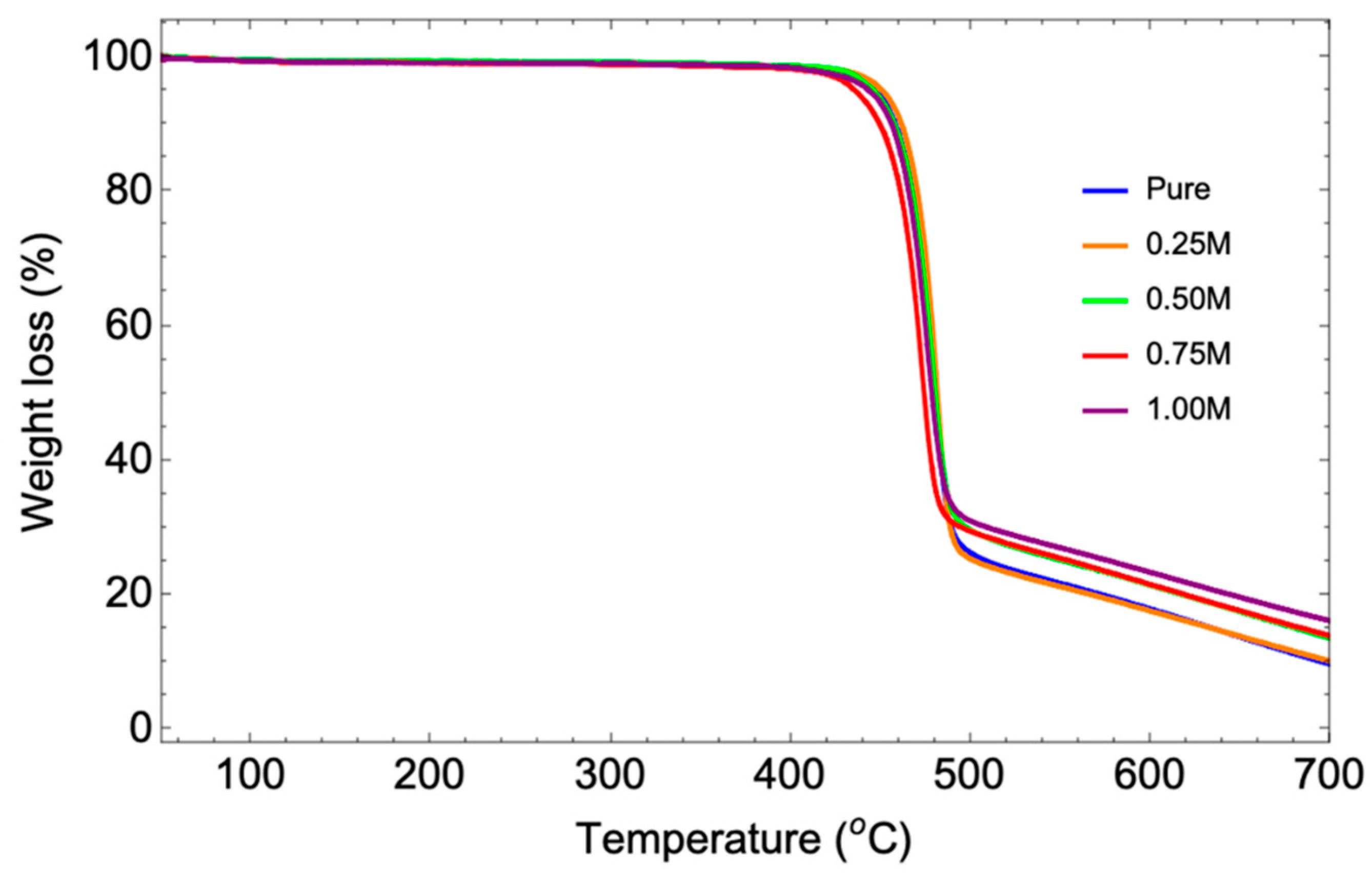

3.6. TGA Analysis

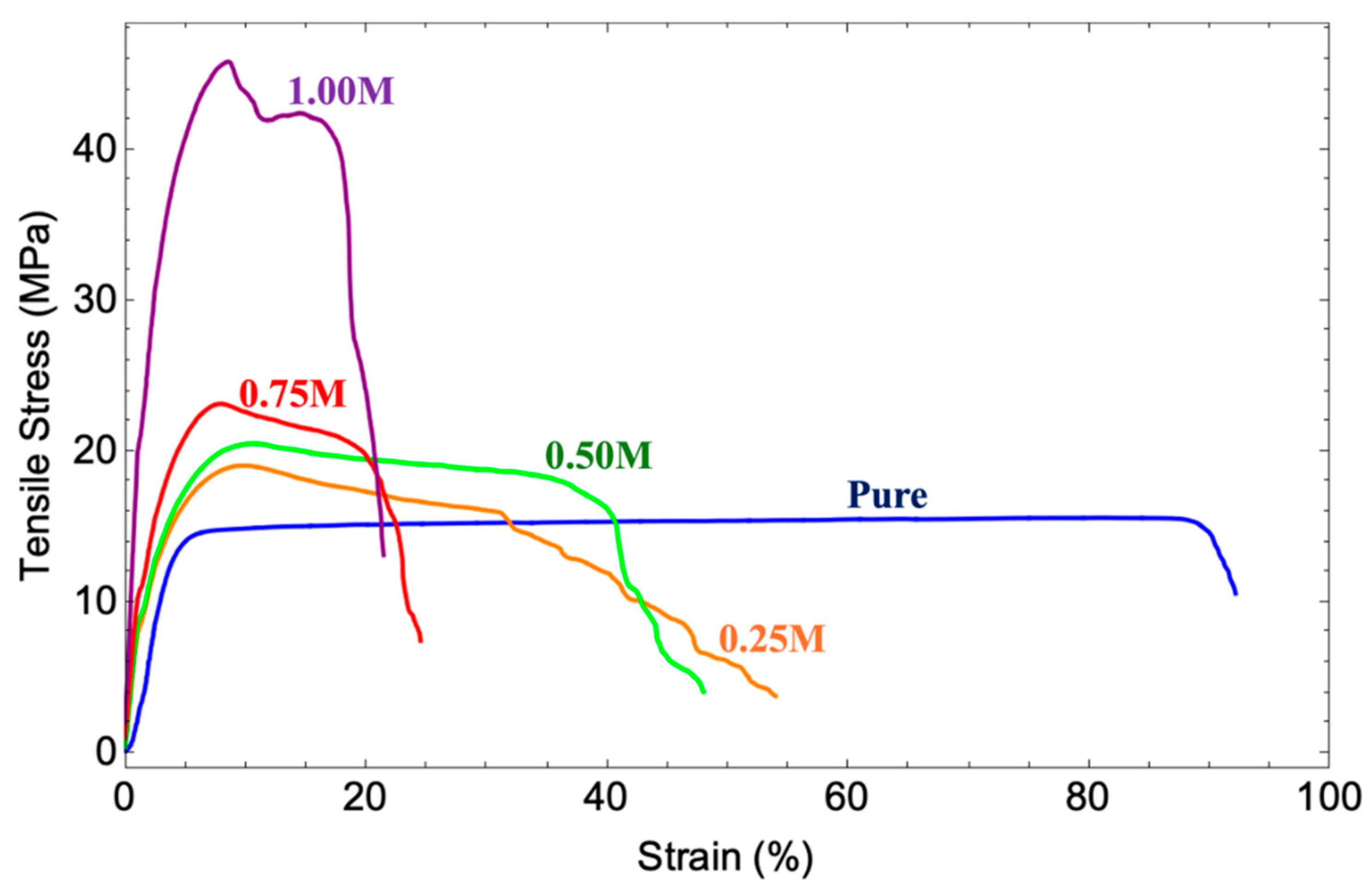

3.7. Tensile Testing Analysis

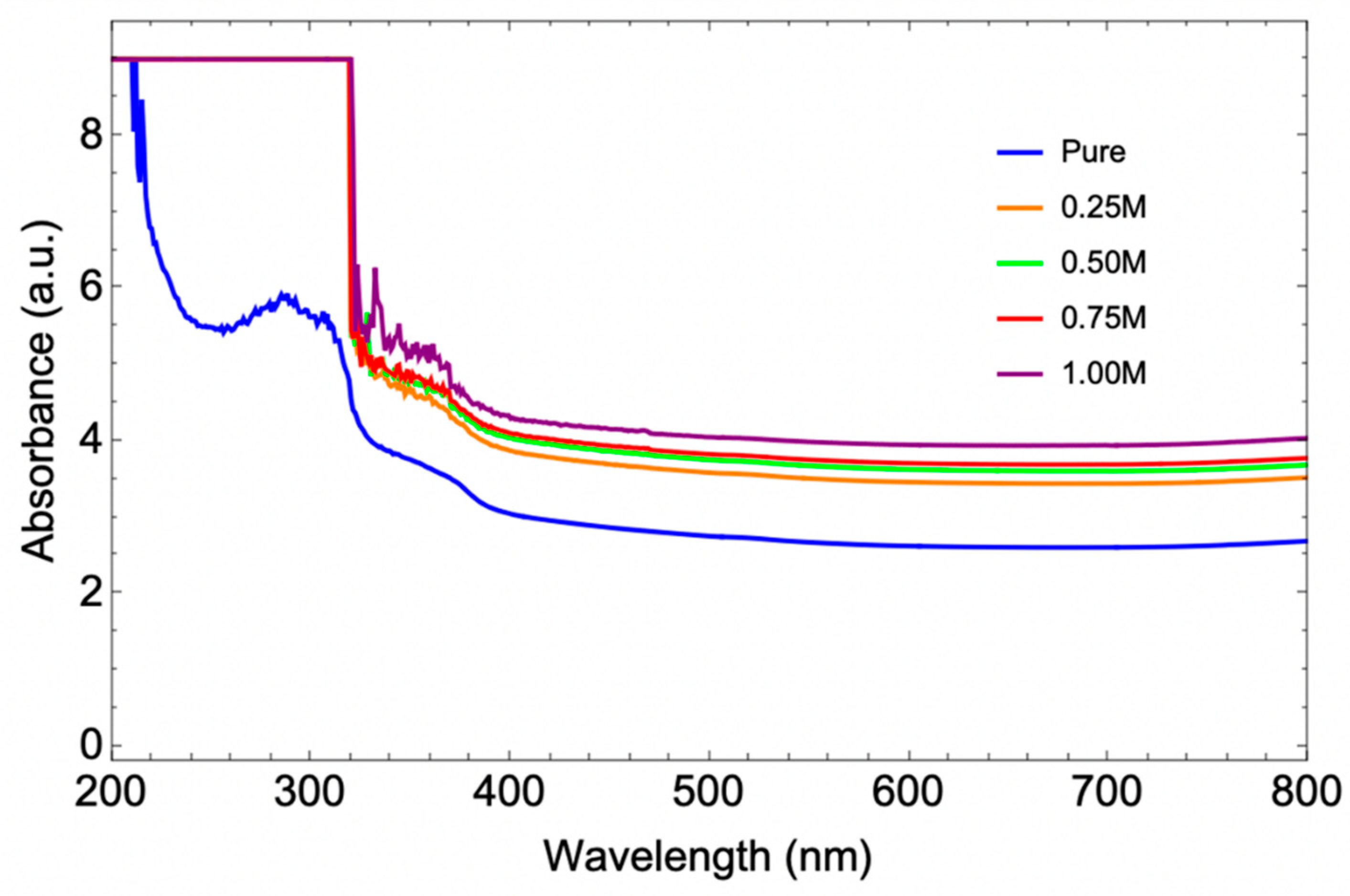

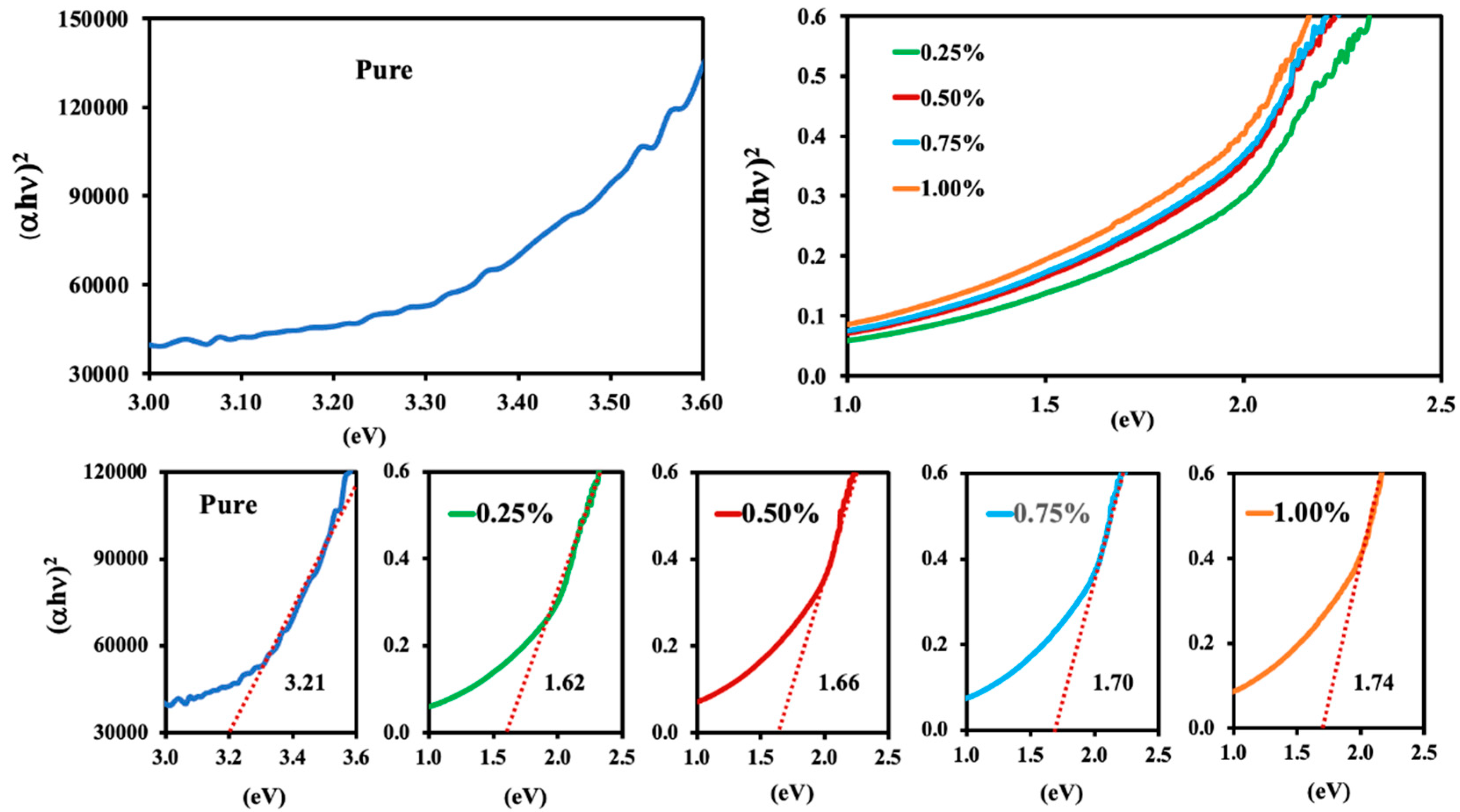

3.8. Optical Properties Analysis

3.9. Dielectric Behavior

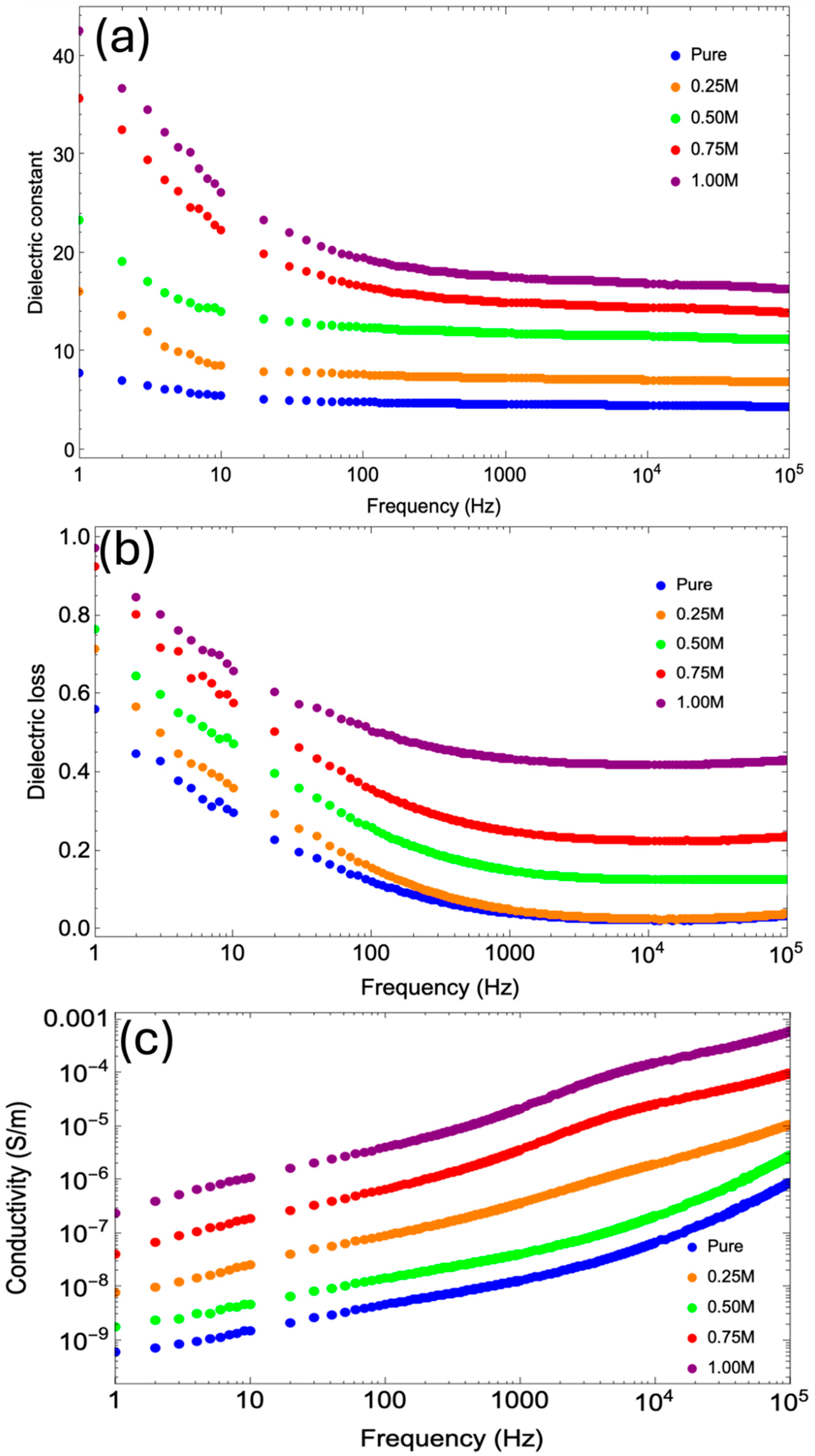

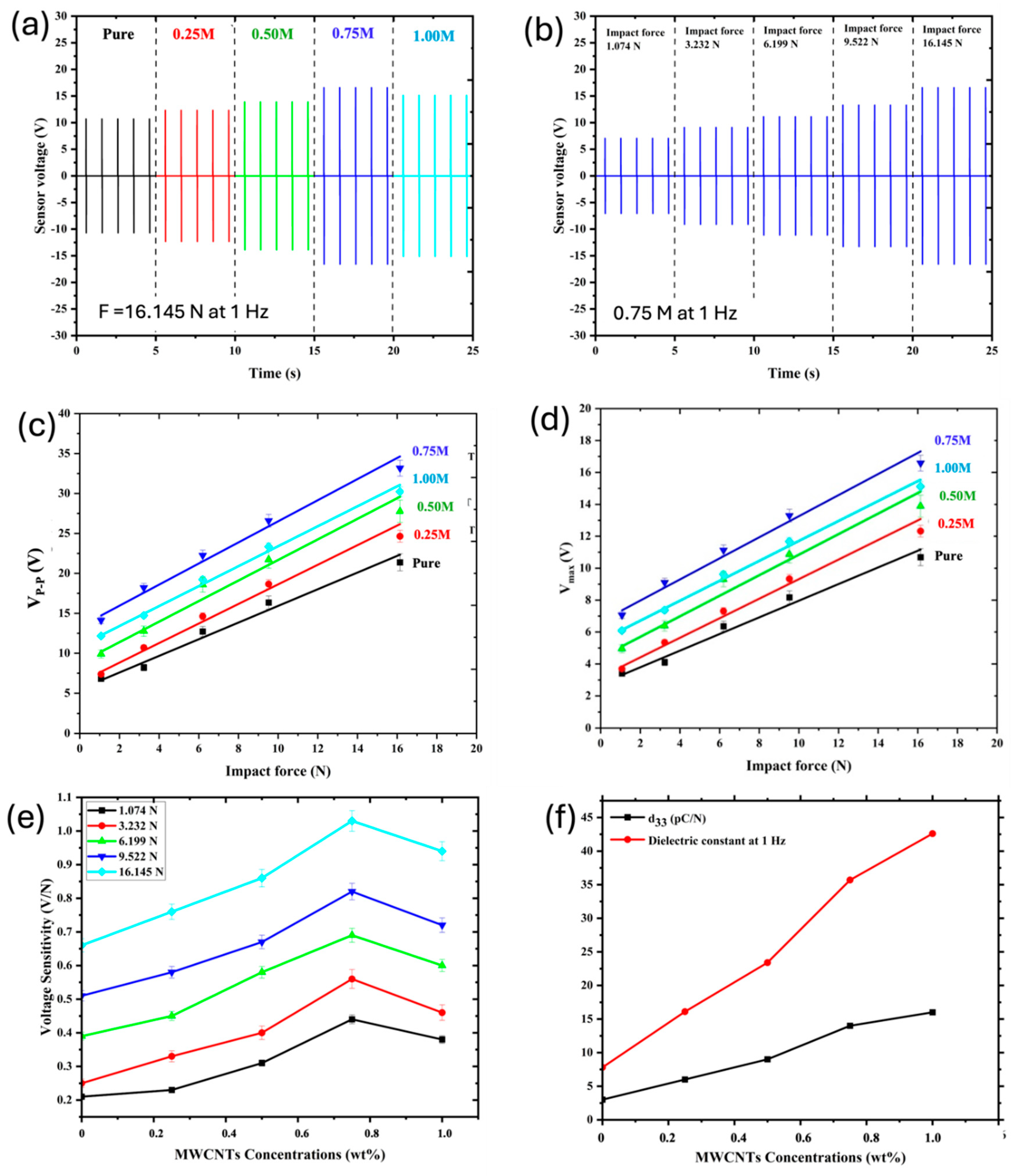

3.9. Piezoelectric Performance Testing

4. Conclusions

<b>Acknowledgments</b>

Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeyrek Ongun, M., et al., Enhancement of piezoelectric energy-harvesting capacity of electrospun β-PVDF nanogenerators by adding GO and rGO. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2020. 31(3): p. 1960-1968. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., et al., Formation mechanisms and electrical properties of perovskite mesocrystals. Ceramics International, 2021. 47(2): p. 1479-1512. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R. and Z. Wang, 9 - Piezoelectric one- to two-dimensional nanomaterials for vibration energy harvesting devices, in Emerging 2D Materials and Devices for the Internet of Things, L. Tao and D. Akinwande, Editors. 2020, Elsevier. p. 221-241.

- Anton, S.R. and M. Safaei, Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting, in Encyclopedia of Smart Materials, A.-G. Olabi, Editor. 2022, Elsevier: Oxford. p. 104-116.

- Messer, D.K., et al., Characterization and calibration of a piezo-energetic composite film as a reactive gauge. Journal of Applied Physics, 2024. 135(14). [CrossRef]

- Maity, K. and D. Mandal, Chapter Seven - Piezoelectric polymers and composites for multifunctional materials, in Advanced Lightweight Multifunctional Materials, P. Costa, C.M. Costa, and S. Lanceros-Mendez, Editors. 2021, Woodhead Publishing. p. 239-282.

- Su, F. and M. Miao, Effect of MWCNT dimension on the electrical percolation and mechanical properties of poly(vinylidenefluoride-hexafluoropropylene) based nanocomposites. Synthetic Metals, 2014. 191: p. 99-103. [CrossRef]

- Shepelin, N.A., et al., New developments in composites, copolymer technologies and processing techniques for flexible fluoropolymer piezoelectric generators for efficient energy harvesting. Energy & Environmental Science, 2019. 12(4): p. 1143-1176. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., et al., Effect of crystalline phase on the dielectric and energy storage properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride). Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2016. 27. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R. and S.K. Rout, Influence of annealing temperature on the existence of polar domain in uniaxially stretched polyvinylidene-co-hexafluoropropylene for energy harvesting applications. Journal of Applied Physics, 2020. 128(23). [CrossRef]

- Roy, S., et al., Enhanced electroactive β-phase nucleation and dielectric properties of PVdF-HFP thin films influenced by montmorillonite and Ni(OH)2 nanoparticle modified montmorillonite. RSC Advances, 2016. 6(26): p. 21881-21894. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., et al., Effect of multi-step processing on the structural, morphological and dielectric behaviour of PVDF films. Ionics, 2020. 26(12): p. 6069-6081. [CrossRef]

- Yasar, M., et al., β Phase Optimization of Solvent Cast PVDF as a Function of the Processing Method and Additive Content. ACS Omega, 2024. 9(24): p. 26020-26029. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Effects of stretching on phase transformation of PVDF and its copolymers: A review. 2023. 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Mahadeva, S.K., et al., Effect of poling time and grid voltage on phase transition and piezoelectricity of poly(vinyledene fluoride) thin films using corona poling. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 2013. 46(28): p. 285305. [CrossRef]

- Salama, M., et al., Boosting piezoelectric properties of PVDF nanofibers via embedded graphene oxide nanosheets. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 16484. [CrossRef]

- Al-Abduljabbar, A. and I. Farooq Electrospun Polymer Nanofibers: Processing, Properties, and Applications. Polymers, 2023. 15. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., Enhanced piezoelectric performance of multi-layered flexible polyvinylidene fluoride–BaTiO3–rGO films for monitoring human body motions. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2022. 33(7): p. 4291-4304.

- Ezquerra, T., et al., On the electrical conductivity of PVDF composites with different carbon-based nanoadditives. Colloid and Polymer Science, 2014. 292: p. 1989-1998. [CrossRef]

- Rehwoldt, M.C., et al., High-Temperature Interactions of Metal Oxides and a PVDF Binder. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022. 14(7): p. 8938-8946. [CrossRef]

- Eggedi, O., et al., Nanoindentation and thermal characterization of poly (vinylidenefluoride)/MWCNT nanocomposites. AIP Advances, 2014. 4(4).

- Liu, X., et al., Ultra-long MWCNTs highly oriented in electrospun PVDF/MWCNT composite nanofibers with enhanced β phase. RSC Advances, 2016. 6(108): p. 106690-106696. [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthi, M.A. and M. Hussain Effect of the Surface Functionalization of Graphene and MWCNT on the Thermodynamic, Mechanical and Electrical Properties of the Graphene/MWCNT-PVDF Nanocomposites. Polymers, 2022. 14. [CrossRef]

- Begum, S., et al., Investigation of morphology, crystallinity, thermal stability, piezoelectricity and conductivity of PVDF nanocomposites reinforced with epoxy functionalized MWCNTs. Composites Science and Technology, 2021. 211: p. 108841. [CrossRef]

- Xinya, W., et al., Fabrication and properties of PVDF and PVDF-HFP microfiltration membranes. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2018. 135: p. 46711.

- Zaszczyńska, A., et al. Enhanced Electroactive Phases of Poly(vinylidene Fluoride) Fibers for Tissue Engineering Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25. [CrossRef]

- Sharafkhani, S. and M. Kokabi, High performance flexible actuator: PVDF nanofibers incorporated with axially aligned carbon nanotubes. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2021. 222: p. 109060. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L., et al., Enhancement of β-Phase Crystal Content of Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Nanofiber Web by Graphene and Electrospinning Parameters. Chinese Journal of Polymer Science, 2020. 38(11): p. 1239-1247. [CrossRef]

- Garain, S., et al., Design of In Situ Poled Ce3+-Doped Electrospun PVDF/Graphene Composite Nanofibers for Fabrication of Nanopressure Sensor and Ultrasensitive Acoustic Nanogenerator. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2016. 8(7): p. 4532-4540 4532-4540. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J., et al. Electromechanical Properties of PVDF-Based Polymers Reinforced with Nanocarbonaceous Fillers for Pressure Sensing Applications. Materials, 2019. 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. and S. Lim, Boosting Performance of Self-Polarized Fully Printed Piezoelectric Nanogenerators via Modulated Strength of Hydrogen Bonding Interactions. Nanomaterials (Basel), 2021. 11(8). [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J., et al., PVDF based nanocomposites produced by solution blow spinning, structure and morphology induced by the presence of MWCNT and their consequences on some properties. Colloid and Polymer Science, 2019. 297(7): p. 1105-1118. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., et al. Significantly Suppressed Dielectric Loss and Enhanced Breakdown Strength in Core@Shell Structured Ni@TiO2/PVDF Composites. Nanomaterials, 2023. 13. [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, K., et al., Aligned carbon nanotube/polymer hybrid electrolytes for high performance dye sensitized solar cell applications. RSC Advances, 2015. 5(82): p. 66563-66574. [CrossRef]

- Wan, C. and C.R. Bowen, Multiscale-structuring of polyvinylidene fluoride for energy harvesting: the impact of molecular-, micro- and macro-structure. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2017. 5(7): p. 3091-3128. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., et al., A review on microporous polyvinylidene fluoride membranes fabricated via thermally induced phase separation for MF/UF application. Journal of Membrane Science, 2021. 639: p. 119759. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.-P., Effect of Temperature on the Formation of Microporous PVDF Membranes by Precipitation from 1-Octanol/DMF/PVDF and Water/DMF/PVDF Systems. Macromolecules, 1999. 32(20): p. 6668-6674. [CrossRef]

- Peng, L., et al., Preparation of NaCl Particles Added Polyvinylidene Fluoride Microporous Filter and a Simple Filtration Device. Coatings, 2024. 14(2): p. 196. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., et al., Investigations on dielectric and mechanical properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP)/single-walled carbon nanotube composites. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 2023. 25(12): p. 246.

- Chae, J., et al., Modification of the Surface Morphology and Properties of Graphene Oxide and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube-Based Polyvinylidene Fluoride Membranes According to Changes in Non-Solvent Temperature. Nanomaterials, 2021. 11(9): p. 2269. Nanomaterials, 2021. 11(9): p. 2269. [CrossRef]

- Croll, S.G., Surface roughness profile and its effect on coating adhesion and corrosion protection: A review. Progress in Organic Coatings, 2020. 148: p. 105847. [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, B., A. Anand Prabu, and M. Pathak, Enhancing piezoelectric effect of PVDF electrospun fiber through NiO nanoparticles for wearable applications. Heliyon, 2024. 10(7): p. e29192. [CrossRef]

- Mapunda, E.C., B.B. Mamba, and T.A.M. Msagati, Carbon nanotube embedded PVDF membranes: Effect of solvent composition on the structural morphology for membrane distillation. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 2017. 100: p. 135-142. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., A. Soroush, and M.S. Rahaman, Highly Hydrophobic Electrospun Reduced Graphene Oxide/Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) Membranes for Use in Membrane Distillation. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2018. 57(43): p. 14535-1454314535-14543. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., et al., Table Salt as a Template to Prepare Reusable Porous PVDF–MWCNT Foam for Separation of Immiscible Oils/Organic Solvents and Corrosive Aqueous Solutions. Advanced Functional Materials, 2017. 27(41): p. 1702926. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., et al., Soft wetting: Modified Cassie-Baxter equation for soft superhydrophobic surfaces. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2023. 677: p. 132348. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X., et al., A critical analysis of the α, β and γ phases in poly(vinylidene fluoride) using FTIR. RSC Advances, 2017. 7(25): p. 15382-15389.

- Shalu, V.K. Singh, and R.K. Singh, Development of ion conducting polymer gel electrolyte membranes based on polymer PVdF-HFP, BMIMTFSI ionic liquid and the Li-salt with improved electrical, thermal and structural properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2015. 3(28): p. 7305-7318. [CrossRef]

- Ke, K., et al., Achieving β-phase poly(vinylidene fluoride) from melt cooling: Effect of surface functionalized carbon nanotubes. Polymer, 2014. 55(2): p. 611-619. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Y. Song, and M.J. Heller, Influence of MWCNTs on β-Phase PVDF and Triboelectric Properties. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2017. 2017(1): p. 2697382. [CrossRef]

- Barrau, S., et al., Nanoscale Investigations of α- and γ-Crystal Phases in PVDF-Based Nanocomposites. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2018. 10(15): p. 13092-13099. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.-Y., et al., Formation of Porous Structures and Crystalline Phases in Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Membranes Prepared with Nonsolvent-Induced Phase Separation—Roles of Solvent Polarity. Polymers, 2023. 15(5): p. 1314. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, I.Y., et al., Facile formation of [beta] poly (vinylidene fluoride) films using the short time annealing process. Advances in Environmental Biology, 2015. 9: p. 20+.

- Tohluebaji, N., et al., Improved Electroactive β Phase Nucleation and Dielectric Properties of P(VDF-HFP) Composite with Al(NO3)3·9H2O Fillers. Integrated Ferroelectrics, 2022. 224(1): p. 181-191.

- Gregorio Jr., R., Determination of the α, β, and γ crystalline phases of poly(vinylidene fluoride) films prepared at different conditions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2006. 100(4): p. 3272-3279.

- Eun, J.H., et al., Effect of MWCNT content on the mechanical and piezoelectric properties of PVDF nanofibers. Materials & Design, 2021. 206: p. 109785. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al., Influence of crystalline properties on the dielectric and energy storage properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride). Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2011. 122(3): p. 1659-1668. [CrossRef]

- Salman, S.A., F.T.M. Noori, and A.K. Mohammed. Preparation and Characterizations of Poly ( vinylidene fluoride ) ( PVDF ) / Ba 0 . 6 Sr 0 . 4 TiO 3 ( BST ) Nanocomposites. 2018.

- Singh, P., et al., Ferroelectric polymer-ceramic composite thick films for energy storage applications. AIP Advances, 2014. 4(8). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., et al., Investigation of morphology and dielectric properties of PVDF composite films reinforced with MWCNT@PDA core–shell nanorods. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2022. 33: p. 6842 - 6855. [CrossRef]

- Ponnamma, D., et al., Stretchable quaternary phasic PVDF-HFP nanocomposite films containing graphene-titania-SrTiO3 for mechanical energy harvesting. Emergent Materials, 2018. 1(1): p. 55-65. [CrossRef]

- Che, B.D., et al., The impact of different multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the X-band microwave absorption of their epoxy nanocomposites. Chem Cent J, 2015. 9: p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J., et al., Carbon nanotubes interaction with amorphous and semi-crystalline domains of polypropylene in melt-mixed composites: Influence of multiwall carbon nanotubes agglomerate and their modifications. SPE Polymers, 2021. 2(4): p. 257-275. [CrossRef]

- Sezer, N. and M. Koç, A comprehensive review on the state-of-the-art of piezoelectric energy harvesting. Nano Energy, 2021. 80: p. 105567. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al., Fabrication of MWCNT and phenolic epoxy resin reinforced PVDF: a composite with low dielectric loss and excellent mechanical properties. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A, 2021. 58(7): p. 482-491.

- Nady, N., N. Salem, and S.H. Kandil Preparation and Characterization of a Novel Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene)/Poly(ethersulfone) Blend Membrane Fabricated Using an Innovative Method of Mixing Electrospinning and Phase Inversion. Polymers, 2021. 13. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, S.F., et al., Effect of filler size and concentration on the structure and properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/BaTiO3 nanocomposites. Journal of Materials Science, 2012. 47(3): p. 1378-1388.

- Botelho, G., et al., Relationship between processing conditions, defects and thermal degradation of poly(vinylidene fluoride) in the β-phase. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 2008. 354(1): p. 72-78.

- de Jesus Silva, A.J., et al., Kinetics of thermal degradation and lifetime study of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) subjected to bioethanol fuel accelerated aging. Heliyon, 2020. 6(7): p. e04573. [CrossRef]

- Polat, K., Energy harvesting from a thin polymeric film based on PVDF-HFP and PMMA blend. Applied Physics A, 2020. 126(7): p. 497. [CrossRef]

- Abutaleb, A., S. Hussain, and M. Imran, Systematic exploration of electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)/multi-walled carbon nanotubes’ (MWCNTs) composite nanofibres for humidity sensing application. Journal of Taibah University for Science, 2021. 15(1): p. 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K., et al., Fluoro-polymer functionalized graphene for flexible ferroelectric polymer-based high-k nanocomposites with suppressed dielectric loss and low percolation threshold. Nanoscale, 2014. 6(24): p. 14740-14753. [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthi, M.A. and M. Hussain, Effect of the Surface Functionalization of Graphene and MWCNT on the Thermodynamic, Mechanical and Electrical Properties of the Graphene/MWCNT-PVDF Nanocomposites. Polymers, 2022. 14(15): p. 297. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Hydrophilicity, pore structure and mechanical performance of CNT/PVDF materials affected by carboxyl contents in multi-walled carbon nanotubes. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2018. 284(1): p. 012009.

- Indriyati, et al., Nanocomposites of polyvinylidene fluoride copolymer-functionalized carbon nanotubes prepared by electrospinning method. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2020. 483(1): p. 012045.

- Ellingford, C., et al., Electrical dual-percolation in MWCNTs/SBS/PVDF based thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) composites and the effect of mechanical stretching. European Polymer Journal, 2019. 112: p. 504-514. [CrossRef]

- Yuennan, J., et al., Enhanced electroactive β-phase and dielectric properties in P(VDF-HFP) composite flexible films through doping with three calcium chloride salts: CaCl, CaCl·2HO, and CaCl·6HO. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 2024. 35(6): p. e6437.

- Yang, J., et al., Realizing the full nanofiller enhancement in melt-spun fibers of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/carbon nanotube composites. Nanotechnology, 2011. 22(35): p. 355707.

- Kong, F., M. Chang, and Z. Wang, Comprehensive Analysis of Mechanical Properties of CB/SiO(2)/PVDF Composites. Polymers (Basel), 2020. 12(1).

- Khade, V. and M. Wuppulluri, Microwave Absorption Performance of Flexible Porous PVDF-MWCNT Foam in the X-Band Frequency Range. ACS Omega, 2024. 9(33): p. 35364-35373. [CrossRef]

- Taha, T.A.M., et al., Structure–Property Relationships in PVDF/SrTiO3/CNT Nanocomposites for Optoelectronic and Solar Cell Applications. Polymers, 2024. 16(6): p. 73.

- Khannam, M., et al., Enhanced conversion efficiency of quasi solid state dye sensitized solar cells based on functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes incorporated TiO2 photoanode. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2016. 27(10): p. 10010-10019. [CrossRef]

- Larosa, C., et al., Preparation and characterization of polycarbonate/multiwalled carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology, 2017. 8: p. 2026-2031. [CrossRef]

- Madivalappa, S., et al., Insights and perspectives on PVDF/MgO NCs films: Structural, optical and dielectric properties. Results in Chemistry, 2024: p. 101764. [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.I. and K. Ramachandran, Dielectric studies on hybridised PVDF–ZnO nanocomposites. Journal of Experimental Nanoscience, 2011. 6(3): p. 281-293. [CrossRef]

- Ji, W., et al., The enhancement in dielectric properties for PVDF based composites due to the incorporation of 2D TiO2 nanobelt containing small amount of MWCNTs. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 2021. 149: p. 106493. [CrossRef]

- Shang, S., et al., Enhancement of dielectric permittivity in carbon nanotube/polyvinylidene fluoride composites by constructing of segregated structure. Composites Communications, 2021. 25: p. 100745. [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.B., M.H. Ahmad, and M.R. Islam, Effect of MWCNT nanofiller on the dielectric performance of bio-inspired gelatin based nanocomposites. RSC Advances, 2022. 12(23): p. 14686-14697. [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, K., et al., Effects of carbon nanotubes aspect ratio on the qualitative and quantitative aspects of frequency response of electrical conductivity and dielectric permittivity in the carbon nanotube/polymer composites. Carbon, 2013. 54: p. 105-112. [CrossRef]

- Laxmayyaguddi, Y., et al., Modified Thermal, Dielectric, and Electrical Conductivity of PVDF-HFP/LiClO4 Polymer Electrolyte Films by 8 MeV Electron Beam Irradiation. ACS Omega, 2018. 3(10): p. 14188-14200.

- Sadiq, M., et al., Enhancement of Electrochemical Stability Window and Electrical Properties of CNT-Based PVA–PEG Polymer Blend Composites. ACS Omega, 2022. 7(44): p. 40116-40131. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., L. Zhang, and H. Wu, Dielectric Loss Mechanism in Electromagnetic Wave Absorbing Materials. Advanced Science, 2022. 9(10): p. 2105553. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A., et al., Nanofiller-Induced Enhancement of PVDF Electroactivity for Improved Sensing Performance. Advanced Sensor Research, 2023. 2(6): p. 2200080. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G., et al., Low percolation thresholds of electrical conductivity and rheology in poly(ethylene terephthalate) through the networks of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Polymer, 2006. 47(1): p. 480-488. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., et al., Coaxially aligned MWCNTs improve performance of electrospun P(VDF-TrFE)-based fibrous membrane applied in wearable piezoelectric nanogenerator. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2019. 178: p. 107447. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., et al., Wearable Piezoelectric Films Based on MWCNT-BaTiO3/PVDF Composites for Energy Harvesting, Sensing, and Localization. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2023. 6(13): p. 11955-11965.

- Bhadwal, N., R. Ben Mrad, and K. Behdinan Review of Piezoelectric Properties and Power Output of PVDF and Copolymer-Based Piezoelectric Nanogenerators. Nanomaterials, 2023. 13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., et al., Enhancing piezoelectric properties of PVDF-HFP composite nanofibers with cellulose nanocrystals. Materials Today Communications, 2024. 39: p. 108872. [CrossRef]

- Sharafkhani, S. and M. Kokabi, Enhanced sensing performance of polyvinylidene fluoride nanofibers containing preferred oriented carbon nanotubes. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials, 2022. 5(4): p. 3081-3093. [CrossRef]

| P(VDF-HFP) Samples |

Average Pore Size( μm) |

Porosity(%) |

Surface Roughness(nm) |

| Pure P(VDF-HFP) | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 7.047 | 78.33 |

| 0.25%MWCNTs | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 14.421 | 89.82 |

| 0.50%MWCNTs | 1.25 ± 0.12 | 24.297 | 118.40 |

| 0.75% MWCNTs | 1.64 ± 0.12 | 34.588 | 129.73 |

| 1.00% MWCNTs | 1.85 ± 0.09 | 39.126 | 137.34 |

| P(VDF-HFP) samples | d-spacing [Å] | FWHM Total [rad] | Crystalline size (nm) | (%) | (%) |

*FEA (%) |

(%) |

(%) |

| Pure | 4.42837 | 0. 6652 | 2.12 | 50.04 | 46.71 | 41.5 | 39.09 | 14.21 |

| 0.25%MWCNTs | 4.43478 | 0.4605 | 3.06 | 53.62 | 40.32 | 45.5 | 35.07 | 24.60 |

| 0.50%MWCNTs | 4.43227 | 0.4093 | 3.67 | 53.65 | 39.12 | 47.0 | 34.46 | 26.42 |

| 0.75% MWCNTs | 4.43581 | 0.3838 | 3.44 | 53.82 | 36.21 | 53.7 | 32.36 | 31.44 |

| 1.00% MWCNTs | 4.4401 | 0.3070 | 4.59 | 54.83 | 29.16 | 63.0 | 29.75 | 41.08 |

| P(VDF-HFP) samples | First thermal decomposition temperature | Mass loss | Second thermal decomposition temperature | Mass loss | Third thermal decomposition temperature | Mass loss | Residue Content |

| Pure | 51.72 | 0.79% | 462.15 | 76.45% | 559.6 | 13.22% | 9.54% |

| 0.25M | 52.31 | 0.74% | 463.98 | 76.01% | 560.41 | 13.25% | 10.00% |

| 0.50M | 52.68 | 0.69% | 464.2 | 72.54% | 571.31 | 13.41% | 13.36% |

| 0.75M | 57.1 | 0.90% | 464.75 | 72.19% | 577.66 | 13.18% | 13.73% |

| 1.00M | 58.66 | 0.85% | 468.03 | 72.01% | 574.04 | 12.15% | 15.98% |

| P(VDF-HFP) sample | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) | Young’s modulus (MPa) |

| Pure | 14.56 | 92.11 | 1.93 |

| 0.25M | 18.9 | 53.95 | 7.33 |

| 0.50M | 20.54 | 47.94 | 8.09 |

| 0.75M | 23.01 | 24.50 | 9.06 |

| 1.00M | 45.13 | 21.44 | 17.76 |

| Applied force (N) |

Sensor response at 1 Hz |

P(VDF-HFP) sample | ||||

| Pure | 0.25M | 0.50M | 0.75M | 1.00M | ||

| 1.074 N | Vp-p (V) | 6.80 | 7.38 | 9.90 | 14.12 | 12.26 |

| V max (V) | 3.40 | 3.69 | 4.95 | 7.06 | 6.08 | |

| V max/1.074 (V/N) | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.38 | |

| 3.232 N | Vp-p (V) | 8.20 | 10.7 | 12.76 | 18.2 | 14.72 |

| V max (V) | 4.10 | 5.35 | 6.38 | 9.10 | 7.36 | |

| V max/3.232 (V/N) | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.46 | |

| 6.199 N | Vp-p (V) | 12.72 | 14.62 | 18.58 | 22.24 | 19.22 |

| V max (V) | 6.36 | 7.31 | 9.29 | 11.12 | 9.61 | |

| V max/6.199 (V/N) | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.60 | |

| 9.522 N | Vp-p (V) | 16.34 | 18.66 | 21.72 | 26.58 | 23.34 |

| V max (V) | 8.17 | 9.33 | 10.86 | 13.29 | 11.67 | |

| V max/9.522 (V/N) | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.72 | |

| 16.145 N | Vp-p (V) | 21.38 | 24.64 | 27.76 | 33.16 | 30.22 |

| V max (V) | 10.69 | 12.32 | 13.88 | 16.58 | 15.11 | |

| Vmax/16.145 (V/N) | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 1.03 | 0.94 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).