4.2.1. Dispersion-strengthened

Dispersion-strengthened (DS) composites enhance mechanical strength and thermal stability by uniformly distributing fine, stable particles within a metal, ceramic, or polymer matrix. These particles are typically small, non-reactive, and stable under processing conditions, commonly made of oxides, carbides, or other refractory materials. Instead of chemically bonding with the matrix, the particles enhance the strength of the material by physically blocking the movement of dislocations—defects within the crystal structure that, when mobile, can reduce the material's strength under stress.

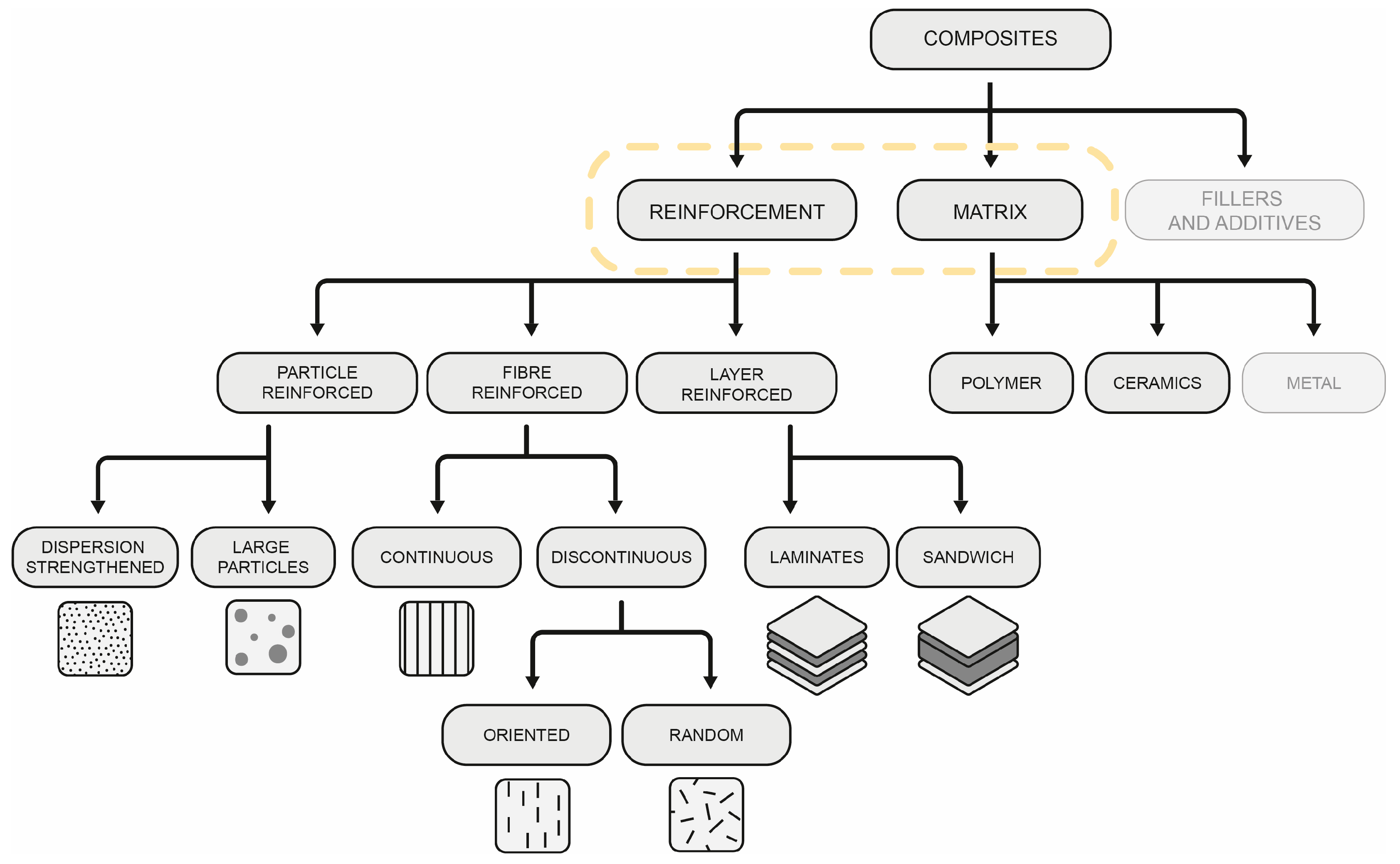

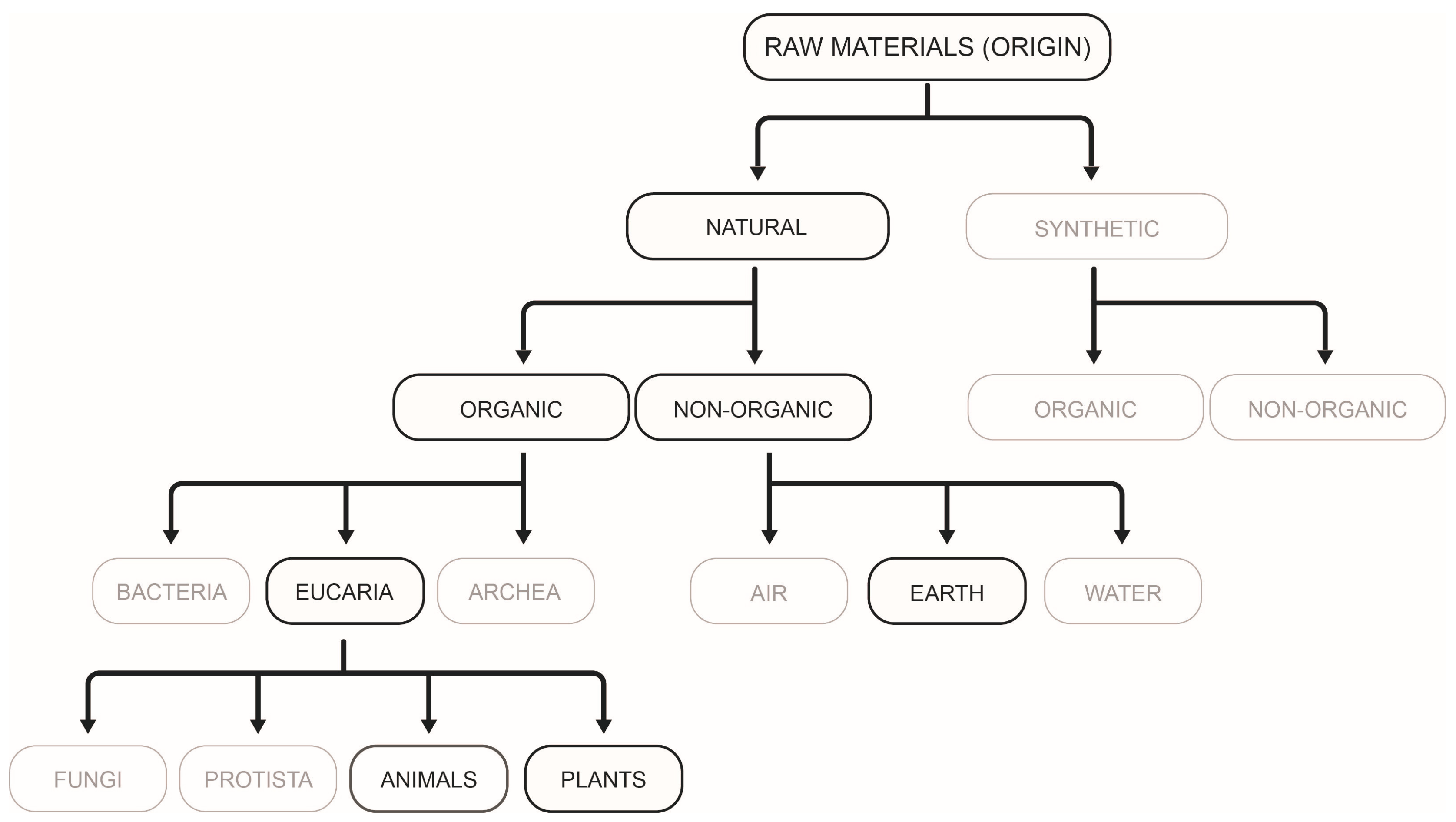

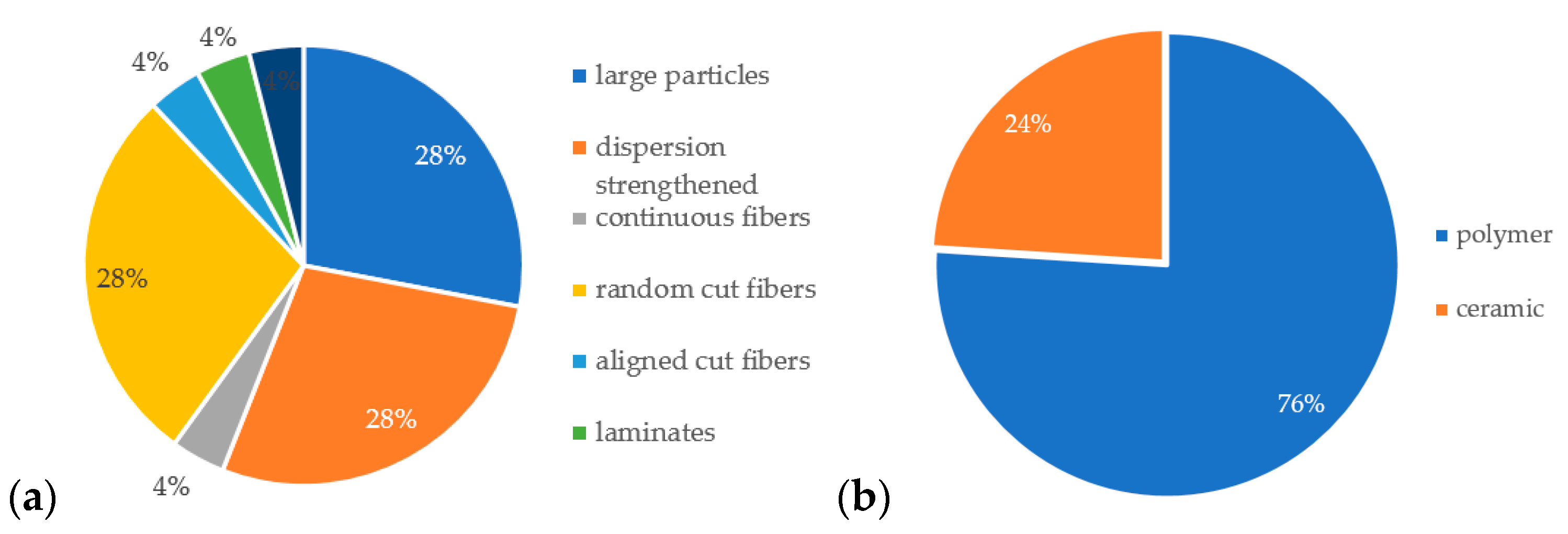

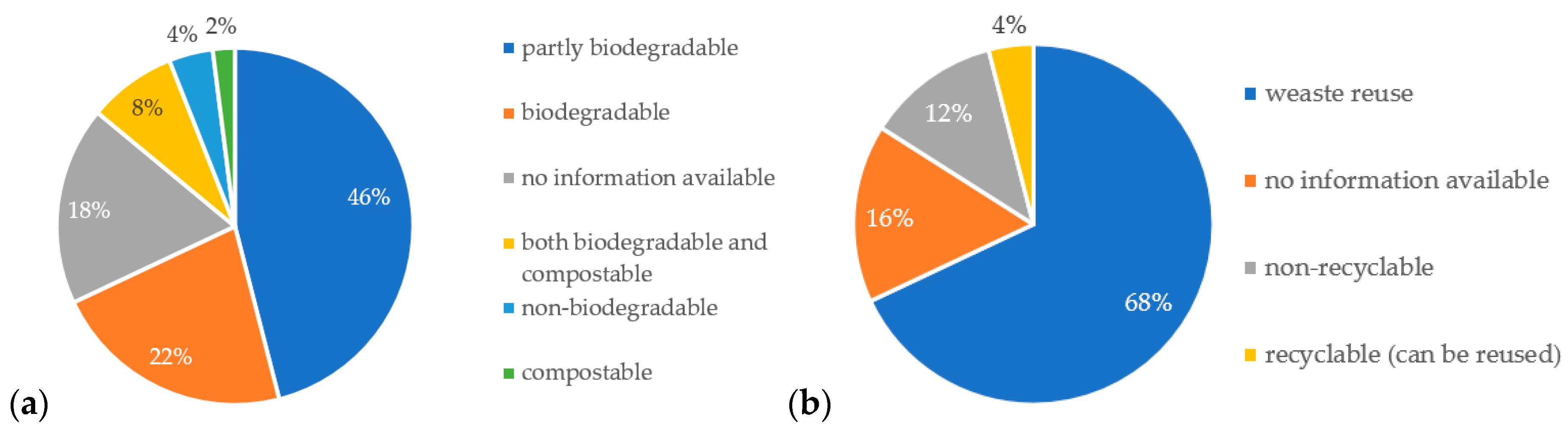

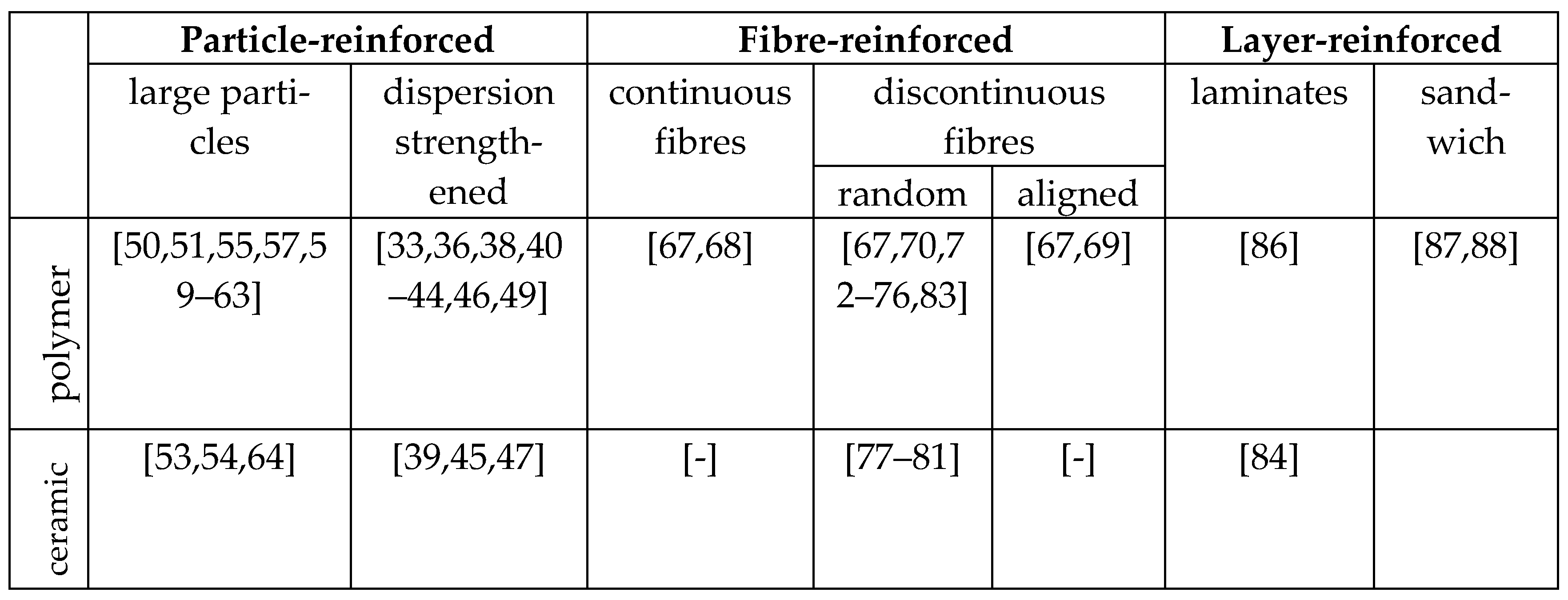

Figure 5.

Hierarchy of Composite Materials: An overview of the structural classification of composites, highlighting reinforcement types (particle, fibre, and layer) and their subdivisions, as well as the matrix materials that bind them.

Figure 5.

Hierarchy of Composite Materials: An overview of the structural classification of composites, highlighting reinforcement types (particle, fibre, and layer) and their subdivisions, as well as the matrix materials that bind them.

D-S composites are characterised by the inclusion of fine particles (microparticles), typically smaller than 0.1 mm (100 μm). These particles are often present as dust, ashes, powders, granules, or very fine fibres. Dust particles usually measure less than 100 μm in diameter and can naturally occur or result from mechanical or environmental processes. Ash particles, often a byproduct of combustion processes, are typically finer than powders and range from sub-micron sizes up to a few millimetres. Powders generally exhibit a broad particle size distribution, often ranging from approximately 1 μm to several millimetres, and are typically produced through artificial processing or grinding.

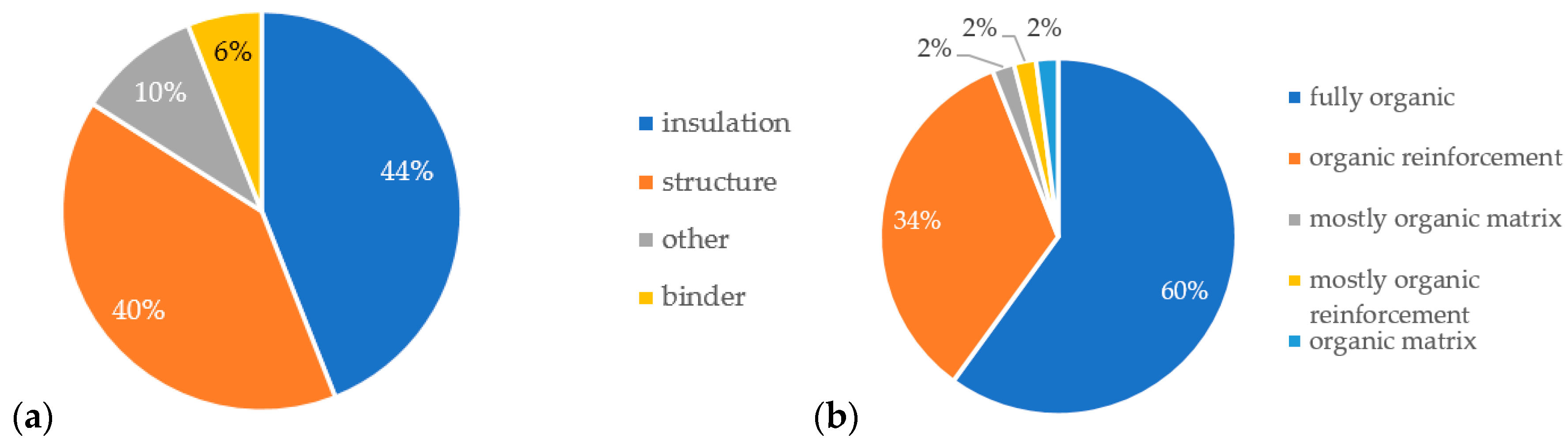

This fine dispersion within the matrix improves thermal/mechanical properties, including enhanced thermal stability and increased wear resistance. This section examines the applications of dispersion-strengthened composites in the construction industry, which are used for insulation, semi-structural elements, binders, and other functional components starting from fully organic solutions.

Open-cell foams with mostly organic matrices were presented by Kurańska et al. Natural oils from watermelon, cherry, black currant, grape, and pomegranate seeds were used to synthesise biopolyols through a transesterification reaction. Unlike conventional petroleum-based polyols, biopolyols are derived from renewable materials to produce polyurethane foams. In the transesterification reaction, an ester group is exchanged with an alcohol group from another molecule. The resulting foams, with a cellular structure, showed insulation properties with thermal conductivity values of λ = 0.035–0.037 W/m·K [

35].

Bio-based epoxy resin was studied as a potential binder by Gavrilović-Grmuša et al., who used natural polyphenols lignin and tannic acids as wood adhesives. Tensile shear strength testing showed that lignin and tannic acid "can effectively replace amine hardeners in epoxy resins" [

36]. The material's mechanical properties and flame retardancy make it promising for wood products, though it has limitations in compatibility with synthetic adhesives and broader applications without further chemical modifications.

Mohan et al. investigated a hybrid panel made from cotton microdust, a byproduct of the yarn spinning industry, combined with coir pith, using low-melt epoxy resin as a matrix. Two types of panels, 6 mm and 10 mm thick, were created. It was found that "thermal resistance improved while strength decreased with increased coir pith" [

37]. These biodegradable panels exhibited thermal resistance

k values ranging from 0.11 to 0.29 K·m²/W (thermal conductivity λ = 0.02 to 0.09 W/m·K), outperforming commercial non-biodegradable synthetic panels of the same thickness used in housing.

Varamesh et al. developed a fully organic bio-based aerogel using an assembly technique that deposits "two oppositely charged bio-based materials, phytic acid and chitosan (20nm - 30 μm), onto a fully biobased aerogel system," incorporating interconnected networks of cellulose filaments. This material displayed an excellent peak heat release rate and superior thermal insulation properties, with a thermal conductivity λ below 0.0382 W/m·K [

38].

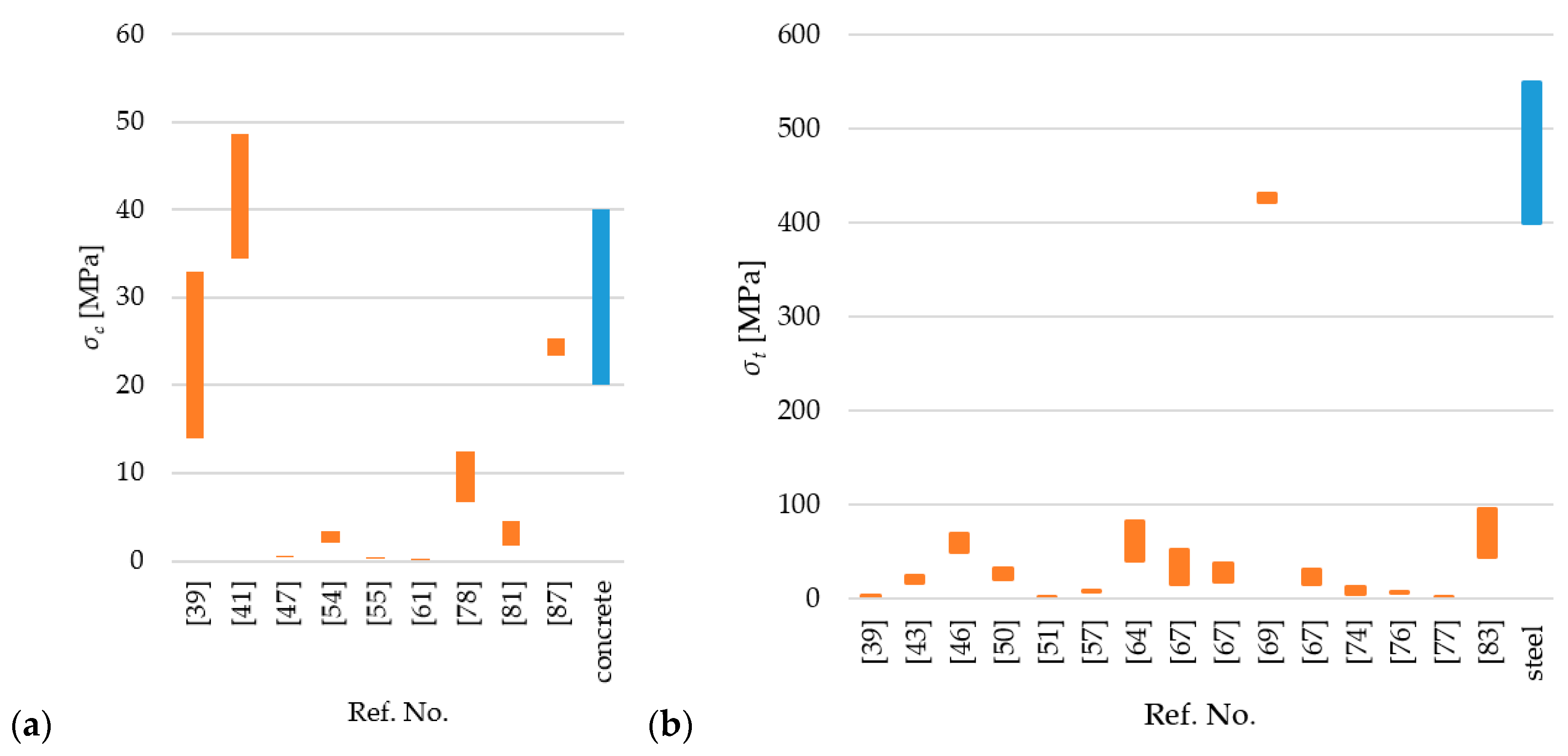

A material with organic reinforcement was reported by Hilal et al., who used nano-sunflower ash and nano-walnut shell as partial replacements for cement in self-compacting concrete. The resulting material has a lower density than traditional concrete due to its lightweight aggregate composition, which includes recycled plastic replacing part of the natural coarse aggregate. This concrete resembles typical self-compacting concrete but incorporates nano-particles, forming a fine, dense matrix with compressive strength ranging from approximately 15 to 30 MPa, depending on curing time [

39]. Additionally, lightweight concretes demonstrate enhanced thermal insulation properties.

In a study by Anwajler from Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, a 3D-printed, fully organic cellular insulation composite was developed using layers of natural fillers, such as soybean oil, glycerine, and wastepaper ash, with options for various colours, including transparent, black, grey, and metallic. Using a soybean-oil-based resin, the material was printed as a closed-cell foam based on a Voronoi pattern generated by a Rhino/Grasshopper script. Samples with a thickness of 100 mm demonstrated a thermal conductivity of

λ = 0.016 W/m·K [

40]. This material shows significant potential as a sustainable insulation solution, particularly in construction, where its customisable layering and composition make it adaptable to various thermal requirements.

Fully organic material was investigated by Ibraheem and Bdaiwi, who reinforced unsaturated polyester resin with Sidr leaves powder. Sidr is a hardy tree from the

Ziziphus genus, native to arid regions in the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia. In the experiment, Sidr powder particles were added at concentrations ranging from 5% to 25%. Small samples were produced using hand-lay moulding procedures and tested for mechanical properties such as durability, compression, and impact resistance. At a 25% fraction, the thermal conductivity was

λ = 0.101 W/m·K [

41].

Cigarruista Solís et al. introduced a bio-thermal insulation material from ground rice husk powder combined with rice flour. The mixture was formed into panels using a metal mould and dried at high temperatures to produce a compact, solid material. These rice husk-based insulation panels demonstrated thermal conductivity

λ of 0.073 W/m·K, within the range of conventional thermal insulators. This sustainable solution offers thermal performance comparable to conventional insulators, leveraging a local resource to enhance thermal comfort while reducing environmental impact [

42].

Another promising non-load-bearing material for building applications was tested by Raja et al. This composite consists of an epoxy matrix reinforced with

Ipomoea carnea fibres mixed with bran particulates as a filler (fibre 0.238 mm, powder 158 μm).

Ipomoea carnea is a flowering plant in the

Convolvulaceae family, native to tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas. The combination yields a composite material with an earthy tone and a textured surface. The fabrication process involves a hand layup technique, with varying weight fractions of bran filler added to the epoxy matrix. Its antibacterial properties make it suitable for applications requiring hygienic surfaces, such as wall panels in kitchens, bathrooms, or healthcare facilities [

43].

Dispersion-strengthened composites show promise as load-bearing materials. Aguillón et al. described a composite made from a sorbitol glycidyl ether epoxy resin blend and brewer's spent grain (particles < 212 μm, ground at high speed and mixed), a byproduct of the beer industry [

44]. The final material, produced through thermopressing, yields a dense, wood-like product with a natural brown hue. It shows strong potential as an alternative to traditional fibreboards for furniture manufacturing and construction.

Bio-based materials reinforced with organic additives were studied by Wan et al., who demonstrated that rice husk (granules of 800 μm) could serve as "a legitimate and environmentally acceptable alternative in composite materials" [

45]. The team compared conventional plaster's thermal conductivity to plaster's with bio-based additives. Samples containing 20% paddy husk showed excellent insulating properties, with a thermal conductivity of

λ = 0.67 W/m·K.

Sergi et al. developed a fully organic material for non-structural applications, such as interior panelling and decorative elements [

46]. This material consists of polylactic acid (PLA) reinforced with linoleum waste dust (860 μm), which contains wood flour, cork, and jute fibres. PLA is a biodegradable, bio-based plastic derived from renewable sources like corn starch or sugarcane. The material's moderate tensile strength and improved flexural stiffness make it suitable for lightweight furniture, decorative partitions, and wall panels.

A non-organic material—vitreous foam—with organic reinforcement is reported by Fernandes et al. This foam is produced at 750–850°C temperatures, using glass granules (12.5 mm) with sugarcane bagasse ash as an additive. Sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA) is the fibrous residue left after extracting juice from sugarcane, and its ash is rich in silica.

(SiO₂). The resulting vitreous foam has uniformly distributed closed pores, making it suitable for construction applications "intended to replace natural aggregates in lightweight concrete" [

47], with a compressive strength ranging from 0.48 to 0.58 MPa. Low-density materials often correlate with lower thermal conductivity λ. Comparable materials, such as commercial glass foams with similar densities, typically have λ values in the range of 0.05–0.07 W/m·K [

48].

The team of Pop et al. presents a study on a sound insulation material made from cellulose pulp reinforced with beeswax, fir resin, and natural fillers like horsetail, rice flour, and fir needles. The material has a textured, natural appearance with subtle colour variations depending on the filler used. Eight formulations were developed, and their resistance to thermal stress, oxidation temperature, and acoustic properties were evaluated. Sound absorption coefficients ranged from 0.15 to 0.78, with some formulations exceeding 0.5 in mid-frequencies, indicating good sound-dampening potential [

49]. Although heat stress tests were conducted, no thermal conductivity measurements were reported. However, similar materials typically exhibit λ values in the range of approximately 0.05–0.08 W/m·K [

48]. See

Table 2, which summarizes the data on dispersion-strengthened bio-composites.

Table 2.

Summary of properties and sustainability characteristics of dispersion-strengthened composites, including biodegradability, recyclability, and key mechanical and thermal metrics.

Table 2.

Summary of properties and sustainability characteristics of dispersion-strengthened composites, including biodegradability, recyclability, and key mechanical and thermal metrics.

| Ref. |

Authors |

Engineering material |

BP |

B/C |

R |

Metric [unit] |

v1 |

v2 |

| [35] |

Kurańska et al. |

Bio-based open-cell spray polyurethane foams |

I |

PB |

WR |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.035 |

0.043 |

| [36] |

Gavrilović-Grmuša et al. |

Bio-epoxy resins and wood composites |

B |

B |

WR |

τt [MPa] |

5.64 |

10.87 |

| [37] |

Mohan et al. |

Natural fibre-reinforced composite |

I |

PB |

WR |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.02 |

0.09 |

| [38] |

Varamesh et al. |

Biobased aerogel |

I |

B |

- |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.036 |

0.038 |

| [39] |

Hilal et al. |

Lightweight self-compacting concrete |

S |

- |

WR |

σt [MPa] |

1.1 |

3.0 |

|

σc [MPa] |

14.0 |

33.0 |

|

σf [MPa] |

1.88 |

5.2 |

| [40] |

Anwajler |

Natural fibre-reinforced insulating materials |

I |

PB |

WR |

LOI [%] |

56.2 |

63.1 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.016 |

~ |

| [41] |

Ibraheem and Bdaiwi |

SLP-reinforced unsaturated polyester composite |

S |

- |

WR |

σc [MPa] |

~34.5 |

48.7 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.101 |

0.190 |

| [42] |

Cigarruista Solís et al. |

Rice husk fibre insulation panels |

I |

PB |

WR |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.073 |

- |

| [43] |

Raja et al. |

Natural fibre-reinforcedcomposite |

O |

- |

WR |

σt [MPa] |

16.42 |

24.97 |

|

σf [MPa] |

16.98 |

27.36 |

| [44] |

Aguillón et al. |

Fibreboards |

S |

B |

WR |

σf [MPa] |

33.3 |

51.5 |

| [45] |

Wan et al. |

Plaster composites enhanced with paddy husk |

I |

- |

WR |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.67 |

0.83 |

| [46] |

Sergi et al. |

PLA-linoleum composite |

O |

PB |

WR |

σt [MPa] |

49 |

69 |

|

σf [MPa] |

75 |

98 |

| [47] |

Fernandes et al. |

Glass foam |

O |

- |

WR |

σc [MPa] |

0.48 |

0.58 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.05* |

0.07* |

| [49] |

Pop et al. |

Insulation panels |

I |

C |

WR |

SAC α |

0.15 |

0.78 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.05* |

0.08* |

4.2.2. Large-particle reinforced

Four materials with a particle size of 0.1-1 mm are identified in this review. Fayzullin et al. report a composite of polypropylene combined with natural fillers such as wood flour, rice husk (abbreviated as RHS), and sunflower husk, which have undergone enzymatic modification. This modification enhances the mechanical properties of the composite, resulting in improved filler-matrix bonding and yielding increased tensile strength, flexibility, and impact resistance. As noted in their study, "surface modification of natural fillers improves mechanical properties" [

50]. Additionally, tensile strength increases by 10% and viscosity by 12% with the inclusion of wood and sunflower fillers. This composite demonstrates a fine, dispersed structure essentially free from visible defects such as cracks or agglomerates.

Jamal et al. introduce a recycled polyethene material with RHS designed for building partition applications. Their research focuses on developing a "green polymer composite using natural resource materials (…) which holds potential applications in Malaysia" [

51]. Various ratios of rice husk fibre (RHF) were blended with recycled polyethene (RPE) to create RHF/RPE composites, with an optimal composition for partition applications identified at 0.4 wt./wt.% RHF/RPE. Please note that "wt./wt.%" (weight/weight per cent) is a common way of expressing the proportion of one material in a composite relative to the total weight of the mixture.

Grzybek et al. present a composite derived from wood particles (pine sawdust) impregnated with ethyl palmitate (from epoxidised linseed oil) and combined with fire retardants like boric acid, recycled paper, or clay. This material is designed for wall panel applications and has a compact structure and smooth surface. With phase change material (PCM) properties, it is intended for building applications requiring thermal energy storage and enhanced fire safety. The results indicate that fire retardants did not interfere with the preparation process, and the panels were successfully manufactured. The composite containing BPCM "demonstrated its capacity to absorb and release thermal energy, with an average latent heat of 50 J/g" [

52].

Finally, using limestone-based binders, Bonifacio and Archbold explore a composite comprising RHS from oats and rice. Their study innovatively assesses how surface treatments on husks influence the mechanical performance of composites. They conclude that coating oat husks—particularly with linseed oil—effectively "delays particle degradation and improves mechanical strength compared to untreated particles" [

53].

Particles sized 1–2 mm are used across three materials, each with varied application potential. Buda and Pucinotti's team presents a preliminary study that is part of a broader research initiative which aims to "design an innovative fibre-reinforced plaster using natural, sustainable, and locally produced materials" [

54]. The analysed plaster combines natural hydraulic lime with granulated cork, resulting in a distinctive light colour and coarse texture due to the cork granules. Two variants containing 15% and 30% cork by volume were tested. The latter exhibited a reduction in compressive strength of about 42% compared to standard mortars. Despite this reduction, the material offers visible opportunities for application due to its enhanced thermal insulation properties with λ = 0.39-0.44 [W/m·K].

The team led by Dymek et al. also uses cork aggregate, this time with eco-friendly porous polyurethane bio-composites, where post-consumer cooking oil serves as the matrix [

55]. This composite has a cellular structure with cork granules distributed throughout the polyurethane matrix, and its appearance varies slightly depending on the cork content and the type of polyol used. Its ability to efficiently absorb and dissipate impact energy makes it ideal for low-impact applications, such as protective padding or lightweight energy-absorbing layers. It may also be used as an insulating material, for which

λ is likely to fall between 0.04–0.07 W/m·K based on [

56]

Sergi et al.'s team employed cork as a reinforcement in composite material for deck board production. While wood is a sustainable option, concerns about forest depletion have significantly impacted its use. In this context, agglomerated cork presents a promising alternative. Their process involves converting the cork's "cellular structure into a consolidated one through hot compression" [

57]. High temperatures expose the cork cell walls to weld, developing adhesive properties. The resulting material demonstrates thermal insulating properties of

λ = 0.24–0.68 W/m·K and improved mechanical properties: bending stiffness that is 40.9% higher and bending strength 107.1% higher than local code requirements.

Particles between two and five millimetres are incorporated into four materials, one intended for semi-structural applications and the other for insulation purposes. Krumins et al. introduce a novel concept for producing particle boards where petrochemical-based binders are partially replaced with bio-based carbohydrate adhesives. In this process, composite reinforcements—such as branches, needles, bark, and particles sourced from Latvian State Forests—are hot-pressed with the binder to form a board. Notably, conifer bark serves as both reinforcement and binder, revealing binding properties due to its resin content when processed under pressure and at elevated temperatures (140-160°C) [

58]. The highest strength was observed in plates with a particle size of 2.8 mm.

Bendaikha and Yaseri's team present a material described as a straw-based bio-insulation suitable for bioclimatic applications. This material is created by milling straw to an approximate fibre length of 2 mm, then combining it with Aloe Vera (30 wt%) and sodium bicarbonate (10 wt%) as a fire retardant, and finally coating it in vinyl glue [

59]. The mixture is moulded to insulate pipes in geothermal systems, with the resulting 2 cm thick straw-based material demonstrating favourable thermal insulation properties compared to conventional foam.

In their study, Mucsi et al. investigate five composite panels made from coconut coir and reed straw particles with methylene diphenyl diisocyanate as the binding agent. The thermal conductivity of these panels—comparable to that of similar natural insulation materials—ranged from 0.08 to 0.10 W/m·K [

60]. The panels are lightweight and fibrous, with a medium-density structure, and the combination of coconut and reed fibres provides both thermal insulation and moderate mechanical strength, making it suitable for interior and non-load-bearing insulation layers.

Finally, Glenn et al. report cellulose fibre foams as a viable alternative to plastic foams in the packaging industry. The material consists of cellulose fibre foam bound with starch and reinforced with paperboard elements like angles, cylinders, or grid structures to enhance strength. It has a lightweight, porous structure with customisable surface finishes that can be adapted to various building requirements. The thermal conductivity of all samples was relatively low, ranging from 0.039 to 0.049 W/m·K [

61].

In the 5–10 mm particle size sub-type, only one material is reported, as presented by Rodríguez et al. This study aimed to assess an insulation panel made from rice husk using a pulping method with the addition of sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The resulting material has a lightweight, fibrous structure with a porous texture that traps air, enhancing its insulating properties. Thermal conductivity values range from 0.037 to 0.042 W/m·K, with a high acoustic absorption coefficient greater than 0.7 across octave frequency bands between 125 Hz and 4 kHz [

62]. The raw pulp is moulded into panels of varying thicknesses, which can be adapted for numerous building applications.

Materials with particles larger than 10 mm are represented by two instances reported by the teams of Mohammed et al. and Kamalizad and Morshed. The first team evaluated particleboards made from three natural fibres—bagasse, kenaf bast fibres, and cotton stalk—bonded with bio-based adhesives, specifically casein and tannins. This process results in a natural, wood-like panel with a coarse texture due to the visible fibres embedded within the matrix. Boards with a thickness of 20 mm vary in density and appearance depending on the fibre type and adhesive used, with casein-based boards generally demonstrating higher mechanical performance than tannin-based boards. These materials suit interior applications, including furniture, wall panels, and thermal insulation. The thermal conductivity values were recorded at 0.082 W/m·K for bagasse particleboard, 0.056 W/m

2·K for cotton stalk particleboard, and 0.089 W/m·K for kenaf bast fibre particleboard [

63].

The second team, Kamalizad and Morshed, worked on a much larger scale, analysing compressed earth blocks (CEB) with a thickness of 120 mm. Since CEBs typically exhibit poor seismic performance, the team reinforced them with sand-coated common reeds. Their testing indicated that "the strength and lateral displacement of the reinforced specimen with four vertical reeds increased by 44% and 76%, respectively, compared to the non-reinforced ones" [

64]. CEBs combine affordability and sustainability due to low-energy production, the use of local materials, and minimal emissions, making them particularly suitable for residential and small commercial buildings in rural or developing areas. See

Table 3, which summarizes the data on large-particle reinforced bio-composites.

Table 3.

Summary of properties and sustainability characteristics of large particles-reinforced composites, including biodegradability, recyclability, and key mechanical and thermal metrics.

Table 3.

Summary of properties and sustainability characteristics of large particles-reinforced composites, including biodegradability, recyclability, and key mechanical and thermal metrics.

| Ref. |

Authors |

Engineering material |

BP |

B/C |

R |

Metric [unit] |

v1 |

v2 |

| [50] |

Fayzullin et al. |

Polypropylene-based composite with modified natural fillers |

S |

- |

WR |

σt [MPa] |

21.0 |

31.9 |

| [51] |

Jamal et al. |

Rice Husk Fibres and Recycled Polyethylene composite |

S |

- |

WR |

σt [MPa] |

0.52 |

0.6 |

|

σf [MPa] |

19.04 |

27.17 |

| [52] |

Grzybek et al. |

Pine Wood-based particleboard |

S |

- |

WR |

PHRR [kW/m2] |

347.8 |

547.7 |

| THR [MJ/m2] |

82.2 |

213.4 |

| MARHE [kW/m2] |

217.5 |

430.3 |

| [53] |

Bonifacio and Archbold |

Limestone-based composites with oat husks as bio-aggregates |

B |

B |

WR |

- |

- |

- |

| [54] |

Buda and Pucinotti |

Natural lime-cork mortar |

B |

B |

- |

σc [MPa] |

2.16 |

3.35 |

|

σf [MPa] |

2.34 |

3.87 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.39 |

0.446 |

| [55] |

Dymek et al. |

Cork–polyurethane-based foams |

O |

PB |

WR |

σc [MPa] |

0.283 |

0.344 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.04* |

0.07* |

| [57] |

Sergi et al. |

Consolidated Cork Planks |

S |

B |

- |

σt [MPa] |

7.98 |

9.27 |

|

σf [MPa] |

12.82 |

16.43 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.24 |

0.68 |

| [58] |

Krumins et al. |

Bio-based particleboard |

S |

PB |

WR |

σf [MPa] |

2.13 |

9.99 |

| [59] |

Bendaikha and Yaseri |

Straw-based thermal insulation material |

I |

PB |

WR |

Thermal gradient |

9o

|

- |

| [60] |

Mucsi et al. |

Lignocellulosic fibre composite |

I |

- |

WR |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.08 |

0.1 |

|

σf [MPa] |

2.41 |

6.33 |

| [61] |

Glenn et al. |

Insulative fibre foam |

I |

B C |

- |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.039 |

0.049 |

|

σf [MPa] |

0.038 |

0.460 |

|

σc [MPa] |

0.001 |

0.305 |

| [62] |

Rodríguez et al. |

Rice husk-based thermal insulation panels |

I |

PB |

WR |

λ [W/m·K] |

0.037 |

0.042 |

| NRC |

0.77 |

0.98 |

| [63] |

Mohammed et al. |

Bio-composite particleboards |

I |

B |

- |

σf [MPa] |

1.6 |

15.6 |

|

λ [W/m·K] |

0.050 |

0.089 |

| [64] |

Kamalizad and Morshed |

Compressed Earth Block |

S |

B C |

- |

σt [MPa] |

40.9 |

- |