Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

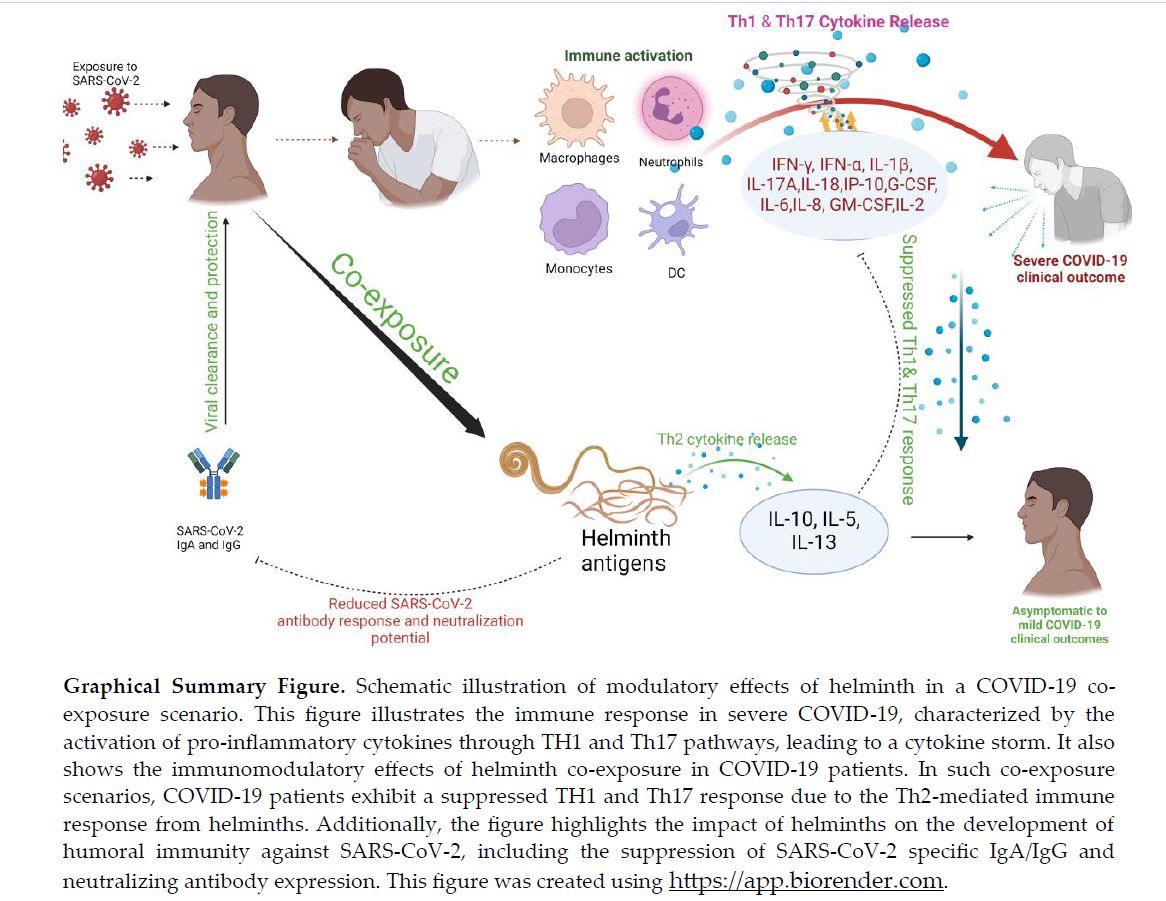

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Sample Collection, and Ethics

2.2. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 Specific IgA and IgG and Severity Classification

2.3. Quantification of Helminth-Specific IgG

2.4. Quantification of Neutralizing Antibody Levels

2.5. Quantification of Systemic Cytokine and Chemokine Expression

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

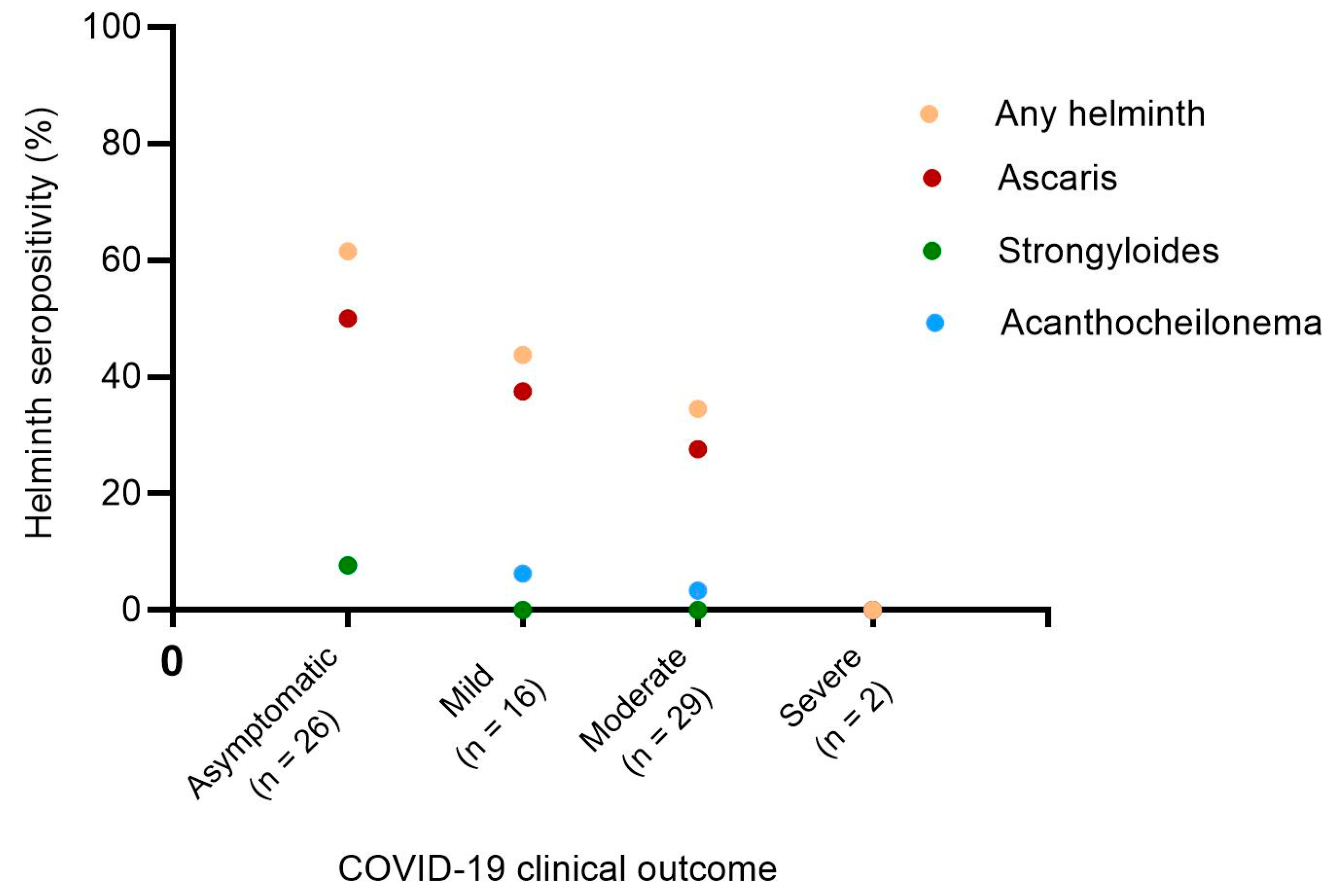

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Clinical outcome n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Examined n (%) |

Uninfected n = 31 |

Asymptomatic n = 26 |

Mild n = 16 |

Moderate n =29 |

Severe n = 2 |

|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 55 (52.9) | 17 (54.8) | 18 (69.2) | 6 (37.5) | 14 (48.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Female | 49 (47.1) | 14 (45.2) | 8 (30.8) | 10 (62.5) | 15 (51.7) | 2 (100.0) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 11-22 | 30 (28.8) | 14 (45.2) | 11 (42.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| 22-32 | 22 (21.2) | 7 (22.6) | 4 (15.4) | 6 (37.5) | 4 (13.8) | 1 (50.0) |

| 33-43 | 20 (19.2) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (26.9) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| 44-54 | 11 (10.6) | 5 (16.1) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (6.5) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥55 | 21 (20.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.8) | 6 (37.5) | 12 (41.4) | 1 (50.0) |

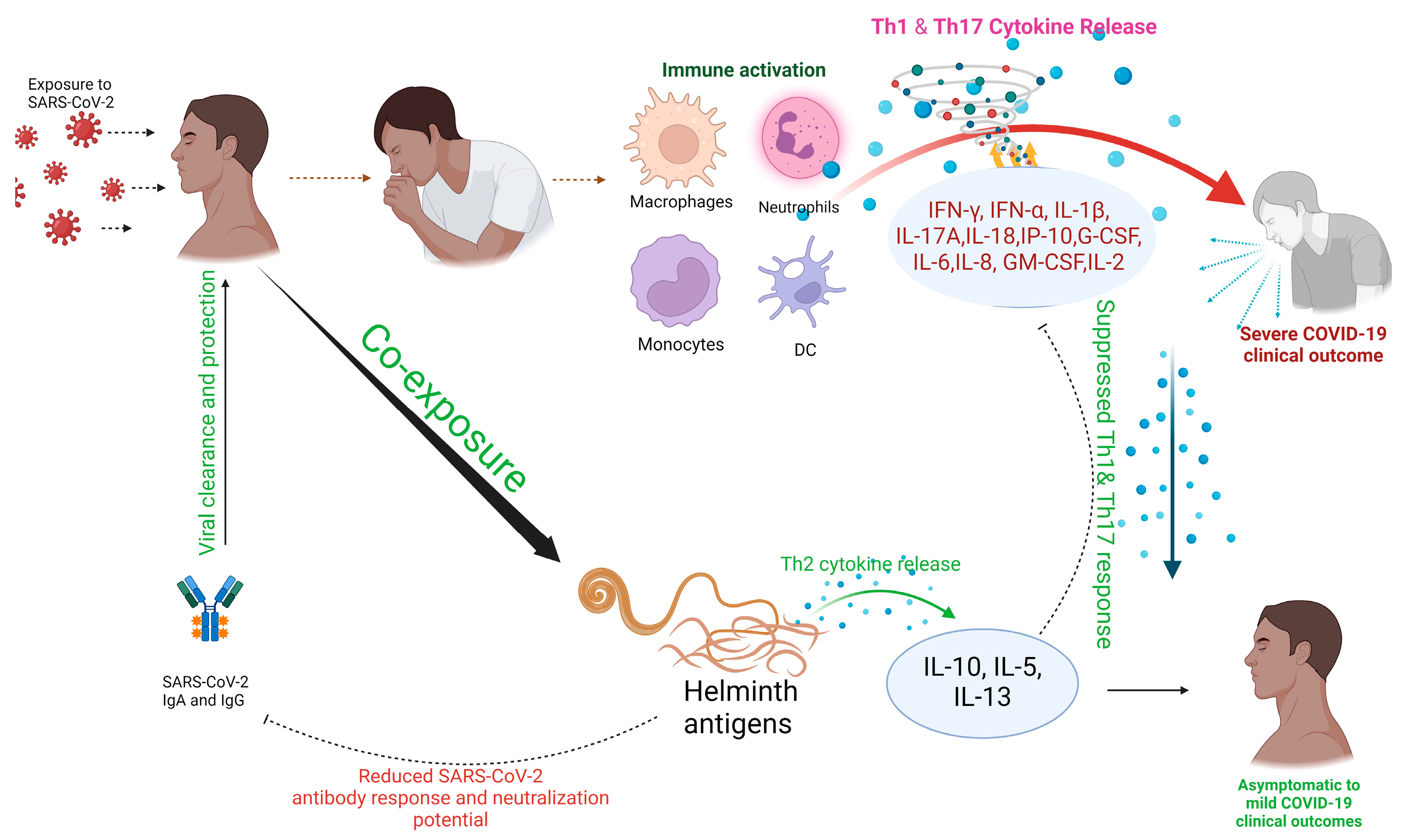

3.2. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 and Helminth Co-exposure Rates

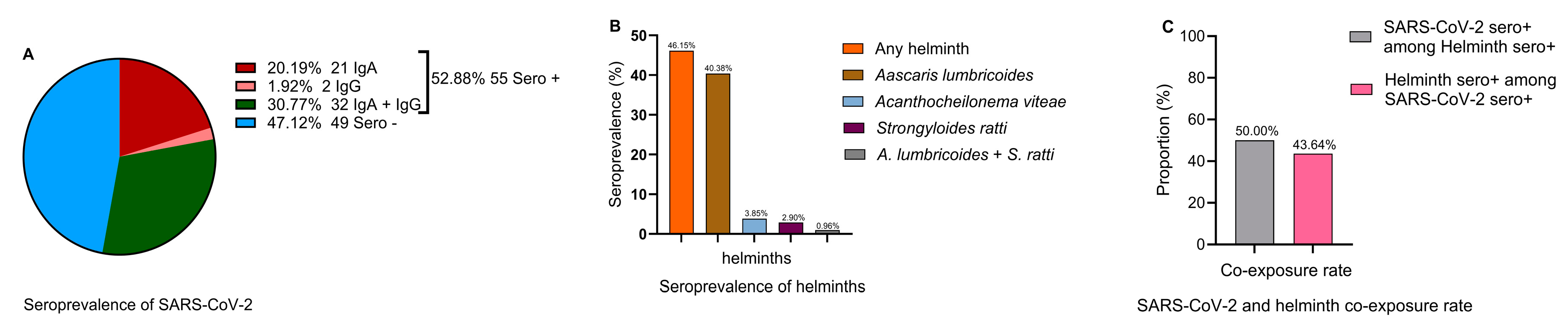

3.3. Helminth-exposed individuals exhibit asymptomatic COVID-19 Clinical outcomes

| Predictors | Estimate |

aOR |

Std. Error | Wald | df | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L B | U B | |||||||

| Age | 0.046 | 1.047 | 0.016 | 8.530 | 1 | 0.003 | 1.015 | 1.080 |

| Gender (Female) | -0.946 | 0.388 | 0.571 | 2.751 | 1 | 0.097 | 0.127 | 1.188 |

| A. lumbricoides Seroreactive (no) | 1.396 | 4.038 | 0.635 | 4.830 | 1 | 0.028 | 1.163 | 14.020 |

| A. viteae seroreactive (no) | 0.451 | 1.570 | 1.251 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.718 | 0.135 | 18.252 |

| Any Helminth (no) | 1.415 | 4.115 | 0.596 | 5.628 | 1 | 0.018 | 1.279 | 13.242 |

3.4. Helminth Seroprevalence Inversely Correlates with COVID-19 Severity

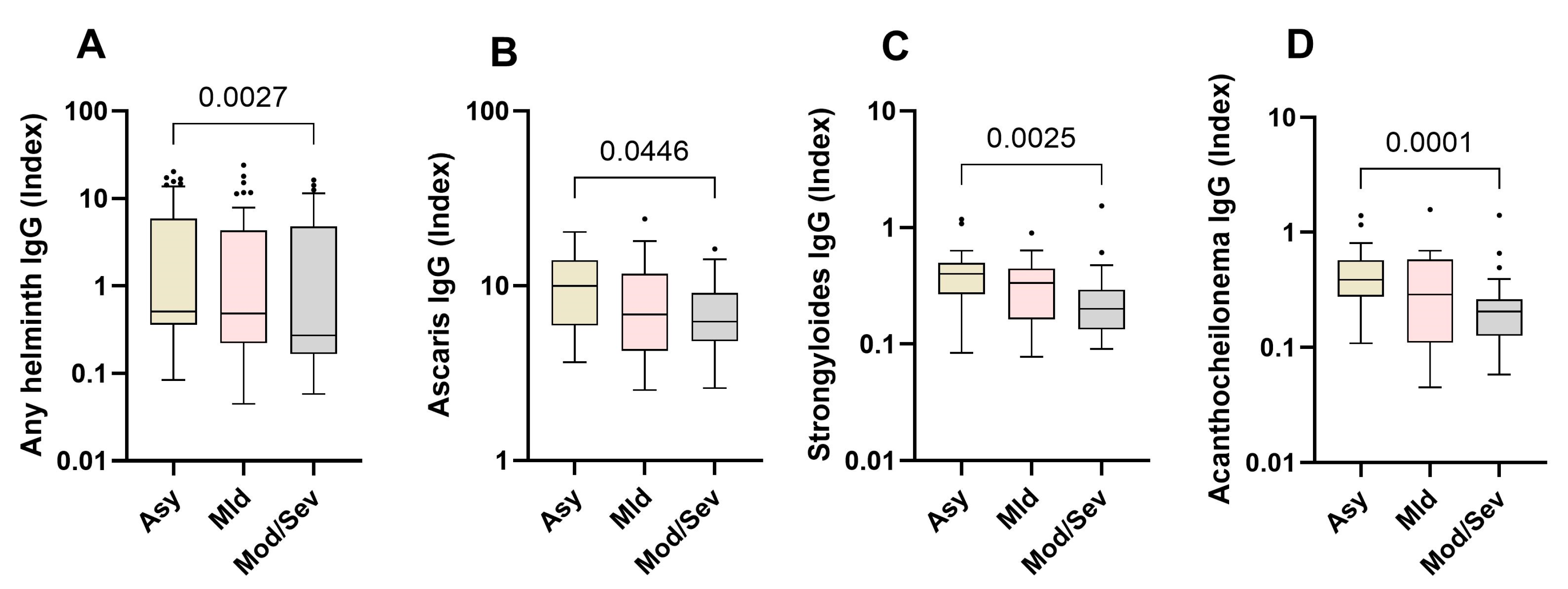

3.5. Elevated Helminth-Specific IgG Levels Correlate with Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection

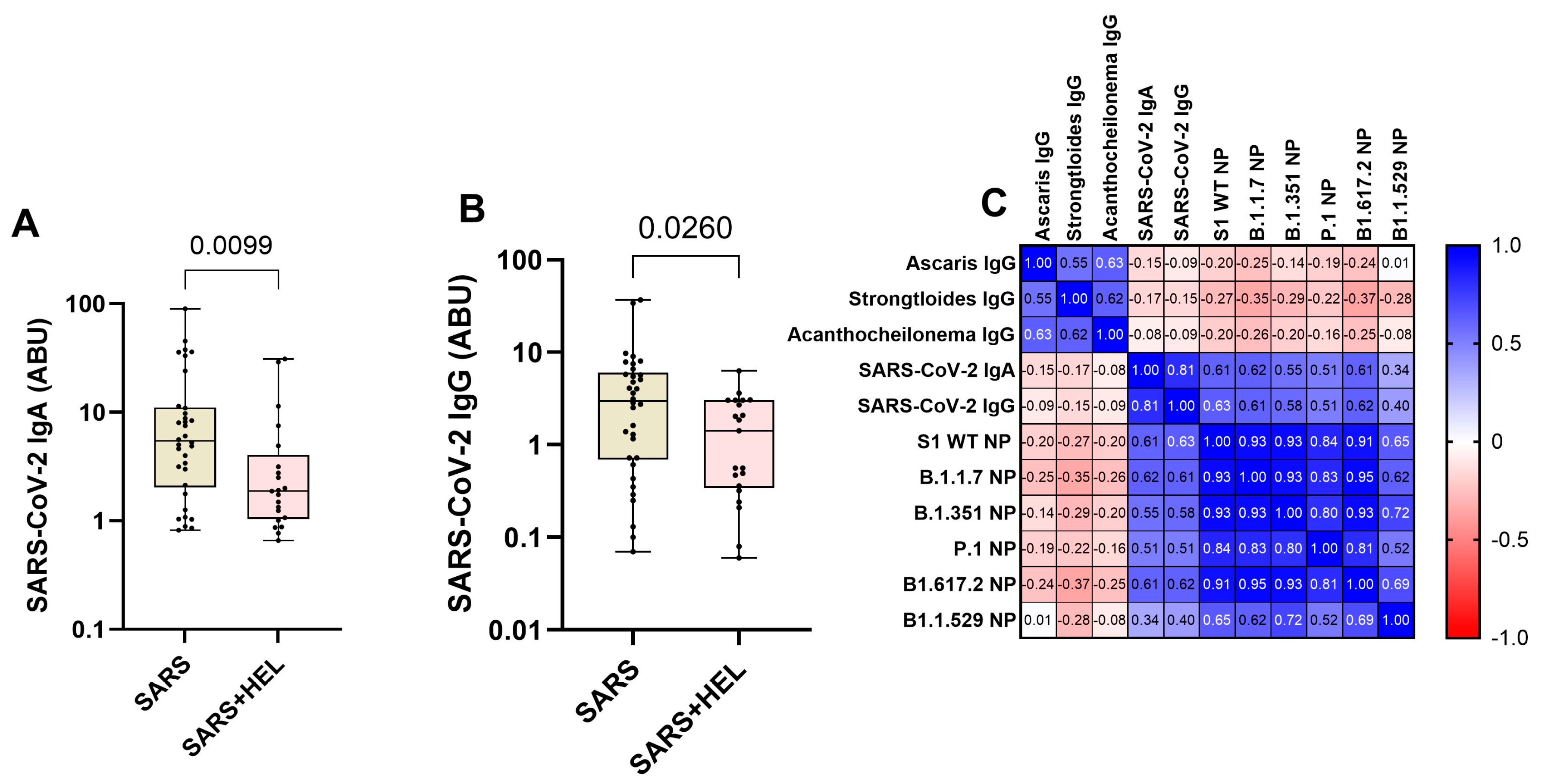

3.6. Low Expression of SARS-CoV-2- specific IgA/ IgG and Neutralization Potency in Helminth-co-exposed Individuals

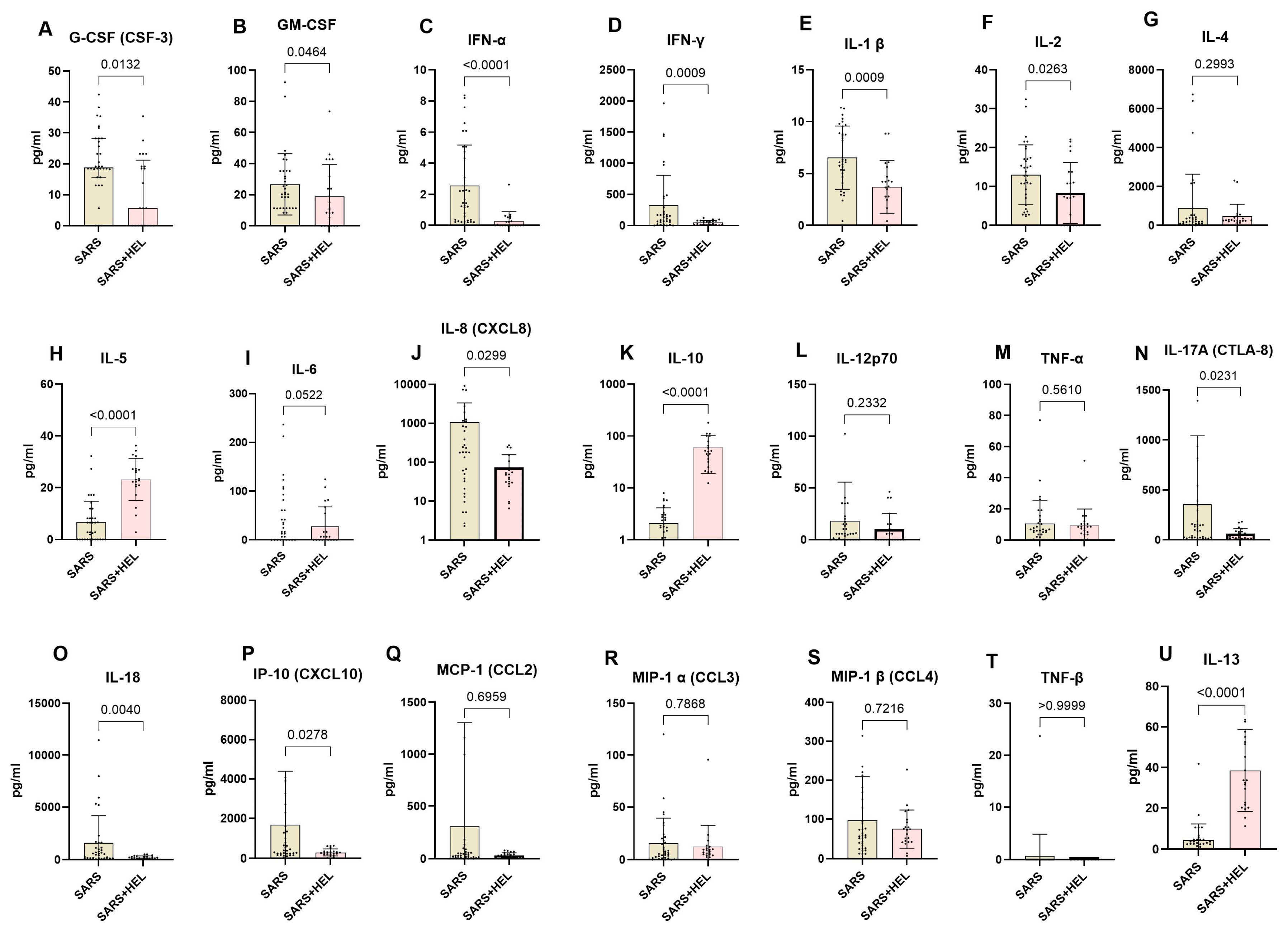

3.7. Lower Expression of Th1 and Th17 and Elevated Expression of Th2 Cytokines in Helminth Co-Exposed Individuals

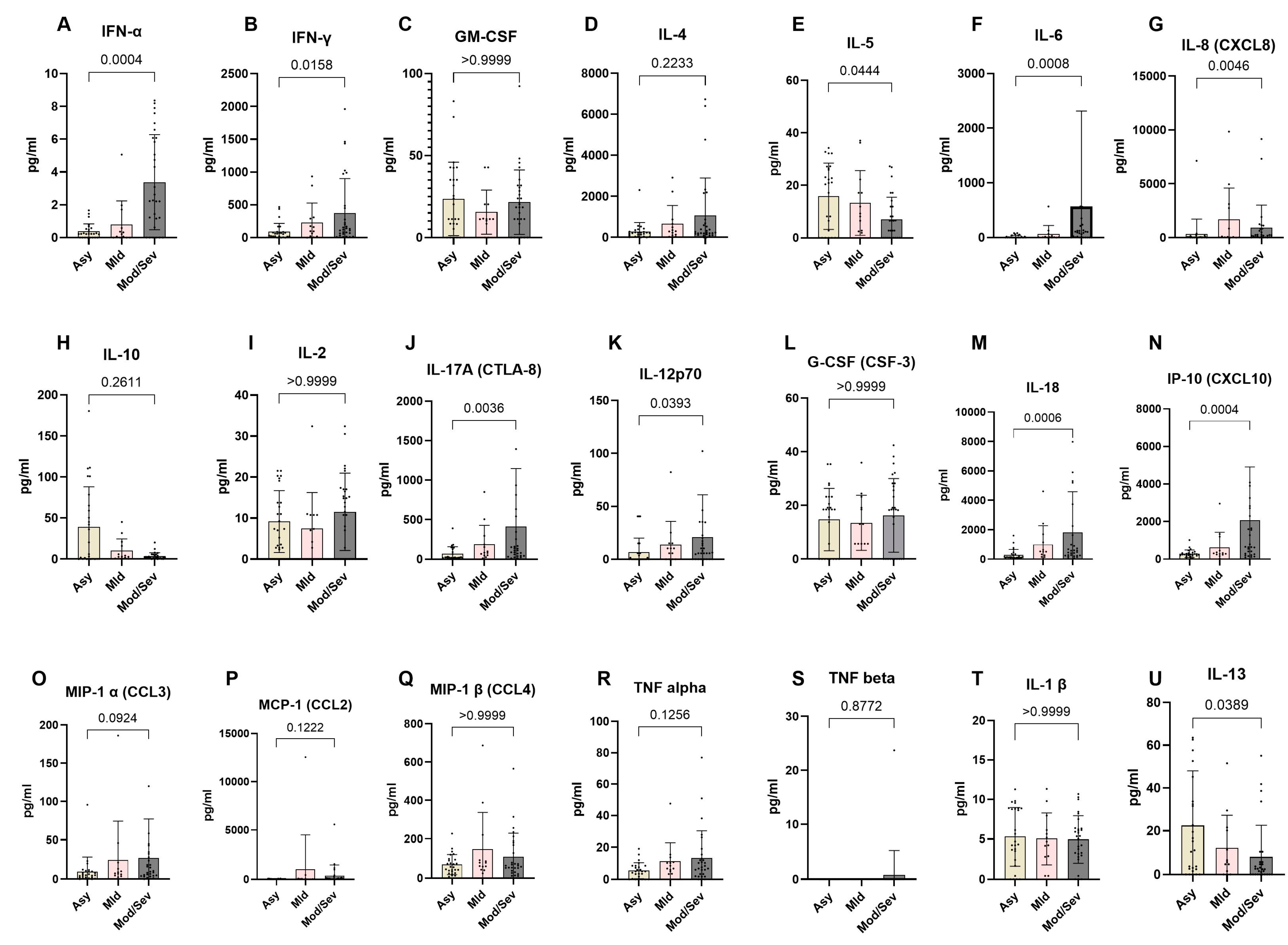

3.8. Reduced Expression of Th1 and Th17 Cytokines in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Exposed Individuals.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mishra, N.P.; Das, S.S.; Yadav, S.; Khan, W.; Afzal, M.; Alarifi, A.; kenawy, E.R.; Ansari, M.T.; Hasnain, M.S.; Nayak, A.K. Global Impacts of Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: Focus on Socio-Economic Consequences. Sensors International 2020, 1, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Kim, M.; Jalal, A.T.; Goldberg, J.E.; Acevedo Martinez, E.M.; Suarez Moscoso, N.P.; Rubio-Gomez, H.; Mayer, D.; Visbal, A.; Sareli, C.; et al. Distinct Clinical Presentations and Outcomes of Hospitalized Adults with the SARS-CoV-2 Infection Occurring during the Omicron Variant Surge. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Deaths | WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Marušić, J.; Hasković, E.; Mujezinović, A.; Đido, V. Correlation of Pre-Existing Comorbidities with Disease Severity in Individuals Infected with SARS-COV-2 Virus. BMC Public Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Has Africa Largely Evaded the COVID-19 Pandemic? | FSI. Available online: https://healthpolicy.fsi.stanford.edu/news/how-has-africa-largely-evaded-covid-19-pandemic-0 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Oleribe, O.O.; Suliman, A.A.A.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Corrah, T. Possible Reasons Why Sub-Saharan Africa Experienced a Less Severe COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020. J Multidiscip Healthc 2021, 14, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoli, A. Helminths and COVID-19 Co-Infections: A Neglected Critical Challenge. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2020, 3, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolday, D.; Gebrecherkos, T.; Arefaine, Z.G.; Kiros, Y.K.; Gebreegzabher, A.; Tasew, G.; Abdulkader, M.; Abraha, H.E.; Desta, A.A.; Hailu, A.; et al. Effect of Co-Infection with Intestinal Parasites on COVID-19 Severity: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, R.; Piedrafita, D.; Greenhill, A.; Mahanty, S. Will Helminth Co-Infection Modulate COVID-19 Severity in Endemic Regions? Nat Rev Immunol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Massacand, J.C.; Stettler, R.C.; Meier, R.; Humphreys, N.E.; Grencis, R.K.; Marsland, B.J.; Harris, N.L. Helminth Products Bypass the Need for TSLP in Th2 Immune Responses by Directly Modulating Dendritic Cell Function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 13968–13973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, R.M.; Yazdanbakhsh, M. Immune Regulation by Helminth Parasites: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Nature Reviews Immunology 2003 3:9 2003, 3, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, R.M.; Pearce, E.J.; Artis, D.; Yazdanbakhsh, M.; Wynn, T.A. Regulation of Pathogenesis and Immunity in Helminth Infections. In Proceedings of the Journal of Experimental Medicine; September 28 2009; Vol. 206; pp. 2059–2066. [Google Scholar]

- Maizels, R.M.; Smits, H.H.; McSorley, H.J. Modulation of Host Immunity by Helminths: The Expanding Repertoire of Parasite Effector Molecules. Immunity 2018, 49, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akelew, Y.; Andualem, H.; Ebrahim, E.; Atnaf, A.; Hailemichael, W. Immunomodulation of COVID-19 Severity by Helminth Co-Infection: Implications for COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy. Immun Inflamm Dis 2022, 10, e573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, P.; Janova, H.; White, J.P.; Reynoso, G.V.; Hickman, H.D.; Baldridge, M.T.; Urban, J.F.; Stappenbeck, T.S.; Thackray, L.B.; Diamond, M.S. Enteric Helminth Coinfection Enhances Host Susceptibility to Neurotropic Flaviviruses via a Tuft Cell-IL-4 Receptor Signaling Axis. Cell 2021, 184, 1214–1231.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjobimey, T.; Meyer, J.; Hennenfent, A.; Bara, A.J.; Lagnika, L.; Kocou, B.; Adjagba, M.; Laleye, A.; Hoerauf, A.; Parcina, M. Negative Association between Ascaris Lumbricoides Seropositivity and Covid-19 Severity: Insights from a Study in Benin. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, D.; Britton, S.; Aseffa, A.; Engers, H.; Akuffo, H. Poor Immunogenicity of BCG in Helminth Infected Population Is Associated with Increased in Vitro TGF-β Production. Vaccine 2008, 26, 3897–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, W.; Brunn, M.L.; Stetter, N.; Gagliani, N.; Muscate, F.; Stanelle-Bertram, S.; Gabriel, G.; Breloer, M. Helminth Infections Suppress the Efficacy of Vaccination against Seasonal Influenza. Cell Rep 2019, 29, 2243–2256.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgame, P.; Yap, G.S.; Gause, W.C. Effect of Helminth-Induced Immunity on Infections with Microbial Pathogens. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.M.; Mills, K.H.G.; Dalton, J.P. Fasciola Hepatica Cathepsin L Cysteine Proteinase Suppresses Bordetella Pertussis-Specific Interferon-Gamma Production in Vivo. Parasite Immunol 2001, 23, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjobimey, T.; Meyer, J.; Terkeš, V.; Parcina, M.; Hoerauf, A. Helminth Antigens Differentially Modulate the Activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T Lymphocytes of Convalescent COVID-19 Patients in Vitro. BMC Med 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Pati, S.; Sahoo, P.K. Investigating Immunological Interaction between Lymphatic Filariasis and COVID-19 Infection: A Preliminary Evidence. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021, 17, 5150–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Britton, S.; Kassu, A.; Akuffo, H. Chronic Helminth Infections May Negatively Influence Immunity against Tuberculosis and Other Diseases of Public Health Importance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2007, 5, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Akuffo, H.; Pawlowski, A.; Haile, M.; Schön, T.; Britton, S. Schistosoma Mansoni Infection Reduces the Protective Efficacy of BCG Vaccination against Virulent Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Vaccine 2005, 23, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, W. qi; Lei, J. hui; Guan, F.; Li, M. jun; Song, W. jian; Li, Y. long; Wang, T. Chronic Schistosoma Japonicum Infection Reduces Immune Response to Vaccine against Hepatitis B in Mice. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, F.; Hou, X.; Nie, G.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.Q.; Li, Y.L.; Lei, J.H. Effect of Trichinella Spiralis Infection on the Immune Response to HBV Vaccine in a Mouse Model. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2013, 10, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apiwattanakul, N.; Thomas, P.G.; Iverson, A.R.; McCullers, J.A. Chronic Helminth Infections Impair Pneumococcal Vaccine Responses. Vaccine 2014, 32, 5405–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riner, D.K.; Ndombi, E.M.; Carter, J.M.; Omondi, A.; Kittur, N.; Kavere, E.; Korir, H.K.; Flaherty, B.; Karanja, D.; Colley, D.G. Schistosoma Mansoni Infection Can Jeopardize the Duration of Protective Levels of Antibody Responses to Immunizations against Hepatitis B and Tetanus Toxoid. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Larrotta, C.; Arango, E.M.; Carmona-Fonseca, J. Negative Immunomodulation by Parasitic Infections in the Human Response to Vaccines. J Infect Dev Ctries 2018, 12, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gent, V.; Waihenya, R.; Kamau, L.; Nyakundi, R.; Ambala, P.; Kariuki, T.; Ochola, L. An Investigation into the Role of Chronic Schistosoma Mansoni Infection on Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Induced Protective Responses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweyongyere, R.; Nassanga, B.R.; Muhwezi, A.; Odongo, M.; Lule, S.A.; Nsubuga, R.N.; Webb, E.L.; Cose, S.C.; Elliott, A.M. Effect of Schistosoma Mansoni Infection and Its Treatment on Antibody Responses to Measles Catch-up Immunisation in Pre-School Children: A Randomised Trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natukunda, A.; Zirimenya, L.; Nassuuna, J.; Nkurunungi, G.; Cose, S.; Elliott, A.M.; Webb, E.L. The Effect of Helminth Infection on Vaccine Responses in Humans and Animal Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasite Immunol 2022, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Diamond, M.S.; Thackray, L.B. Helminth–Virus Interactions: Determinants of Coinfection Outcomes. Gut Microbes 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, R.S.; Piedrafita, D.; Greenhill, A.; Mahanty, S. Will Helminth Co-Infection Modulate COVID-19 Severity in Endemic Regions? Nature Reviews Immunology 2020 20:6 2020, 20, 342–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, R.; Pierce, D.; Giacomin, P.; Loukas, A.; Bourke, P.; McDermott, R. Helminth Coinfection and COVID-19: An Alternate Hypothesis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, e0008628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gause, W.C.; Wynn, T.A.; Allen, J.E. Type 2 Immunity and Wound Healing: Evolutionary Refinement of Adaptive Immunity by Helminths. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoguina, J.S.; Weyand, E.; Larbi, J.; Hoerauf, A. T Regulatory-1 Cells Induce IgG4 Production by B Cells: Role of IL-10. The Journal of Immunology 2005, 174, 4718–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjobimey, T.; Meyer, J.; Sollberg, L.; Bawolt, M.; Berens, C.; Kovačević, P.; Trudić, A.; Parcina, M.; Hoerauf, A. Comparison of IgA, IgG, and Neutralizing Antibody Responses Following Immunization With Moderna, BioNTech, AstraZeneca, Sputnik-V, Johnson and Johnson, and Sinopharm’s COVID-19 Vaccines. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 917905–917905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackah, E.B.; Owusu, M.; Sackey, B.; Boamah, J.K.; Kamasah, J.S.; Aduboffour, A.A.; Akortia, D.; Nkrumah, G.; Amaniampong, A.; Klevor, N.; et al. Haematological Profile and ACE2 Levels of COVID-19 Patients in a Metropolis in Ghana. Covid 2024, 4, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health Clinical Spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/clinical-spectrum/ 2022.

- Geng, M.J.; Wang, L.P.; Ren, X.; Yu, J.X.; Chang, Z.R.; Zheng, C.J.; An, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.K.; Zhao, H.T.; et al. Risk Factors for Developing Severe COVID-19 in China: An Analysis of Disease Surveillance Data. Infect Dis Poverty 2021, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingert, A.; Pillay, J.; Gates, M.; Guitard, S.; Rahman, S.; Beck, A.; Vandermeer, B.; Hartling, L. Risk Factors for Severity of COVID-19: A Rapid Review to Inform Vaccine Prioritisation in Canada. BMJ Open 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D.; Nee, S.; Hickey, N.S.; Marschollek, M. Risk Factors for Covid-19 Severity and Fatality: A Structured Literature Review. Infection 2021, 49, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milota, T.; Sobotkova, M.; Smetanova, J.; Bloomfield, M.; Vydlakova, J.; Chovancova, Z.; Litzman, J.; Hakl, R.; Novak, J.; Malkusova, I.; et al. Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 and Hospital Admission in Patients With Inborn Errors of Immunity - Results From a Multicenter Nationwide Study. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 835770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. jin; Dong, X.; Liu, G. hui; Gao, Y. dong Risk and Protective Factors for COVID-19 Morbidity, Severity, and Mortality. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2023, 64, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dajaan Dubik, S.; Ahiable, E.K.; Amegah, K.E.; Manan, A.; Sampong, F.B.; Boateng, J.; Addipa-Adapoe, E.; Atito-Narh, E.; Addy, L.; Donkor, P.O.; et al. Article Risk Factors Associated with COVID-19 Morbidity and Mortality at a National Tertiary Referral Treatment Centre in Ghana: A Retrospective Analysis Risk Factors Associated with COVID-19 Morbidity and Mortality at a National Tertiary Referral Treatment Centre in Ghana: A Retrospective Analysis. PAMJ Clinical Medicine 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrecherkos, T.; Gessesse, Z.; Kebede, Y.; Gebreegzabher, A.; Wit, T.R. De; Wolday, D. Effect of Co-Infection with Parasites on Severity of COVID-19. 2021, 267, 1–15.

- Siles-Lucas, M.; González-Miguel, J.; Geller, R.; Sanjuan, R.; Pérez-Arévalo, J.; Martínez-Moreno, Á. Potential Influence of Helminth Molecules on COVID-19 Pathology. Trends Parasitol 2021, 37, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, P.; Lee, S.C.; Oyesola, O.O. Effects of Helminths on the Human Immune Response and the Microbiome. Mucosal Immunology 2022 15:6 2022, 15, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, L.C.; Monticelli, L.A.; Nice, T.J.; Sutherland, T.E.; Siracusa, M.C.; Hepworth, M.R.; Tomov, V.T.; Kobuley, D.; Tran, S.V.; Bittinger, K.; et al. Virus-Helminthcoinfection Reveals a Microbiota-Independent Mechanism of Immunomodulation. Science (1979) 2014, 345, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osazuwa, F.; Ayo, O.M.; Imade, P. A Significant Association between Intestinal Helminth Infection and Anaemia Burden in Children in Rural Communities of Edo State, Nigeria. N Am J Med Sci 2011, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C. (Roy C. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission; CABI, 2000; ISBN 978-0-85199-786-5.

- Hotez, P.J.; Brindley, P.J.; Bethony, J.M.; King, C.H.; Pearce, E.J.; Jacobson, J. Helminth Infections: The Great Neglected Tropical Diseases. JCI 2008, 118, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesbrough, M. Cheesbrough, M. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries, Second Edition. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries, Second Edition 2006, 1–434. [CrossRef]

- Salgame, P.; Yap, G.S.; Gause, W.C. Effect of Helminth-Induced Immunity on Infections with Microbial Pathogens. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, R.M.; McSorley, H.J. Regulation of the Host Immune System by Helminth Parasites. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 138, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Liu, W.C.; Uhl, S.; Hoagland, D.; Møller, R.; Jordan, T.X.; Oishi, K.; Panis, M.; Sachs, D.; et al. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell 2020, 181, 1036–1045.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, M.S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Innate Immunity: The First Line of Defense against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Knopf, J.; Herrmann, M.; Lin, L.; Jiang, J.; Shao, C.; Li, P.; He, X.; et al. Immune Response in COVID-19: What Is Next? Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, C.M.; Rénia, L.; MacAry, P.A.; Ng, L.F.P. The Trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, Inflammation and Intervention. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, F. The Human Antibody Response to Influenza A Virus Infection and Vaccination. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, S.; Agnandji, S.T.; Berberich, S.; Bache, E.; Fernandes, J.F.; Schweiger, B.; Loembe, M.M.; Engleitner, T.; Lell, B.; Mordmüller, B.; et al. Effect of Antihelminthic Treatment on Vaccine Immunogenicity to a Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in Primary School Children in Gabon: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeilly, T.N.; Nisbet, A.J. Immune Modulation by Helminth Parasites of Ruminants: Implications for Vaccine Development and Host Immune Competence. Parasite 2014, 21, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, S.M.; Kannan, Y.; Pelly, V.S.; Entwistle, L.J.; Guidi, R.; Perez-Lloret, J.; Nikolov, N.; Müller, W.; Wilson, M.S. CD4 + Th2 Cells Are Directly Regulated by IL-10 during Allergic Airway Inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 2017, 10, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, H.C.; Gamino, V.; Andrusaite, A.T.; Ridgewell, O.J.; McCowan, J.; Shergold, A.L.; Heieis, G.A.; Milling, S.W.F.; Maizels, R.M.; Perona-Wright, G. Tissue-Based IL-10 Signalling in Helminth Infection Limits IFNγ Expression and Promotes the Intestinal Th2 Response. Mucosal Immunol 2022, 15, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, L.S.A.; Gazzinelli-Guimarães, P.H.; de Oliveira Mendes, T.A.; Guimarães, A.C.G.; da Silveira Lemos, D.; Ricci, N.D.; Gonçalves, R.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Fujiwara, R.T.; Bueno, L.L. Regulatory Monocytes in Helminth Infections: Insights from the Modulation during Human Hookworm Infection. BMC Infect Dis 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.E.; Sutherland, T.E. Host Protective Roles of Type 2 Immunity: Parasite Killing and Tissue Repair, Flip Sides of the Same Coin. Semin Immunol 2014, 26, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, R.M.; Urban, J.F.; Alem, F.; Hamed, H.A.; Rozo, C.T.; Boucher, J.L.; Van Rooijen, N.; Gause, W.C. Memory TH2 Cells Induce Alternatively Activated Macrophages to Mediate Protection against Nematode Parasites. Nat Med 2006, 12, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cao, Z.; Liu, M.; Diamond, M.S.; Jin, X. The Impact of Helminth-Induced Immunity on Infection with Bacteria or Viruses. Vet Res 2023, 54, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voehringer, D.; Reese, T.A.; Huang, X.; Shinkai, K.; Locksley, R.M. Type 2 Immunity Is Controlled by IL-4/IL-13 Expression in Hematopoietic Non-Eosinophil Cells of the Innate Immune System. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; McDermott, J.; Urban, J.F.; Gause, W.; Madden, K.B.; Yeung, K.A.; Morris, S.C.; Finkelman, F.D.; Shea-Donohue, T. Dependence of IL-4, IL-13, and Nematode-Induced Alterations in Murine Small Intestinal Smooth Muscle Contractility on Stat6 and Enteric Nerves. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Rozo, C.; Bowdridge, S.; Millman, A.; Van Rooijen, N.; Urban, J.F.; Wynn, T.A.; Gause, W.C. An Essential Role for the Th2-Type Response in Limiting Tissue Damage during Helminth Infection. Nat Med 2012, 18, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atagozli, T.; Elliott, D.E.; Ince, M.N. Helminth Lessons in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD). Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrais, M.; Maricoto, T.; Nwaru, B.I.; Cooper, P.J.; Gama, J.M.R.; Brito, M.; Taborda-Barata, L. Helminth Infections and Allergic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Global Literature. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2022, 149, 2139–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, H.H.; Yazdanbakhsh, M. Chronic Helminth Infections Modulate Allergen-Specific Immune Responses: Protection against Development of Allergic Disorders? Ann Med 2007, 39, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, H.H.; Everts, B.; Hartgers, F.C.; Yazdanbakhsh, M. Chronic Helminth Infections Protect Against Allergic Diseases by Active Regulatory Processes. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2010, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitcharungsi, R.; Sirivichayakul, C. Allergic Diseases and Helminth Infections. Pathog Glob Health 2013, 107, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselbeck, A.H.; Im, J.; Prifti, K.; Marks, F.; Holm, M.; Zellweger, R.M. Serology as a Tool to Assess Infectious Disease Landscapes and Guide Public Health Policy. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabello, A.L.T.; Garcia, M.M.A.; Pinto Da Silva, R.A.; Rocha, R.S.; Katz, N. Humoral Immune Responses in Patients with Acute Schistosoma Mansoni Infection Who Were Followed up for Two Years after Treatment. Clin Infect Dis 1997, 24, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, T.; Shi, L.; Zheng, W.; Guan, F.; Lei, J. A New Role for Old Friends: Effects of Helminth Infections on Vaccine Efficacy. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, L.C.; Kapita, C.M.; Campbell, E.; Hall, J.A.; Urban, J.F.; Belkaid, Y.; Nagler, C.R.; Iweala, O.I. Intestinal helminth infection impairs oral and parenteral vaccine efficacy. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.2009.2022.508369. [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Wolday, D.; Akuffo, H.; Petros, B.; Bronner, U.; Britton, S. Effect of deworming on human T cell responses to mycobacterial antigens in helminth-exposed individuals before and after bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2001, 123, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).