Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

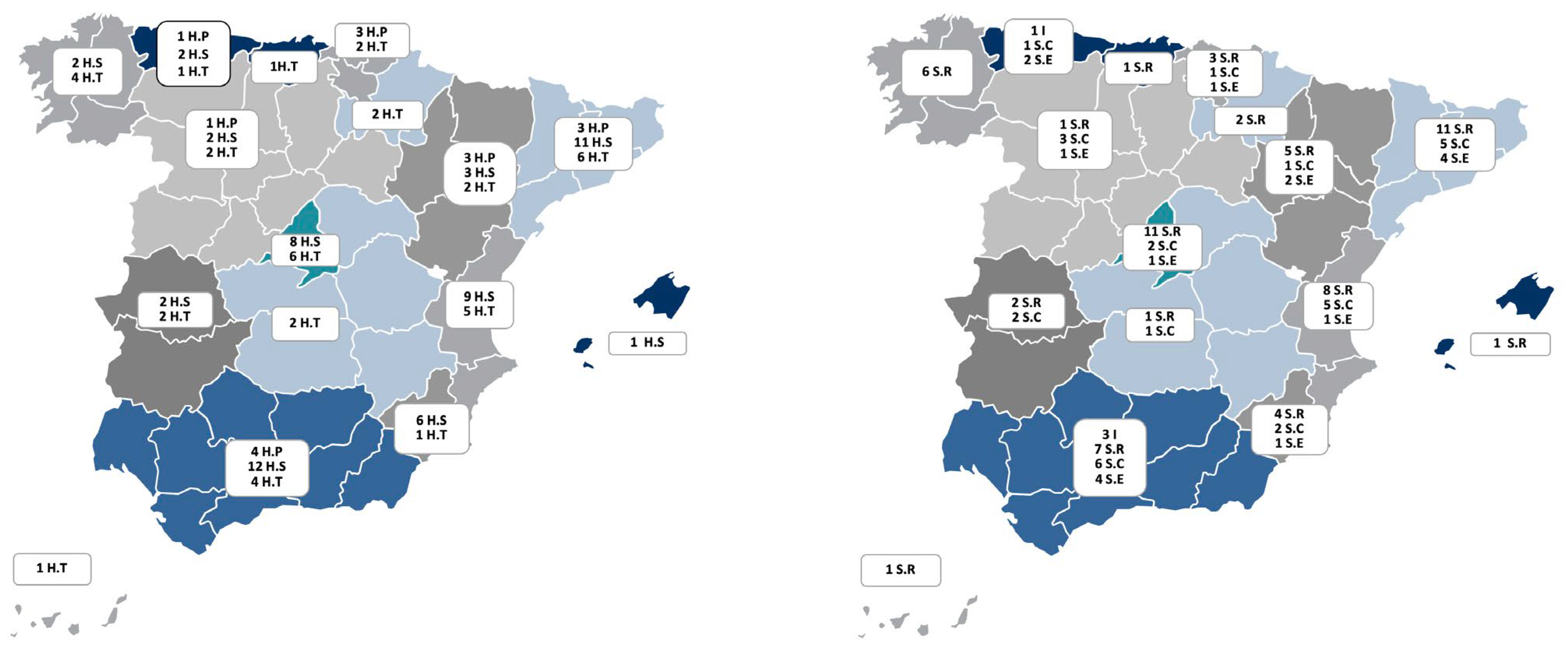

Hospital Resources

Respiratory Unit Resources

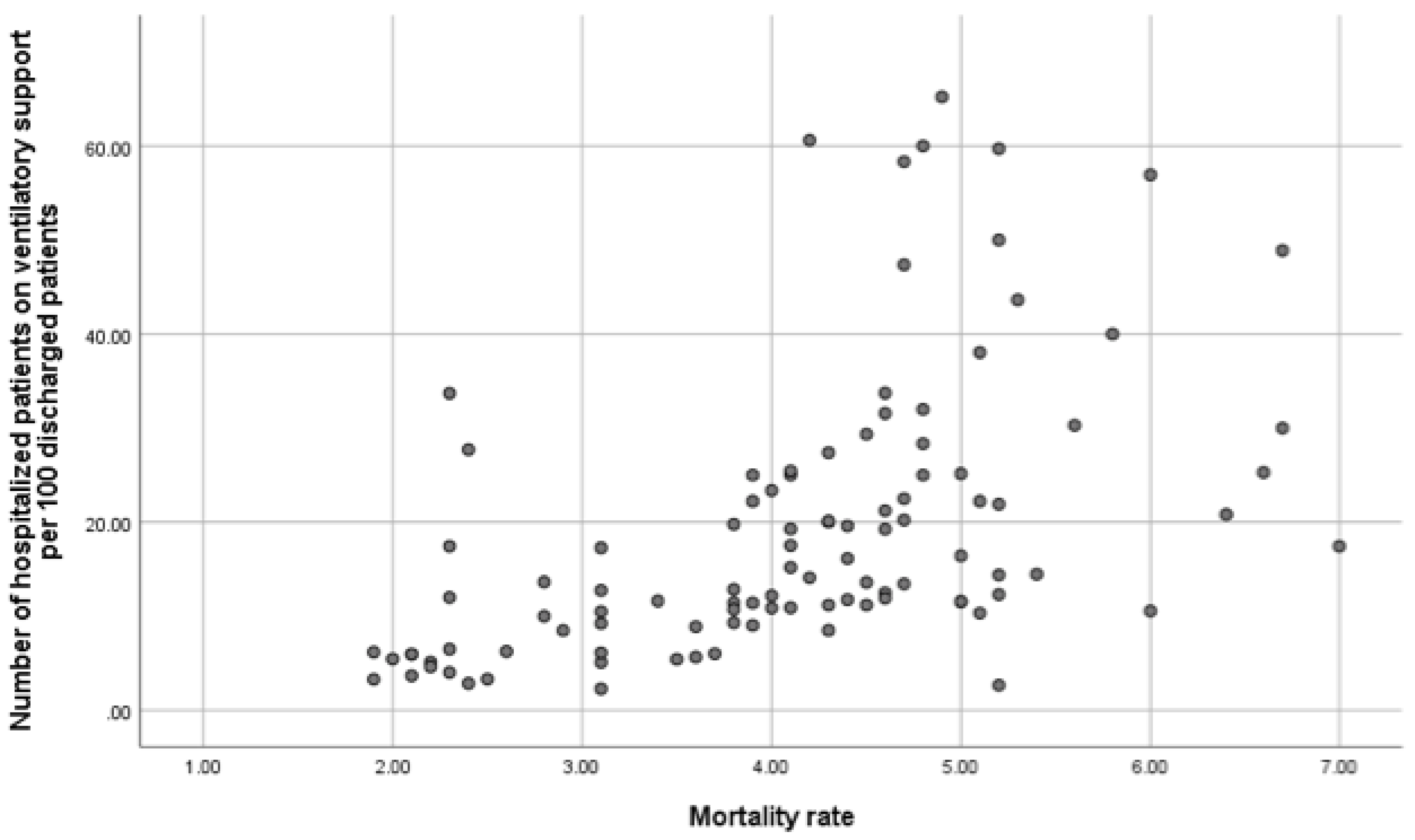

Respiratory Units Performance

Factors Associated with Outcomes: Overall In-Hospital Mortality and 30-Day COPD Readmissions for COPD Exacerbations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMCU | Intermediate Care Unit dependiente |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| SEPAR | Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery |

Appendix

Appendix 1: Participants in COPD OBSERVATORY study.

References

- World Health Organization, Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. http:// https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd. (accessed on 22 Nov 2024).

- López-Campos, J.L.; Tan, W.; Soriano, J.B. Global burden of COPD. Respirology 2016, 21, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Paulson, K.R.; Gupta, V.; Abrams, E.M.; Adedoyin, R.A.; Adhikari, T.B.; Advani, S.M.; Agrawal, A.; Ahmadian, E.; et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanacho, I.; Zhang, S.; King, D.; Rizzo, M.; Ismaila, A.S. Economic Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Hassali, M.A.A.; Muhammad, S.A.; Shah, S.; Abbas, S.; Ali, I.A.B.H.; Salman, A. The economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the USA, Europe, and Asia: results from a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2019, 20, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- On behalf of the EPOCONSUL Study; Rubio, M. C.; López-Campos, J.L.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Navarrete, B.A.; Soriano, J.B.; González-Moro, J.M.R.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Hermosa, J.L.R. Variability in adherence to clinical practice guidelines and recommendations in COPD outpatients: a multi-level, cross-sectional analysis of the EPOCONSUL study. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.C.; López-Campos, J.L.; Miravitlles, M.; Cataluña, J.J.S.; Navarrete, B.A.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Hermosa, J.L.R. Variations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Outpatient Care in Respiratory Clinics: Results From the 2021 EPOCONSUL Audit. Arch. De Bronc- 2023, 59, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.M.; Barnes, S.; Lowe, D.; Pearson, M.G. Evidence for a link between mortality in acute COPD and hospital type and resources. Thorax 2003, 58, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rodríguez, F.; López-Campos, J.L.; Álvarez-Martínez, C.J.; Castro-Acosta, A.; Agüero, R.; Hueto, J.; Hernández-Hernández, J.; Barrón, M.; Abraira, V.; Forte, A.; et al. Clinical Audit of COPD Patients Requiring Hospital Admissions in Spain: AUDIPOC Study. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e42156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stukel, T.A.; Fisher, E.S.; Alter, D.A.; Guttmann, A.; Ko, D.T.; Fung, K.; Wodchis, W.P.; Baxter, N.N.; Earle, C.C.; Lee, D.S. Association of Hospital Spending Intensity With Mortality and Readmission Rates in Ontario Hospitals. JAMA 2012, 307, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romley, J.A.; Jena, A.B.; Goldman, D.P.; Gilman, B.M.; Hockenberry, J.M.; Adams, E.K.; Milstein, A.S.; Wilson, I.B.; Becker, E.R.; Hussey, P.S.; et al. Hospital Spending and Inpatient Mortality: Evidence From California: an observational study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 154, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartl, S.; Lopez-Campos, J.L.; Pozo-Rodriguez, F.; Castro-Acosta, A.; Studnicka, M.; Kaiser, B.; Roberts, C.M. Risk of death and readmission of hospital-admitted COPD exacerbations: European COPD Audit. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Campos, J.L.; Hartl, S.; Pozo-Rodriguez, F.; Roberts, C.M. Variability of hospital resources for acute care of COPD patients: the European COPD Audit. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 43, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, M.C.; Navarrete, B.A.; Soriano, J.B.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; González-Moro, J.-M.R.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Clinical audit of COPD in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain: the EPOCONSUL study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, ume 12, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estudio RECALAR. Monografia Archivos de Bronconeumologia de la SEPAR. 2018;5:1-64.

- Patil, S.P.; Krishnan, J.A.; Lechtzin, N.; Diette, G.B. In-Hospital Mortality Following Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Xing, Z.; Long, H.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, P.; Janssens, J.-P.; Guo, Y. Predictors of mortality in COPD exacerbation cases presenting to the respiratory intensive care unit. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singanayagam, A.; Schembri, S.; Chalmers, J.D. Predictors of Mortality in Hospitalized Adults with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013, 10, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waeijen-Smit, K.; Crutsen, M.; Keene, S.; Miravitlles, M.; Crisafulli, E.; Torres, A.; Mueller, C.; Schuetz, P.; Ringbæk, T.J.; Fabbian, F.; et al. Global mortality and readmission rates following COPD exacerbation-related hospitalisation: a meta-analysis of 65 945 individual patients. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Campos, J.L.; Hartl, S.; Pozo-Rodriguez, F.; Roberts, C.M. European COPD Audit: design, organisation of work and methodology. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.M.; Stone, R.A.; Buckingham, R.J.; Pursey, N.A.; Lowe, D. ; On behalf of the National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Resources and Outcomes Project (NCROP) implementation group Acidosis, non-invasive ventilation and mortality in hospitalised COPD exacerbations. Thorax 2011, 66, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, M.; Trevisan, R.; Demsar, M.; Lattuada, L.; Longo, C.; Cifaldi, R.; Jevnikar, M.; Santagiuliana, M.; Pelusi, L.; Pistelli, R. Opening of a Respiratory Intermediate Care Unit in a General Hospital: Impact on Mortality and Other Outcomes. Respiration 2015, 90, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenauer, P.K.; Dharmarajan, K.; Qin, L.; Lin, Z.; Gershon, A.S.; Krumholz, H.M. Risk Trajectories of Readmission and Death in the First Year after Hospitalization for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Owen, S.J.; Donaldson, G.C.; Ambrosino, N.; Escarabill, J.; Farre, R.; Fauroux, B.; Robert, D.; Schoenhofer, B.; Simonds, A.K.; Wedzicha, J.A. Patterns of home mechanical ventilation use in Europe: results from the Eurovent survey. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 25, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergan, B.; Oczkowski, S.; Rochwerg, B.; Carlucci, A.; Chatwin, M.; Clini, E.; Elliott, M.; Gonzalez-Bermejo, J.; Hart, N.; Lujan, M.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines on long-term home non-invasive ventilation for management of COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1901003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrea, M.; Oczkowski, S.; Rochwerg, B.; Branson, R.D.; Celli, B.; Coleman, J.M.; Hess, D.R.; Knight, S.L.; Ohar, J.A.; Orr, J.E.; et al. Long-Term Noninvasive Ventilation in Chronic Stable Hypercapnic Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, e74–e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crimi, C.; Noto, A.; Princi, P.; Cuvelier, A.; Masa, J.F.; Simonds, A.; Elliott, M.W.; Wijkstra, P.; Windisch, W.; Nava, S. Domiciliary Non-invasive Ventilation in COPD: An International Survey of Indications and Practices. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2016, 13, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea-Santaolalla, C.J.; Vives, E.C.; Lobato, S.D.; Mangado, N.G.; Tomé, M.L.; Andrés, O.M.S. Ventilación mecánica a domicilio. Open Respir. Arch. 2020, 2, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, I.; Ajorlou, S.; Yang, K. A predictive analytics approach to reducing 30-day avoidable readmissions among patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, or COPD. Heal. Care Manag. Sci. 2015, 18, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Han, W.; Li, J. Readmission rate for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir. Med. 2022, 206, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, G.C.; Seemungal, T.A.R.; Bhowmik, A.; A Wedzicha, J. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002, 57, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Cataluna, J.J.; Martínez-García, M. .; Sánchez, P.R.; Salcedo, E.; Navarro, M.; Ochando, R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005, 60, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, S.; Represas-Represas, C.; Ruano-Raviña, A.; Mouronte-Roibás, C.; Botana-Rial, M.; Ramos-Hernández, C.; Fernández-Villar, A. Social and clinical predictors of short- and long-term readmission after a severe exacerbation of copd. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabeu-Mora, R.; Valera-Novella, E.; Bernabeu-Serrano, E.T.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Calle-Rubio, M.; Medina-Mirapeix, F. Five-Repetition Sit-to-Stand Test as Predictor of Mortality in High Risk COPD Patients. Arch. De Bronc-, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.P.; Wells, J.M.; Iyer, A.S.; Kirkpatrick, D.P.; Parekh, T.M.; Leach, L.T.; Anderson, E.M.; Sanders, J.G.; Nichols, J.K.; Blackburn, C.C.; et al. Results of a Medicare Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Readmissions. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, J.H.; Thavarajah, K.; Mendez, M.P.; Eichenhorn, M.; Kvale, P.; Yessayan, L. Predischarge Bundle for Patients With Acute Exacerbations of COPD to Reduce Readmissions and ED Visits. Chest 2015, 147, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassin, M.R.; Loeb, J.M.; Schmaltz, S.P.; Wachter, R.M. Accountability Measures — Using Measurement to Promote Quality Improvement. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, A.D.; Kripalani, S.; Vasilevskis, E.E.; Sehgal, N.; Lindenauer, P.K.; Metlay, J.P.; Fletcher, G.; Ruhnke, G.W.; Flanders, S.A.; Kim, C.; et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, A.; Zhou, A.; Taubman, S.; Doyle, J. Health Care Hotspotting — A Randomized, Controlled Trial. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.R.; Ross, J.S.; Kwon, J.Y.; Herrin, J.; Dharmarajan, K.; Bernheim, S.M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Horwitz, L.I. Association Between Hospital Penalty Status Under the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program and Readmission Rates for Target and Nontarget Conditions. JAMA 2016, 316, 2647–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Global | Level I | Level II | Level III | |

| Number of centers, n (%) | 116 | 15 (12.9) | 58 (50) | 43 (37.1) |

| Number of inhabitants of reference population, median (IQR) | 170000 (49560-303750) | 95000 (23750-138750) | 160000 (31552-282500) | 300000 (48000-437406) |

| Number of hospital beds per 100.000 inhabitans, median (IQR) | 157 (125-230.3) |

146.4 (100-189.7) |

147 (114.8-221.8) |

175.3 (134.8-248) |

| University Hospital, n (%) | 89 (76.7) | 3 (20) | 44 (75.9) | 42 (97.7) |

| Public hospital, n (%) | 113 (97.4) | 14 (93.3) | 58 (100) | 41 (95.3) |

| Institutional denomination of the pneumology service or unit, n (%) Institute Service Section No organizational entity |

4 (3.4) 65 (56) 30 (25.9) 17 (14.7) |

3 (20) 3 (20) 9 (60) |

2 (3.4) 25 (43.1) 23 (39.7) 8 (13.8) |

2 (4.7) 37 (86) 4 (9.3) 0 |

| Number of pulmonologists/100.000 inhabitants, median (IQR) | 3.3 (2.6-4.1) | 2.9 (2.3-3.9) | 3 (2.4-4) | 3.7 (3-4.6) |

| Number of resident interns in pulmonology, median (IQR) | 0 (2-4) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-4) | 6 (4-8) |

| Number of pneumology beds per 100.000 inhabitans, median (IQR) | 6.6 (3.1-9.2) | 0 (0-5.9) | 6.2 (0-9.5) | 7.5 (5.5-9.6) |

| Number of pneumology beds with telemetry, median (IQR) | 0 (0-6) | 0 | 0 (0-4) | 6 (0-8) |

| Intermediate Care Unit (IMCU) managed by pulmonology, n (%) | 37 (31.9) | 0 | 9 (15.5) | 28 (65.1) |

| Number of beds IMCU, median (IQR) | 6 (4-8) | 0 | 5.1 (4-6.5) | 7 (6-8.7) |

| Ratio of nurses to beds in IMCU*, median (IQR) | 4 (4-6) | - | 5.1 (4-5) | 5 (4-6) |

| 24-hour emergency care provided by pulmonology, n (%) Presencial |

35 (30.2) 26 (74.3) |

0 | 5 (8.6) 5 (100) |

30 (69.8) 21 (70) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation program for COPD n (%) Type of program - Hospital - Community-based Mixed |

68 (58.6) 27 (39.7) 4 (5.9) 37 (54.4) |

4 (26.7) 4 (100) |

33 (56.9) 15 (45.5) 1 (3) 17 (51.5) |

31 (73.8) 12 (38.7) 3 (9.7) 16 (51.6) |

| Exercise test with oxygen uptake, n (%) | 47 (40.5) | 2 (13.3) | 12 (20.7) | 33 (76.7) |

| Bronchoscopy unit, n (%) High complexity Offer volume reduction techniques, n (%) |

39 (33.6) 11 (9.5) |

0 0 |

6 (10.3) 0 |

19 (44.2) 11 (25.6) |

| Diagnostic tests for alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), n (%) AATD Genotyping Sequencing |

61 (52.6) 16 (13.8) |

9 (60) 2 (13.3) |

23 (39.7) 2 (3.4) |

29 (67.4) 12 (27.9) |

| Consulting pulmonologist, n (%) | 67 (57.8) | 11 (73.3) | 34 (58.6) | 22 (51.2) |

| Therapeutic education program, n (%) | 40 (34.5) | 3 (75) | 14 (87.5) | 23 (95.8) |

| Discharge follow-up and support program, n (%) | 64 (55.2) | 9 (60) | 28 (50) | 27 (64.3) |

| Consulting specialist for the COPD, n (%) | 53 (45.6) | 5 (35.7) | 20 (35.1) | 28 (65.1) |

| COPD process protocols written, n (%) | 42 (36.2) | 0 | 15 (60) | 27 (77.1) |

| Unscheduled consultation for immediate COPD care, n (%) | 51 (44) | 5 (33.3) | 22 (37.9) | 24 (55.8) |

| Specialized COPD consultation, n (%) Accredited Time allocated to consultation (minutes), median (IQR) First consultation Review consultation |

61 (52.6) 18 (30) 30 (20-30) 15 (15-20) |

1 (6.7) 30 (30-30) 20 (20-20) |

25 (43.1) 4 (16) 20 (20-30) 15 (15-17) |

35 (81.4) 14 (40) 30 (20-30) 15 (15-20) |

| Nurse consultation for COPD care, n (%) | 45 (38.8) | 4 (26.7) | 16 (27.6) | 25 (58.1) |

| Specialized smoking consultation, n (%) | 56 (48.3) | 5 (33.3) | 19 (32.8) | 32 (74.4) |

| Global | Level I | Level II | Level III | |

| Number discharges per pneumology unit/100,000 inhabitants, median (IQR) | 266.2 (186.8-399.2) | 218.3 (99.3-402.1) | 250 (304.2-841.2) | 294 (193.3-417.8) |

| Average length of stay (days), m (SD) | 8.72 (1.26) | 7.82 (1.17) | 8.85 (1.24) | 8.70 (1.26) |

| Number of 30-day readmissions for COPD /100 discharges *, median (IQR) | 14.9 (10.1-18.7) | 10.7 (8.2-15) | 15.5 (12.1-19.4) | 13.1 (8.6-16.7) |

| Number of patients on acute noninvasive ventilatory support per year/ 100 discharges, median (IQR) | 13.8 (9.2-25) | 6.2 (5.4-20) | 13.8 (9.2-25) | 14.4 (10.5-25.4) |

| In-hospital mortality #, m (SD) | 4.10 (1.18) | 2.6 (1.23) | 4.09 (1.14) | 4.27 (1.17) |

| Number of spirometries performed per month, median (IQR) | 303 (160-450) | 160 (100-280) | 222.5 (135-400) | 580 (350-845) |

| Number of spirometries per month/100,000 population, median (IQR) | 121.4 (70-225.7) | 170.5 (95.8-320) | 104.2 (60.8-159) | 141.7 (77.7-230.7) |

| Number of diffusion tests performed per month, median (IQR) | 40 (100-175) | 10 (0-40) | 78 (40-135) | 200 (110-300) |

| Number of lung volume measurements performed per month, median (IQR) | 20 (45-115) | 1 (0-25) | 40 (20-90) | 100 (35-150) |

| Number of 6 minutes walking test per month, median (IQR) | 27 (13-51) | 15 (10-25) | 22 (12-45) | 50 (30-100) |

| Number of patients in home ventilation programme, median (IQR) | 150 (48.7-282) | 70 (25-150) | 145.2 (29-205) | 260 (92-385) |

| Number of patients on home ventilation/100.00 inhabitant, median (IQR) | 57.8 (20.3 – 100.5) | 51.8 (15.1 – 115.4) | 49.3 (14.5 – 95.2) | 74.3 (25.8 – 99.6) |

| Number of bronchoscopic procedures per year, median (IQR) | 468 (210-750) | 86 (50-200) | 321 (200-500) | 763 (550-1177) |

| Number of bronchoscopic per year/100,000 inhabitants, median (IQR) | 164 (114.8-244.8) | 94.9 (67.9-156.8) | 156.2 (112.5-233.3) | 210.8 (153.5-274) |

| Number of patients undergoing endoscopic volume reduction per year, median (IQR) | 5 (4-17) | 5 (4-18) | ||

| Number of patients diagnosed with AATD per year median (IQR) | 5 (2-20) | 4 (2.7-10) | 5 (2-13.5) | 14.5 (3.25-50) |

| Number of patients diagnosed with severe AATD per year, median (IQR) | 2 (1-5) | 1 (0-2) | 2 (0-3) | 4 (1-10) |

| Number of patients on augmentation therapy for AATD per year, median (IQR) | 2 (0-4) | 1 (0-1) | 2 (0-3) | 3 (1-7) |

| 30-day readmissions for COPD* | p-value# | β coefficient (IC95%) | p-value# | Regression Coefficientsα | |

| Hospital complexity, m (IQR) Level I or primary hospital Level II or secondary hospital Level III or tertiary hospital |

10.7 (8.2-15.0) 15.5 (12.1-19.4) 13.1 (8.6-16.7) |

0.041 |

2.036 (-2.524- 6.596) -0.441 (-5.059- 4.177) |

0.378 0.850 |

|

| Availability of specialized consultation COPD, m (SD) Not Yes |

16.2 (5.3) 13.2 (5.2) |

0.006 |

-2.932 (-4.984 -0.881) |

0.006 |

|

| Availability of immediate attention, m (SD) Not Yes |

16.3 (5.1) 12.5 (5.1) |

<0.001 |

-3.805 (-5.792 -1.818) |

<0.001 |

|

| Availability of post-discharge follow-up program, m (SD) Not Yes |

17.7 (5.1) 12.1 (4.3) |

<0.001 |

-5.624 (-7.492 -3.756) |

<0.001 |

|

| Specialist COPD consultant available, m (SD) Not Yes |

15.9 (5.3) 13 (5.2) |

0.007 |

-2.865 ( -4.927 -0.802) |

0.007 |

|

| COPD nurse's office available, m (SD) Not Yes |

16.2 (5.3) 12.0 (4.5) |

<0.001 |

-4.260 (-6.266 -2.253) |

<0.001 |

|

| In-hospital stay | 1.789 ( 1.023 2.556) | <0.001 | 0.418 | ||

| Number of acutely ventilated patients per 100 discharges | 0.131 (0.063 0.199) | <0.001 | 0.348 | ||

| Availability of IMCU, m (SD) Not Yes |

15.5 (5.5) 13.3 (5) |

0.054 | |||

| To have written protocols in COPD, m (SD) Not Yes |

13.6 (5.8) 13 (5) |

0.693 | |||

| Have a respiratory rehabilitation program, m (SD) Not Yes |

15.5 (5.7) 13.9 (5.2) |

0.146 | |||

| To have 24-hour emergency care provided by pulmonology, m (SD) Not Yes |

14.9 (5.7) 13.9 (4.8) |

0.381 | |||

| Number of discharges per 100,000 inhabitants | -0.342 | ||||

| Number of pulmonologists per 100,000 inhabitants | -0.209 |

| VARIABLE | β coefficient | Lower 95% IC | Upper 95% IC |

| Availability of immediate attention | -1.17680 | -3.2926682466 | 0.9390732 |

| Availability Therapeutic education program for the COPD | -1.06925 | -3.2966721762 | 1.1581651 |

| Availability Specialized COPD consultation | -0.27570 | -2.4957277620 | 1.9443309 |

| Average length of stay | 1.21028 | 0.4459950155 | 1.9745690 |

| Availability Consulting specialist for the COPD | -1.00004 | -3.2838274923 | 1.2837502 |

| Number of patients on acute noninvasive ventilatory support per year/ 100 discharges | 0.07243 | 0.0065636954 | 0.1383044 |

| Availability of post-discharge follow-up program | -3.89691 | -5.8584889147 | -1.9353364 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).