Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds in Serum

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Resules

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients

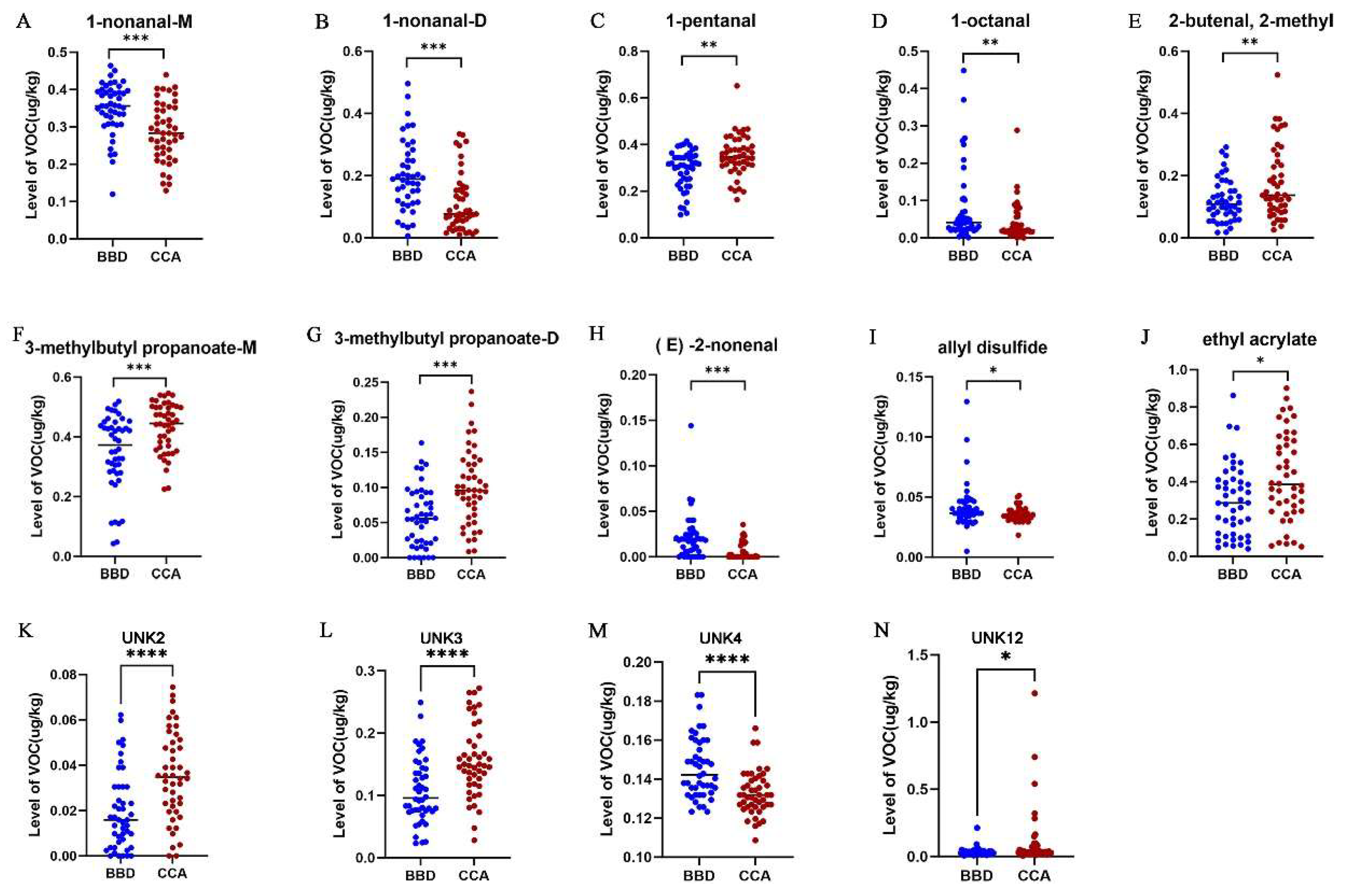

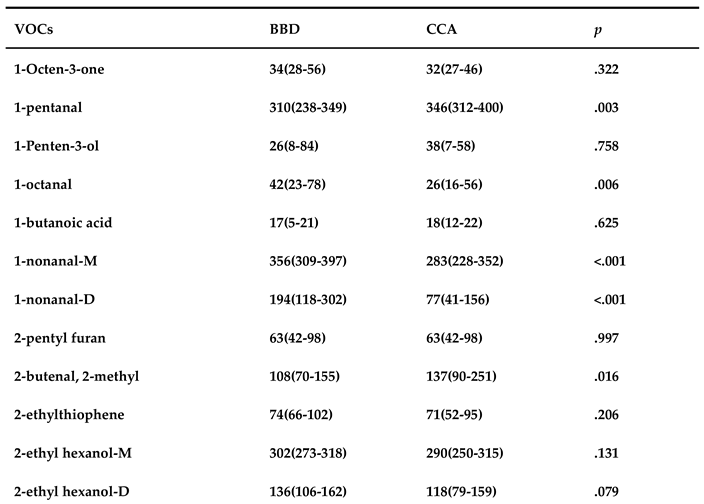

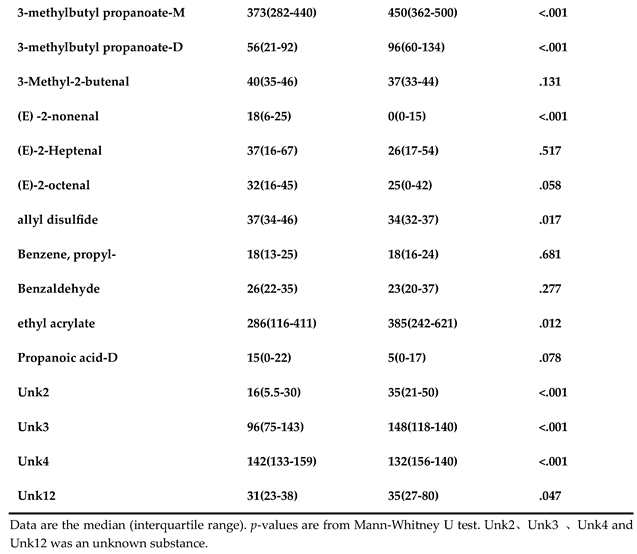

3.2. VOC Profile Analysis in CCA and BBD Patients

3.5. Vocs biomarkers in serum and pathological parameters

3.3. Quantitative Analysis of VOCs in serum sample

3.4. Diagnostic Performance of ROC Analysis for Vocs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeOliveira, M. L.; Cunningham, S. C.; Cameron, J. L.; Kamangar, F.; Winter, J. M.; Lillemoe, K. D.; Choti, M. A.; Yeo, C. J.; Schulick, R. D. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg 2007, 245 (5), 755-762. [CrossRef]

- Nakeeb, A.; Pitt, H. A.; Sohn, T. A.; Coleman, J.; Abrams, R. A.; Piantadosi, S.; Hruban, R. H.; Lillemoe, K. D.; Yeo, C. J.; Cameron, J. L. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996, 224 (4), 463-473; discussion 473-465. [CrossRef]

- Moris, D.; Palta, M.; Kim, C.; Allen, P. J.; Morse, M. A.; Lidsky, M. E. Advances in the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: An overview of the current and future therapeutic landscape for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin 2023, 73 (2), 198-222. [CrossRef]

- Vithayathil, M.; Khan, S. A. Current epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma in Western countries. J Hepatol 2022, 77 (6), 1690-1698. [CrossRef]

- Saluja, S. S.; Sharma, R.; Pal, S.; Sahni, P.; Chattopadhyay, T. K. Differentiation between benign and malignant hilar obstructions using laboratory and radiological investigations: a prospective study. HPB (Oxford) 2007, 9 (5), 373-382. [CrossRef]

- Brindley, P. J.; Bachini, M.; Ilyas, S. I.; Khan, S. A.; Loukas, A.; Sirica, A. E.; Teh, B. T.; Wongkham, S.; Gores, G. J. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7 (1), 65. [CrossRef]

- Cerrito, L.; Ainora, M. E.; Borriello, R.; Piccirilli, G.; Garcovich, M.; Riccardi, L.; Pompili, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Zocco, M. A. Contrast-Enhanced Imaging in the Management of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: State of Art and Future Perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15 (13). [CrossRef]

- Guedj, N. Pathology of Cholangiocarcinomas. Curr Oncol 2022, 30 (1), 370-380. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Dungubat, E.; Kusano, H.; Ganbat, D.; Tomita, Y.; Odgerel, S.; Fukusato, T. Application of Immunohistochemistry in the Pathological Diagnosis of Liver Tumors. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22 (11). [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, S.; Nishimaki, T.; Kanda, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Ohashi, M.; Hatakeyama, K. Clinical significance of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels in esophageal cancer patients. World J Surg 2004, 28 (7), 680-685. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Markar, S. R.; Matar, M.; Ni, M.; Hanna, G. B. Use of Tumor Markers in Gastrointestinal Cancers: Surgeon Perceptions and Cost-Benefit Trade-Off Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2017, 24 (5), 1165-1173. [CrossRef]

- Banales, J. M.; Marin, J. J. G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P. M.; Khan, S. A.; Roberts, L. R.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Andersen, J. B.; Braconi, C.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17 (9), 557-588. [CrossRef]

- Lindnér, P.; Rizell, M.; Hafström, L. The impact of changed strategies for patients with cholangiocarcinoma in this millenium. HPB Surg 2015, 2015, 736049. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Cataneo, R. N.; Greenberg, J.; Grodman, R.; Gunawardena, R.; Naidu, A. Effect of oxygen on breath markers of oxidative stress. Eur Respir J 2003, 21 (1), 48-51. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J. W.; Park, H. W.; Kim, W. J.; Kim, M. G.; Lee, S. J. Exposure to volatile organic compounds and airway inflammation. Environ Health 2018, 17 (1), 65. [CrossRef]

- Sukaram, T.; Apiparakoon, T.; Tiyarattanachai, T.; Ariyaskul, D.; Kulkraisri, K.; Marukatat, S.; Rerknimitr, R.; Chaiteerakij, R. VOCs from Exhaled Breath for the Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13 (2). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Muhammad, K. G.; Madeeha, C.; Fu, W.; Xu, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Ying, K.; Chen, L.; Yurievna, G. O. Calculated indices of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhalation for lung cancer screening and early detection. Lung Cancer 2021, 154, 197-205. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, N. I.; Jamal, Q.; Iqbal, A.; Shaikh, F.; Somroo, S.; Musharraf, S. G. Serum Metabolomic Profiles for Breast Cancer Diagnosis, Grading and Staging by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Sci Rep 2017, 7 (1), 1715. [CrossRef]

- Kononova, E.; Mežmale, L.; Poļaka, I.; Veliks, V.; Anarkulova, L.; Vilkoite, I.; Tolmanis, I.; Ļeščinska, A. M.; Stonāns, I.; Pčolkins, A.; et al. Breath Fingerprint of Colorectal Cancer Patients Based on the Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25 (3). [CrossRef]

- (20) da Costa, B. R. B.; De Martinis, B. S. Analysis of urinary VOCs using mass spectrometric methods to diagnose cancer: A review. Clin Mass Spectrom 2020, 18, 27-37. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Boshier, P.; Myridakis, A.; Belluomo, I.; Hanna, G. B. Urinary Volatile Organic Compound Analysis for the Diagnosis of Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review and Quality Assessment. Metabolites 2020, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Capitain, C.; Weller, P. Non-Targeted Screening Approaches for Profiling of Volatile Organic Compounds Based on Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectroscopy (GC-IMS) and Machine Learning. Molecules 2021, 26 (18). [CrossRef]

- Christmann, J.; Rohn, S.; Weller, P. gc-ims-tools - A new Python package for chemometric analysis of GC-IMS data. Food Chem 2022, 394, 133476. [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Zhang, X.; Xin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Schiöth, H. B.; et al. Identification and validation of volatile organic compounds in bile for differential diagnosis of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Chim Acta 2023, 541, 117235. [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, U.; Parsi, M. A.; Lourdusamy, V.; Bhatt, A.; Gutierrez, N. G.; Grove, D.; Sanaka, M. R.; Hammel, J. P.; Stevens, T.; Vargo, J. J.; et al. Volatile organic compounds in bile for early diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc 2015, 81 (4), 943-949.e941. [CrossRef]

- Moura, P. C.; Raposo, M.; Vassilenko, V. Breath volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as biomarkers for the diagnosis of pathological conditions: A review. Biomed J 2023, 46 (4), 100623. [CrossRef]

- Sana, S. R.; Chen, G. M.; Lv, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, E. Y. Metabonomics fingerprint of volatile organic compounds in serum and urine of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2022, 13 (10), 888-899. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Mao, M.; Gui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Serum-volatile organic compounds in the diagnostics of esophageal cancer. Sci Rep 2024, 14 (1), 17722. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Gao, M.; Huang, F.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Z. Serum HDL partially mediates the association between exposure to volatile organic compounds and kidney stones: A nationally representative cross-sectional study from NHANES. Sci Total Environ 2024, 907, 167915. [CrossRef]

- Glaab, V.; Collins, A. R.; Eisenbrand, G.; Janzowski, C. DNA-damaging potential and glutathione depletion of 2-cyclohexene-1-one in mammalian cells, compared to food relevant 2-alkenals. Mutat Res 2001, 497 (1-2), 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Shortall, K.; Djeghader, A.; Magner, E.; Soulimane, T. Insights into Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Enzymes: A Structural Perspective. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 659550. [CrossRef]

- Perchuk, I.; Shelenga, T.; Gurkina, M.; Miroshnichenko, E.; Burlyaeva, M. Composition of Primary and Secondary Metabolite Compounds in Seeds and Pods of Asparagus Bean (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) from China. Molecules 2020, 25 (17). [CrossRef]

- Monedeiro, F.; Monedeiro-Milanowski, M.; Zmysłowski, H.; De Martinis, B. S.; Buszewski, B. Evaluation of salivary VOC profile composition directed towards oral cancer and oral lesion assessment. Clin Oral Investig 2021, 25 (7), 4415-4430. [CrossRef]

- Vainio, H.; Heseltine, E.; Wilbourn, J. Priorities for Future IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Environ Health Perspect 1994, 102 (6-7), 590-591. [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. M.; Cohen, A. J.; Loughlin, J. E.; Rothman, K. J.; DeFonso, L. R. Mortality from cancer of the colon or rectum among workers exposed to ethyl acrylate and methyl methacrylate. Scand J Work Environ Health 1991, 17 (1), 7-19. [CrossRef]

- Bastaki, S. M. A.; Ojha, S.; Kalasz, H.; Adeghate, E. Chemical constituents and medicinal properties of Allium species. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476 (12), 4301-4321. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, X.; Tang, H.; Ye, F.; Yang, L.; Guo, X.; Tian, Z.; Xie, X.; Peng, C.; Xie, X. Diallyl Disulfide Inhibits Breast Cancer Stem Cell Progression and Glucose Metabolism by Targeting CD44/PKM2/AMPK Signaling. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18 (6), 592-599. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Montaut, S.; Yang, G. Hydrogen Sulfide Signaling Axis as a Target for Prostate Cancer Therapeutics. Prostate Cancer 2016, 2016, 8108549. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhao, W.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, W.; Xing, C.; Zhuang, C.; Qu, Z. Diallyl Disulfide Blocks Cigarette Carcinogen 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-Induced Lung Tumorigenesis via Activation of the Nrf2 Antioxidant System and Suppression of NF-κB Inflammatory Response. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71 (46), 17763-17774. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Kong, Y.; Guo, J.; Tang, Y.; Xie, X.; Yang, L.; Su, Q.; Xie, X. Diallyl disulfide suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in human gastric cancer through Wnt-1 signaling pathway by up-regulation of miR-200b and miR-22. Cancer Lett 2013, 340 (1), 72-81. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J.; Kang, S.; Kim, D. Y.; You, S.; Park, D.; Oh, S. C.; Lee, D. H. Diallyl disulfide (DADS) boosts TRAIL-Mediated apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells by inhibiting Bcl-2. Food Chem Toxicol 2019, 125, 354-360. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Das, R.; Emran, T. B.; Labib, R. K.; Noor, E. T.; Islam, F.; Sharma, R.; Ahmad, I.; Nainu, F.; Chidambaram, K.; et al. Diallyl Disulfide: A Bioactive Garlic Compound with Anticancer Potential. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 943967. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Lin, J.; Su, J.; Oyang, L.; Wang, H.; Tan, S.; Tang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Luo, X.; et al. Diallyl disulfide inhibits colon cancer metastasis by suppressing Rac1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Onco Targets Ther 2019, 12, 5713-5728. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Liu, X. W.; Huang, X. L.; Xu, X. F.; Xie, W. Q.; Zhang, S. J.; Tu, J. Tristetraprolin: A novel target of diallyl disulfide that inhibits the progression of breast cancer. Oncol Lett 2018, 15 (5), 7817-7827. [CrossRef]

| BBD | CCA | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age# | 55.13±17.712 | 70±10.75 | .001 |

| Male/Female | 24/22 | 28/18 | .406 |

| AFP* | 1.515(1.157-2.512) | 1.64(1.052-2.837) | .799 |

| CEA* | 1.590(0.815-2.282) | 2.825(1.775-4.742) | .001 |

| CA199* | 18.45(8.625-38.55) | 278(98.975-854.5) | .001 |

| WBC* | 6.095(5.452-7.020) | 6.980(4.720-8.275) | .689 |

| ALP* | 77(58.25-135) | 221.95(161.5-519.75) | .001 |

| GGT* | 51.6(18-178) | 215(127.75-385) | .001 |

| ALT* | 25.1(14.975-66.175) | 37.3(21.775-70.475) | .161 |

| AST* | 22.1(15.75-36.025) | 41.15(27.325-52.775) | .001 |

| VOCs | Age | Gender | Areas | Differentiation | Jaundice | Pathological Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-nonanal-M | 0.318 | 0.212 | 0.966 | 0.847 | 0.170 | 0.725 |

| 1-nonanal-D | 0.506 | 0.071 | 0.942 | 0.989 | 0.329 | 0.891 |

| 1-pentanal | 0.233 | 0.589 | 0.158 | 0.280 | 0.039 | 0.055 |

| 1-octanal | 0.894 | 0.552 | 0.811 | 0.503 | 0.667 | 0.560 |

| 2-butenal,2-methyl | 0.381 | 0.906 | 0.650 | 0.201 | 0.254 | 0.631 |

| 3-methylbutyl propanoate-M | 0.203 | 0.831 | 0.233 | 0.639 | 0.313 | 0.004 |

| 3-methylbutyl propanoate-D | 0.866 | 0.884 | 0.128 | 0.295 | 0.763 | 0.036 |

| (E) -2-nonenal | 0.398 | 0.239 | 0.823 | 0.639 | 0.644 | 0.891 |

| allyl disulfide | 0.721 | 0.595 | 0.870 | 0.853 | 0.555 | 0.132 |

| ethyl acrylate | 0.730 | 0.464 | 0.322 | 0.846 | 0.987 | 0.038 |

| Unk2 | 0.750 | 0.457 | 0.694 | 0.221 | 0.245 | 0.369 |

| Unk3 | 0.508 | 0.719 | 0.444 | 0.800 | 0.508 | 0.458 |

| Unk4 | 0.135 | 0.550 | 0.333 | 0.943 | 0.017 | 0.515 |

| Unk12 | 0.903 | 0.606 | 0.877 | 0.659 | 0.861 | 0.492 |

| VOCs | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-nonanal-M | 0.730(0.626 - 0.834) | 60.9 | 84.8 | .000 |

| 1-nonanal-D | 0.757(0.657 - 0.857) | 32.6 | 89.1 | .000 |

| 1-pentanal | 0.318(0.210 - 0.427) | 0 | 97.8 | .003 |

| 1-octanal | 0.666(0.554 - 0.778) | 4.3 | 100 | .006 |

| 2-butenal,2-methyl | 0.355(0.243 - 0.467) | 0 | 97.8 | .016 |

| 3-methylbutylpropanoate-M | 0.288(0.184- 0.392) | 0 | 97.8 | .000 |

| 3-methylbutyl propanoate-D | 0.266(0.164 - 0.367) | 2.2 | 87 | .000 |

| (E) -2-nonenal | 0.761(0.662 - 0.860) | 56.5 | 80.4 | .000 |

| allyl disulfide | 0.644(0.528 - 0.760) | 2.2 | 97.8 | .017 |

| ethyl acrylate | 0.348(0.236- 0.460) | 0 | 97.8 | .012 |

| Unk2 | 0.268(0.164- 0.372) | 4.3 | 89.1 | .000 |

| Unk3 | 0.261(0.158-0.363) | 0 | 97.8 | .000 |

| Unk4 | 0.750(0.652-0.849) | 2.2 | 100 | .000 |

| Unk12 | 0.380(0.264 - 0.495) | 2.2 | 100 | .047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).