Submitted:

18 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Sample Collection

2.2. Sample Processing

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Analysis

2.5. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Profiling

2.6. Statistics and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Features of Gallbladder Cancer and Benign Biliary Pathology Patients

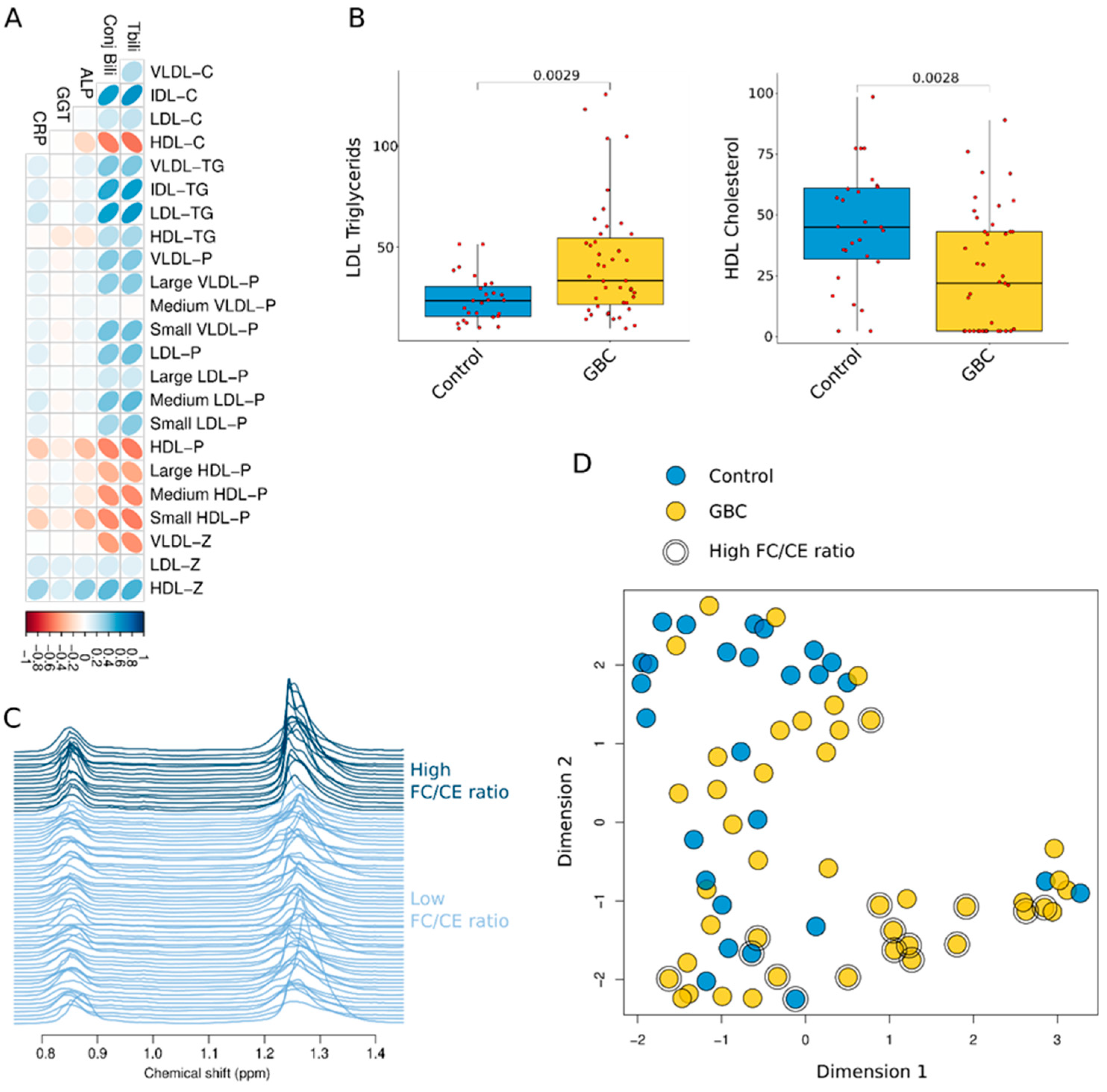

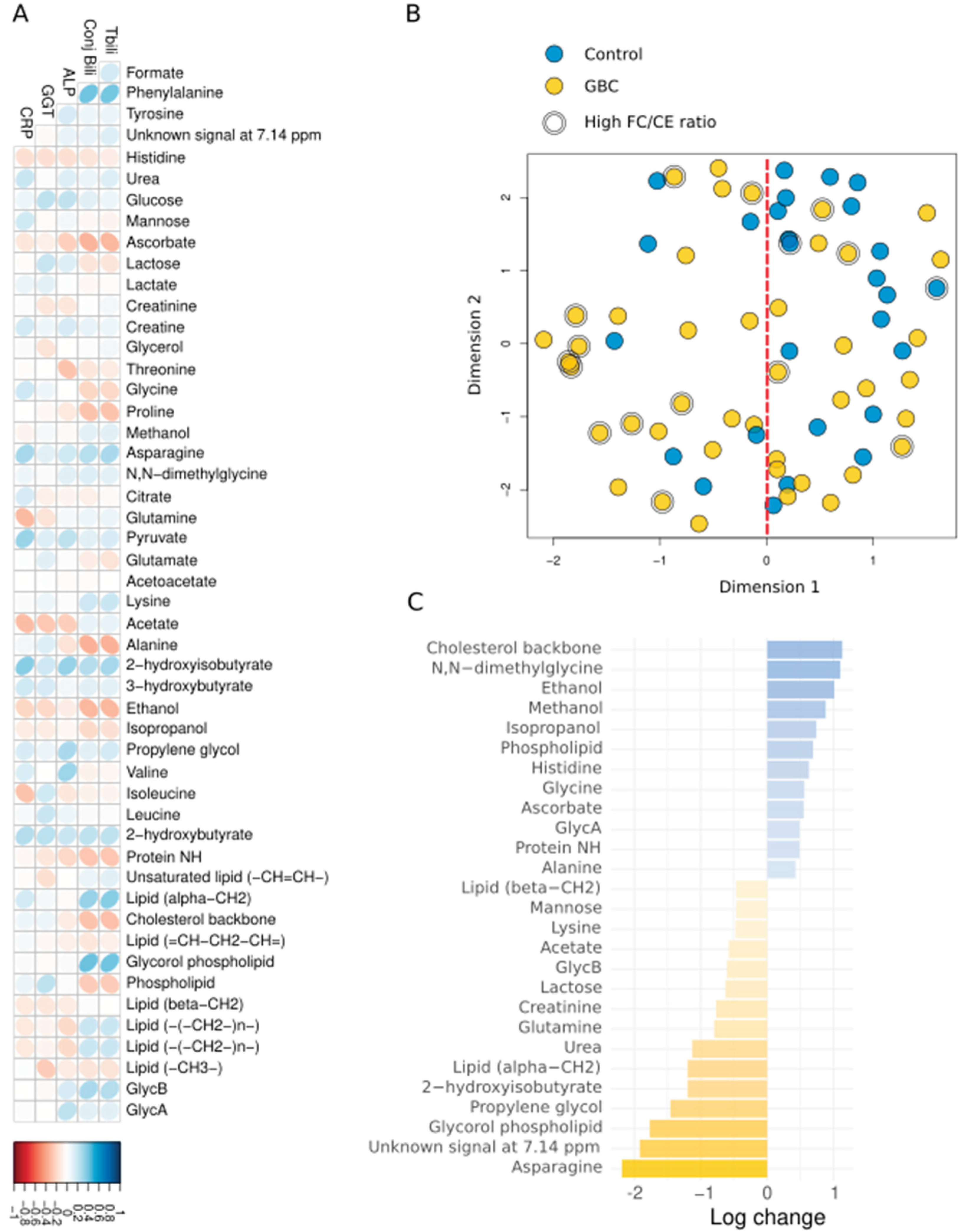

3.2. Dysregulated Metabolites and Lipoproteins in Gallbladder Cancer Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GBC | Gallbladder Cancer |

| BBP | Benign Biliary Pathologies |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| VLDL | Very-Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| PPM | PARTS PER MILLION |

References

- Waller, Giacomo C., and Umut Sarpel. 2024. Gallbladder Cancer. Surgical Clinics of North America 104: 1263–1280. [CrossRef]

- Bray, Freddie, Jacques Ferlay, Isabelle Soerjomataram, Rebecca L. Siegel, Lindsey A. Torre, and Ahmedin Jemal. 2018. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 68: 394–424. [CrossRef]

- Torre, Lindsey A., Rebecca L. Siegel, Farhad Islami, Freddie Bray, and Ahmedin Jemal. 2018. Worldwide Burden of and Trends in Mortality From Gallbladder and Other Biliary Tract Cancers. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16: 427–437. [CrossRef]

- Abdu, Seid Mohammed, and Ebrahim Msaye Assefa. 2025. Prevalence of gallstone disease in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Gastroenterology 12: e001441. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Zafar Ahmed, Muhammed Uzayr Khan, and Martin Brand. 2022. Gallbladder cancer in Africa: A higher than expected rate in a “low-risk” population. Surgery 171: 855–858. [CrossRef]

- Siddamreddy, Suman, Sreenath Meegada, Anum Syed, Mujtaba Sarwar, and Vijayadershan Muppidi. 2020. Gallbladder Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: A Rare Endocrine Tumor. Cureus 12: e7487. [CrossRef]

- Rawla, Prashanth, Tagore Sunkara, Krishna Chaitanya Thandra, and Adam Barsouk. 2019. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer. Clinical and Experimental Hepatology 5: 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Tirca, Luiza, Catalin Savin, Cezar Stroescu, Irina Balescu, Sorin Petrea, Camelia Diaconu, Bogdan Gaspar, Lucian Pop, Valentin Varlas, Adrian Hasegan, and et al. 2024. Risk Factors and Prognostic Factors in GBC. Journal of Clinical Medicine 13: 4201. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yanzhao, Kun Yuan, Yi Yang, Zemin Ji, Dezheng Zhou, Jingzhong Ouyang, Zhengzheng Wang, Fuqiang Wang, Chang Liu, Qingjun Li, and et al. 2023. Gallbladder cancer: current and future treatment options. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, Eldon, and Rajveer Hundal. 2014. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clinical Epidemiology 6: 99–109. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt MA, Marcano-Bonilla L, Roberts LR. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and genetic risk associations. Chin Clin Oncol Vol 8 No 4 August 27 2019 Chin Clin Oncol Gallbladder Cancer 2019.

- Raza, Syed Ahsan., Wilson L. da Costa, and Aaron P. Thrift. 2022. Increasing Incidence of Gallbladder Cancer among Non-Hispanic Blacks in the United States: A Birth Cohort Phenomenon. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 31: 1410–1417. [CrossRef]

- Baichan, Pavan, Previn Naicker, Tanya Nadine Augustine, Martin Smith, Geoffrey Candy, John Devar, and Ekene Emmanuel Nweke. 2023. Proteomic analysis identifies dysregulated proteins and associated molecular pathways in a cohort of gallbladder cancer patients of African ancestry. Clinical Proteomics 20: 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Elebo, Nnenna, Jones Omoshoro-Jones, Pascaline N. Fru, John Devar, Christiaan De Wet van Zyl, Barend Christiaan Vorster, Martin Smith, Stefano Cacciatore, Luiz F. Zerbini, Geoffrey Candy, and et al. 2021. Serum Metabolomic and Lipoprotein Profiling of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients of African Ancestry. Metabolites 11: 663. [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko, Jeanet, Nnenna Elebo, Aurelia A. Williams, Jones Omoshoro-Jones, John W. Devar, Martin Smith, Stefano Cacciatore, and Pascaline N. Fru. 2024. Metabolites and Lipoproteins May Predict the Severity of Early Acute Pancreatitis in a South African Cohort. Biomedicines 12: 2431. [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, Stefano, Martha Wium, Cristina Licari, Aderonke Ajayi-Smith, Lorenzo Masieri, Chanelle Anderson, Azola Samkele Salukazana, Lisa Kaestner, Marco Carini, Giuseppina M. Carbone, and et al. 2021. Inflammatory metabolic profile of South African patients with prostate cancer. Cancer & Metabolism 9: 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Elia, Ilaria, and Marcia C. Haigis. 2021. Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: from cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism. Nature Metabolism 3: 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Du, Yanzhang, Wennie A. Wijaya, and Wei Hui Liu. 2024. Advancements in metabolomics research in benign gallbladder diseases: A review. Medicine 103: e38126. [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, Kanchan, Anu Behari, V. K. Kapoor, and Neeraj Sinha. 2012. 1H NMR metabolic profiling of human serum associated with benign and malignant gallstone diseases. Metabolomics 9: 515–528. [CrossRef]

- Alam, Mohammad Shaha, A.K.M. Harun-Ar-Rashid, Md. Nazrul Islam, and Fatima Jannat. 2021. The Association of the Serum Lipid Abnormalities in Cholelithiasis Patients. Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences 9: 109–112. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, Sikandar, Zarbakht Hassan, Shabbar Hussain Changazi, Anam Zahra, Muhammad Noman, Muhammad Zain Ul Abdin, Haris Javed, and Armghan Haider Ans. 2019. Comparative analysis of serum lipid profiles in patients with and without gallstones: A prospective cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine & Surgery 42: 11–13. [CrossRef]

- Harris, Paul A., Robert Taylor, Robert Thielke, Jonathon Payne, Nathaniel Gonzalez, and Jose G. Conde. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42: 377–381. [CrossRef]

- Elebo, Nnenna, Ebtesam A. Abdel-Shafy, Jones A. O. Omoshoro-Jones, Zanele Nsingwane, Ahmed A. A. Hussein, Martin Smith, Geoffrey Candy, Stefano Cacciatore, Pascaline Fru, and Ekene Emmanuel Nweke, and et al. 2024. Comparative immune profiling of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression among South African patients. BMC Cancer 24: 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Sofia C., Joana Sousa, Fernanda Silva, Margarida Silveira, António Guimarães, Jacinta Serpa, Ana Félix, and Luís G. Gonçalves. 2023. Peripheral Blood Serum NMR Metabolomics Is a Powerful Tool to Discriminate Benign and Malignant Ovarian Tumors. Metabolites 13: 989. [CrossRef]

- Serkova, Natalie, T. Florian Fuller, Jost Klawitter, Chris E. Freise, and Claus U. Niemann. 2005. 1H-NMR–based metabolic signatures of mild and severe ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat kidney transplants. Kidney International 67: 1142–1151. [CrossRef]

- Otvos, James D, Irina Shalaurova, Justyna Wolak-Dinsmore, Margery A Connelly, Rachel H Mackey, James H Stein, and Russell P Tracy. 2015. GlycA: A Composite Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Biomarker of Systemic Inflammation. Clinical Chemistry 61: 714–723. [CrossRef]

- Mallol, Roger, Núria Amigó, Miguel Angel Rodriguez, Mercedes Heras, Maria Vinaixa, Núria Plana, Edmond Rock, Josep Ribalta, Oscar Yanes, Lluís Masana, and et al. 2015. Liposcale: a novel advanced lipoprotein test based on 2D diffusion-ordered 1H NMR spectroscopy. Journal of Lipid Research 56: 737–746. [CrossRef]

- Jeyarajah, Elias J., William C. Cromwell, and James D. Otvos. 2006. Lipoprotein Particle Analysis by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Clinics In Laboratory Medicine 26: 847–870. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Tomàs, Elisabet, Mauricio Murcia, Meritxell Arenas, Mònica Arguís, Miriam Gil, Núria Amigó, Xavier Correig, Laura Torres, Sebastià Sabater, Gerard Baiges-Gayà, and et al. 2019. Serum Paraoxonase-1-Related Variables and Lipoprotein Profile in Patients with Lung or Head and Neck Cancer: Effect of Radiotherapy. Antioxidants 8: 213. [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, Stefano, Leonardo Tenori, Claudio Luchinat, Phillip R Bennett, David A MacIntyre, and Jonathan Wren. 2016. KODAMA: an R package for knowledge discovery and data mining. Bioinformatics 33: 621–623. [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, Stefano, Claudio Luchinat, and Leonardo Tenori. 2014. Knowledge discovery by accuracy maximization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 5117–5122. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy EA, Kassim M, Vignoli A, Mamdouh F, Tyekucheva S, Ahmed D, et al. KODAMA enables self-guided weakly supervised learning in spatial transcriptomics. BioRxiv 2025:2025–05.

- Shah R, Grant LM, John S. Cholestatic Jaundice. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2025.

- Kim, Eun-Sook, Sun Young Kim, and Aree Moon. 2023. C-Reactive Protein Signaling Pathways in Tumor Progression. Biomolecules & Therapeutics 31: 473–483. [CrossRef]

- Caputo, Fabio, Matteo Guarino, Alberto Casabianca, Lisa Lungaro, Anna Costanzini, Giacomo Caio, Giorgio Zoli, and Roberto De Giorgio. 2024. Effects of Ethanol on the Digestive System: A Narrative Review. Journal of Translational Gastroenterology 000: 000–000. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Hiroshi, Kumie Ito, Daisuke Manita, Ryo Sato, Chika Hiraishi, Sadako Matsui, and Yuji Hirowatari. 2021. Clinical Significance of Intermediate-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Determination as a Predictor for Coronary Heart Disease Risk in Middle-Aged Men. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 8. [CrossRef]

- Maran, Logeswaran, Auni Hamid, Shahrul Bariyah Sahul Hamid, and Philip W. Wertz. 2021. Lipoproteins as Markers for Monitoring Cancer Progression. Journal of Lipids 2021: 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, Dominique, Aurélie Mialhe, Alexia K. Cotte, Jean-Louis Connat, Florence Bouyer, François Hermetet, and Virginie Aires. 2025. Lipid metabolism in cancer: Exploring phospholipids as potential biomarkers. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 187: 118095. [CrossRef]

- Feingold KR. Introduction to Lipids and Lipoproteins. MDText.com, Inc., South Dartmouth (MA); 2000.

- Madaudo, Cristina, Giada Bono, Antonella Ortello, Giuseppe Astuti, Giulia Mingoia, Alfredo Ruggero Galassi, and Vincenzo Sucato. 2024. Dysfunctional High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Coronary Artery Disease: A Narrative Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine 14: 996. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Xiao, Weihua Zhang, Song Li, and Hui Yang. 2019. The role of cholesterol metabolism in cancer. 9: 219–227.

- Rajamäki, Kristiina, Jani Lappalainen, Katariina Öörni, Elina Välimäki, Sampsa Matikainen, Petri T. Kovanen, Kari K. Eklund, and Derya Unutmaz. 2010. Cholesterol Crystals Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Human Macrophages: A Novel Link between Cholesterol Metabolism and Inflammation. PLOS ONE 5: e11765–e11765. [CrossRef]

| Feature |

Control (BBP) (n=27) |

GBC (n=43) |

p-value |

| Age (year), median [IQR] | 53 [42 66] | 61.5 [55.75 72] | 0.0795 |

| Gender | 0.610 | ||

| Female, n (%) | 18 (66.7) | 23 (57.5) | |

| Male, n (%) | 9 (33.3) | 17 (42.5) | |

| Total bilirubin, median [IQR] | 16.5 [12 31] | 216.5 [93.5 322.75] | <0.001 |

| Conjugated bilirubin, median [IQR] | 13.5 [4.75 26] | 174.5 [76.25 252.75] | <0.001 |

| ALP, median [IQR] | 308.5 [127.25 499.25] | 564 [323.25 909.25] | 0.0396 |

| GGT, median [IQR] | 452 [159 612] | 490 [234 693.5] | 0.436 |

| CRP, median [IQR] | 22.5 [7.25 83.25] | 74 [40 191] | 0.0234 |

| Feature |

Control (BBP) median [IQR] |

GBC median [IQR] |

p-value | FDR |

| VLDL-C (nmol/L) | 16.80 [8.45 21.14] | 17.39 [9.83 26.65] | 0.356 | 0.431 |

| IDL-C (nmol/L) | 16.74 [10.03 23.09] | 31.39 [15.60 54.00] | 0.004 | 0.016 |

| LDL-C (nmol/L) | 128.24 [111.14 151.88] | 135.07 [108.15 158.03] | 0.596 | 0.623 |

| HDL-C (nmol/L) | 45.05 [31.93 61.11] | 21.96 [2.33 43.16] | 0.003 | 0.014 |

| VLDL-TG (nmol/L) | 58.23 [41.02 80.58] | 72.52 [54.64 103.61] | 0.122 | 0.227 |

| IDL-TG (nmol/L) | 16.54 [10.44 19.51] | 21.76 [13.97 37.01] | 0.008 | 0.028 |

| LDL-TG (nmol/L) | 23.69 [15.76 30.69] | 33.52 [21.67 54.59] | 0.003 | 0.014 |

| HDL-TG (nmol/L) | 16.75 [13.19 22.18] | 18.77 [14.13 23.88] | 0.469 | 0.539 |

| VLDL-P (nmol/L) | 43.80 [29.76 59.27] | 51.90 [38.16 74.81] | 0.138 | 0.227 |

| Large VLDL-P (nmol/L) | 0.99 [0.77 1.38] | 1.29 [0.90 1.62] | 0.158 | 0.227 |

| Medium VLDL-P (nmol/L) | 4.57 [3.59 6.19] | 5.06 [3.60 6.64] | 0.699 | 0.699 |

| Small VLDL-P (nmol/L) | 37.02 [26.24 52.90] | 47.74 [32.25 65.59] | 0.144 | 0.227 |

| LDL-P (nmol/L) | 1342.60 [1108.71 1514.31] | 1507.93 [1181.12 1871.08] | 0.087 | 0.199 |

| Large LDL-P (nmol/L) | 211.87 [175.09 248.48] | 229.47 [165.51 280.72] | 0.341 | 0.431 |

| Medium LDL-P (nmol/L) | 457.87 [325.68 610.36] | 657.09 [429.20 841.00] | 0.031 | 0.079 |

| Small LDL-P (nmol/L) | 642.81 [547.50 731.08] | 668.13 [558.67 754.12] | 0.554 | 0.607 |

| HDL-P (mol/L) | 22.67 [13.70 31.15] | 13.21 [5.18 22.18] | 0.002 | 0.014 |

| Large HDL-P (mol/L) | 0.30 [0.26 0.35] | 0.27 [0.21 0.34] | 0.141 | 0.227 |

| Medium HDL-P (mol/L) | 9.98 [9.47 12.17] | 8.72 [6.28 11.39] | 0.013 | 0.039 |

| Small HDL-P (mol/L) | 12.35 [2.43 20.22] | 4.06 [0.07 9.99] | 0.003 | 0.014 |

| VLDL-Z (nm) | 42.19 [42.17 42.22] | 42.18 [42.16 42.20] | 0.334 | 0.431 |

| LDL-Z (nm) | 21.28 [21.16 21.50] | 21.41 [21.17 21.57] | 0.155 | 0.227 |

| HDL-Z (nm) | 8.40 [8.31 8.92] | 8.76 [8.53 9.56] | 0.003 | 0.014 |

| Feature | BBP (median [IQR]) | GBC (median [IQR]) | p-value | FDR |

| Formate | 0.01 [0.01 0.02] | 0.02 [0.01 0.02] | 0.499 | 0.713 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.14 [0.09 0.23] | 0.26 [0.14 0.33] | 0.013 | 0.276 |

| Tyrosine | 0.08 [0.05 0.12] | 0.08 [0.04 0.12] | 0,828 | 0.920 |

| Unknown signal at 7.14 ppm | 0 [0 0.02] | 0.01 [0 0.10] | 0.044 | 0.276 |

| Histidine | 0.07 [0.03 0.09] | 0.06 [0.02 0.08] | 0.138 | 0.459 |

| Urea | 0.26 [0.11 0.45] | 0.25 [0.15 0.34] | 0.894 | 0.932 |

| Glucose | 1.89 [1.40 2.40] | 1.71 [0.91 2.34] | 0.579 | 0.762 |

| Mannose | 0.04 [0.02 0.06] | 0.04 [0.02 0.06] | 0.933 | 0.942 |

| Ascorbate | 0.01 [0 0.01] | 0 [0 0.004] | 0.243 | 0.534 |

| Lactose | 0.02 [0.01 0.03] | 0.02 [0.01 0.03] | 0.476 | 0.700 |

| Lactate | 1.64 [0.80 2.19] | 1.44 [0.91 2.38] | 0.942 | 0.942 |

| Creatinine | 0.11 [0.05 0.13] | 0.12 [0.07 0.15] | 0.278 | 0.534 |

| Creatine | 0.03 [0.02 0.06] | 0.06 [0.02 0.09] | 0.162 | 0.475 |

| Glycerol | 0.27 [0.12 0.33] | 0.23 [0.08 0.36] | 0.625 | 0.765 |

| Threonine | 0.18 [0.10 0.24] | 0.10 [0.07 0.15] | 0.021 | 0.276 |

| Glycine | 0.72 [0.58 0.92] | 0.58 [0.27 0.76] | 0.038 | 0.276 |

| Proline | 0.12 [0.02 0.22] | 0.06 [0.02 0.14] | 0.149 | 0.464 |

| Methanol | 0.06 [0.04 0.09] | 0.05 [0.02 0.10] | 0.419 | 0.654 |

| Asparagine | 0 [0 0.01] | 0.006 [0 0.02] | 0.022 | 0.276 |

| N,N-dimethylglycine | 0.02 [0.01 0.04] | 0.03 [0.01 0.05] | 0.278 | 0.534 |

| Citrate | 0.09 [0.02 0.23] | 0.04 [0 0.16] | 0.267 | 0.534 |

| Glutamine | 0.34 [0.22 0.51] | 0.33 [0.14 0.54] | 0.642 | 0.765 |

| Pyruvate | 0.06 [0.03 0.1] | 0.11 [0.04 0.19] | 0.030 | 0.276 |

| Glutamate | 0.42 [0.27 0.81] | 0.39 [0.21 0.73] | 0.530 | 0.717 |

| Acetoacetate | 0.13 [0.08 0.20] | 0.1 [0.05 0.20] | 0.334 | 0.567 |

| Lysine | 0.02 [0.01 0.03] | 0.02 [0.01 0.03] | 0.847 | 0.921 |

| Acetate | 0.10 [0.06 0.13] | 0.09 [0.05 0.13] | 0.523 | 0.717 |

| Alanine | 1.06 [0.39 1.30] | 0.78 [0.38 1.08] | 0.197 | 0.534 |

| 2-hydroxyisobutyrate | 0.01 [0.002 0.02] | 0.01 [0.004 0.02] | 0.340 | 0.567 |

| 3-hydroxybutyrate | 0.18 [0.01 0.68] | 0.19 [0.11 0.62] | 0.299 | 0.534 |

| Ethanol | 0.55 [0.13 1.23] | 0 [0 0.31] | <0.001 | 0.033 |

| Isopropanol | 0.07 [0.001 0.27] | 0 [0 0.13] | 0.073 | 0.367 |

| Propylene glycol | 0.01 [0 0.02] | 0.01 [0 0.03] | 0.622 | 0.765 |

| Valine | 0.38 [0.23 0.50] | 0.43 [0.17 0.52] | 0.791 | 0.919 |

| Isoleucine | 0.1 [0.03 0.14] | 0.04 [0.01 0.11] | 0.133 | 0.459 |

| Leucine | 0.45 [0.25 0.67] | 0.41 [0.19 0.54] | 0.252 | 0.534 |

| 2-hydroxybutyrate | 0.03 [0 0.05] | 0.05 [0.01 0.09] | 0.095 | 0.432 |

| Protein NH | 130.19 [59.36 160.12] | 123.42 [58.31 143.17] | 0.440 | 0.667 |

| Unsaturated lipid (-CH=CH-) | 17.08 [9.57 31.18] | 19.79 [10.97 27.96] | 0.819 | 0.920 |

| Lipid (alpha-CH2) | 3.06 [1.34 4.74] | 3.42 [1.61 8.74] | 0.214 | 0.534 |

| Cholesterol backbone (-C(18)H3), | 2.69 [1.89 3.53] | 1.62 [0.79 2.90] | 0.039 | 0.276 |

| Lipid (=CH-CH2-CH=) | 10.42 [5.84 14.19] | 8.68 [4.55 11.11] | 0.205 | 0.534 |

| Glycorol phospholipid | 0.29 [0.12 0.68] | 0.52 [0.16 1.26] | 0.068 | 0.367 |

| Phospholipid | 4.07 [2.53 5.14] | 3.24 [1.54 4.56] | 0.111 | 0.459 |

| Lipid (beta-CH2) | 15.39 [10.21 17.51] | 11.89 [6.02 19.75] | 0.385 | 0.621 |

| Lipid (-(-CH2-)n-) | 104.28 [45.91 158.99] | 126.27 [59.81 188.26] | 0.294 | 0.534 |

| Lipid (-(-CH2-)n-) | 104.28 [45.91 158.99] | 126.27 [59.81 188.26] | 0.294 | 0.534 |

| Lipid (-CH3-) | 77.767 [34.58 96.66] | 71.65 [32.79 99.77] | 0.875 | 0.931 |

| GlycB | 0.89 [0.48 1.27] | 1.12 [0.75 1.50] | 0.138 | 0.459 |

| GlycA | 4.51 [3.21 5.69] | 4.63 [2.58 7.11] | 0.629 | 0.765 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).