Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

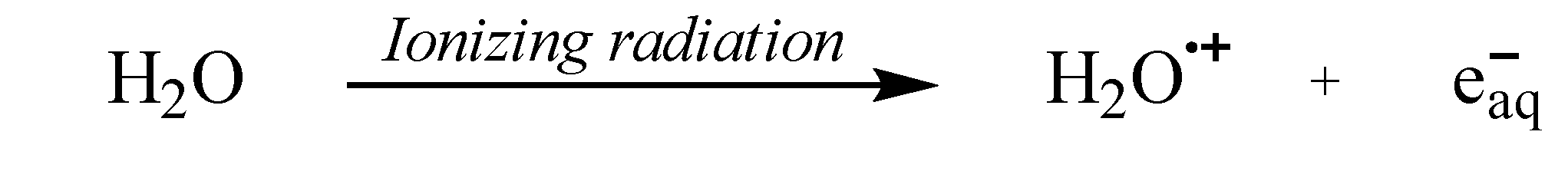

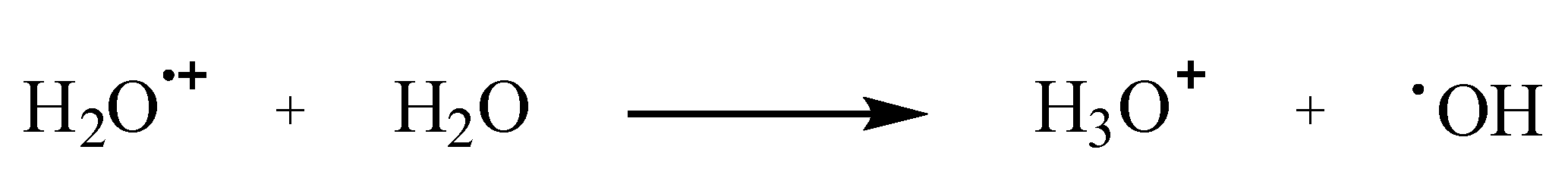

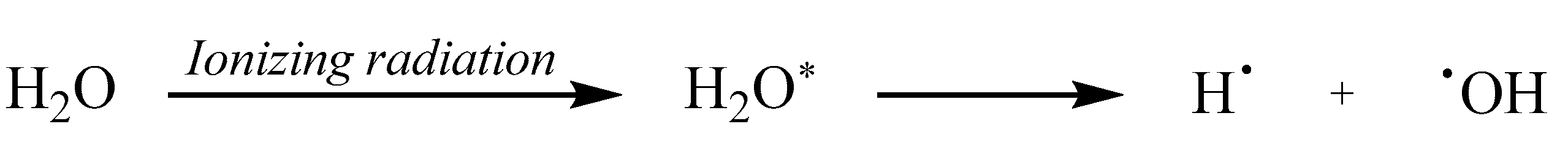

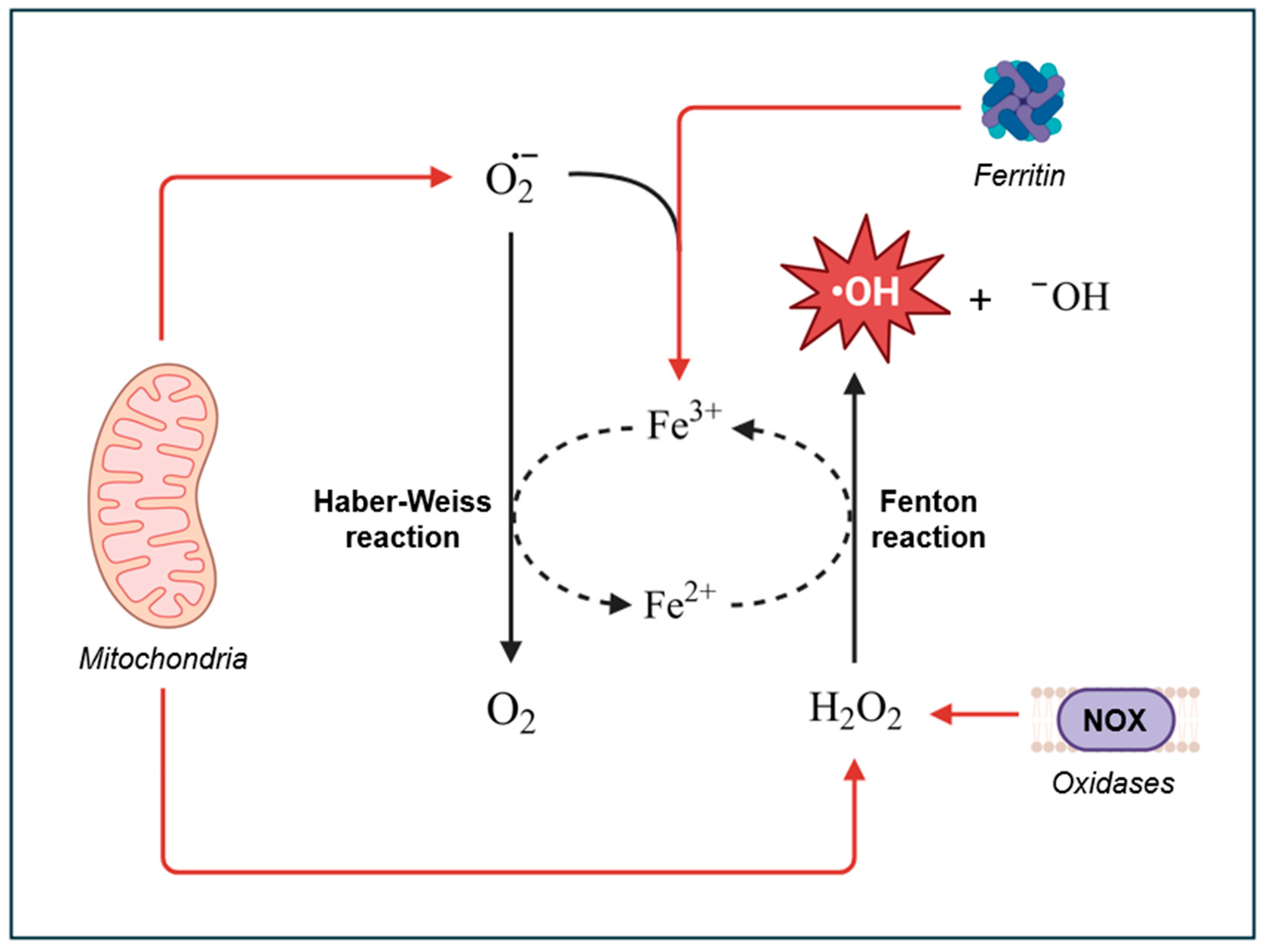

1.1. Mechanisms of Hydroxyl Radical Formation

1.2. Major Intracellular Sources of •OH

1.2.1. The Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain

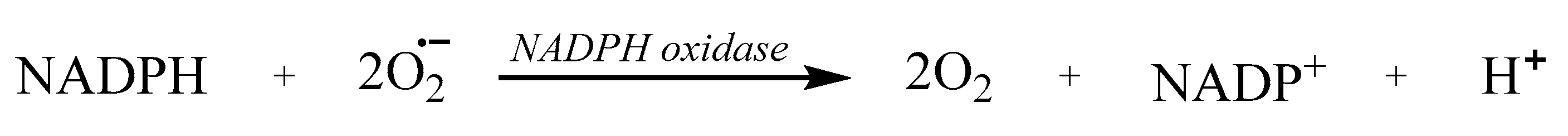

1.2.2. NADPH Oxidases

2. Essential Criteria for Effective Fluorescent Probes in •OH Detection

3. Fluorescence Detection of DNA-associated •OH

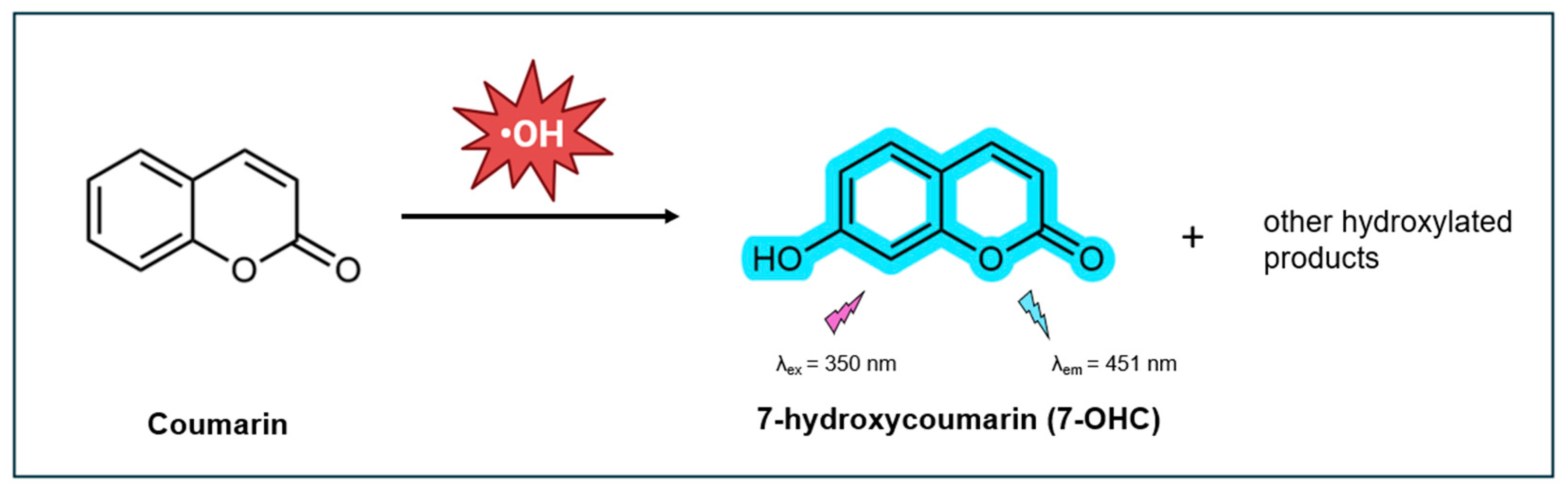

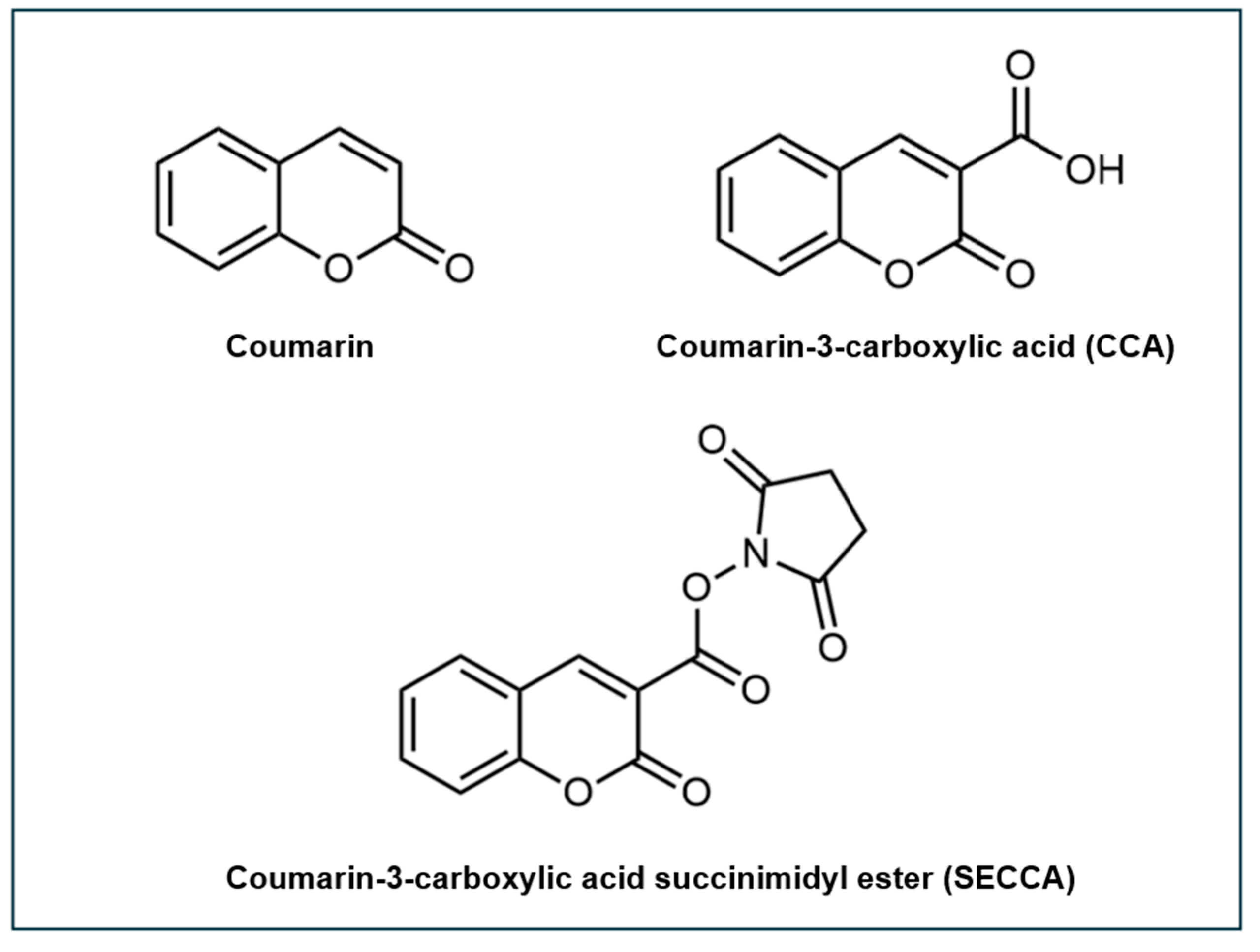

3.1. Coumarin-based Probes

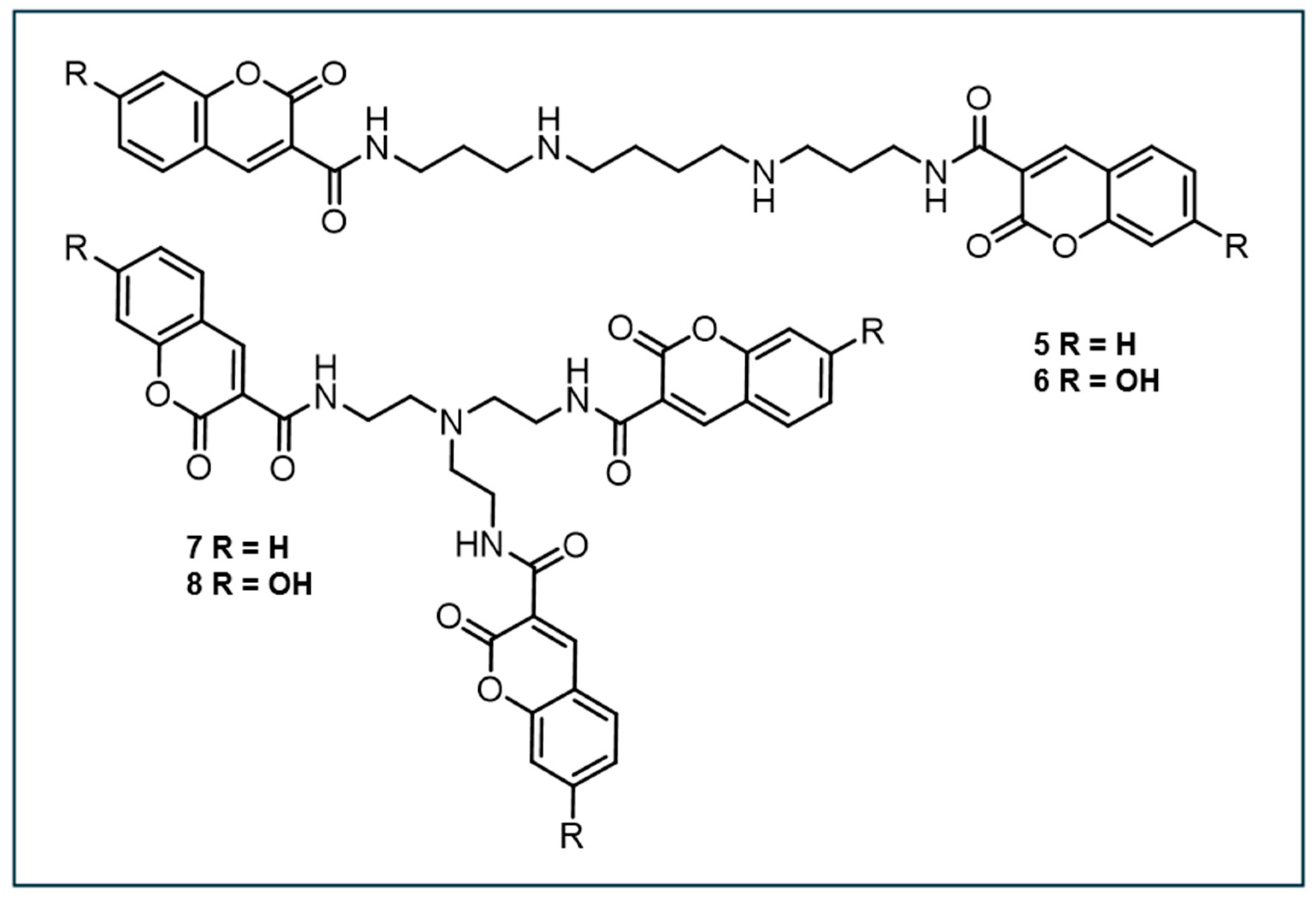

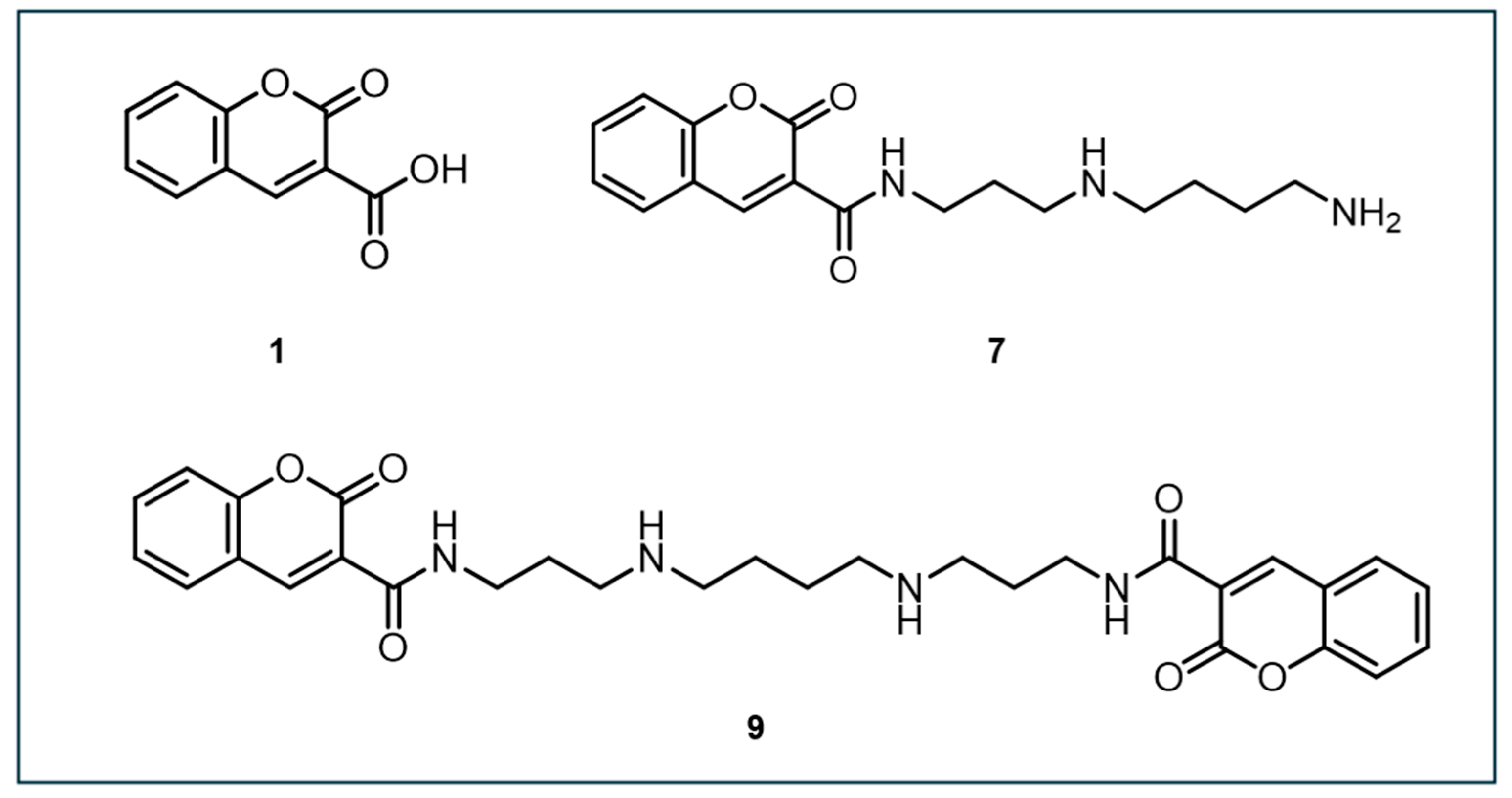

3.2. SECCA-biomolecule Conjugation

3.2.1. SECCA-labeled Histone-H1

3.2.2. SECCA-labeled Polylysines

3.2.3. SECCA-labeled Nucleosomal Histones

3.3. Applications of SECCA-labeled Biomolecules

3.3.1. Detection of Radiation-induced •OH

3.3.2. Detection of Metal-mediated •OH

3.4. Other DNA-targeting Coumarin-based Probes in Development

3.5. Conclusions and Outlook for DNA-targeting Probes

3.5.1. Technical Limitations of Coumarin-based Probes

3.5.2. Probes for Complex Biological Structures

3.5.3. Limitations in Live Cell and In Vivo Applications

4. Fluorescence Detection of Organelle-associated •OH

4.1. Mitochondria-targeted Probes for •OH Detection

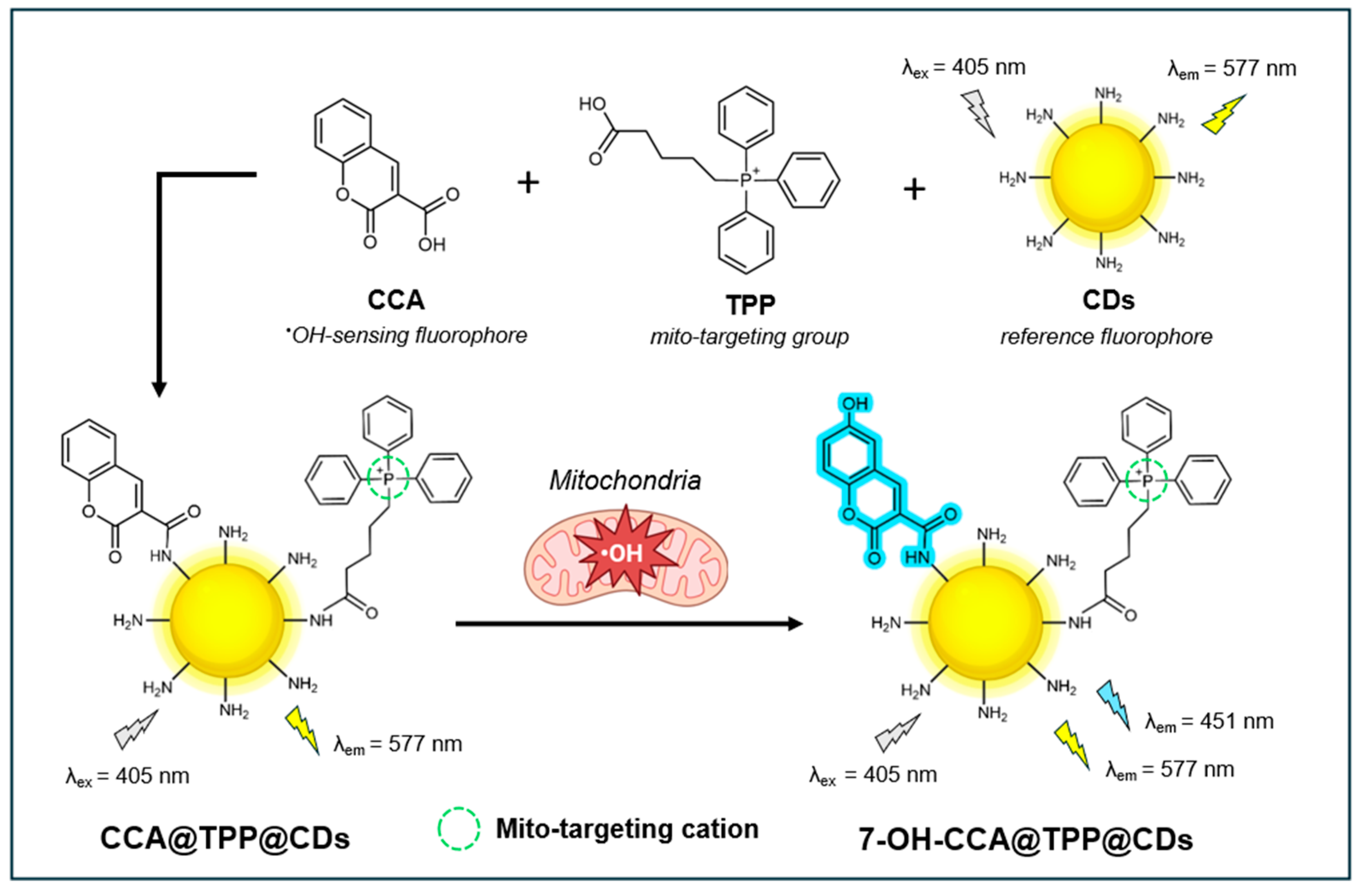

4.1.1. Ratiometric Fluorescence Nanosensor CCA@TPP@CDs

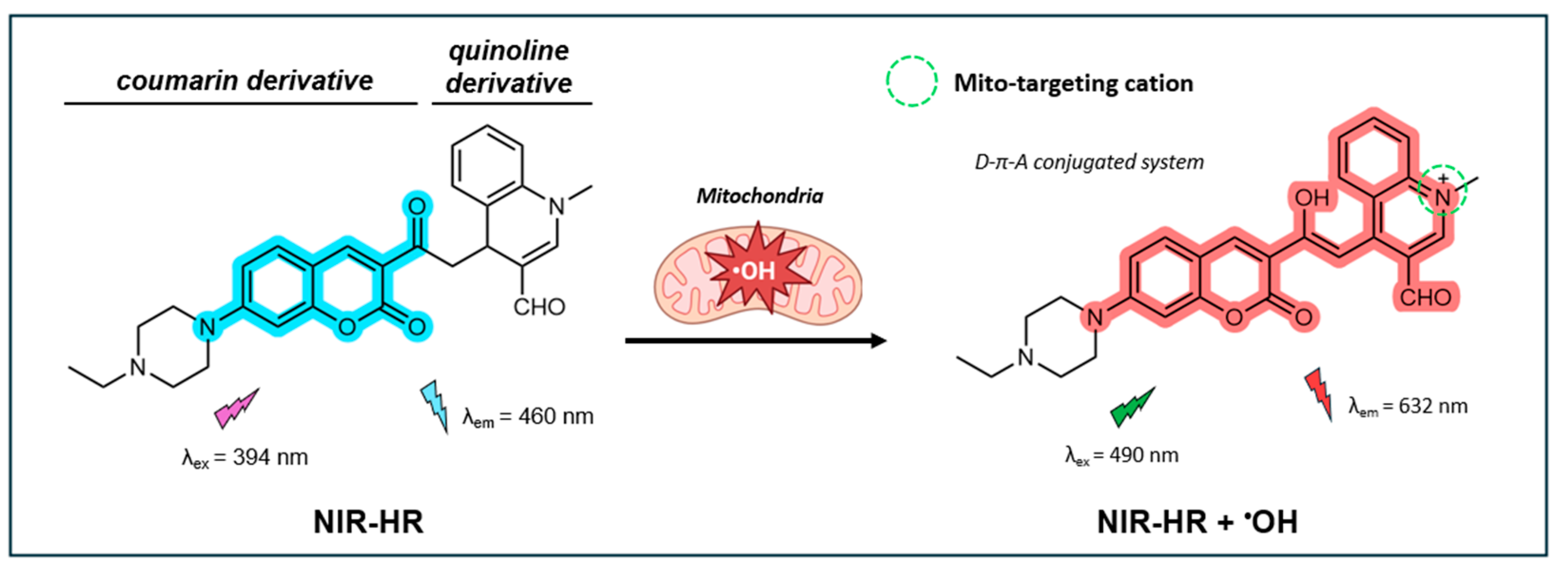

4.1.2. Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe NIR-HR

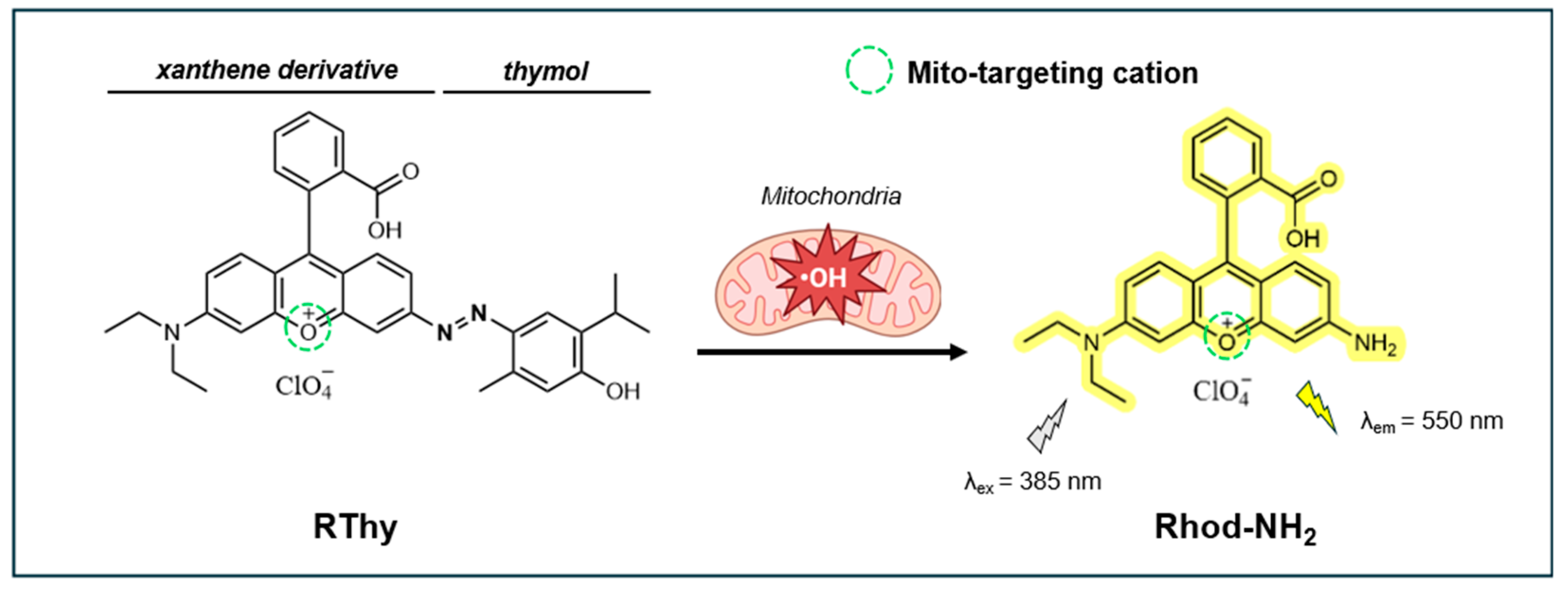

4.1.3. Turn-on Fluorescent Probe RThy

4.2. Lysosome-targeting Fluorescent Probes for •OH Detection

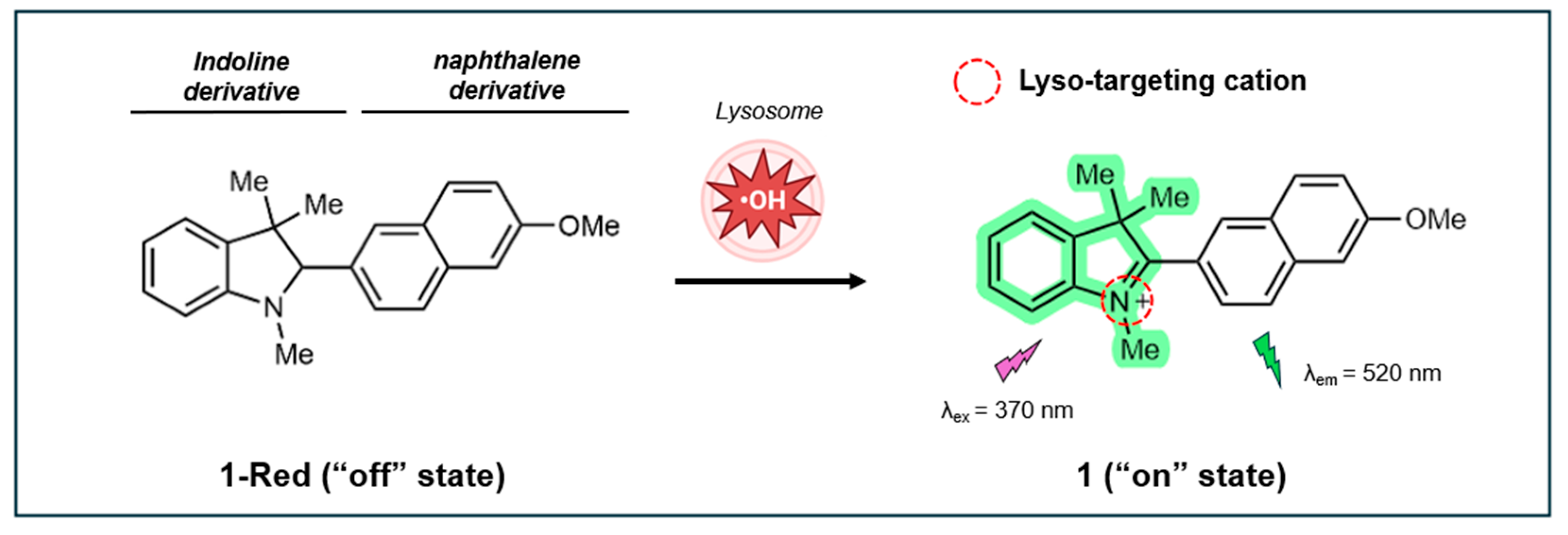

4.2.1. Two-photon Turn-on Fluorescent Probe 1-Red

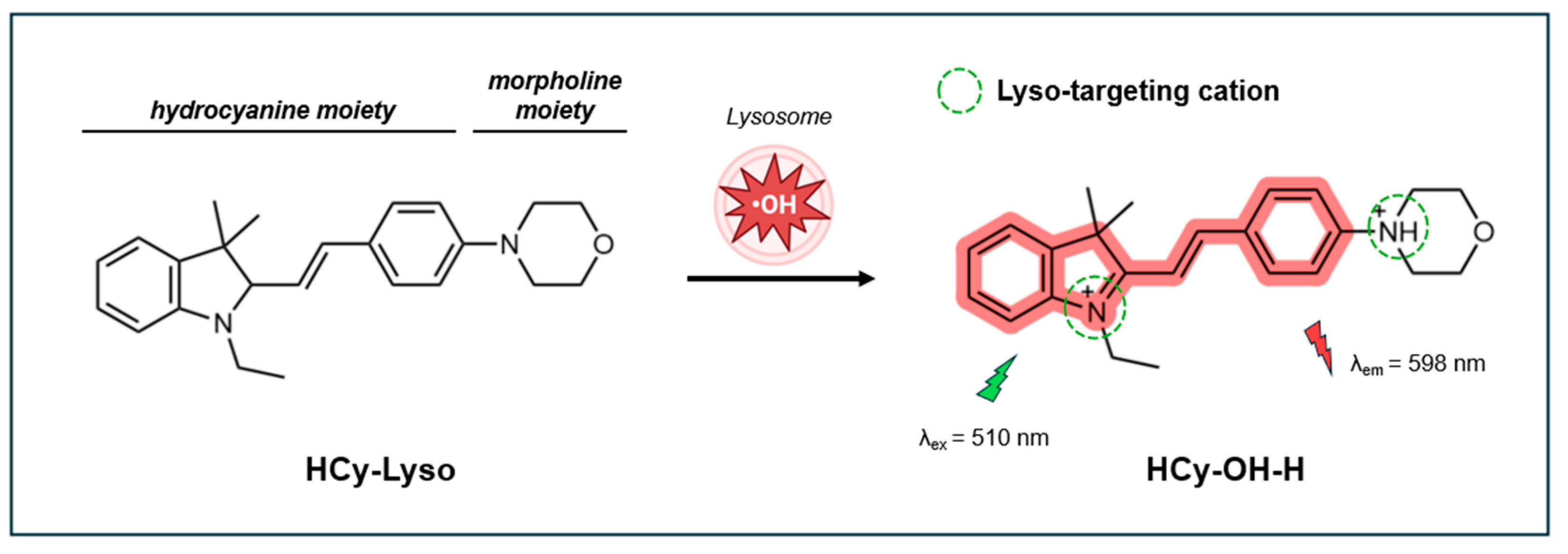

4.2.2. Turn-on Fluorescent Probe HCy-Lyso

4.3. Dual-organelle-targeting Fluorescent Probes for •OH Detection

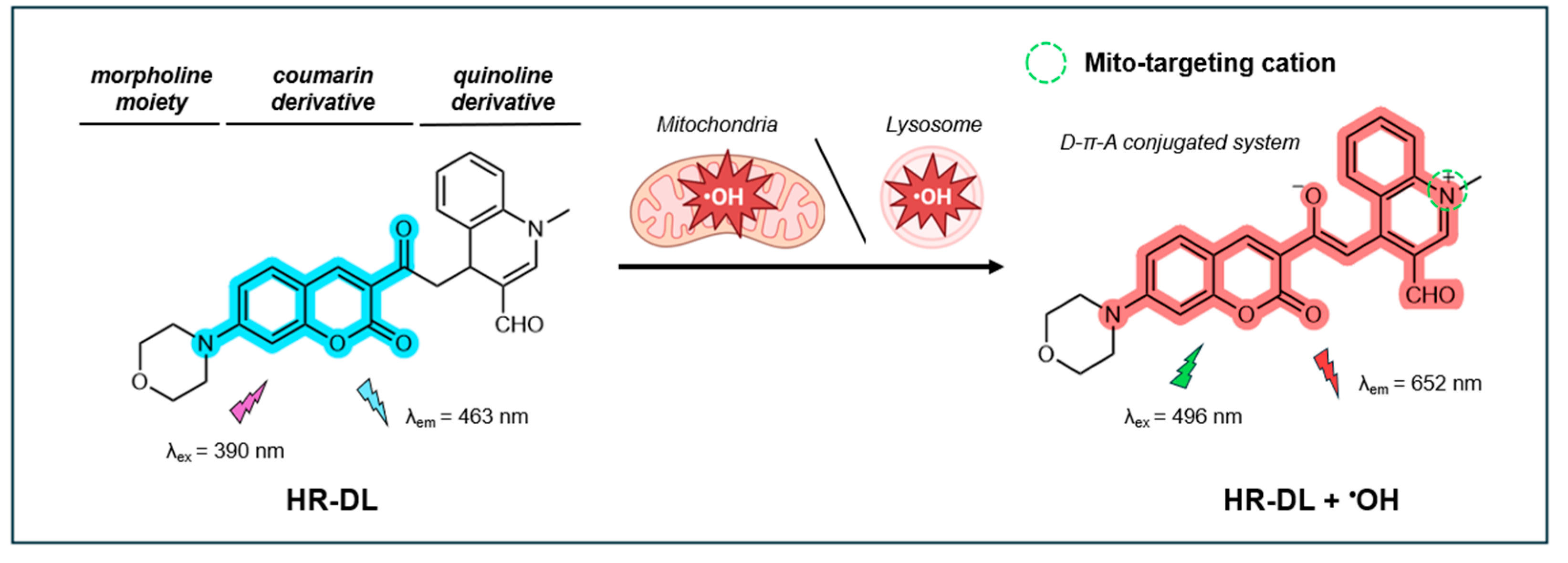

4.3.1. NIR Fluorescent Probe HR-DL

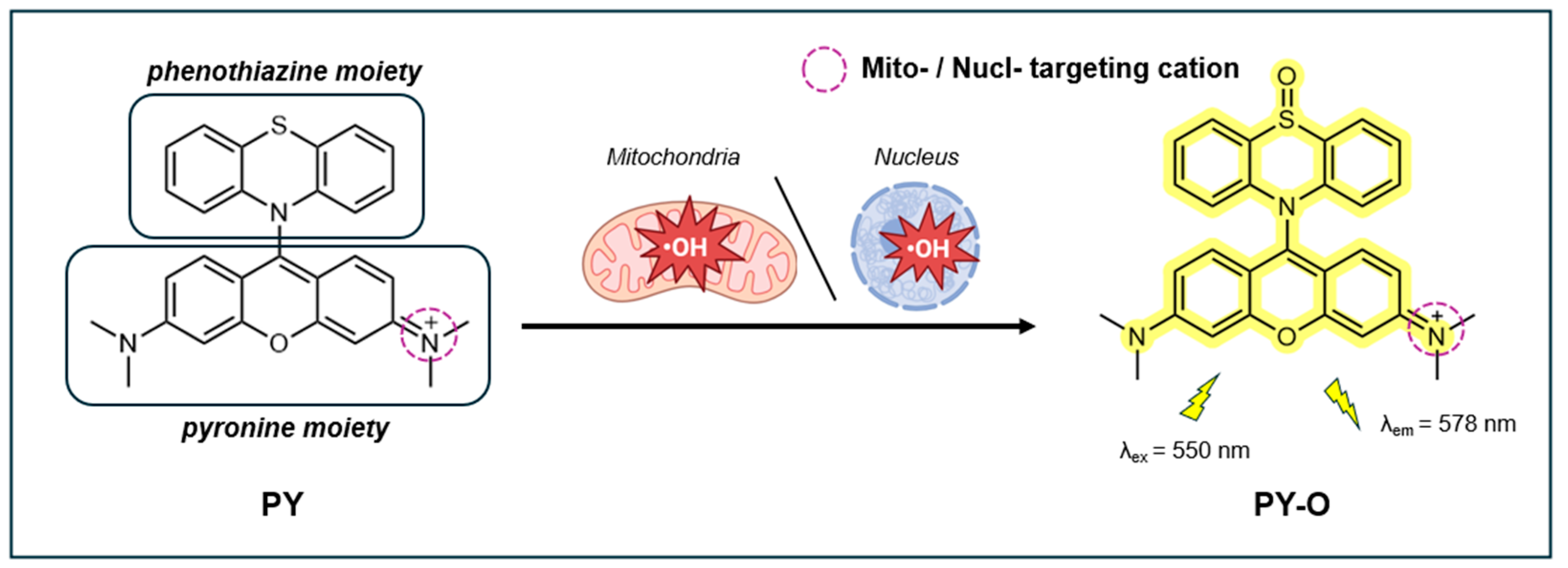

4.3.2. Pyronine-based Fluorescent Probe PY

4.4. Lipid Membrane-targeting Fluorescent Probes for •OH Detection

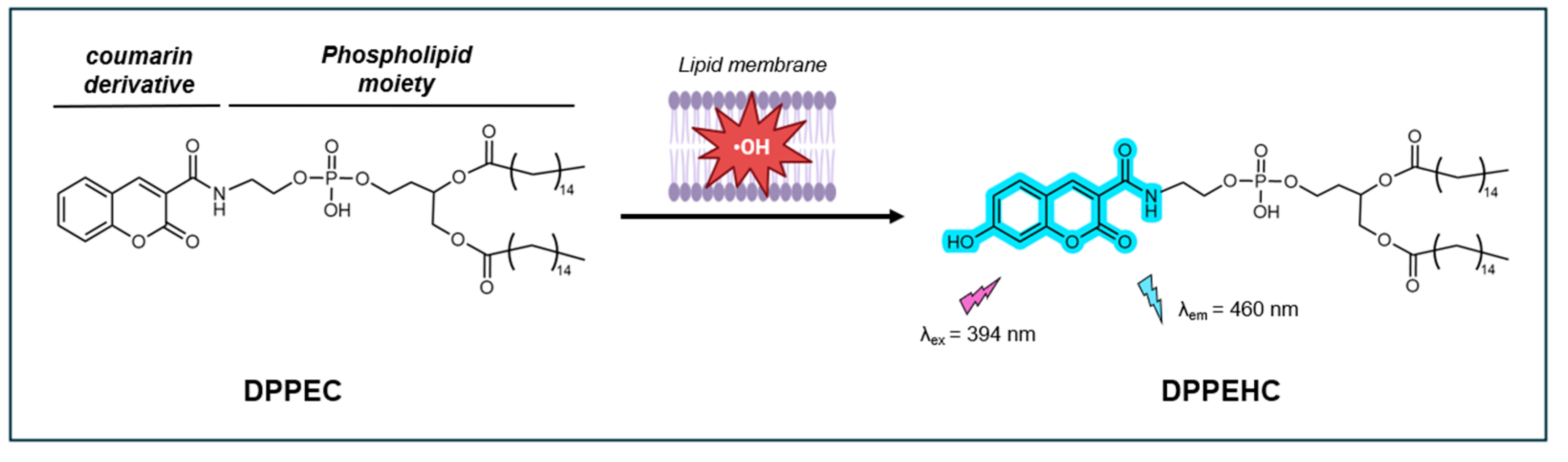

4.4.1. CCA-based Fluorescent Probe DPPEC

4.5. Conclusions and Outlook for Organelle-targeting Probes

4.5.1. Establishing Robust Characterization of Probes

4.5.1. Achieving Target Specificity for Organelles

4.5.2. Enhancing Bioimaging Capabilities

| Ref. | Probe name | Organelle | Targeting group(s) | Key Advantage(s) | Key Limitation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [124] | CCA@TPP@CDs | Mitochondria | TPP * |

|

|

| [127] | NIR-HR | Mitochondria | coumarin-quinoline |

|

|

| [130] | RThy | Mitochondria | Xanthene$$$derivative |

|

|

| [138] | 1-Red | Lysosome | Indoline$$$derivative |

|

|

| [139] | HCy-Lyso | Lysosome | Morpholine |

|

|

| [144] | HR-DL | Mitochondria, $$$lysosome | Quinoline, morpholine |

|

|

| [145] | PY | Mitochondria, nucleoli | Pyronine |

|

|

| [100] | DPPEC | Lipid $$$membrane | DPPE * |

|

|

5. Development of •OH-detecting Probes for Real-Life Biomedical Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free Radicals: Properties, Sources, Targets, and Their Implication in Various Diseases. Indian J Clin Biochem 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J.A. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic Biol Med 2000, 29, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, A.J.; Brand, M.D. Reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria. In Mitochondrial DNA, 2nd ed.; Stuart, J.A., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology™; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 554, pp. 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeshan, H.M.A.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, H.R.; Chae, H.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and associated ROS. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S. Nadph—the forgotten reducing equivalent. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, S.; Reed, T.T.; Venditti, P.; Victor, V.M. Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraci, F.M. Reactive oxygen species: influence on cerebral vascular tone. J Appl Physiol 2006, 100, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, C.-H.; Filosa, S. Effect of Reactive Oxygen Species on the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondria during Intracellular Pathogen Infection of Mammalian Cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Jackson, M.J. Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress: Cellular Mechanisms and Impact on Muscle Force Production. Physiol Rev 2008, 88, 1243–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré-Crochet, S.; Erard, M.; Nüβe, O. ROS production in phagocytes: why, when, and where? J Leukoc Biol 2013, 94, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lushchak, V.I. Free radicals, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and its classification. Chem Biol interact 2014, 224, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, A.L.; Loeb, L.A. The contribution of endogenous sources of DNA damage to the multiple mutations in cancer. Mutat Res 2001, 477, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Jatawa, S.K.; Tiwari, A. Lipid peroxidation: Mechanism, models and significance. Int J Curr Sci 2012, 3, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman, E.R.; Levine, R.L. Protein oxidation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000, 899, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, Y.A.; Rani, R.; Ganie, S.Y.; Sheikh, T.A.; Javaid, D.; Qadri, S.S.; Pramodh, S.; Alsulimani, A.; Alkhanani, M.F.; Harakeh, S.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Hosen, I.; Islam, M.M.T.; Shekhar, H.U. Oxidative stress and human health. Adv Biosci Biotechnol 2012, 3, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Han, C.H.; Lee, M.Y. NADPH oxidase and the cardiovascular toxicity associated with smoking. Toxicol Res 2014, 30, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, J.K.; Tuyle, G.V.; Lin, P.-S.; Schmidt-Ullrich, R.; Mikkelsen, R.B. Ionizing Radiation-induced, Mitochondria-dependent Generation of Reactive Oxygen/Nitrogen 1. Cancer Res 2001, 61, 3894–3901. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Long, Z.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Hai, C. Effect of alcohol on diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic toxicity: Critical role of ROS, lipid accumulation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2015, 67, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, C.L.; Toscano, J.P.; Fukuto, J.M. An Integrated View of the Chemical Biology of NO, CO, H2S, and O2. In Nitric Oxide, 3rd ed.; Ignarro, L.J., Freeman, B.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 9-21.O2. In Nitric Oxide, 3rd ed.; Ignarro, L.J., Freeman, B.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Stanbury, D.M.; Bounds, P.L. Electrode potentials of partially reduced oxygen species, from dioxygen to water. Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 49, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, G.V. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals. J Phys Chem Ref Data 1988, 17, 514–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, R.; Okada, S. Estimation of life times and diffusion distances of radicals involved in X-ray-induced DNA strand breaks or killing of mammalian cells. Radiat Res 1975, 64, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorovski, S.; Strekowski, R.; Barbati, S.; Vione, D. Environmental Implications of Hydroxyl Radicals (•OH). Chem Rev 2015, 115, 13051–13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, H.; Klebanoff, S.J. Hydroxyl Radical Generation by Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes Measured by Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy. J Clin Invest 1979, 64, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Vivar, J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Kennedy, M.C. Mitochondrial aconitase is a source of hydroxyl radical. An electron spin resonance investigation. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 14064–14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, E.; Roa, G.; Hernandez-Servin, J.A.; Romero, R.; Balderas, P.; Natividad, R. Hydroxyl Radicals quantification by UV spectrophotometry. Electrochim Acta 2014, 129, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Quantitative detection of hydroxyl radicals in Fenton system by UV-vis spectrophotometry. Anal Methods 2015, 7, 5447–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, Q. Dimethyl Sulfoxide: An Ideal Electrochemical Probe for Hydroxyl Radical Detection. ACS Sens 2024, 9, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Y. A rapid and sensitive electrochemical sensor for hydroxyl free radicals based on self-assembled monolayers of carboxyl functionalized graphene. J Solid State Electrochem 2019, 23, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, J.-F.; Leu, M.-F.; Yang, T.C. Determination of hydroxyl radicals in an advanced oxidation process with salicylic acid trapping and liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1998, 796, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sui, D.; Zhou, W.; Lu, C. Highly selective chemiluminescence detection of hydroxyl radical via increased π-electron densities of rhodamine B on montmorillonite matrix. Sens Actuators B Chem 2016, 225, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.J.; Rose, A.L.; Waite, T.D. Phthalhydrazide chemiluminescence method for determination of hydroxyl radical production: Modifications and adaptations for use in natural systems. Anal Chem 2011, 83, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganea, G.M.; Kolic, P.E.; El-Zahab, B.; Warner, I.M. Ratiometric coumarin− neutral red (CONER) nanoprobe for detection of hydroxyl radicals. Anal Chem 2011, 83, 2576–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Ding, C.; Zhu, A.; Tian, Y. Ratiometric Fluorescence Probe for Monitoring Hydroxyl Radical in Live Cells Based on Gold Nanoclusters. Anal Chem 2014, 86, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K.; Muhammad, S.; Ju, M.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, B.; Ding, W.; Shen, B.; et al. Fluorogenic toolbox for facile detecting of hydroxyl radicals: From designing principles to diagnostics applications. Trends Analyt Chem 2022, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.; Yong, J.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R. Recent Advances in Detection of Hydroxyl Radical by Responsive Fluorescence Nanoprobes. Chem Asian J 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.T.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Duan, R.; Cao, X.; Yuan, F.; Liao, Y.X.; Wang, S.; Xiu Ren, W. Fluorescent detectors for hydroxyl radical and their applications in bioimaging: A review. Coord Chem Rev 2020, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żamojć, K.; Zdrowowicz, M.; Jacewicz, D.; Wyrzykowski, D.; Chmurzyński, L. Fluorescent and Luminescent Probes for Monitoring Hydroxyl Radical under Biological Conditions. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2016, 46, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.V.; Hanna, P.M.; Mason, R.P. The origin of the hydroxyl radical oxygen in the Fenton reaction. Free Radic Biol Med 1997, 22, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaware, V.; Kotade, K.; Dhamak, K.; Somawanshi, S. Ceruloplasmin its role and significance: a review. Pathol 2010, 5, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, C.M.; Wooten, L.; Cerveza, P.; Cotton, S.; Shulze, R.; Lomeli, N. Copper transport. Am J Clin Nutr 1998, 67, 965S–971S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, H.N. Iron regulation of ferritin gene expression. J Cell Biochem 1990, 44, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plays, M.; Müller, S.; Rodriguez, R. Chemistry and biology of ferritin. Metallomics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Sharma, P.K.; Rao, G.S. Release of iron from ferritin by metabolites of benzene and superoxide radical generating agents. Toxicol 2001, 168, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolann, B.J.; Ulvik, R.J. Release of iron from ferritin by xanthine oxidase Role of the superoxide radical. Biochem J 1987, 243, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.E.; Morehouse, L.A.; Austs, S.D. Ferritin and Superoxide-dependent Lipid Peroxidation. J Biol Chem 1985, 260, 3275–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Ardehali, H.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023, 20, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Gomez, H.; Murugan, R.; Hong, X.; Xu, D.; Jiang, F.; Peng, Z.Y. Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MA, J.; Denisov, S.A.; Adhikary, A.; Mostafavi, M. Ultrafast processes occurring in radiolysis of highly concentrated solutions of nucleosides/tides. J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol 2010, 45, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aon, M.A.; Stanley, B.A.; Sivakumaran, V.; Kembro, J.M.; O'Rourke, B.; Paolocci, N.; Cortassa, S. Glutathione/thioredoxin systems modulate mitochondrial H2O2 emission: An experimental-computational study. J Gen Physiol 2012, 139, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants Maintain Cellular Redox Homeostasis by Elimination of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 44, 532–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, C.B.; Llorente-Folch, I.; Amigo, I.; Contreras, L.; González-Sánchez, P.; Martínez-Valero, P.; Juaristi, I.; Pardo, B.; Del Arco, A.; Satrústegui, J. Ca2+ regulation of mitochondrial function in neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2014, 1837, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, W. Ca2+ homeostasis dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease: a focus on plasma membrane and cell organelles. FASEB J 2019, 33, 6697–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.K.; Gerasimenko, J.V.; Thorne, C.; Ferdek, P.; Pozzan, T.; Tepikin, A.V.; Petersen, O.H.; Sutton, R.; Watson, A.J.M.; Gerasimenko, O.V. Calcium elevation in mitochondria is the main Ca2+ requirement for mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 20796–20803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Rodriguez, M.; Hou, S.S.; Snyder, A.C.; Kharitonova, E.K.; Russ, A.N.; Das, S.; Fan, Z.; Muzikansky, A.; Garcia-Alloza, M.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; et al. Increased mitochondrial calcium levels associated with neuronal death in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, H.; Manfredi, G. Mitochondrial dysfunction and intracellular calcium dysregulation in ALS. Mech Ageing Dev 2010, 131, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santulli, G.; Xie, W.; Reiken, S.R.; Marks, A.R. Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015, 112, 11389–11394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, B.; Shani, G.; Pass, I.; Anderson, D.; Quintavalle, M.; Courtneidge, S.A. Tks5-dependent, nox-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species is necessary for invadopodia formation. Sci Signal 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.A.; Kulawiec, M.; Owens, K.M.; Li, X.; Desouki, M.M.; Chandra, D.; Singh, K.K. NADPH oxidase 4 is an oncoprotein localized to mitochondria. Cancer Biol Ther 2010, 10, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilenski, L.L.; Clempus, R.E.; Quinn, M.T.; Lambeth, J.D.; Griendling, K.K. Distinct Subcellular Localizations of Nox1 and Nox4 in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004, 24, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, J.; Nakagawa, K.; Yamasaki, T.; Nakamura, K.I.; Takeya, R.; Kuribayashi, F.; Imajoh-Ohmi, S.; Igarashi, K.; Shibata, Y.; Sueishi, K.; et al. The superoxide-producing NAD(P)H oxidase Nox4 in the nucleus of human vascular endothelial cells. Genes Cells 2005, 10, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petry, A.; Djordjevic, T.; Weitnauer, M.; Kietzmann, T.; Hess, J.; Gӧrlach, A. NOX2 and NOX4 Mediate Proliferative Response in Endothelial Cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006, 8, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Rizzo, V. TNF-potentiates protein-tyrosine nitration through activation of NADPH oxidase and eNOS localized in membrane rafts and caveolae of bovine aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermot, A.; Petit-Hartlein, I.; Smith, S.M.E.; Fieschi, F. NADPH Oxidases (NOX): An Overview from Discovery, Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology and Pathology. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschnitz, C.; Grund, H.; Wingler, K.; Armitage, M.E.; Jones, E.; Mittal, M.; Barit, D.; Schwarz, T.; Geis, C.; Kraft, P.; et al. Post-stroke inhibition of induced NADPH Oxidase type 4 prevents oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. PLoS Biol 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.; Geng, X.; Li, F.; Ding, Y. NOX activation by subunit interaction and underlying mechanisms in disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Kapoor, M.; Nehru, B. Apocyanin, NADPH oxidase inhibitor prevents lipopolysaccharide induced α-synuclein aggregation and ameliorates motor function deficits in rats: Possible role of biochemical and inflammatory alterations. Behav Brain Res 2016, 296, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fery-Forgues, S.; Lavabre, D. Are Fluorescence Quantum Yields So Tricky to Measure? A Demonstration Using Familiar Stationery Products. J Chem Educ 1999, 76, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteman, M.; Shan Hong, H.; Jenner, A.; Halliwell, B. Loss of oxidized and chlorinated bases in DNA treated with reactive oxygen species: implications for assessment of oxidative damage in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002, 296, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, D.R.; Phillips, D.H.; Carmichael, P.L. Generation of Putative Intrastrand Cross-Links and Strand Breaks in DNA by Transition Metal Ion-Mediated Oxygen Radical Attack. Chem Res Toxicol 1997, 10, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, D.A.; Doda, J.N.; Friedberg, E.C. The Absence of a Pyrimidine Dimer Repair Mechanism in Mammalian Mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1974, 71, 2777–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.; Weinfeld, M.; Murray, D. DNA-protein crosslinks: Their induction, repair, and biological consequences. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 2005, 589, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Greenberg, M.M. λ-radiolysis and hydroxyl radical produce interstrand cross-links in DNA involving thymidine. Chem Res Toxicol 2007, 20, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA by hydroxyl radical and one-electron oxidants: Similarities and differences. Arch Biochem Biophys 2014, 557, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. DNA base damage by reactive oxygen species, oxidizing agents, and UV radiation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randerath, K.; Randerath, E.; Smith, C.V.; Chang, J. Structural Origins of Bulky Oxidative DNA Adducts (Type II I-Compounds) as Deduced by Oxidation of Oligonucleotides of Known Sequence. Chem Res Toxicol 1996, 9, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, A.; Yamamoto, K.I. DNA damage responses to oxidative stress. DNA repair (Amst) 2004, 3, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips, J.; Kaina, B. DNA double-strand breaks trigger apoptosis in p53-deficient fibroblasts Carcinog 2001, 22, 579-585. 22. [CrossRef]

- Varga, T.; Aplan, P.D. Chromosomal aberrations induced by double strand DNA breaks. DNA repair 2005, 4, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gent, D.C.; Hoeijmakers, H.J.; Kanaar, R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat Rev Genet 2001, 2, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malins, D.C.; Polissar, N.L.; Gunselman, S.J. Progression of human breast cancers to the metastatic state is linked to hydroxyl radical-induced DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1996, 93, 2557–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.W.; Lin, T.-S.; Minteer, S.; Burke, W.J. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide generate a hydroxyl radical: possible role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Mol Brain Res 2001, 93, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer's disease. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, 7497–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, M.; Merli, E.; Malagutti, P.; Soukhomovskaia, O.; Cicchitelli, G.; Antelli, A.; Canistro, D.; Francolini, G.; Macrì, G.; Mastrorilli, F.; et al. Hydroxyl radical generation, levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and progression to heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004, 43, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talha, M.; Mir, A.R.; Habib, S.; Abidi, M.; Warsi, M.S.; Islam, S.; Moinuddin. Hydroxyl radical induced structural perturbations make insulin highly immunogenic and generate an auto-immune response in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2021, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakatsuki, A.; Okatani, Y.; Izumiya, C.; Ikenoue, N. Melatonin protects against ischemia and reperfusion-induced oxidative lipid and DNA damage in fetal rat brain. J Pineal Res 1999, 26, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtkar Vanashi, A.; Ghasemzadeh, H. Copper(II) containing chitosan hydrogel as a heterogeneous Fenton-like catalyst for production of hydroxyl radical: A quantitative study. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 199, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Sun, M.; Yu, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, S. Dual-emissive fluorescence measurements of hydroxyl radicals using a coumarin-activated silica nanohybrid probe. Analyst (Lond) 2016, 141, 2296–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louit, G.; Foley, S.; Cabillic, J.; Coffigny, H.; Taran, F.; Valleix, A.; Renault, J.P.; Pin, S. The reaction of coumarin with the OH radical revisited: Hydroxylation product analysis determined by fluorescence and chromatography. Radiat Phys Chem 2005, 72, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, W.J.; Rice, C.; McCrudden, D.; Skillen, N.; Robertson, P.K.J. Enhanced Monitoring of Photocatalytic Reactive Oxygen Species: Using Electrochemistry for Rapid Sensing of Hydroxyl Radicals Formed during the Degradation of Coumarin. J Phys Chem A 2023, 127, 5039–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manevich, Y.; Held, K.D.; Biaglow, J.E. Coumarin-3-Carboxylic Acid as a Detector for Hydroxyl Radicals Generated Chemically and by Gamma Radiation. Radiat Res 1997, 148, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Liu, Z.; Verwilst, P.; Koo, S.; Jangjili, P.; Kim, J.S.; Lin, W. Coumarin-Based Small-Molecule Fluorescent Chemosensors. Chem Rev 2019, 119, 10403–10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C. Coumarin-based derivatives with potential anti-HIV activity. Fitoterapia 2021, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Kopelman, R. Development of a hydroxyl radical ratiometric nanoprobe. Sens Actuators B Chem 2003, 90, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, N.; Makihara, K.; Ariyoshi, T.; Seto, D.; Maki, T.; Nakajima, H.; Nakano, K.; Imato, T. Phospholipid-linked Coumarin: A Fluorescent Probe for Sensing Hydroxyl Radicals in Lipid Membranes. Anal Sci 2008, 24, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Baranowska-kortylewicz, J.; BUMP, E.; Sahu, S.K.; Berman, R.M.; Kassis, A.I. A method for detection of hydroxyl radicals in the vicinity of biomolecules using radiation-induced fluorescence of coumarin. Int J Radiat Biol 1993, 63, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Folkard, M.; Huang, C.; Bump, E.; Baranowska-Kortylewicz, J.; Sahu, S.K.; Michael, B.D.; Kassis, A.I. Quantification of Radiation-Induced Hydroxyl Radicals within Nucleohistones Using a Molecular Fluorescent Probe. Radiat Res 1994, 138, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Makrigiorgos, G.M.; O'brien, K.; Bump, E.; Kassis, A.I. Measurement of hydroxyl radicals catalyzed in the immediate vicinity of DNA by metal-bleomycin complexes. Free Radic Biol Med 1996, 20, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Mahmood, A.; Kassiss, A.I.; Bump, E.A.; Jones, A.G.; Makrigiorgos, G.M. Generation of Hydroxyl Radicals by Nucleohistone-Bound Metal-Adriamycin Complexes. Free Radic Res 1996, 25, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Bump, E.; Huang, C.; Baranowska-Kortylewicz, J.; Kassis, A.I. Accessibility of nucleic acid-complexed biomolecules to hydroxyl radicals correlates with their conformation : a fluorescence polarization spectroscopy study. Int J Radiat Biol 1994, 66, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Bump, E.; Huang, C.; Baranowska-Kortylewicz, J.; Kassis, A.I. A fluorimetric method for the detection of copper-mediated hydroxyl free radicals in the immediate proximity of DNA. Free Radic Biol Med 1995, 18, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, S. Continuous detection of radiation or metal generated hydroxyl radicals within core chromatin particles. Int J Radiat Biol 1998, 73, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.P.; Young, A.M.; Palmer, A.E. Fluorescent sensors for measuring metal ions in living systems. Chem Rev 2014, 114, 4564–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.J.; Xu, Y.; Nam, K.H. Metal-Induced Fluorescence Quenching of Photoconvertible Fluorescent Protein DendFP. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chen, K.; Adelstein, S.J.; Kassis, A.I. Synthesis of Coumarin-Polyamine-Based Molecular Probe for the Detection of Hydroxyl Radicals Generated by Gamma Radiation. Radiat Res 2007, 168, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Yang, Y.; Adelstein, S.J.; Kassis, A.I. Synthesis and application of molecular probe for detection of hydroxyl radicals produced by Na 125I and γ-rays in aqueous solution. Int J Radiat Biol 2008, 84, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, V.J.; Konigsfeld, K.M.; Aguilera, J.A.; Milligan, J.R. DNA binding hydroxyl radical probes. Radiat Phys Chem 2012, 81, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandri, V.; Gardner, J.M.; Jonsson, M. Coumarin as a Quantitative Probe for Hydroxyl Radical Formation in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. J Phys Chem C 2019, 123, 6667–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandri, V.; Gardner, J.M.; Jonsson, M. Reply to "Comment on 'Coumarin as a Quantitative Probe for Hydroxyl Radical Formation in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis'". J Phys Chem C 2019, 123, 20685–20686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A.Y. Comment on "Coumarin as a Quantitative Probe for Hydroxyl Radical Formation in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis". J Phys Chem C 2019, 123, 20682–20684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žerjav, G.; Albreht, A.; Vovk, I.; Pintar, A. Revisiting terephthalic acid and coumarin as probes for photoluminescent determination of hydroxyl radical formation rate in heterogeneous photocatalysis. Appl Catal A Gen 2020, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Nosaka, Y. Quantitative detection of OH radicals for investigating the reaction mechanism of various visible-light TiO2 photocatalysts in aqueous suspension. J Phys Chem C 2013, 117, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, G.L.; Milligan, J.R. Fluorescence detection of hydroxyl radicals. Radiat Phys Chem 2006, 75, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuessel, K.; Frey, C.; Jourdan, C.; Keil, U.; Weber, C.C.; Müller-Spahn, F.; Müller, W.E.; Eckert, A. Aging sensitizes toward ROS formation and lipid peroxidation in PS1M146L transgenic mice. Free Radic Biol Med 2006, 40, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis, A.; Vlachogianni, T.; Fiotakis, C. 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG): A Critical Biomarker of Oxidative Stress and Carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C 2009, 42, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial DNA in Aging and Disease. Sci Am 1997, 277, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Park, J.Y.; Jung, H.J.; Kwon, H.J. Identification and biological activities of a new antiangiogenic small molecule that suppresses mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 404, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachootham, D.; Alexandre, J.; Huang, P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: A radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, X. A yellow-emissive carbon nanodot-based ratiometric fluorescent nanosensor for visualization of exogenous and endogenous hydroxyl radicals in the mitochondria of live cells. J Mater Chem B 2019, 7, 3737–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Song, J.; Yung, B.C.; Huang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, X. Ratiometric optical nanoprobes enable accurate molecular detection and imaging. Chem Soc Rev 2018, 47, 2873–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific Available online:. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/M7512 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Ma, J.; Kong, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Xie, H.; Si, W.; Zhang, Z. A dual-emission mitochondria targeting fluorescence probe for detecting hydroxyl radical and its generation induced by cellular activities. J Mol Liq 2024, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, L.; Meng, X.; Gu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, X. A mitochondria-specific fluorescent probe for rapidly assessing cell viability. Talanta 2021, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, S.D.B.; Funk, R.S.; Rajewski, R.A.; Krise, J.P. Mechanisms of amine accumulation in, and egress from, lysosomes. Bioanalysis 2009, 1, 1445–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Ding, H.; Sun, H.; Zhou, L.; Lin, Q. A mitochondrion-targeting turn-on fluorescent probe detection of endogenous hydroxyl radicals in living cells and zebrafish. Sens Actuators B Chem 2019, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, C.; Torii, S.; Hou, N.; Saito, N.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Imai, H.; Takeuchi, T. Constitutive reactive oxygen species generation from autophagosome/lysosome in neuronal oxidative toxicity. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, X.; Tian, W.; Li, C.; Li, P.; Zhao, J.; Yang, S.; Li, S. The role of redox-mediated lysosomal dysfunction and therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gomez-Sintes, R.; Boya, P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death. Traffic 2018, 19, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditaranto, K.; Tekirian, T.L.; Yang, A.J. Lysosomal membrane damage in soluble Aβ-mediated cell death in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2001, 8, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micsenyi, M.C.; Sikora, J.; Stephney, G.; Dobrenis, K.; Walkley, S.U. Lysosomal membrane permeability stimulates protein aggregate formation in neurons of a lysosomal disease. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 10815–10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, T.P.; Alcalá, S.; Rico-Ferreira, M.D.R.; Hernández-Encinas, E.; García, J.; Albarrán, M.I.; Valle, S.; Muñoz, J.; Martínez-González, S.; Blanco-Aparicio, C.; et al. Induction of lysosome membrane permeabilization as a therapeutic strategy to target pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancers 2020, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeGendre, O.; Breslin, P.A.S.; Foster, D.A. (-)-Oleocanthal rapidly and selectively induces cancer cell death via lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Mol Cell Oncol 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benitez-Martin, C.; Guadix, J.A.; Pearson, J.R.; Najera, F.; Perez-Pomares, J.M.; Perez-Inestrosa, E. A turn-on two-photon fluorescent probe for detecting lysosomal hydroxyl radicals in living cells. Sens Actuators B Chem 2019, 284, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Fu, D.; Xu, J.; Tan, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, M. Rational design of a lysosome-targeted fluorescent probe for monitoring the generation of hydroxyl radicals in ferroptosis pathways. RSC advances 2024, 14, 12864–12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wong, Y.C.; Krainc, D. Mitochondria-lysosome contacts regulate mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics via lysosomal TRPML1. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2020, 117, 19266–19275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzo, R.; Costa, R.; Bachmann, M.; Leanza, L.; Szabò, I. Mitochondrial metabolism, contact sites and cellular calcium signaling: Implications for tumorigenesis. Cancers 2020, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbulla, L.F.; Song, P.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Zampese, E.; Wong, Y.C.; Jeon, S.; Santos, D.P.; Blanz, J.; Obermaier, C.D.; Strojny, C.; et al. Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Science 2017, 357, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, J.; Belton, T.B.; Shum, G.C.; Molakal, C.G.; Wong, Y.C. Mitochondria-lysosome contact site dynamics and misregulation in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci 2022, 45, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, M.; Kong, X.; Xie, H.; Li, H.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, Z. An innovative dual-organelle targeting NIR fluorescence probe for detecting hydroxyl radicals in biosystem and inflammation models. Bioorg Chem 2024, 151, 107678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Mai, Y.Z.; Zheng, M.H.; Wu, X.; Jin, J.Y. Fluorescent probe disclosing hydroxyl radical generation in mitochondria and nucleoli of cells during ferroptosis. Sens Actuators B Chem 2022, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Kapuscinski, J.; Carter, S.P.; Schmid, F.A.; Melamed, M.R. Cytostatic and Cytotoxic Properties of Pyronin Y: Relation to Mitochondrial Localization of the Dye and Its Interaction with RNA. Cancer Res 1986, 46, 5760–5766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z.Y. ROS-induced lipid peroxidation modulates cell death outcome: mechanisms behind apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Pérez, Y.; Carrasco-Legleu, C.; García-Cuellar, C.; Pérez-Carreón, J.; Hernández-García, S.; Salcido-Neyoy, M.; Alemán-Lazarini, L.; Villa-Treviño, S. Oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Correlation between lipid peroxidation and induction of preneoplastic lesions in rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett 2005, 217, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, N.P.; Bhutey, A.K.; Nagdeote, A.N.; Jadhav, A.A.; Manoorkar, G.S. Study of lipid peroxide and lipid profile in diabetes mellitus. Indian J Clin Biochem 2006, 21, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toborek, M.; Kopieczna-Grzebieniak, E.; Drbzdz, M.; Wieczorekb, M. Increased lipid peroxidation as a mechanism of methionine-induced atherosclerosis in rabbits. Atheroscler 1995, 115, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawara, K.; Waluk, J. Improved Method of Fluorescence Quantum Yield Determination. Anal Chem 2017, 89, 8650–8655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsenker, L.; Tatarets, A.; Kolosova, O.; Obukhova, O.; Povrozin, Y.; Fedyunyayeva, I.; Obukhova, I.; Terpetschnig, E. Fluorescent Probes and Labels for Biomedical Applications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008, 1130, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.F.; Da Ros, T.; Blaikie, F.H.; Prime, T.A.; Porteous, C.M.; Severina, I.I.; Skulachev, V.P.; Kjaergaard, H.G.; Smith, R.J.; Murphy, M.P. Accumulation of lipophilic dications by mitochondria and cells. Biochem J 2006, 400, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkin, M.S.; Boukens, B.J.; Tetlow, M.; Gutbrod, S.R.; Siong Ng, F.; Efimov, I.R.; Efimov, I.R. Mitochondrial depolarization and electrophysiological changes during ischemia in the rabbit and human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014, 307, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyamzaev, K.G.; Tokarchuk, A.V.; Panteleeva, A.A.; Mulkidjanian, A.Y.; Skulachev, V.P.; Chernyak, B.V. Induction of autophagy by depolarization of mitochondria. Autophagy 2018, 14, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, S.R.; Ahmed, M.; Lei, E.K.; Wisnovsky, S.P.; Kelley, S.O. Peptide-Mediated Delivery of Chemical Probes and Therapeutics to Mitochondria. Acc Chem Res 2016, 49, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmi, F.; Hensley, T.; Pope, C.; Funk, R.S.; Loewen, G.J.; Buckley, D.B.; Parkinson, A. Lysosomal sequestration (trapping) of lipophilic amine (cationic amphiphilic) drugs in immortalized human hepatocytes (Fa2N-4 cells). Drug Metab Dispos 2013, 41, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, D.-H.; Liu, Y.-H.; Ran, X.-Y.; Xiang, F.-F.; Zhang, L.-N.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yu, X.-Q.; Li, K. Migration from Lysosome to Nucleus: Monitoring Lysosomal Alkalization-Related Biological Processes with an Aminofluorene-Based Probe. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 7071–7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hong, X.-Q.; Zhi, H.-T.; Jinhui, H.; Chen, W.-H. Synthesis and mechanism of biological action of morpholinyl-bearing arylsquaramides as small-molecule lysosomal pH modulators. RSC advances 2022, 12, 22748–22759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfbeis, O.S. An overview of nanoparticles commonly used in fluorescent bioimaging. Chem Soc Rev 2015, 44, 4743–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, K.; Taratula, O.; Farsad, K. Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 799–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Park, S.; Yoon, J.; Shin, I. Recent progress in the development of near-infrared fluorescent probes for bioimaging applications. Chem Soc Rev 2014, 43, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Giordano, S.; Zhang, J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: Cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem J 2012, 441, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deus, C.M.; Yambire, K.F.; Oliveira, P.J.; Raimundo, N. Mitochondria–lysosome crosstalk: from physiology to neurodegeneration. Trends Mol Med 2020, 26, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, S.-S.; Nauduri, D.; Anders, M.W. Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria: A new therapeutic direction. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2006, 1762, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asayama, S.; Kawamura, E.; Nagaoka, S.; Kawakami, H. Design of Manganese Porphyrin Modified with Mitochondrial Signal Peptide for a New Antioxidant. Mol Pharm 2006, 3, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Ma, Y.; Niu, X.; Pei, J.; Yan, R.; Xu, F.; Ma, J.; Ma, X.; Jia, S.; Ma, W. Silver nanoparticles induce endothelial cytotoxicity through ROS-mediated mitochondria-lysosome damage and autophagy perturbation: The protective role of N-acetylcysteine. Toxicol 2024, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key criteria of •OH probe | Purpose |

|---|---|

| High selectivity/specificity | To ensure accurate and specific detection of •OH without interference from other ROS. |

| High sensitivity | To detect low concentrations of •OH, improving the ability to observe subtle changes in cellular environments. |

| High photostability | To resist photobleaching during illumination to maintain consistent, reliable detection of •OH over extended time periods. |

| Stability across biologically relevant pH range | To maintain consistent performance across different pH levels, ensuring reliability in various biological settings. |

| Resistance to interference | To avoid inaccurate measurements caused by radiation, transition metals, proteins, or ions, preserving the probe’s integrity. |

| Effective targeting and retention | To enable detection at the precise location within the cell, minimizing background interference from the solution. |

| Non-altering binding | To ensure the probe binds to target macromolecules, such as DNA, without altering their structure or compromising functionality. |

| Cell permeability | To facilitate quick and easy entry into cells for effective targeting at cellular sites. |

| Low cytotoxicity | To minimize harmful effects on cells, allowing for more reliable in vitro and in vivo experiments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).