Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

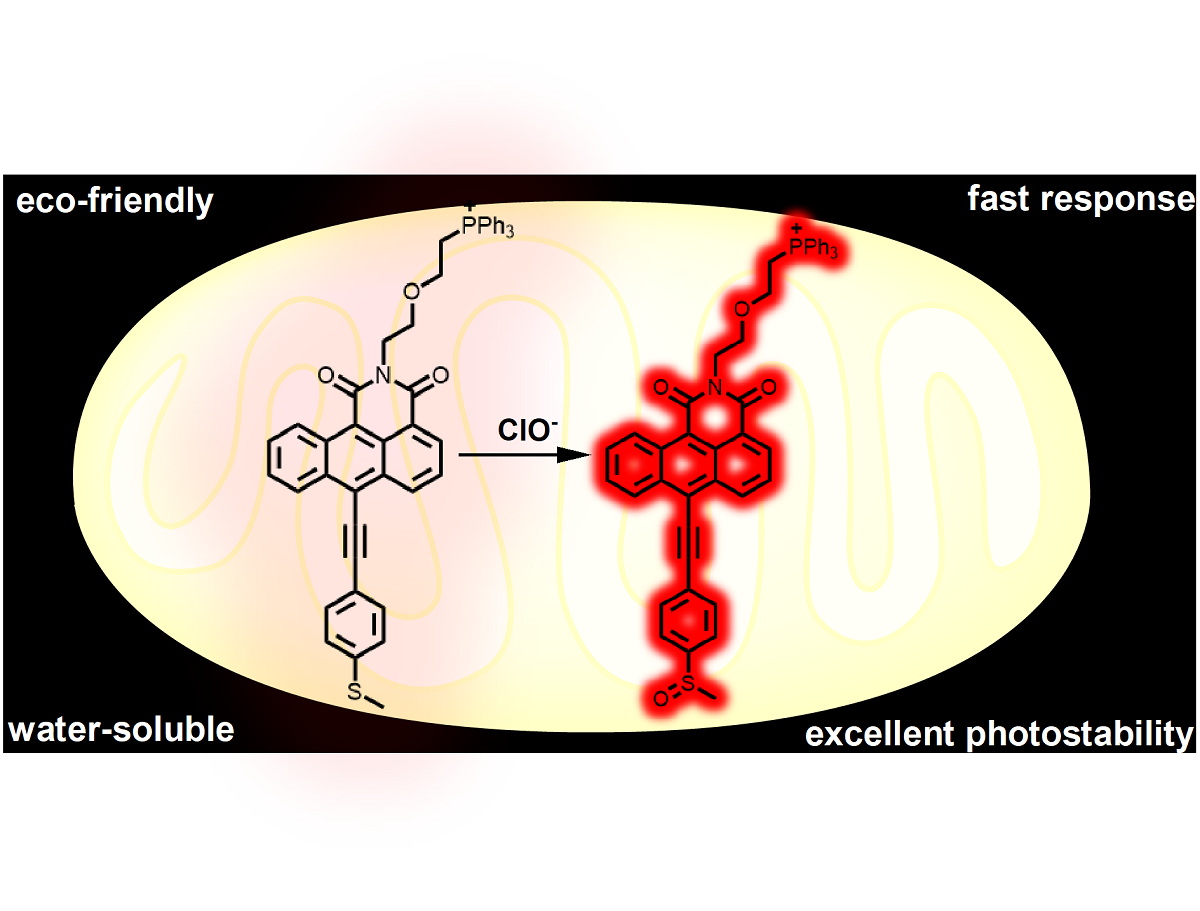

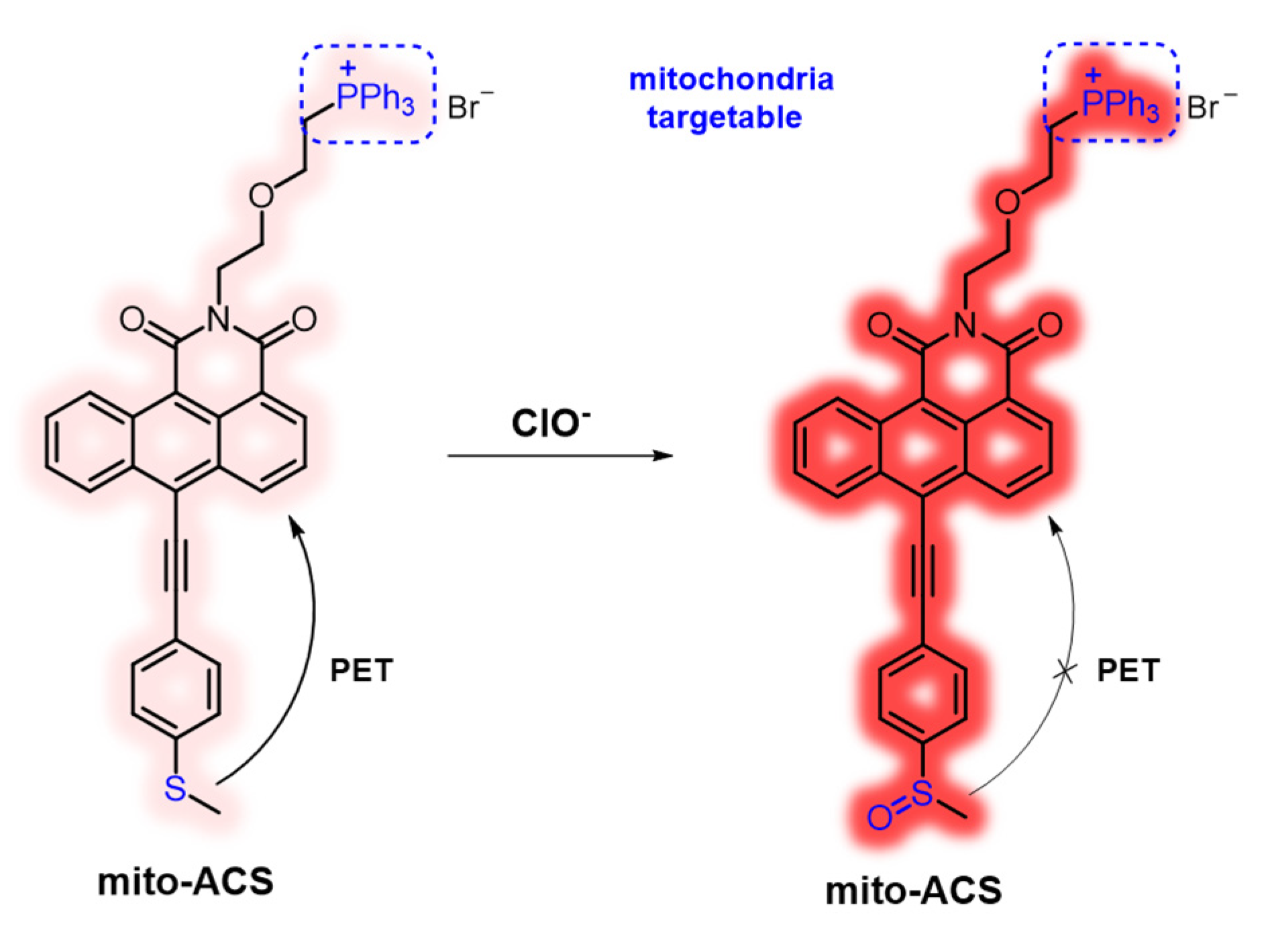

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

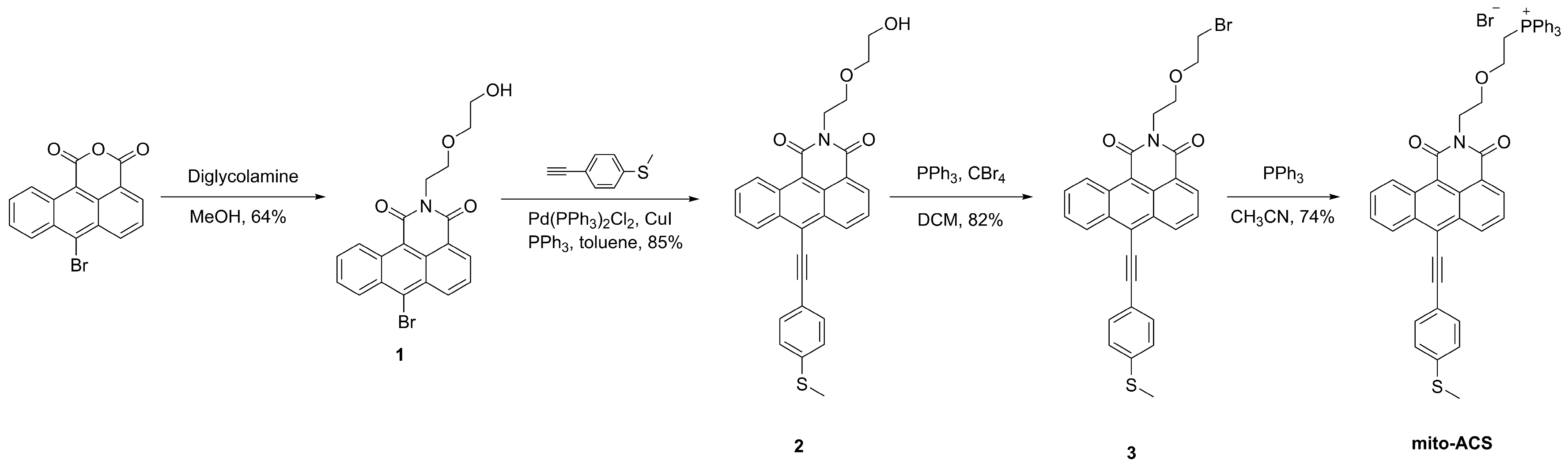

2.2. Synthesis

2.3. Preparation of the Spectral Measurements

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

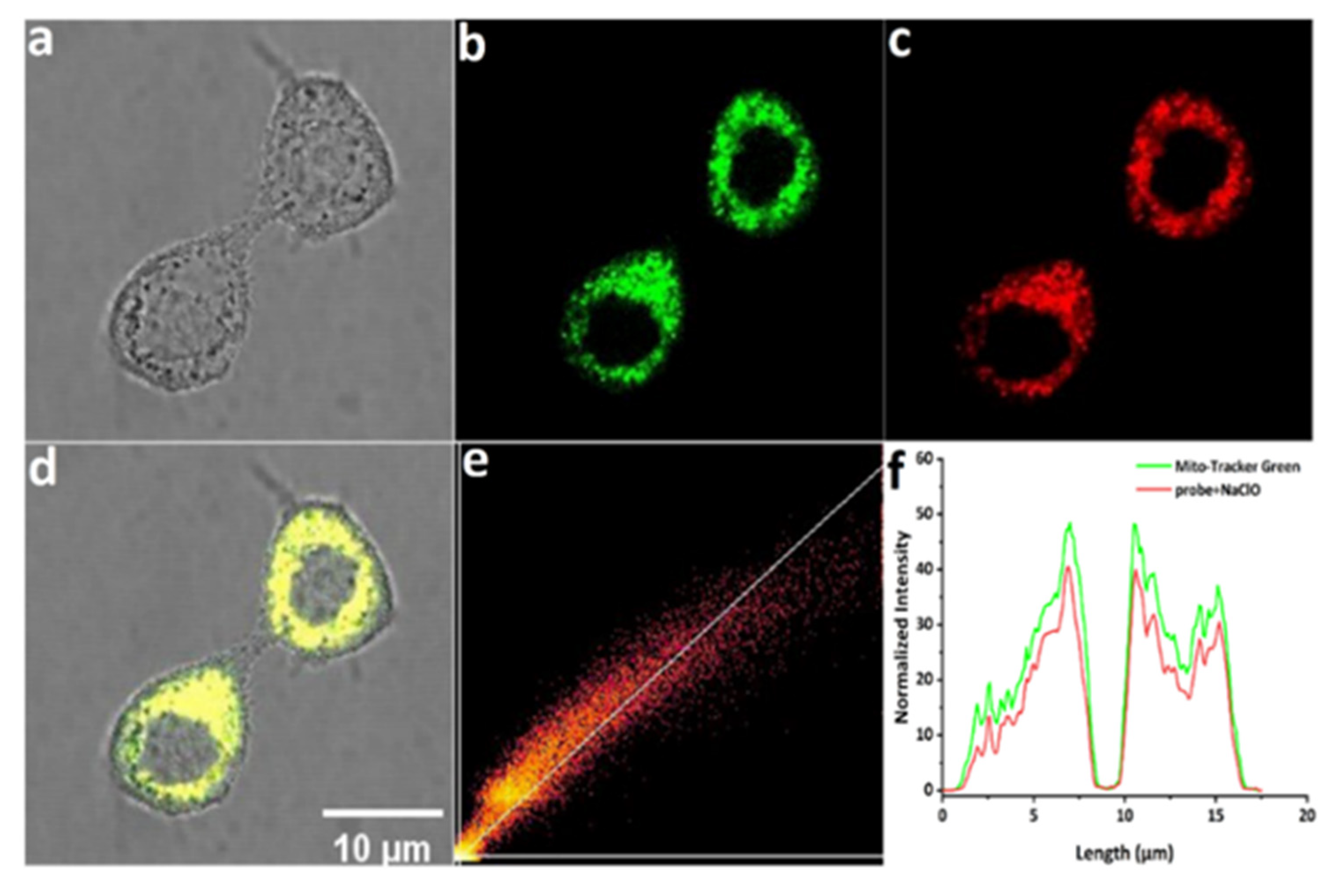

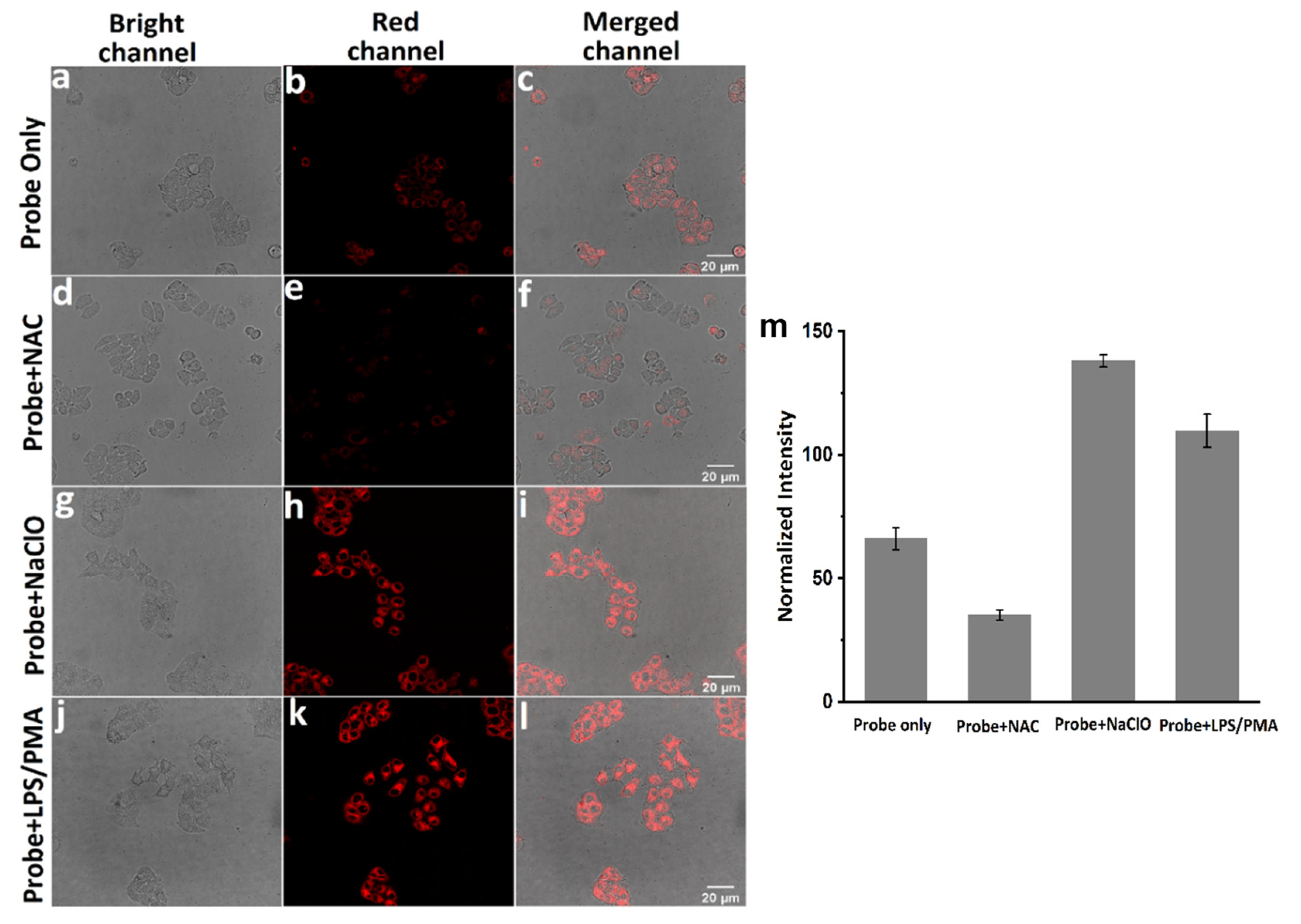

2.5. Confocal Fluorescence Imaging

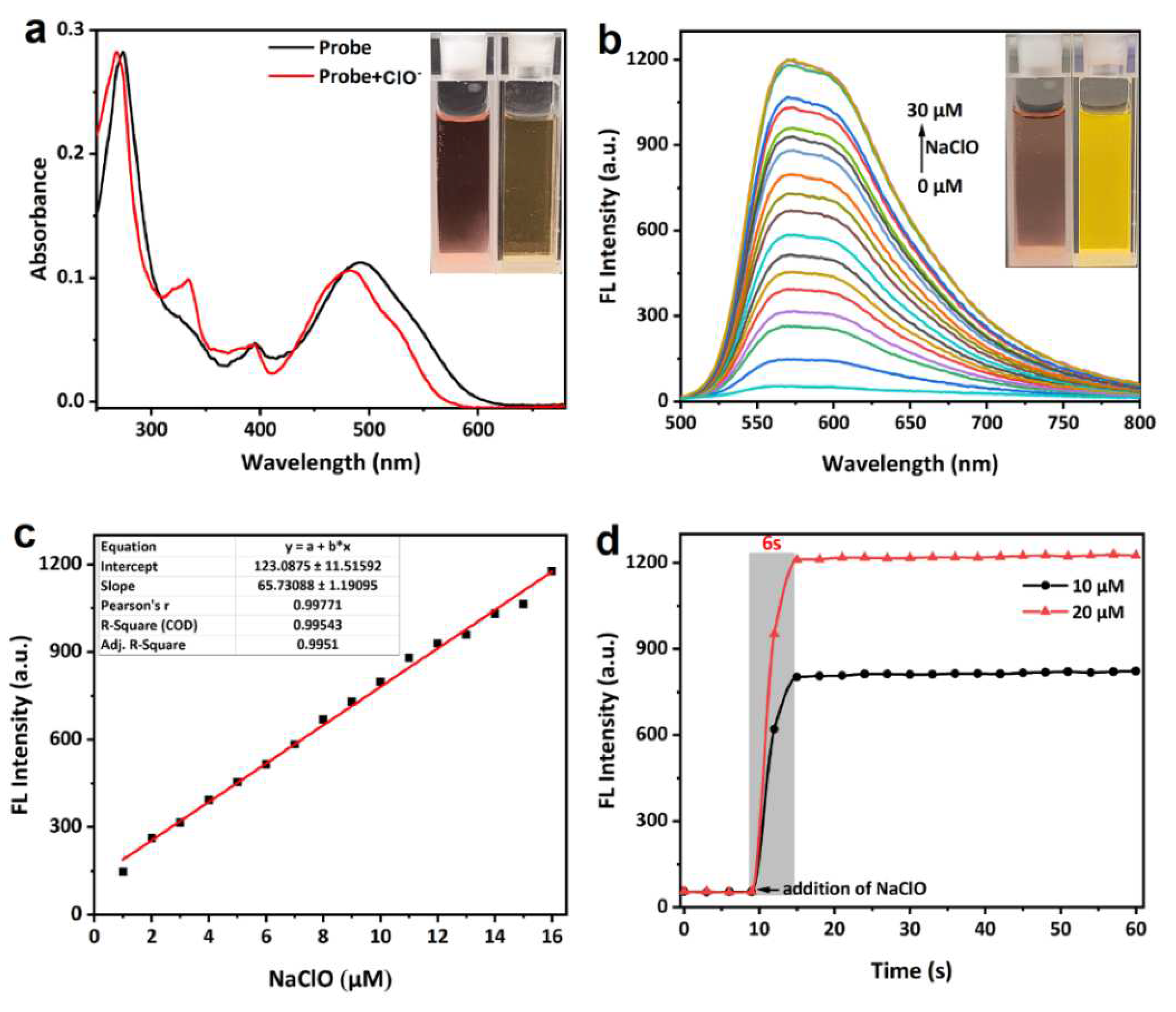

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hawkins, C. L.; Davies, M. J. , Role of myeloperoxidase and oxidant formation in the extracellular environment in inflammation-induced tissue damage. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Song, B.; Yuan, J. , Bioanalytical methods for hypochlorous acid detection: Recent advances and challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 99, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, R. P.; Rezende, F.; Schröder, K. , Redox Regulation Beyond ROS. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, G. E.; Thorn, R. M. S.; Reynolds, D. M. , The efficacy of chlorine-based disinfectants against planktonic and biofilm bacteria for decentralised point-of-use drinking water. npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, T. H.; Okada, S. S.; Ghosn, E. E.; Taniwaki, N. N.; Rodrigues, M. R.; de Almeida, S. R.; Mortara, R. A.; Russo, M.; Campa, A.; Albuquerque, R. C. , Intracellular localization of myeloperoxidase in murine peritoneal B-lymphocytes and macrophages. Cell. Immunol. 2013, 281, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aratani, Y. , Myeloperoxidase: Its role for host defense, inflammation, and neutrophil function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 640, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casciaro, M.; Di Salvo, E.; Pace, E.; Ventura-Spagnolo, E.; Navarra, M.; Gangemi, S. , Chlorinative stress in age-related diseases: a literature review. Immun. Ageing 2017, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Liu, L.; Yuan, W.; Yang, J.; Li, R.; Yi, T. , A fluorescent probe operating under weak acidic conditions for the visualization of HOCl in solid tumors in vivo. Sci. China Chem. 2020, 63, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Lei, Q.; Dai, Y.; Wang, D.; Yu, Q.; Lv, Y.; Li, W. , Simultaneous Monitoring of HOCl and Viscosity with Drug-Induced Pyroptosis in Live Cells and Acute Lung Injury. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12144–12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Jia, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R. , Rapid Response Fluorescence Probe Enabled In Vivo Diagnosis and Assessing Treatment Response of Hypochlorous Acid-Mediated Rheumatoid Arthritis. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J. K. , Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence? Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabharwal, S. S.; Schumacker, P. T. , Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles’ heel? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoye, A. T.; Davoren, J. E.; Wipf, P.; Fink, M. P.; Kagan, V. E. , Targeting Mitochondria. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-t. T.; Whiteman, M.; Gieseg, S. P. , HOCl causes necrotic cell death in human monocyte derived macrophages through calcium dependent calpain activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, L.; Shi, W.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; Ma, H. , HOCl can appear in the mitochondria of macrophages during bacterial infection as revealed by a sensitive mitochondrial-targeting fluorescent probe. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4884–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, J.; James, T. D. , Recent progress in the development of fluorescent probes for imaging pathological oxidative stress. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 3873–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.-N.; Ha, J.; Cho, M.; Li, H.; Swamy, K. M. K.; Yoon, J. , Recent developments of BODIPY-based colorimetric and fluorescent probes for the detection of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species and cancer diagnosis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 439, 213936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Zang, Y.; Sun, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H. , Sensing mechanism of reactive oxygen species optical detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 131, 116009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z. , A ratiometric two-photon fluorescence probe for monitoring mitochondrial HOCl produced during the traumatic brain injury process. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 311, 127895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.-L.; Huang, X.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, C.; Ge, Y.-Q.; Cao, X.-Q. , Ratiometric fluorescent probe for the detection of HOCl in lysosomes based on FRET strategy. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 263, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Pan, W.; Li, N.; Tang, B. , Fluorescent probes for organelle-targeted bioactive species imaging. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 6035–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji-Ting, H.; Nahyun, K.; Shan, W.; Bingya, W.; Xiaojun, H.; Juyoung, Y.; Jianliang, S. , Sulfur-based fluorescent probes for HOCl: Mechanisms, design, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 214232. [Google Scholar]

- Nahyun, K.; Yahui, C.; Xiaoqiang, C.; Myung Hwa, K.; Juyoung, Y. , Recent progress on small molecule-based fluorescent imaging probes for hypochlorous acid (HOCl)/hypochlorite (OCl−). Dyes Pigm. 2022, 200, 110132. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, M.; Zhou, K.; He, L.; Lin, W. , Mitochondria and lysosome-targetable fluorescent probes for HOCl: recent advances and perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 6,1716–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Zhong, G.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Fu, Y.; Shen, B. , Recent development of synthetic probes for detection of hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2020, 240, 118545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Wang, L.; Agrawalla, B. K.; Park, S.-J.; Zhu, H.; Sivaraman, B.; Peng, J.; Xu, Q.-H.; Chang, Y.-T. , Development of Targetable Two-Photon Fluorescent Probes to Image Hypochlorous Acid in Mitochondria and Lysosome in Live Cell and Inflamed Mouse Model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5930–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C. C. , Biological reactivity and biomarkers of the neutrophil oxidant, hypochlorous acid. Toxicology 2002, 181–182, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aratani, Y.; Koyama, H.; Nyui, S.-i.; Suzuki, K.; Kura, F.; Maeda, N. , Severe Impairment in Early Host Defense againstCandida albicans in Mice Deficient in Myeloperoxidase. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 1828–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V. , Probes: paths to photostability. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, D.; Peng, G.; Liu, G.; Zhou, R.; Wang, C.; Yan, X.; Liu, F.; Sun, P.; Zhou, J.; Lu, G. , Super-resolution dynamic tracking of cellular lipid droplets employing with a photostable deep red fluorogenic probe. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 229, 115243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Duan, C.; Wu, J.; Su, D.; Zeng, L.; Sheng, R. , Colorimetric and Ratiometric Chemosensor for Visual Detection of Gaseous Phosgene Based on Anthracene Carboxyimide Membrane. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 8686–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Niu, G.; Wei, X.; Lan, M.; Zeng, L.; Kinsella, J. M.; Sheng, R. , A family of multi-color anthracene carboxyimides: Synthesis, spectroscopic properties, solvatochromic fluorescence and bio-imaging application. Dyes Pigm. 2017, 139, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zeng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Hou, J.-T.; Yoon, J. , A paper-based chemosensor for highly specific, ultrasensitive, and instantaneous visual detection of toxic phosgene. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 13753–13756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.-T.; Kwon, N.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; He, X.; Yoon, J.; Shen, J. , Sulfur-based fluorescent probes for HOCl: Mechanisms, design, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 450, 214232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hou, S.; Zhao, N.; Finney, N.; Wang, Y. , A novel colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe for monitoring lysosomal HOCl in real time. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 204, 110394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, A. P. , Crossing the divide: Experiences of taking fluorescent PET (photoinduced electron transfer) sensing/switching systems from solution to solid. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 204, 110453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J. H.; Chi, C.; Wu, J.; Loh, K.-P. , Bisanthracene Bis(dicarboxylic imide)s as Soluble and Stable NIR Dyes. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9299–9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Ochi, T.; Wakamiya, T.; Matsubara, Y.; Yoshida, Z.-i. , New Fluorophores with Rod-Shaped Polycyano π-Conjugated Structures: Synthesis and Photophysical Properties. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KETTLE, A. J.; GEDYE, C. A.; WINTERBOURN, C. C. , Mechanism of inactivation of myeloperoxidase by 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide. Biochem. J 1997, 321, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Gao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Wei, Q.; Ma, Z.; Du, B.; Zhang, X. , A 4-hydroxynaphthalimide-derived ratiometric fluorescent chemodosimeter for imaging palladium in living cells. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8656–8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Xia, T.; Hu, W.; Chen, S.; Chi, S.; Lei, Y.; Liu, Z. , Visualizing the Regulation of Hydroxyl Radical Level by Superoxide Dismutase via a Specific Molecular Probe. Anal Chem 2018, 90, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodega, G.; Alique, M.; Puebla, L.; Carracedo, J.; Ramírez, R. M. , Microvesicles: ROS scavengers and ROS producers. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1626654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).