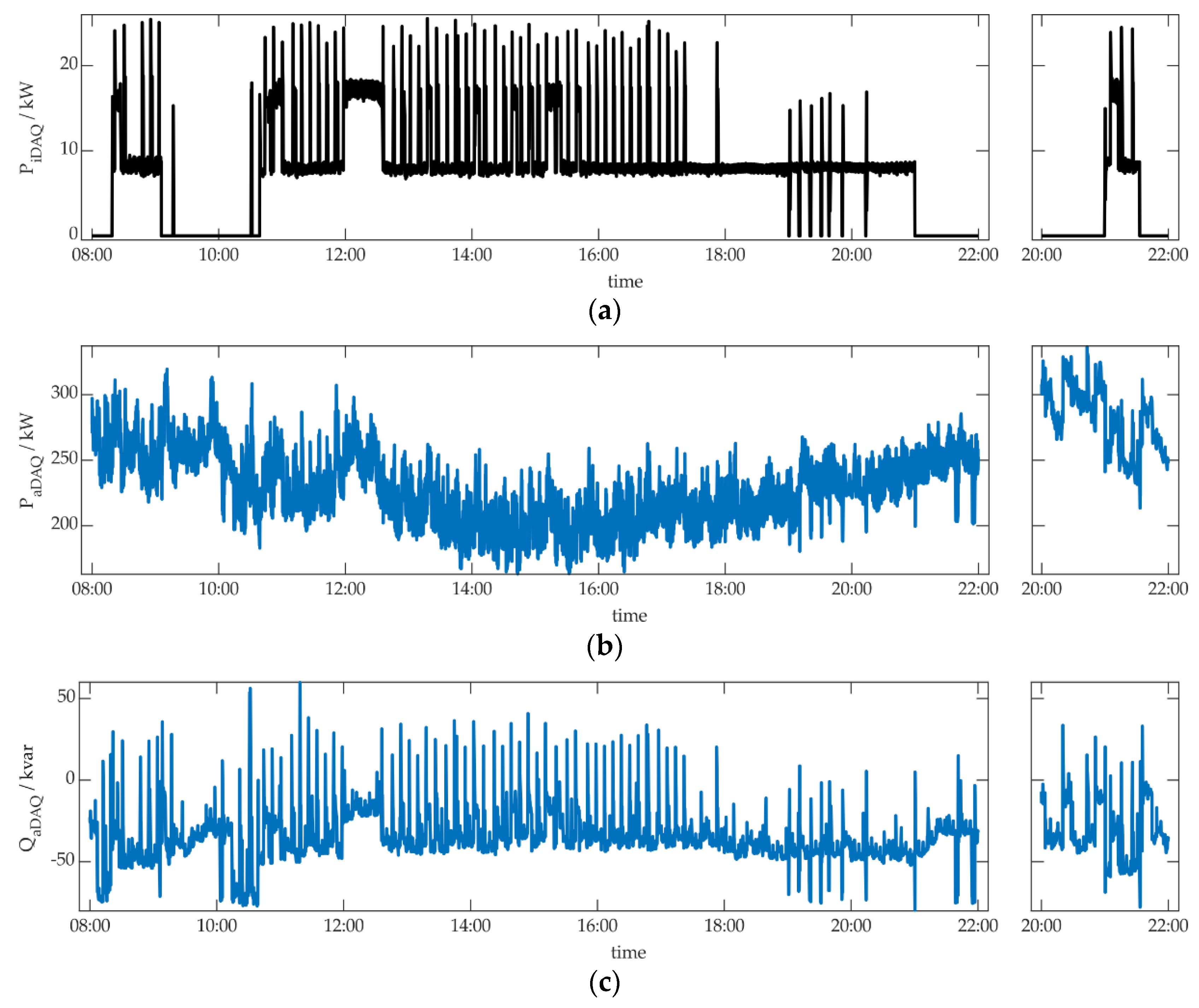

We used three days of measurement data, one for learning and two for testing the results. The measurements were performed in June 2022. The original measurement data can be found in [

49]. For these three days, we performed an aggregated data acquisition (aDAQ) of an university building at Munich University of Applied Sciences (MUAS). Simultaneously, individual data acquisition (iDAQ) was carried out for a refrigeration plant’s cold water preparation unit of the building.

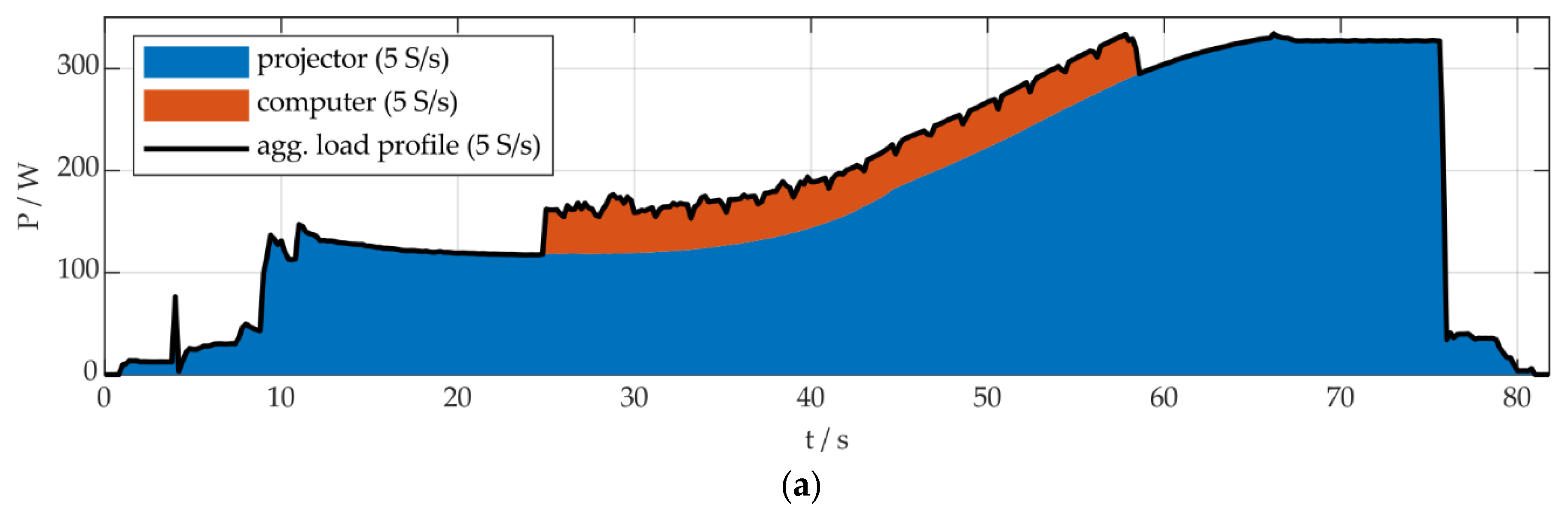

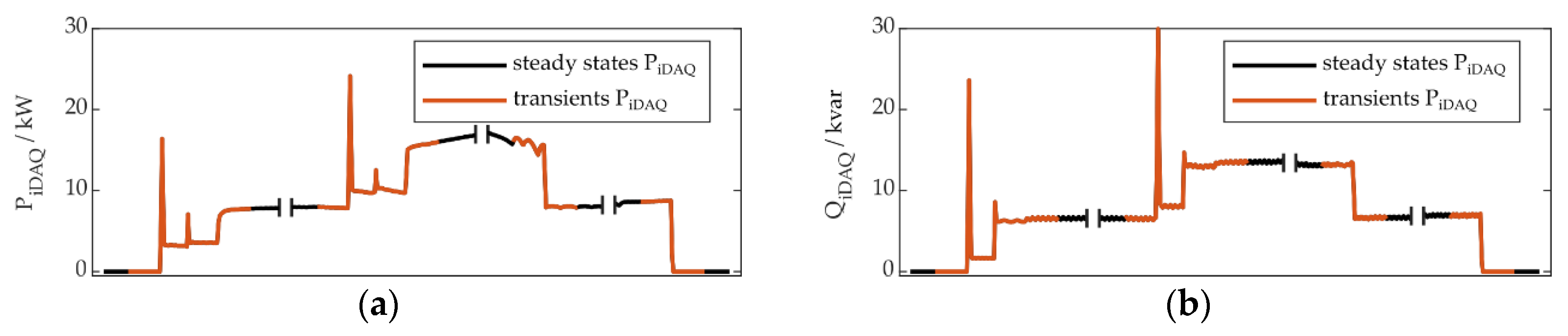

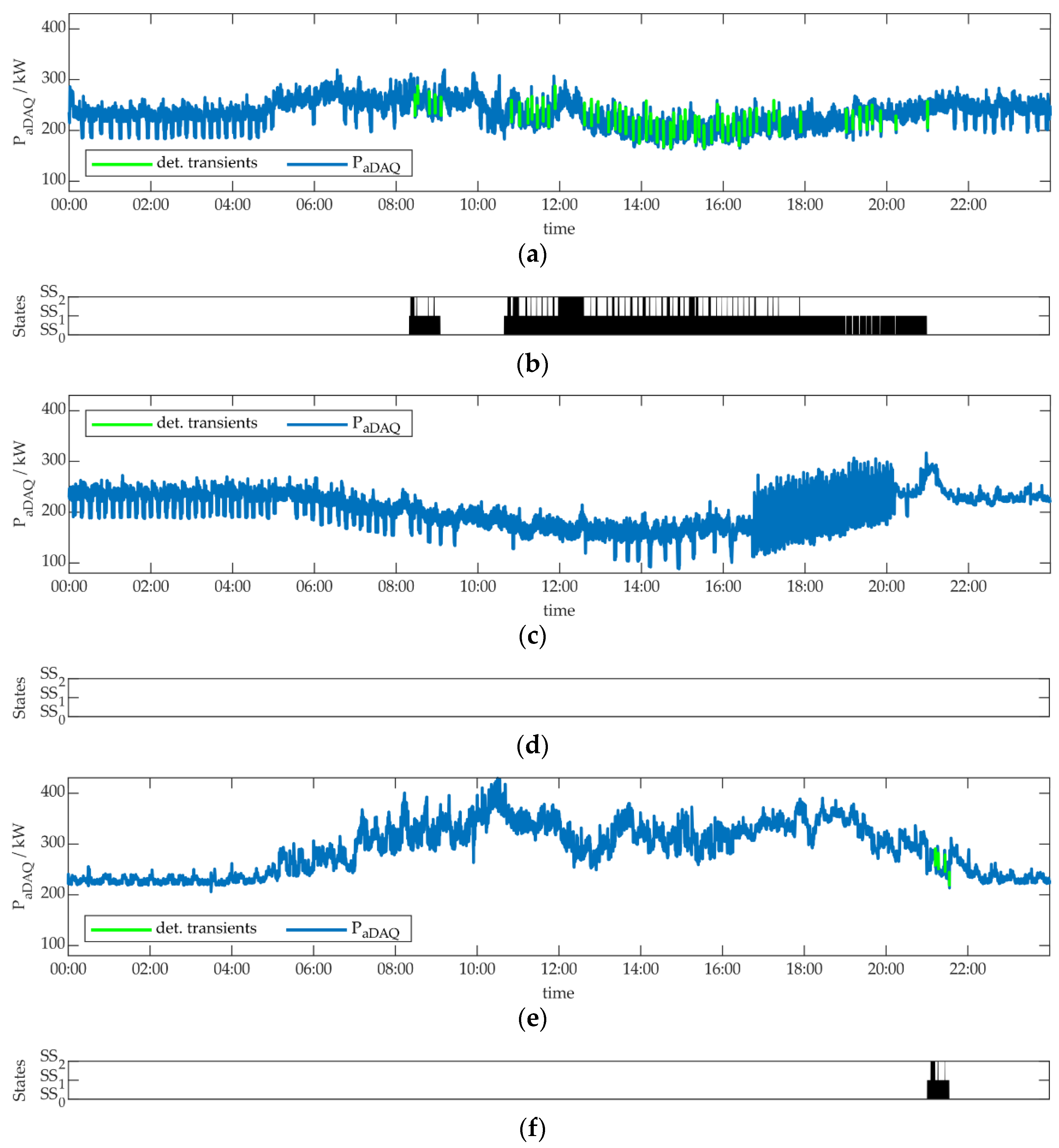

Figure 6a shows the active power behavior of the appliance, where the appliance was in operation on the three days. The left part of

Figure 6a represents appliance operation on the learning day, the right part shows appliance operation on one testing day. The second testing day, where the appliance was not active, is not shown. Despite, only fractions of the measurement data are presented in

Figure 6, the whole three days were used for application. Besides the active power measurements, also reactive power iDAQ was considered. Furthermore, it has to be noted, that iDAQ was performed for one single phase of the refrigeration plant, although the appliance is a three-phase consumer. It is shown in this work, that the single-phase measurement is sufficient within the methodology, because all further appliance information can be extracted from aDAQ. A correlation of aDAQ and iDAQ voltage measurement data, was performed in the first step, as described in

Section 3.1. In

Figure 6, the time-shift between iDAQ and aDAQ data, identified through correlation, was already considered and corrected. For each of the three days, the time-shift was lower than one minute.

After data acquisition and correlation, an appliance model for the building refrigeration plant was derived from the active power iDAQ data. This procedure is described in the following section.

4.1. Refrigeration Plant Appliance Model

In

Section 3.2, the methodology of appliance model building is explained. It is recommended to build application-specific models. In our application, we are using the refrigeration plant appliance model for energy disaggregation. Therefore, the appliance model is built from the learning day’s active power iDAQ data. As described in

Section 3.2, the event detection algorithm χ²-GOF is used, to separate transients and steady states of the appliance. The window size was set to 30 samples, which equals a duration of six seconds. The threshold, which in this case represents the critical value of χ² to decide for the presence of an event, was set to 5. After that, the active power mean values of the resulting steady states were clustered using the

DBSCAN algorithm, with the search radius distance (

ε) set to 0.2 and the minimum number of neighbors (

minpts) set to 1. The parameters for event detection and clustering were chosen rather manually, to achieve a suitable appliance model for the application of energy disaggregation. Therefore, the model should represent significant changes in the energy consumption of the appliance, analogous to our state definition (

Section 2). In future research the appliance model building should be improved further, to obtain a more automated method, applicable to all kinds of appliance types. It has to be noted, that the general methodology is not dependent on a specific method of appliance model building.

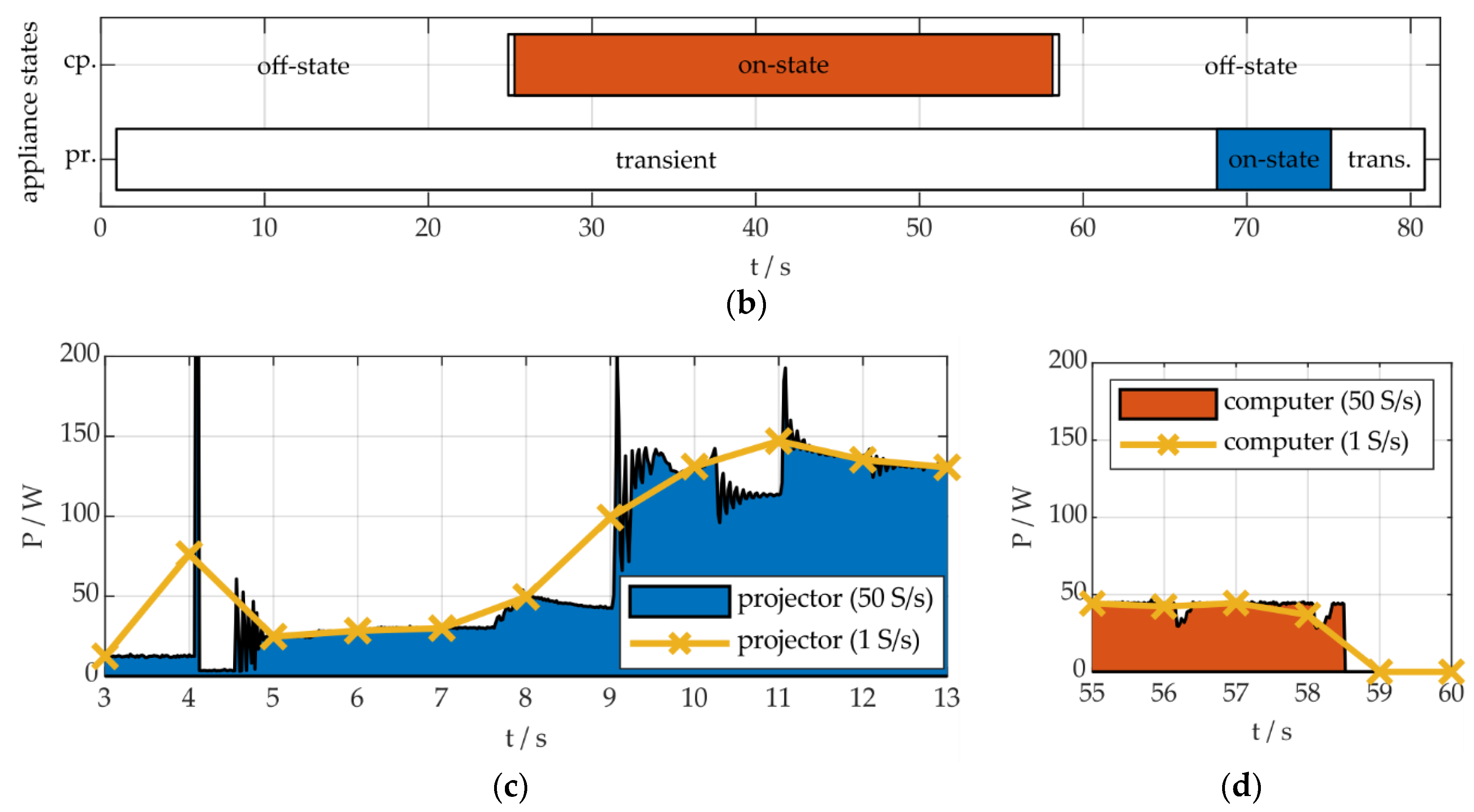

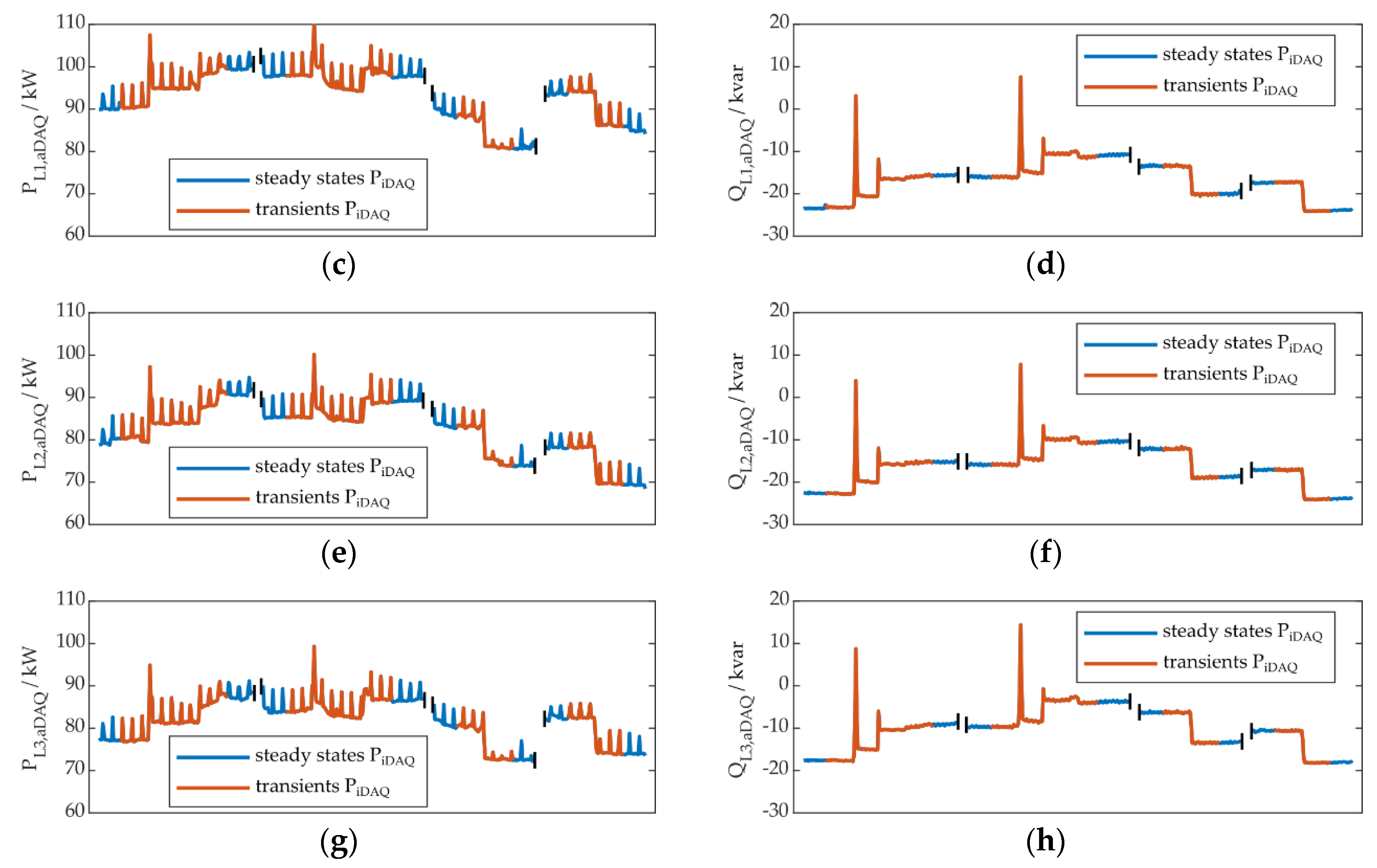

Figure 7a illustrates this method for areas around the first four different transients on the learning day, located between 8:00 and 10:00 in

Figure 6. In

Figure 8, the resulting appliance model is shown. The steady state clustering results in three types of steady states: SS

0 (off state), SS

1 (operation state 1) and SS

2 (operation state 2). Those steady state types are connected through the transient types TR

SS0→

SS1, TR

SS1→

SS0, TR

SS1→

SS2 and TR

SS2→

SS1. This appliance model represents the active power behavior of the refrigeration plant in a congruent and complete way for the learning day. Those transient types are evaluated individually in the following. The transient types TR

SS0→

SS1 and TR

SS1→

SS0 were identified nine times on the learning day, the transient types TR

SS1→

SS2 and TR

SS2→

SS1 45 times, respectively. It must be mentioned, that the ultimate load disaggregation results, depend strongly on the selection of suitable learning data. E.g. if a certain transient type occurs rarely in learning data, this might lead to poor results in the test data. The selection of suitable learning data is also a topic of further research.

Figure 7b–h show the first four different transients and their adjacent steady states, mapped to the other measured quantities, at their exact timestamps: Q

iDAQ, P

aDAQ (L1 to L3) and Q

aDAQ (L1 to L3). Therefore, the other measured quantities were evaluated at the exact timestamps, where the transients were they were identified in P

iDAQ. The correlation, described above, is necessary to be able to perform this mapping correctly. It can be seen, that the appliance behavior is much more evident in reactive power, compared to active power, at least for these four transients. Furthermore, through figures (c) to (h) it can be verified, that the refrigeration plant is a three-phase consumer. After this procedure, the presence of appliance transients and states, including their associated transient or steady state types according to the appliance model, is known throughout the whole learning day and can be used as a ground truth for performance evaluation.

Based on the event definition statement in

Section 2, the first transient in

Figure 7a, could be interpreted as being one event or containing three events. Within our methodology, it is evaluated, if a certain algorithm is capable of identifying this transient, no matter if this is done by detecting one event, three or more. This applies to state identification in eventless NILM as well, due to the fact, that a transient could also be identified through the corresponding states before and after, or a state could be determined through a state change, or transient, leading to this state.

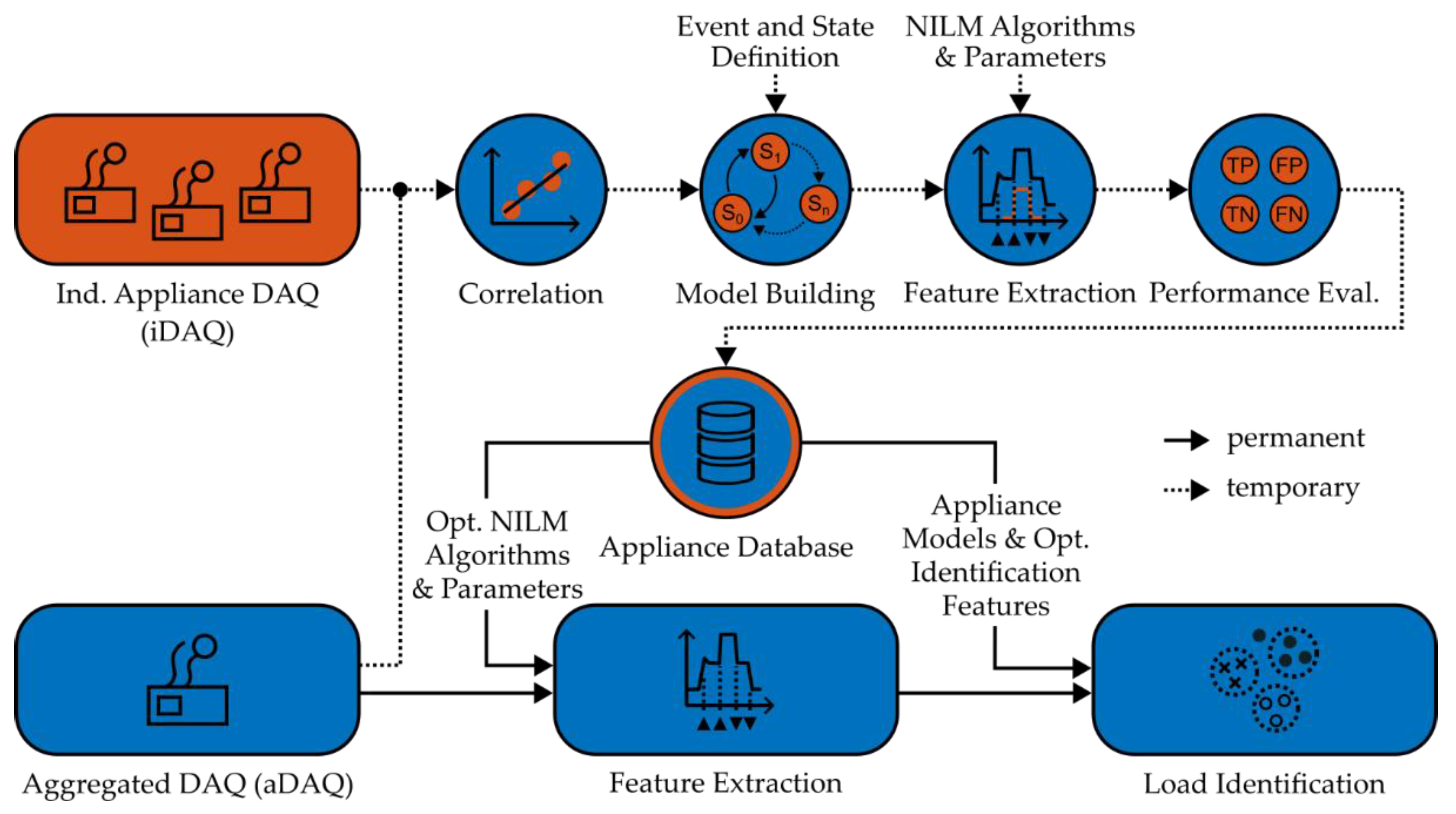

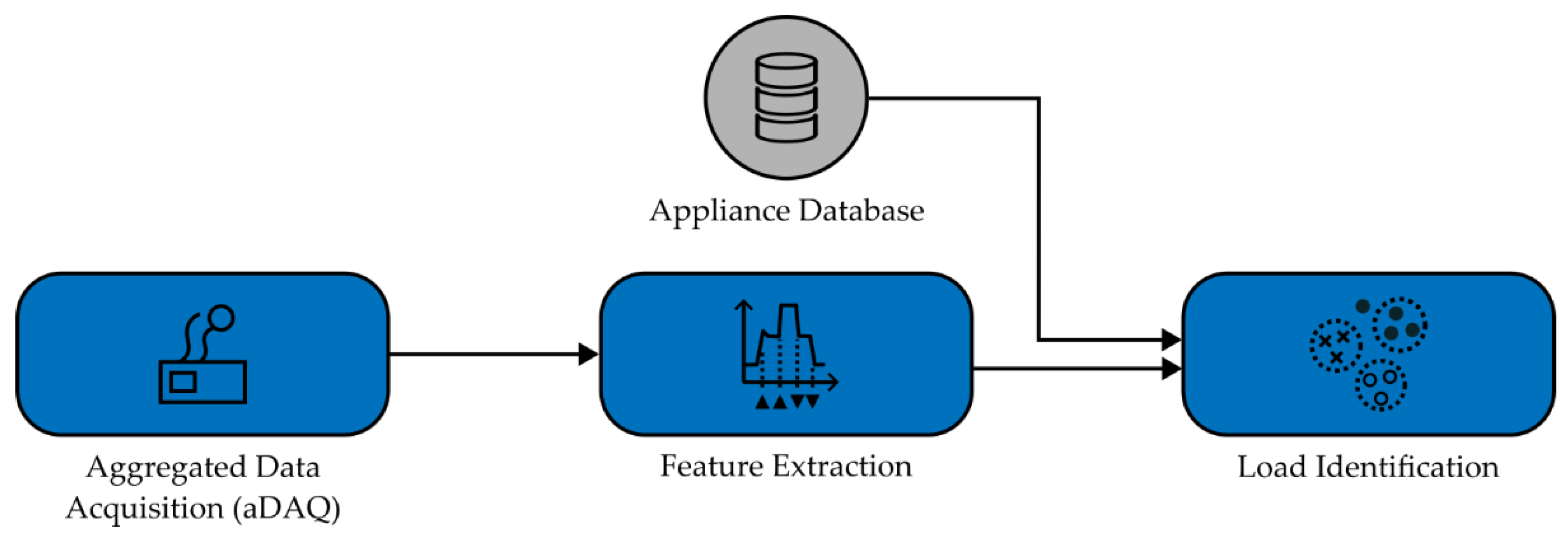

4.2. Event Detection, Feature Extraction and Clustering

In this work, we applied the two event detection algorithms χ²-GOF and DSC to the measured quantities P

aDAQ (L1 to L3) and Q

aDAQ (L1 to L3). For both algorithms, the input parameters window size and threshold were varied within predefined parameter sets. Those parameter settings are explained later in section 4.3. After that, feature extraction was performed for the resulting events of all individual algorithm-parameter-variants. Then features were clustered, to be able to identify suitable feature limits for load identification in the regular NILM process afterwards. The methodology of event detection, feature extraction and clustering can be found in

Section 3.3.

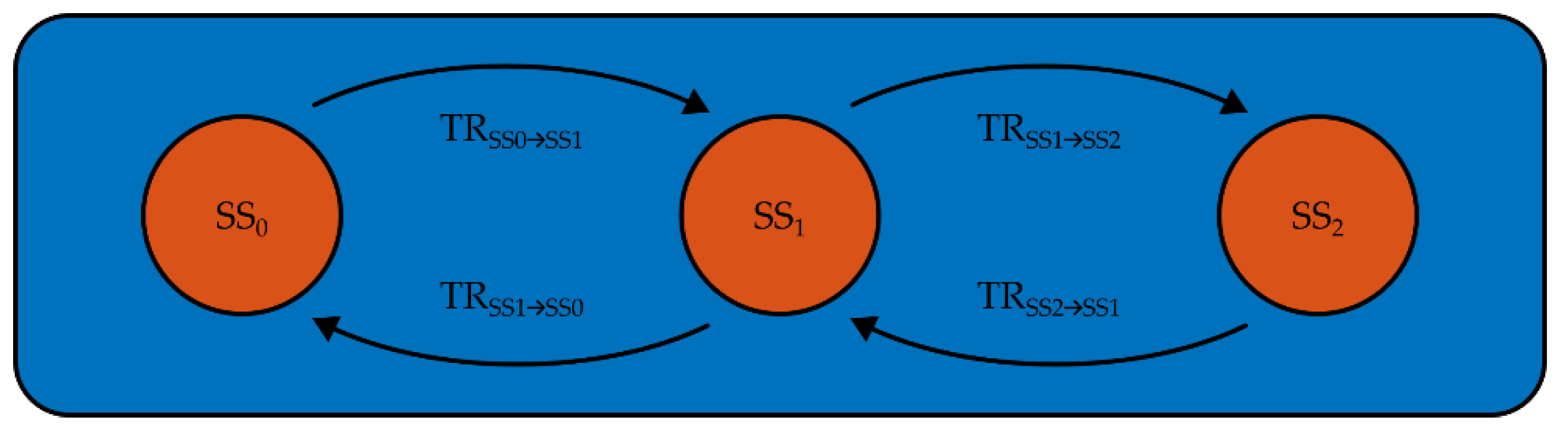

In

Figure 9, event detection is illustrated for a section of the learning day data. Here, the algorithm χ²-GOF was applied to phase L1 of Q

aDAQ. The parameters window size and threshold were set to 4 samples and 0.05 for this example.

Figure 9a shows Q

iDAQ, as well as one transient of the type TR

SS1→

SS2, derived from P

iDAQ and mapped to Q

iDAQ, as explained above. This transient connects SS

1 (around 8 kvar) and SS

2 (around 12 kvar) in this section.

Figure 9b shows two events, detected in Q

L1,aDAQ by the above described algorithm-parameter-variant (χ²-GOF with a window size of 4 and a threshold set to 0.05, applied to Q

L1,aDAQ). As the two events take place within the transient area in

Figure 9a, those events were marked as TP. More information about performance evaluation can be found later in

Section 4.3. It can be seen, that both events were caused by the refrigeration plant. Both events could be used for the identification of this appliance individually, or in combination. For this reason, we extracted features and feature limits for both events individually, due to the presented methodology. Therefore, a clustering of the features had to be done.

As explained in

Section 3.3, the absolute delta, the overshoot and the duration are extracted as features for every event and for the particular, considered parameter (P

aDAQ or Q

aDAQ). In the example, presented in

Figure 9, those features are ΔQ, ΔQ

os and Δt, because the algorithm-parameter-variant was applied to Q

aDAQ, in this case.

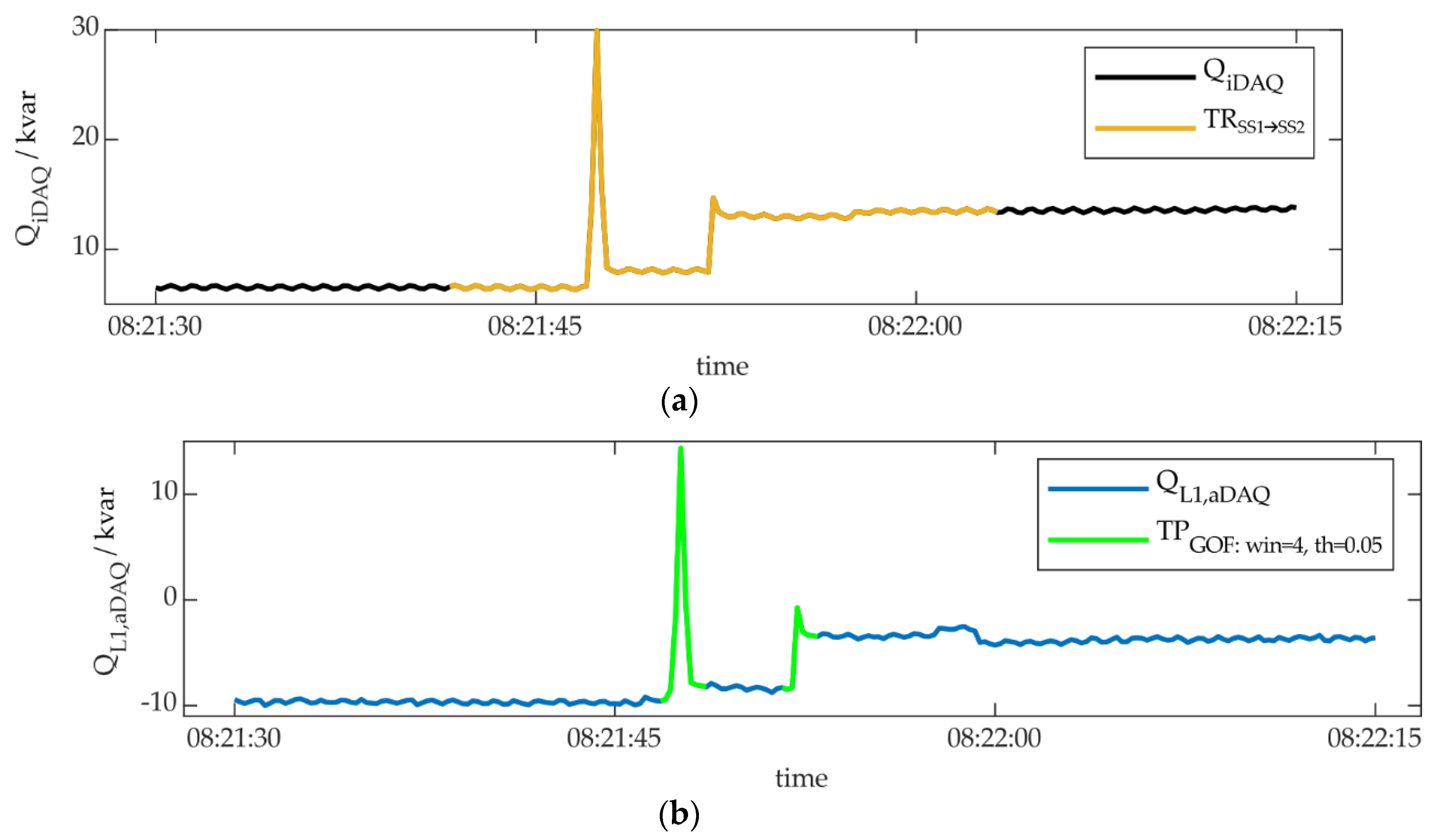

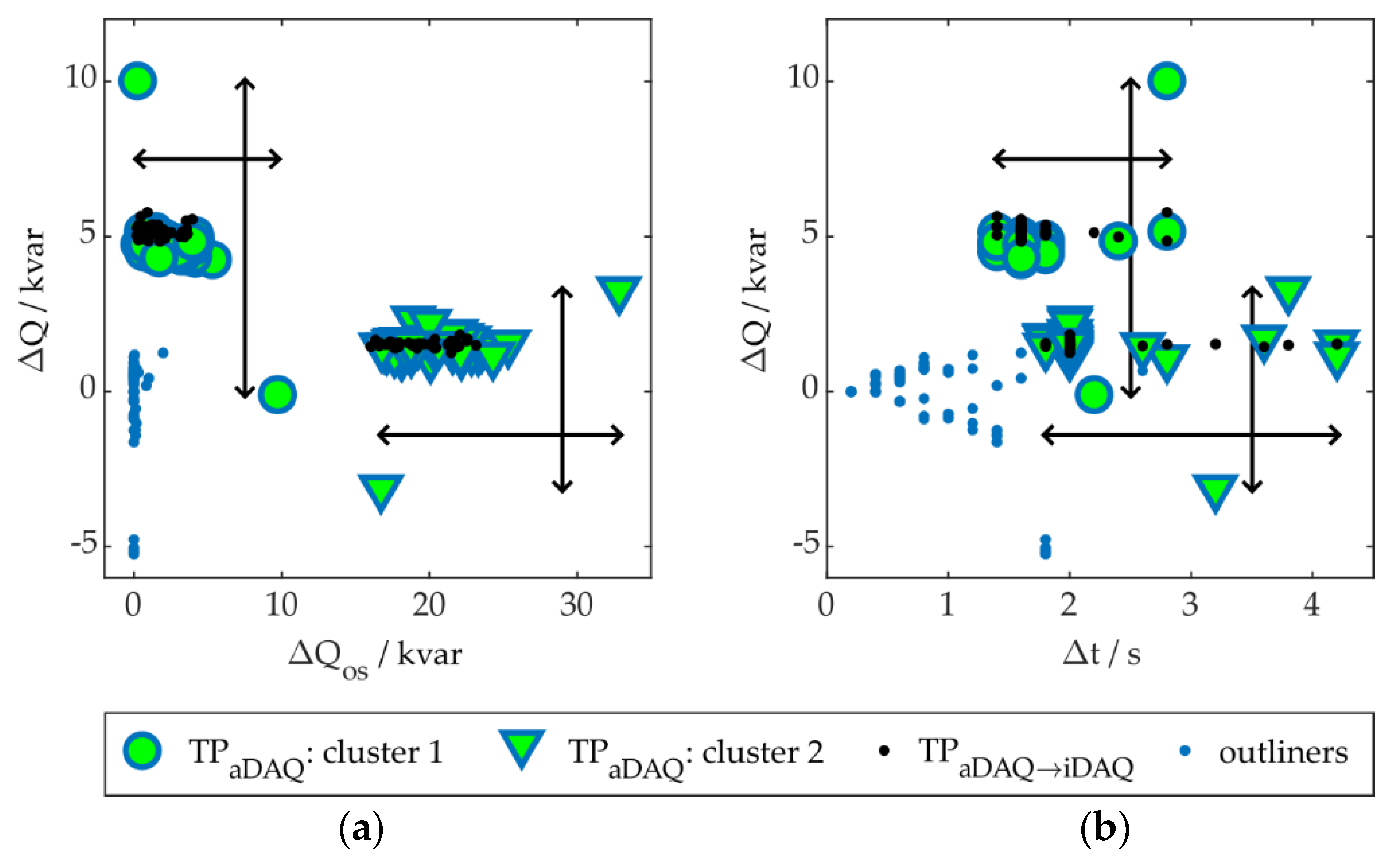

Figure 10 shows these features, extracted for the events, detected by this certain algorithm-parameter-variant for the whole learning day, not only the section, presented in

Figure 9. Only events, located within the areas of the transient type TR

SS1→

SS2 were taken into account. These events were marked TP, all other events, detected by this algorithm-parameter-variant, were rated FP (not shown in

Figure 10).

Figure 10a shows the TP-events regarding the features ΔQ

os and ΔQ,

Figure 10b for the features Δt and ΔQ, respectively.

Two separate clusters could be identified from the TP-events of Q

L1,aDAQ, besides outliners. The triangles and circles in

Figure 10 (filled green) are representing the clusters. Then, the feature limits for ΔQ, ΔQ

os and Δt were extracted from the clusters (black arrows), including all cluster-events. All events, ranging within these limits were assigned to the transient type TR

SS1→

SS2. The ΔQ- and ΔQ

os-limits of cluster 1 range from 0 to 10 kvar, the Δt-limits from 1.5 to nearly 3 s. The second event in

Figure 9b, shown above, is part of cluster 1. The first event in

Figure 9b is part of cluster 2, with limits of ΔQ from around -4 to 4 kvar, ΔQ

os between 15 to 35 kvar and Δt from 1.8 to 4.2 s, according to

Figure 10.

As explained above, in this example event detection was carried out for Q

L1,aDAQ and FPs were excluded. After that, the resulting TP-events were mapped to Q

iDAQ. These events, represented by the black dots in

Figure 10, were then used for clustering, because of the improved clustering performance, compared to the TP-events of Q

aDAQ.

As can be seen in

Figure 10, the black dots show more distinct clusters, in contrast to the circles and triangles, filled green. Q

aDAQ includes a large amount of appliances, affecting event detection and feature extraction performance, while Q

iDAQ contains the operational behavior of the refrigeration plant, only. For clustering, the Q

iDAQ features ΔQ, ΔQ

os Δt were extracted for all TP-events, detected from Q

aDAQ and mapped to Q

iDAQ.

These features were then normalized between the three individual feature’s absolute minimum and maximum values, to ensure equal weighting. Otherwise, the maximum value for ΔQ, for example around 2 kvar for cluster 2 (see black dots), would have less influence on cluster building, than the maximum value for ΔQ

os (around 25 kvar for cluster 2), due to the higher absolute value. The input feature vector for clustering then consisted of three columns, for the three features used, with values ranging between 0 and 1. The clustering results were then mapped back to the corresponding Q

L1,aDAQ-events (see triangles and circles for cluster 1 and cluster 2, as well as the blue-dotted outliners in

Figure 10), to be able to extract feature limits for load identification. It has to be noted, that for most algorithm-parameter-variants in this work, only one cluster was identified, besides outliners, especially for algorithms with greater window sizes.

As mentioned in

Section 3.2, clustering was performed using the

DBSCAN algorithm. Therefore, two input parameters had to be specified: The search radius distance (

ε) and the minimum number of neighbors (

minpts). The variable

minpts was set to the number of the transients identified through P

iDAQ in appliance modelling (n

TR), for the considered transient type on the learning day. As mentioned earlier in

Section 3.4, in the application of the presented methodology, we limit the resulting algorithm-parameter-variants to the ones, delivering 100 % TPs on the learning day. In the case of transient type TR

SS1→

SS2, n

TR was set to 45, due to the presence of 45 transients of the type TR

SS1→

SS2 on this day. This setting of n

TR ensures, that only clusters of algorithm-parameter-variants delivering 100 % TPs, are considered. For algorithm-parameter-variants with less than 100 % TPs, no clusters can be identified through this setting. The outliners in

Figure 10 (blue dots) are representing events in Q

L1,aDAQ, not occurring in every transient of the type TR

SS1→

SS2, therefore being excluded. Outliners were not investigated further. The search radius distance

ε was calculated using Equation (6).

The fraction’s numerator of equation 6 represents the maximum possible distance of of the feature space, used for clustering. In this case, three normalized features were used (n

Feats = 3). Due to normalization, the maximum distance of every feature (dist

i,max) equals to 1, so the fraction’s numerator equals to √3. This maximum distance is divided by relation of the number of TP-Events (n

TP-Events), detected by the algorithm-parameter-variant, and the numer of transients (n

TR) of the considered transient type. This setting ensures, that a sufficient area around the events is considered, to be able to identify clusters, containing 100 % TPs. If two types of events occurr for an algorithm-parameter-variant in every transient of the considered transient type (as can be seen in

Figure 10), the maximum search distance for clustering is divided by 2, enabling the clustering algorithm to create two clusters. If only one type of events is identified, the whole feature space is considered, resulting in only one cluster.

As mentioned before, we limited the resulting algorithm-parameter-variants to the ones, delivering 100 % TPs. For this reason, we needed to choose the feature cluster limits including all detected TPs on the learning day. E.g. the lower left triangle of cluster 2 in

Figure 10a has a ΔQ value of around -3 kvar. This is caused by another appliance in Q

L1,aDAQ, overlapping the event of the refrigeration plant, wich usually should have a positive ΔQ value for the transient type TR

SS1→

SS2. This can also be verified by the TPs mapped to Q

iDAQ (black points in

Figure 10). E.g. by excluding the lower left and the top right triangle in cluster 2, cluster limits would have been more narrow and would lead to less FPs outside of the TR

SS1→

SS2 areas in load identification afterwards. But then not all TPs could be identified. Through suitable combination methods of the resulting algorithm-parameter-variants (see following sections), this could be compensated. In this work, we only use the AND-logic for combination. This means, that if two algorithm-parameter-variants are combined for load identification, both have to deliver TPs for a transient, to decide for a transient to be present. By combining two algorithm-paramter-variants, not having 100 % TP individually, yet delivering 100 % TP through an OR-combintion of the variants, also individual variants with less than 100 % TPs on the learning day could have been taken into account. But this was not done in the presented work. In future, this should be investigated further.

The above described procedure was ”ppli’d to all investigated algorithm-parameter-variants, explained in the following section and for all transient types, described above. For all clusters of algorithm-parameter-variants, delivering 100 % TPs, cluster limits were extracted, according to the above, for one or more identfied clusters. In the regular NILM process, these algorithm-parameter-variants can then be applied to the considered measurement parameter (in this case PaDAQ or QaDAQ). If the resulting events range within the identified cluster limits, the presence of the specific appliance’s transient type can be concluded. If this is done for the learning day, all TPs will be identified due to the methodology described above, along with possible FPs, ranging within these limits as well.

4.3. Performance Evaluation and Algorithm-Parameter-Variants

The event detection algorithms χ²-GOF and DSC were applied to aDAQ data of the learning day for the quantities P

aDAQ and Q

aDAQ of the three phases L1, L2 and L3. For both algorithms, the input parameters window size and threshold were varied within predefined limits, described below. The performance of the resulting events, detected by these algorithm-parameter-variants, was then evaluated for the transient types TR

SS0→

SS1, TR

SS1→

SS0, TR

SS1→

SS2 and TR

SS2→

SS1 of the refrigeration plant, individually, using the performance metrics TP and FP. The transient types were derived from P

iDAQ, as described in

Section 4.1.

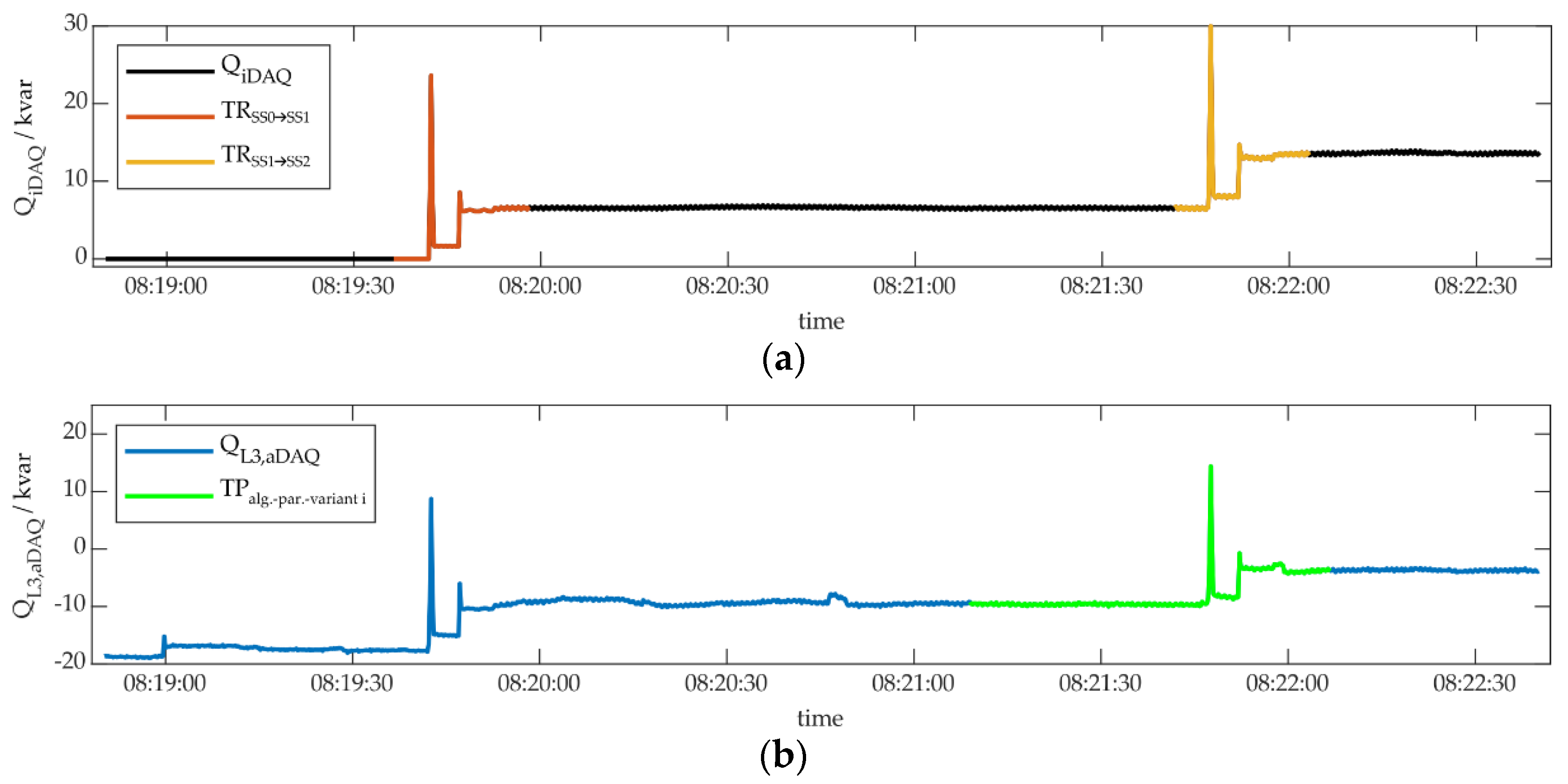

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show sections of the learning day’s iDAQ and aDAQ data, containing one transient of the type TR

SS0→

SS1 and TR

SS1→

SS2, each. Furthermore, the performance of three individual algorithm-parameter-variants is illustrated for the transient type TR

SS1→

SS2. For every algorithm-parameter-variant, that was capable of identifying events within every transient of the selected transient type (100 % TP), features were extracted and clustered. The clustering was performed to identify the features limits of the TP-events. All other events, detected by the specific algorithm-parameter-variant, outside of the areas of the considered transient, but within feature limits, were rated FP.

Figure 11b shows the performance of the event detection algorithm χ²-GOF, applied to Q

L3,aDAQ, using a window size of 15 samples and a threshold of 0.05 (algorithm-parameter-variant

i). On the whole learning day, algorithm-parameter-variant

i delivered 45 TP and 0 FP for the identification of TR

SS1→

SS2. As can be seen in

Figure 11, one rather long event was detected in the area of the transient of the type TR

SS1→

SS2. No further events were found in this section, especially not in the area of transient type TR

SS0→

SS1. The shown event was rated TP. Within the methodology of this work, events were generally rated TP, when a detected event and the considered transient shared at least one common data sample, while no other predefined transients were affected. If other transients would be affected, the event will be rated FP, even if one transient would be a TP.

The performance evaluation of another two algorithm-parameter-variants is illustrated in

Figure 12. In this case, the algorithm-parameter-variant

j (DSC, window size 11, threshold 0.7) and

k (χ²-GOF, window size 8, threshold 1.1) were applied to P

L1,aDAQ and performance was evaluated regarding TR

SS1→

SS2. As can be seen in

Figure 12b, both algorithms identified events within TR

SS0→

SS1, as well as TR

SS1→

SS2. In this case, the methodology was used for the identification of TR

SS1→

SS2 only, so the events within TR

SS0→

SS1 were rated FP. It has to be noted, that it would also have been possible to evaluate the performance for TR

SS1→

SS2 and TR

SS1→

SS2 together, then these two events would have been rated TP, as well. Besides that, algorithm-parameter-variant

j delivered one more FP, when the refrigeration plant shows no transient. Over the whole learning day both algorithms were able to identify 45 TP, while variant

j showed 366 FPs and variant

k detected 89 FPs.

Later on in

Section 4.4, the results of algorithm-parameter-variants are combined to reduce FPs. In this work, only algorithms, delivering 100 % TP, are considered for combination, so the combination also will identify all TPs, as well. If two FPs of the two algorithms range within a time duration of the length of the considered transient type (or even occur at the same time), the combined event would be rated FP. All other FPs of the individual algorithms can be removed in that way. If the two algorithms in

Figure 12b would be combined according to this logic and for the identification of TR

SS1→

SS2, the combination would be rated with one TP for the transient of the type TR

SS1→

SS2 around 8:22:00 and one FP in the area of transient type TR

SS0→

SS1 right before 8:20:00. But the first FP of algorithm-parameter-variant

j would be removed.

As described above, this procedure was carried out for two event detection algorithms (χ²-GOF and DSC), applied to two measurement quantities (P

aDAQ and Q

aDAQ) and the phases L1, L2 and L3, using varying input parameter settings for window sizes and thresholds. The performance of the resulting algorithm-parameter-variants was evaluated for specific transient types, individually. These transient types were TR

SS0→

SS1, TR

SS1→

SS2 and the two transient types TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1, combined. In

Table 5 the algorithms, measurement quantities, transient types and parameter settings used in this work, are listed.

Window sizes are listed as samples per second in

Table 5, starting at 2. Due to the reason, that in feature extraction we calculate e.g., the absolute delta of the detected events, a minimum length of 2 is required to gather reasonable results. The maximum value of the window sizes was derived from the refrigeration plant’s transient types and set to 10 samples more than the transient with the maximum duration of a certain transient type on the learning day. For the event detection algorithm χ²-GOF, [

32]. suggests to limit the maximum window size to the maximum length of the

state-transient of the individual appliance. We followed this suggestion, applied it to the event detection algorithm DSC as well, but added the above named tolerance of 10 samples.

The threshold settings had to be chosen algorithm-specific. More details for the two used algorithms can be found in

Section 1.1. The event detection algorithm DSC is based on calculating mean values of the measured parameter for two consecutive windows. Therefore, the threshold is directly related to the unit of the measured parameter. In this application 7 kW and 7 kvar were chosen as maximum threshold. Above this value, no more useful events could be detected for the refrigeration plant. This can also be estimated through

Figure 7. The threshold of the algorithm χ²-GOF is represented by the critical value of chi-square χ

2c. This statistical value is dependent on the degrees of freedom, which equals the window size minus one, when applied to NILM. In literature, tables can be found that specify χ

2c values, depending on the degrees of freedom (often listed from 1 to 100), to gather a certainty of 90, 95 or 99 %, that the distributions within the two detection windows are differing. In NILM, this is an indication for an event to be present. In our application, we used the function

chicdf in

MATLAB version R2020a to calculate χ

c2 values for window sizes up to 120, which corresponds to maximum degrees of freedom of 119, and certainties of 90, 95 and 99 %. The maximum χ

c2 value resulted in 157.8. Based on this, we set the maximum threshold for our evaluations regarding χ²-GOF to 200.

All algorithm-parameter-variants were applied to the measured quantities and phases on the learning day, listed in

Table 5. After that, features were extracted according to section 4.2, for the transient types TR

SS0→

SS1 and TR

SS1→

SS2 individually, as well as TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1 combined. Thereby, as mentioned before, only algorithm-parameter-variants delivering 100 % TPs were further evaluated regarding their number of FPs.

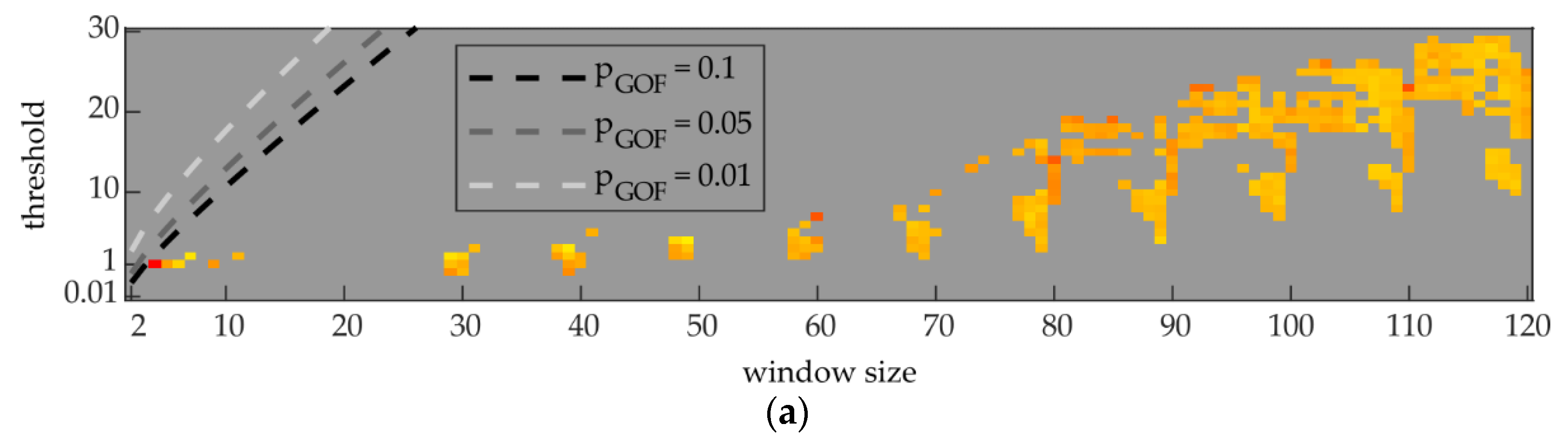

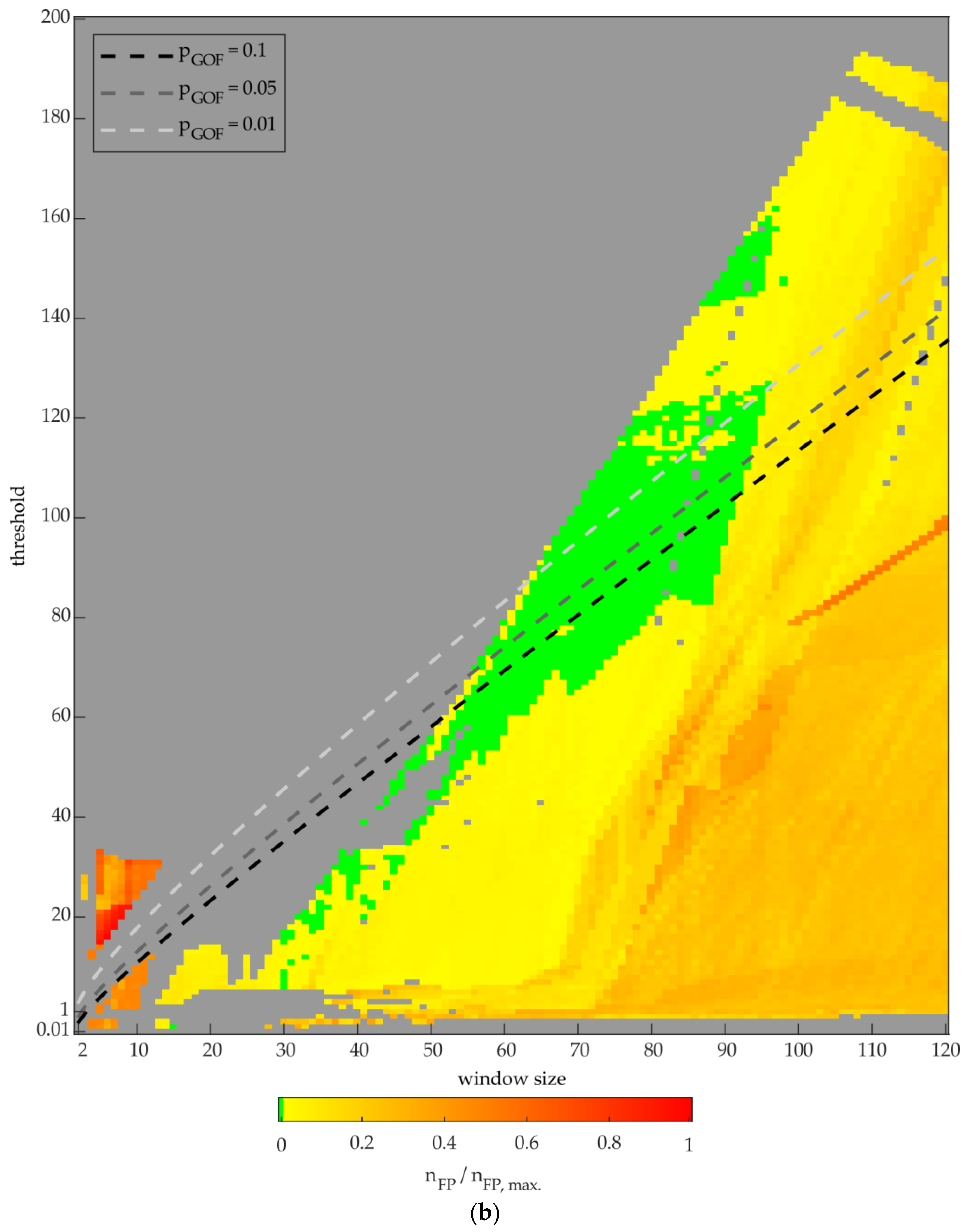

Figure 13 shows the number of FPs for the algorithm χ²-GOF applied to P

L3,aDAQ (a) and Q

L3,aDAQ (b), according to the different window sizes and thresholds listed in

Table 5, for the identification of the transient type TR

SS1→

SS2, exemplary. The algorithm-parameter-variants located in the grey areas were not capable of identifying all TPs. The colors were normalized to the maximum number of FPs in each figure.

In

Figure 13a the maximum number of FPs (n

FP,max) was 1114, in

Figure 13b 131, respectively. The χ

c2 values for the certainties of 90 (

pGOF = 0.1), 95 (

pGOF = 0.05) and 99 % (

pGOF = 0.01) were marked, depending on the window sizes (see also

Section 1.1). The threshold for the plot in

Figure 13a was limited to 30, because no more algorithm-parameter-variants with 100 % TPs occurred until a threshold of 200. It can be seen, that the overall identification performance for P

L3,aDAQ is poorer than for Q

L3,aDAQ, using χ²-GOF for this transient type and this performance evaluation method. Again, it has to be noted, that results with less than 100 % TPs can be useful as well for load identification, but are not further investigated in this work. It can be seen, that the event detection on Q

L3,aDAQ in

Figure 13b shows good results, partially with 0 FPs, even under the common

pGOF literature values for χ²-GOF.

Figure 13a is showing no 100 % TP results above the

pGOF values. As described before, the number of FPs can be reduced by combining algorithm-parameter-variants, also with variants on the phases L1 and L2, which are not shown in the figure. Therefore, even results with a relatively poor performance can be useful for load identification. This is done in

Section 4.4.

As described in section 4.2 and as it can be seen in

Figure 10, more than one feature cluster can arise from one algorithm-parameter-variant. This would be given in

Figure 13b from window sizes 4 to 12, where two clusters were identified, each. This would lead to two result columns for each of the named window sizes in

Figure 10. For these window sizes, only the better performing cluster is shown as one column per window size, because otherwise

Figure 13a,b would be inconsistent and the

pGOF lines in

Figure 13b would be unsteady. For all further evaluations, all clusters were taken into account.

It has to be noted, that two algorithm-parameter-variants with identical window sizes but different thresholds can represent identical results regarding event characteristics and feature limits. For example, if the result of χ²-GOF for an event is 100 for a certain window size, the event will be detected using all threshold settings, lower than 100 as well. On the other hand, events, detected with lower thresholds might be detected additionally. This is the case for other event detection algorithms as well. Furthermore, in some cases short window sizes can be useful, even if they show a relatively poor performance. Large window sizes lead to the detection of long events, which could cause interactions with other appliance’s events. If other appliance’s events are located close to the events of the considered appliance, large window sizes tend to detect those events as one.

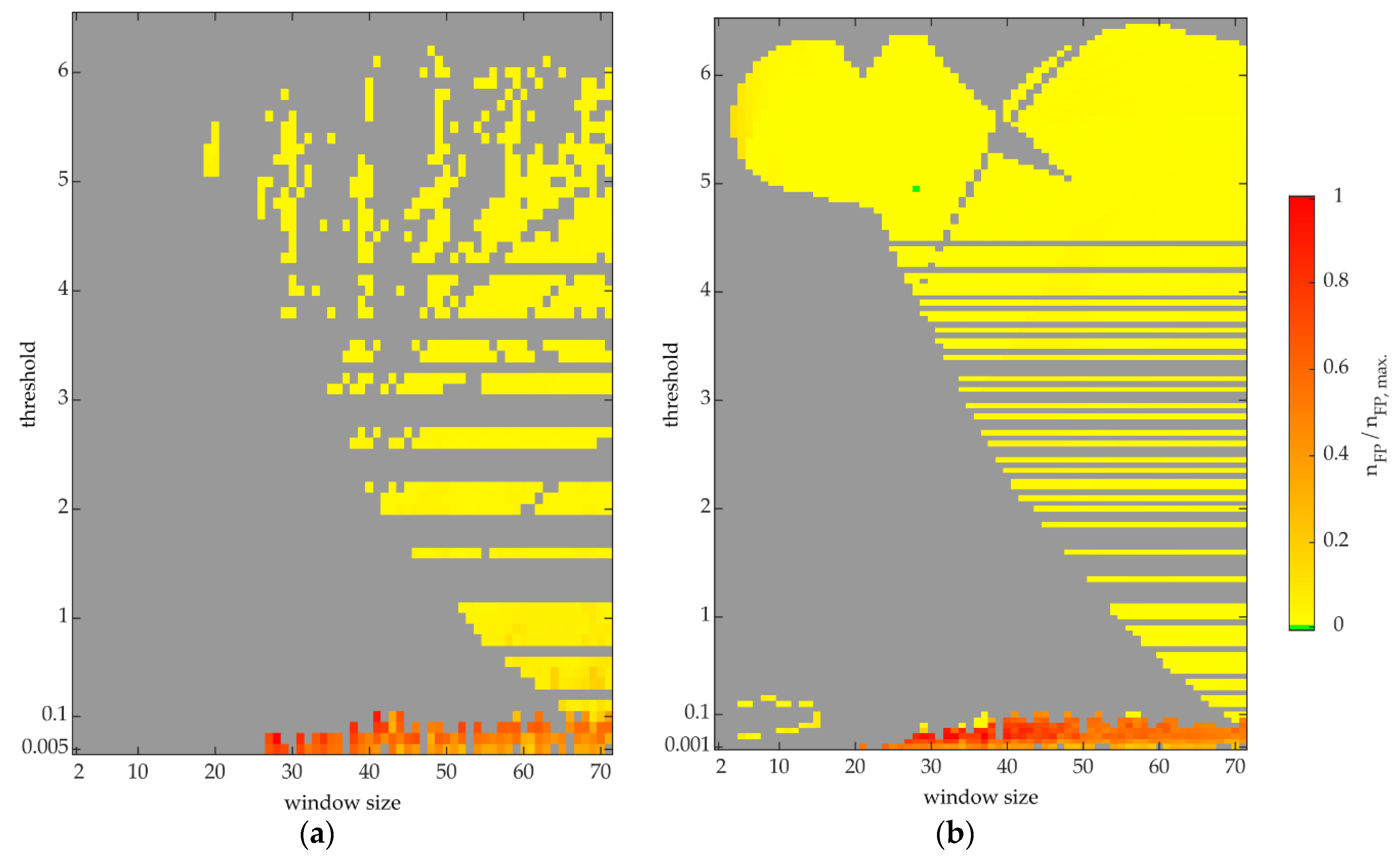

Figure 14 shows the number of FPs for the algorithm DSC applied to P

L2,aDAQ (a) and Q

L2,aDAQ (b), according to the different window sizes and thresholds listed in

Table 5, for the identification of transient type TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1, combined. The maximum number of FPs (n

FP,max) in

Figure 14a was 2006, n

FP,max in

Figure 14b was 1681. The algorithm-parameter-variants between the threshold of 6.5 and 7 are not shown in

Figure 14, because no more 100 % TP variants occurred in this area. It can be seen, that only one algorithm-parameter-variant could identify the transient types with 0 FPs, on Q

L2,aDAQ.

The results of the algorithm-parameter-variants, as shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 exemplary, were evaluated for both event detection algorithms and all variated parameters listed in

Table 5 for the learning day. This resulted in several thousand variants, delivering 100 % TPs and a varying number of FPs for the identification of each transient type. For every variant, event feature limits were extracted, according to

Section 4.2. In the regular NILM process, the algorithm-parameter-variants can be applied in the step of feature extraction. For the extracted features, the feature limits are then used in the step of load identification, to decide whether the detected events can be assigned to certain transient types of the refrigeration plant, if the detected event ranges within the feature limits. For performance improvement, several algorithm-parameter-variants can be used for load identification in combination. This is done for selected algorithm-parameter-variants in the following section. In this work, not all of the above named variants were evaluated.

4.4. Load Identification Results

In this section, load identification was performed for selected combinations of algorithm-parameter-variants, evaluated in

Section 4.3, for the transient types TR

SS0→

SS1 and TR

SS1→

SS2 individually, as well as the transient types TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1, combined. Therefore, the two testing days were used, one day with the refrigeration plant in operation, and one day where the appliance was not active. For demonstration purposes, load identification was carried out for the learning day, as well. As described above, selected algorithm-parameter-variants were applied to the three days, features were extracted for the detected events and it was examined, whether these features ranged within the previously determined feature limits. If the detected features were located within the limits, the specific refrigeration plant’s transients were considered as present. Then, the detected transients were evaluated using iDAQ ground truth, by the TP and FP metric. No algorithm-parameter-variant was capable of detecting all TPs of the given transient types, without delivering FPs on the two test days.

So different algorithm-parameter-variants had to be combined, in order to improve identification results. As described above, identification results in this work were evaluated for the three named days, only. The goal was to reduce FPs, while maintaining performance regarding TPs. Therefore, the AND-logic was used. If different algorithm-parameter-variants simultaneously delivered events within a time duration of the length of the considered transient type, these events were classified as a common events of this combination of algorithms-parameter-variants, referencing for the transient type, to be identified. Due to the fact, that the results contained nothing but variants providing 100 % TPs on the learning day, it was ensured, that AND-combinations of those results provided 100 % TPs on the learning day, as well. FP-events could be eliminated that way, except being located in a common area of the length of the considered transient type. Again, it has to be noted, that other combination methods might be useful for the application of the presented methodology, but were not applied in this work.

In the following, different combination variants were selected for the identification of different transient types.

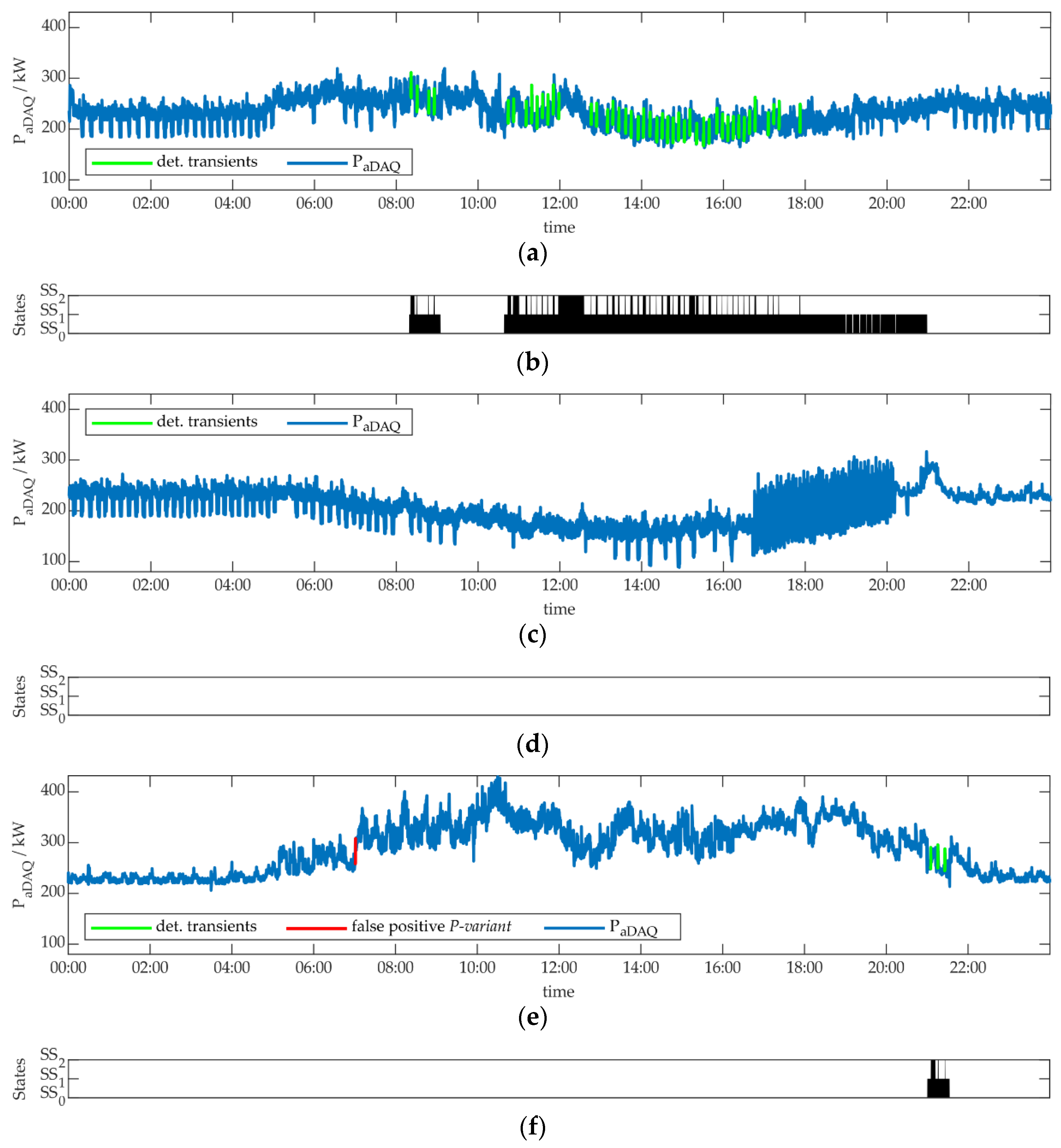

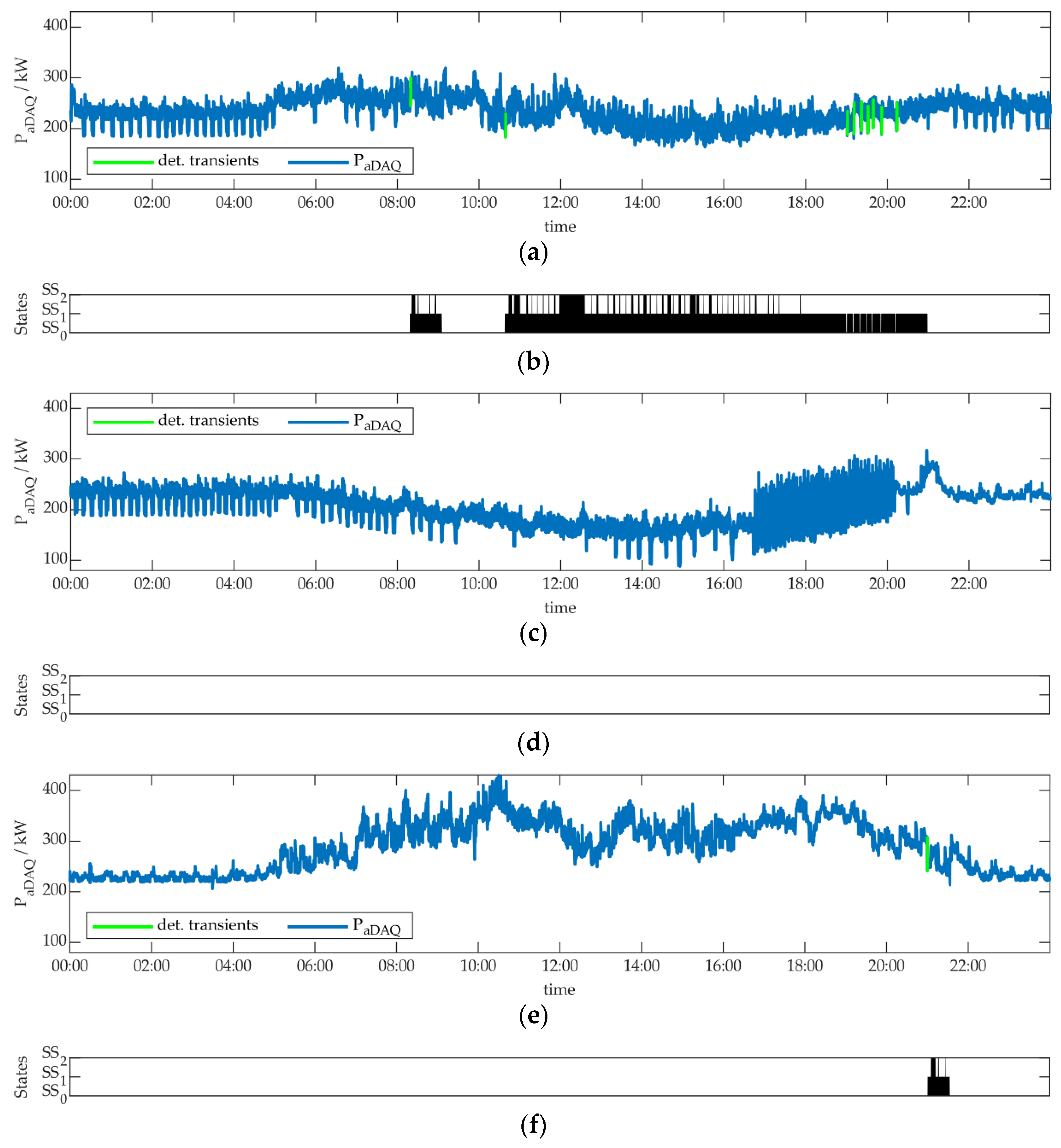

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show the load identification results for the transient types TR

SS1→

SS2 and TR

SS0→

SS1, as well as TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1, combined, and for the identification variants, listed in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Table 6 lists three different combination variants for the identification of the transient type TR

SS1→

SS2, using the algorithm χ²-GOF, as well as the identifed feature limits. For the combination variant

Q-variant I, the single best performing algorithm-parameter-variants for the measurement parameter Q

aDAQ on the phases L1, L2 and L3 were selected and combined. The variant for Q

L2,aDAQ can be seen in

Figure 13b also. All three variants identified 100 % TPs and 0 FPs on the learning day individually, yet not on the two test days.

For

Q-variant II, variants with small window sizes and low thresholds were chosen. For the

P-variant, all 1058 algorithm-parameter-variants, using the measured parameter P

aDAQ (on L1, L2 or L3) and delivering 100 % TPs on the learning day were selected and reduced by the ones, not delivering 100 % TPs on the test day with appliance operation. The resulting 830 variants were combined. The identified feature limits on the learning day are listed in

Table 6 also, except for the

P-variant, due to the large number of variants.

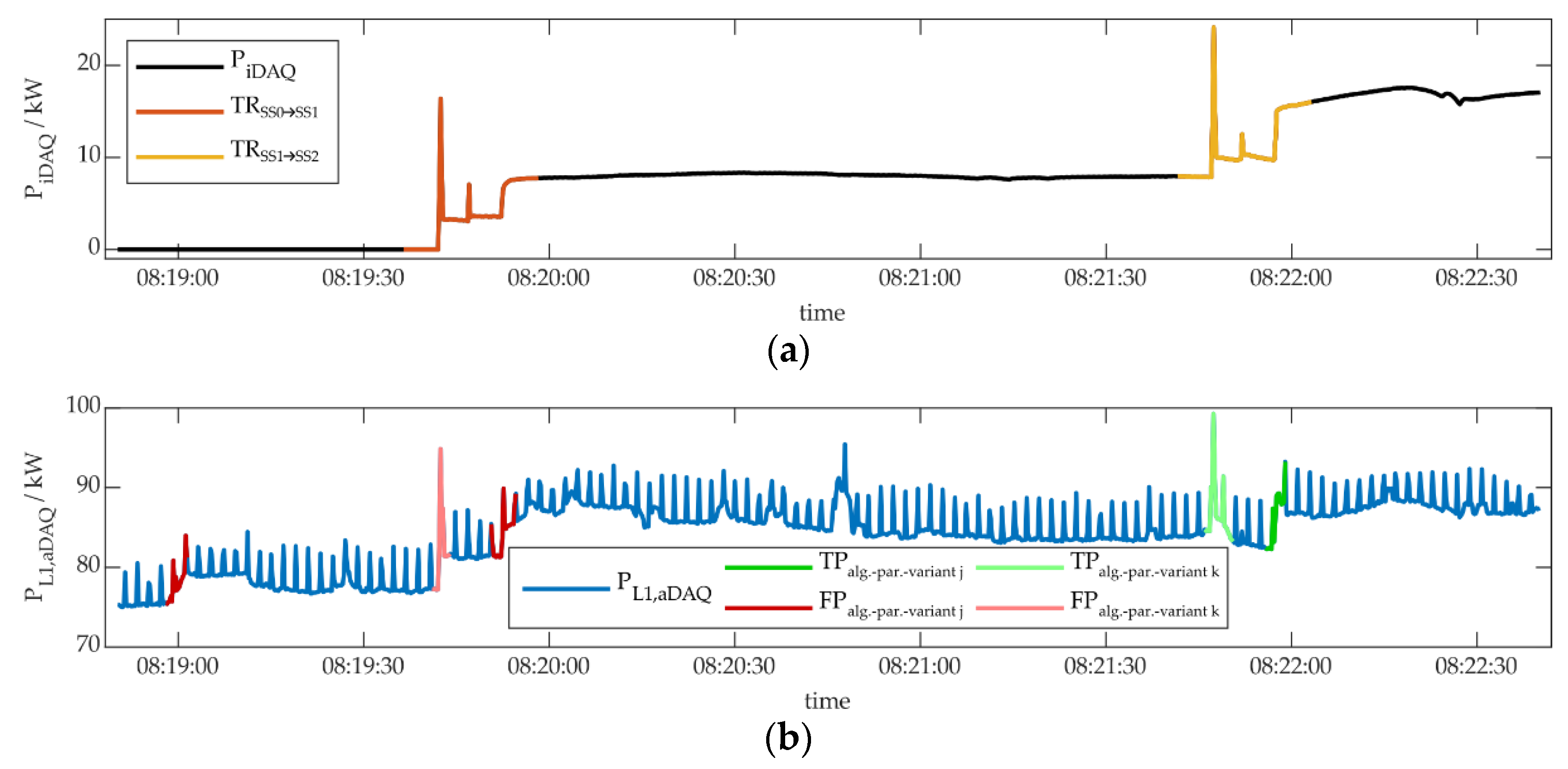

Figure 15 shows the identification results of the three named combination variants. For illustration purposes, the measurement parameter P

aDAQ, as an addition of P

L1,aDAQ, P

L2,aDAQ and P

L3,aDAQ, was shown for the learning day (a) and the two test days (c) and (e). In

Figure 15b,d,f the operation behavior of the refrigeration plant is displayed for the three days. It can be seen, that all three combination variants were capable of identifying all transients of the type TR

SS1→

SS2 (green transients). The

P-variant, consisting of a combination of 830 single algorithm-parameter-variants, still shows one FP on the second test day, marked in red.

In

Table 7, only one combination variant for the identification of the transient type TR

SS0→

SS1 is listed. In this case, one algorithm-parameter-variant using χ²-GOF for each measured parameter of Q

aDAQ and P

aDAQ was used. Here, the best performing variants with window sizes lower than 10 (or 2 s) were combined for every phase and measurement parameter. As mentioned earlier, this can be beneficial when other appliance events are located near to the desired appliance transient and variants with larger window sizes are not capable of separating these events. This was the case on the test day with appliance operation for this transient. The variant shows optimal identification results for the three considered days, as can be seen in

Figure 16.

The transient types TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1 were identified in common. This was done to illustrate the area of application of the methodology, exemplary. Even if certain transients are separated in the clustering process of appliance model building, they can be analyzed together in the following steps of the methodology. This enables the application of other modelling approaches, independently from the general methodology. As described in

Section 4.1, appliance model building is done rather manually in this work. The further concept of the methodology was developed independent from model building.

For the identification of the transient types TR

SS1→

SS0 and TR

SS2→

SS1, variants of the algorithm DSC were used.

Table 8 lists the

DSC-variant. The combination of the best performing variants for P

L1,aDAQ, P

L2,aDAQ and P

L3,aDAQ were not sufficient for identifying this transient types optimally, so one variant on Q

L2,aDAQ was added, exemplary. This was the only variant of the algorithm DSC with 0 FPs on the learning day. The variant can also be seen in

Figure 14b.

Figure 17 illustrates the identification results of the

DSC-variant. All transients could be identified on all three considered days, whereby no FPs were detected.

As mentioned before, this identification results were evaluated for combinations of selected algorithm-parameter-variants. The goal was to demonstrate various application possibilities of the provided methodology, not to analyze all algorithm-parameter-variants entirely. Furthermore, only three measurement days were used for demonstration purposes. In future, the methodology should be applied to more comprehensive data, e.g., NILM datasets, a wider range of features and further NILM algorithms, including eventless NILM approaches. In the following

Section 5 a conclusion of the findings of this work is given. Future work will be outlined, as well.