Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Expansion of Environmental Fingerprinting into Virtual Worlds. Pioneering application in the Metaverse, our work extends the concept of environmental fingerprinting beyond physical and network security into virtual DT environments, an unexplored area.

- Protection of Critical Infrastructure. Contributing to smart grid security by proposing a novel authentication mechanism that bridges the physical and virtual worlds and addressing a critical gap in existing security measures against Deepfake attacks in critical infrastructure systems.

- Practical Implementation and Validation through a Smart Grid Case Study. The application of ANCHOR-Grid in a virtual Internet of Smart Grid Things (IoSGT) setting demonstrates the real-world relevance and necessity of the technique.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Data Security in Metaverse

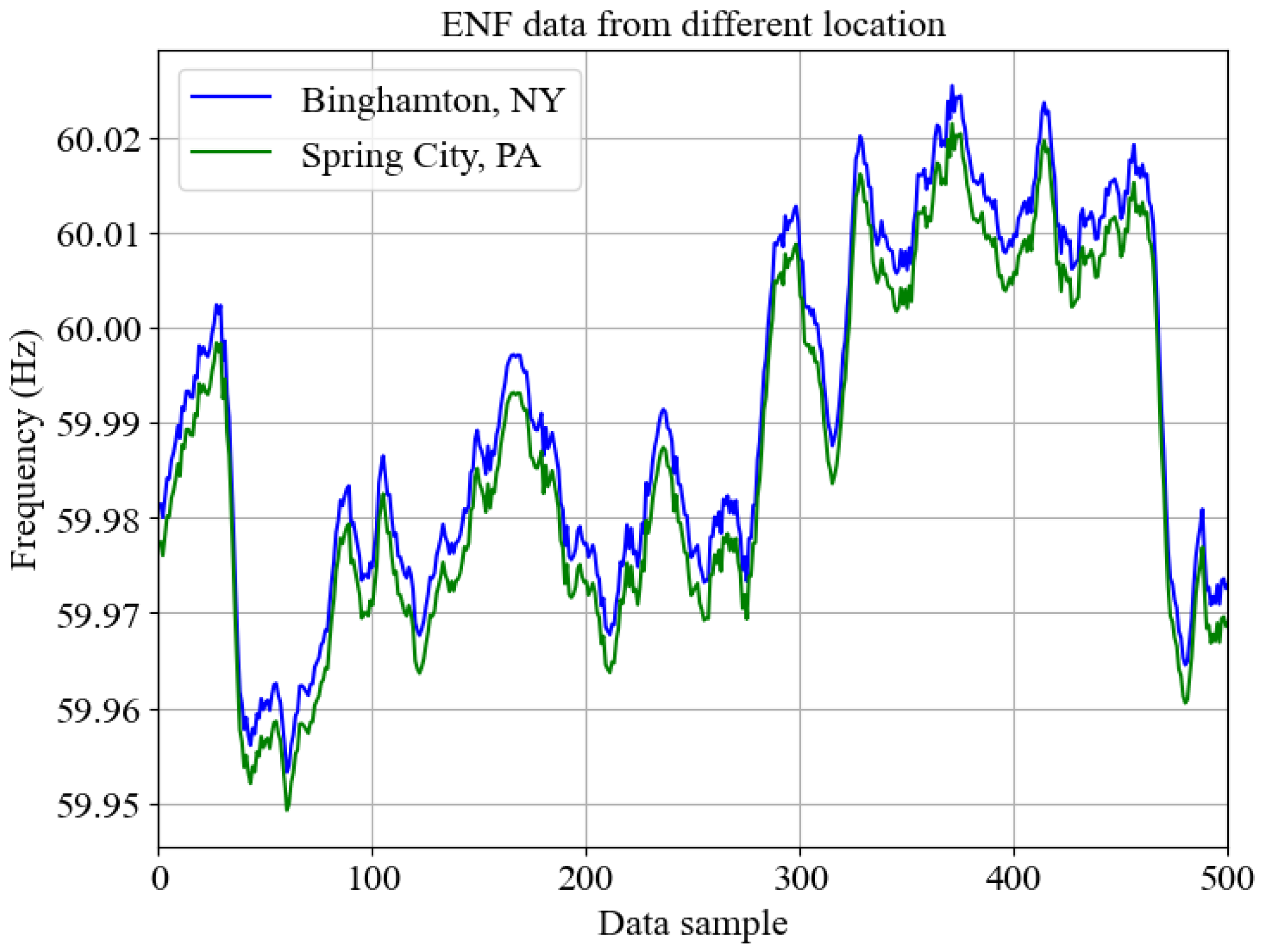

2.2. ENF Signals as an Environmental Fingerprint

2.3. Digital Twins in Smart Grids

3. ANCHOR-Grid: Rationale and Design

3.1. Architecture Overview

- Location 1 is an industrial environment with various facilities connected to the power grid (black solid lines). The data network links each facility to the cloud, enabling data aggregation, including ENF readings from this location. The ENF data is a unique identifier consistent across all locations connected to the same power grid, making it a reliable feature for detecting data manipulations.

- Location 2 represents a residential area, including homes and electric vehicle charging stations. The ENF signature captured here provides a unique, location-specific electrical frequency profile that can be cross-referenced with data from other locations for consistency. The ENF signal helps verify the authenticity of data and prevent malicious deepfake attacks.

- Location 3 shows a specialized industrial and research facility. This location integrates advanced facilities that rely heavily on smart grid technologies, and ENF anchors can help ensure that data from this sensitive location is secure. Any inconsistencies in the ENF signal can indicate potential deepfake attempts or tampering.

3.2. Rationale of ANCHOR-Grid

3.3. ENF-based Authentication Module

4. Security Monitoring for Smart Grid

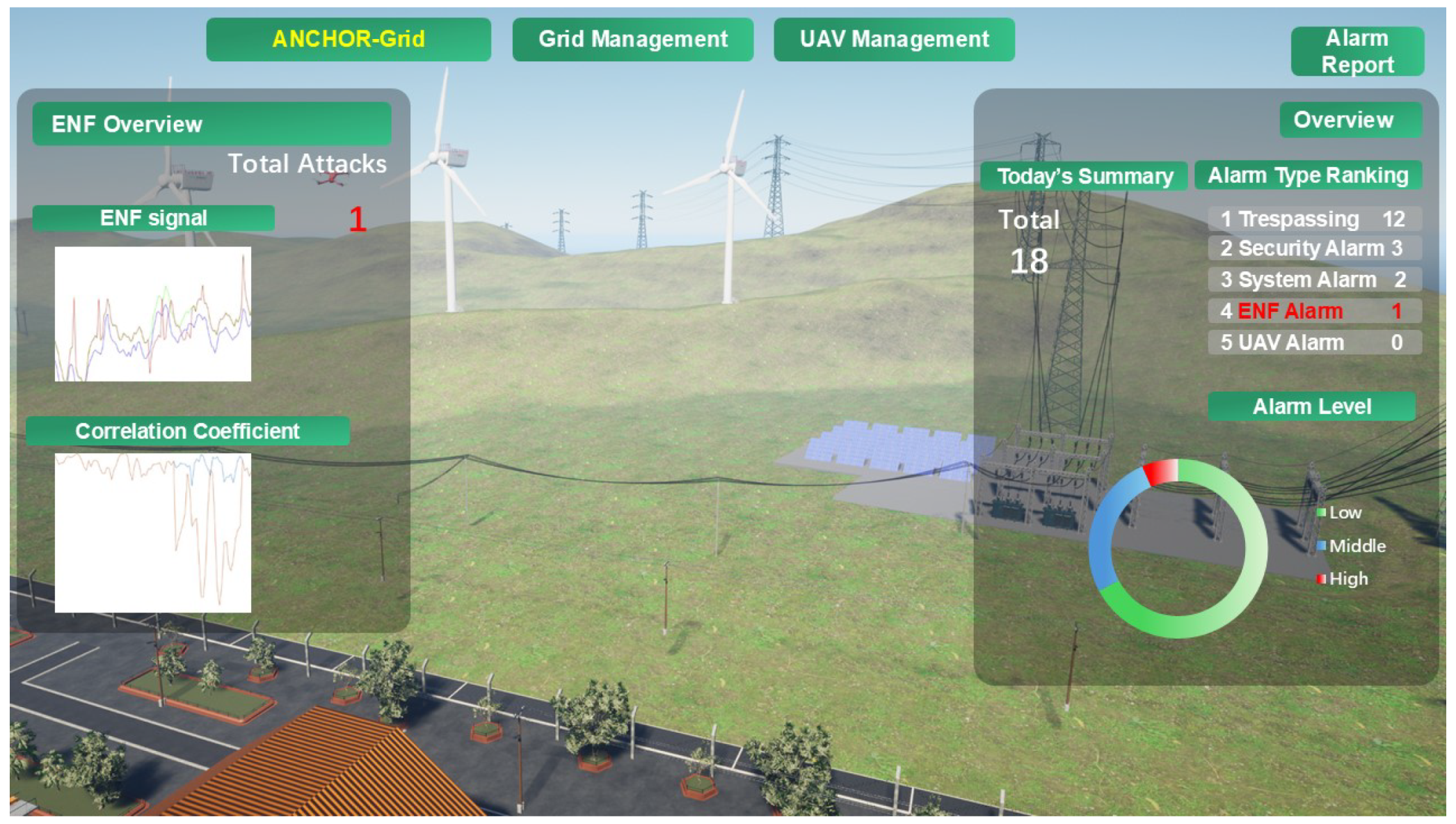

4.1. ANCHOR-Grid Microverse

4.2. Micorgrid Monitoring in Microverse

4.2.1. Digital Twin Integration and Real-Time Data Acquisition

4.2.2. Operational Analysis and Real-Time Monitoring

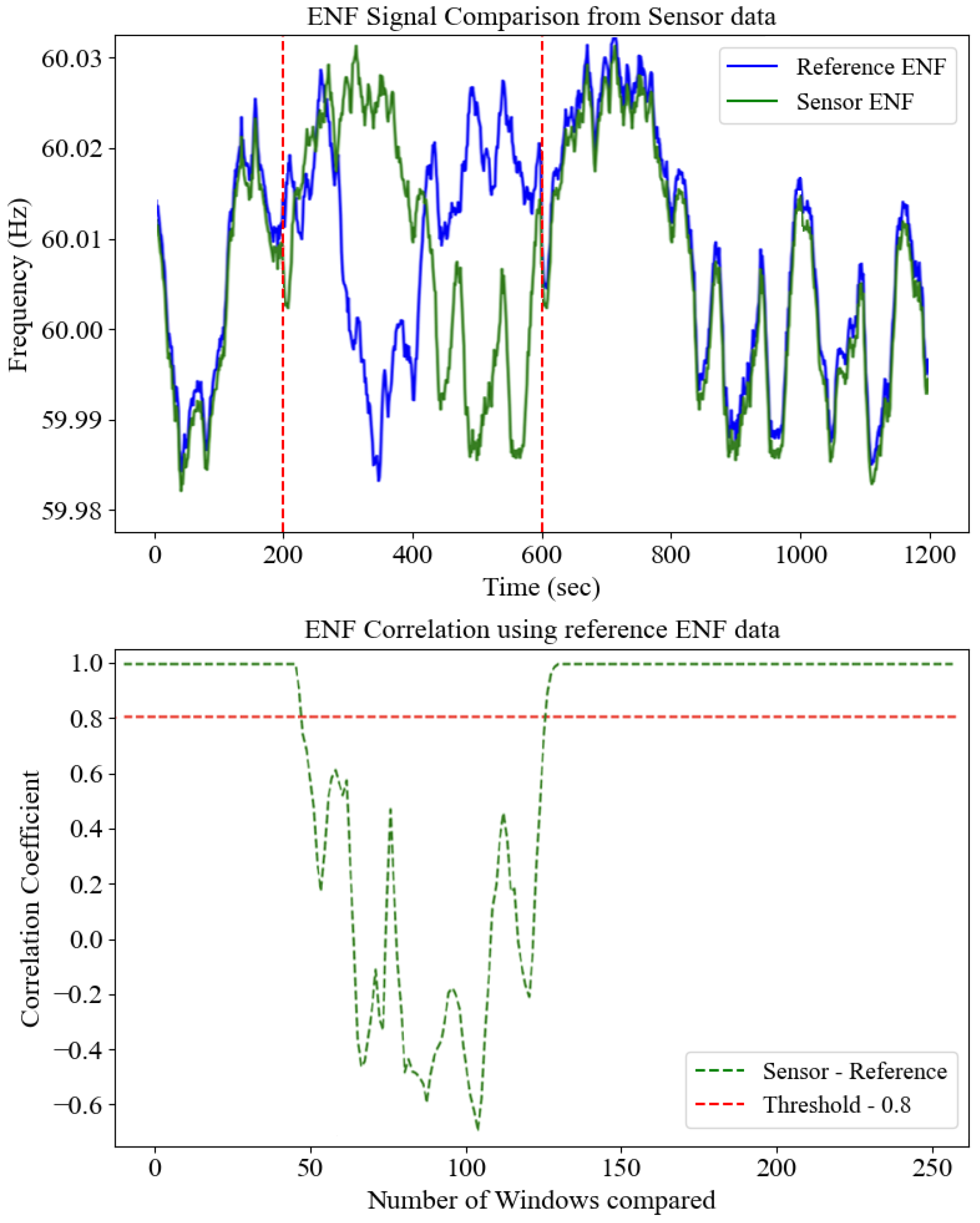

4.2.3. Security Monitoring and Attack Detection

5. Experimental Study

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.1. Physical Testbed

5.1.2. ENF-based Signature

- Extracting ENF Data Window: A window of ENF data is extracted from the power grid. The specific security requirements determine the length of the window—typically, a 10-second window is used, during which the ENF value is sampled every second. This yields a sequence of ENF values, e.g., [60.01, 59.98, 60.02, 59.99, 59.97, ...].

- Normalizing the ENF Data: To prepare the data for signature generation, min-max normalization is applied to scale the ENF values between 0 and 1. This helps in maintaining consistency across different environments. For instance, if is 59.96 and is 60.03, each value in the sequence is normalized as:

- Smoothing the ENF Data: Given that ENF data can be noisy, a moving average technique is used to smooth the sequence. This removes minor fluctuations, making the resulting signature more robust. Using a 3-point moving average, the smoothed sequence might look like [0.428, 0.619, 0.524, ...].

-

Hashing to Generate a Fixed-Length Signature: The smoothed ENF sequence is concatenated into a single string and then hashed using a cryptographic hash function, such as SHA-384, to generate a fixed-length ENF signature. This signature acts as a watermark that ties data to real-world conditions in the grid. For instance, the hash output might look like:

-

Generating data packet structure with JSON format typically includes metadata such as packet ID, device ID, timestamp, and the data payload (e.g., sensor readings). The data packet structure is as follows:

- -

- Packet ID: A unique identifier, e.g., "P164205785600".

- -

- Device ID: The identifier for the originating device, e.g., "Device01".

- -

-

Timestamp: When the packet was generated,e.g., "2024-11-11T12:30:45Z".

- -

-

Data Payload: Sensor readings or measurements,e.g., {"temperature": 25.4, "power_usage": 12.5}.

Once the data packet is generated, it is serialized to a JSON string and hashed using a cryptographic hash function, such as SHA-384, to produce a fixed-length message. Afterward, the ENF signature is combined with the hashed packet to form the final message. For the combination process, three approaches were followed:- -

- Concatenation: Concatenate the two hashed values, deciding the order based on the timestamp. For example, if the timestamp is even, ; otherwise, .

- -

- Interleaving: Use an empty list to store the combined result. Generate the message by iterating through each bit or byte of Hash1 and Hash2, appending them according to the interleaving rule determined by the timestamp. For example, if the timestamp is even, start by appending a byte from Hash1, followed by a byte from Hash2, and repeat.

- -

- Pseudorandom Number Generator (PRNG): SHA-384 produces a hash of 48 bytes (or 96 hexadecimal characters). First, we generate a seed number based on the milliseconds of the time we used in the packet to create 48 fixed random numbers within the range [0, 95]. These numbers are then used to place and into a 96-byte vector, which is subsequently sent to the server as a message.

At first, we applied each approach independently. Then, to enhance the randomness of the , we employed a random combination sequence approach, utilizing different methods to create the message. This combination is derived from five approaches: two strategies for concatenation, two for interleaving, and one using the PRNG. One of these approaches is randomly selected (based on the seed number used in the PRNG) to generate the final message. Then, the final message is hashed and encapsulated in a JSON packet for transmission to the server.

5.1.3. Evaluation Model

5.1.4. Methodology

- Step 1: Defining Clear Metrics and Objectives.

- Step 2: Establishing a Baseline.

- Step 3: Creating a Diverse Test Dataset.

- Step 4: Performing Controlled Experiments.

5.1.5. Evaluation

5.2. Experimental Results

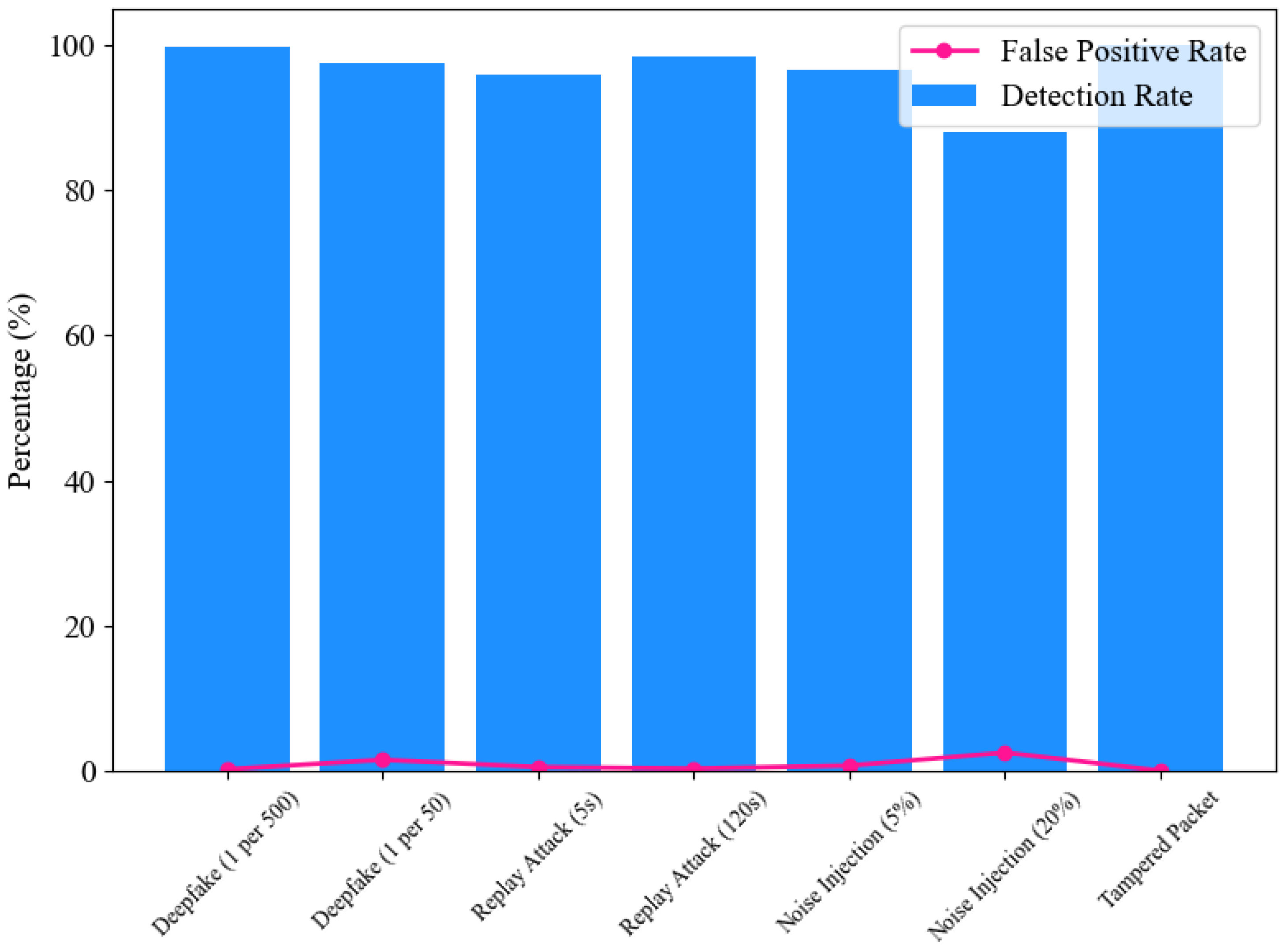

5.2.1. Detection Rates and False Positives

5.2.2. Robustness Under Network Conditions

5.2.3. Comparison between ANCHOR-Grid and Existing Security Mechanisms

| Feature | ANCHOR-Grid Framework | Cryptographic Signatures [16] | Threshold-Based Anomaly Detection [18] | AES Encryption [20] | Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) [9] | Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) [25] |

| Core Authentication Method | Uses Electric Network Frequency (ENF) signals as environmental fingerprints. | Generates fixed-length signatures for data integrity. | Monitors specific parameters for anomalies. | Encrypts data payloads for confidentiality. | Provides secure key exchange and signing. | Detects attack patterns via traffic analysis. |

| Adaptability | Highly adaptable to dynamic, evolving threats like deepfake and replay attacks. | Static; vulnerable to replay and adaptive attacks. | Ineffective against crafted or evolving threats. | Focused on encryption, not adaptability. | Limited to predefined patterns. | Struggles with novel and adaptive threats. |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Application Programming Interfaces | APIs |

| Artificial Intelligence | AI |

| Dynamic Data Driven Application Systems | DDDAS |

| Digital Twins | DT |

| Elliptic Curve Cryptography | ECC |

| Electric Network Frequency | ENF |

| Energy Storage Systems | ESS |

| False Negative Rate | FNR |

| False Positive Rate | FPR |

| Internet of Smart Grid Things | IoSGT |

| Internet of Things | IoT |

| Intrusion Detection Systems | IDS |

| Long Short Tem Memory | LSTM |

| Printed Circuit Board | PCB |

| Pseudorandom Number Generator | PRNG |

| Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition | SCADA |

| Unreal Engine 5 | UE5 |

| User Interface | UI |

| Unreal Motion Graphics | UMG |

References

- Hatami, M.; Qu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Kholidy, H.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E. A Survey of the Real-Time Metaverse: Challenges and Opportunities. Future Internet 2024, 16, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, A.T.; Supangkat, S.H. Metaverse fundamental technologies for smart city: A literature review. 2022 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–7.

- Wang, H.; Ning, H.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W.; Dhelim, S.; Farha, F.; Ding, J.; Daneshmand, M. A survey on the metaverse: The state-of-the-art, technologies, applications, and challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 14671–14688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Wu, N.; Chen, S.; Han, B. Will metaverse be nextg internet? vision, hype, and reality. IEEE Network 2022, 36, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Weng, Y.; Vittal, V.; Blasch, E. Distribution grid topology and parameter estimation using deep-shallow neural network with physical consistency. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2023, 15, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Z.; Zhang, N.; Xing, R.; Liu, D.; Luan, T.H.; Shen, X. A survey on metaverse: Fundamentals, security, and privacy. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2022.

- Wang, J.; Makowski, S.; Cieślik, A.; Lv, H.; Lv, Z. Fake news in virtual community, virtual society, and metaverse: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiu, P.; Nitti, M.; Pilloni, V.; Cadoni, M.; Grosso, E.; Fadda, M. Metaverse & Human Digital Twin: Digital Identity, Biometrics, and Privacy in the Future Virtual Worlds. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2024, 8, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, G.; Kumar, P.; Chen, C.M.; Vasilakos, A.V.; Prajapat, S.; others. A robust privacy-preserving ecc-based three-factor authentication scheme for metaverse environment. Computer Communications 2023, 211, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasch, E.; Al-Nashif, Y.; Hariri, S. Static versus dynamic data information fusion analysis using DDDAS for cyber security trust. Procedia Computer Science 2014, 29, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.B.; Gaurav, A.; Arya, V. Fuzzy logic and biometric-based lightweight cryptographic authentication for metaverse security. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 164, 111973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagothu, D.; Poredi, N.; Chen, Y. Evolution of Attacks on Intelligent Surveillance Systems and Effective Detection Techniques. In Intelligent Video Surveillance-New Perspectives; IntechOpen, 2022.

- Abdelkader, S.; Amissah, J.; Kinga, S.; Mugerwa, G.; Emmanuel, E.; Mansour, D.E.A.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L. Securing modern power systems: Implementing comprehensive strategies to enhance resilience and reliability against cyber-attacks. Results in engineering 2024, p. 102647.

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Wang, Z. Progress in self-powered, multi-parameter, micro sensor technologies for power metaverse and smart grids. Nano Energy 2023, p. 108959.

- Tatipatri, N.; Arun, S. A Comprehensive Review on Cyber-attacks in Power Systems: Impact Analysis, Detection and Cyber security. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagothu, D.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Aved, A. Deterring deepfake attacks with an electrical network frequency fingerprints approach. Future Internet 2022, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagothu, D.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Aved, A. Defakepro: Decentralized deepfake attacks detection using enf authentication. IT Professional 2022, 24, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Dabbaghjamanesh, M.; Karimi, M. A survey on deep learning role in distribution automation system: a new collaborative Learning-to-Learning (L2L) concept. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 81220–81238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, R.U.; Paulchamy, B.; Pandey, B.K.; Pandey, D. Enhancing Sensing and Imaging Capabilities Through Surface Plasmon Resonance for Deepfake Image Detection. Plasmonics 2024, pp. 1–20.

- Mirzaee, P.H.; Shojafar, M.; Cruickshank, H.; Tafazolli, R. Smart grid security and privacy: From conventional to machine learning issues (threats and countermeasures). IEEE access 2022, 10, 52922–52954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, D.S.; Hajjar, A.E.; Jahankhani, H. Deepfakes in Social Engineering Attacks. In Space Law Principles and Sustainable Measures; Springer, 2024; pp. 153–183.

- Mustak, M.; Salminen, J.; Mäntymäki, M.; Rahman, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Deepfakes: Deceptions, mitigations, and opportunities. Journal of Business Research 2023, 154, 113368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawili, R.; AlQahtani, A.A.S.; Khan, M.K. Comprehensive survey: Biometric user authentication application, evaluation, and discussion. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 119, 109485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnoo, M.A.; Anwar, A.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; Islam, S.N.; Mahmood, A.N.; Doss, R. False data injection threats in active distribution systems: A comprehensive survey. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 140, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, V.L.; Hwang, R.H.; Kuo, J.J.; Chen, Y.W.; Huang, C.C.; Pan, P.I. Towards Secured Smart Grid 2.0: Exploring Security Threats, Protection Models, and Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2024.

- Ngharamike, E.; Ang, L.M.; Seng, K.P.; Wang, M. ENF based digital multimedia forensics: Survey, application, challenges and future work. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 101241–101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Rashid, M.; Li, H.; Javed, A.R.; Gadekallu, T.R. Artificial intelligence and blockchain technology for secure smart grid and power distribution Automation: A State-of-the-Art Review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 57, 103282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Hung, D.V.; Davis, W.; Towakel, P.; Raza, M.; Karamanoglu, M.; Barn, B.; Shetve, D.; Prasad, R.V.; others. Digital twins: A survey on enabling technologies, challenges, trends and future prospects. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2022, 24, 2255–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.K.; Reddy, K.K.; Kathrine, G.J.W. Smart Grid Protection with AI and Cryptographic Security. 2024 3rd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 246–251.

- Qu, Q.; Xu, R.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Sarkar, S.; Ray, I. A Digital Healthcare Service Architecture for Seniors Safety Monitoring in Metaverse. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom). IEEE, 2023, pp. 86–93.

- Yang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Youliang, T.; Ma, J. A secure authentication framework to guarantee the traceability of avatars in metaverse. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2023, 18, 3817–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.A.; Ouahada, K.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. A review of machine learning approaches to power system security and stability. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 113512–113531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, C. Applications of ENF criterion in forensic audio, video, computer and telecommunication analysis. Forensic Science International 2007, 167, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; You, S.; Yao, W.; Cui, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. A Distribution Level Wide Area Monitoring System for the Electric Power Grid–FNET/GridEye. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajj-Ahmad, A.; Garg, R.; Wu, M. Instantaneous frequency estimation and localization for ENF signals. Proceedings of The 2012 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference, 2012, pp. 1–10.

- Nagothu, D.; Xu, R.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E. Application of Electrical Network Frequency as an Entropy Generator in Distributed Systems. NAECON 2023-IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference. IEEE, 2023, pp. 233–238.

- Nagothu, D.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Aved, A.; Zhu, S. Detecting malicious false frame injection attacks on surveillance systems at the edge using electrical network frequency signals. Sensors 2019, 19, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boschert, S.; Rosen, R. Digital twin—the simulation aspect. Mechatronic futures: Challenges and solutions for mechatronic systems and their designers 2016, pp. 59–74.

- Darema, F.; Blasch, E.; Ravela, S.; Aved, A.J. Handbook of Dynamic Data Driven Applications Systems; Vol. 2, Springer, 2023.

- Hatami, M.; Nasab, M.A.; Chen, Y.; Mohammadi, J.; Cruz, E.A.; Blasch, E. Optimizing Energy Storage Systems Deployment in Smart Grids. 2024 IEEE ANDESCON. IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Kumari, N.; Sharma, A.; Tran, B.; Chilamkurti, N.; Alahakoon, D. A comprehensive review of digital twin technology for grid-connected microgrid systems: State of the art, potential and challenges faced. Energies 2023, 16, 5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasch, E. Digital Twins for Cognitive Situation Awareness. 2024 IEEE Conference on Cognitive and Computational Aspects of Situation Management (CogSIMA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 63–70.

- Mchirgui, N.; Quadar, N.; Kraiem, H.; Lakhssassi, A. The Applications and Challenges of Digital Twin Technology in Smart Grids: A Comprehensive Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, M.; Nasab, M.A.; Chen, Y.; Mohammadi, J.; Ardiles-Cruz, E.; Blasch, E. ELOCESS: An ESS Management Framework for Improved Smart Grid Stability and Flexibility. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2024, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Djebali, S.; Guerard, G.; Taleb, I. Survey and insights on digital twins design and smart grid’s applications. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, M.A.; Hatami, M.; Zand, M.; Nasab, M.A.; Padmanaban, S. Demand side management programs in smart grid through cloud computing. Renewable Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Chen, T.; Karimi, M. A review on digital twin technology in smart grid, transportation system and smart city: Challenges and future. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 17471–17484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanaban, S.; Nasab, M.A.; Milani, O.H.; Zand, M.; Hatami, M.; Nasab, M.A.; Khalili, M. Robust Rearrangement of Interconnected Microgrids to Reduce the Effects of Physical Cyberattacks on Intelligent Distribution Networks. Biomass and Solar-Powered Sustainable Digital Cities 2024, pp. 339–362.

- Padmanaban, S.; Nasab, M.A.; Hatami, M.; Milani, O.H.; Dashtaki, M.A.; Nasab, M.A.; Zand, M. The Impact of the Internet of Things in the Smart City from the Point of View of Energy Consumption Optimization. Biomass and Solar-Powered Sustainable Digital Cities 2024, pp. 81–122.

- Kabir, M.R.; Halder, D.; Ray, S. Digital Twins for IoT-driven Energy Systems: A Survey. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasch, E.; Sabatini, R.; Roy, A.; Kramer, K.A.; Andrew, G.; Schmidt, G.T.; Insaurralde, C.C.; Fasano, G. Cyber awareness trends in avionics. 2019 IEEE/AIAA 38th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–8.

- Qu, Q.; Hatami, M.; Xu, R.; Nagothu, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Blasch, E.; Ardiles-Cruz, E.; Chen, G. The Microverse: A Task-Oriented Edge-Scale Metaverse. Future Internet 2024, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; Blasch, E.; Pham, K.; Shen, D.; Chen, G. A holistic cloud-enabled robotics system for real-time video tracking application. Future Information Technology: FutureTech 2013. Springer, 2014, pp. 455–468.

| Attack Type | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ANCHOR-Grid | Baseline | ANCHOR-Grid | |

| Deepfake (1 per 500) | 91 | 99.8 | 85 | 99.8 |

| Deepfake (1 per 50) | 88 | 98.4 | 80 | 97.5 |

| Replay Attack (5s old) | 75 | 99.5 | 70 | 94 |

| Replay Attack (120s old) | 85 | 99.7 | 80 | 98.5 |

| Noise Injection (5% Noise) | 78 | 99.2 | 70 | 96 |

| Noise Injection (20% Noise) | 65 | 97.1 | 60 | 85 |

| Tampered Packet | 90 | 100 | 85 | 100 |

| Network Condition | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low Latency (<5ms) | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Medium Latency (50ms) | 99.2 | 98.5 |

| High Latency (200ms) | 95.4 | 95 |

| Packet Loss (1%) | 99.5 | 98 |

| Packet Loss (5%) | 96.7 | 90 |

| Jitter (Low) | 99.4 | 97 |

| Jitter (High) | 95.6 | 88 |

| Robustness Against Deepfake | Differentiates fake data by leveraging ENF signals as anchors. | Vulnerable to fakedata injection. | Ineffective; detects only gross anomalies. | Ineffective against data manipulation. | Cannot handle mimicked legitimate behavior. | Detects deepfakes poorly unless explicitly trained for them. |

| Replay Attack Resilience | Detects replay attacks using temporal ENF correlations. | Timestamping helps, but spoofing is possible. | No inherent protection. | No inherent protection. | Limited unless integrated with timestamps. | May detect replay patterns via anomalies in traffic flow. |

| Noise Resilience | Maintains accuracy (>85%) under moderate noise. | Struggles as noise impacts static thresholds. | Ineffective as noise affects parameter detection. | Noise has no direct impact. | Moderate noise can degrade detection. | Performance degrades significantly if noise mimics legitimate traffic. |

| Real-Time Detection | Lightweight supports decentralized real-time detection. | Real-time but static in capability. | Real-time but limited to thresholds. | Not designed for real-time response. | Real-time but with heavy computation. | Real-time detection but computationally expensive at scale. |

| Computational Efficiency | Lightweight, scalable for IoT and distributed systems. | Moderate; computationally efficient. | Highly efficient for static thresholds. | Computationally intensive for IoT devices. | Computationally intensive at scale. | Heavy processing for real-time traffic analysis. |

| Scalability | Decentralized ENF signals enable scalability. | Scales well for simple setups. | Simple and scalable for static systems. | Less scalable due to key management. | Limited scalability for complex systems. | Requires substantial infrastructure for large-scale networks. |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate; ENF signal extraction requires specialized hardware but avoids heavy cryptographic dependency. | Simple implementation; relieson hashing algorithms. | Simple but dependent on predefined values. | Complex due to cryptographic operations. | Complex; requires network traffic monitoring. | Implementation requires signature updates and frequent maintenance. |

| Integration with IoT Devices | Designed for lightweight IoT integration using ENF-based signatures. | Moderate; IoT-compatible hashing. | Easily deployable but lacks dynamic protection. | Requires resources unsuitable for IoT. | Resource-intensive for IoT systems. | Overhead limits practical IoT deployment without optimization. |

| Primary Limitation | Sensitive to extreme noise (>20%), reducing detection accuracy. | Vulnerable to replay attacks and stolen keys. | Fails against dynamic, adaptive threats. | Resource-heavy for constrained devices. | Ineffective for novel attacks. | Requires retraining for emerging attack vectors; labor-intensive. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).