Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

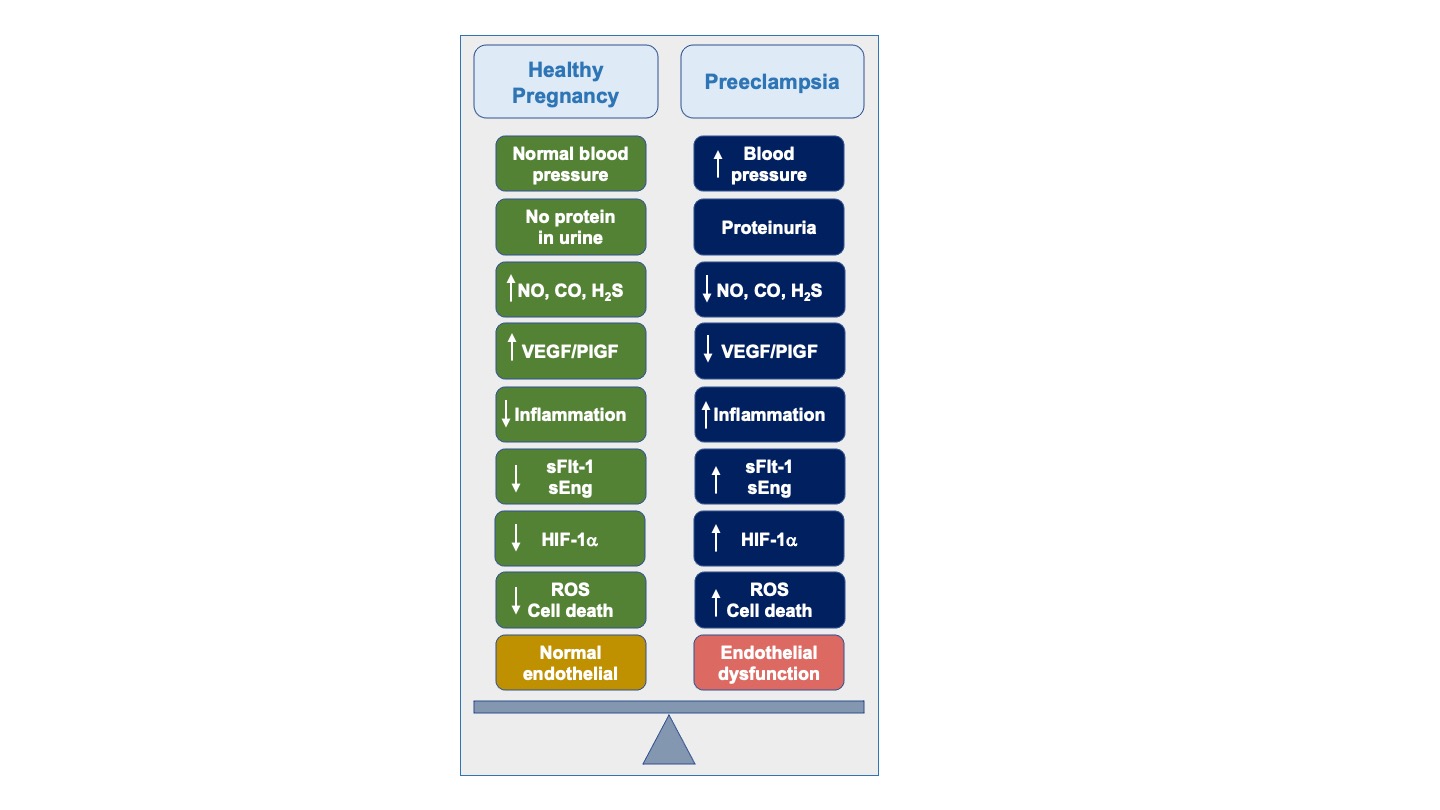

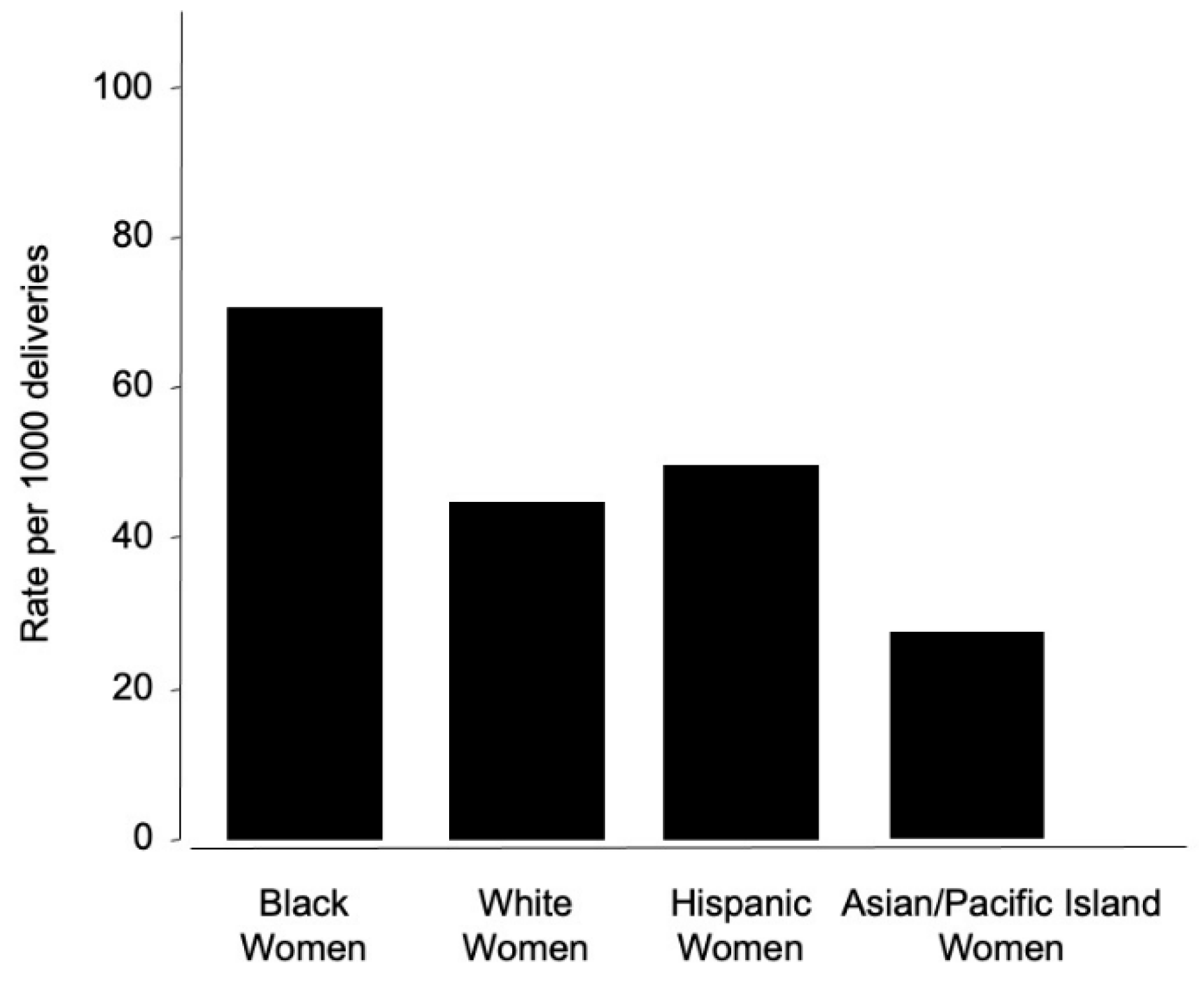

1. Introduction

2. Diagnostic Measures

2.1. Historical Perspectives

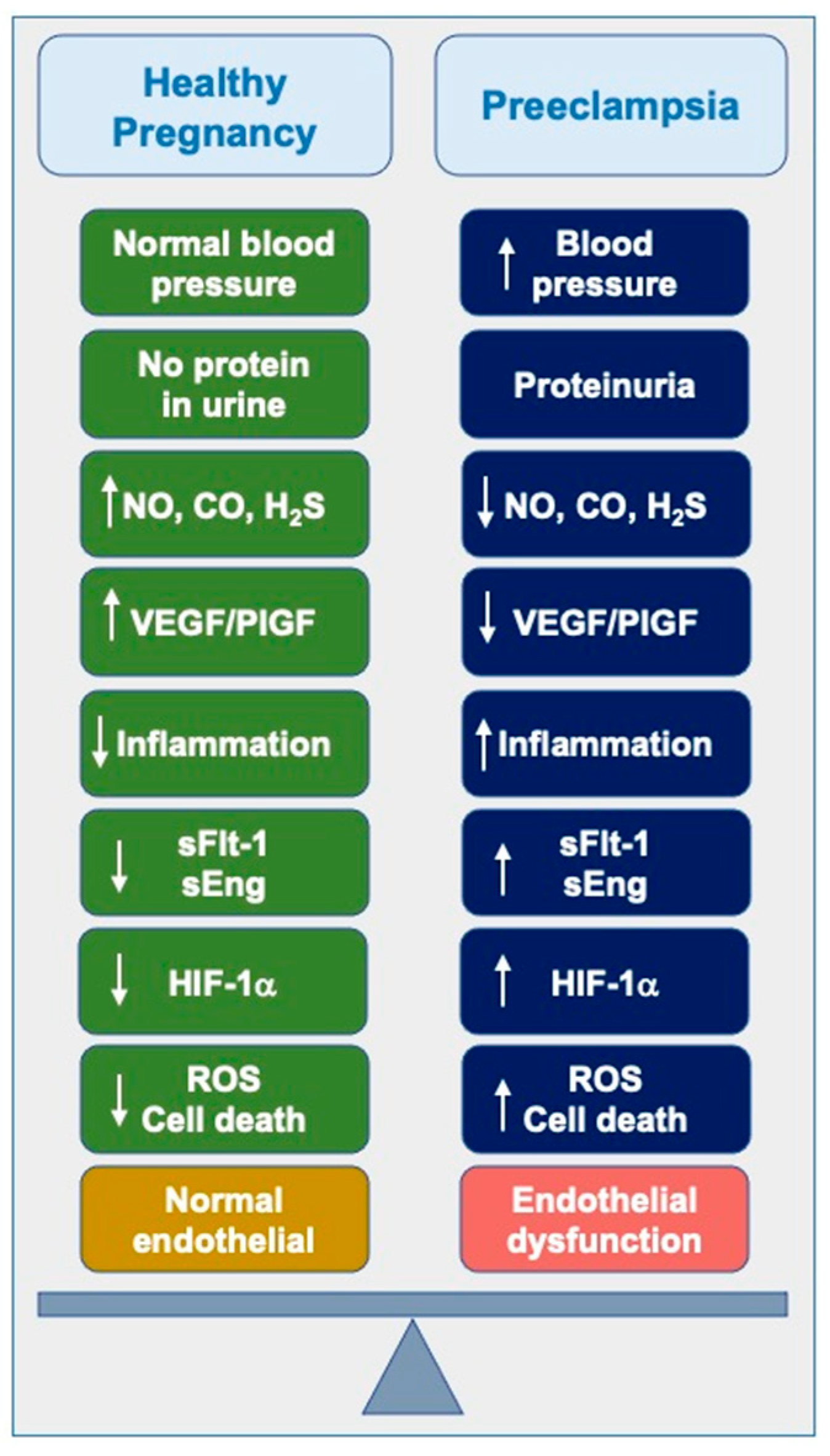

2.2. Diagnostic Measures and Current Management

2.2.1. The Role of Aspirin in Managing Preeclampsia

2.2.2. Magnesium Sulfate in Managing Preeclampsia

2.3. Inhibition of COMT and Suppression of Hypoxia-Inducible Factors (HIFs)

2.4. CoQ10 Supplementation

3. Experimental Treatments of Interest

3.1. Restoration of Angiogenic Balance

3.2. Nitric Oxide-Donors

3.3. Modulation of Carbon Monoxide Levels

3.4. H2S-Donors

3.5. Statins

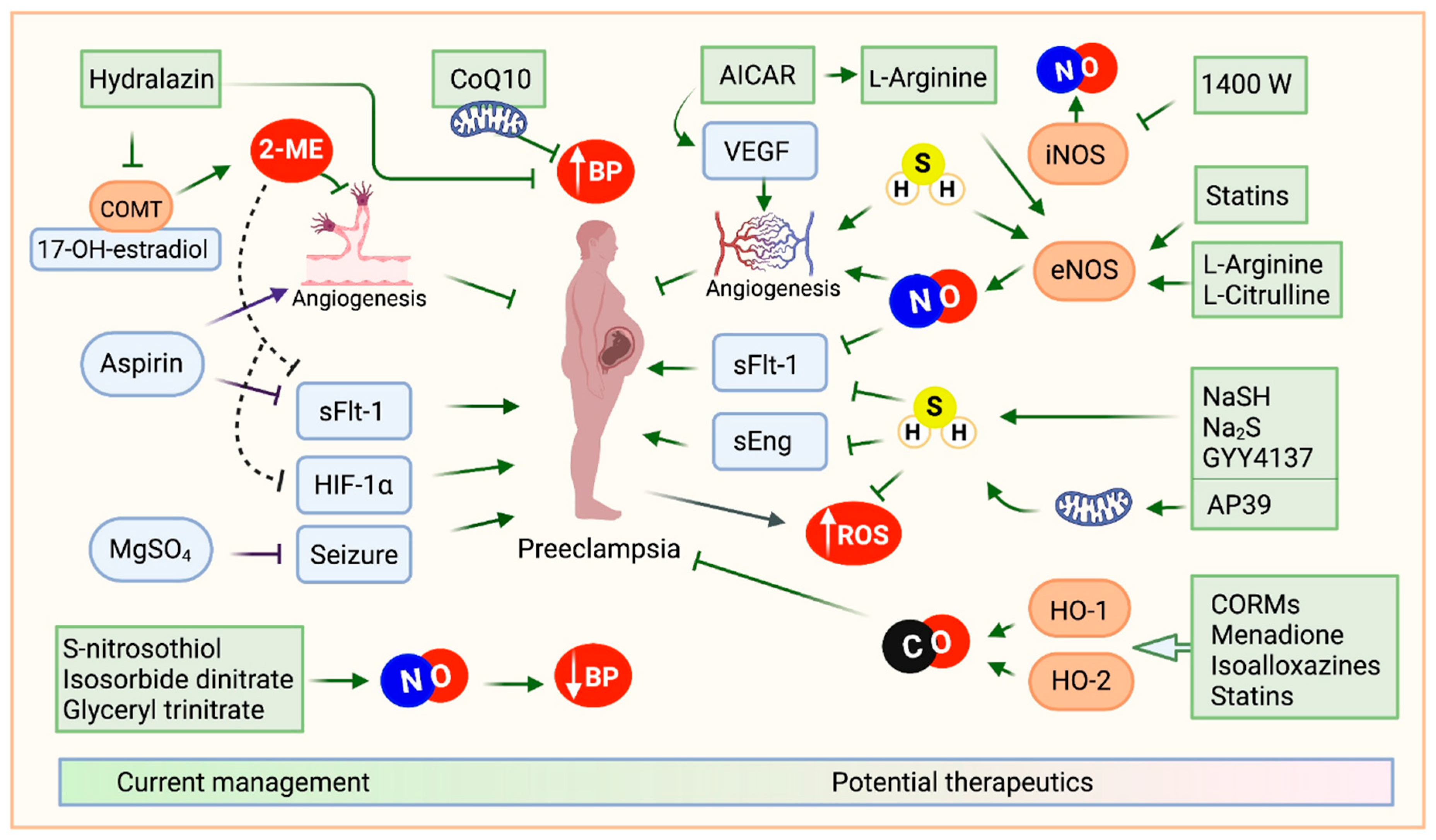

4. Preeclampsia and Racial Disparities

4.1. Maternal Mortality and PE Disparities

4.2. Genetic and Environmental Factors

4.3. Systemic Racism in Medicine

4.4. Addressing Racial Disparities

5. Concluding Remarks and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-ME: 2-methoxyestradiol ACOG: American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ADMA: asymmetric dimethylarginine AICAR: 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-3-ribonucleoside AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase APOL1: Apolipoprotein L1 CBS: Cystathionine-β-synthase COMT: Catechol-O-Methyltransferase CoQ10: Coenzyme Q10 CSE: Cystathionine γ-lyase eNOS: endothelial NOS/ Type 3 FIGO: Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics HIF-1: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 HIF-2 Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 HIF-3: Hypoxia-inducible factor 3 HMG-CoA: β-Hydroxy β-methylglutaryl-CoA HRE: Hypoxia responsive elements iNOS: inducible NOS/ Type 2, IUGR: Intrauterine growth Na2S: Sodium sulfide NaSH: Sodium hydrosulfide NEC: Necrotizing enterocolitis nNOS: neuronal NOS/ Type 1, NO: Nitric oxide PIGF: Placental growth factor ROS: Reactive oxygen species sEng: Soluble endoglobin sFlt-1: Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Dymara-Konopka, W. and M. Laskowska, The Role of Nitric Oxide, ADMA, and Homocysteine in The Etiopathogenesis of Preeclampsia-Review. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(11).

- Shih, T., et al., The Rising Burden of Preeclampsia in the United States Impacts Both Maternal and Child Health. Am J Perinatol, 2016. 33(4): p. 329-38.

- Duhig, K.E. and A.H. Shennan, Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia. F1000Prime Rep, 2015. 7: p. 24.

- Peraçoli, J.C., et al., Pre-eclampsia/Eclampsia. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet, 2019. 41(5): p. 318-332.

- Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2020. 135: p. e237-e260.

- Rana, S., et al., Preeclampsia. Circulation Research, 2019. 124(7): p. 1094-1112.

- LaMarca, B., et al., Placental Ischemia and Resultant Phenotype in Animal Models of Preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2016. 18(5): p. 38.

- El-Sayed, A.A.F., Preeclampsia: A review of the pathogenesis and possible management strategies based on its pathophysiological derangements. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 56(5): p. 593-598.

- Phipps, E.A., et al., Pre-eclampsia: pathogenesis, novel diagnostics and therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol, 2019. 15(5): p. 275-289.

- Covarrubias, A.E., et al., AP39, a Modulator of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, Reduces Antiangiogenic Response and Oxidative Stress in Hypoxia-Exposed Trophoblasts: Relevance for Preeclampsia Pathogenesis. Am J Pathol, 2019. 189(1): p. 104-114.

- Wang, K., et al., Dysregulation of hydrogen sulfide producing enzyme cystathionine γ-lyase contributes to maternal hypertension and placental abnormalities in preeclampsia. Circulation, 2013. 127(25): p. 2514-22.

- Alpoim, P.N., et al., Oxidative stress markers and thrombomodulin plasma levels in women with early and late severe preeclampsia. Clinica Chimica Acta, 2018. 483: p. 234-238.

- Tjoa, M.L., et al., Markers for presymptomatic prediction of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Hypertension in Pregnancy, 2004. 23(2): p. 171-189.

- Kanasaki, K. and R. Kalluri, The biology of preeclampsia. Kidney Int, 2009. 76(8): p. 831-7.

- Teran, E., et al., Mitochondria and Coenzyme Q10 in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Front Physiol, 2018. 9: p. 1561.

- Poon, L.C., et al., The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on pre-eclampsia: A pragmatic guide for first-trimester screening and prevention. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 2019. 145(S1): p. 1-33.

- Tanner, M.S., et al., The evolution of the diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2022. 226(2s): p. S835-s843.

- Davey, D.A. and I. MacGillivray, The classification and definition of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1988. 158(4): p. 892-8.

- Brown, M., et al., The detection, investigation and management of hypertension in pregnancy: full consensus statement. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2000. 40(2): p. 139-155.

- ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2002. 77(1): p. 67-75.

- Hypertension in Pregnancy: Executive Summary. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2013. 122(5).

- Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstetrics and gynecology (New York. 1953), 2020. 135(6): p. e237-e260.

- Karrar, S.A. and P.L. Hong, Preeclampsia, in StatPearls. 2022, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL).

- Maynard, S.E., et al., Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2003. 111(5): p. 649-658.

- Karumanchi, S.A. and F.H. Epstein, Placental ischemia and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1: cause or consequence of preeclampsia? Kidney Int, 2007. 71(10): p. 959-61.

- Lu, F., et al., The effect of over-expression of sFlt-1 on blood pressure and the occurrence of other manifestations of preeclampsia in unrestrained conscious pregnant mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2007. 196(4): p. 396.e1-7; discussion 396.e7.

- Cim, N., et al., An analysis on the roles of angiogenesis-related factors including serum vitamin D, soluble endoglin (sEng), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the diagnosis and severity of late-onset preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2017. 30(13): p. 1602-1607.

- Maynard, S.E. and S.A. Karumanchi, Angiogenic factors and preeclampsia. Semin Nephrol, 2011. 31(1): p. 33-46.

- Haggerty, C.L., et al., Second trimester anti-angiogenic proteins and preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens, 2012. 2(2): p. 158-163.

- Vatten, L.J., et al., Changes in circulating level of angiogenic factors from the first to second trimester as predictors of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2007. 196(3): p. 239.e1-6.

- Levine, R.J., et al., Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med, 2004. 350(7): p. 672-83.

- Verlohren, S., et al., New Gestational Phase–Specific Cutoff Values for the Use of the Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1/Placental Growth Factor Ratio as a Diagnostic Test for Preeclampsia. Hypertension, 2014. 63(2): p. 346-352.

- Stepan, H., et al., Implementation of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio for prediction and diagnosis of pre-eclampsia in singleton pregnancy: implications for clinical practice. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2015. 45(3): p. 241-246.

- Vatish, M., et al., sFlt-1/PlGF ratio test for pre-eclampsia: an economic assessment for the UK. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2016. 48(6): p. 765-771.

- Rana, S., et al., Angiogenic factors and the risk of adverse outcomes in women with suspected preeclampsia. Circulation, 2012. 125(7): p. 911-9.

- Sibai, B., G. Dekker, and M. Kupferminc, Pre-eclampsia. Lancet, 2005. 365(9461): p. 785-99.

- Fox, R., et al., Preeclampsia: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Management, and the Cardiovascular Impact on the Offspring. J Clin Med, 2019. 8(10).

- Chappell, L.C., et al., Planned early delivery or expectant management for late preterm pre-eclampsia (PHOENIX): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2019. 394(10204): p. 1181-1190.

- Van Doorn, R., et al., Dose of aspirin to prevent preterm preeclampsia in women with moderate or high-risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2021. 16(3): p. e0247782.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 743: Low-Dose Aspirin Use During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol, 2018. 132(1): p. e44-e52.

- Hybiak, J., et al., Aspirin and its pleiotropic application. Eur J Pharmacol, 2020. 866: p. 172762.

- Richards, E.M.F., et al., Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of superimposed preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2023. 228(4): p. 395-408.

- Euser, A.G. and M.J. Cipolla, Magnesium Sulfate for the Treatment of Eclampsia. Stroke, 2009. 40(4): p. 1169-1175.

- Smith, J.M., et al., An integrative review of the side effects related to the use of magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2013. 13: p. 34.

- Doyle, L.W., et al., Magnesium sulphate for women at risk of preterm birth for neuroprotection of the fetus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2009(1).

- Conde-Agudelo, A. and R. Romero, Antenatal magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy in preterm infants less than 34 weeks’ gestation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2009. 200(6): p. 595-609.

- Costantine, M.M. and S.J. Weiner, Effects of antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate on neuroprotection and mortality in preterm infants: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol, 2009. 114(2 Pt 1): p. 354-364.

- Padda, J., et al., Efficacy of Magnesium Sulfate on Maternal Mortality in Eclampsia. Cureus, 2021. 13(8): p. e17322.

- Kaplan, W., et al., Osteopenic effects of MgSO4 in multiple pregnancies. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 2006. 19(10): p. 1225-30.

- Majmundar, A.J., W.J. Wong, and M.C. Simon, Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell, 2010. 40(2): p. 294-309.

- Prabhakar, N.R. and G.L. Semenza, Adaptive and maladaptive cardiorespiratory responses to continuous and intermittent hypoxia mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. Physiological reviews, 2012. 92(3): p. 967-1003.

- Kietzmann, T., Liver Zonation in Health and Disease: Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription Factors as Concert Masters. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(9).

- Duan, C., Hypoxia-inducible factor 3 biology: complexities and emerging themes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2016. 310(4): p. C260-9.

- Rajakumar, A., et al., Evidence for the functional activity of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors overexpressed in preeclamptic placentae. Placenta, 2004. 25(10): p. 763-769.

- Akhilesh, M., et al., Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α as a predictive marker in pre-eclampsia. Biomed Rep, 2013. 1(2): p. 257-258.

- Kanasaki, K., et al., Deficiency in catechol-O-methyltransferase and 2-methoxyoestradiol is associated with pre-eclampsia. Nature, 2008. 453(7198): p. 1117-21.

- Parchem, J.G., et al., Loss of placental growth factor ameliorates maternal hypertension and preeclampsia in mice. J Clin Invest, 2018. 128(11): p. 5008-5017.

- Ellershaw, D.C. and A.M. Gurney, Mechanisms of hydralazine induced vasodilation in rabbit aorta and pulmonary artery. British journal of pharmacology, 2001. 134(3): p. 621-631.

- Magee, L.A., et al., Hydralazine for treatment of severe hypertension in pregnancy: meta-analysis. Bmj, 2003. 327(7421): p. 955-60.

- Symoens, J., Ketanserin: a novel cardiovascular drug. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis, 1990. 1(2): p. 219-24.

- Teran, E., et al., Coenzyme Q10 supplementation during pregnancy reduces the risk of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2009. 105(1): p. 43-5.

- Yonekura Collier, A.R., et al., Placental sFLT1 is associated with complement activation and syncytiotrophoblast damage in preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy, 2019. 38(3): p. 193-199.

- Cindrova-Davies, T., The therapeutic potential of antioxidants, ER chaperones, NO and H2S donors, and statins for treatment of preeclampsia. Front Pharmacol, 2014. 5: p. 119.

- Myatt, L., et al., Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in placental villous tissue from normal, pre-eclamptic and intrauterine growth restricted pregnancies. Hum Reprod, 1997. 12(1): p. 167-72.

- Dillon, K.M., et al., The evolving landscape for cellular nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide delivery systems: A new era of customized medications. Biochemical Pharmacology, 2020. 176: p. 113931.

- Sutton, E.F., M. Gemmel, and R.W. Powers, Nitric oxide signaling in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Nitric Oxide, 2020. 95: p. 55-62.

- Li, F., et al., eNOS deficiency acts through endothelin to aggravate sFlt-1-induced pre-eclampsia-like phenotype. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2012. 23(4): p. 652-60.

- Du, L., et al., eNOS/iNOS and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in the placentas of patients with preeclampsia. Journal of Human Hypertension, 2017. 31(1): p. 49-55.

- Amaral, L.M., et al., Antihypertensive effects of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibition in experimental pre-eclampsia. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 2013. 17(10): p. 1300-1307.

- Johal, T., et al., The nitric oxide pathway and possible therapeutic options in pre-eclampsia. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2014. 78(2): p. 244-57.

- Kulandavelu, S., et al., S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase Deficiency Causes Aberrant Placental S-Nitrosylation and Preeclampsia. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2022. 11(5): p. e024008.

- Schwedhelm, E., et al., Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of oral L-citrulline and L-arginine: impact on nitric oxide metabolism. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 2008. 65(1): p. 51-59.

- Weckman, A.M., et al., Perspective: L-arginine and L-citrulline Supplementation in Pregnancy: A Potential Strategy to Improve Birth Outcomes in Low-Resource Settings. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 2019. 10(5): p. 765-777.

- Böger, R.H., et al., Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) as a prospective marker of cardiovascular disease and mortality—An update on patient populations with a wide range of cardiovascular risk. Pharmacological Research, 2009. 60(6): p. 481-487.

- Banek, C.T., et al., AICAR administration ameliorates hypertension and angiogenic imbalance in a model of preeclampsia in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2013. 304(8): p. H1159-65.

- Tsai, W.L., C.N. Hsu, and Y.L. Tain, Whether AICAR in Pregnancy or Lactation Prevents Hypertension Programmed by High Saturated Fat Diet: A Pilot Study. Nutrients, 2020. 12(2).

- Motterlini, R. and L.E. Otterbein, The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2010. 9(9): p. 728-43.

- Tenhunen, R., H.S. Marver, and R. Schmid, Microsomal heme oxygenase. Characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem, 1969. 244(23): p. 6388-94.

- Foresti, R. and R. Motterlini, The heme oxygenase pathway and its interaction with nitric oxide in the control of cellular homeostasis. Free Radic Res, 1999. 31(6): p. 459-75.

- Otterbein, L.E. and A.M. Choi, Heme oxygenase: colors of defense against cellular stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2000. 279(6): p. L1029-37.

- Applegate, L.A., P. Luscher, and R.M. Tyrrell, Induction of heme oxygenase: a general response to oxidant stress in cultured mammalian cells. Cancer Res, 1991. 51(3): p. 974-8.

- Maines, M.D., The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 1997. 37: p. 517-54.

- Mann, B.E. and R. Motterlini, CO and NO in medicine. Chem Commun (Camb), 2007(41): p. 4197-208.

- Wu, L. and R. Wang, Carbon monoxide: endogenous production, physiological functions, and pharmacological applications. Pharmacol Rev, 2005. 57(4): p. 585-630.

- Szabo, C., Gasotransmitters in cancer: from pathophysiology to experimental therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2016. 15(3): p. 185-203.

- Dickson, M.A., et al., Carbon monoxide increases utero-placental angiogenesis without impacting pregnancy specific adaptations in mice. Reprod Biol Endocrinol, 2020. 18(1): p. 49.

- Vukomanovic, D., et al., Riboflavin and pyrroloquinoline quinone generate carbon monoxide in the presence of tissue microsomes or recombinant human cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase: implications for possible roles in gasotransmission. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 2020. 98(5): p. 336-342.

- Otterbein, L.E., et al., Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med, 2000. 6(4): p. 422-8.

- Venditti, C.C. and G.N. Smith, Involvement of the heme oxygenase system in the development of preeclampsia and as a possible therapeutic target. Womens Health (Lond), 2014. 10(6): p. 623-43.

- Wikström, A.K., O. Stephansson, and S. Cnattingius, Tobacco use during pregnancy and preeclampsia risk: effects of cigarette smoking and snuff. Hypertension, 2010. 55(5): p. 1254-9.

- Levine, R.J., et al., Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355(10): p. 992-1005.

- Ahmed, A., H. Rezai, and S. Broadway-Stringer, Evidence-Based Revised View of the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia, in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2016, Springer US: Boston, MA. p. 1-20.

- Bainbridge, S.A., E.H. Sidle, and G.N. Smith, Direct placental effects of cigarette smoke protect women from pre-eclampsia: the specific roles of carbon monoxide and antioxidant systems in the placenta. Med Hypotheses, 2005. 64(1): p. 17-27.

- Ahmed, A., et al., Induction of placental heme oxygenase-1 is protective against TNFalpha-induced cytotoxicity and promotes vessel relaxation. Molecular Medicine, 2000. 6(5): p. 391-409.

- Barber, A., et al., Heme oxygenase expression in human placenta and placental bed: reduced expression of placenta endothelial HO-2 in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Faseb j, 2001. 15(7): p. 1158-68.

- Zenclussen, A.C., et al., Heme oxygenases in pregnancy II: HO-2 is downregulated in human pathologic pregnancies. Am J Reprod Immunol, 2003. 50(1): p. 66-76.

- Cudmore, M., et al., Negative Regulation of Soluble Flt-1 and Soluble Endoglin Release by Heme Oxygenase-1. Circulation, 2007. 115(13): p. 1789-1797.

- Tong, S., et al., Heme Oxygenase-1 Is Not Decreased in Preeclamptic Placenta and Does Not Negatively Regulate Placental Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1 or Soluble Endoglin Secretion. Hypertension, 2015. 66(5): p. 1073-81.

- George, E.M., et al., Carbon Monoxide Releasing Molecules Blunt Placental Ischemia-Induced Hypertension. Am J Hypertens, 2017. 30(9): p. 931-937.

- Bainbridge, S.A., et al., Carbon monoxide decreases perfusion pressure in isolated human placenta. Placenta, 2002. 23(8-9): p. 563-9.

- Venditti, C.C., et al., Chronic carbon monoxide inhalation during pregnancy augments uterine artery blood flow and uteroplacental vascular growth in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2013. 305(8): p. R939-48.

- Venditti, C.C., et al., Carbon monoxide prevents hypertension and proteinuria in an adenovirus sFlt-1 preeclampsia-like mouse model. PLoS One, 2014. 9(9): p. e106502.

- Vukomanovic, D., et al., In vitro Activation of heme oxygenase-2 by menadione and its analogs. Med Gas Res, 2014. 4(1): p. 4.

- Vukomanovic, D., et al., Drug-enhanced carbon monoxide production from heme by cytochrome P450 reductase. Med Gas Res, 2017. 7(1): p. 37-44.

- Odozor, C.U., et al., Endogenous carbon monoxide production by menadione. Placenta, 2018. 71: p. 6-12.

- Harris, C.B., et al., Dietary pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) alters indicators of inflammation and mitochondrial-related metabolism in human subjects. J Nutr Biochem, 2013. 24(12): p. 2076-84.

- Cheng, J. and J. Hu, Recent Advances on Carbon Monoxide Releasing Molecules for Antibacterial Applications. ChemMedChem, 2021. 16(24): p. 3628-3634.

- Sela, S., et al., Local retention versus systemic release of soluble VEGF receptor-1 are mediated by heparin-binding and regulated by heparanase. Circ Res, 2011. 108(9): p. 1063-70.

- Motterlini, R., B.E. Mann, and R. Foresti, Therapeutic applications of carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. Expert Opin Investig Drugs, 2005. 14(11): p. 1305-18.

- McRae, K.E., et al., CORM-A1 treatment leads to increased carbon monoxide in pregnant mice. Pregnancy Hypertens, 2018. 14: p. 97-104.

- Kashfi, K., The dichotomous role of H(2)S in cancer cell biology? Déjà vu all over again. Biochemical pharmacology, 2018. 149: p. 205-223.

- Kashfi, K. and K.R. Olson, Biology and therapeutic potential of hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing chimeras. Biochemical pharmacology, 2013. 85(5): p. 689-703.

- Patel, P., et al., The endogenous production of hydrogen sulphide in intrauterine tissues. REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY AND ENDOCRINOLOGY, 2009. 7.

- Holwerda, K.M., et al., Hydrogen sulfide producing enzymes in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Placenta, 2012. 33(6): p. 518-521.

- Powell, C.R., K.M. Dillon, and J.B. Matson, A review of hydrogen sulfide (H(2)S) donors: Chemistry and potential therapeutic applications. Biochem Pharmacol, 2018. 149: p. 110-123.

- Holwerda, K.M., et al., Hydrogen sulfide attenuates sFlt1-induced hypertension and renal damage by upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2014. 25(4): p. 717-25.

- Whiteman, M., et al., Hydrogen sulphide: a novel inhibitor of hypochlorous acid-mediated oxidative damage in the brain? Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2005. 326(4): p. 794-8.

- Jha, S., et al., Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of antioxidant and antiapoptotic signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2008. 295(2): p. H801-6.

- Li, H., et al., Hydrogen sulfide and its donors: Novel antitumor and antimetastatic therapies for triple-negative breast cancer. Redox Biol, 2020. 34: p. 101564.

- Zheng, Y., et al., Hydrogen sulfide prodrugs—a review. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 2015. 5(5): p. 367-377.

- Drucker, N.A., et al., Hydrogen Sulfide Donor GYY4137 Acts Through Endothelial Nitric Oxide to Protect Intestine in Murine Models of Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Intestinal Ischemia. J Surg Res, 2019. 234: p. 294-302.

- Marín, R., et al., Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2020. 1866(12): p. 165961.

- Ahmad, A., et al., AP39, A Mitochondrially Targeted Hydrogen Sulfide Donor, Exerts Protective Effects in Renal Epithelial Cells Subjected to Oxidative Stress in Vitro and in Acute Renal Injury in Vivo. Shock, 2016. 45(1): p. 88-97.

- Szczesny, B., et al., AP39, a novel mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide donor, stimulates cellular bioenergetics, exerts cytoprotective effects and protects against the loss of mitochondrial DNA integrity in oxidatively stressed endothelial cells in vitro. Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry, 2014. 41: p. 120-130.

- Istvan, E.S. and J. Deisenhofer, Structural Mechanism for Statin Inhibition of HMG-CoA Reductase. Science, 2001. 292(5519): p. 1160-1164.

- Patel, K.K. and K. Kashfi, Lipoproteins and cancer: The role of HDL-C, LDL-C, and cholesterol-lowering drugs. Biochem Pharmacol, 2021: p. 114654.

- Pinal-Fernandez, I., M. Casal-Dominguez, and A.L. Mammen, Statins: pros and cons. Med Clin (Barc), 2018. 150(10): p. 398-402.

- Kato, S., et al., Lipophilic but not hydrophilic statins selectively induce cell death in gynaecological cancers expressing high levels of HMGCoA reductase. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 2010. 14(5): p. 1180-1193.

- Liao, J.K. and U. Laufs, Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 2005. 45: p. 89-118.

- Oesterle, A., U. Laufs, and J.K. Liao, Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circulation research, 2017. 120(1): p. 229-243.

- Gauthier, T.W., et al., Nitric oxide protects against leukocyte-endothelium interactions in the early stages of hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 1995. 15(10): p. 1652-9.

- Dimmeler, S., et al., Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature, 1999. 399(6736): p. 601-5.

- Ahmadi, Y., A. Ghorbanihaghjo, and H. Argani, The balance between induction and inhibition of mevalonate pathway regulates cancer suppression by statins: A review of molecular mechanisms. Chem Biol Interact, 2017. 273: p. 273-285.

- Ahmed, A., et al., A new mouse model to explore therapies for preeclampsia. PLoS One, 2010. 5(10): p. e13663.

- Costantine, M.M., et al., Using pravastatin to improve the vascular reactivity in a mouse model of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1-induced preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol, 2010. 116(1): p. 114-120.

- Lefkou, E., et al., Pravastatin improves pregnancy outcomes in obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome refractory to antithrombotic therapy. J Clin Invest, 2016. 126(8): p. 2933-40.

- Kumasawa, K., et al., Pravastatin for preeclampsia: From animal to human. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 2020. 46(8): p. 1255-1262.

- Brownfoot, F.C., et al., Effects of simvastatin, rosuvastatin and pravastatin on soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sENG) secretion from human umbilical vein endothelial cells, primary trophoblast cells and placenta. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2016. 16: p. 117.

- Law, L.L.o.H.U.S.o. 2018; Available from: https://library.law.howard.edu/socialjustice/disparity.

- Liese, K.L., et al., Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 2019. 6(4): p. 790-798.

- Shahul, S., et al., Racial Disparities in Comorbidities, Complications, and Maternal and Fetal Outcomes in Women With Preeclampsia/eclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy, 2015. 34(4): p. 506-515.

- Tanaka, M., et al., Racial disparity in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in New York State: a 10-year longitudinal population-based study. Am J Public Health, 2007. 97(1): p. 163-70.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., et al., 434: Racial disparities in preeclampsia outcomes at delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2019. 220(1): p. S294.

- Ghosh, G., et al., Racial/ethnic differences in pregnancy-related hypertensive disease in nulliparous women. Ethn Dis, 2014. 24(3): p. 283-9.

- Lisonkova, S. and K.S. Joseph, Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2013. 209(6): p. 544.e1-544.e12.

- Mogos, M.F., et al., Inpatient Maternal Mortality in the United States, 2002-2014. Nursing research, 2020. 69(1): p. 42-50.

- Johnson, J.D. and J.M. Louis, Does race or ethnicity play a role in the origin, pathophysiology, and outcomes of preeclampsia? An expert review of the literature. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2020.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., et al., Preeclampsia outcomes at delivery and race. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 2020. 33(21): p. 3619-3626.

- Wolf, M., et al., Differential Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy among Hispanic Women. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2004. 15(5): p. 1330-1338.

- Zamora-Kapoor, A., et al., Pre-eclampsia in American Indians/Alaska Natives and Whites: The Significance of Body Mass Index. Maternal and child health journal, 2016. 20(11): p. 2233-2238.

- Miller, A.K., et al., Association of preeclampsia with infant APOL1 genotype in African Americans. BMC Med Genet, 2020. 21(1): p. 110.

- Reidy, K.J., et al., Fetal-Not Maternal-APOL1 Genotype Associated with Risk for Preeclampsia in Those with African Ancestry. Am J Hum Genet, 2018. 103(3): p. 367-376.

- Osungbade, K.O. and O.K. Ige, Public health perspectives of preeclampsia in developing countries: implication for health system strengthening. J Pregnancy, 2011. 2011: p. 481095.

- Malik, A., B. Jee, and S.K. Gupta, Preeclampsia: Disease biology and burden, its management strategies with reference to India. Pregnancy Hypertens, 2019. 15: p. 23-31.

- Ayala-Ramírez, P., et al., Risk factors and fetal outcomes for preeclampsia in a Colombian cohort. Heliyon, 2020. 6(9): p. e05079.

- Kim, J.H. and E.C. Park, Impact of socioeconomic status and subjective social class on overall and health-related quality of life. BMC Public Health, 2015. 15: p. 783.

- Sones, J.L. and R.L. Davisson, Preeclampsia, of mice and women. Physiol Genomics, 2016. 48(8): p. 565-72.

- Ghulmiyyah, L. and B. Sibai, Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Semin Perinatol, 2012. 36(1): p. 56-9.

- Majumder, S., et al., Placental Gene Therapy for Fetal Growth Restriction and Preeclampsia: Preclinical Studies and Prospects for Clinical Application. J Clin Med, 2024. 13(18).

- Holdt Somer, S.J., R.G. Sinkey, and A.S. Bryant, Epidemiology of racial/ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol, 2017. 41(5): p. 258-265.

- Hardeman, R.R., E.M. Medina, and K.B. Kozhimannil, Structural Racism and Supporting Black Lives - The Role of Health Professionals. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(22): p. 2113-2115.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).