Introduction

Postpartum hypertension (PPHT) is elevated blood pressure that persists or develops directly after delivery and affects 10% of all pregnancies[

1]. In general, PPHT is triggered by a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP) which includes preexisting and gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets)[

2]. Although HDP are the most common trigger of PPHT, PPTH also includes transient elevated blood pressure (BP) that occurs directly after birth due to pain, volume overload, medications, or cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, among others causes[

3]. HDP accounts for 18% of maternal deaths worldwide, and with its direct link to PPHT it should be considered with similar gravity[

3,

4].

However, medical guidelines focus mainly on antenatal management of women with HDP or women specifically with preeclampsia during pregnancy. This, despite the fact that patients can develop high BP up to 4 weeks into the postpartum period[

1,

3]. In addition, there is little data available about the evaluation, management, and complications of women with PPHT even though the condition of PPHT is one of the most common causes of readmission after delivery and discharge[

5]. Important to note is, that data regarding intermediate and long-term outcomes only exists in the context of preeclampsia, which represents only a part of spectrum of PPHT. Although the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) gives guidance leaning towards tight postpartum controls there is no consensus on what is safe, feasible and excepted in this and of a life with a PPHT and a newborn baby[

6].

In this context, we established the Basel Postpartum Hypertension Cohort (Basel-PPHT), a register enrolling all patients with PPHT and collecting follow up data for up to 5 years. The aim of this manuscript is to describe the design of the registry, baseline characteristics and inclusion rate after the first 2 years. Additionally, we report about the choice of the patients regarding their post discharge management plan (remote vs in-hospital visits) and the patients’ acceptance of a home-based telemonitoring management strategy (HBTMS).

In the future, this cohort aims to assess long-term cardiovascular and renal outcomes in women with PPHT, as evidence indicates that these women have an increased long-term cardiovascular risk. Additionally, we will evaluate short term outcomes of remote disease management options in this disease setting[

7,

8].

Methods

The study protocol complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the local ethics committee, Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (Ethics Commission Northwest and Central Switzerland), (EKNZ 2020-00736), and registered (

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04690660, NCT04690660). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study Procedures, Design, Definitions

Basel-PPHT is a single center prospective observational cohort study; with currently three nested substudies based at the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland.

This study takes place in close cooperation of the Hypertension Clinic of the Medical Outpatient Department and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University Hospital Basel. Pregnant women were screened and recruited by the treating physicians in both departments and the study team. Patients were treated and followed-up according to the local standards of the Hypertension Clinic of the Medical Outpatient Department.

After inclusion, baseline characteristics, outlined in

Supplementary Table S1 were collected in the form of a case reporting form (CRF). CRF data was collected from the hospital’s electronic clinical documentation system, from a structured interview with self-reported information at enrollment and entered into an electronic database.

Key time-points of the study were baseline which was defined as inclusion into the study with informed consent, landmark visit 1 (approximately 3 months after delivery), landmark visit 2 (approximately 6 months after delivery) landmark 3 (approximately 12 months after delivery).

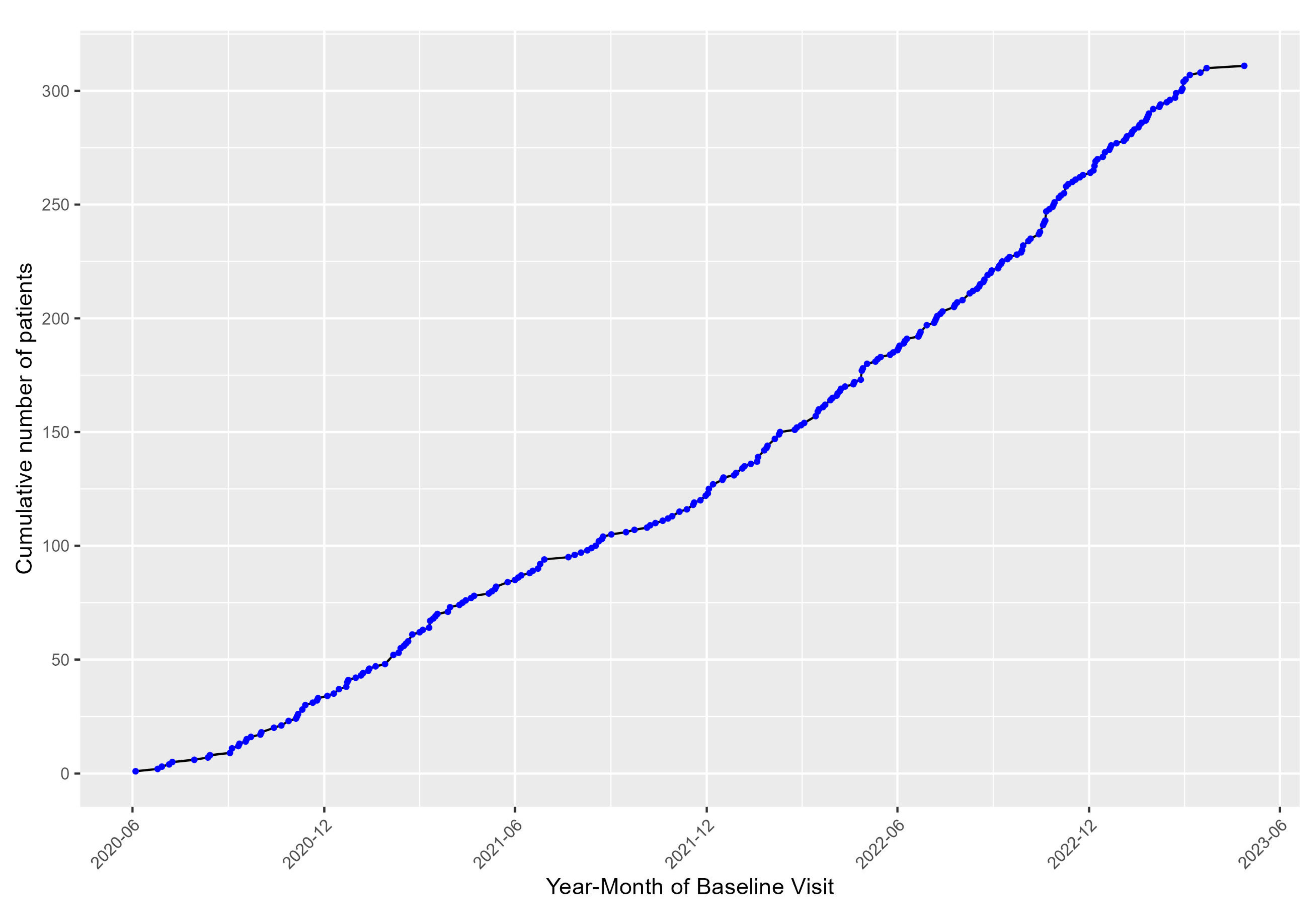

Enrollment started in June 2020 and at the time of this interim analysis, in March 2023, the cohort consisted of 311 patients out of a planned 480 recruitments.

Eligible were are all women with HDP and PPHT (defined as blood pressure measurements of systolic ≥140 and/or diastolic ≥ 90mmHg or the indication of antihypertensive therapy up to six weeks after delivery) or women with preexisting hypertension or women on antihypertensive medication after delivery with an age ≥ 18 years[

9]. As mentioned above, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) included preexisting and gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets). These diseases sometimes overlap and were diagnosed by the treating obstetrician. To determine PPHT in women without antihypertensive medication in- hospital routine blood pressure measurements (BPM) were taken multiple times during vital signs monitoring during nurse rounds. A minimum of at least two blood pressure measurements using a Welch Allyn blood pressure device with an upper arm cuff, (BPM) >139mmHg systolic and/or >89mmHg diastolic were needed to diagnose PPHT . Exclusion criteria consists of < 18 years of age, and lack of consent to participate in the study, language barriers or lack of general understanding regarding the study and consent.

The definition of high risk for preeclampsia was not based on any single criteria and was either based on the course and outcome of a previous pregnancy, decided by the treating obstetrician during the pregnancy, or based on the fetal medicine calculator cut-offs

https://fetalmedicine.org/research/assess/preeclampsia/first-trimester for risk assessment of preeclampsia during pregnancy. This risk calculation tool uses Bayes theorem and combines various factors including medical history, biophysical and biochemical measurements to estimate the risk of PE in this pregnancy[

10].

Blood Pressure Monitoring: In-hospital and after Discharge

As mentioned above blood pressure was monitoring during clinic visits from the nursing staff. This standardized measurement was taken with a Welch Allyn blood pressure device programmed to take 5 automatic unattended measurements. These measurements were then automatically transmitted to the patient’s electronic chart and reviewed by the treating physician. After discharge patient’s BP was as monitored as clinically indicated, either with planned outpatient visits, an asynchronous telemonitoring system or a programmed spreadsheet. During outpatient visits an unattended automatic office blood pressure measurement was taken and at landmark visits a ambulatory 24 blood pressure measurement was taken. The various monitoring protocols are described below.

Asynchronous telemonitoring:

The telemonitoring system used at the University Hospital Basel was the HEKA SMBP mobile phone application (App) (HEKA HEALTH, San Mateo, CA, USA), a customized order entry system where the physician decides when the patients should start their home blood pressure measurement period. A BPM prescription or order entry is submitted into an online portal, consisting of a period of 7 days. During the 7 days, patients are reminded via an alert on their smartphone to measure their blood pressure in the morning and in the evening, with a 12-hour interval between the measurements. Each set of measurements is guided by the App, instructing the patient on how to measure their blood pressure correctly. In brief, all patients were advised to use a clinically validated, upper arm cuff device for BPM. Patients were instructed to rest 5 minutes before the first measurement and 1 minute between the first and the second measurement. BP values are entered directly into the App after each measurement. After the measurement period, the physician receives the mean value of all correctly executed BP measurements. A valid measurement period was defined by the App when the patient measured their BP twice within an interval of a minute in the morning and evening for at least three days with the seven-day period. In addition, the morning and evening sets of measurement were required to be at least six hours apart for the measurement block to be considered valid and therefore generate a mean blood pressure. The HEKA App currently is only compatible with an iOS System, therefore for those patients who had the clinical indication for blood pressure monitoring after discharge but did not have an iOS system were given a programmed excel spreadsheet instead.

Excel spreadsheet

Initially we planned to offer a remote BP measurement only to patients with an iOS smartphone to ensure correct measurement. However, due to the COVID pandemic with several lockdowns, there was an urgent need of making telemonitoring and virtual BP management more accessible[

11]. Therefore, we provided patients without an iOs smartphone the possibility to report home BP with a programmed excel spreadsheet. The excel spreadsheet (supplementary material S2) was created by the research team, and designed so the patient could document 7 days of measurements. Each day consisted of two measurements in the morning and two in the evening. The data sets were entered by the patient into the excel spreadsheet and then an average of the morning and evening values and of the values of the complete week was automatically calculated.

Ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure measurement

For ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure measurement, a Mobil-O-Graph, Mobil-O-Graph PWA or Spacelabs 90217A device was used[

12]. The 24h blood pressure devices were programmed to take BP measurements every 20 min from 08:00 to 22:00 and every 30 min from 22:00 to 8:00. Individual participant diaries were used to define awake and asleep times. Their corresponding analysis software (Spacelabs Healthcare Inc, USA and Mobil-O-Graph, IEM GmBH, Aachen, Germany) analyzed the BP measurements after the 24-hour BP measurement period. Mean systolic and diastolic 24-hour, awake and asleep BP values were calculated.

Unattended automated office blood pressure measurement

Patients were placed alone in a quiet room and instructed to sit upright in a chair with uncrossed legs and both feet on the ground. The correct cuff was selected to match the arm circumference and was positioned at the level of the heart. The nurse performed a test measurement to check if the device was working properly, then started the test sequence and left the room. During the recorded measurement itself, the device automatically took three measurements after 5, 7 and 9 minutes. We used a Welch Allyn Connex® Spot Monitor which applies the SureBP® measurement technique by Welch Allyn, which has been validated according to the American National Standards Institute/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation SP10:2006 (AAMI) and the British Hypertension Society (BHS) 1993 protocols[

13,

14]. The device was programmed to calculate the mean of these three measurements.

Routine Blood and Urine Sampling

All clinically indicated laboratory panels were collected from patients at postpartum landmark visits: 3 months, and if clinically indicated at 6 months, 12 months and yearly thereafter. These basic blood draws were immediately processed, and the results were accessible to the treating physician and guided clinical decision-making. Additional aliquots of blood were obtained only if the patient consented to the biomarker substudy and were timed to correspond to clinically indicated blood draws.

Quality of Life and Disability

The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) is a widely used, non-disease specific preference-based instrument to measure health related quality of life, and is used for this purpose in the current study. This tool was implemented in our study at baseline to obtain a profile of patient health on the day of recruitment into the study.

Home Based Telemonitoring Management Strategy and Standard In-Hospital Management

At enrollment, women included in the Basel-PPHT-Cohort with in-hospital elevated blood pressure and who had an indication for further blood pressure monitoring were informed about two possibilities of follow up. The HBTMS and standard management with in-hospital appointments after discharge.

Those who were in the HBTMS had scheduled telephone consultations with a treating physician from the Hypertension Clinic after SMPB periods. In general, the initial post discharge consultation with the telemonitoring blood pressure measurement occurred one week after discharge, the following measurement periods were determined based on clinical judgement. The number of telemedicine consultations was decided by the treating physician and was dependent on the indication for further up or down titrations of medications and blood pressure related symptoms. Once the patients were either, stable in terms of blood pressure the telemedicine visits were stopped, and all patients underwent a 24h blood pressure measurement three months after giving birth. If relevantly elevated blood pressure was detected 3 months after giving birth, then a repeat 24h blood pressure measurement was done at 6 months postpartum and after that yearly.

The standard in-hospital management consisted of outpatient visits in our Hypertension Clinic 1-2 weeks after discharge and thereafter as clinically indicated. (

Figure 1)

Cardiovascular and Renal Biomarker Profiles Substudy

An additional substudy in the Basel-PPHT-Cohort consist of biomarker blood banking for later analysis. This occurs at baseline (enrolment), three, six, and twelve months after delivery. Biobanking takes place at the University Hospital Basel and analysis are planned to be done in batches. The serum monovettes were centrifuged immediately and aliquoted into cryotubes and stored an –80°C at the general clinical research laboratory and Department of Biomedicine at the University Hospital Basel. The aim is to investigate the prognostic value of biomarkers for disease progression and cardiovascular events.

Cardiac Imaging Substudy

In cases of persistent hypertension 6 months after delivery, a transthoracic echocardiography was routinely carried out. We plan to enroll patients into two age matched control cohorts, (

Supplementary Table S2), with a sample size of 40 women per group. The first control group will consist of women with transient PPHT and normalization of blood pressure free of medication by the time of the first landmark visit (approximately 3 months postpartum). The second control group will be comprised of women who have given birth after uncomplicated pregnancy. The matched control cohorts will strengthen the statistical comparison of women with persistent hypertension.

Questionnaires/Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

We evaluate patient reported outcome measures of the HBTMS group with a questionnaire that we developed (Supplementary 3). This questionnaire was completed at the three-month follow-up during the patient’s clinical visit.

Statistical Methods

The distribution of continuous variables will be determined using skewness, kurtosis and visual inspection of the histograms. Continuous data will be reported as mean +/- standard deviation or median (interquartile range) and compared by means of analyzes of variance (ANOVA) and Mann-Whitney U tests depending on variable distribution. Categorical variables are described as counts (percent) and compared to chi-square tests.

In addition to diagnostic accuracies for investigations, receiver-operator characteristic curves are calculated, as well as sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative prediction probabilities. Kaplan Meier and logistical regression will be used where appropriate. The correlation coefficients, variability and standard deviation of the blood pressure measurements were used.

Sample Size Calculation

As this is an observational hypothesis generating cohort study, no sample size calculation was made except for the control group of the cardiac imaging substudy. Previous studies investigating baseline to 6-month changes in echocardiographic measurements of women with persistent PPHT are currently not available. Furthermore, there is a lack of data on the new echocardiographic parameters that we are planning to study such as myocardial work index. We therefore have referenced the PICk-UP (Postnatal enalapril to Improve Cardiovascular fUnction following preterm Preeclampsia) study to determine our sample size calculation[

15].

This PICk-UP study was a single center randomized control trial focused on women with preterm preeclampsia, who have an 8-fold risk of death from future CVD. Women were randomized to enalapril, to improve postnatal cardiovascular function or placebo for 6 months. Echocardiography and haemodynamic measurements were performed at baseline (< 3 days), 6 weeks and 6 months post-delivery on 60 women.

We hypothesize that 25% of our participants will have concentric remodelling after 6 months of persistent hypertension and that the control group consisting of healthy women without hypertension, less than 3% will present with concentric remodelling. Therefore, with an alpha value of significance of 0.05 and an 80% power to detect an effect size we need 40 healthy controls. We plan to recalculate our sample size calculation after the inclusion of 40 participants with persistent hypertension at 6 months.

Statistical analysis was done using statistical software R (version 4.2.1), a p-value of <0.05 is pre-specified to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Inclusion Trends

Until March 2023, we included 311 patients into the registry. Inclusion into the registry, depicted in

Figure 2, started in June 2020, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic and rapidly increased over the course of the 2021-2022.

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the cohort. The mean (±standard deviation) age was 33.8 (5.3) years and 47.9% of the cohort was primipara. Average BMI was 27(6.2) kg/m

2. Mean weight before pregnancy was 71 (±18) kg and after delivery 83(±20) kg. 84.8 % of the cohort were Caucasian, 4.6 % Asian, 6 % Black or African Origin, and 2.7% were Middle Eastern. 20% had a university level education, 17.3% a secondary university degree, and 55.3% vocational training. 64.3 % of women self-reported a healthy diet without regular intake of increased caffeine (more than 2 servings per day), processed foods, increased salt, or energy drinks. 23.3% of the cohort was determined as high risk for preeclampsia and 29% took aspirin during the current pregnancy. The most prevalent comorbidity during pregnancy was a history of hypertension in 11.9%. 10.6 % had a thyroid related disease at baseline.

In terms of medical history of previous pregnancies, 30% of the cohort had one or more miscarriage prior to their current pregnancy. 7.4% had a preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, 61% were unsure if they had a complication in their last pregnancy.

Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Co-morbidities

The most common self-reported cardiovascular risk factor was a positive family history of cardiovascular disease, in 49.5% of the women. In total, 21.2% had smoked, currently smoke or smoke occasionally, 6.1% were still active. History of exposure to pollution, city dwelling, and occupational exposure combined, was reported in 62% of the cohort. A positive family history of preeclampsia was reported in 7.5%.

Table 2 provides information about different cardiovascular risk factors at baseline.

Hypertension and Relevant Medical History of the current Pregnancy

Preeclampsia was present in 53% of the cases. Gestational hypertension occurred in 27.3% and was the second most prevalent condition, followed by isolated postpartum hypertension at 18.3%.

Table 3 depicts the relevant hypertensive and medical history of the current pregnancy.

Delivery Characteristics

Table 4 summarizes the types of deliveries of the patients in the cohort. The majority of women, 68%, delivered by cesarean section, 23% had a vaginal birth and 8.2% gave birth by vacuum extraction. The average week of gestation at delivery was 36.82±3.3. Intrauterine growth restriction was diagnosed in 21% of the newborns. Average birth weight of the newborns was 2828 (± 863.3) grams.

Baseline Medication

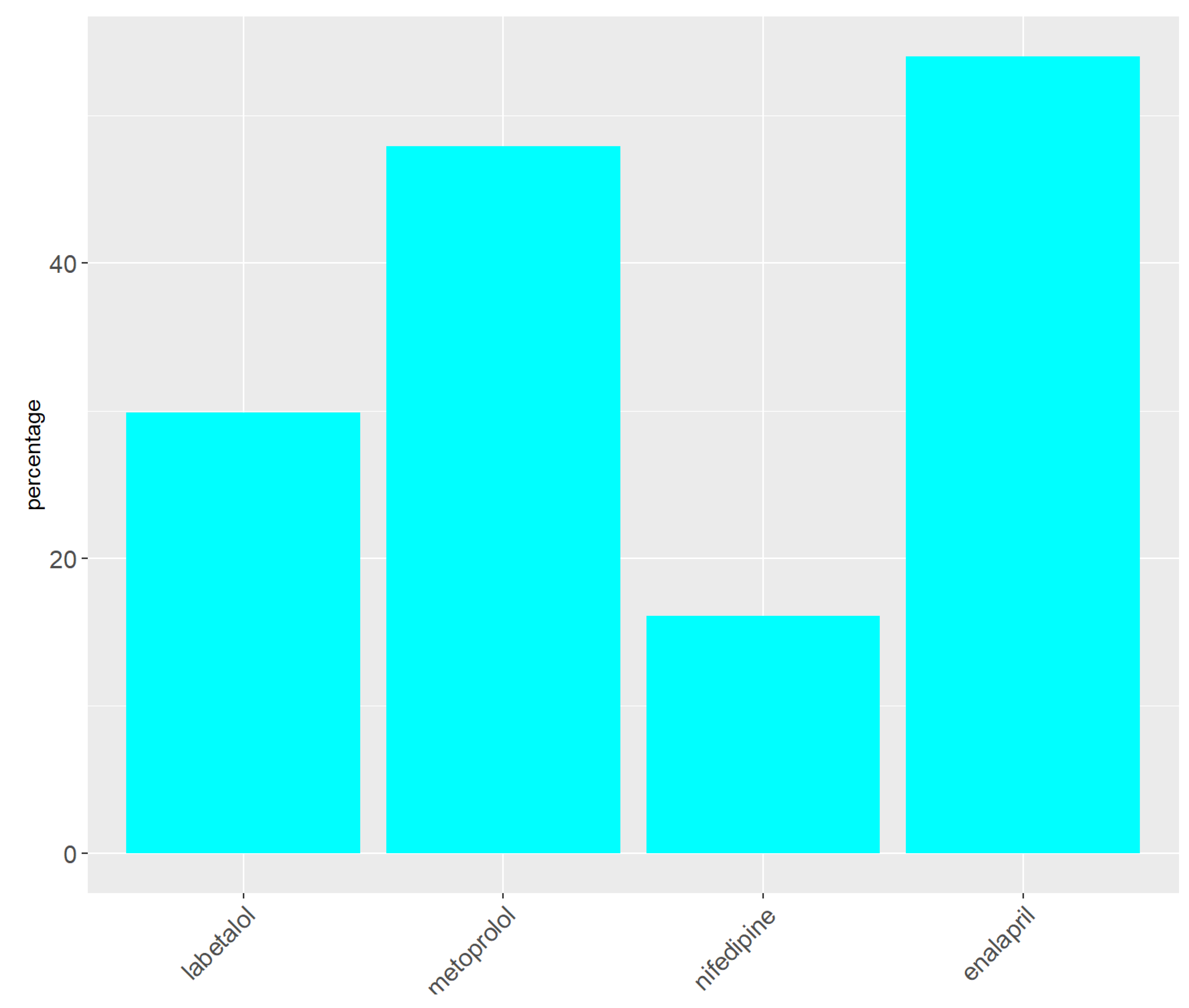

At baseline 86% (266), missing (n=3), patients were taking antihypertensive medication. The following medication distribution was documented: 30% (93) labetalol, 48% (149) metoprolol, 16.1% (50) nifedipine, and 54% (168) enalapril.

Figure 2.

Baseline Antihypertensive Medication.

Figure 2.

Baseline Antihypertensive Medication.

Blood Pressure Values

The maximum values of blood pressure and heart rate during hospital stay are depicted in Table 9. The mean maximum systolic and diastolic blood pressure was 168± 17.1 and 106 mmHg ± 18.1, respectively. The mean maximum heart rate was 115± 29 beats per minute (bpm) Table 9.

Table 5.

Postpartal Blood Pressure Characteristics.

Table 5.

Postpartal Blood Pressure Characteristics.

| max. systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) |

168 ± 17 |

| max diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) , mean (SD) |

107 ± 19 |

| max heart rate (bpm) , mean (SD) |

115 ± 29 |

Patient chosen Management Plan

In terms of post discharge management 99% of the women preferred a home-based telemonitoring management plan. 65% women had an iPhone/iPad and 67 % used the Telemonitoring App to document their blood pressure.

Table 6.

Patient favored Management Plan.

Table 6.

Patient favored Management Plan.

patient favored management plan, n (%)

missing data (n=6)

|

|

- -

home based

|

302 (99.02) |

- -

standard of care

|

3 (1) |

Type of HBTMS, n (%)

missing data (n=7)

|

|

- -

telemonitoring App

|

198 (65.13) |

| |

|

Discussion

Previous studies on this cohort of women focus mainly on preeclampsia and less on the other causes of PPHT. Our goal is to contribute to this important discussion, by looking at the short and medium-term course outcomes in these women and including all the entities that cause PPHT. Additionally, we want to better understand medium- and long-term prognostic data for the entire spectrum of PPHT in regard to prevalence, normalization of BP, persistent hypertension, blood pressure patterns and end organ damage which will be eventually realized within the framework of the nested echocardiography sub-study. The framework of this registry, allows for the better understanding of the characteristics of these women, helping us to more accurately focus and target resources on certain patients after discharge. With the nested sub-studies including the home-based management strategy we can with more certainty see how different care models are accepted and if they actually lead to better outcomes. Similarly, we hope to drive favorable long-term outcomes by better understanding how to utilize and interpret biomarkers in this cohort of women.

The Basel PPHT Register is comprised of a cohort of technologically perceptive women who gave birth during a pandemic. Although the conception of the study occurred in 2019 before we could have imagined a global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, this event acted as a catalyst for the hospital to quickly accept and opportunely implement the idea of a home-based management strategy. In general, a positive aspect of the pandemic was that it pushed telemonitoring further and faster than anyone could have imagined. The pandemic instigated the acceptance of patients to stay out of the hospital and embrace a new health care management modality.

Interestingly, although the majority of this cohort had preeclampsia at 53%, Gestational hypertension was seen in 27.3% and de Novo PPHT in 18.3%. This is important and differentiates this cohort to others because generally the focus in postnatal care is focused on patients with preeclampsia or eclampsia, but as demonstrated in this cohort PE only only accounts for just over half of the population with elevated BP values after birth.

A positive family history of cardiovascular disease was seen in about half of the cohort. This is of extreme interest because it could potentially help in screening and increase awareness about this disease in women of childbearing age[

16]. This is interesting since we know that intrauterine exposure to HDP is an epigenetic trigger for hypertension in offspring of women with this disease[

17].

In this population, 23 % of the women in our cohort were already determined to be high risk for preeclampsia during the current pregnancy and 29% were taking aspirin. This is especially interesting when we considered that 51% of the cohort had preeclampsia. This implies that with the actual and local risk screening methods, not all patients are identified in Switzerland and correlates to the fact that screening is only done in a handful of large hospitals and specialized private clinics in the country. Almost three quarters of the cohort had a cesarean section, which is associated with more complications than vaginal birth for the current pregnancy and future pregnancies[

18]. 21% of the women gave birth to a newborn with intrauterine growth restriction which is in itself a cardiovascular risk factor offspring later in life[

19]. This aspect of HDP and PPHT is again associated with poor outcomes[

20].

Most women were taking an antihypertensive medication at baseline. According to guidelines, a switch to longer acting and more beneficial medications such as enalapril should be made after giving birth. In most cases, we switched the patients to metoprolol and enalapril with nifedipine as a third line or reserve medication after delivery. Enalapril is especially justified because of its cardiac and renal protective properties, which have been described in the literature[

15]. However, it should be noted that usually the focus of management of PPHT is directed at women with preeclampsia or eclampsia and not with other causes of PPHT such as chronic hypertension or de novo PPHT. The benefit of a more customized therapy strategy based on the various causes need to be looked at in future studies.

After birth, blood pressure is dynamic and can rapidly increase or decrease[

21]. With 99% of the cohort having an indication for antihypertensive medication after delivery, it is clear, that a structured and supervised titration of medication after discharge should be carried out in women with postpartum hypertension. This is in line with the NICE guidelines that recommend tight controls in the postpartum period[

6]. Within our management model, we usually recommend starting blood pressure measurements directly after hospital discharge.

The findings show that women with a high cardiovascular risk, hypertension during pregnancy and postpartum hypertension clearly have many alarming characteristics that set them apart from the regular population during but also after their pregnancy. In the future, this should be taken into account and management strategies should be put into place before the stress of birth takes over.

Data of this analysis showed that the home-based management model we offered was highly accepted in this patient group. The questions remains whether home based management, results in better and safer outcomes in general. In 2022, the European Society of Hypertension published a consensus document regarding the virtual management of hypertension and lessons learned from pandemic. This consensus document provides guidance on structures/SOP specifications for BP measurement, data transmission, communication with the patient, and follow-up [

11]. In our cohort, we implemented many similar strategies. We are still a long way from a complete virtual management; however, the immediate post-hospital setting is very suitable for a hybrid approach in this group of patients. The follow up of our registry will answer the questions about feasibility, adherence to a home-based management approach and efficacy and safety.

Strength and Limitations

The nested substudy was originally meant to be technically randomized based on having an iPhone as the Telemonitoring App that was implemented, only works on an iOS System. However, in light of the SARS-COV2 Pandemic we reevaluated the necessity and importance of allowing all participants to choose their management strategy esp. since routine care capacities were highly reduced during the lock-down periods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

Roche Diagnostics Switzerland supported the Biomarker substudy. Dr. Thenral Socrates received funding from the University of Basel Research Fund for Excellent Junior Researchers and from the Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Basel.

Abbreviations

| PIH |

Pregnancy Induced Hypertension |

| PPHT |

Postpartum Hypertension |

| HBPM |

Home Blood Pressure Monitoring |

| HBTMS |

Home based telemonitoring management strategy |

| EKNZ |

Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (Ethics Commission Northwest and Central Switzerland) |

| BPM |

blood pressure measurement |

| OBPM |

Office Blood Pressure Monitoring |

| CRF |

Case Reporting Form |

| OB/GYN |

obstetrics/gynecology |

| BP |

blood pressure |

| SOP |

standard operating procedure |

| SOC |

standard of care |

| NSAIDs |

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents |

| AOBPM |

automated office blood pressure measurement |

| NT- pro BNP |

N-terminales pro Brain naturietic peptide |

| sFlt-1 |

soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 |

| PIGF |

placenta like growth factor |

| IL6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| PCT |

procalcitonin |

| GDF-15 |

growth/differentiation factor-15 |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| TTE |

transthoracic echocardiography |

References

- Katsi, V.; Skalis, G.; Vamvakou, G.; Tousoulis, D.; Makris, T. Postpartum Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, L.A.; Pels, A.; Helewa, M.; Rey, E.; von Dadelszen, P. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: executive summary. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014, 36, 416–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibai, B.M. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012, 206, 470–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abalos, E.; Cuesta, C.; Grosso, A.L.; Chou, D.; Say, L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013, 170, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamilio, D.M.; Beckham, A.J.; Boggess, K.A.; Jelovsek, J.E.; Venkatesh, K.K. Risk factors for postpartum readmission for preeclampsia or hypertension before delivery discharge among low-risk women: a case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021, 3, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, C.W. Hypertension in pregnancy: the NICE guidelines. Heart. 2011, 97, 1967–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgione, V.; Ridder, A.; Kalafat, E.; Khalil, A.; Thilaganathan, B. Incidence of postpartum hypertension within 2 years of a pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bjog. 2021, 128, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, K.L.; Bergdall, A.R.; Crain, A.L.; JaKa, M.M.; Anderson, J.P.; Solberg, L.I.; Sperl-Hillen, J.; Beran, M.; Green, B.B.; Haugen, P.; Norton, C.K.; Kodet, A.J.; Sharma, R.; Appana, D.; Trower, N.K.; Pawloski, P.A.; Rehrauer, D.J.; Simmons, M.L.; McKinney, Z.J.; Kottke, T.E.; Ziegenfuss, J.Y.; Williams, R.A.; O'Connor, P.J. Comparing Pharmacist-Led Telehealth Care and Clinic-Based Care for Uncontrolled High Blood Pressure: The Hyperlink 3 Pragmatic Cluster-Randomized Trial. Hypertension. 2022, 79, 2708–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, K.; Gandhi, S. Postpartum hypertension. Cmaj. 2017, 189, E913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.Y.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; Rolnik, D.L.; O'Gorman, N.; Delgado, J.L.; Akolekar, R.; Konstantinidou, L.; Tsavdaridou, M.; Galeva, S.; Ajdacka, U.; Molina, F.S.; Persico, N.; Jani, J.C.; Plasencia, W.; Greco, E.; Papaioannou, G.; Wright, A.; Wright, D.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018, 52, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Stergiou, G.S.; Omboni, S.; Kario, K.; Renna, N.; Chapman, N.; McManus, R.J.; Williams, B.; Parati, G.; Konradi, A.; Islam, S.M.; Itoh, H.; Mooi, C.S.; Green, B.B.; Cho, M.C.; Tomaszewski, M. Virtual management of hypertension: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic-International Society of Hypertension position paper endorsed by the World Hypertension League and European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2022, 40, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derendinger, F.C.; Vischer, A.S.; Krisai, P.; Socrates, T.; Schumacher, C.; Mayr, M.; Burkard, T. Ability of a 24-h ambulatory cuffless blood pressure monitoring device to track blood pressure changes in clinical practice. J Hypertens. 2024, 42, 662–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, B.S. Validation of the Welch Allyn SureBP (inflation) and StepBP (deflation) algorithms by AAMI standard testing and BHS data analysis. Blood Press Monit. 2011, 16, 96–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vischer, A.S.; Hug, R.; Socrates, T.; Meienberg, A.; Mayr, M.; Burkard, T. Accuracy of abbreviated protocols for unattended automated office blood pressure measurements, a retrospective study. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0248586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormesher, L.; Higson, S.; Luckie, M.; Roberts, S.A.; Glossop, H.; Trafford, A.; Cottrell, E.; Johnstone, E.D.; Myers, J.E. Postnatal Enalapril to Improve Cardiovascular Function Following Preterm Preeclampsia (PICk-UP):: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Feasibility Trial. Hypertension. 2020, 76, 1828–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, E.; Prasanna, D.; Brima, W.; Jim, B. Preeclampsia: Updates in Pathogenesis, Definitions, and Guidelines. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016, 11, 1102–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsnes, I.V.; Vatten, L.J.; Fraser, A.; Bjørngaard, J.H.; Rich-Edwards, J.; Romundstad, P.R.; Åsvold, B.O. Hypertension in Pregnancy and Offspring Cardiovascular Risk in Young Adulthood: Prospective and Sibling Studies in the HUNT Study (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study) in Norway. Hypertension. 2017, 69, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandall, J.; Tribe, R.M.; Avery, L.; Mola, G.; Visser, G.H.; Homer, C.S.; Gibbons, D.; Kelly, N.M.; Kennedy, H.P.; Kidanto, H.; Taylor, P.; Temmerman, M. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018, 392, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławek-Szmyt, S.; Kawka-Paciorkowska, K.; Ciepłucha, A.; Lesiak, M.; Ropacka-Lesiak, M. Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction as Risk Factors of Future Maternal Cardiovascular Disease—A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022, 11, 6048. [Google Scholar]

- Lausman, A.; Kingdom, J. Intrauterine growth restriction: screening, diagnosis, and management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013, 35, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.J.; Pullon, R.; Mackillop, L.H.; Gerry, S.; Birks, J.; Salvi, D.; Davidson, S.; Loerup, L.; Tarassenko, L.; Mossop, J.; Edwards, C.; Gauntlett, R.; Harding, K.; Chappell, L.C.; Knight, M.; Watkinson, P.J. Postpartum-Specific Vital Sign Reference Ranges. Obstet Gynecol. 2021, 137, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).