Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- dengue virus (DENV);

- yellow fever virus (YVF);

- japanese encephalitis virus (JEV);

- west Nile virus (WEV);

2. Materials and Methods

- Culiseta;

- Aedes;

- Anopheles.

3. Results

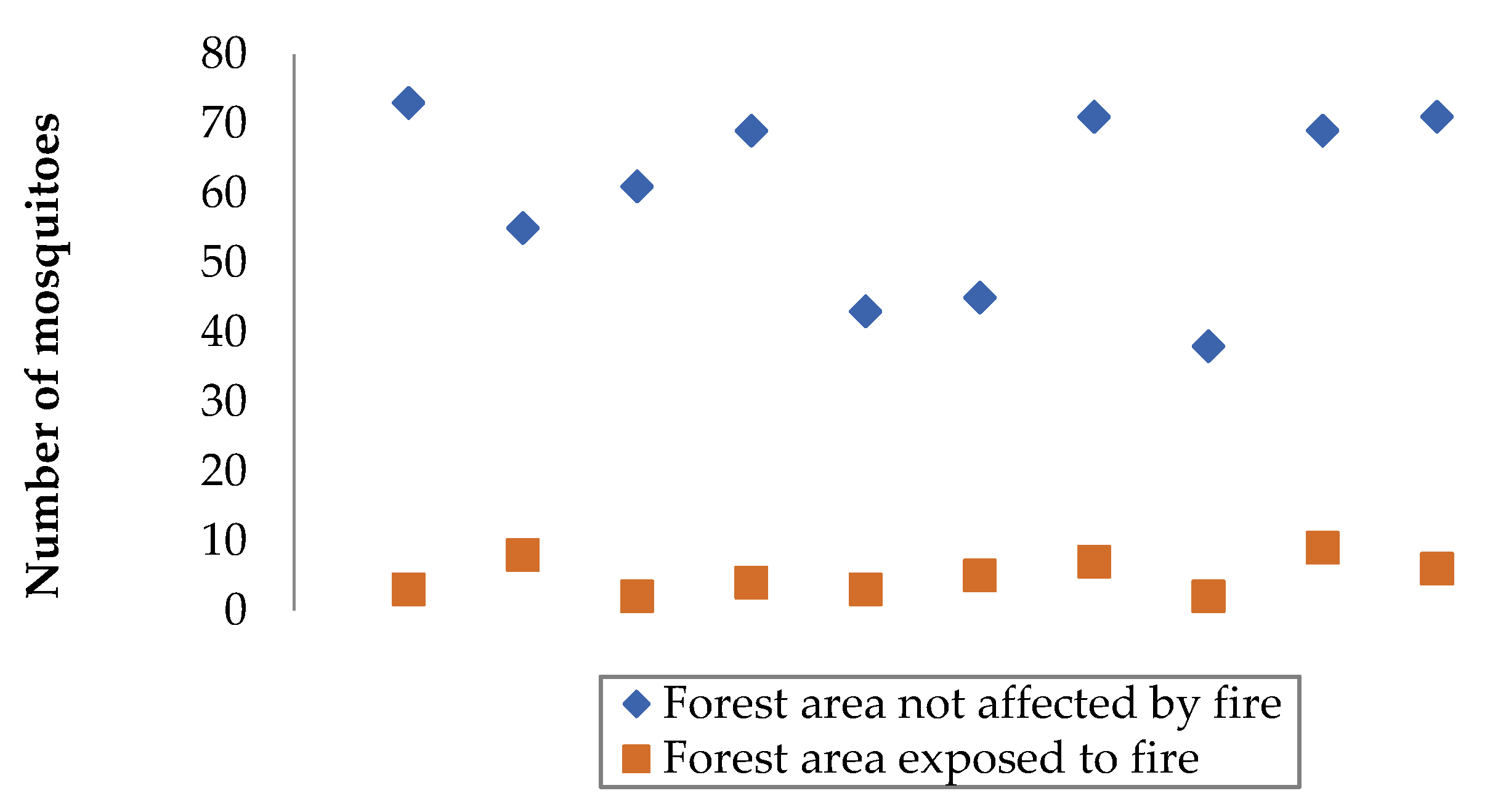

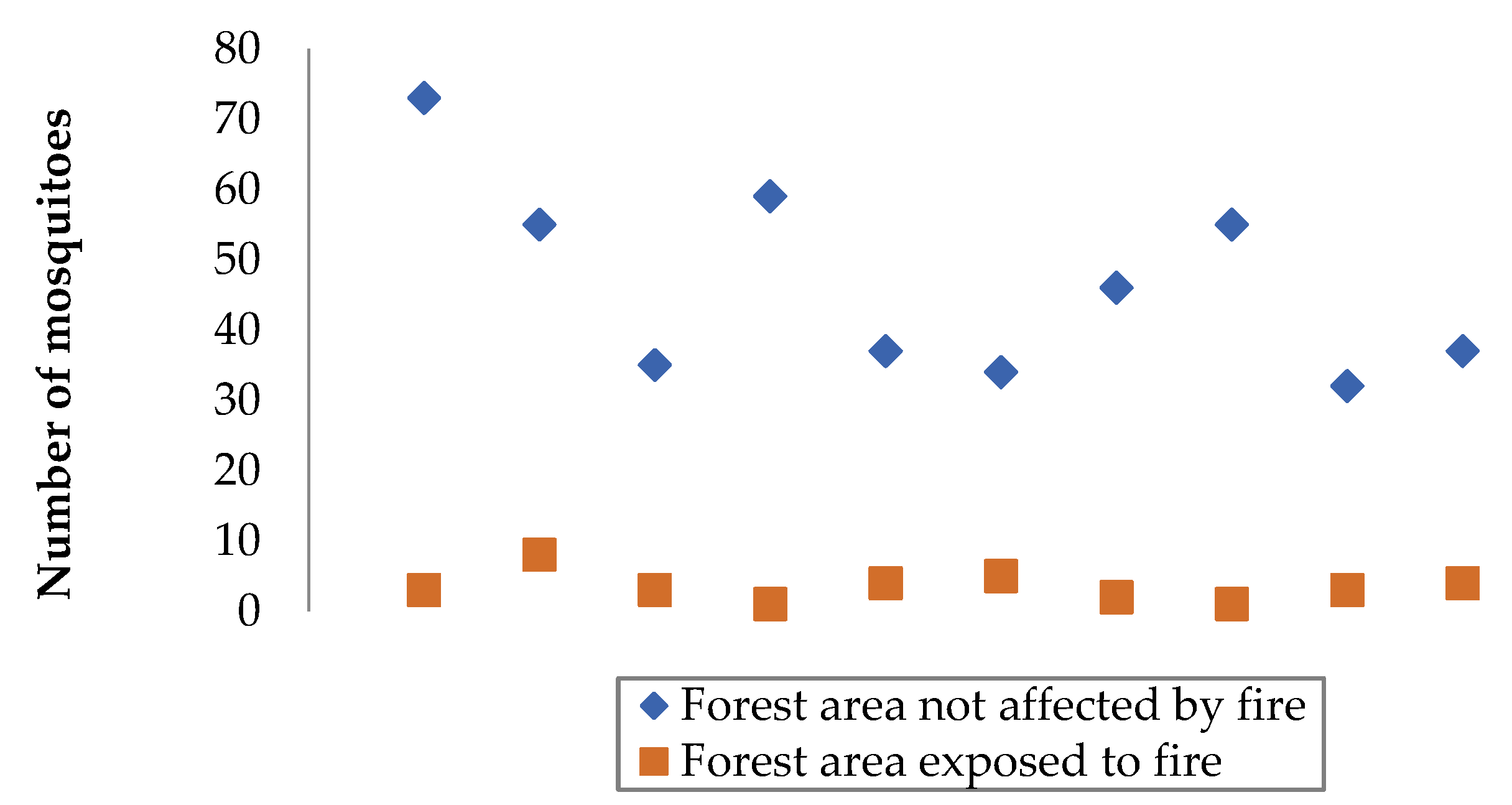

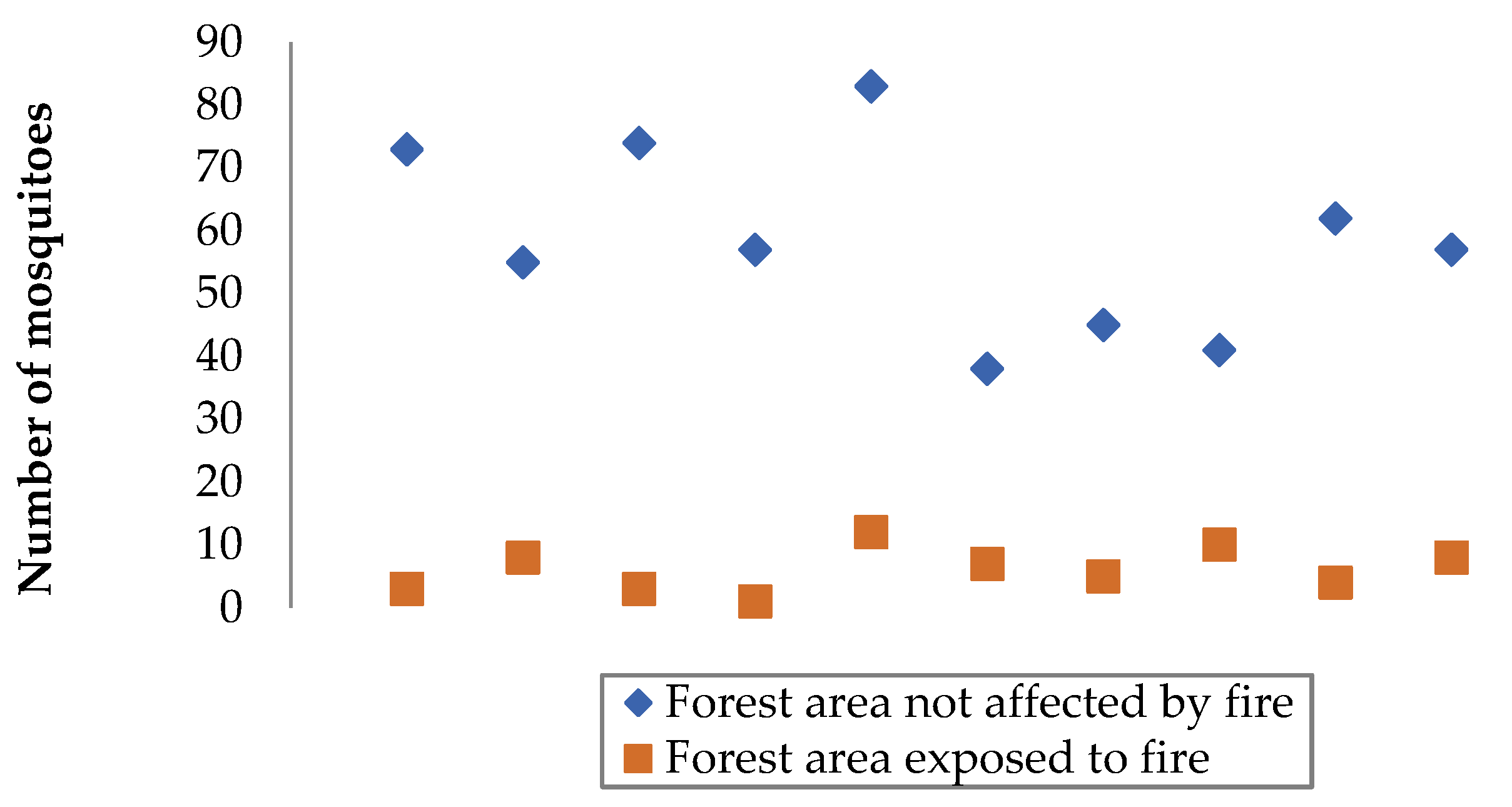

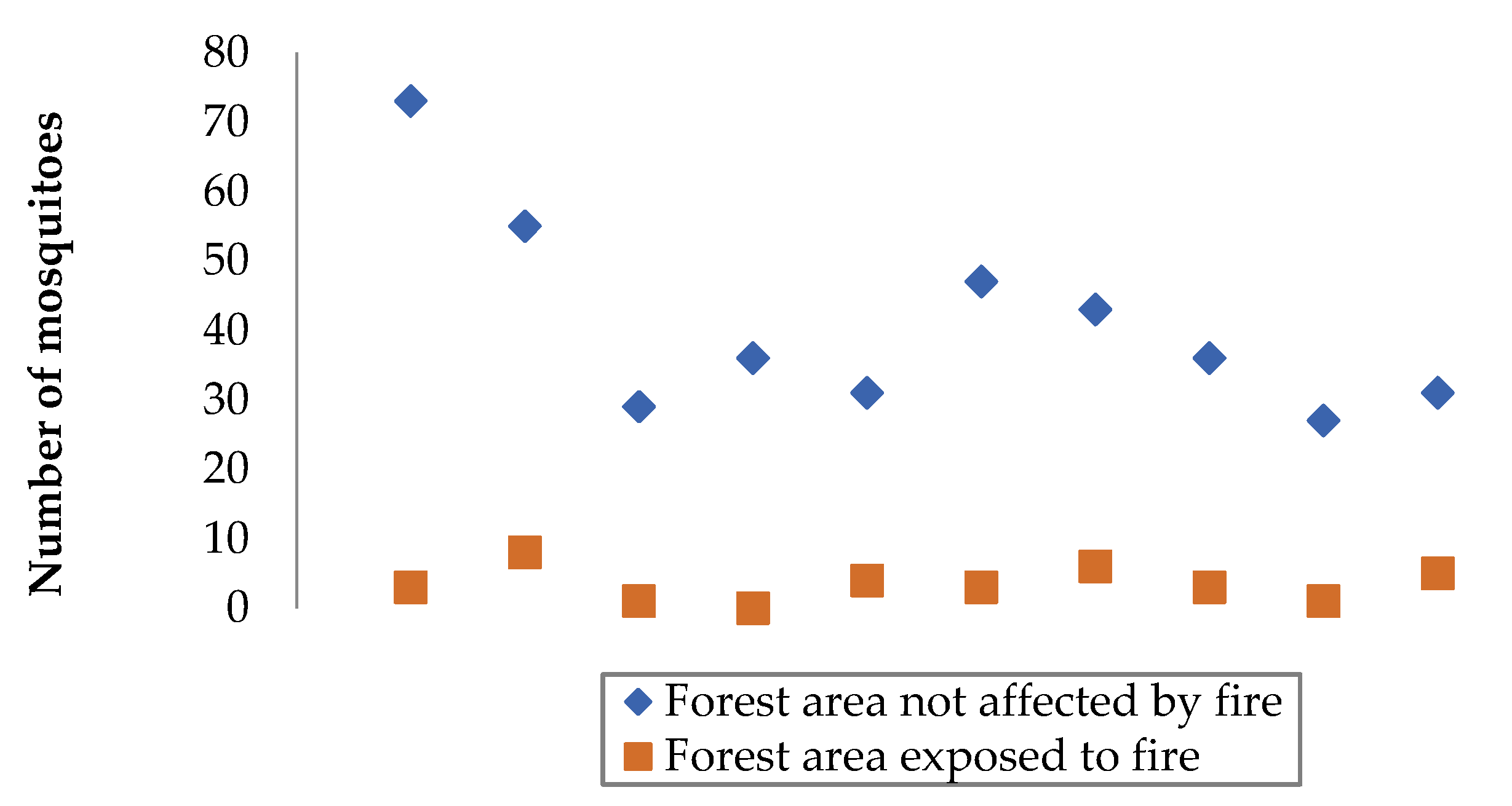

3.1. Comparison of Data from Selected Forest Areas

3.2. Processing the Experimental Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ash WW. Forest fires: their destructive work, causes and prevention. 1895; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.34531. [CrossRef]

- Bell, R. Forest Fires in Northern Canada. fire ecol 8, 3–10 (2012).https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400621. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Jin H, Wang H, Wu X, Huang Y, He R, et al. Distributive features of soil carbon and nutrients in permafrost regions affected by forest fires in northern Da Xing'anling (Hinggan) Mountains, NE China. CATENA [Internet]. 2020 Feb;185:104304. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104304. [CrossRef]

- Stocks B.J. The Extent and Impact of Forest Fires in Northern Circumpolar Countries. Global Biomass Burning [Internet]. 1991 Nov 27;197–202. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3286.003.0030. [CrossRef]

- Richardson E, Stirling I, Kochtubajda B. The effects of forest fires on polar bear maternity denning habitat in western Hudson Bay. Polar Biology [Internet]. 2006 Aug 17;30(3):369–78. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00300-006-0193-7. [CrossRef]

- Z. Klimont, K. Kupiainen, C. Heyes, P. Purohit, J. Cofala, P. Rafaj, J. Borken-Kleefeld, W. Schöpp. Global anthropogenic emissions of particulate matter including black carbon. Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17 (2017), pp. 8681-8723. [CrossRef]

- McCoy V. Climate change and forest fires in Yukon Territory. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/etd/2002-05301. [CrossRef]

- Merino A, Fontúrbel MT, Jiménez E, Vega JA. Contrasting Immediate Impact of Prescribed Fires and Experimental Summer Fires on Soil Organic Matter Quality and Microbial Properties in the Forest Floor and Mineral Soil in Mediterranean Black Pine Forest. 2023; Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4548571. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, E.; Dickman, C. Mechanisms of Recovery after Fire by Rodents in the Australian Environment. Wildl. Res. 1999, 26, 405–419. [CrossRef]

- Garcês, A.; Pires, I. The Hell of Wildfires: The Impact on Wildlife and Its Conservation and the Role of the Veterinarian. Conservation 2023, 3, 96-108.https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation3010009. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, L.J.; Crawford, H.S.; Czuhai, E.; Fredriksen, R.L.; Harlow, R. F.; Metz, L.J.; Pearson, H. A.; States, U. Effects of Fire on Fauna: A State-of-Knowledge Review; US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; pp. 1–52.

- Wiebe, K. Microclimate of Tree Cavity Nests: Is It Important for Reproductive Success in Northern Flickers? Auk 2001, 118, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Fonseca, F. How Wildfires Impact Wildlife and Their Habitats. Available online:https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/explainer-how-wildfires-impact-wildlife-their-habitat(accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Certini, G. Effects of Fire on Properties of Forest Soils: A Review. Oecologia 2005, 143, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Moody, J.A.; Martin, D. A. Initial Hydrologic and Geomorphic Response Following a Wildfire in the Colorado Front Range. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2001, 26, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.Q.; Passos, C. J. S.; Muniz, D. H. F.; Oliveira-Filho, EC Aquatic Ecotoxicity of Ashes from Brazilian Savanna Wildfires. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 19671–19682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed].

- Goode, JR; Luce, CH; Buffington, J.M. Enhanced Sediment Delivery in a Changing Climate in Semi-Arid Mountain Basins: Implications for Water Resource Management and Aquatic Habitat in the Northern Rocky Mountains. Geomorphology 2012, 139–140, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Fowler, DA Treating Burnt Wildlife. Available online:https://www.ava.com.au/siteassets/library/other-resources/treating-burnt-wildlife-2020-dr-anne-fowler.pdf(accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Latham D, Williams E. Lightning and Forest Fires. Forest Fires [Internet]. 2001;375–418. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-012386660-8/50013-1. [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau P. Forest Fires. Natural Complexity [Internet]. 2017 May 16; Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691176840.003.0006. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Kobayashi H, Nagai S, Ueyama M, Lee BY, Suzuki R. Boreal Forest and Forest Fires. Arctic Hydrology, Permafrost and Ecosystems [Internet]. 2020 Aug 29;615–55. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50930-9_21. [CrossRef]

- Amiro BD et al (2010) Ecosystem carbon dioxide fluxes after disturbance in forests of North America. J Geophys Res 115:G00K92.https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jg001390. [CrossRef]

- Forest fires “are speeding up Arctic ice melt”. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal [Internet]. 2006 Nov 1;17(6). Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/meq.2006.08317fab.003. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Rajput, N.S.; Shvetsov, A. V.; Saif, A.; Sahal, R.; Alsamhi, SH ID2S4FH: A Novel Framework of Intelligent Decision Support System for Fire Hazards. Fire 2023, 6, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6070248. [CrossRef]

- Mahmudnia D, Arashpour M, Bai Y, Feng H. Drones and Blockchain Integration to Manage Forest Fires in Remote Regions. Drones [Internet]. 2022 Oct 30;6(11):331. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/drones6110331. [CrossRef]

- Waite H. Mosquitoes and Malaria. A Study of the Relation between the Number of Mosquitoes in a Locality and the Malaria Rate. Biometrika [Internet]. 1910 Nov;7(4):421. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2345376. [CrossRef]

- Kolpakova TA Epidemiological survey of the Vilyui district of the YaSSR. L.: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1933; 12: 292. (In Russ.

- Shtakelberg AA Family Culicidae. Blood-sucking mosquitoes (subfamily Culicinae): Fauna of the USSR. Dipterans. M.-L.: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1937; 3 (4): 258. (In Russ.).

- Qiao J., Liu Q. Interplay between autophagy and Sindbis virus in cells derived from key arbovirus vectors, Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Cellular Signaling. 2022; 90: 110204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110204. [CrossRef]

- Isa I., Ndams I. Sh., Aminu M. et al. Genetic diversity of Dengue virus serotypes circulating among Aedes mosquitoes in selected regions of northeastern Nigeria. One Health. 2021; 13: 100348. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100348. [CrossRef]

- Rasnitsyn SP, Kosovskikh VL An improved method to record the mosquito abundance with a net around a person and to compare it with a dark cloth bell. Meditsinskaya parazitologiya i parazitarnyye bolezni = Medical parasitology and parasitic diseases. 1979;1: 18-24. (In Russ.).

- Rueda LM, Debboun M. Taxonomy, Identification, and Biology of Mosquitoes. Mosquitoes, Communities, and Public Health in Texas [Internet]. 2020;3–7. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-814545-6.00001-8. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Ecology: A world without mosquitoes. Nature 466, 432–434 (2010).https://doi.org/10.1038/466432a. [CrossRef]

- Kamerow D. The world's deadliest animal. BMJ [Internet]. 2014 May 15;348(may15 2):g3258–g3258. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3258. [CrossRef]

- Snyder T. The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator. Emerging Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2020 Oct;26(10):2536–2536. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2610.202806. [CrossRef]

- Reuters.Smoke from forest fires engulfs city in Russia's far east. Available from:https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/smoke-forest-fires-engulfs-city-russias-far-east-2023-08-09/.

- Igini M. Top 12 Largest Wildfires in History. Earth.Org. Available from:https://earth.org/largest-wildfires-in-history/.

- Aaltonen H, Köster K, Köster E, Berninger F, Zhou X, Karhu K, et al. Forest fires in Canadian permafrost region: the combined effects of fire and permafrost dynamics on soil organic matter quality. Biogeochemistry [Internet]. 2019 Mar;143(2):257–74. Available from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10533-019-00560-x. [CrossRef]

- Statista.Countries with the largest annual average loss of tree cover by fires worldwide from 2001 to 2022. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1401419/top-countries-forest-loss-by-fires/#:~:text=Countries%20with%20the%20highest%20average,by%20fires%20worldwide%202001% 2D2022&text=Russia%20has%20had%20the%20highest,cover%20per%20year%20since%202001.

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, G.; Ding, H.; Yu, M. Research Progress of Forest Fires Spread Trend Forecasting in Heilongjiang Province. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2110.https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13122110. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Meng, X.; Yi, H. Research progress on forest fire spread model and spread simulation. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2002, 24, 5.

| Objective of the experiment | Constant factors | Variable factors | Measured parameter | Number of measurements in a separate section | Total number of observation results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To determine the degree of impact of fires on the number of mosquitoes in the affected forest areas | Mosquitoes | Fire | Number of mosquitoes | 10 | 100 |

| A couple of patches of forest | Number of mosquitoes in a forest area exposed to fire, units | Number of mosquitoes in a forest area not affected by fire, units |

|---|---|---|

| First | 63 | 5 |

| Second | 49 | 3 |

| The third | 71 | 6 |

| Fourth | 52 | 7 |

| Fifth | 38 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).