Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

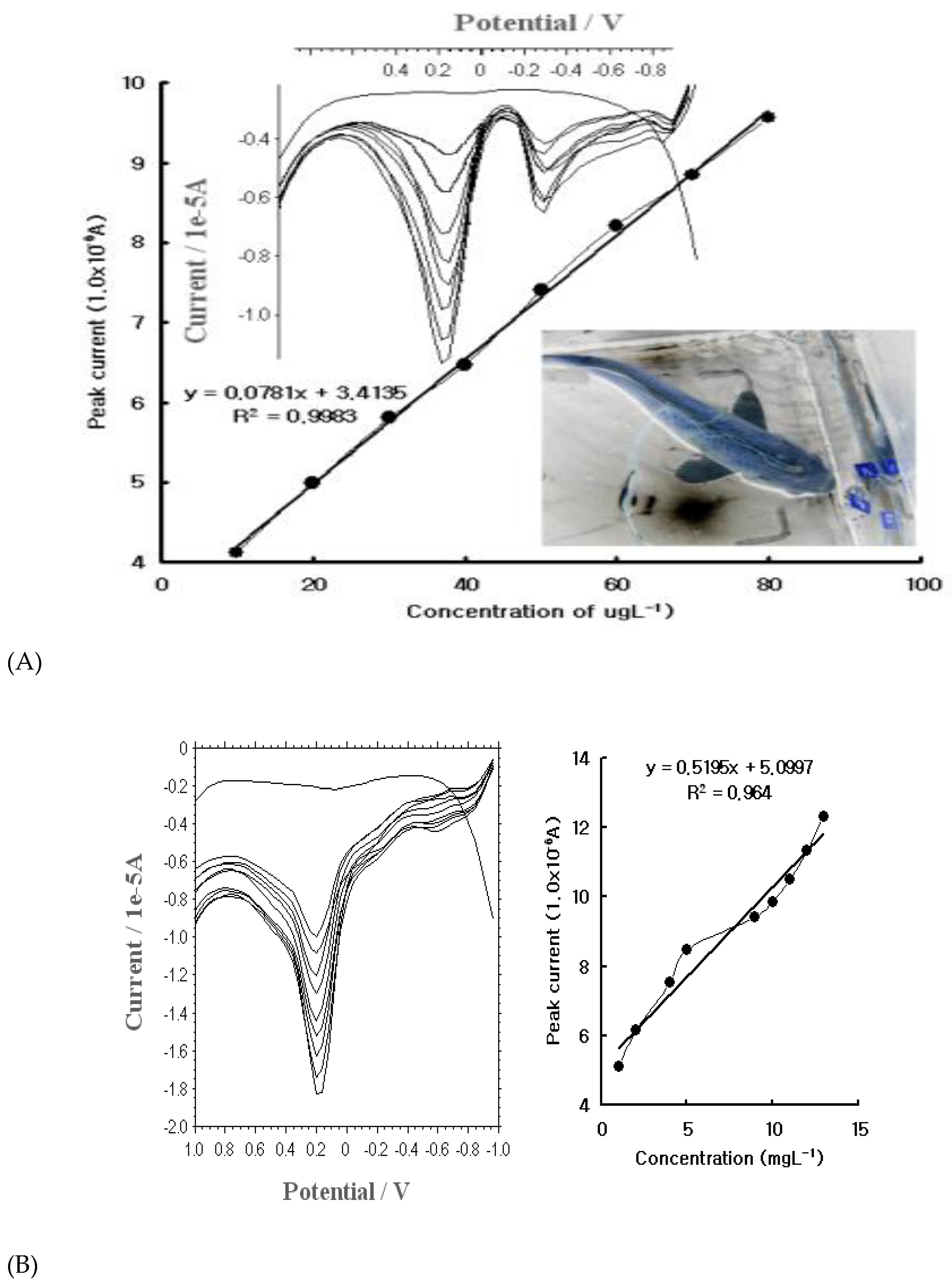

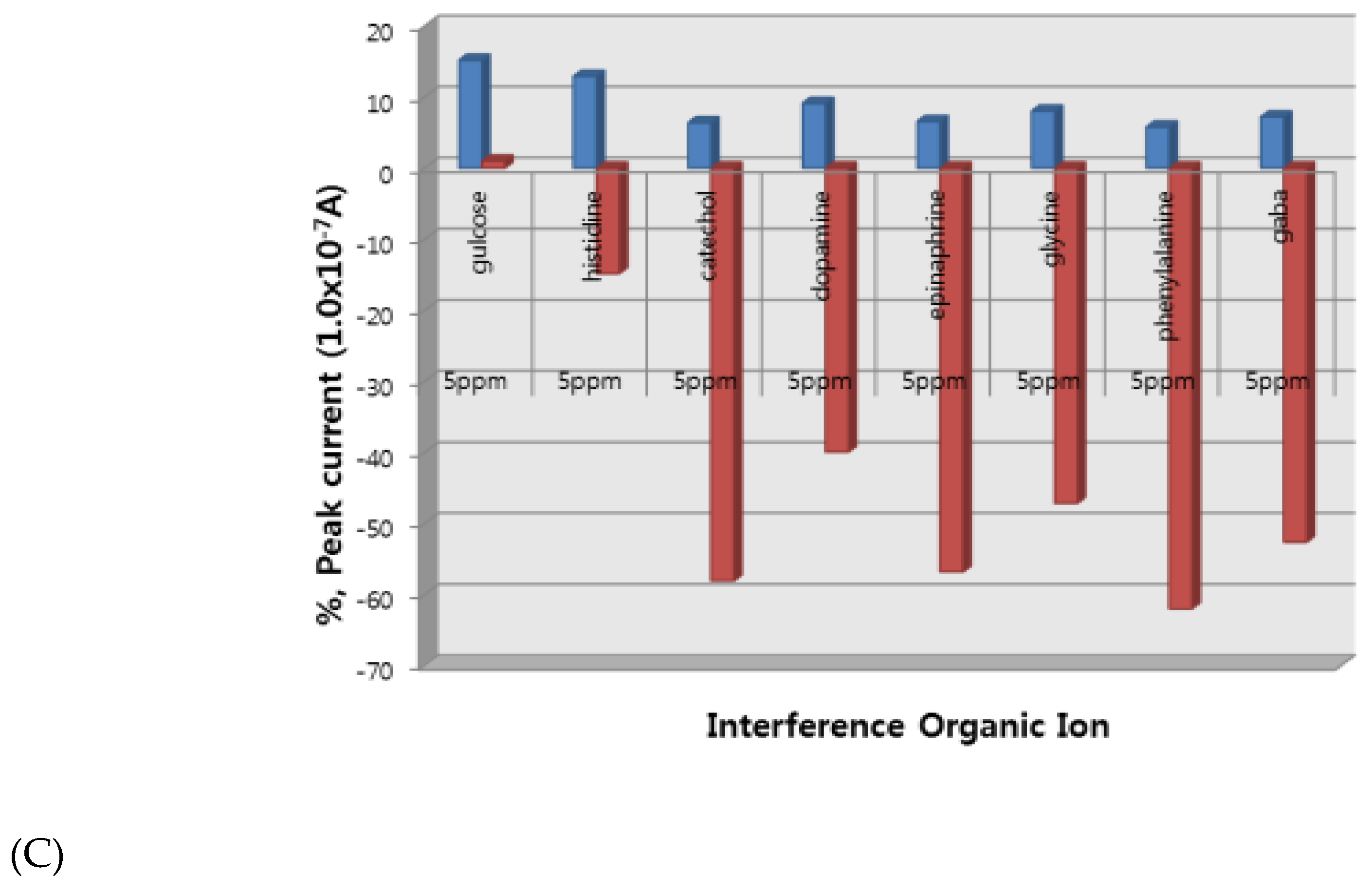

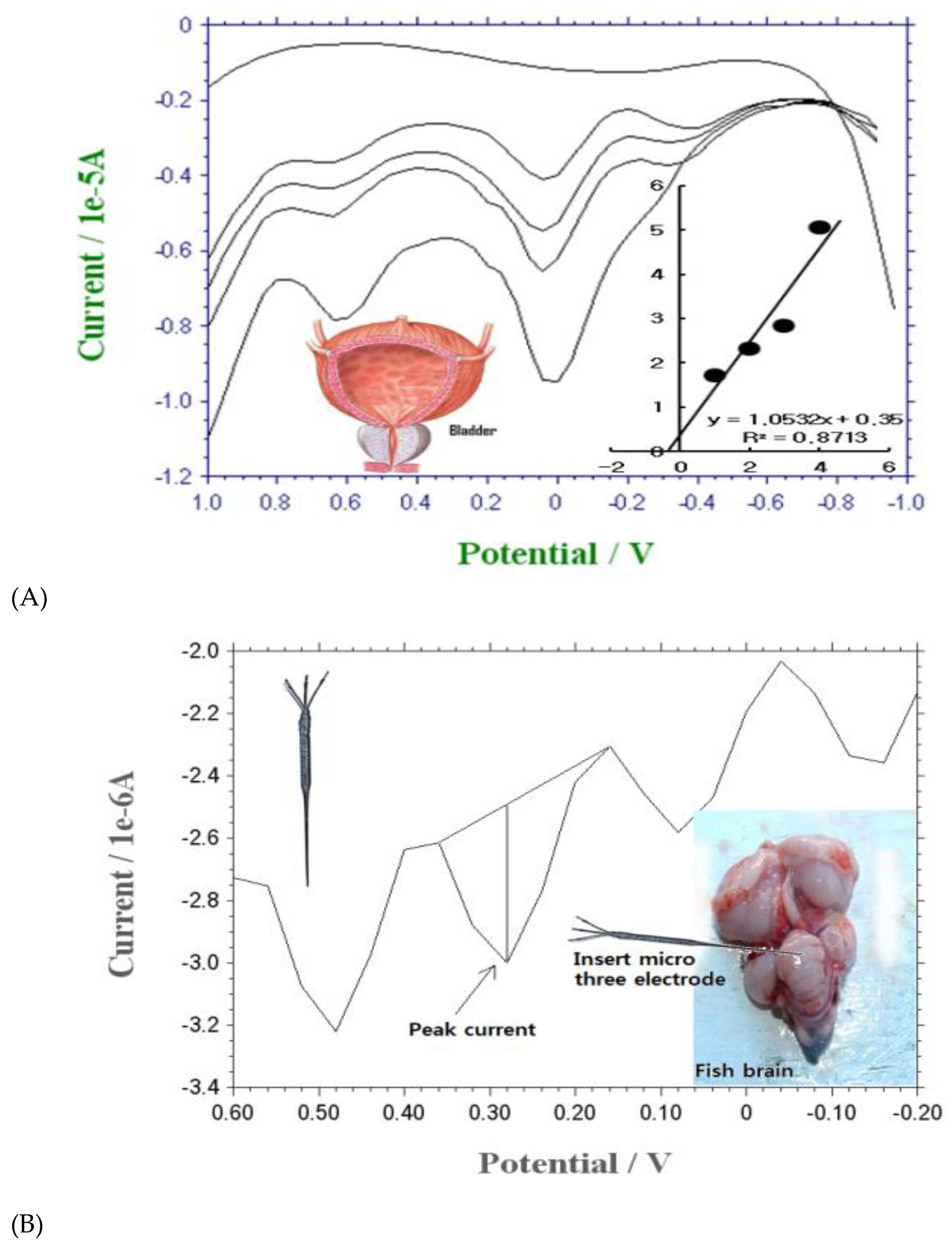

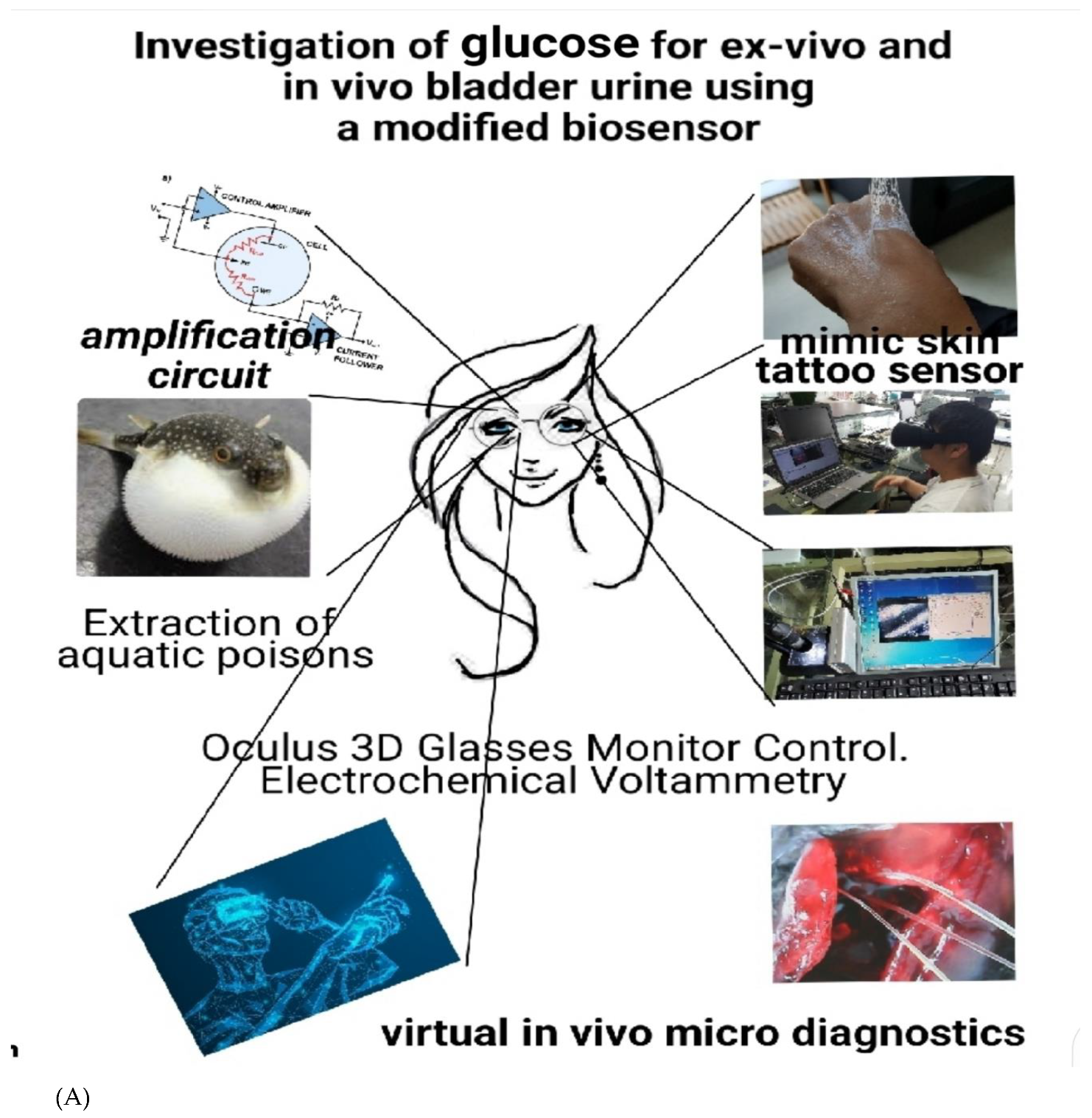

Background/Objective; In-vivo diabetes detection of glucose were sought using square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SW), with bismuth-immobilized carbon nanotube paste electrode (BCE). Methods:The optimum analytical results indicated sensitive peak signals on the BCE. The raw voltammogram was approached within the 1mgL-1-14mgL-1 and 10ugL-1-140 ugL-1, detection limits with preconcentration times of 100 and 200 sec. Results:The relative standard deviation was 0.02 % (n=15) of 10.0 mgL-1 under optimum conditions. The analytical detection limit (S/N) was attained at 8 ugL-1. The handmade microsensor was directly used in vivo on the living fish brain and human urine. Conclusion: The method was applied at real time in vivo, without requiring any pretreatment and other ionic electrolyte solutions. It can be used for medicinal and other materials requiring biological-fluid detection in real time. This study was designed to be suitable for real-time unmanned remote diagnosis and therapeutic drug injection into the body, micro-needle long-term administration, wearable artificial skin tattoo sensor, and real-time control. In addition, the glasses monitor was designed to be suitable for multitasking and multi-user control.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Apparatus and Reagents

2.2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

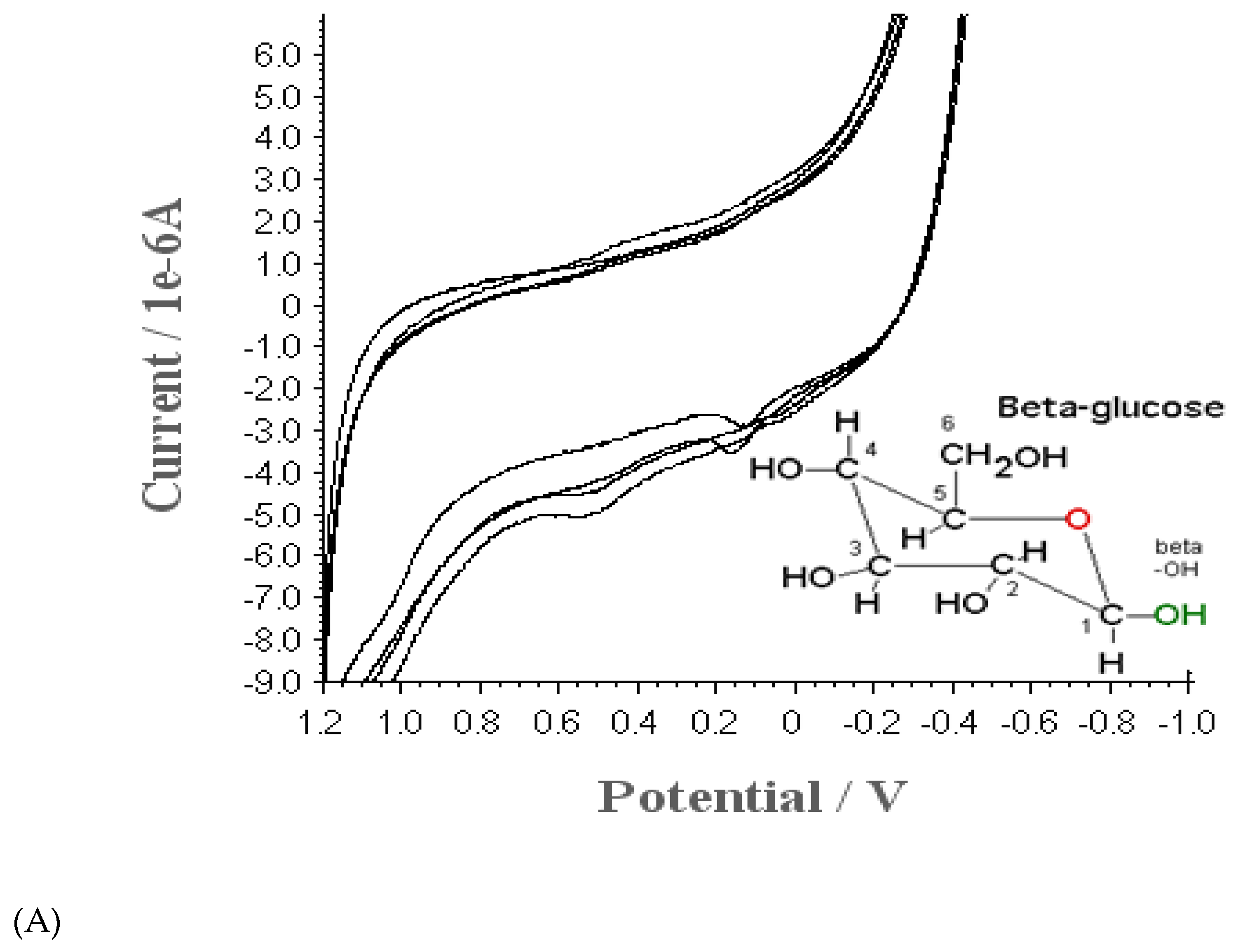

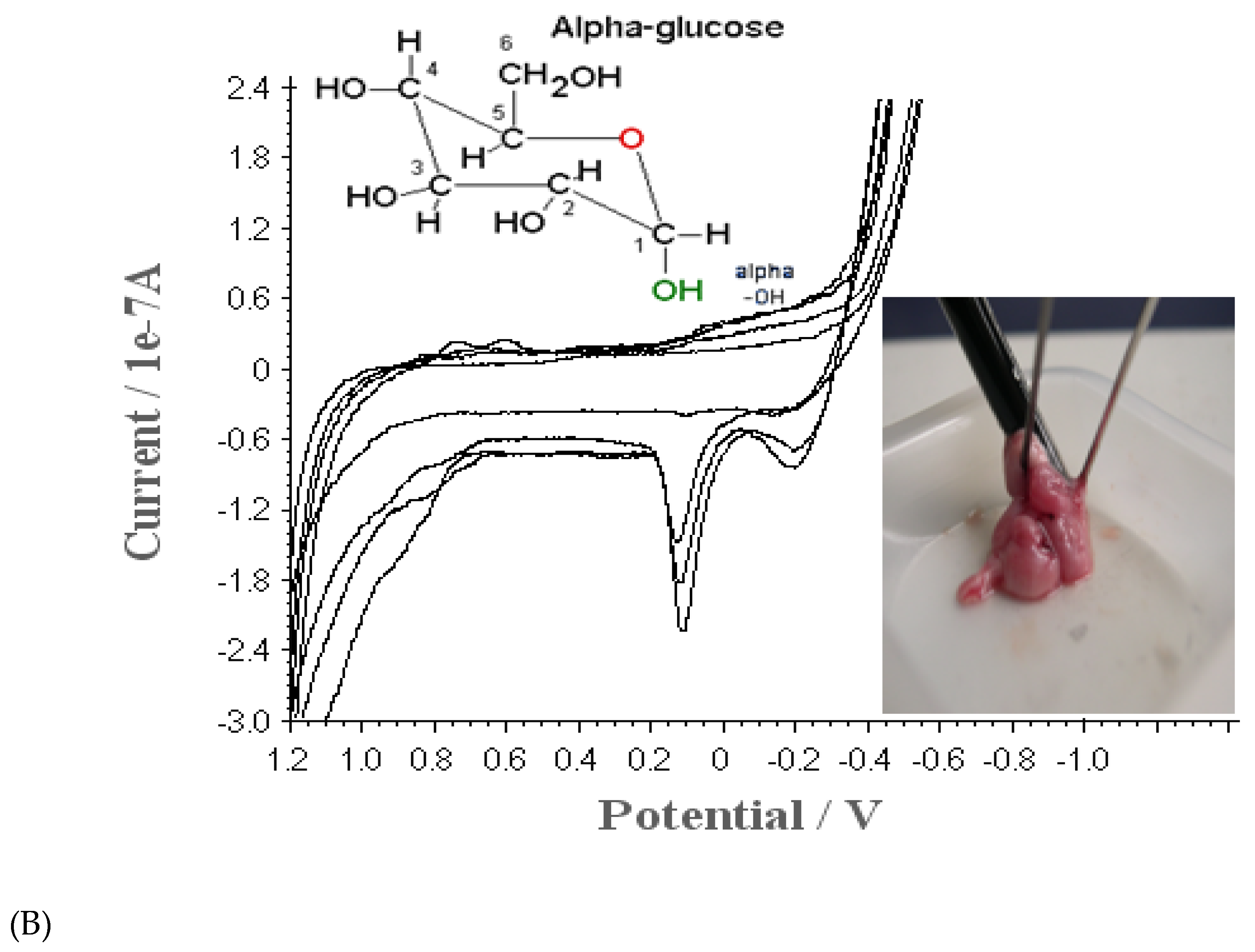

3.1. Cyclic Voltammetric Property of BCE

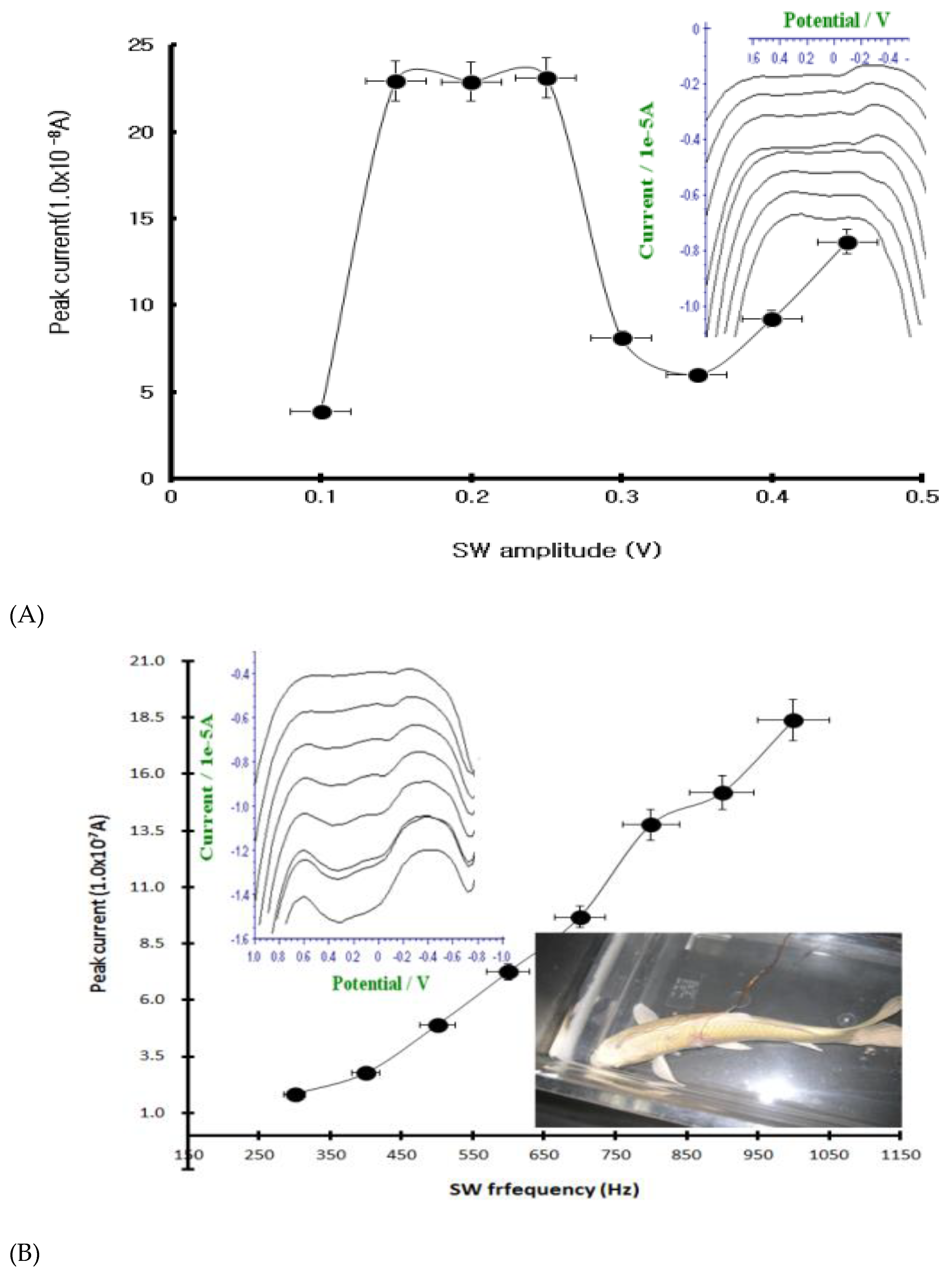

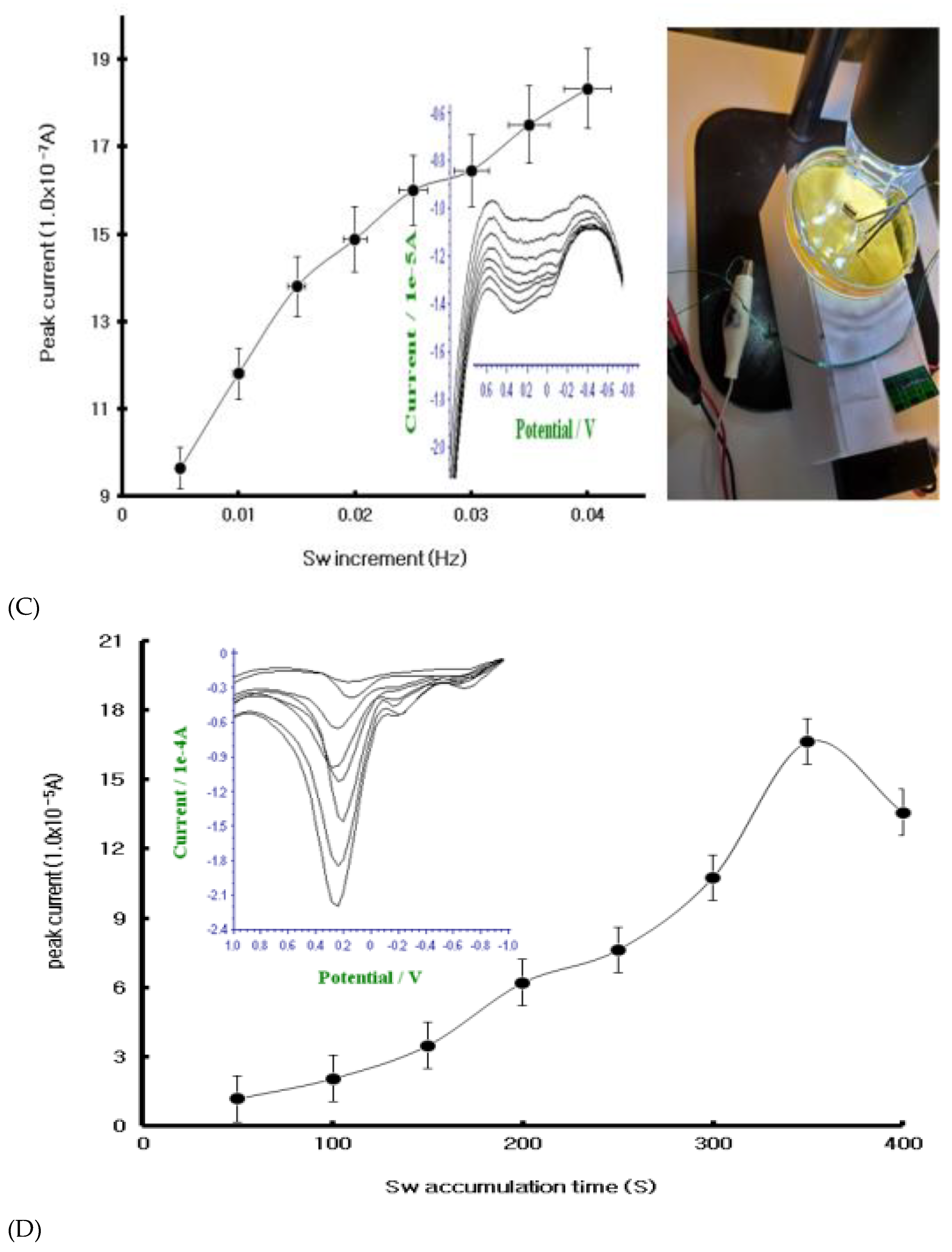

3.2. SW Optimization for BCE

3.3. Analytical Working Ranges, Interference, Statistics, and Application

3.4. Statistics and Application

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interests

Abbreviations

References

- HaoranZhu,YuanZhao,MengmengMi,QiyuZhang,XinFu,YaqingZheng,GuixinQin,LiPan,NanBao. Effects of glucose release kinetics of extruded-maize diet on energy utilization of growing pigs. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2023, 304. 115747. [CrossRef]

- Chengruo Huang, Mingyue Zhang, Chunming Li. A novel non-enzymatic electrochemical glucose sensors based on graphene oxide nanoribbons: Tracking energy expenditure and nutritional intake in sports. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2024, 89. 184-194. [CrossRef]

- Wenran Ren. Jianhui Chen, Wenjing Wang, QingqingLi, Xia Yin, Guanglei Zhuang,Hong Zhou. Wenwen Zeng. Sympathetic nerve-enteroendocrine L cell communication modulates GLP-1 release, brain glucose utilization, and cognitive function.Neuron. 2024, 112 972-990.e8.

- Qinying Zhu, Junhong Du,Yi Li, Xue Qin, Ruifen He,HaoMac, Xiaolei Liang, Downregulation of glucose-energy metabolism via AMPK signaling pathway in granulosa cells of diminished ovarian reserve patients. Gene 2025, 933. 148979. [CrossRef]

- Fan Zhang, Jinghua Tian, Li Wang, Pingang He, Yong Chen, Correlation between cell growth rate and glucose consumption determined by electrochemical monitoring, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2011; 156: 416–422. [CrossRef]

- Graaf RA, Dijkhuizen RM, Biessels GJ, Braun KPJ, Nicolay K: In Vivo Glucose Detection by Homonuclear Spectral Editing. Magnet Reson Med 2000;43:621-626.

- Vojinovic V, Azevedo AM, Martins VCB, Cabral JMS, Gibson TD, Fonseca LP, Assay of H2O2 by HRP catalysed co-oxidation of phenol-4-sulphonic acid and 4-aminoantipyrine: characterisation and optimisation, Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic 2004;28. 129-135. [CrossRef]

- Cortacero SR, Segura AC, Cruces CB, Hernainz MBC, Fernandez AG: Analysis of carbohydrates in beverages by capillary electrophoresis with precolumn derivatization and UV detection. Food Chem 2004;87:471-476.

- Jorge L. Chávez S, Ana IC, Carmen LS: Analysis of mono- and disaccharides in milk-based formulae by high-performance liquid chromatography with refractive index detection. J Chromatograpy, 2004;1043:211–215.

- Katsuhiko M, Mitsuhiro T, Jakusei C, Tomohiro O: Hidenobu A, Yukio Y, Mamoru T, Masataka I, Yukihiro O, Noninvasive Blood Glucose Assay Using a Newly Developed Near-Infrared System. IEEE J Sel Top Quant, 2003;9.2.

- PuigLleixa C, Jimenez C, Bartroli J: Acrylated polyurethane Ð photopolymeric membrane for amperometric glucose biosensor construction. Sensor Actuat B-HEM 2001;72. 56-62.

- In HY, Dennis CJ: Anodic response of glucose at copper-based alloy electrodes. J Electroanal Chem 2000;484: 157–163.

- In HY1, Dennis CJ: Electrochemical response of small organic molecules at nickel–opper alloy electrodes. J Electroanal Chem 2001;495:110–119.

- Carlos A. Galan V, Javier M, Carlos D, Salvador A: Glucose biosensor based on a reagentless graphite-epoxy screen-printable biocomposite. Sensor Actuat B-HEM 1997;45.55–62.

- Pandey PC, Upadhyay S, Pathak HC: A new glucose sensor based on encapsulated glucose oxidase within organically modified sol-gel glass. Sensor Actuat B-HEM 1999;60:83–89.

- Suye S, Matsuura T, Kimura T, Zheng H, Hori T, Amano Y, Katayama H: Amperometric DNA sensor using gold electrode modified with polymerized mediator by layer-by-layer adsorption. Microelectron Eng 2005;81:441–447.

- Chuang CL, Wang YJ, Lan HL: Amperometric glucose sensors based on ferrocene-containing B-polyethylenimine and immobilized glucose oxidase. Anal Chim Acta 1997;353:37-44.

- Kay HA, Won SK, Young SP, Jeong MM, Dong JB, Seong CL, Young SL, Young HL: Electrochemical Properties of High-Power Supercapacitors Using Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2001;11:387-392.

- Eugenii K, Itamar W: Biomolecule-Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes: Applications in Nanobioelectronics. ChemPhysChem 2004; 5:1084-1104.

- Gunther W, Axel S, Rudiger S, Gerhard W: Glucose oxidation at bismuth-modified platinum electrodes. J Electroanal Chem 1998; 444: 61–73.

- Emily AH, Samo BH. Lea M, Bozidar O. Bismuth film electrode for anodic stripping voltammetric determination of tin. Anal Chim Acta 2006; 580: 244-250.

- Gunther W, Axel S, Rudiger S, Gerhard W: Glucose oxidation at bismuth-modified platinum electrodes. J Electroanal Chem 1998;444: 61-73.

- In Hea Cho, Kwang Jin Choi, Ji Hyun Kim, Kyung Lee, Suw Young Ly. Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus Molecules in Non-Treated Blood Using Mercury Immobilized Carbon Nanotube Sensor. Molecules. 2022,27(6), 1837. [CrossRef]

- Dong Ho Kim, Jeeyu Choi, Hyeon Jeong Park, Jeannette Sahnghee Kim, Kyung Lee, SuwYoung Ly, Virtual Rapid Sensing of Covid-19 Virus Antibodies in Patients Blood by Using Platinized Antigen Linking Graphene Probe, Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 2022, 42,5, 34021-34028. [CrossRef]

- Suw Young Ly, Hwa Jin Heo, Min Jung Kim, Real Time Analysis of Neurotransmitters in the Brain Using a Micro-Electrode, Current Neurovascular Research 7, 2010: 32 - 38. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).