1. Introduction

The efficiency of the human reproductive treatment process during the last 10 years has not increased dramatically over despite massive advances in methods and the development of a range of add-on approaches. The chance of having a healthy baby is only about 5% per retrieved oocyte [

1]. It seems that one of the reasons for the relatively low efficiency of IVF methods is that we are unable to select sperm efficiently enough to use for IVF. During in vivo fertilization, sperm selection is very thorough at several levels of the female reproductive system, using natural navigation systems such as thermotaxis, chemotaxis, or rheotaxis [

2]. Of the total number of sperm, which is often several hundred million at the beginning, only a few hundred sperm are in the immediate vicinity of the oocyte [

3], and only one sperm reaches the cytoplasm of the oocyte. This means that there is usually a huge surplus of sperm and there is a lot of rooms for selection. Sperm separation in vivo is, therefore, very intense and is a multistep process that starts immediately after ejaculation at the level of cervix uteri [

4] and continue to the fine selection processes in oviduct [

5]. Spermatozoa populations exhibit significant heterogeneity, with only a small subset within the ejaculate retaining the capacity for fertilization [

6].

During in vitro selection, we attempted to make the best selection of sperms for fertilization. In modern assisted reproduction techniques, there is increasing utilization of in vitro fertilization (IVF) employing intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). With ICSI contrary to the older “classical IVF” method, the natural barrier between the oocyte and sperm is no longer maintained, and the selected sperm is injected directly into the cytoplasm of the oocyte. However, given how massively the ICSI technique is used, the most important factor in separating IVF is the efficiency of ICSI. Poor sperm selection before fertilization can have a fatal impact on fertilization success and embryonic development [

7,

8]. Multiple approaches have been proposed for sperm separation under in vitro conditions. Usually, there is an abundance of spermatozoa available, allowing for rigorous selection of spermatozoa. The most commonly used technique for sperm selection for ICSI is swim-up and density gradient (DGC) [

7]. This methods isolates motile sperm with a normal morphology [

7,

9]. Unfortunately, the current methods for sperm selection are not perfect and are not allowed to make an excellent selection for a specific subpopulation that is best for IVF This phenomenon is attributable to several factors. Certain methodologies were initially developed for conventional IVF techniques and subsequently adapted for ICSI. In some instances, limitations are imposed by the operational environment and specimen handling procedures. Frequently, this aspect of IVF is underestimated in clinical settings, and due to the efficiency of the process and the ease of specimen handling, the most straightforward method is often selected. Although this approach yields satisfactory results, it is often used and is predominantly based on the principle of sperm selection according to motility. Selecting defective sperm or those with DNA fragmentation can harm fertilization, embryonic genome activation, and overall embryo development [

10,

11]. Traditional separation techniques, such as swim-up or DGC, are gradually being replaced by new microfluidic sperm sorting (MFSS) systems. These systems are relatively simple, do not require centrifugation, are easy to use, and produce good results when used for IVF of human oocytes [

12,

13,

14]. Techniques using MFSS for human embryo separation are often considered to have a higher sperm selection efficiency for ART techniques than conventional swim-up or DGC methods [

12,

15,

16], this methods may not apply generally to all approaches to the treatment of human infertility. When comparing the effectiveness of the MFSS and swim-up methods in IUI, even better results have been found for swim-up separation [

17].

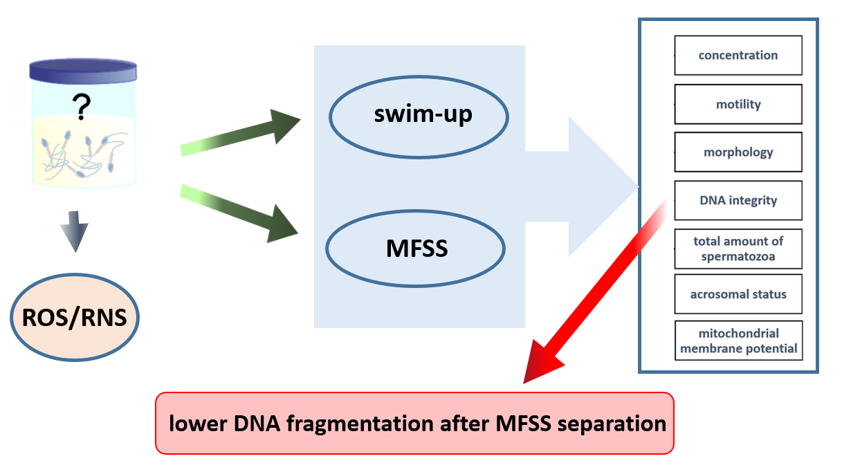

This study evaluates the Ca0 microfluidic chip which is biologically inspired by the sperm’s journey during natural conception. The device incorporates columnar joints that mimic the uterine tubule microenvironment and features a built-in microchannel membrane simulating the narrow uterotubal junction for final sperm selection. This study aimed to compare the swim-up and MFSS methods in terms of sperm selection using unfragmented DNA, mitochondrial respiration, and acrosomal status.

2. Results

2.1. Patients

A total of 45 patients from the CERMED center with average age 32.2 years with an average ejaculate volume 4.19 were enrolled in this study. The mean of the evaluated parameters is described in

Table 1.

2.2. Semen Analyses

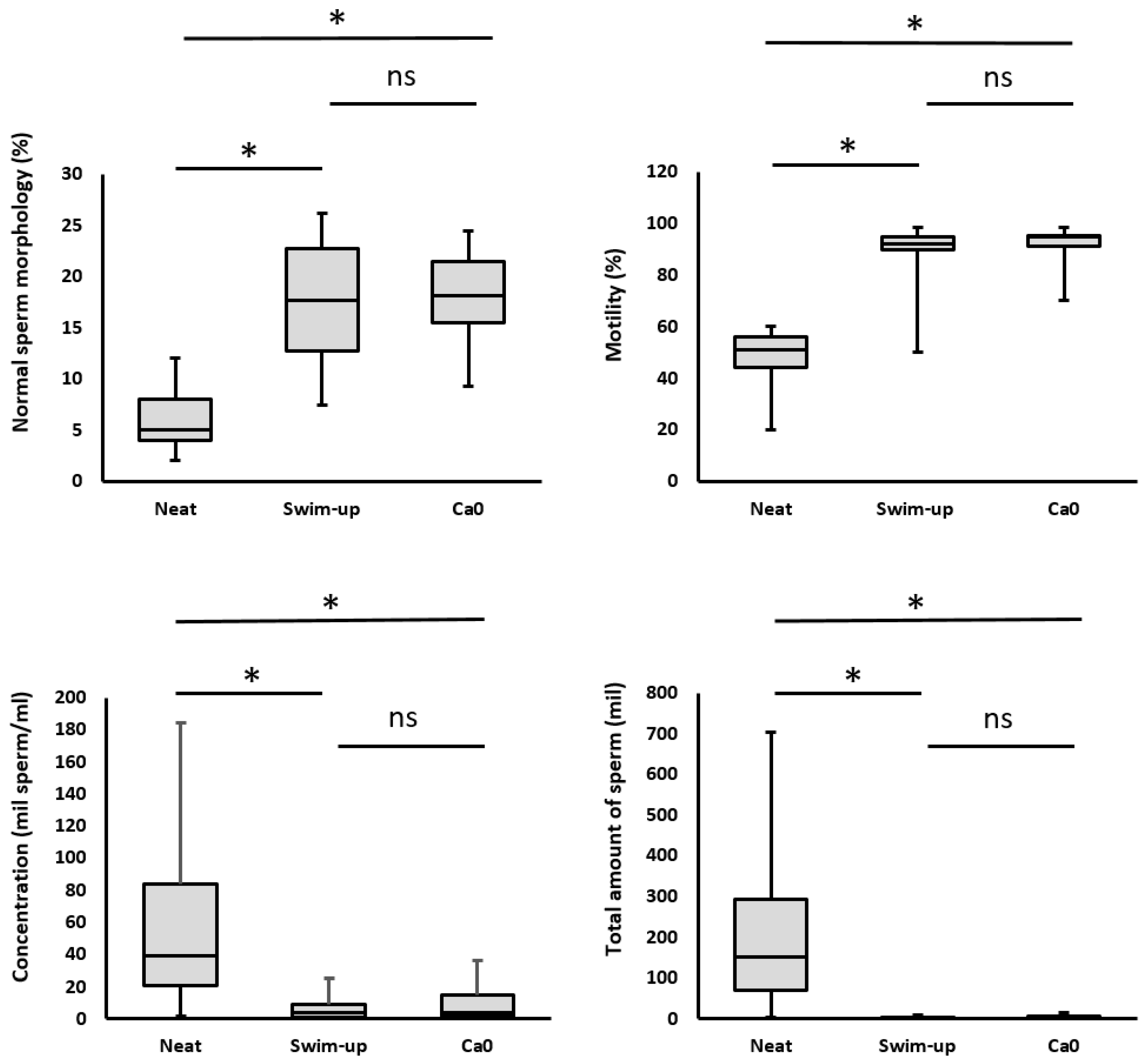

After both separations, there was a significant decrease in sperm concentration, an increase in motility, and an increase in the proportion of morphologically normal spermatozoa (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

2.2.1. Sperm Concentration

Sperm concentration is an important parameter; however, it is not decisive. What is important is the efficiency of the separation systems; therefore, at the end of the separation, we achieved sufficient sperm for IVF, even in patients who have a low concentration of sperm in the native ejaculate. The average sperm concentration of patients before separations was 46.3 mil/ml. After separation, the sperm concentration decreased significantly, to 6.3 mil/ml (for the swim-up method) and to 8.68 mil/ml (for the Ca0 method) (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

2.2.2. Total Amount of Spermatozoa

The total amount of spermatozoa in the ejaculate and the total amount of spermatozoa obtained after separation is a rather important parameter. Total sperm count before separation was 180.59 mil. During separation, the sperm count decreased significantly, to values of 4.0 mil/ml (for the swim-up method; 1:45) and to 2.9 mil/ml (for the MFSS method; 1:62) (

Table 2,

Figure 1). However, these values are sufficient for a successful IVF course.

2.2.3. Sperm Motility

Sperm motility indicates the efficiency of sperm separation and is a useful parameter for verifying the efficiency of sperm selection. High motility is evidence that the separation works well, and no dead or damaged sperm enter the sample. Sperm motility was quantified as the sum of progressive and non-progressive spermatozoa and was expressed as a percentage. Progressive motility refers to sperm cells that actively move in either a straight line or a wide circular pattern, regardless of their velocity. Nonprogressive motility encompasses all other movement patterns that lack forward progression. The total motility significantly increased from 51.11% (before separation) to 89.71% after separation using the swim-up method and to 92.84% in the MFSS method. There were no statistically significant differences between the separation techniques (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

2.2.4. Morphology of Sperm

Due to the intensive selection during separation the sperm morphology was logically improved. At the beginning before separation, the proportion of sperm with normal morphology was 5.13%, but after separation it increased statistically significantly to 17.23% (swim-up) and 18.48% (Ca0). There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of sperm with normal morphology between separation methods (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

2.2.5. DNA Integrity

The integrity of DNA, which is not typically assessed in a spermiogram, is crucial mainly for oocyte fertilization and subsequent embryonic development. Currently, DNA integrity disorders are considered to be one of the most prevalent causes of idiopathic infertility. After separation using the swim-up method, this parameter was significantly reduced by DFI 38 on average (to a DFI value of 11.43). After processing using the MFSS, the DFI value was 6.69.

Thus, there was a statistically significant reduction in the DFI value not only compared to the unprocessed ejaculate, but also compared to the swim-up method. There was statistically significant decreasing of DFI value after MFFS separation contrary to swim-up separation.

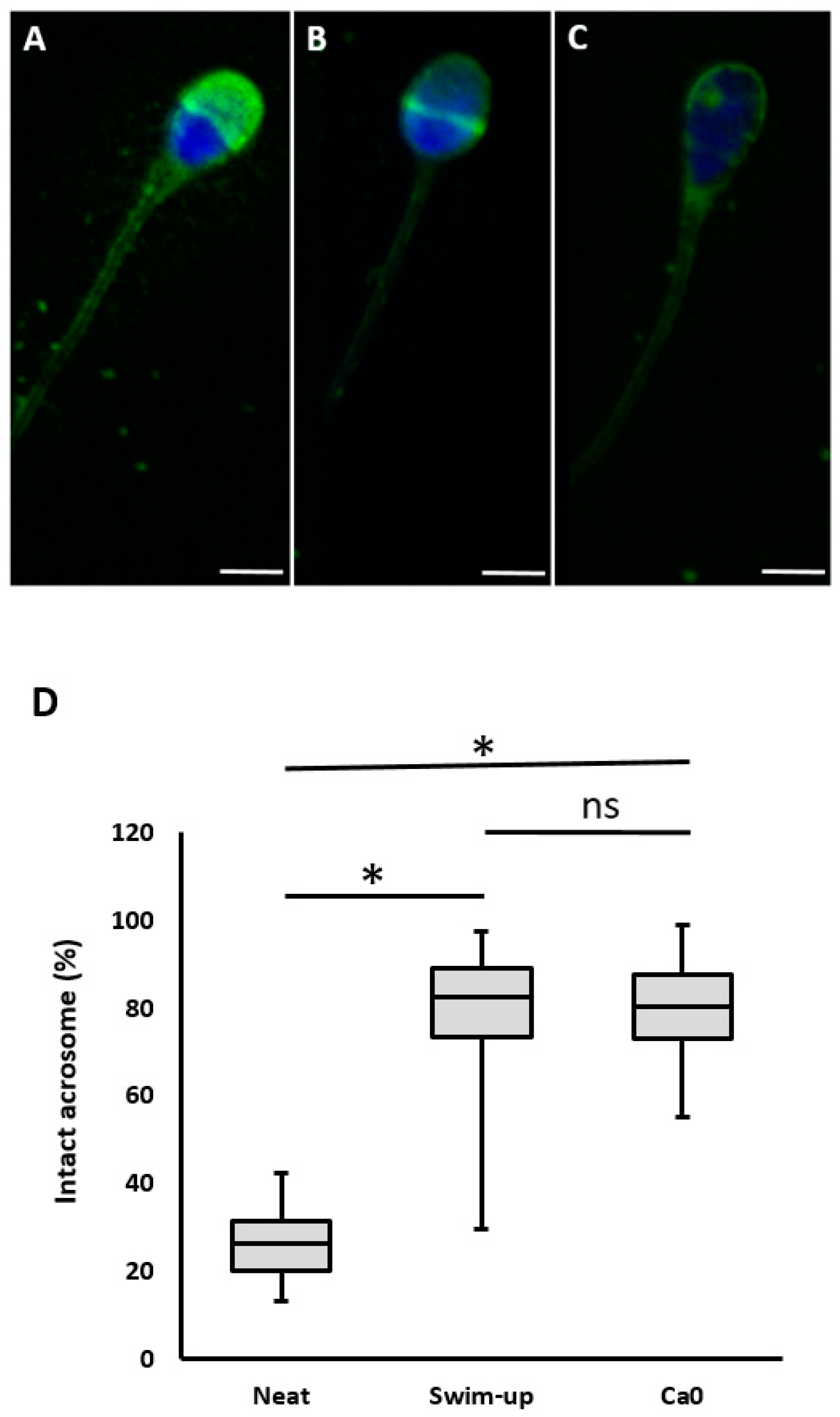

2.2.6. Acrosomal Status

The effect of sperm selection on the acrosomal status were shown in

Table 2. The percentage of sperm with intact acrosome was low before separation at 26.8% and significantly increased after separation at 79.07% (swim-up) and 79.72% (MFSS). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of sperm with intact acrosome between separation methods.

2.2.7. Mitochondrial Activity

The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) status after sperm selection were shown in

Table 2. The percentage of MMP in spermatozoa before separation was 87,56% and significantly increased after sperm selection in swim-up (93.43%) and MFSS device (93.37 ± 1.81) compared to the nonselected group (p:0.02 and p:0.02 respectively). There were no significant differences in terms of MMP in spermatozoa selected by swim-up and MFSS device (

Table 2).

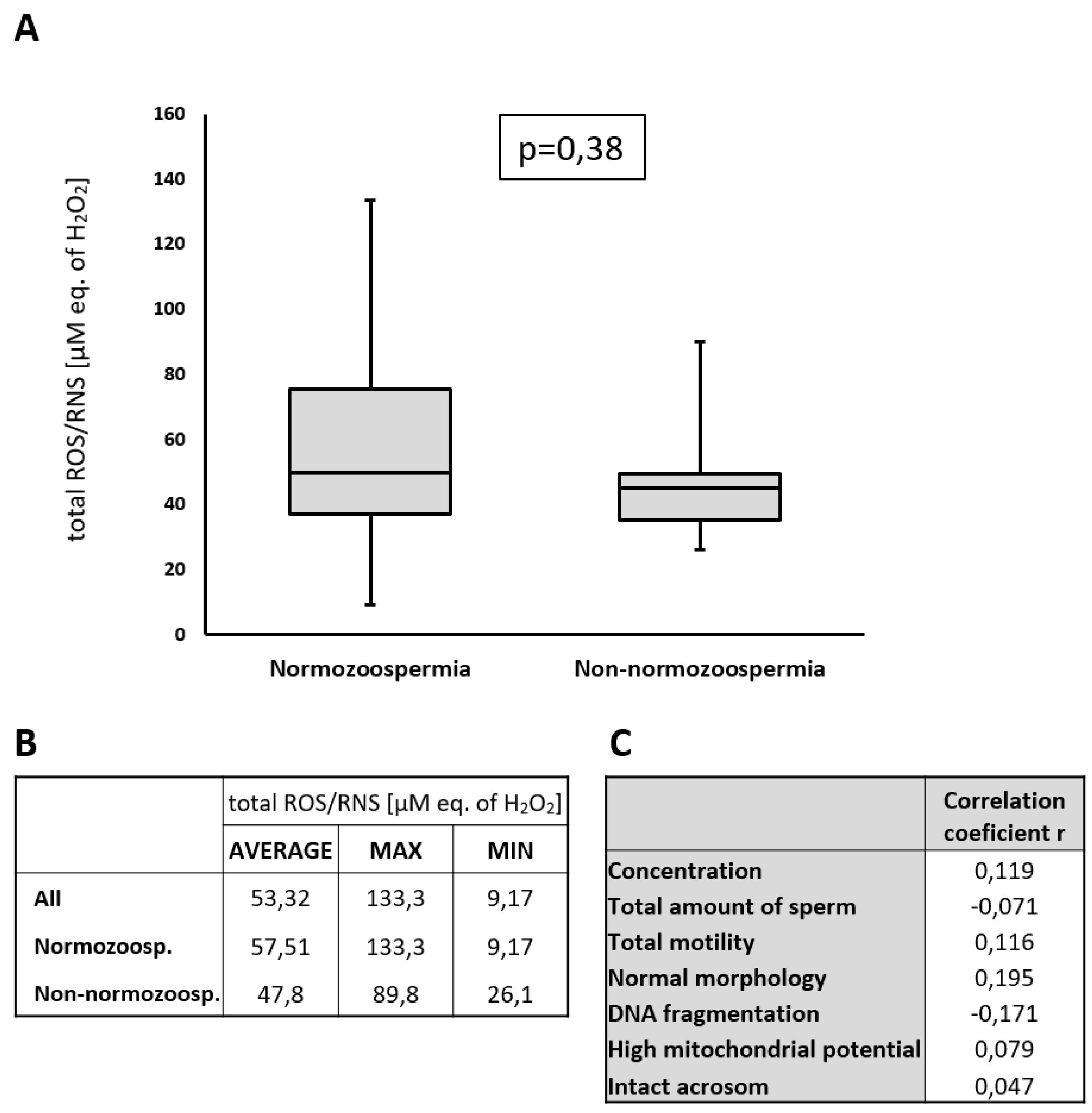

2.3. Detection of ROS/RNS in Seminal Plasma

It was previously described that H

2O

2 (one of the most important member of ROS family) decreases sperm viability, sperm kinetics, ability to penetrate cervical mucus, membrane integrity, and capacitation, but this negative effect was observed only at concentrations above 200 µM. Concentrations of H

2O

2 below 200 µM H

2O

2 do not have a significant negative effect on sperm [

18]. In our cohort, we detected total reactive oxygen/nitrogen species ROS/RNS H

2O

2 levels (including H

2O

2 as the main component of ROS) and found that these levels averaged at 53.32 µM (equivalent of H

2O

2, which served as a standard for total ROS/RNS determination) with a maximum value of 133.3 µM (eq. of H

2O

2) (

Figure 2). These values are well below the reported level of 200 µM of H

2O

2. It is true that the samples were collected and frozen after 60 min of ejaculation and that during liquefaction the H

2O

2 ROS/RNS concentration in the sample decreases (

Table S2). This value decreased to 73.5% of the original value 60 min after ejaculation (

Table S2). Thus, even taking this into account, the predicted ROS/RNS value for the patient with the highest value (133.3 µM of H

2O

2 eq.) would be probably around 181.3 µM after ejaculation which is still below the 200 µM threshold.

2.4. Normozoospermic and Non-Normozoospermic Patients

Based on our previous experiences and recent articles [

19], we compare the effectiveness of separation approaches in normozoospermic patients (n=25) and all others who do not reach the normal values (n=20). This group includes 6 asthenozoospermic, 4 oligoasthenoteratozoospermic, 3 teratozoospermic, 2 oligoteratozoospermic, 2 oligoasthenozoospermic, 2 oligozoospermic and 1 asthenoteratozoospermic patient. In normozoospermic patients we found no statistically significant differences between separation technics in analysed parameters (

Table 3).

In the non-normozoospermic group it was similar, but we found statistically significant differences in the proportion of spermatozoa with fragmented DNA between separations. After MFSS separation the proportion of sperm with fragmented DNA was significantly lower than after the swim-up method (

Table 4).

3. Discussion

In this study, we compared the effectiveness of the swim-up and Ca0 separation in normozoospermic and non-normozoospermic patients. In all patients, we monitored the oxygen radical concentration before their inclusion in the study, in order to exclude a negative effect of ROS on the observed ejaculate parameters. It is known that high concentrations of ROS in seminal plasma can damage sperm, increasing the proportion of sperm with fragmented DNA [

20,

21]. However, we detected only low levels of ROS, which should not have a significant impact on sperm.

We found that the sperm concentration decreased significantly after separation but without differences between MFSS and swim-up. In total amount of spermatozoa we did not find differences between methods. As expected, we also found a significantly higher proportion of motile sperm after MFSS compared to raw ejaculate, but not significant in comparing MFSS to the swim-up method in total motility. Differences in motility after separation are strongly dependent on the way the swim-up method is performed, where the difference in motility between swim-up and MFSS can be significant [

22] or minimal [

12] as in our study. Both methods showed improved proportion of sperm with normal morphology compared to raw semen, but was not detect significant difference between MFSS and swim-up, this results are consistent with previous study [

12]. Contrary to the study [

16], where was compared density gradient and MFSS system and was found significantly higher proportion of normal spermatozoa in MFSS group.

We detected significantly better DNA fragmentation after separation using MFSS. Separation by MFSS is very strict, there is probably an inverse relationship between DFI and motility. Separation of spermatozoa by MFSS enhanced the production of spermatozoa without DNA fragmentation, finally resulting in the production of healthier embryos [

23]. It was reported that MFSS strongly reduces the proportion of spermatozoa with fragmented DNA contrary to density gradient [

13,

24] or swim-up [

25].

In our results separation by MFSS (Ca0) significantly improved the proportion of spermatozoa with nonfragmented DNA but this trend was detected only in non-normozoospermic patients. In normozoospermic patients we found no significant differences between MFSS and swim-up method. In accordance with our results it was presented that Ca0 separation contrary to the swim-up method significantly reduce the embryo aneuploidy not in normozoospermic but only in non-normozoospermic patients [

2]. In a study focused on MFSS and swim-up separation it was detected very similar results in fertilizing potential and also DNA fragmentation between normozoospermic and non-normozoospermic patients [

14]. While gentle centrifugation has little effect on normal sperm samples, semen specimens with abnormalities seem to be more susceptible to mechanical stress and DNA damage [

26,

27]. This observation may account for our finding that the centrifugation-free Ca0 technique reduces fragmentation rates, especially when processing semen samples that deviate from normal parameters.

Successful fertilisation of the egg requires motile sperm with intact acrosomes that are able to undergo an acrosomal reaction before entering the egg [

28]. In this study, the percentage of sperm with intact acrosome was the similar for both methods of separation. However, there was significantly higher proportion of intact sperm after both separations compared to the pre-separation condition. The values presented are high compared to older studies [

29].

In this study, we assessed MMPs using the fluorescent marker JC-1.Mitochondria function as sources of ATP in the midpiece of the sperm flagellum, producing and transporting energy for sperm motility. In the present study, the percentage of spermatozoa selected by the MFSS method was the same as in the separated swim-up group. The MMP was lower in the native ejaculate than in the separated groups. Sperm mitochondrial activity correlates well with sperm motility, and our findings are also consistent with reports on the positive correlation between progressive motility and sperm MMP [

30].

In all patients, we detected the levels of oxygen radicals in seminal plasma before separation. The reason was to exclude oxidative stress, which can significantly affect the condition of spermatozoa. High levels of ROS can damage sperm membranes, impair sperm motility [

31] and are also thought to be one of the causes of high sperm DNA fragmentation [

20,

21]. We detected values in the range of 8-133 µM, all of which are below the 200 uM ROS threshold [

18]. Moreover, when we performed a correlation analysis, there was no direct correlation between the observed parameters and the detected ROS values due to low ROS concentrations (

Figure 2C). From these results, we concluded that the observed spermiogram parameters in this study were not affected by the concentration of ROS in seminal plasma.

In analyses of comparison standard sperm selection method and MFSS separation was found very good results [

13,

22,

24], but also only marginal positive results without significant differences which was presented in recent meta analyses [

32]. In our study we found positive effect on DNA fragmentation after using of MFSS system, but only in non-normozoospermic patients. The limitation for Ca0 is also the overall lower amount of sperm obtained after separation, which is due to the limit for the maximum amount of ejaculate separated (0.9 ml). In normozoospermic patients this is not a problem but in patients with low volume and low concentration it can be a problem and therefore it is necessary to proceed individually when choosing the method and keep this fact in mind when deciding which separation system to use. Although microfluidic separations are considered the future of sperm selection in assisted reproduction, their development has been stagnant for two decades [

33]. However, in recent years, the MFSS and similar lab-on-chip systems has begun to be increasingly promoted in clinical embryology and these systems are the future in the field of sperm separation.

4. Materials and Methods

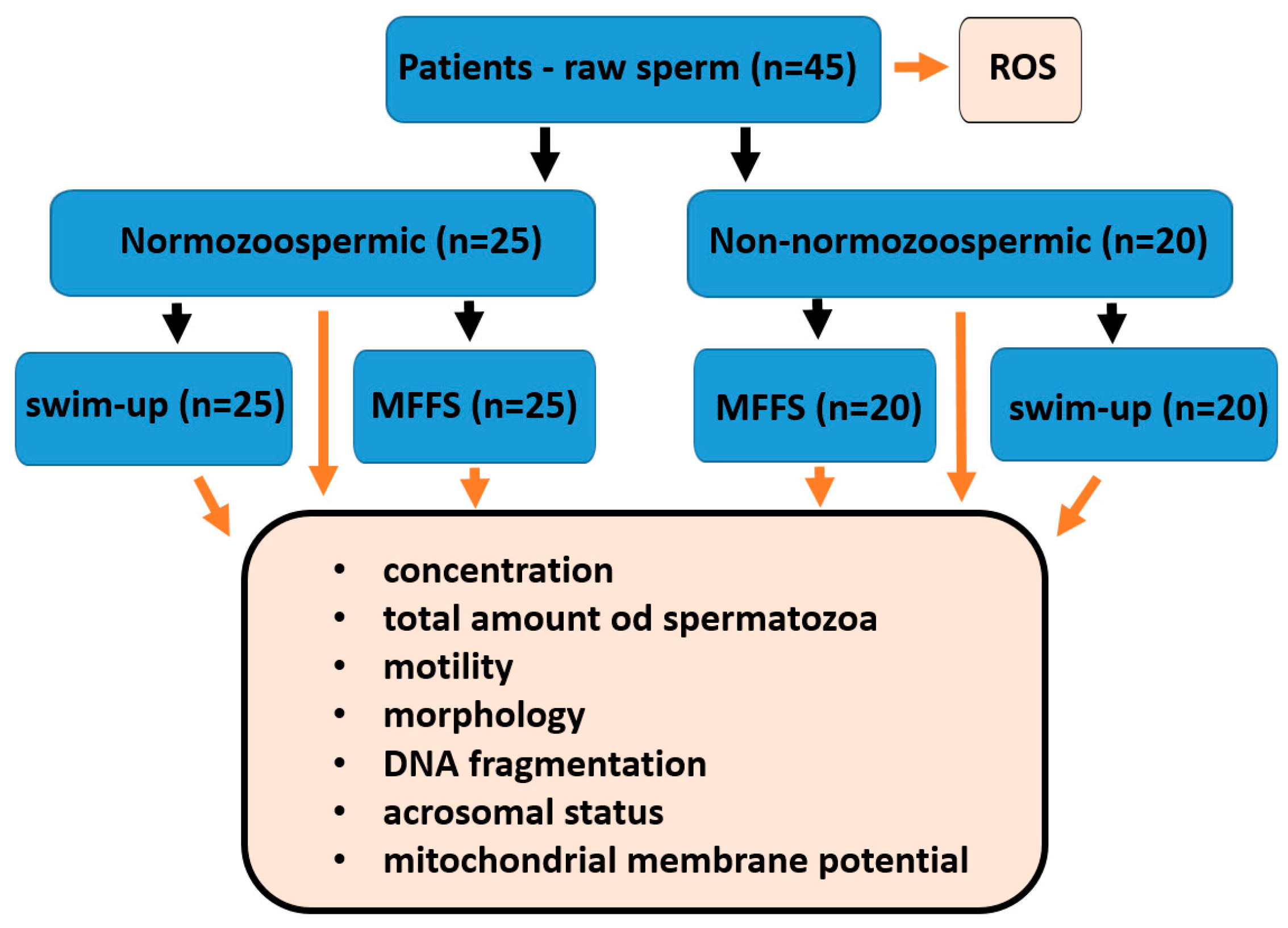

4.1. Patients

The study was approved by the ethics committee of University Hospital Brno. All the patients enrolled in this study consented to participate and signed an informed consent form. A total of 45 patients from the CERMED center aged 21-47 years with an ejaculate volume greater than 1.6 ml were enrolled in the study. The semen specimens were obtained following an abstinence period of 2–5 days and collected in sterile containers via masturbation. Liquefaction of the samples occurred at room temperature within 30 minutes. There were 25 normozoospermic patients and 20 non-normozoospermic patients based on primary semen analysis. Patients were classified as having normal or abnormal sperm parameters according to World Health Organization manual [

34]. For each patient, the ejaculate was separated into three parts after liquefaction (60 min after ejaculation): the 1st part of the ejaculate (0.2 ml) was not separated and only analysed, the 2nd part (900 µL of ejaculate) was separated using a Ca0 microfluidic chip (LensHOOKE Bonraybio, Taichung, Taiwan), and the 3rd part (the rest of the ejaculate; ≥500 µL) was processed using the swim-up method (

Figure 3).

4.2. Sperm Selection

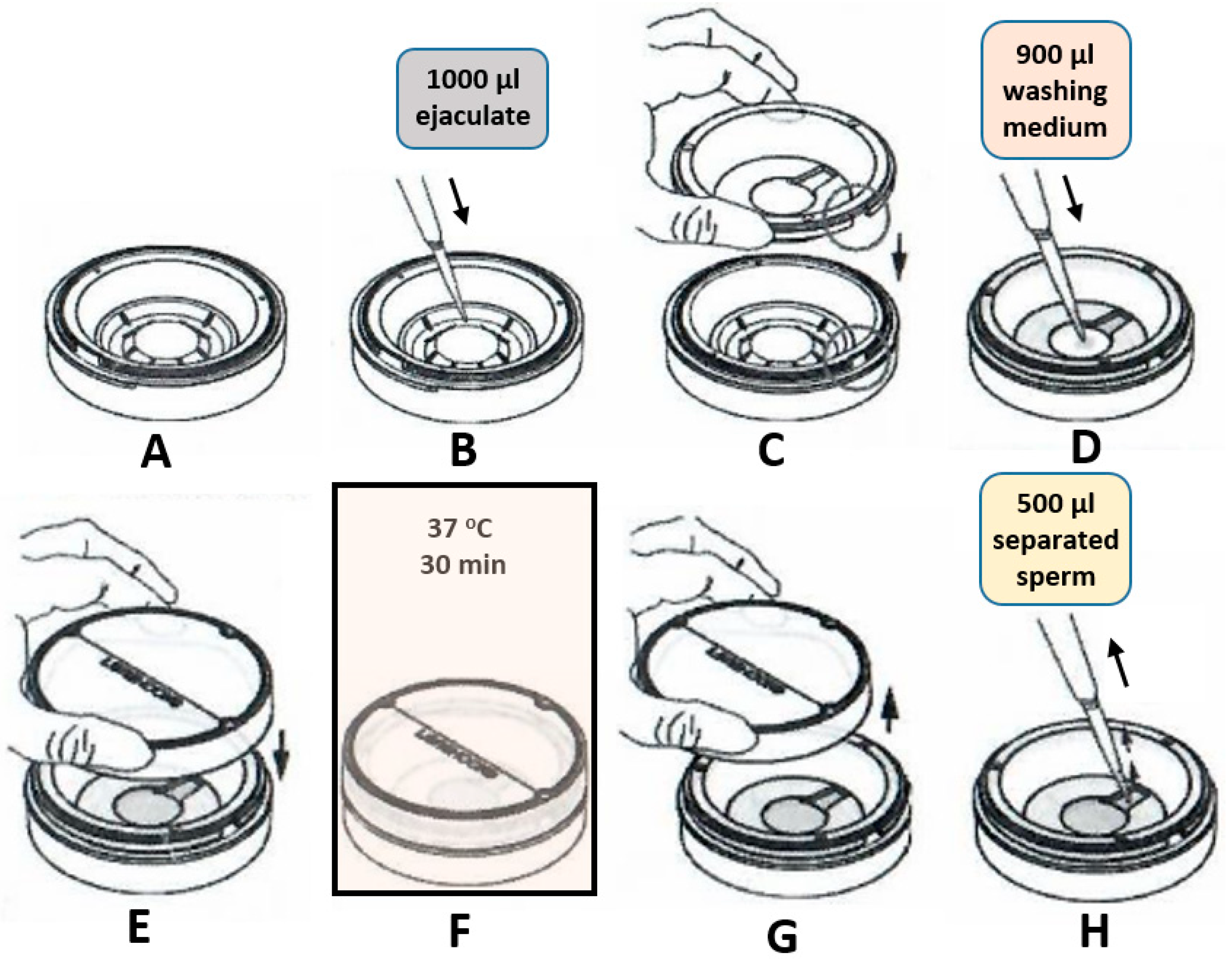

4.2.1. Microfluidic Sperm Selection

Microfluidic sperm sorting was conducted utilizing a commercial Ca0 device (LensHOOKE., Bonraybio, Taichung, Taiwan) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 1000 μL of neat semen was filled into the lower chamber. 900 μL of Sperm Preparation Medium (Origio, Denmark) was added into the upper chamber and covered by cover piece. The device was then placed in a humidified incubator at 37℃ for a duration of 30 minutes. Following the incubation period, 500 μL of sperm suspension was extracted from the upper chamber for subsequent analysis (

Figure 4).

4.2.2. Swim-Up Method

Semen samples were pipetted into 15 ml conical centrifuge tubes and washed twice in 2 ml Sperm Preparation Medium (Origio, Denmark) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Following the second wash, 1000 µL Universal IVF medium (Origio, Denmark) was gently overlaid onto the spermatozoa. The tube was then inclined at an angle of approximately 45° to increase the surface area of the semen-culture medium interface and subsequently incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Following this incubation period, only 400 µL from the surface were collected for analysis.

4.3. Semen Analyses

Each patient underwent spermiogram analysis in accordance with the World Health Organization laboratory manual. The volume was determined using gravimetric measurements. Following the liquefaction of the ejaculate, a comprehensive spermiogram analysis was conducted for each sample. In this study, we focused on five semen quality parameters: ejaculate volume, sperm concentration, progressive motility, the percentage of sperm with normal morphology, and total sperm count (volume × sperm concentration). Subsequently, after separation, basic spermiogram parameters (concentration, motility, and morphology) and sperm DNA integrity, acrosomal status and mitochondrial membrane potential were evaluated for all three samples.

To evaluate the effect of sperm selection on morphology, Diff-Quik (MICROPTIC SL Co., Spain) staining was employed [

35]. The procedures followed WHO guidelines. A thin, uniform layer of approximately 10 μL of spermatozoa was spread on a clean glass slide and allowed to air-dry at room temperature for a minimum of 30 min. The slides were stained according to the manual’s recommended procedure and examined under a bright-field microscope. For each sample, 200 spermatozoa were categorized based on morphology, including normal and abnormal heads, middle pieces and tails. The proportion of normal spermatozoa was calculated and expressed as a percentage.

4.4. DNA Integrity Assessment

Sperm DNA fragmentation was assessed using the sperm chromatin dispersion test (Halosperm G2 kit, Halotech, Spain), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Intense staining was used to visualize the periphery of the dispersed DNA-loop halos. Spermatozoa exhibiting large and medium halos were classified as non-fragmented, whereas those displaying small halos, no halos, or degeneration were categorized as fragmented. The proportion of spermatozoa with fragmented DNA (expressed as the DNA fragmentation index) was evaluated. The DNA fragmentation index (DFI) was calculated using the following formula: DFI (%) = (fragmented spermatozoa + degenerated spermatozoa / total spermatozoa counted) × 100. For this study, a minimum of 600 spermatozoa per sample were evaluated under the 100× objective of the microscope. To mitigate potential bias, at least 300 spermatozoa were analyzed by two independent technicians. The DFI value of the unprocessed samples was used as the starting point for calculating the relative separation efficiency.

4.5. Evaluation of Acrosomal Status

Lectin peanut agglutinine labeled fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC-PNA) was used to assess the acrosomal condition of sperm cells. Droplets of sperm samples (5 μl) were air-dried on slides. The slides were then fixed in ice-cold ethanol, dried, and coated with FITC-PSA (Sigma Adrich, Germany) before being kept in the dark for 30 min. Samples were mounted under Vectashield medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, USA). After thorough washing in PBS (Sigma Aldrich, Germany), the coverslips were applied. A fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ts2, Nikon, Japan) was used to examine the fluorescence patterns of 200 sperm cells from random areas at x1000 magnification. Acrosomal status was categorized using three distinct lectin staining patterns: 1) complete acrosome staining, indicating an intact acrosome; 2) partial acrosome staining, signifying sperm with disturbed acrosome; and 3) no staining of the entire sperm head, indicating a sperm with detached acrosome (

Figure 5). The percentage of various lectin reaction patterns among the total counted sperm cells was recorded [

36].

4.6. Mitochondrial Evaluation

The assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was conducted using JC-1, a lipophilic cationic dye [

37]. Following the manufacturer’s guidelines (cat #10009172; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MC, USA), a JC-1-staining working solution was prepared by diluting the stock solution 1:10 (v/v) in the culture medium. For each evaluation, 1 μL of JC-1 working solution was combined with 9 μl of sperm suspension and incubated for 30 min in a humidified environment (37°C, 5% CO

2) away from light. Mitochondrial activity was observed using a fluorescence microscope at 1000 × magnification under a coverslip with immersion oil (Nikon ECLIPSE Ts20, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The MMP status was determined by examining the fluorescence pattern of 200 spermatozoa in randomly chosen areas on each slide. Spermatozoa with a high MMP (active mitochondria) exhibit orange-red fluorescence [

38]. The results are expressed as the percentage of cells displaying a high MMP.

4.7. ROS/RNS Assessment

The concentration of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS; including hydrogen peroxide as one of the primary reactive oxygen species present in semen) in semen sam-ples was quantified using a commercially available assay kit. The total quantity of ROS/RNS was determined using the OxiSelect™ In Vitro ROS/RNS Assay Kit (Cell Bi-olabs, San Diego, CA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The fluorescence signal was measured using a Fluostar Omega Microplate Reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) at an excitation wavelength of 485/20 nm and an emission wave-length of 528/20 nm. The level of ROS/RNS in the ejaculate gradually decreases, which was verified in a separate experiment (

Figure S1). For this reason, immediately after liquefaction the samples must be frozen in liquid nitrogen at -196°C. When ejaculate is stored at -20 °C, a rapid decrease in ROS/RNS levels occurs after storage (

Table S2).

4.8. Statistical Evaluation

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA CZ software, version 10 (StatSoft, Inc., Prague, Czech Republic). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons of numeric variables between groups were performed utilizing one-way analysis of variance. Differences were considered statistically significant at P< 0.05.

5. Conclusions

The tested Ca0 method is practical, easy to manipulate and reliable. Its use is advantageous in many ways for the laboratory and the patient. However, when individual sperm parameters are carefully compared, except in non-normozoospermic patients, it does not provide much benefit over the swim-up method. In the case of patients who do not have a normal spermiogram and have other problems (such as a higher proportion of sperm with fragmented DNA), this method has merit and can significantly improve the efficiency of infertility treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Stability of ROS values during storage; Table S2: Comparison of the stability of ROS in ejaculate before the sperm separation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and L.M.; methodology, M.J. and A.D.; validation, L.M.; J.A. and B.K..; formal analysis, R.H. and B.K.; investigation, J.H.; A.D.; J.M. and L.M.; data curation, M.J. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.; J.A. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, B.K., J.A.; K.R. and L.M..; supervision, M.J.; project administration, M.J.; funding acquisition, M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MSMT INTER-COST LUC 23009), Czech ministry of Health (MH CZ - DRO FNBr 65269705), project Andronet - COST CA20119 and Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences (VEGA-2/0074/24).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL BRNO (protocol code 11-110123/EK from 11.1.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data and material used in this research are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Vaughan, D. A., Leung, A., Resetkova, N., Ruthazer, R., Penzias, A. S., Sakkas, D., and Alper, M. M. How many oocytes are optimal to achieve multiple live births with one stimulation cycle? The one-and-done approach. Fertil Steril 2017, 107 (2):397-404.e3. [CrossRef]

- Giojalas, L. C., and Guidobaldi, H. A. Getting to and away from the egg, an interplay between several sperm transport mechanisms and a complex oviduct physiology. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020, 518:110954. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M., Thompson, L. A., Li, T. C., Mackenna, A., Barratt, C. L., and Cooke, I. D. Uterine flushing: a method to recover spermatozoa and leukocytes. Hum Reprod 1993, 8 (6):925-8. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, D., Leslie, E. E., Kelly, R. W., and Templeton, A. A. Morphological selection of human spermatozoa in vivo and in vitro. J Reprod Fertil 1982, 64 (2):391-9. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cerezales, S., Ramos-Ibeas, P., Acuña, O. S., Avilés, M., Coy, P., Rizos, D., and Gutiérrez-Adán, A. The oviduct: from sperm selection to the epigenetic landscape of the embryo. Biol Reprod 2018, 98 (3):262-276. [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, D., Ramalingam, M., Garrido, N., and Barratt C. L. Sperm selection in natural conception: what can we learn from mother nature to improve assisted reproduction outcomes? Hum Reprod Update 2015, 21 (6):711-26. [CrossRef]

- Baldini, D., Ferri, D., Baldini, G. M., Lot D., Catino, A., Vizziello, D., and Vizziello, G. Sperm selection for ICSI: Do we have a winner? Cells 2021, 10 (12). [CrossRef]

- Henkel, R. Sperm preparation: state-of-the-art-physiological aspects and application of advanced sperm preparation methods. Asian J Androl 2012, 14 (2):260-9. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C., Zhang, Z., Shan, G., Chu, L. T., Huang, Z., Moskovtsev, S., Librach, C., Jarvi, K., and Sun, Y. Advances in sperm analysis: techniques, discoveries and applications. Nat Rev Urol 2021, 18 (8):447-467. [CrossRef]

- Gandini, L., Lombardo, F., Paoli, D., Caruso, F., Eleuteri, P., Leter, G., Ciriminna, R., Culasso, F., Dondero, F., Lenzi, A., and Spanò, M. Full-term pregnancies achieved with ICSI despite high levels of sperm chromatin damage. Hum Reprod 2004, 19 (6):1409-17. [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, D., and Alvarez, J. G. Sperm DNA fragmentation: mechanisms of origin, impact on reproductive outcome, and analysis. Fertil Steril 2010, 93 (4):1027-36. [CrossRef]

- Gotsiridze, K., Nana, M., Mariam, M. and Tamar, J. Live motile sperm sorting device improves embryo aneuploidy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Fertility & Reproduction 2024, 06 (03):117-122. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M. M., Jalalian, L., Ribeiro, S., Ona, K., Demirci, U., Cedars, M. I., and Rosen, M. P. Microfluidic sorting selects sperm for clinical use with reduced DNA damage compared to density gradient centrifugation with swim-up in split semen samples. Hum Reprod 2018, 33 (8):1388-1393. [CrossRef]

- Sheibak, N., Amjadi, F., Shamloo, A., Zarei, F., and Zandieh, Z. Microfluidic sperm sorting selects a subpopulation of high-quality sperm with a higher potential for fertilization. Hum Reprod 2024, 39 (5):902-911. [CrossRef]

- Banti, M., Van Zyl, E., and Kafetzis, D. Suprem preparation with microfluidic sperm sorting chip may improve intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes compared to density gradient centrifugation. Reprod Sci 2024, 31 (6):1695-1704. [CrossRef]

- Anbari, F., Khalili, M. A., Sultan Ahamed, A. M., Mangoli, E., Nabi, A., Dehghanpour, F., and Sabour, M. Microfluidic sperm selection yields higher sperm quality compared to conventional method in ICSI program: A pilot study. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2021, 67 (2):137-143. [CrossRef]

- Feyzioglu, B. S., and Avul, Z. Effects of sperm separation methods before intrauterine insemination on pregnancy outcomes and live birth rates: Differences between the swim-up and microfluidic chip techniques. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102 (46):e36042. [CrossRef]

- Pujianto, D. A., Oktarina, M., Sharma Sharaswati, I. A., and Yulhasri. Hydrogen peroxide has adverse effects on human sperm quality parameters, induces apoptosis, and reduces survival. J Hum Reprod Sci 2021, 14 (2):121-128. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. T., Lee, C. I., Lin, F. S., Wang, F. Z., Chang, H. C., Wang, T. E., Huang, C. C., Tsao, H. M., Lee, M. S., and Agarwal, A. Live motile sperm sorting device for enhanced sperm-fertilization competency: comparative analysis with density-gradient centrifugation and microfluidic sperm sorting. J Assist Reprod Genet 2023, 40 (8):1855-1864. [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, S. W., Ara, A., Saharan, A., Jaffar, M., Gugnani, N., and Esteves, S. C. Sperm DNA fragmentation: causes, evaluation and management in male infertility. JBRA Assist Reprod 2024, 28 (2):306-319. [CrossRef]

- Wright, C., Milne, S., and Leeson, H. Sperm DNA damage caused by oxidative stress: modifiable clinical, lifestyle and nutritional factors in male infertility. Reprod Biomed Online 2014, 28 (6):684-703. [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, S. A., Ding, L., Parast, F. Y., Nosrati, R., and Warkiani. Sperm quality metrics were improved by a biomimetic microfluidic selection platform compared to swim-up methods. Microsyst Nanoeng 2023, 9:37. [CrossRef]

- Kocur, O. M., Xie P., Cheung, S., Souness, S., McKnight, M., Rosenwaks, Z., and Palermo, G. D. Can a sperm selection technique improve embryo ploidy? Andrology 2023, 11 (8):1605-1612. [CrossRef]

- Parrella, A., Keating, D., Cheung, S., Xie, P., Stewart, J. D., Rosenwaks, Z., and Palermo, G. D. A treatment approach for couples with disrupted sperm DNA integrity and recurrent ART failure. J Assist Reprod Genet 2019, 36 (10):2057-2066. [CrossRef]

- Shirota, K., Yotsumoto, F., Itoh, H., Obama, H., Hidaka, N., Nakajima, K., and Miyamoto, S. Separation efficiency of a microfluidic sperm sorter to minimize sperm DNA damage. Fertil Steril 2016, 105 (2):315-21.e1. [CrossRef]

- Muratori, M., Tarozzi, N., Cambi, M., Boni, L., Iorio, A. L., Passaro, C., Luppino, B., Nadalini, M., Marchiani, S., Tamburrino, L., Forti, G., Maggi, M., Baldi, E., and Borini, A. Variation of DNA fragmentation levels during density gradient sperm selection for assisted reproduction techniques: a possible new male predictive parameter of pregnancy? Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95 (20):e3624. [CrossRef]

- akeshima, T., Yumura, Y., Kuroda, S., Kawahara, T., Uemura, H., and Iwasaki, A.. Effect of density gradient centrifugation on reactive oxygen species in human semen. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2017, 63 (3):192-198. [CrossRef]

- Raad, G., Bakos, H. W., Bazzi, M., Mourad, Y., Fakih, F., Shayya, S., Mchantaf, L., and Fakih, C. Differential impact of four sperm preparation techniques on sperm motility, morphology, DNA fragmentation, acrosome status, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial activity: A prospective study. Andrology 2021, 9 (5):1549-1559. [CrossRef]

- Esteves, S. C., Sharma, R. K., Thomas, A. J., and Agarwal, A. Effect of swim-up sperm washing and subsequent capacitation on acrosome status and functional membrane integrity of normal sperm. Int J Fertil Womens Med 2000, 45 (5):335-341.

- Paoli, D., Gallo, M., Rizzo, F., Baldi, E., Francavilla, S., Lenzi, A., Lombardo, F., and Gandini, L. Mitochondrial membrane potential profile and its correlation with increasing sperm motility. Fertil Steril 2011, 95 (7):2315-2319. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A., Saleh, R.A. Role of oxidants in male infertility: rationale, significance, and treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2002,29(4):817-27. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Aderaldo, J., da Silva Maranhão, K., and Ferreira Lanza, D. C. Does microfluidic sperm selection improve clinical pregnancy and miscarriage outcomes in assisted reproductive treatments? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2023, 18 (11):e0292891. [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, A. R., Ziarati, N., Dadkhah, E., Bucak, M. N., Rahimizadeh, P., Shahverdi, A., Sadighi Gilani, M. A., and Topraggaleh, T. R. Microfluidics: The future of sperm selection in assisted reproduction. Andrology 2024, 12 (6):1236-1252. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2010. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Doostabadi, M. R., Mangoli, E., Marvast, L. D., Dehghanpour, F., Maleki, B., Torkashvand, H., and Talebi, A. R.. Microfluidic devices employing chemo- and thermotaxis for sperm selection can improve sperm parameters and function in patients with high DNA fragmentation. Andrologia 2022, 54 (11):e14623. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, C., Kharche, S. D., Mishra, A. K., Saraswat, S., Kumar, N., and Sikarwar A.K. Effect of diluent sugars on capacitation status and acrosome reaction of spermatozoa in buck semen at refrigerated temperature. Trop Anim Health Prod 2020, 52 (6):3409-3415. [CrossRef]

- Smiley, S. T., Reers, M., Mottola-Hartshorn, C., Lin, M., Chen, A., Smith, T. W., Steele, G. D., and Chen, L.B. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991, 88 (9):3671-3675. [CrossRef]

- Maleki, B., Khalili M. A., Gholizadeh L., Mangoli E., and Agha-Rahimi, A. Single sperm vitrification with permeable cryoprotectant-free medium is more effective in patients with severe oligozoospermia and azoospermia. Cryobiology 2022, 104:15-22. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).