Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- -

- determining the most beneficial location of semen collection (in-lab or outside the lab);

- -

- determining the most beneficial method of semen collection (masturbation or intercourse with a special condom);

- -

- determining the most beneficial sample delivery method to the laboratory (time since ejaculation, sample transport temperature);

- -

- determining the most beneficial time from semen collection to the start of analysis;

- -

- choice of appropriate container (plastic or glass container or special condom);

- -

- including any comments from the patient (verbal or written) upon sample delivery (e.g., loss of part of the sample during collection).

- -

- genetic defects in sperm that have not been previously considered;

- -

- incorrect positioning relative to the liquid nitrogen mirror, which can lead to either too slow or too rapid cooling of the sperm;

- -

- immersion of prepared sperm directly into liquid nitrogen without an equilibration step in nitrogen vapors;

- -

- failure to follow freezing protocols, including freezing times;

- -

- incorrect medium volume to sperm volume ratio;

- -

- failure to pre-warm the freezing medium;

- -

- incorrect method of adding cryoprotectants to the sperm;

- -

- omitting or shortening the sperm thawing time;

- -

- too long a delay before starting the freezing procedure (>2 hours);

- -

- too long a time spent transferring frozen sperm to the collection container;

- -

- failure to maintain a constant temperature for frozen sperm;

- -

- improper conditions of transportation of sperm to the laboratory;

- -

- lack of experience in personnel performing the freezing process, haste, or lack of precision;

- -

- expired reagents;

- -

- improper storage conditions for the medium;

- -

- improper transport of the medium from the supplier to the laboratory;

- -

- failure to maintain optimal conditions in the laboratory during sperm thawing.

Materials and Methods

- -

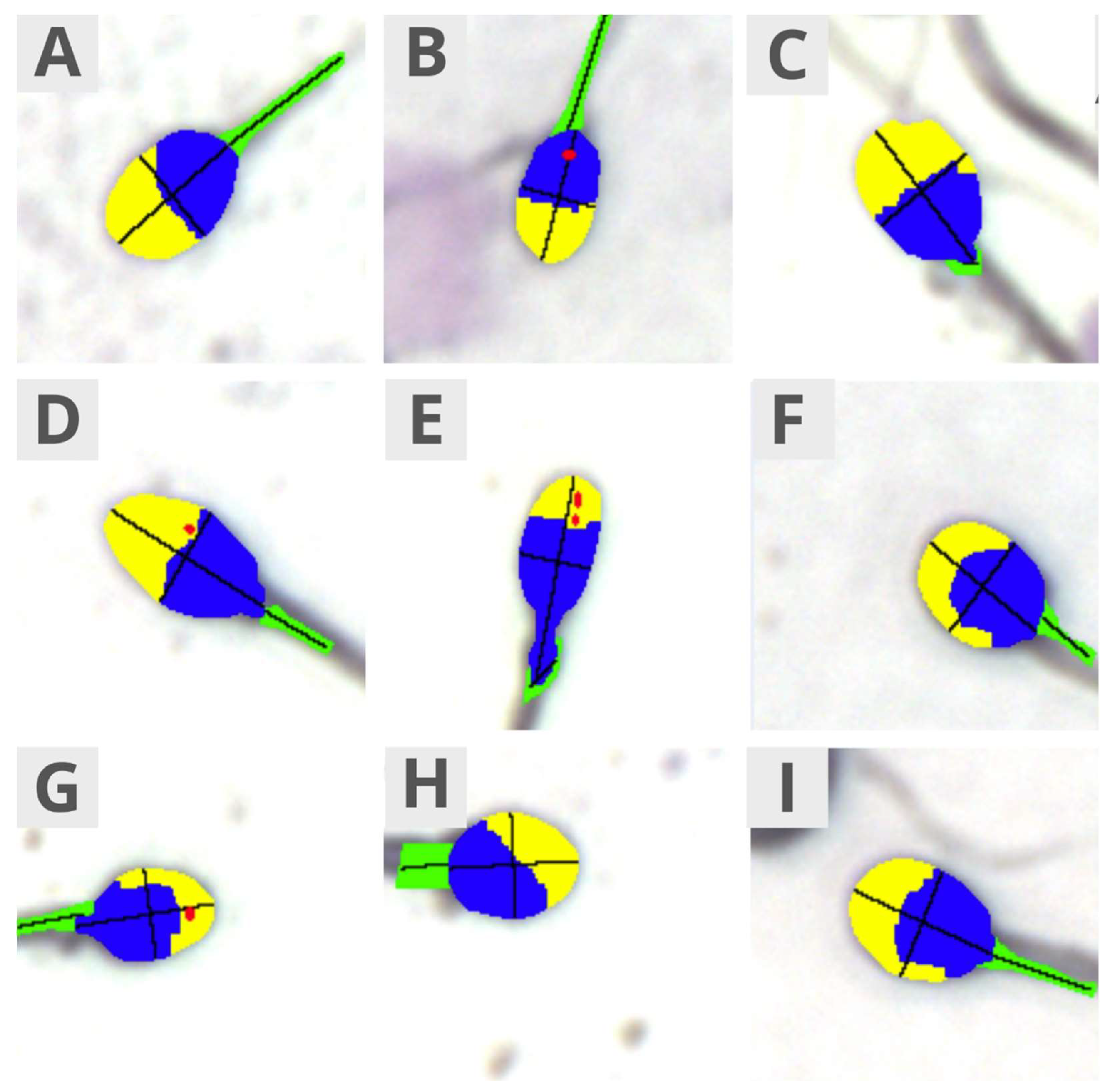

- Morphology: normal/abnormal sperm, Teratozoospermia Index, Sperm Deformation Index, and Multiple Anomalies Index;

- -

- Head size: normal, micro, and macro;

- -

- Head shape: normal, conical, thin, round, pear-shaped, and amorphous;

- -

- Acrosome: normal/abnormal;

- -

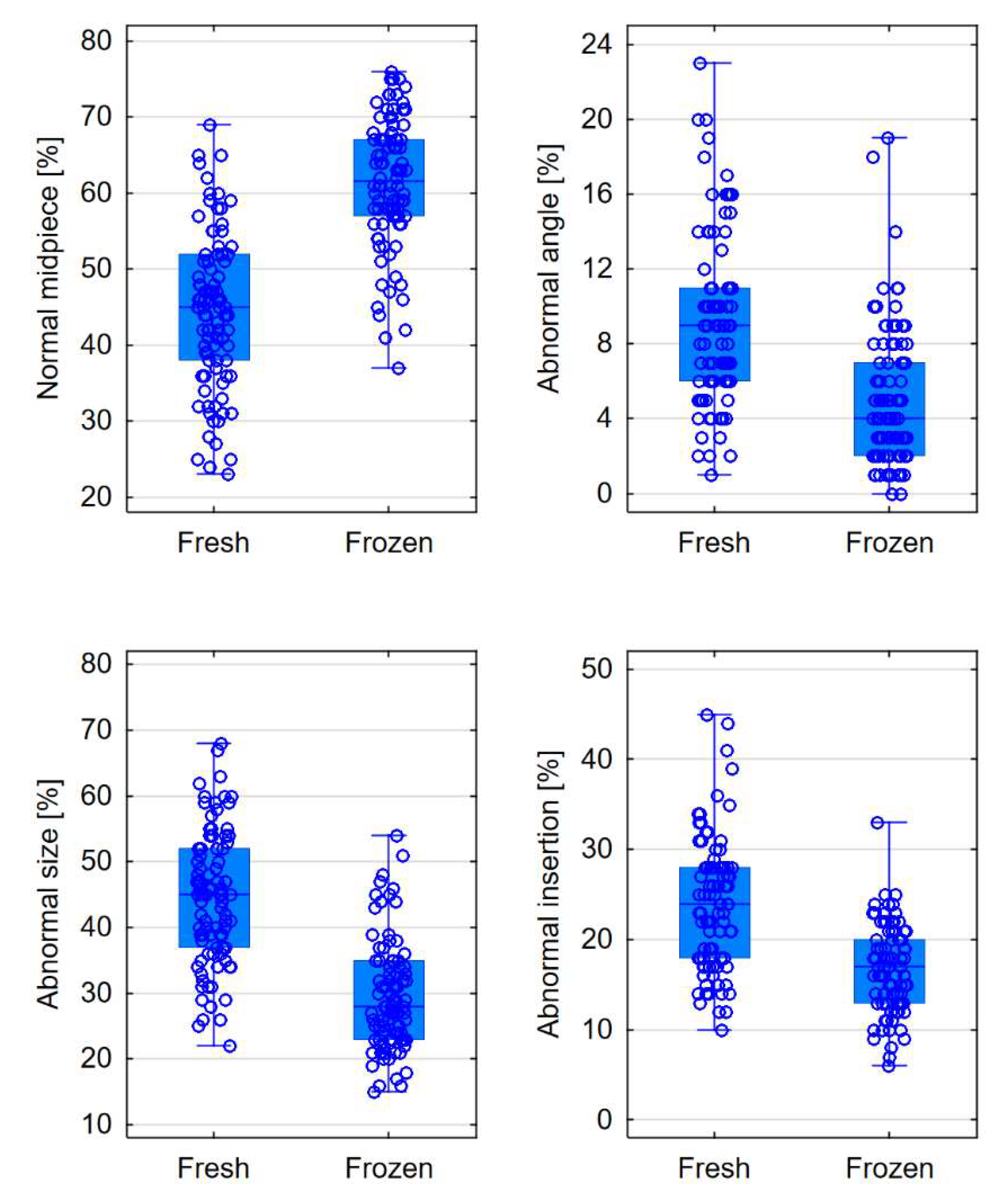

- Midpiece: normal, abnormal size, abnormal insertion, and abnormal angle;

- -

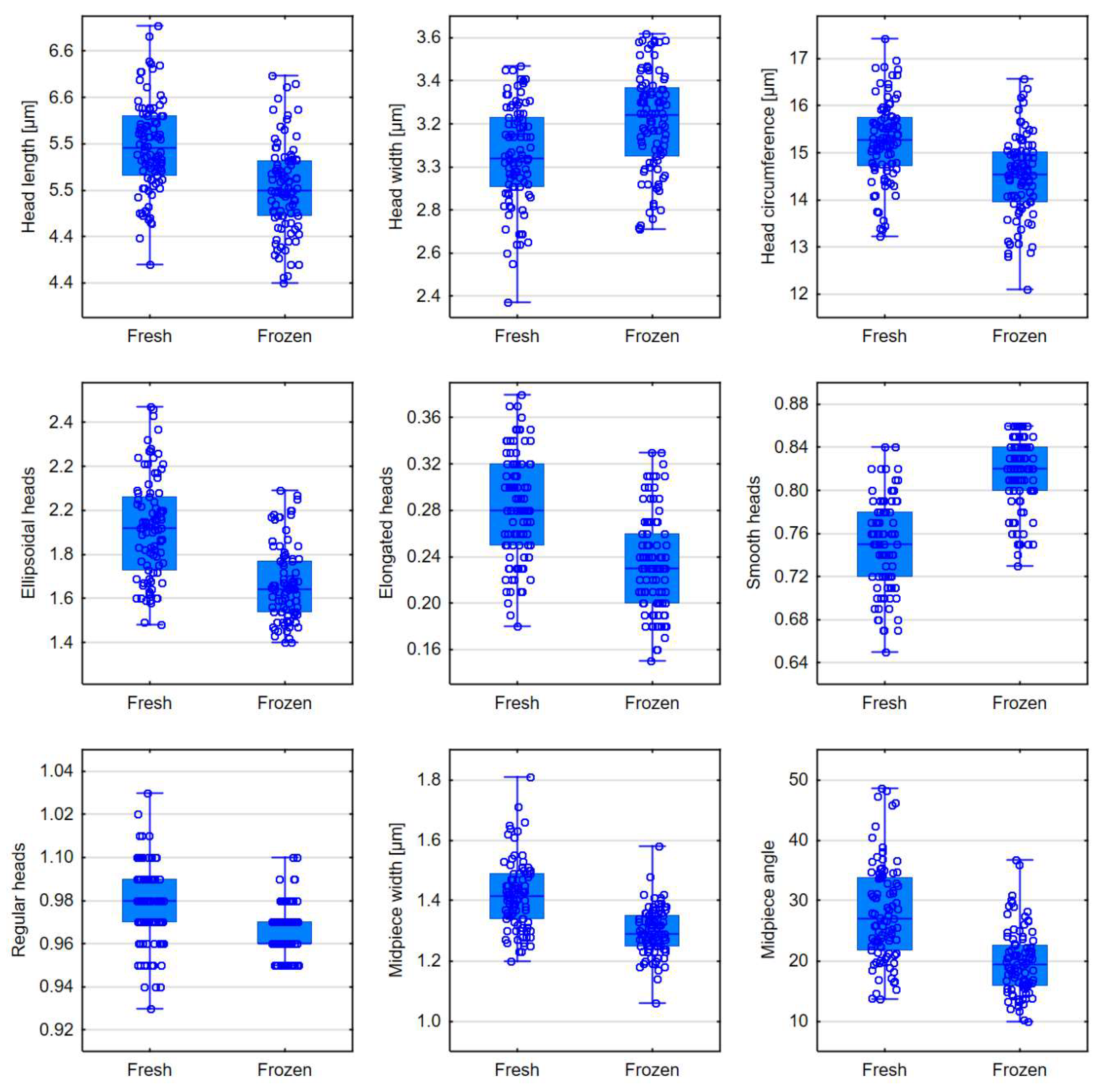

- Morphometrics: head length, head width, head area, head circumference, ellipsoidal heads, elongated heads, smooth heads, regular heads, midpiece width, midpiece area, midpiece angle, and acrosome-to-head ratio.

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, A.; Mulgund, A.; Hamada, A.; Chyatte, M.R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2015, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zańko, A.; Martynowicz, I.; Citko, A.; Konopka, P.; Paszko, A.; Pawłowski, M.; Szczerbiński, Ł.; Siewko, K.; Krętowski, A.J.; Kuczyński, W.; Milewski, R. The Influence of Lifestyle on Male Fertility in the Context of Insulin Resistance—Identification of Factors That Influence Semen Quality. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocuzza, M.; Alvarenga, C.; Pagani, R. The epidemiology and etiology of azoospermia. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013, 68, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, C.L.R. Semen analysis is the cornerstone of investigation for male infertility. Practitioner 2007, 251, 8–10, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goyal, R.; Kotru, M.; Gogia, A.; Sharma, S. Qualitative defects with normal sperm counts in a patient attending infertility clinic. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2018, 61, 233–235. [Google Scholar]

- Boitrelle, F.; Shah, R.; Saleh, R.; Henkel, R.; Kandil, H.; Chung, E.; Vogiatzi, P.; Zini, A.; Arfa, M.; Agarwal, A. The Sixth Edition of the WHO Manual for Human Semen Analysis: A Critical Review and SWOT Analysis. Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO laboratory manual for the Examination and processing of human semen, 5th ed.; World Health Organization, 2010.

- López-Botella, A.; Velasco, I.; Acién, M.; Sáez-Espinosa, P.; Todolí-Torró, J.-L.; Sánchez-Romero, R.; Gómez-Torres, M.J. Impact of Heavy Metals on Human Male Fertility—An Overview. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen, 6th Ed. ed; World Health Organization, 2021.

- Tamburrino, L.; Traini, G.; Marcellini, A.; Vignozzi, L.; Baldi, E.; Marchiani, S. Cryopreservation of Human Spermatozoa: Functional, Molecular and Clinical Aspects. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wei, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Jiang, H.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Comparison of intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome with fresh versus frozen-thawed testicular sperm in men with nonobstructive azoospermia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018, 35, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, A.; Diemer, T.; Kopa, Z.; Krausz, C.; Minhas, S.; Tournaye, H. EAU Guidelines on Male Fertility. European Association of Urology 2019.

- DIRECTIVE 2004/23/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 31 March 2004 on setting standards of quality and safety for the donation, procurement, testing, processing, preservation, storage and distribution of human tissues and cells, vol. L 102, 2004, pp. 48-58.

- Commission Directive 2006/17/EC of 8 February 2006 implementing Directive 2004/23/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards certain technical requirements for the donation, procurement and testing of human tissues and cells (Text with EE, vol. L 330M, 2006, pp. 162-174.

- Ohlander, S.; Hotaling, J.; Kirshenbaum, E.; Niederberger, C.; Eisenberg, M.L. Impact of fresh versus cryopreserved testicular sperm upon intracytoplasmic sperm injection pregnancy outcomes in men with azoospermia due to spermatogenic dysfunction: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2014, 101, 344–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczyński, W.; Dhont, M.; Grygoruk, C.; Grochowski, D.; Wołczyński, S.; Szamatowicz, M. The outcome of intracytoplasmic injection of fresh and cryopreserved ejaculated spermatozoa--a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod 2001, 16, 2109–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournaye, H.; Merdad, T.; Silber, S.; et al. No differences in outcome after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with fresh of with frozen-thawed epididymal spermatozoa. Hum Reprod 1999, 14, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hungerford, A.; Bakos, H.W.; Aitken, R.J. Sperm cryopreservation: current status and future developments. 2023, 35, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borate, G.M.; Meshram, A. Cryopreservation of Sperm: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e31402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Tang, Y.-L.; Hu, J.-L.; Zhou, W.-J.; Huang, Z.-H.; Luo, X.-F.; Li, Z.; Zhu, W.-B. Update on techniques for cryopreservation of human spermatozoa. Asian J Androl 2022, 24, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastick, J.; Venetis, C.; Cooke, S.; Storr, A.; Susetio, D.; Chapman, M. Is early embryo development as observed by time-lapse microscopy dependent on whether fresh or frozen sperm was used for ICSI? A cohort study. J Assist Reprod Genet 2017, 34, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, M.; McClure, N.; Lewis, S.E.M. The effects of cryopreservation on sperm morphology, motility and mitochondrial function. Hum Reprod 2002, 17, 704–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadeh, M.E.; Askari, A.S.; Georg, T.; Rosenbaum, P.; Schmidt, W. Effect of freeze-thawing procedure on chromatin stability, morphological alteration and membrane integrity of human spermatozoa in fertile and subfertile men. 1999, 22, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimic, S.; Ban-Frangez, H.; Stimpfel, M. Sperm Cryopreservation Today: Approaches, Efficiency, and Pitfalls. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol 2023, 45, 4716–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, M.; Tarozzi, N.; Nadalini, M.; Borini, A. Human Sperm Cryopreservation: Update on Techniques, Effect on DNA Integrity, and Implications for ART. Adv Urol 2012, 13, 854837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, H. C.; Nikoloska, M.; Ho, H.; Doshi, A.; Maalouf, W. Improved cryopreservation of spermatozoa using vitrification: comparison of cryoprotectants and a novel device for long-term storage. J Assist Reprod Genet 2019, 36, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hungerford, A.J.; Bakos, H.W.; Aitken, R.J. Analysis of sperm separation protocols for isolating cryopreserved human spermatozoa. Reprod Fertil 2023, 4, 220133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, A.P.; Gascón, A.; Martínez, J.V.; Balasch, S.; Botella, I.M. Sperm preparation after freezing improves motile sperm count, motility, and viability in frozen-thawed sperm compared with sperm preparation before freezing-thawing process. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018, 35, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutton, C.; Escoffier, J.; Martinez, G.; Arnoult, C.; Ray, P.F. Teratozoospermia: spotlight on the main genetic actors in the human. Human Reproduction Update 2015, 21, 455–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Braekeleer, M.; Nguyen, M.H.; Morel, F.; Perrin, A. Genetic aspects of monomorphic teratozoospermia: a review. J Assist Reprod Genet 2015, 32, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemes, H.E. Sperm Ultrastructure in Fertile Men and Male Sterility: Revisiting Teratozoospermia. In The Sperm Cell: Production, Maturation, Fertilization, Regeneration; Cambridge University Press, 2017; pp. 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fesahat, F.; Henkel, R.; Agarwal, A. Globozoospermia syndrome: An update. Andrologia 2019. [CrossRef]

- Carmignac, V.; Dupont, J.-M.; Fierro, R.C.; Berberet, J.; Bruno, C.; Lieury, N.; Dulioust, E.; Auger, J.; Fauque, P. Diagnostic genetic screening for assisted reproductive technologies patients with macrozoospermia. Andrology 2017, 5, 37–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhatib, R.A.; Paci, M.; Longepied, G.; Saias-Magnan, J.; Courbiere, B.; Guichaoua, M.-R.; Levy, N.; Metzler-Guillemain, C.; Mitchell, M.J. Homozygous deletion of SUN5 in three men with decapitated spermatozoa. Human Molecular Genetics 2017, 26, 3167–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, F.; Yang, X.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J. Patients with acephalic spermatozoa syndrome linked to SUN5 mutations have a favorable pregnancy outcome from ICSI. Andrology 2018, 33, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak-Jędrzejowska, R.; Bakalczuk, S.; Berger, A.; Bergier, L.; Filipiak, E.; Frącki, S.; Jędrzejczak, P.; Kula, K.; Marchlewska, K.; Piasecka, M.; Puacz, E.; Słowikowska-Hilczer, J.; Zagocka, G.T.-H.I.E. Podstawowe badanie nasienia - rekomendacje Polskiego Towarzystwa Andrologicznego i Krajowej Izby Diagnostów Laboratoryjnych. w Postępy Andrologii Online, 2015.

- Ragini, G.; Caccamo, A.M.; Serra, A.D.; Guercilena, S. Computerized slow-staged freezing of semen from men with testicular tumors or Hodgkin's disease preserves sperm better than standard vapor freezing. Fertil Steril 1990, 53, 1072–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raad, G.; Lteif, L.; Lahoud, R.; Azoury, J.; Tanios, J.; Hazzouri, M. Cryopreservation media differentially affect sperm motility, morphology and DNA integrity. Andrology 2018, 6, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Androni, D.A.; Dodds, S.; Tomlinson, M.; Maalouf, W.E. Is pre-freeze sperm preparation more advantageous than post-freeze? Reprod Fertil 2021, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dede, G.; Saylan, A. The effect of astaxanthin on human sperm parameters after cryopreservation. Can Urol Assoc J 2022, 16, E552–E557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghantabpour, T.; Nashtaei, M.S.; Nekoonam, S.; Razaei, H.; Amidi, F. The Effect of Astaxanthin on Motility, Viability, Reactive Oxygen Species, Apoptosis, and Lipid Peroxidation of Human Spermatozoa During the Freezing-Thawing Process. Biopreserv Biobank 2022, 22, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Gan, R.-X.; Hu, J.-L.; Liu, F.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, W.-B.; Li, Z. Clinical benefit for cryopreservation of single human spermatozoa for ICSI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology 2022, 10, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadeh, M.E.; Dehn, C.; Hippach, M.; Zeginiadou, T.; Stieber, M.; Georg, T.; Rosenbaum, P.; Schmidt, W. Comparison between computerized slow-stage and static liquid nitrogen vapour freezing methods with respect to the deleterious effect on chromatin and morphology of spermatozoa from fertile and subfertile men. Int J Androl 2001, 24, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.J.; Acton, E.; Murray, B.J.; Fonseca, F. Freezing injury: the special case of the sperm cell. Cryobiology 2012, 64, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongdee, P.; Sukprasert, M.; Satirapod, C.; Wongkularb, A.; Choktanasiri, V. Comparison of Cryopreserved Human Sperm between Ultra Rapid Freezing and Slow Programmable Freezing: Effect on Motility, Morphology and DNA Integrity. J Med Assoc Thai 2015, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Verheyen, G.; Pletincx, I.; Van Steirteghem, A. Effect of freezing method, thawing temperature and post-thaw dilution/washing on motility (CASA) and morphology characteristics of high-quality human sperm. Hum Reprod 1993, 8, 1678–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamera, J.C.; Buffone, M.G.; Doncel, G.F.; Brugo-Olmeda, S.; de Vincentiis, S.; Calamera, M.M.; Storey, B.T.; Alvarez, J.G. Effect of thawing temperature on the motility recovery of cryopreserved human spermatozoa. Fertility and Sterility 2010, 93, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menkveld, R.; Wong, W.Y.; Lombard, C.J.; Wetzels, A.M.; Thomas, C.M.; Merkus, H.M. Semen parameters, including WHO and strict criteria morphology, in a fertile population: an effort towards standardization of in-vivo thresholds. Hum Reprod 2001, 16, 1165–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.; Said, T.; Paasch, U.; Agarwal, A. The relationship between human sperm apoptosis, morphology and the sperm deformity index. Hum Reprod 2007, 22, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, T.M.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Thomas, A.J., Jr.; Sikka, S.C. Impact of sperm morphology on DNA damage caused by oxidative stress induced by beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Fertil Steril 2005, 83, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, T.M.; Aziz, N.; Sharma, R.K.; Lewis-Jones, I.; Thomas, A.J., Jr.; Agarwal, A. Novel association between sperm deformity index and oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in infertile male patients. Asian J Androl 2005, 7, 121–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.; Sharma, R.K.; Mahfouz, R.; Jha, R.; Agarwal, A. Association of sperm morphology and the sperm deformity index (SDI) with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage inhibition. 2011, 95, 2481–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Salom, M.; Romero, J.; Minguez, Y.; Rubio, C.; De los Santos, M.J.; Remohí, J.; Pellicer, A. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with cryopreserved testicular spermatozoa. Hum Reprod 1996, 11, 1309–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulug, U.; Bener, F.; Karagenc, L.; Ciray, N.; Bahceci, M. Outcomes in couples undergoing ICSI: comparison between fresh and frozen-thawed surgically retrieved spermatozoa. Int J Androl 2005, 28, 343–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedler, S.; Raziel, A.; Strassburger, D.; Komarovsky, D.; Ron-El, R. The outcome of intracytoplasmic injection of fresh and cryopreserved epididymal spermatozoa from patients with obstructive azoospermia--a comparative study. Hum Reprod 1998, 13, 1872–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrels, K.L.; Zini, A.S.; Casper, R.F.; Meriano, J.S.; Jarvi, K.A. Fresh and frozen epididymal sperm yield comparable pregnancy rates for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Arch Androl 1998, 41, 159–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherouveim, P.; Vagios, S.; Hammer, K.; Fitz, V.; Jiang, V.S.; Dimitriadis, I.; Sacha, C.R.; James, K.E.; Bormann, C.L.; Souter, I. The impact of cryopreserved sperm on intrauterine insemination outcomes: is frozen as good as fresh? Front Reprod Health 2023, 31, 1181751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, E.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Sperm freezing damage: the role of regulated cell death. Cell Death Discovery 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouhier, C.; Pons-Rejraji, H.; Dollet, S.; Chaput, L.; Bourgne, C.; Berger, M.; Pereira, B.; Tchirkov, A.; Brugnon, F. Freezing Does Not Alter Sperm Telomere Length despite Increasing DNA Oxidation and Fragmentation. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, E.T.; McClure, N.; Lewis, S.E. Cryopreservation of human semen and prepared sperm: effects on motility parameters and DNA integrity. 2001, 76, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanò, M.; Cordelli, E.; Leter, G.; Lombardo, F.; Lenzi, A.; Gandini, L. Nuclear chromatin variations in human spermatozoa undergoing swim-up and cryopreservation evaluated by the flow cytometric sperm chromatin structure assay. Mol Hum Reprod 1999, 5, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umirbaeva, A.; Kurenkov, A.; Makhanbetova, A.; Seisenov, B.; Vorobjev, I.A.; Barteneva, N.S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of cryopreserved bovine sperm assessment: harnessing imaging flow cytometry for multi-parametric analysis. Front Vet Sci 2024, 11, 1371586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchuk, T.; Petrushko, M.; Gapon, A.; Piniaiev, V.; Kuleshova, L. The impact of cryopreservation on the morphology of spermatozoa in men with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Cryobiology 2021, 100, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

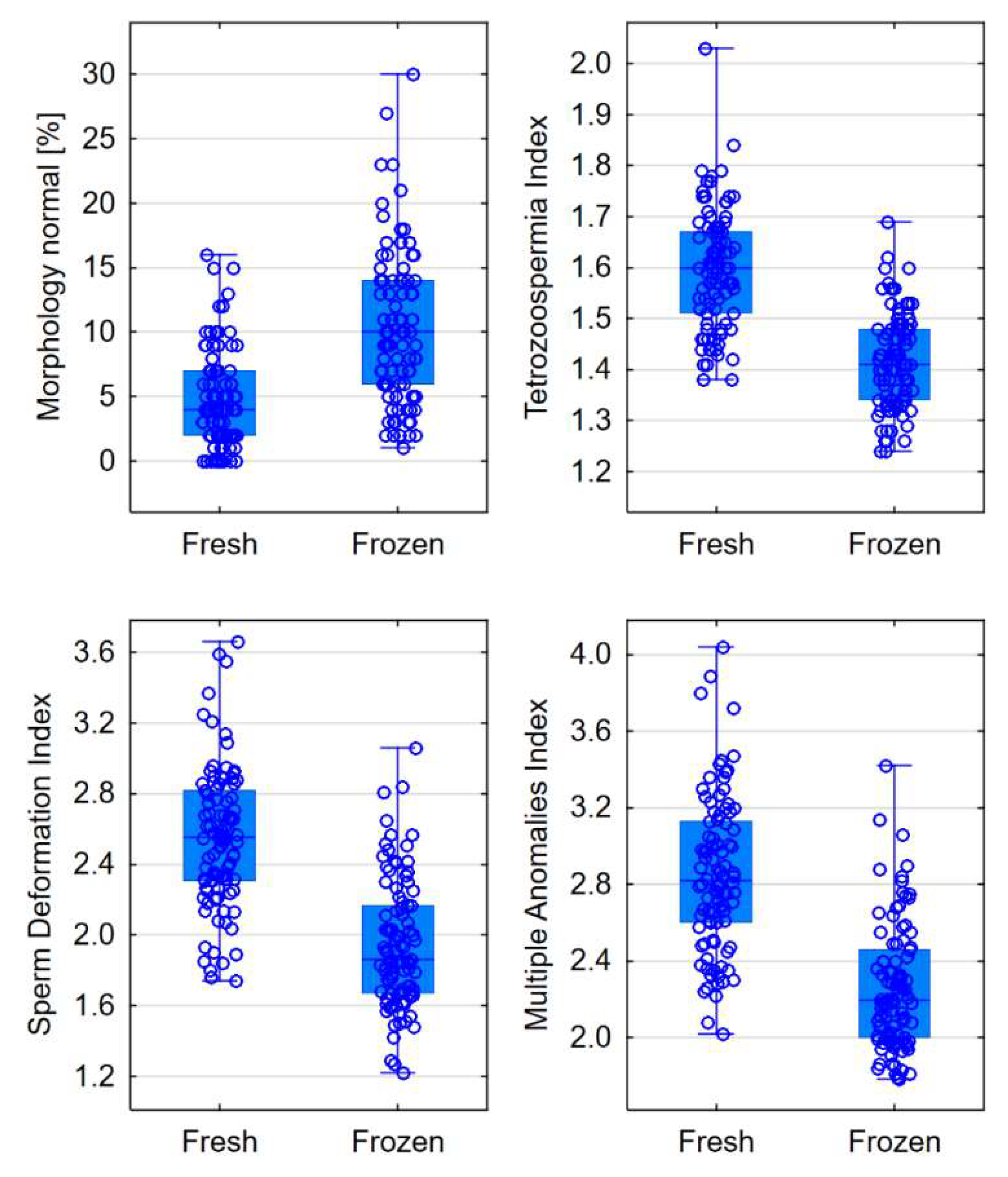

| Morphology | Fresh semen | Frozen semen | p level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal [%] | 4 (2-7) | 10 (6-14) | <0.0001 |

| Teratozoospermia Index (TZI) | 1.60 (1.51-1.67) | 1.41 (1.34-1.48) | <0.0001 |

| Sperm Deformation Index (SDI) | 2.56 (2.31-2.82) | 1.86 (1.67-2.17) | <0.0001 |

| Multiple Anomalies Index (MAI) | 2.82 (2.60-3.13) | 2.20 (2.00-2.46) | <0.0001 |

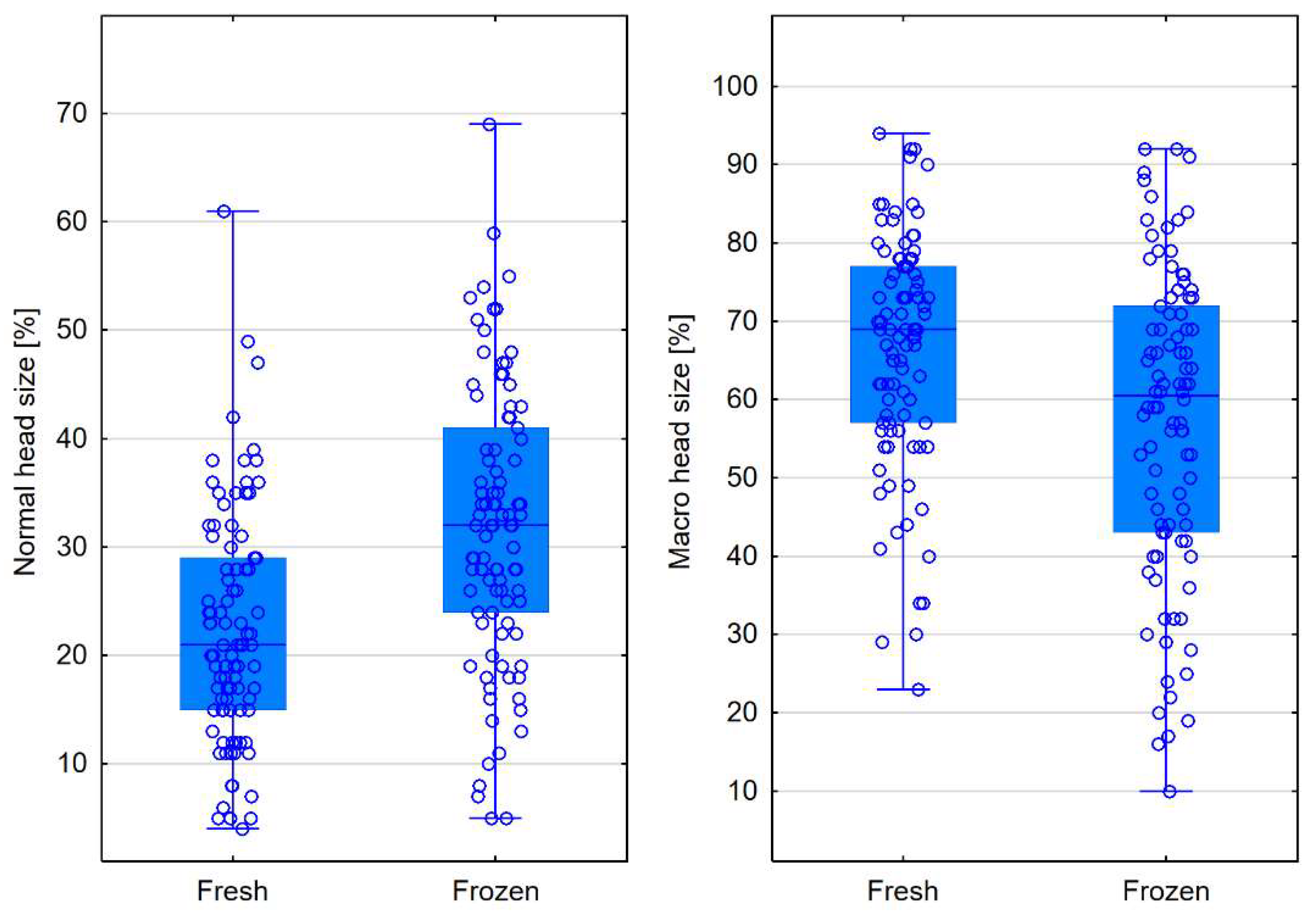

| Head size | Fresh semen | Frozen semen | p level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal [%] | 21 (15-29) | 32 (24-41) | <0.0001 |

| Micro [%] | 8 (5-15) | 6.5 (3-15) | 0.2694 |

| Macro [%] | 69 (57-77) | 60.5 (43-72) | <0.0001 |

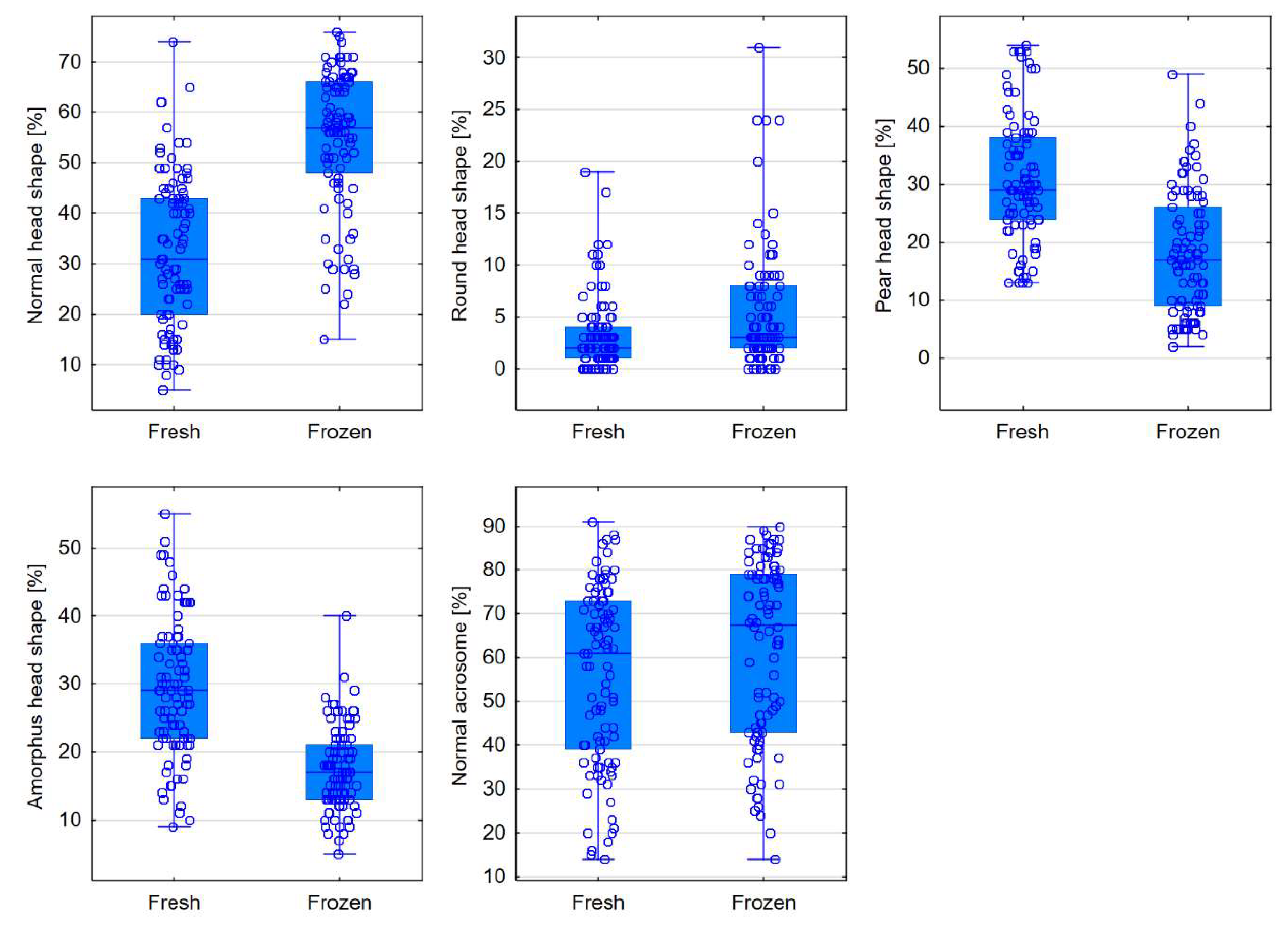

| Head shape | Fresh semen | Frozen semen | p level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal [%] | 31 (20-43) | 57 (48-66) | <0.0001 |

| Conical [%] | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | 0.0665 |

| Thin [%] | 3 (1-5) | 2 (0-5) | 0.0580 |

| Round [%] | 2 (1-4) | 3 (2-8) | <0.0001 |

| Pear-shaped [%] | 29 (24-38) | 17 (9-26) | <0.0001 |

| Amorphous [%] | 29 (22-36) | 17 (13-21) | <0.0001 |

| Acrosome | |||

| Normal [%] | 61 (39-73) | 67.5 (43-79) | 0.0009 |

| Midpiece | Fresh semen | Frozen semen | p level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal midpiece [%] | 45 (38-52) | 61.5 (57-67) | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal size [%] | 45 (37-52) | 28 (23-35) | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal insertion [%] | 24 (18-28) | 17 (13-20) | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal angle [%] | 9 (6-11) | 4 (2-7) | <0.0001 |

| Morphometrics | Fresh semen | Frozen semen | p level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head length [μm] | 5.57 (5.33-5.84) | 5.20 (4.98-5.45) | <0.0001 |

| Head width [μm] | 3.04 (2.91-3.23) | 3.24 (3.05-3.37) | <0.0001 |

| Head area [μm2] | 13.78 (12.89-14.48) | 13.72 (12.69-14.54) | 0.7831 |

| Head circumference [μm] | 15.27 (14.73-15.75) | 14.55 (13.96-15.02) | <0.0001 |

| Ellipsoidal heads | 1.92 (1.73-2.06) | 1.64 (1.54-1.77) | <0.0001 |

| Elongated heads | 0.28 (0.25-0.32) | 0.23 (0.20-0.26) | <0.0001 |

| Smooth heads | 0.75 (0.72-0.78) | 0.82 (0.80-0.84) | <0.0001 |

| Regular heads | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | 0.96 (0.96-0.97) | <0.0001 |

| Midpiece width [μm] | 1.42 (1.34-1.49) | 1.29 (1.25-1.35) | <0.0001 |

| Midpiece area [μm2] | 1.64 (1.52-1.82) | 1.69 (1.57-1.79) | 0.7777 |

| Midpiece angle [°] | 27.05 (21.86-33.85) | 19.36 (15.90-22.57) | <0.0001 |

| Acrosome-to-head ratio [%] | 53.46 (48.05-69.86) | 58.65 (50.41-70.53) | 0.0982 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).