Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

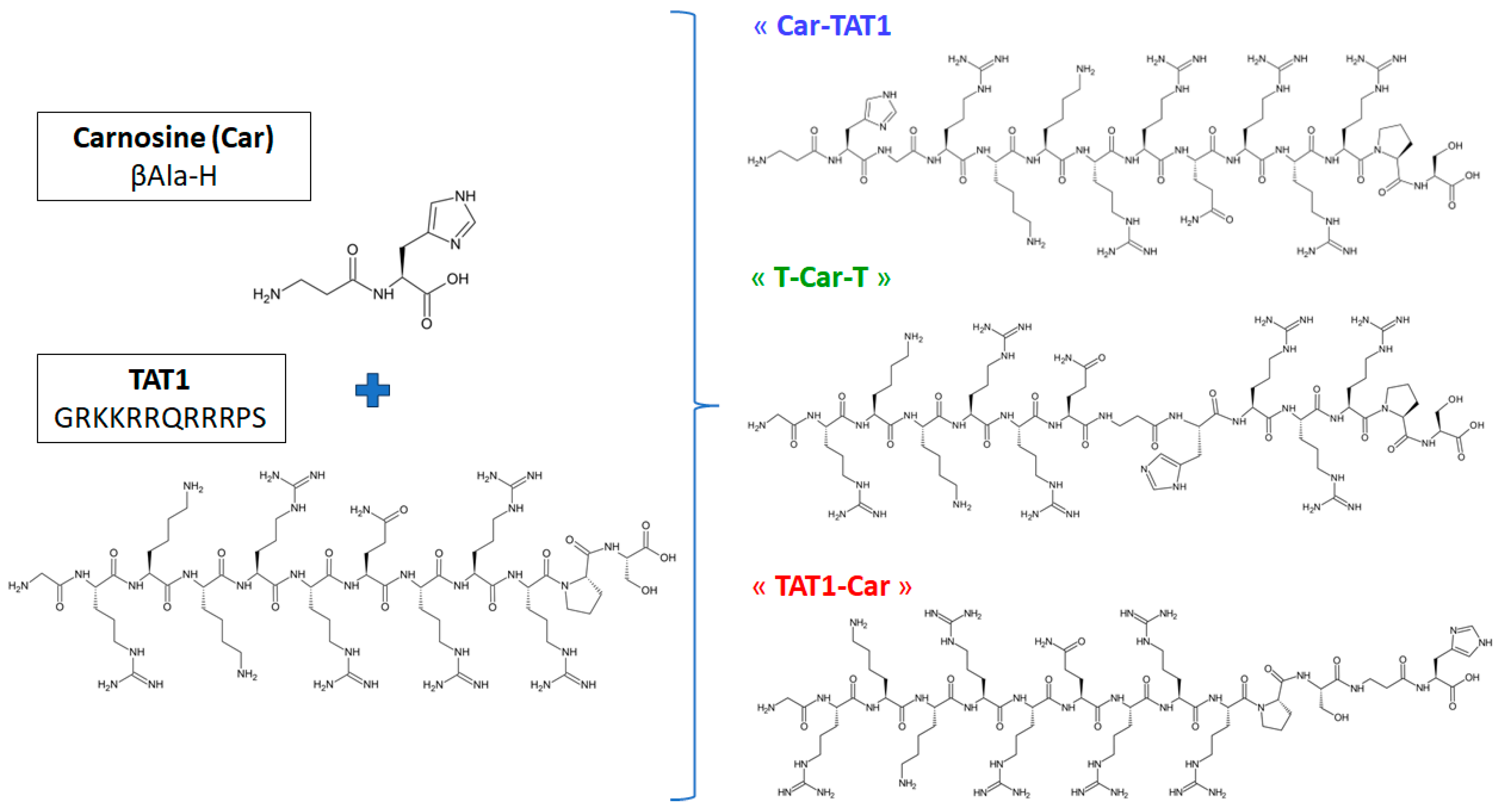

2. Results and Discussion

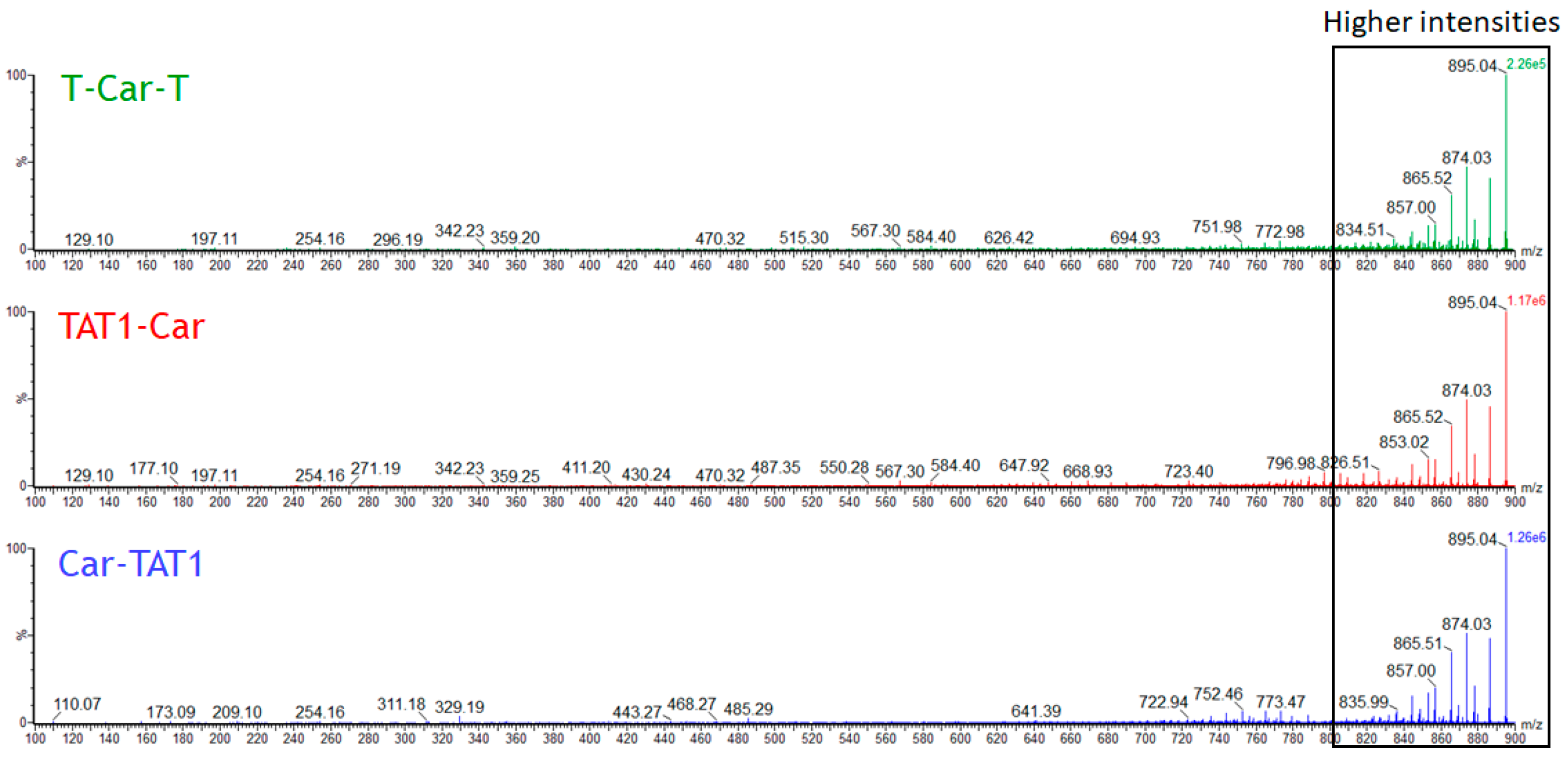

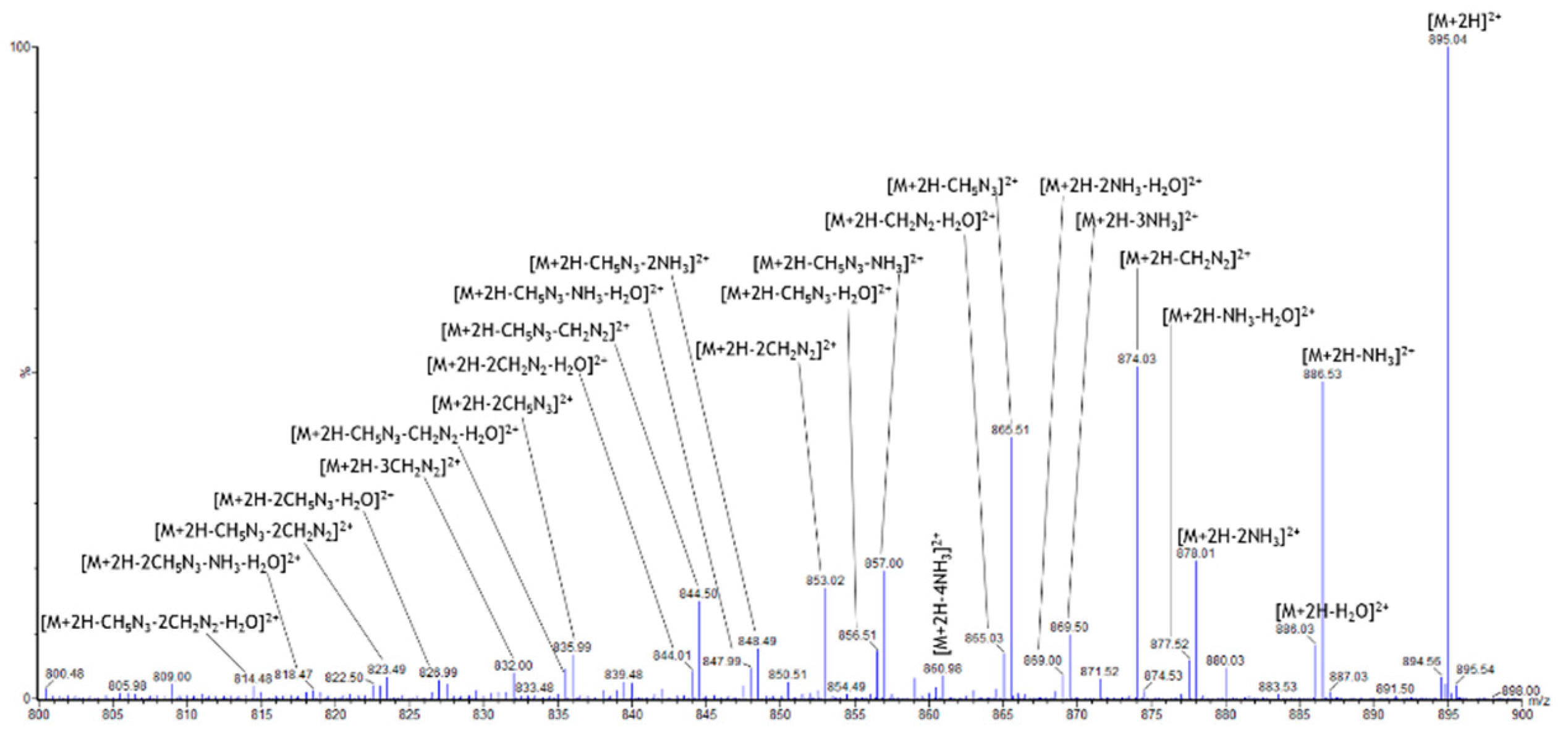

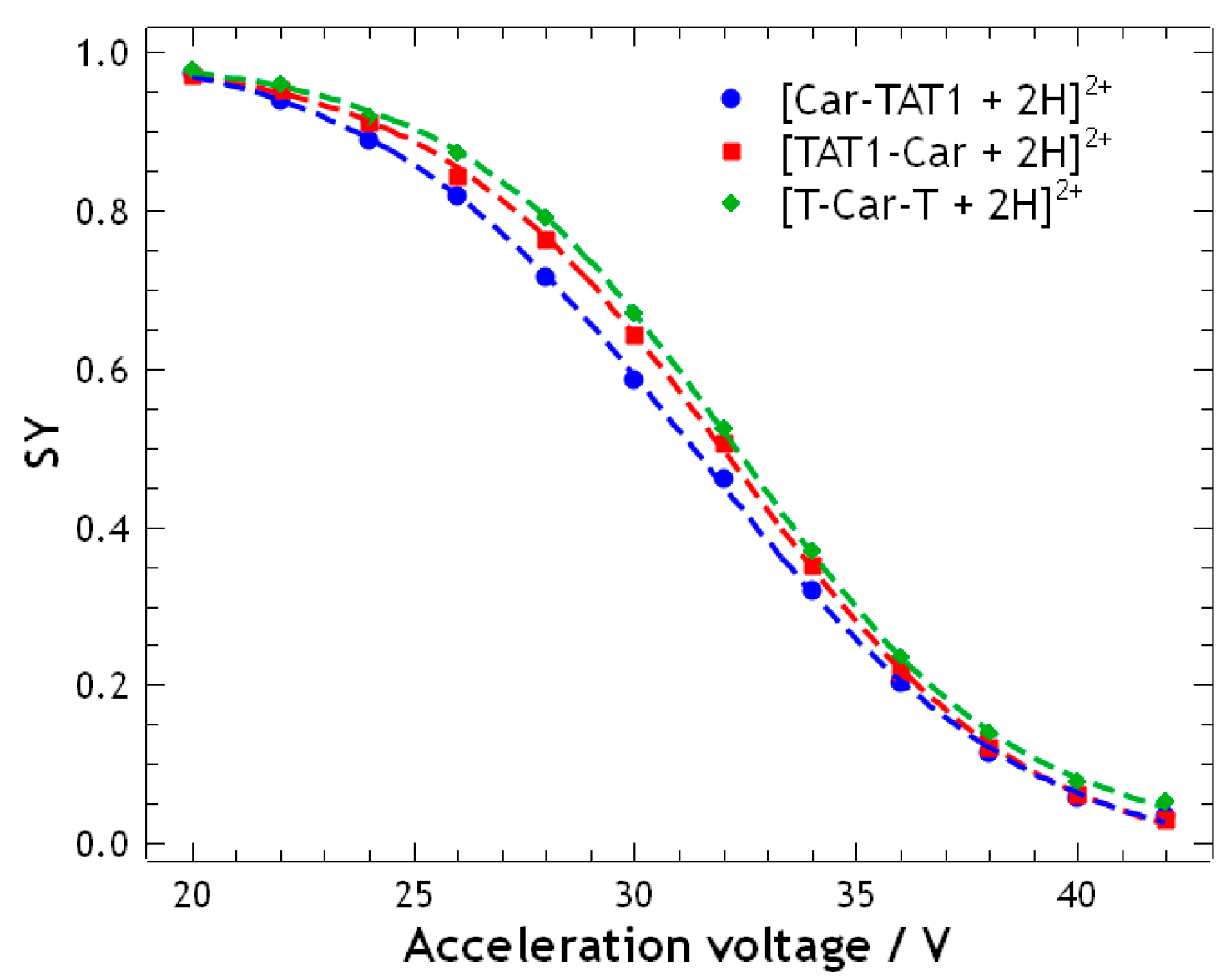

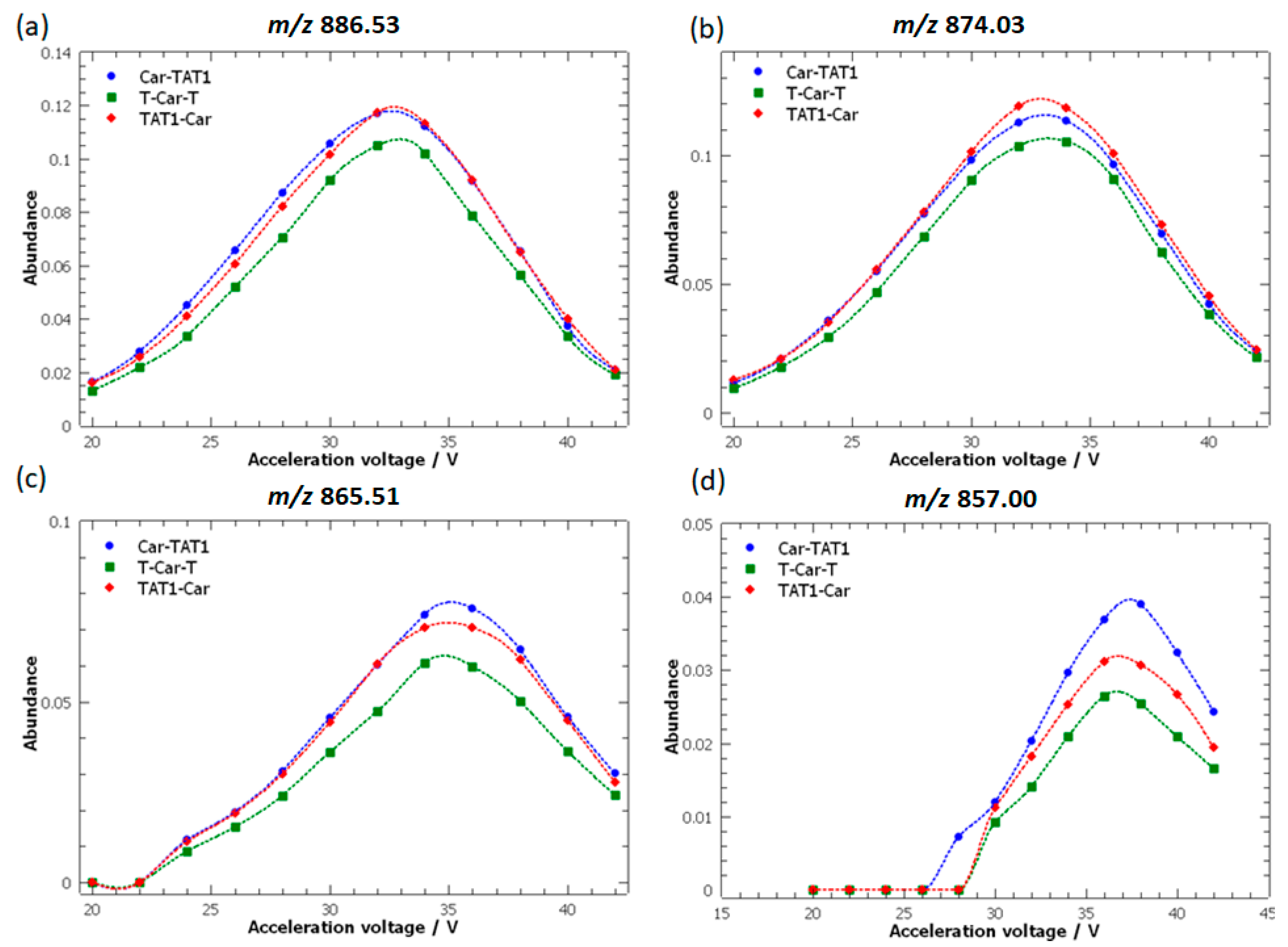

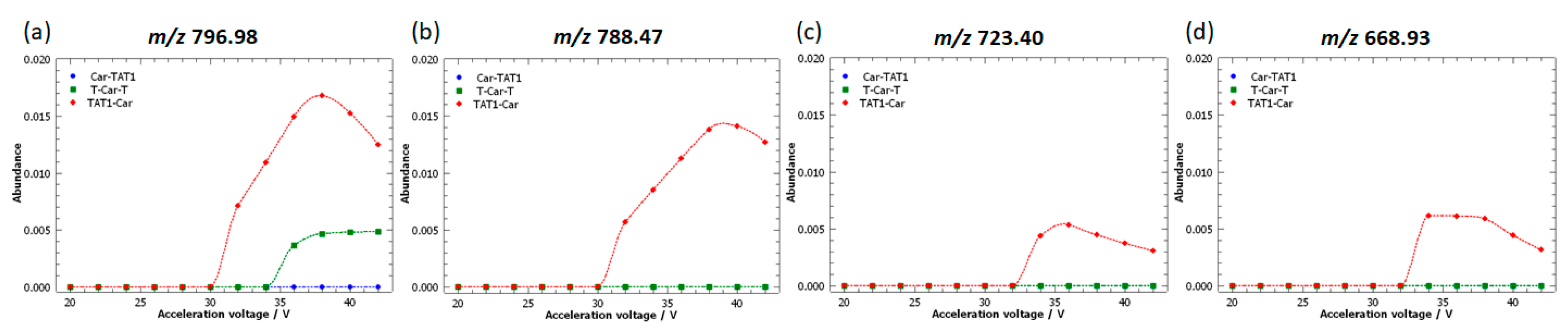

2.1. Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry and Break Down Curves of TAT1-Carnosine Peptides

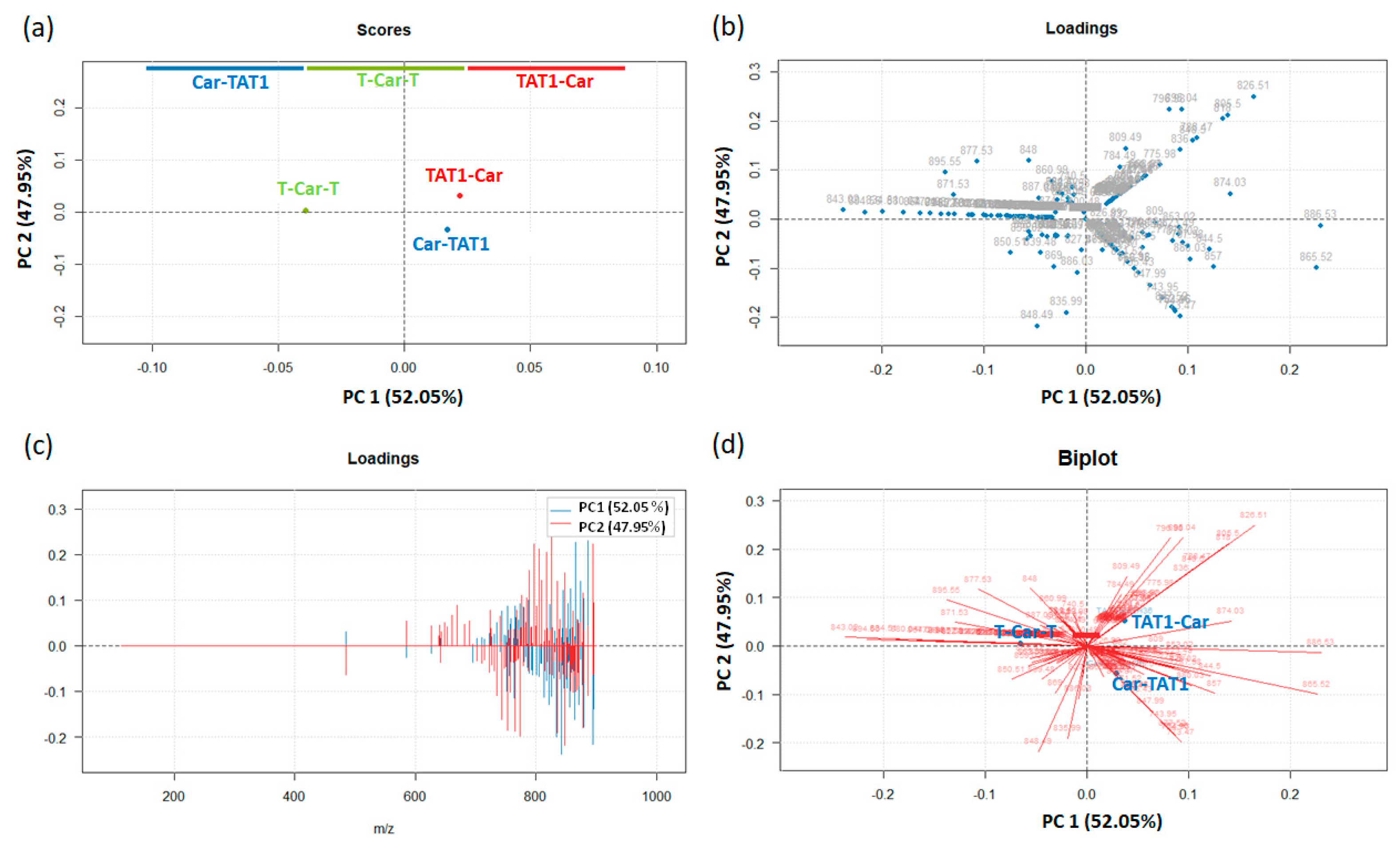

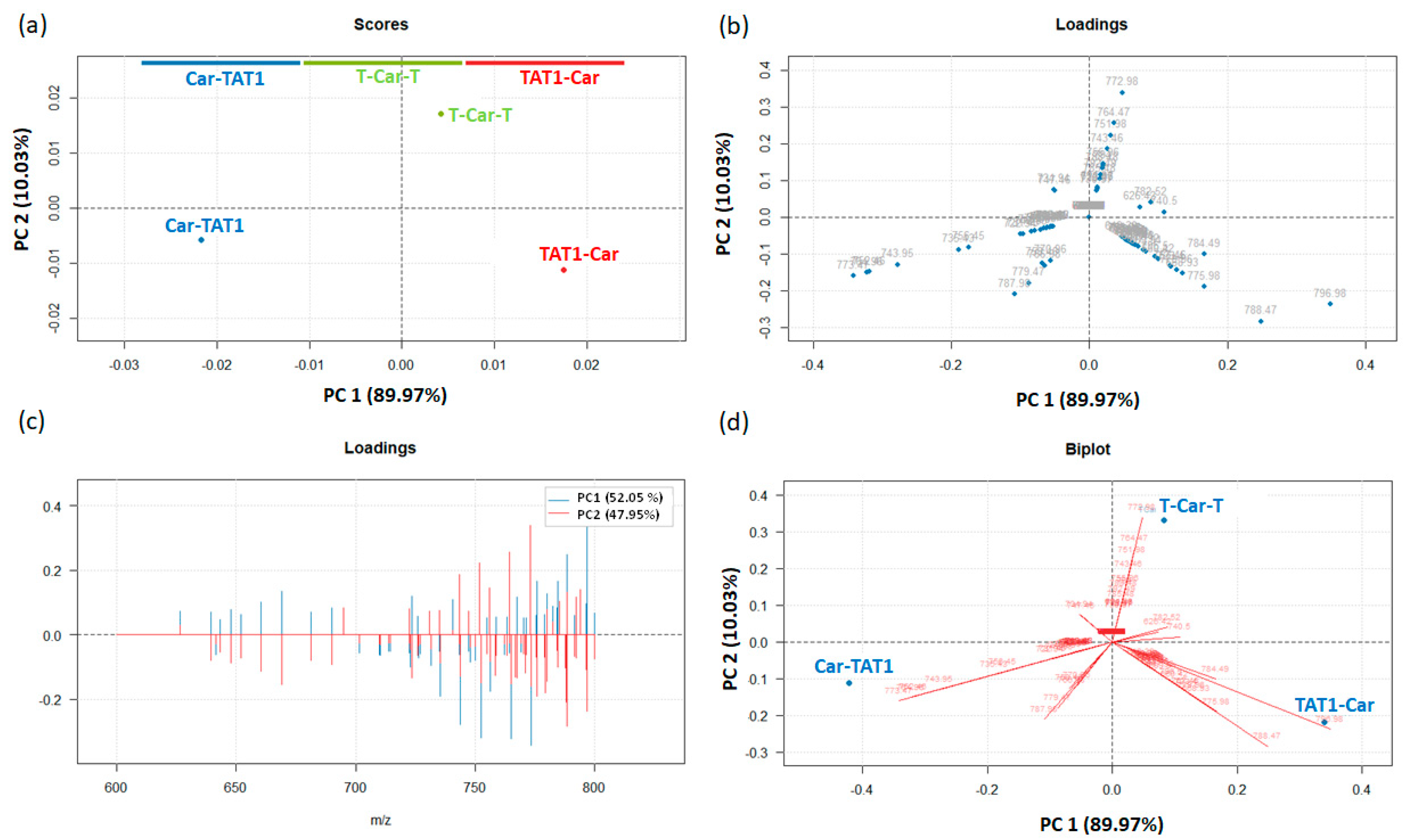

2.2. Principal Component Analysis for the Differentiation of TAT1-Carnosine Peptides

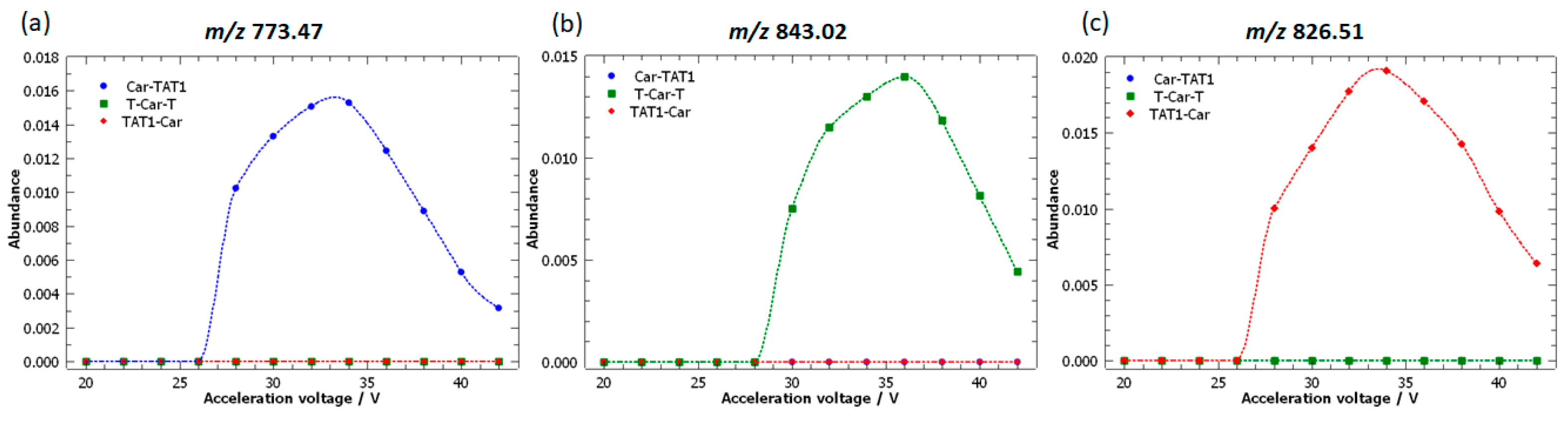

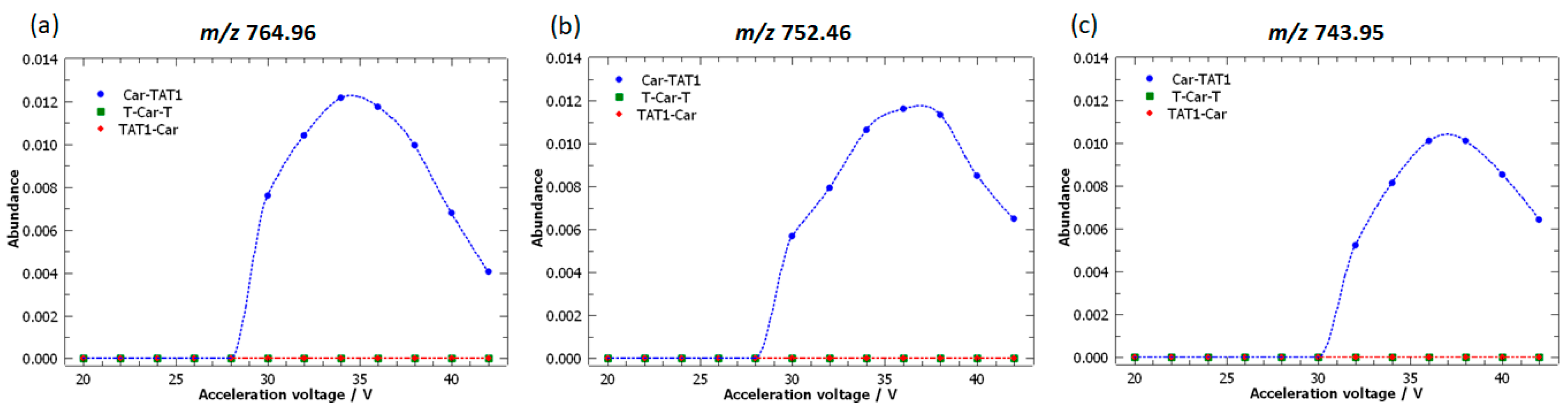

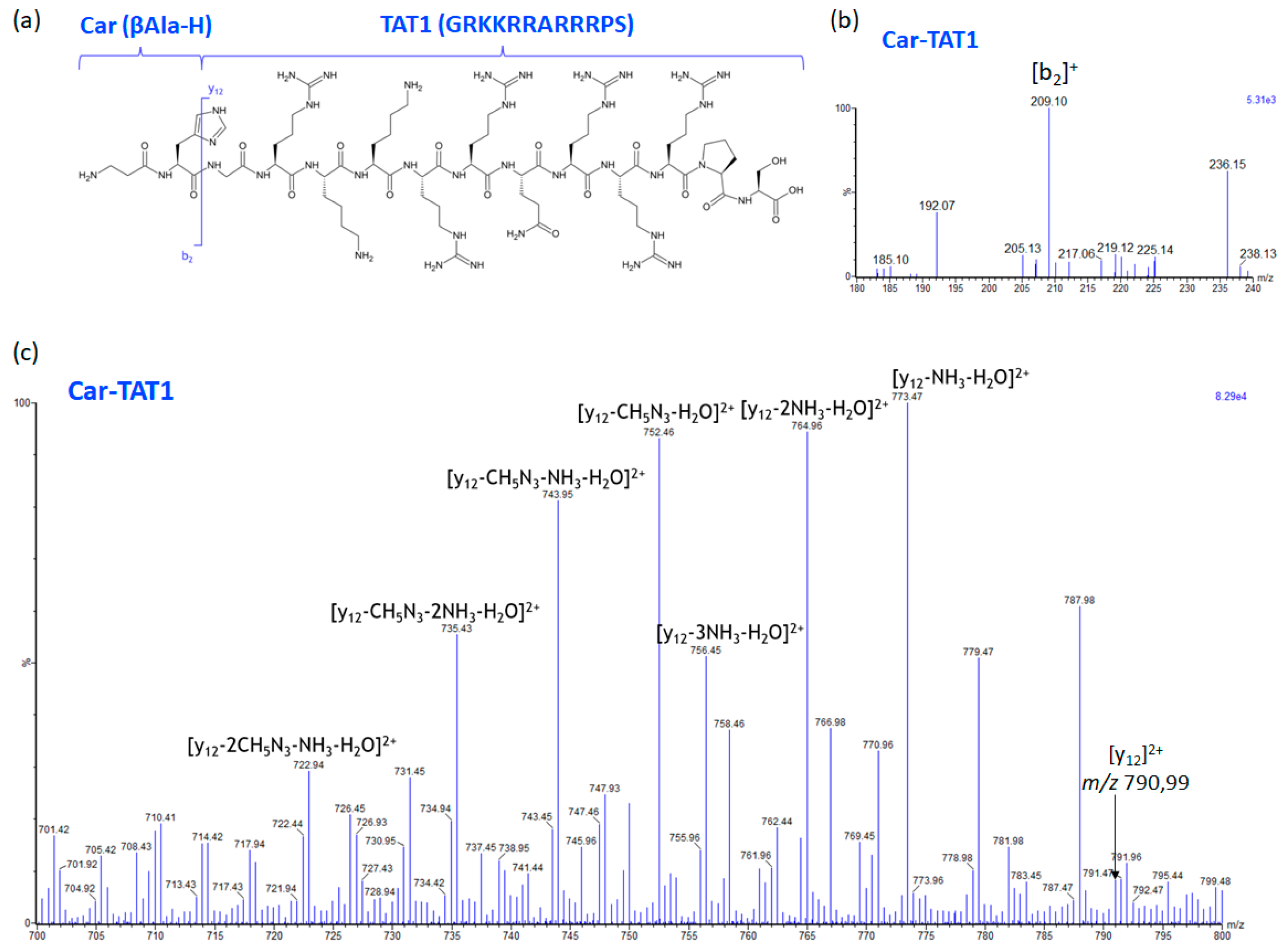

2.3. Specific Fragment Ions for CAR-TAT1 Identified by PCA

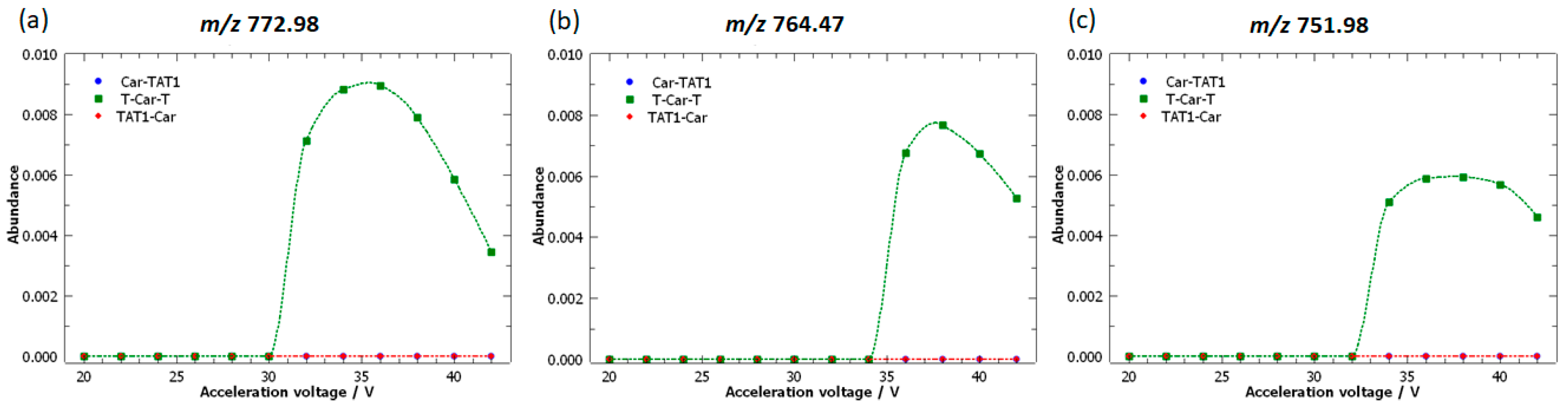

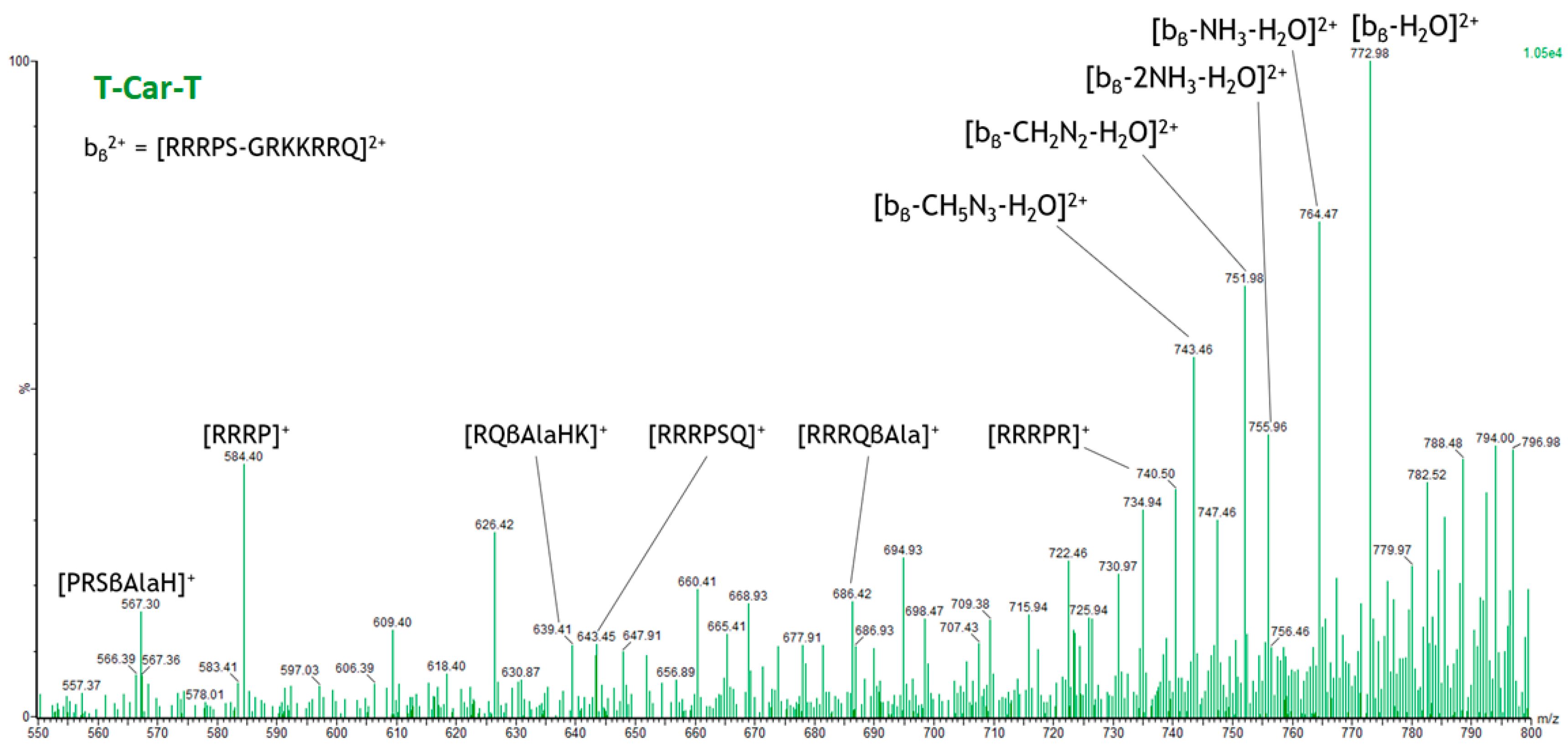

2.4. Specific Fragment Ions for T-Car-T Identified by PCA

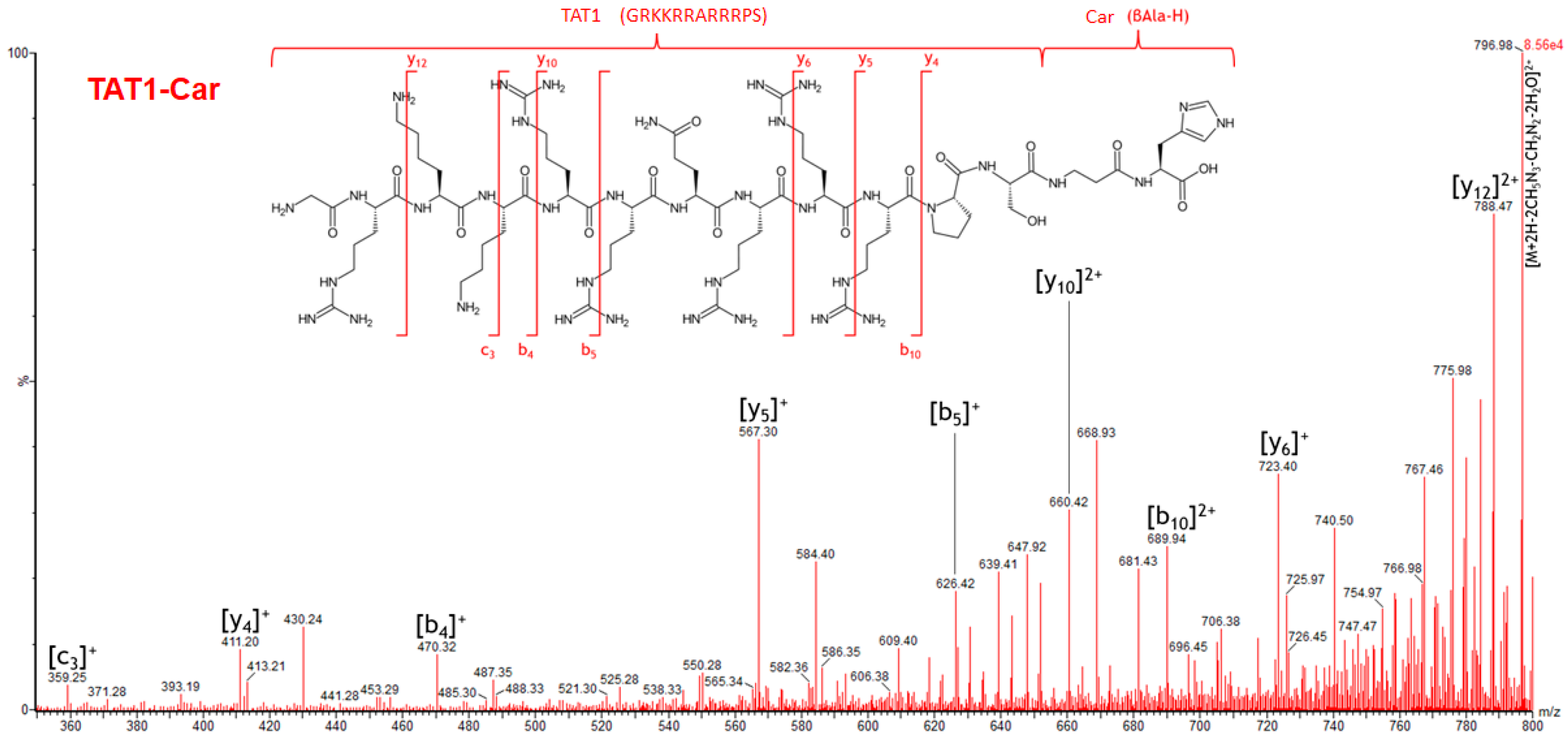

2.5. Specific Fragment Ions for TAT1-Car Identified by PCA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Synthesis of Peptides

3.2. Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caruso, G. Unveiling the Hidden Therapeutic Potential of Carnosine, a Molecule with a Multimodal Mechanism of Action: A Position Paper. Molecules 2022, 27, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewska, K.; Dzierzbicka, K.; Inkielewicz-Stępniak, I.; Przybyłowska, M. Therapeutic Potential of Carnosine and Its Derivatives in the Treatment of Human Diseases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedje, K.E.; Stevens, K.; Barnes, S.; Weaver, D.F. β-Alanine as a Small Molecule Neurotransmitter. Neurochemistry International 2010, 57, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Rescigno, F.; Meloni, M.; Baron, G.; Aldini, G.; Carini, M.; D’Amato, A. Oxidative Stress Modulation by Carnosine in Scaffold Free Human Dermis Spheroids Model: A Proteomic Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellia, F.; Vecchio, G.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Calabrese, V.; Rizzarelli, E. Neuroprotective Features of Carnosine in Oxidative Driven Diseases. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2011, 32, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Fresta, C.G.; Fidilio, A.; O’Donnell, F.; Musso, N.; Lazzarino, G.; Grasso, M.; Amorini, A.M.; Tascedda, F.; Bucolo, C.; et al. Carnosine Decreases PMA-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Murine Macrophages. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Benatti, C.; Musso, N.; Fresta, C.G.; Fidilio, A.; Spampinato, G.; Brunello, N.; Bucolo, C.; Drago, F.; Lunte, S.M.; et al. Carnosine Protects Macrophages against the Toxicity of Aβ1-42 Oligomers by Decreasing Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, V.; Pampalone, M.; Frazziano, G.; Grasso, G.; Rizzarelli, E.; Ricordi, C.; Casu, A.; Iannolo, G.; Conaldi, P.G. Carnosine Protects Pancreatic Beta Cells and Islets against Oxidative Stress Damage. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2018, 474, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyrev, A.A.; Gallant, S.Ch.; Sukhich, G.T. Carnosine, the Protective, Anti-Aging Peptide. Biosci Rep 1999, 19, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menini, S.; Iacobini, C.; Fantauzzi, C.B.; Pugliese, G. L-Carnosine and Its Derivatives as New Therapeutic Agents for the Prevention and Treatment of Vascular Complications of Diabetes. Current Medicinal Chemistry 27, 1744–1763. [CrossRef]

- Distefano, A.; Caruso, G.; Oliveri, V.; Bellia, F.; Sbardella, D.; Zingale, G.A.; Caraci, F.; Grasso, G. Neuroprotective Effect of Carnosine Is Mediated by Insulin-Degrading Enzyme. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, M.; Sadakane, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Kato-Negishi, M.; Tanaka, K. Carnosine as a Possible Drug for Zinc-Induced Neurotoxicity and Vascular Dementia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.J.; Vistoli, G.; Katunga, L.A.; Funai, K.; Regazzoni, L.; Monroe, T.B.; Gilardoni, E.; Cannizzaro, L.; Colzani, M.; Maddis, D.D.; et al. A Carnosine Analog Mitigates Metabolic Disorders of Obesity by Reducing Carbonyl Stress. J Clin Invest 2018, 128, 5280–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Fresta, C.G.; Martinez-Becerra, F.; Antonio, L.; Johnson, R.T.; de Campos, R.P.S.; Siegel, J.M.; Wijesinghe, M.B.; Lazzarino, G.; Lunte, S.M. Carnosine Modulates Nitric Oxide in Stimulated Murine RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Mol Cell Biochem 2017, 431, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. Eric.; Antholine, W.E. Chelation Chemistry of Carnosine. Evidence That Mixed Complexes May Occur in Vivo. J. Phys. Chem. 1979, 83, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaffaglione, V.; Rizzarelli, E. Carnosine, Zinc and Copper: A Menage a Trois in Bone and Cartilage Protection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 16209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, I.; Kolobarić, N.; Stupin, A.; Matić, A.; Kozina, N.; Mihaljević, Z.; Mihalj, M.; Šušnjara, P.; Stupin, M.; Ćurić, Ž.B.; et al. Carnosine, Small but Mighty—Prospect of Use as Functional Ingredient for Functional Food Formulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, M.D.; Fraser, S.; Boer, J.C.; Plebanski, M.; de Courten, B.; Apostolopoulos, V. Anti-Cancer Effects of Carnosine—A Dipeptide Molecule. Molecules 2021, 26, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artasensi, A.; Mazzotta, S.; Sanz, I.; Lin, L.; Vistoli, G.; Fumagalli, L.; Regazzoni, L. Exploring Secondary Amine Carnosine Derivatives: Design, Synthesis, and Properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orioli, M.; Vistoli, G.; Regazzoni, L.; Pedretti, A.; Lapolla, A.; Rossoni, G.; Canevotti, R.; Gamberoni, L.; Previtali, M.; Carini, M.; et al. Design, Synthesis, ADME Properties, and Pharmacological Activities of β-Alanyl-D-Histidine (D-Carnosine) Prodrugs with Improved Bioavailability. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeang, K.-T.; Xiao, H.; Rich, E.A. Multifaceted Activities of the HIV-1 Transactivator of Transcription, Tat *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 28837–28840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivès, E.; Brodin, P.; Lebleu, B. A Truncated HIV-1 Tat Protein Basic Domain Rapidly Translocates through the Plasma Membrane and Accumulates in the Cell Nucleus*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 16010–16017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzuti, M.; Nizzardo, M.; Zanetta, C.; Ramirez, A.; Corti, S. Therapeutic Applications of the Cell-Penetrating HIV-1 Tat Peptide. Drug Discovery Today 2015, 20, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distefano, A.; Calì, F.; Gaeta, M.; Tuccitto, N.; Auditore, A.; Licciardello, A.; D’Urso, A.; Lee, K.-J.; Monasson, O.; Peroni, E.; et al. Carbon Dots Surface Chemistry Drives Fluorescent Properties: New Tools to Distinguish Isobaric Peptides. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 625, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auditore A; Tuccitto N; Grasso G; Monasson O; Peroni E; Licciardello A Time-of-Flight SIMS Investigation of Peptides Containing Cell Penetrating Sequences. Biointerphases 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Antonio Zingale, G.; Pandino, I.; Tuccitto, N.; Distefano, A.; Calì, F.; Calcagno, D.; Grasso, G. Carbon Dots Fluorescence Can Be Used to Distinguish Isobaric Peptide and to Monitor Protein Oligomerization Dynamics. Methods 2024, 230, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uclés, S.; Lozano, A.; Sosa, A.; Parrilla Vázquez, P.; Valverde, A.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Matrix Interference Evaluation Employing GC and LC Coupled to Triple Quadrupole Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2017, 174, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Maher, N.; Torres, R.; Cotto, C.; Hastings, B.; Dasgupta, M.; Hyman, R.; Huebert, N.; Caldwell, G.W. Isobaric Metabolite Interferences and the Requirement for Close Examination of Raw Data in Addition to Stringent Chromatographic Separations in Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Drugs in Biological Matrix. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2008, 22, 2021–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.A.; Cooks, R.G. Peer Reviewed: Chiral Analysis by MS. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 25 A–31 A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.A.; Wu, L.; Cooks, R.G. Differentiation and Quantitation of Isomeric Dipeptides by Low-Energy Dissociation of Copper(II)-Bound Complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 12, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, J.; Delvaux, C.; Kune, C.; Eppe, G.; de Pauw, E. The Use of Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry for Isomer Composition Determination Extracted from Se-Rich Yeast. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 11246–11254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanozin, E.; Morsa, D.; De Pauw, E. Energetics and Structural Characterization of Isomers Using Ion Mobility and Gas-Phase H/D Exchange: Learning from Lasso Peptides. PROTEOMICS 2015, 15, 2823–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapthorn, C.; Pullen, F.; Chowdhry, B.Z. Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry (IMS-MS) of Small Molecules: Separating and Assigning Structures to Ions. Mass Spectrom Rev 2013, 32, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsa, D.; Defize, T.; Dehareng, D.; Jérôme, C.; De Pauw, E. Polymer Topology Revealed by Ion Mobility Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 9693–9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, J.-Y.; Han, D.-Q.; Yao, Z.-P. Recent Advances in Differentiation of Isomers by Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 124, 115801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, M.J.; Nanney, A.L.M.; Patrick, A.L. Energy-Resolved In-Source Collison-Induced Dissociation for Isomer Discrimination. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 35, 2631–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Mayes, H.B.; Morreel, K.; Katahira, R.; Li, Y.; Ralph, J.; Black, B.A.; Beckham, G.T. Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry as a Tool for Identification of Lignin Depolymerization Products. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202201441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.G. Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry: A Comparison of Quadrupole Cell and Cone-Voltage Collision-Induced Dissociation. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 1999, 13, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, A.; Jeanne Dit Fouque, D.; Memboeuf, A. Ion Trap MS Using High Trapping Gas Pressure Enables Unequivocal Structural Analysis of Three Isobaric Compounds in a Mixture by Using Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry and the Survival Yield Technique. J Mass Spectrom 2020, 55, e4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, A.; dit Fouque, D.J.; Lartia, R.; Memboeuf, A. Removal of Isobaric Interference Using Pseudo-Multiple Reaction Monitoring and Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry for the Isotope Dilution Quantification of a Tryptic Peptide. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2024, 59, e5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicatti, M.; Guandalini, L.; Dei, S.; Floriddia, E.; Teodori, E.; Traldi, P.; Bartolucci, G. The Power of Energy-Resolved Tandem Mass Spectrometry Experiments for Resolution of Isomers: The Case of Drug Plasma Stability Investigation of Multidrug Resistance Inhibitors. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2016, 30, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicatti, M.; Guandalini, L.; Dei, S.; Floriddia, E.; Teodori, E.; Traldi, P.; Bartolucci, G. Energy Resolved Tandem Mass Spectrometry Experiments for Resolution of Isobaric Compounds: A Case of Cis/Trans Isomerism. Eur J Mass Spectrom (Chichester) 2016, 22, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menicatti, M.; Pallecchi, M.; Ricciutelli, M.; Galarini, R.; Moretti, S.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S.; Lucarini, S.; Caprioli, G.; Bartolucci, G. Determination of Coeluted Isomers in Wine Samples by Application of MS/MS Deconvolution Analysis. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2020, 55, e4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotti, S.; Menicatti, M.; Pallecchi, M.; Bartolucci, G. Tandem Mass Spectrometry Approaches for Recognition of Isomeric Compounds Mixtures. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2023, 42, 1244–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallecchi, M.; Lucio, L.; Braconi, L.; Menicatti, M.; Dei, S.; Teodori, E.; Bartolucci, G. Isomers Recognition in HPLC-MS/MS Analysis of Human Plasma Samples by Using an Ion Trap Supported by a Linear Equations-Based Algorithm. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 11155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallecchi, M.; Braconi, L.; Menicatti, M.; Giachetti, S.; Dei, S.; Teodori, E.; Bartolucci, G. Simultaneous Degradation Study of Isomers in Human Plasma by HPLC-MS/MS and Application of LEDA Algorithm for Their Characterization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 13139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicatti, M.; Pallecchi, M.; Bua, S.; Vullo, D.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Ghelardini, C.; Carta, F.; Supuran, C.T.; Bartolucci, G. Resolution of Co-Eluting Isomers of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Conjugated to Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors from Plasma in Liquid Chromatography by Energy-Resolved Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2018, 33, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellumori, M.; Pallecchi, M.; Zonfrillo, B.; Lucio, L.; Menicatti, M.; Innocenti, M.; Mulinacci, N.; Bartolucci, G. Study of Mono and Di-O-Caffeoylquinic Acid Isomers in Acmella Oleracea Extracts by HPLC-MS/MS and Application of Linear Equation of Deconvolution Analysis Algorithm for Their Characterization. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memboeuf, A.; Jullien, L.; Lartia, R.; Brasme, B.; Gimbert, Y. Tandem Mass Spectrometric Analysis of a Mixture of Isobars Using the Survival Yield Technique. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, A.; Boqué, R.; Jeanne Dit Fouque, D.; Memboeuf, A. Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry and Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy for Purity Assessment of a Synthetic Peptide Cyclised by Intramolecular Huisgen Click Chemistry. Methods and Protocols 2024, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne Dit Fouque, D.; Maroto, A.; Memboeuf, A. Purification and Quantification of an Isomeric Compound in a Mixture by Collisional Excitation in Multistage Mass Spectrometry Experiments. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 10821–10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne Dit Fouque, D.; Lartia, R.; Maroto, A.; Memboeuf, A. Quantification of Intramolecular Click Chemistry Modified Synthetic Peptide Isomers in Mixtures Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry and the Survival Yield Technique. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, 5765–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeanne Dit Fouque, D.; Maroto, A.; Memboeuf, A. Internal Standard Quantification Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry of a Tryptic Peptide in the Presence of an Isobaric Interference. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 14126–14130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroto, A.; Fouque, D.J. dit; Lartia, R.; Memboeuf, A. LC-MS Accurate Quantification of a Tryptic Peptide Co-Eluted with an Isobaric Interference by Using in-Source Collisional Purification. Anal Bioanal Chem 2023, 415, 7211–7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paizs, B.; Suhai, S. Fragmentation Pathways of Protonated Peptides. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2005, 24, 508–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleiholder, C.; Osburn, S.; Williams, T.D.; Suhai, S.; Van Stipdonk, M.; Harrison, A.G.; Paizs, B. Sequence-Scrambling Fragmentation Pathways of Protonated Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17774–17789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, D.L.; Vandeginste, B.G.M.; Buydens, L.M.C.; De Jong, S.; Lewi, P.J.; Smeyers-Verbeke, J. Handbook of Chemometrics and Qualimetrics: Part A; Elsevier: Amsterdam. The Netherlands, 1997; ISBN 0-444-89724-0. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2022). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL Https://Www.R-Project.Org/.

- RStudio Team (2022). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL Http://Www.Rstudio.Com/.

- Kucheryavskiy, S. Mdatools – R Package for Chemometrics. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2020, 198, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).