1. Introduction

Impurities in synthetic peptides are rarely discussed in detail. Scientists with less experience in analytical chemistry and organic synthesis often take the purity of a commercial product as granted and may not consider impurities at all. Others assume that a low percentage of a byproduct should be irrelevant

per se, which may be not the case in biomedicine, where minute amounts of unwanted constituents may cause strong side effects, such as allergic reactions. In the case of pre-clinical or clinical studies and toxicity tests, such trace compounds can lead to the failure of a highly valuable drug or other active substance. The economic damage of such a misleading result can be enormous. Hence, in any biochemical or biomedical experiment, the purity of the used reagents and test materials need to be characterized and unexpected compounds should be examined as detailed as possible. Obviously, such examinations are often disregarded due to time or financial constraints. However, many scientists are not aware of the risks associated with such a hasty procedure. Additionally, some users may be unaware of the limitations associated with the analytical methods used for purity determination. This can lead to the misinterpretation of purity specifications presented in a product data sheet, resulting in a significant information gap [

1]. On the other hand, additional purity examinations can be very laborious, and hence they are rarely performed. Therefore, we proposed a fast and easy approach for the analysis of peptide pools and other products containing synthetic peptides. This involves the execution of a state-of-the-art UHPLC separation combined with UV detection and subsequent or parallel high-resolution mass-spectrometry, for example with an orbitrap or TOF-MS system. This approach leads to a robust information about the relative quantity of a peptide and the confirmation of the chemical identity. This can be a sufficient characterization of a commercial product in the context of a quality control process. Nevertheless, such powerful analytical systems can deliver much more information as those mentioned above. In this paper, we reexamined chromatograms and mass-spectra of a study conducted for the quality control of a typical peptide pool, known as CEF, which nominally consists of 32 peptides with a length of 8 to 12 amino acids (

Table 1). By utilizing extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) with a maximum mass tolerance of 5 ppm, a targeted search was conducted for frequently occurring peptide-related impurities. This search included oxidized peptides, peptides containing cyclized amino acid residues and their derivatives, truncation sequences resulting from pyroglutamate formation during synthesis, and known deletion peptides identified from individual peptide measurements. An automated approach including algorithms known from non-target analysis seems to be lacking today, which obviously would facilitate this type of impurity analysis in the future, even for the less experienced scientist.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

The CEF peptide pool consists of 32 peptides derived from specific HLA class I-restricted T cell epitopes associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and influenza virus. Due to its relevance, it is available from several manufacturers. Our samples have been described in more detail in our previous paper [

4]. Peptide 5 (CLGGLLTMV, purity 95.2%, EP08605), peptide 20 (ELRSRYWAI, purity 95.1%, EP08620) and, peptide 23 (QAKWRLQTL, purity 90.9%, EP08623) were acquired from Peptides & Elephants GmbH, Hennigsdorf, Germany. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, purity > 99.5%, 85183) was sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies GmbH. Acetonitrile (ACN, LC-MS grade, 2697.2500) was obtained from Th. Geyer GmbH & Co. KG. Helium 6.0 (10100530) was purchased from Linde AG. The LTQ ESI positive ion calibration solution (purity > 99.5%, 88322) was acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH. Ammonium bicarbonate (ABC, purity > 99.0%, 09832) was obtained from Fluka. Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP, purity = 98%, AB121644) was purchased from ABCR GmbH. Iodoacetic acid (IAC, purity > 97%, 211794) was sourced from J&K Scientific. Iodoacetamide (purity ≥ 99%, I1149) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium hydroxide (purity ≥ 98%, 1372.1000) was acquired from Th. Geyer GmbH & Co. KG. Water was purified using an Ultra-Pure Water System from Millipore Co., with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm.

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. Impurity Identification

CEF Peptide Pool

The lyophilized CEF peptide pool sample (0.8 mg) was stored at −20 °C and allowed to equilibrate at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes prior to use. It was dissolved in 50 µL of ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v) and then in 50 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) to create a stock solution of 8 µg/µL (approximately 0.25 µg/µL per peptide). Both solvents were degassed by sonication (45 kHz, 15 min, RT). Following a 15-minute equilibration period, 20 µL of the stock solution were diluted with 180 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v), achieving a final concentration of 0.8 µg/µL, which corresponds to approximately 0.025 µg/µL per peptide. After centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min, RT), 180 µL of the resulting supernatant was transferred into an amber HPLC glass vial containing a 200 µL glass insert. The solvents used for the peptide pool were also employed in the preparation of blank samples.

A 5% ACN blank solution was prepared by diluting 100 µL of a 1:1 mixture of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) and ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v) with 900 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v). Following centrifugation at 2000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature, 800 µL of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial.

Peptide 20 and 23

Lyophilized peptides 20 (ELRSRYWAI, 1 mg) and 23 (QAKWRLQTL, 1 mg) were stored at −20 °C and allowed to equilibrate at room temperature for 30 minutes before use. They were then dissolved in 500 µL of ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v), followed by the addition of 500 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) to create a stock solution with a concentration of 1 µg/µL. Prior to use, both solvents were degassed by sonication at 45 kHz for 15 minutes at room temperature. A volume of 20 µL of the peptide stock solution was diluted with 750 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) and 30 µL of ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v), resulting in a final concentration of 0.025 µg/µL. After centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min, RT), 700 µL of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial.

A blank solution was prepared by diluting 100 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) with 100 µL of ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v). Subsequently, 100 µL of this mixture was further diluted by adding 900 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v), resulting in a 5% ACN blank solution. After centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min, RT), of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial.

2.2.2. Alkylation of Cysteine-Residues

IAA-alkylation of Peptide 5

Lyophilized peptide 5 (CLGGLLTMV, 1 mg) was stored at −20 °C and equilibrated at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to use. It was dissolved in 62.5 µL of ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v) and then in an additional 62.5 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) to create an 8 µg/µL stock solution. Before use, both solvents were degassed by sonication at 45 kHz for 15 minutes. After a 15-minute equilibration period, the stock solution was aliquoted into 10 µL portions and stored at −20 °C. Before LC-MS analysis, aliquots were thawed for 30 minutes, diluted with 355 µL of 1 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0), and 35 µL of ACN to achieve a final concentration of 0.2 µg/µL. A total of 100 µL of this solution was combined with 100 µL of a 10 mM TCEP solution (dissolved in 1 M ABC buffer, pH 8.0) and shaken for 30 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, 100 µL of the reduced peptide 5 solution was mixed with 100 µL of a 10 mM IAA solution (dissolved in 1 M ABC buffer, pH 8.0) and shaken for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. To prevent overalkylation, 100 µL of the alkylated peptide 5 was quenched with 100 µL of the previously used 10 mM TCEP solution (dissolved in 1 M ABC buffer, pH 8.0) and shaken for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min, RT), 180 µL of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial with a 200 µL glass insert.

A blank solution was prepared by diluting 100 µL of a 0.05% (v/v) water/TFA solution with 100 µL of a 0.05% (v/v) ACN/TFA solution. Subsequently, 100 µL of this mixture was further diluted by adding 900 µL of the previously used ABC buffer (1 M, pH 8.0). After centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min, RT), 800 µL of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial.

IAC-Alkylation of Peptide 5

Lyophilized peptide 5 (CLGGLLTMV, 1 mg) was stored at −20 °C and equilibrated at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to use. It was dissolved in 62.5 µL of ACN/TFA 0.05% (v/v) and then in 62.5 µL of water/TFA 0.05% (v/v) to create a stock solution with a concentration of 8 µg/µL. Before use, both solvents were degassed by sonication at 45 kHz for 15 minutes at room temperature. After a 15-minute equilibration period, the stock solution was divided into 10 µL aliquots and stored at −20 °C. Prior to LC-MS analysis, aliquots were thawed for 30 minutes. Subsequently, one aliquot was diluted with 355 µL of 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0) and 35 µL of ACN, resulting in a final peptide 5 concentration of 0.2 µg/µL. A volume of 100 µL of this solution was combined with 100 µL of a 2.2 mM TCEP solution (dissolved in 0.1 M ABC buffer, pH 8.0) and shaken for 30 minutes. Following this, 100 µL of the reduced peptide 5 solution was mixed with 100 µL of a 4.4 mM IAC solution (in 0.1 M ABC buffer, pH 8.0) and shaken for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Finally, 100 µL of the alkylated peptide 5 solution was diluted with 100 µL of the previously used ABC buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0), and after centrifugation, 180 µL of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial containing a 200 µL glass insert.

A blank solution was prepared by diluting 100 µL of a 0.05% (v/v) water/TFA solution with 100 µL of a 0.05% (v/v) ACN/TFA solution. Subsequently, 100 µL of this mixture was further diluted by adding 900 µL of the previously used ABC buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0). After centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min, RT), 800 µL of the supernatant was transferred to an amber HPLC glass vial.

2.3. UHPLC-HRMS Analysis

Samples were analyzed using a Thermo Scientific UltiMate 3000 RSLC-nano UHPLC System coupled with a Thermo Fisher Scientific Exactive Orbitrap High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer. The autosampler temperature was maintained at 4 °C. Chromatographic separation was achieved with an Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 column (100 Å, 2 µm, 0.3 mm × 150 mm) in conjunction with an Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 trap precolumn (100 Å, 5 µm, 0.3 mm × 5 mm), both sourced from Thermo Scientific. The mobile phases for chromatography consisted of 0.05% (v/v) TFA in water (A) and 0.04% (v/v) TFA in acetonitrile (B). The mobile phases were degassed by purging with helium 6.0 for 5 min. Peptides were eluted using the following gradient: 4% B isocratic for 4 min (6 µL/min), followed by a linear increase to 44% B over 100 min (6 µL/min), then a linear increase to 95% B over 0.1 min (6 µL/min), held at 95% B for 6 min (10 µL/min), returned to initial conditions within 0.1 min (10 µL/min), and maintained at a flow rate of 10 µL/min for 11 minutes, followed by 6 µL/min for 1 minute. For the stability studies of IAC-alkylated and IAA-alkylated peptide 5, as illustrated in Figure 9, a shorter HPLC method was employed. This method differed only in the gradient, which increased linearly from 4% B to 56% B over 26 minutes (6 µL/min) and then to 95% B in 1 minute (6 µL/min). The column oven temperature was set to 55 °C. The injection volume was 1 µL, conducted in full loop mode, with a flush volume of 5 µL, a flush volume 2 of 3 µL, and a loop overfill of 2 µL. UV detection was performed at 214 nm. Prior to analyzing the peptides in the mass spectrometer, the eluate was split in a 1:10 ratio using a T-piece. Subsequent electrospray ionization was conducted in positive mode (ESI+). The mass spectrometer settings were configured as follows: spray voltage at 4.5 kV, capillary voltage at 30 V, capillary temperature at 320 °C, tube lens voltage at 80 V, skimmer voltage at 24 V, and the scan range from 200 to 1800 m/z. The MS scans were acquired with ultra-high resolution (100,000 at 200 m/z) at a scan rate of 1 Hz, a balanced automatic gain control (AGC) target (1 × 106), and a maximum injection time (IT) of 500 ms. External mass calibration using LTQ ESI positive ion calibration solution provided a mass accuracy of <5 ppm. Data acquisition was performed using Xcalibur 2.2 with Dionex Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Link (DCMSLink).

2.4. Data Processing

Analysis of mass spectrometry data was performed using Xcalibur 2.2. Theoretical exact masses and m/z values for the peptides and peptide-related impurities were calculated using the online tool Chem-Calc [

2]. Experimental m/z values were validated by employing extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) with a maximum mass tolerance of 5 ppm.

UV spectrometry data were analyzed using Chromeleon 7.2.10. Baseline correction was achieved by subtracting the blank run injection. A baseline with specified start and end points was established. For peak detection and integration, a minimum area threshold was defined. Peak areas were measured using the perpendicular drop method.

3. Results

3.1. Impurity Identification

3.1.1. Deletion Peptides

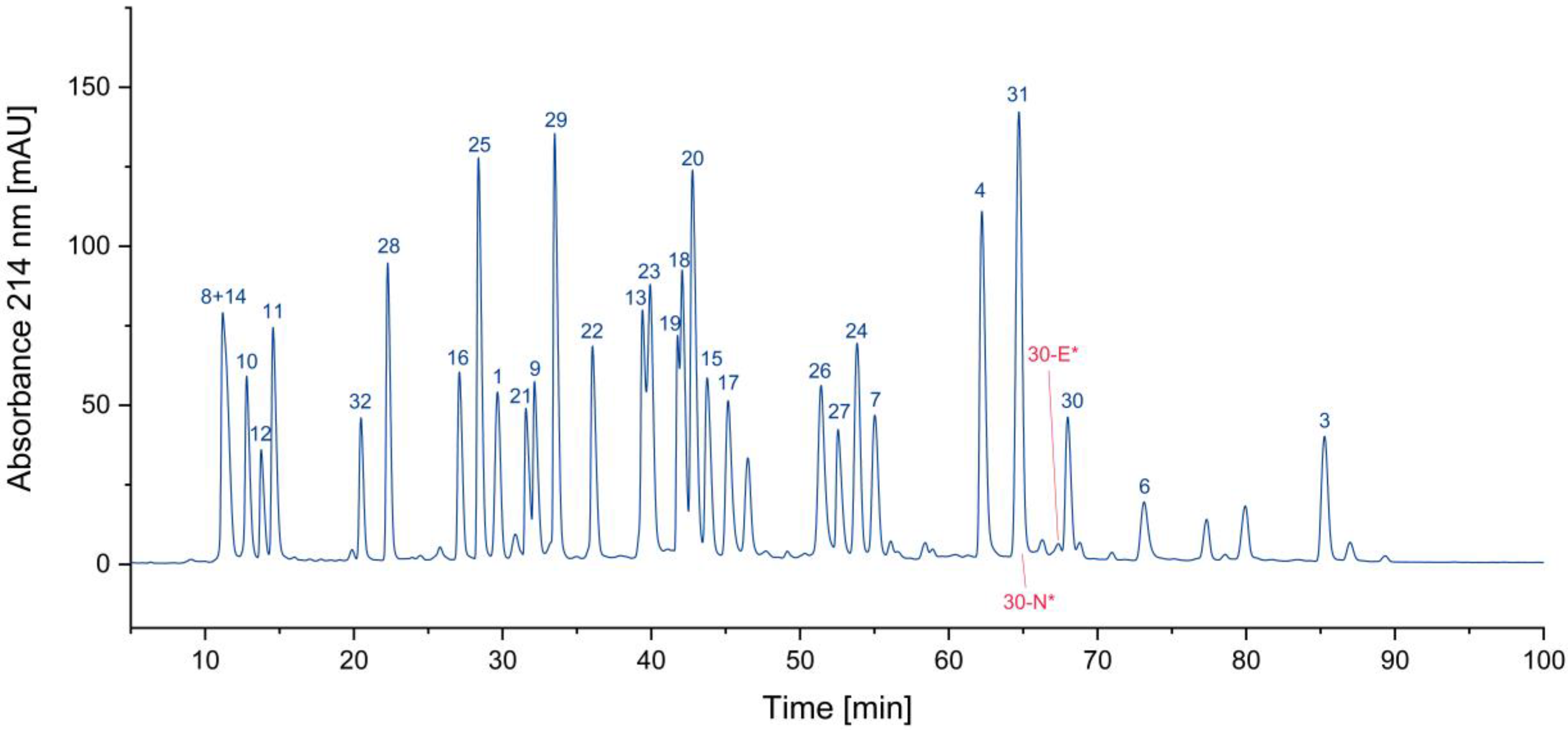

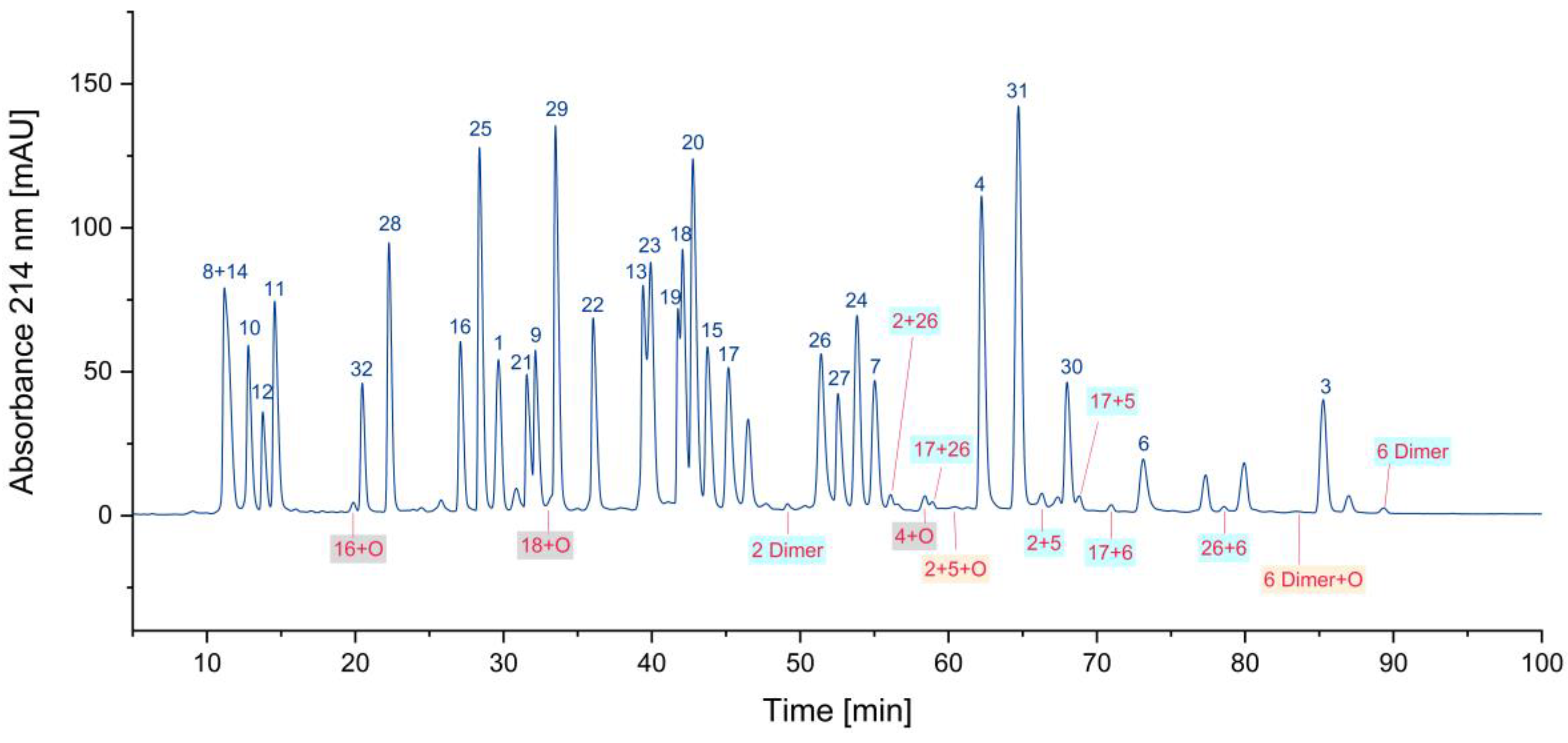

One of the most obvious impurities in synthetic peptides are deletion peptides. Since the synthesis of peptides is performed amino acid by amino acid, some coupling steps might be incomplete, e.g., due to steric hindrance. This is often overcome by repetition of the respective coupling step if this issue is known. Furthermore, uncoupled amino termini can be blocked by acetylation, to avoid further growth, since truncated peptides can be removed easier than peptides differing only by one amino acid. These impurities can nearly always be traced back to issues during the synthesis and subsequent insufficient purification. In the case of this sample of the CEF pool, only very small traces of deletion peptides could be detected. This indicates a highly optimized synthesis process and/or an efficient purification of the individual peptides. In

Figure 1, two examples of deletion peptides are indicated.

3.1.2. Cyclized Amino Acid Residues and Their Derivatives

A known side reaction is also the formation of cyclized N-termini of glutamine (Q, Gln) and glutamic acid (E, Glu). In these cases, ammonia or water is released by the condensation reaction. Both reactions lead to the same product with a N-terminal pyroglutamate residue (

Figure 2a).

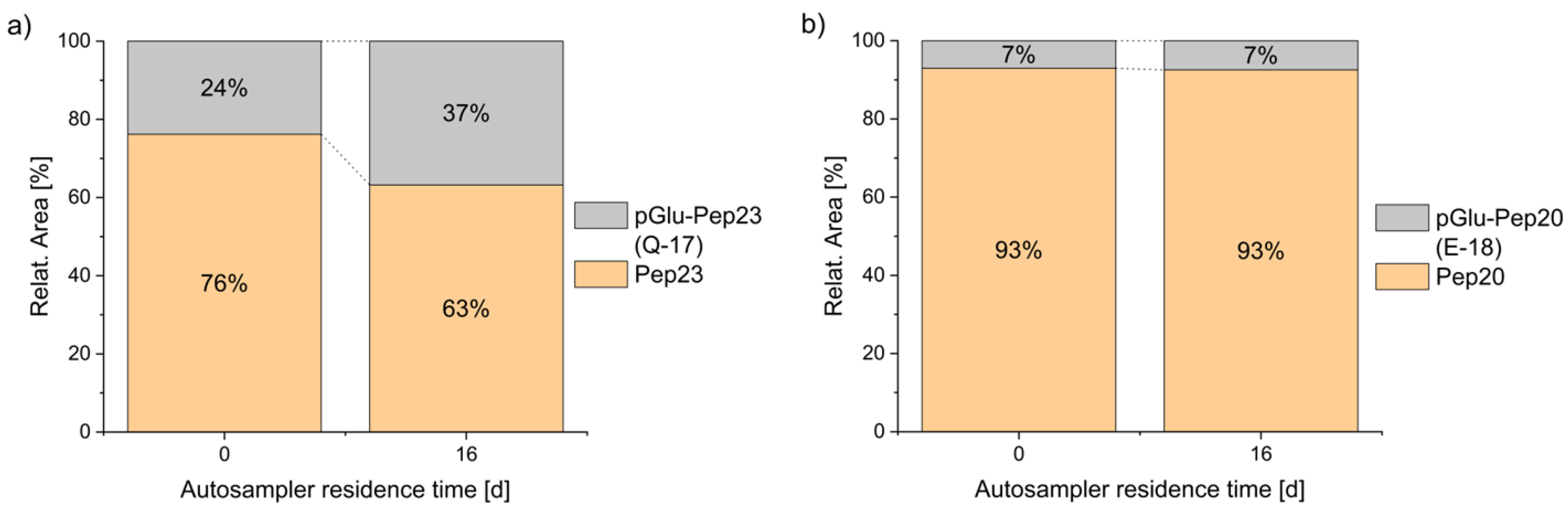

The formation of pyroglutamate can significantly influence the properties of a peptide. For example, aminopeptidases are usually not able to cleave this terminal amino acid and the positive charge of the N-terminus is lost. Additionally, it was shown that the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity of pyroglutamyl peptides may decrease compared to that of unmodified peptides [

5]. In all cases, where a glutamic acid or a glutamine was expected at the N-terminus, the formation of some pyroglutamate peptide was detected. In a solvent consisting of water with 5% of acetonitrile and 0.05% of trifluoroacetic acid, terminal glutamic acid was fairly stable for several days, in contrast to glutamine, which significantly degraded to pyroglutamate during 16 days of storage (

Figure 3). Complete datasets are presented in

Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials. A similar behavior was also reported in the literature before [

6]. A comparison of the relative proportions of the pyroglutamate species (pGlu-Pep23: 24%; pGlu-Pep20: 7%) with the purity of the individual peptides, as indicated by the manufacturer (Peptide 23: 90.9%; Peptide 20: 95.1%), suggests that, in addition to the pyroglutamate present from the initial stages of synthesis and purification, storage and/or sample preparation are likely contributing factors to the observed pyroglutamate content.

Aspartimides (

Figure 2b) are formed from aspartic acid (D, Asp) through a cyclization process that involves the loss of water [

7]. They are typically considered a side reaction that occurs during synthesis. Particularly, the sequence -DG- has been shown to be sensitive to this type of reaction. This could be confirmed in our study. All ten peptides with aspartic acids without a subsequent glycine were stable under the selected conditions and only one, with the sequence -DG- showed the formation of the aspartimide. It should be noted that this mechanism also leads to epimerization and a further rearrangement of the amino acid into the iso form, both of which are not easily identified by MS. Furthermore, the aspartimide could be opened by the reagent piperidine during synthesis, leading to another epimerized byproduct. However, these products could not be found in our sample(s). Similar to the loss of water in aspartic acid (Asp), the deamidation of asparagine (Asn) also results in the formation of aspartimide [

8], which can subsequently hydrolyze to aspartic acid and to isoaspartic acid (

Figure 2c).

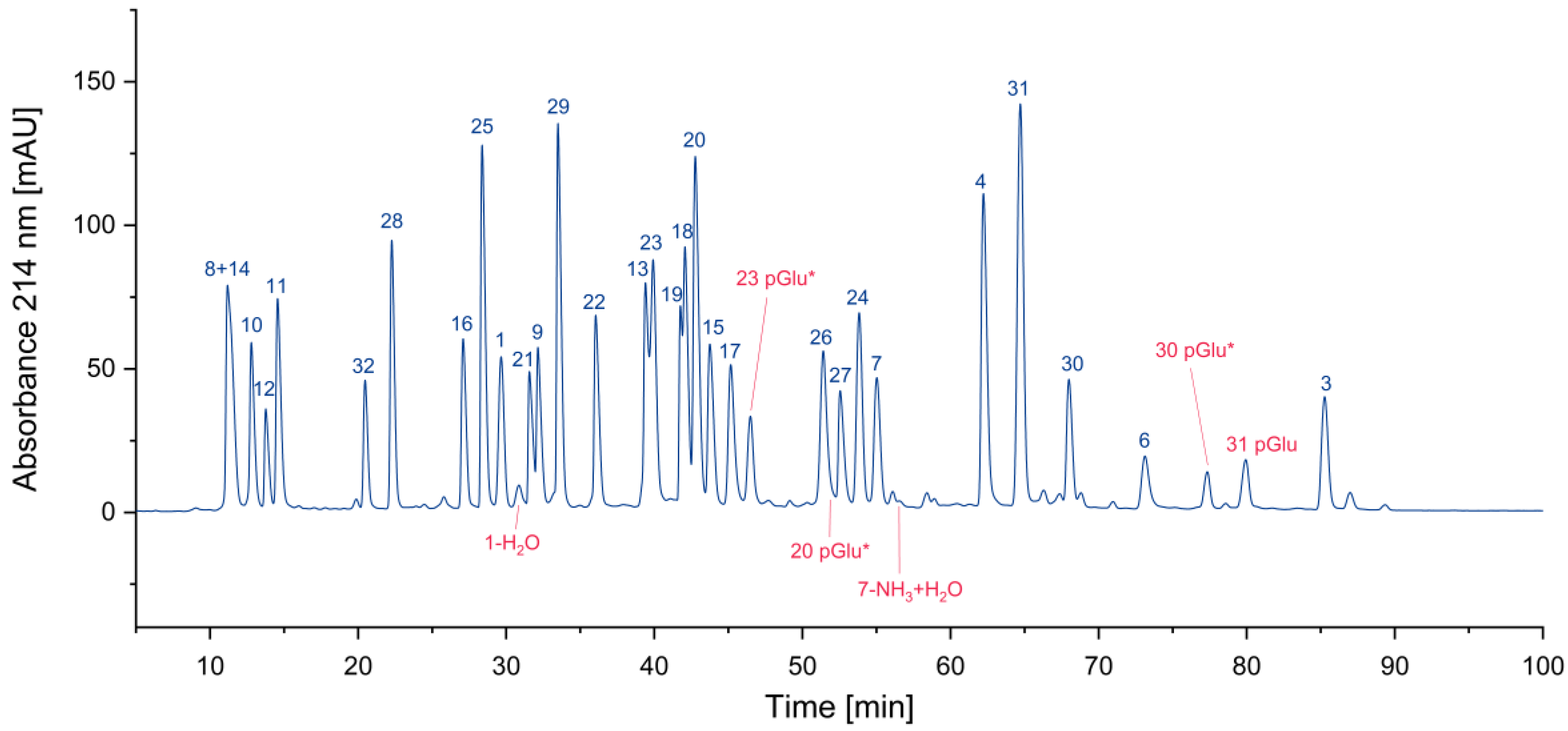

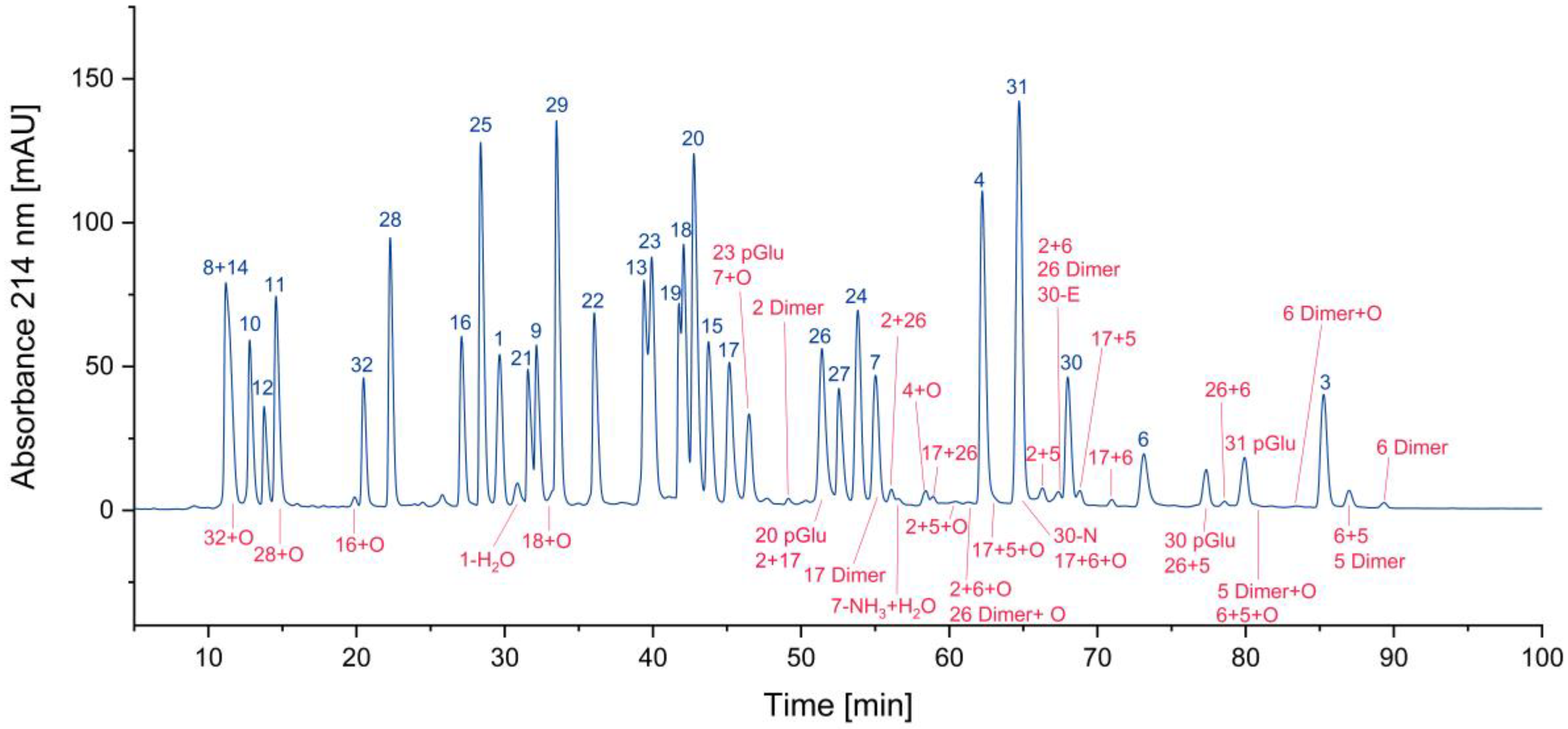

In

Figure 4, all cyclized peptides, including those formed through a cyclic intermediate (deamidation), are indicated in red. Most of them are pyroglutamate-terminated peptides, only one is an aspartimide by-product, while another results from the deamidation of asparagine. They are separately listed in

Table 2 .

3.1.3. Oxidized Peptides

In an oxygen-containing atmosphere, oxidation is a frequent reaction. Particularly, cysteine and methionine are sensitive to oxidative processes. A rarely examined reaction is the unwanted formation of cysteine dimers, since most protocols for peptide analysis include an alkylation step to avoid this side reaction. In proteins, cysteines are usually “protected” by the formation of defined disulfide bridges, which can be either analyzed in their native form, or opened by reduction with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) or dithiothreitol (DTT), and subsequent alkylation. In this way, the formation of cysteine dimers can be prevented. However, it should be borne in mind that each reduction step destroys the information of pre-existing disulfide bonds. In peptide pools, however, such a protection by alkylation or disulfides is not present and hence, directly after the cleavage of the peptides from the solid phase and deprotection of the cysteine side chain, the formation of homodimers (particularly before mixing of the peptides) and heterodimers (likely after the combination of the peptides to the pool) can occur in significant amounts. For the five peptides containing cysteines, 23 dimers (including methionine-oxidized products) could be tentatively identified.

Oxidized peptides with a methionine sulfoxide can be found frequently. In our peptide pool sample, all methionine-containing peptides were also found in their oxidized form. For peptide 16, about 8% of the compound was found as the sulfoxide. Further oxidation was not significant for 77 hours in the autosampler. In

Figure 5, oxidized peptides are labeled: Cysteine dimers in yellow, methionine sulfoxides in grey, and dimers with an additional oxygen in orange. Only a selected number of oxidized peptides are highlighted in the figure.

3.1.4. Overview

In

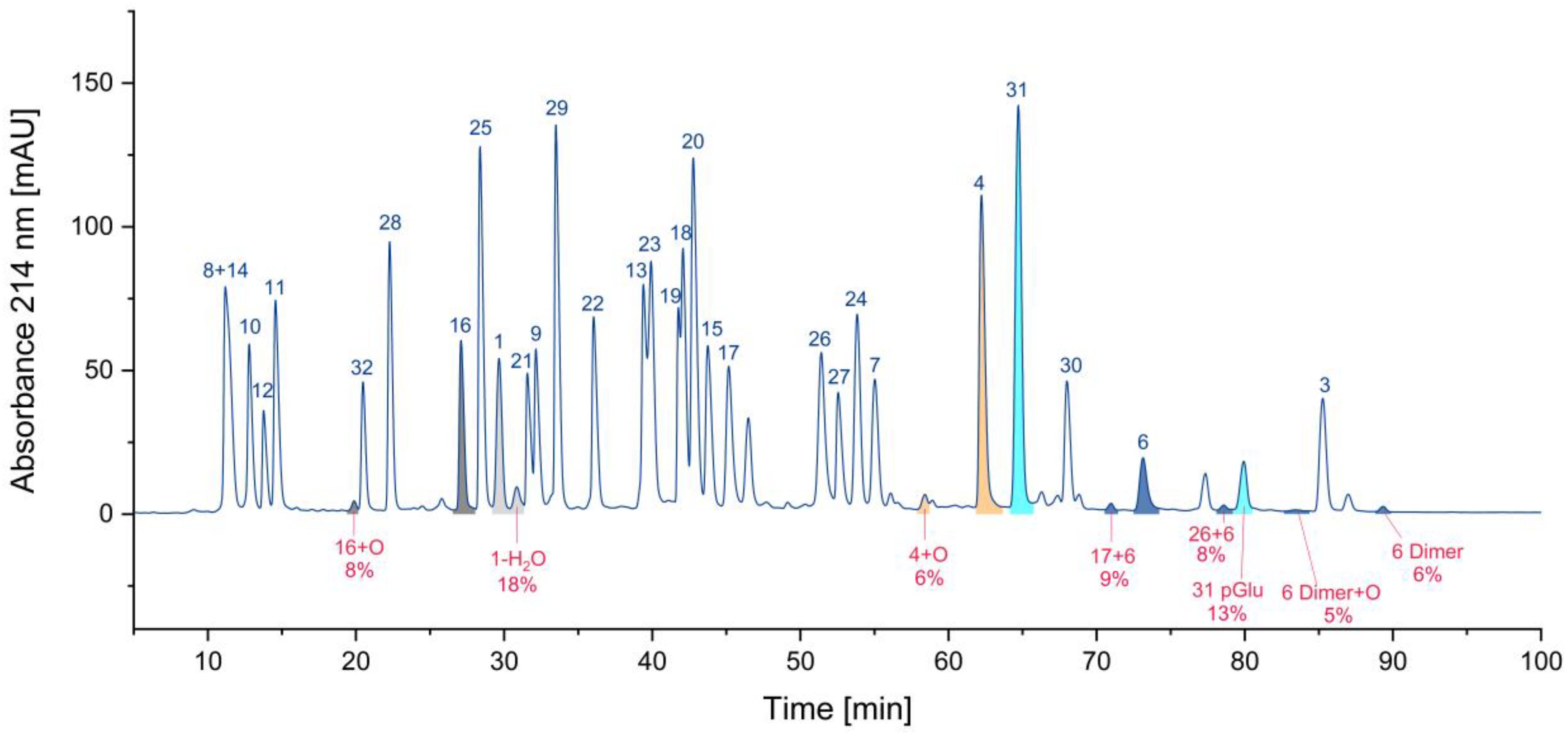

Figure 6, all identified impurities are labeled in red. It is obvious that the 37 additional peptides in addition to the 32 expected peptides, complicate the analysis of the peptide pool considerably by increasing the number of overlapping peaks. In addition, the presence of unwanted byproducts might lead to unexpected results when the peptide pool is used in a sensitive experimental setting. Hence, it might be concluded that the chemical composition of peptide pools should be optimized to reduce the number of additional products. Another option might be the improved purification of the synthesized peptides and the subsequent compliance of strict storage conditions, such as freezing at –80°C or liquid nitrogen. It depends on the user, which approach may be considered more feasible. The most trivial option could be to accept the impurities as "unavoidable" and to hope that the experiment will not be affected by the small percentage of additional components.

Considering the number of impurities of a specific class (

Figure S2,

Supplementary Materials), hetero- and homodimers of cysteine-containing peptides (23) are by far the most frequent. Also present are peptides with methionine sulfoxide (6) and N-terminal pyroglutamates (4). Deletion peptides (2), aspartimides (1), and deamidation products (1) are quite rare. Nevertheless, the number of impurities may be not the most relevant parameter. Assuming that the parent peptide is the only active one and the byproduct is inactive, the residual percentage of the parent peptide would be interesting. Hence, we calculated these percentages based on the UV area for some peptides. In

Figure 7, the areas of various peptides and their corresponding impurities are presented in the chromatogram. The pairs of parent peptides and their corresponding impurities are shown in the same color.

For cysteine dimers, this calculation is relatively inaccurate, due to the formation of numerous products, some of which may be hidden in overlapping peaks. Consequently, the residual percentage of the parent peptide may be overestimated, if no reference measurement is available. In the worst case, only 71% of the parent peptide remained, while other calculations indicated that 82%, 87%, 92%, and 94% of the parent peptide were still present. (

Table 3). For peptide pools, such as the CEF peptide pool, where certain peptides are present in significant excess [

9], a reduced concentration of the parent peptide may be irrelevant.

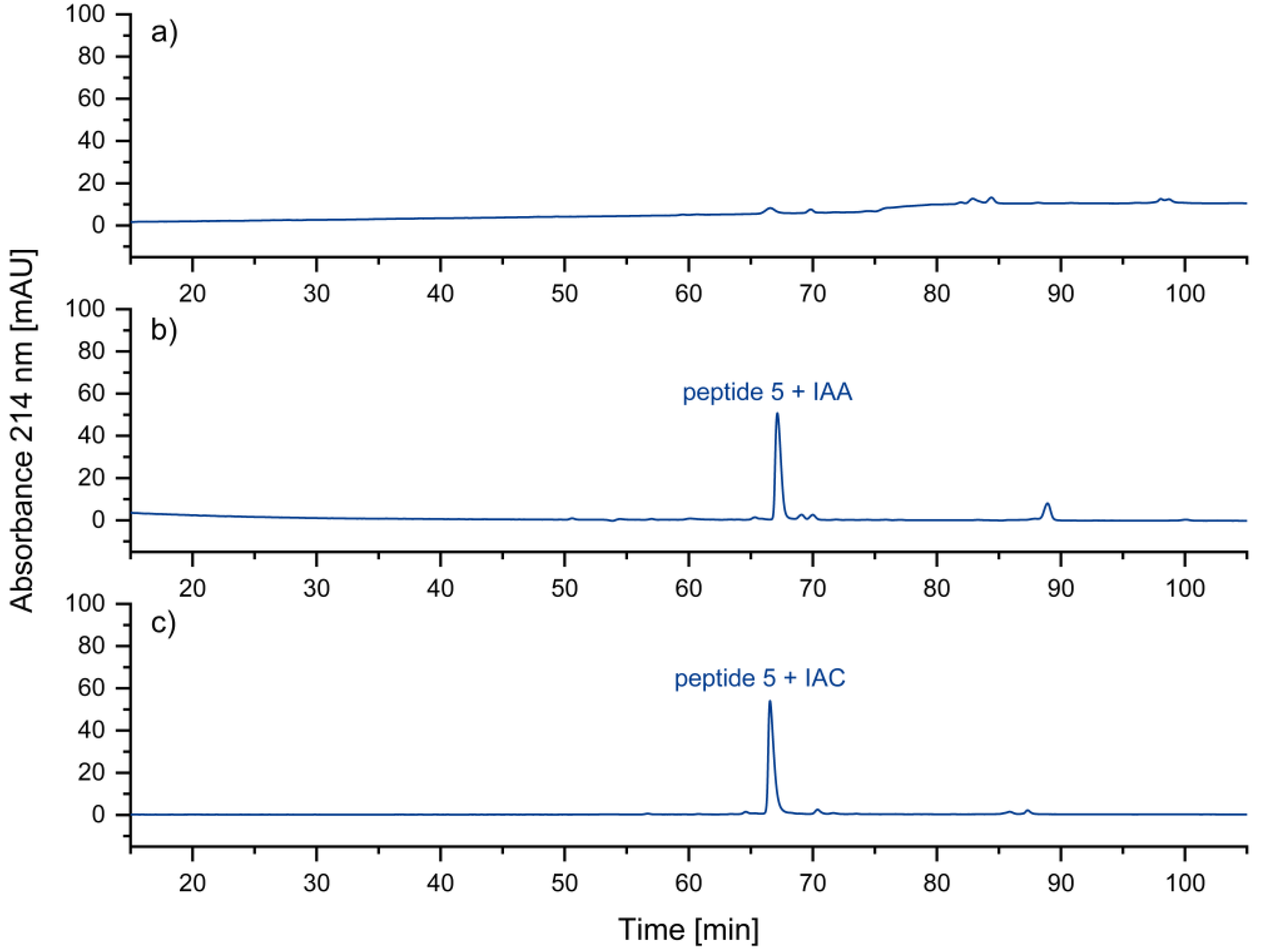

3.2. Alkylation of Cysteine Residues

In the fast approach for the quality control of peptide pools [

4] the reduction and the alkylation steps are omitted for the sake of simplicity and speed. However, it could be shown that peptides with free cysteine residues may display some unwanted effects during the chromatography [

10]. The corresponding peptide peak may be barely visible under certain separation conditions (

Figure 8a). Peptides with non-terminal cysteines also showed a tendency for low recovery. These issues could be removed by alkylation with iodoacetamide (IAA) or iodoacetic acid (IAC). In

Figure 8 b and c, this effect is shown. We assume strong interactions of the N-terminal thiol group with metal or other surfaces. The thioether formed after alkylation seems to be less prone to such interactions.

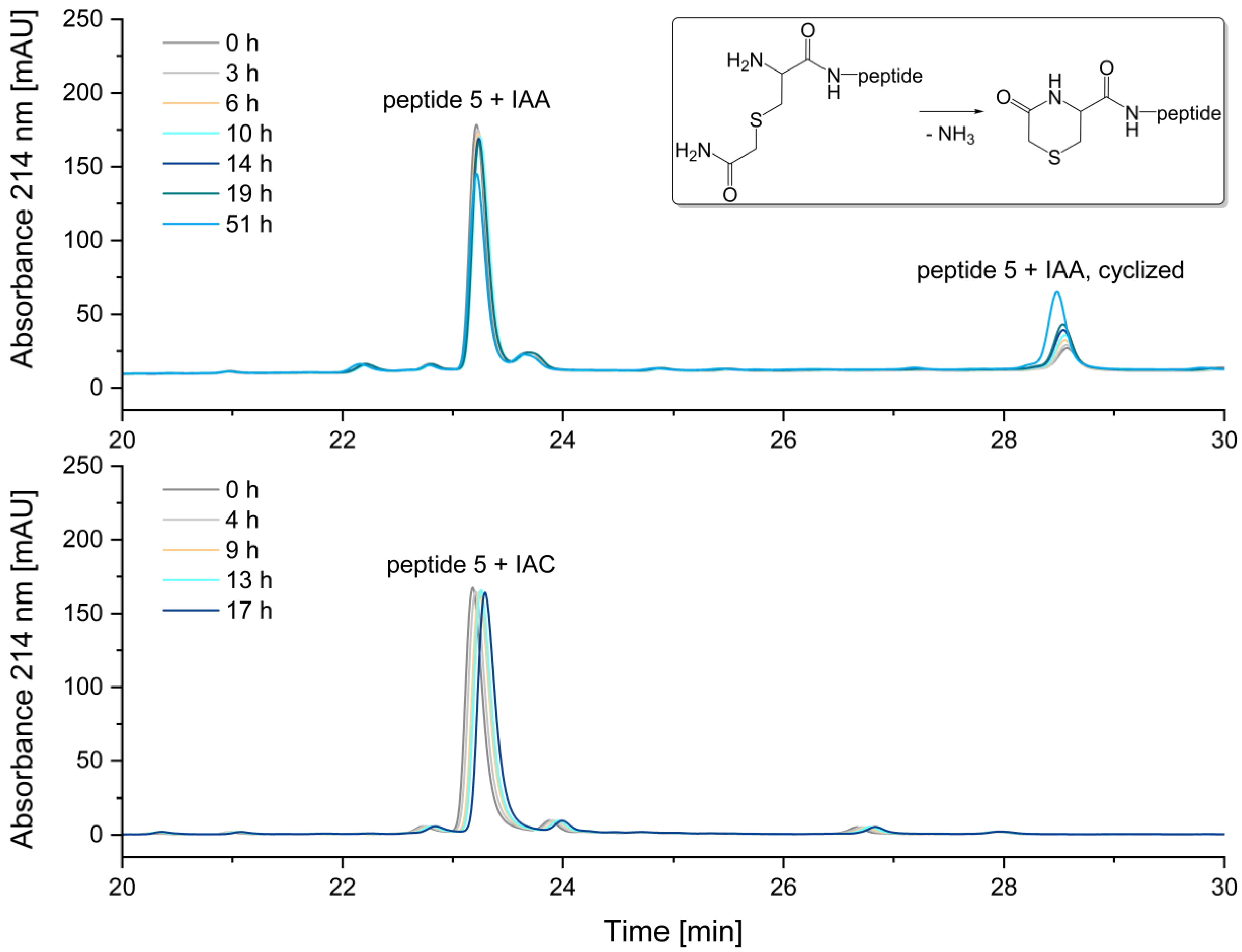

A comparison of the two alkylation reagents revealed that the alkylation reagent IAA, which is most used in proteomic studies [

11], has a significant disadvantage compared to IAC: when alkylating an N-terminal cysteine, the resulting reaction product is unstable (

Figure 9).

The instability of the IAA-alkylated peptide 5 is attributed to the cyclization of the alkylated cysteine at the N-terminus. In this process, the N-terminal carbamidomethylated cysteine reacts to form an N-terminal 5-oxohydro-1,4-thiazin-3-carboxylic acid, as indicated by a mass difference of -17 Da [

12,

13,

14]. After 51 hours in the autosampler, the relative peak area of the peptide alkylated with iodoacetamide decreased by 18%. In contrast, the alkylation of peptide 5 with iodoacetic acid (IAC) resulted in a stable peptide, with no significant degradation of the N-terminal carboxymethyl-cysteine observed. The corresponding peak areas are illustrated in

Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials. Therefore, in the alkylation of N-terminal cysteines, the reagent iodoacetic acid (IAC) is preferable.

4. Discussion

Research on peptide impurities in synthetic products is rarely carried out and therefore knowledge is limited, especially for complex products such as peptide pools. In this work, we used data obtained by high-resolution mass spectrometry to tentatively assign structural data to unknown peaks in a reversed-phase chromatogram. The results do not claim to be comprehensive, but are focused on impurities, which seem to be frequent and occurring in relevant concentrations. Perhaps the most interesting finding is the occurrence of numerous homo- or hetero-dimers resulting from unprotected cysteine residue. This result should not be ignored, as the formation of these impurities is to be expected and cannot be completely avoided. Retrospectively, it is quite surprising that this issue is largely disregarded in most papers. The loss of peptides with N-terminal cysteines was striking. This was observed in analytical methods without cysteine alkylation. Additionally, the formation of N-terminal pyroglutamyl residues was observed with relative frequency. This aspect is also significant in the context of biological activity, as the positive charge of the terminus is lost and all processes that depend on a free N-terminus could be strongly influenced. For example, Beck et al. [

5] demonstrated that CTL activity can be reduced by pyroglutamic peptides compared to their unmodified counterparts. A small proportion of certain deletion peptides was identified; however, their significance may be minimal due to their similar properties compared to the expected peptides and their low concentrations. Finally, only one instance of aspartimide formation and one instance of deamidation were detected. This is a positive outcome, as aspartimide typically leads to the formation of several isomers and other by-products that are difficult to distinguish.

5. Conclusions

First of all, awareness of impurities in peptide products should be raised. These products are used in various applications and therefore it is difficult for the manufacturer to make a final judgment as to whether the product is suitable for the intended purpose. This means that a quick quality control of the product should be carried out by the user [

4], regardless of whether the peptide pool has been freshly obtained from the manufacturer or the mixture has been stored in the laboratory for some time. Based on the protocol presented in this paper, the main impurities should be identified, and a brief risk analysis performed.

Nevertheless, avoidance strategies are almost always preferable to reduce the number and concentration of undesired compounds in the peptide pool.

Starting with the occurrence of hetero- or homodimers of cysteine-containing peptides, for example, various means could be considered:

Choice of different peptide sequences, avoiding any cysteines

Replacement of cysteine by a more stable amino acid, such as alanine or methylcysteine

Alkylation of the cysteines by iodoacetamide, iodoacetic acid or other known reagents. This would be particularly relevant in the case of analytical studies.

Addition of reductants, such as DTT, TECP, cysteine, glutathione, and others

Strict avoidance of any oxidant, such as oxygen by use of protecting gases, such as helium, argon or nitrogen during synthesis, purification, storage, transportation, and use

The occurrence of oxidized methionine could also be avoided by some of the previously mentioned approaches, particularly points 1, 2 and 5. The occurrence of pyroglutamate N-termini can be mitigated through N-acetylation or by avoiding the incorporation of glutamine and glutamic acid at the N-terminus of peptides. Similar approaches, such as the substitution or N-methylation of glycine, might be advisable in the (rare) case of an Asp-Gly sequence, which is highly prone to aspartimide formation and the generation of other by-products. Furthermore, the use of innovative protecting groups could provide a viable solution [

15]. Deamidation might be prevented by avoidance or substitution of asparagine and glutamine. Finally, the presence of deletion peptides could be prevented by improved synthesis protocols and better purification. It should be kept in mind that smaller amounts of a peptide can be purified on analytical (U)HPLC columns, which have a much better separation performance than preparative columns. In addition, by injecting smaller amounts of sample and sharply cutting the peptide peak in the fraction collector, the purity of the final product can generally be improved, of course at the expense of lower yield and higher costs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.W.; methodology, M.G.W.; validation, G.B.; formal analysis, G.B.; investigation, G.B.; resources, M.G.W.; data curation, G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.W.; writing—review and editing, G.B.; M.G.W.; visualization, G.B.; supervision, M.G.W.; project administration, M.G.W.; funding acquisition, M.G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the funding line of the Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung (BAM) MI-Ideen Typ 3 under the grant number Ideen_2016_15.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weller, M.G. The Protocol Gap. Methods and Protocols 2021, 4, 12. [CrossRef]

- Patiny, L.; Borel, A. ChemCalc: A Building Block for Tomorrow's Chemical Infrastructure. J Chem Inf Model 2013, 53, 1223-1228. [CrossRef]

- Currier, J.R.; Kuta, E.G.; Turk, E.; Earhart, L.B.; Loomis-Price, L.; Janetzki, S.; Ferrari, G.; Birx, D.L.; Cox, J.H. A panel of MHC class I restricted viral peptides for use as a quality control for vaccine trial ELISPOT assays. J Immunol Methods 2002, 260, 157-172. [CrossRef]

- Bosc-Bierne, G.; Ewald, S.; Kreuzer, O.J.; Weller, M.G. Efficient Quality Control of Peptide Pools by UHPLC and Simultaneous UV and HRMS Detection. Separations 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Bussat, M.C.; Klinguer-Hamour, C.; Goetsch, L.; Aubry, J.P.; Champion, T.; Julien, E.; Haeuw, J.F.; Bonnefoy, J.Y.; Corvaia, N. Stability and CTL activity of N-terminal glutamic acid containing peptides. J Pept Res 2001, 57, 528-538. [CrossRef]

- Gazme, B.; Boachie, R.T.; Tsopmo, A.; Udenigwe, C.C. Occurrence, properties and biological significance of pyroglutamyl peptides derived from different food sources. Food Sci Hum Well 2019, 8, 268-274. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, R.; White, P.; Offer, J. Advances in Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis. J Pept Sci 2016, 22, 4-27. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Moulton, K.R.; Auclair, J.R.; Zhou, Z.S. Mildly acidic conditions eliminate deamidation artifact during proteolysis: digestion with endoprotease Glu-C at pH 4.5. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1059-1067. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Moldovan, I.; Targoni, O.S.; Subbramanian, R.A.; Lehmann, P.V. How much of Virus-Specific CD8 T Cell Reactivity is Detected with a Peptide Pool when Compared to Individual Peptides? Viruses 2012, 4, 2636-2649. [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, O.J.; Weller, M.G.; Bosc-Bierne, G. Stabilization of N-terminal cysteines in HPLC-HRMS quality control of peptide pools. The Journal of Immunology 2023, 210, 159.109-159.109, doi: . [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Winter, D. Systematic Evaluation of Protein Reduction and Alkylation Reveals Massive Unspecific Side Effects by Iodine-containing Reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics 2017, 16, 1173-1187. [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, K.F.; Hoth, L.R.; Tan, D.H.; Borzillerl, K.A.; Withka, J.M.; Boyd, J.G. Cyclization of N-terminal S-carbamoylmethylcysteine causing loss of 17 Da from peptides and extra peaks in peptide maps. J Proteome Res 2002, 1, 181-187. [CrossRef]

- Krokhin, O.V.; Ens, W.; Standing, K.G. Characterizing degradation products of peptides containing N-terminal Cys residues by (off-line high-performance liquid chromatography)/matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization quadrupole time-of-flight measurements. Rapid Commun Mass Sp 2003, 17, 2528-2534. [CrossRef]

- Reimer, J.; Shamshurin, D.; Harder, M.; Yamchuk, A.; Spicer, V.; Krokhin, O.V. Effect of cyclization of N-terminal glutamine and carbamidomethyl-cysteine (residues) on the chromatographic behavior of peptides in reversed-phase chromatography. J Chromatogr A 2011, 1218, 5101-5107. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Farnung, J.; Baldauf, S.; Bode, J.W. Prevention of aspartimide formation during peptide synthesis using cyanosulfurylides as carboxylic acid-protecting groups. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Search for deletion peptides (*coelution with other peptides/impurities).

Figure 1.

Search for deletion peptides (*coelution with other peptides/impurities).

Figure 2.

Cyclization of amino acid residues and subsequent reactions: Reaction pathways for the formation of a) pyroglutamate, and b) aspartimide, as well as for c) deamidation.

Figure 2.

Cyclization of amino acid residues and subsequent reactions: Reaction pathways for the formation of a) pyroglutamate, and b) aspartimide, as well as for c) deamidation.

Figure 3.

Stability of N-terminal glutamine vs. glutamic acid during autosampler storage. Spontaneous cyclization of the N-terminal amino acid is faster for peptide 23 with glutamine (a) than of peptide 20 with glutamic acid (b), both in 5% ACN + 0.05% TFA at 4°C.

Figure 3.

Stability of N-terminal glutamine vs. glutamic acid during autosampler storage. Spontaneous cyclization of the N-terminal amino acid is faster for peptide 23 with glutamine (a) than of peptide 20 with glutamic acid (b), both in 5% ACN + 0.05% TFA at 4°C.

Figure 4.

Search for cyclized amino acid residues and their derivatives. (*coelution with other peptides).

Figure 4.

Search for cyclized amino acid residues and their derivatives. (*coelution with other peptides).

Figure 5.

Some oxidized peptides. Note: Only a few examples of the identified peptides are labeled in the chromatogram. Grey background: contain methionine sulfoxide, blue background: contain cysteine dimers (cystine), and orange background shows peptides with both types of oxidations.

Figure 5.

Some oxidized peptides. Note: Only a few examples of the identified peptides are labeled in the chromatogram. Grey background: contain methionine sulfoxide, blue background: contain cysteine dimers (cystine), and orange background shows peptides with both types of oxidations.

Figure 6.

Thirty-seven impurities were identified in the CEF peptide pool.

Figure 6.

Thirty-seven impurities were identified in the CEF peptide pool.

Figure 7.

Relative proportion of impurities and the corresponding parent peptides.

Figure 7.

Relative proportion of impurities and the corresponding parent peptides.

Figure 8.

UV chromatogram of a) the cysteine-containing peptide 5, b) iodoacetamide-alkylated peptide 5, c) iodoacetic acid-alkylated peptide 5. No peak is obtained for peptide 5 with free, N-terminal thiol group. Relative to the total peak areas (214 nm) of each chromatogram, with IAA a purity of 73 % was obtained, in contrast to 84 % with IAC.

Figure 8.

UV chromatogram of a) the cysteine-containing peptide 5, b) iodoacetamide-alkylated peptide 5, c) iodoacetic acid-alkylated peptide 5. No peak is obtained for peptide 5 with free, N-terminal thiol group. Relative to the total peak areas (214 nm) of each chromatogram, with IAA a purity of 73 % was obtained, in contrast to 84 % with IAC.

Figure 9.

Stability of alkylated peptide 5 containing an N-terminal cysteine. a) Peptide 5 + iodoacetamide (IAA), b) Peptide 5 + iodoacetic acid (IAC). The N-terminal cysteine of peptide 5 alkylated with iodoacetamide reacts to form N-terminal 5-oxohydro-1,4-thiazine-3-carboxylic acid, as indicated by a mass difference of -17 Da. After 51 h, the relative peak area of the peptide alkylated with iodoacetamide decreased by 18%. In contrast, no significant degradation was observed for peptide 5 alkylated with iodoacetic acid.

Figure 9.

Stability of alkylated peptide 5 containing an N-terminal cysteine. a) Peptide 5 + iodoacetamide (IAA), b) Peptide 5 + iodoacetic acid (IAC). The N-terminal cysteine of peptide 5 alkylated with iodoacetamide reacts to form N-terminal 5-oxohydro-1,4-thiazine-3-carboxylic acid, as indicated by a mass difference of -17 Da. After 51 h, the relative peak area of the peptide alkylated with iodoacetamide decreased by 18%. In contrast, no significant degradation was observed for peptide 5 alkylated with iodoacetic acid.

Table 1.

List of all expected peptides in the CEF pool.

Table 1.

List of all expected peptides in the CEF pool.

| Peptide |

Sequence |

Exact mass [2,3] |

| 1 |

VSDGGPNLY |

920.4240 |

| 2 |

CTELKLSDY |

1070.4954 |

| 3 |

GILGFVFTL |

965.5586 |

| 4 |

FMYSDFHFI |

1205.5216 |

| 5 |

CLGGLLTMV |

905.4715 |

| 6 |

GLCTLVAML |

919.4871 |

| 7 |

NLVPMVATV |

942.5208 |

| 8 |

KTGGPIYKR |

1018.5924 |

| 9 |

RVLSFIKGTK |

1147.7077 |

| 10 |

ILRGSVAHK |

979.5927 |

| 11 |

RVRAYTYSK |

1142.6196 |

| 12 |

RLRAEAQVK |

1069.6356 |

| 13 |

SIIPSGPLK |

910.5488 |

| 14 |

AVFDRKSDAK |

1135.5986 |

| 15 |

IVTDFSVIK |

1020.5856 |

| 16 |

ATIGTAMYK |

954.4845 |

| 17 |

DYCNVLNKEF |

1243.5543 |

| 18 |

LPFDKTTVM |

1050.5420 |

| 19 |

RPPIFIRRL |

1166.7400 |

| 20 |

ELRSRYWAI |

1192.6353 |

| 21 |

RAKFKQLL |

1002.6338 |

| 22 |

FLRGRAYGL |

1051.5927 |

| 23 |

QAKWRLQTL |

1142.6560 |

| 24 |

SDEEEAIVAYTL |

1338.6191 |

| 25 |

SRYWAIRTR |

1207.6574 |

| 26 |

ASCMGLIY |

856.3823 |

| 27 |

RRIYDLIEL |

1189.6819 |

| 28 |

YPLHEQHGM |

1110.4917 |

| 29 |

IPSINVHHY |

1078.5560 |

| 30 |

EENLLDFVRF |

1280.6401 |

| 31 |

EFFWDANDIY |

1318.5506 |

| 32 |

TPRVTGGGAM |

945.4702 |

Table 2.

Potential intra-residue cyclization of amino acids and subsequent reactions (- not found).

Table 2.

Potential intra-residue cyclization of amino acids and subsequent reactions (- not found).

| Peptide |

Sequence |

∆ mass [Da] |

Impurity |

| 1 |

VSDGGPNLY |

-18 |

aspartimide |

| 2 |

CTELKLSDY |

- |

|

| 4 |

FMYSDFHFI |

- |

|

| 7 |

NLVPMVATV |

+1 |

deamidation |

| 12 |

RLRAEAQVK |

- |

|

| 14 |

AVFDRKSDAK |

- |

|

| 15 |

IVTDFSVIK |

- |

|

| 17 |

DYCNVLNKEF |

- |

|

| 18 |

LPFDKTTVM |

- |

|

| 20 |

ELRSRYWAI |

-18 |

pyroglutamate |

| 21 |

RAKFKQLL |

- |

|

| 23 |

QAKWRLQTL |

-17 |

pyroglutamate |

| 24 |

SDEEEAIVAYTL |

- |

|

| 27 |

RRIYDLIEL |

- |

|

| 28 |

YPLHEQHGM |

- |

|

| 29 |

IPSINVHHY |

- |

|

| 30 |

EENLLDFVRF |

-18 |

pyroglutamate |

| 31 |

EFFWDANDIY |

-18 |

pyroglutamate |

Table 3.

Relative proportion of impurities from the respective parent peptide. Note: For peptides that form dimers, the purity may be overestimated, as UV peak areas may be not accessible (n.a.) for some species (see peptide 6).

Table 3.

Relative proportion of impurities from the respective parent peptide. Note: For peptides that form dimers, the purity may be overestimated, as UV peak areas may be not accessible (n.a.) for some species (see peptide 6).

Peptide

No.

|

Relative Area (UV) [%] |

| 1 |

82 |

| 1-H2O |

18 |

| 31 |

87 |

| 31 pGlu |

13 |

| 16 |

92 |

| 16+O |

8 |

| 4 |

94 |

| 4+O |

6 |

| 6 |

71 |

| 6 Dimer |

6 |

| 6 Dimer+O |

5 |

| 17+6 |

9 |

| 26+6 |

n.a. |

| 2+6+O |

n.a. |

| 2+6 |

n.a. |

| 17+6+O |

n.a. |

| 6+5 |

n.a. |

| 6+5+O |

n.a. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).