Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

21 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

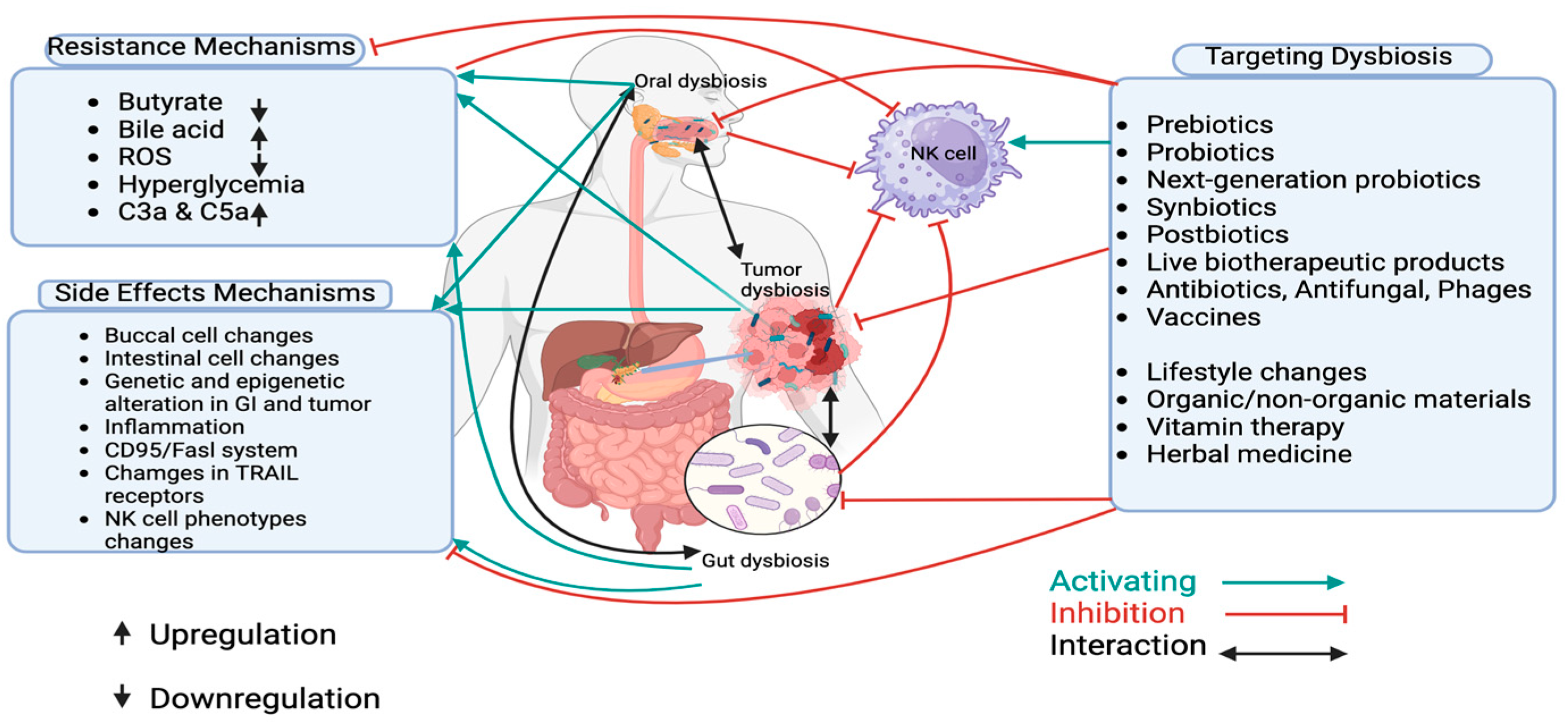

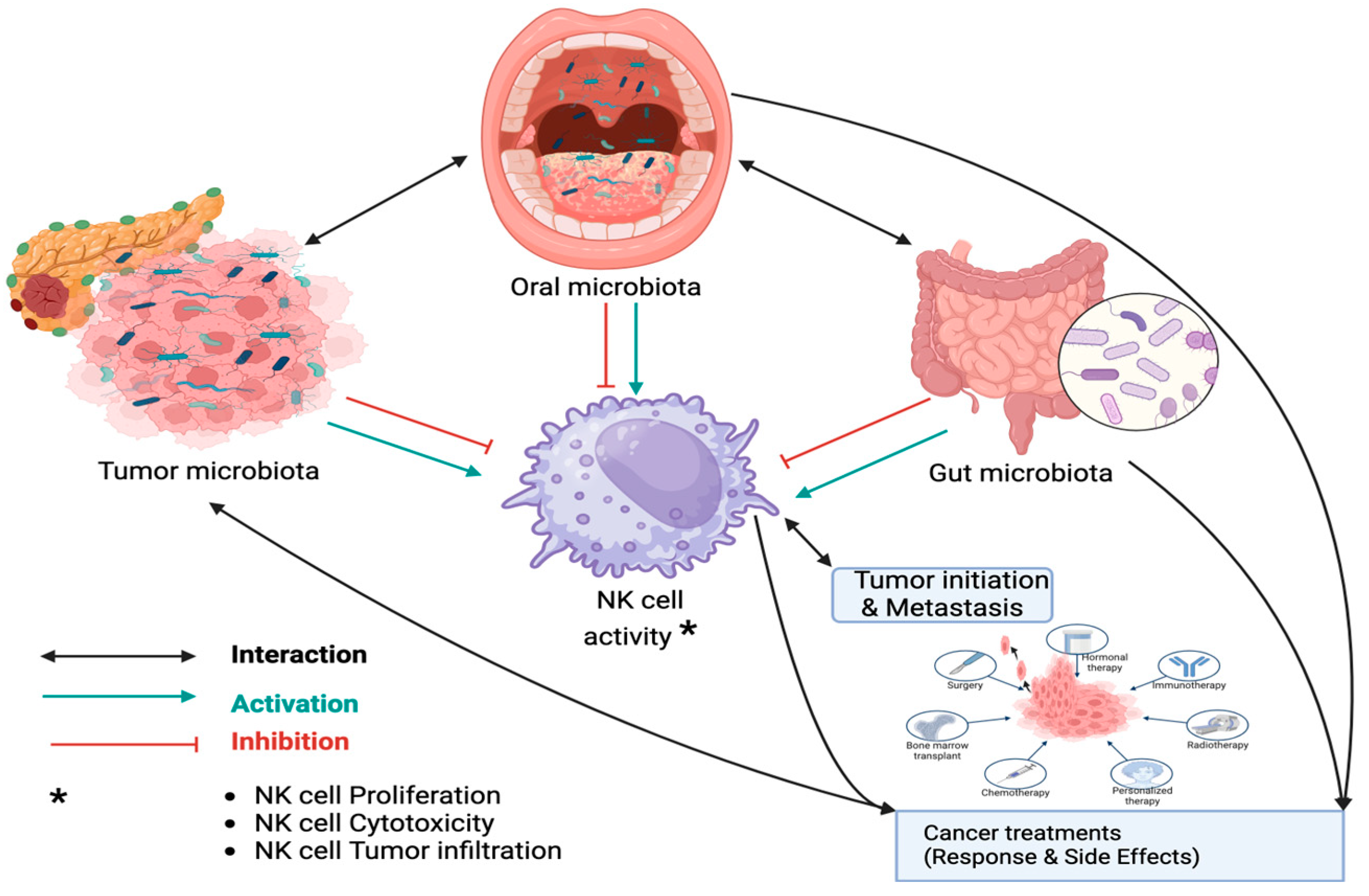

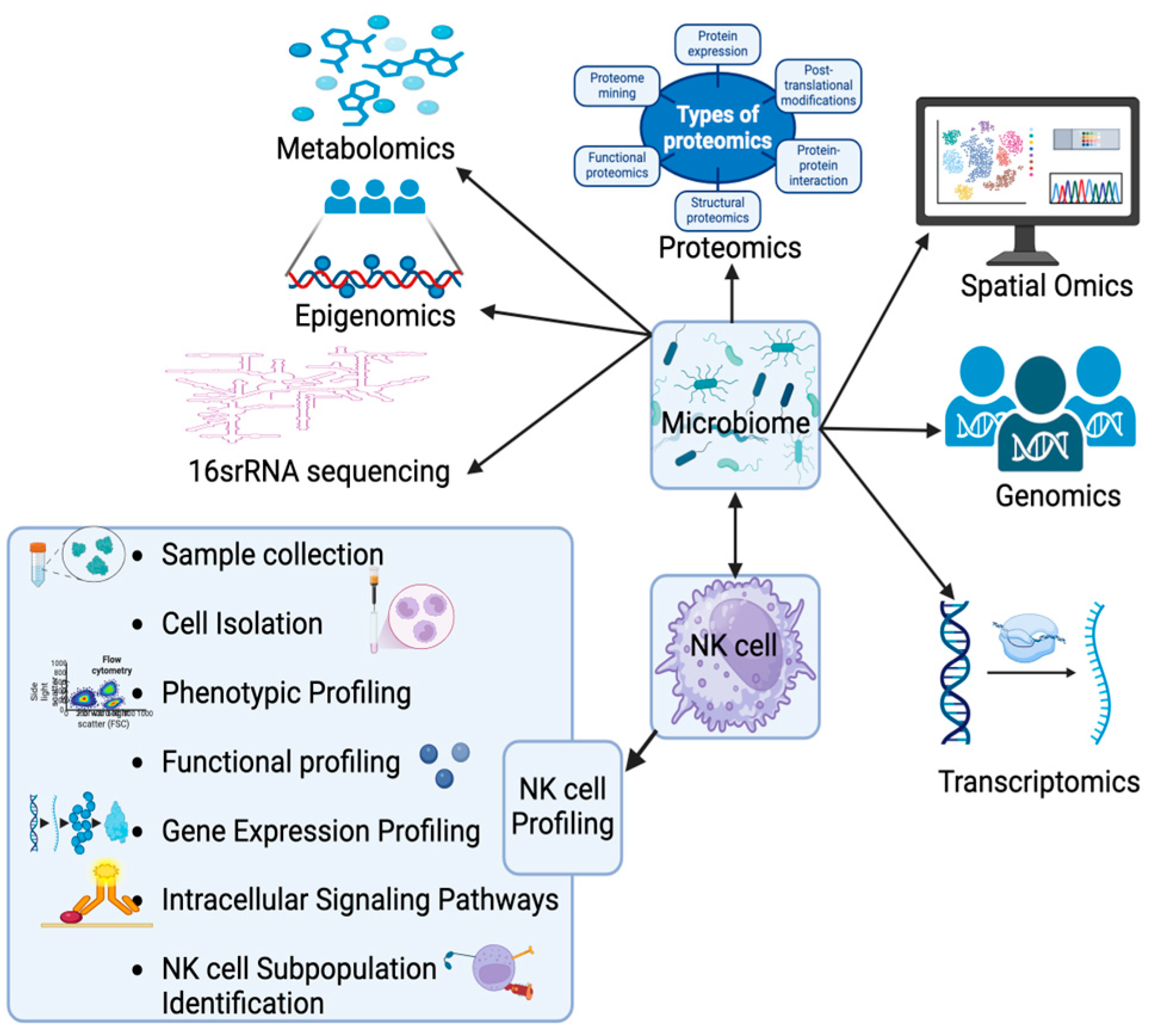

2. Interaction Between Microbiota and NK Cell Function in PDAC

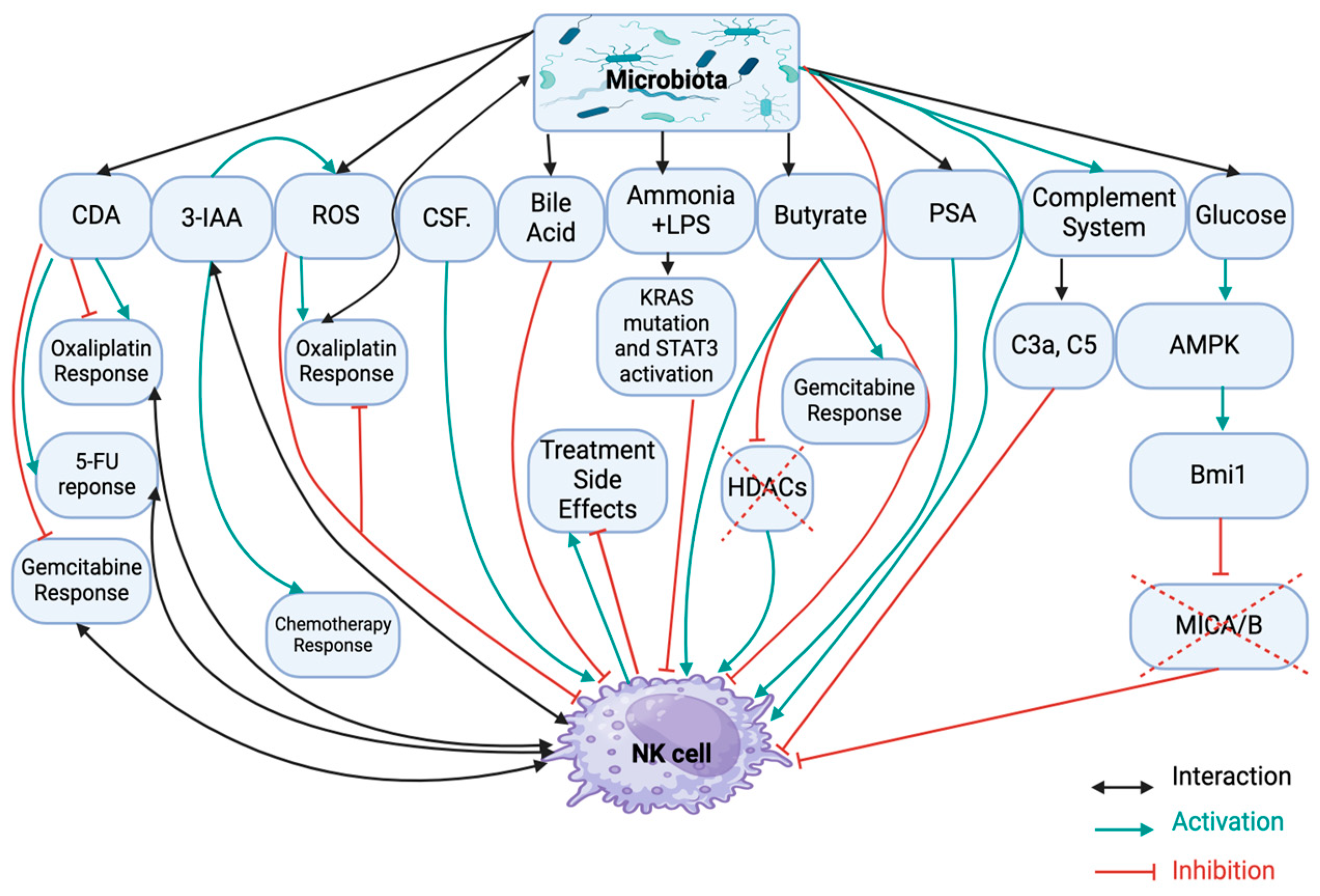

2.1. Dysbiosis Induced NK Cell Dysfunction in PDAC

2.2. Dysbiosis Induced Drug Resistance in PDAC

2.3. Dysbiosis-Induced Treatment Side Effects

3. Targeting Dysbiosis in PDAC for Overcoming Treatment Resistance and Managing Side Effects

3.1. Prebiotics

3.2. Probiotics

3.3. Next-Generation Probiotics

3.4. Synbiotics

3.5. Postbiotics

3.6. Live Biotherapeutic Products

3.6.1. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

3.6.2. Tumor-Colonizing Bacteria

3.7. Antibiotics, Antifungal and Phage Therapy

3.8. Vaccines

4. Discussion and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, S.; Qiu, M.; von Voithenberg, L.V.; Hulkkonen, J.; Macinkovic, I.; Schulz, A.R.; Hartmann, D.; Mueller, F.; Mijatovic, M.; Ibberson, D.; et al. Spatially Resolved Multi-Omics Single-Cell Analyses Inform Mechanisms of Immune Dysfunction in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 891–908.e14. [CrossRef]

- Wood LD, Canto MI, Jaffee EM and Simeone DM. “Pancreatic Cancer: pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment”. Gastroenterology, vol. 163, no. 2, 386–402, 2022.

- Poggi, A.; Benelli, R.; Venè, R.; Costa, D.; Ferrari, N.; Tosetti, F.; Zocchi, M.R. Human Gut-Associated Natural Killer Cells in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 961. [CrossRef]

- K Søreide, W Ismail, M Roalsø, J Ghotbi and C Zaharia. “Early diagnosis of pancreatic Cancer: clinical premonitions, timely precursor detection and increased curative-intent surgery”. Cancer control: journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center, vol. 30, 10732748231154711–10732748231154711, 2023.

- Matsukawa, H.; Iida, N.; Kitamura, K.; Terashima, T.; Seishima, J.; Makino, I.; Kannon, T.; Hosomichi, K.; Yamashita, T.; Sakai, Y.; et al. Dysbiotic gut microbiota in pancreatic cancer patients form correlation networks with the oral microbiota and prognostic factors. 2021, 11, 3163–+.

- Benešová, I.; Křížová, .; Kverka, M. Microbiota as the unifying factor behind the hallmarks of cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 14429–14450. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Jiang, J.; Xie, H.; Li, A.; Lu, H.; Xu, S.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, H.; Cui, G.; Chen, X.; et al. Gut microbial profile analysis by MiSeq sequencing of pancreatic carcinoma patients in China. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 95176–95191. [CrossRef]

- Bracci PM. “Oral Health and the Oral Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer: An Overview of Epidemiological Studies.”. Cancer J., vol. 23, no. 6, 2017.

- Ji, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wei, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Zhao, B.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Intratumoural microbiota: from theory to clinical application. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Qian J, Zhang X, Wei B and Tang Z and Zhang B. “The correlation between gut and intra-tumor microbiota and PDAC: Etiology, diagnostics and therapeutics.”. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, vol. 1878, no. 5, 2023.

- Cruz, M.S.; Tintelnot, J.; Gagliani, N. Roles of microbiota in pancreatic cancer development and treatment. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2320280. [CrossRef]

- Ames, N.J.; Ranucci, A.; Moriyama, B.; Wallen, G.R. The Human Microbiome and Understanding the 16S rRNA Gene in Translational Nursing Science. Nurs. Res. 2017, 66, 184–197. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yang, G.; Yang, J.; Ren, J.; You, L.; Zhao, Y. Human microbiota colonization and pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 49, 455–468. [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Montiel, M.; Zoltan, M.; Dong, W.; Quesada, P.; Sahin, I.; Chandra, V.; Lucas, A.S.; et al. Tumor Microbiome Diversity and Composition Influence Pancreatic Cancer Outcomes. Cell 2019, 178, 795–806.e12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, N.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Yin, X.; Hao, H.; Tan, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, H.; et al. Intratumor Microbiome Analysis Identifies Positive Association Between Megasphaera and Survival of Chinese Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 785422. [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, I.; Nannini, G.; Risaliti, M.; Matarazzo, F.; Moraldi, L.; Ringressi, M.N.; Taddei, A.; Amedei, A. Impact of microbiota-immunity axis in pancreatic cancer management. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4527–4539. [CrossRef]

- Narunsky-Haziza, L.; Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Livyatan, I.; Asraf, O.; Martino, C.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Stajich, J.E.; Amit, G.; González, A.; et al. Pan-cancer analyses reveal cancer-type-specific fungal ecologies and bacteriome interactions. Cell 2022, 185, 3789–3806.e17. [CrossRef]

- Chakladar, J.; Kuo, S.Z.; Castaneda, G.; Li, W.T.; Gnanasekar, A.; Yu, M.A.; Chang, E.Y.; Wang, X.Q.; Ongkeko, W.M. The Pancreatic Microbiome Is Associated with Carcinogenesis and Worse Prognosis in Males and Smokers. Cancers 2020, 12, 2672. [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.-L.; Li, M.; Li, G.-Q.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.-M.; Li, Z.-L.; Yuan, J.; Liu, H.-Y.; Zhou, L.-L.; Li, K.; et al. Oral microbiome and pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 7679–7692. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W.; Shi, J.; Yu, S.; Feng, H.; Yu, Z. Bile Acids and Liver Cancer: Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Prospects. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1142. [CrossRef]

- Wei X, Li W and Ma Y et al. “Endogenous Propionibacterium acnes Promotes Ovarian Cancer Progression via Regulating Hedgehog Signalling Pathway”. Cancers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 21, 2022.

- Mohelnikova-Duchonova, B.; Kocik, M.; Duchonova, B.; Brynychova, V.; Oliverius, M.; Hlavsa, J.; Honsova, E.; Mazanec, J.; Kala, Z.; Ojima, I.; et al. Hedgehog pathway overexpression in pancreatic cancer is abrogated by new-generation taxoid SB-T-1216. Pharmacogenom. J. 2017, 17, 452–460. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wang, D.; Shukla, S.K.; Hu, T.; Thakur, R.; Fu, X.; King, R.J.; Kollala, S.S.; Attri, K.S.; Murthy, D.; et al. Vitamin B6 Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Hampers Antitumor Functions of NK Cells. Cancer Discov. 2023, 14, 176–193. [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Qin, B.; Wang, Q. Insight into Cancer Immunity: MHCs, Immune Cells and Commensal Microbiota. Cells 2023, 12, 1882. [CrossRef]

- Knudson, A.G., Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 820–823. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.K.; Batra, S.K.; Jain, M. Molecular and metabolic regulation of immunosuppression in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Luo W and Wen T and Qu X. “Tumor immune microenvironment-based therapies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: time to update the concept.”. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, vol. 43, no. 1, 2024.

- Marcon, F.; Zuo, J.; Pearce, H.; Nicol, S.; Margielewska-Davies, S.; Farhat, M.; Mahon, B.; Middleton, G.; Brown, R.; Roberts, K.J.; et al. NK cells in pancreatic cancer demonstrate impaired cytotoxicity and a regulatory IL-10 phenotype. OncoImmunology 2020, 9, 1845424. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. Influence of the gut microbiota on immune cell interactions and cancer treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Tassone, E.; Muscolini, M.; van Montfoort, N.; Hiscott, J. Oncolytic virotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A glimmer of hope after years of disappointment?. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 56, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Gur, C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Isaacson, B.; Yamin, R.; Abed, J.; Gamliel, M.; Enk, J.; Bar-On, Y.; Stanietsky-Kaynan, N.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; et al. Binding of the Fap2 Protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to Human Inhibitory Receptor TIGIT Protects Tumors from Immune Cell Attack. Immunity 2015, 42, 344–355. [CrossRef]

- Tsakmaklis, A.; Farowski, F.; Zenner, R.; Lesker, T.R.; Strowig, T.; Schlößer, H.; Lehmann, J.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; Mauch, C.; Schlaak, M.; et al. TIGIT+ NK cells in combination with specific gut microbiota features predict response to checkpoint inhibitor therapy in melanoma patients. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- K France and A Villa. “Acute oral lesions”. Dermatol. Clin, vol. 38, 2020.

- Gasmi Benahmed, A Noor, S Menzel, A Gasmi and A. “Oral aphthous: Pathophysiology, clinical aspects and medical treatment”. Arch. Razi Inst, vol. 76, 1155–1163, 2021.

- Hong, B.-Y.; Sobue, T.; Choquette, L.; Dupuy, A.K.; Thompson, A.; Burleson, J.A.; Salner, A.L.; Schauer, P.K.; Joshi, P.; Fox, E.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis is associated with detrimental bacterial dysbiosis. Microbiome 2019, 7, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Theda, C.; Hwang, S.H.; Czajko, A.; Loke, Y.J.; Leong, P.; Craig, J.M. Quantitation of the cellular content of saliva and buccal swab samples. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Chia, D.; Elashoff, D.; Akin, D.; Paster, B.J.; Joshipura, K.; Wong, D.T.W. Variations of oral microbiota are associated with pancreatic diseases including pancreatic cancer. Gut 2012, 61, 582–588. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Z.A.; Dalal, R.; Sadhu, S.; Kumar, Y.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Tripathy, M.R.; Rathore, D.K.; Awasthi, A. High-salt diet mediates interplay between NK cells and gut microbiota to induce potent tumor immunity. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- G Pourali, D Kazemi and A S Chadeganipour. “Microbiome as a biomarker and therapeutic target in pan- creatic cancer”. BMC Microbiol, vol. 24, 16–16, 2024.

- Yu, Q.; Newsome, R.C.; Beveridge, M.; Hernandez, M.C.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Jobin, C.; Thomas, R.M. Intestinal microbiota modulates pancreatic carcinogenesis through intratumoral natural killer cells. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2112881. [CrossRef]

- X Zhang, Q Liu, Q Liao and Y Zhao. “Pancreatic Cancer, gut microbiota, and therapeutic efficacy”. J Cancer, vol. 11, 2749–58, 2020.

- Noh, J.-Y.; Yoon, S.R.; Kim, T.-D.; Choi, I.; Jung, H. Toll-Like Receptors in Natural Killer Cells and Their Application for Immunotherapy. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ganal, S.C.; Sanos, S.L.; Kallfass, C.; Oberle, K.; Johner, C.; Kirschning, C.; Lienenklaus, S.; Weiss, S.; Staeheli, P.; Aichele, P.; et al. Priming of Natural Killer Cells by Nonmucosal Mononuclear Phagocytes Requires Instructive Signals from Commensal Microbiota. 2012, 37, 171–186. [CrossRef]

- Esin, S.; Batoni, G.; Counoupas, C.; Stringaro, A.; Brancatisano, F.L.; Colone, M.; Maisetta, G.; Florio, W.; Arancia, G.; Campa, M. Direct Binding of Human NK Cell Natural Cytotoxicity Receptor NKp44 to the Surfaces of Mycobacteria and Other Bacteria. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 1719–1727. [CrossRef]

- Lam KC, Araya RE, Huang A et al. “Microbiota triggers STING-type I IFN-dependent monocyte repro- gramming of the tumor microenvironment. Cell, 2021.

- Qiu Y, Jiang Z and Hu S, Wang L, Ma X and Yang X. “Lactobacillus plantarum enhanced IL-22 produc- tion in Natural Killer (NK) cells that protect the integrity of intestinal epithelial cell barrier damaged by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli”. Int J Mol Sci, 2017.

- K Kaz´mierczak-Siedlecka, J Ruszkowski, K Skonieczna-Z˙ ydecka et al. “Gastrointestinal cancers: the role of microbiota in carcinogenesis and the role of probiotics and microbiota in the anti-cancer therapy efficacy”. Cent Eur J of Immunol, vol. 45, no. 4, 476–487, 2020.

- Tan, Q.; Ma, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Ma, J. Periodontitis pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis via neutrophil elastase from tumor-associated neutrophils. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2073785. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, L.; Werba, G.; Tiwari, S.; Ly, N.N.G.; Alothman, S.; Alqunaibit, D.; Avanzi, A.; Barilla, R.; Daley, D.; Greco, S.H.; et al. The necrosome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via CXCL1 and Mincle-induced immune suppression. Nature 2016, 532, 245–249. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ye, N.; Jin, G.; Shi, H.; Qian, D. Leveraging the intratumoral microbiota to treat human cancer: are engineered exosomes an effective strategy?. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pushalkar, S.; Hundeyin, M.; Daley, D.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Kurz, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohan, N.; Aykut, B.; Usyk, M.; Torres, L.E.; et al. The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416. [CrossRef]

- Hamel, Z.; Sanchez, S.; Standing, D.; Anant, S. Role of STAT3 in pancreatic cancer. Explor. Target. Anti-tumor Ther. 2024, 5, 20–33. [CrossRef]

- P B Dodhiawala, B Zhang et al. “Targeting the KRAS oncoprotein sensitizes pancreatic cancer to NK cell therapyJournal for ImmunoTherapy of”. Cancer, vol. 12, 2024.

- Schnoegl, D.; Hiesinger, A.; Huntington, N.D.; Gotthardt, D. AP-1 transcription factors in cytotoxic lymphocyte development and antitumor immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2023, 85, 102397. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L Y, Mei J X, Yu G et al. “Role of the gut microbiota in anticancer therapy: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. ”. Sig Transduct Target Ther, vol. 8, no. 201, 2023.

- Vogtmann, E.; Han, Y.; Caporaso, J.G.; Bokulich, N.; Mohamadkhani, A.; Moayyedkazemi, A.; Hua, X.; Kamangar, F.; Wan, Y.; Suman, S.; et al. Oral microbial community composition is associated with pancreatic cancer: A case-control study in Iran. Cancer Med. 2019, 9, 797–806. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Gao, H.-L.; Wang, W.-Q.; Yu, X.-J.; Liu, L. Bidirectional and dynamic interaction between the microbiota and therapeutic resistance in pancreatic cancer. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188484. [CrossRef]

- Oar, A.; Lee, M.; Le, H.; Wilson, K.; Aiken, C.; Chantrill, L.; Simes, J.; Nguyen, N.; Barbour, A.; Samra, J.; et al. AGITG MASTERPLAN: a randomised phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX alone or in combination with stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with high-risk and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- N Goel, A Nadler, S Reddy, J P Hoffman and H A Pitt. “Biliary Microbiome in Pancreatic Cancer: Alter- ations with Neoadjuvant Therapy”. HPB Off. J. Int. Hepato Pancreato Biliary Assoc, vol. 21, 1753–1760, 2019.

- Nadeem, S.O.; Jajja, M.R.; Maxwell, D.W.; Pouch, S.M.; Sarmiento, J.M. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer and changes in the biliary microbiome. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 222, 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Hank, T.; Sandini, M.; Ferrone, C.R.; Rodrigues, C.; Weniger, M.; Qadan, M.; Warshaw, A.L.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Castillo, C.F.-D. Association Between Pancreatic Fistula and Long-term Survival in the Era of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 943–951. [CrossRef]

- H R Shrader, A M Miller, A Tomanek-Chalkley et al. “Effect of Bacterial Contamination in Bile on Pancre- atic Cancer Cell Survival”. Surgery, vol. 169, 617–622, 2021.

- Routy, B.; le Chatelier, E.; DeRosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N et al. “Commensal bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facili- tates anti-pd-L1 efficacy”. Science, vol. 350, no. 6264, 2015.

- Gnanamony, M.; Gondi, C.S. Chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer: Emerging concepts. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 2507–2513. [CrossRef]

- Geller, L.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Danino, T.; Jonas, O.H.; Shental, N.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Cooper, Z.A.; Shee, K.; et al. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156–1160. [CrossRef]

- Asa El-Sayed, N Z Mohamed, M A Yassin et al. “Microbial cytosine deaminase is a programmable anti- cancer prodrug mediating enzyme: antibody, and gene directed enzyme prodrug therapy”. Heliyon, vol. 8, 9508425–9508425, 2022.

- T Scolaro, M Manco and M Pecqueux. “Nucleotide metabolism in cancer cells fuels a UDP-driven macrophage crosstalk, promoting immunosuppression and immunotherapy resistance”. Nat Cancer, vol. 5, 1206–1226, 2024.

- Audrey Lumeau et al. “Cytidine Deaminase Resolves Replicative Stress and Protects Pancreatic Cancer from DNA-Targeting Drugs.”. Cancer research, vol. 84, 1013–1028, 2024.

- Vieira, V.C.; Soares, M.A. The Role of Cytidine Deaminases on Innate Immune Responses against Human Viral Infections. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- A Panebianco, F Villani, F Pisati et al. “Butyrate, a postbiotic of intestinal bacteria, affects pancreatic cancer and gemcitabine response in in vitro and in vivo models ”. Biomed Pharmacother, vol. 151, 2022.

- Panebianco, C.; Adamberg, K.; Jaagura, M.; Copetti, M.; Fontana, A.; Adamberg, S.; Kolk, K.; Vilu, R.; Andriulli, A.; Pazienza, V. Influence of gemcitabine chemotherapy on the microbiota of pancreatic cancer xenografted mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 773–782. [CrossRef]

- Linsheng Xu, Bingde Hu, Jingli He, Xin Fu and Na Liu. “Intratumor microbiome-derived butyrate promotes chemo-resistance in colorectal cancer”. Front. Pharmacol., vol. 15, 2024.

- Udayasuryan, Barath et al. “Fusobacterium nucleatum induces proliferation and migration in pancreatic cancer cells through host autocrine and paracrine signaling.” Science signaling vol. 15,756 (2022): eabn4948. Iida, A Dzutsev, C A Stewart et al. “Commensal Bacteria Control Cancer Response to Therapy by Modu- lating the Tumor Microenvironment”. Science, vol. 342, 967–970, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Matsunaga, K.-I. Susceptibility of Natural Killer (NK) Cells to Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Their Restoration by the Mimics of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD). Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 1998, 13, 275–290. [CrossRef]

- Kesh, K.; Mendez, R.; Abdelrahman, L.; Banerjee, S.; Banerjee, S. Type 2 diabetes induced microbiome dysbiosis is associated with therapy resistance in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 75. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Meng, Z.; Bai, J.; Shen, Q.; Wu, H.; Yin, T. Hyperglycemia Enhances Immunosuppression and Aerobic Glycolysis of Pancreatic Cancer Through Upregulating Bmi1-UPF1-HK2 Pathway. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 14, 1146–1165. [CrossRef]

- Cattolico, C.; Bailey, P.; Barry, S.T. Modulation of Type I Interferon Responses to Influence Tumor-Immune Cross Talk in PDAC. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 816517. [CrossRef]

- Dong TS, Chang H H, Hauer M et al. “Metformin alters the duodenal microbiome and decreases the inci- dence of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma promoted by diet-induced obesity.”. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol., 2019.

- D Ren, G Qin, J Zhao et al. “Metformin Activates the STING/IRF3/IFN-β Pathway by Inhibiting AKT Phosphorylation in Pancreatic Cancer”. Am. J. Cancer Res, vol. 10, no. 9, 2851–2864, 2020.

- R Vemuri, E M Shankar, M Chieppa, R Eri and K Kavanagh. “Beyond Just Bacteria: Functional Biomes in the Gut Ecosystem Including Virome, Mycobiome”. Archaeome and Helminths. Microorganisms, vol. 8, 483–483, 2020.

- Aykut, B.; Pushalkar, S.; Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Abengozar, R.; Kim, J.I.; Shadaloey, S.A.; Wu, D.; Preiss, P.; Verma, N.; et al. The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 2019, 574, 264–267. [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Levanduski, E.; Denz, P.; Villavicencio, H.S.; Bhatta, M.; Alhorebi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gomez, E.C.; Morreale, B.; Senchanthisai, S.; et al. Fungal mycobiome drives IL-33 secretion and type 2 immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 153–167.e11. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Nishijima, S.; Kojima, Y.; Hisada, Y.; Imbe, K.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T.; Suda, W.; Kimura, M.; Aoki, R.; Sekine, K.; et al. Metagenomic Identification of Microbial Signatures Predicting Pancreatic Cancer From a Multinational Study. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 222–238. [CrossRef]

- H Y Temel, Ö Kaymak, S Kaplan et al. “Role of microbiota and microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in PDAC”. Cancer Medicine, vol. 12, no. 5, 5661–75, 2023.

- Yu, Q.; Jobin, C.; Thomas, R.M. Implications of the microbiome in the development and treatment of pancreatic cancer: Thinking outside of the box by looking inside the gut. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 246–256. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-S.; Tang, Y.-L.; Pang, X.; Zheng, M.; Liang, X.-H. The maintenance of an oral epithelial barrier. Life Sci. 2019, 227, 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Sima Ataollahi Eshkoor and Sara Fanijavadi. “Dysbiosis-epigenetics-immune system interaction and ageing health problems”. Journal of medical microbiology, vol. 73, no. 11, 2024.

- Chander MP, C. Kartick, J. Gangadhar, P. Vijayachari, Ethno medicine and healthcare practices among Nicobarese of Car Nicobar - an indigenous tribe of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, J. Ethnopharmacol. 158 (2014) 18–24. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.046.

- Kawasaki, Y.; Kakimoto, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Nishida, K.; Numa, K.; Kinoshita, N.; Tatsumi, Y.; Nakazawa, K.; Koshiba, R.; et al. Relationship between Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea and Intestinal Microbiome Composition. Digestion 2023, 104, 357–369. [CrossRef]

- A M Stringer, R J Gibson, R M Logan et al. “Faecal Microflora and Beta-Glucuronidase Expression Are Altered in an Irinotecan-Induced Diarrhea Model in Rats”. Cancer Biol. Ther, 1919.

- Secombe, K.R.; Coller, J.K.; Gibson, R.J.; Wardill, H.R.; Bowen, J.M. The bidirectional interaction of the gut microbiome and the innate immune system: Implications for chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 144, 2365–2376. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Hwang, I.; Yoo, C.; Kim, K.-P.; Jeong, J.H.; Chang, H.-M.; Lee, S.S.; Park, D.H.; Song, T.J.; Seo, D.W.; et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus FOLFIRINOX as the first-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: retrospective analysis. Investig. New Drugs 2018, 36, 732–741. [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Fan, Z.; Liu, B.; Lu, T. The benefits of modified FOLFIRINOX for advanced pancreatic cancer and its induced adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Deirdre R Pachman et al. “Comparison of oxaliplatin and paclitaxel-induced neuropathy ”. Supportive care in cancer, vol. 24, 5059–5068, 2016.

- Jaggi, A.S.; Singh, N. Mechanisms in cancer-chemotherapeutic drugs-induced peripheral neuropathy. Toxicology 2012, 291, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Toxicology, vol. 291, 2012.

- H Shi, M Chen, C Zheng, B Yinglin and B Zhu. “Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Alleviated Paclitaxel- Induced Peripheral Neuropathy by Interfering with Astrocytes and TLR4/p38MAPK Pathway in Rats”. J Pain Res, vol. 16, 2419–2432, 2023.

- Peng, S.; Ying, A.F.; Chan, N.J.H.; Sundar, R.; Soon, Y.Y.; Bandla, A. Prevention of Oxaliplatin-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 731223. [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.J.; Rinaldi, S.; Costigan, M.; Oh, S.B. Cytotoxic Immunity in Peripheral Nerve Injury and Pain. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 142. [CrossRef]

- Front Neurosci, vol. 14, 142–142, 2020.

- Karaliute, I.; Ramonaite, R.; Bernatoniene, J.; Petrikaite, V.; Misiunas, A.; Denkovskiene, E.; Razanskiene, A.; Gleba, Y.; Kupcinskas, J.; Skieceviciene, J. Reduction of gastrointestinal tract colonization by Klebsiella quasipneumoniae using antimicrobial protein KvarIa. Gut Pathog. 2022, 14, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Knudson, A.G., Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 820–823. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, P.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Qin, W. Carvacrol Treatment Reduces Decay and Maintains the Postharvest Quality of Red Grape Fruits (Vitis vinifera L.) Inoculated with Alternaria alternata. Foods 2023, 12, 4305. [CrossRef]

- Nejman, D.; Livyatan, I.; Fuks, G.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Geller, L.T.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Weiser, R.; Mallel, G.; Gigi, E.; et al. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type–specific intracellular bacteria. Science 2020, 368, 973–980. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, R.; Ren, X.; Wang, H.; Zou, L. Characterization of Oral Microbiome and Exploration of Potential Biomarkers in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Cintoni, M.; Raoul, P.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F.; Pulcini, G.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2393. [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, K.; Nosho, K.; Sukawa, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ito, M.; Kurihara, H.; Kanno, S.; Igarashi, H.; Naito, T.; Adachi, Y.; et al. Association ofFusobacteriumspecies in pancreatic cancer tissues with molecular features and prognosis. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7209–7220. [CrossRef]

- I J Malesza, M Malesza, J Walkowiak et al. “Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Micro- biota: A Narrative Review”. Cells, vol. 10, 3164–3164, 2021.

- Half, E.; Keren, N.; Reshef, L.; Dorfman, T.; Lachter, I.; Kluger, Y.; Reshef, N.; Knobler, H.; Maor, Y.; Stein, A.; et al. Fecal microbiome signatures of pancreatic cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Ren, R.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; et al. The fecal microbiota of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and autoimmune pancreatitis characterized by metagenomic sequencing. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Li W and Li Z and Wu Q and Sun S. “Influence of Microbiota on Tumor Immunotherapy”. Int J Biol Sci, vol. 20, no. 6, 2024.

- Chang, C.-W.; Liu, C.-Y.; Lee, H.-C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Li, L.-H.; Chiau, J.-S.C.; Wang, T.-E.; Chu, C.-H.; Shih, S.-C.; Tsai, T.-H.; et al. Lactobacillus casei Variety rhamnosus Probiotic Preventively Attenuates 5-Fluorouracil/Oxaliplatin-Induced Intestinal Injury in a Syngeneic Colorectal Cancer Model. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 983. [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.C.; Araya, R.E.; Huang, A.; Chen, Q.; Di Modica, M.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Lopès, A.; Johnson, S.B.; Schwarz, B.; Bohrnsen, E.; et al. Microbiota triggers STING-type I IFN-dependent monocyte reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2021, 184, 5338–5356.e21, Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867421010667.

- Prasad, K.N.; Kumar, A.; Kochupillai, V.; Cole, W.C. High doses of multiple antioxidant vitamins: essential ingredients in improving the efficacy of standard cancer therapy.. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1999, 18, 13–25. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Kumari, I.; Singh, B.; Sharma, K.K.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for next-generation therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 505–521. [CrossRef]

- Pujari, R.; Banerjee, G. Impact of prebiotics on immune response: from the bench to the clinic. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020, 99, 255–273. [CrossRef]

- Pujari, R.; Banerjee, G. Impact of prebiotics on immune response: from the bench to the clinic. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020, 99, 255–273. [CrossRef]

- Trivieri N, Panebianco C, Villani A et al. “High Levels of Prebiotic Resistant Starch in Diet Modulate a Spe- cific Pattern of miRNAs Expression Profile Associated to a Better Overall Survival in Pancreatic Cancer.”. Biomolecules, vol. 11, no. 1, 2020.

- Shi Y, Cui H, Wang F et al. “Role of gut microbiota in postoperative complications and prognosis of gas- trointestinal surgery: A narrative review. ”. Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 101, no. 29, 2022.

- Davoodvandi, A.; Fallahi, F.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Tajiknia, V.; Banikazemi, Z.; Fathizadeh, H.; Abbasi-Kolli, M.; Aschner, M.; Ghandali, M.; Sahebkar, A.; et al. An Update on the Effects of Probiotics on Gastrointestinal Cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 680400. [CrossRef]

- Rivai, M.I.; Lusikooy, R.E.; Putra, A.E.; Elliyanti, A. Effects of Lactococcus lactis on colorectal cancer in various terms: a narrative review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 3503–3507. [CrossRef]

- Tintelnot, J.; Xu, Y.; Lesker, T.R.; Schönlein, M.; Konczalla, L.; Giannou, A.D.; Pelczar, P.; Kylies, D.; Puelles, V.G.; Bielecka, A.A.; et al. Microbiota-derived 3-IAA influences chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 615, 168–174. [CrossRef]

- Kato-Kataoka, A.; Nishida, K.; Takada, M.; Kawai, M.; Kikuchi-Hayakawa, H.; Suda, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Gondo, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Matsuki, T.; et al. Fermented Milk Containing Lactobacillus casei Strain Shirota Preserves the Diversity of the Gut Microbiota and Relieves Abdominal Dysfunction in Healthy Medical Students Exposed to Academic Stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3649–3658. [CrossRef]

- Ijiri, M.; Fujiya, M.; Konishi, H.; Tanaka, H.; Ueno, N.; Kashima, S.; Moriichi, K.; Sasajima, J.; Ikuta, K.; Okumura, T. Ferrichrome identified from Lactobacillus casei ATCC334 induces apoptosis through its iron-binding site in gastric cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39. [CrossRef]

- Goderska, K.; Pena, S.A.; Alarcon, T. Helicobacter pylori treatment: antibiotics or probiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 102, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.H.; Lundgren, A.; Azem, J.; Sjöling, A.; Holmgren, J.; Svennerholm, A.-M.; Lundin, B.S. Natural Killer Cells andHelicobacter pyloriInfection: Bacterial Antigens and Interleukin-12 Act Synergistically To Induce Gamma Interferon Production. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 1482–1490. [CrossRef]

- Aziz N and Bonavida B. “Activation of Natural Killer Cells by Probiotics.”. For Immunopathol Dis Therap., 2016.

- Wang, Y.-H.; Yao, N.; Wei, K.-K.; Jiang, L.; Hanif, S.; Wang, Z.-X.; Pei, C.-X. The efficacy and safety of probiotics for prevention of chemoradiotherapy-induced diarrhea in people with abdominal and pelvic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1246–1253. [CrossRef]

- Z Juan, J Chen, B Ding et al. “Probiotic supplement attenuates chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in patients with breast cancer: a randomised, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial ”. Eur J Cancer, vol. 161, 2022.

- C Panebianco, K Adamberg, S Adamberg et al. “Tuning Gut Microbiota through a Probiotic Blend in Gemcitabine-Treated Pancreatic Cancer Xenografted Mice”. Clin. Transl. Med., 2021.

- Lee, S.-H.; Cho, S.-Y.; Yoon, Y.; Park, C.; Sohn, J.; Jeong, J.-J.; Jeon, B.-N.; Jang, M.; An, C.; Lee, S.; et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum strains synergize with immune checkpoint inhibitors to reduce tumour burden in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 277–288. [CrossRef]

- Iida, N.; Dzutsev, A.; Stewart, C.A.; Smith, L.; Bouladoux, N.; Weingarten, R.A.; Molina, D.A.; Salcedo, R.; Back, T.; Cramer, S.; et al. Commensal Bacteria Control Cancer Response to Therapy by Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment. Science 2019, 342, 967–970. [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Langella, P. Emerging Health Concepts in the Probiotics Field: Streamlining the Definitions. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1047. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Duan, Y.; Cai, F.; Cao, D.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Z.; Hong, Q.; Li, N.; Zheng, Y.; Su, M.; et al. Next-Generation Probiotics: Microflora Intervention to Human Diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lu, C.; Gao, F.; Qian, Z.; Yin, Y.; Kan, S.; Chen, D. Selenium-enriched Bifidobacterium longum DD98 attenuates irinotecan-induced intestinal and hepatic toxicity in vitro and in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112192. [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Depommier, C.; Derrien, M.; Everard, A.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila: paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 625–637. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, S.; Yin, J.; Peng, X.; King, L.; Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Peng, Z.; Ze, X.; et al. Effect of synbiotic supplementation on immune parameters and gut microbiota in healthy adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2247025. [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.; Elmeligy, H.A.; Aboushousha, T.; Helal, N.S.; Ossama, Y.; Rady, M.; Hassan, A.M.A.; Kamel, M. Synergistic immunomodulatory effect of synbiotics pre- and postoperative resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled study. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2024, 73, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Beckett, J.M.; Kalpurath, K.; Ishaq, M.; Ahmad, T.; Eri, R.D. Synbiotics as Supplemental Therapy for the Alleviation of Chemotherapy-Associated Symptoms in Patients with Solid Tumours. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1759. [CrossRef]

- Zółkiewicz J and Marzec A. “Postbiotics-A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics”. Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 8, 2020.

- Klemashevich, C.; Wu, C.; Howsmon, D.; Alaniz, R.C.; Lee, K.; Jayaraman, A. Rational identification of diet-derived postbiotics for improving intestinal microbiota function. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 26, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- I Bangolo, A.; Trivedi, C.; Jani, I.; Pender, S.; Khalid, H.; Alqinai, B.; Intisar, A.; Randhawa, K.; Moore, J.; De Deugd, N.; et al. Impact of gut microbiome in the development and treatment of pancreatic cancer: Newer insights. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 3984–3998. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, B.; Nejad, R.A.K.; Vaziri, F.; Siadat, S.D. Evaluation of the effects of extracellular vesicles derived from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii on lung cancer cell line. Biologia 2019, 74, 889–898. [CrossRef]

- B K Sobocki, K Ka ´zmierczak Siedlecka, M Folwarski et al. “Pancreatic Cancer and Gut Microbiome- Related Aspects: A Comprehensive Review and Dietary Recommendations. ”. Nutrients, 2021.

- C Edderkaoui, B Chheda and Soufi. “An Inhibitor of GSK3B and HDACs Kills Pancreatic Cancer Cells and Slows Pancreatic Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Mice”. Gastroenterology, 2018.

- Donohoe, D.R.; Collins, L.B.; Wali, A.; Bigler, R.; Sun, W.; Bultman, S.J. The Warburg Effect Dictates the Mechanism of Butyrate-Mediated Histone Acetylation and Cell Proliferation. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 612–626. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.S.B.; Raes, J.; Bork, P. The Human Gut Microbiome: From Association to Modulation. Cell 2018, 172, 1198–1215. [CrossRef]

- Brevi, A.; Zarrinpar, A. Live Biotherapeutic Products as Cancer Treatments. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1929–1932. [CrossRef]

- Kartal E, Schmidt TSB, Molina-Montes E, et al. A faecal microbiota signature with high specificity for pancreatic cancer; Gut 2022;71:1359-1372.

- Chen, D.; Wu, J.; Jin, D.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation in cancer management: Current status and perspectives. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 2021–2031. [CrossRef]

- Santana, A.B.; Souto, B.S.; Santos, N.C.d.M.; Pereira, J.A.; Tagliati, C.A.; Novaes, R.D.; Corsetti, P.P.; de Almeida, L.A. Murine response to the opportunistic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in gut dysbiosis caused by 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Life Sci. 2022, 307, 120890. [CrossRef]

- H R Wardill, S A R Van Der Aa, A R Da Silva Ferreira et al. “Antibiotic-induced disruption of the micro- biome exacerbates chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea and can be mitigated with autologous faecal microbiota transplantation”. Eur J Cancer., vol. 153, 27–39, 2021.

- L. Derosa, B. Routy, A. Desilets et al. “Microbiota-Centered Interventions: The Next Breakthrough in Immuno-Oncology?”. Cancer Discov., pages 2396–2412, 2021.

- Selvanesan, B.C.; Chandra, D.; Quispe-Tintaya, W.; Jahangir, A.; Patel, A.; Meena, K.; Da Silva, R.A.A.; Friedman, M.; Gabor, L.; Khouri, O.; et al. Listeria delivers tetanus toxoid protein to pancreatic tumors and induces cancer cell death in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabc1600–eabc1600. [CrossRef]

- Kim JE, Phan TX, Nguyen VH et al. “Salmonella typhimurium suppresses tumor growth via the pro- inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1beta”. Theranostics, vol. 5, no. 12, 1328–1342, 2015.

- Peng Z and Cheng S, Kou Y, Wang Z and Jin R, Hu H et al. “The gut microbiome is associated with clinical response to anti-pd-1/pd-L1 immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer.”. Cancer Immunol Res, vol. 8, no. 10, 1251–1261, 2020.

- Sethi, V.; Kurtom, S.; Tarique, M.; Lavania, S.; Malchiodi, Z.; Hellmund, L.; Zhang, L.; Sharma, U.; Giri, B.; Garg, B.; et al. Gut Microbiota Promotes Tumor Growth in Mice by Modulating Immune Response. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 33–37.e6. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.M.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Gauthier, J.; Beveridge, M.; Pope, J.L.; Guijarro, M.V.; Yu, Q.; He, Z.; Ohland, C.; Newsome, R.; et al. Intestinal microbiota enhances pancreatic carcinogenesis in preclinical models. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 1068–1078. [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Saijo, K.; Komine, K.; Otsuki, Y.; Ohuchi, K.; Sato, Y.; Okita, A.; Takahashi, S.; Shirota, H.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Antibiotic therapy augments the efficacy of gemcitabine-containing regimens for advanced cancer: a retrospective study. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, ume 11, 7953–7965. [CrossRef]

- Halle-Smith, J.M.; Pearce, H.; Nicol, S.; Hall, L.A.; Powell-Brett, S.F.; Beggs, A.D.; Iqbal, T.; Moss, P.; Roberts, K.J. Involvement of the Gut Microbiome in the Local and Systemic Immune Response to Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 996. [CrossRef]

- Vrieze A, Out C, Fuentes S et al. “Impact of oral vancomycin on gut microbiota, bile acid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity.”. J Hepatol., vol. 60, no. 4, 824–831, 2014.

- Dambuza, I.M.; Brown, G.D. Fungi accelerate pancreatic cancer. Nature 2019, 574, 184–185. [CrossRef]

- Billamboz, M.; Jawhara, S. Anti-Malassezia Drug Candidates Based on Virulence Factors of Malassezia-Associated Diseases. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2599. [CrossRef]

- R T Schooley, B Biswas, J J Gill et al. “Development and use of personalized bacteriophage-based therapeu- tic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection”. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, no. 10, 61–61, 2017.

- L K Harada, E C Silva, W F Campos et al. “Biotechnological Applications of Bacteriophages”. Microbiol. Res., 2018.

- Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Hohmann N, Schmidt T et al. “A phase 1 trial extension to assess immunologic efficacy and safety of prime-boost vaccination with vxm01, an oral T cell vaccine against vegfr2, in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer”. Oncoimmunology, vol. 7, no. 4, 2018.

- Schmitz-Winnenthal, F.H.; Hohmann, N.; Niethammer, A.G.; Friedrich, T.; Lubenau, H.; Springer, M.; Breiner, K.M.; Mikus, G.; Weitz, J.; Ulrich, A.; et al. Anti-angiogenic activity of VXM01, an oral T-cell vaccine against VEGF receptor 2, in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. OncoImmunology 2015, 4, e1001217. [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Picozzi, V.; Greten, T.F.; Crocenzi, T.; Springett, G.; Morse, M.; Zeh, H.; Cohen, D.; Fine, R.L.; et al. Safety and Survival With GVAX Pancreas Prime and Listeria Monocytogenes–Expressing Mesothelin (CRS-207) Boost Vaccines for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1325–1333. [CrossRef]

- Le DT, Picozzi VJ, Ko AH et al. “Results from a phase iib, randomized, multicenter study of gvax pancreas and crs-207 compared with chemotherapy in adults with previously treated metastatic pancreatic adenocar- cinoma (Eclipse study)”. Clin Cancer Res, vol. 25, no. 18, 2019.

- Fanijavadi, S.; Thomassen, M.; Jensen, L. H. Targeting Triple NK Cell Suppression Mechanisms: A Comprehensive Review of Biomarkers in Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. Preprints 2024, 2024121161. [CrossRef]

| Taxonomy | Role, NK cell affection | Translational Clinical Application/Suggestion |

|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria (phylum) | Protective in the oral microbiome. Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome)52, 67, 85. | Phylum regulation in the oral and gut microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Acidovorax Ebreus; A. ebreus (species, genus: Acidovorax, phylum: proteobac) | Carcinogenic by reducing immune cells 4,10,18,19,20. | Species depletion through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Acinobacter baumannii (species; genus: Acinobacter, phylum: Proteobacteria) |

Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome 52, 67. | Intra-tumor species depletion through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Actinomyces (genus; phylum: Actinobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the oral and gut microbiome 20, 85, 104. Negative prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. |

Genus depletion in the intra-tumoral, intra-gut, and oral microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Aggregatibacter (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Negative prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Intra-tumor genus depletion through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (species; genus: Aggregatibacter phylum: proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome by promoting tumor favoring inflammation and NK cell exhaustion 4, 10, 16,1 8, 19, 20, 29, 52 | Species depletion in the oral microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Akkermansia muciniphila (species; genus: Akkermansia, phylum: verrucomicrobia) | Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome. Protective in the gut microbiome by decreasing NK cell exhaustion and positive predictive marker for immunotherapy 4,10,16,18,19,20,148. | Increasing species abundance, for example, by prescribing NGPs as adjuvants for immunotherapy to enhance the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors 133,134. |

| Alistipes shahii (species; genus: Alistipes, phylum: Bacteriodetes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 6. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Alloprevotella (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 104. | Increasing genus abundance, for example, by prescribing NGPs, probiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Alloscardovia omnicolens (species; genus: Alloscardovia, phylum: Actinobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 148. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Altidipes indistinctus (species; genus: Altidipes; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Positive predictive marker for immunotherapy and response to IL-10+CpG oligonucleotide. Protective by decreasing NK cell exhaustion 4,10,16,17,18,19,20,133,134. | Increasing species abundance, for example, by prescribing NGPs, probiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy or as adjuvants for immunotherapy or IL-10+CpG oligonucleotide to enhance the efficacy. |

| Alternaria alternata (species; genus: Alternaria, phylum: Ascomycota) | Carcinogenic by enhancing tumor favoring immunity, inducing NK cell exhaustion 4,10,19,18,20. | Species depletion through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Anaerostipes (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome) 8, 109. | Increasing genus abundance, for example, by prescribing NGPs, probiotics, FM, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Atopobium parvulum (species; genus: Atopobium; phylum: Actinobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome) 38. | Species depletion in the oral microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Bacidiomycota (phylum of fungi) | Carcinogenic by activating mannose binding lectin, suppressing NK cells cytotoxicity 83. | Phylum depletion through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Bacillus clausii (species; genus: Bacillus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the intratumor microbiome 15. | Increasing species abundance, for example, by prescribing tumor-colonizing bacteria, oral probiotics, FM, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Bacteroidales (order; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome) 109. | Order depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Bacteroides (genus; phylum: bacteroidetes) |

Carcinogenic in the oral, gut and intratumor microbiome 105, 148. PIPN inducer, activating Astrocytes and TLR4/p38MAPK Pathway, with effects on NK cell regulation 6, 97, 98. |

Genus depletion in the intra-tumoral, intra-gut, and oral microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Bacteroides coprocola (species; genus: Bacteroides, phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 148. | Increasing species abundance in the gut for example, by prescribing oral probiotics, FMT, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Bacteroidetes (phylum) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 52. | Phylum depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Bifidobacterium (genus; phylum: Actinobacteria) | Protective in the gut microbiome 8. It can increase NKA2,64 and acts as a positive predictive biomarker for immunotherapy to potentiate the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors63,64, 134. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy or as adjuvants for immunotherapy to potentiate its effect. |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum (species; genus: Bifidobacterium, phylum: Actinobacteria) | Protective in the gut microbiome 148. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum(species; genus: Bifidobacterium, phylum: Actinobacteria) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Blautia (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 8. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Blautia obeum (species; genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Bradyrhizobium (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Increasing genus abundance in the intratumor microbiome, for example, by prescribing tumor-colonizing bacteria, FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Capnocytophaga (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 20. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Cardiobacterium (genus; phylum: Proteobacterium) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 52. | Genus depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Citrobacter (genus; phylum: Protecobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome 66. | Genus depletion in the intratumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Citrobacter freundii (species; genus: Citrobacter, phylum: proteobacteria) |

Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome, contributing to immunosuppression, upregulation of oncogenic pathways, and downregulation of tumor suppressive pathways 3,19,55,104. | Species depletion in the intra-tumoral, through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Cladocopium symbiosum (species; genus: Cladocopium, phylum: Apicomplexa) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 6. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Clostridiaceae (family; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 15. | Increasing family abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy and so on. |

| Clostridiales (order; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 109. | Increasing order abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Clostridium (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) |

Protective in the gut microbiome, 109 negative prognostics in gut and oral sample15,17 but protective intratumorally 147. | Reducing abundance in gut and oral samples using probiotics, while increasing intratumoral abundance with tumor-colonizing bacteria |

| Clostridium IV (group; genus: Clostridium, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 8. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome, for example, by prescribing FMT, NGPs, probiotics, postbiotics, lifestyle changes, vitamin therapy. |

| Clostridium bolteae (species; genus: Clostridium, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 6. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Clostridium_sensu stricto 1 (species; genus: Clostridiumphylum: Firmicutes) | Negative prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16.; PIPN preventive in the gut microbiome, interfering with astrocytes and the TLR4/p38MAPK pathway 97,98. | Increasing species abundance in the gut through FMT to reduce PIPN, while promoting intratumoral abundance with tumor-colonizing bacteria |

| Collinsella aerofaciens (species; genus: Collnisella, phylum: Actinobacteria) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Corynebacterium (genus; phylum: Actinobacteria) | PIPN preventive, by interfering with astrocytes and the TLR4/p38MAPK pathway 97,98. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut through FMT to reduce PIPN, while promoting intratumoral abundance with tumor-colonizing bacteria. |

| Coprococcus (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6,8. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Desulfovibrio (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Increasing intratumoral abundance through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using tumor-colonizing bacteria. |

| Dialister (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 85. | Reducing genus abundance in the oral microbiome using direct and indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Escherichia coli (species; genus: Escherichia, Phylum: Proteobacteria) |

Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 20, decreasing NK cell cytotoxicity 93, and inducing diarrhea by reducing IL-22 production in NK cells, which normally protect the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier damaged by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Negative predictive marker for gemcitabine response 46, 67. |

Reducing species abundance in the oral microbiome using direct and indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. For example, Lactobacillus probiotics can be used to increase gemcitabine efficacy and prevent diarrhea |

| Elizabethkingia (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Carcinogenic 55. | Genus depletion through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Enhydrobacter (genus; phylum: Proteobacterai) | Positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Increasing intratumoral abundance through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using tumor-colonizing bacteria. |

| Enterobacter (genus; phylum: Proteocteria) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 8; protective intratumorally, with TIGIT upregulation31-32. | Genus depletion through direct and indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. Increasing intratumoral abundance using direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting approaches, such as tumor-colonizing bacteria. |

| Enterobacter asburiae (species; genus: Enterobacter, phylum: Poteobacteria) |

Carcinogenic in the gut and intratumor microbiome28, 104. | Species depletion in the gut and intra-tumor microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Enterobacteriaceae (family; phylum: Proteobacteria) |

Carcinogenic in the oral and intratumor microbiome 20, 57, 67. |

Species depletion in the gut and intra-tumor microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Enterococcus hirae (species; genus: Enterococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Positive predictive for immunotherapy response 63. | Increasing species abundance through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies or prescribing the species as a probiotic product to be used as adjuvant therapy for immunotherapy. |

| Erysipelotrichaeceae (family; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6. | Increasing family abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using FMT. |

| Eubacterium hallii (speies; genus: Eubacterium, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using FMT. |

| Eubacterium ventriosum (species; genus: Eubacterium, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome85. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using FMT. |

| Faecalibacterium (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 109. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using FMT. |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (species; genus: Faecalibacterium; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 85, 148 | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as using FMT. |

| Firmicutes (phylum) | Protective in the gut microbiota 51, reducing bile acid production and bile acid induced carcinogenesis, while increasing NK cell activity through bile acid reduction and butyrate production 73,85,1034 110, 145 | Phylum regulation in the gut and intra-tumor microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies |

| Flavobacterium (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Increasing genus abundance in the intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as tumor-colonizing bacteria. |

| Flavonifractor (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 8. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as FMT. |

| Fusobacterium (genus; Fusobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 105. | Species depletion in the oral microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum (species; genus: Fusobacterium, phylum: Fusobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the gut and intratumor microbiome via cytokine secretion and decreased NK cell tumor infiltration, serving as a negative prognostic marker intratumorally 19, 27, 28, 29, 74,104,107,148. | To decrease the species using probiotics to optimize clinical outcomes, particularly to potentiate the effects of 5-FU and oxaliplatin. |

| Gammaproteobacteria (class; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome67, a negative predicative marker for gemcitabine response 28,66,67 due to bacterial CDA, and for immunotherapy, while serving as a positive predicative marker for chemotherapy (e.g., 5-FU and oxaliplatin); immune regulation via CDA102, 104, 105. | To be prescribed as tumor-colonizing bacteria alongside oxaliplatin and 5-FU-based chemotherapy to potentiate their effects. Probiotics can be used to reduce species abundance when gemcitabine is prescribed. |

| Granulicatella adiacens (species; genus: Granulicatella, Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 38. | Species depletion in the oral microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Haemophilus abundance (species; genus: Haemophilus, phylum: Proteobacterai) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 57. | Species depletion in the oral microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Helicobacter hepaticus (species; genus: Helicobacter, phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogen (seroprevalence), protective intratumorally, increasing NK cell tumor infiltration 28,29. | Patients who are seropositive for H. hepaticus have a higher risk of progression and may benefit from receiving the species as tumor-colonizing bacteria to induce NK cell infiltration. |

| Helicobacter pylori (species; genus: Helicobacter, phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic, with NK cell suppression 124, 125. | Eradicating H. pylori using antibiotics or probiotics. Alternatively, using Interleukin 12 in patients with dysbiosis positive for H. pylori to induce gamma interferon activation and enhance NK cell activity. |

| Herbaspirillum (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome 49. | Genus depletion in the intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Klebsiella (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the gut and intratumor microbiome 8, 52, 67. | Genus depletion in the gut and intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (species; genus: Proteobacteria, phylum: proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the gut and intratumor microbiome 19, 104, leading to NK cell suppression 6,125. | Species depletion in the gut and intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Lachnospiraceae (family; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome in some studies 6, 85, but carcinogenic in the oral and gut microbiome, reported by another study 57, 109. | Further investigation is needed to specify the strain-level effects and determine the clinical relevance, as well as to regulate dysbiosis accordingly. |

| Lactobacillus (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the oral and gut microbiome 6,104. | Further investigation is needed to specify the strain-level effects and determine the clinical relevance, as well as to regulate dysbiosis accordingly. |

| Lactobacillus plantarum (species; genus: Lactobacillus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome, while carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome 148. | Increasing genus in the gut microbiome and reducing intratumoral abundance through direct and indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Leptotrichia (genus; phylum: Fusobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 104; however, protective in both the gut and oral microbiome, according to other studies 20, 105. | Further investigation is needed to specify the strain-level effects and determine the clinical relevance, as well as to regulate dysbiosis accordingly. |

| Listeria whelshimer I Serover 6B SLCC 5334 (strain; genus: Listeria, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective, inducing IL-12 production and NK cell activity via LPS 147, 153, 167. | It can be used as tumor-colonizing bacteria or as a vaccination to target tumor and enhance the response to gemcitabine. |

| Malassezia globosa (species of yeast; genus: Malassezia, phylum: Ascomycota) |

Carcinogen, enhancing tumor favoring immunity by suppress NK cells through the release of C3a and C5a, thereby reducing NKG2D161. | Species depletion using antifungal drugs or other direct and indirect dysbiosis-targeting modalities |

| Megamonas (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 52; positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut and intra-tumor microbiomes through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies, such as tumor-colonizing bacteria. |

| Megasphaera (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective and a positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome15,16, 105, while carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 105. | Increasing genus abundance in the intratumoral microbiome through strategies like tumor-colonizing bacteria, and depleting genus abundance in the oral microbiome using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Mycobacterium (genus; phylum: Actinobacteria) | Protective through NKp44 interaction 45,47. | Increasing genus abundance using direct and indirect dysbiosis-modulating approach. |

| Mycoplasma hyorhinis (species; genus: Mycoplasma, phylum: Mycoplasmatota) | Negative predictive marker for gemcitabine due to decreased cytotoxicity caused by bacterial CDA 28,66. | Decreasing species abundance using direct and indirect dysbiosis-modulating modalities, such as antibiotics and vaccination, to prevent gemcitabine resistance. |

| Neisseria (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Protective in the oral microbiome 105 and a negative prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Decreasing genus abundance in the intratumoral microbiome and increasing genus abundance in the oral microbiome using direct and indirect dysbiosis-modulating modalities. |

| Neisseria elongata (species; genus: Neisseria, phylum: Proteobacteria) | Protective in the oral microbiome 20,38, 104,105. | Increasing species abundance in the oral microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Odoribacter (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 109. | Genus depletion in the gut microbiome using direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting approach. |

| Parabacteroides (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 6, 52. | Genus depletion in the gut microbiome by direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting. |

| Propionibacterium acnes (species; genus: Propionibacterium, phylum: Actinobacteria) | Carcinogenic, through cytokine modulation and Hedgehog signaling activation 21-23. | Species depletion using, for example, antibiotics, bacteriophages, or other modalities to target dysbiosis. |

| Porphyromonas (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Protective in the oral microbiome20 and a negative prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome 16. | Increasing genus in the oral microbiome and reducing intratumoral abundance through direct and indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Prophyromonas gingivalis (species; genus: Prophyromonas phylum: bacteroidetes) |

Carcinogen in the oral microbiome, inducing tumor-favoring inflammation and NET induced NK cell suppression; direct effect on NK cells has not been investigated 9,16, 17, ,20 40. | Species depletion using, for example, antibiotics or other modalities to target dysbiosis. |

| Proteobacteria (phylum) | Carcinogenic in the gut and intratumor microbiomes, promoting tumor metastasis, bile acid induced carcinogenesis, and immunosuppression9,16, 17, 18, 19, 30, 37,40, 52, 104. | This phylum needs to be analyzed at the strain level, as generalizing clinical outcomes at the phylum level is not applicable due to controversial results. |

| Prevotella (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) |

Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome104, but protective in both oral and gut microbiomes 20, 52. | Further investigation is needed to specify the species-level effects and determine the clinical relevance, as well as to regulate dysbiosis accordingly. |

| Prevotella pallens (species; genus: Prevotella, phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 85. | Species depletion in the oral microbiome using modalities to target dysbiosis. |

| Prevotella sp. C561(strain; species P.sp, genus: Prevotella, phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 85. | Strain depletion in the oral microbiome using modalities to target dysbiosis. |

| Pseudomonas (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) |

Carcinogen in the intratumor microbiome 45, 47, 49, 150. | Genus depletion in the intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Pseudomonadaceae (family; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome 66. | Family depletion in the intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies; however, further investigation at the species level is recommended. |

| Pseudomonas aeroginosa (species; genus: Pseudomonas, phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic 45, 47, 150. | Species depletion in the intra-tumor microbiome through direct or indirect dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Pseudoxanthomonas (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Protective as the intratumor microbiome, triggering antitumor immunity and serving as a positive prognostic marker12,15. | Increasing genus abundance in the intratumoral microbiome through strategies like tumor-colonizing bacteria or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Romboutsia timonensis (species; genus: Romboutsia, Phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 148. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through strategies like FMT or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Rothia (genus; phylum: Actinobacteria) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 20. | Genus depletion in the oral microbiome by targeting dysbiosis appropriately. |

| Ruminococcaceae (family; phylum; Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 109. | Increasing family abundance in the gut microbiome through strategies like FMT or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. However, further investigation at genus or species level is recommended. |

| Ruminococcus (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Positive predictive marker for immunotherapy and response to IL-10+CpG oligonucleotide 28,63, 131,155. |

To optimize clinical outcomes, using related targeting products to increase genus abundance and enhance tumor response to IL-10 + CpG oligodeoxynucleotide. |

| Streptococcus sanguinis (species; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 6. | Increasing species abundance in the gut microbiome through strategies like FMT or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Saccharmycetes (class; phylum: Ascomycota) | Protective, triggering antitumor immunity and serving as a positive prognostic marker 15. | Increasing class abundance through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. However, further investigation at genus or species level is recommended. |

| Saccharopolyspora (genus; Phylum: Actinobacteria) | Protective and positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome) 15 | Increasing genus abundance in the intratumoral microbiome through strategies like tumor-colonizing bacteria or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Salmonella (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) | Protective in the intratumor microbiome, activating the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1beta and promoting NK cell activation 154. | Increasing genus abundance in the intratumoral microbiome through strategies like tumor-colonizing bacteria or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Selenomonasb(genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 8, but protective in the oral microbiome 20. | Genus depletion in the gut microbiome, with an increase in the oral microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. However, further investigation at the strain level is recommended. |

| Shigella sonnei (species; genus: Shigella, phylum: Proteobacteria) | Carcinogenic due to upregulation of oncogenic pathways, immunosuppression, and TME reprogramming 17. | Species depletion: however, further investigation at the strain level, particularly regarding oral-gut-intratumoral interactions and their clinical effects, is recommended. |

| Solobacterium (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 85. | Genus depletion in the oral microbiome by targeting dysbiosis appropriately. |

| Sphingomonas (genus; phylum: Proteobacteria) |

Carcinogenic in the intratumor microbiome49; protective and a positive prognostic marker in the gut microbiome15,16. |

Genus depletion in the intra-tumor microbiome and increasing in the gut microbiome by targeting dysbiosis appropriately. |

| Spirochaeta (genus; phylum: Spirochaetes) | Protective and positive prognostic marker in the intratumor microbiome)15,16, but carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 105. | Genus depletion in the oral microbiome, with an increase in the intratumor microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Streptococcus (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the oral, intratumor and gut microbiomes 20, 66. | Genus depletion in the oral, intratumor and gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. However, further investigation at species and strain level is recommended. |

| Streptococcus mitis (species; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 20. | Increasing genus abundance in the oral microbiome through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Streptococcus anginosus (sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 85. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Streptococcus australis (sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 85. | Increasing species abundance in the oral microbiome through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Streptococcus mutans (sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 6. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Streptococcus oralis (sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 85. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Streptococcus salivarius (sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 85. | Increasing species abundance in the oral microbiome through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Streptococcus thermophilus (sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 85. | Increasing species abundance in the oral microbiome through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Streptococcus vestibularis(sepecies; genus: Streptococcus, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 85. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Streptomyces (genus; phylum: actinobacteria) | Protective in the intratumor microbiome, triggering antitumor immunity and NK cell infiltration 48; positive prognostic marker 15. | Increasing genus abundance in the intratumoral microbiome through strategies like tumor-colonizing bacteria or other appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Subdoligranulum (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Protective in the gut microbiome 109. | Increasing genus abundance in the gut microbiome through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Tannerella (genus; phylum: Bacteroidetes) | Protective in the oral microbiome 20. | Increasing genus abundance in the oral microbiome through appropriate dysbiosis-targeting approaches. |

| Treponema (genus; phylum: Spirochaetes) | Carcinogenic in the oral microbiome 105. | Genus depletion in the oral microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Turicibacter (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | PIPN preventive, interfering with astrocytes and TLR4/p38MAPK pathway, and regulating NK cell function 97,98,100. | The genus needs to be increased in the gut to reduce PIPN, using, for example, FMT or other appropriate approaches to target dysbiosis. |

| UCG-005 (genus, Phylum: Firmicutes) | PIPN Inducer, activating astrocytes and the TLR4/p38MAPK pathway, and regulating NK cell 97,98,100. | The genus needs to be decreased in the gut to reduce PIPN, using, for example, antibiotics, dietary changes, or other appropriate approaches to target dysbiosis. |

| Veillonella (genus; phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 8, 52. | Genus depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Veillonella atypica (species; genus: Veillonella, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogenic in the gut microbiome 85, 148. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

| Veillonella parvula(species; genus: Veillonella, phylum: Firmicutes) | Carcinogen in the gut microbiome 85. | Species depletion in the gut microbiome, using appropriate dysbiosis-targeting strategies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).