Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

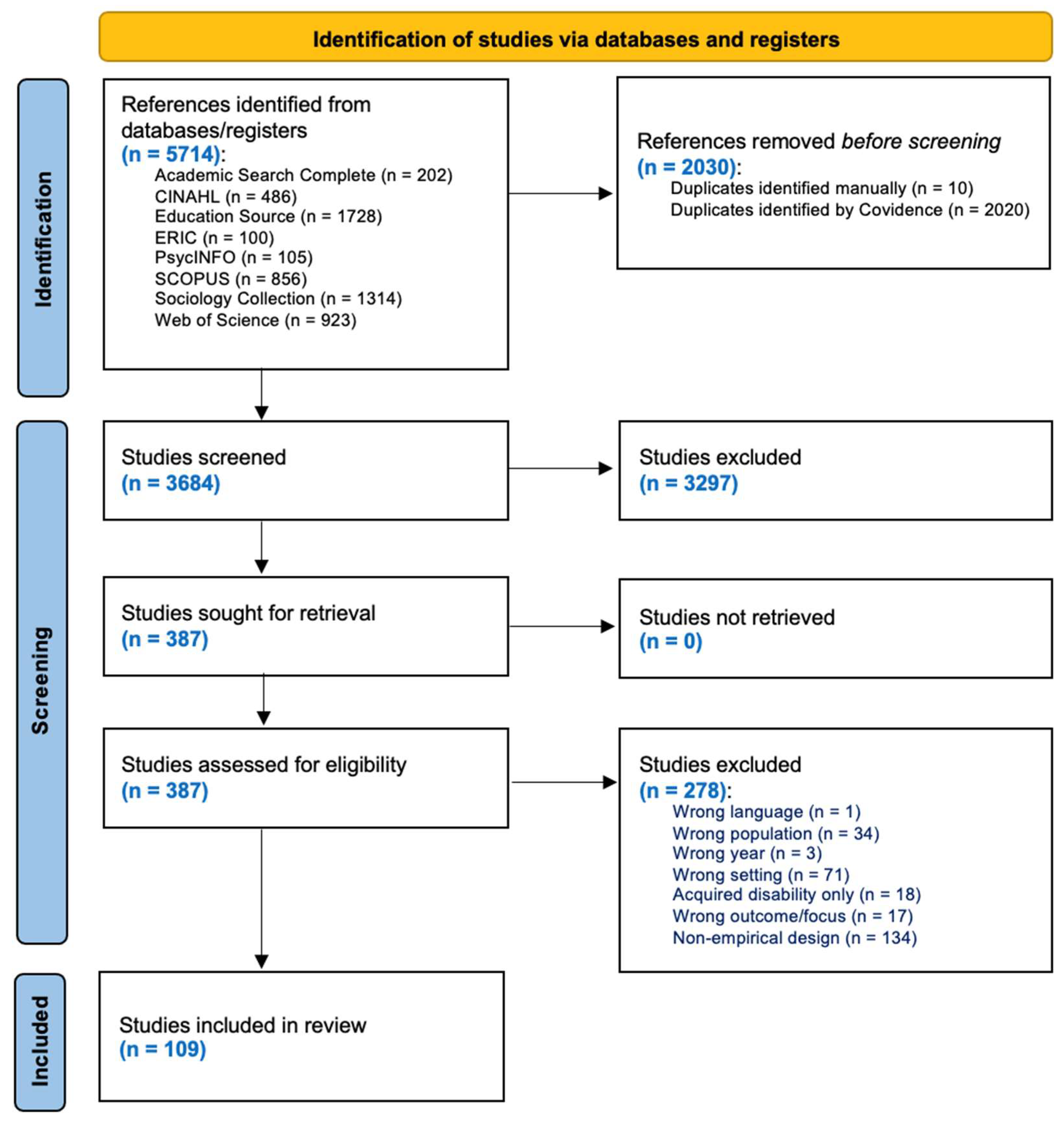

Background: Ableism obstructs employment equity for disabled individuals. However, despite protective legislation, research lacks a comprehensive understanding of how ableism multidimensionally manifests across job types, disability types, stages of employment, and intersecting identities. Objectives: This scoping review examined how ableism affects disabled workers and jobseekers, as well as its impacts on employment outcomes, variations across disabilities and identities, and best practices for addressing these. Eligibility Criteria: Included articles were 109 peer-reviewed, empirical studies conducted in the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the UK, Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland between 2018 and 2023. Sources of Evidence: Using terms related to disability, ableism, and employment, databases searched included Sociology Collection, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Education Source, Academic Search Complete, and ERIC. Charting Methods: Data were extracted in tabular form and analyzed through thematic narrative synthesis to identify study characteristics, ableist barriers within employment, intersectional factors, and best practices. Results: Ableism negatively impacted employment outcomes through barriers within the work environment, challenges disclosing disability, insufficient accommodations, and workplace discrimination. Intersectional factors intensified inequities, particularly for BIPOC, women, and those with invisible disabilities. Conclusions: Systemic, intersectional strategies are needed to address ableism, improve policies, and foster inclusive workplace practices.

Keywords:

Introduction

- How does ableism manifest itself in employment contexts (e.g., barriers to employment across the employment cycle, discrimination, workplace culture, disclosure)?

- How does ableism affect employment outcomes for disabled workers and job-seekers (e.g., pay, rates of employment, workload)?

- What differences exist across various types of disabilities, and how do intersectional factors (e.g., race, gender) influence these experiences?

- What best practices identified in the literature, such as workplace interventions, standards, policies, and legal frameworks, effectively address ableism in employment and promote inclusion?

Materials & Methods

Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Results

Study Characteristics

Impact on Employment Outcomes

Barriers in Relation to the Work Environment

Experiences of Workplace Discrimination

Difficulty Obtaining Workplace Accommodations

Difficulty with Disability Disclosure

Nuances Across Various Stages of Employment

Intersectional Findings

Best Practices

Discussion

Significance and Implications of Findings

Recommendations for Practice

Future Research

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability Statement

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Supplementary Materials

References

- Adams, C.; Corbin, A.; O’Hara, L.; Park, M.; Sheppard-Jones, K.; Butler, L.; Umeasiegbu, V.; McDaniels, B.; Bishop, M.L. A qualitative analysis of the employment needs and barriers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in rural areas. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 2019, 50, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, M.; Kurtzberg, T.R. The disclosure dilemma: Requesting accommodations for chronic pain in job interviews. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2022, 16, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameri, M.; Schur, L.; Adya, M.; Bentley, F.S.; McKay, P.; Kruse, D. The disability employment puzzle: A field experiment on employer hiring behavior. ILR Review 2018, 71, 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awsumb, J.; Schutz, M.; Carter, E.; Schwartzman, B.; Burgess, L.; Lounds Taylor, J. Pursuing paid employment for youth with severe disabilities: Multiple perspectives on pressing challenges. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 2022, 47, 22–39. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=155467238&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Ballan, M.S.; Freyer, M. Occupational deprivation among female survivors of intimate partner violence who have physical disabilities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2020, 74, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudry, J.S. , & Miller, L.E. (2016). Research design in the social sciences: Interdisciplinary approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Bend, G.L. , & Priola, V. (2018). What about a career? the intersection of gender and disability. (pp. 193-208). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bendick, M. Employment discrimination against persons with disabilities: Evidence from matched pair testing. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations 2018, 17, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.; Rumrill, S.P. The employment impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on americans with MS: Preliminary analysis. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2021, 54, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.H.; Mahdi, S.; Milbourn, B.; Scott, M.; Gerber, A.; Esposito, C.; Falkmer, M.; Lerner, M.D.; Halladay, A.; Ström, E.; D’Angelo, A.; Falkmer, T.; Bölte, S.; Girdler, S. Multi-informant international perspectives on the facilitators and barriers to employment for autistic adults. Autism Research 2020, 13, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.H.; Mahdi, S.; Milbourn, B.; Thompson, C.; D’Angelo, A.; Ström, E.; Falkmer, M.; Falkmer, T.; Lerner, M.; Halladay, A.; Gerber, A.; Esposito, C.; Girdler, S.; Bölte, S. Perspectives of key stakeholders on employment of autistic adults across the united states, australia, and sweden. Autism Research 2019, 12, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, S.; Connelly, C.E.; Gellatly, I.R.; Jetha, A.; Martin Ginis, K.A. The participation of people with disabilities in the workplace across the employment cycle: Employer concerns and research evidence. Journal of Business and Psychology 2019, 35, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, S.; Price, E.; Walker, E. Fluctuation, invisibility, fatigue – the barriers to maintaining employment with systemic lupus erythematosus: Results of an online survey. Lupus 2018, 27, 2284–2291. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=133124564&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosua, R. , & Gloet, M. (2021). Access to flexible work arrangements for people with disabilities: An australian study. (pp. 134-161). Business Science Reference/IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Systematic Reviews 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bross, L.A.; Patry, M.B.; Leko, M.; Travers, J.C. Barriers to competitive integrated employment of young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Education & Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities 2021, 56, 394–408. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=153520061&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Bruyère, S.M. Chang, H., Saleh, M.C., & Cornell University, K Lisa Yang and Hock E Tan Institute on Employment,and Disability. (2020). Preliminary report summarizing the results of interviews and focus groups with employers, autistic individuals, service providers, and higher education career counselors on perceptions of barriers and facilitators for neurodiverse individuals in the job I. ().K. Lisa Yang and Hock E. Tan Institute on Employment and Disability. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eric&AN=ED608278&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Button, P. Expanding employment discrimination protections for individuals with disabilities: Evidence from california. ILR Review 2018, 71, 365–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, K.; Parker Harris, S.; Renko, M. Inclusive management for social entrepreneurs with intellectual disabilities: “How they act”. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2020, 33, 204–218. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=141781157&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Carolan, K.; Gonzales, E.; Lee, K.; Harootyan, R.A. Institutional and individual factors affecting health and employment for low-income women with chronic health conditions. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences 2020, 75, 1062–1071. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=143175792&site=ehos t-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Carr, D.; Namkung, E.H. Physical disability at work: How functional limitation affects perceived discrimination and interpersonal relationships in the workplace. Journal of Health & Social Behavior 2021, 62, 545–561. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=154067726&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Cavanagh, J.; Meacham, H.; Pariona-Cabrera, P.; Bartram, T. Subtle workplace discrimination inhibiting workers with intellectual disability from thriving at the workplace. Personnel Review 2021, 50, 1739–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, T.; Rouxel, P. The role of workplace accommodations in explaining the disability employment gap in the UK. Social Science & Medicine 2021, 285. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=152163771&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Chordiya, R. Organizational inclusion and turnover intentions of federal employees with disabilities. Review of Public Personnel Administration 2022, 42, 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, D.; Lund, E.M.; Carey, C.D.; Li, Q. Intersection of discriminations: Experiences of women with disabilities with advanced degrees in professional sector in the united states. Rehabilitation Psychology 2022, 67, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cmar, J.L.; Steverson, A. Job-search activities, job-seeking barriers, and work experiences of transition-age youths with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 2021, 115, 479–492. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=154122931&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Delman, J.; Adams, L.B. Barriers to and facilitators of vocational development for black young adults with serious mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2022, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, A.; Shields, M.; Dimov, S.; Dickinson, H.; Vaughan, C.; Bentley, R.; Lamontagne, A.D.; Kavanagh, A. Australia’s disability employment services program: Participant perspectives on factors influencing access to work. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djela, M. Change of autism narrative is required to improve employment of autistic people. Advances in Autism 2021, 7, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, J.N.; Bates, F.M. Hiring and employing individuals with psychiatric disabilities: Focus groups with human resource professionals. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2019, 50, 85–93. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=134378875&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Mamboleo, G. Factors associated with requesting accommodations among people with multiple sclerosis. Work 2022, 71, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Eto, O.; Spitz, C. Barriers and facilitators to requesting accommodation among individuals with psychiatric disabilities: A qualitative approach. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2021, 55, 207–218. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=152820781&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Mullins, M.; Ostrowicz, I. Factors influencing workplace accommodations requests among employees with visual impairments. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling 2021, 27, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M. , Coutu, M., Tremblay, D., Sylvain, C., Gouin, M., Bilodeau, K., Kirouac, L., Paquette, M., Nastasia, I., & Coté, D. Insights into the sustainable return to work of aging workers with a work disability: An interpretative description study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2021, 31, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethridge, G.; Dowden, A.R.; Brooks, M.; Kwan, N.; Harley, D. Employment and earnings among ex-offenders with disabilities: A multivariate analysis of RSA-911 data. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2020, 52, 279–289. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=142832377&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Filia, K.M.; Cotton, S.M.; Watson, A.E.; Jayasinghe, A.; Kerr, M.; Fitzgerald, P.B. Understanding the barriers and facilitators to employment for people with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Quarterly 2021, 92, 1565–1579. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=153159032&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C. (2019). Ableism, racism, and subminimum wage in the united states. Disability Studies Quarterly, 39, N.PAG. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=140338905&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Friedman, C.; Rizzolo, M.C. Fair-wages for people with disabilities: Barriers and facilitators. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2020, 31, 152–163. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=146871673&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Fyhn, T.; Sveinsdottir, V.; Reme, S.E.; Sandal, G.M. A mixed methods study of employers’ and employees’ evaluations of job seekers with a mental illness, disability, or of a cultural minority. Work 2021, 70, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Aylott, J.; Giri, P.; Ferguson-Wormley, S.; Evans, J. Lived experience and the social model of disability: Conflicted and inter-dependent ambitions for employment of people with a learning disability and their family carers. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 2022, 50, 98–106. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=155361181&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Gobelet, C. , Franchignoni, F., SpringerLink ebooks - Medicine, & Ebook Central. (2006;2005;). Vocational rehabilitation. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.W. , Inge, K.J., Wehman, P., Seward, H.E., Bogenschutz, M.D., Inge, & Wehman. Barriers and facilitators to employment as reported by people with physical disabilities: An across disability type analysis. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2018, 48, 207–218. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=128962794&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Graham, K.M.; McMahon, B.T.; Jeong, H.K.; Simpson, P.; McMahon, M.C. Patterns of workplace discrimination across broad categories of disability. Rehabilitation Psychology 2019, 64, 194–202. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=135871622&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenawalt, T.A.; Friefeld Kesselmayer, R.; Degeneffe, C.E. Employment and service system challenges affecting persons with cognitive disabilities: A qualitative inquiry into rehabilitation counselor perspectives. Journal of Rehabilitation 2021, 87, 17–27. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=ccm&AN=154632432&site=ehost-live&custid=s5672194.

- Gupta, S.; Sukhai, M.; Wittich, W. Employment outcomes and experiences of people with seeing disability in canada: An analysis of the canadian survey on disability 2017. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–17. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=153842672&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampson, M.E.; Watt, B.D.; Hicks, R.E. Impacts of stigma and discrimination in the workplace on people living with psychosis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, C.; Taylor, T. Workplace experiences of women with disability in sport organizations. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardonk, S.; Halldórsdóttir, S. Work inclusion through supported employment? perspectives of job counsellors in iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 2021, 23, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, P.; French, B.; Bales, R. The model of disability human rights monitoring, workplace discrimination, and the role of trade unions. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 2019, 35, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.M. , McVilly, K.R., & Stokes, M.A. ’Always a glass ceiling’ gender or autism; the barrier to occupational inclusion. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2018, 56, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, D.; Spoor, J.R.; Cai, R.Y.; Uljarevic, M.; Bury, S.; Gal, E.; Moss, S.; Richdale, A.; Bartram, T.; Dissanayake, C. Supportive employment practices: Perspectives of autistic employees. Advances in Autism 2021, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, Å, Boman, E. , Kristofferzon, M., & Nilsson, A. Beliefs about return to work among women during/after long-term sick leave for common mental disorders: A qualitative study based on the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2021, 31, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henly, M.; Brucker, D.L. More than just lower wages: Intrinsic job quality for college graduates with disabilities. Journal of Education & Work 2020, 33, 410–424. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=147756195&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Hernández González, C.A. Market reactions to the inclusion of people with disabilities. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 2021, 41, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, L.M.; Agarwal, R.; Gonzalez, I.; Li, T.; Garcia, S.; Maddux, M.; Attong, N.; Burke, S.L. Understanding local barriers to inclusion for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities through an employment conference. International Journal of Disability Management 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmlund, L.; Hellman, T.; Engblom, M.; Kwak, L.; Sandman, L.; Törnkvist, L.; Björk Brämberg, E. Coordination of return-to-work for employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: Facilitators and barriers. Disability & Rehabilitation 2020, 1–9. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=147374762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Hoque, K.; Bacon, N. Working from home and disabled people’s employment outcomes. British Journal of Industrial Relations 2022, 60, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, J.L. , & Pitts, M.M. Pandemic repercussions for employment among disabled individuals. National Bureau of Economic Research 2023. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w30640.

- Hughes, J.; Sharp, C. Identifying key databases for systematic and scoping reviews in social sciences: Insights and recommendations. Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 2021, 45, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M.E.; Rose, G.M.; Trip, H. Registered nurses’ experiences and perceptions of practising with a disability. Kai Tiaki Nursing Research 2021, 12, 7–15. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=ccm&AN=154034608&site=ehost-live&custid=s5672194.

- Inge, K.J.; Bogenschutz, M.D.; Erickson, D.; Graham, C.W.; Wehman, P.; Seward, H. Barriers and facilitators to employment: As reported by individuals with spinal cord injuries. Journal of Rehabilitation 2018, 84, 22–32. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=130519270&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Iwanaga, K.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Lee, B.; Chan, F.; Bezyak, J.; Grenawalt, T.A.; Tansey, T.N. Assessing disability inclusion climate in the workplace: A brief report. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2018, 49, 265–271. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=134558344&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Jarus, T.; Bezati, R.; Trivett, S.; Lee, M.; Bulk, L.Y.; Battalova, A.; Mayer, Y.; Murphy, S.; Gerber, P.; Drynan, D. Professionalism and disabled clinicians: The client’s perspective. Disability & Society 2019, 35, 1085–1102. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=145036062&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Jetha, A.; Bowring, J.; Furrie, A.; Smith, F.; Breslin, C. Supporting the transition into employment: A study of canadian young adults living with disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2019, 29, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.M. , Finkelstein, R., & Koehoorn, M. 0187 Disability and workplace harassment and discrimination among canadian federal public service employees. Occupational and Environmental Medicine (London, England) 2017, 74 (Suppl 1), A56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatzadeh-Mahani, A.; Wittevrongel, K.; Nicholas, D.B.; Zwicker, J.D. Prioritizing barriers and solutions to improve employment for persons with developmental disabilities. Disability & Rehabilitation 2020, 42, 2696–2706. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=145732362&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Kiesel, L.R.; Dezelar, S.; Lightfoot, E. Equity in social work employment: Opportunity and challenge for social workers with disabilities in the united states. Disability & Society 2019, 34, 1399–1418. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=141601067&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Kim, E.J.; Skinner, T.; Parish, S.L. A study on intersectional discrimination in employment against disabled women in the UK. Disability & Society 2020, 35, 715–737. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=144303873&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Krause, J.S.; Li, C.; Backus, D.; Jarnecke, M.; Reed, K.; Rembert, J.; Rumrill, P.; Dismuke-Greer, C. Barriers and facilitators to employment: A comparison of participants with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 2021, 102, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, Y.; Bento JP, C. Workplace adaptations promoting the inclusion of persons with disabilities in mainstream employment: A case-study on employers’ responses in norway. Social Inclusion 2018, 6, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C. Resisting ableism in deliberately developmental organizations: A discursive analysis of the identity work of employees with disabilities. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2021, 32, 179–196. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=150670271&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Ditchman, N.; Thomas, J.; Tsen, J. Microaggressions experienced by people with multiple sclerosis in the workplace: An exploratory study using Sue’s taxonomy. Rehabilitation psychology 2019, 64, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos C d Kranios, A.; Beauchamp-Whitworth, R.; Chandwani, A.; Gilbert, N.; Holmes, A.; Pender, A.; Whitehouse, C.; Botting, N. Awareness of developmental language disorder amongst workplace managers. Journal of Communication Disorders 2022, 95. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=155018102&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Leslie, M.J.; McMahon, B.T.; Bishop, M.L.; Rumrill, S.P.; Sheppard-Jones, K. Comparing the workplace discrimination experiences of older and younger workers with multiple sclerosis under the americans with disabilities act: Amendments act. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 2020, 51, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S. , Cagliostro, E., Leck, J., Shen, W., & Stinson, J. Disability disclosure and workplace accommodations among youth with disabilities. Disability & Rehabilitation 2019, 41, 1914–1924. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=136782357&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Lindsay, S. , Cagliostro, E., Leck, J., Shen, W., & Stinson, J. Employers’ perspectives of including young people with disabilities in the workforce, disability disclosure and providing accommodations. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2019, 50, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madera, J.M.; Taylor, D.C.; Barber, N.A. Customer service evaluations of employees with disabilities: The roles of perceived competence and service failure. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 2020, 61, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangerini, I.; Bertilsson, M.; de Rijk, A.; Hensing, G. Gender differences in managers’ attitudes towards employees with depression: A cross-sectional study in sweden. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–15. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=147108357&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBee-Black, K.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Exploring clothing as a barrier to workplace participation faced by people living with disabilities. Societies 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnall, M.C.; Crudden, A. Predictors of employer attitudes toward blind employees, revisited. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2018, 48, 221–231. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=128962798&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- McDonnall, M.C.; Tatch, A. Educational attainment and employment for individuals with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 2021, 115, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight-Lizotte, M. Work-related communication barriers for individuals with autism: A pilot qualitative study. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling 2018, 24, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.M.; Henry, S.; Linthicum, M. Employability in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Job candidate’s diagnostic disclosure and ASD characteristics and employer’s ASD knowledge and social desirability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 2021, 27, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.; Robinson, S.; Fisher, K.R. Barriers to finding and maintaining open employment for people with intellectual disability in australia. Social Policy & Administration 2019, 54, 88–101. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=140415521&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Moloney, M.E. , Brown, R.L., Ciciurkaite, G., & Foley, S.M. “Going the extra mile”: Disclosure, accommodation, and stigma management among working women with disabilities. Deviant Behavior 2019, 40, 942–956. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=137412060&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Moreland, C.J.; Meeks, L.M.; Nahid, M.; Panzer, K.; Fancher, T.L. Exploring accommodations along the education to employment pathway for deaf and hard of hearing healthcare professionals. BMC Medical Education 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters MD, J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagib, W.; Wilton, R. Gender matters in career exploration and job-seeking among adults with autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from an online community. Disability & Rehabilitation 2020, 42, 2530–2541. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=145497322&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Narenthiran, O.P.; Torero, J.; Woodrow, M. Inclusive design of workspaces: Mixed methods approach to understanding users. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2022). Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Data and statistics. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd.

- Ne’eman, A. , & Maestas, N. (2022). How has COVID-19 impacted disability employment? National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30640.

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2016). Policy on ableism and discrimination based on disability (2). https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/book/export/html/18436.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2022). Disability, work and inclusion: Mainstreaming in all policies and practices. OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Østerud, E. Mental health and workplace disclosure: Stigma, strategies, and career impacts. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 2022, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østerud, K.L. A balancing act: The employer perspective on disability disclosure in hiring. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2022, 1–14. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=156829913&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Östlund, G.; Johansson, G. Remaining in workforce - employment barriers for people with disabilities in a swedish context. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 2018, 20, 18–25. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=135098440&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194 Östlund. [CrossRef]

- Ostrow, L. , Smith, C., Penney, D., & Shumway, M. “It suits my needs”: Self-employed individuals with psychiatric disabilities and small businesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2019, 42, 121–131. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=136742542&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [PubMed]

- Phillips, K.G.; Houtenville, A.J.; O’Neill, J.; Katz, E. The effectiveness of employer practices to recruit, hire, and retain employees with disabilities: Supervisor perspectives. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2019, 51, 339–353. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=139683351&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Plexico, L.W.; Hamilton, M.; Hawkins, H.; Erath, S. The influence of workplace discrimination and vigilance on job satisfaction with people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders 2019, 62. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=140294818&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Raymaker, D.M. , Sharer, M., Maslak, J., Powers, L.E., McDonald, K.E., Kapp, S.K., Moura, I., Wallington, A. “, & Nicolaidis, C. “[I] don’t wanna just be like a cog in the machine”: Narratives of autism and skilled employment. Autism: The International Journal of Research & Practice 2022, 1. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=156068456&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Robertson, P.J. Building capabilities in disabled job seekers: A qualitative study of the remploy work choices programme in scotland. Social Work and Society 2018, 16. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85059471643&partnerID=40&md5=86b5bd1e27d554688ee3008b2ebfcbe0.

- Romualdez, A.M. , Heasman, B., Walker, Z., Davies, J., & Remington, A. “People might understand me better”: Diagnostic disclosure experiences of autistic individuals in the workplace. Autism in Adulthood 2021, 3, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romualdez, A.M.; Walker, Z.; Remington, A. Autistic adults’ experiences of diagnostic disclosure in the workplace: Decision-making and factors associated with outcomes. Autism and Developmental Language Impairments 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumrill, P.D.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Leslie, M.; McMahon, B.T.; Bishop, M.; Rios, Y.C. Workplace discrimination allegations and outcomes involving caucasian americans, african americans, and hispanic/latinx americans with multiple sclerosis: A causal comparative analysis. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2019, 56, 93–106. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=156136093&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Rustad, M.; Kassah, K.A. Learning disability and work inclusion: On the experiences, aspirations and empowerment of sheltered employment workers in norway. Disability & Society 2020, 36, 399–419. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=150086246&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Santuzzi, A.M.; Keating, R.T.; Martinez, J.J.; Finkelstein, L.M.; Rupp, D.E.; Strah, N. Identity management strategies for workers with concealable disabilities: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Social Issues 2019, 75, 847–880. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=138772637&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Santuzzi, A. , Martinez, J.J., & Keating, R.T. The benefits of inclusion for disability measurement in the workplace. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 2022, 41, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schur, L.A. , Ameri, M., & Kruse, D. Telework after COVID: A ’silver lining’ for workers with disabilities? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2020, 30, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutz, M.A.; Awsumb, J.M.; Carter, E.W.; McMillan, E.D. Parent perspectives on pre-employment transition services for youth with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 1487a2021, 1. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=148766902&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.E.; Corey, J.; Duff, J.; Herer, A.; Rogers, E.S. Anticipating the outcomes: How young adults with developmental disabilities and co-occurring mental health conditions make decisions about disclosure of their mental health conditions at work. Disability & Rehabilitation 2022, 1–11. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=155187593&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Sevak, P.; O’Neill, J.; Houtenville, A.; Brucker, D. State and local determinants of employment outcomes among individuals with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 2018, 29, 119–128. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=131206722&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri-Petersen, D.; Krogh, C. Disability disqualifies: A vignette experiment on danish employers’ intentions to hire applicants with physical disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 2020, 22, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, A.; Mendez, M.A.; Bell, E. Understanding the employment experiences of americans who are legally blind. Journal of Rehabilitation 2019, 85, 44–52. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=ccm&AN=135314654&site=ehost-live&custid=s5672194.

- Sprong, M.E. , Mikolajczyk, E., Buono, F.D., Iwanaga, K., & Cerrito, B. The role of disability in the hiring process: Does knowledge of the americans with disabilities act matter? Journal of Rehabilitation 2020, 85, 42–49. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85082510703&partnerID=40&md5=5844c584c3dca230becf149640fe8f14.

- Stack, E. , & McDonald, K.E. Nothing about us without us: Does action research in developmental disabilities research measure up? Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2014, 11, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. (2017). A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/.

- Stokar, H. Reasonable accommodation for workers who are deaf: Differences in ADA knowledge between supervisors and advocates. Journal of the American Deafness & Rehabilitation Association (JADARA) 2020, 53, 38–59. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=142751144&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Stokar, H.; Orwat, J. Hearing managers of deaf workers: A phenomenological investigation in the restaurant industry. American Annals of the Deaf 2018, 163, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, V.; O’Neill, J.; Houtenville, A.J.; Phillips, K.G.; Keirns, T.; Smith, A.; Katz, E.E. Striving to work and overcoming barriers: Employment strategies and successes of people with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2018, 48, 93–109. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=128263173&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Svinndal, E.V.; Jensen, C.; Rise, M.B. Employees with hearing impairment. A qualitative study exploring managers’ experiences. Disability & Rehabilitation 2020, 42, 1855–1862. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=144473892&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Teindl, K.; Thompson-Hodgetts, S.; Rashid, M.; Nicholas, D.B. Does visibility of disability influence employment opportunities and outcomes? A thematic analysis of multi-stakeholder perspectives. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2018, 49, 367–377. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=133954141&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Ford, H.L.; Stroud, A.; Madill, A. Managing the (in)visibility of chronic illness at work: Dialogism, parody, and reported speech. Qualitative Health Research 2019, 29, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C. , Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K.K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D.,... & Straus, S.E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2017, January 20). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html.

- Wang, E.Q.; Radjenovic, M.; Castrillón, M.A.; Feng GH, Y.; Murrell, D.F. The effect of autoimmune blistering diseases on work productivity. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2018, 32, 1959–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westoby, P.; Shevellar, L. The possibility of cooperatives: A vital contributor in creating meaningful work for people with disabilities. Disability & Society 2019, 34, 1613–1636. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=141601073&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

- Whelpley, C.E.; Banks, G.C.; Bochantin, J.E.; Sandoval, R. Tensions on the spectrum: An inductive investigation of employee and manager experiences of autism. Journal of Business & Psychology 2020, 36, 283–297. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=a9h&AN=149048963&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5672194.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).