1. Introduction

The United Nations (UN) 2030 Sustainable Development Goal 8 states “inclusive and sustainable growth, employment and decent work for all” [

1]. To enable this, the world needs to expedite the provision of full and productive employment for all, given that unemployment remains relatively high in many countries, and women, young people, and Persons with Disabilities (PwD) typically bear the brunt of the risks posed by the labour market [

2]. According to a World Health Organisation (WHO) [

3] report, 15% of the world’s population, 15 years and older, live with a disability. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) Article 1 defines a person with a disability as “Someone who has long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” [

4]. This definition was adhered to in the selection of the sample population for this research. This study also subscribed to the International Labour Offices’ (ILO) definition of employment which refers to persons of working age who, in a short reference period, were engaged in any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit [

5]. The WHO [

3] report noted that PwD are more likely to be unemployed and generally earn a lesser income when they are employed. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [

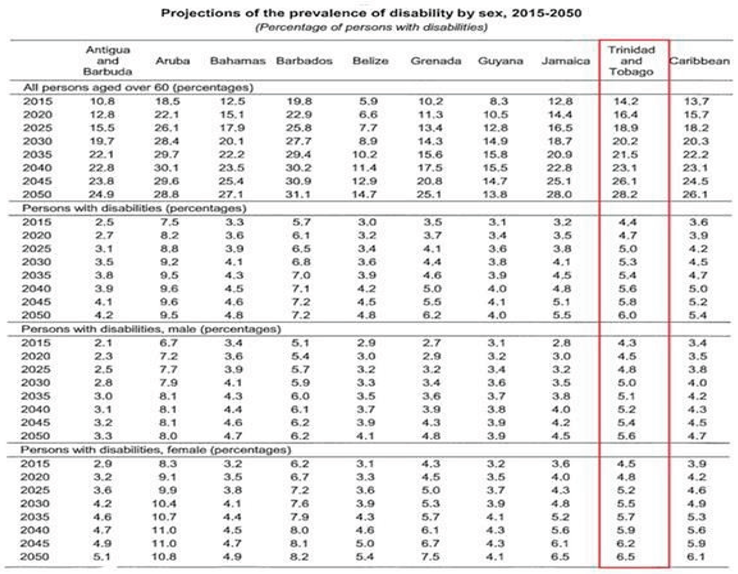

6] indicated that the average employment rate for PwD was 44% compared to 75% for persons without disabilities (PWoD). The disparity in the rate of economic activity between PwD and PWoD in many Caribbean countries, is highlighted in

Table 1 as between 20% and 40% respectively which suggests that PwD were approximately half as likely as those without disabilities to be employed [

7].

Moreover, the employment rate varies significantly for people with different disabilities. For example, in the Caribbean, approximately 54% of persons aged 15-59 with difficulty seeing were economically active, compared to 43% of persons with difficulty hearing, and 67% of persons without a disability [

7]. Employment rates also differ by gender. While there are lower rates overall for PwD when compared with PWoD [

3] women with disabilities appear to face greater employment barriers. The ILO [

8] highlighted that in 2018, the employment rate of women with disabilities (aged 20 to 64) was 47.8% compared to 54.3% employment rate of men with disabilities of the same age.

In T&T, the 2011 Population and Housing Census revealed that 4% of the population has a disability. The 2011 Census data also indicated an approximately equal number of female and male PwD. Females accounted for approximately 26,234 (50.2%) and males 26,010 (49.8%) of the population of PwD. According to Jones and Serieux-Lubin [

7], the number of PwD across the Caribbean, inclusive of T&T, is projected to grow across genders until 2050 as illustrated in

Table 1. Due to the projected growth in numbers of PwD, it is necessary to treat with the barriers which hinder their participation in economic activity. Specific barriers to employment for PwD such as inadequate policies and standards or lack of enforcement of existing ones, limited access to transportation services and negative attitudes or stereotypes held by employers and society at large, have been identified [

3]. ILO [

8] also identified inaccessibility and non-inclusivity in education as a barrier towards employment.

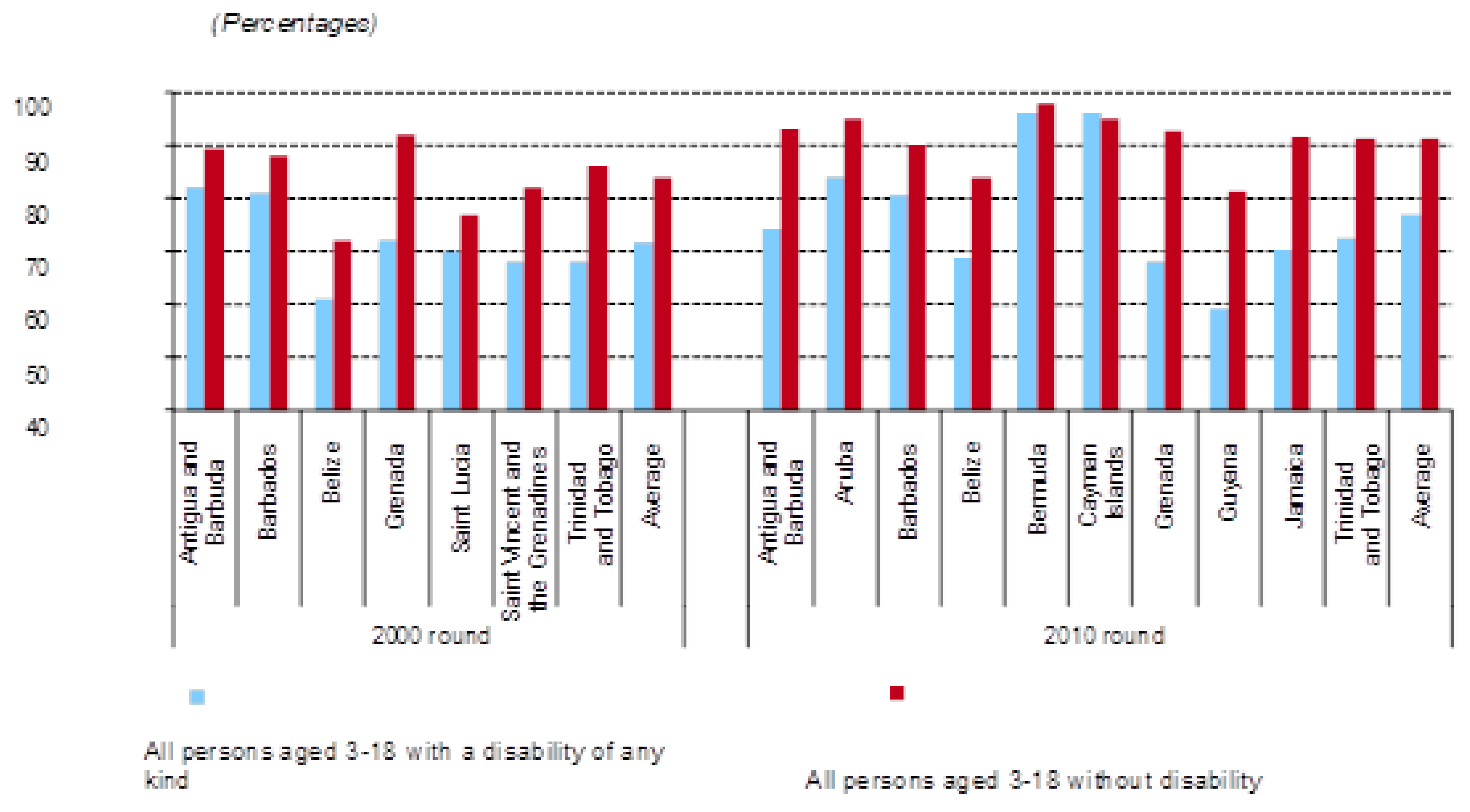

Despite the improvements in educational opportunities for children with disabilities (CwD) in the Caribbean, significant inequalities between the rate of school attendance for children with and without disabilities, as well as the educational attainment of the former have been identified as contributing to lower employment among PwD relative to those without [

7]. Jones and Serieux-Lubin [

7] highlighted that many CwD, particularly those with more severe disabilities, are unable to attend mainstream schools due to physical inaccessibility or the schools’ inability to meet their educational needs. Disparities between the school attendance rates between CwD and children without disabilities (CWoD) between the ages of 3-18 in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2000 and 2010 are highlighted in

Figure 1 below.

T&T has one of the largest disparities in the completion of secondary education between working-age adults with and without disabilities in the Caribbean, Longpre [

9] as cited in Persons [

10]. In 2010, 50% of PwD had a secondary school education while 80% of PWoD had completed secondary school. The disparity may be attributed to the limited inclusion of PwD in the mainstream school system. Persons [

10] highlighted that most CwD attend special schools, that are unable to provide quality education. This resulted given that mainstream schools are not mandated to accept students with disabilities due to the current lack of legislation. The causes a dearth in qualifications required to access employment opportunities. Considering the above, there is a lack of current data on the employment rates of PwD in T&T and their lived work experiences of seeking employment. Additionally, there is a lack of research exploring the employment experiences of PwD from multiple perspectives including employers. Thus, the study sought to 1. determine the prevalence of unemployment among PwD in T&T and 2. explore the barriers to employment among PwD in T&T. It highlights these barriers through the perspectives of the PwD themselves, representatives from advocacy organizations for PwD (AOPwD), Government representatives, and employers. The importance of this study is fundamental to adding to the body of knowledge on the topic within the T&T context, as well as contributing to the equity and inclusiveness of PwD in T&T.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A concurrent triangulation mixed method design was selected to capitalize on the differing strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches and to validate the findings. The quantitative and qualitative methods were implemented during the same timeframe and with equal emphasis. Therefore, there was a concurrent, but separate, collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data which allowed for increased efficiency. The data was then integrated during the analysis phase.

2.2. Setting

This study was conducted in T&T, during the COVID-19 period in 2020.

2.3. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval and all permissions were secured from the relevant organisations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Participation in the research was voluntary, and participants were entitled to withdraw at any given time, even after giving informed consent. Anonymity was maintained specifically in the case of employers who participated in the survey. The information collected did not contain any identifiable information, and as a result, the risk of being able to attribute data to any individual was extremely low or non-existent. Additionally, confidentiality was also preserved via the maintenance of the protection of participants’ raw data from those outside the research team.

2.4. Sampling Strategies

2.4.1. PwD

The sample included PwD > 18 years of age who were unemployed and actively looking for work, or those who were employed. Purposive sampling was utilised to select PwD, it involves identifying and selecting individuals or groups of individuals that are especially knowledgeable about or have experienced the phenomenon of interest [

11]. The study also utilized snowball sampling in the selection of PwD; this method is applied when it is difficult to access subjects with the target characteristics [

12]. Therefore, PwD assisted in the recruitment of research participants among their acquaintances. The final sample consisted of 18 women and 13 men, a total of 31 PwD. Types of disabilities represented included Cerebral Palsy, Persons with Visual Impairment, as well as the Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

2.4.2. Key Informants

The sample specifically included executive members of AOPwD that provide services/support for PwD of employable age; including, The National Centre for PwD and Goodwill Industries of T&T and senior government representatives involved in the strategic management of specific programmes within their ministries. The latter included the Ministry of Social Development and Family Services and the Ministry of Labour. They were all purposely selected for the research because they possessed specific knowledge and information on the PwD community. Seven representatives from the AOPwD, whilst four representatives from relevant government ministries were selected.

2.4.3. Employers

The sample specifically included businesses from the Trinidad and Tobago Chamber of commerce (TT Chamber). The selected respondents were the individuals responsible for hiring and retaining persons in the organization. This was to ensure the credibility of information presented on the hiring tendencies of the organisation towards PwD. Multi-stage sampling was utilized to select employers; The sampling frame was taken from the TT Chamber database. To reduce the sample population to a feasible sample size, a three-step reduction of the sample population was undertaken, using a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error at each stage. Firstly, a stratified random sampling method was utilised to divide the sampling frame (i.e., companies) into strata, allowing companies from the different strata (i.e., sectors, geographic regions) to have an equal chance of being selected. A final sample size between the range of 100-120 was targeted. Secondly, a simple random sampling method was utilized for the random selection of actual businesses to participate in the research. This resulted in the selection of 116 businesses. Thirdly, respondents from 75 of the selected businesses agreed to participate in the survey. One respondent from each business that agreed to participate was purposively selected.

2.5. Materials-Data collection

The primary source of data collection included in-person and telephone interviews, and the use of questionnaires. Additionally, secondary data was accumulated from government agencies and consisted of reports and statistics.

2.5.1. Survey Instrument

Due to the prevailing COVID-19 scenario and the restrictions that were placed on businesses at the time, it was agreed by both the researcher and business owners that an online questionnaire would be more apt and convenient. It was also determined that this approach would facilitate a wider geographical reach. The structure of the questionnaire content was aligned with the research objectives. The questionnaire topics comprised of the following: recruitment of PwD, accommodations in the workplace for PwD, retention of PwD, and barriers that impede the employment of PwD. The instrument comprised 31 questions, and it took approximately 15 min to complete. A pilot study was conducted on the employer survey during the design phase. The results of the pilot allowed for adjustments to the survey instrument [

13] Prior to the questionnaire distribution, a letter of consent was emailed to each prospective respondent. Follow-up telephone calls to answer any queries were also made. Employers confirming their interest in participating via written consent, subsequently received an email message with a URL address for the web- based questionnaire.

2.5.2. Interviews

At the interview, an informed consent letter was read to the participants and assurances of their rights to privacy and confidentiality were emphasized. They were then required to sign the form if they were still interested in being interviewed. The participants were allowed to stop the interview at any time and/or retract their data. The interviews were semi-structured. This method allowed the researcher to collect open-ended data, and explore the participants’ thoughts, feelings, and beliefs about the topic [

14]. The interviews were conducted between the period May to June 2020. The time of the day was primarily at the convenience of the interviewee. Approximately, four interviews were completed and transcribed daily, lasting between 45 min to one hour.

The participant decided to either have the interview at their home, another location or via the telephone. A total of 11 PwD were interviewed at an AOPwD, four were interviewed at home, whilst 16 were interviewed via the telephone. The varying disabilities in the study required the utilization of different interview approaches for the optimal participation of PwD. For instance, in-person interviews were desired by Deaf and Hard of Hearing groups. Telephone interviews were conducted mostly for visually impaired participants, as well as persons with physical disabilities.

2.6. Data Analysis

The secondary data were organized in Microsoft Excel and integrated into the analysis phase to provide a contextual framework. Regarding the primary data, the results of the quantitative survey and the qualitative interviews were mixed in the analysis stage of the study to allow for the drawing of valid inferences reflecting a picture of the two data strands, such as by relating or combining the findings [

15]. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics version 26) was used to facilitate the analysis of the data from the questionnaires. Tests completed included descriptive statistics; inclusive of mean, median, mode, crosstabulations, and correlations. The data from the interviews, however, were coded and categorized into specific themes based on a reflexive thematic approach as advocated by Braun and Clarke [

16].

3. Results

The results explored the themes from the analysis of the interview notes, highlighting paraphrased participant quotes, and results generated from the survey.

3.1. Prevalence of Unemployment Among PwD

The survey data showed that most employers did not have a PwD employed at their organisation (i.e., 64%). Interview data supported this survey finding, highlighting that the majority of PwD remained unemployed or acquired employment after a lengthy period of searching (an average of eight [

8] years or more). A female PwD with Spastic Diplegia possessing tertiary education qualifications sent out numerous applications and had not obtained any responses. Her situation was intensified given her single parent status. Stemming from this, she started her own business to be self-sufficient. The following illustrates her experience:

I have sought gainful employment for the better part of twenty-two years, and all you hear are that you are overqualified for positions or there are no facilities to accommodate me. This is the most common song and dance that the disabled population go through.

The findings also revealed that PwD occupants of the AOPwD held only primary school-level qualifications and were mostly employed at the school. Most of these PwD were classified as possessing the ability to acquire academic skills at a rate below that of the average student (intellectual disabilities), which may have led to a lack of movement beyond primary school qualifications. This contrasted with PwD who were not occupants of these schools, possessed a mix of secondary and tertiary education and were engaged in mainstream employment (i.e., employment not associated with the AOPwD).

The role of placement organizations was also highlighted. They included the On-The- Job-Training programme (OJT) which focuses on skills acquisition and experience within organizations for participants and The National Employment Service (NES) that equips job seekers with the necessary guidance to access the job market, whilst connecting employers with job seekers. For the period 2019, the NES indicated that 10 PwD applied for placement in various organisations roles, and those 10 PwD were placed. This can be compared with data for PWoD, where 5,606 applied for employment for that period, and the number employed was 1035. While the OJT program highlighted a similar minimal number of placements for PwD, nine (9).

Differences were also identified by the specific disability type as indicated by the Deaf and Hearing groups. Deaf PwD, in this study, noted that persons who are hard of hearing possess the ability to communicate more effectively in workplaces, without the need of an interpreter, thus they were advantageously positioned for securing employment in comparison to them (i.e., Deaf PwD). These sentiments can be seen in the participant statements below:

A lot of effort needs to be put in to ensure equity in the labour market. I want to do a short course, who is going to interpret for me, what is the support for me? We are at a disadvantage to Hard of Hearing, because of the communication barrier, we need to pay a private interpreter at times for assistance.

The Hard of Hearing shared similar sentiments:

Hard of Hearing persons may be more responsive in the workplace than Deaf people, because Hard of Hearing can do lip reading, can talk, and write and understand their resume application. Yes, it’s difficult, Deaf persons cannot hear, but they can do lip reading and sign language and write but do need an interpreter.

Similarly, for those PwD with intellectual disabilities such as Down Syndrome, the findings revealed that most of these persons were absorbed within the AOPwD and received vocational training. These PwD were perceived as being negatively positioned to access mainstream employment. The data suggested that employers were more inclined to hire PwD with a disability which they considered less demanding and more manageable in the workplace. One employer stated that “if the person is mentally challenged, it won’t work at this time. Physical disability will not affect hiring”. The employers generally indicated that they would be unwilling to hire PwD based on the following characteristics: nature of the disability (35%), severity of the disability (21%), and the need for additional guidance (23%). An executive from an AOPwD indicated that “by placing the label special” on PwD with intellectual disabilities they are at a disadvantage.

3.2. Barriers to Employing PwD

3.2.1. Lack of Legislation

Participants indicated the need for legislation to accompany the current National Policy for PwD (2019) to encourage the effective implementation of the plans espoused within that policy. This sentiment can be seen in the quote from an AOPwD representative below:

Currently, there is the Equal Opportunity Act and the Tribunal. However, there are certain deficiencies in the Act. For example, the definition of disability in the Act does not cover all persons with disabilities. For example, a person with Down Syndrome, which is a person with an intellectual disability, is not afforded protection because they do not fall within the definition of a person with a disability in the Act itself. What we need now is actual legislation that PwD can use now to enforce their rights, to ensure that public and private bodies in T&T do more to promote inclusion or can at least be held accountable for discrimination. This is what is needed to accelerate that shift to a more inclusive and equitable society. When the legislation is there, this will also break down the attitudinal barriers that exist.

3.2.2. The Inequitable Education Playing Field

Lack of equity in the education system was also underscored by PwD as well as representatives from the AOPwD as another barrier to accessing employment. Interviewees identified the lack of inclusiveness in the education system, as a salient issue reflected in the limited enrolment of PwD in mainstream education. This was highlighted by an AOPwD executive who indicated that the lack of inclusiveness was personified “by placing them [PwD] in segregation, from being able to mix and mingle with other human beings”.

Research participants also agreed that mainstream schools are ill-equipped to successfully cater to the needs of PwD. They noted that an integral component of the education system was the education and training of both teachers and principals to ensure full cognizance of PwD needs. In this regard, one AOPwD Representative explained that:

The education system is an uneven playfield; training does not equip teachers for specialization for certain disabilities. Children in the special schools are not afforded the props [tools] that they need to succeed as kids in the regular [mainstream schools] have. Support systems are not in place in special schools, occupational therapists, counsellors etc. Experiences of American and Canadian children are not the same for children in T&T.

PwD also noted that in some instances, the mainstream curriculum was not aligned with their employment needs. A PwD with visual impairment stated that “they give you training that they think is best for you”. This highlighted the incompatibility between the training received and the training required for the labour market. Overall, participants articulated the elusiveness of equity in the education system and the continued adverse effect on PwD’ ability to obtain the necessary qualifications to access commensurate employment. An advocate for PwD summarized the challenges as follows:

There is no fair and equal access. PwD start at a disadvantage, the lack of education and training cannot meet the labour market. Mainstream schools are unable to effectively train PwD. Principals are confused on how to deal and cater to them at times.

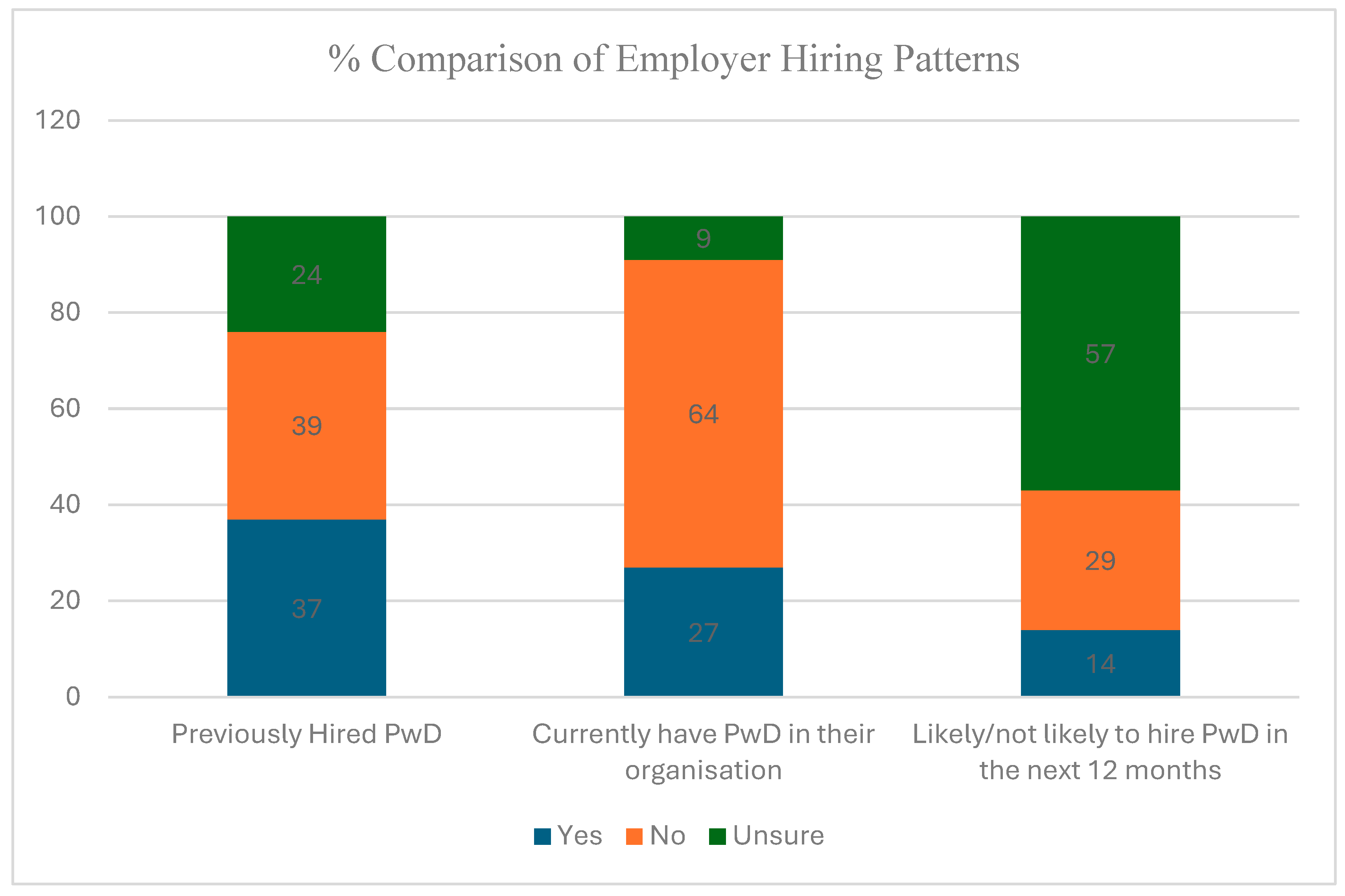

3.2.3. Employer Perceptions on Hiring PwD

The findings revealed that employers’ prejudices about the competence of PwD in the workplace centred around the view that they were not suited or could not work. They believed that work demands were incompatible with the person’s disability, and this was reflected in the survey data which showed that their main concern with hiring PwD was the nature of the work to be performed (69%). One employer noted that “the only thing we will be concerned with is how/if the disability affects the completion of the tasks”. This perception may have affected employers’ hiring patterns towards PwD as seen in

Figure 2.

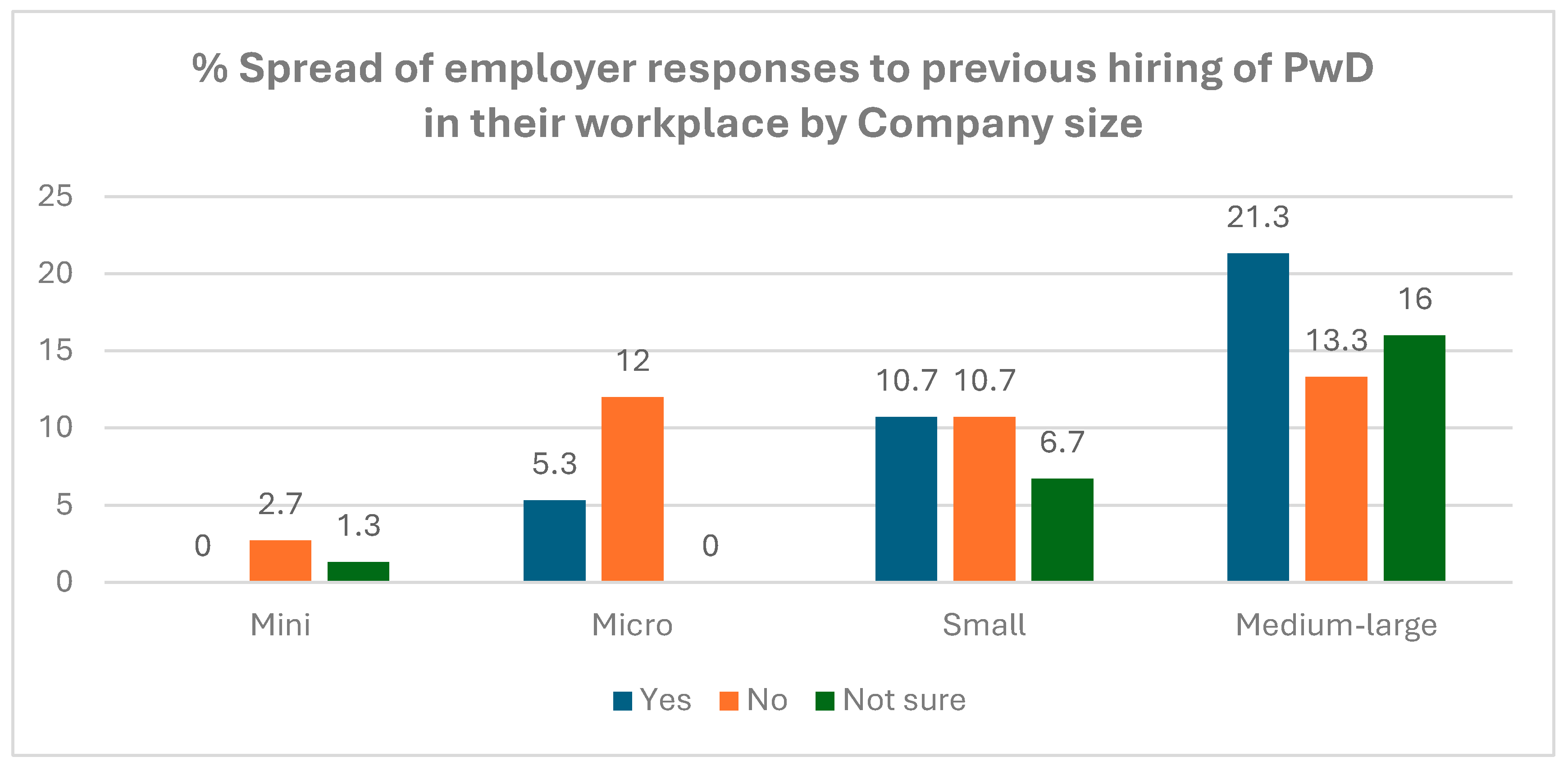

Figure 3 presents the spread of the hiring patterns by business size. The results highlighted that medium -large firms possessed relatively more experience in hiring PwD. Whilst

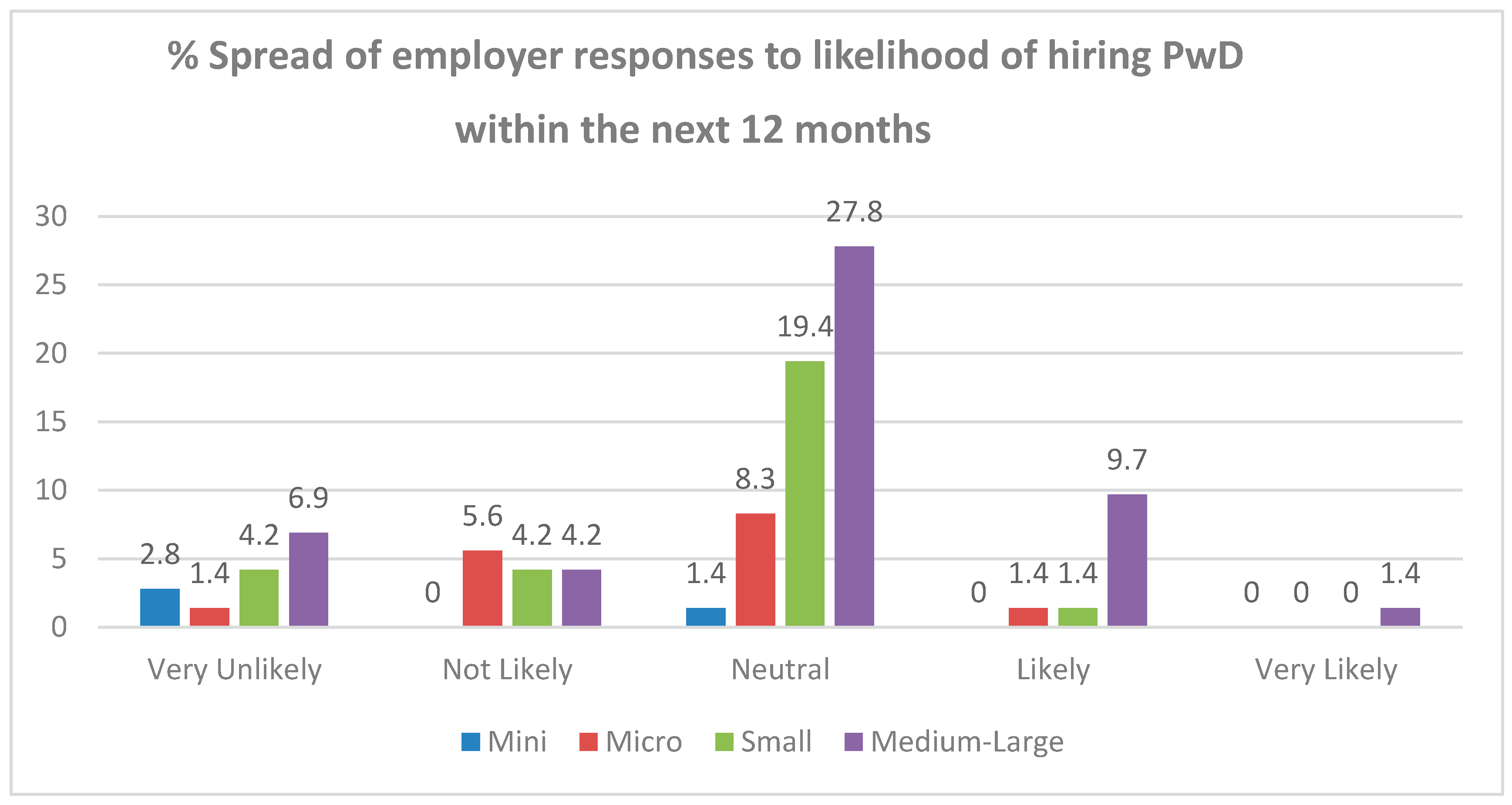

Figure 4 also presents employer likelihood of hiring PwD within the next 12 months.

3.2.4. Lack of Appropriate Workplace Accommodation

The perceived cost of accommodating PwD in the workplace was identified as a top area of concern by employers (i.e., 22%). 69% of employers had not implemented any form of workplace accommodations within their organisations. These statistics were supported by the PwD interviews who explained that employment inaccessibility included the lack of appropriate accommodation. The lack of assistive tools and technologies also negatively impacted on their ability to function effectively. A PwD with visual impairment noted that:

With proper technology such as access to screen magnifiers, or text-to-speech, such as ZoomText, we can function effectively in the workplace. There is a need for appropriate training for managers and employees to work with the blind. The blind person can perform better with the appropriate training. We can work well in organisations if people are willing to make changes to their environment to employ you.

The issue of accommodation was also re-emphasized by a government representative, who stated:

We recognize difficulties in both private and public sectors. There is [an] unwillingness to employ certain types of disabilities. It’s easier to place the wheelchair-bound, not like the blind. Employers don’t understand how to relate to them, and how the staff would relate to them. Also, before we get to the placement, we need to get one of the professionals of the AOPwD to visit the work site, and that is where we have challenges [the representative noted that this is due to a lack of partnerships between the ministry and these institutions].

3.2.5. Tokenism

Throughout their employment search, PwD identified occasions where they would have received advice from PWoD which was counterproductive to employment acquisition. Additionally, those who were previously employed, stated that there were instances where they were treated differently than PWoD as an act of tokenism. For example, in the quote below, a female PwD indicated that in one instance when she was employed, her employer used her disability as leverage in marketing the organisation. She subsequently left.

Wanting to elevate my career, I applied for a position I thought would fit my then goals. Unfortunately, the entire work scope and interview were misleading in this private business, and I saw it as me being pitied for them to gain business from stakeholders. I left. It was a terrible two-year job search.

3.2.6. Feelings of Apathy

Self-restraining attitudes were also revealed among some of the PwD currently working at the AOPwD. The majority have been working at the institution for more than a decade. Some of these individuals started at the institution with primary-level qualifications and remained at the institution without furthering their formal education. Their choice to stay may have been because of the attitude of some of the managers of these institutions as one executive stated that the PwD of working age were “her children”. A PwD detailed why other PwD chose to work at the AOPwD, for little or no pay:

I would tell you something that is not widely known, but we are not only marginalised, we are marginalised by those who say they are equipped and are supposed to be helping us. There are people who left the institution and went back to assist, and the staff [principal] knows the only reason they are assisting is because they want employment, but they cannot find employment, and they [principal] refuse to pay them and these individuals’ mindset is I’m trying to give back and be appreciated, they’re trying to find a way to make themselves useful. They think of the institution as their home, their family.

Additionally, a PwD highlighted that he had been acclimatized to rely on the disability grant from school as the following narrative shows:

The principals at these special institutions are guilty of the very same thing that the normal society is guilty of. A principal told me [he was a teacher at the time], the only thing he is able to do and willing to do, is teaching them [PwD] how to sign their name, so they could go home and get the disability check. If someone came to you, and told you that, what would you think?

3.2.7. Lack of Familial support

Stakeholders noted that family involvement in the development of CwD, may contribute to positive outcomes. Lack of familial support was identified as negatively impacting on the PwD’ well-being and ensuing search for employment. An AOPwD representative highlighted the parent’s role, and significantly, how parents perceive their child’s disability. “Parents are a child’s first advocate, but they are not willing to bring their child into the open, they don’t want them [child with the disability] to be laughed at”.

One PwD also stated that:

Most families do not even think that their disabled family members have a right to a love life far less all that comes with that, because most of us are seen as useless to the outside world. That’s why a large portion of us are sexually abused by family members or people we know and trust. Especially when most of these people don’t face the law because it is covered up by family members or the disabled person is blamed for the action. This causes a feeling of hopelessness among the female population of the disabled.

4. Discussion

The results identified institutional, attitudinal, personal, social, and familial factors affecting PwD’ participation in the labour market. The meaning and relevance of the findings will be explored, how they fit with the existing evidence, and the new insights generated.

4.1. Prevalence of Unemployment Among PwD

Most employers surveyed did not have a PwD employed at their organizations, and they were indifferent to hiring a PwD in the forthcoming year. The majority of PwD also noted that they remained unemployed or only acquired employment after searching for an extensive period. These findings aligned with previous research which highlighted the prevalence of PwD unemployment across various countries, underlining the global concern [

17,

23].

The results of the study contributed to the literature by highlighting key unexplored areas, specifically in Caribbean countries. The data suggested that larger businesses were more likely to hire PwD than small-micro and mini- micro businesses, given their higher capacity to accommodate PwD. Dissimilarities were also observed in the study, regarding mainstream employment access for PwD in AOPwD in contrast to those who were not clients of those institutions. It was revealed that PwD who were occupants of the AOPwD held only primary school level qualifications. In this regard, these PwD were predisposed to being occupants of the AOPwD and were not expected to obtain employment. The literature highlighted the need for higher educational attainment, beyond primary school, to enable access to the labour market [

24].

Additionally, the findings of the study revealed the role of placement institutions as a liaison between job seekers and employers. This synchronized with their mandate in contributing to individuals’ acquisition of practical skills and experience. These findings corresponded with the previous researchers [

18,

25,

26] who highlighted the importance of internships and the provision of adequate mentorship for work experience and placement of trainees. It should be noted that despite the placement of PwD, the significantly larger number of applications from PWoD emphasizes PwD apathy, given PwD acknowledgement of the barriers to employment.

4.1.1. Disparities in Employment by Disability Type

The findings also added to the literature by sharing the experiences of two populations within the Deaf community; the Deaf and Hard of Hearing whose differing needs, have often been overlooked. Most of the literature has merged the work experiences of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing together but the current findings showed that the Hard of Hearing were perceived by Deaf as being more advantageously positioned to access and acquire employment because the former possessed the ability to communicate more effectively in the workplace (i.e., without the need of an interpreter). Consequently, there is an opportunity to further examine the work experiences of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing separately to capture their unique experiences.

Similar disparities were found between persons with intellectual disabilities (such as Down Syndrome) and those with physical difficulties. The findings showed that PwD with intellectual disabilities were predominantly absorbed within institutions for PwD, instead of accessing mainstream employment which was consistent with previous studies which also showed the unfavorable positioning of persons with intellectual disabilities relative to other PwD [

7,

27].

4.2. Barriers to Employing PwD

4.2.1. Institutional and Systemic Barriers

Key informants believed that accompanying legislation is needed to support the National Policy for PwD in T&T (2019). Legislation is also necessary to facilitate compliance with International Standards, specifically the UNCRPD. This will aid in implementing the policy’s plans and is critical in facilitating employment opportunities for PwD. These results synchronized with the evidence from the literature which showed the need to implement legislation for policies that seek to protect the legal, social, political, and economic rights of the PwD [

3,

10,

28,

29,

30].

This current study also revealed that while most of the PwD completed primary education, participation in mainstream education may have contributed to acquiring higher-education qualifications and subsequent employment opportunities Therefore, involvement in mainstream education contributed to levelling the playing field for PwD and reduced the discrepancy between them and PWoD in the labour market. This finding coincided with Banks and Polack [

31] who noted positive economic benefits of inclusive education on PwD. However, AOPwD representatives in this study noted the elusiveness of PwD’ attendance in mainstream schools. This was corroborated in the literature which noted that most CwD attend special schools because accepting students with disabilities into mainstream schools was not mandatory [

9,

10].

The current study’s findings also revealed that mainstream schools were ill-equipped to successfully meet the needs of PwD. This aligned with Longpre [

9], who noted the lack of sufficient support for students with special needs and those who had difficulty learning in T&T. Success of PwD within the mainstream education system was linked to the education and training of both teachers and principals on PwD’ needs. The need for teachers to be suitably trained was identified by Johnstone [

32].

4.2.2. Attitudinal Barriers

Employer’s attitudes were concentrated on whether PwD possessed the capacity to fulfil the demands of the work. Most employers had not previously hired a PwD. Additionally, more than half of the employers were ambiguous on whether they would consider hiring a PwD within the following year. These findings support evidence presented in the literature which highlighted their stereotypical views, including the overarching concerns with disability type and its impact on the performance of PwD in the workplace [

7,

17,

18,

21,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Furthermore, employers’ preferences were contingent on the type of disability. This aligned with the literature which noted that a fundamental reason for lower participation rates and underemployment of PwD was related to stereotypes about certain types of disabilities. For instance, PwD with intellectual disabilities were perceived to be disadvantageously positioned from the onset [

36,

38,

39]. Previous findings highlighted that employers were predisposed to hire PwD with a disability which they considered to be less demanding and easier to navigate in the workplace [

36,

38,

39] Additionally, in the current study, at times employers hired PwD as a display of tokenism and in other instances, they were viewed as being incapable of performing specific tasks. These experiences aligned with those presented in the literature [

21,

34]. Finally, previous findings revealed employers’ views concerning the relatively more expensive hire of PwD versus PWoD since the former requires special accommodation [

18,

35,

36,

37]. This was also revealed as a perceived area of concern by employers in this study.

4.2.3. Individual and Social Barriers

The PwD in the study admitted to feelings of apathy regarding their search for employment resulting from the societal discrimination they faced. Deep-rooted feelings of negative self-perception by PwD stymied their motivation towards striving for mainstream employment. This sense of apathy was also noted by other writers on the topic [

20,

21]. The current study’s findings emphasised however the role being employed at AOPwD played in the apathetic PwD’ lives. The work experiences of these PwD were exclusively tied to their involvement with AOPwD, and some participants lacked motivation to seek employment elsewhere. This contrasted with the work experiences of PwD who were not employed at AOPwD and engaged in mainstream employment. This argument is supported by the 5,606 PWoD who applied for work through the NES compared with only 10 PwD.

Additionally, previous writers on the topic underscored the essentiality of familial support in successful PwD employment search outcomes [

40]. The authors noted the benefits of early intervention in the social and cognitive competence development of a child via appropriate parent-child interactions. This could generate the long-term impact of improving access to mainstream employment. In the current study, PwD noted the lack of their parents’ support at the onset of their diagnoses as an impediment towards long-term positive employment outcomes. This study also highlighted the parents’ fear of the loss of the financial grant which was only provided to unemployed PwD. The grant was a source of financial support in the home and parents feared it’s loss if the PwD obtained employment. This was due to the security provided by the grant as opposed to the perceived uncertainty of precarious employment; the latter refers to being hired for a period. This adversely affected some PwD’ motivation to seek employment and reinforced their negative self-images. In the literature, negative stereotypes of PwD’ abilities and competencies held by their families were reinforced and discouraged their learning and development [

21]

5. Conclusions

The study provided evidence of the barriers to the employment of PwD. There is great apprehension among employers regarding hiring PwD and this is exacerbated depending on the type and severity of the disability and the extent of provisions needed to adequately accommodate PwD. The latter was noted in the employment patterns by company size. Key institutional and systemic, attitudinal, and social barriers to PwD accessing employment included lack of legislation, inequitable educational access, employers’ perceptions regarding the competencies of PwD, token practices, feelings of apathy, and lack of familial support.

5.1. Practical and Policy Implications

The study suggests key implementation areas. Legislation is the highest priority given its pivotal role in facilitating the other actions. For example, legislation is needed to ensure that schools are compliant with relevant laws, regulations, and policies governing education for students with disabilities. This can foster changes in the education sector to facilitate inclusion, including training for principals and teachers to deliver effective training to PwD. This is critical given that education is a precursor to employment opportunities. Additionally, legal guidelines and regulations regarding the employment of PwD are needed for employer compliance. Recommendations include the formation of an Employer Resource Centre to facilitate employer awareness of PwD needs, and incentivisation especially for the small and micro businesses to cover PwD accommodation costs. A proposed review of the AOPwD can also be accomplished to measure the effectiveness of these institutions. The above should be accomplished with the implementation of a results-based monitoring and evaluation framework to facilitate continuous measurement of the progress of the proposed recommendations.

Author Contributions

A.F. contributed to the manuscript, collected data, analysed data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. S.G. contributed to the review, editing and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Trinidad and Tobago (protocol code UTTO/280 and 25 October 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the invaluable support provided by Dr. Karen Pierre, Assistant Professor, Health Sciences, University of Trinidad and Tobago. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Samantha Glasgow, Assistant Professor/Discipline Leader (HS&HA Unit), Health Sciences Unit, University of Trinidad and Tobago for the excellent supervision provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOPwD |

Advocacy organizations for PwD |

| CWD |

Children with Disabilities |

| CWoD |

Children without Disabilities |

| ILO |

International Labour Organization |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PwD |

Persons with Disabilities |

| PWoD |

Persons without Disabilities |

| T&T |

Trinidad and Tobago |

| TT chamber |

Trinidad and Tobago Chamber of Commerce |

| UNCRPD |

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- United Nations. Sustainability Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- International Labour Organzation. World Employment and Social Outlook-Trends 2019. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_670542.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- World Health Organisation. World Report on Disability 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- United Nations. Disability and Employment. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/factsheet-on-persons-with-disabilities/disability-and-employment.html (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- International Labour Organization. Employment. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/employment-1 (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers. A synthesis of findings across OECD countries; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2010/11/sickness-disability-and-work-breaking-the-barriers_g1g10adb.html (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Jones, F.; Serieux-Lubin, L. Disability, Human Rights and Public Policy in the Caribbean: A Situation Analysis; United Nations, ECLAC: Santiago, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. An inclusive digital economy for people with disabilities. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@gender/documents/publication/wcms_769852.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Longpre, K. Advocacy for Improved Special Education in Trinidad and Tobago. Master of Community Development, University of Victoria, BC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Persons, H. Persons with Disabilities in Trinidad & Tobago A Situational Analysis. Common Wealth of Learning; Commonwealth of Learning. Available online: https://oasis.col.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8af3b247-4d7d-4a86-9b85-451ef8363b35/content (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Creswell, J.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Naderifar, M.; Goli, H.; Ghaljaie, F. Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education 2017, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, H.; Van Der Walt, C.; Van Rensburg, G. Fundamentals of Research Methodology for Health Care Professionals, 4th ed.; Juta: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L. Semi structured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Journal of Family Medicine and Community Health 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Journal of Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes-Gayle, A. Disability and Inequality: Socioeconomic Imperatives and Public Policy in Jamaica; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Employability of people with disabilities in Suriname. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/---sro- Port-of-Spain/documents/publication/wcms_740355.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Meltzer, A.; Robinson, S.; Fisher, K.R. Barriers to finding and maintaining open employment for people with intellectual disability in Australia. Social Policy & Administration, 2020, 54, 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Naami, A. Disability, gender, and employment relationships in Africa: The case of Ghana. African Journal of Disability 2015, 4, 4–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opoku, M.P.; Mprah, W.K.; Dogbe, J.A.; Moitui, J.N.; Badu, E. Access to employment in Kenya: The voices of persons with disabilities. International Journal on Disability and Human Development. 2017, 16, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, M. Persons with disabilities and employment. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2014001/article/14115-eng.pdf?st (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Wehman, P. Employment for persons with disabilities: Where are we now and where do we need to go? Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2011, 35, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, T.; Boman, E.; Danermark, B.; Kjellberg, A. Employment opportunities for persons with different types of disability. Alter-European Journal of Disability Research. 2015, 9, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayombe, C. Integrated non-formal education and training programs and centre linkages for adult employment in South Africa. Australian Journal of Adult Learning 2017, 57, 106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, W.C.; Swartz, L. What facilitates the entry of persons with disabilities into South African companies? Disability and R ehabilitation Journal 2012, 34, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahami, A.K.; Wittevrongel, K.; Nicholas, D.B.; Zwicker, J.D. Prioritizing barriers and solutions to improve employment for persons with developmental disabilities. Disability and Rehabilita tion. 2019, 42, 2696–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordic Consulting Group. Mainstreaming disability in the new development paradigm Evaluation of Norwegian support to promote the rights of persons with disabilities. Available online: https://african.org/mainstreaming-disability-in-the-new- development-paradigm/ (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Scott, S. I am Able, Situational Analysis of Persons with Disabilities in Jamaica. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/jamaica/reports/i-am-able.

- Wapling, L.; Downie, B. Beyond charity: A donor’s guide to inclusion. Available online: https://disabilityrightsfund.org/wp-content/uploads/DRF-Donors-Guide.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Banks, L.M.; Polack, S. The Economic costs of exclusion and gains of inclusion of people with Dis abilities: Evidence from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Available online: https://www.cbm.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/Costs-of-Exclusion-and-Gains-of-Inclusion-Report.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Johnstone, J.C. Inclusive education policy implementation: Implications for teacher workforce development in Trinidad and Tobago. International Journal of Special Education 2010, 25, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bredgaard, T.; Salado-Rasmussen, J. Attitudes and behaviour of employers to recruiting persons with disabilities. Alter 2020, 15, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Heera, S.; Devi, A. Employers’ perspective towards people with disabilities: A review of the literature. The South East Asian Journal of Management 2016, 10, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtenville, A.; Kalargyrou, V. People with disabilities: employers’ perspectives on recruitment practices, strategies, and challenges in leisure and hospitality. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2012, 53, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, H.S.; Jans, L.H.; Jones, E.C. Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2011, 21, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, M.; Kote, J. Increasing employment of people with disabilities: The role and view as of disability: Training and placement agencies. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 2014, 26, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, P.B.; Oire, S.N.; Fabian, E.S.; Wewiorksi, N.J. Negotiating reasonable workplace accommodations: Perspectives of employers, employees with disabilities, and rehabilitation service providers. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 2012, 37, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, B.; McDonald, K.; Divilbiss, M.; Horin, E.; Velcoff, J.; Donoso, O. Reflections from employers on the disabled workforce: Focus groups with healthcare, hospitality, and retail administrators. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. 2008, 20, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnick, M.J.; Bruder, M.B. Early intervention. Handbook of Intellectual Disabilities—Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice; Matson, J.L., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 717–742. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).