Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Waste biomass deriving from agricultural activities has different destinations depending on the possibility to apply it to specific processes. As the waste biomass is abundant, cheap and generally safe, it can be used for several applications, being biogas production the most relevant from the quantitative point of view. In this study, we have used as substrates for the microbial production, a set of agricultural by-products deriving from the post-harvest treatment of cereals and legumes. Some of the by-products used in the study, and tested without any pre-treatment, were easily metabolized and were highly effective for the growth of microorganisms. Besides allowing growth of the microorganisms, the formulation of the waste agricultural biomass with a reduced set of nutrients routinely used in fermentation, stimulated biosurfactants productions in the range of tenths of grams of the pure products. In particular, the use of mechanically treated corn chaff (“bees wings”) was suitable for the production of rhamnolipids. This study demonstrated that the use of alternative raw materials could be applied to reduce the carbon footprint of industrial productions without compromising the possibility of having suitable processes for the industrial production of high added value molecules.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strains, Culture Media and Culture Conditions

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Acid hydrolysis and HPLC Quantification of Rhamnolipids and Sophorolipids (Glycolipids)

2.2.2. LC-MS Analysis of Rhamnolipids

2.2.3. HPLC Analysis of Surfactin

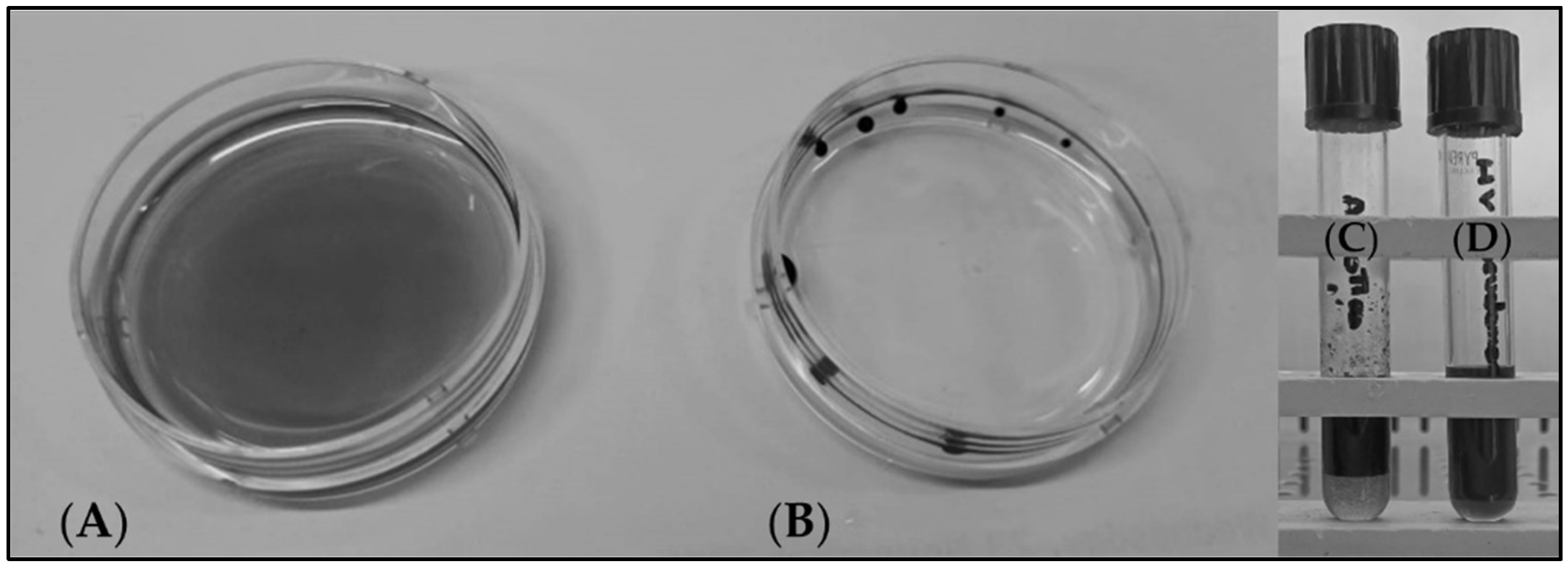

2.3. Oil Displacement Test (ODA)

2.4. Emulsification Index (EI24(%))

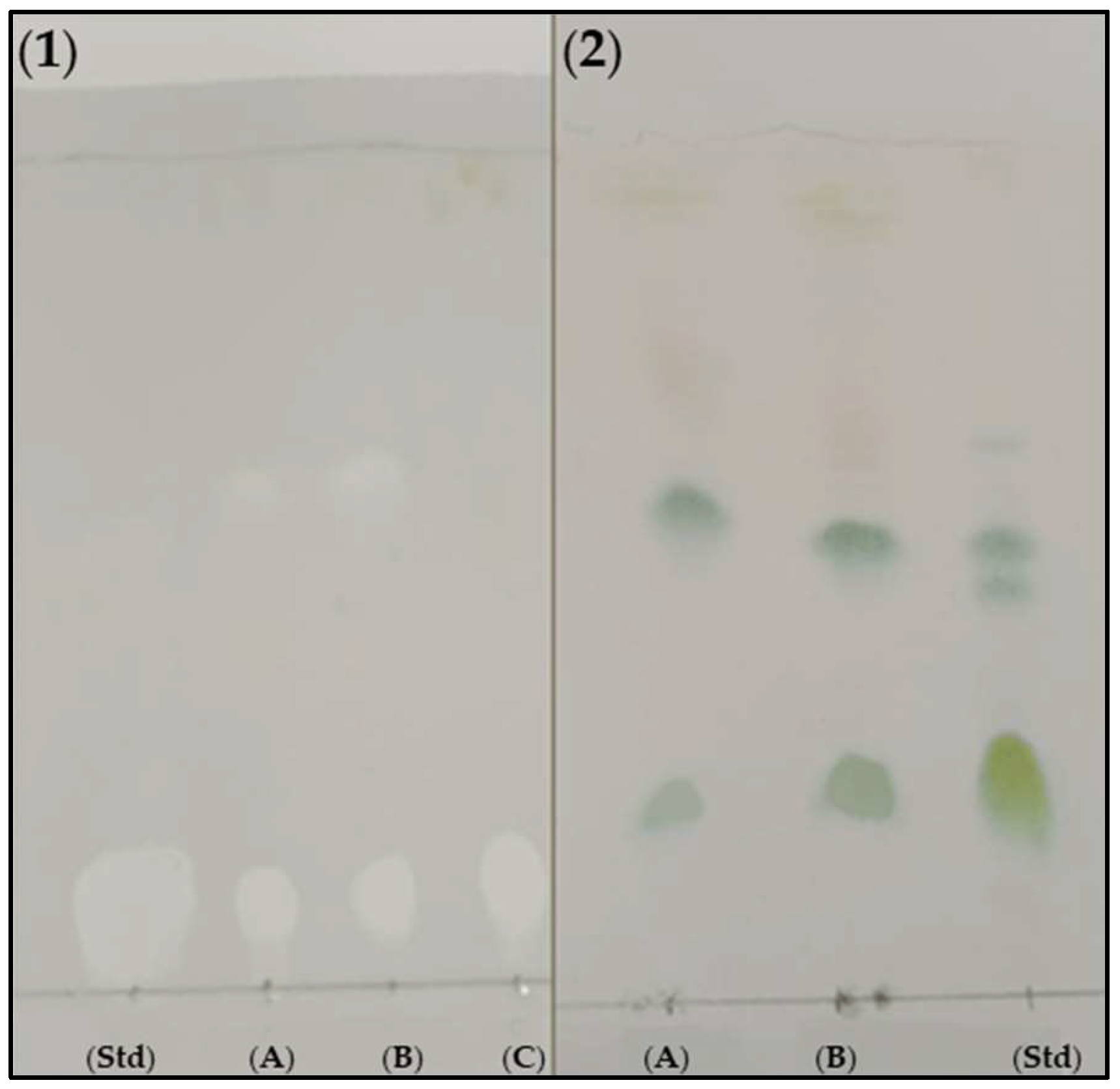

2.5. Qualitative Analysis of the Biosurfactants by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

2.6. pH Analysis

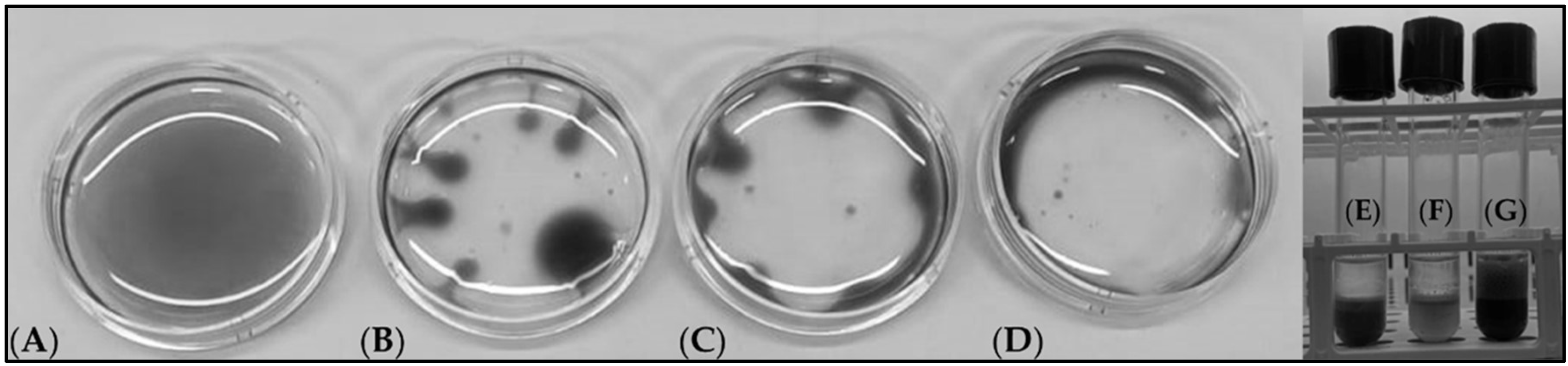

2.7. Microscopic and Macroscopic Monitoring

2.8. Extraction of Rhamnolipids from Fermentation Broths

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of the Agro-Wastes

3.2. Identification of Microorganisms Suitable for Growing on Agricultural Waste

3.3. Production of Biosurfactants from Microbial Strains Grown on Agro-Wastes

3.4. Formulation of a Suitable Fermentation Medium Based on Corn Chaff for the Production of Rhamnolipids

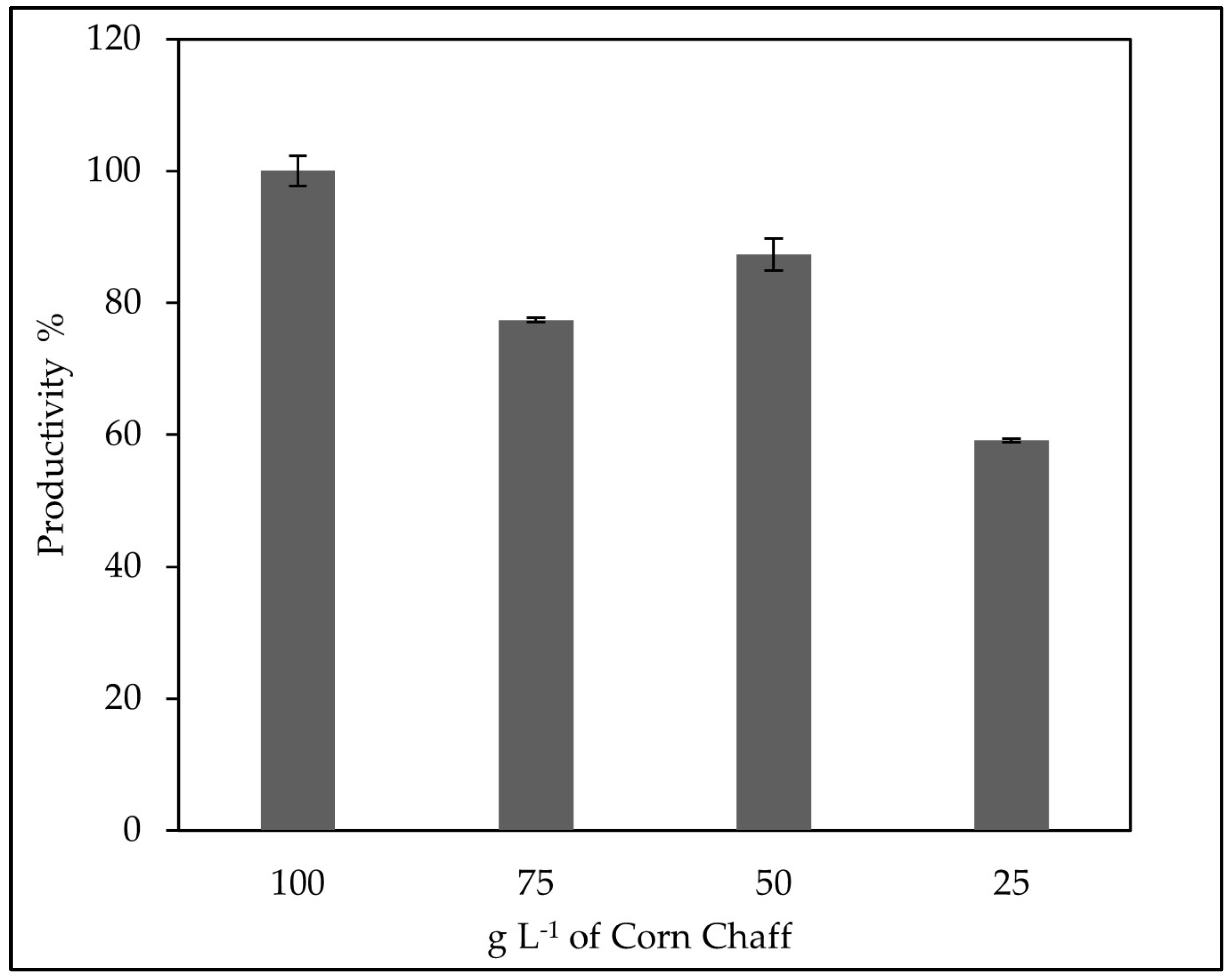

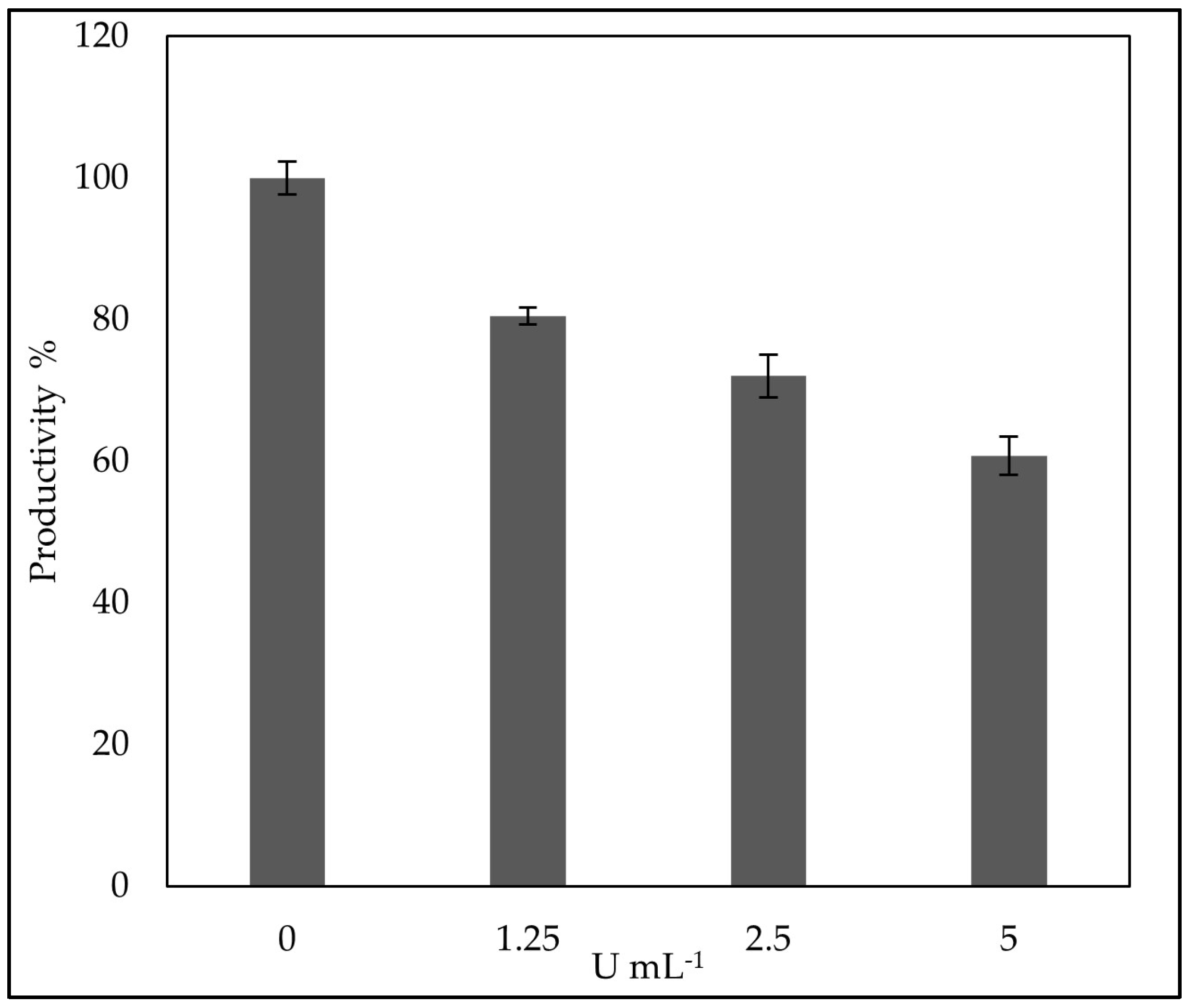

3.5. Evaluation of the Optimal Corn Chaff Concentration and of the Effect of a-Amylase on Rhamnolipids Production

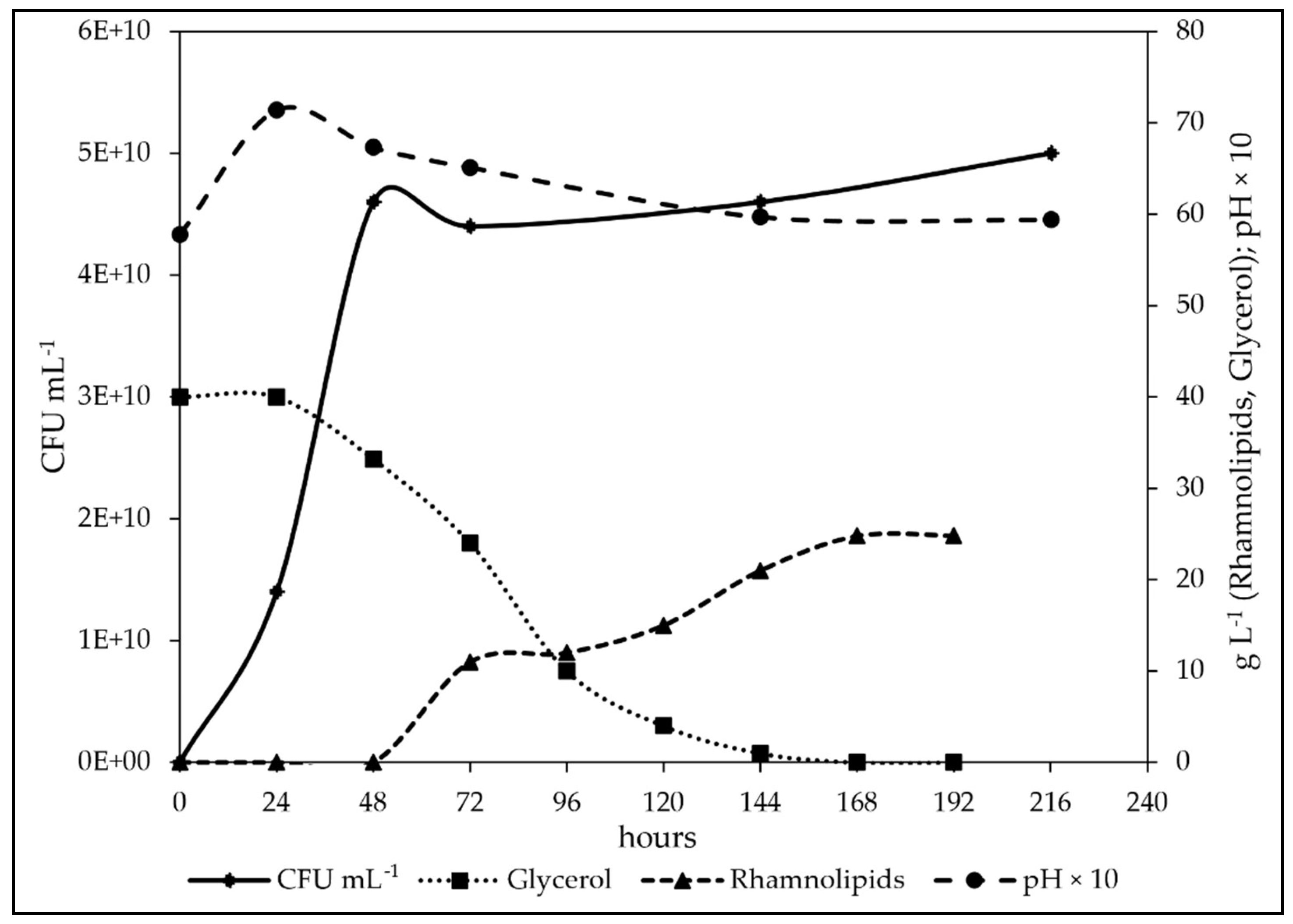

3.6. Study of the Fermentation of P. aeruginosa in Medium BCS388

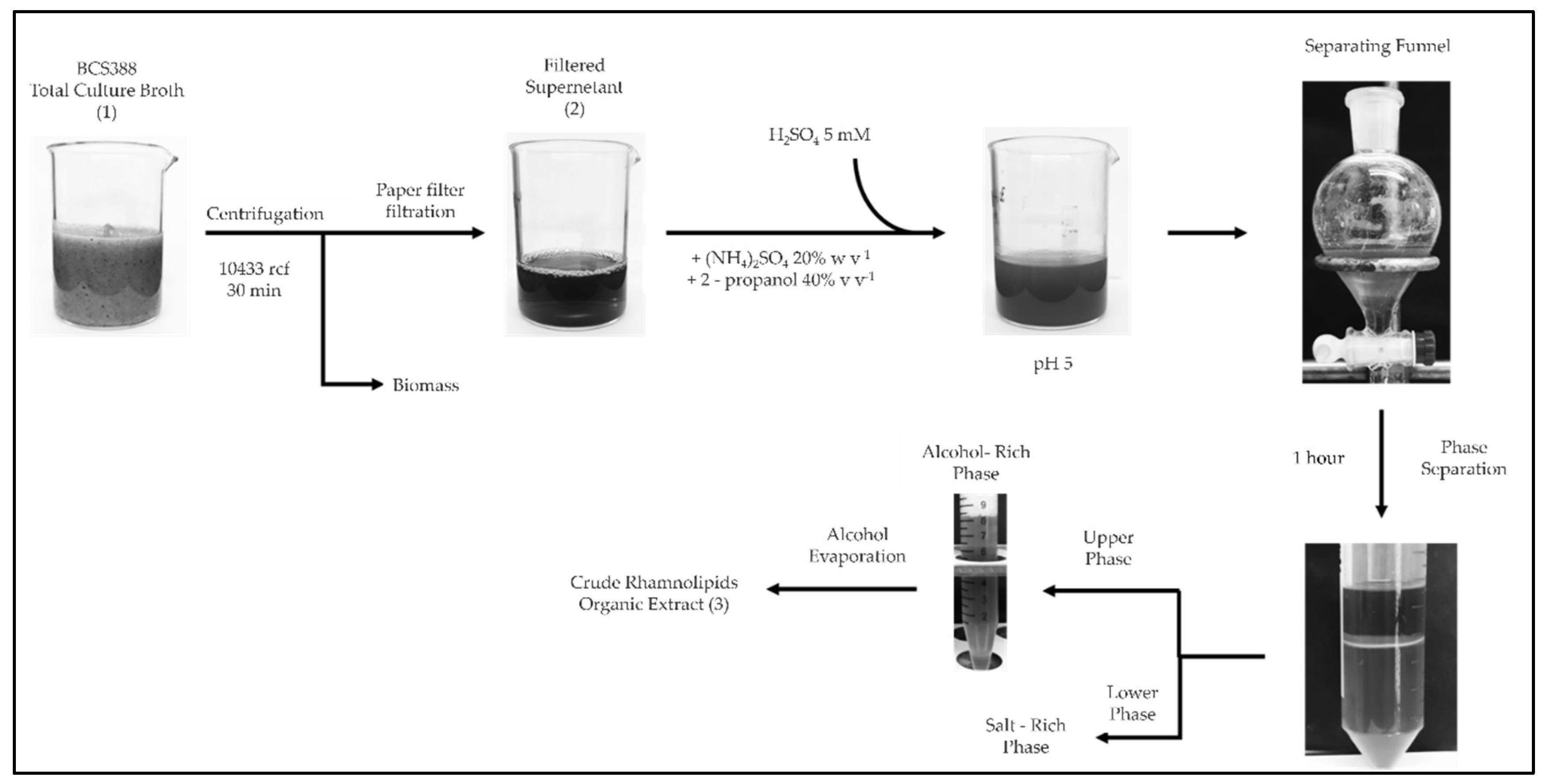

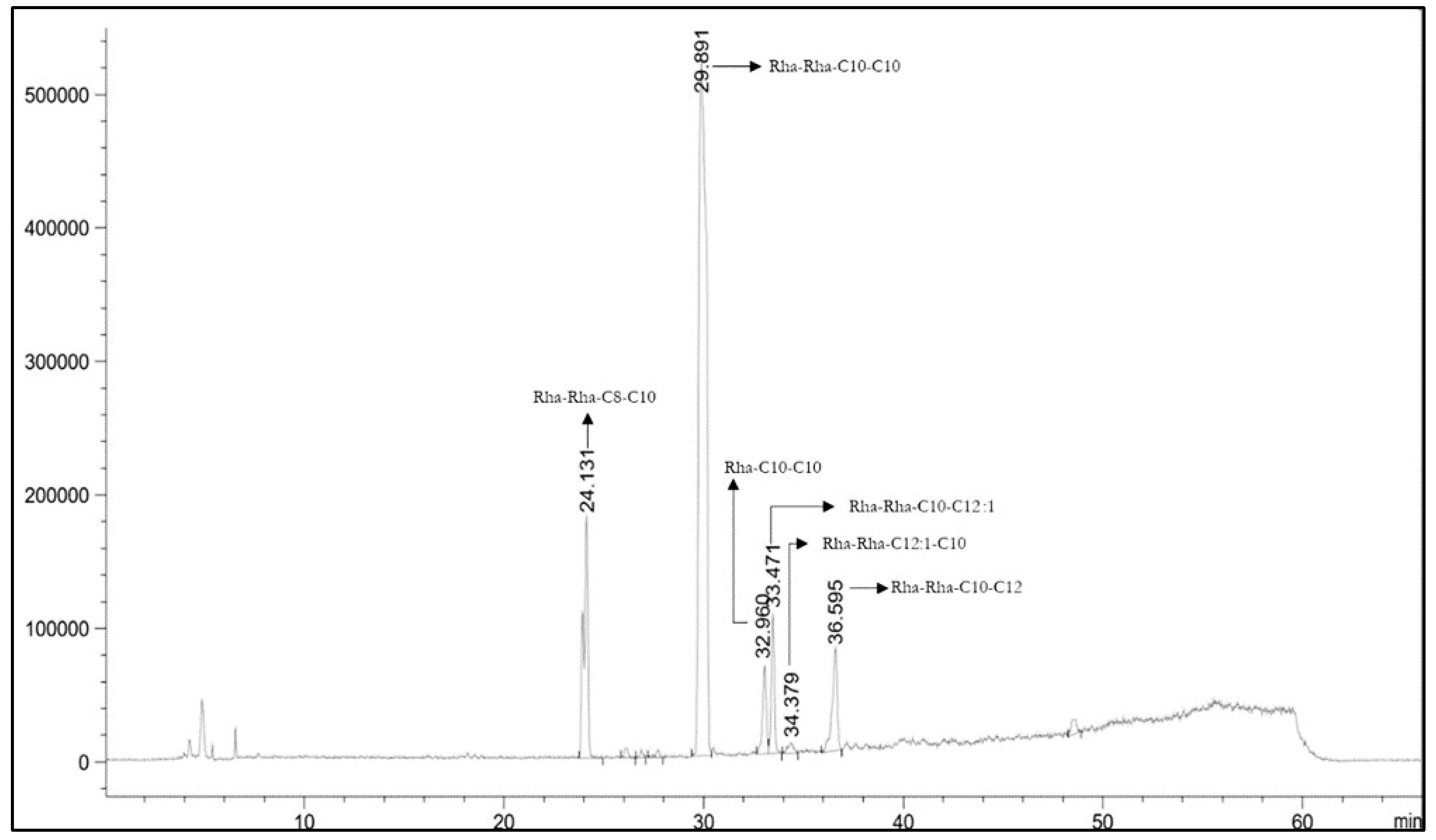

3.7. Purification of Rhamnolipids from Medium BCS388 and Identification of the Different Congeners

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vandamme, E.J. Agro-Industrial Residue Utilization for Industrial Biotechnology Products. Biotechnology for Agro-Industrial Residues Utilisation: Utilisation of Agro-Residues; 2009.

- Belc, N.; Mustatea, G.; Apostol, L.; Iorga, S.; Vlăduţ, V.-N.; Mosoiu, C. Cereal supply chain waste in the context of circular economy. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2019; Volume 112, p. 03031. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, A.; Konrad, R.; Kuhnigk, T.; Kämpfer, P.; Hertel, H.; König, H. Hemicellulose-degrading bacteria and yeasts from the termite gut. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1996, 80, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadh, P.K.; Duhan, S.; Duhan, J.S. Agro-industrial wastes and their utilization using solid state fermentation: a review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Osorio, P.D.; Ramírez-Mejía, J.M.; Mejía-Avellaneda, L.F.; Mesa, L.; Bautista, E.J. Agro-industrial residues for microbial bioproducts: A key booster for bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigiserova, D.A.; Bourgine, J.; Thomsen, M. Closing the loop of cereal waste and residues with sustainable technologies: An overview of enzyme production via fungal solid-state fermentation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo. ; Rubilar, O.; Briceño, G.; Diez, M.C.; Schalchli, H. Advances in Agroindustrial Waste as a Substrate for Obtaining Eco-Friendly Microbial Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, H.M.A.R.; Vieira, I.M.M.; Santos, B.L.P.; Silva, D.P.; Ruzene, D.S. Biosurfactants produced from corncob: a bibliometric perspective of a renewable and promising substrate. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 52, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Hassan, S.S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. A Review on Bioconversion of Agro-Industrial Wastes to Industrially Important Enzymes. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bala, S.; Garg, D.; Sridhar, K.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Singh, R.; Kamma, S.; Tripathi, M.; Sharma, M. Transformation of Agro-Waste into Value-Added Bioproducts and Bioactive Compounds: Micro/Nano Formulations and Application in the Agri-Food-Pharma Sector. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.S.; Koul, Y.; Varjani, S.; Pandey, A.; Ngo, H.H.; Chang, J.-S.; Wong, J.W.C.; Bui, X.-T. A critical review on various feedstocks as sustainable substrates for biosurfactants production: a way towards cleaner production. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, H.L. Batch Submerged Fermentation in Shake Flask Culture and Bioreactor: Influence of Different Agricultural Residuals as the Substrate on the Optimization of Xylanase Production by Bacillus subtilis and Aspergillus brasiliensis. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, J.C.; Oliveira, J.A.d.S.; Pamphile, J.A.; Polonio, J.C. Agro-industrial wastes for biotechnological production as potential substrates to obtain fungal enzymes. 43, e72. [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.L.P.; Jesus, M.S.; Mata, F.; Prado, A.A.O.S.; Vieira, I.M.M.; Ramos, L.C.; López, J.A.; Vaz-Velho, M.; Ruzene, D.S.; Silva, D.P. Use of Agro-Industrial Waste for Biosurfactant Production: A Comparative Study of Hemicellulosic Liquors from Corncobs and Sunflower Stalks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, T.; Govindarajan, R.K.; Vinayagam, S.; Krishnan, V.; Nagarajan, S.; Gnanasekaran, G.R.; Baek, K.-H.; Sekar, S.K.R. Advancements in biosurfactant production using agro-industrial waste for industrial and environmental applications. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1357302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, I.B.; Rodríguez, D.M.; Andradade, R.F.d.S.; Lins, A.B.; Bione, A.P.; da Silva, I.G.S.; Franco, L.d.O.; de Campos-Takaki, G.M. Bioconversion of Agroindustrial Waste in the Production of Bioemulsifier by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia UCP 1601 and Application in Bioremediation Process. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.D.; Banat, I.M. Microbial production of surfactants and their commercial potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzoigwe, C.; Burgess, J.G.; Ennis, C.J.; Rahman, P.K.S.M. Bioemulsifiers are not biosurfactants and require different screening approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajic, J.E.; Guignard, H.; Gerson, D.F. Properties and biodegradation of a bioemulsifier from Corynebacterium hydrocarboclastus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1977, 19, 1303–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Miller, R.M. Enhanced octadecane dispersion and biodegradation by a Pseudomonas rhamnolipid surfactant (biosurfactant). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 3276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Khezerlou, A.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Azadi, Y.; Nattagh-Eshtivani, E.; Fasihi, M.; Ghavami, A.; Aynehchi, A.; Ehsani, A. Bioemulsifiers Derived from Microorganisms: Applications in the Drug and Food Industry. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 8, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgbechidinma, C.L.; Akan, O.D.; Zhang, C.; Huang, M.; Linus, N.; Zhu, H.; Wakil, S.M. Integration of green economy concepts for sustainable biosurfactant production – A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.; Sundaramanickam, A.; Balasubramanian, T. Biosurfactant Producing Microbes and their Potential Applications: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 45, 1522–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, M.; Hausmann, R. Diversity and Classification of Microbial Surfactants. In Biobased Surfactants: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications; 2019.

- Santos, D.K.F.; Rufino, R.D.; Luna, J.M.; Santos, V.A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional Biomolecules of the 21st Century. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, P.; Hajfarajollah, H.; Bazsefidpar, S. Recent advancements in the production of rhamnolipid biosurfactants byPseudomonas aeruginosa. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 34014–34032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Hua, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Potential applications of biosurfactant rhamnolipids in agriculture and biomedicine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 8309–8319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Mawgoud, A.M.; Hausmann, R.; Lépine, F.; Müller, M.M.; Déziel, E. Rhamnolipids: Detection, Analysis, Biosynthesis, Genetic Regulation, and Bioengineering of Production. In; 2011.

- Chong, H.; Li, Q. Microbial production of rhamnolipids: opportunities, challenges and strategies. Microb. Cell Factories 2017, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittgens, A.; Rosenau, F. Heterologous Rhamnolipid Biosynthesis: Advantages, Challenges, and the Opportunity to Produce Tailor-Made Rhamnolipids. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 594010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, P.; Marchant, R.; Naughton, V.; Banat, I. Microbial biosurfactants: current trends and applications in agricultural and biomedical industries. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soberón-Chávez, G.; González-Valdez, A.; Soto-Aceves, M.P.; Cocotl-Yañez, M. Rhamnolipids produced by Pseudomonas: from molecular genetics to the market. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 14, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaligram, N.S.; Singhal, R.S. Surfactin -a Review on Biosynthesis, Fermentation, Purification and Applications. Food Technol Biotechnol 2010, 48. [Google Scholar]

- D'Almeida, A.P.; de Albuquerque, T.L.; Rocha, M.V.P. Recent advances in Emulsan production, purification, and application: Exploring bioemulsifiers unique potentials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 133672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Vaccari, M.; Prasad, S.; Rtimi, S. Preparation, characterization and application of biosurfactant in various industries: A critical review on progress, challenges and perspectives. 24, 1020; 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, D.; Ghosh, S.; Dutta, T.K.; Ahn, Y. Current State of Knowledge in Microbial Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premnath, N.; Mohanrasu, K.; Rao, R.G.R.; Dinesh, G.; Prakash, G.S.; Ananthi, V.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Muthusamy, G.; Arun, A. A crucial review on polycyclic aromatic Hydrocarbons - Environmental occurrence and strategies for microbial degradation. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eras-Muñoz, E.; Farré, A.; Sánchez, A.; Font, X.; Gea, T. Microbial biosurfactants: a review of recent environmental applications. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 12365–12391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.N.; Li, Q. Microbial production of rhamnolipids using sugars as carbon sources. Microb. Cell Factories 2018, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, X.-H.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Chen, Q.-L.; Tang, J.-J.; Liu, D.-Y.; Zou, L.; Wu, X.-Y.; Wang, W. High level expression of bikunin in Pichia pastoris by fusion of human serum albumin. AMB Express 2012, 2, 14–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Li, Q.; Ushimaru, K.; Hirota, M.; Morita, T.; Fukuoka, T. Updated component analysis method for naturally occurring sophorolipids from Starmerella bombicola. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, M.; Dantas, I.T.; Feitosa, F.X.; Alencar, A.E.V.; Soares, S.A.; Melo, V.M.M.; Gonçalves, L.R.B.; Sant'Ana, H.B. Performance of a biosurfactant produced by Bacillus subtilis LAMI005 on the formation of oil / biosurfactant / water emulsion: study of the phase behaviour of emulsified systems. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 31, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Hirata, Y.; Imanaka, T. A study on the structure–function relationship of lipopeptide biosurfactants. 1488. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.G.; Goldenberg, B.G. 1987.

- Zhang, D.; Luo, L.; Jin, M.; Zhao, M.; Niu, J.; Deng, S.; Long, X. Efficient isolation of biosurfactant rhamnolipids from fermentation broth via aqueous two-phase extraction with 2-propanol/ammonium sulfate system. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buniowska, M.; Znamirowska, A.; Sajnar, K.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kluz, M. EFFECT OF ADDITION OF SPELT AND BUCKWHEAT HULL ON SELECTED PROPERTIES OF YOGHURT. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2020, 10, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandam, P.K.; Chinta, M.L.; Gandham, A.P.; Pabbathi, N.P.P.; Konakanchi, S.; Bhavanam, A.; Atchuta, S.R.; Baadhe, R.R.; Bhatia, R.K. A New Insight into the Composition and Physical Characteristics of Corncob—Substantiating Its Potential for Tailored Biorefinery Objectives. Fermentation 2022, 8, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, E.A.; Gladysheva, E.K.; Budaeva, V.V.; Aleshina, L.A.; Sakovich, G.V. Yield and quality of bacterial cellulose from agricultural waste. Cellulose 2022, 29, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, M.; Bakshi, M.P.S. Utilization of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes as Livestock Feed and as Substrates for Generation of Other Value-Added Products; 2013.

- Baumann’, P. Isolation of Acinetobacter from Soil and Water; 1968, 96.

- Ren, X.; Palmer, L.D. Acinetobacter Metabolism in Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance. Infect. Immun. 2023, 91, e0043322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koim-Puchowska, B.; Kłosowski, G.; Dróżdż-Afelt, J.M.; Mikulski, D.; Zielińska, A. Influence of the Medium Composition and the Culture Conditions on Surfactin Biosynthesis by a Native Bacillus subtilis natto BS19 Strain. Molecules 2021, 26, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bogaert, I.N.A.; Saerens, K.; De Muynck, C.; Develter, D.; Soetaert, W.; Vandamme, E.J. Microbial production and application of sophorolipids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsirichot, P.; Ingham, B.; Winterburn, J. A review of sophorolipid production from alternative feedstocks for the development of a localized selection strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyukina, M.S.; Ivshina, I.B. Bioremediation of Contaminated Environments Using Rhodococcus. In; 2019, 231–270.

- Nazari, M.T.; Simon, V.; Machado, B.S.; Crestani, L.; Marchezi, G.; Concolato, G.; Ferrari, V.; Colla, L.M.; Piccin, J.S. Rhodococcus: A promising genus of actinomycetes for the bioremediation of organic and inorganic contaminants. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.K.; Singh, G.; Rani, N.; Rajput, V.D.; Seth, C.S.; Dwivedi, P.; Minkina, T.; Wong, M.H.; Show, P.L.; Khoo, K.S. Transforming bio-waste into value-added products mediated microbes for enhancing soil health and crop production: Perspective views on circular economy. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, M.; Niu, R.; Minami, E.; Saka, S. Characterization of three tissue fractions in corn (Zea mays) cob. Biomass- Bioenergy 2018, 115, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Mondal, I.H.; Yeasmin, M.S.; Abu Sayeed, M.; Hossain, A.; Ahmed, M.B. Conversion of Lignocellulosic Corn Agro-Waste into Cellulose Derivative and Its Potential Application as Pharmaceutical Excipient. Processes 2020, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Bryam, A.M.; Lovaglio, R.B.; Contiero, J. Biodiesel byproduct bioconversion to rhamnolipids: Upstream aspects. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00337–e00337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleator, R.D.; Hill, C. Bacterial osmoadaptation: the role of osmolytes in bacterial stress and virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 26, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.U.H.; Sivapragasam, M.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Yusup, S.B. A comparison of Recovery Methods of Rhamnolipids Produced by Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Hassan, S.S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. A Review on Bioconversion of Agro-Industrial Wastes to Industrially Important Enzymes. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Sanchez, M.; Inocencio-García, P.-J.; Alzate-Ramírez, A.F.; Alzate, C.A.C. Potential and Restrictions of Food-Waste Valorization through Fermentation Processes. Fermentation 2023, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effiong, E.; Agwa, O.K.; Abu, G.O. Optimization of Biosurfactant Production by a Novel Rhizobacterial Pseudomonas Species.

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Caldwell, G.A.; Zachgo, E.A. Protein Assays. Biotechnology 1996, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus | Species | ID | Reference Cultural Medium | Application of the Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter | Sp. | MAD90 | ||

| Bacillus | subtilis | MAD3 | BCS340 | Surfactin production |

| Rhodococcus | erythropolis | MAD02B | BCS346 BCS333 BCS342 |

Bioremediation of hydrocarbons and accumulation of cesium isotopes Triacylglyceroles biosynthesis Biotransformation of acrylonitrile into acrylammide PHA synthesis Hydrocarbons biotransformation |

| Candida | bombicola | MADS | BCS343 | Production of Sophorolipids |

| Pseudomonas | aeruginosa | MAD10 | BCS340 | Production of Rhamnolipids |

| Instrument: | Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity |

| Column: | Aminex HPX-87H (BioRad) 300 × 7.8 mm |

| Mobile Phase: | 5 mM sulfuric acid |

| Flux: | 0.6 ml min-1 |

| Gradient: | isocratic |

| Injection: | 10 µl |

| Temperature: | 30 °C |

| Detector: | Refractive Index Detector (RID) |

| Time: | 30 minutes |

| Column: | Hypersil ODS 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm | ||

| Mobile phase A | 10 mM Ammonium acetate (MeCOONH4) pH 7.4 | ||

| Mobile phase B | Acetonitrile (MeCN) : 10 mM Ammonium acetate (MeCOONH4) pH 7.4 = 80:20 | ||

| Flow | 0.5 mL min-1 | ||

| Injection Volume | 20 µL | ||

| Detector | UV (λ = 230 nm) | ||

| MS | 4000 V, negative, 200 / 1000 m z-1, frag:VAR | ||

| Temperature: | 25 °C | ||

| Gradient: | Time (min) | Mobile phase A (%) | Mobile phases B (%) |

| 0 | 70 | 30 | |

| 50 | 10 | 90 | |

| 55 | 10 | 90 | |

| 56 | 70 | 30 | |

| 66 | 70 | 30 | |

| Stop time | 66 minutes | ||

| Column | LiCrosphere RP18 (150 × 4,6 mm, 5 µm) |

| Mobile Phase | Water:acetonitrile:trifluoroacetic acid 20:80:0.025% |

| Flow | 1 mL min-1 |

| Gradient | Isocratic |

| Injection volume | 10 µL |

| Temperature | 25 °C |

| Detector | UV (λ = 205 nm) |

| Stop Time | 25 minutes |

| Strain | ID | Oat and Emmer Chaff | Corn Chaff | Proteic pea pod hull | Control | Biosurfactant produced in control conditions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter sp. | MAD90 | 1.1 × 1010 | - | 9.0 × 109 | - | 5.0 × 109 | - | 9.0 × 109 | + | Emulsan |

| Bacillus subtilis | MAD3 | 3.7 × 109 | + | 1.3 × 109 | + | 7.6 × 109 | + | 5.5 × 109 | + | Surfactin |

| Candida bombicola | NA | 1.0 × 109 | - | 2.7 ×109 | - | 3.8 × 108 | - | 7.5 × 107 | + | Sophorolipids |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

MAD10 | 4.3 × 109 | - | 2.7 × 1010 | + | 2.2 × 1010 | - | 7.0 × 109 | + | Rhamnolipids |

| Rhodococcus sp. | MADO2B | 1.4 × 109 | - | 1.7 × 109 | - | 4.3 × 109 | - | 5.0 × 109 | + | Trehalolipids |

| Trial ID# | Components of the Fermentation Medium | Amount for each Component (g L-1) | Maximum Rhamnolipids Production Achieved (g L-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Corn Chaff | 100 | 11.8 |

| Glycerol | 40 | ||

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| B | Corn Chaff | 100 | 9.4 |

| Glycerol | 40 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| C | Corn Chaff | 100 | 17.9 |

| Glycerol | 40 | ||

| Soybean Oil | 20 | ||

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| D | Corn Chaff | 100 | 16.4 |

| Glycerol | 40 | ||

| WCO | 20 | ||

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| E | Corn Chaff | 100 | 11.1 |

| Glycerol | 60 | ||

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| F | Corn Chaff | 100 | 8.1 |

| Soybean Oil | 20 | ||

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| G* | Glycerol | 40 | 0.0*** |

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| H | Corn Chaff | 100 | < 2.0** |

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| I* | Soybean Oil | 20 | 0.0*** |

| NaNO3 | 2 | ||

| KH2PO4 | 1 | ||

| J | Oat and Emmer Hull | 50 | < 2.0** |

| Corn Chaff | 50 | ||

| K* | Oat and Emmer Hull | 50 | 0.0*** |

| Pea pod hull | 50 | ||

| L | Corn Chaff | 100 | < 2.0** |

| M | Corn Chaff | 100 | 8.6 |

| Soybean Oil | 20 | ||

| N | Corn Chaff | 100 | 6.1 |

| WCO | 20 | ||

| O | BCS340 (positive control) | Industrial Medium | 15.0 |

| Sample | pH | Concentration | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| g L-1 | % | ||

| Total culture broth (1) | 6.2 | 12.5 | 100 |

| Filtered Supernatant (2) | 6.2 | 92 | |

| Organic extract (3) | 63.4 |

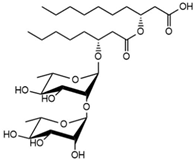

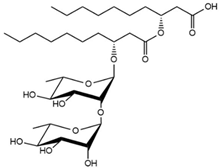

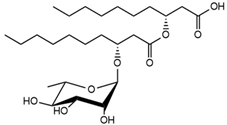

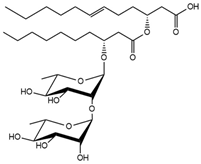

| Rt (min) | Compound | Structure | Area % |

|---|---|---|---|

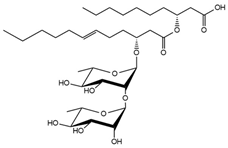

| 24.13 | Rha-Rha-C8-C10 Rha-Rha-C10-C8 |

|

13.44 |

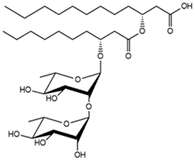

| 27.53 | Rha-Rha-C10-C10 |  |

66.87 |

| 30.26 | Rha-C10-C10 |  |

4.18 |

| 30.82 | Rha-Rha C10-C12:1 |  |

13.1 |

| 31.67 | Rha-Rha-C12:1-C10 |  |

< 1.5 |

| 3.78 | Rha-Rha-C10-C12 Rha-Rha-C12-C10 |

|

< 1.5 |

| RLs Tot considered | 97.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).