Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms

- Lactic acid bacteria. The research in the present work was carried out with 11 LAB strains, designated as: LAB 4/20, LAB 12/20, LAB 5/20, LAB 6/20, LAB 8/20, LAB 9/20, LAB 10/20, LAB 13/20, LAB 16/20, LAB 19/20, LAB 22/20, isolated from rose blossom of Rosa damascena Mill.

- Pathogenic test-microorganisms for the determination of the antimicrobial activity against pathogens. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Salmonella abony NTCC 6017, Proteus vulgaris J, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212.

2.2. Nutrient Media:

- MRS-broth (Merck); MRS-agar (Merck); 0.5 % NaCl solution (Merck); LAPTg10-broth; LAPTg10-agar; LBG-broth; LBG-agar

- LAPTg10–broth. Composition (g/dm3): peptone – 15; yeast extract – 10; tryptone – 10; glucose – 10. The pH was adjusted to 6.6 – 6.8 and Tween 80 - 1cm3/dm3 was added. Sterilization - 20 min at 121 °С.

- LAPTg10-agar. Composition (g/dm3): LAPTg10-broth, agar - 20. Sterilization - 20 min at 121 °С.

- LBG-broth. Composition (g/dm3): tryptone - 10; yeast extract - 5; NaCl - 10; glucose - 10 Sterilization - 20 min at 121 °C.

- LBG-agar. Composition (g/dm3): tryptone - 10; yeast extract - 5; NaCl - 10; glucose - 10 agar - 15. Sterilization - 20 min at 121 °C

2.3. Physiological and Biochemical Methods

2.3.1. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria

2.3.2. Determination of the Titratable Acidity

2.3.3. Determination of the Number of Viable Microorganisms

2.3.4. Determination of the Biochemical Profile

2.3.5. Determination of the Antibiotic Susceptibility Profile

- Cell wall synthesis: Penicillin, Ampicillin, Oxacillin, Piperacillin, Amoxicillin, Bacitracin, Vancomycin

- Protein synthesis: Tetracycline, Doxycycline, Tobramycin, Amikacin, Gentamicin, Erythromycin, Chloramphenicol, Lincomycin

- DNA synthesis and cell division: Nalidixic acid, Ciprofloxacin, Novobiocin, Rifampin

2.3.6. Determination of the Antimicrobial Activity Against Pathogens – Agar-Diffusion Method with Wells

2.4. Molecular-Genetic Methods

2.4.1. Sequencing of the 16S rRNA Gene

2.5. Batch Cultivation

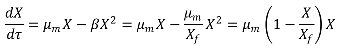

2.6. Modeling of the Process Kinetics and Identification of the Model Parameters

2.7. Freeze-Drying

2.8. Microbiological Studies of the Lyophilized Concentrate

2.8.1. Microbiological Status of Native and Lyophilized Samples

- lactic acid bacteria, CFU/g [19];

- total number of mesophilic aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria – CFU/g [20];

- Escherichia coli in 0.1 g of the product [21];

- pathogenic microorganisms, including Salmonella sp. in 25.0 g of the product [22];

- coagulase-positive staphylococci in 1.0 g of the product [23];

- sulfite-reducing clostridia in 0.1 g of product [24];

- microscopic mold spores, CFU/g [25];

- yeast, CFU/g [25];

2.9. Processing of the Results

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation, Identification and Selection of LAB Strains from the Rose Blossom of Rosa damascena Mill L.

3.1.1. Isolation and Identification of LAB Strains

- A. Phenotypic characteristics of the newly isolated LAB strains

- B. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of the isolated strains

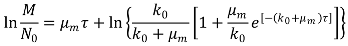

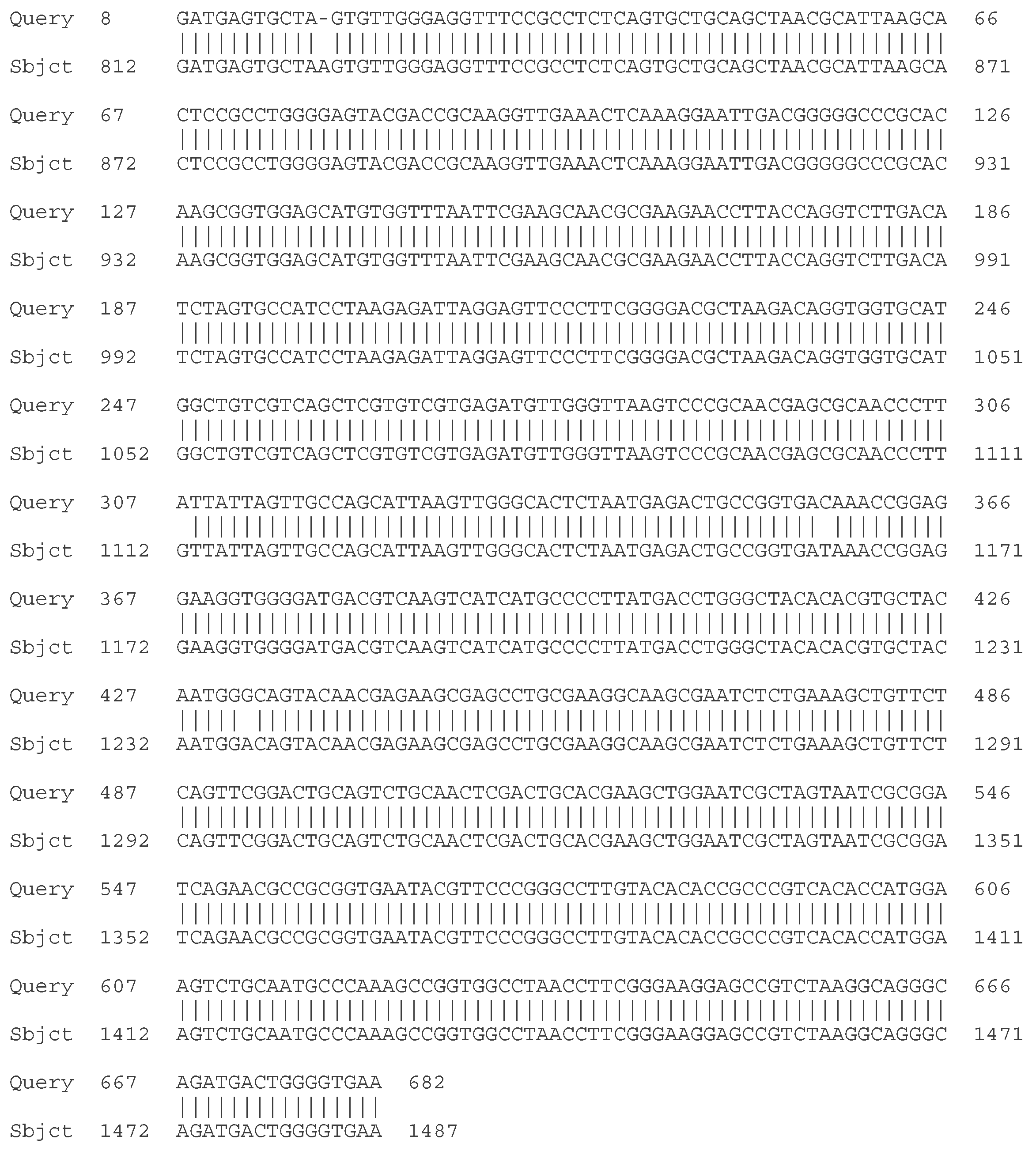

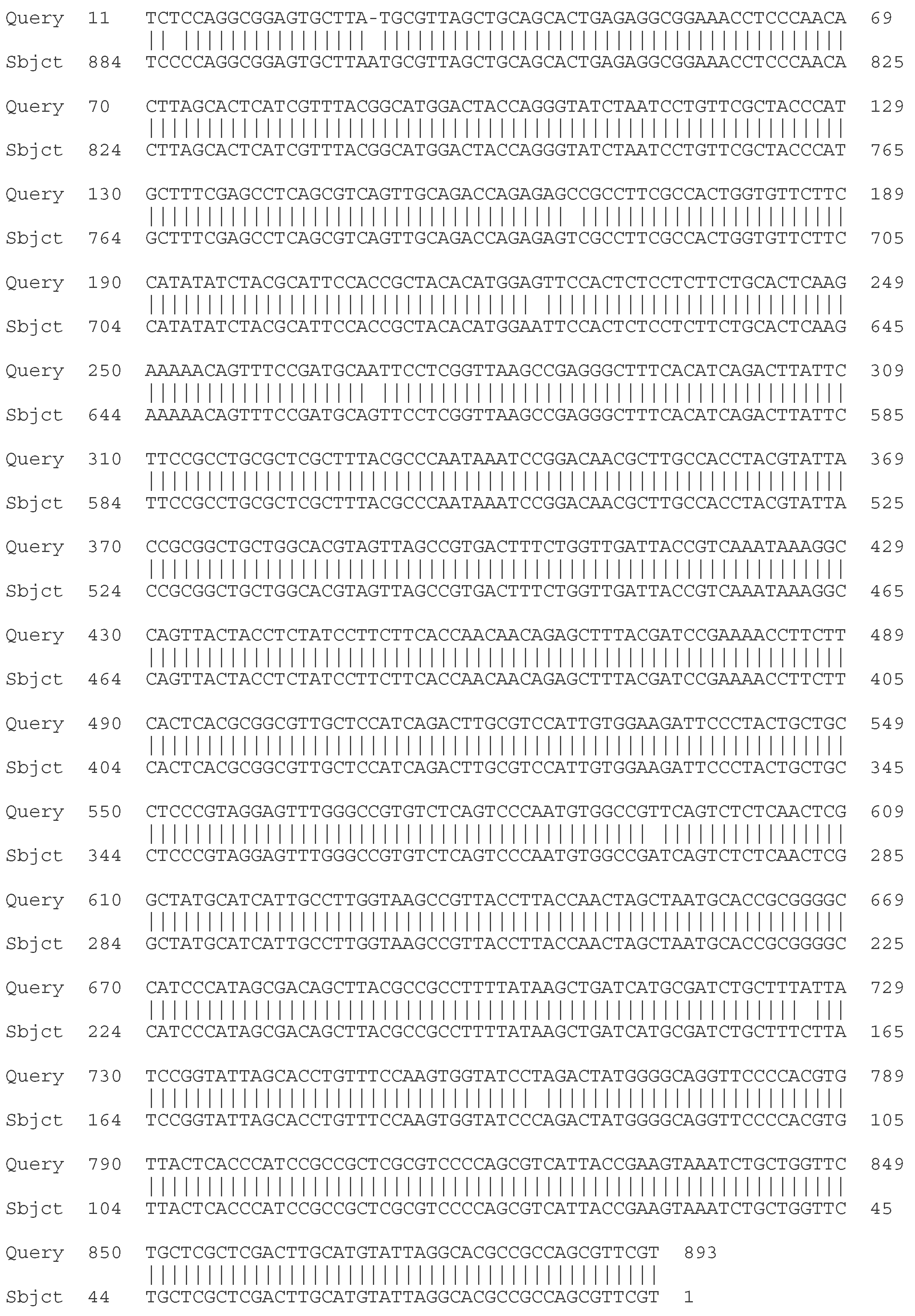

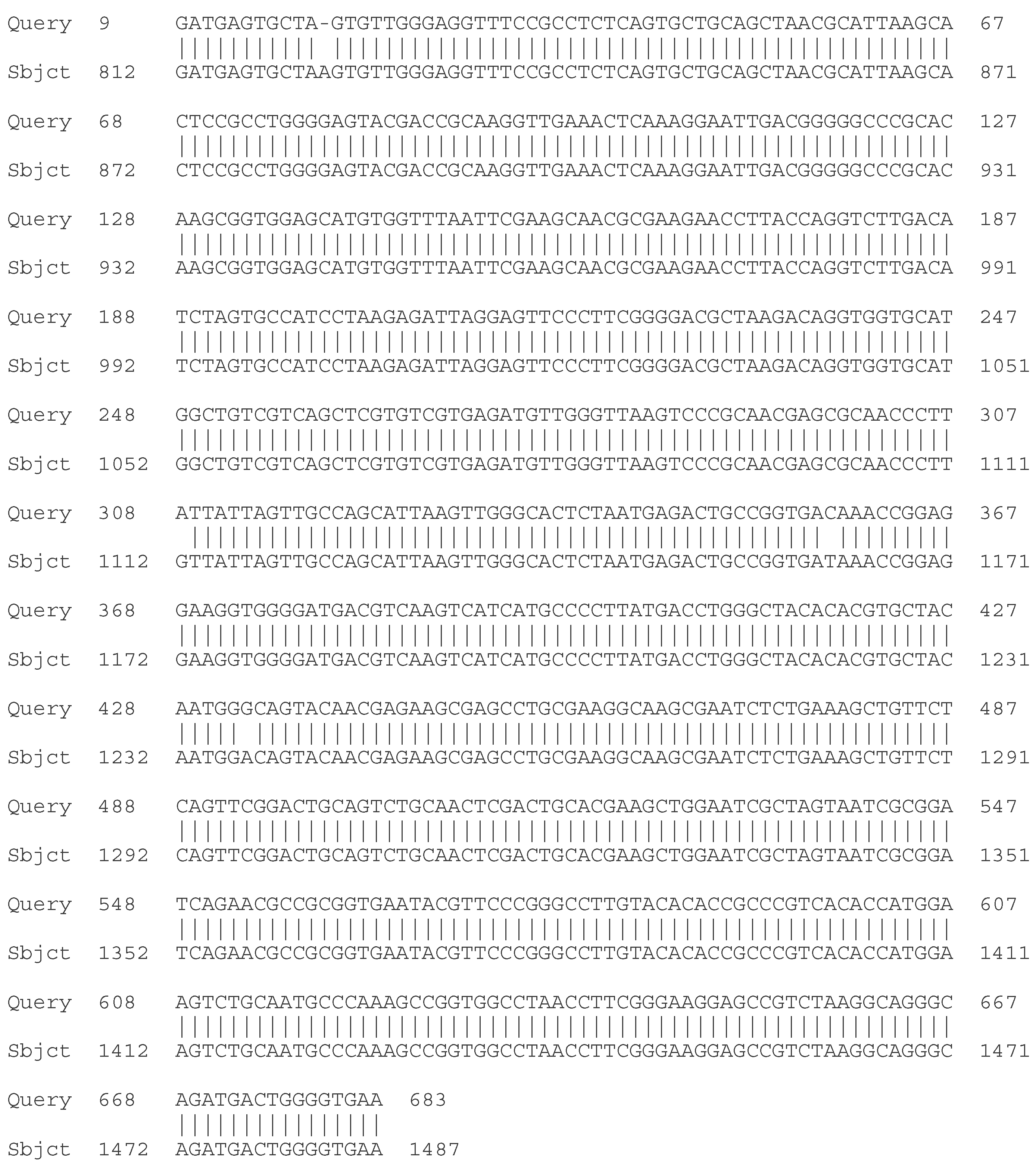

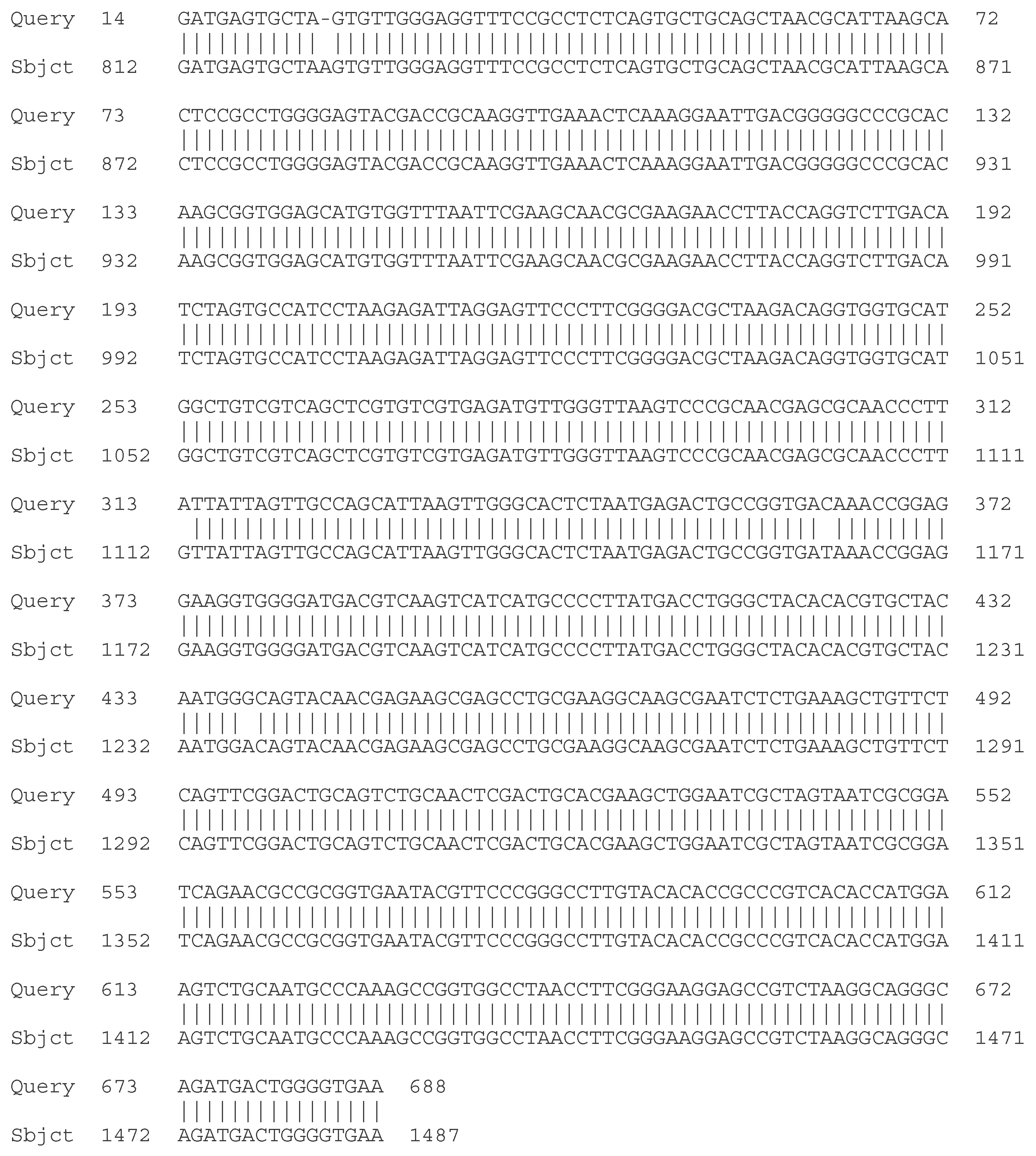

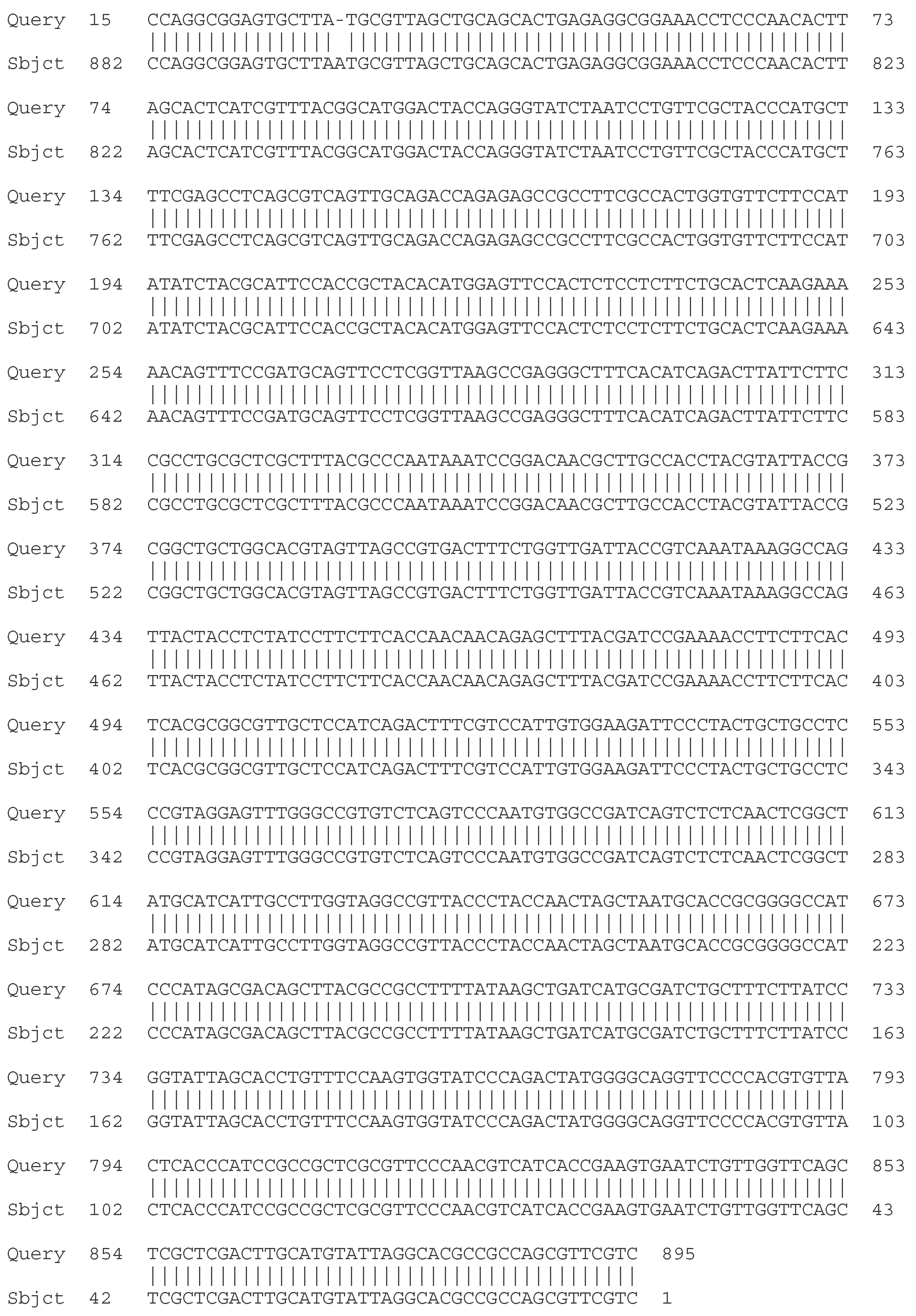

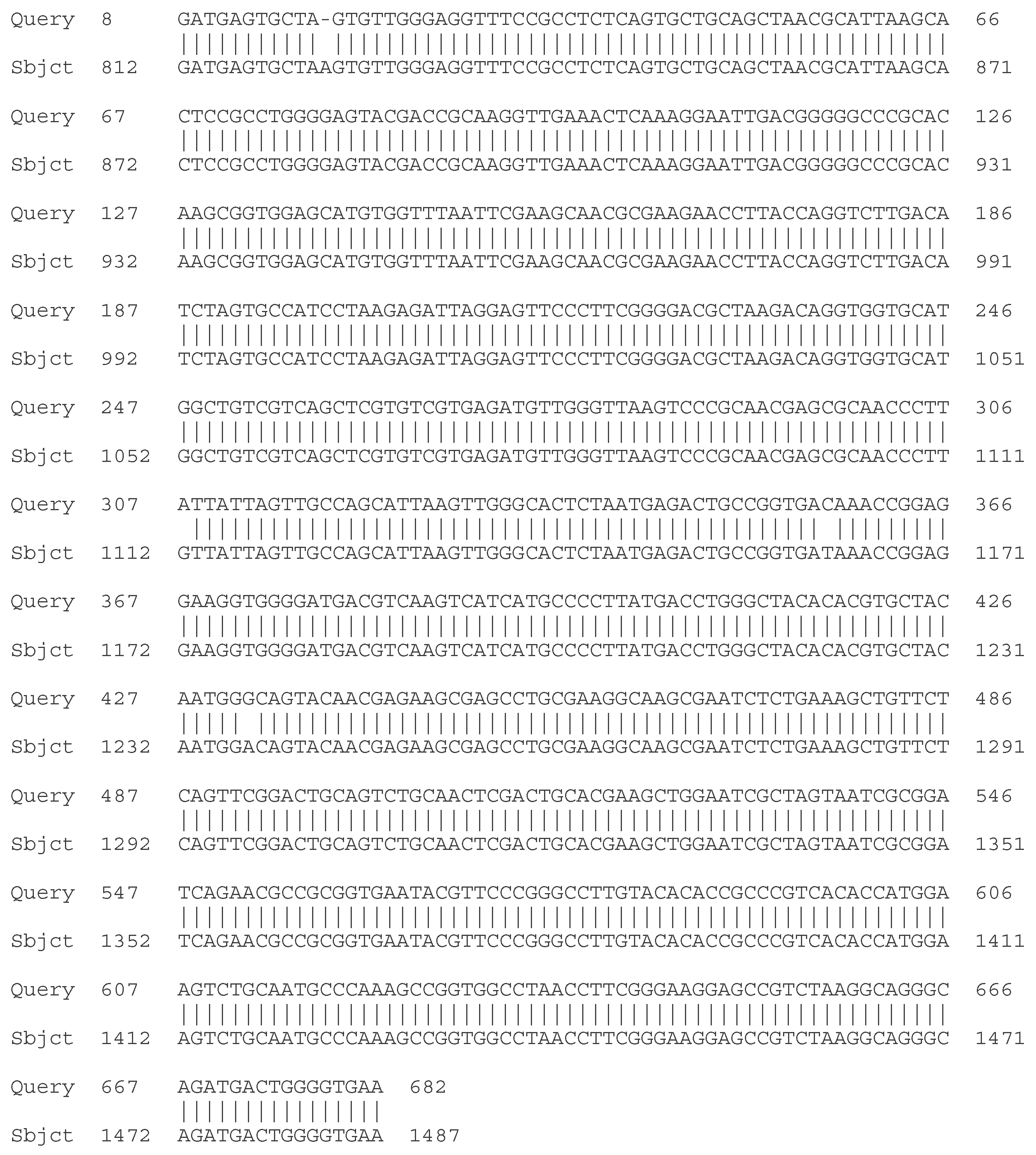

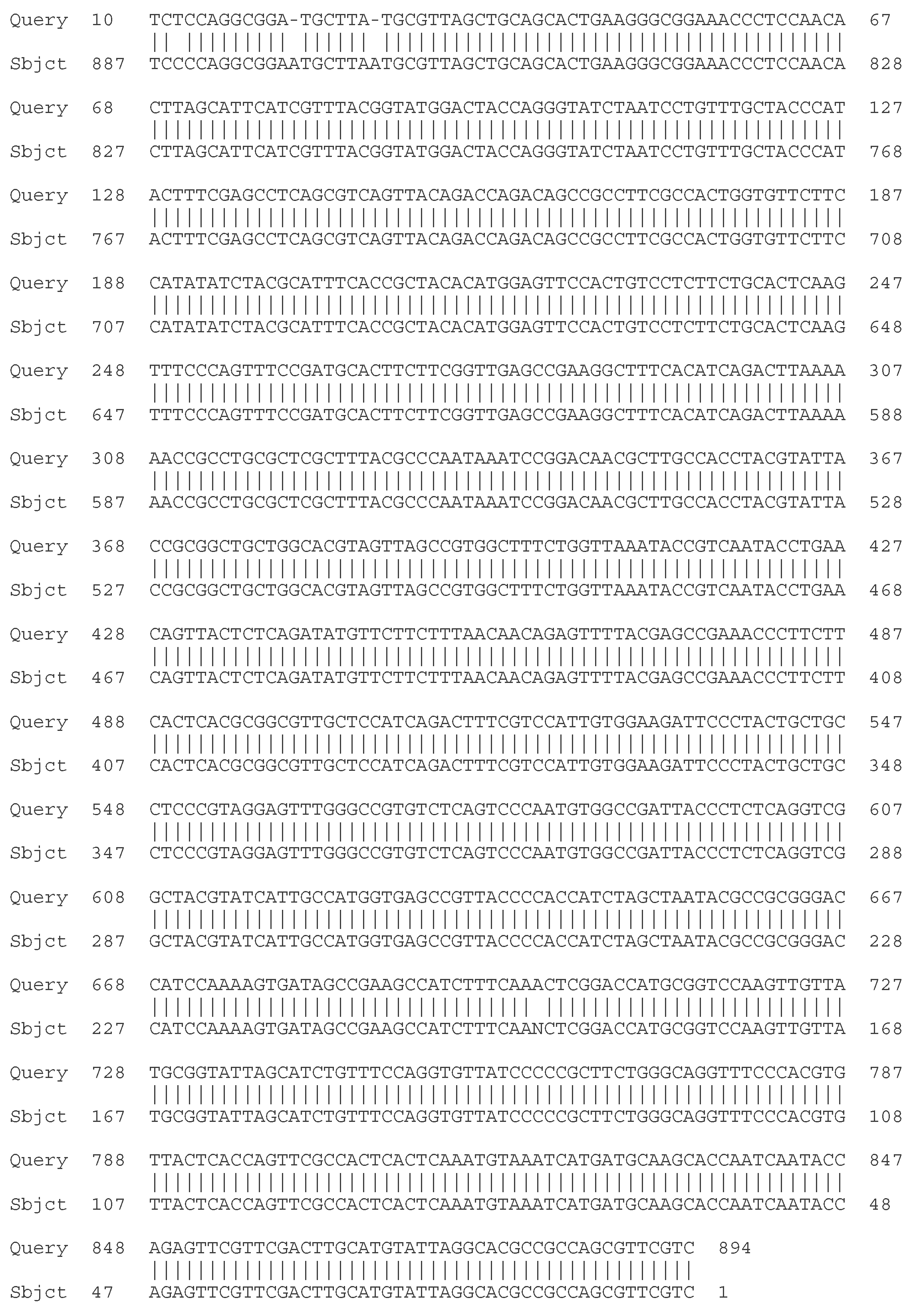

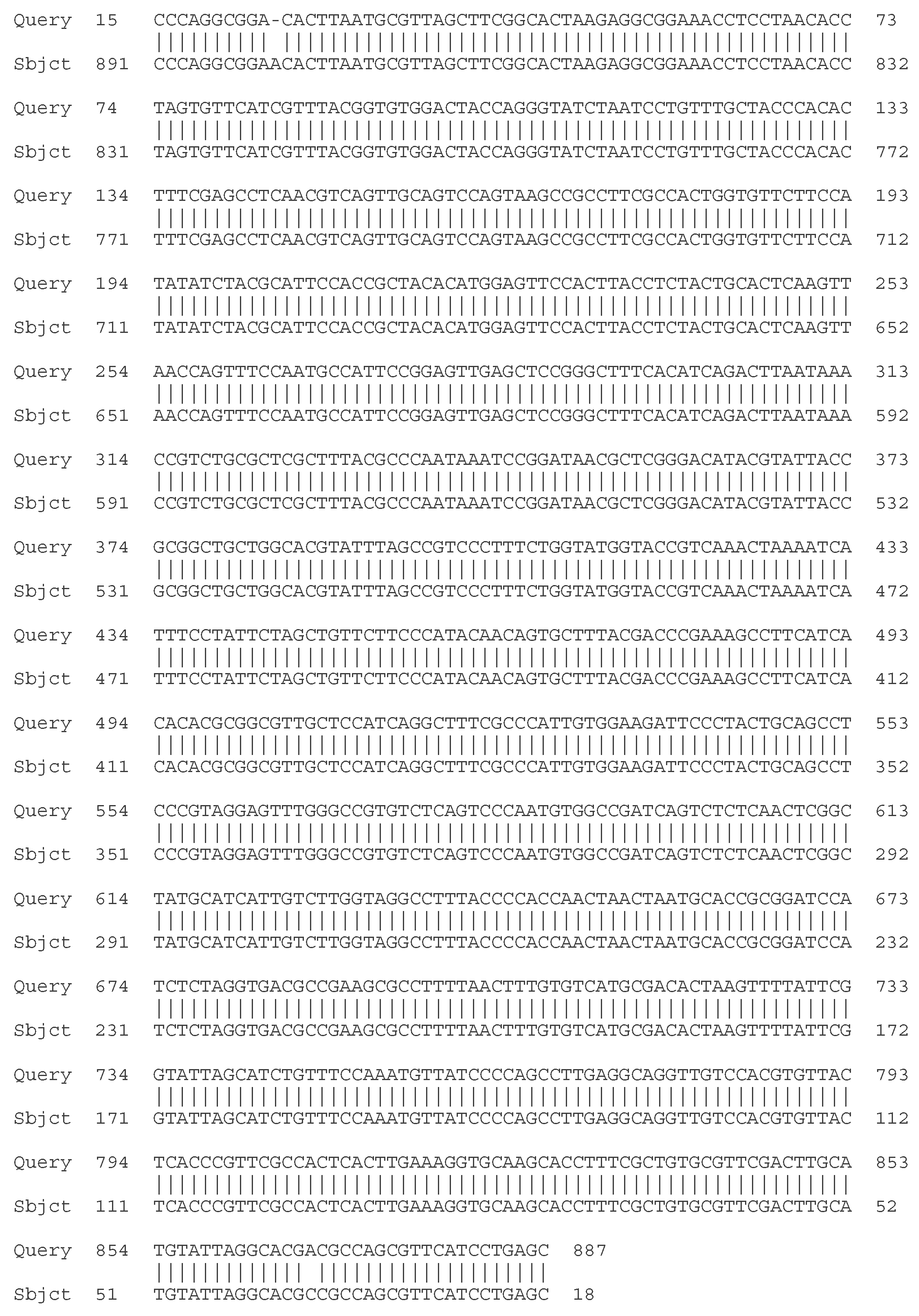

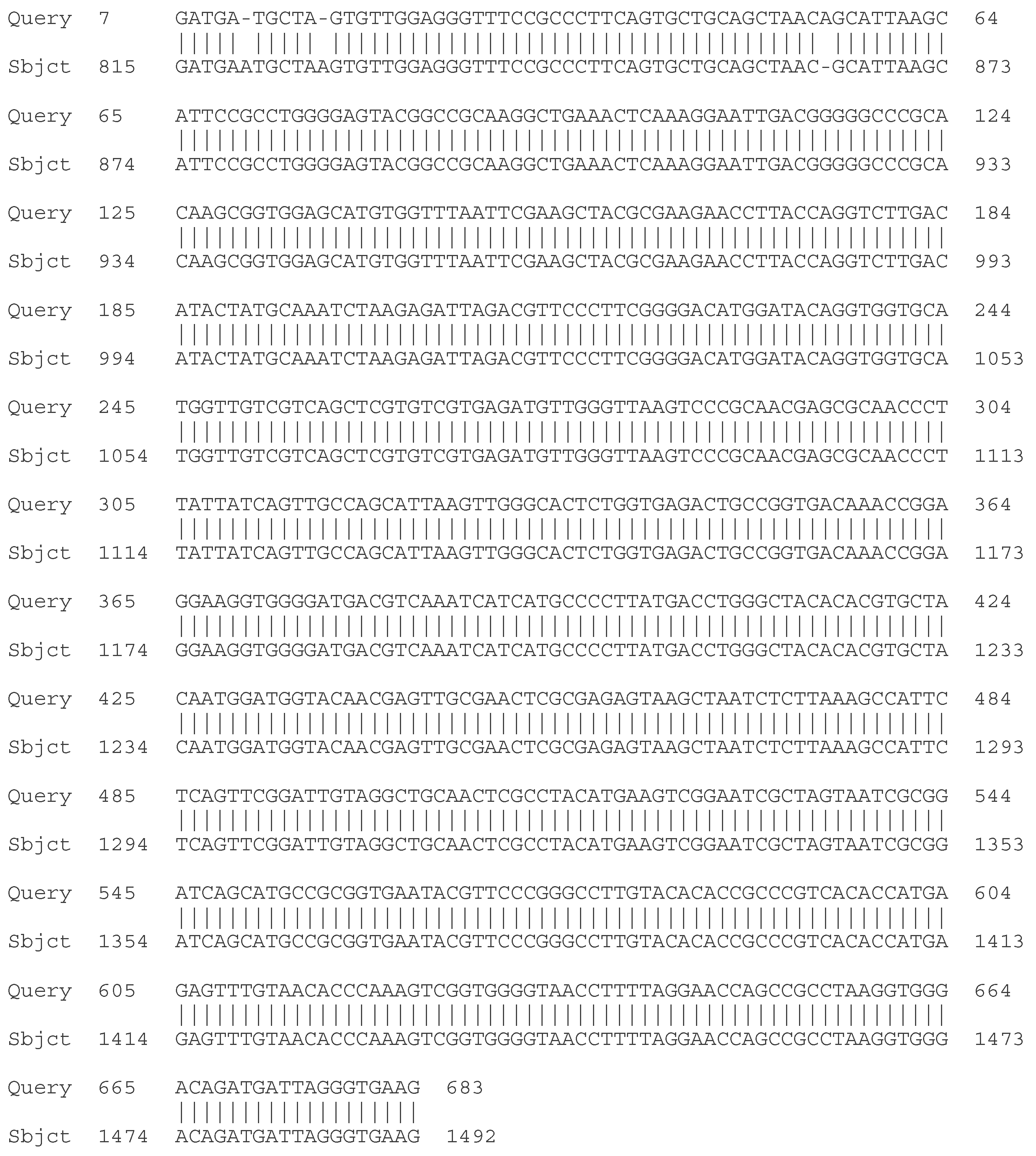

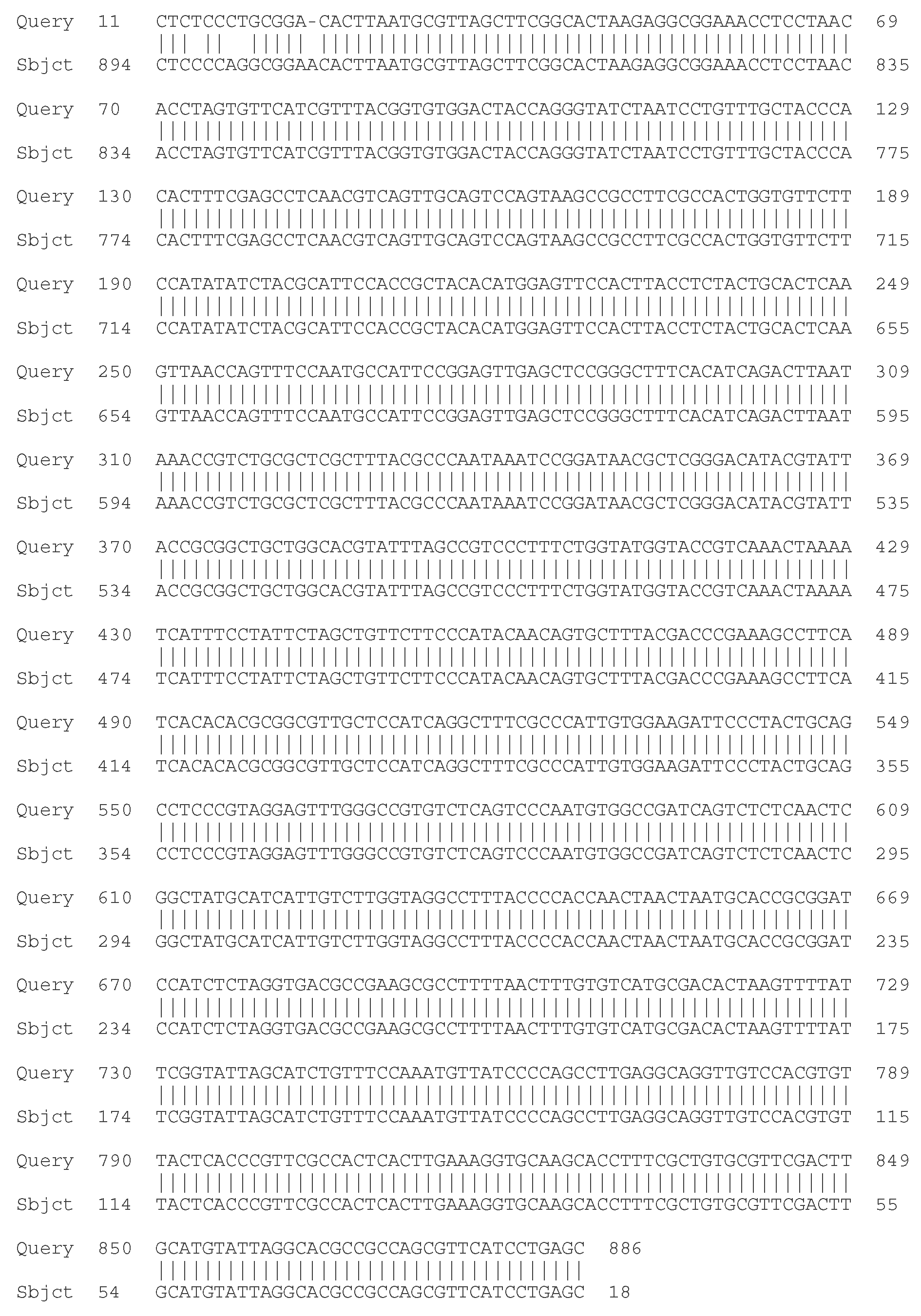

- C. Molecular - taxonomic characterization. Genotypic characteristics of the studied LAB strains. Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene

3.2. Characterization of the Probiotic Potential of the Isolated Lactobacilli

3.2.1. Antimicrobial Activity of the Isolated LAB Strains Against Pathogenic Microorganisms

3.2.2. Antibiotic Resistance of the Isolated LAB Strains

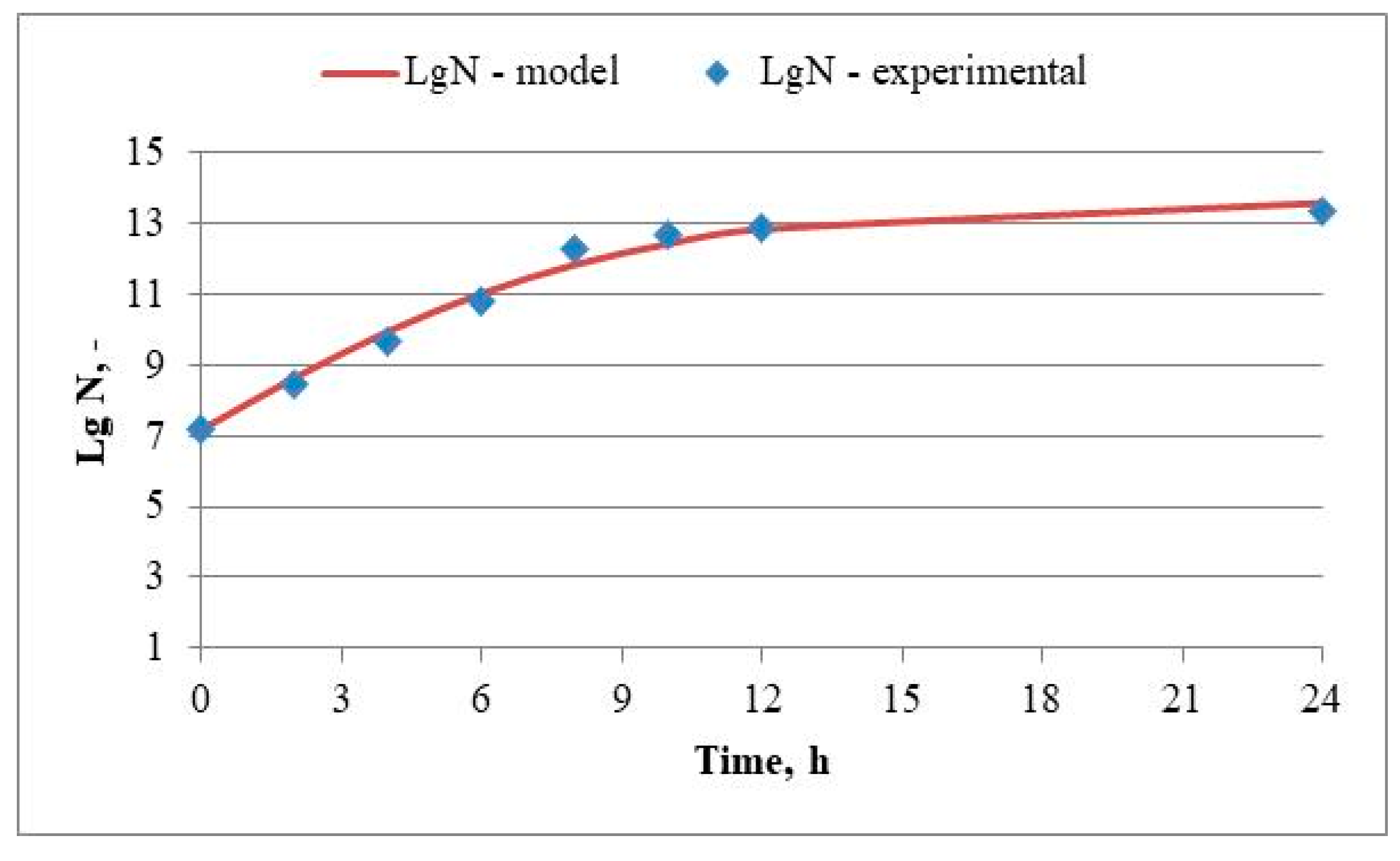

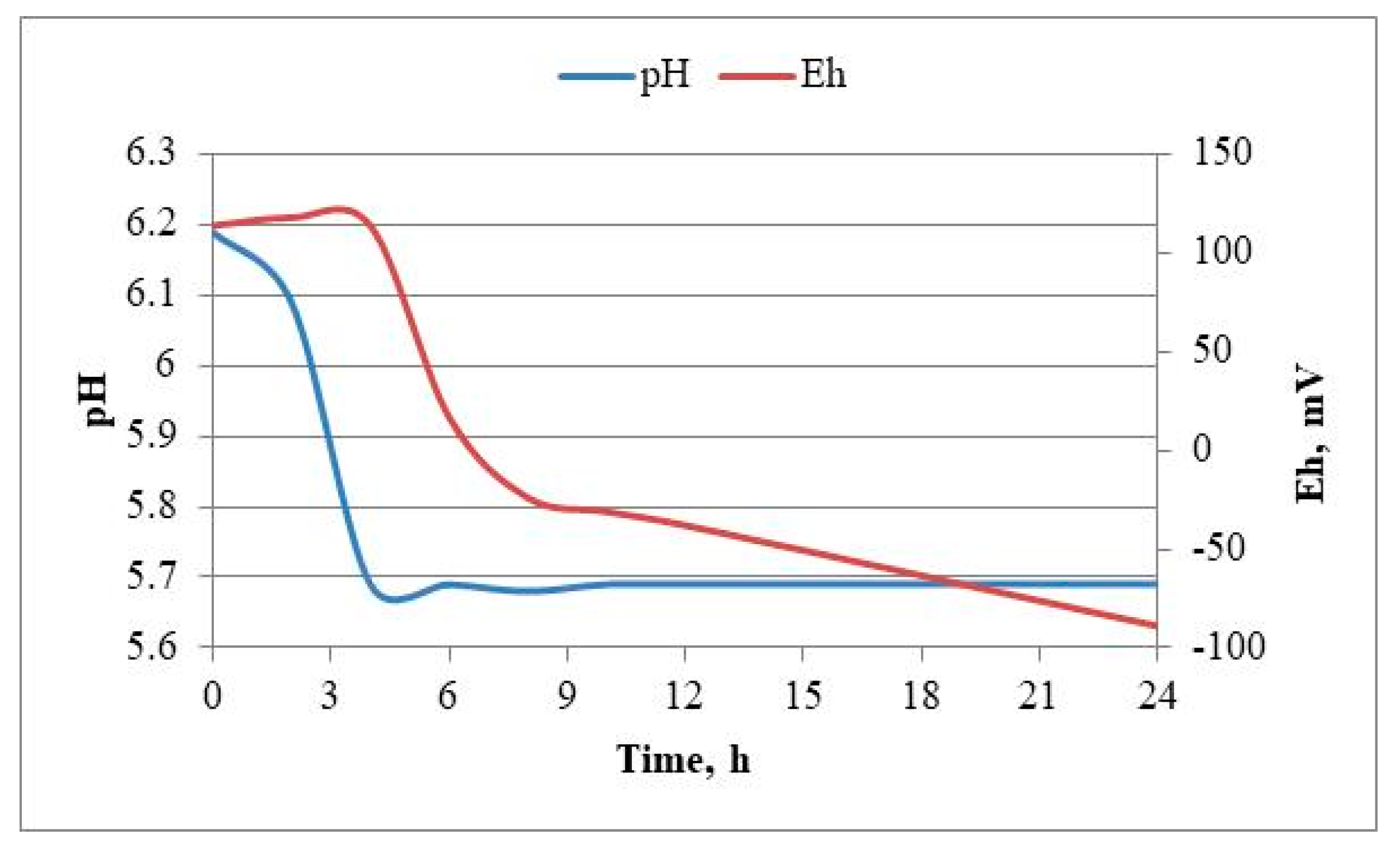

3.3. Batch Cultivation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 5/20 in a Laboratory Bioreactor with Continuous Stirring in MRS-Broth Medium. Determination of the Process Kinetics and Identification of Model Parameters

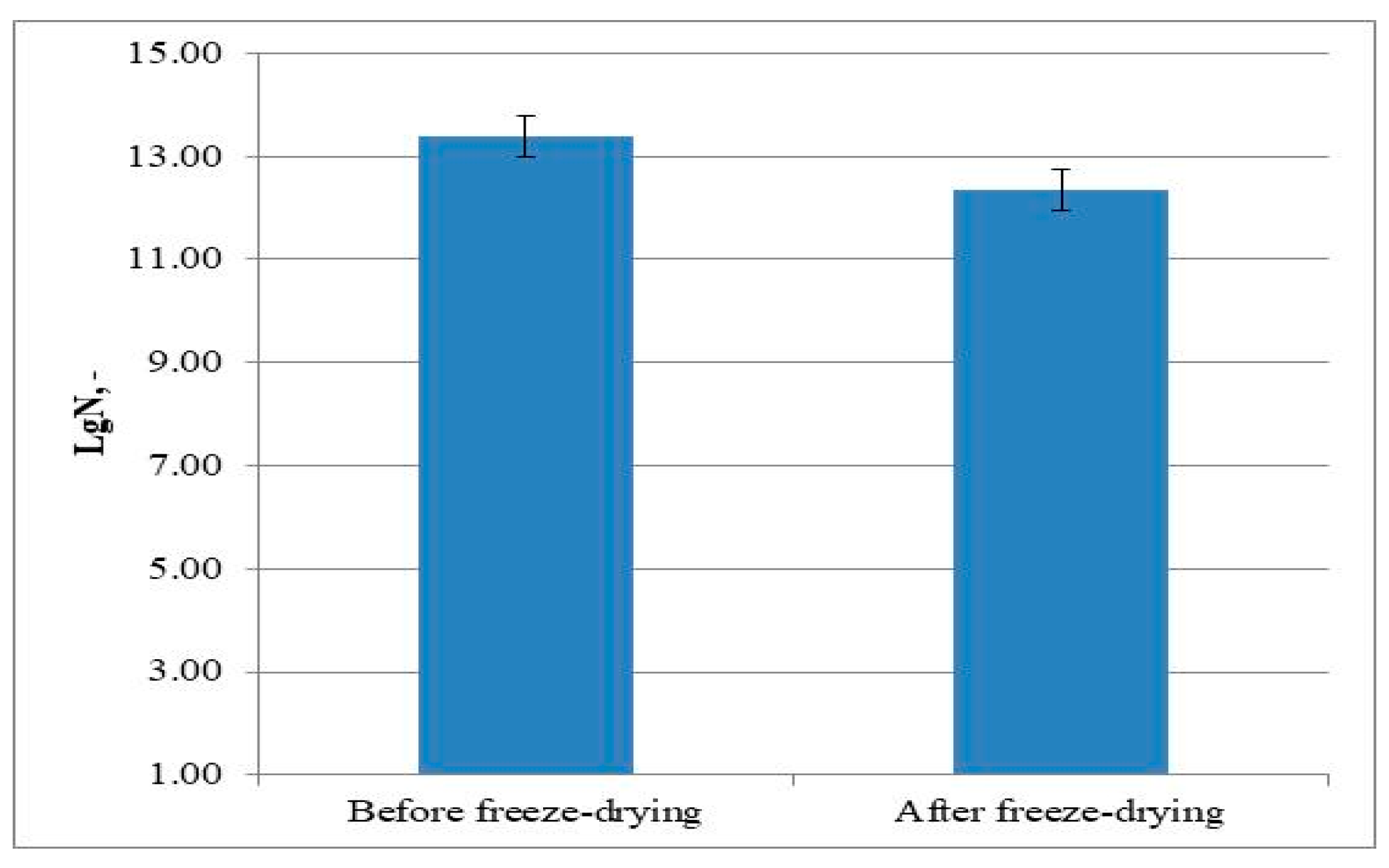

3.4. Freeze-Drying

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, A.O.; Leveau, J.H.; Marco, M.L. Abundance, diversity and plant-specific adaptations of plant-associated lactic acid bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Ayivi, R.D.; Zimmerman, T.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Altemimi, A.B.; Fidan, H.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Bakhshayesh, R.V. Lactic acid bacteria as antimicrobial agents: Food safety and microbial food spoilage prevention. Foods 2021, 10, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingga, R.; Astuti, R.; Bahtera, N.; Adibrata, S.; Nurjannah, N.; Ahsaniyah, S.; Irawati, I. Effect of additional probiotic in cattle feed on cattle's consumption and growth rate. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2022, 3, 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivsharan, U.; Bhitre, M. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacterial isolates. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2013, 4, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadirova, S.; Sinyavskiy, Y. Biotechnological approaches to the creation of new fermented dairy products. Eurasian J. Appl. Biotechnol. 2023, 4, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayu, H.; Irwanto, R.; Dalimunthe, N.; Lingga, R. Isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria from Channa sp. as potential probiotic. J. Pembelajaran Biol. Nukleus 2023, 9, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ar, I.; Laksmi, B.; Astawan, M.; Fujiyama, K.; Arief, I. Identification and probiotic characteristics of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Indonesian local beef. Asian J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 9, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkaningtyas, F.; Mariyatun, M.; Kamil, R.; Setyawan, R.; Hasan, P.; Wiryohanjoyo, D.; Rahayu, E. Sensory evaluation of yogurt-like set and yogurt-like drink produced by indigenous probiotic strains for market test. Indones. Food Nutr. Prog. 2018, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundir, R.K.; Rana, S.; Kashyap, N.; Kaur, A. Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from food samples: an in vitro study. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, C.; Xu, Q.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhou, S.; Luo, X. Bacterial diversity and lactic acid bacteria with high alcohol tolerance in the fermented grains of soy sauce aroma type baijiu in North China. Foods 2022, 11, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aritonang, S.; Roza, E.; Rossi, E.; Purwati, E.; Husmaini, H. Isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria from okara and evaluation of their potential as candidate probiotics. Pak. J. Nutr. 2017, 16, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test protocol. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2009, 15, 1. Available online: https://asm.org/protocols/kirby-bauer-disk-diffusion-susceptibility-test-pro (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, G.; Denkova, R.; Ivanova, P.; Denkova, I. Kinetics of batch fermentation in the cultivation of a probiotic strain of lactic acid bacteria. Acta Univ. Cibiniensis Ser. E Food Technol. 2015, 19, 61–72. Available online: https://saiapm.ulbsibiu.ro/cercetare/ACTA_E/AUCFT2015_19(1)_61-72.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Kostov, G.; Denkova, R.; Ivanova, P.; Denkova, I. Microbial growth of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus B1 in a complex nutrient medium (MRS-broth). ECMS Proc. 2022, pp. 135–142. Available online: https://www.scs-europe.net/dlib/2022/ecms2022acceptedpapers/0135_simo_ecms2022_0028.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Kostov, G.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Ivanova, P.; Denkova, I. New approach to modelling the kinetics of the fermentation process in cultivation of lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Eur. Conf. Model. Simul. 2018, 212–218. Available online: https://www.scs-europe.net/dlib/2018/2018-0212.htm (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Denkova, R.; Denkova, Z.; Yanakieva, V.; Georgieva, L. Highly active freeze-dried probiotic concentrates with long shelf life. Food Environ. Saf. 2013, 12, 225. Available online: https://fens.usv.ro/index.php/FENS/article/download/169/167 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) EN ISO 4833:2004. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—Horizontal method for the enumeration of microorganisms—Colony-count technique at 30 °C. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2004.

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) ISO 15214:2002. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—Horizontal method for the enumeration of mesophilic lactic acid bacteria—Colony-count technique at 30 degrees C. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2002.

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) EN ISO 4833-1:2013/A1:2022. Microbiology of the food chain—Horizontal method for the enumeration of microorganisms—Part 1: Colony count at 30 degrees C by the pour plate technique; Amendment 1; Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) ISO 16649-2:2014. Microbiology of the food chain—Horizontal method for the enumeration of β-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli—Part 2: Colony-count technique at 44 °C using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-glucuronide. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2014.

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) EN ISO 6579-1:2017/A1:2020. Microbiology of the food chain—Horizontal method for the detection, enumeration and serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp.; Amendment 1: Broader range of incubation temperatures and clarification of testing of samples with high background flora; Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) EN ISO 6888-1:2021/A1:2023. Microbiology of the food chain—Horizontal method for the enumeration of Staphylococcus aureus—Part 1: Technique using Baird-Parker agar medium; Amendment 1.; Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) ISO 15213:2023. Microbiology of the food chain—Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Clostridium spp.—Colony-count technique. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2023.

- Bulgarian State Standard (BDS) ISO 6611:2006. Milk and milk products—Enumeration of colony-forming units of yeasts and/or moulds—Colony-count technique at 25 degrees C. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2006.

- Majhenič, A.Č.; Lorbeg, P.M.; Treven, P. Enumeration and identification of mixed probiotic and lactic acid bacteria starter cultures. In Probiotic Dairy Products; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 207–251. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Goswami, P.; Singh, R.; Heller, K.J. Application of molecular methods for identification of lactic acid bacteria. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.L.; Kato, N.; Matsumiya, Y.; Liu, C.X.; Kato, H.; Watanabe, K. Identification of Lactobacillus species of human origin by a commercial kit, API50CHL. Rinsho Biseibutsu Jinsoku Shindan Kenkyukai Shi 1999, 10, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Charteris, W.P.; Kelly, P.M.; Morelli, L.; Collins, J.K. Development and application of an in vitro methodology to determine the transit tolerance of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species in the upper human gastrointestinal tract. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 84, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Singh, R. Antibiotic resistance in food lactic acid bacteria—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 105, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, F.; Cenard, S.; Passot, S. Freeze-drying of lactic acid bacteria. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1257, pp. 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, T.; Brankova, R. Viability of micrococci and lactobacilli upon freezing and freeze-drying in the presence of different cryoprotectants. Cryobiology 1983, 20, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montel Mendoza, G.; Pasteris, S.E.; Otero, M.C.; Nader-Macías, M.E.F. Survival and beneficial properties of lactic acid bacteria from raniculture subjected to freeze-drying and storage. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Cellular morphology | Colonial characteristics | ||

| Description | Visualization | Description | Visualization | |

| LAB 4/20 | Long, thickened rods with rounded ends, arranged singly, in pairs and in short chains |  |

snowflake-shaped colonies, serrated ends, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 5/20 | Fine, short rods with rounded ends, arranged in pairs and in short chains |  |

round colonies, with wavy ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 6/20 | Long, thin rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in long chains |  |

round colonies with wavy ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 8/20 | Long, thin rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in long chains |  |

round colonies with wavy ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 9/20 | Short, thickened rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in clusters |  |

round colonies with wavy ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 10/20 | Long rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in short chains |  |

snowflake-shaped colonies with wavy ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 12/20 | Long thin rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in short chains |  |

snowflake-shaped colonies with serrated ends, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 13/20 | Short thickened rods with rounded ends, arranged singly, in pairs and in clusters |  |

round colonies with even ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 16/20 | Cocci, arranged in pairs and in groups |  |

round colonies with even ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 19/20 | Very short rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in groups |  |

round colonies with even ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| LAB 22/20 | Short rods with rounded ends, arranged singly and in groups round, flat ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm |  |

round colonies with even ends, soft consistency, 2-3 mm in diameter |  |

| # | Carbohydrates | LAB 4/20 | LAB 5/20 | LAB 6/20 | LAB 8/20 | LAB 9/20 | LAB 10/20 |

| 1 | Glycerol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Erythriol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | D-arabinose | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | L-arabinose | - | + (90-100%) | - | - | - | + (90-100%) |

| 5 | Ribose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | - | + (90-100%) |

| 6 | D-xylose | - | - | - | - | - | + (90-100%) |

| 7 | L-xylose | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | Adonitol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | β -metil-D-xyloside | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | Galactose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 11 | D-glucose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 12 | D-fructose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 13 | D-mannose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 14 | L-sorbose | - | - | - | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 15 | Rhamnose | - | - | - | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 16 | Dulcitol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | Inositol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | Manitol | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) |

| 19 | Sorbitol | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) |

| 20 | α -methyl-D-mannoside | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | - | + (90-100%) |

| 21 | α -methyl-D-glucoside | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 22 | N-acetyl-glucosamine | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 23 | Amigdalin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 24 | Arbutin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 25 | Esculin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 26 | Salicin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 27 | Cellobiose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 28 | Maltose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 29 | Lactose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 30 | Melibiose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) |

| 31 | Saccharose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 32 | Trehalose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 33 | Inulin | - | - | + (90-100%) | - | - | - |

| 34 | Melezitose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) |

| 35 | D-raffinose | - | - | + (90-100%) | - | - | + (90-100%) |

| 36 | Amidon | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - |

| 37 | Glycogen | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 38 | Xylitol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 39 | β -gentiobiose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 40 | D-turanose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 41 | D-lyxose | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 42 | D-tagarose | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 43 | D-fuccose | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 44 | L-fuccose | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 45 | D-arabitol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 46 | L-arabitol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 47 | Gluconate | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | - | + (90-100%) |

| 48 | 2-keto-gluconate | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 49 | 5-keto-gluconate | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| # | Sugars | LAB 12/20 | LAB 13/20 | LAB 16/20 | LAB 19/20 | LAB 22/20 |

| 1 | Glycerol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Erythriol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | D-arabinose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | L-arabinose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 5 | Ribose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 6 | D-xylose | - | - | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 7 | L-xylose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | Adonitol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | β -metil-D-xyloside | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | Galactose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) |

| 11 | D-glucose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 12 | D-fructose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 13 | D-mannose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 14 | L-sorbose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15 | Rhamnose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16 | Dulcitol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | Inositol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | Manitol | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 19 | Sorbitol | - | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 20 | α -methyl-D-mannoside | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 21 | α -methyl-D-glucoside | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 22 | N-acetyl-glucosamine | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 23 | Amigdalin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 24 | Arbutin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 25 | Esculin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 26 | Salicin | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 27 | Cellobiose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 28 | Maltose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 29 | Lactose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 30 | Melibiose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 31 | Saccharose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 32 | Trehalose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 33 | Inulin | - | - | + (90-100%) | - | - |

| 34 | Melezitose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 35 | D-raffinose | - | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 36 | Amidon | + (90-100%) | - | - | - | - |

| 37 | Glycogen | - | - | - | - | - |

| 38 | Xylitol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 39 | β -gentiobiose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | - |

| 40 | D-turanose | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) | + (90-100%) |

| 41 | D-lyxose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 42 | D-tagarose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 43 | D-fuccose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 44 | L-fuccose | - | - | - | - | - |

| 45 | D-arabitol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 46 | L-arabitol | - | - | - | - | - |

| 47 | Gluconate | - | + (90-100%) | - | + (90-100%) | - |

| 48 | 2-keto-gluconate | - | - | - | - | - |

| 49 | 5-keto-gluconate | - | - | - | - | - |

| Strain | Species affiliation | Reliability, % |

| LAB 4/20 | Lactobacillus crispatus | 65.3 |

| LAB 5/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99.9 |

| LAB 6/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99.9 |

| LAB 8/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99,9 |

| LAB 9/20 | Lactobacillus crispatus | 65,3 |

| LAB 10/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99.9 |

| LAB 12/20 | Lactobacillus crispatus | 65.3 |

| LAB 13/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99.9 |

| LAB 16/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 94,1 |

| LAB 19/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99.9 |

| LAB 22/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99,9 |

| Strain | Species affiliation | Similarity, % |

| LAB 4/20 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 99% |

| LAB 5/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99% |

| LAB 6/20 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 99% |

| LAB 8/20 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 99% |

| LAB 9/20 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 99% |

| LAB 10/20 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | 99% |

| LAB 12/20 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 99% |

| LAB 13/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99% |

| LAB 16/20 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99% |

| LAB 19/20 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum | 99% |

| LAB 22/20 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99% |

| dIZ, [mm] |

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, 6x109cfu/cm3 |

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25093, 1,7x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Salmonella abony NTCC 6017, 2x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Proteus vulgaris J, 1,5x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115, 4x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, 4,2x1012 cfu/cm3 |

|

| LAB strain | |||||||

| 4/20 | CL | 12,67±0,47 | 17,17±0,24 | 14,67±0,47 | 15,50±0,41 | 17,00±0,00 | 16,67±0,47 |

| BSS | 11,17±0,24 | 20,17±0,24 | 9,67±0,47 | 12,33±0,47 | 14,17±0,24 | 13,33±0,47 | |

| CFSN | 10,50±0,41 | 10,17±0,24 | 10,17±0,24 | 12,00±0,00 | 15,17±0,24 | 11,33±0,47 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 6/20 | CL | 12,17±0,24 | 15,00±0,00 | 11,33±0,47 | 14,33±0,47 | 18,33±0,47 | 16,50±0,41 |

| BSS | 9,17±0,24 | 16,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | 9,17±0,24 | 14,00±0,00 | 13,17±0,24 | |

| CFSN | 10,17±0,24 | 13,67±0,47 | 9,50±0,41 | 12,00±0,00 | 15,67±0,47 | 13,00±0,00 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 8/20 | CL | 11,17±0,24 | 13,50±0,41 | 10,17±0,24 | 13,17±0,24 | 16,50±0,41 | 16,00±0,00 |

| BSS | 8,00±0,00 | 12,17±0,24 | 8,33±0,47 | 8,17±0,24 | 13,17±0,24 | 12,17±0,24 | |

| CFSN | 10,50±0,41 | 10,50±0,41 | 8,00±0,00 | 10,00±0,00 | 14,67±0,47 | 13,17±0,24 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 9/20 | CL | 11,50±0,41 | 16,00±0,00 | 11,67±0,47 | 12,50±0,41 | 18,67±0,47 | 18,67±0,47 |

| BSS | 8,00±0,00 | 10,17±0,24 | 8,17±0,24 | 9,00±0,00 | 12,17±0,24 | 15,00±0,00 | |

| CFSN | 10,00±0,00 | 10,67±0,47 | 9,50±0,41 | 10,00±0,00 | 15,17±0,24 | 14,00±0,00 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 12/20 | CL | 14,67±0,47 | 16,17±0,24 | 14,00±0,00 | 15,00±0,00 | 18,00±0,82 | 18,17±0,24 |

| BSS | 9,17±0,24 | 12,33±0,47 | 10,00±0,00 | 10,00±0,00 | 15,17±0,24 | 13,17±0,24 | |

| CFSN | 12,00±0,00 | 13,17±0,24 | 10,17±0,24 | 13,50±0,41 | 15,67±0,47 | 13,00±0,00 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | 8,00±0,00 |

| dIZ, [mm] |

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, 6x109cfu/cm3 |

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25093, 1,7x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Salmonella abony NTCC 6017, 2x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Proteus vulgaris J, 1,5x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115, 4x1012 cfu/cm3 |

Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, 4,2x1012 cfu/cm3 |

|

| LAB strain | |||||||

| 5/20 | CL | 13,67±0,47 | 19,67±0,47 | 13,33±0,47 | 17,00±0,00 | 20,00±0,00 | 18,50±0,41 |

| BSS | 9,17±0,24 | 17,33±0,47 | 9,17±0,24 | 10,00±0,00 | 16,17±0,24 | 14,67±0,47 | |

| CFSN | 11,17±0,24 | 14,67±0,47 | 11,33±0,47 | 13,17±0,24 | 17,67±0,47 | 13,50±0,41 | |

| NCFSN | 8,17±0,24 | - | - | - | 9,17±0,24 | - | |

| 13/20 | CL | 11,17±0,24 | 19,50±0,41 | 10,17±0,24 | 14,50±0,41 | 17,17±0,24 | 17,67±0,47 |

| BSS | 9,00±0,00 | 17,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | 10,17±0,24 | 15,00±0,00 | 14,17±0,24 | |

| CFSN | 10,50±0,41 | 13,00±0,00 | 9,00±0,00 | 13,17±0,24 | 15,17±0,24 | 13,00±0,00 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | 8,00±0,00 | - | |

| 19/20 | CL | 10,17±0,24 | 10,17±0,24 | 9,67±0,47 | 10,67±0,47 | 11,00±0,00 | 10,17±0,24 |

| BSS | 8,00±0,00 | 9,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | 8,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | 8,67±0,47 | |

| CFSN | 8,67±0,47 | 8,00±0,00 | 8,50±0,41 | 9,00±0,00 | 9,00±0,00 | 9,17±0,24 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 10/20 | CL | 10,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | 9,00±0,00 | 10,17±0,24 | 9,67±0,47 | 8,17±0,24 |

| BSS | 8,17±0,24 | 8,17±0,24 | 8,17±0,24 | 8,17±0,24 | 8,17±0,24 | 8,17±0,24 | |

| CFSN | 9,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | 9,00±0,00 | 9,17±0,24 | 9,17±0,24 | 8,00±0,00 | |

| NCFSN | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| # | Mechanism of action | Antibiotic | Concentration | 4/20 | 6/20 | 8/20 | 9/20 | 12/20 | |

| 1 | Inhibitor of cell wall synthesis | Penicillin | P | 10 E/disc | R | S | S | R | R |

| 2 | Bacitracin | Cm | 0,07 E/disc | R | S | S | SR | SR | |

| 3 | Piperacillin | P | 100 µg/disc | S | R | S | S | SR | |

| 4 | Ampicillin | A | 10 µg/disc | R | R | S | R | R | |

| 5 | Oxacillin | O | 1 µg/disc | R | S | R | R | R | |

| 6 | Amoxicillin | Ax | 25 µg/disc | S | S | S | R | SR | |

| 7 | Vancomycin | V | 30 µg/disc | R | S | S | R | R | |

| 8 | Inhibitor of protein synthesis | Tetracycline | T | 30 µg/disc | R | R | S | R | S |

| 9 | Doxycycline | D | 30 µg/disc | R | SR | SR | SR | S | |

| 10 | Gentamicin | G | 10 µg/disc | SR | R | S | SR | SR | |

| 11 | Tobramycin | Tb | 10 µg/disc | R | S | S | R | R | |

| 12 | Amikacin | Am | 30 µg/disc | R | R | SR | R | SR | |

| 13 | Lincomycin | L | 15 µg/disc | R | R | SR | R | SR | |

| 14 | Chloramphenicol | C | 30 µg/disc | S | SR | S | S | S | |

| 15 | Erythromycin | E | 15 µg/disc | SR | S | S | R | S | |

| 16 | Inhibitor of the DNA synthesis and/or of cell division | Novobiocin | Nb | 5 µg/disc | S | R | S | SR | R |

| 17 | Nalidixic acid | Nx | 30 µg/disc | R | R | SR | R | R | |

| 18 | Rifampin | R | 5 µg/disc | SR | S | S | SR | S | |

| 19 | Ciprofloxacin | Cp | 5 µg/disc | R | R | SR | SR | SR | |

| # | Mechanism of action | Antibiotic | Concentration | 5/20 | 13/20 | 19/20 | 10/20 | |

| 1 | Inhibitor of cell wall synthesis | Penicillin | P | 10 E/disc | R | R | R | R |

| 2 | Bacitracin | Cm | 0,07 E/disc | R | SR | SR | SR | |

| 3 | Piperacillin | P | 100 µg/disc | R | SR | S | S | |

| 4 | Ampicillin | A | 10 µg/disc | R | R | R | R | |

| 5 | Oxacillin | O | 1 µg/disc | R | R | R | R | |

| 6 | Amoxicillin | Ax | 25 µg/disc | S | SR | R | R | |

| 7 | Vancomycin | V | 30 µg/disc | R | R | R | R | |

| 8 | Inhibitor of protein synthesis | Tetracycline | T | 30 µg/disc | SR | S | R | R |

| 9 | Doxycycline | D | 30 µg/disc | S | S | SR | SR | |

| 10 | Gentamicin | G | 10 µg/disc | SR | SR | SR | SR | |

| 11 | Tobramycin | Tb | 10 µg/disc | R | R | R | R | |

| 12 | Amikacin | Am | 30 µg/disc | R | SR | R | R | |

| 13 | Lincomycin | L | 15 µg/disc | R | SR | R | R | |

| 14 | Chloramphenicol | C | 30 µg/disc | S | S | S | S | |

| 15 | Erythromycin | E | 15 µg/disc | R | S | R | R | |

| 16 | Inhibitor of the DNA synthesis and/or of cell division | Novobiocin | Nb | 5 µg/disc | SR | R | SR | SR |

| 17 | Nalidixic acid | Nx | 30 µg/disc | R | R | R | R | |

| 18 | Rifampin | R | 5 µg/disc | SR | S | SR | SR | |

| 19 | Ciprofloxacin | Cp | 5 µg/disc | R | SR | SR | SR | |

| Batch cultivation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 5/20 | ||||

| µ, h-1 | β, cm3/(CFU.h) | Xкр, LogN | R2 | Error |

| 0,130 | 0,0095 | 13,63 | 0,9995 | 0,778 |

| Type of pathogenic microorganisms tested | According to BDS | Analysis result |

| Total number of mesophilic aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria | No more than 800 | 180 |

| Escherichia coli in 0.l g of the product | Not to be detected any | Not detected |

| Sulphite-reducing clostridia in 0.l g of the product | Not to be detected any | Not detected |

| Salmonella sp. in 25.0 g of the product | Not to be detected any | Not detected |

| Coagulase-positive staphylococci in 1.0 g of the product | Not to be detected any | Not detected |

| Spores of microscopic molds, CFU/g | No more than 100 | Not detected |

| Yeasts, CFU/g | No more than 100 | Not detected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).