1. Introduction

Bacteriophages (phages) and bacteria have adapted to each other over billions of years [

1]. Their relationship is a specific example of host-parasite coexistence with many unique features [

2]; the continuous interaction between the phages and the bacteria led to the development of bacterial protection systems against the phages and the improvement of methods to overcome these systems by phages. This arms race is not the only form of interaction, as in many cases the acquired adaptation is costly, whether in terms of fitness or virulence. Therefore, other types of interactions emerged, for example, a win-win scenario where a phage can infect a bacterium, integrating its genome into the bacterial genome and helps it either with useful genes or by protecting it against other phages [

2].

Additionally, a temporal factor plays a role in the adaptation of phages and bacteria toward each other. Phages and bacteria may acquire mutations temporarily before abandoning them later in favor of mutations more suitable to contemporary counterparts, or because the mutations were disadvantageous in some aspects. This fluctuating selection of genotypes could be more maintainable over time, and would lead to the emergence of a wide variety of bacterial and phage descendants due to the continuous interactions [

3].

This review aims to summarize the studies conducted on phage-bacteria co-evolution, whether it was done under controlled settings

in vitro or

in vivo, or focused on testing samples collected regularly from ecosystems over long periods of time. More than thirty articles that were published over the past twenty years (

Table 1) were involved in the review and the factors that influenced the co-evolution of phages and bacteria were analyzed. Additionally, the main features of the dynamics of evolution and the limitations in the studies conducted were described. The review does not discuss the various mathematical models used to depict the dynamics of evolutions, which have been comprehensively described previously [

4].

2. Mutation Rate and Mutation Load

When describing the changes happening in co-evolving phages and bacteria, two concepts are important in order to understand the limitation and scope of their adaptation: mutation rate and mutation load. Mutation rate measures the number of mutations that arise in a population over time. It is typically estimated by adjusting the number of substitutions with samples found in dated fossils [

38] or with samples from different stages of measurably evolving population [

39]. This rate varies substantially among microorganisms, and as estimated by fluctuation experiments; it is ∼10

−10 mutations per nucleotide per replication for bacteria, from 10

−7 to 8 × 10

−7 mutations per nucleotide per replication for some dsDNA phages [

40], and 5 × 10

-3 mutations per genome per replication in the case of the phage M13 [

41].

The mutational load is the total genetic burden in population resulting from accumulated damaging mutations. During the population’s evolution, a number of damaging mutations may arise. Such mutations reduce the average fitness of members of this population and result in the elimination of some of them. This leads to selection against such damaging mutations and results in a balance between selection against the damaging gene and its production by mutagenesis. In the equilibrium, a dominant deleterious mutation has a frequency of

m/s, where

m is the mutation rate and

s is the selective disadvantage of the mutation. The mutational load can be calculated as equal to the mutation rate in the equilibrium state [

42].

3. Mechanisms of Phage-Bacteria Co-Evolution

Genomes’ evolution in both phages and bacteria involves the acquisition of genetic material through genetic recombination, which occurs at two different scales. At the micro-scale, recombination can alter several nucleotides in a single event. At the macro-scale, recombination can result in the acquisition or deletion of genes or their fragments, and this leads to gene content variations over time.

Phages can encode various proteins that facilitate recombination such as proteins of the Red recombination system [

43], recombinases, and transposases [

44]. Recombination between phages occurs mainly through coinfection, which has been shown to be widespread in bacterial populations [

45,

46,

47]. During coinfection, temperate phages may acquire DNA from defective prophages in the host genome by relaxed homologous recombination [

48], while lytic phages can recombine with other lytic phages or with prophages or remnants of prophages in the host genome [

49]. Footprints of genetic recombination have been found in phage genomes [

50,

51], and the high variability of gene content observed in natural phage populations indicates that gene gain and loss are relatively frequent [

52]. Nonetheless, their rates in the evolution of phage genomes are still unknown [

53].

Interacting with the phages, bacteria have developed a wide range of anti-phage defense mechanisms. Bacterial anti-phage mechanisms include restriction modification (RM) systems, abortive infection systems, protein sensing systems, toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems, prokaryotic argonauts, CRISPR-Cas, surface modification and others [

54,

55]. Some of these defense strategies do not allow the phage to infect the bacterium while preserving it intact. Thus, RosmerTA system encodes a toxin, which causes a depolarization of the bacterial membrane and doesn’t allow the phage to adsorb properly and inject its genome, and another protein, an antitoxin, that counter the effects of the toxin thus leaving the bacteria intact [

56]. Another system, the Hachiman system, produces two proteins, one of which checks the integrity of the bacterial genome, while inactivating a second protein. When the bacterial genome is damaged, for example, due to a phage infection, the second protein with the nuclease activity is activated, and all the genetic material inside the bacterial cell, whether bacterial or viral, is destroyed. Thus, the bacterium is damaged, protecting neighboring bacterial cells.

One of the most common ways used by bacteria to counter phage infections is modification of the outer membrane receptors used by the phage for adsorption.

E. coli, for example, is known to develop resistance due to mutations in the regulatory gene

malT that suppresses expression of the host receptor, the outer-membrane protein LamB [

34,

57,

58].

Phages, in turn, have adapted special mechanisms against the bacteria’s defenses. Phage λ counters the decrease in LamB expression in its host by evolving mutations in the binding domain of the host-recognition protein J, which allows it to use a new receptor, OmpF. However,

E. coli accumulates additional mutations in OmpF or in an inner-membrane protein complex, ManXYZ, that transports λ DNA into the cytoplasm to counter the viral infection in another mechanism [

34,

57,

58].

Sometimes, phages acquire mechanisms to counter the defense systems from their bacterial hosts. Thus,

Enterobacter cloacae phage EC151 encodes 7-deazaguanine modification pathway to counter the RM systems of its bacterial host[

59]. In addition, phages evolved counter-defenses against some TA systems deployed by bacteria. Some T4-like phages encode the protein TifA, which directly binds both the endoribonuclease ToxN (the toxin of the TA system type III toxin) and bacterial RNA, leading to the formation of a high molecular weight ribonucleoprotein complex in which ToxN is inhibited [

60]. So, the evolving of anti-phage systems in bacteria and counter-mechanisms in phages provide a mean, through which they change over time as a result of their prolonged interactions.

4. Co-evolutionary Dynamics

Bacteria-phage co-evolution is a classic example of host-parasite mutual adaptation. This adaptation follows a certain dynamic that may be classified into two main categories: arms race dynamics and fluctuating selection dynamics, also known as red queen dynamics. Other dynamics, namely leapfrog dynamics, kill the winner dynamics, piggy back the winner dynamics, and community shuffling dynamics, are described as well, although less studied.

4.1. Arms Race Dynamics

Arms race dynamics are driven by directional selection for increasingly resistant hosts and increasingly infectious parasites, novel mechanisms of phage infectivity or host resistance emerge and accumulate[

61,

62]. However, this accumulation of novel mechanisms is limited, not only by the consumption of resources, but also by the potential number of novel mutations, which can arise, and the impact of accumulating fitness costs. After several generations of co-evolution, a novel mechanism may become fixed due to recurrent selective sweeps. Subsequently, fluctuating selection dynamics can emerge. This shift allows for the maintenance of genetic diversity as varying selective pressures enable multiple alleles to coexist rather than remaining fixed.

Arms race dynamics are directional, which means that each novel mutation providing further phage infectivity or bacterial resistance to phages is added to the previous background, and resistance or infectivity ranges increase as co-existence continues. In this case, a hierarchical structure within the population exists, where each genotype is a subset of a more generalist genotype, which is one step further down the co-evolutionary race [

63]. In general, the resulting adapted host population is less diverse with lower levels of sustained genetic variability [

64], unless the cost of resistance is high enough for phage-susceptible bacteria retain to a fitness advantage.

4.2. Fluctuating Selection Dynamics

Fluctuating selection dynamics are long term co-evolutionary dynamics, often associated with alterations of genotype abundances driven by fluctuating selection in host-parasite systems [

3]. The dynamics are driven by negative frequency-dependent selection, whereby common host genotypes are targeted by phage infection and selected against, leading to the increased frequency of rarer host genotypes, which eventually become the most common, and then the cycle repeats [

61].

Long term fluctuating selection dynamics promote diversity within populations, and since only the most abundant bacteria are targeted, multiple genotypes can co-exist. If each bacterial clone independently co-evolves against specialized phages, each interaction would have its own evolutionary trajectory potentially forming their own hierarchy of genotypes as they diversify [

63]. The increased host diversity supports a broader genetic polymorphism of resistance phenotypes, which, in turn, can protect the population upon encountering new phage genotypes [

63].

It is suggested that if phages adapt more rapidly than their hosts, fluctuating selection dynamics are on average expected to result in phages better adapted to their contemporary hosts compared with past and future ones, and vice versa if hosts adapt faster than phages [

65].

4.3. Leapfrog Dynamics

Leapfrog dynamics are hybrid dynamics that were suggested following the contradiction between genotypic and phenotypic features of bacteria and phages resulting from co-incubation experiments [

34]. The dynamics suggest that parasite genotypes with ever-expanding host ranges are selected, and hosts with ever-increasing resistance are favored, like in the arms race dynamics. However, the diversity of hosts and parasites that appeared early in the co-evolution process is maintained, allowing for the emergence of rare individuals with advantageous phenotypes from this pool to replace whatever the dominant strains are. Thus, while genotypic pattern points to fluctuating selection dynamics, the selection at the phenotypic level operates similarly to the arms race dynamics model [

34].

4.4. Kill the Winner Dynamics

These dynamics indicate that phages and bacteria manage to coexist and maintain ecosystems with a high diversity of strains, despite limited resources and an abundance of infections. Virulent phages predominantly propagate in fast-growing bacteria and thereby suppress the competitive exclusion of slower-growing bacteria. Phages capable of infecting multiple hosts play an important role both in the evolution of the ecosystem, by eliminating the dominant bacterial strains, and in maintaining diversity by allowing slow growers to coexist with faster growers [

66].

4.5. Piggy Back the Winner Dynamics

These dynamics indicate that the lysogenic lifestyle of phages prevails in environments with high microbial abundance and growth rates. Switching to the temperate life cycle reduces the level of phage control on bacterial abundance and ensures the exclusion of superinfection, preventing infection of the same bacterial cells by closely related phages; so, microbial diversity decreases [

67].

4.6. Community Shuffling Dynamics

Prophages can be detrimental to their bacterial hosts, since their induction results in host lysis. Even though spontaneous induction is a rare event with negligible negative consequence on lysogen fitness, various environmental factors can change induction from a rare and stochastic event to a deterministic process. In the oceans, prophages have been compared to molecular time bombs, which can be activated by changes in salinity or various pollutants [

68].

5. Factors Affecting the Outcomes of Co-Evolution Experiments

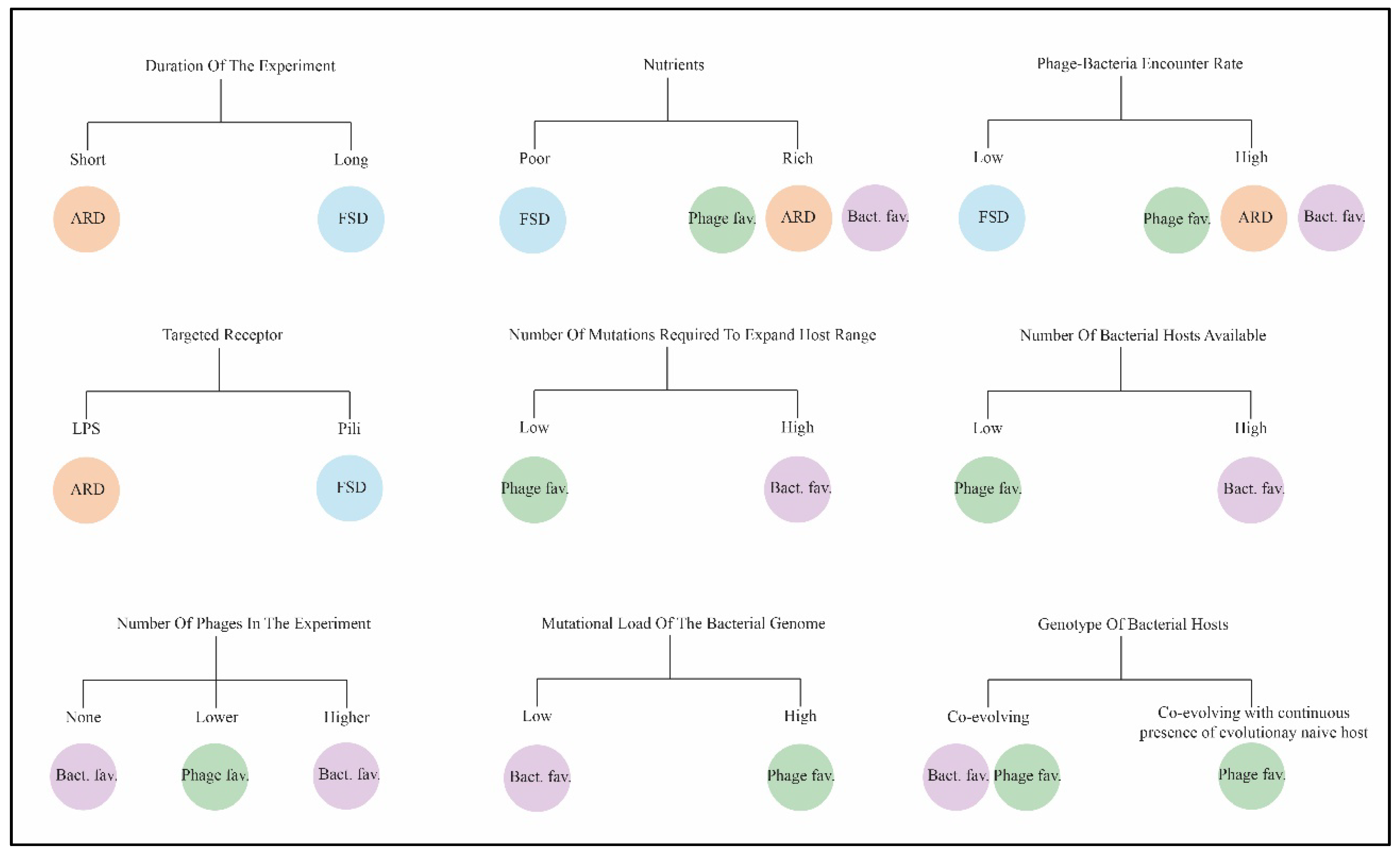

Analyses of the studies covered in this review revealed a number of factors that can affect co-evolution outcomes (

Figure 1).

5.1. Duration of the Experiment

Short experiments on the bacteria-phage co-evolution often result in the arms race dynamics and selection of generalist phages and bacteria, which are usually weaker than their ancestral strains. Co-evolving bacteria and phages select for generalist bacteria with wider resistance toward the phage infecting them and generalist phages with wider infectivity ranges; the cost of resistance increases over time spent on co-evolution. This pattern has been described in experiments with the co-evolving

Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 and SBW25F2 phage [

69].

Over longer periods of time, the cost of resistance increases and shifts the dynamics of selection from the arms race dynamics to fluctuating selection dynamics, as can be seen from the study conducted over sixty rounds in the same

P. fluorescens SBW25-phage SBW25F2 system[

14]. In another study of bacteria-phage communities in leaves of horse chestnuts tree, phages were collected monthly from eight trees for six months and the phages were found to be most infectious to contemporary bacterial hosts or those from recent past compared to bacteria from the past. Notably, phages collected at the end of the season were somewhat less infectious to bacterial hosts than much earlier in the season. This pattern suggests the fluctuating selection dynamics rather than the arms race dynamics [

17].

5.2. Preexisting Ability of Phages to Adapt to New Hosts and Bacteria Mutational Load

The phage’s preexisting readiness to adapt to non-target bacterial strains that are present in the experiment, is related to the number of point mutations required for the phage to become able to infect new hosts [

20,

69]. The expansion of the host range of a phage may require predisposition to adapt to the bacterial strains present, like acquiring a single point mutation in order to become able to infect them. Such an example was shown during incubation of the

Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola phage F6 with three non-permissive

Pseudomonas strains and its host strain. The experiment resulted in new generalists phages after 20 passages capable of infecting previously non-permissive strains [

18].

The mutational load of bacteria plays a role in determining their ability to adapt to contemporary phages; if bacteria have high mutational loads and reduced fitness, they are less able to adapt to the phages. This was shown when bacteria

P. fluorescens SBW25, whose mutagenesis was induced by UV before the experiment, and bacteria with accumulated mutations were compared with un-mutagenized bacteria. As a result, mutagenized bacteria were more able to adapt to the phages [

10].

5.3. The Bacterial Receptors Targeted by the Phage

When studying the co-evolution of six different phages and their host

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, the dynamics depended on the phages, with some of them becoming more infectious and some less infectious [

20,

69]. The co-evolutionary dynamics were associated with the nature of the receptor used by the phage for infection. In the experiment, some phages used bacterial pili as their receptors, whereas some phages targeted lipopolysaccharides (LPS). When developing resistance to phages, the bacteria of the first type could decrease the number of pili on its surface, and this sparsity of pili reduced the adsorption of pili-dependent phages. This loss of pili had fitness cost for the bacteria, because it impaired bacteria swimming ability making this adaptation undesirable. This can be prevented over evolutionary time, which facilitates the fluctuating selection dynamics. So, the phages that targeted the pili induced the fluctuating selection dynamics, while the phages that bound to LPS contributed to the arms race dynamics [

20].

Another study of the same bacterial strain with other phages showed similar results [

26]. Co-evolving the

P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain with two specific phages, phage 14-1, which targets LPS receptors, and phage LUZ19 binding the pili, led to phage receptors-dependent results.

P. aeruginosa PAO1-phage 14-1 co-evolutionary system had arms race dynamics features and showed local adaptation with the emergence of a number of mutations in the

wzy gene associated with the LPS receptor, whereas

P. aeruginosa PAO1-phage LUZ19 system had fluctuating selection dynamics features, with the presence of partial deletions of the

pilF gene, which is associated with type IV pili [

26].

5.4. The Presence of Additional Phages Specific to the Same Bacterial Host

The presence of additional phages in the experiment can be an evolutionary stress factor for the phage, negatively affecting its ability to adapt to its co-evolving host, or may present an opportunity for genetic exchange inside the common host by homologous or non-homologous recombination. The use of several different phages that are able to infect a single bacterial strain led to more rapid appearance of bacterial clones resistant to these phages, if the combined lytic effect of the diverse phages used was synergistic [

28]. For example, infection of the

P. aeruginosa strain with five phages simultaneously (PEV2, LUZ19, LUZ7, 14-1, and LMA2) that targeted various cell surface receptors (LPS, Ton-B-dependent receptors or type IV pili) led to a shift from the fluctuating selection dynamics to the arms race dynamics. This fact was explained by the diversity of the phage community, accelerating the host evolution, as they enhanced the selection of resistant hosts [

28].

5.5. Increased Host Diversity Slows down the Phage Adaptation Rate

Although it is sometimes possible to expand the host range of a phage by including new non-permissive bacterial strains in a co-evolutionary phage-bacterium combination, this can lead to costs associated with the rate of adaptation to such new hosts. When adapting the

E. coli phage øJB01 to infect a number of non-permissive strains, an increase in the number and diversity of strains in the experiment slowed down this process [

29]. When comparing co-evolving of the phage øJB01 to infect two previously non-permissive strains versus three non-permissive strains, the former phage showed better fitness, while the phage adapted in the three-hosts system was under higher selection pressure to stay able to infect the three hosts. Other experiments on host range-expansion with a two-host experimental system have shown that the evolution of generalist or specialist phages depended on the ratios of the two hosts and the strength of trade-offs between the fitness on each host [

29].

5.6. The Continuous Presence of Phages and/or Evolutionary Naïve Host

Experiments on phage host range expansion showed that the presence of evolutionary naïve (ancestral) host is important for the phage to keep propagating and exploring various mutations effects on its adaptability [

29]. In the system containing

P. fluorescens SBW25 and phage SBW25F2, when the phage and its bacterial host were co-evolved over 24 days, the phages adapted more quickly than those evolved with a constant bacterial genotype (such as an evolutionary naïve host); most of the mutations observed were found in genes related to the infection of the host [

13]. Comparing the same

P. fluorescens SBW25-phage SBW25F2 over twelve days in multiple scenarios (co-evolution, evolving only with evolutionary naïve bacteria, or rotating between those two options) showed that in general, the phages enhanced their infectivity ranges on the expense of their growth rate. Some notable exceptions were found in the rotating scenario, which led to the emergence of phages with higher infectivity rate and no decline in growth rate [

32].

The absence of phages that induced resistance in bacteria can redirect bacterial resources to other directions and restore sensitivity toward the phage [

63]. It has been shown that different

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 clones that gained resistance to five different

Pseudomonas phages acquired different mutations to restore the sensitivity in the absence of these phages [

70]. However, no relationship was found between the initial fitness costs and the evolution of phage sensitivity [

70]. Similar results on the gradual restoration of sensitivity in

Prochlorococcus strains to five T7-like phages have been reported [

23]. In contrast, another study described no restoration of phage sensitivity in cases of T6-resistant

E.coli even after 45,000 generations. [

71]

5.7. Growth Conditions

In high resources environment, increasing nutrient availability resulted in a shift from the fluctuating selection dynamics, with fluctuations in average infectivity and resistance ranges over time, to the arms race dynamics as it was shown in the experiment using

P. fluorescens SBW25 - phage SBW25F2 system over twelve days [

21]. Additionally, an experiment with

Salmonella enterica and the phage vB_Sen_STGO-35-1 in a rich media done over 21 days showed a fast emergence of resistance in the bacteria against the phage in day one. However, a subpopulation of bacteria persisted that allowed the phage to be maintained over time in the experiment, although with a multiple folds decrease in its titer [

35]. An experiment conducted on the

P. fluorescens SBW25 - phage SBW25F2 system for 21 days in poor media with tube shaking showed that such conditions led to complete phage extinction [

24].

In nutrient rich media, shaking the tubes containing a bacteria-phage system can double the rate of co-evolution due to increased chances of encounter between more infectious phages and bacteria, this results in more broadly resistant bacteria and more broadly infectious phages, thus selecting for generalists [

69]. This fact was also in line with a shift in the evolutionary dynamics from the fluctuating selection to arms race dynamics [

22].

Most of the described experiments so far were done

in vitro. However, a comparison of isolated

P. aeruginosa phages 14–1 and PNM from

in vivo setting (after being administered for therapy) and a parallel

in vitro experiment conducted during the same period showed that evolutionary dynamics were similar

in vivo and

in vitro, with high levels of resistance evolving quickly with limited evidence of phage evolution. Resistant bacteria, which evolved

in vitro and

in vivo, had decreased virulence.

In vivo, this was associated with lower growth rates of resistant isolates, whereas

in vitro, phage-resistant isolates showed greater biofilm formation[

33]. Finally, modification of the growth conditions by adding a seed bank in the form of endospores, allowed the bacterial species that were targeted by the phages to maintain phenotypic diversity that would otherwise be lost in the selection [

37].

6. Limitations of the Studies

Our current understanding of the fluctuating selection dynamics and the arms race dynamics is mainly based on theoretical concepts explored in mathematical models that mostly assume an infinite population size, and do not take into account environmental interactions that may change population sizes [

3]. On the experimental level, most of these studies are limited to

P. aeruginosa-phages and

P. fluorescens-phages systems; several studies used

E. coli phages. Phages infecting other bacteria from the ESKAPE group were not studied in such systems.

The durations and resolution of most studies varied significantly, and most of them were conducted for less than 30 days in laboratory settings with daily isolation of phages and bacteria. Longer duration studies mostly relied on collecting samples, either from an environment (horse chestnut trees) over several months or years , or from clinical samples from various patients over several decades [

31]. The lack of long-term experiments under controlled laboratory conditions makes it difficult to study the possibility of the appearance of phages with a rare phenotype or the accumulation of mutations to a threshold, after which bacterial hosts exhaust their ability to adapt to phages. When such studies are carried out, it would give us better understanding on the possible results of using phages in the treatment of chronic infections.

Testing the established evolutionary dynamics reveals their shortcomings, which make it difficult to predict the outcome of the phenotypic features. Arms race dynamics make simplifying assumptions about the genetics base of host range expansion and resistance, supposing that new mutations will have synergetic and accumulating effects to the ones that happened before them [

72]. Thus, arms race dynamics suggest that phages with a wide host range will expand their host range faster than phages with a narrow host range, and for bacteria, that strains with highest resistance will continue to develop resistance to phages better or faster than other strains. Experimental evidence, however, contradicts this type of genetic architecture that favors the evolution of directed phylogenies with one dominant branch. For example, mutations of the phage

λ J protein are known to depend on the presence of mutations in one or more other genes and are non-additive [

73,

74]. This may allow the emergence of rare phage clones with certain combinations of mutations if new random mutations have synergistic interaction with pre-existing ones [

75]. This non-additivity of mutations was also demonstrated experimentally in

E. coli when studying the interactions between two mutations,

malT− and ∆777, which appeared during incubation with phage

λ [

34].

Another limitation of evolutionary dynamics is the assumption that mutations have small effects. Meanwhile, mutations like the

E. coli’s

malT- can cause nearly complete resistance to some

λ phages, making them large-effect mutations that would allow the strains, in which they appear, to dominate compared to others [

34]. The dynamics described also do not consider recombination that can happen to a phage and cause sudden increases in its fitness, and thereby contribute to the rare clones of the phage to become the dominant ones [

30].

7. Evolutionary Consequences of Phage-Bacteria Co-evolution and their Importance for Phage Therapy:

7.1. Impact on the Phage Host Range

Evolved phages can acquire an extended host range to the initially non-permissive strains used in the experiment, but not to strains of the same bacterial species that were not part of the experiment. Phage SBW25F2 was co-evolved with its host

P. fluorescens SBW25 and it was shown that although all co-evolved phages had a wider host range than the ancestral phage and could differentially infect co-evolved variants of

P. fluorescens SBW25, none could infect any of the other 150 alternative

P. fluorescens strains, to which the phage SBW25F2 was not adapted [

19]. This result indicated fundamental genetic constraints on the adaptation of this phage. In new phage clones with the extended host range, mutations were found in the tail fiber gene; however, this was not enough for the phages to infect other

P. fluorescens strains [

19]. The importance of this result is that it counters the suggestion that phages with wide host ranges may be genetically predisposed to infect hosts that they have never encountered[

19].

The experimental co-evolution of cyanobacteria and a specific phage resulted in phages capable of infecting an initially resistant strain, which was genetically different from the cyanobacteria the phage co-evolved with. However, this resistant strain was experimentally obtained from a strain that was originally sensitive to the phage; hence, co-evolution did not in fact result in an increase in the number of strains that could be infected [

15].

Importantly, the co-evolved phages didn't expand their host range at all in some other studies[

19]. Bacteria–phage antagonistic co-evolution, while common in natural populations, has little effect on host range shifts, unless there is a pre-existing host–parasite genetic compatibility and/or the absence of secondary defense mechanisms to counter phage replication within the host[

19]. Moreover, in the absence of some initial bacteria–phage compatibility, spontaneous mutation alone is unlikely to lead to phage infection, and horizontal gene transfer may be required[

19]. This was shown in a study, in which phage JB01, its host strain

E. coli O127, and three non-permissive

E. coli strains co-evolved together, and the phage adapted to those previously non-permissive hosts[

29]. However, these three

E. coli strains were not chosen randomly, they were selected based on data that the studied phage requires a single point mutation to infect the strains.

Several reasons can be suggested to explain why co-evolved phages were unable to infect all new strains. (a) Lack of appropriate phage receptors on non-permissive strains. (b) Lack of mechanisms for producing new virions after the phage genomic material was injected in the bacteria in the resistant strains in some cases (electroporation did not help to obtain phage particles) [

20]. (c) Resistant bacteria probably possess some mechanisms such as RM systems, CRISPR and superinfection exclusion, or other anti-phage defense mechanisms[

76].

7.2. Impact on the Bacterial Suppression

Co-evolving phages with bacteria led to trained phages that postpone the emergence of phage-resistance in bacteria. Phage λ that co-evolved with

E. coli B strain REL606 for 30 days was then compared with the ancestral phage λ. The trained phage developed the ability to bind to two bacterial receptors instead of one, as in the ancestral phage [

30]. This significantly delayed the emergence of resistant bacteria; resistant bacteria emerged after 15 or more days when incubated with the adapted phage instead of 3 days when incubated with the ancestral phage [

30].

8. Conclusions

Many factors shape the interaction dynamics between bacteria and phages (

Figure 2), and while these factors could possibly be used to create diverse bacterial communities and adapt phages to them, more studies with a broader set of phages are required. For phage therapy, several factors should be taken into account, including ones that are rarely studied: the average treatment period for bacterial infections, competition and synergy between phages in the cocktail and microbiota co-evolution occurring

in vivo. Studying these factors could pave the way for a more effective procedure of creating adapted phage clones in phage banks and reduce the time needed for finding suitable phages for treatment of patients.

Understanding phage-bacteria co-evolution is important for two main reasons. First, it would be useful for choosing the phage preparation and the way of its administration, as well as in predicting the outcomes of phage application. Second, it would help in preparing phages for various bacterial clones that may arise during phage therapy by conducting simulation therapy in the laboratory and adapting the phage to co-evolving bacterial clones. Phage-bacteria co-evolution experiments have shown an expansion of the host range in some cases, although this may lead to a decrease in the fitness and infectivity of phages. Phage-bacteria coexistence is a complex multifactorial process that depends on a certain phage and a specific bacterium. Probably, the use of machine learning and the wealth of sequencing data following interactions between phages and bacteria can improve the dynamics models and enhance their predictivity, which is required for the successful application of phages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.J.; writing—review and editing, G.J, B.K and N.T..; visualization, G.J and B.K.; supervision, N.T.; project administration, N.T..; funding acquisition, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the by the Russian state-funded project for ICBFM SB RAS (grant number 122110700002-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Strathdee, S.A.; Hatfull, G.F.; Mutalik, V.K.; Schooley, R.T. Phage Therapy: From Biological Mechanisms to Future Directions. Cell 2023, 186, 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Naureen, Z.; Dautaj, A.; Anpilogov, K.; Camilleri, G.; Dhuli, K.; Tanzi, B.; Maltese, P.E.; Cristofoli, F.; De Antoni, L.; Beccari, T.; et al. Bacteriophages Presence in Nature and Their Role in the Natural Selection of Bacterial Populations. Acta Biomed 2020, 91, e2020024. [CrossRef]

- Schenk, H.; Schulenburg, H.; Traulsen, A. How Long Do Red Queen Dynamics Survive under Genetic Drift? A Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary and Eco-Evolutionary Models. BMC Evol Biol 2020, 20, 8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, C.; Zu, J. Coevolutionary Dynamics of Host-Pathogen Interaction with Density-Dependent Mortality. J. Math. Biol. 2022, 85, 15. [CrossRef]

- Buckling, A.; Rainey, P.B.. Antagonistic Coevolution between a Bacterium and a Bacteriophage. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2002, 269, 931–936. [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Morgan, A.D.; Rainey, P.B.; Buckling, A. Population Mixing Accelerates Coevolution. Ecology Letters 2003, 6, 975–979. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D.; Buckling, A. Parasites Mediate the Relationship between Host Diversity and Disturbance Frequency. Ecology Letters 2004, 7, 1029–1034. [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Rainey, P.B.; Buckling, A. The Effect of Spatial Heterogeneity and Parasites on the Evolution of Host Diversity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 271, 107–111. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D.; Gandon, S.; Buckling, A. The Effect of Migration on Local Adaptation in a Coevolving Host–Parasite System. Nature 2005, 437, 253–256. [CrossRef]

- Buckling, A.; Wei, Y.; Massey, R.C.; Brockhurst, M.A.; Hochberg, M.E. Antagonistic Coevolution with Parasites Increases the Cost of Host Deleterious Mutations. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2006, 273, 45–49. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D.; Buckling, A. Relative Number of Generations of Hosts and Parasites Does Not Influence Parasite Local Adaptation in Coevolving Populations of Bacteria and Phages. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2006, 19, 1956–1963. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D.; Brockhurst, M.A.; Lopez-Pascua, L.D.; Pal, C.; Buckling, A. Differential Impact of Simultaneous Migration on Coevolving Hosts and Parasites. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2007, 7, 1. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Vogwill, T.; Buckling, A.; Benmayor, R.; Spiers, A.J.; Thomson, N.R.; Quail, M.; Smith, F.; Walker, D.; Libberton, B.; et al. Antagonistic Coevolution Accelerates Molecular Evolution. Nature 2010, 464, 275–278. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.R.; Scanlan, P.D.; Morgan, A.D.; Buckling, A. Host-Parasite Coevolutionary Arms Races Give Way to Fluctuating Selection: Bacteria-Phage Coevolutionary Dynamics. Ecology Letters 2011, 14, 635–642. [CrossRef]

- Marston, M.F.; Pierciey, F.J.; Shepard, A.; Gearin, G.; Qi, J.; Yandava, C.; Schuster, S.C.; Henn, M.R.; Martiny, J.B.H. Rapid Diversification of Coevolving Marine Synechococcus and a Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 4544–4549. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.R.; Dobias, D.T.; Weitz, J.S.; Barrick, J.E.; Quick, R.T.; Lenski, R.E. Repeatability and Contingency in the Evolution of a Key Innovation in Phage Lambda. Science 2012, 335, 428–432. [CrossRef]

- Koskella, B. Phage-Mediated Selection on Microbiota of a Long-Lived Host. Current Biology 2013, 23, 1256–1260. [CrossRef]

- Bono, L.M.; Gensel, C.L.; Pfennig, D.W.; Burch, C.L. Competition and the Origins of Novelty: Experimental Evolution of Niche-Width Expansion in a Virus. Biology Letters 2013, 9, 20120616. [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, P.D.; Hall, A.R.; Burlinson, P.; Preston, G.; Buckling, A. No Effect of Host-Parasite Co-Evolution on Host Range Expansion. J Evol Biol 2013, 26, 205–209. [CrossRef]

- Betts, A.; Kaltz, O.; Hochberg, M.E. Contrasted Coevolutionary Dynamics between a Bacterial Pathogen and Its Bacteriophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 11109–11114. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Pascua, L.; Hall, A.R.; Best, A.; Morgan, A.D.; Boots, M.; Buckling, A. Higher Resources Decrease Fluctuating Selection during Host–Parasite Coevolution. Ecology Letters 2014, 17, 1380–1388. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P.; Ashby, B.; Buckling, A. Population Mixing Promotes Arms Race Host–Parasite Coevolution. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2015, 282, 20142297. [CrossRef]

- Avrani, S.; Lindell, D. Convergent Evolution toward an Improved Growth Rate and a Reduced Resistance Range in Prochlorococcus Strains Resistant to Phage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, E2191–E2200. [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.C.T.; Brockhurst, M.A.; Harrison, E. Ecological Conditions Determine Extinction Risk in Co-Evolving Bacteria-Phage Populations. BMC Evol Biol 2016, 16, 227. [CrossRef]

- Betts, A.; Gifford, D.R.; MacLean, R.C.; King, K.C. Parasite Diversity Drives Rapid Host Dynamics and Evolution of Resistance in a Bacteria-Phage System. Evolution 2016, 70, 969–978. [CrossRef]

- Gurney, J.; Aldakak, L.; Betts, A.; Gougat-Barbera, C.; Poisot, T.; Kaltz, O.; Hochberg, M.E. Network Structure and Local Adaptation in Co-Evolving Bacteria–Phage Interactions. Molecular Ecology 2017, 26, 1764–1777. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Lindell, D. Genetic Hurdles Limit the Arms Race between Prochlorococcus and the T7-like Podoviruses Infecting Them. ISME J 2017, 11, 1836–1851. [CrossRef]

- Betts, A.; Gray, C.; Zelek, M.; MacLean, R.C.; King, K.C. High Parasite Diversity Accelerates Host Adaptation and Diversification. Science 2018, 360, 907–911. [CrossRef]

- Sant, D.G.; Woods, L.C.; Barr, J.J.; McDonald, M.J. Host Diversity Slows Bacteriophage Adaptation by Selecting Generalists over Specialists. Nat Ecol Evol 2021, 5, 350–359. [CrossRef]

- Borin, J.M.; Avrani, S.; Barrick, J.E.; Petrie, K.L.; Meyer, J.R. Coevolutionary Phage Training Leads to Greater Bacterial Suppression and Delays the Evolution of Phage Resistance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- LeGault, K.N.; Hays, S.G.; Angermeyer, A.; McKitterick, A.C.; Johura, F.-T.; Sultana, M.; Ahmed, T.; Alam, M.; Seed, K.D. Temporal Shifts in Antibiotic Resistance Elements Govern Phage-Pathogen Conflicts. Science 2021, 373, eabg2166. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chu, X.; Buckling, A. Overcoming the Growth–Infectivity Trade-off in a Bacteriophage Slows Bacterial Resistance Evolution. Evolutionary Applications 2021, 14, 2055–2063. [CrossRef]

- Castledine, M.; Padfield, D.; Sierocinski, P.; Soria Pascual, J.; Hughes, A.; Mäkinen, L.; Friman, V.-P.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Merabishvili, M.; De Vos, D.; et al. Parallel Evolution of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Phage Resistance and Virulence Loss in Response to Phage Treatment in Vivo and in Vitro. eLife 2022, 11, e73679. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Peng, S.; Leung, C.Y.; Borin, J.M.; Medina, S.J.; Weitz, J.S.; Meyer, J.R. Leapfrog Dynamics in Phage-Bacteria Coevolution Revealed by Joint Analysis of Cross-Infection Phenotypes and Whole Genome Sequencing. Ecology Letters 2022, 25, 876–888. [CrossRef]

- Barron-Montenegro, R.; Rivera, D.; Serrano, M.J.; García, R.; Álvarez, D.M.; Benavides, J.; Arredondo, F.; Álvarez, F.P.; Bastías, R.; Ruiz, S.; et al. Long-Term Interactions of Salmonella Enteritidis With a Lytic Phage for 21 Days in High Nutrients Media. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 897171. [CrossRef]

- Dewald-Wang, E.A.; Parr, N.; Tiley, K.; Lee, A.; Koskella, B. Multiyear Time-Shift Study of Bacteria and Phage Dynamics in the Phyllosphere. Am Nat 2022, 199, 126–140. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Shoemaker, W.R.; Măgălie, A.; Weitz, J.S.; Lennon, J.T. Bacteria-Phage Coevolution with a Seed Bank. The ISME Journal 2023, 17, 1315–1325. [CrossRef]

- Thorne, J.L.; Kishino, H. Divergence Time and Evolutionary Rate Estimation with Multilocus Data. Systematic Biology 2002, 51, 689–702. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Forsberg, R.; Rodrigo, A.G. Measurably Evolving Populations. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2003, 18, 481–488. [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, R.; Nebot, M.R.; Chirico, N.; Mansky, L.M.; Belshaw, R. Viral Mutation Rates. J Virol 2010, 84, 9733–9748. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.M.; Duffy, S.; Sanjuán, R. Point Mutation Rate of Bacteriophage ΦX174. Genetics 2009, 183, 747–749. [CrossRef]

- Ridley, M. Evolution; 1. Aufl.; Blackwell Scientific Publ: Boston, 1993; ISBN 978-0-632-03481-9.

- Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Majkowska-Skrobek, G.; Maciejewska, B. Bacteriophages and Phage-Derived Proteins – Application Approaches. Curr Med Chem 2015, 22, 1757–1773. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, E.; Rocha, E.P.C. Phage-Plasmids Promote Recombination and Emergence of Phages and Plasmids. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1545. [CrossRef]

- Flores, C.O.; Meyer, J.R.; Valverde, S.; Farr, L.; Weitz, J.S. Statistical Structure of Host–Phage Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108. [CrossRef]

- Roux, S.; Hawley, A.K.; Torres Beltran, M.; Scofield, M.; Schwientek, P.; Stepanauskas, R.; Woyke, T.; Hallam, S.J.; Sullivan, M.B. Ecology and Evolution of Viruses Infecting Uncultivated SUP05 Bacteria as Revealed by Single-Cell- and Meta-Genomics. eLife 2014, 3, e03125. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Muñoz, S.L. Viral Coinfection Is Shaped by Host Ecology and Virus–Virus Interactions across Diverse Microbial Taxa and Environments. Virus Evolution 2017, 3. [CrossRef]

- De Paepe, M.; Hutinet, G.; Son, O.; Amarir-Bouhram, J.; Schbath, S.; Petit, M.-A. Temperate Phages Acquire DNA from Defective Prophages by Relaxed Homologous Recombination: The Role of Rad52-Like Recombinases. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004181. [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, V.P.; Plugina, L.A.; Nesheva, M.A. Genetic Recombination in Bacteriophage T4: Single-Burst Analysis of Cosegregants and Evidence in Favor of a Splice/Patch Coupling Model. Genetics 1992, 131, 769–781. [CrossRef]

- Martinsohn, J.T.; Radman, M.; Petit, M.-A. The λ Red Proteins Promote Efficient Recombination between Diverged Sequences: Implications for Bacteriophage Genome Mosaicism. PLoS Genet 2008, 4, e1000065. [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, A.K. Bacteriophage-Encoded Functions Engaged in Initiation of Homologous Recombination Events. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2009, 35, 197–220. [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, R.W.; Smith, M.C.; Burns, R.N.; Ford, M.E.; Hatfull, G.F. Evolutionary Relationships among Diverse Bacteriophages and Prophages: All the World’s a Phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 2192–2197. [CrossRef]

- Kupczok, A.; Neve, H.; Huang, K.D.; Hoeppner, M.P.; Heller, K.J.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Dagan, T. Rates of Mutation and Recombination in Siphoviridae Phage Genome Evolution over Three Decades. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 1147–1159. [CrossRef]

- Koskella, B.; Lin, D.M.; Buckling, A.; Thompson, J.N. The Costs of Evolving Resistance in Heterogeneous Parasite Environments. Proc Biol Sci 2012, 279, 1896–1903. [CrossRef]

- van Houte, S.; Buckling, A.; Westra, E.R. Evolutionary Ecology of Prokaryotic Immune Mechanisms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2016, 80, 745–763. [CrossRef]

- Ernits, K.; Saha, C.K.; Brodiazhenko, T.; Chouhan, B.; Shenoy, A.; Buttress, J.A.; Duque-Pedraza, J.J.; Bojar, V.; Nakamoto, J.A.; Kurata, T.; et al. The Structural Basis of Hyperpromiscuity in a Core Combinatorial Network of Type II Toxin-Antitoxin and Related Phage Defense Systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2305393120. [CrossRef]

- Erni, B.; Zanolari, B.; Kocher, H.P. The Mannose Permease of Escherichia Coli Consists of Three Different Proteins. Amino Acid Sequence and Function in Sugar Transport, Sugar Phosphorylation, and Penetration of Phage Lambda DNA. J Biol Chem 1987, 262, 5238–5247.

- Facilitation of Bacteriophage Lambda DNA Injection by Inner Membrane Proteins of the Bacterial Phosphoenolpyruvate:Carbohydrate Phosphotransferase System (PTS)-Web of Science Core Collection Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000168494500005?SID=EUW1ED0DDCRhbL5I5Ea93FD4Ka7f6 (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Morozova, V.; Jdeed, G.; Kozlova, Y.; Babkin, I.; Tikunov, A.; Tikunova, N. A New Enterobacter Cloacae Bacteriophage EC151 Encodes the Deazaguanine DNA Modification Pathway and Represents a New Genus within the Siphoviridae Family. Viruses 2021, 13, 1372. [CrossRef]

- Guegler, C.K.; Teodoro, G.I.C.; Srikant, S.; Chetlapalli, K.; Doering, C.R.; Ghose, D.A.; Laub, M.T. A Phage-Encoded RNA-Binding Protein Inhibits the Antiviral Activity of a Toxin-Antitoxin System. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 1298–1312. [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Chapman, T.; King, K.C.; Mank, J.E.; Paterson, S.; Hurst, G.D.D. Running with the Red Queen: The Role of Biotic Conflicts in Evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2014, 281, 20141382. [CrossRef]

- Lenski, R.E.; Levin, B.R. Constraints on the Coevolution of Bacteria and Virulent Phage: A Model, Some Experiments, and Predictions for Natural Communities. The American Naturalist 1985, 125, 585–602.

- Wright, R.C.T.; Friman, V.-P.; Smith, M.C.M.; Brockhurst, M.A. Cross-Resistance Is Modular in Bacteria–Phage Interactions. PLoS Biol 2018, 16, e2006057. [CrossRef]

- Bergelson, J.; Kreitman, M.; Stahl, E.A.; Tian, D. Evolutionary Dynamics of Plant R -Genes. Science 2001, 292, 2281–2285. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P.; Buckling, A. Bacteria-Phage Antagonistic Coevolution in Soil. Science 2011, 332, 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Marantos, A.; Mitarai, N.; Sneppen, K. From Kill the Winner to Eliminate the Winner in Open Phage-Bacteria Systems. PLoS Comput Biol 2022, 18, e1010400. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, C.B.; Rohwer, F.L. Piggyback-the-Winner in Host-Associated Microbial Communities. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2016, 2, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- De Paepe, M.; Leclerc, M.; Tinsley, C.R.; Petit, M.-A. Bacteriophages: An Underestimated Role in Human and Animal Health? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4. [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Morgan, A.D.; Fenton, A.; Buckling, A. Experimental Coevolution with Bacteria and Phage. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2007, 7, 547–552. [CrossRef]

- Debray, R.; De Luna, N.; Koskella, B. Historical Contingency Drives Compensatory Evolution and Rare Reversal of Phage Resistance. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2022, 39, msac182. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.R.; Agrawal, A.A.; Quick, R.T.; Dobias, D.T.; Schneider, D.; Lenski, R.E. Parallel Changes in Host Resistance to Viral Infection during 45,000 Generations of Relaxed Selection. Evolution 2010, 64, 3024–3034. [CrossRef]

- Weitz, J.S.; Poisot, T.; Meyer, J.R.; Flores, C.O.; Valverde, S.; Sullivan, M.B.; Hochberg, M.E. Phage-Bacteria Infection Networks. Trends Microbiol 2013, 21, 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Maddamsetti, R.; Johnson, D.T.; Spielman, S.J.; Petrie, K.L.; Marks, D.S.; Meyer, J.R. Gain-of-Function Experiments with Bacteriophage Lambda Uncover Residues under Diversifying Selection in Nature. Evolution 2018, 72, 2234–2243. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.R.; Dobias, D.T.; Medina, S.J.; Servilio, L.; Gupta, A.; Lenski, R.E. Ecological Speciation of Bacteriophage Lambda in Allopatry and Sympatry. Science 2016, 354, 1301–1304. [CrossRef]

- Doud, M.B.; Gupta, A.; Li, V.; Medina, S.J.; De La Fuente, C.A.; Meyer, J.R. Competition-Driven Eco-Evolutionary Feedback Reshapes Bacteriophage Lambda’s Fitness Landscape and Enables Speciation. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 863. [CrossRef]

- Birkholz, N.; Jackson, S.A.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Fineran, P.C. A Mobile Restriction–Modification System Provides Phage Defence and Resolves an Epigenetic Conflict with an Antagonistic Endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, 3348–3361, doi:Rapid diversification of coevolving marine Synechococcus and a virus.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).